ABSTRACT

Critical thinking has been identified as a very important skill by employers for the employment of graduates. A need exists to develop and assess critical thinking skills in tertiary institutions as employers have noted a gap in these skills among graduates. This skill can be developed, over time, by collaborative learning and given that student assessment, to a large extent, drives student learning this study proposed a revised assessment format: the ‘partial pre-release’ (PPR) assessment to attempt to cultivate critical thinking skills through collaboration. The PPR provided a pre-released case study where students had the opportunity to collaborate with peers before the assessment day. New information presented to students on the assessment day required increased depth in answering to showcase the cultivation of critical thinking skills. Quantitative data were collected over a period of two years using a survey. The PPR assessment format was found to show a statistically significant relationship between collaboration and the level of perceived depth when answering the required task. From these results, the study acknowledges the role that collaborative learning can play in cultivating a critical thinking mindset when an appropriate assessment tool is used.

Introduction

The research question addressed in this study is: how does the implementation of a pre-release’ (PPR) assessment format contribute to cultivating critical thinking skills through collaboration among tertiary institution students?

Accounting professionals in practice have emphasised the importance of modifying traditional teaching and assessment methods to incorporate more collaborative group work to better develop more pervasive skills required from graduating students in the workplace to academics (AACSB, Citation2018; AICPA, Citation2011). Results reported from the current study can provide insight into how tertiary programmes can adapt its assessment format to be more competency-based to allow for better collaborative learning to take place which can assist in developing an improved critical thinking mindset when faced with problem-solving tasks.

The current study addressed the research objective through a quantitative research study consisting of 800 accounting students over a period of two years. Through the use of a survey, the perceptions from students were gathered to address the following three main hypotheses: whether collaboration with peers during the pre-released period assisted students (i) in increasing their level of preparedness, (ii) in having more depth and a better understanding of the case study, and (iii) whether this collaboration would have a positive impact on their academic performance. These three hypotheses respond to prior research studies which have supported that the level of preparedness and having more depth and a better understanding can cultivate critical thinking through collaborative learning (Altintas et al., Citation2014; Cadiz Dyball et al., Citation2010; Dean, Citation2015; Frame et al., Citation2015; Parsons et al., Citation2020; Sahd & Rudman, Citation2020).

In recent years it has become challenging for student learning and formal assessment to take place effectively. With the ever-increasing access to technology, and improvement in available software, many of the traditional tests of competence for a student are no longer relevant as they do not reflect the role which students will play within the workplace once graduating (De Villiers & Viviers, Citation2018). Even the International Education Standards 3 (IES 3) made reference to these changes challenging the competencies that are required of future professional accountants (IAESB, Citation2008) to meet the expectations of their future employers. This has already prompted a change from many professional bodies to place greater emphasis on pervasive skills and not only technical knowledge (Barac, Citation2009; Boritz & Carnaghan, Citation2003; Viviers, Citation2016; Wells et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2013). This gap however still exists at the tertiary institution level.

This study addresses the need for a competency-based assessment to address the need at the tertiary level. The PPR assessment was formulated as a competency-based assessment where a case study was given to students days before the final assessment and peer collaboration was encouraged. Students were presented with new information on the assessment day and the study determined whether collaboration helped cultivate a critical thinking mindset which assisted students in solving the case study problems on the final assessment date (Retnowati et al., Citation2018). The aim of this study is not to assert that critical thinking skills can be developed in a short ‘pre-released’ period but to acknowledge the role that collaborative learning can play in already cultivating a critical thinking mindset if an appropriate assessment tool is used. The paper acknowledges that students do not yet understand or know how to determine if the PPR assessment has helped in developing their critical thinking skills. Therefore, the objectives and hypotheses of the current study are structured to investigate the association that collaboration had with: ‘the level of preparedness’, ‘the level of depth’ and ‘the expected test result’ as the results of this perception would indicate whether the PPR assessment ignited the development of a critical thinking mindset. These research objectives are further supported in the hypotheses section that follows.

Contribution

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. Firstly, it has the potential to inform and improve learning practices specifically in developing a more critical thinking mindset which is considered an important graduating attribute in university accounting students. Secondly, it provides validation for the use of a PPR assessment format that encourages collaborative learning to help students develop a critical thinking mindset through being better prepared and being able to understand information required for assessments in more depth. Thirdly, the results also provide insight into the benefits of what students perceived the assessment to bring to their learning experience and therefore this assessment format represents a tool in which collaborative learning can take place to enhance a critical thinking mindset. Finally, the results may provide educators with an evaluation tool to shift students’ away from only concentrating on technical content to an increased focus on real-world application which incorporates an element of effective collaboration with fellow peers and a way in which to start cultivating a critical thinking mindset.

Background

The research problem of this study is driven by the need to educate students for the workplace (Barac, Citation2009; Viviers, Citation2016; Wells et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2013). This includes moving away from only teaching and assessing technical skills but also focussing on pervasive skills, such as critical thinking (Barac, Citation2009). The background section focuses on how important pervasive skills, such as critical thinking, are in the workplace. It further expands how these skills can be developed using an authentic assessment within an experiential learning framework.

Educating for the workplace

Numerous studies have investigated and commented on accounting students’ readiness to enter the workplace, paying special attention to the skills graduates require when they start working in the accounting profession. These studies found that pervasive skills are just as important, if not more important, than technical knowledge (Barac, Citation2009; Viviers, Citation2016; Wells et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2013). To address the change in business environments – including the pervasive skills required by the employers – many international professional bodies have advised professional programmes to depart from a knowledge-based training programme to a competency-based training approach. These include professional bodies such as the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand (ICANZ) and the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA). A few examples of the changes made by these professional bodies include, the Professional Accounting School (PAS) of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand (ICANZ) adopted competency-based training and assessment in 1998 as a new admission requirement for prospective professional accountants (Weil et al., Citation2004). The South African Institution of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) also moved to a competency-based training approach in 2010 (Barac, Citation2009; Viviers, Citation2016). This change led to the introduction of the assessment of professional competence (APC), where candidates are assessed in a competency-based manner instead of a technically focused qualifying examination. Furthermore, the International Accounting Education Standards Board (IAESB) revised International Education Standard 3 (Initial Professional Development – Professional Skills) that prescribes learning outcomes for professional skills of aspiring professional accountants in 2014 to include more pervasive skills. The revised IES 3 requires professional accountants to demonstrate professional competence at the end of their initial professional development. Professional accountants should be able to integrate the following professional skills with technical competence and professional values, ethics, and attitudes: intellectual skills, interpersonal and communication skills, personal skills, and organisational skills. From an educational perspective, this change to accounting education standards in 2014 further demonstrates the importance of moving from knowledge-based training to competency-based training.

Professional accounting bodies should distinguish between competencies, knowledge and understanding, practical application, and pervasive skills, and should note that all of the above should be addressed by academic providers (SAICA, Citation2020). Despite this fact, technical knowledge sometimes remains the focus of university training (Barac & Du Plessis, Citation2014; Hurt, Citation2007; Parsons et al., Citation2020), and there is room for improvement when the development of students’ pervasive skills is considered (Barac, Citation2009; De Villiers & Viviers, Citation2018; Sahd & Rudman, Citation2020). The perception of employers is generally that graduates are technically well-prepared, but lack some of the pervasive skills that differentiate a professional from others (Barac, Citation2009). This has led to an increased focus on academia, as tertiary institutions are considered important instruments in ensuring, through the assessment process, that life-long learning takes place (Boud & Soler, Citation2016). Tertiary institutions need not only to equip students with a degree at the end of their academic programme but also cultivate and teach both technical and pervasive skills to equip them for the professional examinations and ultimately the workplace which they will enter.

One of the pervasive skills that are discussed most often as a key attribute for future accounting professionals, is the ability to think critically (Barac, Citation2009; Barac & Du Plessis, Citation2014; De Villiers & Viviers, Citation2018; Khumalo, Citation2019; Viviers, Citation2016; Wells et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2013). Critical thinking skills are necessary to propose and test hypotheses, draw conclusions and ultimately solve problems (Hansson, Citation2019). This skill is categorised as important or very important by the future employers of graduates (Barac, Citation2009; Viviers, Citation2016). IES 3, which deals with professional skills and general education, indicates a number of pervasive skills that exist. These include professional, non-technical, transferable, soft, core, underpinning, critical, enabling, fundamental or employability skills (IAESB, Citation2012). However, critical thinking skills have been identified as one of the most highly sought-after pervasive skills which accountants need to perform well in their jobs (Barac, Citation2009; Hurt, Citation2007; Smit & Steenkamp, Citation2015; Van Rooyen, Citation2016).

Yu et al. (Citation2013) found, that although critical thinking skills are sought after in the workplace, a perception gap exists between American graduates’ self-assessment and employers’ assessment of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. While graduates considered themselves to be very well prepared for both unstructured and structured problem-solving, employers only assessed them as being well prepared for these tasks (Yu et al., Citation2013). Similar results were noted by Viviers (Citation2016) who found that students perceived their level of exposure to developing critical thinking as moderate to high, while employers placed great emphasis on this skill by ranking it as the third most important of all-pervasive skills assessed. Due to the importance of critical thinking skills for employers, it is imperative to ensure that critical thinking skills are developed and assessed in a tertiary environment in order to train competent professionals who are able to make responsible and creative decisions (Musametov, Citation2021).

The PPR assessment used in this study closes the gap by seeking to cultivate and develop critical thinking skills that are required in the workplace at the tertiary level. At the tertiary institution level, this pervasive skill will not yet be fully developed, however, the introduction of an authentic case study assessment within an experiential learning framework may address the need to expose students to pervasive skills required by the accounting profession. We now consider how critical thinking is defined and what key attributes make up critical thinking as this will drive the learning and assessment approach adopted.

Critical thinking

The current study focuses on accounting students who need to be educated for the workplace and the importance of pervasive skills such as critical thinking being part of that education has been emphasised above. The ability to think critically is an important and critical skill for accountants and professionals in general (Hansson, Citation2019; Shaw et al., Citation2020). The significance of critical thinking skills has been noted for a number of reasons: Haber (Citation2020) states it to be an indispensable skill in becoming a specialist, Bandyopadhyaya and Szostek (Citation2019) consider it to be a foundation on which all decisions should rest, and Tiruneh et al. (Citation2017) note that it leads to an individual being a more active and informed citizen. Despite the importance of critical thinking generally being accepted, Shaw et al. (Citation2020) and Hansson (Citation2019) observe that critical thinking lacks a clear and concrete operational definition. This is because many definitions exist, and researchers define ‘critical thinking’ for the purposes of their specific study. The current study makes use of the competency framework adopted by SAICA as the current population for this study are students who will be taught and prepared to ultimately pass the SAICA qualifying exams to become accounting professionals. SAICA’s competency Examines and interprets information and ideas critically (critical thinking) is considered a key pervasive skill which includes the following subsections that trainees need to develop during their training. Before being signed off and completing their training contract, prospective CAs need to be considered competent in the following key attributes of critical thinking (SAICA, Citation2020):

Analyses information or ideas

Performs computations

Verifies and validates information

Evaluates information and ideas

Integrates ideas and information from various sources (integrated thinking)

Draws conclusions/forms opinions

The above components of critical thinking are in line with the literature reviewed (Bandyopadhyaya & Szostek, Citation2019; Cheng & Wan, Citation2017; Hansson, Citation2019; Hurt, Citation2007; Shaw et al., Citation2020; Soufi & See, Citation2019; Tiruneh et al., Citation2017). Critical thinkers have the ability to solve problems, and their skills to evaluate information and reach justified conclusions enable them to make better decisions. Shaw et al. (Citation2020) support this view and define critical thinkers as individuals who are able to comprehend and evaluate statements for use in the decision-making process. They therefore place emphasis on the fact that critical thinking skills are an integral part of making good decisions. Cheng and Wan (Citation2017) note the shared features between all definitions of critical thinking they reviewed to be an evaluation or judgment, and that critical thinkers use both skill and habit to form these evaluations. By saying that the critical thinking process includes both skill and habit, Cheng and Wan (Citation2017) assert that this can be taught and improved on, as habits are generally considered to be formed by repetition. Critical thinking has also been defined by Bandyopadhyaya and Szostek (Citation2019) as the ability to identify relevant facts, identify and analyse options related to the situation, and finally, reach an appropriate conclusion. Hurt (Citation2007) identifies the following components of critical thinking: differentiating between relevant and irrelevant facts in a specific context, analysing the quality of an argument, defending an argument against other arguments and expressing a clear and well-reasoned point of view. Hansson (Citation2019) asserts that individuals sometimes see critical thinking as a fault-finding mission, while the author argues that it should rather be described as a problem-solving activity where the individual needs to ascertain where the information he/she needs to solve the problem, can be found. Tiruneh et al. (Citation2017) suggest that critical thinking has been linked to general problem-solving, and Soufi and See (Citation2019) describe it as critical reasoning, or the ability to make arguments. In summary, all definitions describe a process of forming an informed opinion, mostly to solve a problem, after assessing various pieces of information analytically. In practice, professional accountants are often expected to choose the best course of action based on the given information. This job description stresses the necessity of critical thinking skills when professional accountants are considered, as they need to form an informed opinion after assessing various information sources. The focus of the current study is critical thinking, but the authors acknowledge that critical thinking skills may encompass problem-solving skills and abilities as well.

Despite the fact that critical thinking skills are essential in the professional working environment, Smit and Steenkamp (Citation2015) identify that some professional bodies noted from the outcome of their qualifying professional exams that candidates lacked critical thinking skills. After Part 1Footnote1 of the qualifying examinations in 2012, SAICA released commentary that stated that candidates were not able to argue logically, could not apply their knowledge to the given scenario, were not reaching conclusions as they could not commit to an answer, and arrived at conclusions without addressing all issues presented (Smit & Steenkamp, Citation2015). All the issues noted relate directly to candidates’ inability to think critically, as they cannot form arguments, cannot assess provided information and cannot draw on these to reach conclusions. The problem therefore exists that candidates coming directly from tertiary institutions do not have sufficient critical thinking abilities. This, in turn, raises the question as to how this ability can be taught or cultivated at the tertiary level before candidates write their professional examinations.

Cultivating critical thinking skills is a complex exercise. Hurt (Citation2007) notes that critical thinking skills should be developed with purpose over time. Hansson (Citation2019) argues that critical thinking skills are not just general, but rather domain-specific and can therefore not be taught or learnt in an abstract, specific, separate course. Despite this fact, he further notes that valid reasoning skills form a large part of the critical thinking process and that these are the same for a range of topics and disciplines. Tiruneh et al. (Citation2017) agree and suggest that an expectation exists that introducing critical thinking skills to specific subjects will enable the transfer thereof to real-life problems. It is important to note that critical thinking skills cannot be developed in a short time span, but a critical thinking mindset can be developed and enhanced through the use of the right teaching and assessment methods.

Critical thinking, for purposes of the current study, is defined as being able to solve problems through analysing and evaluating information, integrating information and forming a conclusion (SAICA, Citation2020). The current study focusses mainly on this pervasive skill and how learning and assessment can cultivate and develop this skill. We now consider how an experiential learning framework may create a platform to teach and assess these skills.

Experiential learning

From the literature reviewed so far in this study, we can note that teaching pervasive skills, such as critical thinking, is lacking at tertiary institution levels (Barac, Citation2009). Using an experiential learning framework creates a platform to introduce teaching and assessment methods that can develop pervasive skills such as critical thinking. A common perspective on experiential learning theory (ELT) is that learning takes place while engaging directly in life experiences. These experiences enable students to process information, make connections, increase knowledge and develop skills (AEE, Citation2022; Kolb & Kolb, Citation2017; López-Hernández et al., Citation2022). Spanjaard et al. (Citation2018) found that integrating experiential learning activities into the curriculum expanded on students’ real-world experiences which ultimately ensured that graduates were more career-ready. The efficacy of using experiences as opposed to classroom learning to improve knowledge and skills has led to many undergraduate education programmes (Mentkowski et al., Citation2000) and professional programmes adopting experiential learning methods to teach pervasive skills (Kolb & Kolb, Citation2017). As mentioned previously, tertiary education institutions aim to develop both technical and pervasive skills. Of these, technical skills can easily be taught via a lecture and classroom learning approach, but for students’ exposure to and learning of pervasive skills, the introduction of other teaching methods is required (Hellier, Citation2013). Experiential learning methods provide an appropriate alternative approach in accounting and business courses specifically (Perusso et al., Citation2020; Van Akkeren & Tarr, Citation2022). A reason for the popularity of experiential learning methods in the business education space is the fact that they account for the complexity of real-world management practice in ways that traditional teaching methods cannot (Perusso et al., Citation2020; Van Akkeren & Tarr, Citation2022). Burch et al. (Citation2019) found that learning was enhanced when experiential methods were applied by allowing the student to actively participate in the experience when compared to control groups who did not partake in any experiential learning opportunities. Perusso et al. (Citation2020) noted that learning is positively impacted by experiential learning methods, while López-Hernández et al. (Citation2022) found that experiential learning significantly increases the future learning motivation of an individual. This might be because students have to develop their own associations between prior knowledge and new information and these new associations effectively change the way the student processes data, creates information and thinks going forward (Burch et al., Citation2019).

Van Akkeren and Tarr (Citation2022) and Alshurafat et al. (Citation2020) found that students developed critical thinking skills and ways to use these skills to solve practical problems that they will face in the workplace by way of experiential learning. Similarly, for Foo and Foo (Citation2022) the value of experiential learning methods lies in the demonstration and improvement of higher-order thinking skills, such as the development, construction and planning of solutions to problems. In addition to having superior learning outcomes and applying new thinking methods, students subjected to experiential learning methods have therefore also shown an improvement in critical thinking and related problem-solving skills (Alshurafat et al., Citation2020; Foo & Foo, Citation2022; George et al., Citation2015; Van Akkeren & Tarr, Citation2022). Despite the fact that Burch et al. (Citation2019) failed to identify a single context in the empirical studies examined where experiential learning was not effective, further development and enhancement of pervasive skills, such as critical thinking skills, can only be achieved if experiential learning methods move from a teacher-only orientated approach to a student-centred approach (De Villiers & Viviers, Citation2018). This is emphasised by Foo and Foo (Citation2022) who note that students working together collaboratively under experiential learning circumstances increase the standard of learning and the level of knowledge. They further note that experiential learning undeniably creates a platform for collaborative learning and an opportunity to improve on higher order thinking skills, such as critical thinking.

A demand therefore exists for tertiary institutions to provide learning opportunities and make use of appropriate assessment methods in which these pervasive skills can be developed and assessed appropriately (Shaftel & Shaftel, Citation2007). From the research reviewed above, the current study makes use of experiential learning theory as a framework to develop an authentic assessment that is student-centred, is based on real-world problems, includes collaboration, and aims to provide a platform to develop pervasive skills such as critical thinking. Next, we consider the types of authentic assessments that will meet this requirement.

Authentic assessment

Literature suggests that the type of assessment presented to students drives learning to a great extent (Hargreaves, Citation2007; Parsons et al., Citation2020; Van Rooyen, Citation2016). Boud and Falchikov (Citation2006) consider tertiary institutions to be instrumental in aligning assessment with skills required to learn in the long-term and not just immediate learning requirements. Authentic assessment specifically is described as an assessment format developed specifically to prepare students to perform the meaningful tasks that will be required of them in their future careers (Mueller, Citation2005). The current study focuses on one key pervasive skill that is required from future professional accountants, namely critical thinking. The study conducted by Bandyopadhyaya and Szostek (Citation2019) mentions that uncertainty exists regarding the assessment methods of critical thinking as a skill. The aforementioned study proposed that the assessment of critical thinking skills may include numerous assessment methods, such as case studies, projects, discussions, simulations and that it should focus on real-life problem-solving. Tiruneh et al. (Citation2017) argue that a comprehensive assessment of critical thinking skills should include testing of both domain-specific and domain-general dimensions and that the need for reliable tests will increase due to the necessity of critical thinking skills in the working environment. Normal assessment methods do not drive critical thinking and therefore do not develop the insight and depth needed by the students to function in a professional environment and pass professional qualifying examinations (Barac, Citation2009; Viviers, Citation2016). This is due to the technical nature of these assessments which do not always provide room for the assessment of pervasive skills which are important skills for the workplace. It is therefore clear that critical thinking skills might need to be assessed through measures that are not generally considered to be accepted practice or with assessments that are not yet implemented, and that an authentic assessment to assess these skills, needs to be created.

Although there are a few assessment methods that have been argued to be best suited for the assessment of critical thinking skills, strong arguments have been made towards the adoption of case study assessments which will better assist in bridging the gap between theory and real-life environments (Beattie et al., Citation2012; Culpin & Scott, Citation2012). This view is supported by a few professional bodies such as the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand (ICANZ) and the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) as well. These professional bodies have over the past few decades incorporated case study assessments into their professional examinations to place greater emphasis on pervasive skills and not only technical knowledge in order to equip future professionals with the necessary skills needed to be able to adapt to the continuous changes in business environments (Barac, Citation2009; Boritz & Carnaghan, Citation2003; Viviers, Citation2016; Wells et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2013). Older research studies which made use of case studies in assessing critical thinking were Sawyer et al. (Citation2000), Weil et al. (Citation2001) and Weil et al. (Citation2004). More recent studies supporting the use of case study methods to assess pervasive skills were Dean (Citation2015). The study by Dean (Citation2015) conducted on a group of students performing an academic writing task, revealed that collaborative learning had a positive impact on the quality of critical thinking demonstrated in the academic writing assessment. In this particular study, the ability to collaborate led to students being more prepared which enabled students in the mid-academic range to be able to generate and apply more ideas in the individual assessment. These results are further supported by Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) and Parsons et al. (Citation2020). Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) asserted that case study-based assessment is an effective manner to develop and assess professional skills. They found that accounting trainees considered the integration and adaptation of knowledge to specific scenarios to be one of the most important benefits of assessment through case study. This speaks directly to the skill of critical thinking. Parsons et al. (Citation2020) performed work regarding the development of the professional programme that has to be completed before professional qualifying exams can be written by future professional accountants accredited by SAICA. Candidates continuously ranked a case study assessment in the top third of most helpful learning tools in preparing for the professional exam (Parsons et al., Citation2020).

The use of experiential learning by an authentic assessment, such as a case study, already started in the early 2000s (Sawyer et al., Citation2000). With the aim to create an assessment that is more appropriate for the development of a critical thinking mindset, the current study explored creating an authentic assessment which has not yet been developed and practised in the existing academic programme at the university on a third-year level. The current study chose to adopt a similar approach to the aforementioned research studies where a case study assessment method was chosen as an authentic assessment tool to better assess pervasive skills. The PPR assessment used in the current study expands on this literature by also including a collaborative learning element to further enhance the development of a critical-thinking mindset. The use of collaborative learning as an element to further develop critical thinking is supported under the experiential learning framework (Foo & Foo, Citation2022) and is further discussed below.

Collaborative learning and assessment

The current study incorporates collaborative learning as a key element that can assist in developing a critical-thinking mindset. Research has shown that experiential learning creates a good platform for collaborative learning in which higher-order thinking skills such as critical thinking can be developed (Foo & Foo, Citation2022). A study by Christensen et al. (Citation2019) conducted on a group of accounting students, provided results of enhanced student engagement and learning of non-technical skills when students were exposed to a group learning environment. In their study students perceived to have improved their problem-solving skills based on the group learning environment. Khumalo (Citation2019) found that group projects offered a tool for developing critical thinking, whereas Haber (Citation2020) noted that group-thinking is advantageous when compared to individual thinking. In addition to the previously mentioned results, Barac (Citation2009) also found that employers found working as part of a team to be an extremely important skill that trainee accountants should possess when they graduate from university. Furthermore, learning as part of a group has also been shown to be an effective way to enhance critical thinking skills (Haber, Citation2020; Hargreaves, Citation2007). Retnowati et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study to establish the effect of collaborative learning in groups where not all students had the same level of knowledge regarding the topic studied and found that collaboration is helpful when learners must solve problems. They further mention that individuals learn more and better from people they know and trust, as a person first has to consider and accept the other’s expertise on the topic (Retnowati et al., Citation2018). Boud and Falchikov (Citation2006) argue that learning and understanding are always socially constructed and normally take place in social settings – families, communities, and colleagues – by working cooperatively with others you know. They are therefore of the opinion that you are only learning when you are working together to solve problems in groups and that teachers should better prepare students for this type of learning, i.e. collaborative learning, that they will be doing for the remainder of their lives (Boud & Falchikov, Citation2006). Hargreaves (Citation2007) agrees and notes that valuable learning may be associated with socially constructed knowledge through a collaborative learning process. The author argues that the group, as a whole, is the agent of inquiry and not the individual. As such, students take individual responsibility for creating the understanding necessary for the task and for ensuring that the other members of the group know this as well (Hargreaves, Citation2007). The above literature further supported the following studies’ results confirming the use of collaborative learning and case study-based learning as key tools to develop competencies such as pervasive skills: Weil et al. (Citation2001), Bonner (Citation1999), Ravenscroft et al. (Citation1999), Weil et al. (Citation1999), Caldwell et al. (Citation1996), Hite (Citation1996), Saudagaran (Citation1996), Knechel (Citation1992) and Campbell and Lewis (Citation1991).

Despite collaborative learning being researched extensively, research on the assessment of collaborative learning is scarce (Meijer et al., Citation2020). Schmulian and Coetzee (Citation2019) engaged in research focusing on accounting students’ experience of a collaborative assessment. In their experiment, students were grouped in predetermined groups when they arrived at the test venue. They then wrote the assessment in a team environment – multiple choice questions were provided and the whole group had to come to a decision before they selected the answer as a group. The participants received immediate feedback on their selected answers. Students were found to construct new knowledge by collaborating with team members. They learnt by explaining concepts to others and also by being guided by their group members, let to the creation of new knowledge. They had to understand the relevant content to be able to defend their professional opinion to their peers before an answer was selected and that improved their group work skills and their knowledge of the topic. In this study, 75% of the participants experienced the assessment as positive or extremely positive. The researchers primarily attribute the remainder’s experience to the differing academic abilities of the group that led to unresolved conflict. Shawver (Citation2020) implemented a similar study however they divided their accounting class into two groups, one group situated in a collaborative learning class format and the other exposed to a traditional class format. After a few classes, students had to complete class quizzes as well as examinations individually. Students who were part of the collaborative learning class format showcased better performance in the class quizzes compared to another group of students who only got a traditional lecture format. This however was not the case for the examinations. These results supported the studies of both Opdecam et al. (Citation2014) and Jang et al. (Citation2017) which showcased an improvement in academic performance due to students’ better understanding which stemmed from conversations and peer collaboration. These results showcased some possible benefits of the impact of collaborative learning on students’ academic performance.

Meijer et al. (Citation2020) state that individual assessment of collaborative learning might better reflect the student’s domain-specific abilities than group assessment. However, the individual’s performance will still be influenced by the collaborative setting as the group’s behaviour influenced the individual and due to the potential benefit noted from an exchange of knowledge in the collaborative space. The current study’s assessment format assesses each student individually, even though they worked in groups beforehand. The assessment therefore does not constitute a group assessment, but rather an individual assessment of collaborative learning (Meijer et al., Citation2020). The PPR assessment format incorporates a collaborative learning aspect through the use of an authentic assessment, in this case, a case study with a partial pre-release of information, to cultivate critical thinking skills in students when they attempt the individual assessment. The final section of the background introduces the PPR assessment format used in the current study.

Partial pre-release assessment

The assessment format that the current study adopts is that of the APC, SAICA’s second qualifying exam, which was changed from a technical-based assessment to a competency-based assessment in 2014. The reason SAICA moved away from a technical-based assessment was to ensure the CA(SA) qualification remains relevant, is abreast of international trends and meets evolving business needs (SAICA, Citation2020). To be able to address the previously mentioned areas, SAICA introduced an assessment evaluating principles with the emphasis on evaluating the overall competence of a candidate with a focus on pervasive skills which include critical thinking. Pervasive skills should be developed at an academic institution level, although SAICA acknowledges that professional and training programmes, after the completion of a candidate’s degree, contribute much more to developing these skills (Olivier, Citation2015).

The APC assessment is presented in a case study format that is released five days prior to the examination. Candidates then have the opportunity to collaborate in groups before receiving additional information on the day of the exam which alters the original information provided. This forces candidates to critically evaluate the new information provided, before giving their professional opinion in written form. In a profession where critical thinking skills are not only required but rewarded, and group work is something that graduates are confronted with daily, it makes sense that the professional body assesses candidates greatly on these skills. Boud and Falchikov (Citation2006) write that assessment has two main purposes: providing certification of achievement and facilitating learning. The APC falls in the first category – candidates need to pass to ultimately register as a CA(SA). University education must meet both – students are awarded with a degree at the end of the programme, but they must also be equipped with the technical and pervasive skills required by the profession. Therefore, their technical and pervasive skills need to be assessed and this must happen before their second professional examination for candidates to gain the necessary exposure to the format and skill development.

In the current study, the population used are third-year undergraduate students who have not yet been exposed to a case study format assessment. As noted in the literature, students cannot yet be expected to have pervasive skills, but academic programmes should start to cultivate pervasive skills such as critical thinking and should also prepare their students for professional examinations. Therefore, to assist in cultivating critical thinking skills, the need was to get students, through collaboration with their peers, to better understand and prepare for the case study assessment. The improved understanding and preparedness would in return help students on the final assessment day to fulfil some of the key attributes of critical thinking i.e. more easily analyse and evaluate information or ideas, be able to integrate ideas and information from the case study to the new information on the day, have a basis from which solutions can be developed and conclusions can be made. This expectation is supported by studies that found that being better prepared and having an improved understanding can cultivate critical thinking in assessments (Altintas et al., Citation2014; Cadiz Dyball et al., Citation2010; Dean, Citation2015; Frame et al., Citation2015; Parsons et al., Citation2020; Sahd & Rudman, Citation2020). Students cannot be expected to learn critical thinking skills in a short period (pre-release period), however by having the case study before the final assessment we can start to cultivate a critical thinking mindset where students need to be able to better prepare themselves, do additional research to understand the case study and thereafter apply themselves on the critical thinking attributes set out above on the final day of the assessment.

Summary

The background discussed the skills needed by accounting graduates entering the workplace and further defined critical thinking as a skill for the purposes of this study. It further elaborated on the role that collaborative learning and authentic assessment methods play, within a experiential learning framework, to develop pervasive skills. It was determined that critical thinking is a crucial skill for CAs in practice and that this skill is cultivated and developed through collaborative learning. Given that assessment plays an important role in driving students learning, the PPR assessment format meets the requirement of a revised twenty-first-century assessment approach that can develop critical thinking mindsets within tertiary students.

Hypotheses development

Students do not yet understand or know how to determine if they have developed critical thinking skills, however the tasks needed to be performed, on the final day assessment used in the current study, aligned to that required of someone with a more critical thinking mindset i.e. being able to use information from the case study and apply it to new information provided on the day of the assessment. Studies such as Altintas et al. (Citation2014), Frame et al. (Citation2015) and Hargreaves (Citation2007) support the aforementioned statement made as their studies report results that a collaborative learning environment, in instances where groups work on an application exercise similar to that of the PPR assessment, will require students to use critical thinking to apply the information they learnt from collaboration with peers to a complex problem or case study.

Therefore, the objectives and hypotheses of the current study were developed to investigate the association that collaboration had with: ‘the level of preparedness’ and ‘the level of depth’ of having the case study available in the pre-release period and then ‘the expected test result’ seeing that students could better apply the critical thinking attributes on the day of the assessment. The support for these hypotheses is outlined below:

Level of preparedness

The value of group collaboration and its impact on student preparedness have been highlighted in a few studies. In the research study conducted by Dean (Citation2015) on an academic writing class, the level of preparedness among students who collaborated before the individual assignment showcased increased application of critical thinking not necessarily in their writing expression but more in regard to the ideas they could generate to address the assignment. These results were supported by both Frame et al. (Citation2015) and Parsons et al. (Citation2020). In the study conducted by Frame et al. (Citation2015), students specifically reflected that collaborating with peers assisted them in being more prepared for examinations compared to attending traditional lectures. In the study conducted by Parsons et al. (Citation2020), accounting candidates completing a professional course in their study perceived the group work element of the case study as being valuable in preparing for the case study assessment. Based on the above this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: There is no perceived association, observed by participating students, between collaboration during the ‘pre-release’ phase and level of preparedness for the PPR assessment.

Level of depth

Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) conducted a study in which they required feedback from accounting candidates who completed a case study assessment, similar to this study’s PPR assessment. Perceptions from their candidates ranked integrating information to adapt to a scenario, applying technical knowledge to practical problems and identify, analyse and solve problems in an unstructured format, thereby requiring a person to break down the problem into its underlying parts amongst the top ten benefits. These align with the definition of critical thinking outlined by SAICA’s competency framework (SAICA, Citation2020). All these aspects helped the candidates address the assessment in more depth. More studies have supported the results that collaboration in a case study assessment provided more depth for students. Examples include the study from Altintas et al. (Citation2014) reporting an increase in students’ content knowledge and understanding, and mastery of basic conceptual material, coming from group collaboration which enables them to develop their problem-solving skills. Deeper learning was experienced in a group of management accountants when they were required to engage in a case study assessment in groups (Cadiz Dyball et al., Citation2010). In the aforementioned study, students perceived the group collaboration to enable them to generate and develop more in-depth ideas such as deep insight into the context of the case study. From the above studies, it can be noted that collaborative learning in a case study assessment does provide more depth for students which can develop the necessary critical thinking mindset to answer the required tasks. Based on the above this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: There is no perceived association, observed by participating students, between collaboration during the ‘pre-release’ phase and level of ‘depth’ (understanding) for the PPR assessment.

Expected test result

In the research study of Opdecam et al. (Citation2014), learning through collaboration had a positive effect on students’ academic performance compared to lecture-based learning. The study by Shawver (Citation2020) also found that students who collaborated before doing accounting quizzes, showcased better academic performance compared to students who chose lecture-based learning. Although the impact on expected results does not link to the cultivation of critical thinking, the current study determined whether students perceived the collaboration to have had a positive impact on their academic performance. For this study, the actual performance of students was not tracked but rather the perception from students was gained to see if they perceived an increase in their academic performance from having collaborated with peers before the assessment. Based on the above this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: There is no perceived association, observed by participating students, between collaboration during the ‘pre-release’ phase and expected test result for the PPR assessment.

Research method

The research method section outlines the PPR assessment format used in the case study adopted in the current study, the study participants, the procedures, measures and finally the analysis that is performed.

PPR assessment format

The assessment in the current study took a format very similar to that of the APC examination administered by SAICA. The format adopted a case study and real-life problem-solving tasks presented to students on the day of the assessment (Bandyopadhyaya & Szostek, Citation2019). The tasks incorporated analyses of information, performing of computations, verifying and validating information against the PPR information, evaluating information, and integrating thinking on which students had to draw conclusions on. All these tasks are considered competencies future CA(SA)’s should have and are the key attributes of critical thinking (SAICA, Citation2020). For the current study, the case study presented to students in both years of assessment was that of an unknown, fictitious company, which provided more encouragement for students to collaborate as the company could not easily be researched. More emphasis was placed on professional competence in a collaborate environment by considering: ‘what would a task look like in practice/industry?’.

The assessment mirrors how a financial analyst in practice would typically get and address a task. For example, a financial analyst would be given a deliverable which may be due in a couple of days. During this time, the financial analyst would be able to collaborate with peers and conduct research enabling them to reach a final recommendation to said deliverable. On the deliverable due date, additional information may arise, presenting the analyst with new information which must be used in conjunction with the information provided previously to present a new consolidated recommendation/solution (all within the original time frame).

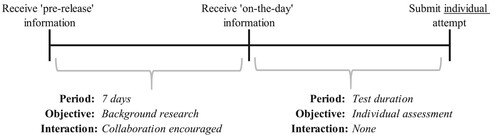

With this in mind, the revised assessment format simulates, as far as possible, a real-life scenario as it would take place in practice. The PPR assessment format consisted of two distinct phases ():

‘Pre-released’ information in the form of a case study was given to students seven days before the sitting of the final assessment. During this time students were given the opportunity to conduct any research they deemed necessary and were afforded the opportunity to collaborate with their peers.

On the formal assessment date, supplementary information to the original case study was provided (along with the required tasks). The supplementary information assessed the student’s problem-solving ability by taking previously communicated information and adapting it with new information provided ‘on the day’. Accordingly, the supplementary information simulated a practical real-life setting whereby financial analysts are constantly challenged with new information and questions from management.

This study was conducted over two academic years, specifically 2018 and 2019, thus covering two different student groups. Students from these academic groups had four Continuous Evaluation Assessments (‘CEV’) a year and the PPR assessment was introduced only in one of these CEVs. The remaining three CEVs written were all normal assessments in that they assessed technical competence with all information only being presented on the day of the assessment. For the 2018 academic group, the PPR assessment was the second CEV of the year, whereas for the 2019 academic group, the PPR assessment was the third CEV of the year.

Due to the PPR assessment format being an assessment format that students would not have been exposed to before, detail tutorials were held with students on how to approach studying for this format. During these tutorials students were informed on what is meant with ‘collaborating with peers’ and the expectation was set that the PPR assessment would challenge them on the key attributes of critical thinking as set out by the SAICA competency framework (SAICA, Citation2020).

Participants

The students used for the population of this study are final year BCom Accounting Sciences students who are studying towards becoming professional accountants. The BCom Accounting Sciences programme is a three-year programme and the PPR assessment is only assessed in student’s final year. Not all these students are expected to write professional examinations due to the strict entrance requirements to get into the post graduate course. Only a limited number of students will pass the post graduate course after which they need to write professional examinations to qualify as a professional accountant.

A total of 482 and 447 final-year BCom Accounting Sciences students wrote the revised assessment format in 2018 and 2019, respectively. From the students who wrote the assessment, 87% (2018) and 96% (2019) of students took part in the post-assessment survey. Of the 447 students who wrote in the 2019 academic year, 86 students were repeating students who would already have been exposed to this assessment format in the prior year. The PPR assessment was only introduced in 2018 and therefore repeating students in this academic group would not have had any benefit of this new assessment format compared to other students.

Two academic groups were examined to firstly analyse statistical data across two different years to explore trends over time and compare the results between two periods. Secondly, examining two groups also enabled us to assess the consistency and variability of certain aspects of the study across the two years.

Procedures

A survey, using both closed- and open-ended questions, was adopted to collect data pertaining to students’ perceptions of the PPR assessment format. This study was conducted over two academic years, covering two different student groups. The survey was administered using an online platform, named Qualtrics, where a survey link was distributed to students. Students could participate in the survey anonymously and voluntarily.

Measures

The purpose of the survey was to examine the experience of the students of the new PPR assessment format and comprised of 9 questions. The questionnaire data was generated using Likert scale response (1 – Strongly Agree to 5 – Strongly Disagree), performance measurement responses (1 – Better, 2 – The same, 3 – Worse) and yes/maybe/no responses (1 – Yes, 2 – Maybe, 3 – No). Additionally, an open-ended question was included in the questionnaire to assess whether students experienced this new format of assessment as beneficial to their studies.

The survey questions distributed to the students can be viewed in .

Table 1. Survey questions.

The survey was prepared by the authors and peer-reviewed by departmental colleagues to ensure that the design was appropriate with all questions being unambiguous. No significant amendments were made, other than the inclusion of the open-ended questions, to assess students experience.

Analysis

For the quantitative results, the SPSS Statistical package was used to analyse the quantitative data gathered through the Qualtrics survey. Descriptive statistics in the form of mean, median, standard deviation, and percentage of responses were performed on each question (1 to 9) for the 2018, 2019 cohort and the combined cohort. The frequencies of the responses were checked for data integrity prior to the data being used in any form of statistical analysis.

As outlined in hypotheses H1 to H3, a key component of this study is to determine whether there are statistically significant differences in student perceptions relating to critical thinking between those students who collaborated versus those who did not (as denoted in question 3 of the survey). To highlight the interaction(s) between the variables, prior to determining the existence of any statistically significant relationship (if any), multivariate tables were constructed. Once constructed, for the purposes of bivariate analysis and to be able to either accept or reject the hypotheses H1 to H3, the association between two categorical variables was evaluated using the Pearson Chi-squared test. Correlations with a 2-sided Asymptomatic Significance (p-value) of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. For H1 question 4 measures ‘the level of preparedness’, for H2 question 6 measures ‘the level of depth’ and for H3 question 8 measures the ‘the expected test result’

A quantitative content analysis was performed on the data collected by the Qualtrics survey using a thematic approach. This approach was adopted to gather more detail and data to address the hypotheses of the study. The content analysis supported the quantitative analysis to enrich the conclusions about the students’ perceptions of the PPR assessment format. For the thematic approach every response was coded and subsequently scrutinised for both accuracy and completeness of the dataset. The coding, which is based on the primary underlying characteristics of each comment, grouped similar comments into prevailing positive and negative themes for detailed analysis.

The negative themes included: ‘stressful’, ‘too much information’ and ‘other’; whilst the positive themes included: ‘collaboration’, ‘preparation for future assessments’, ‘improved understanding’, ‘less stress’, ‘new experience’, ‘practical experience’, ‘preparation’, ‘think differently’, ‘triggers’, ‘no comment’ and ‘other’.

After the initial coding, the analysis included the comparison of these constructed groups with survey question 3 (collaboration) for further insight into the primary research question outlined above.

Results and analyses

Quantitative analysis

The descriptive statistical results are presented in , followed by the bivariate results presented in . The results of the questionnaire, for each of the survey questions 1 to 9, are presented in . In the first question, aimed at establishing whether the PPR information guided students appropriately as to the content being covered in the assessment, an overwhelming 91% of students either strongly or somewhat agreed in 2018. This decreased slightly in 2019 where only 72% of students strongly or somewhat agreed but the consensus remained. A similar trend presented itself for question 2, aimed at establishing whether students experienced the PPR as being helpful in gaining a better understanding of the industry. For question 2, 90% (2018) and 77% (2019) of students either strongly or somewhat agreed with the premise.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Table 3. The pre-release information enabled me to better prepare for the assessment.

Table 4. Pre-release research related to the case allowed me to approach the answering of the assessment with more depth.

Table 5. I expect my results for assessment to be better, the same, or worse having had the pre-release information.

The results further indicated that, as evidenced by 85% of the 2018 cohorts and 57% of the 2019 cohorts’ question 4 responses, there was a perceived improved level of examination preparedness when using the PPR format. Despite the noticeable decrease from 2018 to 2019, there was still an overwhelming agreement in both years (94%) that students made use of their pre-release research when answering the ‘on-the-day’ tasks (Q5). From the responses to question 6, aimed at establishing whether the PPR helped them (the students) to answer the assessment with more depth, 75% (2018) and 62% (2019) of students either strongly agreed or somewhat agreed.

It is noteworthy, however, that even though there was an overall positive skewedness in the level of guidance on test scope (question 1), understanding the industry (Q2), level of preparedness (Q5) and more depth when answering (Q6), this only led to 64% (2018) and 31% (2019) of students believing this would increase their test marks (Q8).

Lastly, the students’ overall experience differed year on year with 60% of the 2018 student cohort being open to having this assessment in future in contrast to only 36% of the 2019 student cohort. This trend, a decreased percentage in 2019 when compared to 2018, was present for each question (1 to 9). One plausible answer for this decreasing trend was due to the different test scopes for the respective assessments. In 2018 the scope included topics students were more comfortable with and topics in which students usually do better, whereas in 2018 a different set of topics were tested which included topics students do not perform as well in. It can be assumed that students did adapt their perception of the assessment based on their own feelings towards the type of topics being tested. The results were further unpacked in the discussion section which follows.

The student experiences, linked to cultivating a critical thinking mindset, which are specifically analysed as part of this study is whether the collaboration during the pre-release period (Q3) was perceived by the students to:

help them ‘better prepare’ for the assessment (H1),

assist them in ‘answering the assessment in more depth’ (H2); and

result in a ‘better’ expected test result (H3).

The results of each of the three hypotheses are reported below.

Evaluating the association between collaboration and students’ level of preparedness

reports the quantitative results for whether students perceived the pre-release information and collaboration to have better prepared them for the assessment.

From the descriptive results in , the authors note that 84% (2018) and 78% (2019) of students collaborated with peers before the assessment took place. Of the students that collaborated, 86% and 55% experienced themselves to be better prepared for the assessments as a result of having PPR information for the 2018 and 2019 academic years, respectively. Similar trends were, however, also observed for those students that did not collaborate with peers as we note that 75% (2018) and 59% (2019) of these students also felt better prepared.

Despite these perceived similarities on the descriptive statistics, a statistically significant difference was identified between collaboration and level of preparedness in the 2018 academic year (p = 0.023). This leads to the rejection of H1 for 2018 (only), translating into an association between the collaboration of students and the level of preparedness for the assessment for this period. Stated simply, the significance of this result is that it implies that peer-to-peer collaboration, or learning as part of a group, prior to an assessment can improve the overall level preparedness which can be attributable to better critical thinking skills as noted in literature (Haber, Citation2020; Hargreaves, Citation2007). These results supported the study conducted by Dean (Citation2015) who noted an increase in level of preparedness improved students’ critical thinking application in the outcome of an academic writing assessment task. Studies such as Frame et al. (Citation2015) and Parsons et al. (Citation2020) also supported that group collaboration for class quizzes and case study assignments improved students’ level of preparedness respectively.

A plausible explanation that H1 was not rejected for 2019 can, yet again, be associated with the different type of topics assessed across the different year groups. In 2019 cost management topics were assessed, which students may perceive as more ‘matter of fact’ translating to a greater innate belief of not being able to prepare or collaborate on due to its nature. Comparatively, in 2018 financial management topics were assessed which may have prompted a more collaborative approach.

Evaluating the association between collaboration and answering in more depth

reports the quantitative results for whether students perceived the pre-release information and collaboration to have allowed them to answer the PPR assessment in more depth.

From the descriptive results in , we note that 90% (2018) and 77% (2019) of students perceived the PPR information to be helpful in gaining a better understanding of the industry and overview of the case study. This supports the results of both Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) and Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020). In the study of Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) students felt that they were able to generate and develop more in-depth ideas through collaboration with peers which enabled a deeper understanding of the case study, whereas for Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) students were better able to apply their technical knowledge to practical problems as they understood the scenario better. This could be translated into being able to approach the assessment with a greater depth of knowledge and having a better understanding. From the results presented in , 79% (2018) and 64% (2019) of students who collaborated strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that the PPR information provided them with more depth in the assessment. In contrast, when considering those who did not collaborate, only 54% (2018) and 58% (2019) of these students felt they had more depth due to having the PPR information.

These results translated into a statistically significant difference between students who collaborated and the level of depth for both the 2018 (p = 0.000), 2019 (p = 0.005) assessments and from a combined perspective (p = 0.005). Therefore, H2 is rejected across all levels of analysis and an association is proven to exist between student collaboration and level of ‘depth’ (understanding). The rejection of H2 indicates that because of being able to collaborate with other learners, students felt that they had more depth and insight in when providing responses to the ‘on the day’ tasks. Considering that the same was not seen for those ‘non-collaborators’, one needs to consider whether this could provide substantiation for:

The development of students’ problem-solving ability through collaborative learning (as outlined by Retnowati et al. (Citation2018)). In the aforementioned study, collaboration in groups led to students increasing their knowledge, especially for students who did not have the same level of knowledge as other students in their groups which led to learners showcasing better problem-solving skills.

Collaborative learning provides students with ‘making meaning’ of information instead of just ‘acquiring information’ which leads to students reflecting and thinking more critically (Hargreaves, Citation2007; Parsons et al., Citation2020; Van Rooyen, Citation2016). However, in the current study, only the perception is obtained from students and therefore one cannot determine with accuracy if students’ actual critical thinking skills improved.

Evaluating the association between collaboration and better-expected results

reveals the quantitative results for whether students perceived the pre-release information and collaboration to have led to better results in the PPR assessment.

From the descriptive results in , we note that 64% (2018) and 31% (2019) of students expected their results to be better because of the PPR assessment format. Similar splits, as shown in , were seen for both the collaborative and non-collaborative groupings of students across both the 2018 and 2019 academic years. These results translated into the authors being unable to, on a statistically significant basis, reject H3 (relationship between collaboration and results expectation). These results are similar to that of Shawver (Citation2020) who found that accounting students’ performance did not improve in a collaborative learning environment in an exam assessment. However, this same study did find that students experienced an increase in academic performance for smaller class assessments such as quizzes.

Quantitative content analysis

As part of the post-assessment questionnaire students were asked to comment on whether this type of assessment was beneficial. Comments were categorised between students who wrote in the 2018 or 2019 years of assessments, whether the experience perceived by the student was positive or negative and lastly whether students chose to collaborate or not.

From the 846 students who completed the post-assessment questionnaire only 736 (87%) provided either an indication of whether their experience was positive or negative and a written response to this question. From the 736 responses, 79 (11%) responses did not provide a written response and only indicated a negative or positive experience (‘No comment’ as per ).

Table 6. The format of the assessment was beneficial to my studies by: (written response).

The themes identified amongst the responses, and their respective tallies, are .

The analysis provided insight into how the students perceived and experienced the PPR assessment format. Overall, across both years of assessment, the majority of the feedback received from students was positive (87%) with only 13% of the total cohort disclosing negative sentiments towards the revised format. What was notable was that the majority of both groups of students, collaborators and non-collaborators, found the PPR format as a positive experience. This supports the results of Doran et al. (Citation2011) who in their study implemented a case-study teaching approach where the majority of students noted a positive experience. The following studies also reported similar positive experiences from students using collaborative learning with a case study: Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) and Parsons et al. (Citation2020). The negative experience was more prominent in 2019 where 71 students (22% of the 2019 cohort) experienced the PPR format as negative compared to 2018 where 26 students (8% of the 2018 cohort) had a similar experience. This big divide in experience supports the response in where the majority of students in 2018 (60%) were open to having this assessment format again in future compared to only 36% of students in 2019.

From the 637 students who perceived this assessment as positive, the three most common themes were: the value students found in using the PPR information to identify triggers (26%) in the pre-release information, to better prepare (23%) them for the assessment and gaining a better understanding of the scenario (22%).

These three themes specifically related to having more time to work through large amounts of information beforehand, compared to a traditional assessment. Interestingly, the 2018 student cohort felt more strongly about the impact that the PPR had on the preparation when compared to the 2019 student cohort. This aligns with the descriptive stats shown in where it was highlighted that 85% of students in 2018 felt better prepared compared to only 57% in 2019. The opportunity to identify the relevant information to research (triggers) during the pre-release phase (ultimately providing students with a guide on what to focus their preparation on for the assessment), was greatly valued by students. The descriptive statistics further supported these comments as 91% (2018) and 72% (2019) of students felt the PPR guided them appropriately in relation to the content being covered. Finally, being able to research the industry of the company in the scenario and getting a better understanding of the business context prior to the assessment was well received by students. In , we note that 2018 (90%) and 2019 (78%) of students strongly or somewhat agreed with the PPR giving them a better understanding of the industry.

The positive comments relating to students feeling better prepared (Dean, Citation2015), having a better understanding of the business context and industry, as well as having more depth due to the PPR information supports the argument of Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) and Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) for the use of more case study assessments. The study by Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) found that students perceived to have gained a deeper insight into the industry of the case study and were able to develop more ideas having collaborated with peers. Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) further support these results where students in their study perceived case study assessments to help them work through large amounts of information to improve their understanding and application of information to the relevant problems faced in the final assessment. These assessments allow the students the opportunity to adapt and integrate their knowledge gained in the pre-released information which helps to build critical thinking skills (Parsons et al., Citation2020).

The remaining positive comments dealt with experience gained of how the future workplace environment works (13%), encouraging students to think differently (3%), helping students manage stress (3%), practical experience of real-life problems (2%), the assessment being a new positive experience (2%) and the importance of peer collaboration (1%). Many students acknowledged the value of the PPR format as it replicates their future workplace environment as well as their future professional qualifying exams. This was also evident in comments where students enjoyed having a practical experience of a real-world company and having to solve real-world problems (Sahd & Rudman, Citation2020). These results are similar to that of Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) as well. The aforementioned study introduced a case study for which students had to work in groups to answer certain tasks. The real-world scenario stood out as one of the best aspects of the case study assessment for students. Students also found the format to be challenging and they were forced to think differently by using more critical thinking and analysing skills when integrating the PPR information with the new information given on the day of the assessment. This supports the result of Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) where students identified that case study assessments helped them think more out of the box. These skills map into the competency framework of SAICA and outline some of the skills they expect future CA(SA)’s to have in the workplace (SAICA, Citation2020). Having a new experience brought on by the different assessment format also excited some students who liked being out of their comfort zone. These results are in contrast to Frame et al. (Citation2015) and Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020). The study by Frame et al. (Citation2015) noted in their study the resistance from students to adopt a team-based learning approach as it is different to their normal lecture-based learning. Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) further supported this as their students perceived a ‘new format of testing’ as a big constraint. Other students found comfort in having the PPR information before the assessment as it helped manage their stress and anxiety levels and gave them more confidence on the day of the assessment. This supported the results of Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) who found that students felt more relaxed in the test. The fact that students were able to collaborate, 84% in 2018 and 78% in 2019 as presented in , in the PPR period increased their understanding even more as peers could help each other. This is in line with the findings of Schmulian and Coetzee (Citation2019) where their qualitative feedback from students also expressed the benefit of leveraging of peer knowledge in their group assignment task. The results further supported the findings of Christensen et al. (Citation2019) who noted that students perceived themselves to have improved on their problem-solving ability due to collaborative learning. The study by Parsons et al. (Citation2020) further supported these results as their study showcased feedback from candidates stating the valuable and positive experience they perceived from groupwork before a case study assessment.

Two negative themes of comments stood out for 13% (97) of the 736 written responses received in the post-assessment survey. Firstly, 29% of students who perceived the assessment as negative were overwhelmed with the amount of information received in the PPR information. This is similar to the results found by Cadiz Dyball et al. (Citation2010) and Sahd and Rudman (Citation2020) where the amount of information given in the case study included too many things to cover. Students in the current study struggled to work through the big amount of information and integrate it with the ‘on the day’ information. Secondly, 8% of students who perceived the assessment as negative found it stressful having all of this information beforehand not knowing what additional information would be given on the day of the assessment. This is in contrast to students who had the opposite experience i.e. valued the additional time to work through the big amount of information and found this format as relieving stress rather than creating additional stress. Other comments included students not enjoying thinking out of the box or being put outside their comfort zone. This indicates the diverse group of students we are dealing with in a professional accounting education programme and the different mindsets each of these students have and how it affects how they might deal with change.

The authors acknowledge that of the 97 negative comments received, 50% of those students did not provide written feedback therefore not explaining the reason why they perceived the assessment as negative.

Discussion