?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to answer the question: Does an innovative audit teaching concept and its application provide the required level of quality and adequacy for its purpose as a teaching resource for use in a higher education setting? To answer this question, data from a teaching resource (the ‘International-Learning-Platform-for-Accountancy’ as part of the Erasmus+ project ILPA) were analysed. A case study research design is applied to provide empirical evidence on the teaching resource’s quality and its application during three specific learning events. We find that: the teaching material fulfils the criteria developed by the main reference education literature, and from the students’ perspective the audit teaching resource as applied within a learning event, met their academic needs. This means that the design of this audit teaching resource is in line with existing literature, its instructional recommendations are manageable, and its application fulfils the needs of students.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to illustrate and analyse the content and application of the audit teaching concept developed in the project, ‘International Learning Platform for Accountancy (ILPA)’.Footnote1 An audit teaching concept is understood as a collection of audit teaching materials and suggestions for the (intended) use of the material during any kind of learning event. Hence, the term ‘teaching concept’ is similar to Bundsgaard and Hansen’s (Citation2011) definition of a ‘design for learning’. Therefore, we use the term learning concept throughout the paper to refer to the ILPA audit teaching concept.

In particular, this paper aims to answer the research question: Does an innovative audit teaching concept and its application provide the required level of quality and adequacy for its purpose as a teaching resource for use in a higher education setting? Hence, this study’s objective is to identify the value of the analysed teaching resource and to provide suggestions as to its improvement. The interest in this topic and the learning concept has been raised as a result of the authors’ involvement with the ILPA project, which has been incorporated by ten international HEIs with a shared focus on creating a learning platform for accounting.

In the context of the ongoing debate surrounding learning approaches in accounting (AAA, Citation1986; Adler & Milne, Citation1997; AECC, Citation1990; Crawford et al., Citation2011; Faello, Citation2016; IFAC, Citation1996; Jaijairam, Citation2012; Milne & McConnell, Citation2001; Ocampo-Gómez & Ortega-Guerrero, Citation2012; Pincus et al., Citation2017; Wynn-Williams et al., Citation2008) and their application and quality (Alderman et al., Citation2014; Bundsgaard & Hansen, Citation2011; De Lange et al., Citation2003; Jackling & De Lange, Citation2009), it is important to conduct regular, literature-based evaluations of teaching concepts. Hence, the significance of this paper lies in its literature-based evaluation of the ILPA audit teaching concept (hereinafter: audit teaching concept). In line with Sangster et al. (Citation2015), the findings of this study should have an impact on the academic, as well as the classroom, dialogue and the faculty involvement (Pincus et al., Citation2017).

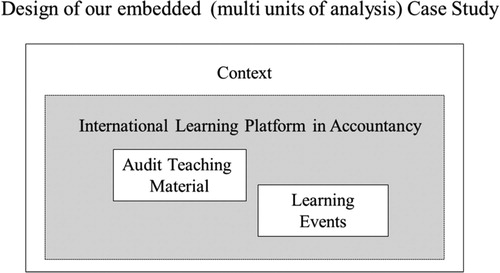

For the analysis, a single case study research design with embedded units is employed. Specifically, an in-depth analysis of two embedded units is performed: (1) the audit teaching material and (2) its application within learning events. The methods of data collection are twofold: firstly, a content analysis of the teaching material is conducted; secondly, a survey is performed among participating students. This approach facilitates an analysis of the teaching material and the learning event.

Using the frameworks of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016) and Bloom’s revised taxonomy of learning (Bloom, Citation1956; Krathwohl, Citation2002), the audit teaching material is found to be sufficient in terms of quality and adequacy for its use in HEIs, yet some suggestions for its improvement are provided. For evaluating the students’ perspective on the learning event, we use a CEQ (Course Evaluation Questionnaire). In detail, we observe an average degree of satisfaction with the learning event of 80.49% which indicates a clearly positive assessment. Combined, these findings indicate that the audit teaching resource as applied within the international seminars (ISPs) is suitable for use in HEIs. Furthermore, this research is relevant to other accounting educators, researchers and learners, as well as curricula designing bodies in HEIs.

1.1. Contribution

Our paper contributes to the existing literature by evaluating a new teaching concept in auditing and its usage considering existing accounting education literature. Following Bundsgaard and Hansen (Citation2011), our paper adds to the literature that evaluates learning material as a text and in a particular situation. Conducting research on auditing education is of relevance as there is a trend to a stagnation of educational accounting research (Rebele & St. Pierre, Citation2015). Although within the last years, the number of empirical studies on accounting education has increased moderately (Apostolou et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Apostolou et al., Citation2019). As much of the research in this area was normative or conceptual, (Apostolou et al., Citation2017), we are responding to the need for more (empirical) research (Pincus et al., Citation2017). Especially in our research field, Apostolou et al. (Citation2018) see huge future research potential on adapting accounting education to the changing needs of the accounting profession.

Nevertheless, our paper serves the need for more empirical research. Therefore, empirical evidence is provided regarding the quality of the teaching concept, as well as its use, evaluated by students. In general, this study aims to raise awareness of the teaching resource and its use in auditing classes. This study is of interest to accounting educators worldwide, but particularly in Europe, as a learning concept with content specifically relevant for Europe is analysed.

1.2. Structure of the paper

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, a brief literature review is presented. Section three contains the research design and method. The fourth section comprises an evaluation of the analysed teaching resource. The paper ends with a discussion of the results and a conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. Need for auditing education

Accounting education aims to provide a learning environment that fosters high-quality learning (Booth et al., Citation1999) and plays a major role in the development of accounting professionals (Asonitou, Citation2015). For the development of students’ technical skills, it is highly relevant that accounting educators are aware of the educational approaches which can be used (Boyce et al., Citation2001). Nowadays, students can often find accounting education dull and boring (Suwardy et al., Citation2013) and a career in the auditing profession is feared to be increasingly less attractive (Accountancy Europe, Citation2017). Accounting education could attract and motivate more students if both educator-centred teaching and diversified learning approaches are employed (AAA, Citation1986; Adler & Milne, Citation1997; AECC, Citation1990; Crawford et al., Citation2011; IFAC, Citation1996; Milne & McConnell, Citation2001; Wynn-Williams et al., Citation2008). Former studies (for example, see Argyris, Citation1980; Easton, Citation1992; Hassall et al., Citation1998; Libby, Citation1991; Stephenson, Citation2017) suggest that ‘active’, competency-based and student-centred teaching approaches positively affect the students’ knowledge and skills, as well as their understanding of, and interest in, accounting topics. In this regard, Jaijairam (Citation2012) explores numerous educational approaches that accounting educators have successfully used to make accounting education more attractive and enlightening for students (for experiential education see Butler et al., Citation2019 or Dombrowski et al., Citation2013). He finds methods, including blended learning, games, mentorships, internet research together with computer simulations and activity-based modules, have been successfully implemented in accounting courses. Using these methods allows students to analyse real-life accounting situations whilst improving both their academic achievements and their relevant knowledge. Case study teaching in accounting education helps the students to develop a range of special and interactive skills (for example, see Argyris, Citation1980; Easton, Citation1992; Hassall et al., Citation1998; Libby, Citation1991; Plant et al., Citation2019; Rebele & St. Pierre, Citation2019).

Hence, HEIs have both an opportunity and a duty to address these educational challenges, to provide an appealing and adequate education. Guidance for educators and HEIs can be found in various frameworks and has been the subject of revision in recent years. Specifically, the ‘Framework for International Education Standards for Professional Accountants and Aspiring Professional Accountants’ (IFAC, Citation2015) and the ‘AICPA Core Competency Framework’ of the American Accounting Association’s Pathways Commission (AAAPC, Citation2014) are internationally well-known.

2.2. Case-based-learning in accounting

In the mid-1980s, the AAA report (AAA, Citation1986) stated that accounting courses should aim to develop students’ capacities for analysis, synthesis, problem-based working and communication. Generally speaking, accounting educators can use a variety of in-class teaching methods, such as text reading, (interactive) lectures, case study solving, and discussions (for example, see Bonner, Citation1999). Several studies show, in detail, how problem-based learning methods could be used by HEIs (for example, see Albanese & Mitchell, Citation1993; Engel, Citation1991; Knyviene, Citation2014; Margetson, Citation1994; Schmidt, Citation1983; Shugan, Citation2006; Stephien & Gallagher, Citation1993; Taylor et al., Citation2018). Despite accounting education’s aforementioned history of research and development, there remains a high demand for further modification (Accountancy Europe, Citation2017). Notwithstanding, the use of case studies has become popular in teaching, as it represents a suitable method to connect theoretical knowledge with practice (also Weil et al., Citation2004). Boyce et al. (Citation2001) argue that a key advantage of the case study method is dealing with practical and theoretical questions. Students who are used to solving case studies tend to be better prepared for their future careers, as their problem-solving skills are enhanced (Saunders & Machell, Citation2000). Plant et al. (Citation2019) show that the development of skills, such as adaptability, communication, critical thinking, time management, self-management and teamwork are important for preparing work-ready graduates. From the employers’ perspective, accounting graduates should bring along team skills, leadership potential, verbal communication and interpersonal skills (Jackling & De Lange, Citation2009).

A case study approach can encourage students and educators to participate in direct discussion, as opposed to the lecture method. Subsequently, students develop their problem-solving skills, while the educator gives basic advice, enacting an active guide if necessary. The focus of case study learning is on improving the students’ abilities and knowledge through their joint, co-operative efforts.

Knyviene (Citation2014) summarises various studies (specifically, Ballantine & McCourt, Citation2004; Shugan, Citation2006; Wakil, Citation2008) and highlights the following benefits of case study-based learning for students:

rational benefits, as case studies can foster a better understanding of the phenomena and can facilitate greater proficiency in decision-making with imperfect information;

affective benefits, as case studies can stimulate higher motivation and interest in the subject, in addition to building confidence and greater commitment to learning achievements;

practical benefits, as case studies can improve various skills, such as data analysis (for the increased importance of technical issues in accounting education see Rebele & St. Pierre, Citation2019), verbal communication skills, written skills, and reasoning and judgement skills.

Hence, the case study approach is very effective by combining students’ theoretical knowledge with real-life topics. When using case study learning, students usually have to analyse, evaluate and develop solutions for a special case, thereby enhancing their problem-solving skills.

2.3. Evaluating learning methods and concepts

Evaluating learning material is important, as students tend to spend more time learning from textbooks and other learning material than they do from their teachers (Gall, Citation1981). To optimise the use of a curriculum, resource or concept, they must be evaluated (Eden, Citation1984; European University Association, Citation2019). The concept of evaluation itself is very complex, and according to Scriven (Citation1991), it should consist of a systematic and objective process of identifying an object or concept’s degree of worthiness. A number of studies deal with the evaluation of teaching (methods). For example, Bundsgaard and Hansen (Citation2011) distinguish amongst (1) studies with a focus on the learning materials as texts; (2) studies with a focus on teachers’ evaluation of learning materials; (3) studies with a focus on evaluating learning materials in particular situations.

2.3.1. Framework for evaluating learning material

Various approaches to evaluate learning material exist (e.g. Bundsgaard & Hansen, Citation2011; Gastel, Citation1991; James et al., Citation2019; Stark-Wroblewski et al., Citation2007). One of them was developed by Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016).Footnote2 According to their framework for preparing a qualitatively valid teaching concept, five questions must be answered:

Why is this topic/content of interest/ being taught?

Who will be teaching? Who will be learning?

Which topics/content will be addressed? What should be learned?

Which methods will be used?

How can the teaching concept be improved?

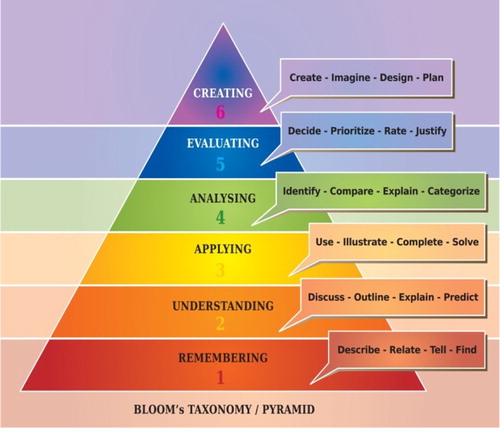

Whereas this concept mostly deals with the design of the teaching material, other concepts have to be applied to assess the content of teaching materials. One of the basic frameworks for assessing the compliance of tasks with learning objectives is Bloom’s taxonomy of learning (Bloom et al., Citation1956). Bloom’s taxonomy of learning was originally developed to provide a theoretical framework for learning assessment and the testing of learning materials (Tyran, Citation2010), which was later adapted by Krathwohl (Citation2002). According to the revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy, the hierarchical learning levels shown in represent stages to progressively target.Footnote3

As shows, the lowest learning level requires the lowest development of knowledge; the higher the hierarchy level, the higher the need for the development of knowledge (Pappas et al., Citation2013). A general assumption underlying the classifications of the cognitive taxonomy is that developing higher-level learning skills necessitates lower-level skills as a prerequisite (Krathwohl, Citation2002). For creating higher-level thinking skills (e.g. decision-making in varying situations, or creating new knowledge in the form of suggestions on how to improve the current practical or legislative situation), lower-level knowledge (e.g. knowing facts about auditing and being able to discuss auditing issues) must be acquired first (Erskine et al., Citation1998).

The taxonomy can help educators to build upon the wide range of cognitive skill levels associated with learning. By considering the different cognitive levels when designing a learning concept, an educator can develop a teaching plan that will consider a student’s smooth progression from the lower to the higher cognitive levels.

2.3.2. Framework for evaluating learning events

In addition to the design of teaching material, the use of concepts also has to be subject to evaluation to provide information about the quality of a teaching concept. Such an evaluation is very complex and requires gathering individual reactions to the particular situation (Bundsgaard & Hansen, Citation2011). In that regard, evaluation is an important topic in educational literature and specifically from the educators’ perspective evaluation should take place (Harrison & Jakubec, Citation2015). To our knowledge, no standardised format of evaluation of learning events exist, e.g. this could take the form of a combination of concept design outcomes and students’ evaluation.

To gather students’ perspectives in order to help evaluate learning events, a CEQ can be used. Evaluation using CEQs (for example, see Burden & Fraser, Citation1994; Byrne & Flood, Citation2010; Griffin et al., Citation2003; McInnis et al., Citation2001; Moafian & Pishghadam, Citation2009; Rentoul & Fraser, Citation1983; SES National Report, Citation2017; Talukdar et al., Citation2013) and factor analysis (for example, see Johnson & Stevens, Citation2001; Meyer et al., Citation1990) is intensively discussed in the literature. Specifically, CEQs are often used in Australia, with results and methodologies being publicly available (Byrne & Flood, Citation2010). Similar concepts are also common in European countries to measure a course’s ‘quality’, but it seems that only individual CEQ-results are available, not aggregated reports. Students’ assessment of their learning environment and their engagement are relevant for accounting education research (Taylor et al., Citation2018), as they depict the opinion of the most relevant group of ‘stakeholders’ of learning materials.

3. Research design and method

3.1. Research method and question

Against this background, the ILPA audit teaching concept is evaluated, to give an opinion on, and to suggest improvements to, the learning material and its application. This paper aims to answer the research question: Does an innovative audit teaching concept and its application provide the required level of quality and adequacy for its purpose as a teaching resource for use in a higher education setting? This paper aims to answer the following ‘sub-questions’:

How do the teaching materials fulfil the criteria developed in the education literature?

How do students assess the use of the teaching materials during specific learning events?

As the research method for this project, Yin’s (Citation2014) ‘case study’ approach is employed.Footnote4 Case study methodologies are often used in educational research, but there is still no full consensus about design and implementation (Yazan, Citation2015). In that context, Yazan (Citation2015) analysed the three different case study approaches from Yin (Citation2002), Merriam (Citation1998) and Stake (Citation1995) and pointed out the importance of developing a research design robust enough to address the particular research question.

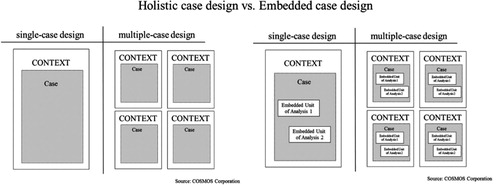

Case study research offers the chance to analyse a snapshot of real life and particularities (Gummesson, Citation2007) but may also be criticised for not providing generalisable results (e.g. Gerring, Citation2007). Yin’s (Citation2014) approach distinguishes between a holistic and an embedded case design and requires researchers to consider if it is pertinent to choose a single-case or a multiple-case design. If a study includes more than one single case, a multiple case study is needed. Single cases and multiple cases can be holistic or embedded. A holistic case is one where the case is the unit of analysis; an embedded case design is where there are several units of analysis in the case. This is represented in .Footnote5

Figure 2. Holistic vs. Embedded Case Design by Yin (Citation2014).

For our research, a single case study research design, with embedded units, is applied. Therefore, Yin’s (Citation2014) essential requirements in conducting case study research can serve as a fundamental framework. Yin (Citation2014) explains how researchers can deal with case studies as a research approach, especially how studies must define the case being studied, how to determine the relevant data to be collected and what to do with the collected data.

3.2. Unit of analysis

The following concepts are chosen as frameworks for evaluation due to their international use and their applicability to this case. Firstly, to assess the quality of the learning material, Spindler and Lohner’s (Citation2016) concept is used. Then, Bloom’s (Citation1956) taxonomy of learning revised by Krathwohl (Citation2002) is applied to evaluate the adequacy of the learning objectives and tasks. Aligning learning objectives and tasks is specifically relevant, as a proper preparation of students should be achieved (Rebele & St. Pierre, Citation2019). Secondly, a CEQ is used to capture the students’ feedback on the learning event.

The ILPA audit teaching material is the main unit of analysis. The Erasmus+ strategic partnership ILPA developed a teaching concept in accountancy.Footnote6 This teaching concept included various aspects of accounting, including financial reporting, auditing of financial statements, financial statement analysis, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting. By developing this teaching resource, the project team aims to increase the quality of accounting education. The ILPA learning resource claims to be unique and innovative, as the case studies are original, they address various levels of learning (in congruence with Bloom’s taxonomy of learning), and they give learners the opportunity to develop relevant, practical competencies. In September 2018, the project was chosen to be a Good Practice ExampleFootnote7 for Erasmus+ strategic partnerships on a European level.Footnote8 Hence, the project was assessed to be innovative, student-focused, and complementary to former projects. Therefore, evaluating the project’s output and sharing the results is relevant.

While the audit teaching concept is the ‘single case’, the audit teaching material and the learning events using this concept are the ‘embedded units’ (hereinafter subunits) of analysis. This is illustrated in .

3.2.1. The audit teaching materials

The first subunit of analysis is the audit teaching resource which intends to deliver competency-based knowledge, applicable in auditing education. The audit teaching resource consists of the audit teaching materials and notes how to use these materials. One of the units of analysis is the audit teaching material as adopted in international learning events.Footnote9 The audit teaching material consists of the following components:

audit teaching case;

a suggested solution for the audit teaching case (for educators);

instructional notes (for educators);

summary of key points (for educators);

basics about auditing (preparatory readings);

presentation slides, including an introduction about auditing and the tasks to be fulfilled (introductory presentation);

relevant International Standards on Auditing (ISA) (preparatory readings).

The core of the teaching material for auditing is a case on client acceptance decision-making and materiality decision-making. The case consists of information about the auditor, the audited company (4-Airlines), the industry, the predecessor auditor, and the financial statements.

The material was tested during specific, international Intensive Study Programmes (ISPs) but is basically designed for seminars in advanced-level Bachelor courses and Master Studies.

3.2.2. The learning events

The second subunit of analysis is a series of three learning events (ISPs). The ISPs were organised as international seminars and took place at three universities in Europe. The first event was in October 2015, the second in October 2016, and the third in June 2017. Within these learning events, the ILPA audit teaching material was applied. Besides the organisational details of the events, the section also includes educators’ perceptionsFootnote10 of the learning events.

3.2.2.1. Participants

Students and academics from up to 13 different universities attended the learning events (See ). In total, 218 students (ranging between 68 and 79 students per event) and 25 academics (per event) participated in the three learning events. The project partner universities brought between two and fifteen students to participate in the ISPs. This ensured that diverse, international groups of students could be formed. The students were chosen based on their interest and knowledge in accountancy, as well as their academic performance. The students had already completed between two and twelve accounting courses before being involved in the ISP. On average, they had gathered about 47 ECTS in accountancy and had completed about six accounting subjects beforehand. This is equal to about one and a half semesters-worth of prior accountancy education. This might indicate that the students had adequate technical accounting skills that should enable them to solve complex accountancy tasks.Footnote11 We define accountancy education in line with Apostolou et al. (Citation2018, Citation2019) as courses on Financial Accounting, Management/Cost Accounting, Taxation, Auditing and Ethics in the Accounting context. Hence, all students involved were quite well educated in accounting, but their focus and elected courses differed. To bridge these differences in accounting focus, the project team developed prior reading and introductory materials. These materials were given to the students as pre-class, self-study material in order for the group to reach a more homogeneous level of knowledge.

3.2.2.2. Schedule

The ISPs were not only about auditing but also about other accounting topics. The auditing section was either on the second and third day or the third and fourth day of each of the three learning events (ISPs). This was decided due to the logic of accountancy: first, the financial statement is prepared and afterwards, it is audited. Regarding the time-frame, about five to six hours were available for solving the audit teaching case and for preparation of the presentations. Also, about 30–45 min were available for the lecture-type introduction, two hours for the final presentations, and about one and a half hours’ worth of breaks.

At the beginning of the learning event, a short introduction about auditing basics and the tasks was given by the educators. After this lecture-type introduction, students worked on the case study in groups and prepared a short (PowerPoint) presentation of their solutions. As it is typical for case study learning, the students autonomously read the cases, processed the information, and developed initial ideas for solving the problems. Whilst solving the cases, students were given instructions and guidance from the educators as far as was needed.

As a final step, the students had to present their solutions, using a computer or other presentational tools. The presentation either took place in-class or in a plenum, together with other groups dealing with the same topic and interested educators. The learning environment enabled all students to contribute to the final presentation. The task of the educator was to moderate the presentations and the rounds of questions. The educators also had to summarise the results and present the key facts of the suggested results (included in the instructional materials).

3.2.2.3. Teamwork

The students formed three or four cohorts of 17–26 students and each cohort was supervised by two educators. The cohorts were subdivided into smaller teams of three to five students who worked on the audit case autonomously. Therefore, they needed various skills, such as technical auditing skills, English language skills, teamwork skills and problem-solving skills.

Regarding the small student teams, different educators used different techniques for team-building. Some educators asked the students to form groups on their own, whereas others decided on the members of each smaller team (e.g. by counting or random assignment). One important factor when forming a team was internationality. As the participants came from up to thirteen different universities (thus countries), mixing up the students was essential. The educators gave additional hints and individual support to the students. The educator-to-student ratio enabled the intensive support of the students as well as in-depth discussions within smaller international teams.

3.2.2.4. Learning environment

The physical facilities varied at the three universities. Whereas some rooms had computers, others included a meeting desk, enabling a circle layout for discussions. Layouts which did not enable proper group work were usually rearranged. Educators and students were flexible regarding rearrangement and organisation of the facilities. Educators were informed about the seminar rooms in advance and therefore could inform the students if they needed to bring laptops with them.

From the educators’ perspectives, the following organisational challenges arose regarding the learning event. As the ISPs took place at three different universities, familiarising themselves with the computer environment and room-specific issues were of crucial importance. For a positive learning environment (for example, see Erskine et al., Citation1998), the following issues are relevant (among others): timeframe; teaching arrangement; physical facilities; and arrangement of groups. Additionally, for the analysed ILPA learning event, the context of the international seminars was also found to be relevant, as the experience stimulates the effects of problem-based case study learning. Besides, getting to know each other through ‘country presentations’ or ‘warm-up games’ was important for team-building. Hence, it is of importance to include these kinds of activities in such an international seminar.

From the educators’ perspectives, the learning events were well organised. Meetings before and following the use of the material took place, and constant improvements were made. Therefore, for the specific setting, the learning material was applicable and was constantly improved from 2015 to 2017 to foster the students’ learning experiences.

3.2.2.5. Teaching arrangement

Concerning the teaching arrangements, the team-teaching partners were assigned a couple of weeks in advance of the ISP. That time was used to clarify the individual ‘roadmap’ for using the audit teaching material. The teaching-teams mostly remained the same throughout the three ISPs. In total, eight educators were involved in preparing and teaching the audit teaching case. Before and after the audit material was used in each ISP, meetings took place to discuss the ‘common’ roadmap for all the teams as well as the experiences gained. Following every ISP, the potential for improvement was identified and implemented before the next project meeting. Specifically, the degree of accuracy of the solution; the instructional notes; the content of auditing basics; the introductory presentation; and the timetable were all adapted.

As aforementioned, the group arrangement enables small group learning and intensive coaching, as the educator-to-student ratio was approximately two to nineteen. Hence, the teaching arrangement can be assessed as optimal, but unrealistic for regular use. The authors’ experience, as well as the discussion with other educators, revealed that a team-teaching situation for approximately twenty students is quite unusual, due to budgetary reasons. The group of educators agreed that the teaching (material) resources might be well-applicable for seminars with an educator-to-student ratio of one to 25. The team-teaching situation at the ISPs was mainly chosen to test the teaching material, to collect feedback and enable optimal student support. Team-teaching leads to multiple educators’ involvement; capturing, sharing and discussing their insights for constant improvement. From the educators’ perspectives, this teaching arrangement was assessed as positive, as it enables intensive and in-depth coaching of the students and collecting information for improving the teaching case and resources. This led to active participation from most of the students.

3.2.2.6. Educators’ perception of relevant capabilities

Crucial factors that were observable during the learning events were the students’ problem-solving competence and autonomous problem-solving skills. These competencies differed between students from different countries. While many of the students had former experience with case study learning, students from some countries, such as Hungary and France, were more used to lecture-based teaching. Therefore, for the other group members and the educators, it was important to deal with the different levels of autonomous problem-solving skills among the groups. These students often required more support from educators to structure the problem and apply existing knowledge. For these students, solving a case study which addressed high learning levels was a very challenging task. This also led to different allocation of roles for the participating students; students with highly evolved problem-solving skills tended to take the role of an educator.

As aforementioned, important competencies, such as the problem-solving, judgement and structuring capability, were at different stages of development. Yet, certain competencies also seemed to increase throughout the learning event (e.g. confidence, time management, task sorting, group work and communication). This shows that the students were willing to learn something new, met the requirements and were open to new experiences.

Further, an international group of students has different needs, capabilities, learning styles and ways of dealing with new ‘challenges’. Hence, it was demanding for students to solve cases in a (for most of the students) foreign language. English language skills were critical in the international environment. As the project team identified different levels of English knowledge, a glossary was developed after the first ISP in 2015, including the main relevant words and their descriptions in English as well as other European languages (German, Romanian, Spanish, French, Lithuanian, Hungarian and Greek). This glossary aims to simplify communication between students. As English was not the dominant native language, the students were encouraged to speak English throughout the learning event. Particularly for the larger non-English-speaking groups, this was a challenge.

Besides the development of various skills, the programme was designed to encourage students to develop international networks and to gain an impression of what international teamwork might look like. Most group members actively participated in solving the audit teaching case. When creating the presentations within their groups (not in the plenum), nearly every student had to carry out a task and be actively involved in the discussion.

3.3. Data collection

3.3.1. Teaching material

The evaluation of the teaching material was conducted in two stages. As aforementioned, we have chosen this approach as evaluating teaching material is highly relevant in higher education (e.g. Bundsgaard & Hansen, Citation2011; Gastel, Citation1991; James et al., Citation2019; Stark-Wroblewski et al., Citation2007).

3.3.1.1. Framework of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016)

Firstly, a content analysis was conducted answering Spindler and Lohner’s (Citation2016) five questions for properly developed teaching materials. The approach of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016) was chosen as it provides a simple guide for educators when designing teaching material. An analysis was performed on the documents listed below to answer the five questions raised by Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016). .

Table 1. Reviewed documents.

In the first step, categories of potential answers were developed for each of the five questions. Then, the documents were read and the content was aligned to the categories. If needed, additional categories were added. After an initial round of aligning the content to the categories, a meeting of the researchers took place and the results were discussed and refined. Information about categories and paraphrases can be found in Appendix 2.

3.3.1.1. Aligning learning objectives

Secondly, the learning objectives and tasks were analysed regarding their compliance with Bloom’s taxonomy of learning (version: Krathwohl, Citation2002). In the current literature, Rebele and St. Pierre (Citation2019) point out the relevancy of balanced learning objectives for accounting education. For our analysis we proceed as follows. Using prior literature (for example, see Krathwohl, Citation2002), paraphrases (see )Footnote12 within the learning objectives and tasks are identified which indicate the learning levels. Two of the authors autonomously attributed the learning levels to the learning objectives and tasks included in the audit teaching materials, in line with the identified phrases (see and ). The list of phrases was the primary decision basis. Additionally, when disagreements occurred, the suggested solutions were used as a basis for the decision. The decision-making process was documented and the results were discussed with all the authors.

3.3.2. Learning event

For evaluating the learning event, the students’ perspective was captured using a survey. This serves the need to not only focus on the educators’ perspective (for example, see Abraham, Citation2006) but to also include the students’ perspectives, which is a critical success factor (Bobe & Cooper, Citation2018). The survey uses a CEQ (Cannon, Citation2001). Results from the CEQ should illustrate the applicability of the audit teaching resources in specific teaching events. The reviewed literature serves as a basis for the questions included in the survey. Evaluation using CEQs is broadly discussed in the literature (for example, see Byrne & Flood, Citation2010; Griffin et al., Citation2003; McInnis et al., Citation2001; SES National Report, Citation2017; Talukdar et al., Citation2013).

After a thorough review of the literature, the methodology used in the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) for the Australian Student Experience SurveyFootnote13 (SES) for calculating indicators was adopted. Adapted from Griffin et al. (Citation2003), students were asked to assess: (1) course organisation (CO); (2) student support (StS); (3) learning resources (LR); (4) graduate qualities (GQ); and (5) intellectual motivation (IM). Additionally, the students had to assess their prior knowledge and the group work situation; in addition an open question was included, so the students had the possibility to make individual remarks.

4. Evaluating the ILPA audit teaching concept

4.1. Evaluating the audit teaching material

In the following section, the teaching material is analysed using content analysis, considering the framework developed by Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016). Afterwards, the learning objectives and tasks are analysed referring to Bloom’s revised taxonomy of learning (Bloom, Citation1956; Krathwohl, Citation2002).

4.1.1. Framework of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016)

The following paragraphs present a summary on whether the concept fulfils the requirements of Spindler and Lohner’s (Citation2016) framework.Footnote14 We have determined the topics to be covered by the project consortium and used a content analysis to collect and structure the information available to conduct a concise analysis of the audit teaching concept.Footnote15

Question 1: Why is this topic/content of interest/ being taught?

Question 2: Who will be teaching? Who will be the learners?

Question 3: Which topics/contents will be addressed? What should be learned?

Question 4: Which teaching methods will be used?

listening to a lecture;

conducting oral presentations and answering questions;

solving unstructured cases;

discussing issues with other students;

pre-class reading;

if needed, conducting research (e.g. legal background, additional industry information).

Question 5: How can the concept be improved?

The educators also shared their experiences, therefore improving the teaching material as well as its use. Hence, the concept has been properly tested and continuously improved by the project team.

Summary

The following table shows a summary of topics identified within the content analysis. As described in the previous section, various documents were reviewed to identify how the people who develop the cases addressed the questions of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016). .

Table 2. Summary of identified topics.

The previous explanations show that the ILPA project team accounted for all the questions raised by Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016). There is clear reasoning behind teaching the topic/content; the positions of the learners and educators; the specific topics; and the didactical methods which have been used. How feedback circles take place and how regular improvements (suggested by both learners and educators) are made has also been described.

4.1.2. Learning objectives addressed in the audit teaching case

As aforementioned, case studies are used to create new knowledge and competencies relevant in the auditing profession. Which learning levels are targeted and whether the targeted levels and the tasks comply with each other are analysed.

4.1.2.1. Analysed objects

When designing valuable case/teaching concepts, learning objectives and tasks should align, to have a stringent teaching concept. Hence, aligned learning objectives and tasks indicate a high-quality teaching concept.

In this research, the audit teaching case includes a broad range of information that has to be processed by the students and the learning levels targeted in the tasks include analysing, evaluating and creating knowledge. This indicates that the teaching case can be assessed as complex and the tasks are very demanding. In total, the audit teaching case deals with sixteen learning objectives and fourteen tasks. The following table sums up an assessment of the learning levels addressed by the learning objectives and tasks.Footnote16 .

Table 3. Summary of learning levels.

This summary shows the separately assessed learning objectives and tasks. We have used the paraphrases shown in to identify the relevant learning levels for both learning objectives () and tasks (). The procedures we have followed are described in section 3.3.1.

4.1.2.2. Results

It is found that the learning objectives mainly aim at understanding, applying, analysing and evaluating issues, whereas remembering and creating play a minor role. Hence, the learning objectives and tasks seem to be balanced. An analysis of the tasks demonstrates that they require the application of existing (high-level) knowledge. also illustrates that the tasks address a higher learning level than the learning objectives do. When scrutinising the classification of tasks and learning objectives, it is found that the teaching case itself does not explicitly target the lower learning levels, while the additional learning materials (introduction into auditing and the introductory presentation) do. Consequently, solving the audit teaching case should follow the procedure described in the instructional notes.

Hence, we find a minor misalignment of the learning objectives and tasks. For optimal use of the teaching material, it is recommended that those preparing the audit teaching case specifically emphasise the pre-class reading and background information in the teaching case (to inform students) and in the instructional notes (to inform the educators).

4.2. Evaluating the learning event

From an educators’ perspective, it has been shown that the teaching material fulfils the criteria derived from the literature. However, not only the educators, but even students usually (especially at the end of their study programmes according to their specialisation) assess the quality of a teaching concept; thus they strongly affect the future existence of seminars and courses, due to their future areas of responsibility and the expectations of future employers (on the question of whether graduates meet the expectations of employers see Jackling & De Lange, Citation2009). Therefore, the students were asked to assess the teaching material. Evaluating the students’ perspectives seems to be appropriate to (1) include non-educator perspectives and to (2) show that a concept like this is positively assessed by the learners, therefore indicating that this type of concept is in demand by students.Footnote17 Furthermore, Abraham (Citation2006) pointed out that students’ perspectives are important for a proper evaluation of teaching material. In current accounting education research, students have already been identified as important stakeholders (Alderman et al., Citation2012) and therefore, information regarding their experience is regularly requested.

4.2.1. Participants

As previously illustrated, a total of 218 students participated in the ISPs. 173 took part in the survey to assess the learning events. These students came from thirteen different countries from Europe and the USA and were mostly following their Master studies. The majority were not native English speakers. Between two and fifteen students from each university participated in each learning event. In terms of the ISPs, shows details about the participants.

Table 4. Responses and participants.

In total, the response rate was 79.36%. This rate is likely to have been influenced, in part, by organisational issues which occurred during the ISP in Kavala which caused not all the students to receive the questionnaires. For the other events, the questionnaires were given to all the students present on the last day of the event. Notwithstanding, they could decide not to answer the questionnaires, so a self-selection bias might occur.

4.2.2. The CEQ

To test the structure of the CEQ, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA)Footnote18 was conducted. EFA is a widely used factor model, in which manifest variables are a function of unique factors, common factors and errors of measurement. When using the EFA technique, results for identifying the common factors and the related observable variables should be reached. Performing factorial analysis requires several important decisions to be made by the analyst, as there is no one set method (Janssen & Laatz, Citation2017).

In detail, a factor analysis has been conducted, using the principal component method and varimax rotation (KMO = 0.764, Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 700,202, significant 0.000). These analyses revealed five factors. Then, Cronbach’s alpha statistic was used to determine the degree of consistency among the measurements of every construct. Each construct of the survey exceeded the acceptable level (0.7) of Cronbach’s alpha. The results of the factor analysis are summarised in the following table: .

Table 5. Summary of results (data quality).

In , a list of the questions that were included in the questionnaire, the indicator to which they belong, and the results of the factorial analysis and Cronbach’s alpha can be found.

For answering the CEQ, a five-point Likert scale is used, whereby the following coding is applied. .

Table 6. Answer codes CEQ.

The categories strongly agree and agree are categorised as positive assessments. To avoid misunderstandings, smiley faces were used besides the written explanation to indicate agreement or disagreement. Following prior literature (for example, see SES National Report, Citation2017), the indicators were calculated using the following formula:

4.2.3. Analysis of CEQ indicators

Next, descriptive statistics about the CEQ indicatorsFootnote19 are shown:Footnote20 .

Table 7. CEQ Data and Indicators.

The descriptive statistics show that most of the students answered the questions from each category with 1 – which stands for strongly agree. Considering the assessment illustrated previously, the descriptive analysis displays a mostly positive assessment of all the topics. That indicates that the students, in general, assess the learning event as positive. Overall, the degree of satisfaction is about 80.49% which exceeds the values interpreted as clearly positive in the SES National Report Citation2017. Hence, satisfaction with the events can be rated as very high as this indicates that 4 out of 5 students assessed the events as (very) positive.

When comparing the indicators from the ISPs, it can be observed that they are high, yet differences still occur. All ISPs show their own peaks in at least one category. The ISP in Budapest has two of these peaks; the event was assessed best for course organisation and student support. The ISP in Kavala had a peak for graduate quality, which was the highest value observed. The ISP in Vannes had two peaks which indicated that the intellectual motivation and the learning resources were assessed very positively. Overall it seems that all the events had positive assessments in at least one of the areas. One has also to recognise that the Vannes ISP had the lowest indicators for course organisation and student support. For the ISP in Kavala, course organisation and student support were assessed as comparably low. Therefore, the data show that the ISP in Budapest was assessed to be the best, as it had two top ratings and only one ‘flop’ rating, the latter still being above 80%. This means 4 out of 5 students were very satisfied or satisfied with the learning event.

To find out if differences are significant, a one-factorial ANOVA of the five indicators was conducted.Footnote21 .

Table 8. ANOVA.

In this regard, it is found that the students’ answers for only two indicators significantly differ among the ISPs. Particularly, the indicators course organisation and student support vary significantly between the events. As one can see in , these are the two indicators with the highest differences among the ISPs. These results are quite interesting as the timetable was basically the same, the same educators were engaged and similar instructions were given to the students. The same applies to the student support topics. Possibly, ‘environmental’ factors such as the ‘atmosphere’ of the events, which was much more relaxed in France and Greece, might have had an effect on the students’ evaluation.

Nevertheless, all participating students seem to have been equally satisfied with the graduate qualities and the learning resource. Additionally, all of them took away a high intellectual motivation from the ISPs, no matter which event they attended. This means that the ILPA case can be repeatedly used with the same assessment of the learning resources and similar (positive) effects on graduate qualities and intellectual motivation.Footnote22 Hence, the major technical input (learning resources) and the most important outputs (graduate qualities and intellectual motivation both referring to employability and skills) are stable among different learning events. Only the ‘environmental factors’ such as the support for the students and the course organisation differ. This indicates that the students still respond to facilities and organisational factors.Footnote23

4.2.4. Assessment of prior education

In addition to the questions analysed before, the students were asked about their prior education and the team work experience during the learning event.

The students assessed their prior education as shown in the following table: .

Table 9. Prior education.

Students self-assessed their prior knowledge as sufficient (70.5% of the students). That basically means that the majority of students assessed that they had enough prior knowledge for solving the cases. These results indicate that the students had sufficient prior knowledge so (1) the students did not feel overwhelmed by the tasks set and (2) the choice of participating students worked well.

However, compared to the other questions, the students seem to be quite critical about this question. Linked to the questions asking about Graduate Qualities, this might be a sign of students’ positive development throughout the ISP.

4.2.5. Organisation of the team work

Regarding the organisation of the learning event, solving case studies in teams was the suggested procedure. As the organisation of the case learning is a crucial factor for the success of the programme, questions about this issue were included in the questionnaire. In terms of group work, the students were asked if (1) ‘the group size was appropriate to efficiently work together on the case studies’ and if (2) ‘Everyone in my group engaged in the case studies and contributed to the final solutions’. .

Table 10. Team work.

Whereas approximately 86% of students agreed that the group size was appropriate, only 53.7% of students agreed that everybody in the group was equally engaged in solving the case study. Hence, the group size setting was assessed to be appropriate, but the answers also indicate that the students were not fully satisfied with the commitment of their team members. The group work questions were included, as (1) it is important in the specific setting of the applied learning resource and as (2) a(n) (im)proper group work arrangement may affect the learning results. This finding is in line with the educators’ perception, as not all students were satisfied with the group work situation – specifically the students remarked in the open question section that not everybody was working on the cases properly. For future learning events, it is recommended that the educators use techniques to encourage all the students to engage in the team work, e.g. tests or requiring the students to document the team members’ responsibilities.

4.2.6. Supplementary questions

At the end of the questionnaire, an open question was included to allow additional comments. About 40% of the students used the opportunity to leave some comments. The comments often refer to ‘environmental’ factors, such as the tough timetable, the social programme, the food or the languages used. This feedback was used to improve future learning events. The internationality of the event, the individual development and the motivating climate were mentioned to be positive. They also referred to other topics that might be of interest in the accounting context such as taxation or finance.

Hence, these findings are in line with the standardised part of the questionnaire.

4.3. Limitations

Using the case study research design facilitated a holistic view of the ILPA audit teaching material and its application in three international learning events. As with all research designs, the case study design is subject to various limitations. Although one can learn a lot from one specific case, the lack of generalisability is a common limitation.

Additionally, researcher subjectivity, external validity, reliability and replicability of single-case study analyses can all be seen as limitations. To reduce researcher subjectivity and improve replicability and reliability, categories were developed, the research was thoroughly documented and procedures and interpretations were discussed with all researchers involved. Regarding external validity, a broad range of research papers is used as a basis for remarks and analyses. To provide a sufficient case study quality, multiple sources of evidence are used to underpin the findings.

Further, students were highly engaged in the programme. We basically assume that similar students act similarly in comparable situations. But, within our analysis, we did not control for this high level engagement and for whether it is usual or unusual. Their engagement might be driven by their interest in accounting, and only secondarily by the activities. The learning events themselves are a very specific learning environment as they include both international and multicultural elements, which is relevant for the students’ engagement. Also the ratio of educators to students was very low, which indicates that the teaching concept was applied in a specific setting.

Against this background, the analysis conducted within this research is of interest for accounting educators and those in charge of changing/designing curricula at HEIs.

Additionally, the choice of frameworks for evaluation might affect the findings. The study is subject to the typical limitations of surveys. Specifically, as pointed out before, due to the method of data collection, a self-selection bias cannot be ruled out.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This paper has analysed the ILPA audit teaching material and its application within a learning event.

The teaching material (e.g. case, instructors’ materials, pre-class reading) was initially evaluated in light of the framework of Spindler and Lohner (Citation2016) to consider if the didactical objectives of the teaching concept were achieved. The analysis shows that the consortium thoroughly considered the potential use of the teaching material and its associated didactical needs. Consequently, the audit case and the supplementary materials were analysed in consideration of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. The audit case itself addresses high learning levels, so students do not just repeat existing knowledge, but they also analyse, evaluate and create new information. Hence, in light of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning, the case study-based approach might be suitable to achieve the learning levels. As far as the ILPA audit teaching material is concerned, it can be stated that it was prepared in a structured way that meets the demands of the accounting education literature and is therefore of sufficient quality to be used in its current form. Nevertheless, regarding the learning objectives and tasks, it is recommended to explicitly mention the preparation materials for the case and highlight the relevance of following the suggested procedures.

Secondly, the learning event was assessed by the students using a CEQ. This survey was conducted during three ISPs from 2015 to 2017. These ISPs were annual, specific learning events, which aimed to evaluate and improve the ILPA learning concept. In total, 173 students within the three ISPs assessed the teaching concept, equating to a response rate of approximately 80%. These results show a positive evaluation of all the indicators examined. In particular, the graduate qualities, learning resources and intellectual motivation were similarly, positively assessed throughout all ISPs.

Regarding the research question, one can state that (1) the teaching material fulfil the criteria developed in the chosen education literature and (2) from the students’ perspective the audit teaching concept as applied within a learning event, fulfil their academic needs. Combined this means that (1) the design of the audit teaching concept is in line with existing literature, (2) the suggestions of how to use it seem to be manageable and (3) its application fulfils the need of the targeted public. Therefore, this research is relevant for accounting educators not only regarding the assessment of the specific ILPA project, but also for a systematic, multi-perspective analysis of other teaching concepts.

Hence, it is found that that the audit teaching concept addresses the contemporary challenges of good auditing education, as it (1) focuses on the development of problem-solving skills, (2) enhances the skills required from graduates in the field, whilst also improving the current education situation in the field and (3) is positively assessed by educators (in terms of learning material and concept) and students (in terms of learning events). Based on these findings, it can be stated state that the audit teaching material developed throughout the ILPA project achieves the underlying requirements to be considered as an appropriate, useful, innovative and relevant teaching activity. These results imply, that adoption the ILPA audit teaching concept can facilitate a bundle of relevant graduate qualities. Further, public funding of projects like the ILPA project can lead to an increasing quantity and quality of accounting education. Further research (extending the work of Mandilas et al., Citation2014) could be conducted in the quad of market needs, student’s demands, curricula requirement and educational concepts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the attendants of the EAA 2018 Annual Congress and the AAA 2018 Annual Meeting as well as two anonymous reviewers, the associate editor and the editor-in-chief for their comments and suggestions that significantly improved the paper. Besides they thank the ILPA project team as well as all survey participants for their committment to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The teaching concept was developed as part of the Erasmus+ strategic partnership ILPA. A description is available in Appendix 1 and general information about the project is available at: http://ilpa-accounting.eu/; Accessed: 05/02/2020.

2 This framework is also used in Litterst et al. (Citation2018).

3 Source of the graph: https://sites.rhodes.edu/academicsupport/learning-multiple-levels, Accessed: 24/04/2020.

4 We use Yin’s case study approach, as it is broadly used in social sciences research, e.g. Google Scholar shows about 175,000 citations of his case study research book.

5 Yin (Citation2014), p 50.

6 Additional Information about the ILPA project is also available at: http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/fb1019fb-36ce-448a-bded-9d4faf5bf513; Accessed 07/02/2020.

7 A good practice example is a project that has been particularly well managed and can be a source of inspiration for others (see: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects_en#search/keyword=ilpa&matchAllCountries=false). The project was assessed to be a good practice example, as it was nominated for the Erasmus+ Award 2018 in Austria due to its high quality intellectual outputs. Projects were nominated for this Award based on the assessment of an international jury regarding their: (1) relevancy and strategy; (2) results innovativeness and implementation and their (3) impact and dissemination. The final report and the degree of fulfilling the quality criteria were the basis for the jurors’ decisions. (see: https://bildung.erasmusplus.at/fileadmin/Dokumente/bildung.erasmusplus.at/Veranstaltungen/2018/2018-12-04_Earsmus__Award_2018/WEB_20181128_Erasmus__Award_2018.pdf; p 7); Accessed 20/04/2020.

8 Information available at: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-AT01-KA203-000965 and https://bildung.erasmusplus.at/de/policy-support/verbreitung-und-nutzung-von-ergebnissen/erasmus-award/award2018/; Accessed 07/02/2020.

9 The auditing case (student’s version) is freely available at: ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/project-result-content/e4e68993-10d9-40ce-a328-9b21a4de0236/IO%201%20Audit%20Case%20Study.pdf; Accessed 24/07/2019.

10 This merely descriptive information was collected while one of the authors was in the position of instructor (educator), advising the students when solving the teaching case and preparing presentations. This facilitated perceiving the application of the teaching concept as an ‘insider’; such a perspective is highly valuable for depicting the material and analysing the students’ evaluation of the learning event. The focus during the participant observation fell upon the learning and teaching environment, the (perceived) students’ capabilities, and the most prevalent challenges. Information was captured as notes and formally discussed with other educators (within project meetings, preparatory meetings and debriefings) and informally (during dinners, bus rides and others).

11 We use prior accounting courses as a prerequisite, which is not unusual. For example Dombrowski et al. (Citation2013) explain in their paper the selection of staff (students) is based on their prior auditing education/auditing studies.

12 In line with Wilson (Citation2019), available at: https://thesecondprinciple.com/teaching-essentials/beyond-bloom-cognitive-taxonomy-revised/; Accessed [24/07/2019].

13 Available at: https://www.qilt.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ses-methodology-for-qilt-website-march-2018---pgc.docx?sfvrsn=f395e33c_2; Accessed [07/02/2020].

14 More detailed information about topics, phrases and where the information was found is included in Appendix 2, section 3.3.1 and .

15 The reviewed documents were the following: the quality report, the project application and the final project report.

16 More detailed tables, including the learning objectives and tasks, can be found in the appendices.

17 Based on the organisation of the European universities involved, we have found that the concept used would traditionally be applied in elective courses. Therefore the demand for these courses is mainly determined by students.

18 Exploratory factor analysis is a statistical method used to examine the underlying theoretical structure and to identify which factors are measured by several observed variables. It is also used to reduce relatively large sets of data into smaller sets. Moreover, exploratory factor analysis is commonly used to determine the existence and nature of the potential correlation between the variable and the respondent. This part of the analysis is conducted using SPSS (Janssen & Laatz, Citation2017).

19 The CEQ indicators equal the rate of agreement to the questions.

20 The highest values per indicator are highlighted in the table above, marked in bold (and red).

21 The significance is marked in bold (and red) in the table above.

22 Intellectual Motivation was measured using the assessment of three statements: (1) The programme was intellectually stimulating; (2) The programme enhanced my knowledge in accountancy; (3) The programme has increased my interest in a career in accountancy.

23 Similar satisfaction rates regarding the usefulness of case studies were found by Weil et al. (Citation2004) and Weil et al. (Citation2001), although their results reveal significant differences regarding gender- and language-based differences.

24 A description of the project can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-AT01-KA203-000965.

25 This information was included in the teaching notes of the audit teaching case.

26 Within the section “The Cognitive Domain”.

References

- Abraham, A. (2006). Teaching and learning in accounting education: students’ perceptions of the linkages between teaching context, approaches to learning and outcomes. Faculty of Commerce-Papers. University of Wollongong 210, 1–13.

- Accountancy Europe. (2017). Keeping the Audit Profession Attractive. Retrieved November 29, 2017, from https://www.accountancyeurope.eu/publications/keeping-audit-profession-attractive/

- Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC). (1990). Objectives of education for accountants: Position statement number one. Issues in Accounting Education, 2, 307–312.

- Adler, R. W., & Milne, M. J. (1997). Improving the quality of accounting students’ learning through action orientated learning tasks. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 6(3), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/096392897331442

- Albanese, M. A., & Mitchell, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: A review of the literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Academic Medicine, 68(1), 52–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199301000-00012

- Alderman, L., Towers, S., & Bannah, S. (2012). Student feedback systems in higher education: A focused literature review and environmental scan. Quality in Higher Education, 18(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2012.730714

- Alderman, L., Towers, S., Bannah, S., & Le Hoa, P. (2014). Reframing evaluation of learning and teaching: An approach to change. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 14(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035719X1401400104

- American Accounting Association (AAA). (1986). Committee on the future structure, content, and Scope of accounting education (The Bedford Committee), future accounting education: Preparing for the expanding profession. Issues in Accounting Education, 1, 168–195.

- American Accounting Association’s Pathways Commission (AAAPC). (2014). The official Pathways Commission summary, Retrieved November 29, 2017, from http://commons.aaahq.org/groups/2d690969a3/summary

- Apostolou, B., Dorminey, J. W., Hassel, J. M., & Hickey, A. (2019). Accounting education literature review (2018). Journal of Accounting Education, 47, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.02.001

- Apostolou, B., Dorminey, J. W., Hassel, J. M., & Rebele, J. M. (2017). Analysis of trends in the accounting education literature (1997–2016). Journal of Accounting Education, 41, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2017.09.003

- Apostolou, B., Dorminey, J. W., Hassel, J. M., & Rebele, J. M. (2018). Accounting education literature review (2017). Journal of Accounting Education, 43, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2018.02.001

- Argyris, C. (1980). Some limitations of the case method: Experiences in a management development programme. Academy of Management Reviews, 5(2), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1980.4288765

- Asonitou, S. (2015). Employability skills in higher education and the case of Greece. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1202

- Ballantine, J., & McCourt, L. (2004). A critical analysis of students’ perceptions of the usefulness of the case study method in an advanced management accounting module: The impact of relevant work experience. Accounting Education, 13(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280410001676885

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive Domain. David McKay Company.

- Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longmans, Green.

- Bobe, B. J., & Cooper, B. J. (2018). Accounting students’ perceptions of effective teaching and approaches to learning: Impact on overall student satisfaction. Accounting and Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12364

- Bonner, S. E. (1999). Choosing teaching methods based on learning objectives: An integrative framework. Issues in Accounting Education, 14(1), 11–39. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.1999.14.1.11

- Booth, P., Luckett, P., & Mladenovic, R. (1999). The quality of learning in accounting education: The impact of approaches to learning on academic performance. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 8(4), 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/096392899330801

- Boyce, G., Williams, S., Kelly, A., & Yee, H. (2001). Fostering deep and elaborative learning and generic (soft) skill development: The strategic use of case studies in accounting education. Accounting Education, 10(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280121889

- Bundsgaard, J., & Hansen, T. I. (2011). Evaluation of learning materials: A holistic framework. Journal of Learning Design, 4(4), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v4i4.87

- Burden, R., & Fraser, B. (1994). Examining teachers’ perceptions of their working environments: Introducing the School Level environment questionnaire. Educational Psychology in Practice, 10(2), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736940100201

- Butler, M. G., Church, K. S., & Spencer, A. W. (2019). Do, reflect, think, apply: Experiential education in accounting. Journal of Accounting Education, 48, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.05.001

- Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2010). Assessing the teaching quality of accounting programmes: An evaluation of the course experience questionnaire. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301668

- Cannon, R. (2001). Broadening the context for teaching evaluation. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 88(88), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.40

- Crawford, L., Helliar, C., Monk, E., & Stevenson, L. (2011). SCAM: Design of a learning and teaching resource. Accounting Forum, 35(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2010.08.008

- De Lange, P., Suwardy, T., & Mandovo, F. (2003). Integrating a virtual learning environment into an introductory accounting course: Determinants of student motivation. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963928032000064567

- Dombrowski, R. F., Smith, K. J., & Wood, B. G. (2013). Bridging the education-practice divide: The Salisbury University auditing internship program. Journal of Accounting Education, 31(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2012.12.003

- Easton, G. (1992). Learning from case studies. Prentice-Hall International.

- Eden, S. (1984). Evaluation of learning material. Internationale Schulbuchforschung, 6(3/4), 283–291. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43055436

- Engel, C. E. (1991). Not just a method but a way of learning. In D. Boud, & G. I. Feletti (Eds.), The challenge of problem-based learning. Kogan Page.

- Erskine, J. A., Leenders, M. R., Mauffette-Leenders, L. A., & Ivey, R. (1998). Teaching with cases. Ivey Publishing.

- Faello, J. (2016). Enhancing the learning experience in intermediate accounting. Research in Accounting Regulation, 28(2), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.racreg.2016.09.006

- Gall, M. D. (1981). Handbook for evaluating and Selecting curriculum materials. Allyn and Bacon.

- Gastel, B. (1991). A menu of approaches for evaluating your teaching. BioScience, 41(5), 342–345. https://doi.org/10.2307/1311589

- Gerring, J. (2007). The case study: What it is and what it does. In C. Boix, & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), Oxford Hand-book of Comparative Politics (pp. 90–122). Oxford University Press.

- Griffin, P., Coates, H., McInnis, C., & James, R. (2003). The development of an Extended course experience questionnaire. Quality in Higher Education, 9(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/135383203200015111

- Gummesson, E. (2007). Case study research and network theory: Birds of a feather. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 2(3), 226–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640710835373

- Harrison, M., & Jakubec, M. (2015). Evaluating learning activities: A design perspective. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 18(2), 84–98. https://www.eurodl.org/materials/special/2015/Oslo_Harrison_Jakubec.pdf

- Hassall, T., Lewis, S., & Broadbent, J. M. (1998). The use and potential abuse of case studies in accounting education. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 7(4), 37–S47. https://doi.org/10.1080/096392898331108

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (1996). Prequalification education, assessment of professional competence and experience requirements of professional accountants, international education Guideline No.9. International Federation of Accountants.

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). (2015). Meeting future expectations of professional competence: A consultation on the IAESB’S future strategies and priorities. Retrieved November 29, 2017, from https://www.ifac.org/publications-resources/consultation-paper-meeting-future-expectations-professional-competence

- Jackling, B., & De Lange, P. (2009). Do accounting graduates’ skills meet the expectations of employers? A matter of convergence or divergence. Accounting Education, 18(4-5), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639280902719341

- Jaijairam, P. (2012). Engaging accounting students: How to teach principles of accounting in creative and exciting ways. American Journal of Business Education, 1, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v5i1.6706

- James, D., Schraw, G., & Kuch, F. (2019). Assessment and evaluation in higher education: Using the margin of error statistic to examine the effects of aggregating student evaluations of teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(7), 1042–1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1570482

- Janssen, J., & Laatz, W. (2017). Statistische Datenanalyse mit SPSS: Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung [Statistical data analysis with SPSS: An application-oriented introduction]. Heidelberg.

- Johnson, B., & Stevens, J. J. (2001). Exploratory and Confirmatory factor analysis of the School Level environment questionnaire (SLEQ). Learning Environments Research, 4(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014486821714

- Knyviene, I. (2014). A new approach: The case study method in accounting. Economics and Management, 4, 158–168. https://doi.org/10.12846/j.em.2014.04.12

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

- Libby, P. A. (1991). Barriers to using cases in accounting education issues. Accounting Education, 6, 193–213. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=

- Litterst, L., Rheinsberg, Z., Spindler, M., Ehni, H.-J., Dietrich, J., & Müller, U. (2018). Ethics of biogerontology: A teaching concept. International Journal of Ethics Education, 3(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40889-018-0048-4

- Mandilas, A., Kourtidis, D., & Petasakis, Y. (2014). Accounting curriculum and market needs. Education and Training, 56(8/9), 776–794. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2013-0138