Abstract

In the process of implementing EU policy, Member States sometimes introduce new policy instruments in cases where this is not obligatory. To better understand this phenomenon, this paper reviews three cases in which new instruments emerged and develops a methodology to trace back the influence of EU Directives on instrument choice. The method is illustrated by a narrative of the emergence of new management planning instruments during the implementation of the EU Habitats Directive in three EU Member States: Finland, Hungary and the Netherlands. Three key features of a policy instrument are defined, namely, its authoritative force, action content and governance design. These are used to measure the contribution of the Habitats Directive compared to other potential explanatory causes for the emergence of the new policy instrument. In all three reviewed countries a nested causal relationship between the Habitats Directive and the introduction of the new policy instrument is identified. Based on the relative contribution of the Habitats Directive to the emergence of the new instrument a distinction is made whether the Directive acted as a cause, catalyst or if conjunction occurred.

1. Introduction

Most countries struggle to implement European Union (EU) Directives (Mastenbroek Citation2005) as they need to be put into operation in a setting in which existing policies, instruments, discourses and actor coalitions are already present (Goetz and Dyson Citation2003). Overall governments are reluctant to change their policy instruments, although changes in policy instrumentation occur (Howlett Citation2009; Salamon Citation2002). However, unless there is a requirement by the EU, the introduction of new policy instruments might be caused by various factors which may be domestic, European or even global. So if new policy instruments emerge in the process of EU policy implementation in cases where there is no legal EU-requirement, how can we determine the relative contribution of the EU policy to their emergence? This paper reviews the emergence of new policy instruments in a well-developed policy field, the field of nature conservation, and proposes a method for assessing the contribution of EU policy to instrument choice.

Nature conservation policy in the EU Member States has a history dating back long before the creation of the EU. Protected areas for nature had already been designated at the beginning of the 20th century (Mose and Weixlbaumer Citation2007). The requirement of the Habitats (1992) Directive to designate protected areas, called Natura 2000 sites, was already part of the nature conservation policy of many of its Member States. Furthermore, the development of management plans is a widely applied approach for the management of protected areas (Hockings Citation2003). It is therefore intriguing that at least 10 Member States have decided to develop new management planning instruments for Natura 2000 sites, although no formal obligation to do so exists (Bouwma et al. Citation2016); particularly, because the drafting of these management plans requires considerable efforts from the government as well as stakeholders. This raises the question: why did the implementation of this particular EU Directive lead to the emergence of new policy instruments in several Member States, in the absence of a legal obligation, and whether this can be attributed to the Habitats Directive?

The aim of this paper is twofold. First, an analytic aim of the research is to determine whether there is a relationship between the introduction of the new policy instrument and the Habitats Directive and, if so, whether this is a causal relationship. As the Habitats Directive does not prescribe the use of a particular instrument, no simple direct cause-and-effect relationship exists. This brings us to the second, and more theoretical, aim of the paper; in order to assess the nature of the relationship a method was devised to relate the new instrument to different developments occurring in the policy field.

Based on our analysis, we will draw different conclusions about the type of causal relationships existing between the emergence of the instrument and the Habitats Directive. Depending on the relative influence of the Habitats Directive, we distinguish three different types of causal relationships: cause, catalyst and conjunction. If the new instrument is the immediate result of changes in the national policy domain due to the Habitats Directive, the latter is considered the main cause. If the new instrument is shaped by ongoing processes at the domestic level which were strengthened by the Directive, the latter is acting as a catalyst. In case the instrument is the result of two or more interrelated causes, one of which was the Directive, we refer to conjunction in this third situation. We conclude the paper with more generic conclusions regarding the circumstance under which Member States, in the absence of an EU obligation, nevertheless feel compelled to develop new instruments while implementing EU policy.

The paper follows an approach called historical narrative – a method regularly applied to shed light on causal relationships in policy research (Mahoney Citation1999). It presents a description of the policy context in which new instruments were introduced in three Member States (Finland, Hungary and the Netherlands). Section 2 presents the method developed to determine causality from causality-theory and policy instrument theory. Section 3 describes the criteria for country selection and the research approach. Section 4 provides a short description of the Habitats Directive and presents the narrative and conclusions in the three selected counties. In Section 5, we reflect on the implications of our findings for the existing theories on the influence of EU on policy instruments in its Member States.

2. Determining cause and outcome in policy instrument change

2.1. Causal relationships

Scholars from a wide range of different disciplines have written about the complexities involved in determining causal relationships. In its simplest interpretation, causality relates to a situation in which event A causes B and event B does not occur without event A. A distinction is made between a ‘necessary’ condition, which is a condition that must be present for the event to occur, and a ‘sufficient’ condition or conditions that will produce the event. In a probabilistic interpretation, a factor is seen as a cause if its presence increases the likelihood of an outcome (Gerring Citation2005). In policy research, however, there is often a sequence of events and processes, leading to a complex situation in which many causal relations exist and interdependencies occur, so we have to deal with ‘complex causality’. The challenge is to identify which causes are necessary and sufficient conditions in situations of complex causality (Steinberg Citation2007).

In instrument choice literature, different causes for the emergence of new policy instruments have been suggested; from learning processes of involved actors (Hall Citation1993), struggles between involved actors (Sabatier Citation1998), changes in governance modes and policy regime logics (Hall Citation1993; Howlett Citation2009) and the emergence of governance networks (Bressers and O'Toole Jr Citation1998). In respect to the EU policy creating the conditions for instrument change, three types of EU-influences have been identified in literature, namely, institutional compliance, change in domestic opportunity structures and impact on beliefs and expectations (Knill Citation2001; Knill and Lehmkuhl Citation2002; Treib Citation2014). Institutional compliance is used to indicate the process of adjusting the EU Member States legal and administrative procedures to EU requirements, for instance, the transposition of Directives or the obligation to introduce a particular policy instrument. The EU can also more indirectly influence the distribution of power and resources between domestic actors by supporting particular organisations, promoting particular instruments or products. The impact of the EU on beliefs and expectations might occur as some policies promote a set of European values, such as a healthy environment, or frame problems in a particular manner (Knill and Lehmkuhl Citation2002).

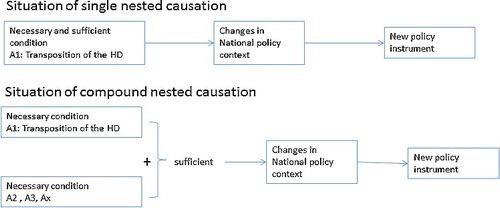

In the case under consideration, there is no simple direct cause-and-outcome relationship, as the Habitats Directive does not prescribe the use of a particular management instrument (see Section 5). We therefore need to assess whether the changes the Habitats Directive brought to the national policy arrangements were sufficient to lead to the introduction of the new policy instrument, or whether other causes also contributed to the creation of the required conditions. Steinberg (Citation2007) describes various types of causal relationships occurring in situations in which indiscriminate pluralism occurs. The case we are reviewing is considered as a nested causation. In such a situation, one or more events (A1–Ax) are necessary for event B to occur, which in turn is necessary for event C to occur. We distinguish two different types of nested causations: single nested causation and compound nested causation. In the first instance, there is one constituent cause which acts as a necessary and sufficient condition for another necessary cause which leads to the outcome. In the second instance, there are several unrelated necessary constituent causes which together act as a set of sufficient conditions for another necessary cause or set of causes to produce the outcome (see ). Nested causation therefore differs fundamentally from situations in which a dependent variable is predicted and accounted for by the preceding independent variable.

Figure 1. Different types of causal relationships between the introduction of the Habitats Directive and the new policy instrument.

A particular difficulty in determining cause–outcome relations in policy research is that, often, only a few cases for research exist and statistical methods are therefore either not applicable or have a limited application (Mahoney Citation2000; Steinberg Citation2007). In his review of different methods for macro causal analysis, Mahoney (Citation1999) argues that narrative can be a useful tool for assessing causality in situations where temporal sequencing, particular events, and path dependence must be taken into account. Because temporal sequencing, particular events and path dependency (Bouwma et al. Citation2016) are likely to have played a major role in the cases under consideration, we present a narrative account of the developments which took place prior to the emergence of the new instrument. In order to increase the explanatory power of our narrative, we combine two existing approaches applied in policy research, namely the outcome-based causal assessment approach (Steinberg Citation2007) and the policy arrangement approach (Arts and Leroy Citation2006).

2.2. Outcome-based causal assessment

In an outcome-based causal assessment, one constructs a metric with respect to the outcome and analyses how far one or another antecedent is responsible for the outcome (Steinberg Citation2007). A metric is a system or standard of measurement. In the case of policy instruments, we have to develop a metric that allows us to determine how the new instrument differs from those already in place. We therefore have to identify the key features of the instrument. After describing the key features, we can establish to what extent they reflect the changes in the national policy context and, consequently, which events were the causes of these changes in the policy context.

The existing literature on instruments enables us to identify the key features of a policy instrument. A policy instrument is developed by the government in order to influence the behaviour of a specific actor (Bemelmans-Videc and Rist Citation1998; Salamon Citation2002). It requires the actor to undertake or to refrain from a certain action. Each instrument therefore has a certain action content. In the case of compliance, the actor might receive benefits, in the case of non-compliance governmental sanctions may follow. Each policy instrument therefore has a certain authoritative force. Important key features of policy instruments are therefore the action content and authoritative force (Vedung Citation1998).

The definition of policy instruments which is put forward by Vedung (Citation1998) is formulated from a government-dominated perspective which was prevalent in much of the early literature on policy instruments. This perspective was increasingly challenged under the influence of the governance debate (Kjaer Citation2004; Rhodes Citation1997). A range of ‘new’ policy instruments emerged that were designed and implemented in close co-operation between the government and stakeholders (Jordan et al. Citation2003; Salamon Citation2002). So besides authoritative force and action content, another essential third key feature of the instrument is its governance design. The governance design describes which parties are involved in the development, approval, implementation and enforcement of a particular policy instrument. The three key features used in our analysis do not embody all aspects of instruments as distinguished in available typologies (for an overview, see Salamon Citation2002). But for the analytic scope of this paper they enable us to distinguish change between relatively comparable instruments in contrast to other aspects proposed, whose primary purpose is to categorise very different tools.

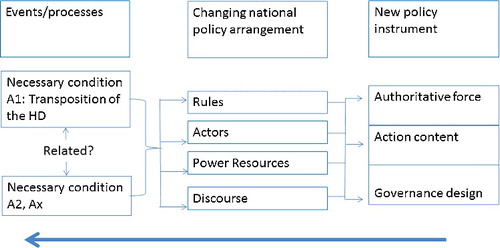

Based on the three key features, i.e. action content, authoritative force and governance design, we can characterise the new instruments and asses how they differ from their predecessors. The next step to assess causality is to link the key-features of the instrument to the changes, both organisational and the content (‘substance’), in the policy domain before and after the introduction of the Habitats Directive. The policy arrangement approach was selected in order to describe the changes as the approach takes into account both the organisational and substance side of the policy domain.

2.3. The policy arrangement approach

A policy arrangement refers to the temporary stabilisation of the organisation and substance of a policy domain, at a specific level of policy making (Arts and Leroy Citation2006). Change of a policy arrangement can occur due to policy initiatives (such as the Habitats Directive), socio-political trends, shock events, changes in adjacent arrangements (e.g. forestry or agriculture) and policy entrepreneurs (Arnouts Citation2010). The policy arrangement approach analytically distinguishes four dimensions, i.e. rules, discourse, actors and resources/power. The rule dimension refers to the formal rules embedded in legislation and official procedures. It also includes informal rules, norms or shared understanding, which are part of everyday practice. In this paper we will focus on the formal rules. The discourse dimension reviews the ideas, concepts and narratives which are prevalent in a specific policy domain. The discourse dimension relates both to general ideas about the relation between the state, market and society, as well as the concrete problem at stake. The actor dimension reviews which actors are involved in the specific policy field. What are their roles and responsibilities and how do they interact? The power/resources dimension relates to resources available to the various actors and how this influences their position of power in respect to each other. In this paper, this dimension particularly reviews the financial resources. Although four dimensions are distinguished, in reality they are closely interrelated and interdependent (Liefferink Citation2006).

2.4. Method for causal assessment of policy instrument emergence

The method to assess the relative contribution of the Habitats Directive in relation to the emergence of new policy instruments consists of the following consecutive steps:

Step 1:

Determine the change in key features. By comparing the action content, authoritative force and governance design of the new instrument with the ones in place, we can determine the extent to which the instruments have changed.

Step 2:

Asses how these modified key features are related to the changes in the national policy arrangement. Which changes in the four dimensions of the national policy arrangement occurred and have shaped the new instrument?

Step 3:

Assess the causes of the changes in the national policy arrangement. How much is the transposition of the Habitats Directive responsible for the change in the four dimensions of the policy arrangement or can we discern other causes?

In order to facilitate drawing conclusions from our narrative, we will schematically map the relationships between the key features of the new policy instrument, the relevant change in the four dimensions of the national policy arrangement and the Habitats Directive ( and –). Based on the key features of the instrument introduced, we will draw different conclusions about the type of relationship existing between the emergence of the instrument and the transposition of the Habitats Directive. If the key features of the new instrument were decisively impacted by the changes in the national policy domain due to the Habitats Directive, the Habitats Directive is considered as the main cause. In this case, no other events could have led to the introduction of an instrument with such a character (counterfactual reasoning). If the key features of the new instrument were shaped by ongoing processes at the domestic level, but which were strengthened by the Directive, we consider that the Directive is acting as a catalyst. The national domestic process and the EU process are independent and unrelated necessary conditions. Counterfactual reasoning leads to the conclusion that an instrument with such a character might have been introduced, even in the absence of the Habitats Directive. A situation can also occur in which there are two or more causes which are necessary conditions, but which are not independent from each other, but are interrelated. We refer to a situation in which the Habitats Directive together with an interrelated other cause is a necessary condition, as conjunction.

Figure 2. Outcome-based assessment of the possible causal relationships between the new instrument, the changes in the national policy arrangement and introduction of the Habitats Directive (arrow from right to left).

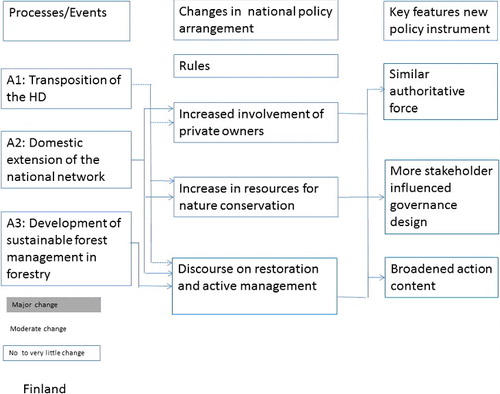

Figure 3. Causal relationships between the Habitats Directive, the national policy arrangement and key features of the new policy instrument in Finland.

3. Country selection and research approach

In comparative case studies of the impact of EU policies among EU States, one of the most difficult choices is the selection of cases (Haverland Citation2005). As we were interested in the circumstances in which change in management planning instruments occurred, the first of the selection criteria was whether the Member StatesFootnote1 introduced new instruments for the management planning of Natura 2000 sites (Bouwma et al. Citation2016). The second criterion was time of accession. Due to the expansion of the EU, some Member States were involved in the drafting and approval of the Habitats Directive. This provided them with the possibility of uploading their own policy goals and instrumentation to EU policy (Bulmer and Padgett Citation2005). Other countries joining after the Habitats Directive came into force were faced with implementing the directive as it stood. Between 1992 and 2004 the EU expanded slowly and only three countries joined, i.e. Finland, Austria and Sweden. In 2004, the accession of 10 Member States led to a major extension, the majority of these were from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (8 out of 10). The CEE states were facing particular implementation issues due to the transformation from a communist state and the strict deadlines set for transposition of EU legislation in order to accede (Hille and Knill Citation2006). Another criterion for selecting among the candidates was based on their geopolitical situation in Europe. The Netherlands was chosen as one of the founding members and promotor of the Habitats Directive in Citation1992 (Bennett and Ligthart Citation2001). Finland, as one of the Member States joining between 1992-2004, in which the Habitats Directive led to considerable implementation difficulties (National Audit Office of Finland Citation2007). Finally, from the CEE accession states Hungary was selected as the member state representing this group, since it generally performs well in implementing EU policy (Hille and Knill Citation2006).

The narrative describing the history of management planning in the respective countries was reconstructed based on available literature and semi-structured interviews. In each of the countries, interviews were held with staff of the Ministry responsible for implementation of the Habitats Directive, (state) organisation responsible for management of conservation areas, and a researcher or representatives of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) (10 interviews in total). Several of the respondents had been involved in the particular field for a long time and were therefore able to provide a detailed account of the events. The interview focussed on changes they had perceived in the management of protected areas, and the policy domain in general, following the introduction of the Habitats Directive. After a short introduction of this latter, the following section presents the change in the management planning instrument in each of the selected countries, followed by a description of the changes in the four dimensions of the national policy arrangement due to the Habitats Directive and other events.

4. Country case description

4.1. Introduction

The Habitats Directive is a legal act of the EU which needs to be transposed by all Member States into their national legislation. The aim of the Habitats Directive is ‘to contribute towards ensuring biodiversity through the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora’. The Directive stipulates that Member States should legally protect species listed and designate special areas of conservation for species and habitats which are listed in the various Annexes of the Directives.Footnote2 These sites, in combination with sites designated under the Birds Directive (1979), are called Natura 2000 sites and collectively form the Natura 2000 network. Member States need to ensure that necessary conservation measures are taken in the sites and should avoid activities that lead to the deterioration of natural habitats and the habitats of designated species. In order to ensure that conservation measures are taken, considerable freedom is given to Member States to select their own policy instrumentation (Article 6). The Habitats Directive does not specify which policy instruments should be used nor that public consultation is required. Although the instrument choice to manage the Natura 2000 sites is up to the Member States they should ensure that the conservation status of the species and habitats in the sites do not deteriorate by undertaking the necessary conservation measures and avoidance of damaging activities.

The following sections describe the cases. and provide a comparative overview of the cases, summarising the changes in policy instruments and the impact of the Habitats Directive on the respective policy arrangements.

Table 1. Comparison of changes in management planning instrument.

Table 2. Comparison of changes in national policy arrangement due to the Habitats Directive.

4.2. Finland

4.2.1. Change in management planning instrument

The history of management planning of state owned land began in 1978, with the development of facultative plans for National Parks (Pertulla Citation2006; Heinonen Citation2007). By the beginning of the nineties, this facultative planning system for National Parks was well developed. For other state owned conservation areas, no systematic management planning process was in place (Eidsvik and Bibelriether Citation1994). In 1996, a new nature conservation act was adopted which transposed the requirement of the Habitats Directives into Finnish law. This law included an obligatory requirement to draft management plans for National Parks, thus providing a statutory basis for a well-established practice. For other areas (e.g. strict nature reserve and other nature reserves) the law provides the option to develop management plans (‘facultative system’).

The discussion about changes required to Finnish management planning instruments for Natura 2000 sites was an internal governmental affair. In 2000, a working group was established to review the management requirements for Natura 2000 sites (Ministry of the Environment Citation2002). The working group concluded that the conservation values of smaller reserves in particular might be at risk given the high land use intensity in and around these sites and the absence of management plans. The working group proposed two actions which were implemented. This entailed, first, a review of all existing management plans and, if required, updating them to incorporate the Natura 2000 requirements. Second, it included a threats assessment for Natura 2000 sites without a management plan and, in case of threat, developing simple operational management plans for the sites.Footnote3 The Regional Environmental Centres became responsible for developing most of the plans for privately owned land and Metsähallitus for state owned land (Ministry of the Environment Citation2002). As prior to 2000, there had been neither a legal requirement nor an established practice to develop management plans for privately owned conservation areas, this proposal led to the development of a facultative management planning instrument for privately owned conservation areas. For state owned areas, it accelerated the process of developing facultative management plans, especially for small reserves.

The management planning system introduced since 2000, shows changes in two key features compared to the pre-existing instrument. Most importantly, the governance design of the instrument changed as new groups of actors became involved, namely, private owners and businesses. The plans are developed in consultation between owners, users and the government. Its action content altered slightly, as previously the instrument had focussed on reducing human influences on the site, while the new instrument also considers ‘conservation measures’ to be taken. Its authoritative force showed little change as, just like the pre-existing plan, no legal provisions exist to enforce the plan that go beyond the legal restrictions laid down in the Nature Conservation Act.

4.2.2. Changes in national policy arrangement

Overall, no major changes occurred to the rules for management of conservation areas between the two periods.Footnote4 The revision of the Nature Conservation Act in 1996 only led to minor changes, as the previous Act (1923/71) already provided the possibility for restricting various damaging activities in conservation areas. The adaptation pressure to comply with the Directive was therefore low. A requirement for consultation of affected parties by national conservation programmes was included. The Finnish approach to extension of the conservation area network was purchase driven. Private landowners could exchange their land, sell it or receive appropriate compensation in case they wanted to retain ownership. Since 1978, national conservation programmes have been in operation (Heinonen Citation2007). Due to the successful execution of these programmes, the area established in private ownership increased significantly after 1995 (Heinonen Citation2007; Paloniemi et al. Citation2012). The requirement to designate Natura 2000 sites increased the area already intended for designation under national programmes by only 2%. Nevertheless, the official announcement, to designate Natura 2000 sites created a strong response instigating changes in the discourse and actor dimensions. Prior to the announcement, private owners in general were unaware that their land had been earmarked for national designation, as before 2007 no statutory obligation for consultation existed (National Audit Office of Finland Citation2007). Private landowners fiercely opposed the designation of their land. It resulted in the largest legal complaint procedure in Finnish history. But despite the opposition, no revision to the rules applicable to conservation areas were made.

During the reviewed period, the dominant nature conservation discourse based on non or minimum intervention was enhanced by insights in relation to the need for human intervention to ensure conservation. The Finnish natural environment which is dominated by forests, lakes and mires led to a nature conservation philosophy that relied on reducing damaging human activities and non or minimum intervention principles for management: ‘In most of our sites the management that is required is to keep the areas untouched.Footnote5’ In the middle of the nineties, however, the awareness of the need to restore nature became an issue in Finnish conservation (Kuuluvainen et al. Citation2002). This led to the implementation of various large scale restoration programmes focussing on mires and forests at the end of the nineties, and a discourse in the forestry sector developed about how foresters could voluntarily contribute to nature conservation. Until that time, the non or minimum intervention principles underlying nature conservation had been in stark contrast with the utilisation principles underlying Finnish forestry, hindering co-operation between the two sectors (Primmer et al. Citation2013).

Comparing the two periods, a gradual shift in the actor dimension can be noted. Private landowners, especially foresters, become more involved in biodiversity protection in and outside of conservation areas. The Nature Conservation Act of 1996 stipulated the need to inform affected parties. Gradually, a broader range of stakeholders has become involved in the management of state owned areas, as a consequence of the guidelines for the involvement of stakeholders in the planning process for state owned land (Loikkanen, Simojoki, and Wallenius Citation1999). In the same year, the Act of Land Use and Building (1999) and the Environment Impact Assessment Procedure (1999) set out new procedures for the involvement of stakeholders in planning processes in Finland.

With regard to the resources dimension, there was a gradual increase in national resources allocated to both state and private landowners over the entire period (Heinonen Citation2007). Prior to 1996, some funding was allocated to the national programme to extend the protected area system. After 1996, several funding programmes were introduced that increased funding to fulfil both national and EU obligations. Membership of the EU complemented national resources, as Finland has been successful in using the European Commission (EC) LIFE programme in particular for restoration projects.

4.2.3. Relationship between changes in the policy arrangement and the management instrument

Our narrative shows that the new management planning system that was introduced resulted from changes in the national policy arrangement due to the transposition of the Directive, as well as several ongoing domestic processes. The extension of the protected area network and the associated increase in actors was a consequence of a process set in motion long before the implementation of the Habitats Directive. The discourse on active management embedded in the Habitats Directive intermingled with discourses which were developing simultaneously at the national level. Given the increase in privately owned nature reserves due to the national programme, it is likely that the Finnish government might have introduced a management planning system for private areas in the longer run in order to manage its many smaller privately owned reserves. We therefore conclude that the Habitats Directive acted as a catalyst for the ongoing processes in Finland (see ).

4.3. Hungary

4.3.1. Change in management planning instrument

Since the Act on Nature Conservation (1 January 1997), the preparation of a management plan has been compulsory for all nationally protected areas and their prescriptions are binding (Art. 36). In the following years, management plans have been developed for all National Parks and, to a lesser extent, for other conservation areas (Johnson, Duncan, and Oldenkamp Citation1998). In 2001, a decree was published detailing the required content of the management plans, prescribing an elaborate process of consultation and official approval (30/2001.XII.28).

The discussion on a new management planning instrument for Natura 2000 was mostly an internal government discussion and, to a lesser extent, representatives from research and NGO. Several reasons for introducing the new system of Natura 2000 maintenance plans can be discerned. First, many Natura 2000 sites did not fall under the existing planning system (Ministry of Environment and Water, undated). Second, the maintenance plans provide clarity on the type of conservation measures that can be subsidised, specifically for private owners (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2009). Thirdly, the negative experiences with the existing management planning process, in particular the process of drafting and official approval of these plans, was time-consuming due to extensive consultation procedure (pers med).

The new instrument was introduced in the 2008 amendment of the Government Decree (Art. 4.3 of Decree 275/2004×8). The amendment provides the option to develop facultative non-binding management plans for Natura 2000 sites, the ‘Natura 2000 maintenance plans’.

The management planning system introduced in 2008, shows changes in two key features compared to the pre-existing instrument for nationally protected areas. Most importantly, the authoritative force of the instrument differs, since the focus is on voluntary conservation measures and the plan is not legally binding. Furthermore, the governance design of the instrument differs, as the only requirement is a consultation with involved actors and there is no procedure for approval. Its action content did not alter much, although it is focussed on Natura 2000 species and habitats and not on nationally protected features (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2009).

4.3.2. Changes in the national policy arrangement

The end of the Communist era, followed by the establishment of the Hungarian Republic (1989) and the joining of the EU (2004) brought many consecutive changes in all four dimensions of the national policy arrangement. There were contrary trends in the rules regarding conservation areas. After an initial period of reduced government control, due to the restitution of land to private owners, strict rules for conservation areas were introduced in 1995. Act XCIII on ‘the restoration of the level of protection of protected natural areas’ was passed, which avoided unrestricted privatisation of land within conservation areas. If land was reinstituted, the private owner had to abide by the restrictions set forth by government. Furthermore, an active policy of expropriation was introduced on land which had already been reinstated. In 1996, the Nature Conservation Act, which replaced several acts and regulations from the communist era, stipulated which activities were prohibited or required approval in conservation areas. The transposition of the Habitats and Birds Directives into Hungarian law in 2004 led to a dual system. The established rules for national conservation areas were upheld, but less strict rules were introduced for Natura 2000 areas which were not protected as national conservation areas. Adaptation pressure was moderate as it only applied to areas not previously protected under national legislation.

The major change in the actor dimension is the emerging of coalitions between the government and environmental NGO's and, to a lesser extent, between government and private landowners. The end of communism led to the emergence of several conservation NGOs that actively contribute to both policy development and implementation (Börzel and Buzogány Citation2010; Cent, Mertens, and Niedzialkowski Citation2013). At the same time, two contradicting processes occurred. The active expropriation process of national conservation areas led to a decrease in private ownership in these areas, from 42% to 24% between 1990 and 2007 (Ministry of Environment and Water, undated). At the same time, Natura 2000 designation, led to a contrary movement, increasing the number of private owners within the Natura 2000 network.

In the discourse dimension, there was a shift towards a less state-dominated mode of governance of nature conservation policy: ‘In Natura 2000 areas, it is more about co-operation then about [strict] conservation…. Especially the projects and payment schemes provide the opportunity to really communicate nature conservation positively to stakeholders and not just the restrictions’.Footnote6 But, in practice, private land ownership in nature conservation areas remained problematic. Due to the communist legacy, many landowners are averse to governmental interference. In respect to the type of nature conservation measures needed, no major shift in views on Hungarian nature conservation occurred. In general, ideas on the importance of conserving nature through undertaking conservation measures and avoiding damaging activities were already well developed in the early years of the Hungarian republic.

The main change in the resource dimension between the period prior and after joining the EU was an increase in funding for nature conservation from EU sources. Prior to the pre-accession period, no subsidy system was available to encourage biodiversity protection by private owners. In the pre-accession period, funding did increase as LIFE funding was available from the EU. After accession there was a sharp increase in funding for nature conservation from EU funds, both for governmental organisations (through LIFE projects and structural funds) and private landowners (through EU agri-environmental subsidies). The new funding sources are facilitating the interaction with private landowners.

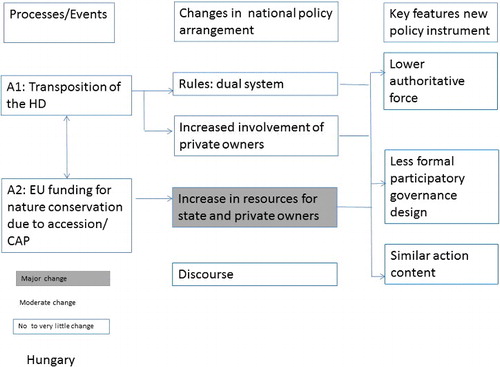

4.3.3. Relationship between changes in the policy arrangement and the management instrument

The description of the national policy arrangement shows that key features of the instrument changed due to an increase of private owner involvement combined with an increase of resources for nature conservation. Our analysis shows that both the transposition of the Directive and an increase in funding for nature conservation due to joining the EU were contributing causes. Prior to EU accession, the government's policy focussed on reducing private ownership of nationally protected areas. Natura 2000 led to a contrary shift in ownership conditions and instigated the development of the maintenance plans. It is not likely that an increase in private ownership of protected areas would have taken place solely due to domestic influences. The increased budget for nature conservation in Hungary from LIFE funds, Structural Funds and the Common Agricultural Policy and the possibilities these Funds offered for state as well as private landowners were the result of overall EU Accession. Separating the influence of the Habitats Directive from those of overall process of joining the EU is complex as the two processes are related. Therefore, in the case of Hungary, although the Habitats Directive was one of the necessary conditions for the emergence of the new management planning instrument, it might be better to talk about a conjunction, namely, a process in which interrelated conditions, in this case both emerging from the process of joining the EU, occurred and were both necessary conditions and together sufficient (see ).

4.4. The Netherlands

4.4.1. Change in management planning instrument

Until 2004, the system for management planning for privately owned conservation areas in the Netherlands was facultative (Art 14.1 Natuur beschermingswet 1967). For legally designated conservation areas, the government could prepare a management plan in consultation with the owner. The conservation measures to be taken (‘action content’) incorporated in the plan were based on mutual agreement. For conservation areas owned by the government and Dutch nature conservation NGO management planning has been standard practice since the 1960s (Buis, Verkaik, and Dijs Citation1999). The Nature Conservation Act was revised in 1998 in order to transpose the Habitats Directive into Dutch law. The facultative system was maintained in the revised act.

In 2004, due to an EC notification on incomplete transposition, the Nature Conservation Act was revised. At that time, a statutory requirement for management plans for Natura 2000 sites was introduced, following an amendment supported by several political parties (Art 19a). Also the most influential governmental and non-governmental actorsFootnote7 from the business and nature conservation sectors supported such a plan. Since the majority of the legally protected conservation sites were part of the Natura 2000 network, the pre-existing facultative system was almost completely replaced.Footnote8

The management planning system introduced in 2004 shows changes in all three key features compared to the pre-existing instrument. Its action content was altered: the instrument would specify both ‘conservation measures’ and stipulate land use activities that are not allowed or require permission. Its authoritative force also changed: the plan can now be enforced by the government. Lastly, the governance design of the instrument changed. The plan can, in contrast to the past arrangement, be developed and approved without the consent of the owner. Additionally, an elaborate consultation process with other stakeholders is required for private as well as state owned areas.

4.4.2. Changes in national policy arrangement

The major change in the rules dimension observed between the two periods is a shift from a consensual approach for conservation towards a regulatory approach. This was primarily due to the Habitats Directive. In 1989, a proactive non-binding strategy for nature conservation was introduced in the Netherlands, called the National Ecological Network (Bogaert and Gersie Citation2006). Protection of areas through law was limited. The consecutive revisions of the Nature Protection Act in 1998 and 2004 in order to transpose the Habitats Directive, driven by the EC notification, led to a much more regulatory approach for areas managed for nature in the Netherlands. The adaptation pressure was high as the EU requirements were not in line with the existing laws. The new rules were enforced because several plans and projects were contested in court. This led to an increase in the application of legal processes to Dutch nature conservation practice (Beunen, Van Assche, and Duineveld Citation2013).

In the discourse dimension, the dominant ecological discourse was supplemented by more people oriented discourses. The dominant Dutch nature conservation approach had been based on ecological insights to reconnect the fragmented natural areas of the Netherlands and increase the area managed for nature on a consensual basis. Although this approach was initially successful, it met with increasing resistance in the middle of the 1990s, mainly from the agricultural sector (Bogaert and Gersie Citation2006). From 2000 onwards, the Dutch nature conservation policy was increasingly criticised as being too technocratic, too restrictive, too detached from the average citizen (Buijs, Mattijssen, and Arts Citation2014) and support for critical discourses, which were already present grew (Beunen, Van Assche, and Duineveld Citation2013). In particular, they reflected the need to acknowledge the interests and views of local stakeholders, as well as the need to limit the negative economic effects to nature policy. “Both directives have given rise to concerns in different sectors.….” (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, Citation2003, 8). A few of them express their concerns with statements as The Netherlands locked down? (‘Nederland op slot’?).Footnote9

The change in the rules dimension also led to a change in the constellation of actors. In the beginning of the 1990s, nature conservation was dominated by the national government, the State Forest Service and several non-governmental nature conservation organisations and, to a lesser extent, by farmers (Bogaert and Gersie Citation2006). From 2000 onwards, other actors from economic sectors such as transport, building and recreation became involved in nature conservation policy, mostly opposing the restrictions laid down by the New Conservation Act.

In respect to the resources dimension, no clear differences between the periods can be distinguished except for a steady increase in the resources allocated for nature conservation between 1990 and 2004. The increase was not related to the need to undertake conservation measures for Natura 2000 sites, but due to an extension of the National Ecological Network (CBS, CBS, PBL, and Wageningen UR Citation2012).

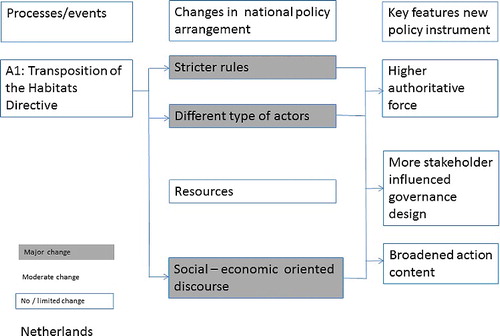

4.4.3. Relationship between changes in the policy arrangement and the management instrument

In the Netherlands, evidence strongly indicates that the major changes that have taken place in the Dutch national policy arrangement are due to the requirements of the Habitats Directive. The shift towards a more regulatory approach in relation to nature conservation originated from the rules laid down in the Habitats Directive and their enforcement by the EC. It is highly unlikely that the shift towards a more compulsory regime would have occurred because of autonomous domestic developments given the consensual approach of Dutch nature conservation prior to 1992. During the period 1992–2004, there seem to have been no other domestic events in the nature policy sector that led to a more regulatory approach. Moreover, the change in the rules dimension instigated the changes in the actor as well as discourse dimension. The requirement to legally designate the areas and assess the impacts of plans and projects changed the number and types of actors involved. It also built more support for alternative discourses. The change in the key features of the management planning instrument itself formalised the changes that had taken place in the national policy arrangement (see ).

5. Discussion

Our narrative shows that the domestic impact of the Habitats Directive on the national policy arrangement in the three countries varied. In the Netherlands, major changes occurred due to the Directive, in Finland and Hungary only moderate changes occurred (see Figures –, and ).

Our findings indicate that we can distinguish three different situations in which policy instruments might develop under the influence of an EU Directive in the absence of an explicit requirement to do so. The first of these are situations, such as in the Netherlands, in which adaptation pressure is high because the EU requirements are not in line with existing administrative traditions and the existing sectoral policy (Knill Citation2001). Once the policy is implemented this will inevitably lead to major changes in several dimensions of the national policy arrangement (see ). This, in turn, will create high adaptation pressure to modify the existing instruments. New instruments that are introduced will clearly reflect EU influence. In these situations, the EU Directive is most likely a necessary and sufficient condition for policy instrument development (cause).

In other situations, such as Finland and Hungary, the EU requirements create low to moderate adaptation pressure resulting in moderate change to the national policy arrangements. The EU Directive is most likely a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for policy instrument development. Other necessary conditions are required. Such as socio-political trends or developments within adjacent policy fields (Arnouts Citation2010) (see ). In Finland, the already present socio-political trends of increased participation and changing discourse about management, among other things due to developments in the adjacent policy field of forestry together with the Habitats Directive, created the necessary and sufficient conditions for a new policy instrument (see ). In Hungary, the additional resources due to EU accession, together with the Habitats Directive, created the sufficient conditions to enable the introduction of a new policy instrument. In situations of low to moderate adaptation pressure, emerging instruments will reflect the requirement of the EU Directive as well as the other necessary conditions. If these other necessary conditions are already set in motion prior to the introduction of the EU Directive the Directive acts as a catalyst, if they are interrelated or occur at the same time the situation is better described as conjunction.

Our findings underline the importance of considering the interaction of EU policy with various aspects of the domestic situation, as suggested by several other Europeanisation studies (Bailey Citation2002; Knill Citation2001; Lenschow, Liefferink, and Veenman Citation2005). They also show the need to review other explanations for change of the domestic situation, such as socio-political trends or developments in adjacent policy fields (Arnouts Citation2010).

Apparently, the EU does not only influence policy instrument choice by Member States through direct institutional compliance by requiring that a specific instrument is introduced. Indirect influence on the national policy arrangement is also likely to initiate or affect instrument change. Our analysis suggest that the governance design of existing instruments may need to be adapted if the EU influences the actors or discourse dimensions; for instance, if the responsibility for action shifts to new actors who in exchange for their co-operation expect more influence on the development of the instrument. The authoritative force of an instrument might require adaption if the EU influences the rules or resources dimension. Stricter rules require a greater authoritative force, less strict rules allow for a more voluntary approach. If resources increase, a more incentive based voluntary approach can be feasible; if resources decrease a more regulatory approach might be required. The action content of instruments might also need adaptation due to the EU influences on the discourse or rules dimension (see ).

In instrument choice literature, explanations of why governments change their instruments are manifold; learning, changing discourses, struggles between involved actors, national policy styles and policy networks (Bressers and O'Toole Jr Citation1998; Hall Citation1993; Dolowitz and Marsh Citation2000; Sabatier Citation1998; Howlett Citation2009). Our paper reveals that all of these played a role in the decision to introduce a new instrument, for instance, learning (Hungary), struggles between actors (Netherlands, Finland), changing discourses (Netherlands, Finland), national policy styles (Hungary) and changing policy networks (Hungary, Netherlands, Finland).

6. Conclusions

This paper began with the question of how to discern the impact of an EU Directive on policy instrument choice. We were surprised by the behaviour of Member States, which introduced new instruments in order to address the management of Natura 2000 sites without a legal requirement to do so. Despite the intricacies of causal analysis, this paper shows that EU Directives, even in the absence of a requirement for a particular policy instrument, can instigate policy instrument development. In all three of the cases reviewed a nested causal relationship could be determined between the emergence of the new instrument and the Habitats Directive. But the character of the newly emerged instruments shows that the relative significance of the influence of the Habitats Directive varies. We ascribe this variation to the intermingling of the Directive, national domestic developments and the EU Accession process which have led to a change in the rules, discourse, actors and resources of the national policy arrangement.

Overall, this paper shows why it has proven to be difficult to draw generic conclusions about the influence of EU policy on policy instrument choice by individual Member States. In the case of non-binding requirements, the influence of a specific EU Directive is diffused by the ongoing domestic processes. For EU and national policy makers, this makes it a very complex task to carry out ex ante assessments of the impact of a new Directive on the national policy instrumentation. This is particularly so because not only legal and administrative effects but also effects on actor constellations, discourse and resources need to be assessed. Nevertheless, the paper provides insights into the type of situations in which new policy instruments might emerge under the influence of EU policy in cases in which no explicit legal obligations exist. In the first instance, instrument development can be expected in situations in which the Directive causes high adaptation pressure and instigates major change in the national policy arrangement of the Member State (cause). The resulting instruments primarily reflect EU policy requirements. Although new instruments are not required, it will be very likely that they will be developed. Therefore, an ex ante evaluation should review the benefits and costs of developing new instruments. New instruments may, however, also emerge in situations in which the Directive itself exerts medium to low adaptation pressure. While this results in moderate changes in the particular policy field, the Directive strengthens ongoing developments in the policy field (catalyst) or coincides with developments in related policy fields (conjunction). However, given the many uncertainties involved in such situations, considering instrument development in an ex ante evaluation is not very likely to be helpful.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those in the Netherlands, Hungary and Finland who were kind enough to spare the time for an interview. In particular, we would like to thank András Schmidt and Mervi Heinonen who commented on the draft version of this paper. This research was partly supported by the strategic research programme KBIV (KB-14) “Sustainable spatial development of ecosystems, landscapes, seas and regions” which is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The following countries introduced new management planning instruments. Members prior to 1992: the Netherlands, France, Denmark, Ireland, Greece.

Member after 1992: Finland, Sweden, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland.

2. Habitat types and species for which sites need to be designated are listed in Annex I and II.

3. Since 2014, this plan can also be a Natura 2000 Site Condition Assessment.

4. The formal rules for management of conservation areas vary, depending on the Act establishing the area. Although at least 5 Acts stipulate the rules, only the Nature Conservation Act was revised in the reviewed period, this section limits itself to discussing this revision.

5. Finnish Ministerial Official, 2013.

6. Hungarian Ministerial Official, 2013.

7. IPO, VNG, VNO-NVW, MKB, State Forest Service, Vogelbescherming, Natuurmonumenten and Stichting Natuur en Milieu.

8. The facultative system was maintained for the 64 conservation areas (3422 hectares) Broekmeijer M E A, Bijlsma R J, Nieuwenhuizen W, Citation2011, “Beschermde natuurmonumenten: stand van zaken en toekomstige bescherming” (Alterra, Wageningen).

9. Statements made during parliamentary debate in 2004 (https://www.overheid.nl/).

References

- Arnouts, R. 2010. Regional Nature Governance in the Netherlands: Four Decades of Governance Modes and Shifts in the Utrechtse Heuvelrug and Midden-Brabant. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Arts, B., and P. Leroy. 2006. Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bailey, I. 2002. “National Adaptation to European Integration: Institutional Vetoes and the Goodness- of- Fit”. Journal of European Public Policy 9: 791–811.

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., and R.C. Rist. 1998. Carrots, Sticks and Sermons: Policy Instruments and their Evaluation. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Bennett, G., and S. Ligthart. 2001. “The Implementation of International Nature Conservation Agreements in Europe: The Case of the Netherlands.” European Environment 11: 140–150.

- Beunen, R., K. Van Assche, and M. Duineveld. 2013. “Performing Failure in Conservation Policy: The Implementation of European Union Directives in the Netherlands.” Land Use Policy 31: 280–288.

- Bogaert, D., and A. Gersie. 2006. “High Noon in the Low Countries: Recent Nature Policy Dynamics in the Netherlands and in Flanders.” In Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance, edited by B. Arts and D. Liefferink, 115–138. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Börzel, T., and A. Buzogány. 2010. “Environmental Organisations and the Europeanisation of Public Policy in Central and Eastern Europe: The Case of Biodiversity Governance.” Environmental Politics 19: 708–735.

- Bouwma, I., D. Liefferink, R. van Apeldoorn, and B. Arts. 2016. “Following Old Paths or Shaping New Ones in Natura 2000 Implementation? Mapping Path Dependency in Instrument Choice.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 18 (2) 214–233.

- Bressers, H.T.A., and L.J. O'Toole Jr. 1998. “The Selection of Policy Instruments: A Network-Based Perspective.” Journal of Public Policy 18: 213–239.

- Broekmeijer, M.E.A., R.J. Bijlsma, and W. Nieuwenhuizen. 2011. Beschermde Natuurmonumenten: Stand Van Zaken en Toekomstige Bescherming. Wageningen: Alterra.

- Buijs, A., T. Mattijssen, and B. Arts. 2014. “‘The Man, the Administration and the Counter-Discourse’: An Analysis of the Sudden Turn in Dutch Nature Conservation Policy.” Land Use Policy 38: 676–684.

- Buis, J., J.P. Verkaik, and F. Dijs. 1999. Staatsbosbeheer 100 Jaar: Werken Aan Groen Nederland. Utrecht: Matrijs.

- Bulmer, S., and S. Padgett. 2005. “Policy Transfer in the European Union: An Institutionalist Perspective.” British Journal of Political Science 35: 103–126.

- CBS, PBL, and Wageningen UR. 2012. “Uitgaven Beheer Ecologische Hoofdstructuur (EHS) 1990- 2009, Indicator 1469, versie 01, 18 Januari 2012.” http://www.clo.nl/indicatoren/nl1469-uitgaven-aan-natuur-beheer-ecologische-hoofdstructuur?ond=20884

- Cent, J., C. Mertens, and K. Niedzialkowski. 2013. “Roles and Impacts of Non-Governmental Organizations in Natura 2000 Implementation in Hungary and Poland.” Environmental Conservation 40: 119–128.

- Dolowitz, D.P., and D. Marsh. 2000. “Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy‐Making.” Governance 13: 5–23.

- Eidsvik, H.K., and B.H. Bibelriether. 1994. Finland's Protected Areas. A Technical Assessment. Vandaa: Metsähallitu.

- Gerring, J. 2005. “Causation: A Unified Framework for the Social Sciences.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 17 (2): 163–98.

- Goetz, K., and K. Dyson. 2003. Germany, Europe, and the Politics of Constraint. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Habitats Directive. 1992. Council Directive 92/42/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. Official Journal of the European Communities. L 206 P 0007-0050.

- Hall, P.A. 1993. “Policy Paradigms, Social-Learning, and the State – the Case of Economic Policy-Making in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25: 275–296.

- Haverland, M. 2005. “Does the EU Cause Domestic Developments? The Problem of Case Selection in Europeanization Research.” European Integration Online Papers 9. http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2005-002a.htm

- Heinonen, M. 2007. State of the Parks in Finland. Helsinki: Metsähalitus.

- Hille, P., and C. Knill. 2006. “‘It's the Bureaucracy, Stupid’: The Implementation of the Acquis Communautaire in EU Candidate Countries, 1999-2003.” European Union Politics 7: 531–552.

- Hockings, M. 2003. “Systems for Assessing the Effectiveness of Management in Protected Areas.” BioScience 53: 823–832.

- Howlett, M. 2009. “Governance Modes, Policy Regimes and Operational Plans: A Multi-Level Nested Model of Policy Instrument Choice and Policy Design.” Policy Sciences 42: 73–89.

- Johnson, B.R., A. Duncan, and L. Oldenkamp. 1998. Managing Nature in the CEEC: Strategies for Developing and Supporting Nature Conservation Management in the Central and Eastern European Countries: Volume 2: Country Reports. Wimereux: Eurosite.

- Jordan, A., R. Wurzel, A.R. Zito, and L. Bruckner. 2003. “European Governance and the Transfer of ‘New' Environmental Policy Instruments (NEPIs) in the European Union.” Public Administration 81: 555–574.

- Kjaer, A.M. 2004. Governance. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Knill, C. 2001. The Europeanization of National Administrative Traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knill, C., and D. Lehmkuhl. 2002. “The National Impact of European Union Regulatory Policy: Three Europeanization Mechanisms.” European Journal of Political Research 41: 255–280.

- Kuuluvainen, T., K. Aapala, P. Ahlroth, M. Kuusinen, T. Lindholm, T. Sallantaus, J. Siitonen, and H. Tukia. 2002. “Principles of Ecological Restoration of Boreal Forested Ecosystems: Finland as an Example.” Silva Fennica 36: 409–422.

- Lenschow, A., D. Liefferink, and S., Veenman. 2005. “When the Birds Sing: A Framework for Analysing Domestic Factors Behind Policy Convergence” Journal of European Public Policy 12: 797–816.

- Liefferink, D. 2006. “The Dynamics of Policy Arrangements: Turning Round the Tetrahedron.” In Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance, edited by B. Arts, P. Leroy, 45–67. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Loikkanen, T., T. Simojoki, and P. Wallenius. 1999. Participatory Approach to Natural Resource Management: A Guidebook. Vantaa. Vantaa: Metsahallitus Forest and Park Service.

- Mahoney, J. 1999. “Nominal, Ordinal, and Narrative Appraisal in Macrocausal Analysis 1.” American Journal of Sociology 104: 1154–1196.

- Mahoney, J. 2000. “Strategies of Causal Inference in Small-N Analysis.” Sociological Methods and Research 28: 387–424.

- Mastenbroek, E. 2005. “EU Compliance: Still a ‘Black Hole'?” Journal of European Public Policy 12: 1103–1120.

- Ministry of Agriculture. 2009. New Hungary Rural Development Programme. Budapest: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Ministry of Environment and Water, undated. Facts and Figures on Protected Sites in Hungary. Budapest: Ministry of Environment and Water.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2002. Natura 2000 – Alueiden Hoito ja Käyttö Työryhmän Mietintö. Suomen ympäristö 597. Helsinki: Suomen Ympäristö.

- Mose, I., and N. Weixlbaumer. 2007. A New Paradigm for Protected Areas in Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- National Audit Office of Finland. 2007. The Preparation of the Natura 2000 Network. Helsinki: National Audit Office of Finland.

- Paloniemi, R., M. Koivulehto, E. Primmer, and J. Similä. 2012. Finnish National Report: National Regulatory Model of Finnish Biodiversity Policy. Helsinki: Environmental Policy Centre, Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE).

- Pertulla, M. 2006. Suomen Kansallispuistojärjestelmän Kehittyminen 1960-1990 – Luvuilla ja U.S. National Park Servicen Vaikutukset Puistojen Hoitoon. Helsinki: Metsähallitus.

- Primmer, E., R. Paloniemi, J. Similä, and D.N. Barton. 2013. “Evolution in Finland's Forest Biodiversity Conservation Payments and the Institutional Constraints on Establishing New Policy.” Society & Natural Resources 26: 1137–1154.

- Rhodes, R.A.W. 1997. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Sabatier, P.A. 1998. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Revisions and Relevance for Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 5: 98–130.

- Salamon, L.M. 2002. The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Steinberg, P.F. 2007. “Causal Assessment in Small‐N Policy Studies.” Policy Studies Journal 35: 181–204.

- Treib, O. 2014. “Implementing and Complying With EU Governance Outputs.” Living Reviews in European Governance 9. http://www.livingreviews.org/lreg-2006-1.

- Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal. 2003. Wijziging van de Natuurbeschermingswet 1998 in verband met Europeesrechtelijke verplichtingen. 28 171. 49 Verslag van een Notaoverleg. The Hague: Sdu Publishers.

- Vedung, E. 1998. “Policy Instruments: Typologies and Theories.” In Carrots, Stick and Sermons, edited by M.L. Bemelmans-Videc, R.C. Rist, E. Vedung, 21–59. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.