ABSTRACT

In recent years, the French state has increasingly promoted a model of counterterrorism in which the state outsources responsibility for counterterrorism duties to individual citizens. This model frames such duties as a civic responsibility to be performed by all. Working in conjunction with a vision of jihadi radicalisation borrowing from anthropologist Dounia Bouzar’s understanding of the phenomenon as a ‘dérive sectaire’, this discourse has individualised responsibility for counterterrorism on two levels. Firstly, guilt is individualised: France’s responsibility in creating its own so-called ‘home-grown’ jihadis is obscured, with radicalisation instead framed as entirely down to the cultish influence that malevolent recruiters exercise over vulnerable recruits. Secondly, responsibility for ‘deradicalisation’ is also individualised: citizens are held individually responsible for this work, with the state’s role reduced purely to its carceral functions. This article argues that two recent films depicting young women being ‘radicalised’, Ne m’abandonne pas (Durringer Citation2016) and Le Ciel attendra (Mention-Schaar 2016), reproduce this highly neoliberal vision of counterterrorism. This is particularly problematic given that both directors framed their films as didactic interventions educating viewers about the ‘realities’ of jihadi radicalisation: a framing widely accepted by reviewers and state representatives, including then Minister for National Education Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.

Résumé

Depuis quelques années, l’état français promeut un modèle d’antiterrorisme qui sous-traite la responsabilité des devoirs liés à la lutte contre le terrorisme aux citoyens. Ce modèle construit le travail antiterroriste comme responsabilité civique de chacun. Allant de pair avec une vision de la radicalisation djihadiste qui emprunte de la description du phénomène comme « dérive sectaire » de l’anthropologue Dounia Bouzar, ce discours sert, à deux niveaux, à individualiser la responsabilité pour l’antiterrorisme. D’abord, la culpabilité se trouve individualisée : la responsabilité de la France en créant ses propres djihadistes soi-disant « d’origine intérieure » est dissimulée, la radicalisation étant construite comme le seul fait de l’emprise sectaire qu’exerce des recruteurs entièrement malveillants sur leurs recrues vulnérables. Deuxièmement, la responsabilité pour la « déradicalisation » est également individualisée : les citoyens sont tenus pour responsables de ce travail, le rôle de l’état étant réduit exclusivement à ses fonctions carcérales. Cet article soutient que deux films récents qui mettent en scène la « radicalisation » de jeunes femmes, Ne m’abandonne pas (Durringer Citation2016) et Le Ciel attendra (Mention-Schaar Citation2016), reproduisent cette vision extrêmement néolibérale de l’antiterrorisme. Ceci est d’autant plus problématique que leurs directeurs ont tous les deux décrit leurs films comme interventions pédagogiques servant à sensibiliser leurs publics aux « réalités » de la radicalisation djihadiste : une description largement acceptée par les critiques et certains représentants de l’état, y compris Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, alors ministre de l’éducation nationale.

Introduction

In October 2019, jihadi Mickaël Harpon, an administrative police employee, murdered four officers in the Paris préfecture de police. Following reports that Harpon had previously shown ‘signes de radicalisation’, then Interior Minister Christophe Castaner urged suspicion of such ‘signaux d’alerte’, including ‘[le] port de la barbe, le fait de ne plus faire la bise … une pratique régulière et ostentatoire de la prière’. President Emmanuel Macron subsequently called on citizens to form ‘une société de vigilance’, reporting such signals of ‘un éloignement avec les lois et les valeurs de la République, une séparation’ wherever they occurred: ‘à l’école, au travail, dans les lieux de culte, près de chez soi’ (Hourdeaux Citation2019).Footnote1 These were not the first requests made by French state bodies that citizens become de facto counterterrorism agents. The online ‘Stop-Djihadisme’ campaign, launched after the 2015 Île-de-France attacks, claimed to give citizens the tools to detect signs of jihadi radicalisation.Footnote2 Like Castaner, the (no longer accessible) website criminalised practices associated with Islam and unrelated to jihadism by listing as potential warning signs the sudden adoption of markers like the headscarf or long beard, or observance of Islamic dietary restrictions (Hourdeaux Citation2019; Perrotin Citation2015).

This article discusses two films released, like Stop-Djihadisme, shortly after the attacks of 2015, which represent protagonists carrying out such civilian-led counterterrorism: Xavier Durringer’s téléfilm Ne m’abandonne pas (Citation2016) and Marie-Castille Mention-Schaar’s feature film Le Ciel attendra (Citation2016). Drawing on scholarship from critical terrorism studies, it argues that both reproduce a highly individualised worldview, rooted in neoliberal logics, which has underpinned recent French counterterrorism discourse, and particularly discourses around civilian-led terrorism. Within this framing, responsibility for jihadi radicalisation is attributed solely to malevolent recruiters accused of brainwashing vulnerable youths, obscuring France’s own role in creating ‘home-grown’ French jihadis. Responsibility for detecting jihadis is similarly individualised, being outsourced to private citizens in line with the demands of Castaner, Macron, or Stop-Djihadisme; in keeping with broader patterns within neoliberal governance, the state’s role becomes purely carceral.

Both films depict parents struggling to prevent their teenage daughters from leaving France to join the so-called Islamic State (IS). The parents of Ne m’abandonne pas’s Chama (Lina El Arabi) eventually persuade her to renounce her plans to join her jihadi husband Louis, now going by Abderrahmane, in Syria. Le Ciel attendra, meanwhile, depicts the contrasting journeys of two schoolgirls. The parents of Sonia (Noémie Merlant) gradually persuade her to abandon jihadism. Conversely, online recruiter Abou Hussein (Akim Mebtouch) persuades the previously well-adjusted Mélanie (Naomi Amarger) to successfully flee for Syria.

Both were released during the état d’urgence declared by then President François Hollande after the Paris attacks of November 2015. This state of exception granted French authorities expanded powers to maintain security, including those to place individuals under indefinite house arrest without charge, close meeting places, and raid premises on the basis of suspicion alone. During the two years that the état d’urgence was active, these measures were almost exclusively applied against Muslims, many of whom complained of excessive force or racial abuse from police officers (see Muhammad Citation2017, 196–198; Wolfreys Citation2018, 19–22). Both Amnesty International (Citation2017) and a parliamentary commission (Pietrasanta Citation2016, 263) demonstrated during the état d’urgence that it was ineffectual in preventing terrorism. Regardless, Macron ended it in 2017 only after inscribing several of its most repressive measures into permanent counterterrorism law (Loi renforçant la sécurité intérieure et la lutte contre le terrorisme Citation2017). It was, as noted above, also in 2015 that Stop-Djihadisme was rolled out. When released in 2016, the films thus entered a discursive environment in which state repression of Muslims and civilian-led counterterrorism were increasingly normalised.

Dounia Bouzar

The work of Dounia Bouzar, then director of the Centre de prévention contre les dérives sectaires liées à l’islam (CPDSI), helped validate the criminalisation of so-called ‘signaux faibles’ of jihadi radicalisation by programmes like Stop-Djihadisme. Bouzar’s work on ‘déradicalisation’ was recognised by Hollande’s government in 2014, when the CPDSI was granted state funding (Perrotin Citation2015). In 2016, though, she cut ties with the state in protest at Hollande’s plan to enable the déchéance de nationalité of dual nationals convicted of terror offences (Vincent Citation2017). She has now largely withdrawn from public life, but was previously outspoken and controversial, her fellow terrorism scholars raising numerous concerns with her claims and methodologies (see Grimmer Citation2017; Hegghammer Citation2016, 3–5; Perrotin Citation2015; Pétreault Citation2016).

The most notable aspect of Bouzar’s work is her (2014, 17–19, 42–43, 179–180) understanding of jihadi radicalisation as a ‘dérive sectaire’. Jihadism, and non-violent forms of fundamentalism, she argues, are cults: manipulative recruiters indoctrinate vulnerable people into adopting an extremist ideology unrelated to any theologically valid understanding of Islam. Bouzar is particularly significant here because she advised both Durringer and Mention-Schaar as they developed their films (Granel Citation2016; Poitte Citation2016). In Le Ciel attendra, she even appears as herself, and is represented in quasi-hagiographic fashion, her advice to jihadis and their families invariably being proven correct by subsequent events. This article will argue that both directors’ uncritical adoption of Bouzar’s frames of understanding helps explain their reproduction of the individualised vision of jihadi radicalisation that has underpinned recent French counterterrorism discourse.

Didactic films

Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter (Citation2009, xiv, xxiii) argue that, within neoliberal regimes, media take on the responsibility for shaping the subjectivities of their consumers. As Johnson (Citation2011, 151) puts it, media ‘steps in for the government as an agent of social welfare, instilling in … viewers the ability to take care of themselves’. While cinephiles may protest that including cinema in such analyses reduces the seventh art to purely instrumentalist political stakes, that objection would be difficult to uphold in relation to the films discussed here: both Durringer and Mention-Schaar explicitly characterised their productions as didactic interventions, pre-emptively undermining any such defence of their creative freedom. Durringer described Ne m’abandonne pas as having a ‘dimension politique et sociétale’ and an ‘aspect pédagogique’ which are ‘très fort[s]’ (Camier Citation2018). The film was first screened on France 2 during a night of programming exploring the question ‘qui sont ces jeunes qui partent faire le jihad?’ (Bourgoin Citation2016). It was thus framed primarily as teaching viewers how to understand real-world jihadi radicalisation rather than as engaging imaginatively with the subject. Mention-Schaar similarly described Le Ciel attendra as a true-to-life representation of the phenomenon. She emphasised her film’s rigorously documented nature, underlining that she had spent three months observing young jihadis following the CPDSI’s ‘deradicalisation’ programme before filming. As they promoted the film together, Bouzar claimed that ‘Marie-Castille a complètement absorbé le quotidien de ces jeunes … et les acteurs le redonnent aujourd’hui à tous les spectateurs’ (Granel Citation2016). Their framing of the film, like Durringer’s of Ne m’abandonne pas, thus emphasised its supposed realism rather than any artistic qualities. Mention-Schaar emphasised her desire for Le Ciel attendra to play a didactic role, recommending that schoolteachers show it to their classes, a suggestion echoed by then Minister of National Education Najat Vallaud-Belkacem. Vallaud-Belkacem’s ministry also bought the rights to Ne m’abandonne pas so that teachers could do likewise with Durringer’s film (Benamon Citation2016; Kerviel Citation2016). Numerous schools, municipal authorities, and independent organisations have duly arranged screenings of both as part of their anti-radicalisation strategies (Camier Citation2018; Granel Citation2016; Kerviel Citation2016). Both films, then, entered the discursive field framed as teaching viewers about real-world jihadi radicalisation rather than primarily imaginative representations of the phenomenon.

Civilian-led counterterrorism

Before arguing that both films reproduce an individualised vision of jihadi radicalisation, it will be useful to discuss how that vision underpins both civilian-led counterterrorism and Bouzar’s work. Discussing the United Kingdom’s statutory PREVENT policy, Kaleem (Citation2022, 268) notes that, by claiming to train laypeople to detect signs of jihadi radicalisation, civilian-led counterterrorism programmes encourage them to become de facto counterterrorism agents. That Stop-Djihadisme and Castaner reproduced this move is particularly concerning given that both, drawing on Bouzar’s work, referenced practices like wearing a headscarf, praying regularly, or observing Islamic dietary restrictions as potential signs of jihadi radicalisation (see Bouzar Citation2014, 22–23). Doing so criminalised such visible markers of Muslimness, encouraging the reporting of any ‘visible’ Muslim as a potential radical. Defenders of Bouzar or French counterterrorism policy could object that neither argue that the above signs, alone, necessarily constitute evidence of radicalisation. Rather, a sudden adoption of these practices, particularly in conjunction with other factors like an uncharacteristic hostility to family and friends, may constitute a ‘signal faible’. Nonetheless, encouraging citizens to report Muslims as potential jihadis on the basis of these putative warning signs gives at best well-meaning amateurs and at worst racists responsibility for judging when visible markers of Islam become suspicious (see Kaleem Citation2022, 274). It is therefore unsurprising that human rights NGOs have denounced the punitive impacts of these counterterrorism policies on innocent Muslims (see Hourdeaux Citation2019).

While Bouzar has complained that these policies oversimplified her work (see Vincent Citation2017), her understanding of the term ‘radicalisation’ lends itself to such appropriations. In the ongoing scholarly debate over who should be considered ‘radical’ (see Neumann Citation2013, 874–875), she falls on the side that includes committed pacifists. She (Bouzar Citation2014, 17) defines as radical not only jihadis, but ‘tout [musulman] qui utilise la religion pour s’auto-exclure de la société’. This includes, for example, those unwilling to shake hands with the opposite sex and women who wear full-body veils, even if they condemn violence: such behaviour, Bouzar (Citation2014, 179–180) claims, betrays a desire to self-segregate which ‘prédispose l’individu à la violence’. Her work thus validates the criminalisation of many Muslims who have never expressed any support for violence on the basis of a highly questionable putative predisposition to jihadism.

Furthermore, by dismissing jihadis as brainwashed cult members, she refuses to treat them as ideologically convinced agents, depoliticising the battle against jihadism by framing it as a moral struggle against nefarious recruiters. Those recruiters, she claims, target vulnerable youths and gradually ‘reformat[ent] le cerveau du jeune en question … comme on peut reformater un disque dur’ (Bouzar Citation2014, 67–68). They convince recruits to support jihadism less through theological or ideological persuasion, she claims, than by exploiting their insecurities, attributing their feeling that they are misunderstood to their being one of God’s chosen defenders of Islam against a Western plot. She (2014, 67–68) describes the process as a ‘lavage de cerveau’, generating a ‘mise en veilleuse des facultés intellectuelles’.

Her equation of fundamentalist movements with cults impacts upon how Bouzar believes jihadi radicalisation should be tackled. Because she considers radicals brainwashed rather than ideologically convinced, she (2014, 181) is ‘pas très optimiste sur la possibilité de ramener un radicalisé à la raison’ through ideological or theological persuasion. Indeed, arguing with them will only further convince them that there is a conspiracy against ‘la Vérité’ (Bouzar Citation2014, 181). Instead, their loved ones must engage with them affectively. They should ‘[leur] préparer [leur] gâteau préféré, repasser [leur] film adoré, afficher des photos de vacances … maintenir les liens coûte que coûte, pour contrer les radicaux qui s’efforcent de soustraire leurs proies à ceux qui ont participé à leur socialisation’ (Bouzar Citation2014, 22–23). She labels this strategy the ‘madeleine de Proust’ method (Bamba Citation2016). Surrounding the radicalised with happy memories, she claims, can return them to their senses by reminding them of the value of the relationships they have been manipulated into abandoning. Jihadis, then, are neither ideologically convinced agents nor products of the flaws and misdeeds of contemporary Western nations (for example structural racism or aggression in majority-Muslim nations). Opposing jihadism need not entail any engagement with those problems. Instead, Bouzar dismisses jihadis as the brainwashed victims of malevolent recruiters, with ‘deradicalisation’ becoming merely a matter of bringing them to their senses. As Rodrigo Jusué (Citation2022) notes, such framings depoliticise jihadi radicalisation by focusing purely on ‘the individual, ignor[ing] a broader reading of historical, social, political, and cultural contexts in which conflicts are generated’. Younis (Citation2021) agrees, noting that ‘psychology talk’ around counterterrorism ‘serves as a key component in avoiding the question of institutional racism …. In the great neoliberal tradition, it is the individual … who is held ultimately responsible—the system remains irreproachable’.

This depoliticisation of jihadi radicalisation may help explain why both Hollande’s and Macron’s governments based their counterterrorism interventions on Bouzar’s work. In adopting her framing, they disregarded any suggestion that French foreign policies, colonial histories, or institutional discrimination helped create the conditions for France to produce ‘home-grown’ jihadis. Such claims have been made by researchers like Roy (Citation2016, 48–49), Benslama and Khosrokhavar (Citation2017, 89–90), David Thomson (cited in Pétreault Citation2016), or Moran (Citation2017), who describe jihadis as ideologically convinced actors rather than brainwashed victims. Thomson therefore criticised Bouzar’s programmes for dismissing the ‘convictions religieuses et politiques’ of jihadis. Instead, they treated them like ‘des alcooliques anonymes’, having them participate in group therapy sessions ‘un peu comme si on avait à traiter une pathologie psychiatrique’ (Pétreault Citation2016). Moreover, while French-born jihadis are thus framed in her work and ostensibly state policy as able to be ‘rescued’ if their radicalisation is detected early enough, the recruiters accused of indoctrinating them are completely othered: as Guéguin (Citation2022) notes, their ideological motivations are also disregarded, leaving only a putative ‘irrational hatred and fanatical ideology to destroy our civilisation’. Even the motivations of those who are not framed as brainwashed, then, remain wholly depoliticised.

Neither Bouzar nor civilian-led counterterrorism are unique in disregarding French society’s role in creating its own jihadis. The latter has broken new ground less by individualising the blame for jihadi radicalisation than by making counterterrorism a civic responsibility. As Rodrigo Jusué (Citation2022) puts it, ‘citizens are expected to fully agree and cooperate with the state/authorities, to become security agents’ (see also Younis Citation2021, 42). Kaleem (Citation2022, 282) adds that outsourcing policing duties once seen as the prerogative of the state to the public reflects a notion of neoliberal citizenship that ‘shifts the rights and duties equation within the citizenship contract towards the idea of active or earned citizenship’. The state’s responsibility for protecting the populace by detecting signs of jihadi radicalisation recedes, with private individuals instead held responsible.

As the état d’urgence and Macron’s subsequent counterterrorism legislation demonstrated, however, the French state has not just retained but strengthened its punitive role. This too reflects developments associated with neoliberal governance. Carcerality has been a defining feature of economic deregulation: Wacquant (Citation2009, 273) notes that criminalisation and incarceration have been deployed to enable neoliberal governments to ‘symbolically reaffirm the authority of the state at the very moment they declare its impotence on the economic and social front’. In keeping with the cult of ‘personal responsibility’ underpinning neoliberal economics, vulnerable populations that fall through the cracks as state aid is reduced are blamed for their own poverty. Concomitantly, social problems, including criminality, that are correlated with deprivation are blamed not on structural neglect, but the ‘character flaws and behavioural deficiencies’ of marginalised populations (Wacquant Citation2009, 5–6). As state welfare spending has steadily diminished in France and elsewhere, spending on policing and incarceration has therefore increased: ‘the poverty of the social state against the backdrop of deregulation elicits and necessitates the grandeur of the penal state’ (Wacquant Citation2009, 19). Non-white populations already marginalised by pre-existing dynamics of racial exclusion have been disproportionately impacted by carceral expansion.

Fernando (Citation2014, 199–200) underlines that these observations hold true in France: law-and-order policies have been wielded to blame populations of postcolonial immigrant descent, and particularly those racialised as Muslim, living in deprived quartiers populaires,Footnote3 for the social and economic marginalisation generated by decades of neoliberal reforms (see also Wacquant Citation2009, 270–286). Muslim men have been targeted with rhetoric implying that they are congenitally sexually violent and ‘prime recruits for Islamic fundamentalism’ (Fernando Citation2014, 198–199). Muslim women who wear veils or headscarves, and deny being forced to do so by those supposedly controlling men, find themselves similarly problematised as fundamentalists. Official discourses thus imply that Muslims are excluded due to their own unassimilable nature rather than structural or socio-economic factors; that unassimilable nature, in turn, is invoked to justify carceral measures like the massive imprisonment of men or legislation against veiling practices (Fernando Citation2014, 198–199, 203–204). Wacquant noted in 2009 (24–25, 58–59) that, alongside traditional carceral bodies like police and prisons, social services were now ‘play[ing] an active part in this criminalising process, since they possess the administrative and human means to exercise a close-up supervision of so-called problem populations … instituting a social panopticism’. Civilian-led counterterrorism extends the carceral regime still further by framing participation in this social panopticon as the responsibility not just of social services but also of private citizens. Interventions justified through reference to Bouzar’s work and near-exclusively targeting populations racialised as Muslim have thus both reflected and extended broader patterns of racism and carcerality within neoliberalism.

Le Ciel attendra and Ne m’abandonne pas

Jihadi radicalisation as brainwashing

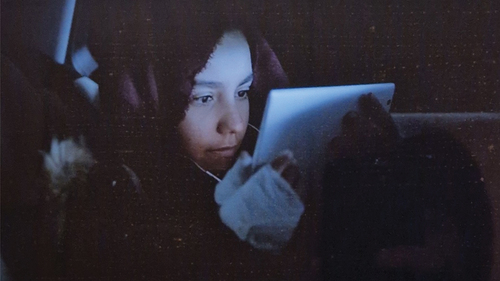

Both films explored here reproduce Bouzar’s vision of jihadi radicalisation as cultish indoctrination. By representing the battle against it as one between good and evil individuals, respectively each protagonist’s parents and their daughters’ recruiters, they implicitly depoliticise jihadism in France. Chama’s and Sonia’s parents ‘deradicalise’ their daughters purely through Bouzar’s affective methods, with no theological or ideological persuasion required. In Le Ciel attendra, Bouzar the protagonist personally advises Sonia’s parents to apply her ‘Madeleine de Proust’ method. Sonia’s mother, Catherine (Sandrine Bonnaire), follows her instructions, playing a home video from her daughter’s childhood later that evening. As a young Sonia pets the family dog on screen (), Catherine asks the older version if she remembers the pet, to which she scornfully replies that ‘je suis pas amnésique’. Nonetheless, she keeps watching, hands over mouth in defensive posture (). Having previously been entirely hostile to her parents, Sonia now shows the first signs of her wavering resolve: when Catherine gently murmurs that ‘tu aimais bien ce chien’, she remains silent momentarily before muttering ‘je suis fatiguée; je vais me coucher’. After several meetings with Bouzar and a partial reconciliation with her parents, Sonia is seen removing photographs of herself with family and friends from a box to display them in her bedroom. There is already adhesive on the wall where she places the images, suggesting that she is returning them to previous positions from which she removed them after being brainwashed. Bouzar’s ‘madeleine de Proust’ method, then, is validated, Sonia returning to herself after Catherine reawakens her childhood memories.

Figure 1. A home video played by Catherine shows a young Sonia playing with the family dog, Pistache. Screenshot from Mention-Schaar’s Le Ciel attendra (UGC, Citation2016).

Figure 2. A teenage Sonia watches the video. Screenshot from Marie-Castille Mention-Schaar’s Le Ciel attendra (UGC, Citation2016).

In Ne m’abandonne pas, the representative of a support group for ‘parents orphelins’ gives Chama’s father Mehdi (Sami Bouajila) advice identical to Bouzar’s, telling him that radicals use ‘la technique des sectes’ to indoctrinate vulnerable youths. She advises him to ‘ramenez [Chama] à l’enfant qu’elle était’ to win her back. Chama’s parents, like Sonia’s, therefore implement the ‘madeleine de Proust’ method. Having isolated Chama in a country house owned by Louis/Abderrahmane’s father, Adrien (Marc Lavoine), Mehdi and her mother, Inès (Samia Sassi), put numerous items from her childhood on display, adorning the walls with photographs. As Chama later contemplates the display, a rare over-the-shoulder shot invites the viewer to share her perspective, implying that this previously incomprehensible young woman is already becoming slightly less so. Nonetheless, she is more resistant than Sonia. Like Catherine, Inès reminisces with her daughter about a family dog; Chama turns its photograph to face the wall, flatly stating that ‘un chien, c’est impur’.

Despite Chama’s stubbornness, the ‘madeleine de Proust’ method is eventually validated. She still tries to escape for Syria, helped by Adrien, who betrays Chama’s parents in the hope of being reunited with Louis/Abderrahmane. However, before departing, she leaves Inès a note reading ‘Ne pleure pas. On se retrouve au paradis. Je t’aime maman’. A point-of-view shot lets the viewer read the letter with Inès, accentuating a sense of intimacy and demonstrating the thawing of their relationship even as Chama escapes. After Inès and Mehdi prevent her departure, helped by ex-jihadi Manon (Louise Szpindel), whom they met through the association for ‘parents orphelins’, Chama flees to the hospital where Inès works as a doctor. While reminiscing about Chama’s childhood, Inès had earlier evoked ‘ta peur du noir quand tu venais dormir à l’hôpital’. Chama was unresponsive at the time, but her instinct upon abandoning her plan is to head for that same hospital, where Inès finds her sobbing in the dark. Bouzar’s methods have apparently borne fruit.

By depicting those methods succeeding, both films implicitly validate Bouzar’s depoliticised understanding of jihadi radicalisation as brainwashing. When Chama’s or Sonia’s parents challenge their daughters’ theologico-political worldviews, it achieves nothing beyond triggering a shouting match. Both girls return to themselves after being reminded of their love for their families, never again mentioning political concerns, like racism in France or human rights abuses in Syria, which they evoked while radicalised. Such concerns are thus represented identically to every other aspect of the girls’ ‘brainwashing’. They are, the films imply, simply part of the indoctrination process, and not political drivers of jihadi radicalisation worth taking seriously. Once ‘deradicalised’, Sonia underlines that her actions were motivated by brainwashing rather than genuine conviction by remorsefully reflecting that ‘j’étais endoctrinée … J’étais plus moi-même’. The viewer also sees the brainwashing process taking place as Hussein exploits Mélanie’s vulnerability after her grandmother dies to render her dependent on his apparent emotional support. He subsequently indoctrinates her using online conspiracy-theory videos, which start by speaking in comparatively benign anti-consumerist language but become increasingly radical, accusing a multinational ‘corporatocracie’ of manipulating Westerners into ‘la perversion … la perte des valeurs et de la foi’. The disorienting nature of these scenes communicates to the viewer the similarly disorienting psychological impact of Hussein’s brainwashing techniques. Audio from the videos continues to play, uninterrupted, as visual footage alternates between the videos themselves: medium and close-up shots of Mélanie watching them in a darkened bedroom, bathed in the glow from her laptop, and, in a none too subtle piece of visual symbolism, in her physical education class, unsteadily advancing along a balancing beam from which she appears ready to fall at any moment. That she has been brainwashed into joining a cult rather than responding, however abhorrently, to contradictions in contemporary Western society is underlined when she resolves to leave for IS territory. She remains unable to separate her (pseudo-)political motivations from her dependence on Hussein: although she fulminates via Facebook that ‘je hais ce pays de mécréants’, this religio-political statement comes only after she first writes ‘je veux partir avec mon prince’, indicating her true priority. By depicting jihadi radicalisation as brainwashing, both films entirely depoliticise the phenomenon.

‘Signaux faibles’

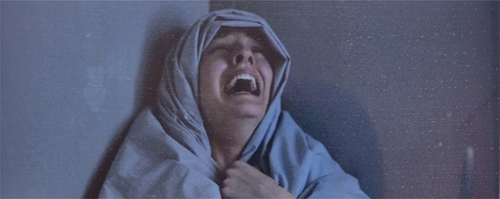

Both also depict visible markers of Islam like those Stop-Djihadisme listed as potential signs of jihadi radicalisation, and particularly veiling practices, as inherently suspect. Both directors use the veils or headscarves their protagonists start wearing as signifiers both of their embrace of the jihadi ideology and their submission to their male recruiters. In keeping with dominant French discourses, veils and headscarves thus become inseparable from radical fundamentalism, with women who wear them either the victims of controlling men or themselves dangerous fundamentalists. Durringer’s linkage of the headscarf, the putative subservience of Muslim women to Muslim men, and jihadism is underlined when Chama systematically dons hers every time that she video-calls Louis/Abderrahmane (). The headscarf is thus linked with the racist stereotype of the Muslim woman as always submissive to Muslim men, but also appears when Chama is represented as most fanatical. After she warns Inès that, if prevented from leaving for Syria, she will ‘fa[ire] péter des trucs ici’, her enraged mother throws her wedding ring into a lit fire, only for Chama to lunge in to retrieve it. Refusing to let Inès treat her burned hand, she locks herself in her bedroom; upon forcing the door, Inès finds her daughter, whose hair was previously uncovered, adjusting her hijab as she kneels to pray. Both veiling and prayer are thus linked simultaneously to Chama’s endorsement of armed jihad and the fanaticism encapsulated in her diving into a lit fire. Later scenes retain this linkage: one opens with a close-up of her burnt hand before zooming out to show a hijab-wearing Chama praying, seeming to communicate that a fanaticism that hurts Chama herself, veiling, and prayer are inseparable elements of her radicalisation as a jihadi. Similarly, in Le Ciel attendra, after a shouting match in which she has denounced Catherine as a ‘mécréante’, Sonia throws herself into her bed, sobbing. She then grabs her bedcovers and wraps them around her hair in the style of a headscarf before starting to pray, loudly, in Arabic (). Racist and sexist stereotypes rooted in colonial discourses around the supposed hysteria of Muslim women are thus linked visually and aurally in both films to veiling, prayer, and the Arabic language. Most significantly for the current purposes, all three are also represented as inseparable from jihadi radicalisation, recalling Bouzar’s and Stop-Djihadisme’s characterisation of them as potential ‘signaux faibles’ of jihadi radicalisation.

Figure 3. Chama, headscarf on, video-calls Louis. Screenshot from Durringer’s Ne m’abandonne pas (TV5 Monde, Citation2016).

Figure 4. Bedcovers wrapped around her head, Sonia sobs after an argument with Catherine. Screenshot from Mention-Schaar’s Le Ciel attendra (UGC, Citation2016).

Both directors also use the headscarf to signify all that separates their young protagonists from their parents by using the motif of protagonists touching each other’s hair to symbolise an intimate connection between them. While still hiding her intention to leave for Syria, Chama plays with Inès’s long, uncovered hair as her mother prepares their evening meal. Later, while trying to rebuild a relationship with their daughter that lies in tatters, both of her parents stroke Chama’s hair. Similarly, in Le Ciel attendra, a partially ‘deradicalised’ Sonia climbs into Catherine’s bed late one night, sobbing that, having tried to distance herself from her jihadi network, she has ‘reconnecté’ because ‘c’était plus fort que moi’. Her words evoke the quasi-hypnotic control implied by Bouzar’s interpretation of jihadi radicalisation as a ‘dérive sectaire’; a close-up shot shows Catherine stroking her daughter’s hair in this moment of reconnection, hugging her and repeating that ‘je te lâche pas’. If it is by touching their daughters’ hair that both sets of parents express their love for them, the headscarf creates a physical and symbolic barrier to their doing so, recalling the wedge that Bouzar claims the jihadi ‘cult’ drives between indoctrinated youths and their families. As Martin (Citation2011, 33) puts it in a different context, ‘filming a veil is filming a separation’.

The closing scenes of both films strengthen this impression. Chama, having renounced her departure for Syria, sobs as Inès caresses her now uncovered hair, the two women’s heads framed by the camera as they sit side by side on the hospital floor. A soft-focus, extreme close-up subsequently shows the back of Chama’s head, her hair blurring the screen, before the film ends on a tracking shot following her and Inès as they rise and walk towards (presumably) the hospital’s exit. While their faces are not visible, their long, uncovered hair is. The last time that the viewer saw Chama, when Manon intercepted her during her attempted flight for Syria, she was wearing her headscarf; she has apparently removed it upon renouncing her plan. Le Ciel attendra ends, meanwhile, with a close-up shot showing Sonia smiling as she leans out of her parents’ car window, her similarly uncovered hair billowing in the wind. The freedom this represents is contrasted with Mélanie, wearing a full-body veil in a nondescript industrial setting: having presumably arrived in Syria, she fades into a silhouette as a static shot shows her walking into the distance. The shot symbolises her future, the garment serving to ‘enl[ever] [ses] contours identitaires’, as Bouzar described its purpose earlier in the film. Both films thus end by centring either the uncovered hair of ‘deradicalised’ protagonists or a protagonist who has arrived in IS territory, her hair covered. That both directors chose to close with these images highlights their use of veiling practices to symbolise the jihadi ideology itself.

Their portrayals of the headscarf recall those in earlier French productions. Tarr (Citation2014, 532–533, 551) argues that even films that sought to ‘challenge … unified, inflexible, monocultural vision[s] of French identity’ have not ‘attempt[ed] to problematize the negative stereotype of the young veiled Muslim woman in France’. Instead, when such women have been depicted at all, they have typically been ‘either portrayed as rigid and intolerant’, ‘refused a voice’, or ‘ridicule[d]’. Few French productions have subverted the stereotype of the hijabi Frenchwoman as either passive victim of controlling men or seditious Islamist.

Nonetheless, despite expressing personal discomfort with the headscarf, Bouzar (Citation2014, 165–166) denies that headscarves, in isolation, constitute evidence of radicalisation. She (2014, 176–177) does, however, unequivocally dismiss full-body veils as always imposed by ‘les radicaux’. Bouzar’s vision is more faithfully reproduced in Le Ciel attendra than Ne m’abandonne pas. In Mention-Schaar’s film, the headscarf is problematised, as discussed above, but not unambiguously equated with jihadism: one hijabi protagonist, Mélanie’s classmate Djamila (Sofia Lesaffre), overtly rejects fundamentalism. Bouzar’s dismissal of full-body veils as unambiguously ‘radical’, meanwhile, is reproduced by Bouzar herself as a protagonist. Speaking to a group of young women following her ‘déradicalisation’ programme, she denounces the jilbab, which covers its wearer’s full body but not her face, as imposed by recruiters to efface the subjectivity of female recruits. A shot/countershot structure shows both Bouzar addressing these women, some of whom are wearing a jilbab, and their reactions: all gaze at her attentively, some nodding to indicate recognition of the process she describes. Full-body veils thus become an unambiguous synecdoche for jihadi radicalisation, brainwashing, and patriarchal domination, with Hussein’s growing influence over Mélanie reflected in his persuading her to wear increasingly concealing veils. In one scene, footage of a ‘deradicalised’ Sonia at home, happily interacting with her parents, is interspersed with images of Mélanie excitedly trying on her new full-face-covering niqab. Hussein’s voice is superposed over these scenes, commanding Mélanie to always answer her phone when he calls, and asking if she has ‘tenu [s]a promesse’ and ‘arrêté la musique’. Mélanie subsequently appears in her niqab, playing her beloved cello, presumably for the last time; the music continues unbroken, non-diegetically, as Sonia offers to help her parents by fetching her younger sister, Emilie (Arauna Bernheim-Dennery). As she approaches Emilie’s bedroom, the rhythm accelerates; when she enters, the music abruptly halts and so does she. Another close-up registers her shocked face, the reason for which is subsequently revealed: Emilie is wearing a jilbab, presumably Sonia’s own. The camera returns to Sonia, gulping in visible horror. The scene links veiling both to Hussein’s indoctrination of Mélanie and to his gendered assumption of authority over her, with Sonia’s horror upon seeing Emilie communicating that Mélanie’s experiences are representative.

The adoption of a veil or headscarf is not the only so-called ‘signal faible’ that each film depicts as signifying jihadi radicalisation. Le Ciel attendra problematises what it represents as overly assiduous practice of Islam by contrasting Mélanie with Djamila, whom she mistakenly assumes will share her new-found fundamentalist outlook. When Mélanie invites Djamila to visit, her mother, Sylvie (Clotilde Courau), gives the girls a chocolate eclair each. Djamila is delighted, but Mélanie declines to eat her eclair, which contains pork gelatine. When Djamila laughs that she will eat anything that does not ‘ressemble à un porc’, Mélanie wordlessly averts her eyes. An alarm subsequently alerts her that it is time to pray; now visibly uncomfortable, Djamila avoids eye contact while agreeing to join her. Throughout the process, she is less concerned than Mélanie with orthopraxy, laughing aloud when she asks for advice on the minutiae of the gestures she should perform. As Mélanie indignantly glares at her, Djamila explains that ‘je crois pas qu’Allah soit … dérangé par ce genre de détail’. The camera zooms to focus first on Djamila’s smiling face and then on Mélanie’s: both are framed by their hijabs as Djamila explains that ‘ce qui compte, c’est ce que tu as au fond du cœur’, while Mélanie glares back. Scandalised, Mélanie later denounces her now ex-friend to Sylvie as a kufar (infidel). The scene is ambivalent. By foregrounding Djamila’s hijab, it communicates, in line with Bouzar’s views, that the garment is not necessarily always a ‘signal faible’ of jihadi radicalisation. Simultaneously, however, it associates strict orthopraxy with radicalism, recalling Bouzar’s and Stop-Djihadisme’s designation of behavioural changes like a sudden investment in Islamic dietary restrictions as signs of radicalisation. The sequence implies that some investment in embodied Islamic practices (for instance not eating foods that look like pork) is ‘acceptable’, but that ‘too much’ investment (like wearing a jilbab or refusing to eat pork gelatine) is inherently suspect. As noted above, encouraging lay people to judge what constitutes ‘too much Islam’ risks criminalising any visible marker of Islam.

Ne m’abandonne pas more overtly validates state counterterrorism discourses criminalising such so-called ‘signaux faibles’. As Inès, alerted by Adrien to her daughter’s plans but still unconvinced, searches online for information on jihadi radicalisation, a point-of-view shot lets the viewer share her perspective as she consults the Stop-Djihadisme website itself. Immediately before and after, she is presented with a tick-list of the types of warning sign the site detailed. After Adrien visits, using a photograph of Chama wearing a hijab during her online wedding to Louis/Abderrahmane to ‘prove’ her intentions, she finds Chama’s grandmother (Tassadit Mandi) correcting her Arabic pronunciation, thus discovering that she is learning Arabic. The following morning, she tells Chama that she slept poorly after drinking champagne; her daughter responds that ‘l’alcool, c’est du poison’. Inès then observes that Chama has stopped eating meat, to which Chama responds by claiming to have become vegetarian. Chama, then, is learning Arabic, wearing a hijab, and abstaining from alcohol. Her ‘vegetarianism’, as Inès later underlines to Mehdi, is a front to mask her abstention from non-halal meat. Not only is Bouzar’s and Stop-Djihadisme’s analytical framework validated by Chama showing the kinds of ‘signaux faibles’ they describe; the site itself helps Inès recognise those signs.

Both films thus fail to engage with French society’s own role in creating French jihadis while simultaneously criminalising visible markers of Islam. If their protagonists are vulnerable rather than malicious, meanwhile, there is no corresponding humanisation of their recruiters, who appear one-dimensionally evil. ‘Deradicalisation’ thus becomes a moral battle against those malevolent recruiters, in which private individuals play a decisive role by identifying ‘signaux faibles’ of jihadi radicalisation. The reproduction in both films, through their depictions of veil- or headscarf-wearing protagonists, of the stereotype of the Muslim woman as passive victim of Muslim men contributes to this impression. By depicting young Muslim women being brainwashed by jihadi men, and using veiling practices to symbolise that indoctrination, both films fold together this stereotype, familiar within mainstream French discourses, and that of the jihadi as passive victim of their recruiter (see McQueen Citation2021, 140–141). Reproducing this racist, sexist, and infantilising trope denies the protagonists of both films genuine agency: given their role as brainwashed (female) victims of manipulative (male) recruiters, both films suggest that their motivations need not be taken seriously. The motivations of those male recruiters, meanwhile, are entirely unexplored: being wholly malevolent figures, they too, as discussed above, are depoliticised. Both films thus draw on pre-existing gendered and racialised stereotypes to reproduce the depoliticisation of jihadism underpinning civilian-led counterterrorism. Moreover, both consequently grant a circumscribed sympathy only to protagonists who are middle-class young women, but not to the young men who more recognisably fit the stereotyped image of the ‘home-grown’ jihadi. The young men who have been most impacted by racialised counterterrorism policies, that is, are implicitly excluded from any sympathy that they imply their protagonists deserve. In keeping with Guéguin’s (Citation2022) characterisation of French counterterrorism discourse as rooted in a colonial continuum, such young men emerge as ‘savage[s] … barbarian[s] … bestial and irrational’. Both thus suggest in theory that French jihadis can be ‘saved’ while simultaneously implying that enough incomprehensible barbarians remain among them (perhaps a majority) to validate the state repression that was being enacted when both films were released.

One might object to the complaint that the films focus on the individual, depoliticised motivations of their protagonists rather than the systemic causes of jihadi radicalisation in France that such a focus is standard in mainstream narrative cinema. By focusing on the subjective and interpersonal, both films go with the grain of the mainstream. It would have been hard for either director to construct a compelling narrative without centring the subjective dimensions of their protagonists’ experiences. This article does not intend to suggest that these elements of the films should have been excluded entirely. Nonetheless, neither director described their work primarily as an imaginative engagement with ‘home-grown’ jihadism. Instead, both championed the putative didactic qualities of their respective films: an interpretation broadly accepted by reviewers and state bodies. In this context, considerations other than entertaining viewers must have fed into the production process: to uncritically reproduce any specific vision of the contested issue of what drives jihadi radicalisation, and a fortiori a state discourse that has been used to validate repressive law-and-order policies directed against Muslims, remains problematic.

Equally, if narrative cinema often focuses on the familial sphere, the portrayals of Muslim family units in both films did not so much follow the mainstream as depart from it in ways that reproduce the ideological assumptions of French counterterrorism policy. Kealhofer (Citation2013, 185–188, 195) and Tarr (Citation2005, 81, Citation2011) note that French productions featuring young women racialised as Muslim have consistently depicted them struggling to escape an essentialised, patriarchal Arab-Muslim ‘culture’ imposed by their parents (see also Bouteldja Citation2016, 75–76). Where French productions have not actively avoided foregrounding Muslims or Islam (see Cadé Citation2011), they have depicted young women being impeded by Muslim parents from being emancipated by the Republic: an outcome they desire, and which is usually in the Republic’s power. The implication is that French people (or at least women) of Muslim heritage are gradually shedding the alterity associated with an essentialised ‘Islamic culture’ attributed to their parents and grandparents.

While such depictions are problematic, Ne m’abandonne pas and Le Ciel attendra diverge from them in ways that are equally so. Far from depicting young protagonists defying ‘traditionalist’ Muslim parents by becoming republicans, Durringer and Mention-Schaar depict Chama and Sonia defying republican Muslim parents by becoming jihadis. Both girls’ parents become stand-ins for the nation: rebuilding their relationship with their family, for both, becomes synonymous with reconstructing their allegiance to the Republic. Their parents’ disciplining of them is not represented as culturally determined misogyny, but conversely as the Republic protecting its ‘brainwashed’ children. This divergence from the hackneyed depiction of traditionalist Muslim parents repressing the incipient republicanism of their daughters does not imply an absence of stereotyping. Rather, the films reproduce an anxiety rooted in their own post-2015 context, that young French Muslims should be viewed with suspicion as potential ‘home-grown’ jihadis. Furthermore, by representing both sets of parents as republicans who are apparently unconcerned by systemic racism both directors naturalise the republican ideology, evacuating any question of how its own exclusionary underpinnings contribute to jihadi radicalisation. Once again, the issue is wholly depoliticised.

Counterterrorism as civic duty

As well as individualising the blame for jihadi radicalisation, both films individualise the responsibility for detecting and preventing it. Not only do Chama and Sonia’s parents assume these counterterrorism duties; state representatives appear inept in both areas. In Ne m’abandonne pas, Adrien, and not state forces, alerts Chama’s parents to her radicalisation after discovering her online ‘wedding’ to Louis. The state intelligence apparatus has apparently failed where this antique dealer succeeded in detecting a French jihadi online. Subsequently, Mehdi suggests to Inès that they sign an interdiction de sortie de territoire to keep Chama in France. Inès dismisses such measures as ineffectual, underlining that ‘tous les jours on entend parler des gamins qui passent la frontière alors que leurs parents les ont déjà signalés’.

State forces do eventually become aware of Chama, but not through their own surveillance. Rather, the schoolteachers of her younger siblings report to the authorities that they, under Chama’s influence, are showing signs of Islamist radicalisation. Counterterrorism performed by private citizens (the teachers) thus alerts the state, rather than its own intelligence-gathering. Even once aware of Chama, the police are incongruously toothless. When two officers question her, they already know that Chama has, unbeknown to Inès, used her mother’s tablet device to video-call Louis/Abderrahmane in Syria earlier that day. Given that the state has this surveillance capacity, it is unclear how she had previously avoided detection. Her rudimentary efforts to avoid detection, a second Facebook account that IT professional Mehdi found by hacking her laptop, were apparently beyond the capacities of the French intelligence apparatus. Indeed, state forces seemingly immediately lose track of her again after the interview, not reacting when she calls Louis/Abderrahmane while fleeing for IS territory and explicitly discusses how she plans to get there. During the interview itself, meanwhile, Chama is openly defiant, telling the officers interviewing her to ‘allez [se] faire foutre’ before storming from the room. Inexplicably, they take no further interest in her, apparently deciding that her visibly overwhelmed parents have this situation under control.

Inès and Mehdi subsequently recognise that preventing Chama from reaching Syria is their responsibility, and not that of the state forces theoretically responsible for doing so. After realising that she has left with Adrien, rather than contacting the police they break into Adrien’s apartment, where Mehdi discovers their planned itinerary by hacking his computer. Rather than contacting the authorities, they then concoct an elaborate plan for Manon to pose as an IS intermediary and persuade Chama, whose resolve is already wavering following the application of Bouzar’s methods, to renounce her departure. In keeping with the neoliberal logics underpinning civilian-led counterterrorism, individual initiative succeeds where the state failed.

In Le Ciel attendra, the state is still more ineffectual in protecting vulnerable protagonists from jihadi recruiters. The film starts with Sonia having already been prevented from leaving for Syria. This was, however, down to luck rather than state action: a flashback sequence shows the viewer that before leaving France, she called her unsuspecting parents to say goodbye, only to faint while (successfully) passing passport control, enabling them to rush to the airport and catch her. Sylvie’s experiences after Mélanie reaches IS territory further underline the state’s inability to protect its children. Resolving to go to IS territory and find Mélanie herself, she pleads with a journalist who has covered the Syrian conflict to help her get there. Faced with his unwillingness, she protests that she has no option: ‘le gouvernement s’en fout, personne ne fait rien!’ When she later makes the same complaint to an unidentified state representative, he responds by lamenting that ‘si on pouvait aller chercher … on sait jamais où ils sont. Vous savez où est votre fille, vous?’ When Sylvie replies in the negative, his stricken rejoinder is ‘Alors comment fait-on?’ That France’s state intelligence apparatus is by any reasonable measure better placed to locate French jihadis in Syria than their civilian parents apparently crosses neither his mind nor Sylvie’s. The exchange nuances her earlier claim that the state does not care about Mélanie: the state emerges as well-meaning but powerless to safeguard its children, leaving their parents solely responsible for ensuring that they do not reach IS territory to begin with.

Both films thus reproduce the neoliberal logics of civilian-led counterterrorism by responsibilising individuals, and not the state, for surveillance and prevention. Where parents succeed in preventing their daughters from reaching IS territory, it is because they embrace this responsibility, educating themselves on which ‘signaux faibles’ to look out for and actively performing surveillance on them. After Inès spots the ‘signaux faibles’ Chama is displaying, an over-the-shoulder shot enables the viewer to watch her daughter leave for school with her. The moment Chama is out of sight, Inès rushes to search her bedroom. Later scenes continue to emphasise her constant surveillance over Chama, whether by having the viewer share her perspective or through medium shots foregrounding Chama while her concerned mother watches over her in the background (). That Adrien, following Louis/Abderrahmane’s departure for Syria, has embraced his role as a de facto counterterrorism agent (albeit too late) is visually signified when Inès and Mehdi visit his home. His apartment wall is covered in maps and systematically arranged photographs of his son’s associates, recalling the trope of the evidence board often deployed in detective fiction.

Figure 5. A medium shot foregrounds Chama video-calling Louis while Inès watches over her in the background. Screenshot from Durringer’s Ne m’abandonne pas (TV5 Monde, Citation2016).

The assumption of counterterrorism duties in the state’s place by Sonia’s parents in Le Ciel attendra is formal. When Sonia, having failed to reach IS territory, is arrested for planning an attack in France, a judge underlines that if they want her to stay at home, her parents must maintain the same conditions as the ‘centre fermé’ where she would otherwise be detained. How seriously they take their counterterrorism duties is underlined when Catherine wakes in the dead of night, fretting to Sonia’s father, Samir (Zinedine Soualem), that ‘j’ai entendu la clé de la serrure de la porte d’entrée’. Even while sleeping, she is still performing surveillance.

Significantly, when parents in Ne m’abandonne pas educate themselves on how to detect or challenge jihadi radicalisation, it is often online. Images abound of Inès or Adrien staring at computer or tablet screens; as noted above, it is while tracking Louis/Abderrahmane online that Adrien becomes aware of his son’s marriage to Chama. Subsequent scenes show Inès learning, through her tablet device, about the jihadi ideology and the risks Chama will face if she leaves for Syria. A point-of-view shot allows the viewer to watch with her as a video warns would-be jihadis that those who join IS ‘découvrir[ont] l’enfer sur terre et mourr[ont] seul[s], loin de chez [eux]’. The next shot shows Inès front on, eyes glued to the screen as the video’s soundtrack continues uninterrupted. The repeated shots of parents educating themselves through audiovisual media, presented on a screen, invite viewers to think reflexively about their audiovisual consumption of Durringer’s film, treating it as a similarly educational experience. Durringer made explicit his hope that viewers would approach his film in exactly this fashion, using it to teach themselves how to ‘reconnaître certains signes avant-coureurs sur la radicalisation’ (Camier Citation2018).

As Kaleem (Citation2022, 279; see also Rodrigo Jusué Citation2022, 292–293) notes, framing such civilian-led counterterrorism as safeguarding rather than punitive intrusion renders it more palatable to the populace. It is therefore significant that even the most intrusive and restrictive counterterrorism actions performed by parents in both films are depicted as motivated by their desire to safeguard their daughters. In Le Ciel attendra, when Catherine begs the judge to let Sonia return to the family home following her arrest, the judge underlines that detaining her there will diminish the whole family’s quality of life: ‘absolument aucun accès à Internet, ni au téléphone et elle devrait être accompagnée … si elle sort de la maison. Vous imaginez bien ce que ça représente pour vous?’ A close-up shows Catherine’s stricken face; the film then cuts to a tracking shot of the family car taking Sonia home, implying that regardless of the hardships involved, little consideration of whether to do so was necessary. Catherine may effectively imprison her daughter, but is motivated by a concern for Sonia that renders her personal situation unimportant. In Ne m’abandonne pas, Inès applies still more drastic discipline by drugging Chama so that she can transport her to Adrien’s country house, where she hopes to isolate her until she is ‘deradicalised’. After gently putting her daughter to bed upon arrival, Inès awakens the following morning at Chama’s beside, having clearly spent the night there. When Chama awakens, Inès rushes to her, cradling her, and enjoins her to rest even as her daughter pushes her away, protesting that ‘tu m’as piquée, tu me séquestres’. While Chama’s words are incontestably true, Inès’s actions demonstrate that these disciplinary tactics are motivated by concern for her wellbeing.

This is one of several scenes in both films where a protagonist’s parents attempt to rebuild their relationship with their daughters while on or beside their respective beds. Later, as Mehdi struggles to understand Chama’s attempts to indoctrinate her younger siblings, he too sits beside her on her bed, stroking her hair. As noted above, when Sonia confesses to Catherine that she has ‘reconnecté’ with her jihadi network, she climbs into her mother’s bed, sobbing, in the middle of the night. These scenes of both girls’ parents either putting them to bed or sharing their bed underline their safeguarding role by calling to mind images of early childhood. In doing so, they contribute to the infantilisation of both Chama and Sonia, validating the civilian-led counterterrorism their parents perform as protecting young women clearly too impressionable to be left to their own devices: acts motivated by love, and a desire to protect, rather than the imposition of discipline in place of the state.

In both films, proactively performing surveillance on one’s own family for so-called ‘signaux faibles’ is thus depicted as both a civic and familial responsibility. While not all of the families in these films are Muslims, the expectations of civilian-led counterterrorism weigh particularly heavily upon individuals racialised as such. Those imperatives intersect with a broader set of expectations associated with being a ‘good Muslim’ in France: one who, in particular, accepts the neo-republican injunction to relegate religious practices entirely to the private space. Such a vision of what constitutes an ‘acceptable’ Islamic self-understanding is encapsulated in Ne m’abandonne pas when Mehdi remonstrates with Chama that ‘Je suis un bon musulman …. Parce que tous les jours je me demande comment être plus heureux … comment être meilleur’. He and Inès both adhere to this neo-republican vision of suitably ‘French’ Muslimness: both are professionally successful, keep their faith to the private sphere, and show little investment in embodied practices such as abstinence or prayer. In Le Ciel attendra, Djamila expresses a similar vision to Mehdi by responding to Mélanie’s concerns over orthopraxy that ‘ce qui compte, c’est ce que tu as au fond du cœur’. As Asad (Citation1993, 45–46, 58–59, 66–67, 72–73) has shown, understandings of religion as defined through interior belief rather than embodied practice define the religious according to Christian, Eurocentric histories. Consequently, they map poorly on to how many Muslims understand their faith. This implies no criticism of Islamic self-understandings like those Mehdi or Djamila articulate. However, representing (even if only implicitly) these subject positions as the only route to acceptable Frenchness, with embodied practices like regular prayer or veiling criminalised as potential ‘signaux faibles’ of jihadi radicalisation, casts suspicion upon many observant Muslims who condemn violence. The imperatives of civilian-led counterterrorism thus, in both films, form a system with a broader set of pre-existing expectations that French Muslims must navigate to perform the role of suitable ‘Frenchness’: expectations that exclude many who would not consider themselves ‘radical’ by any definition.

Rodrigo Jusué (Citation2022) notes that characterising counterterrorism as every good citizen’s responsibility also often means blaming ‘those who “failed” to imagine potential dangers and/or did not actively make referrals to the authorities’ for the consequences. The depictions of Ne m’abandonne pas’s Adrien and Le Ciel attendra’s Sylvie assume their full significance in this context. Both fail to perform their counterterrorism ‘duties’, pay the price by losing their children, and are left as tragic, guilt-ridden figures. Like Inès, Sylvie is presented before Mélanie’s departure with a tick-list of ‘signaux faibles’, but unlike Chama’s mother she fails to notice. When Mélanie coldly refuses her offer of an appointment with a beautician (rejecting dominant beauty standards in favour of Hussein’s idea of female ‘modesty’), Sylvie expresses surprise, but no more; after her daughter refuses to eat a meal she prepares, dismissing it as ‘dégueulasse’, she exasperatedly responds that she cannot survive on fruit and vegetables alone. Like Chama, Mélanie is apparently disguising her refusal to eat non-halal meat as a matter of taste; where Inès recognises this ‘signal faible’, however, Sylvie assumes that her daughter’s motivation is weight loss. Even Mélanie’s dismissal of Djamila as a kufar does not alert Sylvie that anything more concerning is afoot.

After her blindness enables Mélanie’s departure, Sylvie is a broken woman, whose only remaining interest is reaching Syria to be reunited with her daughter. She only appears with other characters either at Bouzar’s support group or to ask for help in finding Mélanie. Otherwise, she is entirely alone, a series of long shots emphasising her solitude in various settings. Where Chama and Sonia’s parents seek to reconnect with their daughters through touch, Sylvie can only caress photographs of Mélanie as a child, or, more tragically still, a computer screen displaying a map of the Syrian city of Raqqa. Sympathetic though Sylvie is, she recognises that her torment is just punishment for her blindness, lamenting that she cannot understand how she was ‘si conne … de n’avoir rien vu’. She even wonders aloud if someone ‘si nulle’ should be allowed to bear children, framing counterterrorism not just as a civic responsibility, but a component of competent parenting.

Adrien is similarly broken by Louis’s departure. He lives alone, obsessively tracking Louis/Abderrahmane online. His son seemingly never leaves his mind: in one scene, the camera follows him through his empty apartment until he wearily sits at his computer desk. Mournful non-diegetic music plays as it slowly pans to show the viewer that he is watching a video of a small child, presumably the younger Louis, playing. A close-up of his face shows him smiling, through tears, at these happy memories. His betrayal of Chama’s parents is motivated not by antagonism, but a need to be reunited with his son at all costs. Seeing his father’s unwillingness to help Chama escape for Syria, Louis/Abderrahmane manipulates him into doing so by flatly asking: ‘c’est ta dernière chance de me revoir, alors tu choisis quoi?’ Adrien knows that he will risk his life in the process, but sees no option; following the call, despite his son’s manipulative behaviour, he reaches out and gently touches the frozen image of Louis/Abderrahmane’s face on his computer screen. Like Sylvie, he cannot reconnect with his son through touch, this motionless simulacrum of a young man who holds him in contempt being the closest he can come. Equally like Sylvie, Adrien overtly states that he is to blame for his own situation. When advising Chama’s parents to isolate her, he underlines that ‘si j’avais su faire la même chose avec mon fils il serait pas parti’. Like Sylvie, Adrien’s tragic fate is clearly framed as punishment for his failures to perform his counterterrorism ‘duties’.

The carceral state

If both films depict the state as unsuited to the safeguarding duties private citizens perform, however, they symbolically validate its repressive role. This resonates with Wacquant’s observation that, as market deregulation has eroded the ability (or willingness) of neoliberal states to protect the vulnerable, their capacity to punish deviance has risen. Such repression was being particularly fiercely enacted against French Muslims when both films discussed here were released, during the état d’urgence. It is highly suggestive that Chama’s and Sonia’s parents both reproduce the indefinite house arrest that the état d’urgence enabled by forcibly confining their daughters in their homes. Equally, that all search the private spaces of their respective daughters recalls the widespread raids of Muslim-owned premises. Even while depicting private citizens deputising for a state that cannot be entrusted with safeguarding, both films thus symbolically legitimise state repression.

Furthermore, state forces in both films are capable of fulfilling these repressive functions, even if safeguarding is beyond them. In Ne m’abandonne pas, while Inès scoffs that Mehdi’s idea of signing an interdiction de sortie de territoire would be ineffectual, she refuses to report Chama to ‘les flics’: despite dismissing their ability to help keep Chama in France, she remains worried by the prospect that her daughter will be ‘fichée comme intégriste’. Equally, the officers who fail to detect Chama’s eventually abortive attempt to abscond for Syria do highlight their carceral capacities, underlining to her that she risks up to five years’ imprisonment and a hefty fine for associating with terrorists. In Le Ciel attendra, police who do little to help Sonia’s family similarly fulfil their repressive duties. Early in the film, having discovered Sonia’s plan to commit a terror attack in France, heavily armed and masked police raid the family home in the dead of night in scenes reminiscent of a police thriller. The sight of militarised police apprehending Sonia in her own bedroom underlines the role of state forces in the film: not to support or safeguard, but to repress and punish. Later, Bouzar underlines to a still radical Sonia that ‘tu devrais être contente d’être … encore chez toi! Les autres sont en détention provisoire ou en centre fermé’, further underlining that the state remains capable of performing its carceral functions, even while outsourcing safeguarding.

Conclusion

Both Ne m’abandonne pas and Le Ciel attendra uncritically adopt Bouzar’s vision of jihadi radicalisation as cultish brainwashing, reproducing a criminalisation of visible markers of Islam that still underpins French counterterrorism discourse. Consequently, both films also reproduce Bouzar’s highly individualised vision of how to combat jihadism, evacuating all representation of its structural drivers. Instead, the fight against it becomes a moral battle between good parents and evil recruiters, within which ideological persuasion is useless: jihadis are ‘deradicalised’ purely through affective engagement. Furthermore, both films’ depictions of parents assuming counterterrorism duties resonate with the discourse of civilian-led counterterrorism, which outsources the responsibility for detecting putative signs of jihadi radicalisation from state forces to citizens. Both, however, represent state forces that retain their capacity to repress. Each film thus reproduces the individualising and carceral logics of neoliberal governance. That both are so strongly encoded with an exclusionary dominant ideology is particularly problematic given that their directors explicitly framed them as pedagogical interventions: a framing accepted by schools, independent associations, and even the then Minister of National Education.

Other films have represented jihadi radicalisation with more nuance. Like Durringer’s and Mention-Schaar’s films, Rachid Bouchareb’s La Route d’Istanbul (Citation2016) depicts a young woman, Élodie, seeking to leave Europe (Belgium, although Bouchareb is French) to join IS in Syria. The idea that she has been brainwashed, however, is evoked but not overtly validated: not only Élodie herself, but also other non-jihadi protagonists protest that her embrace of jihadism was willed rather than forced upon her. Élodie’s circumstances as an apparently affluent white woman do not invite any consideration of structural racism in her homeland, but the issue of Western foreign policy is hinted at: when Elodie’s mother meets the people trafficker who smuggled her daughter into Syria, he shows no contrition, instead unexpectedly lambasting her over Western indifference to the struggles of his compatriots. Before reaching IS territory, meanwhile, Elodie is maimed and several of her friends killed not by IS’s own violence, but in a Western drone strike. Where Durringer and Mention-Schaar unambiguously align their narratives with Bouzar’s understanding of what causes jihadi radicalisation, Bouchareb leaves more space for viewerly interpretation.

If the choice of all three directors to centre female protagonists suggests that a cinematic space remains to partially humanise jihadi women (albeit, for Durringer and Mention-Schaar, paradoxically only by reproducing the dehumanising stereotype of the Muslim woman as victim), it is unclear that the same is true for jihadi men. Nicolas Boukhrief’s Made in France (Citation2015) depicts a journalist infiltrating an all-male jihadi cell planning an attack in Paris. Boutouba (Citation2019, 215–216) praises the film for, unlike other Western films about jihadism, humanising its protagonists. However, Boukhrief’s film was produced before the attacks of 2015, and Boukhrief struggled even then to find partners willing to work with him; after the attacks, its festival appearances and cinematic release were cancelled. It was eventually released only via video on demand (McQueen Citation2021, 131–132). Where Mielusel (Citation2020) underlines that Philippe Faucon’s La Désintégration (Citation2011) depicts disenfranchisement caused by systemic racism as a factor in jihadi radicalisation, this film predates all of the jihadi attacks that have occurred in France since 2012. In the post-2015 context, the already limited space for humanising jihadi men like those responsible for the attacks within which these earlier films operated has perhaps receded still further: the criticisms made of both productions discussed here, then, may reflect less on their directors than the limited discursive space available for French films to do anything other than reproduce dominant discourses around jihadi terrorism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Friends and colleagues of Harpon, including serving police intelligence officers, had already reported him to the relevant authorities numerous times (Suc Citation2022). Whatever failures preceded the attack, insufficient suspicion of or willingness to report Harpon within his entourage were not among them.

2. Researchers including Kundnani (Citation2012) and Silva (Citation2018) consider the term ‘radicalisation’ inherently compromised, having since its inception been applied to criminalise Muslim communities. This article uses it to denote the process by which individuals (Muslim or otherwise) come to support political violence. It is retained as the most recognisable term for that phenomenon, but is not used uncritically.

3. France’s quartiers populaires are not wholly populated by populations of postcolonial immigrant descent, and nor do all French people of postcolonial immigrant heritage live in quartiers populaires. The two categories are, however, routinely conflated in public discourses.

References

Primary sources

- Durringer, X. 2016. Ne m’abandonne pas. Paris: TV5 Monde.

- Mention-Schaar, M.-C. 2016. Le Ciel attendra. Paris: UGC Distribution.

Secondary sources

- Amnesty International. 2017. France: Vos droits en danger. Paris: Amnesty International.

- Asad, T. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Bamba, A. 2016. “Déradicalisation, la méthode Dounia Bouzar expliquée (1/3).” Saphir News, October 7. https://www.saphirnews.com/Deradicalisation-la-methode-Dounia-Bouzar-expliquee-1-3_a23014.html

- Benamon, S. 2016. “Le Ciel attendra: “personne n’est à l’abri de la radicalisation”.” L’Express, October 5. https://www.lexpress.fr/culture/cinema/le-ciel-attendra-personne-n-est-a-l-abri-de-la-radicalisation_1836798.html

- Benslama, F., and F. Khosrokhavar. 2017. Le jihadisme des femmes. pourquoi ont-elles choisi daech? Paris: Seuil.

- Bouchareb, R. 2016. La Route d’Istanbul. Paris: 3B Productions.

- Boukhrief, N. 2015. Made in France. Paris: Canal.

- Bourgoin, A. 2016. “A voir ce soir: “Ne m’abandonne pas” sur France 2.” Paris Match, February 3. https://www.parismatch.com/Culture/Medias/Ne-m-abandonne-pas-sur-France-2-907385

- Bouteldja, H. 2016. Les Blancs, les juifs et nous: Vers une politique d’amour révolutionnaire. Paris: La Fabrique.

- Boutouba, J. 2019. “Through the Lens of Terror: Re-imaging Terrorist Violence in Boukhrief’s Made in France.” Made in France. Studies in French Cinema 19 (3): 215–232. doi:10.1080/14715880.2018.1528536.

- Bouzar, D. 2014. Désamorcer l’islam radical: Ces dérives sectaires qui défigurent l’islam. Paris: Editions de l’Atelier.

- Cadé, M. 2011. “Hidden Islam: The Role of the Religious in Beur and Banlieue Cinema.” In Screening Integration: Recasting Maghrebi Immigration in Contemporary France, edited by S. Durmelat and V. Swamy, 41–57. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Camier, G. 2018. “Xavier durringer: “la radicalisation ne touche pas que les musulmans”.” La Dépêche, February 6. https://www.ladepeche.fr/article/2018/02/06/2736917-xavier-durringer-la-radicalisation-ne-touche-pas-que-les-musulmans.html

- Dyer-Witheford, N., and G. de Peuter. 2009. Games of Empire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Faucon, P. 2011. La Désintégration. Paris: Pyramide Distribution.

- Fernando, M. 2014. The Republic Unsettled: Muslim French and the Contradictions of Secularism. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Granel, S. 2016. ““Le ciel attendra”: Un film pour mieux comprendre la radicalisation des jeunes.” France Info, September 27. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/culture/cinema/le-ciel-attendra-un-film-pour-mieux-comprendre-la-radicalisation-des-jeunes_3341237.html

- Grimmer, J. 2017. “Déradicalisation: Les résultats de Dounia Bouzar sont-ils crédibles?” Le Point, June 26. https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/deradicalisation-les-resultats-de-dounia-bouzar-sont-ils-credibles-26-06-2017-2138413_23.php

- Guéguin, M. 2022. “Terrorism as an Unprecedented and Long-Term Threat to National Security Posed by an “Other”: The Securitization and Crystallization of Exceptional Extraordinary Powers in France”. Paper presented at the European Union Studies Association 17th Biennial International Conference, Miami, May 19.

- Hegghammer, T. 2016. “Revisiting the poverty-terrorism Link in European Jihadism.” Paper presented at Society for Terrorism Research Annual Conference, Leiden.

- Hourdeaux, J. 2019. “Les “signaux faibles”, outil de contrôle des populations.” Mediapart, October 11. https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/111019/les-signaux-faibles-outil-de-controle-des-populations?onglet=full

- Johnson, D. 2011. “Neoliberal Politics, Convergence, and the do-it-yourself Security of 24.” Cinema Journal 51 (1): 149–154. doi:10.1353/cj.2011.0071.

- Kaleem, A. 2022. “The Hegemony of Prevent: Turning counter-terrorism Policing into Common Sense.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 15 (2): 267–289. doi:10.1080/17539153.2021.2013016.

- Kealhofer, L. 2013. “Maghrebi-French Women in French Téléfilms: Sexuality, Gender, and Tradition from Leïla Née En France (1993) to Aïcha: Vacances Infernales (2012).” Modern and Contemporary France 21 (2): 183–198. doi:10.1080/09639489.2013.776735.

- Kerviel, S. 2016. ““Le ciel attendra” libère la parole sur la radicalisation.” Le Monde, November 22. https://www.lemonde.fr/cinema/article/2016/11/22/le-ciel-attendra-libere-la-parole-sur-la-radicalisation_5036050_3476.html

- Kundnani, A. 2012. “Radicalisation: The Journey of a Concept.” Race & Class 54 (2): 3–25. doi:10.1177/0306396812454984.

- “Loi no 2017-1510 Du 30 Octobre 2017 Renforçant La Sécurité Intérieure Et La Lutte Contre Le Terrorisme (1).” 2017. accessed 22 February 2021.

- Martin, F. 2011. Screens and Veils: Maghrebi Women’s Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- McQueen, F. 2021. “Race, Religion, and Communities of Friendship: Contemporary French Islamophobia in Literature and Film.” PhD., University of Stirling.