Abstract

The governance of adaptation to climate change is an emerging multi-level challenge, and learning is a central governance factor in such a new empirical field. We analyze, through a literature review, how learning is addressed in both the general multi-level governance literature and the governance of adaptation to climate change literature. We explore the main congruencies and divergences between these two literature strands and identify promising directions to conceptualize learning in multi-level governance of adaptation. The review summarizes the main approaches to learning in these two strands and outlines conceptualizations of learning, the methods suggested and applied to assess learning, the way learning processes and strategies are understood, and the critical factors identified and described. The review contrasts policy learning approaches frequently used in multi-level governance literature with social learning approaches that are more common in adaptation literature to explore common ground and differences in order to build a conceptual framework and provide directions for further research.

1. Introduction

The governance of adaptation to climate change (henceforth governance of adaptation) has become a truly multi-level governance affair since the adoption of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2015. Although with the adoption of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 the global climate regime did pay some attention to adaptation, it was not until the Paris Agreement that adaptation was put on a par with mitigation. The agreement’s global adaptation goal cemented a multi-level institutional framework for adaptation that has evolved faster since 2010. This framework includes normative principles for governance of adaptation, international funding mechanisms, and an adaptation committee under the UNFCCC with advisory, coordination, and capacity-building mandates. Multi-level governance usually involves not only multi-level institutional frameworks but also interactions between various stakeholders across different levels of governance. In the case of governance of adaptation, stretching from global negotiations to local implementation and vice versa, local and national policy development is increasingly influenced by international agreements and policy instruments (e.g. Bulkeley Citation2001; Andonova, Betsill, and Bulkeley Citation2009; Amundsen, Berglund, and Westskog Citation2010).

Given the newness of governance of adaptation per se in modern society, the already noticeable impacts of climate change, and the newness of a multi-level context for adaptation, it is reasonable to expect that learning will be a key aspect of emerging governance efforts. Learning is recognized in adaptation research as an important governance of adaptation mechanism (e.g. Adger, Arnell, and Tompkins Citation2005; Berkhout, Hertin, and Gann Citation2006; Pahl-Wostl Citation2009; Tschakert and Dietrich Citation2010). It is often described as a key instrument for adjusting the course of action toward enhanced climate resilience and creating knowledge among stakeholders for facing the challenges and uncertainties of a changing climate.

It is against this background that we took the following proposition as the starting point for this study: governance of adaptation could benefit from a better understanding of learning in the multi-level context of such governance (e.g. Pahl-Wostl Citation2009; Reed et al. Citation2010). The burgeoning literature on social learning in natural resource management has been systematically reviewed (e.g. Rodela Citation2011; Rodela, Cundill, and Wals Citation2012), but the intersections of learning across governance levels, including for governance of adaptation, remain unexplored. This study reviews two strands of literature – governance of adaptation and multi-level governance – as a first effort to gain insights into the role of learning in multi-level governance of adaptation.

We do this by asking the following questions: (i) how is learning defined and conceptualized? (ii) how is learning operationalized, assessed, and measured? (iii) what are the important processes and strategies for learning? and (iv) what factors encourage or hamper learning in a given context? The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the methods applied for the literature review and for the general analysis of the literature sample. In Section 3, we analyze the answer to our four questions. In Section 4 and in the conclusions, we summarize common ground for a conceptualization of learning, main constraints and difficulties in addressing learning in multi-level governance settings, and questions to be addressed in further research.

2. Review methodology and literature sample

The objective of this review was to analyze discussions on learning in two literature strands – multi-level governance and governance of adaptation – to gain insights into the role of learning in multi-level governance of adaptation and followed similar methodological steps applied in systematic reviews, for example, in climate change governance research (e.g. Vink, Dewulf, and Termeer Citation2013; Petticrew and McCartney Citation2011).

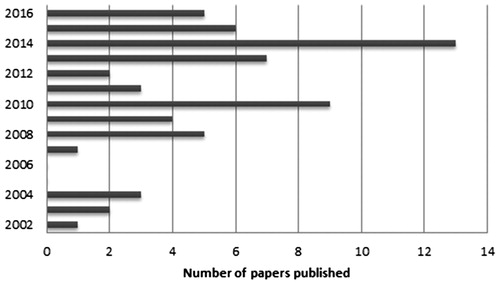

Our bibliographic search for peer-reviewed journal articles was performed in the databases SCOPUS and Web of Science between July 2014 and March 2017. By the end of 2016, the initial sample comprised 1,084 papers on “governance AND adaptation” in SCOPUS and 1,130 in Web of Science, and 2,405 on “multi-level OR multi-level AND governance” in SCOPUS and 1,970 in Web of Science. We then applied the word “learning” in titles, abstracts, and keywords as an inclusion criterion, resulting in 123 papers on “governance of adaptation” in SCOPUS and 183 in Web of Science, and 147 papers on “multi-level OR multi-level governance” in SCOPUS and 169 in Web of Science. Including the word “learning” in the title indicating a strong focus on this topic, merging the results of SCOPUS and Web of Science, and refining the sample by excluding publications that did not fit the screening criteria, we obtained a final sample of 58 papers in English (see Appendix I [online supplemental data]): 21 papers address only governance of adaptation questions, 32 papers address multi-level governance, and 5 papers satisfy both criteria. Whereas the SCOPUS word search coincides with the title, abstract, and keywords, Web of Science includes publications that use close synonyms e.g. “adaptive governance”, “adaptive management”, and “multiscale governance” in the title, abstract, and keywords, thereby yielding publications not identified by SCOPUS. Plotting the publication years for this sample () shows a growing interest in learning within these research communities. It is important to note that we did not apply a limitation on publishing year; the oldest publication included dates back to 2002.

The final sample covers a broad range of disciplines within both the environmental and the social sciences. The academic journals in which they were published include topics such as European planning, public policy, and law (7), environmental policy and governance (8), global environmental change (3), water (5), and urban studies (4).

An initial screening of literature abstracts and keywords enabled us to identify the four questions posed in Section 1. provides an overview of how these four aspects are considered within the sample.

Table 1. Overview of how learning is addressed in the reviewed literature.

This review has some limitations. Given the large volume of learning literature in the context of environmental governance, the review focuses on a very specific subset of the literature, thus capturing only a portion of the discussion on organizational, policy, and social learning in these fields (e.g. Bandura and Adams Citation1977; Argyris Citation1976; Hall Citation1993).

3. Results

The results of the literature review with regard to the four questions are presented below.

3.1. How is learning defined?

The governance of adaptation literature refers mostly to social learning (McCrum et al. Citation2009; Nuorteva, Keskinen, and Varis Citation2010; van der Wahl et al. Citation2014; Baird et al. Citation2014; Shaw and Kristjanson Citation2014; Blackmore Citation2014; Ison et al. Citation2015; Siebenhüner, Rodela, and Ecker Citation2016) and policy and institutional learning (e.g. Rojas et al. Citation2009; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Steele et al. Citation2014; Thapa et al. Citation2016). Studies in this category have definitions with a clear emphasis on issues of collective action addressing environmental problems and challenges. In addition, a group of authors relate learning to questions of adaptive governance (Lynch and Brunner Citation2010; Ison, Collins, and Wallis Citation2015; Vella et al. Citation2015) and resilience (e.g. Nuorteva, Keskinen, and Varis Citation2010). A considerable number of the studies describe learning processes as occurring at the interface between knowledge domains or as a strategy that facilitates knowledge transfer and replication at different levels, without defining and describing it explicitly (e.g. Kashyap Citation2004; Jabeen, Johnson, and Allen Citation2010; Button et al. Citation2013; Silver et al. Citation2013).

Social learning is frequently defined as a convergent change in stakeholders’ perspectives on a particular problem and its possible solutions in light of both their own and other stakeholders’ views, interests, and positions with regard to the problem. Such social learning achieves a change in understanding that goes beyond the individual toward collectives and social networks.

Some studies describe how social learning creates the basis for integrated solutions that require collective support and/or concerted action by multiple stakeholders (e.g. McCrum et al. Citation2009; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Baird et al. Citation2014). McCrum et al. (Citation2009) show that social learning emerges from knowledge exchange and recognize that knowledge is contested, socially constructed, and used in specific contexts. Social learning challenges all actors to consider alternative perspectives, making learning a dynamic and transformative process. Social learning is defined by McCrum et al. (Citation2009) as a form of collective reflection and action to improve the management of human and environmental interrelations.

Some authors recognize that climate change adaptation requires not only the active participation of multiple stakeholders – including state and non-state actors – but also changes in governance approaches toward governance structures and dynamics that enable learning and transformation (e.g. Lynch and Brunner Citation2010; van der Wal et al. Citation2014). Van der Wal et al. (Citation2014) draw on the discussion on social learning, highlighting its potential role as a governance mechanism in natural resource management. Nuorteva, Keskinen, and Varis (Citation2010) see learning linked to the resilience of socio-ecological systems, arguing that, compared to ecological resilience, the resilience of social systems has an additional capacity to foresee and adapt to possible changes, and it is therefore defined as the degree to which a system is capable of learning and adopting new solutions.

Policy learning is another concept evoked by some authors in the reviewed governance of adaptation literature (e.g. Rojas et al. Citation2009; Janjua, Thomas, and McEvoy Citation2010; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Steele et al. Citation2014). The policy learning concept is used by various authors in the field of public administration and involves the learning process linked to policy. Policy learning, as described in the literature reviewed, generally refers to states as having the capacity to learn from their experiences and modify their actions on the basis of their evaluation of the impact of previous actions. The nature of policy changes varies from new and innovative policies to continuous refinements of past policies.

Changes in policies can reflect learning taking place at the level of formal institutions and governments. Rojas et al. (Citation2009) suggest a process by which lessons from past policies can be integrated into decision-making processes to enhance management and governance. Huntjens et al. (Citation2011) favor organizational learning approaches and apply the concept of double- and triple-loop learning to distinguish different levels of policy learning taking place in governance of adaptation processes. Steele et al. (Citation2014) draw on new institutionalism approaches as a theoretical lens for understanding and learning from complex questions, such as why particular governance agendas emerge, how they form, how they become mobilized and translated into action, including the role of key actors and collaborative networks in these processes.

The multi-level governance literature that addresses learning contains a considerable number of publications concerning the policymaking process. They draw on organizational, policy, and social learning definitions and frameworks and address questions of policy implementation and evaluation (e.g. Paraskevopoulos and Leonardi Citation2004; Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007; Borowski et al. Citation2008; Benz Citation2012).

The studies refer to policy learning as a mechanism to address typical questions of public administration, such as maintaining institutional memory (Getimis Citation2003), facilitating the adoption and transfer of policies (Benson, Jordan, and Huitema Citation2012), or facilitating the adoption of new rules (Paraskevopoulos and Leonardi Citation2004). Policy learning is also described as a process of collective action, with actors inventing new solutions and changing their policies accordingly (Benz Citation2012). Mutual learning is described as taking place when policymakers learn by exchanging information and experiences across the borders of their jurisdiction and between different governance levels (Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007).

Social learning is also of interest to multi-level governance scholars. Paraskevopoulos and Leonardi (Citation2004) see the process of social learning as a fundamental mechanism of domestic change in which networks and informal institutions act as mediating mechanisms affecting actors’ preferences and appropriation, leading to the reconceptualization of their interests and identities and thus facilitating learning and socialization processes. Social learning is also perceived as a factor of environmental governance, in particular the governance of wicked problems (Löf Citation2010; Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013; Johannessen and Hahn Citation2013; Reed et al. Citation2014). In this context, learning is perceived as a necessary factor in the governance of resilience and adaptive capacity (e.g. Löf Citation2010). The literature recognizes the need for governance systems that allow for better integration of different stakeholder views and enable the collective action needed to address environmental challenges. As in the governance of adaptation literature, the concepts of double- and triple-loop learning are adopted in order to describe the levels and depth of such learning (e.g. Paraskevopoulos and Leonardi Citation2004; Yuthas, Dillard, and Rogers Citation2004; Löf Citation2010; Johannessen and Hahn Citation2013).

In the small sample of literature that integrates governance of adaptation and multi-level governance, learning is perceived as an interactive process, with Dieleman (Citation2013) applying the experiential learning cycle (Fry and Kolb, Citation1979); Pelling et al. (Citation2008) highlighting the interplay of institutions and social learning at different governance levels to define policies and build institutions aimed at responding effectively to the challenges of climate change; Leys and Vanclay (Citation2011) describing the dynamic of social learning as a factor of adaptive co-management; and Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009) developing a conceptual framework addressing the dynamics and adaptive capacity of resource governance regimes as multi-level learning processes.

3.2. Operationalize, assess, and measure learning

The governance of adaptation literature recognizes the difficulties of establishing a common ground of definitions to operationalize and measure learning (e.g. Baird et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, only a few authors in the sample describe means to operationalize learning, and the approaches are rather divergent (see Appendix II for keyword references [online supplemental data]). Authors tend to identify and describe the learning process and look at the outcomes of such processes in terms of change and transformation at the level of individuals, communities, institutions, and the governance of collectives.

The triple-loop concept is highlighted as an entry to assess and operationalize learning (Pahl-Wostl Citation2009; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Baird et al. Citation2014; Siebenhüner, Rodela, and Ecker Citation2016) because it highlights different levels of learning, reflected in the type and depth of institutional change, which can serve as an indication of the depth of learning. Authors organize the assessments into various frameworks of typologies, indicators, and tools for assessing different levels of policy learning.

Baird et al. (Citation2014) differentiate between cognitive, normative, and relational learning to assess and measure learning. The authors apply a mixed-methods approach with a focus on quantitative measures, including concept map analysis, social network analysis, and self-reflective questions to gauge indicators for these three types of learning.

Van der Wal et al. (Citation2014) use changes in the convergence of stakeholder perspectives over time to describe and measure learning. The method, based on cultural theory (e.g. Thompson, Ellis, and Wildavsky Citation1990) integrates a set of scoring tables for measuring the convergence of points of view. This type of learning is well described and provides quantitative and visual reports. Adopting new institutionalism (e.g. Connor and Dovers, Citation2004), Steele et al. (Citation2014) apply an institutional learning framework covering different levels of institutional analysis, including the evolution of problem-solving strategies that encompass problem reframing, reorganization of government through the integration of policy and practice, and the transformative change that arises from the implementation of given policies. Rantala, Hajjar, and Skutsch (Citation2014) rely on social network mapping that might change over time to represent relational changes in information sharing among key stakeholders.

An emphasis on policy success, effectiveness, and knowledge transfer characterizes the approaches to measuring learning in the multi-level governance literature. Many authors describe the learning process and provide indications of multi-level learning occurring in such processes and the key outcomes of such processes at the level of individuals, collectives, policy, or institutions. Learning occurring across and between scales and governance levels is addressed by looking at learning aggregations – how learning is embedded in social and organizational practices and routines or becomes formally implemented and institutionalized (e.g. Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011). Aranguren, Larrea, and Wilson (Citation2010) argue that learning and lessons extracted from success stories are a good way to assess the outcomes of learning and innovation.

Nevertheless, there is no unified agreement on how to operationalize learning in the publications reviewed, and the suggested frameworks draw on diverse theoretical backgrounds. Axelsson et al. (Citation2013) suggest an analytical framework to assess learning that proposes five criteria, including ownership, stakeholder participation, the processes leading to explicit knowledge, observable results, and networks. To address governance and policy formulation problems, Schout (Citation2009) suggests a framework to position organizational learning in the context of governance learning in the EU’s multi-level administration. The framework differentiates between three interrelated categories – organizational learning, instrumental learning, and governance learning – to analyze positive or desired changes by policy implementation. Drawing on experience with communities of practice, Reed et al. (Citation2014) describe key elements that encourage learning leading to concerted action. These elements include: the convergence of goals, criteria, and knowledge, leading to more accurate mutual expectations and building trust and respect in relations; co-creation of knowledge needed to understand issues and practices; and/or a change in practices, norms, and procedures arising from the development of a mutual understanding of issues.

Analogous to the governance of adaptation literature, the multi-level governance literature frequently adopts the single-, double-, and triple-loop learning concept (Löf Citation2010; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013; Johannessen and Hahn Citation2013). Pahl Wostl et al. (Citation2013) develop a management and transition framework for an operational characterization of learning in case studies over time. The framework builds on action situations defined at a level of aggregation of social processes, building a framework for system assessments of learning taking place in management and policy processes.

The literature that integrates climate change adaptation and multi-level governance also draws on multiple-loop learning as a conceptual framework. Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009, 359–360) proposes a list of operational indicators of change processes.

3.3. Learning processes and strategies

The governance of adaptation literature describes learning processes at the interface between different knowledge domains (e.g. Reid Citation2016), drawing lessons from experience in facilitating policy advocacy and peer learning (e.g. Kashyap Citation2004; Rojas et al. Citation2009; Jabeen, Johnson, and Allen Citation2010; Nuorteva, Keskinen, and Varis Citation2010) and as a social learning process that can be initiated by platforms, communities of practice, and deliberative workshops.

For Nuorteva, Keskinen, and Varis (Citation2010), people’s capacity to cope with extreme events is enhanced by experiencing extreme events in the past. Valuable lessons for climate adaptation with regard to agency can be extracted from successful experiences in the arena of water governance, where local stakeholders and governmental agencies have been coping with climate variability and extreme events (Kashyap Citation2004). The experiences of the Cities and Climate Change Initiative (CCCI) promoted by UN-HABITAT in Asia (Button et al. Citation2013) and in West Africa (Silver et al. Citation2013) are good examples of learning and knowledge transfer among cities and municipal governments. A typology of cities facing similar challenges and solutions can help to organize and transfer knowledge among policymakers and communities, contributing to peer learning and policy implementation (e.g. Button et al. Citation2013; Silver et al. Citation2013).

Social learning processes are perceived as deliberative to enhance stakeholder covenants, reduce risk of social conflict, and enhance dialogue; learning platforms and stakeholder gatherings are encouraged to facilitate learning (e.g. McCrum et al. Citation2009; Button et al. Citation2013; Rantala, Hajjar, and Skutsch Citation2014).

The multi-level governance literature describes similar strategies of learning from past experiences, peer learning, and mutual learning strategies for policy transfer (e.g. Hogl Citation2002; Gleeson Citation2003; Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007; Getimis Citation2003; Klein Citation2010; Benson, Jordan, and Huitema Citation2012; Metz and Ingold Citation2014), including learning from practice (e.g. Perrier and Levrat Citation2015). For example, Benson, Jordan, and Huitema (Citation2012) draw on international comparative studies to better understand means for civil society participation. Central in this literature is policy transfer through lessons extracted, defined as a detailed cause-and-effect description of a set of actions that government can consider in the light of experience elsewhere. Various policymaking procedures applied in the context of multi-level governance in the EU and elsewhere for the implementation and transfer of policies are reviewed and analyzed (e.g. Gleeson Citation2003; Maurel Citation2008; Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007; Sabel and Zeitlin Citation2008; Van Wijk, van Bueren and Brömmelstroet Citation2014). Kerber and Eckardt (Citation2007) analyze and discuss the transferability of “best policies,” recognizing the limitations of benchmarking and “best policies” for straightforward policy transfer. In this context, the concept of “thin learning” is used when actors simply “learn how to apply” a particular policy in place, and “thick learning” when actors become increasingly aware of different approaches elsewhere or of their own practices and therefore change their policy orientations. Mutual learning, embodied in two-way exchanges of information, benefiting both partners and based on complementary professional backgrounds is considered a critical dimension of successful partnerships (e.g. Zanon Citation2010; van Ewijk et al. Citation2015).

Learning is considered key for innovation systems in this literature, understood as clusters and networks of organizations, public agents, and private firms collaborating in pursuing innovation and competitiveness (e.g. Aranguren, Larrea, and Wilson Citation2010; Bradford and Wolfe Citation2013; Clar and Sautter Citation2014; Mattes, Huber, and Koehrsen Citation2015; van Ewijk et al. Citation2015). These networks, which may or may not be encouraged by regional policy, can include, among others, firms, universities, laboratories, business incubators, science and industrial parks, and venture capital providers to build a system that generates new ideas about products, processes, organization, and markets. Much of the literature focuses on region-wide networking where cooperation and innovation are stimulated. Regional development policy offers an interesting interplay between the spatial distribution of economic activity and the interaction of key stakeholders across multiple governance levels. In the case of regional development policies (e.g. Paraskevopoulos and Leonardi Citation2004; Benz Citation2012; Bradford and Wolfe Citation2013), knowledge mobilization and innovation take various forms, including state agency partnerships with prominent think-tanks that report on region-specific trends and priorities, working with educational institutions to promote youth entrepreneurship and scientific learning, and positioning regional firms in the global marketplace through the development of community-based strategic plans and international benchmarking of economic performance (van Gerven, Vanhercke, and Gürocak Citation2014).

3.4. Factors that foster or inhibit learning

Both literature strands address and describe factors that hamper, initiate, foster, and also, to some extent, facilitate higher levels of double- and triple-loop learning.

Factors described in governance of adaptation research usually relate to the gaps, barriers, and policy approaches that hamper the flow of knowledge and information and constrain the open dialogue among key stakeholders that facilitate social learning. Baird et al. (Citation2014) argue that governance provides a structure based on tradition and processes for determining how power and responsibility are exercised. In addition, the level of integration or fragmentation of the actors in an organization or a social network, as well as the complexity and differentiation of actors and roles, shape the way actors share and disseminate information and knowledge.

Different authors suggest diverse options to remove barriers or further enhance social and policy learning. Rojas et al. (Citation2009) stress the importance of identifying and involving relevant stakeholders in key research stages and decision making such as designing, implementing, planning, and evaluation. However, because of stakeholders’ power differentials and diverse interests, this is not straightforward. These authors observe that conflict itself can trigger attitudinal change among stakeholders and be a source of institutional learning, if lessons and experiences are well incorporated into decision making and conflict resolution.

Lynch and Brunner (Citation2010) observe that communities coping with El Niño 1997/98 achieved remarkable learning by putting in place institutional arrangements that ensure the integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches, including the decentralization of decision-making processes. In such settings, learning is encouraged if stakeholders have an open and collaborative predisposition.

Several authors underscore the need for better integrated cooperation structures, characterized by the inclusion of non‐governmental stakeholders and governments from different sectors and hierarchical levels to produce and share information needed for learning. Jabeen, Johnson, and Allen (Citation2010) see the need to articulate spontaneous and planned adaptation to better include grassroots experience, knowledge, and coping capacities in governance of adaptation and planning processes, thus encouraging learning.

Huntjens et al. (Citation2011) conclude that better integrated cooperation structures and advanced information management are the key factors leading to higher levels of policy learning in river basin management. They found that advanced information management, characterized by joint/participative information production, a commitment to dealing with uncertainties, broad communication between stakeholders, open and shared information sources, and flexibility and openness to experimentation constitute a prerequisite for facilitating learning processes, building trust, and supporting cooperation.

In the multi-level governance literature, Gerlak and Heikkila (Citation2011) conclude that the factors that most influence the types of learning and knowledge mobilization that takes place are the design and structure of institutional arrangements, the dynamic of the social network, and the technological and functional domains of collective settings. The design or structure of institutional arrangements is widely recognized as playing a role in fostering learning, as well as inhibiting or hampering it (Benson, Jordan, and Huitema Citation2012; Mah and Hills Citation2014). The nature of governance might determine the way institutions and formal and informal networks are formed (Getimis Citation2003), and denser institutional environments exert more powerful constraints on the transfer of lessons and learning (Benson, Jordan, and Huitema Citation2012). Mismatches in coordination between different governance levels and across scales and the related need for vertical integration to ensure knowledge flows and policy learning are underscored (e.g. Aranguren, Larrea, and Wilson Citation2010; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013).

In relation to policy learning, Benson, Jordan, and Huitema (Citation2012) note how political factors strongly affect the way lessons are drawn and transformed into public policy. Political systems must consequently possess “the political, bureaucratic and economic resources to implement the policy” (Dolowitz and Marsh Citation1996, 354, quoted in Benson, Jordan, and Huitema Citation2012, 47). Another structural factor stressed by Benson, Jordan, and Huitema (Citation2012) is the role of political ideologies, political values, or “culture.” Ideological consistencies between countries can be a significant factor for the possibility of cross-country policy learning, as policies appear to transfer more easily between similar political systems and like-minded actors.

The dynamic of the social network determines the frequency and intensity of interactions among individual members and their ability to trust one another and accept new ideas (e.g. Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011; Reed et al. Citation2014). The influence and power of individual leaders or prominent organizations is recognized as relevant for sharing information and knowledge, providing orientations, and shaping the organizational values that frame the acquisition of knowledge and learning; but informal institutions and shadow networks are also effective in integrating different kinds of knowledge and bridging different levels, local to national, and influencing the policy process (e.g. Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013).

The structure and the dynamics of the social network are also highlighted in multi-level governance research addressing innovation systems (e.g. Bradford and Wolfe Citation2013; Clar and Sautter Citation2014). The literature argues for more systemic and integrative approaches where learning is encouraged by regional development policies to integrate firm-level support or infrastructure investments in wider networks to trigger growth or development by leveraging knowledge, talent, and entrepreneurship. In addition, incentives created by competition such as yardstick competition, benchmarking, and the systematization of “best policy frameworks” motivate participants to improve policies. Competition is claimed to contribute to learning because it creates new information and experience in a continuous process of experimentation by competing actors (Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007; Benz Citation2012).

The role of bridging organizations is also stressed by various authors (e.g. Reed et al. Citation2014; Johannessen and Hahn Citation2013) for its facilitation and mediation role to connect local and regional collaboratives in the multi-level natural resource governance structure. Bridging organizations act as intermediaries to support networking and cooperation and can assume organizational responsibilities to provide relief for local participants who are generally time constrained.

In addition, factors from the technological and functional domain, such as the procedures and tools to gather and share information, as well as access to communication and information, may determine the ability of a collective to learn. Some authors recognize the importance of reliable information (Johannessen and Hahn Citation2013). Changes in the social, political, economic, or environmental context might also trigger learning (Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011).

The literature also recognizes that exogenous perturbations can be necessary at times to ignite learning by changing the collective’s goals, values, and assumptions. External information can possess a certain level of uncertainty and ambiguity and therefore test the capacity to learn. Pahl-Wostl et al. (Citation2013) describe how disasters, such as extreme floods, can give rise to public debate and trigger policy responses. At the same time, those disasters reframe policy reflections on the appropriateness of policy and management approaches, challenge the appropriateness of past policies, and produce deeper transformations.

The reviewed studies that integrate multi-level and governance of adaptation (matching both selection criteria) highlight the following elements. Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009), drawing on comparative analyses, identified integrated cooperation structures (including non-governmental stakeholders, governments from different sectors and different hierarchical levels) and advanced information management (including joint/participative information production, consideration of uncertainties, and broad communication) as the key factors leading to higher levels of social and policy learning.

The identification and coordination of state and non-state actors are underpinned as critical to enhance and foster learning (e.g. Pelling et al. Citation2008; Pahl-Wostl Citation2009; Leys and Vanclay Citation2011; Huntjens et al. Citation2011). Networks are largely governed by informal institutions, and both state and non-state actors may participate. The informality and high flexibility in membership makes networks very interesting for processes of learning and change (Pelling et al. Citation2008; Pahl-Wostl Citation2009; Blackmore et al. Citation2016; van Bommel et al. Citation2016). In particular, informal networks may be very flexible in terms of membership and the role and power of actors and connections. They support learning by providing access to new kinds of knowledge and by supporting multiple ways of interpretation.

provides a summary of the major themes emerging from the literature review.

Table 2. Major themes in the reviewed literature.

4. Conceptualizing multi-level learning in the context of climate change governance of adaptation

Returning to the objective of this review – to identify promising directions to conceptualize learning in multi-level governance of adaptation, building on the definitions, methods, processes, and factors assessed in both the multi-level and the governance of adaptation literature – we identify the following key elements.

4.1. Defining multi-level learning

In relation to defining multi-level learning in governance of adaptation, we extract the following elements. In the literature on governance of adaptation, emphasis is placed on learning from stakeholder interactions and deliberation at different levels. The focus is on understanding how climate impacts and risks are distributed and how they are handled by different stakeholders with different backgrounds and interests. The assumed goal is to establish a set of rules and institutions to anticipate and deal with such potential impacts (e.g. McCrum et al. Citation2009; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; van der Wal et al. Citation2014).

In contrast, the multi-level governance literature addresses questions of public policy definition, implementation, and transfer, often through mutual learning in international and federal settings (e.g. Hogl Citation2002; Kerber and Eckardt Citation2007; Getimis Citation2003). The assumed goal here is to ensure effective coordination between and across governance levels.

For the purpose of further research in the arena of governance of adaptation, defining multi-level learning could build on the definitions of policy learning (e.g. Sabatier Citation1988; Bennett and Howlett Citation1992) and social learning (e.g. Reed et al. Citation2010) with a focus on cognitive, normative, and relational learning (Baird et al. Citation2014) between different governance levels. In the context of governance of adaptation, multi-level learning by individuals and institutions at a certain level of governance can be understood in its cognitive, normative, and/or relational dimensions, as the result of interactions between individuals and institutions from different governance levels on policy-relevant aspects of adaptation to climate change. The assumed goal here is to enhance the capacity of individuals and collectives to respond to the challenges posed by climate change.

4.2 Methods for assessing multi-level learning

The multi-level and the governance of adaptation literature recognize the lack of consensus, the constraints, and the gaps in the operationalization of multi-level social and policy learning. Despite the diversity of perspectives and potential entry points, we favor a more systemic approach to the operationalization of multi-level learning in further research, reviewing and assessing the process, performance, capacity, and outcomes of a given governance of adaptation system (e.g. Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011; Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013), underlining the interplay of policy and social learning across governance levels. We would favor qualitative and comparative analysis, based on semi-structured interviews and document and network analysis, to assess relevant multi-level learning processes and outcomes, and to capture the interaction and convergence over time of stakeholder perspectives in particular knowledge and practice domains. In a similar approach to that of Baird et al. (Citation2014), changes in the cognitive, normative, and relational domains of multi-level learning could be assessed on the basis of a set of indicators and metrics that change over time. In addition, a diversity of approaches and methods could be applied to assess convergence of views among different governance actors, including e.g. cultural theory approaches (e.g. Van der Wal et al. Citation2014), Q sorting (e.g. Raadgever, Mostert, and Van De Giesen Citation2008), and discursive approaches for the analysis of documents, focusing on the way in which particular issues or problems are defined, constructed, and framed (e.g. Steele et al. Citation2014).

4.3. Processes of multi-level learning

Both literature branches highlight usual processes of multi-level learning: social learning results from social interactions, and various forms of social and policy learning emerge from the comparison, adoption, and dissemination of policies; and lessons among key stakeholders, peer learning, and learning from other knowledge domains are fundamental learning strategies. However, multi-level learning can also be seen rather as a reflective process of change and transformation (e.g. Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013; Dieleman Citation2013). Effective governance of adaptation can be enhanced by taking stock of actions and experience; reflexive action has been highlighted as a central mechanism of adaptive governance (e.g. Boyd and Osbahr Citation2010; Ison, Collins, and Wallis Citation2015) and experiential learning (e.g. Dieleman Citation2013; Fry and Kolb Citation1979). If this happens as a facilitated, conscious learning cycle, as a result of stakeholder interactions between different levels of governance, it can be an important process of multi-level learning (e.g. Huntjens et al. Citation2011; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013).

4.4. Factors fostering or inhibiting multi-level learning

Factors that foster or inhibit multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation can reside within the structure and dynamics of governance systems, for example, power and legitimacy relations and the inclusion or exclusion of informal groups. The existence of a supportive and learning-friendly institutional environment can also play an important role, including the existence of policy instruments that encourage multi-level learning, the role of cross-level facilitating organizations, or the instauration of reflexive functions across levels.

In addition, and particularly relevant for governance of adaptation, uncertainty and the potential for unexpected changes in the climate system will test the internal capacity and learning ability of multi-level governance systems, thus triggering the role of challenging situations as focusing events to ignite multi-level learning in governance of adaptation.

5. Conclusions

The literature reviewed in the two strands – multi-level governance and climate change governance of adaptation – shows that learning has been considered in the context of climate adaptation and, more recently, in the context of governance of adaptation. However, still only very few scholars address learning in combination with questions of governance of adaptation, and only a limited number in relation to multi-level governance. Despite the growing interest, several researchers have raised critical questions about the state of scholarship emerging at the nexus of learning and governance of adaptation (e.g. Gerlak and Heikkila Citation2011; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013; Baird et al. Citation2014). This literature review contributes to developing a conceptual framework for better understanding multi-level learning in relation to the governance of adaptation, providing an overview of the state-of-the-art of methods to operationalize adaptation learning between governance levels, and identifying promising pathways to encourage and facilitate learning in the context of the governance of adaptation.

Addressing the intersections between these two literature strands is relevant for tackling multi-level governance questions emerging in a global climate adaptation regime. In addition, this research arena would benefit from looking more closely at, and better integrating, the results and models of the literature on policy and social learning. A “learning lens” is needed to guide international multi-level governance of adaptation and policy processes, including the design of global and national institutions that encompass mechanisms for capacity building, technology transfer, and reflection on experiences across governance levels.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adger, W. N., N. W. Arnell, and E. L. Tompkins. 2005. “Successful Adaptation to Climate Change Across Scales.” Global Environmental Change 15 (2): 77–86. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.005.

- Amundsen, H., F. Berglund, and H. Westskog. 2010. “Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation: A Question of Multi-Level Governance?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 28 (2): 276–289. doi:10.1068/c0941.

- Andonova, L. B., M. M. Betsill, and H. Bulkeley. 2009. “Transnational Climate Governance.” Global Environmental Politics 9 (2): 52–73. doi:10.1162/glep.2009.9.2.52.

- Aranguren, M. J., M. Larrea, and J. Wilson. 2010. “Learning from the Local: Governance of Networks for Innovation in the Basque Country.” European Planning Studies 18 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1080/09654310903343526.

- Argyris, C. 1976. “Single-Loop and Double-Loop Models in Research on Decision Making.” Administrative Science Quarterly 21 (3): 363–375. doi:10.2307/2391848.

- Axelsson, R., P. Angelstam, L. Myhrman, S. Sädbom, M. Ivarsson, M. Elbakidze, K. Andersson., et al. 2013. “Evaluation of Multi-Level Social Learning for Sustainable Landscapes: Perspective of a Development Initiative in Bergslagen, Sweden.” Ambio 42 (2):241–253. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0378-y.

- Baird, J., R. Plummer, C. Haug, and D. Huitema. 2014. “Learning Effects of Interactive Decision-Making Processes for Climate Change Adaptation.” Global Environmental Change 27: 51–63. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.019.

- Bandura, A., and N. E. Adams. 1977. “Analysis of Self-Efficacy Theory of Behavioral Change.” Cognitive Therapy and Research 1 (4): 287–310. doi:10.1007/BF01663995.

- Bennett, C. J., and M. Howlett. 1992. “The Lessons of Learning: Reconciling Theories of Policy Learning and Policy Change.” Policy Sciences 25 (3): 275–294. doi:10.1007/BF00138786.

- Benson, D., A. Jordan, and D. Huitema. 2012. “Involving the Public in Catchment Management: An Analysis of the Scope for Learning Lessons from Abroad.” Environmental Policy and Governance 22 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1002/eet.593.

- Benz, A. 2012. “Yardstick Competition and Policy Learning in Multi-Level Systems.” Regional and.” Federal Studies 22 (3): 251–267. doi:10.1080/13597566.2012.688270.

- Berkhout, F., J. Hertin, and D. M. Gann. 2006. “Learning to Adapt: Organisational Adaptation to Climate Change Impacts.” Climatic Change 78 (1): 135–156. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9089-3.

- Blackmore, C. 2014. “Learning to Change Farming and Water Management Practices in Response to the Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainability.” Outlook on Agriculture 43 (3): 173–178. doi:10.5367/oa.2014.0169.

- Blackmore, C., S. van Bommel, A. de Bruin, J. de Vries, L. Westberg, N. Powell, N. Foster, K. Collins, P. P. Roggero, and G. Seddaiu. 2016. “Learning for Transformation of Water Governance: Reflections on Design from the Climate Change Adaptation and Water Governance (CADWAGO) Project.” Water (Switzerland) 8 (11): 510. doi:10.3390/w8110510.

- Borowski, I., J. P. Le Bourhis, C. Pahl-Wostl, and B. Barraqué. 2008. “Spatial Misfit in Participatory River Basin Management: Effects on Social Learning, a Comparative Analysis of German and French Case Studies.” Ecology and Society 13 (1): 7. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267912

- Boyd, E., and H. Osbahr. 2010. “Responses to Climate Change: Exploring Organisational Learning Across Internationally Networked Organisations for Development.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 629–643. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505444.

- Bradford, N., and D. A. Wolfe. 2013. “Governing Regional Economic Development: Innovation Challenges and Policy Learning in Canada.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (2): 331–347. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst006.

- Bulkeley, H. 2001. “Governing Climate Change: The Politics of Risk Society?” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26 (4): 430–447. doi:10.1111/1475-5661.00033.

- Button, C., M. A. A. Mias-Mamonong, B. Barth, and J. Rigg. 2013. “Vulnerability and Resilience to Climate Change in Sorsogon City, the Philippines: Learning from an Ordinary City?” Local Environment 18 (6): 705–722. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.798632.

- Clar, G., and B. Sautter. 2014. “Research Driven Clusters at the Heart of (Trans-) Regional Learning and Priority-Setting Processes: The Case of a Smart Specialisation Strategy of a German ‘Spitzen’ Cluster.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 5 (1): 156–180. doi:10.1007/s13132-014-0180-0.

- Connor, R., and S. Dovers. 2004. Institutional Change for Sustainable Development. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Dieleman, H. 2013. “Organizational Learning for Resilient Cities, Through Realizing Eco-Cultural Innovations.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 171–180. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.027.

- Dolowitz, D., and D. Marsh. 1996. “Who Learns What from Whom: A Review of the Policy Transfer Literature.” Political Studies 44 (2): 343-357. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

- Fry, R., and D. Kolb. 1979. “Experiential Learning Theory and Learning Experiences in Liberal Arts Education.” New Directions for Experiential Learning 6: 79–92.

- Gerlak, A. K., and T. Heikkila. 2011. “Building a Theory of Learning in Collaboratives: Evidence from the Everglades Restoration Program.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (4): 619–644. doi:10.1093/jopart/muq089.

- Getimis, P. 2003. “Improving European Union Regional Policy by Learning from the Past in View of Enlargement.” European Planning Studies 11 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1080/09654310303662.

- Gleeson, B. 2003. “Learning about Regionalism from Europe: ‘Economic Normalisation’ and Beyond.” Australian Geographical Studies 41 (3): 221–236. doi:10.1046/j.1467-8470.2003.00231.x.

- Hall, P. A. 1993. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25 (3): 275–296. doi:10.2307/422246.

- Hogl, K. 2002. “Patterns of Multi-Level Co-Ordination for NFP-Processes: Learning from Problems and Success Stories of European Policy-Making.” Forest Policy and Economics 4 (4): 301–312. doi:10.1016/S1389-9341(02)00072-2.

- Huntjens, P., C. Pahl-Wostl, B. Rihoux, M. Schlüter, Z. Flachner, S. Neto, R. Koskova, C. Dickens, and I. Nabide Kiti. 2011. “Adaptive Water Management and Policy Learning in a Changing Climate: A Formal Comparative Analysis of Eight Water Management Regimes in Europe, Africa and Asia.” Environmental Policy and Governance 21 (3): 145–163. doi:10.1002/eet.571.

- Ison, R. L., K. B. Collins, and P. J. Wallis. 2015. “Institutionalising Social Learning: Towards Systemic and Adaptive Governance.” Environmental Science and Policy 53: 105–117. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.11.002.

- Jabeen, H., C. Johnson, and A. Allen. 2010. “Built-In Resilience: Learning from Grassroots Coping Strategies for Climate Variability.” Environment and Urbanization 22 (2): 415–431. doi:10.1177/0956247810379937.

- Janjua, S., I. Thomas, and D. McEvoy. 2010. “Framing Climate Change Adaptation Learning and Action: The Case of Lahore, Pakistan.” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2 (3): 281–296. doi:10.1108/17568691011063051.

- Johannessen, Å., and T. Hahn. 2013. “Social Learning Towards a More Adaptive Paradigm? Reducing Flood Risk in Kristianstad Municipality, Sweden.” Global Environmental Change 23 (1): 372–381. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.009.

- Kashyap, A. 2004. “Water Governance: Learning by Developing Adaptive Capacity to Incorporate Climate Variability and Change.” Water Science and Technology 49 (7): 141–146.

- Kerber, W., and M. Eckardt. 2007. “Policy Learning in Europe: The Open Method of Co-Ordination and Laboratory Federalism.” Journal of European Public Policy 14 (2): 227–247. doi:10.1080/13501760601122480.

- Klein, I. 2010. “Political Leadership als Partizipationsprozess im Blickfeld eines supranationalen Akteurs: das Aufspüren von Leadership-Qualität der Europäischen Kommission im Konzeptionsprozess des lebenslangen Lernens auf europäischer Ebene.” Osterreichische Zeitschrift Fur Politikwissenschaft 39 (3): 337–350. https://webapp.uibk.ac.at/ojs/index.php/OEZP/article/view/1336/1030

- Leys, A. J., and J. K. Vanclay. 2011. “Social Learning: A Knowledge and Capacity Building Approach for Adaptive Co-Management of Contested Landscapes.” Land Use Policy 28 (3): 574–584. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.11.006.

- Löf, A. 2010. “Exploring Adaptability Through Learning Layers and Learning Loops.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 529–543. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505429.

- Lynch, A. H., and R. D. Brunner. 2010. “Learning from Climate Variability: Adaptive Governance and the Pacific ENSO Applications Center.” Weather, Climate, and Society 2 (4): 311–319. doi:10.1175/2010WCAS1049.1.

- Mah, D. N., and P. R. Hills. 2014. “Policy Learning and Central-Local Relations: A Case Study of the Pricing Policies for Wind Energy in China (from 1994 to 2009).” Environmental Policy and Governance 24 (3): 216–232. doi:10.1002/eet.1639.

- Mattes, J., A. Huber, and J. Koehrsen. 2015. “Energy Transitions in Small-Scale Regions: What We Can Learn from a Regional Innovation Systems Perspective.” Energy Policy 78: 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2014.12.011.

- Maurel, M.-C. 2008. “Local Development Stakeholders and the European Model: Learning the Leader Approach in the New Member States.” Sociologicky Casopis 44 (3): 511–529.

- McCrum, G., K. Blackstock, K. Matthews, M. Rivington, D. Miller, and K. Buchan. 2009. “Adapting to Climate Change in Land Management: The Role of Deliberative Workshops in Enhancing Social Learning.” Environmental Policy and Governance 19 (6): 413–426. doi:10.1002/eet.525.

- Metz, F., and K. Ingold. 2014. “Sustainable Wastewater Management: Is It Possible to Regulate Micropollution in the Future by Learning from the Past? A Policy Analysis.” Sustainability 6 (4): 1992–2012. doi:10.3390/su6041992.

- Nuorteva, P., M. Keskinen, and O. Varis. 2010. “Water, Livelihoods and Climate Change Adaptation in the Tonle Sap Lake Area, Cambodia: Learning from the Past to Understand the Future.” Journal of Water and Climate Change 1 (1): 87–101. doi:10.2166/wcc.2010.010.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. 2009. “A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Adaptive Capacity and Multi-Level Learning Processes in Resource Governance Regimes.” Global Environmental Change 19 (3): 354–365. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., G. Becker, C. Knieper, and J. Sendzimir. 2013. “How Multi-Level Societal Learning Processes Facilitate Transformative Change: A Comparative Case Study Analysis on Flood Management.” Ecology and Society 18 (4): 58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269425

- Paraskevopoulos, C. J., and R. Leonardi. 2004. “Introduction: Adaptational Pressures and Social Learning in European Regional Policy: Cohesion (Greece, Ireland and Portugal) vs. CEE (Hungary, Poland) Countries.” Regional and Federal Studies 14 (3): 315–354. doi:10.1080/1359756042000261342.

- Pelling, M., C. High, J. Dearing, and D. Smith. 2008. “Shadow Spaces for Social Learning: A Relational Understanding of Adaptive Capacity to Climate Change Within Organisations.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (4): 867–884. doi:10.1068/a39148.

- Perrier, B., and N. Levrat. 2015. “Melting Law: Learning from Practice in Transboundary Mountain Regions.” Environmental Science and Policy 49: 32–44. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.12.023.

- Petticrew, M., and G. McCartney. 2011. “Using Systematic Reviews to Separate Scientific from Policy Debate Relevant to Climate Change.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 40 (5): 576–578. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.022.

- Raadgever, G. T., E. Mostert, and N. C. Van De Giesen. 2008. “Identification of Stakeholder Perspectives on Future Flood Management in the Rhine Basin Using Q Methodology.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 12 (4): 1097–1109. doi:10.5194/hess-12-1097-2008.

- Rantala, S., R. Hajjar, and M. Skutsch. 2014. “Multi-Level Governance for Forests and Climate Change: Learning from Southern Mexico.” Forests 5 (12): 3147–3168. doi:10.3390/f5123147.

- Reed, M. G., H. Godmaire, P. Abernethy, and M.-A. Guertin. 2014. “Building a Community of Practice for Sustainability: Strengthening Learning and Collective Action of Canadian Biosphere Reserves Through a National Partnership.” Journal of Environmental Management 145: 230–239. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.06.030.

- Reed, M. S., A. C. Evely, G. Cundill, I. Fazey, J. Glass, A. Laing, J. Newig., et al. 2010. “What Is Social Learning?”. Ecology and Society 15 (4). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268235

- Reid, H. 2016. “Ecosystem- and Community-Based Adaptation: Learning from Community-Based Natural Resource Management.” Climate and Development 8 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1080/17565529.2015.1034233.

- Rodela, R. 2011. “Social Learning and Natural Resource Management: The Emergence of Three Research Perspectives.” Ecology and Society 16 (4): 30. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04554-160430

- Rodela, R., G. Cundill, and A. E. J. Wals. 2012. “An Analysis of the Methodological Underpinnings of Social Learning Research in Natural Resource Management.” Ecological Economics 77: 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.032.

- Rojas, A., L. Magzul, G. P. Marchildon, and B. Reyes. 2009. “The Oldman River Dam Conflict: Adaptation and Institutional Learning.” Prairie Forum 34 (1): 235–260.

- Sabatier, P. A. 1988. “An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy‐Oriented Learning Therein.” Policy Sciences 21 (2–3): 129–168. doi:10.1007/BF00136406.

- Sabel, C. F., and J. Zeitlin. 2008. “Learning from Difference: The New Architecture of Experimentalist Governance in the EU.” European Law Journal 14 (3): 271–327. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0386.2008.00415.x.

- Schout, A. 2009. “Organizational Learning in the EU’s Multi-Level Governance System.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (8): 1124–1144. doi:10.1080/13501760903332613.

- Shaw, A., and P. Kristjanson. 2014. “A Catalyst Toward Sustainability? Exploring Social Learning and Social Differentiation Approaches with the Agricultural Poor.” Sustainability 6 (5): 2685–2717. doi:10.3390/su6052685.

- Siebenhüner, B., R. Rodela, and F. Ecker. 2016. “Social Learning Research in Ecological Economics: A Survey.” Environmental Science and Policy 55: 116–126. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.09.010.

- Silver, J., C. McEwan, L. Petrella, and H. Baguian. 2013. “Climate Change, Urban Vulnerability and Development in Saint-Louis and Bobo-Dioulasso: Learning from Across Two West African Cities.” Local Environment 18 (6): 663–677. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.807787.

- Steele, W., I. Sporne, P. Dale, S. Shearer, L. Singh-Peterson, S. Serrao-Neumann, F. Crick, D. L. Choy, and L. Eslami-Andargoli. 2014. “Learning from Cross-Border Arrangements to Support Climate Change Adaptation in Australia.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57 (5): 682–703. doi:10.1080/09640568.2013.763771.

- Thapa, B., C. Scott, P. Wester, and R. Varady. 2016. “Towards Characterizing the Adaptive Capacity of Farmer-Managed Irrigation Systems: Learnings from Nepal.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 21: 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2016.10.005.

- Thompson, M., R. Ellis, and A. Wildavsky. 1990. Cultural Theory. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Tschakert, P., and K. Dietrich. 2010. “Anticipatory Learning for Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience.” Ecology and Society 15 (2): 11. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss2/art11/

- Van Bommel, S., C. Blackmore, N. Foster, and J. de Vries. 2016. “Performing and Orchestrating Governance Learning for Systemic Transformation in Practice for Climate Change Adaptation.” Outlook on Agriculture 45 (4): 231–237. doi:10.1177/0030727016675692.

- Van der Wal, M., J. De Kraker, A. Offermans, C. Kroeze, P. A. Kirschner, and M. van Ittersum. 2014. “Measuring Social Learning in Participatory Approaches to Natural Resource Management.” Environmental Policy and Governance 24 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1002/eet.1627.

- Van Ewijk, E., I. Baud, M. Bontenbal, M. Hordijk, P. Van Lindert, G. Nijenhuis, and G. Van Westen. 2015. “Capacity Development or New Learning Spaces Through Municipal International Cooperation: Policy Mobility at Work?” Urban Studies 52 (4): 756–774. doi:10.1177/0042098014528057.

- Van Gerven, M., B. Vanhercke, and S. Gürocak. 2014. “Policy Learning, Aid Conditionality or Domestic Politics? the Europeanization of Dutch and Spanish Activation Policies Through the European Social Fund.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (4): 509–527. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.862175.

- Van Wijk, M., E. van Bueren, and M. Te Brömmelstroet. 2014. “Governing Structures for Airport Regions: Learning from the Rise and Fall of the ‘Bestuursforum’ in the Schiphol Airport Region.” Transport Policy 36: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.08.006.

- Vella, K., N. Sipe, A. Dale, and B. Taylor. 2015. “Not Learning from the Past: Adaptive Governance Challenges for Australian Natural Resource Management.” Geographical Research 53 (4): 379–392. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12115.

- Vink, M. J., A. Dewulf, and C. Termeer. 2013. “The Role of Knowledge and Power in Climate Change Governance of Adaptation: A Systematic Literature Review.” Ecology and Society 18 (4): 46. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05897-180446

- Yuthas, K., J. F. Dillard, and R. K. Rogers. 2004. “Beyond Agency and Structure: Triple-Loop Learning.” Journal of Business Ethics 51 (2): 229–243. doi:10.1023/B:BUSI.0000033616.14852.82.

- Zanon, B. 2010. “Planning Small Regions in a Larger Europe: Spatial Planning as a Learning Process for Sustainable Local Development.” European Planning Studies 18 (12): 2049–2072. doi:10.1080/09654313.2010.515822.