Abstract

Sweden is considered an environmental sustainability pioneer, targeting a 50% reduction in energy use in buildings by 2050. This ambitious goal requires the active engagement of municipal actors and the building sector. Dialogue processes have been identified as a way to mobilize such engagement, but in earlier research, there has been a lack of studies where dialogue practices are analyzed in real-time and on location and where the role of leadership has been scrutinized. Taking two cases in Malmö as a starting point, the aim of this paper is to analyze the interconnections between dialogue models and the local context and to examine how the role of process leadership affects exchanges between included actors. The results show that it is difficult to create guidelines useful in the local context and that learning was embedded in the doing and was transferred through the process leaders.

1. Introduction

In the EU, 35% of the buildings are over 50 years old and 75% are energy inefficient (European Commission Citation2018). These staggering numbers call for a response. Sweden is considered a pioneer in environmental sustainability, and the Swedish parliament has targeted a 50% reduction of energy use in buildings by 2050 through replacing existing buildings with new ones or through renovating existing buildings to attain the same energy performance as that of new buildings (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013; Government Bill 2005/06). Accordingly, several municipalities have received grants from the national government to conduct locally based sustainability and climate-related investment programmes in collaboration with private actors, other municipalities, and regional and national public authorities (Granberg and Elander Citation2007). In the effort to achieve sustainability goals, the building sector has been identified as a productive locus of intervention, as buildings have a higher energy saving potential than do other sectors of the economy (Kivimaa and Martiskainen Citation2018; Kivimaa et al. Citation2019). However, this sector has been slow to implement energy efficiency measures (Kivimaa and Martiskainen Citation2018; Palm and Reindl Citation2018). There is lack of engagement by property owners and property developers in investing in the environmental, social, and economic sustainability of their housing stock. Inertia has been encountered as an internal barrier, and lack of knowledge, resources, and solutions as external ones (Jensen and Maslesa Citation2015; Palm and Reindl Citation2018). The building sector appears to have a conservative culture in which the established actor roles require renewal and there is a lack of interest in environmental issues (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019), challenging policy makers and practitioners alike.

In this article, we examine how dialogues between property owners or property developers and the city of Malmö are used with the aim of contributing to the implementation of environmental goals in residential areas. The dialogue models we describe take place within the paradigm of collaborative, or communicative planning. The premise of this approach is the inclusion of stakeholders in the process, as they are expected to impact the plans produced. Collaborative planning is concerned with the democratic management and control of urban and regional environments and the design of less oppressive planning mechanisms (Harris Citation2002; Healey Citation1997). Recent decades’ developments illustrate the benefits of applying collaborative approaches (Fenton et al. Citation2015; Healey Citation1997; Innes and Booher Citation2003). Collective action among actors on multiple levels of society is viewed as a potential solution for attaining a sustainable future (Linnenluecke et al. Citation2017). Collaborative planning has been credited for enabling collective action (Rydin Citation2014). Collective action, in its own turn, is enabled by the creation of common identity and purpose, by encouraging participation, by making collective action enjoyable, and by the creation of channels for communication that ease the flow of communication (Rydin Citation2014). Dialogue-based models of stakeholder engagement have become central instruments in these processes.

The city of Malmö, Sweden’s third largest, has engaged in intensive collaborative processes to support sustainable development since the turn of the 21st century. Property owners and property developers are essential actors to be engaged in sustainable urban planning for ambitious sustainability programmes to be implemented, because they own much of the physical space in municipalities. As Swedish municipalities do not have the authority to regulate the technical properties of buildings, “strategic housing dialogues” with the city’s property owners and developers are the tools Malmö has been using for promoting voluntary action, and for boosting sustainable housing construction (Malmö stad Citation2018). Dialogue between different actors is believed to promote the exchange of perspectives and yield new knowledge, which is often an important prerequisite for understanding and addressing complex urban challenges.

In the existing research on dialogues we have identified a lack of practice-based approaches, that would enable dialogue practices to be analysed in real time and on location. Dialogues are conceptually based on the work of American pragmatists, as well as on Habermas’ notion of communicative rationality (Innes and Booher Citation2010). Habermas' work urges for the creation of ideal speech situations, where all parties have equal rights to express themselves and engage the expression of others (Habermas Citation1984). This approach has been criticized for disregarding cultural diversity, power discrepancies and the potential of individual agency to transform structures (Healey Citation1997), issues which arise in the day-to-day practices of urban planning. Taking on a practice-based approach could surpass the abstraction of models. The goal of this endeavour is not to discard dialogues as a tool of collaborative planning, but to question the terms under which their transfer from one location to another could occur, and identify aspects that have the potential to optimize the process. Research that has approached dialogues as they unfold in practice has mentioned leadership as having this potential (Millar, Hind, and Magala Citation2012; Martínez Avíla Citation2018). Nonetheless, while being mentioned, the importance of effective leadership for approaching challenges such as cultural difference, power discrepancy and agency has not been explored in greater length (Lazoroska and Palm Citation2019). Thus, this article aims to fill these two interconnected research gaps. Through an empirical examination of the collaborative practices between municipal representatives and building actors, the contribution of this research is to provide increased understanding of dialogues as tools of collaborative planning, and what facilitates or hinders such processes.

Following Reimer’s (Citation2013) argument that planning has taken an all too unproblematic turn towards new rationales, such as collaborative planning, we will outline the limitations of the collaborative in the dialogue processes we describe. A part of the critique towards collaborative planning is that it only involves a minority of the population, as the tools used by planners are designed for small groups (Proli Citation2019; Allmendinger and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2002). While this is a limitation of collaborative planning in general, it is likewise a limitation of this study, as the actors engaged in the dialogue were not diverse. The collaborative planning process can be understood as an invitation for the levelling of hierarchies between the planners and stakeholders. In the cases we describe, however, stakeholders are property owners and property developers. According to Reimer (Citation2013), planning needs to deal with the ever-rising power of economic actors and their interests and strategies. In relative terms, these actors already have a substantial amount of economic power at their disposal. Knowledge is constructed by power relationships between groups. The group with power influences how knowledge is communicated, how it is understood and the language on which it is based (Proli Citation2019). This implies that the power wielded by these actors has been reinforced. Including these actors was, however, the modus operandi of the dialogues. A key concept in collaborative planning is strategy (Healey Citation1997; Harris Citation2002). Our cases, although limited examples of collaborative planning, are products of strategic inclusion of actors that have been hard to mobilize.

In line with these challenges and the approaches for addressing them, this paper examines the implementation of dialogue processes with property owners and property developers in Malmö through two case studies. The aim is to analyse the interconnections between dialogue models and the local context, asking how these connections affect the transferability of models and how the role of process leadership affects exchanges between actors when high stakes and complex power structures are involved.

2. Theory: dialogue as a situated practice

This article approaches dialogue models as ways to induce sustainability transitions among property owners and property developers. Given the nature of the qualitative data we gathered, we do not examine outcomes in terms of sustainability. We postulate that dialogues merit study as they can help mobilize and invoke collective action to advance sustainable development in the building sector. From a general perspective, dialogue has been described as a community of inquiry (Innes and Booher Citation2010). We define dialogue as the process by which actors engage with one another in a respectful and trusting manner to exchange knowledge and experience in the interest of producing sustainable urban transitions (Lazoroska and Palm Citation2019). The stakeholders engaged in dialogue strive to negotiate their positions and perspectives to create shared meaning and innovative means of action (Lazoroska and Palm Citation2019). Indeed, as we will show, this definition captures the ideal towards which practitioners worked towards, but it did not always tally with the daily experiences of collaboration.

To study the dialogue processes as they played out in our case studies, and to see what was situated and contextual about the cases, we applied a practice-based framework. Practice-based research postulates that the subjects and objects of knowledge are co-constituted, and that research including human subjects benefits from studying the context and social relationships in which those subjects are active (Gherardi Citation2008; Nardi Citation1996). Nonetheless, contemporary urban planning is a complex process, involving many different stakeholders. Thus, we argue that issues such as trust, learning and leadership need to be accounted for in order for that complexity to be accommodated. We now go on to address the theoretical foundations of these concepts as they are used in our research.

Trust is important because when it flows among the participants, the outcomes of the process will be relevant to the values of those involved, and there is potential for those relationships to endure over time (Gherardi Citation2008). Trust, as well as reflection and learning, are processual outcomes, constituted reciprocally in the interaction between subjects and objects (Gherardi Citation2008). When stakeholders come from different communities, attention is required to the communicative practices through which trust and understanding develop (Healey Citation1997). Trust can be created and fostered by utilitarian calculations and predictability, personal relations and feelings, institutions and knowledge about norms, or abstract qualities of an “external object” (Talvitie Citation2012), or as we will go on to show, by a combination of some of these conditions.

Learning and knowing are understood as dynamic activities that take place in situated contexts and practices (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013). Knowledge is embedded in the process, methods and tools of a practice, as well as the people that perform it (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013). Transferability of models is tied into matters of knowledge and learning, as it is essentially about drawing lessons or policy transfer from other cities. The concept of transferability is based on the idea that new lessons are necessary when routines stop providing solutions (Rose Citation1991; Baumann and White Citation2011). Researchers who have dealt with transferability have postulated that responses from one place can, to a certain extent, be transferred to others (Rose Citation1991; Baumann and White Citation2011). In this research, we take a slightly sceptical approach, and examine aspects of dialogues that are not as easily transferable, and the lessons to be learned from those difficulties.

Another aspect of dialogues that will be examined in this research is leadership. Leadership is here understood as the process through which resources are mobilized and power is shared between stakeholders with collaboration goals (Fahmi et al. Citation2016). Indeed, in the studies on collaborative planning, leadership and mediation have been examined for their role in catalysing the nature and quality of the exchanges between stakeholders (Ansell and Gash Citation2007; Baumann and White Citation2015; Martínez Avíla Citation2018; Millar, Hind, and Magala Citation2012). When all parties engage in exchange with each other, it can increase network power (Booher and Innes Citation2002). Successful leadership is expected to encourage participation and overcome conflicts between stakeholders, and transform these into practical working relationships (Crosby and Bryson Citation2005). Leaders are likewise central to trust and critical to successful planning (Talvitie Citation2012). Dialogues have been criticized for their roots in Habermas’ work on communicative rationality and its reliance on ideal-type communicative situations, which would make them difficult to apply to real-life situations. But, as leadership has the potential to address power discrepancies, difference and agency, it could hold the key to optimizing dialogue processes (Fahmi et al. Citation2016). Leadership theories have differing perspectives on what makes a good leader. There are perspectives that highlight personal traits (Bolden et al. Citation2003), those that require a leader to adapt to specific environments (Fahmi et al. Citation2016), and those that accentuate the role of leaders in constructing common vision (Rondinelli and Heffron Citation2009). While these different leaders base their powers on different sources, be it their personality, their adaptability, or their capacity to bring people together, they all require a skill set. According to Martínez Avíla (Citation2018), dialogue leaders need to accrue and develop social skills, most relevantly those of facilitation and engagement to optimally engage with the dialogue actors and the local environment. How to manage leading a dialogue, while making the most of one’s personality, adaptability, sociability or skills, will be further analysed.

3. Methods

This article is the product of practice-based research, which has implications for the methodology applied. This approach affects the duration of the research, draws attention to broad patterns of activity rather than episodic fragments, and requires varied data collection techniques as well as commitment to understanding participants’ viewpoints (Nardi Citation1996). Qualitative methods were accordingly used to gather research data. The primary methods were semi-structured interviews and participant observation during events, workshops, seminars, and planning meetings with the actors studied. Two researchers gathered the data in two areas of Malmö, Sweden, one working in Sege Park and the other in Sofielund. The researcher in Sege Park participated in 20 data-gathering interactions, while the researcher in Sofielund participated in five. Field notes were written on these interactions. These qualitative data were complemented with desktop research, including grey literature research, gathering and analysing documents produced by the City of Malmö, property owners, and property developers concerning their sustainability efforts. We also followed developments on these actors’ websites.

Fifteen interviews were conducted in Sege Park and ten in Sofielund. We promised our interviewees anonymity, so the quotations do not use their names or specify their roles. The interviews lasted between one and two hours and were audio recorded with interviewee consent. The Sege Park interviewees were selected based on their roles as property developers or process leaders in the ongoing development project; those in Sofielund were chosen from the list of property owners engaged in the association that is the focus of study, and from the municipal civil servants they identified as their contacts. In Sege Park, all 13 property developers were interviewed, as well as two municipal civil servants. In Sofielund, six property developers were interviewed, as well as one chairperson, one municipal civil servant, one development leader, and one consultant.

The interviewees were asked to begin by introducing their professional background and current professional role, before the interview continued by addressing the interview themes. The first theme was the concept of dialogue: how familiar the interviewees were with it, and how it was, or was not, related to the work processes in Sege Park or Sofielund. The second theme concerned the interviewees’ practical experiences with dialogue processes to promote sustainability, the extent of their involvement in such processes in the two areas, and descriptions of how these processes played out. The final theme dealt with their perceptions of the interactions between property owning/developing actors and municipal actors, as well as their recommendations for improving the dialogue process (the interview guide is found in Appendix 1 (online supplemental data)).

The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs Citation2008). The researchers transcribed the interviews, focusing on the three themes discussed. Concurrently with the data gathering, the researchers reviewed the literature so that the literature and empirical findings could inform each other. The content analysis can be understood as deductive, as the interview content was reviewed for correspondence with the literature review findings. The interviews were coded manually by the researchers, focusing on identifying common patterns in the interviewees’ responses. Commonalities were sought in keywords and phrases, and in how the subjects positioned themselves relative to the topics. These commonalities were then related to the supplementary data the researchers had gathered through desktop research. The researchers met regularly to discuss the commonalities and differences identified in their interpretations of the data. The quotes present in the article have been selected as they aptly summarized what we had been learned with multiple research participants and across a variety of occasions.

4. The case studies: Sege Park and Sofielund

The research presented here examines two projects in Malmö: a development project in the Sege Park district and a business investment district (BID) in Sofielund. We selected these case studies as they both implemented the dialogue model, albeit as we will show, in rather different ways.

Sege Park is the area of a former psychiatric hospital that was closed in 1995. The goal is to develop this area as a mix of new and old housing, business premises, public services, and parks. According to the plans, by 2025, there will be up to 900 dwellings in Sege Park. The development process is characterized by a sustainable approach with a specific focus on creating a low-carbon district. According to the project website, Sege Park is to be a frontrunner in sustainable urban development and a test bed for sustainable solutions and sharing services such as carpooling, non-grid-tied street lighting, and integrated recycling. To achieve these ambitious goals, Malmö initiated a building developer dialogue in 2017.

Unlike in Sege Park, the dialogues in Sofielund were not initiated as a series, but played out within the frame of the BID model employed by Fastighetsägare Sofielund (Property Owners Sofielund), an association started in 2014 as an initiative of the City of Malmö and Fastighetsägarna Syd (Property Owners South). BID stands for business investment district, meaning that local businesses pay a fee to fund projects in the area. The association drew its inspiration for the BID model from North American and other international models, where such forms of collaboration are formalized and regulated through legislation. This is not yet the case in Sweden, where participants engage voluntarily. The area Sofielund is a housing and industrial area with approximately 12,000 residents in 5,000 housing units, as well as 400 registered businesses and 150 local associations. In its public presentation, the association framed the participation of the residents and the City of Malmö as essential in developing Sofielund as an attractive part of the city. To further realize their vision of integration and participation, the association is open to all those who own properties in the area (both apartment buildings and commercial premises) as well as local residents’ associations, companies, and businesses. At the time of writing, the association had about 50 members. Currently, the primary goals are to reduce criminal activity in the area, increase residents’ sense of safety, and brand the area as an attractive place to live in Malmö. The association has grown to be perceived as a successful framework for stimulating developments in Sofielund that are beyond the authority of the municipal government.

We will now go on to discuss the dialogue models in use in the two areas, followed by the main method that they have in common (workshops), and end with discussing the role of leadership in the two dialogues.

4.1. The interconnections between dialogue models and the local context

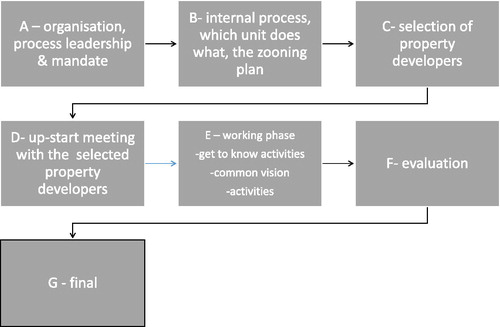

The Sege Park dialogue model is based on a general model described in a City of Malmö brochure from 2014. The model is presented from the perspective of the city, and is intended to be used by municipal officials in future dialogues with property developers. The dialogue process is divided into seven “elements”, A–G. Elements A–C concern internal processes in the municipal administration. Elements D–G refer to meetings between the city and property developers. These elements are shown in .

The elements constituting the model are described in detail in the brochure. The brochure gives a relatively clear introduction to how to conduct a dialogue, giving practical tips and advice on how to proceed and what to consider in every step. This brochure was not, however, used by those running the Sege Park dialogue: they were aware of its existence, but it had no function in the process. The process leader said that, although she had been involved in producing the brochure, she did not use it. During the observations the researchers did note that the model’s different steps were followed. According to the process leader, the dialogue played out based on experience, rather than by following a brochure. The process leader had conducted dialogue meetings since the city of Malmö started to use them and knew the process by heart. In Sege Park the dialogue meetings were thus conducted in accordance with the model outlined in the brochure, but the reason for that was not the existence of the document, but the existence of an experienced leader.

In Sofielund, the BID model was in use. A BID is typically formed and governed by associations of property and business owners within a territorial area of a city and they are authorized by the local government (Grossman Citation2010). Justice and Goldsmith (Citation2006) view BIDs as instruments that accomplish broad public policy goals, such as promoting the general welfare or facilitating the joint provision and production of local public goods. The association has been actively, and quite successfully, attempting to rebrand itself in a Swedish guise. BID thus signifies Boende, Integration, och Delaktighet, (in English: Housing, Integration, and Participation). The emphasis on social sustainability is the reason that the acronym BID has been changed to better resonate with the model in Sofielund. Funds from the City of Malmö cover administrative expenses and the development leader’s salary. The development leader is employed by the traffic department, but has BID Sofielund and its office in Sofielund as his headquarters.

Unlike in the Sege Park case, the term “dialogue” is not being specifically and explicitly used by the actors in Sofielund. The interaction between the City and BID Sofielund was described as “contact surfaces” or as a “partnership”. The BID Sofielund board had a reference group with representatives from the City of Malmö (from the City’s traffic department, environmental management department, city planning office, and city planning office unit for safety and security), police, emergency services, and VA Syd. The property owners involved in the association emphasized the importance of this group for the increased contact and communication established among themselves and with the City of Malmö. This has helped the property owners to better understand city building processes.

The dialogues in Sege Park have been perceived as a success within the city of Malmö and have served as a model for horizontal diffusion across development projects in Malmö. BID Sofielund is perceived as successful by other municipalities as well, and there is interest in replicating it. The development leader stated in interview that the project is often visited by those who wish to start a similar process in another area.

4.2. Workshops as the main platforms for dialogues

Regardless of their differences in the models used in Sege Park and Sofielund, the practical execution of the dialogues was similar. Multiple workshops, planned by the City of Malmö, have targeted BID Sofielund. Sege Park had one monthly dialogue meeting. Each meeting treated a specific theme, such as energy, the stormwater system, mobility, or waste disposal. As we observed during our field visits, the meetings started with presentations by invited speakers knowledgeable about the themes, followed by workshops in which the themes were discussed by all participants. The workshops in Sege Park and Sofielund were the base for the dialogues and had similar organisations. We witnessed that the process leader together with the invited speakers would set the agenda and organize the activities for the day. Commonly, the participants were divided into smaller groups. These smaller groups were expected to work through the topics in an explorative manner, and discuss with each other based on their particular experiences. That lasted around half an hour. The smaller groups were ‘supervised’ by the process leader and speakers, functioning as moderators. These most often culminated in a plenary discussion, wherein one member of each group would summarize the discussions in the smaller group. Key words and diagrams were written down on larger writing surfaces, making them visible for all those present. They were often photographed by those who held the meetings. In the end, the invited speaker and/or the process leader summarized the discussions.

Among the participating property owners and property developers in Sege Park and Sofielund the workshops were not always seen as an effective approach. In Sofielund the property owners perceived them as too numerous, and the property owners did not find them useful. They were – as one put it – “tired of workshops”. The process leader stated that the workshops the city requested were time consuming and a barrier for his work. When the process leader organised meetings with the local businesses, he tried to make them quick and effective: an hour in duration with a clear agenda and reaching clear resolutions. According to the property owners, “making something out of dialogues” is most important, and not merely “sitting there, being invited to meetings where people just sit and talk and workshop”. Indeed, during one BID Sofielund meeting, as we observed, the participants went through the entire three-page agenda in under 20 min. What is relevant to these practitioners is functional and effective relationships that play out at the local level (in Sofielund) within a framework of meetings with clear agendas and outcomes, rather than explorative workshops with open-ended questions and a process orientation.

When interviewed, the property developers in Sege Park said that many relevant themes were discussed at the dialogue meetings, and they felt that they learned a lot from them. A recurring criticism expressed by the property owners was that the information provided was too general and that the meetings never ended in decisions about action, but rather resolved to return to or investigate the issue further. One property developer related this to difficulties occurring when different professional cultures come together:

I think the meetings could be run more efficiently. It is like two different worlds that meet. There is a big difference from our world, where we run projects in a totally different way. But, at the same time, it is difficult to coordinate 13 different property developers with such diverse characteristics.

The workshops in Sege Park were, however, generally seen in a positive light. The property developers wanted to have time to discuss matters with one another. The problem was that the workshops did not always have contents reflecting what the property developers wanted to discuss. When the issues were not directly linked to the property developers’ interests at the moment, they tended to be perceived as a waste of time.

Another criticism was that the property developers’ particular knowledge was not put to good use during the meetings. The involved property developers usually had special areas of expertise, such as wood construction, or had a development model targeting low-income families. They could have brought their knowledge to the discussions, but usually outside experts were invited as speakers. In general, the interviewees wanted to learn more from the involved property developers’ experience and to present the lessons they had learned in other projects.

4.3. The role of process leadership

All involved actors saw the networks that the dialogues in Sege Park and Sofielund established as something positive. In Sege Park, especially the smaller property developers appreciated the networks:

For us the most important is to embrace all the knowledge that is in the room. We have got really good contacts through Sege Park.

According to a participant from BID Sofielund, they have the potential to foster exchange between groups:

The access points to the city [administration] are very valuable for the entire business community that is involved. At the same time, I have great support from the business community, which is a bit of a lobbying organization that will give me leverage when I go to the city, because they do not counteract each other, they synergize somehow, which works very well.

To carry out the types of collaboration described, the essential ingredient identified in the interviews from both areas has been trust, which is built over time and through experience. This is expressed in the following way by an informant engaged in BID Sofielund,

The most important thing of all has been creating trust – to really trust one another.

By establishing and maintaining networks, these actors have been able to strategically position themselves and reach groups that would otherwise be difficult to access. According to interviewees in both areas, the process leaders are important to create well-functioning relationships and trust. Both process leaders had substantial experience of working in dialogue processes with property developers and property owners from their earlier work.

While both process leaders were important, the one in Sofielund was perceived as essential for the networks there. His role in the success and visibility of the project was unquestionable: he acted as a representative of BID Sofielund at various events, successfully maintained communication between the City and the association, and was responsible for authoring grant applications. He has, in several reports, been described as a bridge to the City of Malmö administration for the property owners, and as facilitating links between local residents, police, and other actors who want to be involved in the area (Fryklund Citation2018; Port Citation2018).

The problematic aspects of this dependence appear in attempts to objectively describe and institutionalize successful processes, as they are linked to the subjective qualities of the central people involved and the networks they have created. One representative of the City of Malmö was eager to point this difficulty out:

It’s something we’ve created through experience … But it’s not that we have created words, or say … “Yes, now we are using this ‘chip method’”, or whatever it is. It does not exist. And this is both good and bad, because what is good about it is that we have found something that works, but it is clear that it is not so transparent, because … [one person] has driven it.

This has also been a general point of concern. To prevent the Sofielund process from becoming too dependent on one person, two associates were hired in autumn 2018 “to be his [i.e. the development leader’s] right and left hands”. In Sege Park, the process leader said that knowledge and experience were shared between staff in face-to-face interactions and by having more junior staff work with senior staff. A year into the process in Sege Park, through our field visits, we could observe that the more experienced process leader was the formal leader of the process, taking a clear leadership role during the meetings. Every second dialogue meeting, however, a junior process leader led the meeting, mimicking the senior one’s leadership style. The senior process leader intervened if and when needed to provide backstopping support. Learning thus occurred through practice.

5. Discussion

The Sofielund and Sege Park cases both represent dialogue processes, but they played out differently. In this discussion, we focus on the aspects shared by the two cases and what can be learned from both models in relation to what dialogues can enable or restrict, their potential for transfer, and the need for process leaders situated in the local setting.

5.1. Dialogues as models creating common spaces for building networks, trust, and mutual learning

Contemporary urban development calls for a redefinition of spatial responsibilities, as well as for new strategic alliances that go beyond boundaries between spheres and sectors (Reimer Citation2013). The collaborative process as it played out in Malmö called for the inclusion of building actors who wielded a great amount of power due to the energy saving potential of buildings. Although these dialogues are a relatively limited example of what collaborative planning towards sustainability transformations can be, they were a strategic effort to include actors from an inertial sector, in terms of their efforts to achieve sustainability goals. Ensuring a sustainable future depends on strategic actions of public and private actors alike, and their capacity for considering the ecological limits of the planet and those of resources (Linnenluecke et al. Citation2017).

The starting conditions of the dialogue process were discrepancies in the particular types of expertise that the property owners, property developers, and City of Malmö representatives brought with them, as well as the weight of their preconceived notions of one another. The dialogues enabled collaboration and mutual learning between and within sectors, involving actors who would not otherwise have worked together or shared values. This confirmed the point of Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen (Citation2013) that boundary-crossing activities are becoming increasingly important in interdisciplinary and fragmented industries such as construction in order to access information from outside the group. The dialogue meetings and longer-term engagement that the process entailed presented an optimal opportunity for exchange across boundaries. The actors involved in these meetings represented distinct fields from which knowledge does not circulate easily. The challenge in such situations is to find ways to make the community boundaries sufficiently permeable for knowledge to be shared (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013). From our observations and as ascertained in the interviews, we gathered that the initial mismatch arising from the different backgrounds of the property owners/developers and the city representatives gave way to knowledge exchange and development. However, this was only possible as actors grew to know and trust each other. The models for creating dialogue in Sege Park and Sofielund proved a fine example of the role governing entities, here, representatives of the City of Malmö, can play in enabling knowledge sharing across boundaries. Swedish municipalities have limited opportunities to set local environmental requirements in their areas, but dialogue processes allow them to contribute to voluntary agreements concerning such requirements.

Ansell and Gash (Citation2007) found that an essential aspect of collaborative processes is building trust among stakeholders, which can be both difficult and time consuming. Likewise, trust building is contingent on the work of “good collaborative leaders” who recognize that they must build trust (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013), as illustrated by the involvement of the two leaders involved in the cases: they built the channels through which actors from different sectors met, building networks and trust among themselves. The trust was built on the base of the personal relationships that the process leaders had accrued over time, as well as their institutional knowledge (Talvitie Citation2012). The networks they built are rich in social capital, and can reduce the transaction costs of potential future collective actions (Olsson Citation2009). Thus, they stimulate the potential future collaborations of the participants.

The models applied in the studied cases have their limits. In both dialogue models, the workshop was the mode of engagement chosen to involve all participants when they met. The workshops, however, turned out to be problematic. The municipal representatives were used to organizing, running, and acting through workshops. This experience was less common among the property owners and property developers, who found the workshops a rather time-consuming method that could be replaced by more effective decision-making processes. The city officials emphasized inclusive and deliberative dialogue, while the property owners and developers emphasized effective meetings (i.e. short in duration with clear agendas) and a desire to make decisions quickly. Different approaches to decision-making need to be taken into consideration when arranging dialogues.

The problems arising from having different expectations and ways of doing things were never discussed, and leaving these problems unspoken made them impossible to solve. The workshops symbolized a clash between the meeting of the different professional cultures. The data gathered from the two cases indicated that the problems were not solely about differences in professional language, but also about the different modes and formats of engagement and expectations of outcomes. The workshops were a materialization of the transformation, as well as a critique of the planning profession, paying more attention to dialogue than decisions (Proli Citation2019). Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen (Citation2013) emphasized that interaction between stakeholders in their research was enabled by their willingness to adapt and translate the respective disciplinary discourses. As collaborative endeavours engage multiple stakeholders, the awareness that multiple cultures are brought together needs to be translated into the instruments that are applied, so that they resonate with the participants.

5.2. Transferable models versus particular locations and socio–cultural contexts

There were guidelines for conducting property developer dialogues in Malmö, but they were not used. The process leader in Sege Park criticized these guidelines as too general: they covered all the needed steps, but at such an abstract level that they were useless in practice. The expectations on behalf of the city actors that the guidelines would be used, and their lack of application in the field of action also tallies with Flyvbjerg’s (Citation2006) findings on case studies within the social sciences, and the common misunderstandings that surround them. Flyvbjerg found that general and context-independent knowledge is perceived to be more valuable than concrete, practical and context-dependent knowledge. He contends that it is the type of knowledge which transforms rule-based beginners into virtuoso experts. To apply the guidelines, the practitioners needed past experience of running a dialogue. With such experience, the process leader could contextualize the content and make it valid for the locality; however, if one had such experience, the guidelines were no longer needed.

Through participation in multiple instances of collaboration, relevant skills and knowledge are acquired. These findings resonate with situated action studies, which postulate that activity grows out of responsiveness to the socio–material environment and the capacity for improvisation (Nardi Citation1996; Thollander and Palm Citation2015; Sayer Citation2000). Rule-based knowledge should not be discarded, as Flyvbjerg (Citation2006) contends, as it is essential for building up a base for the training of novices. The knowledge needed to apply the guidelines is nevertheless difficult to codify to be accessible to novices, as it is embedded in actors’ ties to the locality and in their ability to adapt to the processes as they unfold. Crucially, this knowledge was tacit. As the role of the development leader was central, being rooted in his experiences, social network, and personal qualities, we contend that not everything is scalable or transferable. It is unlikely that the BID Sofielund model can be replicated in another area of Malmö without adaptation to the specific area. Understanding the specific challenges, geography, social codes, and relationships of a given area is crucial for success (cf. Fryklund Citation2018).

However, we can see that processes of translation and learning from the general, or global, level did take place in the locality. In Sofielund, the inspiration for the BID was taken from the USA and other international models, but it was necessary to change the foundation and intentions of the concept to make it applicable in Malmö. In Sofielund, the initiative came from municipal actors, rather than from the property owners themselves, as is the case in international versions. While the international examples inspired the collaboration project, it was grounded in the established Swedish practice of starting and running associations based on voluntarism. After starting the association, the process leader managed to develop a version anchored in the neighbourhood and its particular needs. Thus, the mode of organizing BIDs was translated in order to make it operational in the locality.

Are the dialogue processes, as they play out in these two cases, transferable? For these models to be transferred and then applied, they must be reduced to general comprehensive principles. If this is done, then the contextuality and social relationships enabling these models will be greatly reduced. Constituent procedures and steps can be codified on a general level in guidelines, but not the local, situated action, as it emerges from the particularities of given local situations (Nardi Citation1996). It is in the local, situated action that the dialogue is “made”. That property owner and property developer dialogues have been conducted multiple times in Malmö is not attributable to the guidelines, but to the people involved, such as the process leaders. Nonetheless, the alternatives to these generalizable models are not obvious, so these models should not easily be discarded. As proposed in the next section, more attention needs to be paid to the role of process leadership.

5.3. Process leadership

In both cases, the process leaders have been essential for conducting, and optimizing the dialogues (Fahmi et al. Citation2016). Leadership, according to Ansell and Gash (Citation2007), is critical to bringing parties to the table and steering them through the rough patches of a collaborative process. In terms of the social skills identified by Martínez Avíla (Citation2018) as relevant to a leader, during the observations we were not struck by the process leaders’ skills in terms of communicating with participants or facilitating their engagement. Neither of the leaders can be described as dynamic and outgoing, but regardless, they assumed an obvious leadership role. The process leaders in Sege Park and in Sofielund embodied one of the key characteristics mentioned by Martínez Avíla (Citation2018) as important for successful process leadership: they were both familiar with the contexts. They had been employed in the city administration for many years and had earlier worked in close collaboration with property developers and property owners; they were keenly aware of the social, political, cultural, and economic conditions in which the actors involved in the dialogue processes were active. They knew the housing sector well and were familiar with its culture and dominant values and norms. They could speak the languages of the property owners and developers, and of the city administration, functioning as “translators” between the city and the property owners/developers (Gluch, Johansson, and Räisänen Citation2013). They were successful leaders based on their professional experiences.

We gathered that the property developers and owners respected and trusted these process leaders. Because of their knowledge and the trust invested in the relationships, these leaders could promote participation, expand the field of what these actors could influence, manage group dynamics, and extend the scope of the process (Lasker et al. Citation2003). These leaders represent a combination of their capacity to adapt to their professional and local environment (Bolden et al. Citation2003; Fahmi et al. Citation2016), and their investment in constructing a common vision for the stakeholders (Rondinelli and Heffron Citation2009). They also illustrate the transformation of the planning profession; instead of lone problem solving, they acted as mediators for the people involved in the planning situation (Proli Citation2019). A “good leader” in these two case studies is one who is sufficiently familiar with the local context to value and operationalize existing networks and social capital, but who has an awareness of, and capacity to navigate, existing power structures. Through the data gathered during participant observation and in interviews, we conclude that leadership was based on the process leaders’ ability to navigate the existing power structures and on their tacit knowledge of what does and does not work in such networks.

6. Conclusion

The aim with this paper has been to analyze the interconnections between dialogue models and the local context and to examine how these connections affect the transferability of models, and the role leadership has to play.

The research has included two cases of collaborative dialogues in Malmö, engaging property owners, property developers, and municipal actors in sustainability-oriented housing interventions. These represent limited accounts of what collaborative planning could be, as they included a limited number of actors. The relevance of including property owners and developers are, however, related to the power yielded by them and the conservatism of these actors. In earlier research, there has been a lack of studies where dialogue practices are analyzed in real-time and on location, which has been done here. This approach enabled us to study the conflicts that arise, and how these are dealt with.

In the two cases analyzed, the dialogues played out differently. In both cases, though, the dialogues enabled actors who would not necessarily meet to collaborate, strengthen their professional networks, and learn from one another. The general conclusions which can be of importance to reflect upon in future collaborative process are:

Trust, established over time, is essential for effective dialogues to occur.

Frictions arose in our cases from the differences between the professional cultures. Workshops exemplified this: the process leaders saw them as inclusive tools that enhanced communications, the property owners and developers considered them to be time-consuming and inefficient.

The existing written guidelines on how to run a dialogue were not used. Instead, the process leaders trusted their learned ability to act in these for them familiar localities and on their established relationships with the property developers and property owners.

Learning was embedded in the doing, in practice.

Transferability: our findings showed that process leadership bridged the cultural gap between the professional worlds of the Malmö city administration and the property owners and developers. By being familiar with the context, and by translating the discourses from one group to the other the process leaders had a central role in catalyzing the development towards sustainable city districts.

The results indicate the importance of engaging process leaders with access to multiple spheres, who have mastered several professional languages (in this case, those of the building actors, the City of Malmö, and local businesses), and who have personal qualities that enable them to develop trusting long-term relationships.

Another important finding for the future is that actions and behaviors cannot easily be treated as “best practices” that can simply be transferred without adaptation. The sort of leader who works in one context might not work in another. Dialogue processes are better understood when seen as centering on people and the embeddedness of action, rather than as a set of instructions in the form of codified guidelines.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1756758.

Interview_guide.docx

Download MS Word (13.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their many constructive and valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allmendinger, Philip, and Mark Tewdwr-Jones. 2002. Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory. London: Routledge.

- Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash. 2007. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Baumann, Christiane, and Stuart White. 2011. “Pathways Towards Sustainable Urban Transport Development. Investigating the Transferability of Munich Best Practice in Collaborative Stakeholder Dialogue to the Context of Sydney.” Paper Presented at the State of Australian Cities (SOAC) Conference, Melbourne, Australia, November 29-December 1.

- Baumann, Christiane, and Stuart White. 2015. “Collaborative Stakeholder Dialogue: A Catalyst for Better Transport Policy Choices.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 9 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1080/15568318.2012.720357.

- Bolden, Richard, Jonathan Gosling, Antonio Marturano, and Paul Dennison. 2003. A Review of Leadership Theory and Competency Frameworks. Exeter: Centre for Leadership Studies, University of Exeter.

- Booher, D. E., and J. E. Innes. 2002. “Network Power in Collaborative Planning.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 21 (3): 221–236. doi:10.1177/0739456X0202100301.

- Crosby, Barbara C., and John M. Bryson. 2005. Leadership for the Common Good: Tackling Public Problems in a Shared-Power World. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 62 (1): 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- European Commission. 2018. Directive 2018/844/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency. Brussels: European Commission.

- Fahmi, Fikri Zul., Muhamad Ihsani Prawira, Delik Hudalah, and Tommy Firman. 2016. “Leadership and Collaborative Planning: The Case of Surakarta, Indonesia.” Planning Theory 15 (3): 294–315. doi:10.1177/1473095215584655.

- Fenton, Paul, Sara Gustafsson, Jenny Ivner, and Jenny Palm. 2015. “Sustainable Energy and Climate Strategies: Lessons from Planning Processes in Five Municipalities.” Journal of Cleaner Production 98: 213–221. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.08.001.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Fryklund, Julia. 2018. Fastighetsägare BID Sofielund: framgångsfaktorer för samverkan. Malmö: ÅF.

- Gherardi, Silvia. 2008. “Situated Knowledge and Situated Action: What Do Practice-Based Studies Promise.” In The SAGE Handbook of New Approaches in Management and Organization, edited by Barry Daved and Hans Hansen, 516–525. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Gluch, Pernilla, Karin Johansson, and Christine Räisänen. 2013. “Knowledge Sharing and Learning Across Community Boundaries in an Arena for Energy Efficient Buildings.” Journal of Cleaner Production 48: 232–240. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.10.020.

- Government Bill. 2005/06. Nationellt program för energieffektivisering och energismart byggande. Stockholm: Riksdagen.

- Granberg, Mikael, and Ingemar Elander. 2007. “Local Governance and Climate Change: Reflections on the Swedish Experience.” Local Environment 12 (5): 537–548. doi:10.1080/13549830701656911.

- Grossman, Seth A. 2010. “Reconceptualizing the Public Management and Performance of Business Improvement Districts.” Public Performance & Management Review 33 (3): 361–394. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576330304.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 1 Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Harris, Neil. 2002. “Collaborative Planning.” In Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory, edited by Philip Allmendinger and Mark Tewdwr-Jones, 21–43. London: Routledge.

- Healey, Patsy. 1997. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. Hongkong: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Innes, Judith E., and David E. Booher. 2003. The Impact of Collaborative Planning on Governance Capacity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Innes, Judith Eleanor, and David E. Booher. 2010. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. London: Routledge.

- Jensen, Per, and Esmir Maslesa. 2015. “Value Based Building Renovation: A Tool for Decision-Making and Evaluation.” Building and Environment 92: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.04.008.

- Justice, Jonathan B., and Robert S. Goldsmith. 2006. “Private Governments or Public Policy Tools? The Law and Public Policy of New Jersey’s Special Improvement Districts.” International Journal of Public Administration 29 (1–3): 107–136. doi:10.1080/01900690500409005.

- Kivimaa, Paula, and Mari Martiskainen. 2018. “Innovation, Low Energy Buildings and Intermediaries in Europe: Systematic Case Study Review.” Energy Efficiency 11 (1): 31–51. doi: . doi:10.1007/s12053-017-9547-y.

- Kivimaa, Paula, Hanna-Liisa Kangas, David Lazarevic, Jani Lukkarinen, Maria Åkerman, Minna Halonen, and Mika Nieminen. 2019. Transition Towards Zero Energy Buildings: Insights on Emerging Business Ecosystems, New Business Models and Energy Efficiency Policy in Finland. Helsingfors: SYKE Publications.

- Lasker, R. D., E. S. Weiss, Q. E. Baker, A. K. Collier, B. A. Israel, A. Plough, and C. Bruner. 2003. “Broadening Participation in Community Problem Solving: A Multidisciplinary Model to Support Collaborative Practice and Research.” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 80 (1): 14–60. doi:10.1093/jurban/jtg014.

- Lazoroska, Daniela, and Jenny Palm. 2019. “Dialogue with Property Owners and Property Developers as a Tool for Sustainable Transformation: A Literature Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 233: 328–339. doi: . doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.040.

- Linnenluecke, M. K., M. L. Verreynne, M. J. de Villiers Scheepers, and C. Venter. 2017. “A Review of Collaborative Planning Approaches for Transformative Change Towards a Sustainable Future.” Journal of Cleaner Production 142: 3212–3224. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.148.

- Malmö stad. 2018. Arkitekturstaden Malmö: Tillägg till översiktsplan för Malmö. Malmö: Malmö stad.

- Martínez Avíla, Carlos. 2018. Stakeholder Participation in Property Development. Lund: Faculty of Engineering, Department of Building and Environmental Technology, Division of Construction Management.

- Millar, Carla, Patricia Hind, and Slawek Magala. 2012. “Sustainability and the Need for Change: Organisational Change and Transformational Vision.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 25 (4): 489–500. doi:10.1108/09534811211239272.

- Nardi, Bonnie A. 1996. “Studying Context: A Comparison of Activity Theory, Situated Action Models, and Distributed Cognition.” In Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human–Computer Interaction, edited by B. A. Nardi, 69–102. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Olsson, Amy Rader. 2009. “Relational Rewards and Communicative Planning: Understanding Actor Motivation.” Planning Theory 8 (3): 263–281. doi:10.1177/1473095209104826.

- Palm, Jenny, and Katharina Reindl. 2018. “Understanding Barriers to Energy-Efficiency Renovations of Multifamily Dwellings.” Energy Efficiency 11 (1): 53–65. doi: . doi:10.1007/s12053-017-9549-9.

- Port, Michael. 2018. “BIDding on Cities: Applying the Business Improvement District Model for Urban Sustainability.” IIIEE Master Thesis, Lund University.

- Proli, Stefania. 2019. “Communicative Turn in Spatial Planning and Strategy.” In Sustainable Cities and Communities, edited by Walter Leal Filho, Ulisses Azeiteiro, Anabela Marisa Azul, Luciana Brandli, Pinar Gökcin Özuyar, and Tony Wall, 1–10. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Reimer, Mario. 2013. “Planning Cultures in Transition: Sustainability Management and Institutional Change in Spatial Planning.” Sustainability 5 (11): 4653–4673. doi:10.3390/su5114653.

- Rondinelli, Dennis A., and John M. Heffron. 2009. “Leadership for Development: An Introduction.” In Leadership for Development: What Globalization Demands of Leaders Fighting for Change, edited by Dennis A Rondinelli and John M. Heffron, 1–24. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

- Rose, Richard. 1991. “What is Lesson-Drawing?” Journal of Public Policy 11 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00004918.

- Rydin, Yvonne. 2014. “Communities, Networks and Social Capital.” In Community Action and Planning: Contexts, Drivers and Outcomes, edited by N. Gallent and D. Ciaffi, 21–39. Bristol: University Press.

- Sayer, R. Andrew. 2000. Realism and Social Science. London: SAGE.

- Talvitie, Antti. 2012. “The Problem of Trust in Planning.” Planning Theory 11 (3): 257–278. doi:10.1177/1473095211430494.

- Thollander, Patrik, and Jenny Palm. 2015. “Industrial Energy Management Decision Making for Improved Energy Efficiency: Strategic System Perspectives and Situated Action in Combination.” Energies 8 (6): 5694–5703. doi:10.3390/en8065694.