Abstract

Purpose

People who survive a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) often face enduring health challenges including physical disability, fatigue, cognitive impairments, psychological difficulties, and reduced quality of life. While group interventions have shown positive results in addressing similar issues in chronic conditions, the evidence involving SAH specifically is still sparse. This service evaluation aimed to explore SAH survivors’ experiences of attending a multidisciplinary group-based support programme tailored to address unmet needs identified in previous literature, with the ultimate aim to refine future iterations of the programme and improve quality of care post-SAH.

Materials and Methods

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 12 individuals who attended the programme. The resulting data were analysed thematically.

Results

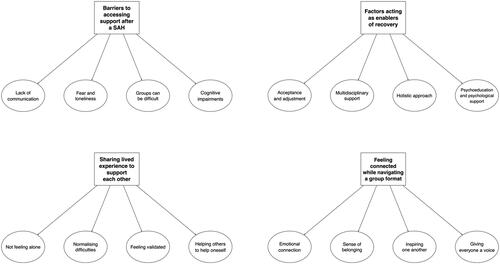

Four overarching themes emerged from the analysis: (1) Barriers to accessing support after a SAH, (2) Factors acting as enablers of recovery, (3) Sharing lived experience to support one another, (4) Feeling connected while navigating a group format.

Conclusions

Lack of communication, fear, loneliness, and cognitive impairments can act as barriers to engagement with support, while acceptance and adjustment, holistic multidisciplinary input, and psychological support may represent successful enablers of recovery. Implications for future iterations of the programme as well as clinical rehabilitation and service development are discussed.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

A multidisciplinary group-based support programme may help rehabilitation following a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH).

Factors such as lack of communication, fear, loneliness, and cognitive impairments may act as barriers to engagement, while acceptance and adjustment, holistic multidisciplinary team input, and psychological support may enable recovery.

Services may wish to monitor the effectiveness and frequency of their communication while making sure a clear pathway of support and established referral routes are in place when SAH patients are discharged from hospital.

Providing participants with written materials to use during each session as well as allowing for more time to connect with one another other may help with cognitive difficulties during group sessions.

Introduction

A subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is a sudden onset neurological condition that accounts for 5% of all strokes and affects between 2 and 22 people per 100,000 each year [Citation1]. It is caused by a bleeding into the fluid filled space around the brain which, in the absence of trauma, is usually caused by the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm (“aneurysmal SAH” [Citation2]). SAH occurs in a younger age group than ischaemic stroke, with half of patients being younger than 55 at ictus, and tends to affect women more frequently than men [Citation3]. Despite advances in its treatment, SAH continues to carry a high mortality risk, with approximately 35% of cases proving to be fatal [Citation4].

For up to 70% of the individuals who survive the acute phase, SAH is associated with several physical sequelae (e.g., hemiplegia [Citation5] and fatigue [Citation6]) as well as psychological difficulties such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptomatology [Citation7]. Cognitive impairments are also frequent following a SAH, and often affect speed of information processing, attention, memory, language, and executive functioning [Citation8]. Unsurprisingly, the combination of these issues can have profound consequences on the quality of life of affected individuals, especially due to numerous changes in their ability to work, form and maintain relationships, live independently, and integrate socially [Citation9]. Similarly, such difficulties have also been recognised to have a major impact on those caring for someone affected by a SAH [Citation10].

In light of the above, the development of interventions aiming to optimise recovery and rehabilitation has been strongly warranted. In this regard, evidence has shown that individuals affected by SAH indicate coping with fatigue, cognitive impairments, and emotional well-being as their three main needs for rehabilitation [Citation11]. Further studies also highlighted anxiety and depression [Citation12], apathy [Citation13], and feelings of abandonment following hospital discharge [Citation6] as major factors affecting recovery after a SAH.

A type of approach with a long history of implementation for rehabilitation purposes is represented by group-based interventions [Citation14]. Over the past few decades, these have proven to be effective not only with people with chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes [Citation15]), but also neurological diseases such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis [Citation15–17]. With specific reference to SAH, while group interventions are adopted within clinical services as a way to manage distress [Citation18], the current literature around their successful implementation appears sparse, with no evidence available to date on the subjective experiences of the individuals who attend them. This represents a considerable gap, since the use of qualitative methods to explore patients’ experiences of attending intervention programmes has been recognised as playing a pivotal role in healthcare research [Citation19].

In this article, we present the perspectives of patients who attended a multidisciplinary group-based support programme following SAH in a National Health Service (NHS) Trust in the North-West England. More specifically, the participants’ experience of attending the group-based programme was investigated with the aim to inform and refine future iterations of the programme itself, and ultimately improve the quality of care for people with SAH in accordance with recent guidelines [Citation20].

Materials and methods

Theoretical framework

This project adopted qualitative methods based on individual semi-structured interviews [Citation21].

Participant selection

Convenience sampling methods were used, whereby patients under the care of the host NHS Trust who had suffered a SAH were offered to attend the programme as part of their standard post-discharge clinical care or during a routine call at 6- and 12-months follow-up. At the end of the programme, attendees were invited to take part in semi-structured interviews.

Of the 13 patients who were invited to attend following two consecutive iterations of the programme, 12 agreed to participate in the study (five from the first iteration, seven from the second). All participants were female, with an average age of 58.4 years (range: 47–80). The mean time since SAH diagnosis was 16 months (range: 7–30). In order to avoid issues related to accessibility and facilitate attendance, all interviews were all carried out remotely (i.e., via phone and Microsoft Teams). illustrates the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Participants demographic data.

Due to complications in the acute phase, one participant developed difficulties with language production, and was supported by their partner throughout the programme and the semi-structured interview.

Multidisciplinary group-based support programme

The multidisciplinary group-based support programme consisted of seven 1-h sessions at a brain charity venue closely affiliated with the NHS Trust. Sessions one to six took place fortnightly, while session seven followed a 4-week break. The aim of the 4-week break was to facilitate the assimilation and practice of the coping strategies discussed in the programme. The sessions were led by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) consisting of a SAH Specialist Nurse, a Consultant Clinical Neuropsychologist, an Assistant Psychologist, and a Cognitive and Personal Wellbeing Practitioner with lived experience of SAH. Each session focused on one of the unmet needs most commonly reported by SAH survivors in a previous study [Citation11] and was structured to encourage open discussions around medical, psychological, and social aspects of the participants’ experience. The programme’s content, schedule, and delivery remained unchanged across both iterations. summarises the topic of each session of the multidisciplinary programme.

Table 2. Support group session topics.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out at the end of each programme iteration by a female graduate level Assistant Psychologist (AS) under the supervision of two male doctoral level Clinical Psychologists (NZ, RS) and a female Registered Nurse (LD). All interviews were conducted in person by AS between November 2022 and June 2023 and had a mean duration of 35 min (range: 21–47). None of the programme leads or research supervisors were present during these. In addition, although the assistant AS had a support role in the delivery of the programme, no previous significant relationship was in place between the interviewer and the participants—thus allowing for the latter to feel comfortable to express their opinions freely.

An interview schedule (available as Supplemental Document) was developed based on relevant literature [Citation11] as well as clinical experience within team and was agreed collectively following iterative consultations. This process, along with the experience gained with previous similar qualitative research from the authors [Citation22], helped minimise concerns regarding validity and reliability of the interviews even though no pre-testing could be carried out. The interview schedule was structured into six sections, covering the following topics: (a) Participant Introduction, (b) Group Format, (c) Programme Accessibility, (d) Programme Content, (e) Group Engagement, (e) Programme Outcomes. The structure remained the same across both programme iterations. Theoretical saturation was deemed to be achieved at the end of the second iteration as little to no additional information appeared to have emerged [Citation23].

Data analysis

Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The anonymised transcripts were then imported and organised into the NVivo® qualitative data analysis software. Here, data were analysed by AS under the supervision of NZ using thematic analysis according to the principles illustrated by Braun and Clarke [Citation24].

More specifically, the analysis started with a data familiarisation process, during which transcriptions were read numerous times over a number of weeks to initiate ideas for themes. Following on from this, codes were identified and linked to themes which had emerged over the dataset. The initial themes and codes were then reviewed in order to ensure consistency across the dataset. A thematic map was then drawn with titles of each theme and this was checked against the dataset.

Throughout the whole analysis process, a critical realist epistemological stance was assumed, whereby the perspectives of the participants were conceptualised as being as real and meaningful as physical and behavioural phenomena [Citation25]. In addition, open discussions were held between all members of the team to ensure credibility, transparency, and reliability [Citation26].

Ethical considerations

The present project was registered as a service evaluation with the Research & Innovation Department of the host NHS Trust (REF: 23HIP30). All patients provided full written consent and all audio recordings and transcripts were anonymised.

Results

After familiarisation with the dataset, 32 codes were generated, which were then arranged into seven preliminary themes. Following iterative revisions, the final code list was reduced to a total of 16, divided into four overarching themes which were unique and in accordance with the topic of the analysis. Each theme is outlined in detail below, along with relevant quotes from the participants. Code names are highlighted in italics when mentioned specifically. illustrates the final thematic map.

“I was walking alone for a year”: barriers to accessing support after a SAH

The first theme to emerge from the data revolved around the several barriers participants had to face in terms of accessing support following their diagnosis, which they felt had been scarce until they attended the group-based programme. For instance, lack of communication from healthcare services could often led to feelings of fear and loneliness:

I was walking alone for a year on my own with nothing. […] For a year and a half, I knew nothing until the group. And then then, and then in the group they’re all saying “yeah, and you will go through that”, and “this will happen” and “you will feel tired” and “you will need to sleep.” I wasn’t told any of these things. (Participant 2)

People like me who spent their life being very independent and just getting on with things, asking for help doesn’t come naturally. And I think it was more of awareness that even if you haven’t got your hand up, that you still need that being reached out to. (Participant 12)

I think the only thing you think of when you go to… to groups […] you worry that either… I won’t have the confidence to say things. Which didn’t happen, but also that sometimes when you go to groups is, there are people that always talk more and so you then don’t feel like you want to say something or, you know, it’s all been said type thing. (Participant 1)

Some people wouldn’t go on the courses. Some people would be frightened to go on the courses. (Participant 5)

When you come out of hospital, you’re still really ill. And even though you’ve had conversations with people, either you can’t recall them unless somebody tells you about them all or you know, they’re just not registered with you. (Participant 7)

You can’t understand, there’s a little bit of cognitive problem still, and so if there’s more than three people talking at once, that’s it. Forget it. (Participant 4)

I think probably it would have been good if, when you were, when you guys did your talky bit, if you’d have sort of said all this, “I’m gonna give you notes at the end of this”, because I was, I think, for a couple of them, I was busy scribbling away thinking that I know I won’t remember everything that’s coming up on all the slides. And I wanted to remember them. (Participant 7).

And also, what I found was really good for me and probably for a lot of others, cause taking in all the information is a lot at a time, it’s tiring and, and not always, you can’t remember it all but then we were given handouts to take home and keep so I could, because I struggle with reading text and any print for a long, I could just pick it up and put it down whenever I needed to, and it’s there to, to refer to now, so I thought that was good. (Participant 12)

“You know, it’s okay to be this way”: factors acting as enablers of recovery

The second theme to emerge from the data concerned the patients’ journey towards recovery and the factors that may enable it during the group-based programme. With regards to this, participants often described how they initially used to experience feelings of guilt and self-blame for some of the difficulties they had developed, such as disinhibition and fatigue. However, many also saw the attendance to the programme as an opportunity to increase their levels of acceptance and adjustment to living with a chronic condition, particularly by being able to interact with people who had also suffered a SAH:

I’ve suddenly become this woman with no filter, and I’ll just say whatever I want. And that’s wrong. Um, and it was recognising that it’s part and parcel of my experience and so I shouldn’t chastise myself about it. (Participant 2)

It’s made me realise that it’s okay to feel the things that I feel. […] it was just kind of realising that it’s just something that happened, and it erm, you know, you just have to accept that. (Participant 12)

The confidence, and general acceptance of myself, and the new me, if you want to phrase it that way, but that’s what I’ve taken away [from the programme]. (Participant 9)

I think a lot of it for me as well is like erm, to stop beating yourself up when I can’t do things. Just, just listening to other people. And taking on board, how, how it’s affected their lives just made me realise, you know, it’s just, this is the way it is. And it’s okay. It’s okay. You know, it’s okay to be this way. And I am making progress. And I know, I will continue to make progress, you know, and that group has given me that positivity. (Participant 12)

It feels great that you feel like you’re covered from all angles. You know, you guys there, the psychologist, the surgeons there, the nurse is there, you feel like well, there’s nothing else I need because these guys have got it all covered. (Participant 7)

It was really, really useful. It was. All aspects were covered, weren’t they? There were people who’d been through it, the people who’ve had to deal with it from medical point of view, from a psychological point of view, it was everything that was there. It was a complete package, wasn’t it? (Participant 1)

Well, to me it, it’s kind of a partnership that works, you know, it’s holistic. You know, it was all kind of medical, or it was all psycholo… psychology, you know, it was fine, it was each of those have got their own, um, expertise and value for, for what they give. But I think cause it was done in partnership. (Participant 8)

When you go through something like this, it’s not only just your physical, um, things you’ve gone through, it’s your mental, it’s your cognitive. It, it’s all your emotions. So, with everybody being involved from, from psychology, from medical, nursing, um, it actually covers everything from us for us as well, […] it felt as though it was inclusive of professionals and very holistic in that way. (Participant 1)

I mean, obviously from the medical side is what you’ve gone through. So, to be able to understand that, that really helps. But then the psychological, it’s about emotions, feelings, perceptions, and to try to marry those two up because it’s… It’s severe trauma to the brain, um, which runs your entire body. So obviously it’s gonna be twofold. (Participant 2)

You see by the time you come to that meeting, you, you physically repaired, you know there’s not gonna be another blade. […] So physically that’s it. So the next bit is that the psychology, and to meet the nurse who was a very, very important part of the journey. Very very important indeed. […] You know, we didn’t realize it was really thought of as a PTSD thing now. (Participant 4)

You know, I think the thing is that people, when they see me visually, there’s nothing wrong, so they just assume, oh, she’s fine now, she’s back to normal. So they’ll just carry on as normal. Without appreciating the huge impact it’s had on my brain. And on my daily functions and how I operate. (Participant 2)

I wanted to know what happened to me. […] I asked [Registered Nurse], for instance, ‘did I go in a coma?’ because I can’t remember everything, just, but I do remember bits and it’s interesting for her to explain to me why that is, how your body reacts. […] They explain it, you know […] And that’s what, I found, was reassuring, helpful, erm and know what has actually happened to you after. (Participant 11)

[The programme] was giving me the information that I needed. Um, because I knew it had happened to me. But I didn’t, after the fact, you don’t really want to read up, read up about it. And it saved me having to do that, and I felt in a safe environment to learn what had happened, if that makes any sense. […] I was happy about that. (Participant 9)

“I wanted to help myself and help others”: sharing lived experience to support one another

Many participants highlighted the value of sharing lived experience during the group-based programme, which emerged as the third overarching theme in the analysis. More specifically, the opportunity to share and discuss these in detail with people who had been through similar hardship was considered essential as a way of not feeling alone:

It was good to take away from the group that I’m not on my own experiencing these difficulties after. (Participant 11)

It’s a really lonely experience, a brain haemorrhage, and to actually be in the room of people have gone through the same and doing other things, it was, it just made it all more real and easier. (Participant 1)

It was enabling me to kind of have that outlet to say, you know, those feelings were quite natural […] I was able to do that and that, that was, I’d say, a major one for me, that I was able to really kind of talk about that. (Participant 8)

Everybody’s experiences are so different, but it normalised a lot of things that happened to you because when you’re talking one to one with a professional who hasn’t necessarily been through it, it, not demeaning their expertise, but people who actually had it as well, who had done it, they find. You think, my God, that was the same! (Participant 1)

It made you feel better about the symptoms, like, feeling the fatigue. I think I always felt like I shouldn’t be doing this. I shouldn’t be feeling like this, I’m only 47. I shouldn’t be so exhausted after, after doing this. It made me feel better that I knew that other people felt like that. (Participant 9)

Because it was helpful to know from others that they felt the same. Um, I think one of the women. […] She said that when she went in a larger group or with a family gathering together, she would just get really, really overwhelmed. So, she would have to withdraw herself from that environment. Otherwise, she was prone to possibly saying something that somebody might find offensive. And I just thought, God, that’s exactly how I’ve been feeling. (Participant 2)

I think what helps me was to be able to just, let it all out and talk about that day. Um, and because I kind of… with my friends and family I did at the beginning […] your friends and family who understand to a certain degree, but you’ve never got that is in common. We’ve all got something in common. (Participant 8)

I also was kind of looking forward really in some sense to meet other people who’d actually gone through this, sharing their experiences and seeing some common threads from, from my experiences, which, you know, which will help me. And also, some of my experience, which will help them… I wanted to go and I wanted to help myself and help others. (Participant 8)

“There was a sense of comradery about it”: feeling connected while navigating a group format

The last overarching theme which emerged as shaping the participants’ experiences of participating in the group-based programme was represented by the unexpected positive consequences of navigating a group format for the first time. For instance, some participants reported experiencing novel feelings of emotional connection with the other attendees:

Seeing somebody face to face and actually the emotions that they, uh, portray… well, it goes deep. […] listening to people in person, um, is, uh, there’s nothing that sort of can beat that I don’t think… we immediately all felt well, I felt, you know, emotionally very connected and that’s very rare in life, isn’t it? (Participant 10)

For me, it…, it’s that connection that nobody else will really ever understand. […] We’ve all got something in common and we’ve all got a connection and we all feel, I feel as though with that we’ve got that framework of support. (Participant 8)

I’m not a very open person. I’m quite closed, I keep things to myself. So, I think I set off thinking, I don’t know whether, how much I’ll join in with this. But then just after the, after the first session, when, you know, everybody talks about, you know, their experience of having the haemorrhage, you just, you just suddenly felt like, oh, my gosh, I belong to this group of people. You know, we’ve got something, we’ve got a common thread. (Participant 7)

I think in a group format people can see other people’s reactions and they don’t feel as bad saying what they’ve got to say. So, like the very first meeting we were passing the box of tissues around, um, and I think it gave people the confidence to open up about their own experience. So, it’s much better in a group. I would have struggled more on a one to one to articulate what I wanted to say. (Participant 9)

You know, I’m not used to sort of speaking in groups, but, um, so making sure that everybody, that you, you heard how everybody felt about it is, is important. […] Some people can actually talk for England. And go on about it. And indeed, um, I’m a bit conscious of talking and then sort of rambling on. […] But it’s important that everybody else has their say. (Participant 10)

There was a sense of comradery about it, I think. […] The thing I struggle with is self-pity. Why me? Why me? And being in that group and seeing how other people who’ve had a much tougher time of it and how they’re coping with it, it made me think, now, come on, just put yourself together. You, you, it could have been so much worse. You’re still here for heaven’s sake. And I think, I think that was the bottom. And I felt all the people in the room, the back, the bottom of it all was, we are still here, we are survivors, and it was sharing that experience. (Participant 1)

Discussion

This article explored 12 SAH survivors’ experiences of attending a group-based support programme tailored to address unmet needs in this population. Individual semi-structured interviews were carried out and analysed thematically, and four overarching themes emerged from the data: (1) Barriers to accessing support after a SAH, (2) Factors acting as enablers of recovery, (3) Sharing lived experiences to support one another, and (4) Feeling connected while navigating a group format. To our knowledge, this is the first project to date exploring this topic.

The first theme revolved around the several barriers participants perceived as impeding their access to support following a SAH, which included issues such as lack of communication, feelings of fear and loneliness, difficulties interacting with a group, and cognitive impairments. These findings appear consistent with previous evidence involving other chronic conditions. For example, a study exploring attendance to support groups for people with schizophrenia or depression also reported concerns about social interactions to be a barrier for accessing support groups [Citation27], while lack of communication was highlighted in a qualitative exploration of patients’ perceived barriers towards accessing cardiac rehabilitation [Citation28]. Regarding SAH specifically, our finding of lack of communication was also consistent with evidence showing it is not uncommon for SAH patients to fall between the gaps of clinical provision due to communication issues between both intra- and inter-hospital services [Citation29]. As recent clinical guidance in the United Kingdom underlined how SAH patients may feel unclear about their medical follow-ups [Citation30], the feelings of fear and loneliness reported by our participants may also be partially understood within this context.

The second theme concerned the factors that participants saw as enablers of their recovery journey. These included developing acceptance and promoting adjustment to their condition, receiving support from an MDT, adopting a holistic approach towards recovery, and receiving psychoeducation and psychological input. All of these are consistent with previous literature involving SAH patients, which highlighted the importance of MDT follow-ups post-diagnosis [Citation6] as well as a need for psychoeducation and psychological input due to mental health difficulties such as distress, depression, and anxiety [Citation31,Citation32]. In addition, whilst there is a lack of previous investigations on the experience of SAH patients attending group interventions, findings from a study involving people who attended an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) group for stroke highlighted the effectiveness of health professionals working together and the importance of psychoeducation to facilitate adjustment to the condition [Citation33]. In fact, the adoption of a therapeutic approach focused on acceptance such as ACT has also shown to yield positive outcomes in a wide range of neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, traumatic brain injury, Huntington’s disease, and motor neuron disease [Citation15,Citation16,Citation34–36].

The opportunity to share lived experience and find ways to support each other was also valued considerably by the participants. These formed the core of theme three, in which patients outlined a number of related positive factors such as not feeling alone, normalising difficulties, feeling validated, and being able to help others while being helped themselves. All of these appeared to be in line with previous evidence highlighting the importance of normalisation and validation not only for chronic illness and psychological difficulties in general [Citation37], but also with regards to the implementation of group-based programmes for people with stroke and other neurological conditions [Citation38,Citation39]. In addition, developing a reciprocal attitude towards providing help to other people to help oneself has been long recognised as therapeutic in psychology, particularly within groups [Citation40]. More specifically, after being first described as “helper theory” in the 1960s [Citation41], what came to be known as the “helper therapy principle” has seen a rich history of applications with people with chronic conditions in general (e.g., chronic pain, alcoholism; [Citation42]) as well as neurological ones specifically (e.g., multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury; [Citation43]).

Finally, the fourth and last theme to emerge from the analysis related to the unexpected feelings of connectedness the participants developed as a consequence of navigating a group-based programme. More specifically, these involved the development of emotional connections and a sense of belonging, finding inspiration in one another to explore new coping strategies, and making sure that everyone was given the opportunity to express their voice in the group. Part of these findings appear to be consistent with previous investigations in the literature. In particular, the achievement of unexpected levels of connectedness and belonging in group-based interventions have been reported previously in a range of neurological populations, including people with stroke [Citation44], brain tumours [Citation45], and Parkinson’s [Citation46].

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the present project is represented by its exploration of a topic—the subjective experience of people attending a multidisciplinary group-based support programme after a SAH—which has been long neglected in the literature. In particular, gathering this information through the adoption of qualitative method not only allowed participants to have a voice and share their thoughts, but also to investigate subjective factors which are relevant for recovery and may go overlooked when adopting purely quantitative methods.

However, several limitations should be taken into account along with the current results. First, the exploratory nature of this project, based on a service evaluation recruiting participants from a specific clinical setting in the north-west of England, means that there was no attempt to generalise findings. As a consequence, the present findings may not represent the experience of people with SAH elsewhere. Similarly, the all-female sample, while consistent with the higher incidence of SAHs found in women [Citation3], may be considered a limitation. In addition, the Assistant Psychologist who carried out the interviews with the participants also supported the delivery of one of the programme’s sessions and attended all the remaining ones. While this may be considered a methodological limitation, no significant relationship was established between the interviewer and the participants. Moreover, the validity and reliability of the methods were also further ensured by having the analysis process supervised by a qualified Clinical Psychologist who was not involved with either the programme’s delivery or the interviews.

Clinical implications and future directions

A number of implications which are relevant to clinical work with SAH patients may be drawn from our findings. First, the results highlighted that patients may have to struggle with lack of communication from services when they are discharged from hospital, which in turn may trigger feelings of fear and loneliness. Thus, services may wish to monitor the effectiveness and frequency of their communication while making sure a clear pathway of support and established referral routes are in place following a patient’s discharge whenever ongoing support is required. In this regard, recent SAH management guidelines have highlighted the need for an MDT approach to identify SAH patient needs upon discharge and subsequent interventions for mood disorders [Citation20].

Secondly, further dedicated care pathways should be developed for people with SAH specifically. While SAH is considered a form of stroke, the age of SAH survivors is typically younger compared to ischemic stroke survivors and the associated sequalae differ considerably, with greater reported psychological distress in lieu of reduced physical disability. Evidence has also shown that interventions following a traumatic experience are best facilitated by relatability through interactions with people characterised by similar experiences and demographics, including gender [Citation47]. Considering the higher prevalence of SAH among women, this may represent a further difference between SAH and ischemic stroke survivors [Citation48]. As third sector stroke charities predominantly focus on ischemic stroke, very limited support is therefore often available to those with SAH. This is particularly concerning when considering that, over a three-month period, admissions rates for SAH are typically around 1500 across a number of hospitals the in United Kingdom and Crown Dependencies [Citation49], with 80% of SAH patients reporting at least one unmet need [Citation11].

In addition, clinicians who may wish to implement group-based programmes similar to ours should consider how cognitive impairments may affect the patients’ ability to interact with multiple people and attend the group sessions, particularly as these may render some unable to retain the information they receive. However, providing participants with written materials to use during each session may prove helpful in this regard. Moreover, since our findings highlighted emotional connection and sense of belonging as paramount to navigate a group format, a potential way to tackle the impact of cognitive issues may lie in giving patients more time to connect with one another other. In turn, this may also allow patients to engage with the progressive normalisation and validation of their difficult experiences, find meaning in helping others, and ultimately achieve a renewed sense of acceptance of their condition and appreciation for their recovery journey.

In terms of future directions, further studies—based on more representative samples both in terms patients’ characteristics and clinical settings—are warranted to increase our understanding of SAH patients’ experiences of participating in group interventions. With regards to our multidisciplinary group-based support programme specifically, whilst preliminary positive evidence on acceptability and feasibility may be inferred from the present service evaluation, further investigations are required. In particular, quantitative methods should also be adopted to complement the current findings by evaluating the programme’s feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness within a mixed-method framework.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first project to date to evaluate the subjective experiences of people with SAH who attended a multidisciplinary support group intervention. The results highlighted that factors such as lack of communication, fear, loneliness, and cognitive impairments acted as barriers to engagement with support, while acceptance and adjustment, holistic MDT input, and psychological support represented successful enablers of recovery. The latter also appeared to be improved by the group-based format of the programme, which provided patients with the opportunity to share lived experiences, normalise difficulties, feel validated, find meaning in helping others, and develop a sense of emotional connection and belonging. Additional evidence—based on further iterations of the programme evaluated within a mixed-method framework—is required to corroborate these preliminary positive findings.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (414.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to all the participants and supporters who took part in this service evaluation, as well as the Brain and Spinal Injury Centre who allowed us to use a room to facilitate sessions.

One of the authors’ grandmother, Nanny P, suffered a subarachnoid haemorrhage in 2000, at a time when there was little to no dedicated support available for SAH. With this article, it is also our wish to thank those who dedicate their time in healthcare to supporting and improving the wellbeing of this population.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abraham MK, Chang WTW. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34(4):901–916. November 1 doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.06.011.

- Khey KMW, Huard A, Mahmoud SH. Inflammatory pathways following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020;40(5):675–693. July 1 doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00767-4.

- van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):306–318. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673607601536 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6.

- Petridis AK, Kamp MA, Cornelius JF, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage-diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(13):226–236.

- Danière F, Gascou G, Menjot De Champfleur N, et al. Complications and follow up of subarachnoid hemorrhages. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96(7-8):677–686. doi:10.1016/j.diii.2015.05.006.

- Persson HC, Törnbom K, Sunnerhagen KS, et al. Consequences and coping strategies six years after a subarachnoid hemorrhage – a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181006. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181006.

- Hütter BO, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as a psychological trauma: clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(4):923–930. doi:10.3171/2013.11.JNS121552.

- Walter J, Grutza M, Vogt L, et al. The neuropsychological assessment battery (NAB) is a valuable tool for evaluating neuropsychological outcome after aneurysmatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):429. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-02003-9.

- Kulkarni A, Devi B, Konar S, et al. Predictors of quality of life at 3 months after treatment for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol India. 2021;69(2):336–341. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.314581.

- Leung KY(, Cartoon J, Hammond NE. Depression screening in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage and their caregivers: a systematic review. Aust Crit Care. 2023;36(6):1138–1149. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2022.12.007.

- Dulhanty LH, Hulme S, Vail A, et al. The self-reported needs of patients following subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(24):3450–3456. doi:10.1080/09638288.2019.1595748.

- Ackermark YIP, Schepers VPM, Post MWM, et al. Longitudinal course of depressive symptoms and anxiety after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(1):98–104. doi:10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04202-7.

- Tang WK, Wang L, Tsoi KKF, et al. Apathy after subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2022;155:110742. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110742.

- Schopler JH, Galinsky MJ. Support groups as open systems: a model for practice and research. Health Soc Work. 1993;18(3):195–207. https://academic.oup.com/hsw/article/632840/Support doi:10.1093/hsw/18.3.195.

- Zarotti N, Eccles F, Broyd A, et al. Third wave cognitive behavioural therapies for people with multiple sclerosis: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;45(10):1720–1735. doi:10.1080/09638288.2022.2069292.

- Zarotti N, Eccles FJR, Foley JA, et al. Psychological interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease in the early 2020s: Where do we stand? Psychol Psychother. 2021;94(3):760–797. https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/papt.12321 doi:10.1111/papt.12321.

- Ch’ng AM, French D, McLean N. Coping with the challenges of recovery from stroke: long term perspectives of stroke support group members. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(8):1136–1146. November doi:10.1177/1359105308095967.

- Noble AJ, Schenk T. Psychological distress after subarachnoid hemorrhage: patient support groups can help us better detect it. J Neurol Sci. 2014;343(1-2):125–131. August 15 doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.05.053.

- Renjith V, Yesodharan R, Noronha J, et al. Qualitative methods in health care research. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12(1):20. doi:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_321_19.

- Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2023;54(7):E314–E370. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000436.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: SAGE; 2009.

- Eccles FJR, Craufurd D, Smith A, et al. Experiences of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for premanifest Huntington’s Disease. J Huntingtons Dis. 2021;10(2):277–291. https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi= doi:10.3233/JHD-210471.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Family Health Int. 2006;18:59–82.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Sayer A. Realism and Social Science. London: Routledge; 2000. https://profs.basu.ac.ir/spakseresht/free_space/realism and social science (introduction).pdf

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):160940691773384. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1609406917733847 doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Dilgul M, McNamee P, Orfanos S, et al. Why do psychiatric patients attend or not attend treatment groups in the community: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208448. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208448.

- Tod AM, Lacey EA, McNeill F. “I’m still waiting…”: barriers to accessing cardiac rehabilitation services. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(4):421–431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02390.x.

- Finn EB, Campbell Britton MJ, Rosenberg AP, et al. A qualitative study of risks related to interhospital transfer of patients with nontraumatic intracranial Hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(6):1759–1766. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.12.048.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management; 2022. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228.

- Al-Khindi T, MacDonald RL, Schweizer TA. Cognitive and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41(8):e519–e536. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581975.

- von Vogelsang AC, Nymark C, Pettersson S, et al. “My head feels like it has gone through a mixer” – a qualitative interview study on recovery 1 year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(8):1323–1331. doi:10.1080/09638288.2022.2057601.

- Majumdar S, Morris R. Brief group-based acceptance and commitment therapy for stroke survivors. Br J Clin Psychol. 2019;58(1):70–90. doi:10.1111/bjc.12198.

- Simpson J, Eccles FJ, Zarotti N. Extended evidence-based guidance on psychological interventions for psychological difficulties in individuals with Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease, and multiple sclerosis; 2021. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4593883.

- Zarotti N, Dale M, Eccles F, et al. Psychological Interventions for People with Huntington’s Disease: A Call to Arms. J Huntingtons Dis. 2020;9(3):231–243. https://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi= doi:10.3233/JHD-200418.

- Zarotti N, Mayberry E, Ovaska-Stafford N, et al. Psychological interventions for people with motor neuron disease: a scoping review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2021;22(1-2):1–11. doi:10.1080/21678421.2020.1788094.

- Leahy RL. A social-cognitive model of validation. Compassion: conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy. New York: Routledge; 2005.121–147. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203003459-8/social-cognitive-model-validation-robert-leahy

- Smith FE, Jones C, Gracey F, et al. Emotional adjustment post-stroke: a qualitative study of an online stroke community. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2021;31(3):414–431. doi:10.1080/09602011.2019.1702561.

- Meade O, Buchanan H, Coulson N. The use of an online support group for neuromuscular disorders: a thematic analysis of message postings. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(19):2300–2310. September 11 doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1334239.

- Munn-Giddings C, Borkman T. Reciprocity in peer-led mutual aid groups in the community: implications for social policy and social work practices. In Reciprocal Relationships and well-being. New York: Routledge; 2017. pp. 57–76.

- Riessman F. The “Helper” therapy principle. Soc Work. 1965;10:27–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23708219

- Arnstein P, Vidal M, Wells-Federman C, et al. From chronic pain patient to peer: benefits and risks of volunteering. Pain Manag Nurs. 2002;3(3):94–103. doi:10.1053/jpmn.2002.126069.

- Schwartz CE, Sendor RM. Helping others helps oneself: response shift effects in peer support. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1563–1575. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953699000490 doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00049-0.

- Wijekoon S, Wilson W, Gowan N, et al. Experiences of occupational performance in survivors of stroke attending peer support groups. Can J Occup Ther. 2020;87(3):173–181. doi:10.1177/0008417420905707.

- Mallya S, Daniels M, Kanter C, et al. A qualitative analysis of the benefits and barriers of support groups for patients with brain tumours and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(6):2659–2667. doi:10.1007/s00520-019-05069-5.

- Olsson M, Nilsson C. Meanings of feeling well among women with Parkinson’s disease. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2015;10.

- Orille AC, Marton V, Taku K. Posttraumatic growth impacts views of others’ trauma: the roles of shared experience and gender. J Humanist Psychol. 2022;62(5):669–682. doi:10.1177/0022167820961928.

- Peters SAE, Carcel C, Millett ERC, et al. Sex differences in the association between major risk factors and the risk of stroke in the UK Biobank cohort study. Neurology. 2020;95(20):E2715–E2726. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000010982.

- Gough MJ, Goodwin APL, Shotton H. Managing the flow?: A review of the care received by patients who were diagnosed with an aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. 2013. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=opAT0AEACAAJ.