Abstract

This study takes the stagnation in the transfer of knowledge about strategic delta planning as a starting point and identifies the interplay of constraining factors. We conclude that the way the process of policy transfer is executed is crucial. The Dutch government aims to transfer the Dutch approach to delta planning (labelled ‘the Dutch Delta Approach’) to other – often developing – countries. However, policy transfer is a complex process that depends on a variety of factors. Deadlocks can occur when the transferred knowledge and the corresponding policy ideas are neither adopted nor rejected. Taking the impasse in the transfer process in the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development project in Jakarta as a case study, we demonstrate that fundamental policy change is needed to adopt strategic delta planning in Jakarta and present three interrelated explanations, related to the policy transfer process, that illustrate why this change is not yet observed.

1. Introduction

Deltas around the world have to deal with the consequences of climate change. In 2010, the Dutch Delta Programme was initiated to enhance climate robustness in the Netherlands (Rijksoverheid Citation2010). This approach forms an example of the ‘adaptive’ or ‘strategic’ delta management currently advocated in global flood risk communities (Klijn et al. Citation2015). The Dutch government realised the export potential of this ‘Dutch approach’ (Rijksoverheid Citation2014) and strategic plans became an export product (Zegwaard Citation2016) serving two purposes: aiding other countries to adapt their delta planning to climate change and generating business opportunities for the Dutch water sector (Rijksoverheid Citation2016). Examples include the formulation of delta plans for Vietnam and Bangladesh (Zegwaard Citation2016), and strategic master plans for cities such as Beira (Mozambique) and Jakarta (Indonesia; NWP Citation2013). These activities are captured in the umbrella term ‘the Dutch Delta Approach’ (DDA) and can be seen as a form of policy transfer. Policy transfer is an action-oriented intentional activity (Evans and Davies Citation1999) where “knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions, etc. in one time and/or place” is used to develop policies in another time or place (Dolowitz and Marsh Citation1996, 334). In the case of the DDA, this means that knowledge about delta planning and management in the Netherlands is considered a policy model that is transferred to the selected focus deltas.

However, the various attempts at transferring the DDA show varying results. Most studies point to stagnation after decision-making or implementation failure at the end of the day. However, impasses during the policy transfer process can also easily emerge when the actors engaged in policymaking no longer agree on core problems and solutions (Biesbroek, Termeer, Klostermann, and Kabat Citation2014). An illustrative case can be found in Jakarta, Indonesia. In the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) project, a consortium of Dutch private-sector actors prepares a strategy to reduce the city’s vulnerability to flooding (Deltares Citation2016). These actors are transfer agents that “facilitate the exchange between a number of polities.” (Stone Citation2004, 549). However, they experience several challenges in translating the DDA to the new environment, such as a different institutional context and disagreement over problem causes. We observe that the recipient Indonesian policymakers remain reluctant to utilise the transferred ideas for a strategic plan as a basis for political decision-making. As such, an impasse emerged.

The impasse that occurred in the transfer of the DDA to Jakarta is a snapshot of an ongoing process and could, in theory, resolve before the NCICD2 phase ends. We aim to explain the emergence of the impasse, thereby taking into account the interrelatedness of factors at play in transfer processes (e.g. Stone Citation2016) and the dynamic nature of the interaction where the impasse occurs (Biesbroek et al. Citation2014). The main research question of this paper, therefore, is: how can we explain the existing impasse in transferring the DDA to Jakarta, by adopting a policy transfer perspective?

In Section 2, we will present a framework where we conceptualise the DDA, the kind of impasse that has occurred and factors influencing the policy transfer process. The core assumption is that the impasse, at least, is related to the organisation of the policy transfer process. In Section 3, we describe our methodological approach. We introduce the case in Section 4, before presenting potential explanations for the impasse in Jakarta in Section 5. In Section 5, we derive three (interrelated) explanations for the impasse.

2. Theoretical framework

To explain how the impasse came into being in Jakarta, we need to look at factors that constrained the policy transfer process. The focus in policy transfer research is shifting from describing policy transfer processes (who transfers what from where) to understanding policy transfer and adoption (Dolowitz and Marsh Citation1996). Over the years, numerous factors have been identified. In this study, we will look at the interplay of factors and their influence on the stagnation of the transfer process. In this theoretical framework, we will first explain what is being transferred and elaborate on the concept of policy transfer, before introducing our conceptual model of factors.

2.1. What is transferred?

When mobilising the ‘DDA’ for international export, the original policy ideas, programmes and instruments are translated into a policy model (Minkman, Van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2018). There is no single definition of this policy model. “When looking more closely at the precise contents of Dutch delta knowledge, it appears difficult to precisely pin down what characterizes it. […] When travelling to other countries, Dutch Delta knowledge also seems to come in many shapes and forms” (Zwarteveen et al. Citation2017, 7).

In the Netherlands, the delta approach materialised in policy instruments, such as a Delta Programme and establishing a Delta Fund (Alphen Citation2016). The Delta Programme combines measures such as new flood risk norms, adaptation pathways and strategies to ensure freshwater supply, but also embraces collaboration, integrated and long-term oriented planning and adaptive delta management (Alphen Citation2016), thereby combining ‘hard’ infrastructure measures and ‘soft’ governance (Wesselink Citation2016). Besides the Delta Programme, other policy programmes characterise how the emphasis in Dutch water management transformed from total flood prevention to risk assessments and adaptive planning (Van Buuren, Ellen, and Warner Citation2016) as the result of a fundamental change in Dutch water management (Van Buuren et al. Citation2018; Verduijn, Meijerink, and Leroy Citation2012).

We can define the DDA in the transfer of underlying – more abstract – concepts. Dutch experts fuel projects abroad with substantial expertise about delta technology, but also with typical building blocks derived from the DDA: about flood risk management in general, adaptive and integrated planning, and participation (Rijksoverheid Citation2014). For the purpose of this study, we will consider the DDA to be a policy model consisting of a set of structural and non-structural measures that are used to ensure adaptive, integrated and long-term oriented delta planning. Core values are flexibility, sustainability and solidarity (Slob and Bloemen Citation2014), but collaboration between state actors and non-state stakeholders is also emphasised (Rijksoverheid Citation2014).

2.2. Conceptualising the policy transfer process and impasses

The transfer in Jakarta took off in 2007 and thereby fits the description of policy transfer as a dynamic, long-term process (Dussauge-Laguna Citation2012; Wood Citation2015b).

2.2.1. Policy transfer as a social process of change

We conceptualise policy transfer as a social or interactional process (Khirfan, Momani, and Jaffer Citation2013; Vinke-de Kruijf, Augustijn, and Bressers Citation2012), whereby knowledge is exchanged at the individual level and is used in different degrees at the organisational level (Jinnah and Lindsay Citation2016; Khirfan, Momani, and Jaffer Citation2013; Van de Velde Citation2013).

Policy transfer always requires changing existing policy norms, goals, assumptions and instruments. This required change can be viewed as a form of policy learning (Dunlop Citation2009). Depending on the required change, a different degree of policy learning is needed. Although terms vary, authors generally distinguish between three levels of learning: instrumental or single-loop learning, double-loop learning and triple-loop learning. The first level focusses on instrumental learning, whereby the action strategy is questioned and new policy instruments are considered (O’Donovan Citation2017). Modest organisational adjustment occurs, but underlying goals and values remain intact (Bennett and Howlett Citation1992). The second level concerns learning about the problem and reassessing existing policy goals (May Citation1992). At the third level of learning, rethinking of underlying ideas and core values occurs (Hall Citation1993; Bennett and Howlett Citation1992). Such a fundamental change requires shifts in dominant political ideas and can be considered a change of paradigm (May Citation1992; Pahl-Wostl Citation2009).

2.2.2. Adoption, adaptation, reluctance and rejection as ‘successful’ transfer

Since we conceptualise policy transfer in the light of knowledge exchange, we are not interested in comparing Dutch and Indonesian flood policies and checking a list of similarities before and after the knowledge exchange. We consider the policy transfer process to be ‘successful’ when the decision-makers in the receiving context actively take a decision regarding the transferred ideas, because such a decision implies that they took notice of the transferred knowledge. As a result, policy transfer is ‘successful’ and it leads to adoption (i.e. local practices becomes aligned with imported ideas) or forms of adaptation (i.e. the imported ideas are altered to fit local practice; Heiduk Citation2016; Rose Citation1991). Moreover, this means that resistance to and rejection of, external ideas are also potential outcomes (Heiduk Citation2016). Resistance occurs when there are gradual changes in local practice (i.e. the majority of practices are not altered) and rejection implies that local practice is not altered by the imported ideas.

2.2.3. Impasses

We speak of an impasse, when the actors engaged in policymaking no longer agree on core problems and solutions (Biesbroek et al. Citation2014) and the decision-making process stagnates at times, or needs an extra iteration (Wood Citation2015b). Impasses can occur in every policy process, but the diffusion of global ideas and norms, such as adaptive or strategic planning in flood management, is particularly vulnerable to impasses. These norms cannot be effectively transferred when they collide with domestic interests or when implementation is costly, ill-suited or perceived unnecessary (Eccleston and Woodward Citation2014). This holds especially for a transfer from a developed country to developing countries (Rahman, Naz, and Nand Citation2013), like in our case with transfer from the Netherlands to Indonesia. A dominant role of donor countries in setting the agenda for the transfer process could result in a lack of ownership by the receiver (Ostrom and Gibson Citation2001) or too strong a focus on resource-intense knowledge and technology (Rahman, Naz, and Nand Citation2013; Stead, De Jong, and Reinholde Citation2008).

2.3. Factors constraining the policy transfer process

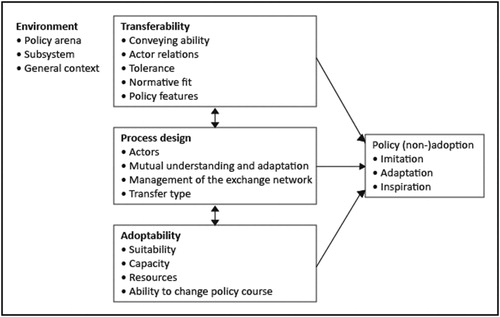

This brings us to discussing what may cause problems with policy transfer. In this study, we build on a conceptual model of constraining and facilitating factors that we developed in previous work (Minkman, Van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2018). In this model, (see ) we clustered the factors around four elements of the transfer process: the broader environment or context in which the policy transfer takes place, transferability (i.e. how suited is the policy for transfer?), adoptability (i.e. how suitable is the transferred knowledge for adoption?) and process design (i.e. how is the transfer of knowledge organised?). All these factors are relevant to explain the rise of impasses in transfer processes.

2.3.1. Environment

First, the importance of the wider context in which transfer takes place has been frequently acknowledged (e.g. Warren Citation2017). Hence, differences between the institutional, social-economic, ideological, political and institutional contexts (e.g. Benson and Jordan Citation2011; Evans and Davies Citation1999; Mukhtarov et al. Citation2015; Vinke-de Kruijf and Pahl-Wostl Citation2016) of the Netherlands and Indonesia might constrain the transfer. The environment affects policy transfer at three different levels (Minkman, Van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2018). The political climate can open or close a window of opportunity (Busch, Jörgens, and Tews Citation2005). As such, this policy arena directly shapes the space of transfer agents. The subsystem covers the institutional contexts and potentially comprises policy alternatives (Allouche Citation2016).

2.3.2. Transferability

Second, there are factors related to the transferability of the policy. The sender can be disqualified as a legitimate source for policy transfer when the actor from where the policy originates, or the transferred policy itself, has a flawed reputation (Onursal-Beşgül Citation2016). Alternatively, compliance costs to adopt the policy can be too high for the adopting actor (Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013). The programmatic nature of the transferred policy thereby plays a role in its transferability and adoptability (Benson and Jordan Citation2011). Policies with a high level of uniqueness are more difficult to transfer, for example, when solutions are tailored to local biophysical circumstances (Michaels and De Loë Citation2010). As a result, when policy models are transferred they should be “flexible enough to be adapted to a new environment, yet fixed enough in key areas to maintain program integrity” (Kerlin Citation2009, 485). Differences in ideological perspective may end in incompatibility of the transferred ideas with the dominant values and ideas of the recipient (Chapman and Greenaway Citation2006; Dolowitz and Marsh Citation2000).

Disruptions in the policy transfer process may also emerge on the demand side (Benson and Jordan Citation2011). Especially in cases of policy export (i.e. when an actor is pro-actively spreading its policy; Stone Citation1999), the targeted audience may be unwilling to move beyond the status quo. Unexpected events such as floods can trigger demand (Hall Citation1993), but demand can also be artificially created. Artificial demand can be created by coercion, but also declaring the policy transfer a condition for something else, such as a loan (Larmour Citation2002). However, coercively created demand struggles with sustainability, because actors lack ownership (Ostrom and Gibson Citation2001) or the resources (Bennett et al. Citation2015) to adopt and implement the policy.

2.3.3. Adoptability

Third, adoptability-related constraints may hamper adoption. One important aspect is the scale of the required change. Adoption of the transferred policy requires a form of policy change. The more far-reaching the necessary changes are, the more difficult they are to realise. Apart from the scale of the change, the presence or absence of local institutions might conflict with adoption (Xu Citation2005). Also, the adopting government should have the capacity to evaluate the transferred ideas, to ensure that the policy contributes to policy objectives and matches the recipient context (Fawcett and Marsh Citation2012). Path dependency may restrain policymakers from changing the policy course (Zhang Citation2012). Naturally, a lack of resources can be a major constraint for the evaluation, adoption and implementation process (Marsden et al. Citation2012).

2.3.4. Process design

Finally, the set-up of the process influences policy transfer outcomes. Most of the literature on policy transfer takes a quasi-rational, phase-based policymaking model as a starting point, thereby assuming that a suitable policy and well-organised knowledge transfer will result in adoption (James and Lodge Citation2003; Mukhtarov Citation2014). However, research into translation of policy stresses the role of actors and how they construct meaning (Freeman Citation2009; Vaughan and Rafanell Citation2012). As such, policy transfer becomes more of a social and political process. The organisational set-up is characterised by the formal and informal interactions between the actors involved in the transfer process. Ambiguity about these relations, or who can take decisions, could seriously constrain the process (Van de Velde Citation2013). It is crucial to understand the values, practices and beliefs of the other actors and, even more important, to adjust the transferred policy to these beliefs to prevent inappropriate transfers (De Jong and Bao Citation2007). Similarly, clashing actor coalitions (Bennett and Howlett Citation1992; Marsh and Mcconnell Citation2010), or the absence of key actors, may result in rejection of the transferred policy in the end, just like the absence of support from key actors, political champions (Attard and Enoch Citation2011), decision-makers (Kerlin Citation2009) or policy entrepreneurs (Milhorance de Castro Citation2014).

3. Method

We acknowledge the importance of historical events and the context for explaining the impasse. As such, we reconstruct the transfer process from 2007 (when transfer was initiated), relying on public documentation (e.g. the project website or news items), detailed case knowledge of the second author (who works as knowledge manager in NCICD) and interviews with involved actors and internal project documents (e.g. the inception report of a knowledge management project). A detailed case summary is shared in Section 4.

3.1. Inquiring individual factors

We operationalised the theoretical framework by translating the abstract factors in into interview questions. See Appendix A for an overview (online supplemental data). We supplemented this basic interview guideline with open questions (‘what else did affect the process?’) to solve the issue of overlooking factors by following this deductive approach.

The second author selected respondents from his network. His role as an ‘insider’ ensured access to respondents and detailed case information. We took two measures to include other (‘outsider’) perspectives in our data. First, we recruited five respondents outside the NCICD project from the first author’s network, using snowball sampling. At a Dutch event on NCICD, we met people who asked critical questions on the project. They connected us to their network; and three non-governmental organisation (NGO) employees and two civil servants of Jakarta’s provincial government agreed to a formal interview (see ). Second, all 21 formal interviews were held and analysed by the first author only.

Table 1. Overview of respondents.

Additional information was gathered in informal interviews, being “…the spontaneous generation of questions in a natural interaction, typically one that occurs as part of ongoing participant observation fieldwork” (Borg and Gall Citation2003, 239). The informal interviews took place during the fieldwork in Indonesia (May 2017) at practically any time and place, that is, whenever there was an opportunity to do so. This includes talking to participants of meetings at the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, and a symposium. The first author would ask what someone thought of the meeting/symposium. During such conversations, the author introduced the study and asked for a formal interview. Sometimes people agreed and an appointment was made for the formal interview. Other times they did not have time for a formal interview, but were willing to answer some ‘quick questions’. These questions were mainly used to verify (or falsify) observations or claims made by other respondents. These conversations were also used to specify topics for the formal interviews and create an in-depth understanding of the nature of interactions. An additional advantage was that we could include, in our dataset, people who were not available for a full formal interview.

3.2. Data analysis: linking factors

The first author recorded the interviews and transcribed and coded them using Atlas.ti software. We followed a deductive approach, using the factors from the theoretical framework as codes (see Appendix A [online supplemental data]). We made a summary per factor and assessed whether the factor contributed to stagnation (constraining factors) or helped to resolve disagreement (facilitating factors). A neutral assessment was given when there was no influence or a balance between constraints and facilitators. Finally, we noted ‘unclear’ when we could not define the direction of effects. We confronted respondents with anonymised claims from other respondents and used other data sources (literature, media and observations) for triangulation. When in doubt we followed the respondents’ assessment of the facilitating or constraining nature.

Finally, we looked for connectedness of factors. To give an example: the factors ‘lack of expertise to evaluate strategies’, ‘limited human resources’ and ‘complexity of the strategy’ seemed to reinforce each other. This was confirmed by quotes extracted from Atlas.ti for these factors. We will present these sets in the results (Section 5) and use them to draw the conclusions.

4. Case description

This section first sketches how transfer of the DDA is organised before introducing the problem Jakarta faces and describing subsequent phases of the Dutch–Indonesian collaboration.

4.1. Transferring the DDA

Dutch consortia of private and public organisations translate the DDA to strategic master plans worldwide (Rijksoverheid Citation2014). Currently, Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, Indonesia, Myanmar, Mozambique and Vietnam are considered ‘focus countries’ (Rijksoverheid Citation2016). The Dutch government formulates a problem description in consultation with the receiving government. Next, the Dutch government formulates an assignment in a tender and acts as the formal client of the winning Dutch consortia until the master plans are finalised. Then, the recipient government becomes responsible for implementation of the delta plan, which should create business opportunities for the Dutch water sector (WGC Citation2013). As such, transfer of the DDA is the result of an active policy of the Dutch government to apply the DDA abroad.

4.2. Policy transfer in Jakarta

Like other urban deltas (Syvitski et al. Citation2009; Wesselink Citation2016), Jakarta is suffering from rapid land subsidence and, especially North Jakarta, is sinking below sea level at staggering rates of over 10 cm/year (Bucx et al. Citation2014). The resulting flood risk is threefold: coastal, fluvial (rivers can easily flood the low-lying city) and pluvial (precipitation has nowhere to go; Abidin et al. Citation2011). Experts disagree about the cause of this subsidence. The most commonly accepted explanation blames the, often illegal, groundwater extractions in the city. Other explanations include compaction due to urban development, natural compaction and tectonic movements (Abidin et al. Citation2011). Whatever the cause of subsidence, Jakarta is sinking.

In 2007, a Kings Tide surprised Jakarta and caused severe human and economic damage. Following this flooding, the Indonesian government requested advice from the Dutch government. They initiated a process where Dutch experts would share their knowledge with Indonesian officials. This exchange evolved over time into advising on strategic planning. The process became one of policy transfer, whereby Dutch experts introduced policy norms, practices and policy objectives to the Indonesian government. These include prevention of future flooding, integration with other policy objectives (such as transportation and urban development) and keeping an eye on longer-term issues (Kops Citation2012). This transfer process has formally been divided into three phases: Jakarta Coastal Defence Strategy (JCDS), NCICD1 and NCICD2.

4.3. Phases of policy transfer

4.3.1. Before 2007

The Dutch–Indonesian history goes back until around 1600, when Dutch trading companies gained power in the Indonesian archipelago. From the nineteenth century, the Dutch government ruled the ‘Dutch East Indies’ until Indonesian independence after World War II. Despite diplomatic tensions, Dutch experts continued to transfer (water) infrastructure technology and knowledge to Indonesia (Ravesteijn and Kop Citation2008) and diplomatic relations improved in the late 1990s. In 2001, the Dutch and Indonesian governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding in which they committed to collaboration and knowledge exchange regarding water issues, in short the ‘MoU Water’ (NWP Citation2016).

4.3.2. JCDS (2007–2010)

Soon after the 2007 flooding, the Jakarta Flood Management programme was set up to develop the JCDS. This was part of the renewed MoU Water. JCDS started a decision-making process and aimed to formulate effective, feasible and sustainable strategic solutions for Jakarta’s coastal defence by mapping the joint interests of all stakeholders and developing a shared vision (Deltares Citation2016).

The JCDS identified three strategic alternatives for Jakarta (Kops Citation2012). The first alternative is to ‘do nothing’ and eventually abandon north Jakarta. This would imply resettling some 4.5 million inhabitants, which is considered infeasible (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017). The second alternative is to focus on structural measures onshore. This includes strengthening the existing sea walls and dikes. Relying on onshore measures requires stopping land subsidence by non-structural measures, such as ending (illegal) ground water extraction in the city by strict enforcement and providing alternative water supplies (Colven Citation2017). Experts believe there is limited time before this alternative ‘expires’, as it takes considerable time (10–15 years) to effectively halt subsidence. The third option is to turn Jakarta into a large polder using dikes, pumps and a large offshore reservoir. This option requires extensive spatial planning to find locations for the dikes and reservoirs. The advice of the Dutch consortium emphasises the importance of the second option, but there is a belief that this option expires soon. Instead, they focus on artificial lowering of the sea level by turning Jakarta Bay into a water retention lake.

In order to maintain momentum, the process was continued between 2011 and 2012, until the master planning phase (NCICD1) started. During this ‘bridging phase’ the abovementioned alternative strategies of JCDS were outlined and an action plan was drafted for land subsidence in cooperation with Dutch and Indonesian academic experts.

4.3.3. Master planning phase, also known as NCICD1 (2013–2015)

The JCDS report was well received. Its follow-up, the National Capital Integrated Coastal Defence Strategy (NCICD1), aimed to prepare a long-term strategy to protect Jakarta from tidal flooding. The two focal policy topics of this phase were flood management and urban development. This phase ended with the drafting of the master plan, also known as the ‘Great Garuda’, due to its shape like Garuda, the national symbol of Indonesia. The outputs of this phase can be summarised as technical feasibility studies. The Indonesian Ministry of Economic Affairs coordinated the process, while the Dutch government funds the process and acts as client for the Dutch consortium.

4.3.4. NCICD2 (2016–2019)

In 2015, the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs seemed ready to adopt the preferred alternative of NCICD1. The Dutch–Indonesian MoU Water was renewed and extended to a triparty memorandum between the Netherlands, Korea and Indonesia. These countries would collectively work on the detailed design of the preferred conceptual alternative of NCICD1. As such, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing (PUPR) took over the coordinating role.

The Indonesian president Joko Widodo (‘Jokowi’) did not approve the master plan, because he believed it failed to address the implementation of short-term flood measures, the (negative) impact on the livelihood of coastal communities and synchronisation with ongoing programmes for upstream measures, water quality and piped water supply. In 2016, he demanded a revision of the master plan with more attention to these issues. This meant that the master plan had to be revised and the process of drafting a strategy was repeated. Hence, the transferred ideas were rejected at first, but the transfer continued in a second iteration.

The president ordered the national planning agency (Bappenas) to lead the revision process. Bappenas organised focus group sessions with 69 stakeholders and engaged the Indonesian Ministries of Maritime Affairs, of Environment and of Fisheries who were not involved in NCICD. The Dutch and Korean experts were largely not involved in this process. This master plan also takes a polder as starting point, but relies on dikes closer to the mainland instead of closing off Jakarta Bay. Moreover, Bappenas proposes to focus on land subsidence first, thereby postponing the final investment decision for the sea wall to 2030.

The consortium also updated NCICD1 to NCICD2. The updated master plan stands for National Capital Integrated Coastal Development Strategy, whereby (urban) development replaced (flood) defence. Also, the Great Garuda Wall lost its bird-like shape and became ‘just’ an Outer Sea Wall in the updated plan. NCICD2 states a final investment decision should be taken in 2018, so that the Sea Wall will be operational in 2030. In addition, NCICD shall be integrated with the existing plans for 17 artificial islands for property development. This integration could create financial leverage and prevent competition over reclamation in Jakarta Bay. In particular, the integration with the artificial island triggered opposition. Since 1995, when the plan for the 17 artificial islands was first introduced, local communities and organisations opposed their construction (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017). Since both plans have been associated, the opposition also affects the flood protection component of NCICD.

The Ministries of Maritime Affairs, of Environment and of Fisheries believe the negative social and environmental impact collides with their ministries’ interests. Concurrently, several Dutch and Indonesian NGOs – among others representing the interests of fishermen and the environment – unite in the ‘Save Jakarta Bay’ coalition to protest the NCICD plans (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017). Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (‘Ahok’) of the province DKI Jakarta still supported NCICD, but in early 2017 he suddenly disappeared from the political arena and the impasse was complete. His successor, Anies Baswedan, actively campaigned against reclamation in Jakarta Bay. Involved actors believe the president is still supportive of the proposed strategy, although he has refrained from further engagement in the discussion.

We take May 2017 as a cut-off point; later developments are not included in this study. The Dutch consortium is reviewing the feasibility of Bappenas’ master plan. The results of this review were not yet conclusive in May 2017. In August 2018, the status quo had not changed much: the impasse was still present. Insiders expect that political decisions will only be taken after the presidential elections in Indonesia in 2019.

4.4. Summary of results: discussing constraining factors

4.4.1. Environment

We observe a highly dynamic and polarised policy arena. Although the political tide was favourable in JCDS, that is, the early stages of transfer, opposition to the transferred ideas increased during NCICD1 and NCICD2. Jakarta’s governor, a political champion for NCICD, disappeared from the arena. Also, NCICD1 and 2 have had three different project leaders in 4 years, representing different ministries. There is no shared vision between these ministries and they can block each other’s plans, for example, by refusing to issue a permit. “Well, what you see is a bit of a polarised country, without a sort of common norms and knowledge level.” – Dutch consultant. Currently, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing is acting as project leader, but responsibilities for flood management are dispersed: “In principal the government is decentralised, some responsibilities are legally assigned to local governments, others to provinces and, again, other ones to the national government.” In combination with the emergence of an alternative strategy originating from high policy levels during NCICD2, the resulting political environment contributed to the impasse. Important key players (such as governor Ahok) could no longer use their influence to create a support base and other influential parties used their influence to create an alternative (“And then the Ministry of Bappenas, national planning (…), said and now we’ll step in. They started to make an alternative plan”. – Dutch consultant) or opposition, like the new governor, who “is not the one who fancies making big infrastructure. (…) He is more into the people power thing.” – Respondent from an Indonesian NGO.

4.4.2. Transferability

We found the transferability to be facilitating to policy transfer, at least in earlier phases of transfer. The Dutch consortium relied on the strong reputation of the Netherlands as a legitimate source when initiating the transfer in 2007. “This kind of comprehensive and integrated coastal water resources and land resources development project, you know, there are three big countries in the world I think. One is the Dutch.” – Respondent from KOICA. This reputation concerned the Dutch delta management and planning as best practice policy and the involved organisations as trusted advisors to Indonesia. In 2007, the Indonesian government was open to Dutch advice and all parties agreed that short-term, ‘no-regret’ measures were indispensable to protect Jakarta to imminent flood risk. However, a serious mismatch between objectives became visible once this original focus shifted to long-term flood protection during NCICD1. The emphasis on long-term orientation, adaptive planning and integrated policymaking by the Dutch consortium is a far end from Indonesian practice (Blomkamp et al. Citation2017). Indonesian policies are made for administrative divisions instead of the natural landscape entities that are required for effective delta management (Bucx et al. Citation2014). Also, long-term orientation collides with the ad hoc practice of planning processes in Jakarta. The Indonesian government is furthermore considered to respond to yesterday’s issues, instead of addressing the challenges ahead. This low institutional fit constrains the transfer.

At the same time, objectives became ambiguous. The consortium has formulated the goal to make Jakarta ‘flood free’ by 2030 and frames damage as the result of flooding in both humanitarian (i.e. lives and homes lost) and economic terms. Besides the heavily affected slum-dwellers (van Voorst Citation2016), most Jakartans perceive annual small-scale floods to be a nuisance rather than the disastrous event the Dutch consultants consider them to be. Also, the original goal of flood protection became intertwined with secondary goals of urban development and prestigious infrastructure development, when the land reclamation was associated with NCICD2. Critics of the proposed NCICD claim that the Dutch consortium is mainly interested in a ‘good’ solution for their own interests: a solution that generates business in the implementation phase. The consortium argues that there is no hidden agenda.

My commercial interest is now to make this project, no matter how, (…) a success. Success means: there is a decision and [flood] safety is ensured and the Netherlands is involved. (…) If the Dutch government believes they’ll get a bad product (…) then we have delivered a bad product and we won’t get a follow-up – Dutch consultant.

A ‘good’ solution would thus imply that the Dutch government is satisfied with the solution and the Dutch government is only satisfied when the Indonesian government is also satisfied. Nevertheless, concerns of conflicting (Dutch) commercial and (Indonesian) public interests prevail.

4.4.3. Adoptability

The suitability of the proposed policy remains disputed. Indonesian academic and government experts continue to doubt the contribution of ground water extractions in land subsidence. Dutch experts argue time is running out for stopping subsidence and that a sea wall is needed instead. However, critics argue that the consortium is not addressing the real issue (being land subsidence) because it is not part of the scope of their assignment from the Dutch government (Colven Citation2017). Local NGOs criticise the Indonesian government since NCICD1 for basing their decisions only on the views of engineers, instead of involving a broader set of advisors. As a result, the necessity and suitability of the proposed strategy remain debated. The strategy presently on the table (NCICD2) is called ‘megalomaniac’ in interviews and has a scale and complexity that is unprecedented in Indonesia (Colven Citation2017). This complexity is reflected by the amount of reports and technical details produced by the consortium in the past 10 years. Both Indonesian and foreign consultants consider the limited experience of the Indonesian government with such large scale projects a risk for proper evaluation of the proposed strategy and related decision-making. In addition, the government lacks experience with equivalent projects and capacity to implement the complex strategy if it were adopted. An official of DKI Jakarta explains: “There are many public-private partnerships on developing, for example, toll roads (…). There is experience, but not to manage very big projects.” Finally, although the organising capacity of the Indonesian government is limited, respondents admit that the Indonesian government has displayed vigour in previous infrastructure projects once a decision has been taken. Despite this, concerns are increasing about the ability of the Indonesian government to properly maintain the structural measures and enforce the regulations required for the proposed strategy.

Moreover, although the Dutch government is providing sufficient financial resources for the transfer until 2019, time and human resources are constrained. The Dutch consortium had vacancies for a delegated representative and CEO advisor for a significant time during NCICD2; and the Indonesian Project Management Unit (PMU) is underpopulated, with just three full-time junior positions. Higher-level policy officials, such as the Head of the PMU, are responsible for several projects at the same time and can only allocate limited time to keep up with the consultants. To compensate, Dutch consultants took up policy-advising tasks, although they considered it a side-job rather than the core business of the consortium. They also took over tasks that were the formal responsibility of their Indonesian counterparts, such as communicating about the justification of NCICD to communities.

On top of this comes the (perceived) time pressure, caused by the tight time schedule of the Dutch consortium. A Dutch consultant explains that “we see it as something very urgent, because a few times a year the dikes fail already and we know that there will be another King Tide in 2025 at last.”

4.4.4. Process design

Several factors that triggered the impasse emerged in the process design. These factors mainly concern building and maintaining a broad domestic support base for policy adoption. Engagement in NCICD used to be limited to counterparts and ministries. The initial support base for NCICD is rapidly losing ground to a powerful opposition that emerged since NCICD1. The master plan became highly controversial when the proposed solution for flood protection was integrated with the reclamation of 17 artificial islands (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017). Three Indonesian ministries, who thereby directly collided with NCICD’s supporting ministries, were involved in creating the Bappenas master plan in 2016. As a result, the Indonesian government’s stance is ambivalent (Colven Citation2017). Besides domestic support, external (international) support is another factor that is currently unclear, as the project is limited to the tri-country MoU without support from international financial organisations, such as the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank.

A high density of formal and informal relations characterises the exchange process itself in 2017. Consultants and high-level Indonesian policymakers interact informally outside meetings. Both the foreign consultants and the PMU are accommodated in the building of the coordinating Ministry of Public Works and Housing. This physical proximity of actors supports close ties in the network. However, the working culture is rather different. The international consultants are considered disciplined and fast-paced. As a PMU member describes it: “Yes of course, there are many differences. [The Dutch consultants] are very disciplined. (…) The Indonesian [government], we start to be professional, (…) we start to be more responsible.” While his colleague explains: “So the speed of the work of consultants and in the ministry, it is not the same, it is not similar. In the ministry, Indonesian ministry, it takes more time than the consultants.” The Indonesian government is also described as somewhat ignorant to its responsibilities, due to differing views on what exactly these responsibilities are and the required level of commitment of actors. The foreign consultants believe that involvement of Indonesian officials in drafting a strategy is essential, while other actors believe that the Indonesian officials should not be involved in the strategic planning, but only in following the steps of detailed engineering design. Indonesian bureaucrats wait for an official request by higher administrative levels (e.g. a minister) before engaging in the transfer process. Finally, when Indonesia could not provide their part of the required resources, the transfer could further tap into Dutch resources. These latter efforts have paid off, as involved actors agree that the process is “somehow drifting in the right direction”, although they are also perceived as a policy-push. Nonetheless, learning is limited to tactical (first-level) learning. Indonesian actors have learned about policy instruments deployed in the Netherlands, but underlying goals (such as the level of flood risk that should be allowed) was not openly re-evaluated.

4.5. Relating factors: three interrelated explanations for a deadlock

From the factors described in the last paragraphs, we have extracted three interrelated explanations for the emergence of an impasse, related to the practical feasibility, the rise of opposing coalitions and the execution of the transfer process. These explanations incorporate various factors mentioned in the framework described in Section 2.

The first explanation concerns the feasibility and compatibility of the created strategy and thereby relates mainly to issues of transferability and adoptability, as outlined in Section 2. The DDA-based strategy uses a different conceptualisation of flood risk management than the Indonesian practice, thereby risking incompatibility. The Dutch consortium takes integrated, long-term oriented and adaptive planning as a starting point, while planning in Indonesia is sectoral, decentralised, ad hoc and responsive in practice. Despite the efforts of the Dutch consultants in the process design (to adjust their advice to the values, practices and beliefs of their Indonesian counterpart) the ideological gap has not yet been bridged, contributing to the impasse.

Second, the content of the NCICD master plan collides with the interests of a powerful actor coalition. This explanation emphasises the role of actor coalitions as a crucial part of the process design (as outlined in Section 2.3). The Bappenas master plan relies on stopping land subsidence, thereby responding to criticism on NCICD by NGOs and some of the Indonesian ministries (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017). However, the other coalition (consisting of the Dutch consortium and another set of Indonesian ministries) considers stopping subsidence in time to be unrealistic and focusses on a solution involving the outer sea wall. This coalition values the opportunities that NCICD2 offers for raising Jakarta’s allure and for property development (Colven Citation2017). The fact that there are now two dominant discourses, whereby actors do not engage in a process of frame reflection or policy-oriented learning, is an important contribution to the current impasse. The more paradigmatic policy beliefs between these two coalitions differ, especially when it comes to the belief about the extent to which the physical system of the subsurface can be influenced by human behaviour. The more instrumental beliefs differ on the issue of whether it is possible and desirable to focus on policy measures to stop subsidence and what its consequences could be.

Third, the design of this process also contributes in another way to the implementation impasse. It seems the Indonesian government cannot yet take an informed decision because of the way in which the strategy was created and communicated to Indonesian actors. The Dutch government aims to transfer the DDA directly to policy levels ‘as high as possible’. This aim seems legitimate as it ensures access to decision-makers, which is a crucial condition for adoption (Kerlin Citation2009). At the same time, this approach results in (technology) consultants who transfer knowledge to top-level bureaucrats. Two issues arise. Dutch consultants stress the importance of rational, evidence-based policymaking, emphasising the importance of linear policymaking and joint fact-finding, while Indonesian policymaking is based merely on power relations (Blomkamp et al. Citation2017). Indonesian top-level bureaucrats have neither the technological knowledge to assess the consultants’ advice nor the time to read all the detailed reports. A lack of human resources and expertise constrains the Indonesian government in evaluating the given advice. As a result, the transfer of the Dutch knowledge remains limited and no decision has yet been taken.

5. Conclusion and discussion

This study aimed to explain how an impasse emerged in the transfer of the DDA to Jakarta, Indonesia. We identified several constraining factors in our theoretical framework and captured these with three explanations. The first explanation points to differences between the Dutch advice and Indonesian practice, thereby highlighting constraining factors of suitability (transferability) and feasibility (adoptability). The second explanation describes the presence of actor coalitions that advocate different strategies and confirms the necessity for a broad support base among actors. The third explanation points to the role of the knowledge exchange process’ set-up. Each of the explanations demonstrates that an interplay of factors, rather than a single factor, explains why transfer results in resistance instead of adoption or adaptation (Heiduk Citation2016). None of the explanations alone seems sufficient to explain the impasse, thereby stressing the dynamic nature of the policy transfer and learning process (Biesbroek et al. Citation2014). A striking example in this study was the transition of the political climate from facilitating adoption to triggering stagnation. We thereby adhere to a group of scholars who advocate for considering longer time periods when reviewing a policy transfer process (Dussauge-Laguna Citation2012; Wood Citation2015a).

The complexity and required level of change of the NCICD master plan illustrate that paradigmatic learning is needed: the norms, objectives and practices that inspired NCICD collide with the dominant norms, objectives and practices in Indonesia. However, the requirements for such learning (Hall Citation1993) were all absent: there is no broad domestic support base and the Indonesian government has limited expertise to evaluate the conflicting opinions of experts regarding the strategy. A lack of human resources at the PMU and limited financial resources amplify this. Moreover, at the moment there is no sense of urgency within the Indonesian government to change current practice. As a result, the status quo is maintained and actors are trapped in an impasse.

The absence of third-level learning seems to be related to the uneven power relationship between the sender and receiver. The Dutch government provides most resources for the transfer process and the Dutch consortium overrules the Indonesian recipients in terms of level of technology and knowledge, resulting in the inequality of partners described by Stead, De Jong and Reinholde (Citation2008). The set-up of the knowledge exchange process has a central role. This and other studies (e.g. Colven Citation2017) reveal that the consortium experiences less commitment from the Indonesian government to the process of knowledge exchange than anticipated and required for in their work plans. We observed great efforts to compensate for this. Nevertheless, it seems that these efforts have the paradoxical effect that they reinforce the apathy of the Indonesian government to take ownership of the process and fuel resistance against the Dutch proposal. This observation reflects what Ostrom and Gibson (Citation2001) call the contradiction between control and ownership of the project, whereby consultants are inclined to keep control over the process to achieve (short-term) progress, but fail to ensure (long-term) ownership. This crowding-out effect deserves further attention.

The knowledge transfer is predominantly targeted at instrumental and tactical learning. The advising consultants focus on the detailed design of the strategy (as a way to maintain progress in spite of the controversial underlying issue) and thus give insufficient attention to creating consensus about the underlying values of the DDA. As a result, the impasse seems to have emerged because of, rather than despite, the way the transfer process is executed.

Impasses have been reported (and sometimes solved) in other instances of transferring the DDA; and issues with policy transfer from developed to developing countries have been reported more frequently (e.g. Rahman, Naz, and Nand Citation2013). A comparative case study analysis might enhance the generalisability of this single case study when identifying similar patterns in other cases or, alternatively, could highlight potential alternative paths. If transferring the DDA is to accommodate or trigger third-level learning, future research could address how the process should be set up to achieve this. Future research may also focus on potential interventions to overcome these impasses (Biesbroek et al. Citation2014).

At the moment, the policy transfer process is still ongoing. We paused at May 2017 and rewind the process back to 2007. This gave us insights in how to explain the existence of the impasse in the transfer process at this time. Nonetheless, this impasse might be solved in the remainder of NCICD2. Whether or not the impasse persists, it would be interesting to study what caused this impasse to resolve/persist and what we can learn from that for the design of future policy transfer processes.

The Jakarta case reveals two other lessons about policy transfer. First of all, processes of policy transfer ask for changes in existing policies and thus for policy learning. Facilitating these learning processes successfully implies a range of policy competencies, including managing attention, detecting and using policy windows, organising joint fact-finding, and safeguarding political support. Since policy transfer processes are often dominated by experts (who know much about the content of the policies), these skills are often underrepresented. Designing effective policy transfer processes thus also requires that these competencies are available.

The diffusion of the DDA is also targeted at other deltas, both aiming to enhance delta management in those countries in an era of climate change and to increase revenues from delta technology export (Rijksoverheid Citation2016; Zwarteveen et al. Citation2017). Our study into the emergence of the impasse in developing a strategy for Jakarta, Indonesia, revealed that this impasse might be the result of a more structural issue, namely that of the unequal partnership (Stead, De Jong, and Reinholde Citation2008) between the Netherlands and the receiving countries. The current process prevents third-level learning to occur and results in Dutch ownership and control over the project. Strategic delta planning is being advocated (Wesselink Citation2016), but in order to effectively introduce strategic delta planning to the targeted transition countries, Dutch government officials and consultants should pay attention to the more fundamental differences in interests (technological), knowledge and resources when translating the DDA, and have to be aware of this structural imbalance and the consequences it could have.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of factors that affect the policy transfer process (Minkman, Van Buuren, and Bekkers Citation2018).

CJEP-2018-0140.R1_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (16 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the respondents for their cooperation, our colleagues and two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abidin, H. Z., H. Andreas, I. Gumilar, Y. Fukuda, Y. E. Pohan, and T. Deguchi. 2011. “Land Subsidence of Jakarta (Indonesia) and Its Relation with Urban Development.” Natural Hazards 59 (3): 1753–1771. doi:10.1007/s11069-011-9866-9

- Ademmer, E., and T. A. Börzel. 2013. “Migration, Energy and Good Governance in the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (4): 581–608. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/09668136.2013.766038

- Allouche, J. 2016. “The Birth and Spread of IWRM: A Case Study of Global Policy Diffusion.” Water Alternatives 9 (3): 412–433.

- Alphen, J. van. 2016. “The Delta Programme and Updated Flood Risk Management Policies in the Netherlands.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 9: 310–319. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12183

- Attard, M., and M. Enoch. 2011. “Policy Transfer and the Introduction of Road Pricing in Valletta, Malta.” Transport Policy 18 (3): 544–553. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.004

- Bakker, M., S. Kishimoto, and C. Nooy. 2017. Social Justice at Bay: The Dutch Role in Jakarta's Coastal Defence. SOMO, Both ENDS and TNI. https://www.bothends.org/en/Whats-new/Publicaties/Social-justice-at-bay-The-Dutch-role-in-Jakartas-coastal-defence-and-land-reclamation

- Bennett, C. J., and M. Howlett. 1992. “The Lessons of Leaming: Reconciling Theories of Policy Leaming and Policy Change.” Policy Sciences 25 (3): 275–294. doi:10.1007/BF00138786

- Bennett, S., S. L. Dalglish, P. A. Juma, and D. C. Rodríguez. 2015. “Altogether Now… Understanding the Role of International Organizations in iCCM Policy Transfer.” Health Policy and Planning 30 (Suppl. 2): ii26–ii35. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv071

- Benson, D., and A. Jordan. 2011. “What Have We Learned from Policy Transfer Research? Dolowitz and Marsh Revisited.” Political Studies Review 9 (3): 366–378. doi:10.1111/j.1478-9302.2011.00240.x

- Biesbroek, G. R., C. J. A. M. Termeer, J. E. M. Klostermann, and P. Kabat. 2014. “Rethinking Barriers to Adaptation: Mechanism-Based Explanation of Impasses in the Governance of an Innovative Adaptation Measure.” Global Environmental Change 26: 108–118. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.004

- Blomkamp, E., M. N. Sholikin, F. Nursyamsi, and J. M. Lewis. 2017. Understanding Policymaking in Indonesia: In Search of a Policy Cycle. Melbourne: The Policy Lab (The University of Melbourne) and the Indonesian Centre for Law and Policy Studies (PSHK).

- Borg, W. R., and M. D. Gall. 2003. Educational Research: An Introduction. (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Bucx, T., W. van Driel, H. de Boer, S. Graas, V. Langenberg, M. Marchand, and C. van de Guchte. 2014. Comparative Assessment of the Vulnerability and Resilience of Deltas. Wageningen: Delta Alliance. http://edepot.wur.nl/188269

- Busch, P.-O., H. Jörgens, and K. Tews. 2005. “The Global Diffusion of Regulatory Instruments: The Making of a New International Environmental Regime.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 598 (1): 146–167. doi:10.1177/0002716204272355

- Chapman, B., and D. Greenaway. 2006. “Learning to Live with Loans? International Policy Transfer and the Funding of Higher Education.” The World Economy 29 (8): 1057–1075. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2006.00822.x

- Colven, E. 2017. “Understanding the Allure of Big Infrastructure: Jakarta’s Great Garuda Sea Wall Project.” Water Alternatives 10 (2): 250–264.

- Deltares. 2016. Knowledge Management of NCICD Inception Report. Jakarta, Indonesia: Deltares.

- Dolowitz, D., and D. Marsh. 1996. “Who Learns What from Whom: A Review of the Policy Transfer Literature.” Political Studies 44 (2): 343–351. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

- Dolowitz, D., and D. Marsh. 2000. “Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making.” Governance 13 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- Dunlop, C. A. 2009. “Policy Transfer as Learning: Capturing Variation in What Decision-Makers Learn from Epistemic Communities.” Policy Studies 30 (3): 289–311. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/01442870902863869

- Dussauge-Laguna, M. I. 2012. “The Neglected Dimension: Bringing Time Back into Cross-National Policy Transfer Studies.” Policy Studies 33 (6): 567–585. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/01442872.2012.728900

- Eccleston, R., and R. Woodward. 2014. “Pathologies in International Policy Transfer: The Case of the OECD Tax Transparency Initiative.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 16 (3): 216–229. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/13876988.2013.854446

- Evans, M., and J. Davies. 1999. “Understanding Policy Transfer: A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective.” Public Administration 77 (2): 361–385. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00158

- Fawcett, P., and D. Marsh. 2012. “Policy Transfer and Policy Success: The Case of the Gateway Review Process (2001–10).” Government and Opposition 47 (2): 162–185. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01358.x

- Freeman, R. 2009. “What Is “Translation.” Evidence and Policy 5 (4): 429–447. doi:10.1007/BF00044325.

- Hall, P. A. 1993. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” 25 (3): 275–296.

- Heiduk, F. 2016. “Externalizing the EU’s Justice and Home Affairs to Southeast Asia: Prospects and Limitations.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 12 (3): 717–733.

- James, O., and M. Lodge. 2003. “The Limitations of ‘Policy Transfer’ and ‘Lesson Drawing’ for Public Policy Research.” Political Studies Review 1 (2): 179–193. doi:10.1111/1478-9299.t01-1-00003

- Jinnah, S., and A. Lindsay. 2016. “Diffusion Through Issue Linkage: Environmental Norms in US Trade Agreements.” Global Environmental Politics 16 (3): 41–61. doi:10.1162/GLEP_a_00365

- Jong, M. de, and X. Bao. 2007. “Transferring the Technology, Policy, and Management Concept from The Netherlands to China.” Knowledge, Technology and Policy 19 (4): 119–136. doi:10.1007/BF02914894

- Kerlin, J. A. 2009. “The Diffusion of State-Level Nonprofit Program Innovation: The T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood Project.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39 (3): 478–497. doi:10.1177/0899764009332338

- Khirfan, L., B. Momani, and Z. Jaffer. 2013. “Whose Authority? Exporting Canadian Urban Planning Expertise to Jordan and Abu Dhabi.” Geoforum 50: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.07.007

- Klijn, F., H. Kreibich, H. de Moel, and E. Penning-Rowsell. 2015. “Adaptive Flood Risk Management Planning Based on a Comprehensive Flood Risk Conceptualisation.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 20 (6): 845–864.

- Kops, A. 2012. Quick Scan of Master Plans Jakarta Coastal Defence Strategy Bridging Phase. Jakarta: Deltares.

- Larmour, P. 2002. “Conditionally, Coercion and Other Forms of “Power”: International Financial Institutions in the Pacific.” 22 (3), 249–260. doi:10.1002/pad.228

- Marsden, G., K. T. Frick, A. D. May, and E. Deakin. 2012. “Bounded Rationality in Policy Learning Amongst Cities: Lessons from the Transport Sector.” Environment and Planning A 44 (4): 905–920. doi:10.1068/a44210

- Marsh, D., and A. Mcconnell. 2010. “Towards a Framework for Establishing Policy Success.” Public Administration 88 (2): 564–583. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01803.x

- May, P. J. 1992. “Policy Learning and Failure.” Journal of Public Policy 12 (4): 331–354.

- Michaels, S., and R. de Loë. 2010. “Importing Notions of Governance: Two Examples from the History of Canadian Water Policy.” American Review of Canadian Studies 40 (4): 495–507. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/02722011.2010.519395

- Milhorance de Castro, C. 2014. “Brazil’s Cooperation with Sub-Saharan Africa in the Rural Sector: The International Circulation of Instruments of Public Policy.” Latin American Perspectives 41 (5): 75–93. doi:10.1177/0094582X14544108

- Minkman, E., M. W. van Buuren, and V. J. J. M. Bekkers. 2018. “Policy transfer routes: an evidence-based conceptual model to explain policy adoption.” Policy Studies 39 (2): 222–250, doi: 10.1080/01442872.2018.1451503.

- Mukhtarov, F. 2014. “Rethinking the Travel of Ideas: Policy Translation in the Water Sector.” Policy and Politics 42 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1332/030557312X655459

- Mukhtarov, F., S. Fox, N. Mukhamedova, and K. Wegerich. 2015. “Interactive Institutional Design and Contextual Relevance: Water User Groups in Turkey, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan.” Environmental Science and Policy 53: 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.10.006

- NWP. 2013. NWP jaarverslag 2013: Meer impact in het buitenland [NWP Annual Report 2013: More Impact Abroad]. Den Haag, the Netherlands: NWP.

- NWP. 2016. Indonesia – The Netherlands Integrated Approach of Future Water Challenges. Den Haag, the Netherlands: NWP.

- O’Donovan, K. 2017. “Policy Failure and Policy Learning: Examining the Conditions of Learning after Disaster.” Review of Policy Research 34 (4): 537–558. doi:10.1111/ropr.12239

- Onursal-Beşgül, Ö. 2016. “Policy Transfer and Discursive De-Europeanisation: Higher Education from Bologna to Turkey.” South European Society and Politics 21 (1): 91–103. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/13608746.2016.1152019

- Ostrom, E., and C. Gibson. 2001. Sustainability Aid, Incentives, and Sustainability. Stockholm, Sweden: Sida Studies in Evaluation.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. 2009. “A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Adaptive Capacity and Multi-Level Learning Processes in Resource Governance Regimes.” Global Environmental Change 19 (3): 354–365. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

- Rahman, M. H., R. Naz, and A. Nand. 2013. “Public Sector Reforms in Fiji: Examining Policy Implementation Setting and Administrative Culture.” Administrative Culture in Developing and Transitional Countries 36 (13): 982–995. doi:01442872.2018.1451503/01900692.2013.773031

- Ravesteijn, W., and J. Kop. 2008. For Profit and Prosperity: The Contribution Made by Dutch Engineers to Public Works in Indonesia, 1800–2000. Zaltbommel: Aprilis.

- Rijksoverheid 2010. Deltaprogramma 2011: Werk aan de delta. Investeren in een veilig en aantrekkelijk Nederland, nu en morgen [Delta Programme 2011: Working on the Delta. Acting Today, Preparing for Tomorrow]. Den Haag, The Netherlands.

- Rijksoverheid 2014. The Delta Approach. Den Haag, the Netherlands: NWP. https://www.dutchwatersector.com/uploads/2014/11/140209-01-delta-approach-a4-web-07.pdf

- Rijksoverheid 2016. Convergerende Stromen: Internationale Waterambitie [Converging Flows: International Water Ambition]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: NWP.

- Rose, R. 1991. “What Is Lesson-Drawing?.” Journal of Public Policy 11 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00004918

- Slob, M., and P. Bloemen. 2014. Solidarity Flexibility Sustainability: Core Values of the Delta Programme: A Reflection. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment Ministry of Economic Affairs.

- Stead, D., M. De Jong, and I. Reinholde. 2008. “Urban Transport Policy Transfer in Central and Eastern Europe.” disP – the Planning Review 44 (172): 62–73. doi:10.1080/02513625.2008.10557003

- Stone, D. 1999. “Learning Lessons and Transferring Policy Across Time, Space and Disciplines.” Politics 19 (1): 51–59. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.00086

- Stone, D. 2004. “Transfer Agents and Global Networks in the ‘Transnationalization’ of Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (3): 545–566. doi:10.1080/13501760410001694291

- Stone, D. 2016. “Understanding the Transfer of Policy Failure: Bricolage, Experimentalism and Translation.” Policy and Politics 45 (1): 55–70. doi:10.1332/030557316X14748914098041

- Syvitski, J. P. M., A. J. Kettner, I. Overeem, E. W. H. Hutton, M. T. Hannon, G. R. Brakenridge, J. Day., et al. 2009. “Sinking Deltas Due to Human Activities.” Nature Geoscience 2 (10): 681–686. doi:10.1038/ngeo629

- Van Buuren, A., G. J. Ellen, and J. F. Warner. 2016. “Path-Dependency and Policy Learning in the Dutch Delta: Toward More Resilient Flood Risk Management in the Netherlands?” Ecology and Society 21 (4)‐43: 1–11.

- Van Buuren, A., J. Lawrence, K. Potter, and J. F. Warner. 2018. “Introducing Adaptive Flood Risk Management in England, New Zealand, and the Netherlands: The Impact of Administrative Traditions.” Review of Policy Research 0 (0): 1–23.

- Vaughan, S., and I. Rafanell. 2012. “Interaction, Consensus and Unpredictability in Development Policy ‘Transfer’ and Practice.” Critical Policy Studies 6 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1080/19460171.2012.659889

- Velde, D. M. van de. 2013. “Learning from the Japanese Railways: Experience in The Netherlands.” Policy and Society 32 (2): 143–161. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2013.05.003

- Verduijn, S. H., S. V. Meijerink, and P. Leroy. 2012. “How the Second Delta Committee Set the Agenda for Climate Adaptation Policy: A Dutch Case Study on Framing Strategies for Policy Change.” Water Alternatives 5 (2): 469–484.

- Vinke-de Kruijf, J., D. C. M. Augustijn, and H. T. A. Bressers. 2012. “Evaluation of Policy Transfer Interventions: Lessons from a Dutch-Romanian Planning Project.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 14 (2): 139–160. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2012.680700

- Vinke-de Kruijf, J., and C. Pahl-Wostl. 2016. “A Multi-Level Perspective on Learning About Climate Change Adaptation Through International Cooperation.” Environmental Science and Policy. 66: 242–249 doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2016.07.004

- Voorst, R. van 2016. “Formal and Informal Flood Governance in Jakarta, Indonesia.” Habitat International. 52: 5–10. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.023

- Warren, P. 2017. “Transferability of Demand-Side Policies Between Countries.” Energy Policy 109: 757–766. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.07.032

- Wesselink, A. 2016. “Trends in Flood Risk Management in Deltas Around the World: Are We Going ‘Soft’?.” International Journal of Water Governance 3 (4): 25–46. doi:10.7564/15-IJWG90

- WGC. 2013. De Nederlandse Delta-aanpak [The Dutch Delta Approach]. Den Haag, the Netherlands: Water Governance Centre.

- Wood, A. 2015a. “Competing for Knowledge: Leaders and Laggards of Bus Rapid Transit in South Africa.” Urban Forum 26 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1007/s12132-014-9248-y

- Wood, A. 2015b. “Multiple Temporalities of Policy Circulation: Gradual, Repetitive and Delayed Processes of BRT Adoption in South African Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (3): 568–580. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12216

- Xu, Y. C. 2005. “Models, Templates and Currents.” The World Bank and Electricity Reform. Review of International Political E 12 (4): 647–673. doi:10.1080/09692290500240370

- Zegwaard, A. 2016. Mud: Deltas Dealing with Uncertainties. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

- Zhang, J. 2012. “From Hong Kong’s Capitalist Fundamentals to Singapore’s Authoritarian Governance: The Policy Mobility of Neo-Liberalising Shenzhen, China.” Urban Studies 49 (13): 2853–2871. doi:10.1177/0042098012452455

- Zwarteveen, M., J. S. Kemerink-Seyoum, M. Kooy, J. Evers, T. A. Guerrero, B. Batubara, A. Wesselink. 2017. “Engaging with the Politics of Water Governance.” WIREs Water 4: e01245. doi:10.1002/wat2.1245