?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

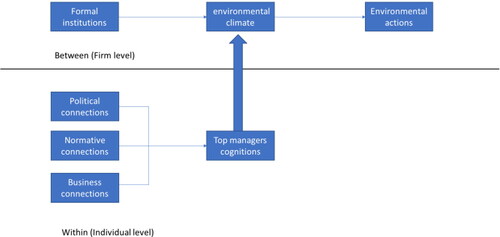

We developed an overarching multi-level mediation model using 199 responses from 53 companies from the industrial sector in Jordan to examine (1) the mediation effect of firm-level environmental climate on the relationship between formal regulatory institutions and firm-level strategic environmental actions, and (2) the role that informal institutions conveyed via political, normative, and business connections plays on the environment-related cognitions of top managers. At the ‘within’ level, our results indicate that top managers with strong political connections develop negative environment-related cognitions while those with strong normative and business connections develop positive environment-related cognitions. At the firm-level, our results reveal that firm-level environmental climate – as an aggregated measure of the ‘within’ level environmental cognitions of top managers – fully mediates the relationship between formal regulatory institutions and firm-level strategic environmental actions. This study demonstrates how multilevel research is used to enrich understanding of firm-level strategic environmental actions, with implications beyond Jordan.

1. Introduction

‘What drives firm-level strategic environmental actions’ has occupied a significant place in the strategic management literature (Chatterji and Toffel Citation2010; Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Kassinis and Vafeas Citation2006; Wang, Li, and Zhao Citation2018). Although several explanations have been developed (Alt, Díez-de-Castro, and Lloréns-Montes Citation2015; Menguc, Auh, and Ozanne Citation2010; Shu et al. Citation2016; Walker, Berry, and Avellaneda Citation2015), two institutional themes have been particularly dominant - formal institutions and informal institutions (cf: Baumol Citation1990; Denzau and North Citation1994; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983; Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; North Citation1990, Citation1997, Citation2005).

Formal institutions represent the legislative rules, regulatory requirements, and policy-related frameworks that guide actions (Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Li Citation2010; Dheer Citation2017; Hörisch, Kollat, and Brieger Citation2017; McMullen, Bagby, and Palich Citation2008; North Citation2005; Scott Citation2008), institutionalize structures (Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Sarkis, González-Torre, and Adenso-Díaz Citation2010; Zhu and Geng Citation2013), shape strategies and influence performance (Bansal and Clelland Citation2004; Hoffman and Jennings Citation2015; Schaefer Citation2007). The central notion is that well-regulated (North Citation1990), well-designed (Porter and Van der Linde Citation1995), and well-powered (Clemens and Cook Citation1999; Scott, Brinton, and Nee Citation1999) formal regulatory institutions determine which firm-level strategic environmental actions, such as reducing use, reusing, recycling, preventing pollution, initiating programs and policies, are best (Oliver Citation1991) and isomorphic (Deephouse Citation1996) for firms’ legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983; Suchman Citation1995) and survival (Zucker Citation1987).

Political, normative, and business connections, as informal institutions (Baumol Citation1990; Denzau and North Citation1994; North Citation1990), are instituted through implicit, unwritten, non-legally binding, culturally-transmitted, and socially-constructed, customs, values, and codes of conduct (Hörisch, Kollat, and Brieger Citation2017; North Citation1990; Sartor and Beamish Citation2014; Sauerwald and Peng Citation2013; Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015) “that have never been consciously designed but are still in everyone’s interest to keep” (Sugden Citation1986, 54). The central idea is that “in many countries, the lack of transparency in rules, laws, and processes creates a fertile ground for corruption” (Tanzi Citation1998, 575), and allows well-connected firms to bypass ineffective, poorly devised (Baumol Citation1990), and underdeveloped (Markóczy et al. Citation2013; Peng Citation2003; Puffer, McCarthy, and Boisot Citation2010) formal regulatory institutions. Indeed, taking this argument further, firms’ political, normative, and business connections may not only influence which formal regulatory requirements are prioritized, complied with, or flouted (Doh et al. Citation2003) at the firm level, but also control those very formal regulatory institutions that are supposed to constrain them (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2010; Gómez-Haro, Aragón-Correa, and Cordón-Pozo Citation2011; Greenwood, Rosenbeck, and Scott Citation2012; Oliver Citation1991; Sutter et al. Citation2013), and thus could trigger substantively different firm-level strategic environmental actions to those expected under formal regulatory institutions (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004).

Both themes, that of formal regulatory institutions and informal institutions of political, normative, and business connections, have progressed along two independent paths; the former emphasizes the trickle-down effect of formal regulatory institutions’ legitimization power (Scott Citation1987; Zucker Citation1987) on firm-level strategic environmental actions; the latter emphasizes the effect of personal connections and individuals’ social networks (Lin Citation2001) on firm-level strategic environmental actions. While it is true that the legitimization power of formal regulatory institutions forces firms to “accept a reality that they might not have enacted on their own” (Johnson and Hoopes Citation2003, 1057), political, normative, and business connections do exist independently of formal regulatory institutions and unintentionally, they may allow well-connected top managers to operate behind, between, or within the legally binding formal regulatory requirements (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004; North Citation1990; Voigt and Kiwit Citation1995). This suggests that formal regulatory institutions and informal institutions of political, normative, and business connections may not only exist but they may explain firm-level strategic environmental actions better than either one can on its own. We contend, therefore, that a disconnect between formal regulatory institutions and informal institutions of political, normative, and business connections has created artificial boundaries between the two themes and severely inhibits the development of a comprehensive and integrated institutional theory of firm-level strategic environmental actions.

Furthermore, although there is considerable agreement concerning the importance of formal regulatory institutions and informal institutions of political, normative and business connections as central variables for understanding firm-level strategic environmental actions, there is very little agreement about how they should be empirically modeled and theoretically integrated. Indeed, after reviewing numerous papers published on corporate social responsibility (CSR) in top-tier management journals, Aguinis and Glavas (Citation2012) found that 95% focused on a single level of analysis, 93% on predictors, outcomes, and moderators, and only 7% explored the underlying mechanisms linking predictors and outcomes. They concluded that multilevel research and mediation effects are a serious knowledge gap that can be well observed in the environmental management literature. It is our intention to address this deficiency in the theoretical literature.

Drawing on formal institutions, informal institutions (Baumol Citation1990; Denzau and North Citation1994; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983; North Citation1990, 1997, Citation2005; Scott, Brinton, and Nee Citation1999), and firm-level strategic environmental actions (Chatterji and Toffel Citation2010; Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Oliver Citation1991; Wang, Li, and Zhao Citation2018), we propose two contextual variables – environment-related cognitions of top managers (Gröschl, Gabaldón, and Hahn Citation2019; Laamanen and Wallin Citation2009; Samba, Van Knippenberg, and Miller Citation2018) and organizational climate (Bolinger, Klotz, and Leavitt Citation2018; Bruton, Ahlstrom, and Yeh Citation2004; Glick Citation1985) – to develop a multi-level mediation model of firm-level strategic environmental actions. More specifically, at the ‘within’ level, we propose that political, normative, and business connections are very important determinants of the environment-related cognitions of top managers. At the firm level, we describe how firm-level environmental climate, which is a representation of the environment-related cognitions of top managers aggregated to the firm level, mediates the relationship between formal regulatory institutions and firm-level strategic environmental actions.

According to social cognition theory (Fiske and Taylor Citation1984), cognitions are centered around individuals – as ‘information workers’ (McCall and Kaplan Citation1985, 14) – processing, absorbing, and disseminating information cues from their frames of reference (Kaplan Citation2011; Rouleau Citation2005; Walsh Citation1995). They are also defined as “a forward-looking form of intelligence that is premised on an actor’s beliefs about the linkage between the choice of actions and the subsequent impact of those actions on outcomes” (Gavetti and Levinthal Citation2000, 113). How political, normative and business connections relate to the environmental cognitions of top managers has not been thoroughly researched in developed and emerging economies alike. This research gap is particularly problematic in emerging economies, where “who you know is more important than what you know” (Yeung and Tung Citation1996, 54). We address this gap in the literature by providing empirical evidence of the significant role political, normative, and business connections play in determining the environment-related cognitions of top managers. As discussed, we argue that close interactions (Douglas Citation1986) and communications (Donnellon, Gray, and Bougon Citation1986) with government bureaucrats, normative bodies, and supply chain partners assign privileges and permissions to well-connected top managers that contribute to shifting their cognitions regarding the environment (Marquis and Lounsbury Citation2007; Thornton and Ocasio Citation2008).

We define environmental climate as a firm-level environmental DNA which represents what is core, enduring, and distinctive about the environment-related cognitions of its top managers. It is important to clarify, however, that ‘organizations don't think’ (Sims and Gioia Citation1986) and ‘don't cognize’ (Glick Citation1988; James, Joyce, and Slocum Citation1988), only people do. But in the combined cognition, firms may experience “potentially as many climates as there are people in the organization” (Johannesson Citation1971, 30). It is, thus, of paramount importance for firms to establish cognitive consensus (Dutton, Fahey, and Narayanan Citation1983; Ehrhart, Schneider, and Macey Citation2013, Schneider Citation1990) – ‘shared stereotypes’ (Janis Citation1972) or ‘metaphors’ (Sapienza Citation1985) – to guide firm-level strategic environmental actions. Empirically, cognitive consensus is established through the aggregation of the environment-related cognitions of top managers’ scores, and the aggregated variable is then used to represent the environmental climate construct at the firm level.

This implies that the ‘within level’ of analysis would allow top managers to very much vary in their environment-related cognitions. At the firm-level, however, such variation can only be limited because the aggregated measure of environment-related cognitions of top managers only reflects the substantial common variance among top managers’ environment-related cognitions. This theoretical modeling is based on the assumption that “climate is a perception that resides within an individual, and only when perceptions are shared can there be a higher-level climate” (Jones and James Citation1979, as cited in Schneider et al. Citation2017, 471). It also echoes Glick’s (Citation1985, 607) argument that firm-level environmental climate should be thought of and measured “at the organizational level of analysis”. Put differently, firm-level environmental climate is a convergent measure of environment-related cognitions of top managers aggregated to the firm-level of analysis.

Firm-level strategic environmental actions could range from (i) being symbolically reactive, involving ceremonial practices that make firms appear as if they are committed, but without necessarily enacting meaningful changes to the actual practices, processes, and actions on the ground to (ii) being substantively involved in often meaningful, voluntary actions that go beyond formal regulatory requirements to preempt and prevent environmental impacts (Carballo-Penela and Castromán-Diz Citation2015; Garcés-Ayerbe, Rivera‐Torres, and Murillo‐Luna Citation2012; Rodrigue, Magnan, and Cho Citation2013; Sarkis, González-Torre, and Adenso-Díaz Citation2010; Wolf Citation2013).

2. Study context

Much of the available literature on firm-level strategic environmental actions has been mainly focused on developed countries where formal regulatory institutions are concrete, clearly articulated, measurable, and determinant, with informal institutions producing substantively similar firm-level strategic environmental actions to that expected under formal regulatory institutions (Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004; Lauth Citation2000; March and Olsen Citation1998). Given that firms clearly do not operate within an institutional vacuum (Eden Citation2010; Kostova, Roth, and Dacin Citation2008; Li and Qian Citation2013), in transition economies, however, social intimacy, corruption (Tanzi Citation1998) and favoritism (Barkemeyer, Preuss, and Ohana Citation2018; Estrin and Prevezer Citation2010) undermine formal regulatory institutions and provide a fertile breeding ground for informal institutions. Our research focuses on firms in Jordan, a country with an implementation deficit of formal regulatory institutions, high levels of corruption, and informal institutions operating outside the limits of formal regulatory requirements and in defiance of them, with implications beyond Jordan. More generally, we hope our concern to consider both formal regulatory institutions and informal institutions outside the developed countries’ institutional context will help revive the applicability of institutional theory to firm-level strategic environmental actions in less developed countries.

3. Hypotheses development

shows the hypothesized multi-level mediation model, which suggests that (1) political connections, normative connections, and business connections influence the environment-related cognitions of top managers; political, normative, and business connections are expected to communicate different information cues (cf. Scott Citation1995) and assign different privileges and permissions that affect the environment-related cognitions of well-connected top managers; (2) formal regulatory institutions predict firm-level environmental climate, which predicts, in turn, firm-level strategic environmental actions, thus treating firm-level environmental climate as a mediator.

3.1. Political connections and top managers’ environmental cognitions

We define political connections as unwritten and non-legally binding understandings that are continually produced and reproduced by top managers’ interactions with government officials, and public servants (Faccio, Masulis, and McConnell Citation2006) outside official channels (Sheng, Zhou, and Li Citation2011). Previous research has documented substantial evidence of politically connected top managers exploiting their political connections to bring more ‘privileges’ and ‘advantages’ to themselves and to their firms (Li et al. Citation2008; Shi, Xu, and Zhang Citation2018) in countries such as China (Zheng, Singh, and Mitchell Citation2015), Pakistan (Saeed, Belghitar, and Clark Citation2016), Italy (Infante and Piazza Citation2014), Indonesia (Fisman Citation2001), Thailand (Bunkanwanicha and Wiwattanakantang Citation2009), Malaysia (Johnson and Mitton Citation2003) and Taiwan (Yeh, Shu, and Chiu Citation2013), among others. Indeed, political connections contribute to queue jumping and rule bending activities (Baumol Citation1990; Helmke and Levitsky Citation2004; March and Olsen Citation1998; North Citation2005; Radaev Citation2004), preferential access to capital, licenses, contracts, permits, or land (Goldman, Rocholl, and So Citation2013; Peng and Luo Citation2000), tax exemptions (Adhikari, Derashid, and Zhang Citation2006), advocacy (Hillman, Keim, and, Schuler Citation2004; Mellahi et al. Citation2016), favorable regulatory interpretation (Luo Citation2003), and bailout should they encounter difficulties (Faccio, Masulis, and McConnell Citation2006; Li et al. Citation2008; Siegel Citation2007). This could be even more true in transition economies, where formal regulatory institutions are highly corrupt (Dinç Citation2005; Faccio Citation2006; Siegel Citation2007; Zhou Citation2013), underdeveloped (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2010; Welter and Smallbone Citation2011), least predictable (Peng and Luo Citation2000; Tan and Litschert Citation1994), bureaucratic (Eiadat et al. Citation2008), and replete with institutional voids (Khanna and Palepu Citation2010). Thus, political connections, with potential to facilitate such illegitimate ‘privileges’, are likely to negatively bias the environment-related cognitions of top managers. For example, political connections can allow well-connected top managers to think they are in control of formal regulatory institutions, probably even more than they really are, and thus feel safe to violate regulatory requirements or even ignore them altogether. Or, maintaining “disproportionately greater contact” (Child Citation1984, 154) with politicians and government bureaucrats in emerging economies may induce politically connected top managers to believe that deviation from regulatory requirements (Banfield, Citation1958; Lambsdorff, Schramm, and Taube Citation2006; Tanzi Citation1998) is possible, quite normal, and probably rational (Aidis and Adachi Citation2007; Rose Citation2000). Thus, we expect political connections to bias top managers’ environmental cognitions in a way that would facilitate widespread egregious and opportunistic environmental behavior.

Hypothesis 1: political connections will carry negative association with the environment-related cognitions of top managers.

3.2. Normative connections and managerial environmental cognitions

Normative institutions, such as educational research centers (Bice Citation2017), community groups (Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Peng and Lin Citation2008), and NGOs (Liu Citation2009), represent “rules-of-thumb, standard operating procedures, occupational standards, and educational curricula” (Hoffman Citation1999, 353). We suggest that strong normative connections arouse the moral environmental cognitions of top managers. For example, normative connections could enhance top managers’ environmental awareness of current environmental challenges and likely consequences on societies, and fuel feelings of shared social responsibility toward the environment as morally the appropriate thing to do. Indeed, as an “integrative force of solidarity” (Habermas Citation1994, 8) normative connection “actively socializes people to value certain things above others” (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998, 905), “not through force” (Colwell and Joshi Citation2013, 75), but through “the logic of appropriateness”, that is, what is appropriate rather than what is permitted. Indeed, “to the extent managers and key staff are drawn from the same universities and filtered on a common set of attributes, they will tend to view problems in a similar fashion, see the same policies, procedures and structures as normatively sanctioned and legitimated, and approach decisions in much the same way” (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983, 153).

From the academic literature, the evidence seems compelling that top managers’ shared normative values do influence their environment-related cognitions and behavior (Carballo-Penela and Castromán-Diz 2015; Delmas and Montes-Sancho Citation2011; Hall and Wagner Citation2012; Helmig, Spraul, and Ingenhoff Citation2016; Sancha, Longoni, and Giménez Citation2015; Vasudeva Citation2013). Anecdotally, “founder and former CEO of Interface Ray Anderson was fundamentally influenced by the generativity of his father, his coach and his professors (Douglas Creed, DeJordy, and Lok Citation2014), as well as ideas from Hawken’s (Citation1994) ‘Ecology of Commerce’, to construct his developmental path to become a generative business leader, and to establish his legacy as a leading international champion of corporate environmental stewardship” (Martinez Citation2019, 795).

Hypothesis 2: normative connections will carry positive association with environment-related cognitions of top managers.

3.3. Business connections and managerial environmental cognitions

In theory, supply chain members could punish firms for their poor environmental records or reward them for engaging in corporate social responsibility (Banerjee, Iyer, and Kashyap Citation2003). Customers, for example, played a significant part in boycotting companies with operations in apartheid South Africa and ultimately helped change not only the behavior of those companies but also South Africa’s political landscape. They also encouraged the Pharmaceutical companies to make AIDS drugs more accessible in Africa, and rewarded NIKE for ensuring fair wages and adhering to safe working conditions for Asian workers in Nike’s Asian factories.

There is ample evidence documenting ethical consumption (Nicholls Citation2010; Testa et al. Citation2015), consumers willing to pay a price premium for green products (Hiscox, Broukhim, and Litwin Citation2011), suppliers pushing other supply chain members to improve on their environmental performance (Battaglia et al. Citation2010; Testa, Styles, and Iraldo Citation2012), capital investors and financial institutions investing in responsible businesses (Cheng, Ioannou, and Serafeim Citation2014), customers’ overall positive evaluations (Becker-Olsen et al. Citation2011; Wagner, Lutz, and Weitz Citation2009), identification with (Bhattacharya and Sen Citation2003), and attributions (Vlachos et al. Citation2009) of environmentally friendly firms. Thus, we suggest that strong business connections with supply chain members – buyers (Airike, Rotter, and Mark-Herbert Citation2016; Henriques and Sadorsky Citation1999), suppliers (Darnall, Jolley, and Handfield Citation2008; Liu, Anderson, and Cruz Citation2012), and competitors (Sarkis, González-Torre, and Adenso-Díaz Citation2010; Tachizawa, Gimenez, and Sierra Citation2015) – contribute positively to the environment-related cognitions of top managers as financially ‘the right thing to do’.

As new green opportunities become more visible and economically viable (Hall Citation2000; Porter and Van der Linde Citation1995; Preuss Citation2005; Srivastava Citation2007; Yang et al. Citation2013), business connections with supply chain members become valuable information cues that may induce well-connected managers to develop new environmental solutions (Geffen and Rothenberg Citation2000; Rao Citation2002), create new opportunities, lower reputational risk exposure (Krall and Peng Citation2015), and improve environmental effectiveness (Lannelongue and González-Benito Citation2012). Business connections are, therefore, a filter through which top managers make sense of which supply chain members’ environmental concerns and demands are strategically too important to ignore, thus influencing their environment-related cognitions. Indeed, major companies in the auto industry, as part of the Suppliers Partnership for the Environment (SP), came together to identify creative projects and practices which advance sustainability while providing economic value. Pfizer, a major pharmaceutical company, helped to improve supply chain partners through environmental training and support (GEMI Citation2004). Since the sustainability-related concerns of supply chain members are on the rise (Hall Citation2000; Preuss Citation2005; Srivastava Citation2007; Yang et al. Citation2013), we expect top managers’ business connections with supply chain partners to carry positive association with their environment-related cognitions.

Hypothesis 3: business connections will carry positive association with the environment-related cognitions of top managers.

3.4. Formal regulatory institutions, environmental climate, and strategic environmental actions

The impact of formal regulatory institutions on firm-level strategic environmental actions has been extensively studied in both organizational theory and practice (Aragón-Correa and Sharma Citation2003; Darnall, Henriques, and Sadorsky Citation2010; Darnall, Potoski, and Prakash Citation2010). However, a lack of clarity on a firm-level pathway through which formal regulatory institutions reach firm-level strategic environmental actions remains. We propose firm-level environmental climate as a mediator between formal regulatory institutions and firm-level strategic environmental actions. The central idea behind climate as a mediator (cf. Cole, Carter, and Zhang Citation2013; Grizzle et al. Citation2009; Stoverink et al. Citation2014; Walumbwa, Hartnell, and Oke Citation2010) is that as firms are impelled to strategically act in ways that reflect their own environmental climates (Field and Abelson Citation1982), formal regulatory institutions’ ‘environmental calls’ to firm-level strategic environmental actions will be respected and implemented if they are echoed through firm-level environmental climate. Thus, formal regulatory institutions need to sway firm-level environmental climate in favor of regulatory requirements in order to positively impact firm-level strategic environmental actions. If formal regulatory institutions fail to do so, their influence on firm-level strategic environmental actions is expected to be insufficient, superficial, and not conducive to formal regulatory requirements.

Of course, top managers are expected to align their firm-level environmental climate with formal regulatory institutions if the regulatory requirements are perceived to be moderately stringent (Eiadat and Fernández-Castro Citation2018), strongly enforced (Heyes Citation2000), efficient (Niosi Citation2002), predictable (Engel Citation2005), and procedurally fair (Tyler Citation2006). Indeed, “the realities of the organization are understood only as they are perceived by members of the organization, allowing climate to be viewed as a filter through which objective phenomena must pass” (Litwin and Stringer Citation1968, 43, as cited in Mayer, Kuenzi, and Greenbaum Citation2010, 10). In this context, firm-level environmental climate mobilizes firm-level strategic environmental actions around formal regulatory requirements not only because law-abiding firm-level strategic environmental actions legitimate law-abiding firms more than their non-compliant peers (Deephouse Citation1996), but also because the perceived gap between formal regulatory requirements and firm-level environmental climate – routines, structures, and cognitions (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983) – is relatively small.

Hypothesis 4: firm-level environmental climate mediates the relationship between perceived formal environmental demands and firm-level strategic environmental actions.

4. Methods and measures

We conducted a systematic random sampling survey of private companies from the industrial sector in Jordan. The industrial sector is crucial for economic development in Jordan. The 2018 data from the Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) assessed its contribution to GDP at around 27 percent and to employment at around 24 percent. Yet, its impact on the environment, associated with its production, material use and disposal, is more pronounced for less developed countries such as Jordan. We employed the database available from the Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Supply in Jordan as our sampling frame. We distributed email invitations to 273 companies explaining the purpose of the study. CEOs and their senior management teams were invited to participate, and confidentiality was assured to respondents. All surveys were in Arabic and included measures of political connections, normative connections, business connections, environment-related cognitions of top managers, perceptions concerning formal regulatory institutions, and firm-level strategic environmental actions. CEOs were asked to complete a copy of the survey and distribute the rest to the most senior members of their team (minimum of two). 211 responses from 57 companies were received. Of which 199 responses from 53 companies were considered complete and used in the data analysis of the framework. This represented a response rate of 19.4% and average cluster of 3.6. As the response rate was quite low, non-response bias was performed by comparing age, size, and gender variables between early and late respondents (see Armstrong and Overton Citation1977). The data in show no significant differences, thereby retaining our null hypothesis that a non-response bias was unlikely in this study. The average age of an organization included in the sample was 14.8 years and the average size (measured by the number of employees) was 122.

Table 1. Non-response bias.

4.1. Measurement

4.1.1. Individual-level measures

Political connections: a 7-point Likert scale asked top managers to assess the extent to which they had utilized personal connections or ties over the last five years with (1) key officials in the government of Jordan, (2) key officials in the Ministry of Environment in Jordan, (3) senior officials in the Royal Administration for Environmental Protection, or (4) members of the Jordanian parliament (α = 0.843).

Normative connections: a 7-point Likert scale asked top managers to assess the extent to which they had utilized personal connections or ties over the last five years with (1) chambers of commerce and industry in Jordan (e.g. Jordan Chamber of Industry, Amman Chamber of Industry, Jordan Chamber of Commerce), (2) environmental organizations (e.g. Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature, Royal Scientific society, Jordan Environment Society), (3) educational research centers, or (4) professional associations (α = 0.882).

Business connections: a 7-point Likert scale asked top managers to assess the extent to which they had utilized personal connections or ties over the last five years with (1) customers’ companies, (2) suppliers’ companies, (3) distributors’ companies, or (4) competitors’ companies (α = 0.796).

Environment-related cognitions of top managers: a 7-point Likert scale was used to ask top managers to express their level of agreement with the following dimensions: (1) I would be happy to make financial sacrifices if it were important for the firm's environmental well-being, (2) in recent times, a firm’s survival depends on its response to the environmental impact of its activities, (3) reducing a firm’s impact on the environment leads to significant positive financial returns, (4) I “play it safe” and go above and beyond the environmental demands of the likes of regulators, customers, distributors, and suppliers (α = 0.860).

4.1.2. Firm-level measures

Formal environmental regulatory institutions: using a 7-point Likert scale, top managers were asked to express their levels of agreement with the following dimensions (1) violations of regulatory requirements are effectively detected by the Royal Administration for Environmental Protection in Jordan, (2) formal environmental regulatory institutions do not impose an unreasonable burden on businesses, (3) formal environmental regulatory institutions keep pace with scientific and technical developments in the fields of environmental standards, (4) overall, environmental decisions made by formal environmental regulatory institutions are reasonable and procedurally fair (α = 0.865).

We then aggregated top managers’ ratings of formal regulatory requirements to form a firm-level variable. contains data which shows that the aggregation was supported, average rWG(j) = 0.94, suggesting a high level of within-firm agreement for the assessment of formal environmental regulatory institutions (cf. Bliese Citation2002; LeBreton and Senter Citation2008), ICC(1) = 0.756, p = 0.000, indicating that firm membership explains almost 76% of the variance in top managers’ ratings of formal environmental regulatory institutions (Bliese Citation2002), ICC(2) = 0.925, p = 0.000 suggesting high reliability of firm means.

Table 2. ICCs and rWG.

Firm-level environmental climate: we aggregated the ratings of the environment-related cognitions of top managers to form a firm-level situational context variable – environmental climate (Ehrhart, Schneider, and Macey Citation2013). shows that average rWG(j) of 0.907, ICC(1) value of 0.624, p = 0.000, and an ICC(2) of 0.869, p = 0.000. Taken together, rWG(J), ICC(1), and ICC(2) support our aggregation of the environment-related cognitions of top managers into a firm-level environmental climate construct.

Firm-level strategic environmental actions: we adopted the following 4 items from a 7-point Likert scale which was used to ask top managers to assess the extent to which their companies over the last five years (1) modified manufacturing processes to reduce waste at source, (2) invested capital in green technology and pollution control equipment, (3) eliminated a product harmful to the environment, (4) acquired an environmental management system’s certification (α = 0.929). We then aggregated top managers’ ratings to form a firm-level strategic environmental actions variable. Results show that the aggregation was supported (average rWG(j) = 0.889, ICC(1) = 0.672, p = 0.000, and ICC(2) = 0.891, p = 0.000).

4.2. Model specification

As our bottom-up model (e.g. 1 – 2 – 2 model) involved mediation spanning firm and individual levels, we followed the Preacher, Zyphur, and Zhang (Citation2010) recommendation in analyzing the mediation effect at the firm-level and to test our model simultaneously rather than in a piecemeal approach. A note on the model’s general equations and how we modeled the mediation effect is as follows.

(1)

(1)

The subscript (i) is used to distinguish top managers and (j) is used to denote firms. In our study, there are 53 such equations, one for each firm. The regression coefficients, namely the intercept (β0) and the slope (β1), can vary from one firm to the next. EC11, for example, is the Environmental Cognition score for the first top manager in the first firm. β01 is the intercept for the first firm, is free to vary from, say, β053, the intercept for firm number fifty three. β0j is the intercept, the mean environment-related cognitions of top managers in the jth firm. The subscripts for the β coefficients include only numbers, which are used to distinguish one coefficient from another. For example, β1 is the coefficient (slope) for PC (political connections), is free to vary from β2 and β3 for NC (normative connections) and BC (business connections) respectively.

(2)

(2)

PCij represents the raw values of political connections provided by top managers. The subscripts here are particularly important in distinguishing fixed versus varying variables and coefficients. The i and j subscripts attached to the PC, NC, and BC variables in EquationEquations (2) (3)(3)

(3) , and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) show that these values can vary from one top manager to another and from one firm to the next. Coefficients, however, have a number attached to them (0) and a (j) subscripts, which means that they are fixed to a value that applies to every top manager in a firm, but are free to vary from one firm to the next for the PC, NC, and BC variables. β0Jpc, for example, is the intercept, the mean political connections score in the jth firm. rijpc is the random error of ith top manager in the jth firm for PC variable.

(3)

(3)

NCij represents the raw values of normative connections. β0jNC is the intercept, the mean normative connections score in the jth firm. rijNC is the random error of ith top manager in the jth firm for NC variable.

(4)

(4)

BCij represents the raw values of business connections. β0jBC is the intercept, the mean business connections score in the jth firm. rijBC is the random error of ith top manager in the jth firm for BC variable.

(5)

(5)

where γ00 and γ01 are level 2 coefficients, the mean value of all

and

across all of j firms. FI, Formal Institutions, represents level 2 predictor. It has only j subscripts because every top within a firm will have the same value for the level 2 FI variable.

(6)

(6)

EA, Environmental Actions, represents level 2 predictors. It has only j subscripts because every top manager within a firm will have the same value for the level 2 EA variable. is the mean environmental actions score across all of j firms.

is the level-2 coefficient for the

predictor.

is level-2 random effect across all of j firms.

5. Results

Correlations, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), McDonald Construct Reliability, Maximum Shared Variance (MSV), MaxR(H) are presented in and . The CR, AVE, and MaxR(H) exceeded the threshold values of 0.7, 0.5, 0.7 respectively. CR values are also greater than the respective AVE values. Taken together, they all indicate good construct reliability and convergent validity. Furthermore, the

values ranged from 0.722 to 0.824, and averaged 0.788 and the MSV values were less than their respective AVE values supporting the discriminant validity of our constructs.

Table 3. Correlations.

Table 4. Validity and reliability.

A CFA was conducted to test the distinctiveness among the model’s latent variables. Results in suggest that the hypothesized model fits the data well, χ2 (236) = 285, p = 0.0159, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.983, TLI = 0.980, SRMR = 0.052, Akaike (AIC) = 14,678.5, and Bayesian (BIC) = 14,968.3. Furthermore, this model fits the data significantly better than a four-factor model in which all informal institutions of political, normative, and business connections’ items loaded on a single factor, Δχ2 (9) = 1195.7, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.140, CFI = 0.665, TLI = 0.623, SRMR = 0.142, Akaike (AIC) = 15,571.2, ΔAIC = 892.7, Bayesian (BIC) = 15,831.3, ΔBIC = 863, and significantly better than a one factor model, Δχ2 (15) = 2094, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.192, CFI = 0.351, TLI = 0.287, SRMR = 0.176, Akaike (AIC) = 16,457.6, ΔAIC = 1,779.1, Bayesian (BIC) = 16,698, and ΔBIC = 1,729.7. The ΔAIC values of 863 and 1,779.1 and the ΔBIC values of 863 and 1,729.7 provide extra support for the discriminant validity of the hypothesized CFA Model (Akaike Citation1974; Burnham and Anderson Citation2004; Kass and Raftery Citation1995).

Table 5. Model fit.

We then estimated a multilevel mediation model, 2-2-1 model. Our results indicate that Model 1 has an acceptable fit (χ2 (88) = 103.4, p = 0.124, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.987, TLI = 0.983, SRMR (within) = 0.048, and SRMR (between) = 0.038). As shown in , our results suggest a significant negative relationship between political connections and environment-related cognitions of top managers (γ = −0.297, p < 0.01). This means that politically well-connected top managers develop significantly negative cognitions regarding the environment. This finding provides support for Hypothesis 1. We also established support for the significantly positive effect of normative connections on environment-related cognitions of top managers (γ = 0.097, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 2 is, therefore, supported. We also found the relationship between business connections and environment-related cognitions of top managers was significantly positive (γ = 0.149, p < 0.05), thus Hypothesis 3 was supported. The empirical support for Hypotheses 2 and 3 suggests that top managers with strong business and normative connections develop significantly positive cognitions regarding the environment.

Table 6. Results.

Finally, we examined the mediating effect of firm-level environmental climate. We found that perceived formal environmental regulatory institutions’ direct impact on firm-level environmental climate was significantly negative (γ = −0.375, p < 0.01), and the mediated effect on firm-level strategic environmental actions was also significantly negative (γ = −0.311, p = 0.01). These results provide support for Hypothesis 4.

6. Discussion

A key outcome is that politically connected top managers developed negative cognitions regarding the environment. Given the massive institutional changes since the Arab Spring, it could be argued that the legitimization power of formal regulatory institutions is in decline, while the ‘privileges’ of political connections have come to dominate (cf: North Citation1990; Powell Citation1990; Sheng, Zhou, and Li Citation2011). This is very obvious in the most recent revelations of what is locally known as the ‘cigarette scandal’ which could turn out to be the biggest corruption scandal in Jordan’s post Arab spring (cf: Bani-Mustafa Citation2018; Younes Citation2018). On the 25th of July of 2018, it was revealed that senior government officials and government agencies allegedly turned a blind eye to the running of a number of unlicensed cigarette manufacturing factories in the country by a Jordanian businessman who never paid corporate or income taxes for over five years. He was also allowed to forge international cigarette brands and sell them in Jordan and abroad without permission. Eventually, he was able to flee the country before a warrant for his and 29 others’ arrest was issued. This is a manifestation of the weak nature of formal regulatory institutions in Jordan, which is a breeding ground for illegitimate political connections.

This observation is consistent with previous research which has shown the negative impact of political connections on firm-level practices and behavior. Jia, Xinshu, and Yuan (Citation2019) found that politically connected firms in China were less likely to insure their managers and directors against legal liability. Wu, Wu, and Rui (Citation2012) reported similar results. They showed that politically connected private firms in China enjoy significant tax benefits. Fisman (Citation2001) confirmed that companies connected to President Suharto's family in Indonesia lost value following the news of the President’s declining health. Additional studies examining political connections in the Russian pharmaceutical industry and the Indian telecommunication industry produced evidence along the same lines (Klarin and Sharmelly Citation2021). It is, thus, not surprising that political connections were negatively associated with managerial environmental cognitions in Jordan.

Second, our results show that normatively connected top managers developed positive cognitions regarding the environment. This is very much in line with previous studies suggesting that normative institutions are able to instigate novel environmental solutions (Hart and Sharma Citation2004), trigger voluntary standards (Darnall, Potoski, et al. Citation2010; Delmas and Montes-Sancho Citation2011), and inspire proactive environment policies (Alt, Díez-de-Castro, and Lloréns-Montes Citation2015; Sancha, Longoni, and Giménez Citation2015; Sharfman, Shaft, and Tihanyi Citation2004; Sharma and Henriques Citation2005).

Similar evidence on normative connections is found in other emerging countries, including China and India. In the study by Dögl and Behnam (Citation2015) of 61 Indian and 31 Chinese firms, normative connections were positively associated with CSR practices. Furthermore, in a country sample of 27 developing and 72 developed countries, Lim and Tsutsui (Citation2012) found that normative connections were associated with firms’ substantive commitment to CSR. Another sample of 422 firms from China revealed that normative concerns were associated with environmentally friendly practices (Zhu, Geng, and Sarkis Citation2016).

Anecdotally, normative institutions managed to stop Korean steel giant POSCO from setting up a US$12 billion steel plant in India, block Japan Bank for International Cooperation from financing coal-fired energy projects in India (Wonacott Citation2007), and facilitate EMS implementation processes in Italy (Boiral, Heras‐Saizarbitoria, and Testa Citation2017; Testa, Styles, and Iraldo Citation2012). This implies that normatively well-connected top managers with active engagement with industry associations, strong participation at industry conferences, and significant contribution to the upkeeping of normative bodies, will develop positive cognitions regarding the environment as simply the morally “right thing to do” (Cennamo et al. Citation2012, 1154; Harrison, Bosse, and Phillips Citation2010).

Third, our results show that top managers with strong business connections developed positive cognitions regarding the environment. Strong business connections are likely to help top managers realize that responding to green customers, suppliers, investors, and competitors are the new business imperatives (Reinhardt Citation1999), and thus influencing their environmental cognitions. The literature shows that supply chain members have an impact on firms’ market expansion opportunities (Park and Luo Citation2001), profit growth potential (Sheng, Zhou, and Li Citation2011), timely access to quality information (Hoang and Antoncic Citation2003; Luo Citation2003; McEvily and Zaheer Citation1999), supply of quality materials (Peng and Luo Citation2000), experimentation cost (Levitt and March Citation1988), and transaction costs (Williamson Citation1985). Thus, we may surmise that strong business connections with such influential supply chain members will influence top managers’ cognitions and behavior in terms of championing tangible actions to improve the environment (e.g. recycling, preventing pollution), as suggested in Wang et al. (Citation2015).

Our results are consistent with prior findings that highlight the importance of business connections. For example, a study of 130 Italian organizations reveals a positive impact of business connections (financial institutions, customers and suppliers) on the implementation of the Social Accountability standards – SA8000 – (Boiral, Heras‐Saizarbitoria, and Testa Citation2017). Another sample of 328 firms certified to ISO 14001 from Australian and New Zealand reveals that business connections drive the adoption of ISO 14001 (Castka and Prajogo Citation2013). Majid et al. (Citation2020) also find that pressures from imitating the actions of successful competitors in Pakistan are associated with the development of environmentally friendly business strategies.

Fourth, results showed that there was sufficient common variance at the within-level environment-related cognitions of top managers to allow for firm-level environmental climate to emerge at the firm level. We, therefore, aggregated within-level environment-related cognitions of top managers to make inferences about firm-level environmental climate. Of course, aggregation “makes sense only if inferences are to be made about an aggregate unit of theory, such as organizational climate” (Glick Citation1985, 602). Firm-level environmental climate, as a cognitive framing, represents the consensual guidelines that are established by top managers to codify how organizational members should reflect and act upon environmental issues at the firm level. This theoretical modeling supports that assumption that “climate is a perception that resides within an individual, and only when perceptions are shared can there be a higher-level climate” (Jones and James Citation1979, as cited in Schneider et al. Citation2017, 471) and echoes Glick’s (Citation1985, 607) argument that firm-level environmental climate should be thought of and measured “at the organizational level of analysis”.

Finally, previous research has documented that formal regulatory institutions trigger firms to adopt internal compliance structures or codes of conduct (Bartley Citation2007; Delmas and Toffel Citation2008; Short and Toffel Citation2010). We submit that such structures or codes of conducts should be treated as mediators. Our results showed that the direct and mediated effect of formal regulatory institutions on firm-level environmental climate and firm-level strategic environmental actions were negative. This is not surprising since the general perception of formal regulatory institutions in Jordan is dominated by ‘whom you know’, “the end justifies the means” (Lefebvre Citation2001, 36-42) and “what leads to success is always correct” (Ledeneva Citation1998, 213), as cited in Tonoyan et al. (Citation2010). Thus, perceived procedurally unfair (Tyler Citation2006), underdeveloped (Puffer, McCarthy, and Boisot Citation2010), and inflexible (Ayres and Braithwaite Citation1992) formal regulatory requirements are expected to produce conducive firm-level environmental climate for non-compliant firm-level strategic environmental actions.

This observation is consistent with prior findings that highlight the negative association between former regulatory standards and firm-level environmental practices. For example, in the study by Sancha, Longoni, and Giménez (Citation2015) of 931 manufacturing plants from 22 countries across six sectors, coercive pressures to conform to formal regulatory standards were significant but negative

7. Theoretical implications and future research

We have learned that aggregation of constructs, both within and across firms, have important empirical potency for understanding firm-level outcomes. More specifically, we learned that the aggregations of scores for the environment-related cognitions of top managers helped firm-level environmental climate to emerge as a useful tool for understanding firm-level strategic environmental actions. We believe constructs’ aggregations have important and useful practical applications for a range of other firm-level outcomes that matter to environmental strategy research – green innovation, eco-efficiency, and eco-design, to name just a few. Aggregation, which is crucial for multi-level theory, of such important strategy constructs should help researchers explain additional variance beyond that explained by analogous individual level measures (Dragoni and Kuenzi Citation2012; Liao and Rupp Citation2005) and, thus, better explain differences between ‘within’ level and firm level.

The mediating effect of firm-level environmental climate confirms that, rather than theorizing a direct link between formal regulatory institutions and firm-level strategic environmental actions, more theoretical attention needs to be paid to the environment-related cognitions of top managers and firm-level environmental climate as the dynamics underlying firm-level strategic environmental actions.

There is a pressing research need for a better understanding of how firm-level environmental climate and firm-level strategic environmental actions change over time (Ehrhart, Schneider, and Macey Citation2013). We also need to learn more about how the environment-related cognitions of top managers become shared to form firm-level environmental climate over time. Further research devoted to, for example, examining the impact of potential moderators, such as top managers’ commitment to shareholder value, profit maximization, or moral objectives on shared environmental cognitions within and across firms would be an interesting line of future research, both theoretically and empirically.

There is also a need for more theoretical development on the antecedents of environment-related cognitions of top managers. In this study, we conceptualized environment-related cognitions of top managers in terms of political, normative, and business connections, but certainly other antecedents exist and should be examined.

8. Practical implications

In emerging economies, formal regulatory institutions should focus more on altering perceptions of regulatory requirements’ procedural fairness (Tyler Citation2006) and flexibility (Ayres and Braithwaite Citation1992) rather than on mandated standards, technologies, or actions that usually exist on paper but circumvented in practice. Our result indicates that unless firms’ perceptions of formal regulatory requirement are changed, formal regulatory institutions cannot produce conducive firm-level strategic environmental actions.

Governments may need to conduct a thorough examination of their regulatory requirements to get more insight into why top managers’ perceptions of such requirements were negative and consequently led to negative firm-level environmental climate and firm-level strategic environmental actions. Identifying potential reasons could help policymakers devise alternative environmental policies and regulatory requirements.

Companies committed to addressing their environmental impacts may need to delegate decision making authority to top managers with strong normative connections as normatively connected top managers develop positive cognitions regarding the environment.

Companies committed to shareholder value maximization through social responsibility may need to delegate decision making authority to top managers with strong business connections. Top managers with strong business connections can help their companies avoid overemphasizing the economic value of green business or underestimating the financial risks associated with overlooking supply chain members’ environmental concerns, thus better positioned to capture the added value that can emerge from the environment.

Companies committed to addressing their environmental impacts should be wary of delegating decision making authority to politically connected top managers. The misuse of an organizational position or its political connections for personal or organizational gains (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004, 40) may bring instant financial benefits (Li, Yao, and Ahlstrom Citation2015) but well-substantiated evidence suggests that politically connected firms are often associated with inefficiency, high risk, and poor performance (Faccio, Masulis, and McConnell Citation2006; Zhang, Tan, and Wong Citation2015).

9. Limitations

We only managed to collect data from 199 participants across 53 firms. It would be beneficial for researchers to replicate our model with a larger sample.

The 53 firms represented a Jordanian sample. Although our results are generalizable across various Jordanian national settings, they are less likely so beyond Jordan. More research on emerging economies is needed to increase generalizability.

As this research was cross-sectional, we were unable to examine the impact of formal regulatory institutions on firm-level strategic environmental actions over time or how the environment-related cognitions of top managers and firm-level environmental climate evolve over time. Longitudinal studies on this line of inquiry would be welcome.

References

- Adhikari, A.,. C. Derashid, and H. Zhang. 2006. “Public Policy, Political Connections, and Effective Tax Rates: Longitudinal Evidence from Malaysia.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 25 (5): 574–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2006.07.001.

- Aguinis, H., and A. Glavas. 2012. “What we Know and Don’t Know about Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 38 (4): 932–968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079.

- Ahlstrom, D., and G. D. Bruton. 2010. “Rapid Institutional Shifts and the Co-Evolution of Entrepreneurial Firms in Transition Economies.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (3): 531–554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00373.x.

- Aidis, R., and Y. Adachi. 2007. “Russia: Firm Entry and Survival Barriers.” Economic Systems 31 (4): 391–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2007.08.003.

- Airike, P. E., J. P. Rotter, and C. Mark-Herbert. 2016. “Corporate Motives for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Corporate Social Responsibility in the Electronics Supply Chains.” Journal of Cleaner Production 131 (10): 639–648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.121.

- Akaike, H. 1974. “A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification.” IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 19 (6): 716–723. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705.

- Alt, E., E. P. Díez-de-Castro, and F. J. Lloréns-Montes. 2015. “Linking Employee Stakeholders to Environmental Performance: The Role of Proactive Environmental Strategies and Shared Vision.” Journal of Business Ethics 128 (1): 167–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2095-x.

- Anand, V., B. E. Ashforth, and M. Joshi. 2004. “Business as Usual: The Acceptance and Perpetuation of Corruption in Organizations.” Academy of Management Perspectives 18 (2): 39–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.13837437.

- Aragón-Correa, J. A., and S. Sharma. 2003. “A Contingent Resource-Based View of Proactive Corporate Environmental Strategy.” Academy of Management Review 28 (1): 71–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.8925233.

- Armstrong, J. S., and T. S. Overton. 1977. “Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys.” Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3): 396–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320.

- Ayres, I., and J. Braithwaite. 1992. Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Banerjee, S. B., E. S. Iyer, and R. K. Kashyap. 2003. “Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type.” Journal of Marketing 67 (2): 106–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.106.18604.

- Banfield, E. C. 1958. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. New York: The Free Press.

- Bani-Mustafa, A. 2018. “Gov’t Issues Travel Ban on 7 Suspects Involved in ‘Forged’ Tobacco Case.” The Jordan Times, July 22. http://jordantimes.com/

- Bansal, P., and I. Clelland. 2004. “Talking Trash: Legitimacy, Impression Management, and Unsystematic Risk in the Context of the Natural Environment.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (1): 93–103.

- Barkemeyer, R., L. Preuss, and M. Ohana. 2018. “Developing Country Firms and the Challenge of Corruption: Do Company Commitments Mirror the Quality of National-Level Institutions?” Journal of Business Research 90: 26–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.025.

- Bartley, T. 2007. “Institutional Emergence in an Era of Globalization: The Rise of Transnational Private Regulation of Labor and Environmental Conditions.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (2): 297–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/518871.

- Battaglia, M., L. Bianchi, M. Frey, and F. Iraldo. 2010. “An Innovative Model to Promote CSR among SMEs Operating in Industrial Clusters: Evidence from an EU Project.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17 (3): 133–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.224.

- Baumol, W. J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (5, Part 1): 893–921. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/261712.

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., C. R. Taylor, R. P. Hill, and G. Yalcinkaya. 2011. “A Cross-Cultural Examination of Corporate Social Responsibility Marketing Communications in Mexico and the United States: Strategies for Global Brands.” Journal of International Marketing 19 (2): 30–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.19.2.30.

- Bhattacharya, C. B., and S. Sen. 2003. “Consumer-Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies.” Journal of Marketing 67 (2): 76–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609.

- Bice, S. 2017. “Corporate Social Responsibility as Institution: A Social Mechanisms Framework.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (1): 17–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2791-1.

- Bliese, P. D. 2002. “Multilevel Random Coefficient Modeling in Organizational Research: Examples Using SAS and S-Plus.” In The Jossey-Bass Business and Management Series. Measuring and Analyzing Behavior in Organizations: Advances in Measurement and Data Analysis, edited by F. Drasgow, and N. Schmitt, 401–445. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Boiral, O., I. Heras‐Saizarbitoria, and F. Testa. 2017. “SA8000 as CSR‐Washing? The Role of Stakeholder Pressures.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 24 (1): 57–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1391.

- Bolinger, A. R., A. C. Klotz, and K. Leavitt. 2018. “Contributing from Inside the Outer Circle: The Identity-Based Effects of Noncore Role Incumbents on Relational Coordination and Organizational Climate.” Academy of Management Review 43 (4): 680–703. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0333.

- Bruton, G. D., D. Ahlstrom, and H. L. Li. 2010. “Institutional Theory and Entrepreneurship: Where Are we Now and Where Do we Need to Move in the Future?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (3): 421–440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x.

- Bruton, G. D., D. Ahlstrom, and K. S. Yeh. 2004. “Understanding Venture Capital in East Asia: The Impact of Institutions on the Industry Today and Tomorrow.” Journal of World Business 39 (1): 72–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2003.08.002.

- Bunkanwanicha, P., and Y. Wiwattanakantang. 2009. “Big Business Owners in Politics.” Review of Financial Studies 22 (6): 2133–2168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn083.

- Burnham, K. P., and D. R. Anderson. 2004. “Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection.” Sociological Methods & Research 33 (2): 261–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644.

- Carballo‐Penela, A., and J. L. Castromán‐Diz. 2015. “Environmental Policies for Sustainable Development: An Analysis of the Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategies in the Service Sector.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (8): 802–818.

- Castka, P., and D. Prajogo. 2013. “The Effect of Pressure from Secondary Stakeholders on the Internalization of ISO 14001.” Journal of Cleaner Production 47: 245–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.034.

- Cennamo, C.,. P. Berrone, C. Cruz, and L. R. Gomez-Mejía. 2012. “Socioemotional Wealth and Proactive Stakeholder Engagement: Why Family-Controlled Firms Care More about Their Stakeholders.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (6): 1153–1173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00543.x.

- Chatterji, A. K., and M. W. Toffel. 2010. “How Firms Respond to Being Rated.” Strategic Management Journal 31 (9): N /a–945. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.840.

- Cheng, B., I. Ioannou, and G. Serafeim. 2014. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance.” Strategic Management Journal 35 (1): 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2131.

- Child, J. 1984. Organization: A Guide to Problems and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Clemens, E. S., and J. M. Cook. 1999. “Institutionalism: Explaining Durability and Change.” Annual Review of Sociology 25 (1): 441–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.441.

- Cole, M. S., M. Z. Carter, and Z. Zhang. 2013. “ Leader-Team Congruence in Power Distance Values and Team Effectiveness: The Mediating Role of Procedural Justice Climate.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 98 (6): 962–973. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034269.

- Colwell, S. R., and A. W. Joshi. 2013. “Corporate Ecological Responsiveness: Antecedent Effects of Institutional Pressure and Top Management Commitment and Their Impact on Organizational Performance.” Business Strategy and the Environment 22 (2): 73–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.732.

- Darnall, N., I. Henriques, and P. Sadorsky. 2010. “Adopting Proactive Environmental Strategy: The Influence of Stakeholders and Firm Size.” Journal of Management Studies 47 (6): 1072–1094. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00873.x.

- Darnall, N., G. J. Jolley, and R. Handfield. 2008. “Environmental Management Systems and Green Supply Chain Management: Complements for Sustainability?” Business Strategy and the Environment 17 (1): 30–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.557.

- Darnall, N., M. Potoski, and A. Prakash. 2010. “Sponsorship Matters: Assessing Business Participation in Government and Industry-Sponsored Voluntary Environmental Programs.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20 (2): 283–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mup014.

- Deephouse, D. L. 1996. “Does Isomorphism Legitimate?” Academy of Management Journal 39 (4): 1024–1039. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/256722.

- Delmas, M. A., and M. J. Montes-Sancho. 2011. “An Institutional Perspective on the Diffusion of International Management System Standards: The Case of the Environmental Management Standard ISO 14001.” Business Ethics Quarterly 21 (1): 103–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20112115.

- Delmas, M. A., and M. W. Toffel. 2008. “Organizational Responses to Environmental Demands: Opening the Black Box.” Strategic Management Journal 29 (10): 1027–1055. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.701.

- Denzau, A. T., and D. C. North. 1994. “Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions.” Kyklos 47 (1): 3–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1994.tb02246.x.

- Dheer, R. J. 2017. “Cross-National Differences in Entrepreneurial Activity: Role of Culture and Institutional Factors.” Small Business Economics 48 (4): 813–842. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9816-8.

- DiMaggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

- Dinç, I. S. 2005. “Politicians and Banks: Political Influences on Government-Owned Banks in Emerging Markets.” Journal of Financial Economics 77 (2): 453–479.

- Dögl, C., and M. Behnam. 2015. “Environmentally Sustainable Development through Stakeholder Engagement in Developed and Emerging Countries.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (6): 583–600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1839.

- Doh, J. P., P. Rodríguez, K. Uhlenbruck, J. Collins, and L. Eden. 2003. “Coping with Corruption in Foreign Markets.” Academy of Management Perspectives 17 (3): 114–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2003.10954775.

- Donnellon, A., B. Gray, and M. G. Bougon. 1986. “Communication, Meaning, and Organized Action.” Administrative Science Quarterly 31 (1): 43–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2392765.

- Douglas, M. 1986. How Institutions Think. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Douglas Creed, W. E., R. DeJordy, and J. Lok. 2014. “Myth to Work by: Redemptive Self-Narratives and Generative Agency for Organizational Change.” In Religion and Organization Theory, 4, edited by P. Tracey, N. Phillips, and M. Lounsbury, 111–158. Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Dragoni, L., and M. Kuenzi. 2012. “Better Understanding Work Unit Goal Orientation: Its Emergence and Impact under Different Types of Work Unit Structure.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 97 (5): 1032–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028405.

- Dutton, J. E., L. Fahey, and V. K. Narayanan. 1983. “Toward Understanding Strategic Issue Diagnosis.” Strategic Management Journal 4 (4): 307–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250040403.

- Eden, L. 2010. “Letter from the Editor-in-Chief: Lifting the Veil on How Institutions Matter in IB Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (2): 175–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.92.

- Ehrhart, M. G., B. Schneider, and W. H. Macey. 2013. Organizational Climate and Culture: An Introduction to Theory, Research, and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Eiadat, Y., and A. M. Fernández-Castro. 2018. “The Inverted U‐Shaped Hypothesis and Firm Environmental Responsiveness: The Moderating Role of Institutional Alignment.” European Management Review 15 (3): 411–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12135.

- Eiadat, Y., A. Kelly, F. Roche, and H. Eyadat. 2008. “Green and Competitive? An Empirical Test of the Mediating Role of Environmental Innovation Strategy.” Journal of World Business 43 (2): 131–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.11.012.

- Engel, C. 2005. Generating Predictability: Institutional Analysis and Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Estrin, S., and M. Prevezer. 2010. “A Survey on Institutions and New Firm Entry: How and Why Do Entry Rates Differ in Emerging Markets?” Economic Systems 34 (3): 289–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2010.01.003.

- Faccio, M. 2006. “Politically Connected Firms.” American Economic Review 96 (1): 369–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806776157704.

- Faccio, M., R. W. Masulis, and J. J. McConnell. 2006. “Political Connections and Corporate Bailouts.” The Journal of Finance 61 (6): 2597–2635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.01000.x.

- Field, R. G., and M. A. Abelson. 1982. “Climate: A Reconceptualization and Proposed Model.” Human Relations 35 (3): 181–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678203500302.

- Finnemore, M., and K. Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52 (4): 887–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550789.

- Fiske, S. T., and S. E. Taylor. 1984. Social Cognition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Fisman, R. 2001. “Estimating the Value of Political Connections.” American Economic Review 91 (4): 1095–1102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.4.1095.

- Garcés‐Ayerbe, C., P. Rivera‐Torres, and J. L. Murillo‐Luna. 2012. “Stakeholder Pressure and Environmental Proactivity: Moderating Effect of Competitive Advantage Expectations.” Management Decision 50 (2): 189–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211203524.

- Gavetti, G., and D. Levinthal. 2000. “Looking Forward and Looking Backward: Cognitive and Experiential Search.” Administrative Science Quarterly 45 (1): 113–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2666981.

- Geffen, C. A., and S. Rothenberg. 2000. “Suppliers and Environmental Innovation: The Automotive Paint Process.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 20 (2): 166–186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570010304242.

- GEMI. 2004. Forging New Links: Enhancing Supply Chain Value through Environmental Excellence. Working Paper, Global Environmental Management Initiative - GEMI. http://gemi.org/supplychain/resources/ForgingNewLinks.pdf

- Glick, W. H. 1985. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Organizational and Psychological Climate: Pitfalls in Multilevel Research.” Academy of Management Review 10 (3): 601–616. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4279045.

- Glick, W. H. 1988. “Response: Organizations Are Not Central Tendencies: Shadowboxing in the Dark, Round 2.” Academy of Management Review 13 (1): 133–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306813.

- Goldman, E., J. Rocholl, and J. So. 2013. “Politically Connected Boards of Directors and the Allocation of Procurement Contracts.” Review of Finance 17 (5): 1617–1648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfs039.

- Gómez-Haro, S., J. A. Aragón-Correa, and E. Cordón-Pozo. 2011. “Differentiating the Effects of the Institutional Environment on Corporate Entrepreneurship.” Management Decision 49 (10): 1677–1693.

- Greenwood, L., J. Rosenbeck, and J. Scott. 2012. “The Role of the Environmental Manager in Advancing Environmental Sustainability and Social Responsibility in the Organization.” Journal of Environmental Sustainability 2 (1): 1–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.14448/jes.02.0005.

- Grizzle, J. W., A. R. Zablah, T. J. Brown, J. C. Mowen, and J. M. Lee. 2009. “Employee Customer Orientation in Context: How the Environment Moderates the Influence of Customer Orientation on Performance Outcomes.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (5): 1227–1242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016404.

- Gröschl, S., P. Gabaldón, and T. Hahn. 2019. “The Co-Evolution of Leaders’ Cognitive Complexity and Corporate Sustainability: The Case of the CEO of Puma.” Journal of Business Ethics 155 (3): 741–762. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3508-4.

- Habermas, J. 1994. “Three Normative Models of Democracy.” Constellations 1 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.1994.tb00001.x.

- Hall, J. 2000. “Environmental Supply Chain Dynamics.” Journal of Cleaner Production 8 (6): 455–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(00)00013-5.

- Hall, J., and M. Wagner. 2012. “Integrating Sustainability into Firms' Processes: Performance Effects and the Moderating Role of Business Models and Innovation.” Business Strategy and the Environment 21 (3): 183–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.728.

- Harrison, J. S., D. A. Bosse, and R. A. Phillips. 2010. “Managing for Stakeholders, Stakeholder Utility Functions, and Competitive Advantage.” Strategic Management Journal 31 (1): 58–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.801.

- Hart, S. L., and S. Sharma. 2004. “Engaging Fringe Stakeholders for Competitive Imagination.” Academy of Management Perspectives 18 (1): 7–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2004.12691227.

- Hawken, P. 1994. The Ecology of Commerce. New York: Harper Business.

- Helmig, B., K. Spraul, and D. Ingenhoff. 2016. “Under Positive Pressure: How Stakeholder Pressure Affects Corporate Social Responsibility Implementation.” Business & Society 55 (2): 151–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650313477841.

- Helmke, G., and S. Levitsky. 2004. “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda.” Perspectives on Politics 2 (04): 725–740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472.

- Henriques, I., and P. Sadorsky. 1999. “The Relationship between Environmental Commitment and Managerial Perceptions of Stakeholder Importance.” Academy of Management Journal 42 (1): 87–99.

- Heyes, A. 2000. “Implementing Environmental Regulation: Enforcement and Compliance.” Journal of Regulatory Economics 17 (2): 107–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008157410380.

- Hillman, A. J., G. D. Keim, and D. Schuler. 2004. “Corporate Political Activity: A Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 30 (6): 837–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.003.

- Hiscox, M. J., M. Broukhim, and C. Litwin. 2011. Consumer Demand for Fair Trade: New Evidence from a Field Experiment Using eBay Auctions of Fresh Roasted Coffee. Working Paper. SSRN. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1811783

- Hoang, H., and B. Antoncic. 2003. “Network-Based Research in Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (2): 165–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00081-2.

- Hoffman, A. J. 1999. “Institutional Evolution and Change: Environmentalism and the US Chemical Industry.” Academy of Management Journal 42 (4): 351–371.

- Hoffman, A. J., and P. D. Jennings. 2015. “Institutional Theory and the Natural Environment: Research in (and on) the Anthropocene.” Organization & Environment 28 (1): 8–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615575331.

- Hörisch, J., J. Kollat, and S. A. Brieger. 2017. “What Influences Environmental Entrepreneurship? A Multilevel Analysis of the Determinants of Entrepreneurs’ Environmental Orientation.” Small Business Economics 48 (1): 47–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9765-2.

- Infante, L., and M. Piazza. 2014. “Political Connections and Preferential Lending at Local Level: Some Evidence from the Italian Credit Market.” Journal of Corporate Finance 29: 246–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.06.003.

- James, L. R., R. G. Demaree, and G. Wolf. 1984. “Estimating Within-Group Interrater Reliability With and Without Response Bias.” Journal of Applied Psychology 69 (1): 85–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85.

- James, L. R., W. F. Joyce, and J. W. Slocum. 1988. “Comment: Organizations Do Not Cognize.” Academy of Management Review 13 (1): 129–132. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306808.

- Janis, I. L. 1972. Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign Policy: Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Jia, N., M. Xinshu, and R. Yuan. 2019. “Political Connections and Directors' and Officers' Liability Insurance: Evidence from China.” Journal of Corporate Finance 58: 353–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.06.001.

- Johannesson, R. E. 1971. “Job Satisfaction and Perceptually Measured Organizational Climate: Redundancy and Confusion.” In New Developments in Management and Organization Theory: Proceeding of Eight Annual Conference, edited by M. W. Frey, 27–37. Boston, MA: Eastern Academy of Management.

- Johnson, D. R., and D. G. Hoopes. 2003. “Managerial Cognition, Sunk Costs, and the Evolution of Industry Structure.” Strategic Management Journal 24 (10): 1057–1068. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.320.

- Johnson, S., and T. Mitton. 2003. “Cronyism and Capital Controls: Evidence from Malaysia.” Journal of Financial Economics 67 (2): 351–382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00255-6.

- Jones, A. P., and L. R. James. 1979. “Psychological Climate: Dimensions and Relationships of Individual and Aggregated Work Environment Perceptions.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 23 (2): 201–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(79)90056-4.

- Kaplan, S. 2011. “Research in Cognition and Strategy: Reflections on Two Decades of Progress and a Look to the Future.” Journal of Management Studies 48 (3): 665–695. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00983.x.

- Kass, R. E., and A. E. Raftery. 1995. “Bayes Factors.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 773–795. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572.

- Kassinis, G., and N. Vafeas. 2006. “Stakeholder Pressures and Environmental Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (1): 145–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785799.

- Khanna, T., and K. G. Palepu. 2010. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.