Abstract

Measures that integrate social, economic and ecologic land use functions have increasingly raised the interest of scholars and practitioners concerned with sustainability. However, achieving effective integration involves important governance challenges. One challenge is that actors need to work across social, cognitive and physical boundaries. This article studies how actors span, but also challenge, defend and construct boundaries over time during integrative processes, and what temporal sequences of boundary actions help to realize effective integration. It does so with a comparative longitudinal analysis of two cases of Multifunctional Land Use. We find three main patterns: First, to bridge boundaries, they first need to be created, strengthened and explicated, whilst also connecting actors where possible. Second, after a period of spanning and challenging, reconstructing boundaries can help to keep the process manageable, provide safety and maintain autonomy. Third, challenging boundaries is often necessary to realize integration, even when this stirs up conflicts and internal discussions.

1. Introduction

Measures that integrate different social, economic and ecological land use functions have increasingly raised the interest of scholars and practitioners concerned with sustainability. Examples of such measures are realizing multifunctional urban squares which are used for recreation but also serve as water retention areas in times of high precipitation, and green-blue infrastructures combining waterfronts and flood management, green space, community development, and economic functions. This integration of land use functions allows for the creation of synergies between functions and the simultaneous provision of ecological and socio-economic services. Integration of land use functions thereby enables greater overall performance and more sustainable development (Lovell and Taylor Citation2013; Roe and Mell Citation2013). However, the implementation of such approaches, involving a multitude of stakeholders and high organizational and technological complexity, is challenging (Van Broekhoven and Vernay Citation2018; Johns Citation2019; Roe and Mell Citation2013). Although multifunctional land use (MLU) usually sees wide support during the initial phase, its complexity ensures that only some endeavors are successful. This leads to excessively lengthy processes, cost-overruns, and projects that fail to be realized.

One challenge is that multifunctional and integrated processes cut across boundaries e.g. of sectors, organizations, tasks, roles, ideas, in territories. The question as to how actors can deal with boundaries in integrative processes has recently gained attention in spatial planning (van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015; Westerink Citation2016). When actors specify integration as their aim, they are confronted with boundaries. Realizing integrative processes requires actors from different backgrounds to transcend well-established boundaries. At the same time, they will run into others drawing boundaries, and will define or defend boundaries that are helpful for their own actions. We know that effective integration is complicated by the need and/or desire to maintain boundaries, e.g. to ensure fulfilling functional tasks, divide responsibilities and maintain hegemony in the wider political-administrative environment. The process that unfolds after actors identify the potential of MLU is thus one of differentiation and integration.

Studies on boundaries show how working across boundaries can be facilitated by, for example, the activities of boundary spanners (Noble and Jones Citation2006; Williams Citation2002), and joint construction of boundary objects (Star and Griesemer Citation1989). Other studies however find actors predominantly engaging in strategies to defend and maintain boundaries in integrative planning processes to protect established sectoral ways of working and interests, thereby hampering integration (Degeling Citation1995; Derkzen, Bock, and Wiskerke Citation2009). Yet, others find drawing boundaries can also be good to divide tasks and keep complexity manageable (Hernes Citation2003; van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015). Several recent studies analyze the enabling and constraining effects of different types of boundary actions and show that realizing effective integration requires spanning boundaries as well as challenging and drawing boundaries (Hernes Citation2003; van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015; Westerink Citation2016). Each can be beneficial for realizing integration, but can also constrain it. This raises the question when in integrative processes which types of boundary actions and configurations of actions are helpful to realize integration. When will spanning boundaries help or constrain the integrative process, and when will drawing boundaries help or constrain? Currently, little is known about how managing boundaries takes place over time in integrative processes. The aim of this paper is to analyze how actors manage boundaries over time in integrative planning processes, and what sequences of boundary actions help to realize effective integration of functions. To achieve this, we conduct a longitudinal analysis of how actors manage boundaries during the integrative process in two cases of multifunctional land use in The Netherlands. More specifically, we analyze sequences of boundary actions over time in the case studies, i.e. how actors span, challenge, change, defend and construct boundaries during the process that unfolds when they engage in integrative planning processes. To do so, we build on earlier conceptualizations of boundaries and an approach for process analysis that compares empirical processes to theoretical expectations.

2. Conceptualizing boundary management

Managing boundaries is a central issue for actors who work on integrative land use processes (Van Broekhoven Citation2020). Boundaries are in essence sites of difference—ways of differentiating something from what it is not (Abbott Citation1995; Hernes Citation2004). Following Hernes (Citation2003), Abbott (Citation1995) and others, we view boundaries as socially constructed, constantly interpreted, shaped and contested by actors with different perspectives, and ambiguity. They are enacted in interactions where they are made explicit, are shaped, enforced, or form a matter of contention (van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015). Boundaries are recurring “distinctions and differences between and within activity systems that are created and agreed on by groups and individual actors over a long period of time while they are involved in those activities. These distinctions and differences can be categorizations of material objects, people and practices” (Kerosuo Citation2006, 4). Hence, boundaries are shaped by being acted upon over and over again. They do not exist independently of such enactment, and thus need to be studied through the interactions of the people who enact them (van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015). Paradoxically, they may at the same time be perceived as real by actors even before an integrated initiative is started and shapes their actions.

2.1. Boundary actions in integrative planning processes

Therefore, rather than researching how interaction across predefined (e.g. sectoral) boundaries takes place, we analyze the enactment of boundaries by actors in specific empirical contexts. We conceptualize the interactions that result from the contradictory tendencies of differentiation and integration in terms of boundary actions; the practices that actors employ to manage boundaries (Kerosuo Citation2006; Paulsen and Hernes Citation2003; van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015; Yan and Louis Citation1999). We analyze how actors manage boundaries in integrative processes by reconstructing the boundary actions of the actors involved, i.e. how they draw, span, contest, defend and negotiate boundaries during the process. To do so, we build on a framework developed by van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015, which provides a typology of boundary actions that enables us to analyze boundary management through reconstructing actors’ boundary actions. Moreover, we develop this approach further by analyzing how actors manage boundaries (i.e. perform boundary actions) over time, how this changes over the course of a particular process, and what that tells us about what sequences of boundary actions help to realize effective integration of functions.

Following van Broekhoven et al. (Citation2015) we define boundary actions as: “A recurring set of articulations, actions, and interactions that shape a demarcation, taking place over a longer period of time” (van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015, 5). In order to identify and study actors’ boundary actions, van Broekhoven et al. (Citation2015) specify three main types of boundary actions:

Spanning boundaries in integrative processes whilst respecting the distinction it entails, e.g. to facilitate coordinating practices or exchange information across boundaries. Spanning facilitates flow across a boundary without challenging its relevance or place. We distinguish actions that span boundaries through developing coordination structures (e.g. project groups) and through developing more dense relationships.

Drawing and maintaining boundaries, e.g. to demarcate who or which problems and solutions are included, to protect or buffer something from conflicting interest, or to enable successful action within. We distinguish here actions that activate or defend boundaries and that are aimed at dividing tasks and responsibilities

Challenging and negotiating boundaries, e.g. by problematizing existing ideas or divisions. Actors challenge boundaries to e.g. include new actors, ideas, or resources. This is different from spanning boundaries, as actions here involve changing a previous demarcation. Multifunctionality generally implies challenging boundaries to realize integration.

The literature on organizational boundaries, boundary spanning and integrative work provides insights on the more specific activities by which actors span, draw or challenge boundaries in integrative processes, and how this can hamper or enable these processes. In , we summarize these insights from previous literature. We categorize these using the three main types of action. While boundaries are often perceived as problematic for cooperation, recent studies have shown that boundaries can also be helpful in organizing activities, e.g. by specializing toward certain tasks or dividing responsibilities. The idea behind integrative planning processes is thus not to annihilate boundaries, but to connect the bounded subsystems in such a way that joint benefits are produced.

Table 1. Boundary actions to manage boundaries in integrative processes, and their effects, identified in previous literature.

2.2. Sequences of boundary actions

We assume that how actors manage boundaries (i.e. perform boundary actions) over time during the planning process affects the extent to which they are able to realize effective integration of land use functions. One way to analyze this, is to count how often the three main types of boundary actions described in Section 2.2. occur during the process. However, we do not think this will explain when integration will be successful. Instead, we propose to look at the sequence of actions over time. We will therefore reconstruct and analyze the temporal sequence of boundary actions that actors take during the process in the two cases, and how this explains whether integration of functions was successful. Next, we will analyze what patterns we can identify in these sequences of boundary actions. We do so by systematically comparing the sequences in the case studies to each other and to earlier findings on temporal sequences of boundary actions.

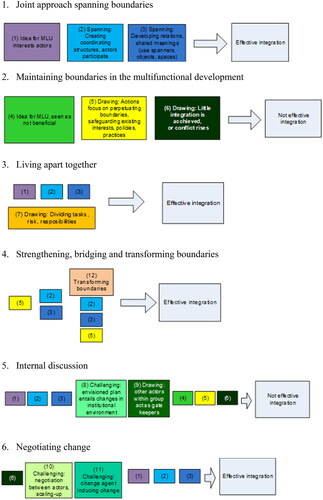

We assessed the literature on earlier findings on temporal sequences of boundary actions. First, we find that how actors can best manage boundaries over time is often only implicitly reported, in the sense that the focus is often on identifying single tools or actions that enable actors to span boundaries or, in contrast, how they do not succeed in this (e.g. how boundary objects or boundary spanners can facilitate interaction), rather than on how boundary management takes place over time during integrative or collaborative processes. Second, we nevertheless could draw six distinct sequences of boundary actions from the implicit descriptions in the literature, see . We discuss these below.

Joint approach spanning boundaries

Many governance studies focus on boundary spanning as a strategy to come to alignment in integrative planning processes. Here, effective integration is expected to develop when actors take a ‘joint approach’ throughout the process facilitated by activities of boundary spanners (Noble and Jones Citation2006), jointly producing boundary objects (Klerkx et al. Citation2012), creating safe spaces for interaction and formal coordination structures (Clark et al. Citation2010).

Maintaining boundaries in the multifunctional development

Other studies find that actors in response to an integrative initiative predominantly develop strategies to perpetuate and defend boundaries (Degeling Citation1995; Derkzen, Bock, and Wiskerke Citation2009). Here, the integrative initiative is expected to lead to discussions between actors with conflicting interests and views. Actors protect their policies, practices and desires. Consequently, little meaningful participation takes place, leading to few opportunities to develop alignment and conflict.

Living apart together

Some scholars state managing boundaries in integrated work is a balancing act between drawing boundaries and interacting across them (Clark et al. Citation2010; Hoppe Citation2010; van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015), or talk about the paradox of differentiation and integration (Marshall Citation2003; Tushman and Scanlan Citation1981); actors need to change or cross boundaries to enable integration and coordinate activities as well as drawing on them to divide tasks and keep complexity manageable (Hernes Citation2003; van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015). Here, drawing and spanning takes place simultaneously during integrative processes.

Strengthening, bridging and transforming boundaries

Ernst and Chrobot-Mason (Citation2010) and Lee, Magellan, and Ernst (Citation2014) provide the most explicit description on how boundaries can be managed successfully over time. They describe first how boundaries need to be created or strengthened. By buffering (e.g. clarifying purpose, specialization) safety is created, and by reflecting across boundaries an understanding is built that fosters respect. Next, common ground needs to be forged, developing a shared goal and identity. Here actors form new networks and relationships and reframe boundaries to develop a new community. Last is transforming boundaries. Here, established practices, norms and identities are crossed to enable innovation. This is about integrating and differentiating; groups keep distinct identities, expertise and resources but are ‘woven’ together, working on a shared strategy and vision.

Internal discussion

Some studies identify that integrative initiatives will lead to internal discussions (e.g. van Meerkerk Citation2014). Actors working on an integrative project have to deal with the expectations and demands – and ensure support – of their own group and of those with whom they negotiate, making their position inherently ambiguous and leading to tensions (Long Citation2001; Swan and Newell Citation1998). Friedman and Podolny (Citation1992) differentiate two types of boundary workers in this respect: ‘representatives’ bringing information from the organization to their environment and ‘gatekeepers’ regulating what comes in. These internal discussions are expected to hamper effective integration.

Negotiating change

Several studies show that when contradictions and conflict rise, leaders (e.g. politicians) acting as change agents can provide an essential push by supporting possible solutions and inducing change (Degeling Citation1995; Klerkx, Aarts, and Leeuwis Citation2010). Developing a solution that suits all can moreover be facilitated by boundary-spanning activities and the creation of coordination structures. This process may take place both externally and between departments within organizations (Katz and Tushman Citation1979).

The above leads to three main types of boundary actions, and in total 12 sub-types of actions: the ‘building blocks’ that make up the sequences of actions derived from the literature. We will proceed by reconstructing and analyzing whether and in what sequences these actions occur in the two cases and compare this to the sequences in .

2.3. Assessing effective integration

Finally, we need to establish whether and how the sequences of boundary actions in the case studies contribute to realizing effective integration. However, the effects of sequences of boundary actions on an outcome of effective integration are not easy to assess. Both the process as a whole, individual boundary actions, sequences of boundary actions together, as well as contextual factors, which are not analyzed in this study, all contribute to the outcome of the process. This outcome therefore cannot be simply reduced to causal effects of sequences of actions. Nevertheless, if we want to be able to better and more strategically manage boundaries in future integrative initiatives, it is important to gain better insight into how different ways to manage boundaries help in realizing effective integration. Here, we take the first steps for this by assessing what sequences of boundary actions help to realize effective integration in two ways. First, we analyze to what extent the process as a whole led to effective integration. To do so, we base ourselves on actors’ contentment (Edelenbos and Klijn Citation2006), commonly used to assess success in governance studies. We define effective integration as: Functions are integrated with each other and are adequately fulfilled. This means the actors that use, own or manage these functions should be satisfied with the way functions relevant to them are fulfilled within the multifunctional development, and the integration as a whole. Secondly, we analyze how specific sequences of boundary actions had intermediate effects during the process, by mapping the intermediate effects that are named by respondents in interviews and project documents. Together, these judgements of the involved actors are used to arrive at an informed interpretation of what sequences help in realizing effective integration of functions.

3. Methods

To study how actors manage boundaries over time in integrative processes we conduct a longitudinal analysis of two cases. We selected the cases following the principle of maximization, i.e. choosing a situation where the process of interest manifests itself most strongly and is ‘transparently observable’ (Boeije Citation2009; Pettigrew Citation1990). In the selected cases, actors integrate a primary sea levee with other functions in The Netherlands. Given the important historical role and position of flood protection in The Netherlands, this provides a socially relevant setting where boundaries as traces of past activities are strongly present. Furthermore, to study actors’ boundary actions over time we selected cases in a late stage of implementation.

The process analysis requires reconstructing the narrative on how the process evolved (Langley 1999; Sminia Citation2009). The decision-making and implementation process of the two cases is reconstructed and analyzed, focusing on boundary actions and sequences of boundary actions. Data is gathered by: (a) semi-structured interviews with key actors who were involved at different points in the process, from the organizations involved; (b) analyzing documents from the period studied; (c) observation of actors’ interactions during a short period of time; and (d) workshops with stakeholders (see ). Using multiple data sources reduces the risk of distortions in post-factual accounts and increases internal validity. Documents were collected through respondents and websites of the organizations involved, interviews were transcribed. To identify and reconstruct boundary actions over time, a chronological database was developed by selecting from each interview, document and observation, articulations of incidents that indicate the activation, contestation or crossing of a boundary. This is an interpretive act by the researchers. These actions were then coded with the aim of identifying occurrences of the three main types of boundary actions (Section 2.2), and 12 sub-types of actions in the sequences derived from the literature (Section 2.3). Our chronological database consists of 55 boundary actions in Westduinpark and 197 in Dakpark. For each case, a workshop was organized with the main stakeholders, at the end of 2014. In the workshops, the reconstruction and analysis of boundary actions was presented, discussed, and validated with the participants.

Table 2. Data collection.

Obviously, our reconstruction does not represent all boundary actions that occurred. Reconstructing all actions that happened over time is not humanly possible or desirable. Given our method of data collection we assume that we have captured at least the most significant boundary actions; also, there is no a priori reason to suppose our method biases a particular type of action.

To identify and analyze sequences of boundary actions we take the following two steps. First, we distinguish several separate but related lineages that take place in the two cases. Actors in integrative initiatives need to deal with multiple discussions on boundaries simultaneously. Not all boundary actions are directly related, e.g. technical discussions on a levee take place separately from residents’ participation. To identify lineages we used a method developed by Spekkink and Boons (Citation2016) that identifies network communities with an algorithm developed by Blondel et al. (Citation2008). These lineages were then validated by presenting them in the workshops with key actors involved in the case. We asked participants if they could label what the lineages were about. This led to some changes in attribution of actions to lineages, see Appendix A. We analyzed a total of 11 lineages in the two cases. These lineages evolve around specific discussions on a boundary and can occur simultaneously or follow each other. Second, we analyze patterns in the sequences of boundary actions within these lineages. We do so by reconstructing how and in what sequences the three main types of actions and 12 sub-actions occur in the lineages, and matching the sequence that we find per lineage to the sequences identified in the literature We thereby build on an approach to analyze empirical processes by comparing them to theoretical expectations on how the process develops (Boons, Spekkink, and Jiao Citation2014; Jiao and Boons Citation2017; Spekkink and Boons Citation2016). This approach allows us to systematically compare the empirical process with theoretical expectations, and to compare multiple empirical processes with each other. Matching the empirical sequence in the case studies to the sequences in the literature was done manually, facilitated by color coding. To systematically perform this comparison, we established a set of rules when a particular sequence was attributed. These are discussed in Appendix A.

Finally, to analyze actors’ contentment with the process as a whole, we conducted a short survey with the participants of the workshops. We asked them to score and explain how satisfied they are with the way functions relevant to them are fulfilled within the multifunctional development, and with the integration as a whole. To analyze intermediate effects of sequences of boundary actions, we identify what intermediate effects are named by respondents in the interviews and (project) documents. Based on these judgements of the actors involved in the integrative process we make an informed interpretation of what that tells us about which sequences of boundary actions help to realize effective integration of function.

4. Results

We first introduce each case, discuss the sequences of boundary actions found in the studied lineages and their intermediate outcomes, and actors’ contentment with the process as a whole. Next, we identify patterns in these sequences by comparing them across both cases and with the sequences derived from the literature.

4.1. Process analysis Westduinpark

4.1.1. Introduction

The Westduinpark is a 232 hectare former city park located in the coastal zone directly adjacent to the city of The Hague in The Netherlands. In the previous century, this area was planted with trees and shrubbery to hold the sand of this dune area in place. In 2002, the municipality started a process to improve the natural quality of the area by bringing it back to its original state in which natural dune processes such as sand drift return. This involved a significant transformation of the area, including large scale removal of existing flora. In 2003, the area was appointed as Natura 2000. In the area, several other social-economic functions exist, alongside the ecological function. It is used intensively for recreation, with 1.9 mln. visits per year. On the west side lie beach restaurants, on the east side urban residential areas. The dunes moreover form a primary sea defence structure, governed by a water board and planted with grasses to stabilize the sand. Therefore, in order to realize nature goals and at the same time find a balance with these other functions, the municipality started a discussion with the stakeholders related to these functions. During the process, several discussions arose on boundaries. These discussions focused on: the development of a management plan, the nature quality vs existing recreation, the communication with residents and nature permits, and coastal dynamics vs water safety regulations (see below). In 2011, a Natura 2000 management plan was agreed upon and the removal of existing flora started. In spring 2014, most measures were implemented, apart from those for the sea defence. Actors expected the targets in the Natura 2000 plan could mostly be met, but not completely.

4.1.2. Boundary actions during the process

We analyze four lineages within the process, which evolved around specific discussions on boundaries. The process is reconstructed from 2002 (when the idea arose) until spring 2014 (largely implemented). presents an illustration of the key boundary actions and actors involved.

Table 3. Key boundary actions Westduinpark.

Developing a management plan

At the start of the process, the municipality developed a nature management plan. Throughout this lineage, actors undertook mainly boundary spanning actions (e.g. developing a vision, excursions, installing a management platform). These activities were mainly limited to actors within the municipal organization, in order to reach agreement on a nature management plan between different sectors within the municipality. In addition, two actions were about claiming the nature function of the area (appointing it as Natura 2000, and making a zoning plan), and thereby establishing boundaries.

Nature quality in relation to existing recreation

In 2005-2013 a main issue was presenting and discussing the plans with residents using the area for recreation and local nature and resident organizations. Here we find a sequence of boundary spanning and maintaining actions that take place interspersed and in reaction to each other. Quite a lot of residents and residents’ organizations first opposed the nature management plan, drawing boundaries. In response, municipal actors undertook various boundary spanning actions (e.g. setting up a working group, field trips, individual communication with critical residents). Whilst some residents became supportive of the plans, a few remained critical.

Preparing implementation: nature permits and communication

The discussion here arose during the implementation of the measures in the nature management plan, involving a drastic removal of vegetation in the park. We find here again boundary spanning and maintaining actions interspersed throughout the process, in reaction to each other. From early on, the municipality started a communication process for residents to gain support, spanning boundaries through, for example, information evenings, presentations, and excursions. Residents were critical at first, but became more positive over time. However, during the work, bats were accidentally disturbed, leading to a discussion with national authorities. To proceed, the municipality adjusted its plans. Hereafter, criticism by residents rose again. To regain support, municipal actors undertook further boundary spanning activities.

Dynamic coastal management in relation to water safety permits

Municipal actors also needed to discuss the nature management plan with the water board – responsible for water safety provided by the dunes – and the province – responsible for the Natura 2000 goals. Noticeably, whilst actors early in the process span boundaries by involving the water board in meetings on the nature management plan, the permit department of the water board rejected the permit at a late stage of the process, because the plan did not fit with water safety policy, thereby acting as gatekeeper. By aiming to realize sand drift, the nature management plan challenged boundaries in existing policy, which determined a certain amount of sand should be present within a specific geographical dune area appointed as a water safety structure. This came as a surprise for municipal actors and resulted in conflict between the organizations. Hereafter, internal discussion arose within the water board. Whilst some actors in the water board tried to find solutions to enable the nature management plan, others stood by the existing rules and practices. In the process to resolve this conflict, we find that civil servants from the water board undertook boundary spanning activities to facilitate interaction with the municipality, but also to gain support internally to find a solution that enabled the nature management plan. In addition, a politician from the water board supported and prioritized that a solution should be found, acting as change agent. Finally, a solution was developed that involved mutual adaptation of the water safety policy and the nature management plan. At the end of the process, it is noticeable that besides spanning boundaries, we also find actions that reconstruct boundaries (e.g. the water board required the municipality to monitor the consequences of measures and if needed take mitigating measures, and they jointly established conditions under which sand drift was allowed).

4.1.3. Actors’ reflection and contentment regarding the whole process

Respondents reflected on the integration between functions and fulfillment of their own function as good to very good. They reflected that nature goals were largely realized, and increased support for the plans was realized. At the same time, nature goals were not completely realized. Respondents reflected on the collaboration process as satisfactory or good. One respondent argued that it was an achievement that something was realized at all, as working together was not easy due to the societal and institutional context. The discussion on the water safety permit was reflected upon as difficult, but respondents from different organizations stated that after a difficult start increased understanding and joint solutions were developed.

4.2. Process analysis dakpark

4.2.1. Introduction

The Dakpark is a development of an 8 ha. park on the roof of a commercial building, extending down to street level over already existing rail tracks, a levee, and heating infrastructure. It takes place in the city of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. The plan first arose in 1998 when a former train shunting yard between a harbor and a disadvantaged neighborhood was partly dismantled, and multiple claims on the future use of this area were made: residents asked for a neighborhood park, while the municipality and Port Authority wanted harbor-related business development. Moreover, several functions were already present in the area, including a primary sea levee and city heating infrastructure. To develop this idea, the municipality started a complex interaction process involving a multitude of actors related to these functions. At the end of 2011, the commercial building was delivered. Construction of the roof park started in 2012, but was stopped when physical problems regarding the city heating led to new discussions between the municipality and energy company.

4.2.2. Boundary actions during the process

We analyze seven lineages within the process. The process is reconstructed from 1998 (idea arose) to 2012 (largely implemented). presents an illustration of the key boundary actions and actors involved.

Table 4. Key boundary actions Dakpark.

From conflicting claims to a joint project

In this lineage, the two competing claims on the area were brought together in the integrative initiative: a long held demand of residents for a neighborhood park versus plans of the municipality for business development. Here, we find a sequence of boundary spanning and maintaining actions interspersed and in response to each other. The idea for Dakpark integrated the two seemingly contradictory claims, thereby both bridging and changing these. To gain support, municipal actors who developed the plan performed boundary spanning activities and hired a local advisor to communicate with and involve residents (e.g. by organizing mini-conferences, setting up an advisory group, meetings with resident groups, excursions). However, residents responded with criticism to the plan (e.g. doubting whether a park on a roof could become a ‘real’ park rather than just a grass rooftop) and established a residents’ organization to represent their interests, drawing boundaries.

Resident participation

From 2000, an intensive resident participation process started. Here, we find many spanning and drawing actions that took place simultaneously. Especially at the start (2000-2002), residents undertook activities to safeguard that the plan met their interests. Residents amongst others developed ‘eight commandments’ for the park, which were formally presented to the alderman and were used throughout the further process as criteria to judge whether the park satisfied their wishes. One of the commandments, for instance, was that the roofpark should contain at least one meter of soil, so that ‘real’ trees could grow in it. This became a symbol for the residents to represent their demands for the park. Through these activities, residents reinforced boundaries in terms of their demands on the content of the project. In parallel, the municipality undertook more boundary spanning actions (e.g. workshops, excursions, organizing the Dakpark café where actors could formally and informally interact). This interspersing of spanning and drawing continued for several years. Later in this sequence we find only boundary spanning. Respondents reflected that this process led to increased support for the plan.

(De)rail

This lineage is about removing a function rather than integrating. The decision to remove rail tracks triggered the idea for Dakpark Rotterdam. In the subsequent process, we observe actions that maintain boundaries, as discussions arose on how many tracks should be removed and who should finance it. Later, we find some actions spanning boundaries (meetings). However, municipal actors reflect that boundary spanning was limited, e.g. there was no regular contact at the railroad company that was involved over time, and it was difficult to obtain information. In the end, municipal actors forced an agreement by scaling-up the discussion to the upper management level of both railroad company and national government. Respondents reflect on this process as difficult.

Demarcation, interfaces

This lineage involves the interaction between municipality and project developer to construct a public park on top of a private building. We find here again that actors both spanned and drew boundaries. We find that during their collaboration, the municipality and project developer encountered a lack of clarity about who does what for the parts where the park and building meet (e.g. the roofing between park and building, and the lift and stairs leading up to the park) and how to manage the risks of the public park on the private building (e.g. leakage). Interestingly, to deal with this, actors in increasing detail constructed new boundaries by dividing public and private tasks and risks, in 2005-2009. They, for instance, demarcated in the physical structure of the roofing material exactly which layer of roofing belonged to the municipality and which to the project developer. Respondents reflect upon these demarcations between public and private as being needed and helpful to develop the integrative project. At the same time, they spanned boundaries by, for example, coordinating their activities in a joint project group. In addition, in 2008, an internal discussion arose within the municipal organization. This revolved around (technical) requirements put forward by specialized departments, which complicated the negotiations on a joint project agreement.

Water

This boundary discussion is about integrating the plan with an existing levee. Throughout this lineage we find activities to maintain boundaries (e.g. actors articulated little integration was possible with the levee, actors could not reach agreement on possibilities to include water safety measures in the structure of the building, the water board did not participate in the joint project group). Nevertheless, the municipality planned to construct the Dakpark across the levee, within a physical zone protected by water safety policy, hence challenging this boundary. In 2007, a conflict arose when the water permit was provided, but involved unexpected conditions that were seen as impossible by the municipality and project developer. Subsequently, distinct from the sequence of maintaining boundaries, an alderman played a crucial role by deciding the municipality would meet the conditions, acting as a change agent. The process resulted in an uneasy co-existence, and was reflected upon as very sensitive by the respondents.

Energy company

Here, we again find interspersed maintaining and spanning of boundaries. Similar to lineage 5, the municipality and energy company communicated bilaterally. Noticeably, we found little boundary activities at all between 2001 and 2012, (only some meetings in 2006-2008). This changes when, in 2012, the city heating infrastructure was found to be tilted, which necessitated the municipality and energy company to work together. Subsequently, actors of both organizations spanned and drew boundaries in a process of negotiation. In the workshop, participants reflected that they personally interact on good terms, but disagree on financing and responsibility. A municipal actor stated ‘We agree to disagree.’

Retail

This boundary discussion arose when, due to changes in economic circumstances, actors changed the designation of the commercial building from harbor-related business development to retail. However, this new destination did not fit with existing retail policy and we found gatekeeping activities by municipal actors responsible for this policy. Actors working on Dakpark tried to gain support for the new plan by various boundary spanning activities (e,g, organizing meetings and lobbying). In 2006, an alderman decided the Dakpark should be realized despite the retail policy, acting as a change agent. In the subsequent process, actors tried to negotiate a compromise that enabled the Dakpark, whilst also retaining the retail policy as much as possible. To do so, they defined in detail the conditions under which the new retail destination is allowed, thereby redrawing boundaries.

4.2.3. Actors’ reflection and contentment regarding the whole process

Respondents reflected on the integration between functions as moderate, stating a unique park was realized, functions were stacked, and conflicting interests met. However, they criticized the relationship between parts; the connection between park and building and neighborhood and shops was seen as limited, the sum of the parts could be bigger, and a joint vision was lacking. One respondent argued that too many interests were combined; making it vulnerable when one fails. Another questioned the need to stack functions. Respondents reflected on the fulfillment of their own function as satisfactory. The collaborative process was seen as moderately successful, raising two critiques: First, the lack of time taken during the process to reflect on the consequences of choices. Second, issues with large potential (financial) impact (e.g. levee, roofing) were dealt with too late in the process.

4.3. Comparing sequences of boundary actions

presents the sequences of boundary actions found in the 11 lineages within the two cases and how they match with the sequences derived from the literature. It moreover presents the intermediate outcomes per lineage. The comparison of the sequences shows that in many lineages we find a sequence of boundary spanning and drawing actions taking place interspersed and throughout the process, often in reaction to each other. We find this at different moments in the process, in different orders (i.e. first spanning then drawing or vice versa), and with different intermediate effects.

Table 5. Comparison of sequences and intermediate outcomes.

First, in the interaction between residents, the municipality and local organizations in Westduinpark lineage 2 and 3 and Dakpark lineage 1 and 2, initiating actors spanned boundaries to gain support for the integrative idea. In reaction, others reinforced boundaries to ensure the plan met their interests. Especially in the resident participation process in Dakpark, we found that residents undertook various activities to safeguard that the plan met their interests (i.e. defending boundaries). This drawing, in combination with boundary spanning, did not mean that functions could not be combined, or that the interaction was negative, as was expected in the sequence on maintaining boundaries derived from the literature. On the contrary, respondents stated that these processes mostly led to increased support over time. We conclude that reinforcing boundaries in terms of demands on the design of the park enabled the residents to clarify and guard their interests and make clear what important boundaries were. This is seen, for instance, in the use of the ‘eight commandments’. At the same time, municipal actors initiated many boundary-spanning activities, which facilitated the interaction and enabled actors to reflect across boundaries. It is important to note here that the boundary drawing and spanning actions only together – complementing each other – led to the effects discussed here. This matches with the first part of the sequence described by Ernst and Chrobot-Mason (Citation2010) and Lee, Magellan, and Ernst (Citation2014), that at the start of an interaction boundaries should first be strengthened and created, as by buffering (e.g. clarifying purpose, specialization) safety is created, and by reflecting across boundaries an understanding is built that fosters respect. We elaborate upon their findings by showing that in parallel to strengthening, the boundary spanning activities were also important. This is furthermore underlined by lineages 3 and 6 in the Dakpark case. In these lineages, actors also drew boundaries at the start of the process, but only later and limitedly combined this with boundary spanning actions. This led to a situation where the railroad company and energy company stood at more of a distance from the project (for instance they did not participate in the joint project group). The respondents were critical of these interactions. We conclude that to work across boundaries it is helpful to first identify and draw boundaries in order to clarify and guard interests and create an understanding and respect for the different viewpoints and interests that need to be taken into account. At the same time, this should be combined with connecting where possible to facilitate interaction and come to joint ideas on the project.

Second, we find the sequence of interspersed spanning and drawing of boundaries in the interaction between project developer and municipality regarding the public park and private building in Dakpark (lineage 4). Noticeably here, drawing activities focused on dividing tasks and responsibilities, rather than making demands clear. Interestingly, to deal with lack of clarity about who does what on the interface between public and private responsibilities, actors choose to divide tasks and responsibilities for the parts where they met, rather than keeping these issues collective. At the same time, actors closely collaborated and undertook boundary spanning activities, such as coordinating their activities in a joint project group. Respondents reflected that reconstructing boundaries enabled them to deal with ambiguity on private and public responsibilities, and to keep the project manageable. This matches the sequence on ‘living together apart’ and elaborates upon earlier studies that show boundaries also have important functions in organizing tasks and keeping complexity manageable (Hernes Citation2003). At the same time, respondents reflected that the relationship between different functions in the Dakpark (e.g. park and building, neighborhood and shops) could have been stronger. We conclude that drawing boundaries in both sequences described above facilitated realization by providing actors with a degree of safety, order, and autonomy, but also limited the degree of integration that was realized.

We also find interspersed drawing and spanning after the conflict that arose in Westduinpark (lineage 4). This sequence matches with the sequence on internal discussions derived from the literature, followed up and modified by the sequence on negotiating change. This sequence shows the role of boundary spanning activities to come to a solution that suits all, and the role of change agents to provide an essential push by supporting possible solutions and inducing change, in line with earlier studies (e.g. Degeling Citation1995; Klerkx, Aarts, and Leeuwis Citation2010). However, while based on the literature, we had expected that boundary spanning activities would be the final steps needed to bring about effective integration, here in addition we find actions redrawing boundaries at the end of the process (e.g. monitoring the consequences of measures and demanding mitigating measures, if needed, and establishing conditions for allowing sand drift). Actors thereby redefined the conditions, responsibilities and new ways of working for the new situation - in effect reconstructing boundaries. Respondents from the municipality and water board reflected that in this process of spanning and drawing they developed increased understanding of each other over time. In lineage 7 in Dakpark, actors in a similar manner define the conditions under which the new retail destination is allowed in great detail, in order to protect the retail policy.

We, moreover, find that conflicts and internal discussions arise in both cases. Striking is that in both cases conflicts only become clear at a late stage in the process. In both cases only at a very late stage of the process, when after years of interaction about the integrative project the water permit is issued, it becomes clear that important aspects of the integrative plan are not allowed in the water permit. Only at this point, the discussion is really started with regard to which compromises can be made between functional interests, and what kind of new solutions can be found to enable the integrative plan. At the core of these conflicts lie conflicting sectoral interests, which could have been addressed earlier in the process. For instance, in the Dakpark case, actors for a long time try not to challenge but work around and avoid established boundaries regarding the levee. However, the project, in the end, does involve building in the protected zone of the levee. This leads to a rather unhappy marriage, reflected upon negatively by actors in the water board.

In addition, we find that multiple times a sequence of internal discussions arises on whether to accommodate certain changes to existing boundaries (e.g. in legislation, ways of working, task division) which are proposed to enable the integrative initiative. This is shown in the discussions on allowing sand drift within the protected water safety zone in Westduinpark (lineage 4), in the discussions on whether to allow retail (lineage 7), and the discussions between municipal actors on the root- and waterproof roofing (lineage 4) in Dakpark, and is in line with the sequence on internal discussions derived from the literature (e.g. Long Citation2001; van Meerkerk Citation2014). To resolve internal discussions, boundary spanning activities were important in both cases. We found that (political) change agents and boundary spanners played an important role to intermediate and enable or enforce organizational change, confirming earlier studies (e.g. Klerkx, Aarts, and Leeuwis Citation2010; Degeling Citation1995). Contrary to our expectations, however, we find that after a period of internal cross-boundary negotiation and making changes actors also redefined boundaries, as discussed above.

A sequence of dominantly maintaining boundaries was found once, in the discussion regarding the levee in Dakpark. Consequently, actors kept apart, confirming the expectation that mostly drawing boundaries does not enable effective integration. Interestingly, functions were still physically stacked. This led to an uneasy co-existence and negative reflections. In contrast, we found mostly boundary spanning actions in lineage 1 of Westduinpark, mainly involving municipal actors. In contrast to the expectations, the fact that several further discussions on boundaries arose when the municipal plan was presented to other stakeholders implies that this sequence of boundary spanning alone was not enough to realize the plan.

Summarizing the above, we identify three patterns in the sequences of boundary actions and how these can be helpful to realize effective integration of functions in the 11 lineages that are studied within the two cases. These are discussed further in section 5.

To work across boundaries, boundaries first need to be created, strengthened and explicated, whilst also connecting where possible.

After a period of spanning and challenging boundaries, reconstructing boundaries can help to keep the process manageable, provide safety and maintain autonomy.

Challenging boundaries is often necessary to realize integration, but actors can and should expect this to lead to conflicts and internal discussions during the integrative process.

5. Conclusions and discussion

Our analysis shows that integrating functions is not only about spanning boundaries, although our findings underline that activities to span boundaries (e.g. organizing formal and informal interaction in a joint project group, workshops, excursions, activities by [political] change agents) facilitate interaction and are important to realize integrative initiatives (Klerkx, Aarts, and Leeuwis Citation2010; Tushman and Scanlan Citation1981; Williams Citation2002). This research shows that making clear what hard boundaries are and (re)constructing boundaries is equally necessary at different moments during the process. Whilst the enabling effects of drawing boundaries have been shown before, the main focus in the debate on integrative work is on the question of how boundaries can be spanned in order to facilitate collaboration. This research brings back the attention on to how boundaries also have enabling effects. Realizing effective integration requires both spanning, challenging and drawing boundaries. Each can be beneficial for realizing integration, but can also constrain it. So, when in integrative processes which boundary actions and sequences of actions are helpful? The analysis elaborates upon earlier work on enabling and constraining effects of different types of boundary actions (cf. van Broekhoven et al. Citation2015; Van Broekhoven and Van Buuren Citation2020; Westerink Citation2016; Hernes Citation2003), by providing further insight on when in integrative processes which sequences of actions help to realize effective integration of functions.

We identify three patterns in the sequences of boundary actions in the 11 lineages that are studied within the two cases, which shed new light on how boundaries can be best managed over time in future integrative initiatives. As with any case study, these findings are context dependent. They will need to be tested in further empirical studies.

To work across boundaries, boundaries first need to be created, strengthened and explicated, whilst also connecting where possible

Paradoxically, we find that it is helpful to first identify and draw boundaries at the start of an integrative process, in order to clarify and guard interests and create an understanding and respect for the different viewpoints and interests that need to be taken into account. This is seen in the sequence of actions in the resident participation process in Dakpark (lineage 1 and 2) and Westduinpark (lineage 2 and 3), for instance in the use of the ‘eight commandments’. This pattern is in line with earlier findings by Ernst and Chrobot-Mason (Citation2010) and Lee, Magellan, and Ernst (Citation2014), indicating that it is not only limited to the cases studied here. However, we elaborate upon this by emphasizing that this should be combined with connecting where possible to facilitate interaction and come to joint ideas on the project. The beneficial effects discussed here were a result of both boundary drawing and spanning actions together – complementing each other.

The cases also show the opposite: a situation where actors drew boundaries at the start of the process, but combined only sparsely with boundary spanning. As a result, the involved actors stood more at a distance from the project. We also found lineages where – for various reasons – boundaries were kept vague. The risk here is that unexpected challenges will arise, as seen in the Westduinpark case where at a late stage a water permit was unexpectedly rejected and it became clear that there was still a discussion to be held within the water board.

This pattern does not mean that actors should or can make all boundaries clear at the start of the process. This research shows that what important boundaries are is not readily visible and can change over time. Moreover, we find that actors need to juggle multiple discussions on boundaries at the same time.

After a period of spanning and challenging boundaries, reconstructing boundaries can help to keep the process manageable, provide safety and maintain autonomy.

The analysis furthermore reveals that it can be helpful to reconstruct boundaries after a period of boundary spanning and negotiating boundaries. One of the difficulties actors face in integrative projects is that by integrating functions, tasks, risks, responsibilities become overlapping and blurred. Constructing (new) boundaries in terms of who does or owns what after a period of boundary spanning can help actors to deal with tasks and responsibilities that become blurred, overlapping and shared in the integrative initiative. Dividing tasks and responsibilities can make the project more manageable. This is seen in the interaction between municipality and project developer in Dakpark. Furthermore, the research indicates that after a period of (internal) cross-boundary negotiation and making changes, redefining the conditions, responsibilities and new ways of working for the new situation enables actors to ensure the degree of change keeps within certain limits that they feel are important. This is seen in set 4 in Westduinpark and lineage 7 in Dakpark, and is in line with some earlier findings (Kerosuo Citation2006; Mørk et al. Citation2012). We conclude that (re)constructing boundaries after a period of working across boundaries provides a certain degree of order, safety and autonomy that is important for actors and organizations working in integrative initiatives in order to be comfortable with integrative measures.

Challenging boundaries is often necessary to realize integration, but actors can and should expect this to lead to conflicts and internal discussions during the integrative process.

Actors often need to challenge boundaries to enable an integrated initiative (e.g. in legislation, existing ways of working, or roles and tasks) and realize organizational change. The cases show that this stirs up conflicts and internal discussions. Integration does not only imply benefits. What is good for one function is not always good for another. Striking is that, in the case studies, conflicts only become clear at a late stage in the process. The lesson that we draw from this – further supporting the conclusions on the benefits of drawing boundaries – is that actors can better address inevitable tensions between interests by making clear what hard boundaries are at an early stage, rather than keeping these quiet or trying to avoid them. Making clear what is at stake can be hard, as it addresses potential conflicts head on. However, studies show that conflicts in collaborative projects are not, by definition, negative but can also be valuable, as they can fuel the creativity needed to find new solutions, and addressing them early can prevent escalation of the conflict later on in the process (Wolf and Van Dooren Citation2017).

Moreover, in reaction to the changes required to enable the integrative initiatives, others within the organization resist and protect existing practices and policies. Discussions on boundaries consequently spill over into the internal organization (see lineage 4 in Westduinpark, and lineage 4 and 7 in Dakpark), confirming earlier studies (e.g. van Meerkerk Citation2014). In their daily actions, actors represent boundaries in their own ways. Different representatives have different roles within an organization, and thereby may represent organizational interests differently and construct boundaries differently. This becomes especially clear in lineage 4 in Westduinpark. An important lesson that we draw from the cases is that it is important to involve, from early on, not just those representatives who are good at working across boundaries (e.g. policy officers or strategists), but also those who are responsible for guarding boundaries to ensure the organizations’ own tasks (e.g. enforcing body).

Regarding the methodology, the approach to analyze the cases by comparing the empirical sequences of boundary action to sequences derived from the literature enabled us to systematically compare the empirical processes with the literature and across cases, and thereby provide better insight into the generality of the case study findings. However, the different explanations for the sequences of interspersed spanning and drawing show that to understand how managing boundaries takes place we need at least an actor-based explanation as a complement to the sequence of actions. The analysis also leads to new questions for future research. First, obviously a study with two cases is limited in terms of generality. More research is needed to provide a broader basis for conclusions on sequences of boundary actions in integrated planning processes and their effects. Second, more insight is needed into the conditions under which specific sequences occur and have a certain outcome. For instance, although the power relationships between actors and the political process are not the focus of this research, the analysis does provide some insights into how power relationships shape how boundaries are drawn and evolve and consequently what kind of integration is possible. For example, in The Netherlands, water safety is a dominant and strongly supported interest, and water boards consequently have a powerful position. A water board has the authority to regulate what actions are possible in the physical area around water safety infrastructures, and hence to defend boundaries (Van Broekhoven Citation2020). Such unequal power relationships can prevent wider societal transformation such as integration of land use functions from taking place (Turnhout et al. Citation2020). In both our cases, the initiating actors aim to realize activities for other functions within the protected area of a levee, and this established boundary is defended and largely maintained by the water board involved. How then, can we stimulate water boards to change their practices for the benefit of initiatives for integrated land use? In the Westduinpark case, actors working on nature conservation gain a stronger position to challenge and change previous ideas on boundaries, as the area is appointed as a protected Natura 2000 area. A change in power relationships – in this case giving nature conservation a more equal power position to water management – can therefore open up possibilities to challenge and change boundaries and redefine what activities are possible around the levee (Van Broekhoven Citation2020). Similarly, the prior history of relationships between actors and previously developed trust are likely to influence actors’ boundary actions and their effects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbott, A. 1995. “Things of Boundaries.” Social Research 62 (4): 857–882.

- Blondel, V. D., J.-L. Guillaume, R. Lambiotte, and E. Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008 (10): P10008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

- Boeije, H. R. 2009. Analysis in Qualitative Research. London: SAGE.

- Boons, F., W. Spekkink, and W. Jiao. 2014. “A Process Perspective on Industrial Symbiosis.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 18 (3): 341–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12116.

- Clark, W. C., T. P. Tomich, M. van Noordwijk, N. M. Dickson, D. Catacutan, D. Guston, and E. McNie. 2010. Toward a General Theory of Boundary Work: Insights from the CGIAR’s Natural Resource Management Programs. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP10-035. Cambrdige, MA: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

- Cornwell, B. 2015. Social Sequence Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Degeling, P. 1995. “The Significance of ‘Sectors’ in Calls for Public Health Intersectoralism: An Australian Perspective.” Policy & Politics 23 (4): 289–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557395782200518.

- Derkzen, P., B. B. Bock, and J. S. C. Wiskerke. 2009. “Integrated Rural Policy in Context: A Case Study on the Meaning of ‘Integration’ and the Politics of ‘Sectoring’.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 11 (2): 143–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080902920126.

- Doorn, J. A. A. 1956. Sociologie van de Organisatie: Beschouwingen over Organiseren in Het Bijzonder Gebaseerd Op Een Onderzoek van Het Militaire Systeem. Leiden: Kroese.

- Edelenbos, J., and E.-H. Klijn. 2006. “Managing Stakeholder Involvement in Decision Making: A Comparative Analysis of Six Interactive Processes in The Netherlands.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16 (3): 417–446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui049.

- Enayati, J. 2002. “The Research: Effective Communication and Decision-Making in Diverse Groups.” In Multi-Stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability: Beyond Deadlock and Conflict, edited by Minu Hemmati, Jasmin Enayati, Jan McHarry, and Felix Dodds, 73–95. London: Routledge.

- Epstein, C. F. 1992. “Tinkerbells and Pinups: The Construction and Reconstruction of Gender Boundaries at Work.” In Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and the Making of Inequality, edited by M. Lamont, and M. Fournier, 232–256. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ernst, C., and D. Chrobot-Mason. 2010. “Boundary Spanning Leadership: Six Practices for Solving Problems.” In Driving Innovation, and Transforming Organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Friedman, R. A., and J. Podolny. 1992. “Differentiation of Boundary Spanning Roles: Labor Negotiations and Implications for Role Conflict.” Administrative Science Quarterly 37 (1): 28–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2393532.

- Goodrich, K. A., K. D. Sjostrom, C. Vaughan, L. Nichols, A. Bednarek, and M. C. Lemos. 2020. “Who Are Boundary Spanners and How Can we Support Them in Making Knowledge More Actionable in Sustainability Fields?” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42: 45–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.001.

- Hernes, T. 2004. “Studying Composite Boundaries: A Framework of Analysis.” Human Relations 57 (1): 9–29.

- Hernes, T. 2003. “Enabling and Constraining Properties of Organizational Boundaries.” In Managing Boundaries in Organizations: Multiple Perspectives, 35–55. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hoppe, R. 2010. “From ‘Knowledge Use’ towards ‘Boundary Work’: Sketch of an Emerging New Agenda for Inquiry into Science-Policy Interaction.” In Knowledge Democracy, edited by L. Rowell, 169–186. Berlin: Springer.

- Janssen, S. K. H., J. P. M. van Tatenhove, and H. S. Otter. 2015. “Greening Flood Protection: An Interactive Knowledge Arrangement Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 17(3): 309–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2014.947921.

- Jiao, W., and F. Boons. 2017. “Policy Durability of Circular Economy in China: A Process Analysis of Policy Translation.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 117: 12–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.10.010.

- Johns, C. M. 2019. “Understanding Barriers to Green Infrastructure Policy and Stormwater Management in the City of Toronto: A Shift from Grey to Green or Policy Layering and Conversion?” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (8): 1377–1401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1496072.

- Katz, R., and M. L. Tushman. 1979. “Communication Patterns, Project Performance and Task Characteristics: An Empirical Evaluation and Integration in an R&D Setting.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 23 (2): 139–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(79)90053-9.

- Kerosuo, H. 2006. Boundaries in Action. An Activity-Theoretical Study of Development, Learning and Change in Health Care for Patients with Multiple and Chronic Illnesses. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

- Klerkx, L., N. Aarts, and C. Leeuwis. 2010. “Adaptive Management in Agricultural Innovation Systems: The Interactions between Innovation Networks and Their Environment.” Agricultural Systems 103 (6): 390–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2010.03.012.

- Klerkx, L., S. van Bommel, B. Bos, H. Holster, J. V. Zwartkruis, and N. Aarts. 2012. “Design Process Outputs as Boundary Objects in Agricultural Innovation Projects: Functions and Limitations.” Agricultural Systems 113: 39–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.07.006.

- Lee, L., H. D. Magellan, and C. Ernst. 2014. Boundary Spanning in Action: Tactics for Transforming Today’s Borders into Tomorrow’s Frontiers. Centre for Creative Leadership.

- Long, N. 2001. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Lovell, S. T., and J. R. Taylor. 2013. “Supplying Urban Ecosystem Services through Multifunctional Green Infrastructure in the United States.” Landscape Ecology 28 (8): 1447–1463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-013-9912-y.

- Marshall, N. 2003. “Identity and Difference in Complex Projects: Why Boundaries Still Matter in the ‘Boundaryless’ Organisation.” In Managing Boundaries in Organizations: Multiple Perspectives, edited by N. Paulsen and T. Hernes, 35–55. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mørk, B. E., T. Hoholm, E. Maaninen-Olsson, and M. Aanestad. 2012. “Changing Practice through Boundary Organizing: A Case from Medical R&D.” Human Relations 65 (2): 263–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711429192.

- Noble, G., and R. Jones. 2006. “The Role of Boundary-Spanning Managers in the Establishment of Public-Private Partnerships.” Public Administration 84 (4): 891–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00617.x.

- Paulsen, N., and T. Hernes. 2003. Managing Boundaries in Organizations: Multiple Perspectives. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pettigrew, A. M. 1990. “Longitudinal Field Research on Change: Theory and Practice.” Organization Science 1 (3): 267–292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.3.267.

- Roe, M., and I. Mell. 2013. “Negotiating Value and Priorities: Evaluating the Demands of Green Infrastructure Development.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 56 (5): 650–673. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.693454.

- Sminia, H. 2009. “Process Research in Strategy Formation: Theory, Methodology and Relevance.” International Journal of Management Reviews 11 (1): 97–125.

- Spekkink, W. A. H., and F. A. A. Boons. 2016. “The Emergence of Collaborations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (4): 613–630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv030.

- Sproule-Jones, M. 2002. “Institutional Experiments in the Restoration of the North American Great Lakes Environment.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 35 (4): 835–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423902778463.

- Star, S. L., and J. R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001.

- Swan, J., and S. Newell. 1998. “Making Sense of Technological Innovation: The Political and Social Dynamics of Cognition.” In Managerial and Organizational Cognition: Theory, Methods and Research, edited by C. Eden and J. C. Spender, 108–128. London: Sage.

- Tilly. 2002. Stories, Identities, and Political Change. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Turnhout, T., T. Metze, C. Wyborn, N. Klenk, and E. Louder. 2020. “The Politics of Co-Production: Participation, Power, and Transformation.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42: 15–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009.

- Tushman, M. L., and T. J. Scanlan. 1981. “Boundary Spanning Individuals: Their Role in Information Transfer and Their Antecedents.” The Academy of Management Journal 24 (2): 289–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/255842.

- Van Broekhoven, S. K. 2020. Boundaries in Action: Managing Boundaries in Integrative Land Use Initiatives. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Van Broekhoven, S., and A. Van Buuren. 2020. “Climate Adaptation on the Crossroads of Multiple Boundaries.” European Planning Studies 28 (12): 2368–2389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1722066.

- Van Broekhoven, S., and A. L. Vernay. 2018. “Integrating Functions for a Sustainable Urban System: A Review of Multifunctional Land Use and Circular Urban Metabolism.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1875. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061875.

- van Broekhoven, S., F. Boons, A. van Buuren, and G. Teisman. 2015. “Boundaries in Action: A Framework to Analyse Boundary Actions in Multifunctional Land-Use Developments.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (5): 1005–1023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15605927.

- van Meerkerk, I. 2014. Boundary Spanning in Governance Networks: A Study about the Role of Boundary Spanners and Their Effects on Democratic Throughput Legitimacy and Performance of Governance Networks. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Westerink, J. 2016. Making a Difference: Boundary Management in Spatial Governance. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Williams, P. 2002. “The Competent Boundary Spanner.” Public Administration 80 (1): 103–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00296.

- Wolf, E., and W. Van Dooren. 2017. De waarde van weerstand: Wat Oosterweel ons leert over besluitvorming. Norwich, UK: Pelckmans Pro.

- Yan, A., and M. Louis. 1999. “The Migration of Organizational Functions to the Work Unit Level: Buffering, Spanning, and Bringing up Boundaries.” Human Relations 52 (1): 25–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016968332082.

Appendix A.

Specification sets of boundary actions and rules to establish patterns

Adjustments to sets of boundary actions

We identified sets of boundary actions with the use of an event graph (see methodology). In the event graph we identified network communities, with an algorithm developed by Blondel et al. (Citation2008). Here, network communities (the sets) are identified based on the number of linkages between actions, by identifying which actions are named as antecedents to other actions in the interviews and documents. The sets were validated by presenting them to participants of the workshops. This led to some changes in attribution of actions to sets. In addition, the researchers made some adjustments to the sets. These changes are discussed below.

Case Westduinpark

In Westduinpark two sets of boundary actions are omitted from the analysis because they involve too few events to analyze patterns, and the actions were only limitedly connected to each other and to a coherent boundary discussion.

Case Dakpark

In Dakpark we made three adjustments to the sets: First we joined two sets, because workshop participants emphasized their linkages (set 4). Second, we joined two sets because both evolve around resident participation (set 2), described as one process in documents and interviews, and validated as one process in the workshop. Third, we excluded one set, because it was reviewed as incomplete in the workshop. This is explained by the data collection: (1) it concerns park maintenance, which started when data collection stopped; moreover, (2) the participant stating this was not interviewed (due to 1).

Rules to establish patterns

Several quantitative methods exist for comparative analysis of sequences (Cornwell Citation2015). As we have theoretical templates (the boundary action patterns from literature), the analysis consists of comparing these with each empirical set of boundary actions. We established the following interpretive rules for matching the empirical sequence and event sheets, similar to a logic using INDEL costs (‘costs’ of insertion (IN) or deletion (DEL) of elements, cf. (Abbott Citation1995) (E = empirical sequence, ES = event sheet):

If E = ES, the event sheet is allocated.

If E contains all elements of ES, but has additional actions, we check if this is explained by a parallel event sheet. If not all actions are explained, we used the interviews to assess the importance of additional actions. If they were flagged as crucial, we do not allocate ES.

If E has some, but not all actions of ES, we allocate ES flagging the omission.

If E has the actions of ES, but in a different order, we allocate ES flagging changed order.