Abstract

Land grabbing results in social impacts, injustice, conflict and displacement of smallholders. We use an environmental justice framework to analyse land grabbing and actions taken by local communities (resistance, protest, and proactive organisation). Qualitative research investigating land grabbing for tree plantations and agriculture (primarily soy) was undertaken in Argentina. We found that pre-existing local vulnerabilities tended to result in people acquiescing rather than resisting land grabs. Local people considered existing injustices to be more pressing than land grabbing. Locals tacitly accepted injustice resulting in communities becoming displaced, fenced-in, or evicted. Consequently, already-vulnerable people continue to live in unhealthy conditions, insecure tenure situations, and bear a disproportionate social and environmental burden. More attention should be given to pre-existing vulnerabilities and to improving the wellbeing of people affected by land grabs. Analysing land grabbing from an environmental justice perspective contributes to understanding the deeper reasons about why, where and how land grabbing occurs.

1. Introduction

Rural areas in Argentina are experiencing considerable spatial change, with the restructuring of places, livelihoods and landscapes (Jara and Paz Citation2013). This reorganisation is occurring partly because of investments in agriculture, agroforestry, mining, conservation and land speculation (Borras et al. Citation2012; Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013). These land investments are primarily being undertaken by foreign companies, but also by domestic companies, sometimes with foreign capital (Jara and Paz Citation2013; Murmis and Murmis Citation2012). This land grabbing results in a change in land use from family farming to industrial tree monoculture and intensive agriculture (Busscher, Parra, and Vanclay Citation2018). Borras et al. (Citation2012, 405) stated that land grabbing is “the capturing of control of relatively vast tracts of land and other natural resources through a variety of mechanisms and forms involving large-scale capital that often shifts resource use to that of extraction, whether for international or domestic purposes”.

Land grabs typically result in the detriment of local rural populations, and have led to tenure insecurity, competing claims over land, resistance, protest, and violence (Brent Citation2015; Gutiérrez and Gonzalez Citation2016; Reboratti Citation2008). A background reason for this contestation is the large extent of informal land use in Argentina (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013). Another issue is differences in the meaning of land between investors and local people (Escobar Citation2000; Stanley Citation2009). For many rural people, especially Indigenous peoples, land is essential for the continuation of their livelihood activities and for the reproduction of their social, cultural and spiritual practices (Hanna et al. Citation2016a; Pilgrim and Pretty Citation2011). However, this strong connection to land is not usually considered by investors or the state (Matulis Citation2014; Zoomers Citation2010).

Market-driven land investments can have serious consequences, including social and environmental impacts and human rights violations (Escobar Citation2000; Vanclay Citation2017; Veltmeyer and Petras Citation2014). These include the lack of respect for customary and informal land tenure, the lack of influence of local communities in decision-making, diminishing resource access, and insecurity, as land grabbing involves dispossession and violence (Garcia-Lopez and Arizpe Citation2010; Grajales Citation2011; Hanna et al. Citation2016a; Lapegna Citation2012). Many countries in the Global South bear the “disproportionate negative environmental and social cost of global production” (Carruthers Citation2008, 2). This burden is directly related to (over)consumption in many Western societies (Martínez-Alier Citation2012; McSweeney et al. Citation2018). Differences in land prices, wages, legal frameworks, regulatory contexts and commercial opportunities make these countries attractive to companies, thus exacerbating inequality (Jara and Paz Citation2013; Murmis and Murmis Citation2012).

The conflicts arising from these land investments and the inequities created within and between countries are now being analysed and theorised by environmental justice scholars. When it originally emerged in the late 1980s, the field of environmental justice studies primarily focussed on the disproportionate environmental burden of land-use activities on certain racial, vulnerable and marginalised groups in rich countries (Bullard Citation1996). Subsequently, the field expanded to give greater consideration to gender (Schlosberg Citation2007), the Global South (Schlosberg Citation2004), and to the hierarchies and inequalities within disadvantaged groups (Parra and Moulaert Citation2016). New insights have shifted the focus from only considering impacts on humans to also including impacts on the environment (Agyeman et al. Citation2016). This shift has also led to analysing the importance of a healthy environment for people (Lakes, Brückner, and Krämer Citation2014; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010).

Drawing on Schlosberg (Citation2013), we define environmental injustice as the procedures, processes and systems that lead to the unequal distribution of the burdens, harms and risks associated with policies, plans, programmes and projects that impact on the environment. To understand environmental injustice, many scholars have focussed on protest movements, collaborations between movements, and on the processes, claims and outcomes achieved by these movements (Carruthers Citation2008; Sebastien Citation2017; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010; Urkidi and Walter Citation2011). The environmental justice field has shown how socially transformative action can reduce environmental injustice, increase wellbeing in communities, and build social capital (Hanna et al. Citation2016b; Mehmood and Parra Citation2013). Drawing on thinkers such as Arturo Escobar, Paolo Freire, Ivan Illich, Boaventura de Sousa Santos and others, we define socially transformative action as a wide variety of forms and processes of proactive organisation that seek redress for injustice and/or that strive for a better world. The field of environmental justice has stressed the importance of socially transformative action to achieve sustainability (Martínez-Alier Citation2012).

There are many people who do not overtly resist while experiencing environmental injustice, but use a wide range of passive resistance strategies (Hanna et al. Citation2016b; Leguizamón Citation2016; Scott Citation1985). An explanation for this apparent lack of active response may be their shortage of financial resources or local hardships, given that political engagement can be resource and/or time intensive and may not lead to any significant outcome (Piñeiro, Rhodes-Purdy, and Rosenblatt Citation2016). However, populist governments, such as many of the former governments in Argentina, can incentivise political engagement as a means of co-opting local people (Piñeiro, Rhodes-Purdy, and Rosenblatt Citation2016). Alternatively, the awakening environmental and political awareness facilitated by land-use change can trigger political action (Hanna, Langdon and Vanclay Citation2016; Kollmuss and Agyeman Citation2002; Narain Citation2014; Sebastien Citation2017). We consider that the environmental justice literature does not sufficiently examine the preconditions necessary to initiate socially transformative action. Therefore, we seek to explore the factors that hinder the ability of communities to address injustice in the context of land grabbing in Argentina.

Although some scholars (Carruthers Citation2008; Coenen and Halfacre Citation2003; Cook and Swyngedouw Citation2012; Lakes, Brückner, and Krämer Citation2014; Lapegna Citation2016; Schlosberg Citation2013; Walker Citation2009) have highlighted the importance of studying pre-existing inequalities, hidden processes, and place-based specificities, this has still not become common in the environmental justice field and in the land grabbing literature. Therefore, the main questions underpinning our research were: (1) How does the environmental justice field help us to understand the socio-environmental conflicts created by land grabbing? (2) What are the social processes and mechanisms that enable or constrain socially transformative action? and (3) How does land grabbing force people to change or adapt their livelihoods? Environmental justice is used as an analytical lens to examine how land grabbing has initiated different types of environmental injustice. We bring in Nixon’s (Citation2011) ideas about violence to assist understanding of the types of injustice faced by local people. We use material from two case studies in Argentina: agricultural expansion in the Province of Santiago del Estero; and tree plantation expansion in the Province of Corrientes. We conducted participant observation and in-depth interviews in local communities affected by land grabbing. These mestizo communities experience severe conditions, inadequate essential public services, and a general neglect by the national government.

Our main conclusions are that, in the face of advancing agribusiness, in both cases, the ability of local people to maintain their way of living was under threat. Under the influence of the neoliberalist ideology that has existed in Argentina since about the mid-1990s (Teubal Citation2004), most rural communities are now in a state of social deprivation, with little government investment in roads, education, healthcare, or basic services such as water and electricity (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013; Neiff Citation2004). This pre-existing social deprivation and the impoverished conditions in which communities live exacerbate the severity of the impacts of land grabbing. However, people face a range of issues that are of greater concern to them than the impacts of land grabbing, such as meeting basic needs, having reasonable working conditions, and adequate access to clean water, electricity, education and healthcare. Instead of resisting, people tended to adapt their livelihoods and accommodate the environmental injustices resulting from land grabbing. This acquiescence assists in the spread of land grabbing. The deprived situation in which people live means that people have less opportunity to access civil society groups to advance socially transformative actions. Constraints on the dissemination of their environmental justice claims often relate to historical, geographical, judicial, financial, political and social factors. To address these constraints, in the conclusion to our paper we provide some policy recommendations.

2. Environmental injustice, resistance, protest and socially transformative action

Socially transformative action, protest and resistance in response to environmental injustice come in many forms and range from overt, formally organised group activities to covert informal ‘weapons of the weak’ (Hanna et al. Citation2016b; Scott Citation1985; Urkidi and Walter Citation2011). People may resist current or future environmental burdens, harms and risks. People may also desire redress for past harms in order to achieve closure or to be able to move forward (Hanna, Langdon, and Vanclay Citation2016). Environmental justice claims tend to arise: when the environment in which people live is irreversibly modified in its quality or use value; when access to common property resources is affected; when certain groups are not considered or do not benefit fairly; or when the ability of people to achieve their full potential capabilities is constrained because of changes in control or use of land (Bullard Citation1996; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010).

Local environmental justice movements tend to work on local issues, the resolution of which requires action at the global as well as the local level (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Hanna et al. Citation2016b). These movements emphasise that environmental harms should not be situated in areas close to people, especially those who are more vulnerable (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010). Environmental justice movements are also active in initiating debates about systemic change. For example, the agro-ecología (agro-ecological) movement in Latin America aims to transform agriculture from its current strategy of large industrial monocultures to a more environmentally and socially just system benefitting small family farmers (Altieri and Toledo Citation2011).

Solidarity between organisations and scale-jumping (i.e. moving between spheres or levels of action from the local to the global) are important strategies to strengthen social and environmental campaigns and increase their likelihood of success (Cook and Swyngedouw Citation2012; Hanna et al. Citation2016b; Parra Citation2010; Urkidi and Walter Citation2011). This is demonstrated by the Unión Asamblea Ciudadana (Citizens Assembly Union) in Argentina, which unites and supports local movements protesting against environmental conflicts. Within the Unión, learning is achieved through the sharing of experiences and tactics. The strength of solidarity is communicated via social media and helps in spreading messages of resistance. Urkidi and Walter (Citation2011) showed how local environmental justice movements in Argentina have successfully engaged with national and international networks to pursue their claims.

Covert weapons of the weak are tactics that relatively powerless people can use, such as “foot dragging, dissimulation, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance” to resist the policies, plans, programmes and projects they oppose (Scott Citation1985, 29). These people may have little option other than to stay within their communities, where they are often constrained in practicing overt action, requiring them to accommodate to the injustice they experience (Lapegna Citation2016). Several factors limit the ability of local people to engage in overt resistance, including limited resources, a lack of access to information and external contacts, and uncertainty about responsibility and accountability for environmental hazards (Coenen and Halfacre Citation2003; Lapegna Citation2016). In our opinion, the factors that enable or constrain people in seeking resolution of their environmental justice issues are not sufficiently understood.

Overt resistance has many characteristics and can lead to a wide range of outcomes. Resistance and other social movements have an important role to play in contributing to more sustainable and just societies (Hanna et al. Citation2016b; Martínez-Alier Citation2012; Parra and Walsh Citation2016; Sebastien Citation2017). Primarily, they provide hope and the prospect of a more just society that values nature (Martínez-Alier Citation2012). Protest actions can increase community wellbeing, social capital and people’s appreciation of their local environment (Hanna et al. Citation2014, Citation2016b; Imperiale and Vanclay Citation2016; Sebastien Citation2017). Therefore, studying the reasons why people are limited in their ability to resist or to initiate socially transformative action is important, especially in land grabbing where social and environmental impacts are severe.

3. Quick overview of the field of environmental justice studies

Since the concept of environmental justice emerged in the 1980s in the United States, it has evolved considerably (Agyeman et al. Citation2016). The field has been used and shaped by environmental justice groups, social justice groups, civil society organisations, academics, politicians and practitioners (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010; Velicu and Kaika Citation2017; Walker Citation2009). How the concept is used or interpreted depends on the historical and geographical characteristics of specific localities (Velicu and Kaika Citation2017). According to key writers, the main topics addressed in this field are: the unequal distribution of harms; the extent of participation in decision-making; procedural justice issues; recognition of, and respect for, local people and local cultures and the Capability Approach (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Bullard Citation1996; Carruthers Citation2008; Schlosberg Citation2004; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010). Although additional topics have been suggested (Velicu and Kaika Citation2017), this list provides a basis by which socio-environmental issues, including land grabbing, can be analysed, and we use these as the themes addressed in this paper. They are described in more detail immediately below.

The unequal distribution of environmental harms is the defining element of environmental justice. Problems around maldistribution are often localised issues that make certain marginalised groups and the most vulnerable people suffer disproportionately by inequitable exposure to environmental injustice. These groups typically include Indigenous communities, communities of colour, communities in poverty, immigrants, women, the elderly and very young children (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Laurian and Funderburg Citation2014; Walker Citation2009). The distributional issues are initiated by, and result in, disrespect, discrimination, disempowerment, disintegration, despair and despondency (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010; Tschakert Citation2010). Environmental justice pays attention to intra-generational and inter-generational distribution, focussing on safeguarding current and future environmental sustainability (WCED Citation1987).

Participation refers to the ability of people to have a say in decision-making processes about the society and economy in general, and about specific issues, such as a new agribusiness operation in their neighbourhood (Dare, Schirmer, and Vanclay Citation2014). Ideally, participation should be fully and effectively implemented as normal procedure and as best represented by the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent, which arguably applies to Indigenous communities giving them the opportunity to withhold or consent to proposed projects (Hanna and Vanclay Citation2013). However, participatory practices as implemented have often been woefully inadequate, partly because people do not have equal power in the process, and are sometimes not considered as being equal (Cooke and Kothari Citation2001; Velicu and Kaika Citation2017). Local resistance and protest movements are increasingly refusing to participate in the limited consultation processes that are typically undertaken for projects that acquire land (Hanna et al. Citation2014; Kaika Citation2017; Schlosberg Citation2013). Another factor influencing the extent of participation enabled by entities implementing projects is the perceived risks associated with community involvement (Gallagher and Jackson Citation2008).

Procedural justice refers to the way procedures are implemented in practice. They should be applied in a manner consistent with the principles of transparency, accountability, equality, non-discrimination, and inclusion, and require that information about all possible environmental harms and risks be provided in a transparent, accessible way and in languages appropriate to the impacted peoples (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Coenen and Halfacre Citation2003; Laurian and Funderburg Citation2014; Schlosberg Citation2004).

The failure to respect other cultures, their ways of living and thinking, and to appreciate their dynamic nature are also forms of environmental injustice. Sometimes, the connection people have with the places they inhabit is completely ignored by companies and/or the state. Other times, the perceived disconnection of these people with traditional ways of living is used as a justification to foist unwanted development on them. Modernisation and exploitative modes of development are deemed more important than the wellbeing of local people (see Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Nixon Citation2011; Parra and Moulaert Citation2016).

Many environmental justice scholars use the Capability Approach (Schlosberg Citation2013; Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010; Tschakert Citation2010), which was developed by Sen (Citation1985) and Nussbaum and Sen (Citation1993). The Capability Approach is a framework to identify and enhance individual wellbeing, social arrangements, and the locational factors that enable people to live their life to its full potential (Sen Citation1985). These factors include freedom of choice, opportunities linked with this freedom, and the ability to pursue opportunities (Nussbaum and Sen Citation1993). Environmental justice scholars are interested in this approach because changes in environmental quality affect people’s livelihoods and ultimately their wellbeing, thus changing the conditions that allow people to develop and pursue their capabilities (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010).

4. Land grabbing as environmental injustice

This section describes the phenomenon of increasing land investments and its consequences for people and places. Land grabbing is the capturing of control of relatively vast tracts of land and other natural resources through a variety of mechanisms and forms involving large-scale capital that often shifts resource use to that of extraction, whether for international or domestic purposes (Borras et al. Citation2012, 405). Land grabbing is facilitated by unclear land tenure arrangements and it in itself leads to competing claims over land (Habra and Franzzini Citation2016). Land grabbing primarily impacts smallholders (Banerjee Citation2015). It leads to a wide range of outcomes, including various forms of resistance, protest, rural-to-urban migration (Jara, Gil Villanueva, and Moyano Citation2016), communities that are surrounded or cut off (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Habra and Franzzini Citation2016; Narain Citation2014), displacement and resettlement (Vanclay Citation2017), and, in the worst cases, to the violent dispossession and forced eviction of people (Grajales Citation2011).

Land grabbing changes the normal life rhythm of communities (Lapegna Citation2016). Local people are typically rooted in the places where they live, and the disruption caused by land grabbing can be momentous (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015; Grajales Citation2011; Narain Citation2014). This situation is unfair in that companies are ‘globally mobile’, whereas local people are fixed in place and have few alternatives for making their living (Desmarais Citation2002). Prior disadvantage and the need for local people to adapt to land-use change mean that they may not be able to organise or resist (Lapegna Citation2016). Land-use change may even result in communal conflict, as desires and interests in communities are diverse (Hall et al. Citation2015). The disadvantages they experience include geographical isolation, financial constraints, and limited knowledge about legal rights and the judicial system (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Habra and Franzzini Citation2016). These place-based specificities are not sufficiently addressed in the field of environmental justice studies (Schlosberg Citation2004; Citation2013).

5. The violence inherent within land grabbing

Nixon (Citation2011) distinguished between actual, structural, and slow violence. All three types occur in conjunction with land grabbing. Actual violence is event focussed, time bound and body bound (Nixon Citation2011, 3). Around the world, every year, thousands of rural people and land activists are attacked or criminalised, and hundreds are murdered because of their actions against land grabbing (Global Witness Citation2016; GRAIN Citation2016; Grajales Citation2011; Jara and Paz Citation2013; Lapegna Citation2012; Sassen Citation2017; Stover Citation2016).

Structural violence refers to the institutionalisation of a system in which there is an inherent failure to ensure that people’s basic human needs are met (Galtung Citation1969). Structural violence is reflected in the high morbidity and mortality rates of certain vulnerable groups (Galtung Citation1969; Ho Citation2007). It is an inadvertent outcome of neoliberalism and other processes, with local people not benefiting from the corporate-oriented global economic model (see Desmarais Citation2002). While this type of violence is covert, it can be a catalyst for actual overt violence (Nixon Citation2011).

Slow violence is understood as the long-term, insidious negative effects of human activities on other human beings or the environment, especially the negative consequences that are not known, are invisible, or overlooked (Nixon Citation2011). In the context of land grabbing, first, people lose access to land. However, the subsequent processes and outcomes (e.g. deforestation and land-use change) cause other negative effects in the present (e.g. displacement, impoverishment) and future (e.g. climate change) (Cernea Citation1997; Malhi et al. Citation2008). A specific example of slow violence is the cumulative effects on the health of workers in agricultural industries (Leguizamón Citation2016; Ogut et al. Citation2015; Séralini et al. Citation2013). Another example is reduced water availability, one of the consequences of tree plantations, which causes major livelihood impacts and consequent hardships on local people (Overbeek, Kröger, and Gerber Citation2012). The focus on slow violence is particularly relevant to the field of environmental justice because slow violence is a major threat multiplier; it can fuel long-term, proliferating conflicts in situations where the conditions for sustaining life become increasingly, but gradually, degraded (Nixon Citation2011, 3). Unfortunately, in land investments, there is a lack of attention given to long-term issues and cumulative impacts (i.e. slow violence) (Jijelava and Vanclay Citation2017; Vanclay Citation2017). Violence, above all environmental violence, needs to be seen–and deeply considered–as a contest not only over space, or bodies, or labour, or resources, but also over time (Nixon Citation2011, 8).

The connections between land grabbing and actual, structural and slow violence are described by McSweeney et al. (Citation2018) in the context of drug trafficking in Honduras. Sparsely populated, remote areas in Honduras are used as transit hubs for cocaine, bringing corruption and violence to the land market. Here, communities that are in a state of poverty and neglect are coerced to sell their land, including through the use of actual violence. Because of the state of neglect, communities are vulnerable to criminal enticement and largesse (McSweeney et al. Citation2018). Apart from actual violence, the narcos also exploit family vulnerabilities making them more willing to sell-off land. Collectively, the future opportunities of communities are diminished to such an extent that they are no longer viable, which could be seen as slow violence. Actual violence for land grabbing is more likely to occur in a context where structural violence is rife. We consider that slow violence derives from extreme poverty and makes rural communities vulnerable to land grabs.

6. Land grabbing in Argentina

In Argentina, there are three types of actor who have a key role in land grabbing, especially in the agricultural sector (Murmis and Murmis Citation2012). First and most obviously are the companies (foreign or domestic) that buy or lease land. The second type comprises the rural elite (i.e. the historic formal title holders or landed gentry), who are typically absentee land owners not actively using the land. The demand for land has increased land values so that this rural elite, who were previously happy to retain their land holdings, now aspire to sell it off (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016). Third, the state plays an important role in facilitating land grabbing by, for example, lowering entry barriers for foreign investors, privatizing public land and authorising deforestation (Costantino Citation2016).

According to the NGO, GRAIN (Citation2012), foreigners have acquired one million hectares of land in Argentina. It is estimated that around nine million hectares are subject to some sort of land dispute, affecting over 63,000 people (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013). The Civil Code (Código Civil y Comercial de la Nación) recognises formal title holders and the informal use of land. In Argentina, many historic formal title holders have not been actively using their land and, as a result, this land has been occupied and/or utilised by people from neighbouring communities and/or by migrants from further afield. Articles 4,015 and 4,016 of the Civil Code and Article 24 of Law 14.159 stipulate that informal land users can initiate a legal procedure (commonly known as Ley Veinteañal) to gain formal title to a piece of land after they have lived there continuously for a minimum of 20 years, even if there was previously assigned formal title over that land (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016). Communities can also start this legal procedure when they possess informal use rights on public land. However, this Ley Veinteañal procedure is not well known among rural people. The steps to start this procedure are relatively costly and time-consuming, which is a disincentive to rural people. The judicial process of claiming rights over public land on the basis of the Ley Veinteañal can take up to 20 years in extreme cases. The steps include having to take GPS coordinates of the land. Furthermore, even if all the necessary steps are taken, implementation of this law is not always undertaken properly by the state (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Habra and Franzzini Citation2016; Jara, Gil Villanueva, and Moyano Citation2016). The underutilisation of land by historic formal title holders and its occupation/utilisation by others leads to contestation. This tension tends to persist for many years, creating long-term insecurity (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013; Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013).

Historically, the uncertainty over land tenure was perhaps not a major issue for most stakeholders. However, the contemporary demand for land driven by land grabbing has made it a significant issue. Historic formal title holders who may previously not have been too worried about losing their land by Ley Veinteañal claims are now very concerned to protect their ownership rights so that they can then sell (or lease) their land to the land grabbers. Thus, to thwart the Ley Veinteañal procedure, they have had to reoccupy/utilise the land themselves, and have had to exclude the squatters from their land. Sometimes they have sold their land, with the informal users still in place, leaving the land investor with the issue. In the Argentinian context, the sale of land and a change in land title does not extinguish pre-existing claims to the land, such as might be generated by the Ley Veinteañal procedure (Personal communication with government official, 2017).

The tactics frequently used by historic formal title holders and land investors to pressure people to leave the land include: menacing actions, such as with bulldozers or other equipment; the use of private security forces; intimidatory behaviour and harassment, such as setting houses on fire; the illegal or unauthorised occupation and/or use of land by the investors; and the bribing of local police and judicial staff to facilitate their complicity (Jara and Paz Citation2013), all of which are breaches of human rights (van der Ploeg and Vanclay Citation2017). At the national level, there are laws intended to protect people against expulsion and to protect Indigenous peoples (i.e. Law 26.160) (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013). However, these are not adequate to provide the necessary protections, especially in the context of the state being complicit in the land grabbing (which is part of its national development strategy) (Jara and Paz Citation2013; Costantino Citation2016).

7. Methodology

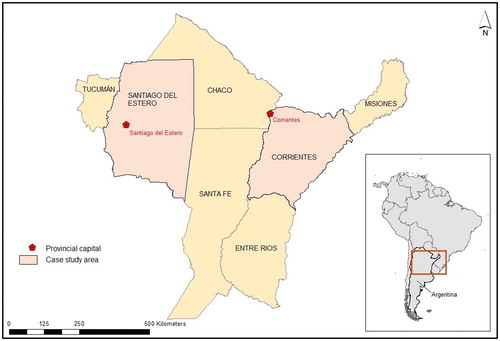

Land-use changes and conflicts in Argentina were studied by examining two rural regions (i.e. case studies), the Provinces of Santiago del Estero and Corrientes (see ). These regions have been subject to substantial land investment. In Santiago del Estero, there has been massive expansion of industrial agriculture, especially soy, because of a 1996 national law allowing GMOs (Goldfarb and Zoomers Citation2013). A shift in agricultural production trends has also led to a major increase in feedlotting and extensive livestock farming in this province (Jara and Paz Citation2013). In Corrientes, there has been major expansion of industrial tree plantations (Slutzky Citation2014). Expansion of industrial agriculture and tree plantations has been particularly problematic for local communities and has led to much conflict over land use and concern about security of land tenure (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013). In the two provinces studied, many smallholders reside in situations of informal title or precarious land tenure (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013; Slutzky Citation2014). The expansion of industrial agriculture and plantation forestry typically ousts people off the land and/or severely disrupts their livelihoods (Goldfarb and van der Haar Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013; Lapegna Citation2016).

The insights presented in this paper are based on a total of 10 months fieldwork carried out in Argentina between 2011 and 2016. In 2011 (October–December), fieldwork was conducted with the assistance of a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) in Santiago del Estero. The purpose of this NGO is to assist communities to enhance their viability and vitality, and it provides support in relation to land conflicts. Collaboration with this NGO provided a broad understanding of the political, judicial and social issues relating to land grabbing. In 2014, two months (November–December) were spent in Argentina undertaking preliminary investigations and gaining an overarching perspective, with a couple of weeks in Buenos Aires interviewing key informants. In 2015 (April–July), fieldwork was primarily conducted in Corrientes. In 2016 (April–May), research was primarily conducted in Santiago del Estero. During these periods, supportive information was also gained from trips to other provinces: Misiones, Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Jujuy, Santa Fe and Tucumán.

While the overarching project looked at the socio-environmental consequences of land acquisition in Argentina, the aim of this particular paper was to consider the potential value of an environmental justice perspective in analysing land acquisition processes. To achieve this, a multi-methods approach was adopted, using a wide range of social research methods, including: document analysis (especially of documents pertaining to the case study areas); analysis of media reports; in-depth interviews with key informants; and participant observation with field visits and attendance at village meetings where land-use issues and land tenure were discussed. For the overarching project, some 70 interviews were carried out. For this paper, we drew on the participant observation and interviews that related specifically to the two case study regions. These 47 interviews included 10 interviews with local residents, 10 with representatives of NGOs, 7 with representatives of companies, 8 with other researchers studying land grabbing and 12 interviews with government officials. The purpose of these interviews was to gain a good in-depth understanding of the characteristics and specificities of the study area, land grabbing practices, adaptation strategies, obstacles to resistance and policies relating to land-use change. All interviews were conducted by the lead author in Spanish. For some interviews, the second author was also present.

The quotes used in this paper have been translated into English by the authors. In translating the quotes, we have ensured that the inherent or implied meaning was preserved, rather than necessarily providing the exact literal translation. Informed consent was gained for all interviews, although usually in an informal way (Vanclay, Baines, and Taylor Citation2013). Only about half of the interviews could be recorded because of people’s concerns about this, although they were happy to talk to the interviewer(s) and for interview notes to be taken. Interviews that were recorded were transcribed. After each interview, especially those not recorded, additional notes were made regarding any significant observations or comments made. In some interviews, participants presented photos, documents or other materials. Where appropriate, the researchers took copies of these, made photographs, or took notes about them.

The lead author attended a number of meetings relating to tenure insecurity held in different villages. One was a workshop for members of a community facing eviction. It was organised by a group of students from the University of Misiones, who had arranged for a lawyer who specialised in land tenure to be present and give general advice. The aim of this workshop was to assist the community to formalise their land tenure and thus avert eviction. Other meetings attended included those involving local communities, the church and NGO workers in which another lawyer informed people about their land rights. A further example in Santiago del Estero was attendance at a meeting of ‘Mesa Provincial de Tierra’ (Provincial Roundtable for Land Issues), a formal mechanism that gathers together the different actors involved in land-use conflicts. Field visits included visiting soy and tree plantations accompanied by the owners. All research activities contributed to gaining an integrated view of the implications of land grabbing and the local realities surrounding this.

The data for analysis comprised the interview transcripts, relevant documents, field notes, and our deliberations on these materials. Analysis was undertaken by reviewing all materials many times and distilling the key issues relating to land grabbing and environmental justice issues. One limitation of this research is that the lead researcher was only able to visit communities that had external connections, as she was typically introduced to these communities through gatekeepers, such as various NGOs in Argentina. This may have influenced the findings, because the research only covers communities that are reasonably well-connected. Other limitations related to language nuance, given the strong regional dialects in some of the rural villages. Statements about specific facts, events or happenings were cross-checked or triangulated as far as possible.

8. Description of the two case study regions

8.1. Agricultural production in Santiago del Estero

The key products of Santiago del Estero are grain, maize and soy (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos Citation2016; Jara and Paz Citation2013). Argentina is currently the world’s third largest producer of soy, with rapid expansion taking place. Nationally, soy covered 19.8 million hectares in 2014 (Leguizamón Citation2016), up from 5 million in 1990 (Ministry of Agroindustry Citation2017). Although the cultivation of soy primarily takes place in the provinces of Buenos Aires and Córdoba (Jara and Paz Citation2013), the area sown has rapidly increased in Santiago del Estero from 72,500 hectares in 1990 to just under 1 million hectares in 2014 (Ministry of Agroindustry Citation2017). Further expansion of soy in Argentina and Santiago del Estero is likely, as the demand for soy is predicted to increase (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Citation2010).

Expansion of soy cultivation in Buenos Aires and Córdoba has led to the relocation of livestock industries (i.e. feedlots) from these provinces to Santiago del Estero, which now has over 1 million head of cattle, resulting in odour emissions, pollution, land conflict and deforestation (interview government official, 2016; see also Boletta et al. Citation2006; Leguizamón Citation2014).

Expansion of agricultural industries is accompanied by deforestation, ecosystem degradation, land grabs and the extensive use of harmful chemicals (Costantino Citation2016; Elgert Citation2016; Goldfarb and Zoomers Citation2013; Leguizamón Citation2016). Santiago del Estero forms part of the Gran Chaco region, one of the most active deforestation frontiers in the world (Leguizamón Citation2016, 687). Illegal deforestation is not uncommon, partly because the provincial forest management agency has limited capacity to prevent it (Interview government official, 2016).

Santiago del Estero is the province in Argentina with the greatest number of violent conflicts over land, and the insecure land tenure situation has been an issue for decades (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013). The social movement, Movimiento Campesino de Santiago del Estero (Peasant movement of Santiago del Estero), has been at the forefront in addressing land tenure issues (Jara and Paz Citation2013). In recent times, these conflicts have intensified (Leguizamón Citation2014). There are confirmed incidences of the killing of peasants, violent confrontations with smallholders and other inappropriate actions by private security firms (Bidaseca et al. Citation2013; Jara and Paz Citation2013; Lapegna Citation2012; Leguizamón Citation2016).

8.2. Tree plantations in Corrientes

Corrientes has seen an increase in the area of land under tree plantations with 450,000 hectares of plantations in 2014 (Provincia de Corrientes Citation2014). The provincial government intends that the amount of land allocated to plantations will increase by around 53,000 hectares annually (Plan Estratégico Forestoindustrial Corrientes Citation2010). The government is very supportive of this expansion, not only setting a very ambitious target of 1 million hectares to be planted by 2025–about 12% of the total land area of Corrientes!–but also publicly flagging that up to 4 million hectares are potentially suitable for industrial tree plantations (Provincia de Corrientes Citation2014). Due to geographical features such as reliable rainfall, water availability, low elevation, climate and the fertility of the soil, Corrientes is promoted as one of the most suitable regions in the world for pine and eucalyptus plantations (Provincia de Corrientes Citation2014). Worldwide, tree plantations are associated with the high use of agrochemicals, ecological damage, excessive water use, land conflict, an increased risk of fire, loss of livelihoods and poor working conditions (Gerber, Veuthey, and Martínez-Alier Citation2009; Overbeek, Kröger, and Gerber Citation2012; Slutzky Citation2013).

More than other areas of Argentina, in the early 20th century, the rural areas of Corrientes exhibited a feudal-like class structure, with concentrated land ownership and a strong rural elite (Slutzky Citation2014). Cultural acceptance of this feudal structure partially explains why there have only been a few well-organised resistance initiatives (Slutzky Citation2014). Nevertheless, one of the most active NGOs in the Province is Guardianes del Iberá. This NGO highlights the concerns associated with land tenure that arise from agriculture and forestry by, for example, organising demonstrations in the capital city, Corrientes.

9. Environmental and social injustice from land grabbing: findings from the field

9.1. Pre-existing injustice

It was evident there was limited access to essential public services in the study areas, including a lack of access to electricity and limited access to (potable) water. While the lack of electricity can potentially be addressed by the installation of solar panels, other than buying bottled water there are few options available for the provision of safe drinking water. Because of the cost and inconvenience of bottled water, many poor people in Santiago del Estero consumed water from local wells, which is often not fit for human consumption because of naturally-occurring arsenic (see Bhattacharya et al. Citation2006). Another difficulty in remote areas is limited access to secondary education and the poor quality of education in general. School attendance is often low because of the distance to school, especially with the extreme weather conditions often experienced. Furthermore, children are often required to work in the fields. This results in high levels of functional illiteracy. The problem is compounded because these rural areas are not attractive to teachers and, thus, it is hard for rural schools to attract and retain quality staff. Because of the lack of capacity in the education system generally, and especially because of inadequate monitoring of schools and teaching staff, in some rural areas teachers frequently abscond. This lack of access to essential public services severely disadvantages rural people.

The poor quality of the rural roads, limited ownership of private vehicles, and the limited availability of public transport has restricted the ability of rural people to advance their claims. Another inequality was limited cell phone reception in remote areas. Rural people were vulnerable to climate change effects such as heat waves, drought, and excessive rainfall. The ability to obtain regular work was challenging. Where people did work, it was often temporary, seasonal, based on subcontracting arrangements, and frequently under poor working conditions. Many people in the study areas lived from subsistence farming activities together with the receipt of various forms of state benefits (welfare payments). There were many factors that restricted people in physically accessing the formal decision-making spheres. Even where they had access, the procedures were not always easy for rural people to follow. Overall, there was a strong historical marginalisation of rural people that comes from their geographical setting, as well as from the urban-rural bias that exists in all things. These characteristics of remote areas in Argentina are consistent with remote communities in most places in the world.

9.2. Injustice brought about by land grabbing

The increasing interest in land brings insecurity for local people, as they face the possibility of being displaced and dispossessed, expelled from their homes, and severed from their livelihoods. An important land issue in Argentina is the large extent of informal occupancy. Companies buying land tend not to be aware that formal land title does not necessarily imply vacant possession, as expressed in the following quote from a government official:

Selling and buying land is a business … you do not even have to visit the land to buy it, you can buy it based on photos or satellite images … Basically, land sales are based on presumptions. When the buyer actually arrives at the site, it may be full of people. This is where conflict arises. People who buy a formal title have the economic ability to buy [the land] and to hire a surveyor, engineer, and a lawyer, and can gain permission from the forest management agency to start clearing [the land]. Rural people, however, live in the middle of nowhere, they raise goats, work as woodcutters, or they go to other provinces to seek an income … they do not have the financial means to hire a lawyer [to defend their rights]. It has always been difficult for them to have access to justice. There is an economic obstacle to being able to reach it. These people are living ‘the quiet life’. Gaining land title is not high on their agenda. It only becomes part of their agenda when conflict has started. This complicates this issue.

There is limited knowledge by rural communities about their land rights. This issue is being tackled by some NGOs. However, because of their limited financial means, and because formalisation of land title is not seen as an immediate issue, most rural people do not take action to formalise their land occupancy. In the words of one interviewee: we have possession rights, but to gain formal titles we need money for the [GPS] measurements, the surveyor and a lawyer. But money is what we have least … I know that one day we will have a problem with the land [access rights] [but for now we have other things to worry about] (Interview smallholder, 2016).

One complexity in the process of formalising land use is the disorganised state of the land registry office. It is often the case that rural communities live on land belonging to a formal title holder who is not easily identifiable. This is problematic in their attempts to implement the Ley Veinteañal procedure, which requires the identification and active involvement of the formal land holder. Another complexity is that rural people have to deal with an institutional setting that strongly favours large-scale land use and actively discourages or suppresses the Ley Veinteañal procedure. Even if people achieve this, women are usually left disadvantaged, as titling is predominantly done in the name of men, creating problems in cases of land sale or divorce (Interview land registry, 2015).

The demand for land and the high returns that are now possible result in people engaging in various forms of malpractice, including falsifying papers and bribing officials (Jara and Paz Citation2013). Moreover, staff from the land registry office, real estate agencies and middle-men can be involved in illicit or dubious actions that facilitate land sales. One of our interviewees (Interview real estate agency, 2015) mentioned that laws were not being respected when it comes to the area of land foreigners can own. It was stated in another interview (Interview government official, 2016) that there were cases where land was bought illegally or by intimidating the informal settlers.

Land grabbing for tree plantations brings about many other issues. For example, in Corrientes, some specific issues include diminished work opportunities, reduced water availability, increased risk of fire, and poor labour conditions. One smallholder vegetable producer articulated many of the impacts the tree plantations were having on her and her community.

We cannot compete [with the companies in buying land]. They offer a lot … and it is very tempting [for the villagers to sell out] … The company might leave the house intact but will grow plantations right up to the house. I don’t like that they are taking the land. … Close to my house, there is a plantation of 150 hectares … before it was a beautiful field. You have no idea how beautiful it was! … Now, some of the lagoons have dried out [because of the plantations] … There are not so many work opportunities in the region anymore. People are leaving because of that … It only takes 2 people to manage 1,000 hectares of plantation. Here on my 15 hectares, I provide work for 10 people … [With the plantations] there are no more possibilities to expand my farm or to use other plots of land to let the soil rest and recover [fallow]. … Another issue is water availability. We need to construct [new and deeper] wells to be able to irrigate, we need equipment for this but this is expensive … for the big producers these costs are okay, but for smallholders, it is a lot of money … Maybe in a few years, the situation will change [and more work will come]. But I am afraid of the sawmills, because many people are injured or die working there.

Another issue brought by land grabbing is that when strangers come, people’s feelings of trust and safety change. During fieldwork, several families reported that they experienced conflict with the new land owners. These conflicts included cases of animals being killed when they wandered into the new owner’s paddocks.

Yet another issue was increased exposure to agrochemicals arising from changed land use. People were not sufficiently aware of the risks associated with agrochemical use, and they engaged in behaviours that increased their exposure. For example, farm workers did not always follow the mixing instructions, did not always wear protective clothing, and did not properly dispose of the chemical containers. Communities were exposed by spray drift and by being sprayed-over, as well as by residues getting into their drinking water. Given the long-term harmful effects of the chemicals, the spraying of agrochemicals can be seen as both instant and slow violence.

Although there are label procedures (as stated by the chemical manufacturer), as well as Argentinian regulations (usually varying by province), typically including withholding periods and application distances from houses and watercourses, they are not observed or policed. One interviewee, a medical doctor and health advocate for rural people, told us that rural schools were routinely being sprayed by crop-dusters. He indicated that children were especially susceptible to the negative health impacts from agrochemicals.

Slow violence is experienced insidiously by local people in a number of ways, including diminished access to water, increased pollution, climate change and diminished livelihood options. These collectively and progressively result in a declining situation in which living conditions and general wellbeing deteriorate to such an extent as to be almost unliveable. Thus, poverty creates the conditions for acquiescence to land grabbing. In this context, poverty is a form of slow violence in itself, and it constrains and compounds the violence of land grabbing and displacement.

10. Strategies and socially transformative actions used by rural communities to cope with land grabbing

Here, we distil the main strategies local people use to cope with and adapt to land grabbing. We have developed this list partly from our field observations and partly from other experiences reported in the literature, notably Goldfarb and van der Haar (Citation2016), Habra and Franzzini (Citation2016), and Jara, Gil Villanueva, and Moyano (Citation2016). Reflecting on this material and our observations, we were able to identify five main strategies that communities can use to cope with land grabbing, which we describe below.

The first (and arguably the strongest) is legal action and other proactive steps local people can take to formally defend and maintain access to land under threat. Specifically, they can initiate Ley Veinteañal procedures to gain formal land title. They can also advocate for greater respect for informal land use (both on government as well as on private land) and for easier access to, and operation of, the Ley Veinteañal procedure. To draw attention to these issues, they can initiate a wide variety of protest actions.

The second strategy is proactive organisation to improve the livelihood strategies and wellbeing of the rural community, and to engage in various forms of capacity building to improve the background conditions of the community so that they are better able to fight for their rights and to gain land title. A further dimension of this strategy is to enhance the capacities of people, and their ability to claim formal title. This includes collecting proof, such as school enrolment data, to establish the period of time spent in the locality, the marking of important locations such as graves or ritual structures, and mapping and fencing to demarcate land claims. NGOs or government organisations can conduct workshops with local communities to increase their awareness of their rights, and how to act in ways that enhance their ability to claim their rights.

The third strategy is for local communities to negotiate with the historic formal title holder or intending buyer for the community to secure formal title over a small parcel of land in exchange for agreement that the community will not pursue any claim over the larger piece of land – in other words, to do a deal with the land owner. We observed this strategy being implemented during our fieldwork. A process of negotiation was started between a community (assisted by a government agency and a local NGO) and a local businessman. This local businessman inherited formal land title of over 3,600 hectares, on which a local community had lived for generations. Although this man’s family did not actively use the land, when he inherited it, he developed a plan to establish a major ranching operation and initially wanted to expel the community. The community was eventually able to negotiate with him to gain formal land title to 1,400 hectares, with him paying all legal costs and costs incurred by the community. He settled on owning 2,200 hectares. By doing a deal, the community guaranteed their future, even though they had to make a sacrifice.

The fourth strategy is to sell out (accept a payment) and vacate the land. This is sometimes done under duress, or because of a perception that there is likely to be no better option. One of our interviewees mentioned that, in her community, out of necessity due to rising costs at the time, many people had already sold out. Selling out is potentially a risky strategy because it is unlikely that the payment received will be sufficient for people to re-establish themselves elsewhere. In their new environments, they are likely to face higher cost structures, and not have the subsistence living opportunities they previously had. Unless the compensation payments are truly fair, rural people should not be advised to accept such arrangements.

The fifth strategy is one of accommodation, basically, to adapt their lives and adjust to the changes brought about by land grabbing. In this strategy, people do experience many negative impacts, but generally consider that they have no alternative or no opportunity to overtly resist. Unfortunately, it is perhaps the default outcome from land grabbing. Arguably, it is the worst outcome for local people. Livelihood adaptation and accommodation was clearly reflected in comments made to us by one smallholder impacted by agricultural expansion. Because of diminished land access, there was not enough feed for her animals, and consequently she struggled to keep her herd of goats properly fed, with about half of them dying from malnutrition. In desperation, together with the local farmers’ association, she initiated the establishment of a small-scale animal feed manufacturing facility that could produce sufficient product to feed all the livestock in the entire community. Although a cultural and production shift from open grazing to trough feeding, whether this was ultimately a good outcome or not will depend on the economics of the feed, which at the time of our research were unclear.

An important enabling mechanism for communities to initiate socially transformative action is to connect with other people, communities, the church, NGOs and other institutions. It was observed that, where local people were connected with people in capital cities, the options, likelihood and effectiveness of their efforts improved considerably. However, even though there were various assistance programmes available, funded and/or run by various NGOs or public sector agencies, these programmes were often inadequate and did not sufficiently address the needs of rural communities. One issue was that most agencies and NGOs were only able to act in response to an issue and after conflict has started, with prevention of land conflict not their priority. Given the inadequate nature of their assistance, the inevitable outcome was that the interests of the rural communities were not protected and rural people were being rendered landless.

The various strategies described above all have limitations. Primarily, negotiations always take place in an unequal power arena. Furthermore, the state actively facilitates land grabbing as a development strategy and does not adequately protect its people. Where people are able to stay in their houses and retain some access to land, it is seldom of the same area or quality, thus they are made worse off. Even where they gain formal title, there are further complications, for example, land taxes and other charges need to be paid. The changes in land-use practices alter the way people interact, which frequently leads to a loss of social cohesion, and can exacerbate pre-existing tensions in the community.

11. Conclusion

Land grabbing and land-use change are serious threats to the effective functioning and wellbeing of local communities. The operationalisation of land grabbing, injustice and slow violence is co-produced by the state, particularly with its endorsement of land grabbing as a development strategy. Our paper has shown that, as a result of the expansion of land grabbing, vulnerable people in rural areas in Argentina face disproportionate environmental injustice and experience various forms of violence. Inequitable distribution, restricted opportunities for participation, lack of procedural justice and lack of respect and recognition of difference are key issues in the land grabbing discourse. Local inequalities and specificities influence the differential distribution of benefits and harms, with some local people benefitting and others not. Thus, land grabbing actively creates social exclusion.

Pre-existing injustices exacerbate the impacts of land grabbing. The difficulties and injustices people face include the lack of basic needs, especially food, water, income, mobility, work, education, healthcare and adequate housing. Locational specificities influence the opportunities to protest against environmental injustice. This can lead to some people having to become accepting of environmental and social injustice. The opportunity to perform socially transformative action depends on many things, such as the political setting, remoteness, available resources, access to information and external contacts (Coenen and Halfacre Citation2003; Lapegna Citation2016). Some people affected by land grabbing can still take strong action to defend their interests, while others feel that they have little choice but to acquiesce.

We consider that land grabbing is a form of slow violence because it leads to a vast range of negative social impacts that are largely ignored or denied by most stakeholders, including the impacted people themselves. In general, there is a lack of consideration for the health and wellbeing of the environment and rural communities, as well as of the different meanings attached to nature by the different stakeholders. Slow violence is frequently not addressed by rural communities, partly because of its insidious nature, but also because of the difficulties they face and because the changes invoked are often invisible, sometimes irreversible, as well as because of the perception that nothing can be done. However, we argue that local communities should not be considered as being powerless, rather that the power they inherently have cannot be sufficiently activated because of various local specificities. Depending on how opportunities play out in the future, local people may change their perceptions of their options and strategies, and the likely effectiveness of these strategies will also change.

Social and environmental justice movements assist in the fight for justice and inclusion. A more just and sustainable society will occur only through the efforts of the people who stand up for the environment and a fairer society (Kaika Citation2017; Martínez-Alier Citation2012). There are many aspects that need to be addressed in order to facilitate and support these people. In particular, they need financial resources and agency to be heard and to promulgate their claims. Another important ingredient in a fairer society is greater recognition of the informal use of land by local communities. This recognition would help local people strengthen their place in society by improving their livelihoods and by assisting individuals to reach their full potential as human beings (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010). Investing in essential public services and basic needs such as water, housing, education, roads, healthcare, reasonable work and working conditions would improve social equality. Moreover, investing in essential public services would enable improved political engagement in land-related issues by a wider range of people (Jara, Gil Villanueva, and Moyano Citation2016). Socially transformative action has the potential to redress environmental injustice and to address some of the malpractices brought about by land grabbing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Philippe Hanna and Julia Gabella for their help and insightful comments on a previous version of this paper and Annelies Verstraelen and Anton van Rompaey for providing the map. Moreover, we would like to thank the people in Argentina who contributed to this research by sharing their experiences, knowledge and time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agyeman, J., D. Schlosberg, L. Craven, and C. Matthews. 2016. “Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41 (1): 321–340. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090052.

- Altieri, M. A., and V. M. Toledo. 2011. “The Agroecological Revolution in Latin America: Rescuing Nature, Ensuring Food Sovereignty and Empowering Peasants.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (3): 587–612. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.582947.

- Baker, S., and A. Mehmood. 2015. “Social Innovation and the Governance of Sustainable Places.” Local Environment 20 (3): 321–334. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.842964.

- Banerjee, A. 2015. “Neoliberalism and Its Contradictions for Rural Development: Some Insights from India.” Development and Change 46 (4): 1010–1022. doi:10.1111/dech.12173.

- Bhattacharya, P., M. Claesson, J. Bundschuh, O. Sracek, J. Fagerberg, G. Jacks, R. A. Martin, A. R. Storniolo, and J. M. Thir. 2006. “Distribution and Mobility of Arsenic in the Rio Dulce Alluvial Aquifers in Santiago Del Estero Province, Argentina.” Science of the Total Environment 358 (1–3): 97–120. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.04.048.

- Bidaseca, K., A. Gigena, F. Gómez, A. M. Weinstock, E. Oyharzábal, and D. Otal. 2013. Relevamiento y Sistematización de Problemas de Tierras de Los Agricultores Familiares en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de la Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca de la Nación.

- Boletta, P. E., A. C. Ravelo, A. M. Planchuelo, and M. Grilli. 2006. “Assessing Deforestation in the Argentine Chaco.” Forest Ecology and Management 228 (1–3): 108–114. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.02.045.

- Borras, S. M., C. Kay, S. Gomez, and J. Wilkinson. 2012. “Land Grabbing and Global Capitalist Accumulation: Key Features in Latin America.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 33 (4): 402–416. doi:10.1080/02255189.2012.745394.

- Brent, Z. W. 2015. “Territorial Restructuring and Resistance in Argentina.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (3–4): 671–694. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1013100.

- Bullard, R. 1996. “Environmental Justice: It’s More than Waste Facility Siting.” Social Science Quarterly 77 (3): 493–499.

- Busscher, N., C. Parra, and F. Vanclay. 2018. “Land Grabbing within a Protected Area: The Experience of Local Communities with Conservation and Forestry Activities in Los Esteros Del Iberá, Argentina.” Land Use Policy 78: 572–582. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.07.024.

- Carruthers, D. V. 2008. Popular Environmentalism and Social Justice in Latin America. In Environmental Justice in Latin America. Problems, Promise, and Practice, edited by D. V. Carruthers, 1–22. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cernea, M. 1997. “The Risks and Reconstruction Model for Resettling Displaced Populations.” World Development 25 (10): 1569–1587. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5.

- Coenen, F. H. J. M., and A. C. Halfacre. 2003. “Local Autonomy and Environmental Justice: Implementing Distributional Equity across National Scales.” In Achieving Sustainable Development: The Challenges of Governance across Social Scales, edited by H. Th. A. Bressers, and W. A. Rosenbaum, 185–210. Westport: Praeger.

- Cook, I. R., and E. Swyngedouw. 2012. “Cities, Social Cohesion and the Environment: Towards a Future Research Agenda.” Urban Studies 49 (9): 1959–1978. doi:10.1177/0042098012444887.

- Cooke, B., and Kothari, U., eds. 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

- Costantino, A. 2016. “El Capital Extranjero y el Acaparamiento de Tierras: conflictos Sociales y Acumulación Por Desposesión en Argentina.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 55: 137–149. doi:10.7440/res55.2016.09.

- Dare, M., J. Schirmer, and F. Vanclay. 2014. “Community Engagement and Social Licence to Operate.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32 (3): 188–197. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.927108.

- Desmarais, A. A. 2002. “Peasant Speak – the Vía Campesina: Consolidating an International Peasant and Farm Movement.” Journal of Peasant Studies 29 (2): 91–124. doi:10.1080/714003943.

- Elgert, L. 2016. “More Soy on Fewer Farms in Paraguay: Challenging Neoliberal Agriculture’s Claims to Sustainability.” Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (2): 537–561. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1076395.

- Escobar, A. 2000. “El lugar de la naturaleza y la naturaleza del lugar: Globalización o postdesarrollo?” In Colonialidad Del Saber: eurocentrismo y Ciencias Sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas, edited by E. Lander, 131–161. Buenos Aires: Ediciones CICCUS.

- Gallagher, D. R., and S. E. Jackson. 2008. “Promoting Community Involvement at Brownfields Sites in Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Neighbourhoods.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 51 (5): 615–630. doi:10.1080/09640560802210971.

- Galtung, J. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research 6 (3): 167–191. doi:10.1177/002234336900600301.

- Garcia-Lopez, G. A., and N. Arizpe. 2010. “Participatory Processes in the Soy Conflicts in Paraguay and Argentina.” Ecological Economics 70 (2): 196–206. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.013.

- Gerber, J. F., S. Veuthey, and J. Martínez-Alier. 2009. “Linking Political Ecology with Ecological Economics in Tree Plantations Conflicts in Cameroon and Ecuador.” Ecological Economics 68 (12): 2885–2889. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.06.029.

- Global Witness. 2016. On Dangerous Ground. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/dangerous-ground/

- Goldfarb, L., and A. Zoomers. 2013. “The Drivers Behind the Rapid Expansion of Genetically Modified Soya Production into the Chaco Region of Argentina.” In Biofuels: Economy, Environment and Sustainability, edited by Z. Fang, 73–95. Rijeka: InTech.

- Goldfarb, L., and G. van der Haar. 2016. “The Moving Frontiers of Genetically Modified Soy Production: Shifts in Land Control in the Argentinian Chaco.” Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (2): 562–582. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1041107.

- GRAIN. 2012. GRAIN Releases Data Set with Over 400 Global Land Grabs. Accessed February 1, 2019. https://www.grain.org/article/entries/4479-grain-releases-data-set-with-over-400-global-land-grabs.

- GRAIN. 2016. The Global Farmland Grab in 2016. How Big, How Bad? Accessed February 1, 2019. https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5492-the-global-farmland-grab-in-2016-how-big-how-bad.

- Grajales, A. 2011. “The Rifle and the Title: Paramilitary Violence, Land Grab and Land Control in Colombia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 771–791. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.607701.

- Gutiérrez, M. E., and V. G. Gonzalez. (eds). 2016. Desarrollo Rural, Política Pública y Agricultura Familiar: Reflexiones en Torno a Experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar en Santiago Del Estero. San Miguel de Tucumán: Magna Publicaciones.

- Habra, H. D., and del M. Franzzini. 2016. “Políticas Públicas Fiscales: La Reforma del Código Procesal Penal en Frías. Diferentes Estategias de Intervención en el Territorio.” In Desarrollo Rural, Política Pública y Agricultura Familiar. Reflexiones en Torno a Experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar en Santiago Del Estero, edited by M. E. Gutiérrez, and V. G. Gonzalez, 51–65. San Miguel de Tucumán: Magna Publicaciones.

- Hall, R., M. Edelman, S. M. Borras, Jr. I. Scoones, B. White, and W. Wolford. 2015. “Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (3–4): 467–488. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1036746.

- Hanna, P., and F. Vanclay. 2013. “Human Rights, Indigenous Peoples and the Concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 31 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1080/14615517.2013.780373.

- Hanna, P., J. Langdon, and F. Vanclay. 2016. “Indigenous Rights, Performativity and Protest.” Land Use Policy 50: 490–506. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.06.034.

- Hanna, P., F. Vanclay, E. J. Langdon, and J. Arts. 2014. “Improving the Effectiveness of Impact Assessment Pertaining to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Environmental Licensing Procedure.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 46: 58–67. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2014.01.005.

- Hanna, P., F. Vanclay, J. Langdon, and J. Arts. 2016a. “The Importance of Cultural Aspects in Impact Assessment and Project Development: Reflections from a Case Study of a Hydroelectric Dam in Brazil.” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 34 (4): 306–318. doi:10.1080/14615517.2016.1184501.

- Hanna, P., F. Vanclay, J. Langdon, and J. Arts. 2016b. “Conceptualizing Social Protest and the Significance of Protest Action to Large Projects.” Extractive Industries and Society 3 (1): 217–239. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2015.10.006.

- Ho, K. 2007. “Structural Violence as a Human Rights Violation.” Essex Human Rights Review 4 (2): 1–17.

- Imperiale, A. J., and F. Vanclay. 2016. “Experiencing Local Community Resilience in Action: Learning from Post-Disaster Communities.” Journal of Rural Studies 47: 204–219. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.08.002.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. 2016. Accessed February 1 2019. http://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/opex_09_16.pdf.

- Jara, C., and R. Paz. 2013. “Ordenar el Territorio Para Detener el Acaparamiento Mundial de Tierras: La Conflictividad de la Estructura Agraria de Santiago Del Estero y el Papel Del Estado.” Proyección 15: 171–195.

- Jara, C., L. Gil Villanueva, and L. Moyano. 2016. “Resistiendo en la frontera. La Agricultura Familiar y las luchas territoriales en el Salado Norte (Santiago del Estero) en el período 1999-2014.” In Desarrollo Rural, Política Pública y Agricultura Familiar: Reflexiones en Torno a Experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar en Santiago Del Estero, edited by M. E. Gutiérrez, and V. G. Gonzalez, 33–49. San Miguel de Tucumán: Magna Publicaciones.

- Jijelava, D., and F. Vanclay. 2017. “Legitimacy, Credibility and Trust as the Key Components of a Social Licence to Operate: An Analysis of BP’s Projects in Georgia.” Journal of Cleaner Production 140: 1077–1086. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.070.

- Kaika, M. 2017. ‘Don’t Call Me Resilient Again!’ the New Urban Agenda as Immunology… or What Happens When Communities Refuse to Be Vaccinated with ‘Smart Cities’ and Indicators.” Environment and Urbanization 29 (1): 89–102. doi:10.1177/0956247816684763.

- Kollmuss, A., and J. Agyeman. 2002. “Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior?” Environmental Education Research 8 (3): 239–260.

- Lakes, T., M. Brückner, and A. Krämer. 2014. “Development of an Environmental Justice Index to Determine Socio-Economic Disparities of Noise Pollution and Green Space in Residential Areas in Berlin.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57 (4): 538–556. doi:10.1080/09640568.2012.755461.

- Lapegna, P. 2012. “Notes from the Field. The Expansion of Transgenic Soybeans and the Killing of Indigenous Peasants in Argentina.” Societies Without Borders 8 (2): 291–308.

- Lapegna, P. 2016. “Genetically Modified Soybeans, Agrochemical Exposure, and Everyday Forms of Peasant Collaboration in Argentina.” Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (2): 517–536. doi:10.1080/03066150.2015.1041519.

- Laurian, L., and R. Funderburg. 2014. “Environmental Justice in France? a Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Incinerator Location.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57 (3): 424–446. doi:10.1080/09640568.2012.749395.

- Leguizamón, A. 2014. “Modifying Argentina: GM Soy and Socio-Environmental Change.” Geoforum 53: 149–160. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.001.

- Leguizamón, A. 2016. “Environmental Injustice in Argentina: Struggles Against Genetically Modified Soy.” Journal of Agrarian Change 16 (4): 684–692. doi:10.1111/joac.12163.

- Malhi, Y., J. T. Roberts, R. A. Betts, T. J. Killeen, W. Li, and C. A. Nobre. 2008. “Climate Change, Deforestation, and the Fate of the Amazon.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 319 (5860): 169–172. doi:10.1126/science.1146961.

- Martínez-Alier, J. 2012. “Environmental Justice and Economic Degrowth: An Alliance Between Two Movements.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 23 (1): 57–73.

- Matulis, B. S. 2014. “The Economic Valuation of Nature: A Question of Justice?” Ecological Economics 104: 155–157. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.010.

- McSweeney, K., D. J. Wrathall, E. Nielsen, and Z. Pearson. 2018. “Grounding Traffic: The Cocaine Commodity Chain and Land Grabbing in Eastern Honduras.” Geoforum 95: 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.07.008.

- Mehmood, A., and C. Parra. 2013. “Social Innovation in an Unsustainable World.” In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research, edited by F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, A. Hamdouch, 53–66. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. 2010. Plan Estratégico Agroalimentario y Agroindustrial Participativo y Federal 2010-2020. Accessed February 1, 2019. http://inta.gob.ar/sites/default/files/inta_000001-libro_pea_argentina_lider_agroalimentario.pdf.

- Ministry of Agroindustry. 2017. Datos Abiertos Agroindustria. Accessed February 1, 2019. https://datos.magyp.gob.ar/reportes.php?reporte=Estimaciones.

- Murmis, M., and M. R. Murmis. 2012. “Land Concentration and Foreign Land Ownership in Argentina in the Context of Global Land Grabbing.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 33 (4): 490–508. doi:10.1080/02255189.2012.745395.

- Narain, V. 2014. “Whose Land? Whose Water? Water Rights, Equity and Justice in a Peri-Urban Context.” Local Environment 19 (9): 974–989. doi:10.1080/13549839.2014.907248.

- Neiff, J. J. 2004. El Iberá En Peligro?. Buenos Aires: Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina.

- Nixon, R. 2011. Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M., and A. Sen, (eds). 1993. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.