Abstract

Direct potable reuse (DPR) can improve reliability of water supplies by generating drinking water from wastewater, but communities have consistently opposed DPR more than other forms of reuse. Using interview data regarding DPR projects in five inland communities, this study fills gaps in the literature with an analysis of factors influencing acceptance of DPR. While scholars have recommended public processes used to implement non-potable and indirect potable reuse projects, there is little-to-no documentation about whether and how they have been used to implement DPR projects. Further, previous research has focused on large coastal cities. Counter to previous recommendations, we found minimal public deliberation of reuse options and public education/outreach occurring post-project conception. Findings suggest that direct experience with water scarcity, community smallness, and governance strongly influence DPR acceptance. With few DPR facilities worldwide, this new knowledge is useful to water planners who are interested in the feasibility of DPR in inland areas.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and knowledge gaps

By 2025, the United States (US) Department of Interior predicts “hot spots” of conflict over water in the American Southwest (United States Department of Interior Citation2005; see ), where water scarcity is projected to remain dire and climate change is expected to further reduce supplies (Gutzler Citation2012). Communities in these hot spots must choose from among their available options to create sustainable water supplies, and unexploited water sources of adequate quality must be proactively identified before shortfall leads to crisis.

Figure 1. Hot spots for potential water conflict by 2025 (US Department of Interior Citation2005). Used with permission of the US Department of Interior.

Planned potable water reuse holds promise for improving the sustainability and reliability of potable water supplies by generating drinking water from wastewater. Potable water reuse is classified as either direct or indirect. In direct potable reuse (DPR), wastewater is highly treated, either in separate wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) and drinking water treatment plant (WTP) systems, or in a single advanced treatment system. Then the purified water is typically combined with native or imported waters and treated at the WTP before entering the distribution system, where it becomes available for all uses. (It is also possible to inject the purified water directly into the distribution system following purification, though this approach has not yet been taken in the US.) Indirect potable reuse (IPR) is the same as DPR, except that the purified water is directed to an environmental buffer (e.g., a reservoir or aquifer) before eventual withdrawal and treatment at the WTP (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011). Numerous communities around the world have implemented IPR over the past several decades, but DPR is far less common, with one installation in Windhoek, Namibia and a few in South Africa and Texas in the US (Scruggs and Thomson Citation2017; USEPA Citation2017). While DPR is relatively new to the US, the Namibian facility has been operating since 1968, in various configurations, with no significant adverse health effects reported (Crook Citation2010; van Rensburg Citation2016).

Despite research demonstrating that IPR and DPR can be safe (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011), one of the most significant issues surrounding implementation is public opposition. Because the public has rejected many reuse projects, there is a substantial body of work on public perceptions of, and attitudes towards, water reuse, along with recommendations for effective public education and outreach related to water reuse projects. However, most of this work is based on experiences with non-potable reuse or IPR in coastal US cities and Australia. Importantly, many candidate communities for potable reuse in the US are inland (see ), where IPR may not be an option due to lack of a suitable environmental buffer (Scruggs and Thomson Citation2017).

Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow (Citation2003) summarized research from 1972 through 2002 demonstrating that the public has more consistently opposed using reuse water for drinking than for any other potential use. In 2004, Bridgeman went so far as to conclude that “the public is perhaps not yet ready to accept potable water reuse on a large scale, whilst other options still exist, regardless of the feasibility of those alternatives” (154). While there are now numerous IPR plants operating in the US, researchers have recently reported that the public is less accepting of DPR than IPR (e.g., Tennyson, Millan, and Metz Citation2015; Ormerod and Scott Citation2013). Importantly, it has not yet been demonstrated whether the same public education, outreach, and engagement recommendations for IPR projects also apply to DPR projects, or if other strategies are needed to help the public make informed decisions about water supply options.

To date, the few DPR projects that have been planned or implemented in the US are in the inland Southwest. It is reasonable to expect that public acceptance of DPR would be based in part on contextual issues, such as water scarcity and perceived availability of additional water supply options. However, there is little documentation of the contextual issues or public processes used in the few DPR projects that have been introduced to US communities to help water managers understand how to approach DPR projects while effectively communicating about public health, safety, and other matters. Is there anything new we can learn – specific to the introduction of DPR projects – by studying these few cases in the US? Does the fact that there are so few DPR projects in the US (and in the world) suggest that there may be a different approach needed in comparison to the IPR and non-potable reuse projects previously described in the literature? At the time of this research project, in the few cases known to the authors where potential DPR projects were introduced to communities, the projects were all accepted by the public.

1.2. Study objectives

Using existing literature on the characteristics and outcomes of strategies used to introduce potable water reuse to the public, plus new data on DPR project introduction in five communities in the inland southwestern US, this study aims to fill gaps in the literature with an analysis of factors influencing public acceptance of DPR. While scholars have previously discussed recommendations and outcomes related to approaches for introducing reuse projects (mostly non-potable or IPR) to the public, there is little-to-no documentation about how these strategies have been used – or whether they were successful – in attempting to implement actual DPR projects. Further, most of this previous research was conducted in large coastal US cities or Australia. With very few DPR facilities in operation in the US, this new knowledge will be useful to water planners, city officials, and policy actors in inland areas who are interested in the feasibility of DPR for their communities.

2. Review of literature related to public acceptance of potable water reuse

2.1. Public attitudes toward potable water reuse

According to Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow (Citation2003, 3), the first potable reuse projects, such as those in Windhoek, Namibia, Water Factory 21 in California, and the Upper Occoquan Sewerage Authority in Northern Virginia, were introduced at a time when public involvement in decision making was not the norm: “the public trusted the experts or governments to make the right decision and they therefore did not usually participate in or challenge project decisions”. However, more recent potable reuse projects have been tabled or cancelled because of public opposition (Tennyson, Millan, and Metz Citation2015). Today, public acceptance is crucial to the success of any water reuse project and it is influenced by many factors, such as the perceived value of water, the history of the water to be reused, trust in the entities promoting the reuse project, trust in the technologies used to purify the reuse water, education on fundamental water concepts, as well as those that apply more specifically to water reuse, the timing of the proposed reuse project with local circumstances (e.g., drought), inclusion of water quality monitoring in the reuse scheme, attitudes toward the environment, and the cost of the reuse water or water reuse project (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003; Bridgeman Citation2004; Ormerod and Scott Citation2013).

Studies in Queensland, Australia, showed that using a “Decide, Inform, Defend” approach to introduce potable reuse projects led to public skepticism and opposition. On the other hand, holding community consultations in the form of “information days” led attendees to accept a wider variety of water management options compared to those who did not attend; in fact, for the majority of those attending the information days, DPR was the top choice among water management options, although it was not selected for implementation by decision makers (Simpson Citation1999, 61-62). In other communities nearby, residents found potable reuse to be an option worthy of further consideration following intensive focus group activities and a survey. This prompted Australian organizations to develop a Water Education Program (Simpson Citation1999), as discussed later. In the US, focus group research in California demonstrated that most participants were supportive of non-potable reuse and comfortable with IPR. While most were initially uncomfortable with DPR, they became somewhat more comfortable after exposure to detailed messaging: information about the treatment process, the effluent water quality, and monitoring systems proved to increase acceptance of potable reuse among focus group participants. Telephone surveys conducted as part of the same research also showed that people had higher levels of comfort with IPR than DPR because of the natural processes included in IPR (Tennyson, Millan, and Metz Citation2015).

Water planners cannot solely rely on drought or water shortages as a strategy to gain public acceptance of potable reuse (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003; Tennyson, Millan, and Metz Citation2015). However, when residents are aware of such issues, and options are effectively communicated, they may consider potable reuse as an option if it is shown to be safe for health and the environment (Simpson Citation1999).

Despite well-planned and -executed public communication, education, and outreach efforts, there will still be some members of the public who will not accept water reuse. It is important to note that such attitudes may not be rooted in a mistrust of the science or technologies being proposed, but rather in the policymakers or entities promoting or overseeing the water reuse project (Bridgeman Citation2004; Simpson Citation1999). In other cases, refusal to accept reuse may be based on concerns that the advanced purification technologies are too expensive, possibly leading to higher water bills (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003). Planners must thoroughly understand these attitudes to adequately address them. A societal legitimacy framework, which provides insights into dimensions of legitimacy and strategies for legitimization of potable water reuse, has been proposed as another way to understand why potable reuse projects are accepted or rejected by communities (Harris-Lovett et al. Citation2015).

2.2. Public trust related to potable reuse

Public trust in the individuals or entities promoting a reuse project is of critical importance to public perceptions of potable water reuse (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991; Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003), and building and maintaining public trust is a long-term commitment (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991). Bottom-up or collaborative processes can build public confidence and trust in controversial water reuse projects (Hartley Citation2006). Hartley (Citation2006, 125) specified a framework for “public outreach, education, participation, and planning” to gain public support for water reuse projects. Experiences documented in the literature reinforce the validity of this framework, both in creating “community-based, consensus-driven solution[s]” (Ingram et al. Citation2006, 179) and in failure to gain public trust (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010).

Additional studies have emphasized how issues related to trust can contribute to the success of water reuse projects, for example through timely communication with stakeholders, transparency in the decision-making process (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010), and a pre-existing trust in those selected to introduce a water reuse project (Ormerod and Scott Citation2013). The messenger of reliable information about water reuse is important: people tend to trust regulators (such as the EPA) and the medical community, but have less trust in others such as politicians and developers (MacPherson and Snyder Citation2013; Ormerod and Scott Citation2013). It is also essential that community members believe they are being adequately informed about the safety of the reused water and potential health risks to establish a strong relationship between trust and acceptance (Ross, Fielding, and Louis Citation2014). In addition, Bridgeman (Citation2004) found that the public is “more receptive to a presentation from an authority figure representing the promoter (i.e., the city) rather than a slick, sanitized presentation from a professional public-relations consultant” (153). Harris-Lovett et al. (Citation2015) reinforced this idea, reporting that when a utility’s management staff personally engages in public outreach campaigns, it helps to build the legitimacy of a potable reuse project. In summary, public trust is one of the most important factors to the success of a water reuse project (Khan Citation2013).

2.3. Recommendations for project introduction and public communication, education, and outreach on potable reuse

Public involvement in decision making on water reuse is critical because community members are directly affected (USEPA Citation2017). Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow (Citation2003) reinforced that “Decide Inform Defend” reuse project introduction approaches are ineffective and that conducting public education and outreach after a project’s conception is inadequate. Specifically, the authors state, “The new strategy proposed for implementing water reuse projects is to involve the community prior to the conception of any reuse projects”, which is “now recognized as the most essential component for obtaining long-term public support” (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003, 29).

Several researchers have found that public outreach and education can have a positive effect on public acceptance of water reuse (Hartley Citation2006; Lohman Citation1987; Nellor and Millan Citation2010), although the program details and community context are likely of critical importance to success (Ching Citation2010). Wegner-Gwidt (Citation1991) describes pro-active communication programs designed to help the public to make informed decisions about water reuse in general. Such programs include community relations, educational, and media relations components. The author states that a “successful project” requires dealing with “perceptions and expectations of people, community and special interest groups, government and the media.” Further, with a properly designed “planned communication program…if the public can understand what you understand they will probably agree with what you are doing” (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991, 314). Bridgeman (Citation2004) agreed that public outreach programs must be proactive and that they are essential to the success of any reuse project, but also added that the character and extent of outreach programs should be project specific. For example, his research demonstrated that planners could adopt less intensive outreach tactics in a community with an established reuse project or one involving non-potable reuse as compared to a project proposing potable reuse. Tennyson, Millan, and Metz (Citation2015, 61) developed “coordinated, consistent, and transparent communication plans” that can be employed at both the state and local community levels, although they also stress the importance of tailoring the plans to the needs and characteristics of the states or communities applying them.

Wegner-Gwidt (Citation1991) emphasized that water reuse projects are only successful when citizens are genuinely included in the decision-making process. First steps include understanding public opinion of the water utility or other organization(s) promoting the reuse project, and then gaining support of “opinion leaders, media contacts, and third-party experts” who can help with information dissemination (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991, 314). Bridgeman (Citation2004) found that early public outreach helped to build trust in the community and aided in disseminating project information prior to messaging from potential opposition. According to Wegner-Gwidt (Citation1991), dissemination should start at the highest levels in the community and move outward to groups such as service clubs. By approaching key stakeholders first, they can be called upon later to provide valuable endorsements of water reuse (Bridgeman Citation2004). Forming a Citizens Advisory Committee for the project is beneficial, perhaps most importantly because the committee will provide critical project input and demonstrate that public input is being used to help formulate the project (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991).

Wegner-Gwidt (Citation1991) recommended that the water utility train teachers, participate in public educational events, and develop ongoing programs in schools, which will serve to educate students and their families and develop a citizenry that is both knowledgeable about water and capable of making thoughtful and informed decisions. For educating the general public, small group meetings, workshops, open houses, and tours are more effective than mass communications through large community Q&A sessions. Community education on water ideally starts with the water cycle and covers other basic facts and concepts before tackling water reuse – and in educating about water reuse, the focus should be on promoting the benefits rather than attempting to defend against all possible criticisms (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991; Bridgeman Citation2004). The Water Education Program in Australia aims to educate residents about the water cycle, wastewater, and the technologies and monitoring that can be used to reliably make water reusable, with the goal of providing “people with knowledge and understanding so that they have an informed opinion” (Simpson Citation1999, 63). Carefully-planned and comprehensive water education programs require an early recognition of the need for water reuse. Unfortunately, recognition of the need for water reuse is sometimes only realized at a point when immediate action is needed, leaving inadequate time to establish large and comprehensive education and outreach programs (Bridgeman Citation2004).

Stenekes et al. (Citation2006) took issue with Wegner-Gwidt’s (Citation1991) suggestion that “…if the public can understand what you understand they will probably agree with what you are doing,” and argued that lack of public acceptance of potable reuse has been too often explained as the public’s lack of understanding about the health risks and treatment technologies associated with reuse. Consequently, this common explanation has led to the assumption that acceptance of reuse can be gained simply through better public education about risk and technology demonstrations. In fact, the authors’ research showed that “values rather than facts tended to underpin participant risk frames” (121). The authors emphasized that while enhancing public knowledge and understanding is important, so are “contextual circumstances and fundamentally divergent problem frames among stakeholders”, and that “a two-way dialogue about deeply held values early in planning processes” is of critical importance (Stenekes et al. Citation2006, 120). In short, insufficient public dialogue and input into potential reuse projects may be the reason for their failure, rather than a simple lack of education and information.

The media is another important influence on how people think about water reuse, and the social constructivist theory posits that the media itself constructs norms. In other words, “media has the power to create knowledge and shape social norms for water reuse” (Ching Citation2010, 113), and agenda setting by the news media instructs the public what to think about (Wolfe, Jones, and Baumgartner Citation2013). Likewise, the agenda-setting hypothesis states that the extent of media attention given to particular issues determines the degree of public concern for those issues (Behr and Iyengar Citation1985; Saroka Citation2002). Journalistic norms may also drive reporting of extreme stories (Boykoff and Boykoff Citation2007), and the “toilet to tap” framing creates the basis for a more extreme story than does one related to advanced technology used to purify water for drinking. Therefore, researchers have emphasized that it is important for proponents of water reuse projects to establish a good relationship with the media prior to initiating public involvement and education programs (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991). This might mean seeking out reporters who cover issues such as water reuse, pitching stories with public interest potential, and educating the reporter about the material involved. In addition to shifting social norms about the acceptability of water reuse (Ching, Citation2010), a well-educated media can help to educate the population about water reuse and raise awareness about proposed projects and the organizations supporting them. Social media can be another way for utilities to connect directly with stakeholders about water reuse. However, this form of communication is only effective if the utility commits to using social media throughout the lifetime of the project and dedicates the resources necessary to maintain its social media presence (USEPA Citation2017).

2.4. Issues of governance surrounding potable water reuse

It is crucial to recognize where the locus of policymaking is when thinking about the role and influence of communication and public understanding in the implementation of DPR projects. The question of who the policy actors are who are responsible for formulating and executing a DPR policy can be complicated.1 While on its face the answer to this question is often obvious – a City Council or a water agency board of directors – the locus of policy action is often more diffuse and complex. Key policy actors can also include agency staff (in situations where the governing bodies routinely defer to staff technical recommendations) as well as non-governmental organizations whose unofficial role in the policy process through informal governance networks affords them the role of de facto policymakers (Cairney Citation2016).

Stenekes et al. (Citation2006) and van Rensburg (Citation2016) discuss some of the difficulties and inefficiencies that exist because water institutions are not cohesive or integrated, creating obstacles for sustainable water planning. Stenekes et al. (Citation2006) explained that while elected local governments have traditionally made water decisions in Australia, newer governance structures have resulted in water decisions being made at a distance from representative government. Development of water-related institutions that allow for genuine community participation and incorporate local knowledge and values may improve negotiation, dialog, and decision making on water projects. Such community involvement adds “procedural justice and legitimacy” to the decision-making process (Stenekes et al. Citation2006, 124).

The literature suggests a complex relationship between the severity of the problem (long-term water scarcity and more immediate short-term drought) and the structure of governance. Unsurprisingly, water agencies have been found to be more likely to implement sustainable water policies under drought conditions (Mullin and Rubado Citation2017). While general-purpose governments (cities or counties for which water service is but one duty) have been shown to be more able to implement sustainable water policies than special districts (agencies created with the sole duty of water service), under crisis the performance difference between the two types of governance structures shrinks significantly (Mullin Citation2008).

For potable water reuse to be implemented, longstanding institutional structures must be modified to accept new ways of thinking about potable water supplies (Stenekes et al. Citation2006). Ching (Citation2010) hypothesized that, “informal water institutions will change rapidly when there is a sense of crisis, resulting in rapid learning and/or when there is a strong water leader with a persuasive message.” The author suggested that norms, partially shaped by the media, form around reuse policies, but can be disrupted resulting in the public overcoming its aversion to drinking purified wastewater. It has also been suggested that reuse of wastewater must, of necessity, reinforce the role of large-scale, centralized water management infrastructure and the governance structures that go with it (Meehan, Ormerod, and Moore Citation2013), whether via water departments within general-purpose municipal government agencies, or through special district agencies that deal solely with water and wastewater management.

2.5. Lessons learned from two well-documented potable reuse case studies

The experiences of two cities – San Diego, California and Toowoomba, Australia – that attempted to implement IPR have been well-documented in the literature. We briefly discuss some of the details here for a case-specific look at factors impacting public acceptance. At the time this paper was written, no such analyses were available for DPR experiences, likely because so few DPR facilities have been proposed.

2.5.1. San Diego

San Diego has long struggled with water scarcity and multi-year drought. The city began importing water from the Colorado River in 1947, and by 1990 up to 90% of its water supply was imported (Hartley Citation2006). In response to two periods of drought, San Diego introduced potable water reuse as an alternative supply option in the mid-1990s and again over a decade later (Trussell et al. Citation2002; USEPA, ReNEWIt, and The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread Citation2018), as discussed below.

A legal settlement required the city to build water reclamation capacity (National Research Council Citation2012), but the city could not use much of the reclaimed water for several reasons: it was cost-prohibitive to distribute the reclaimed water to an extended network of users, the water was too saline for some applications, and irrigators did not want the water in the winter. This lack of ability to put the reclaimed water to use led to an informal study, which suggested that IPR could be a cost-effective alternative for reusing the water. In 1993, the San Diego Water Authority led a more formal effort to determine the feasibility of IPR, which included discussions with the California Department of Health Services to understand any health impacts of IPR and public outreach to understand public support for the project. This scheme for augmenting the potable water supply was known as San Diego’s Water Repurification Project (Trussell et al. Citation2002).

The San Diego Water Authority assembled a panel of experts on drinking water and public health who reviewed and approved the proposed project. The Water Authority also assembled a citizen panel which reviewed the proposed project and recommended that additional studies related to project advancement proceed. The California Department of Health Services approved the project in concept following piloting of the treatment system that confirmed virus removal. The City Water Utilities Department became the project lead and began moving forward with preliminary project design in 1996. Up to this point, in addition to the citizen panel, the project had support from numerous entities, from local health, environmental, and business groups to the Region 9 EPA (Trussell et al. Citation2002).

Several issues occurred throughout the project progression that eroded public support for the project. First, shortly after the project was introduced, California experienced record rainfall, reducing the perceived urgency for an IPR project. Second, project control was shifted from the city’s Water Utilities Department to the Metropolitan Wastewater Department. While the latter department was thought to be better able to fund and construct the project, the transfer of control led the public to perceive the project as more of a scheme for wastewater disposal than a strategy for ensuring water supply reliability. Third, within the same timeframe that the IPR project was being developed, a major agriculture-to-municipal water transfer was being negotiated, which would provide for approximately half of San Diego County’s water needs (Trussell et al. Citation2002; USEPA, ReNEWIt, and The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread Citation2018).

While the Water Repurification Project retained its support from many political and community leaders, the project became a key issue during the 1998 campaign season. City council and state assembly candidates in particular criticized the project and incited fears about “drinking sewage” through direct mail campaigns and adverts in San Diego’s major daily newspaper, which opposed water reuse and supported the water transfer alternative. The candidates also accused the city of environmental injustice, incorrectly stating that the project targeted the city’s African American community (Trussell et al. Citation2002). The media and a few other vocal opponents waged a successful campaign against the Water Repurification Project by describing the project as “toilet to tap”, a term developed during opposition to a previous California reuse project, and introducing uncertainty about the safety of the IPR water. Also, the National Research Council had just released a report that was largely supportive of IPR, but called it “an option of last resort”, a phrase that was highlighted by project opponents. Additional technical and advisory boards and a grand jury reviewed the project and came to different conclusions about its acceptability. In 1999, the San Diego City Council voted to halt the project (Trussell et al. Citation2002). After years of significant investment, the Water Repurification Project was abandoned due to public pressure, which stemmed from local authorities’ failure to gain community trust (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003), inadequate information sharing, and failure to address public concerns, such as safety and environmental racism (Hartley Citation2006), among other factors (Trussell et al. Citation2002).

In 2004, seeing the need to further diversify the City’s water supply portfolio, the San Diego City Council called for an evaluation of all options to increase production and utilization of the City’s reclaimed water resources. This action initiated the City of San Diego Water Reuse Study of 2006, which provided a comprehensive analysis of all potential reuse alternatives, including options for IPR through reservoir augmentation (Asano et al. Citation2007; National Research Council Citation2012). The study discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the various options, but did not recommend a specific project. It also focused on health and safety considerations for the various water reuse options (Asano et al. Citation2007).

The City contracted the National Water Research Institute to create an Independent Advisory Panel, which provided substantial input and technical oversight for the study. The public was also engaged in learning about the various water reuse options and in helping to determine how to move forward with water resources planning. A variety of public meetings, expert speakers, and “communication opportunities” were used to facilitate “dialog and information sharing with city residents and the study team” (Asano et al. Citation2007, 1334). Workshops that brought together numerous stakeholders – with participants selected by the mayor’s office, city council, and other groups from around the city – were deemed as especially important to the effective public dialog on issues surrounding water reuse (Asano et al. Citation2007). The City of San Diego’s website (as of June 18, 2019) states that this broad-based citizen stakeholder group, called the American Assembly, played an “essential role” in determining how to proceed with water resources planning.

According to the City of San Diego’s website (as of June 18, 2019), the Water Reuse Study American Assembly group “identified Reservoir Augmentation at the City’s San Vicente Reservoir as their preferred strategy,” and, in 2007, the City Council voted to proceed with this alternative and evaluate its feasibility for full-scale implementation. Full-scale feasibility was to be evaluated using a Demonstration Project, which was funded through a temporary water rate increase from 2009-2010 (City of San Diego Citation2013). Around this time, the City of San Diego’s website (as of June 18, 2019) describes how 23 diverse local organizations joined to form the Water Reliability Coalition in support of the Demonstration Project. The broad-based coalition was said to be, “instrumental in maintaining momentum for the Demonstration Project by attending and providing testimony at City Council and other civic meetings,” and in providing an “independent voice about water purification and the need for a sustainable water supply for San Diego.”

This time around, when the San Diego Public Utilities Department reintroduced the IPR project, it was called Pure Water San Diego, and the department made public outreach and engagement a priority (USEPA, ReNEWIt, and The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread Citation2018). Part of its successful public education program involved tours and events at the Demonstration Project (USEPA, ReNEWIt, and The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread Citation2018), which opened in 2011 as the “Advanced Water Purification Facility” (City of San Diego Citation2013) and produced 3.7 million liters per day (1 million gallons per day) (USEPA Citation2017). More than 20,000 members of the public toured the facility, and public acceptance of potable water reuse increased from 26% in 2004 to 73% in 2012 (Atkinson Citation2014). The City of San Diego’s website (as of June 18, 2019) describes numerous additional ways that the City built on the outreach and education activities established during the Water Reuse Study; for example, they created web videos showing conservation commitments from local leaders, hosted poster and film contests to engage young audiences, and worked with media outlets to ensure dissemination of accurate information. In short, San Diego’s second contemplation of a potable reuse project demonstrated a commitment “to a robust public outreach and education effort before delving too deeply into planning”, which was likely critical to the project’s success and the reason it had broad public support (USEPA, ReNEWIt, and The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread Citation2018, 11). The City of San Diego’s website (as of June 18, 2019) notes that the first phase of the new IPR facility is expected to be online in 2023.

The governance structure may have been another important factor in decisions about whether to pursue potable reuse. The greater San Diego metropolitan area is served by a wholesale water agency, the SDCWA, which delivers supplies of imported water to the region’s 24 local water retailers, primarily municipalities. The largest of those local retailers is the City of San Diego. San Diego water management represents an example of “polycentric governance”, with overlapping areas of responsibility for water (Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren Citation1961).

During debates over the first iteration of San Diego’s water reuse proposal, the decision makers were the elected officials of the San Diego City Council. While the SDCWA also was involved (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003), the arena of action was the directly elected City Council members of the municipal government. Technical evidence is only one of several, sometimes competing and conflicting, sources of information that may influence decision makers (Cairney Citation2016). In the case of directly elected officials with jurisdiction over the San Diego water agency, political pressure by project opponents was sufficient to overcome the arguments of technical experts in influencing the Council members’ decision. Direct voter influence on the water management process of this sort has been shown to make sustainable water management decision-making more difficult (Kwon and Bailey Citation2019).

Around the same time potable reuse was reintroduced years later, three entities came together to form a broader governance entity. The SDCWA, the city of San Diego, and San Diego County formed the Regional Water Management Group (RWMG). Such regional institutions do not replace existing institutions, “but rather become a forum for deliberation and planning” at a broader scale and level than is possible by the individual member institutions (Hughes and Pincetl Citation2014, 20). According to the City of San Diego Public Utility Department’s website, RWMG funded, guided, and managed the development of the Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) Program. The IRWM Plan and grant applications were formally approved and adopted by the governing bodies of these three agencies. Thus, San Diego’s IPR project was moving forward along with development of regional water governance. However, as discussed above, perhaps the most important difference in San Diego’s two attempts to introduce IPR was that stakeholders (the American Assembly group and the Water Reuse Coalition) were more actively involved in the decision-making process the second time around.

2.5.2. Toowoomba, Australia

Toowoomba is a community of approximately 115,000 people located 161 kilometers inland from Brisbane, Australia. Due to persistent drought, the city implemented low-level water restrictions in 2002. Within four years, restrictions were increased to the highest level. By that point, the population was well-aware of the city’s water scarcity problems (Fishman Citation2011).

At a Ladies Club gathering in May 2005, the mayor of Toowoomba announced, “You are all going to drink from the sewer” and discussed a water reuse plan that had developed over the previous six months. This was the first time residents had heard about a plan for potable water reuse in their community (Fishman Citation2011). This incident occurred a month before the City Council unanimously supported securing federal funding for the project (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010).

On July 1, 2005, the City Council announced the Water Futures Initiative as a forum for discussing solutions to the city’s water scarcity problems; the initiative was described as more of a bureaucratic formality than a meaningful attempt at public outreach (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010). On July 21, 2005, Citizens Against Drinking Sewage (CADS) was formed, and a month later, CADS held its first public meeting, which drew over 500 citizens and provided a forum for discussing possible dangers of water reuse. CADS took out full-page newspaper advertisements telling readers, “You deserve fresh water,” and calling project supporters “sewer sippers”. Instead of showing clear drinking water from the WTP, the local media displayed images of large brown pools from the WWTP (Morgan and Grant-Smith Citation2015). By February 2006, CADS had obtained 10,000 signatures on a petition against IPR (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010).

The public was aware of water scarcity, but it was not aware that the local government was planning an IPR project until CADS brought it to their attention. When the public heard about the project from CADS instead of local government officials, it felt that the project could not be trusted (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010). The local government lacked transparency while developing the project, and all attempts to appease and educate the community came after concerned local citizens distributed information against IPR.

Because of the swell in public opposition, the federal government announced plans for a referendum on IPR. Only then did the City Council initiate a 10-week public information campaign – eight months after CADS began educating the public. The referendum was held in July 2006; 62% of the public opposed the project (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010).

Toowoomba’s governance structure permitted direct involvement by project opponents. In Toowoomba, the City Council was initially responsible for the project, meaning that the policy actors were directly accountable to voters (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2010; Fishman Citation2011). The local governing body was unmoved by project opposition. However, the need for federal funding created an added layer of governance, providing a second arena of action for project opponents. The federal government agreed to pay for the project only if it was endorsed by the people of Toowoomba in a referendum (Stenekes et al. Citation2006). The multiple layers of governance provided multiple opportunities for opponents to stop the project.

3. Key factors of importance for contextual analysis of DPR projects

While much research has been conducted on public education and factors influencing public acceptance of potable reuse, Stenekes et al. (Citation2006) called for additional studies that incorporate a more context-based analysis of the issues, including the institutional frameworks involved in water infrastructure planning – especially in actual cases where reuse was being considered, rather than hypothetical scenarios. The authors stated that much of the existing research on public acceptance of reuse does not consider the complexity involved in actual planning and management processes.

Based on the literature reviewed above and Stenekes et al.’s (Citation2006) recommendations for future research on actual cases of potable reuse implementation, we believe that the following are important to an analysis of issues influencing public acceptance of potable water reuse: (1) existing community conditions related to water scarcity, feasible water supply options, and public perceptions of scarcity; (2) the mode of project introduction and characteristics of DPR education and outreach programs; (3) public trust in agencies, organizations, or public officials introducing and/or promoting the DPR project; (4) the kind of media attention given to the project; and (5) the system of governance defining the policy actors responsible for formulating and executing the DPR project and the scale of the water service being provided, which is closely related to the capacity of the governance institutions (i.e., the resources they have to carry out the complex reuse task).

In this paper, we look at these issues in the context of five inland US communities where the public accepted DPR. No previous water reuse studies have focused on public acceptance of DPR specifically, and few have considered the inland context. Our analysis of primary data on factors influencing DPR acceptance by communities of varying size in the inland US is unique in the literature to date.

4. Methods

4.1. Selection of communities for collection of primary data

At the time of this research project, DPR had been accepted by the public in five US communities located in the inland southwest: Cloudcroft in New Mexico, and Brownwood, Big Spring, Wichita Falls, and El Paso in Texas. To the authors’ knowledge at that time, these were the only communities in which DPR had been proposed to the public, aside from what was mentioned in the above literature review. We were unaware of instances where DPR had been proposed but not accepted by the public. Through interviews, we documented information pertaining to the key factors of importance for contextual analysis of DPR projects.

4.2. Interviews

We conducted interviews with city officials and water managers where the public had accepted DPR in the US. Some interviews were conducted after DPR implementation had already occurred, while others happened following public acceptance, but before implementation. Interviews were semi-structured to accommodate discussion of other issues of importance to the interviewees.

Eight professionals from the five communities were interviewed. The interviewees had titles such as Lead Water Operator, Director of Public Works, General Manager, and Utilities Operations Manager. Interviewees were selected based on their involvement in DPR through the public entities or organizations for which they worked; knowledge of their involvement was gained from reading, watching, or listening to interviews they had done previously with various news outlets (e.g., television, radio, newspapers, and trade magazines). Potential interviewees were contacted by email or phone with a request to participate; they were also provided with the list of proposed interview questions. All potential interviewees who were contacted agreed to participate. The technique of snowball sampling was used in an attempt to learn about additional potential interviewees, but often there were only one or two people who were knowledgeable enough to answer our interview questions, especially in the case of the smaller communities.

Each interview was conducted by phone and lasted 45 to 60 minutes. Interviews were transcribed immediately following each phone call. Seven interviews were conducted in July and August of 2015, and the last interview was conducted in May of 2016.2 Details regarding interviewees’ titles, interview dates, and the interview questions are shown in the online Supplemental Materials. All interviews and related research were conducted in compliance with the University of New Mexico’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).3

4.3. Review of other publicly-available documentation

Publicly-available materials from the five communities were analyzed for additional information about the DPR-related public engagement, education, and outreach processes that were used. Examples of such materials included trade magazines, newspapers, public meeting minutes, city and water authority websites, and YouTube videos.

5. Results: New data on DPR introduction in five inland communities in the US

5.1. Cloudcroft, New Mexico

5.1.1. Water scarcity conditions and public perceptions of scarcity

Cloudcroft is located in the mountains of southern New Mexico, with about 800 full-time residents. The population often more than doubles on weekends due to tourism, which is the village’s primary industry (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011; Livingston Associates Citation2009). Its water agency is capable of serving some 3,000 people (USEPA Citation2019), making it the smallest project studied. Cloudcroft’s water sources include spring and well water; however, drought conditions have reduced the supply to below demand and exploration for additional groundwater found no new supplies. Even with conservation, the village has had to truck in water to meet demands (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011; Livingston Associates Citation2009).

According to University of New Mexico Professor Bruce Thomson who has worked with the Village (personal communication, August 12, 2015), water scarcity combined with hauling in supplemental water made Cloudcroft’s need for alternative water sources more pressing. In 2006, Cloudcroft decided to implement DPR. The solution envisioned by Village leadership was the PURe Water Project, a facility to treat wastewater to better-than-drinking-water quality utilizing a multi-barrier treatment approach. Purified water would be blended with native sources prior to distribution (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011).

5.1.2. DPR project introduction and characteristics of education and outreach programs

According to the New Mexico Environmental Department’s website (as of July 10, 2016), since community awareness of water scarcity was already high, there were no formal education and outreach campaigns. Instead, the Village Administration held three public meetings where water supply options were discussed. Few had concerns about the proposed DPR water quality (Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011; Livingston Associates Citation2009). The most significant concerns were the cost and the possibility of a rate increase. For very small communities, such as Cloudcroft, the cost of operating a DPR system can be prohibitive (Scruggs and Thomson Citation2017). However, according to Professor Thomson (personal communication, August 12, 2015), the Village acquired several state and federal grants to build the DPR facility, and without considering future operating and maintenance expenses, the community moved quickly to implement DPR at no initial cost to residents. Construction of the DPR facilities began in 2009.

Faulty construction resulted in a schedule delay so significant that treatment technologies had changed by the time construction re-started, requiring process configuration retrofits and new equipment; eventually, the first system was abandoned. Despite the setbacks, the Village still plans to implement the PURe Water Project, although officials are not certain about the schedule for project completion.

5.1.3. Public trust in the entities and individuals introducing and/or promoting the DPR project

City officials engaged the public in the decision-making process regarding new sources of potable water. According to Cloudcroft’s Lead Water Operator, because Village leaders were transparent and made the search for, and deliberation of, water supply options a public conversation, lack of trust among the public regarding local officials did not seem to be an issue. Consequently, public acceptance was easily gained and the community was enthusiastic about the project.

5.1.4. Media outreach and coverage

There appears to have been no local media coverage of Cloudcroft’s PURe Water Project.

5.1.5. Cloudcroft governance

Cloudcroft’s decision was entirely in the hands of local government. But the funding, another potentially controversial feature of reuse projects, came from outside the local community, creating a bifurcated decision process. The Village is governed by directly-elected Village Councilors and a mayor, and the Water and Wastewater Department is a division of its municipal government, according to the New Mexico Municipal League’s website (as of July 10, 2016). Thus, the primary policymakers with jurisdiction over the decision about whether to proceed with the project were directly accountable to voters. Importantly, however, funding for the project came from state and federal governments creating a separate layer of governance and removing responsibility for that part of the project – and a potential source of opposition – from local taxpayers or utility ratepayers.

5.2. Brownwood, Texas

5.2.1. Water scarcity conditions and public perceptions of scarcity

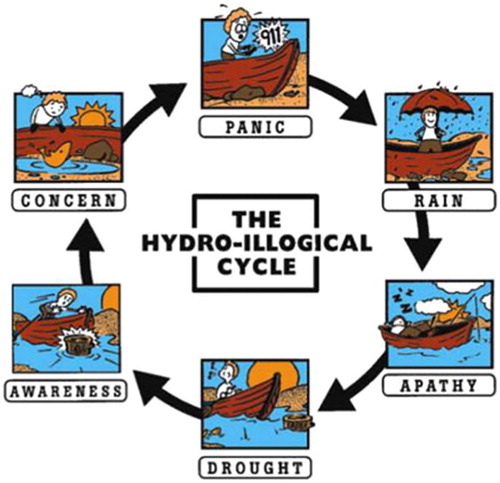

Brownwood is in western Texas. Its water utility serves a population of 19,000 (USEPA Citation2019), making it a very small water service provider. According to the Brownwood Public Works Director, the area began experiencing drought in 2007. By 2011 severe water rationing and mandatory conservation were enforced, making the public acutely aware of water scarcity. Due to the severity of the drought and lack of other water supply options, the city began considering water reuse. In 2012, Brownwood became the first city in Texas to obtain approval for DPR from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). The final step needed to start construction of a DPR facility was City Council approval of a $12 million bond sale. However, the City Council never voted to approve the sale of bonds because it began to rain. The Brownwood Public Works Director cited the “Hydro-Illogical Cycle” () in describing the fate of the DPR project in his community:

The city is in the ‘apathy’ phase of the ‘Hydro-Illogical Cycle’ because we are getting rain. It started to rain, and for the first time since 2007 water has gone over the spillway. However, we should not wait until we reach the ‘panic’ phase of the cycle to act; there must be a plan beforehand. We need to recycle. If we recycle water, we have more water in the lake for wildlife, recreation, and to bank for the future.

The Public Works Director explained that the groundwork for DPR has been laid in case the city experiences severe drought again. With public acceptance, a facility design, approval from TCEQ, and a funding mechanism already in place, the facility could be fully operational within 16 months.

5.2.2. DPR project introduction and characteristics of education and outreach programs

Brownwood’s proposed DPR project was presented to the Rotary Club, the Lions Club, the Chamber of Commerce, and the City Council. The Public Works Director believed that it was best to present the project to community leaders and let them spread the word. He said that gaining public acceptance of DPR was not an issue and credited the city’s well-established education and outreach program on water: for two decades, the WWTP has offered tours to residents of Brownwood and neighboring cities. Brownwood’s fourth grade curriculum includes learning about urban water reuse and a tour of the city’s WWTP. Also, the local chamber of commerce has a long-standing program called Leadership Brownwood, a 12-week program that helps young professionals gain knowledge of the community and visit facilities, such as the WWTP. In addition, community service organizations such as the Rotary Club, the Kiwanis, and the Lions Club can request periodic updates from the water authority to educate club members about water reuse and related topics.

The Public Works Director believed that almost everyone in the community had been to the WWTP. He had no recollection of any DPR opposition and said the city received letters of support for DPR from industry, businesses, and the local university.

5.2.3. Public trust in the entities and individuals introducing and/or promoting the DPR project

The Public Works Director believed public trust was high since the city quickly gained public acceptance of DPR. Further, he explained, “Because city officials are very open, the public does not feel like there is information asymmetry and believes that city officials have their best interests at heart.”

5.2.4. Media outreach and coverage

City officials reached out to the local media before introducing the DPR project to the public. They explained the water purification process and the need to incorporate DPR into the city’s water portfolio, and requested the media’s help in educating the public. The Public Works Director found the media to be very supportive. He was a frequent guest on the local talk radio show to discuss DPR and how it could make the city’s water supply more resilient.

5.2.5. Brownwood governance

In Brownwood, the entire decision-making process – both about reuse and the funding for reuse – lay at the local level. Brownwood’s Water and Wastewater Department is governed by the City of Brownwood and is under the Department of Public Works, which reports through a city manager to elected City Councilors and a mayor. The city manager-council form of government has been shown to be generally more effective in developing sustainable municipal water policies (Kwon and Bailey Citation2019). Decisions about reuse are made by policymakers who are directly accountable to the voters of Brownwood, but filtered through an unelected city manager. Importantly, funding decisions were also in the hands of the City Council through a proposed bond issue that would have been repaid by users of the water system.

5.3. Big Spring, Texas

5.3.1. Water scarcity conditions and public perceptions of scarcity

The Colorado River Municipal Water District (CRMWD) serves the cities of Odessa, Big Spring, and Snyder, which collectively provide water service to approximately 135,000 people (TCEQ Citation2019), making it a mid-sized service provider. According to CRMWD’s Operations Manager, the decision to implement DPR was unique in that the region was not in a drought when staff began looking for alternative water sources to increase supply reliability. However, it was clear that the area could not continue to grow without a more diverse water portfolio.

CRMWD’s General Manager explained that IPR was not feasible because the district did not have room for a new reservoir and a suitable aquifer was not available. Since area groundwater is brackish, the possibility of desalinating brackish water emerged as one of the two primary options for consideration, along with DPR. Results of a 2003 feasibility study found DPR to be less expensive.

In 2008, a detailed design of the DPR facility was completed. In 2009, CRMWD purchased property for the new facility, began pilot testing, and started the permitting process. In 2013, the CRMWD began operating the US’s first DPR plant, which could treat up to 7.5 million liters per day of wastewater effluent to drinking water standards. The CRMWD website (as of November 14, 2015) explains that while some Texas cities benefited from rains in 2015 that filled their reservoirs, the reservoirs near Big Spring remained at a fraction of their capacity, and the new DPR plant provided needed supply reliability.

5.3.2. DPR project introduction and characteristics of education and outreach programs

In 2005, the CRMWD General Manager and the Water District Engineer presented the DPR concept and an explanation of the purification process in public town-hall style meetings in the cities served by CRMWD. Public meetings continued through 2007, and the public was encouraged to call CRMWD to ask questions or to request additional presentations to clubs and associations. According to the CRMWD General Manager,

Initial public approval was easy. Getting permission from the Texas government to move ahead was the hard part. The idea was well received by the public, and in a meeting presented in Midland, a man joked that the idea was great because he would get to drink his beer twice.

He also noted that gaining community support for DPR was not as difficult as some might expect, despite the “yuck factor” often associated with potable water reuse. He attributed public support to West Texans’ deep appreciation for water, the outreach and education programs, and media assistance, explaining, “Although there were concerns, most people were okay with it once we provided them with information.”

5.3.3. Public trust in the entities and individuals introducing and/or promoting the DPR project

The CRMWD District Manager did not perceive problems related to public trust in the officials and agencies involved in project planning or implementation because of the open public processes. He believed the public felt that it was given all the information it needed to form an educated opinion of the project and officials were transparent throughout the process.

5.3.4. Media outreach and coverage

There are three media markets in the area around Big Spring—television, newspaper, and radio—and CRMWD contacted all of them about the DPR project. According to the CRMWD General Manager, the media was accustomed to writing about water reuse and it was helpful in reporting the news fairly and accurately. A reporter from the local newspaper, The Big Spring Herald, estimated the number of articles written on the project since the early 2000s to be “in the hundreds.” Since Big Spring was the first DPR facility in the nation to serve customers, it also made national headlines. The General Manager felt that the national media treated the event differently: “Unlike the local media, the national media created the news instead of reporting it, and gave it a negative spin”.

5.3.5. Big Spring governance

The governance for Big Spring’s DPR decision was through a special district one step removed from direct voter involvement. CRMWD is a wholesale raw water provider, providing water to over 135,000 people in the district and several additional small communities in the region. CRMWD’s customers send the water to their own treatment plants before making it available to ratepayers. CRMWD staff, under policies set out by a Board of Directors, make all decisions related to water supply sources and treatment prior to distribution to customers, subject to approval by the TCEQ, per the CRMWD website (as of September 12, 2016). The members of the CRMWD Board of Directors are appointed by the City Councils of the cities served by the CRMWD. As the policymakers responsible for the potable reuse decision, the CRMWD’s members are thus one step removed from influence by voter sentiment. Given that the Water District acted in the absence of explicit drought conditions, Big Spring is an unusual case that runs counter to findings that suggest special districts are less likely to undertake major sustainability initiatives in the absence of a crisis (Mullin Citation2008).

5.4. Wichita Falls, Texas

5.4.1. Water scarcity conditions and public perceptions of scarcity

Wichita Falls is in north central Texas, with a water agency serving approximately 150,000 people (TCEQ Citation2019), making it a mid-sized service provider. In 2012, city reservoirs were at less than 20% capacity, and groundwater was not available as a backup supply. The region had a brackish lake, and the city previously installed an advanced water treatment system to treat the lake water for potable use. In anticipation of a water scarcity crisis, city officials looked to Big Spring’s example and determined that DPR was a viable means of meeting potable water demands. The local population was well aware of water scarcity.

Since an advanced water treatment system for the lake water already existed, the city did not need to build a new facility for DPR, allowing for quick implementation. A 13-mile above-ground pipeline was built to connect effluent from the WWTP to the advanced treatment system at a cost of $13 million. The pipeline was completed in December 2013, and the TCEQ approved a permit for treating WWTP effluent in June 2014. It took 27 months – from the first meeting between the city and water officials of Wichita Falls and the TCEQ – to obtain the required permit for DPR. The system came online in July 2014, providing 18.9 million liters of potable water per day (1/3 of the city’s daily demand).

Once the drought was over, the city reconfigured the system to operate as IPR, delivering treated wastewater to Lake Arrowhead instead, as noted in a Wateronline article dated December 26, 2016. Prior to the water scarcity crisis, the city had been planning to implement IPR, so the reconfiguration was consistent with the city’s long-range water supply plan.

5.4.2. DPR project introduction and characteristics of education and outreach programs

City officials in Wichita Falls made public communication and outreach a priority. Early in the drought, before presenting DPR to the public, city and water officials engaged the city’s doctors, university professors, and the media to ask for their support. The City of Wichita Falls’s website (as of November 21, 2015) explained how water and wastewater treatment plant staff first presented the public with the DPR proposal in February 2013, as drought prompted them to limit lawn watering. Soon after, city officials held an emergency press conference at Lake Arrowhead using the lake at 40% capacity as the backdrop, visually highlighting the problem of water scarcity. The mayor opened by talking about water conservation efforts and the importance of conservation during the drought. He was followed by the City Manager who introduced the water reuse project that city officials planned to implement. The Public Works Director and the Assistant Director of Health spoke about the necessity of DPR in Wichita Falls and how public safety would be ensured.

The Public Works Director used the media, town halls, meetings with local organizations, and YouTube videos (which were also broadcast on the local news) to further educate the public about water conservation and the DPR project. Some videos featured utility representatives, doctors, and experts from local universities who talked about the treatment process and the safety of potable water reuse. The city considered these videos to be a success. The water utility also set up a hotline to handle community members’ questions and concerns about DPR, though few people called.

When asked about the effect of the outreach and education campaign on public acceptance, Wichita Falls’s Public Works Director explained,

Technology is easy. The hard part is public acceptance. You must put a name and face on the project, and people should know what the money is going for. [In Wichita Falls], people knew what the money was going for, and the public believed in the project.

The Utilities Operations Manager, added, “There was some initial skepticism, but in very little time there was 100% acceptance”.

5.4.3. Public trust in the entities and individuals introducing and/or promoting the DPR project

The Utilities Operations Manager believed the public felt that city officials were acting in their best interest. When asked why he thought the Wichita Falls community accepted DPR, he said,

It is very easy to distrust public officials and we knew that from the start. We were very transparent and hid nothing from the public. We talked to the public about the treatment, the levels of treatment, the steps we took with the state. We brought in medical and university professors and asked for the public’s approval. We pulled back the curtains. We wanted them to get the information from us and not to get some sort of wrong information off the internet.

5.4.4. Media outreach and coverage

The media was contacted very early in the process, and media outreach was integral to the public education and outreach campaign described above. The Wichita Falls Public Works Director stated, “[We told the media] ‘This is the news we need you to get out there.’ The media was awesome. There was some sort of news—either newspaper or TV—on the subject daily.”

A few times the entire six o’clock news was dedicated to the drought and DPR. The city’s mayor perceived a lack of public concern about DPR and attributed it to the success of the media outreach efforts.

5.4.5. Wichita Falls governance

Wichita Falls water service is provided by the Department of Public Works of the City of Wichita Falls. Public Works reports through a city manager to an elected City Council and mayor. The policymakers are thus directly accountable to voters, filtered through the actions of a professional manager, a governance structure that has been found to be more conducive to sustainable water management policies than via directly elected mayor and city council or a special district (Kwon and Bailey Citation2019, Mullin Citation2008).

5.5. El Paso, Texas

5.5.1. Water scarcity conditions and public perceptions of scarcity

El Paso is in western Texas, and its water utility serves nearly 750,000 people (TCEQ Citation2019). According to the Texas Water Development Board’s website (as of July 20, 2016), the city experiences some degree of drought at least once every decade, so there is great awareness of water scarcity among residents. In the 1970s, the Texas Department of Water Resources developed hydrologic models that predicted the region would run out of water by 2010 due to a decline in groundwater and an increase in water demand. Although the predictions were not realized, they did raise awareness that the region needed to diversify its water supply portfolio. Recent conditions have kept water scarcity on residents’ minds: a drought lasting from August 2010 to October 2014 ranks as the second most severe and the second longest on record, and 2011 is considered the worst one-year period of drought on record.

The El Paso Water Utilities (EPWU), as described on its website (as of January 7, 2016), has been a pioneer in water reuse, delivering reclaimed water to the community since 1963 and operating one of the most extensive and advanced reclaimed water systems in Texas for industrial and landscape irrigation. The city is also home to North America’s largest brackish groundwater desalination facility, which opened in 2004, and an IPR facility, which opened in 1985. For the upcoming DPR plant, which should be online by 2020, El Paso will treat a portion of the effluent from the local WWTP in an advanced water purification facility and the purified water will augment the potable water supply.

5.5.2. DPR project introduction and characteristics of education and outreach programs

Public outreach for the new DPR facility began in June 2015. Residents could tour a pilot facility that was built on the site of the proposed full-scale facility. Fact sheets on DPR were distributed to pilot facility visitors. The EPWU created a water reuse education program and provided speakers for clubs, schools, and businesses to explain the project and the treatment process.

City officials built on past public outreach and education experiences in developing their DPR effort. Outreach and conservation programs began decades ago as a response to the hydrologic modeling results of the 1970s, including a program to educate elementary school children about conservation strategies.

5.5.3. Public trust in the entities and individuals introducing and/or promoting the DPR project

According to the Vice President of Marketing and Communications, due to longstanding water scarcity in the region, El Paso residents and EPWU saw the need for collaboration, which included mutual trust and cooperation. This collaboration has fostered numerous water management strategies since 1991, and a successful water conservation program has been in place for decades. Because of El Paso’s history with safely implementing other forms of water reuse and desalination, the community already had an existing relationship of trust with EPWU and a familiarity with water from alternative sources.

5.5.4. Media outreach and coverage

Following the examples of Big Spring and Wichita Falls, one of the first steps EPWU took in introducing DPR was to educate the media about the need for the DPR facility and how it would work. Through this outreach and education, EPWU staff felt that they could get the media “on board” with accurate reporting and coverage related to the plant and other water scarcity issues. According to the Vice President of Marketing and Communications, the El Paso Times regularly features data related to local conservation efforts on its front page.

5.5.5. El Paso governance

The EPWU is, for financial and legal reporting purposes, a part of the City of El Paso’s municipal government. But, as described on the EPWU’s website (as of March 15, 2015), since 1952 it has been operated as a quasi-independent agency. It is governed by a Public Service Board that consists of the city of El Paso’s mayor and six residents of El Paso County who are appointed by the El Paso City Council. Policy decisions are thus one step removed from officials who are directly responsible to voters, a hybrid of direct municipal operation as part of a general-purpose government (the city) and a special district (by virtue of its independent board).

provides a summary of each community’s service area, whether education and outreach occurred, the type of media coverage received, the public’s awareness of water scarcity, and whether opposition groups formed in response to DPR project introduction.

Table 1. Summary of community information related to DPR introduction.

6. Discussion

Although all communities mentioned in this paper experienced water scarcity, how residents viewed or understood water scarcity and its possible solutions differed. Ormerod and Scott (Citation2013, 353) demonstrated that “potable reuse is a politicized issue, where expressed concerns reflect social values more complicated than simple revulsion” and individual perceptions of scarcity are shaped by local context. In addition to perceptions of water scarcity and climate conditions, the local context surrounding a water reuse project includes the people, authorities, and institutions that initiate discussions about water reuse, public trust in those authorities, and how public outreach and communication is conducted. Other local context details – such as whether public conversations about potable reuse started prior to project introduction or whether ongoing water-related educational programs existed – also appear to be of critical importance to public acceptance of DPR.

Based on our interview findings, all five of our case study communities in Texas and New Mexico felt the crisis of water shortage and experienced it in different ways. Others have previously pointed to the importance of long-term public education around water resources – including conservation programs, public tours, in-school education, and community outreach – to the success of IPR projects (Wegner-Gwidt Citation1991; Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003). However, not all of our DPR case studies presented here – Cloudcroft, for example – had these types of intentional, formal, long-term education and outreach programs. In addition, Cloudcroft was the one community from our case study collection that did not reach out to the media. Following Ching (Citation2010), we propose that while such education programs and media coverage are important, especially in larger communities where some residents may not personally experience the effects of drought and water scarcity, at least one other factor may act as a substitute for long-standing public education and media coverage in influencing public acceptance of DPR: a daily lived experience with the effects of drought or water scarcity, which helps create a sense of crisis. Cloudcroft residents were hauling water into their community to keep up with demand, and through groundwater exploration investigations they understood that they had tapped all of their available freshwater resources. Further, with only 800 full-time residents in the community, the pubic meetings held to discuss options to increase the local water supply likely succeeded in truly engaging the public, incorporating community values into the solution rather than simply gauging community acceptance of predetermined options – a point that was emphasized by Stenekes et al. (Citation2006). Clearly, in the case of Cloudcroft, the norms formed around reuse policies were disrupted, resulting in the public overcoming any aversion to drinking purified wastewater (Ching Citation2010), even without formal, long-term education and outreach programs and media coverage. What is unknown, however, is whether the community would have accepted DPR had the residents been responsible for the project’s high capital costs (Scruggs and Thomson Citation2017), since costs have been shown to be an important factor in public acceptance (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003).

For other communities included in our study, our data reinforce previous findings that a combination of water conservation programs, facility tours for the public, and in-school and community education and outreach programs promote public acceptance (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003; Tchobanoglous et al. Citation2011; Lohman Citation1987). Acceptance is thought to increase when communities with cyclical conditions of drought maintain ongoing public education and outreach programs. For example, Brownwood and El Paso have longstanding water conservation, education, and outreach programs that include in-school education and facility tours.

Previous research has also emphasized that a traditional project introduction approach of “Decide, Inform, Defend” or conducting public education and outreach after project conception is often inadequate or unsuccessful (Po, Kaercher, and Nancarrow Citation2003; Simpson Citation1999). However, the approach of conducting public education and outreach specific to DPR after project conception apparently worked in most of our case study communities; the exception was Cloudcroft, which did not have a formal education and outreach program on DPR. In these cases, it is likely that community understanding related to water scarcity and the lack of alternative supply options, along with public education programs and extensive positive media coverage, were of critical importance to public acceptance. As examples, interviewees mentioned Texans’ intense appreciation of water, communities experienced strict water rationing, and/or residents could see their primary drinking water reservoir drying up. Officials explained to residents that there were no other water supply options, and residents likely believed them – public communications about DPR came from the local water and wastewater treatment plant staff and other entities promoting DPR (rather than outside public relations consultants), a strategy shown to build public trust and support (Bridgeman Citation2004; Harris-Lovett et al. Citation2015). Another difference from some previous studies was that DPR was not already a topic of discussion in our case study communities, giving local officials the opportunity to educate the public and media using their own messaging and terminology, rather than starting with what was already disseminated by opposition groups. Community leaders in Big Spring, Brownwood, Wichita Falls, and El Paso worked closely with media outlets to provide accurate technical information from the outset, resulting in objective media coverage and precluding the opportunity for opposition groups to reach the public first with misinformation.