Abstract

Due to increasing flood risks, urban planners and water managers are called to enhance urban flood resilience. The implementation of resilience measures requires coordination across levels of government. This study aims to unravel the complexity of implementing spatial strategies to enhance urban flood resilience in the Metropolitan City of Naples. The research is informed by the politicized Institutional Analysis and Development framework, which relates contextual variables, discourses, and institutions (formal\informal rules-in-use) to policy outcomes. This framework is used to explain the outcomes of decision-making in multiple nested action arenas on urban flood risk management policies. It is shown that closed decision-making processes that do not involve lower levels of government, limited monitoring and enforcement, and illegal practices lead to poor coordination across levels of government. This lack of coordination explains why floodplain occupancy continues, thus hampering the shift towards a risk-based approach in flood risk management.

1. Introduction

River floods hit countries worldwide and it is widely accepted that the frequency and magnitude of floods will increase due to climate change (de Moel, van Alphen, and Aerts Citation2009). In recent decades, attempts to reduce flood risks have gained greater importance (Klijn, Samuels, and van Os Citation2008; Kundzewicz et al. Citation2018) owing to the economic and social losses caused by floods (de Moel, van Alphen, and Aerts Citation2009). Flood losses are mostly driven by societal factors such as growing urbanization and floodplain occupancy (EEA (European Environment Agency) Citation2013; Driessen et al. Citation2016; Feyen et al. Citation2012; Hegger et al. Citation2014; Kreibich et al. Citation2015). Flood risk is the result of the probability (hazard) and consequences (vulnerability and exposure) of floods (Klijn, Samuels, and van Os Citation2008; de Moel, van Alphen, and Aerts Citation2009). Flood risk mitigation can thus be achieved by acting on flood probability (hazard reduction), by enhancing the capacity to deal with floods (vulnerability reduction), or by limiting potential flood damages (exposure reduction) (de Moel, van Alphen, and Aerts Citation2009).

Technological advances in flood probability reduction (hazard reduction measures) have enabled the achievement of important security standards. The technical engineering-based perspective dominated flood risk management for a long time. However, flood risk management is no longer viewed as merely a prevention-oriented technical concern, but also a matter of societal transformation, governmental approaches, and spatial development choices (Adger et al. Citation2005; Driessen et al. Citation2016). The risk-based approach emphasizes the connection between water safety and spatial investments (van den Hurk, Mastenbroek, and Meijerink Citation2014) and supports the shift from flood hazard reduction to exposure and vulnerability reduction measures. The integration of spatial policies in the technical domain of flood risk management is yet to be realized in practice. Although spatial measures for flood probability reduction (e.g., water storage reservoirs) are increasingly being implemented, measures related to vulnerability reduction (e.g., adjustments to individual houses) and exposure reduction (e.g., limiting urban development in floodplains) are still barely taken into account. Despite severe flood-induced economic losses and casualties, a risk-based approach is still lacking in Italy, where state and regional funding are mostly geared towards hard flood control infrastructure (Vitale et al. Citation2020; Vitale and Meijerink Citation2021a).

As flood risk is expected to increase in the future, the call for strengthening flood risk governance echoes across Europe (Alexander, Priest, and Mees Citation2016; Jabareen Citation2013; Kundzewicz et al. Citation2018; Driessen et al. Citation2012; Rinne and Nygren Citation2016). Mounting evidence suggests that monocentric forms of governance – with the state as the center of political power and authority (Termeer, Dewulf, and van Lieshout Citation2010; Rhodes Citation1997) – are unable to respond to the uncertainty and complexity of contemporary environmental challenges, which call for cross-sectoral and multi-level coordination (Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern Citation2003; Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt Citation2011; Alexander, Priest, and Mees Citation2016; Newig and Fritsch Citation2009; Ostrom Citation2010; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2012). Decision-making in polycentric multi-level governance systems is distributed in a “nested hierarchy and does not reside at one single level, neither top (only highest-level government enforcing decisions), nor medium (only states/provinces enforce decisions beneficial for their region without considering others), nor individuals with complete freedom to act or being connected in a market structure only” (Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2012, 27). Several tiers of government generally enter the discussions on the design and implementation of management approaches (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn Citation2000; McGinnis Citation1999). This is particularly true for climate adaptation measures, such as water storage reservoirs or flood control infrastructure, the implementation of which necessitate collaborative approaches across sectors and scales (Termeer, Dewulf, and van Lieshout Citation2010). Individual adaptation to climate change ultimately takes place within hierarchical structures constrained by higher/lower institutional settings (Adger et al. Citation2005; Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn Citation2000).

In this study, we aim to gain a better understanding of the interaction between levels of government by studying flood risk management policies in the Sarno River basin (Campania Region, South of Italy) and the role of spatial strategies therein. The main research question is: How do contextual, discursive, and institutional factors promote or hamper the implementation of spatial strategies in flood risk management in the Sarno River basin? To answer this question, we will analyze decision-making on flood risk management strategies in multiple nested action arenas at the catchment, regional, and local levels. By using the politicized Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework by Clement (Citation2010), grounded in Ostrom’s IAD framework (Ostrom Citation2005, Citation2007), we will investigate the contextual, discursive, and institutional factors that may explain the outcomes of decision-making in these nested arenas. The multi-level structure of the IAD framework links the decisions of actors across different institutional layers (Clement Citation2010; Blomquist and De Leon Citation2011). By solely focusing on the macro-level (i.e., the constitutional choice level), we run the risk of overlooking the extent to which constitutional choices affect day-to-day decisions. On the other hand, by focusing solely on the micro-level and what happens on the ground we may overlook (higher level) institutional constraints that shape individual choices (Ostrom Citation2007).

There are several insightful analyses of decision-making in nested action arenas that use the IAD framework (Huntjens, Pahl-Wostl, and Grin Citation2010; Clement Citation2010; Nigussie et al. Citation2018) and a number of applications of the IAD framework for flood risk management (van den Hurk, Mastenbroek, and Meijerink Citation2014; Witting Citation2017). However, very few studies have conducted a multi-level institutional analysis of decision-making in flood risk management (Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013; Witting Citation2017; Dieperink et al. Citation2016). We expect our multi-level institutional analysis to help in understanding the implementation of spatial flood risk management strategies, and the extent to which local spatial planning choices conform to, or deviate from, catchment or regional flood risk policies and why. The specific case from Southern Italy included in our study is particularly interesting as it sheds light on the role of informality in explaining the observed deviations. Only a few papers investigate the role of informality in planning and the extent to which this has hampered flood risk policy implementation (Rahman et al. Citation2014; D’Alisa and Kallis Citation2016; Zanfi Citation2013). Interesting insights are provided by Cole (Citation2014) who attempts to identify the typology of relationships between formal legal rules and the “working rules” of the game (which he uses in place of rules-in-use) by drawing on Ostrom’s IAD framework. Cole’s (Citation2014) work will be partly used in this research to better understand the extent to which informal rules (including illegal practices) are linked to the rules-in-use in flood risk management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical perspectives underpinning this research. Section 3 provides details on the case study selection and the adopted research methodology. Section 4 presents the results of our multi-level institutional analysis of planning practices in the Sarno River basin. In Section 5, we discuss the relevance of contextual, discursive, and institutional factors in enabling or hindering coordination across levels of government, as well as the implementation of spatial flood risk management strategies. Finally, we formulate recommendations on how to improve multi-level decision-making for flood risk management in Italy.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. The politicized IAD framework

Ostrom’s IAD framework contributes to the assessment of the causes of policy implementation gaps, as it links multiple levels of decision-making. These levels are the operational level, where decisions made directly affect resource management and the day-to-day decisions; the collective choice level, where decisions made affect the rules-in-use at the operational level; and the constitutional choice level, where decisions made affect who decides and how decisions are taken in the collective-choice arena (Ostrom Citation2007; Clement Citation2010; Clement and Amezaga Citation2009; Ostrom Citation2005; Cowie and Borrett Citation2005; Ostrom Citation1990). All rules are nested in other sets of rules that define how the first group of rules can be changed. Changes in the rules occur smoothly at the operational level compared to the collective and constitutional levels, where they change at a slower pace (Ostrom Citation2005, Citation2007). The three institutional levels may or may not correspond to administrative levels. “Local communities can operate at the collective-choice or at the constitutional levels when crafting their own rules or deciding on rule-crafting modalities” (Clement Citation2010, 134).

Ostrom (Citation2005, 3) defines institutions as “the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structured interactions”. Rules-in-use are “institutions in their purest form” (van den Hurk, Mastenbroek, and Meijerink Citation2014, 418). Rules-in-use (or working rules) are defined by Ostrom (Citation2007, 36) as “the set of rules to which participants would refer if asked to explain and justify their actions to fellow participants”. Seven types of rules are identified. Position rules specify the roles and positions of participants in an action situation. Boundary rules determine which participant enters or leaves positions and how they do so. Authority (or choice) rules identify the actions that participants can take based on their positions and roles. Aggregation rules determine how decisions are taken (e.g., command, consult, vote, or consensus). Scope rules specify the intended policy outcomes. Information rules refer to the information available to the participants in the action arena (e.g., guidelines). Payoff rules define the costs and benefits of each course of action.

“In a system governed by a ‘rule of law’, the rules-in-form are consistent with the rules-in-use. In a system that is not governed by a ‘rule of law’, there may be central laws and considerable effort made to enforce them, but individuals attempt to evade rather than obey the law” (Ostrom Citation2005, 20). Rules-in-use (or working rules) may or may not be aligned with the contents of rules-in-form (generally expressed in laws, legislation, and regulations). Therefore, the assumption that individuals are only performing actions permitted by the law is a simplification of reality. Breaking the rules is one of the possible courses of action. If the risk of being monitored and sanctioned is low, the predictability and stability of a situation are reduced and instability can increase over time. However, when the probability of being sanctioned is high, people are more likely to stick to the actions that are generally permitted and required (Ostrom Citation2005). Illegal actions highlight how actions taken on the ground may deviate from the model of lawful behavior. Cole (Citation2014) identifies three possible types of relationships between formal legal rules and working rules: (1) the formal legal rule is the working rule, (2) the formal legal rule significantly influences the working rule (and sometimes vice versa), and (3) the formal legal rule bears no apparent relation to the working ruleFootnote1.

Institutions are not the only explanatory factor for decision-making. The IAD framework considers two more variables: physical/material conditions and the attributes of the community. By interacting with biophysical and cultural conditions, institutions create incentives for social behavior. “Physical/material conditions and attributes of the community strongly cohere with rules-in-use in creating institutional settings” (van den Hurk, Mastenbroek, and Meijerink Citation2014, 418). The action arena also affects patterns of interactions, which are associated with the behavior of actors in the action arena, and the outcomes of those interactions (van den Hurk, Mastenbroek, and Meijerink Citation2014).

Clement (Citation2010) argues that one of the limitations of the IAD framework is its lack of consideration of power relationships embedded within the rules-in-use. Therefore, Clement’s (Citation2010) politicized IAD framework includes two more external variables that potentially affect decision-making in the action arena: politico-economic context and discourses. The politico-economic context takes into account how power is distributed among the actors who make decisions and how political and economic interests drive actors’ decisions within a set of rules-in-use (Clement and Amezaga Citation2009). Discourses are concerned with the role of values, beliefs, and norms in shaping the preferences of actors involved in decision-making processes (Hajer Citation1995). Discourse is defined by Hajer (Citation1995, 60) as “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities”. Discourses and institutions are connected. Discourses affect institutions, whereas institutional arrangements and politico-economic contexts foster certain discourses and prevent other discourses from becoming dominant (Clement Citation2010; Clement and Amezaga Citation2009).

The politicized IAD framework does not make claims related to the superiority of institutions, and it contributes to a better understanding of coordination across levels of governments by taking into account the effect of five external variables on the action arenas. By considering the variable of physical/material conditions, we can better understand why the implementation of certain measures that are decided upon at a higher governmental level is unlikely at a lower level (e.g., lack of space may hamper the realization of room for the river projects). A better understanding of the power distribution can help elucidate who takes decisions and the power play between the actors involved. By investigating the attributes of the community and the discourses, we can identify the dominant discourses of resilience to which actors adhere, the measures they propose, and the extent to which these are likely to be implemented by actors that support different discourses. By scrutinizing the rules-in-use, we can better understand which actors gain legitimacy and how they exercise their power.

2.2. Discourses of resilience in flood risk management

Discourses and institutions are intertwined. Certain discourses can strengthen or undermine new or existing institutions and, in return, institutions may reinforce dominant discourses or prevent marginal discourses from becoming dominant. By taking into account the variable of discourses, we can understand why certain policy options have gained predominance over the others (Clement Citation2010). In this study, by looking at the variable of discourses, we analyze the discourses of resilience in flood risk management (Vitale et al. Citation2020).

Resilience is not a straightforward concept and several interpretations of this concept exist. From the literature on resilience, we distinguish between engineering, ecological, and socio-ecological resilience discourses. In flood risk management, the discourse of engineering resilience supports flood probability reduction measures and the “domain of stability” (Holling Citation1996). Starting from the overview of flood risk management strategies provided by Oosterberg, van Drimmelen, and van der Vlist (Citation2005) and Meijerink and Dicke (Citation2008), we link technical measures (e.g., dams, dykes, and spillways) and spatial measures (e.g., water storage reservoirs and multifunctional flood defenses) to the engineering resilience discourse, as these measures aim to prevent floods. Even though these measures were devised to “keep floods away from urban areas”, they may also be considered in the domain of ecological and socio-ecological resilience discourses. They represent a reinterpretation of traditional flood defenses and are designed to accommodate and attenuate floods. Ecological and socio-ecological resilience discourses emphasize the role of measures concerned with the reduction of flood vulnerability and exposure. Vulnerability reduction may be achieved by improving early warning and emergency measures or by adjusting individual houses and infrastructure to “prepare urban areas for floods”; exposure reduction may be attained by preventing urbanization in floodplains or through de-urbanization programmes to “keep urban areas away from floods” (Oosterberg, van Drimmelen, and van der Vlist Citation2005; Meijerink and Dicke Citation2008).

3. Case study selection and research methodology

To answer the main research question, we employed a case study strategy. Over the last century, most urban rivers in the Metropolitan City of Naples (Campania Region, South of Italy) have been channeled into canals, covered, or otherwise confined to make room for urban development and industrialization. The Sarno River is mostly canalized, floods annually, and owns the title of the “most polluted river in Europe” (Manzione Citation2006). The Sarno River basin consists of 60 municipalities, which are split over the provinces of Avellino (8), Salerno (20), and the Metropolitan City of Naples (32) (Autorità di Bacino del Sarno Citation2003), and is now under the jurisdiction of Distretto Idrografico Appennino MeridionaleFootnote2 (here: hydrographical district Authority). The first Sarno River basin plan was adopted in 2002 (Autorità di Bacino del Sarno Citation2003). For the first time, the river basin Authority introduced regulations inhibiting spatial development in very high (R4) and high (R3)Footnote3 flood risk areas.

In this paper, we adopted the politicized IAD framework for its multi-level structure, which contributes to linking the decisions taken by actors across different levels of government. The decomposability of the framework enables understanding of a complex decision-making by breaking it down into several components (Clement Citation2008).

Each variable of our politicized IAD framework was operationalized into a coding scheme, which was used for the qualitative analysis of documents and transcripts of interviews. We used the ATLAS TI software to enhance transparency and facilitate the coding process. Official documents, scientific papers, newspaper articles, newsletters, publicity materials, websites, conference proceedings, and videos were reviewed and analyzed. Furthermore, we conducted 13 semi-structured interviews with governmental and non-governmental actors. Semi-structured interviews were designed to gain a better understanding of decision-making on flood risk management strategies in multiple nested action arenas at the catchment, regional, and local levels. Respondents were selected based on their affiliation and expertise, the level of government to which they belonged (i.e., catchment, regional, and municipal), their geographical location (upstream or downstream position within the Sarno River basin), their goals and tasks, and their stance on flood risk management strategies. Water managers (4), spatial planners (5), NGOs representatives (2), and technical advisors (2) were invited and provided with an interview guide. Confidentially requirements preclude the publication of the respondents’ details. The semi-structured interviews consisted of both role-specific and general questions. With the interviews, we tried to collect additional information on the dominant discourses of resilience, the attributes of the community of actors involved, and the rules of the game.

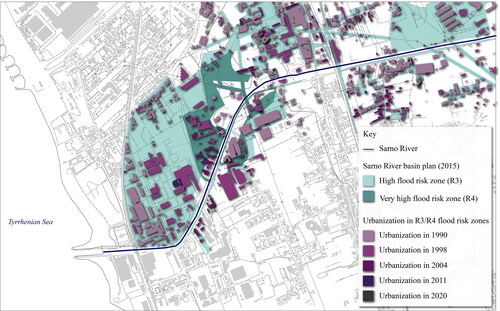

The physical/material conditions and politico-economic context were identified through a secondary analysis of scientific papers and examination of policy documents. For the analysis of discourses, attributes of the community, and the rules-in-use, we coded both written documents and transcripts of interviews. Through the fieldwork (including site visits) and spatial data analysis, we learned more about the actual policy outcomes. We used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to process geographical spatial data on urban development in flood risk areas by overlapping five layers of urbanization – dated in 1990 (cartographic basis), 1998 (prior to the first river basin plan regulations), 2004, 2011, and 2020. The spatial analysis considered the urban development (within a 1 km buffer from the river) in very high (R4) and high (R3) flood risk areas in the 11 municipalities directly crossed by the Sarno River. This spatial analysis enabled us to learn more about the actual outcomes of the decision-making processes in the basin, and helped us identify the extent to which decisions made at the local level conform to decisions made at higher levels.

There is a lack of data concerning informal housing in Italy (Chiodelli Citation2019). For this reason, we could not identify which of the buildings in flood risk areas were illegally built (i.e., built without planning permission). However, regardless of their legality, those buildings are the result of spatial planning choices that are not consistent with the river basin policies.

4. Multi-level institutional analysis

In this section, we present the results of the multi-level institutional analysis performed at the constitutional choice level by examining the river basin and the role of the hydrographical district Authority, at the collective choice level by analyzing the policy implemented at the regional scale, and at the operational choice level by investigating planning practices at the municipal scale. The physical/material conditions and politico-economic context are the same for the three levels of analysis and will be discussed first.

4.1. Physical/material conditions

The Sarno River flows in the shadows of the Vesuvius in the homonymous plain in Campania Region in Southern Italy. After 24 km, it reaches the Gulf of Naples. The Sarno River basin extends for 400 km2 over the provinces of Salerno, Avellino, and the Metropolitan City of Naples. The river and its tributaries are heavily canalized and the water, whose discharge varies between 30 m3/s and 130 m3/s, flows compressed between narrow embankments. In 1998, the Sarno plain was affected by the so-called Tragedia di Sarno, which involved flooding and landslides triggered by exceptional rainfall and the pyroclastic soil composition. The Sarno plain is prone to landslide and flood risks due to the proximity to Vesuvius, which makes it a mudslide-prone area. Since 1950, massive urban sprawl – mostly driven by economic interests – has further exacerbated the plain’s exposure to floods (Legambiente Citation2018). With peaks of 2,000 inhabitants/km2, the urban area along the coast is one of the most densely populated in Europe. In the eleven municipalities crossed by the Sarno River, almost 170,000 people currently live in flood-prone areas, which constitute approximately half of the overall basin population (Trigila et al. Citation2018; Munafò Citation2019).

4.2. Politico-economic context

The Campania Region is among the less developed regions in Europe and is thus eligible for the European Structural FundFootnote4 (Banca d’Italia Citation2019b). The implementation of flood risk management policies in the Sarno River basin has benefited from EU financial support, namely the European Regional Development Fund. The Sarno flooding and pollution issues have been placed on regional and local political agendas now and then, usually during the election period and losing importance afterwards. Illegal organizations, specifically the Camorra (the Campania Italian Mafia), have traditionally been in between local authorities and construction interests (D’Alisa and Kallis Citation2016). In the last twenty years, 27,000 illegal buildings have been reported because of the violation of planning and building regulations in the Sarno plain (Legambiente Citation2018)Footnote5.

The regional poverty rate is higher than the Italian average (Banca d’Italia Citation2019a). However, owing to the abundance of water and the fertility of the land, the Sarno plain is still one of the most productive agricultural districts in the country.

4.3. Constitutional choice level

Flood risk management has historically been a state-centred governance sector in Italy, mostly concerned with hydraulic works for flood protection until the 1950s. Only the dramatic flooding events of Polesine (1951), Amalfi (1954), and Florence (1966) triggered new discussions on the lack of a comprehensive approach to the governance of flood risks (Vitale and Meijerink Citation2021b). These discussions lasted for decades; meanwhile, policies continued to be targeted at post-disaster management and emergency responses (Guadagno Citation2011). In the late 1980s, the first national law on soil protection (Law 183/1989) was finally adopted. The law introduced a catchment-based approach and established the river basin authorities. The former Sarno River basin Authority was established in 1998 (Autorità di Bacino del Sarno Citation2003).

Triggered by the Tragedia di Sarno, the first Sarno River basin plan was adopted in 2002 (Autorità di Bacino del Sarno Citation2003) and was last updated in 2015 (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015c). The Sarno River basin plan considers actions in the short, medium, and long term to mitigate flood risks. Short-term actions are mostly concerned with non-structural measures, such as civil protection plans for emergency measures and disaster relief operations, land use plans, and building adjustments. Actions in the medium and long-term entail structural measures for landslide and flood risk probability reduction (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015c). The hydrographical district Authority considers hazard, vulnerability, and exposure reduction measures as complementary in flood risk management, thus supporting engineering, ecological, and socio-ecological resilience discourses.

As detailed in the overview of the rules-in-use provided in , the hydrographical district Authority is responsible for the river basin management. The river basin plan identifies four flood risk classes: (R1) low risk, (R2) medium risk, (R3) high-risk, and (R4) very high-risk, and three flood hazard classes: (P1) low hazard (flooding return time 200-500 years), (P2) medium hazard (flooding return time 100-200 years), and (P3) high-hazard (flooding return time 20-50 years) (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015d). Urban development is forbidden in very high-risk (R4) and high-risk classes (R3). In medium risk (R2) and low-risk (R1) classes, new buildings are allowed only if they fall in P2 and P1 hazard areas. The hydrographical district Authority also demands civil protection plans (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015b), delocalization programmes for existing buildings in very high-risk (R4), high-risk (R3), and high flood hazard (P3) zones, and the processing of existing unauthorized buildings (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015a). Any new land use or change to the built environment is required to be consistent with the dispositions of the river basin plan (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015a). The hydrographical district Authority ultimately decides on transformations both at the regional and local scales by issuing binding opinions on urban transformations, land use, and civil protection plans (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015b). Guidelines are made available to regional and local authorities to guide them towards spatial development choices that are consistent with the dispositions of the river basin plan.

Table 1. Overview of constitutional, collective, operational rules-in-use in flood risk management in the Sarno River basin.

4.4. Collective choice level

In the 1970s, a gradual process of institutional decentralization began with the progressive empowerment of the regions (Vitale et al. Citation2020). The Campania Region is the authority in charge of designing and implementing regional flood control infrastructure. The Grande Progetto Sarno (GP Sarno)Footnote6, characterized by a dominant focus on hydraulic safety issues and the use of hard control infrastructure, is the latest regional project aimed at flood risk mitigation. At the collective choice level, the dominant engineering resilience discourse is enforced by the presence of a small specialized set of actors, the sectoral approach, the top-down decision-making process, and funds that are primarily geared toward flood probability reduction measures. As stated by one of our interviewees, “the Campania Region does not consider the wide participation of stakeholders and the involvement of the local community as an added value to the decision-making process” (personal communication, 3 May 2020).

The GP Sarno was fostered by the Campania Region, which applied for European financial support during the 2007-2013 EU programming period. The project was considered eligible for funding by the European Commission in 2012 (Regione Campania Citation2012). The GP Sarno was originally designed with a rather narrow scope being exclusively concerned with hydraulic safety issues and flood probability reduction measures. As non-structural measures, the project only required to improve pre-disaster monitoring and provide all the municipalities in the basin with civil protection plans (Regione Campania Citation2012). Starting from 2015, the GP Sarno was widened in its scope. A set of measures to facilitate flood risk mitigation and counter water pollution at the catchment scale were included in a revised version of the project. The Campania Region preserved a leading role, being still entitled to take the main decisions. The approval of the project was made following the majority rule. Organizations and stakeholders were invited to join the conferenza dei servizi, arranged to gather all the stakeholders entitled to issue their opinions. Several interviewees asserted that information sharing was rather limited during the GP design phase to prevent lengthy discussions on the selected measures.

4.5. Operational choice level

Although the Tragedia di Sarno pointed out the vulnerability of urbanization in high-risk areas, changes to land use have been barely implemented at the local scale. In the Sarno River basin, urban development has occurred during recent decades with little concern for hydraulic risks. Introduced in 1985, the condono edilizio (or building amnesty) has further encouraged unauthorized construction. The law was designed “to confer retrospective approval and to upgrade the welter of unauthorised urban construction” ongoing from the 1960s (Zanfi Citation2013, 3430). Its renewals, in 1994 and 2003, prompted waves of unlawful construction. Local authorities have often colluded with criminal organizations (Guadagno Citation2011; De Leo Citation2017), resulting in urban development in high flood risk areas. At the operational choice level, the discourse of engineering resilience dominates. “Local authorities rely on the region and the state as providers of safety through the design and management of flood control infrastructure” (personal communication, 9 January 2020). Spatial strategies for flood vulnerability or exposure reduction are rarely considered, thus hampering the implementation of the hydrographical district Authority prescriptions at the local scale and fostering the discourse of engineering resilience.

The municipalities are responsible for vulnerability and hazard reduction measures, namely warning and disaster management plans and municipal urban plans, which should comply with the regulations provided by the hydrographical district Authority. Although disaster management plans are increasingly being implemented, measures aimed at exposure reduction are rarely taken into account. The municipalities are responsible for processing illegal building practices, which often remain unprocessed by competent municipal departments for political and patronage reasons (Chiodelli Citation2019), illicit dimensions, lack of funds, and lengthy legal procedures. The control exercised by criminal organizations on urban planning practices became apparent when, an authentic copy of the urban plan of the city of Sarno, which was supposed to be confidential, was found in the possession of a Camorra boss when he was arrested in the early 1990s (Legambiente Citation2018). Over time, several anti-mafia investigations have been carried out to unveil the role of criminal organizations in urban development plans in the Sarno plain and, as a consequence, several municipalities have been placed under government commissioners. If local authorities fail to comply with the river basin regulations, the region is entitled to take corrective actions to secure compliance. Sanctions are not always enforced.

4.6. Outcomes

When looking at the outcomes of multi-level decision-making on flood risk management for the Sarno River basin, it should be noted that none of the water storage reservoirsFootnote7 designed by the regional GP Sarno (both former project and later developments) has been realized yet. The implementation phase is currently ongoing and is being entrusted to external companies via bidding processes. The EU can decide to withdraw the funding if there is a delay in the implementation phase or if the initial agreement is not complied with.

In addition, spatial choices made at the local scale often deviated from the indications provided by the hydrographical district Authority in the river basin plan either. The GIS analysis of spatial data provides evidence that new urbanization occurred in the R4 and R3 flood risk zones since 2002, despite river basin regulations (see ).

Figure 1. Layers of urbanization between 1990 and 2020 in very high (R4) and high flood risk zones (R3). Source: elaborated by the authors from regional/hydrographical district Authority spatial data.

The municipalities downstream – namely Pompei, Torre Annunziata, and Castellammare di Stabia – are those most affected by urban development in flood risk areas. Urban development mostly took place before the introduction of the river basin plan in 2002. The highest urbanization rate was registered between 1990 and 1998; in 1998, urban areas increased by 43.6% compared to 1990 (+ 215,744 m2). Urbanization continued at a slower pace between 1998 and 2004, with an overall 18.1% increase in urban areas (+128,273 m2). For the period between 2004 and 2011, a 5.4% increase in urbanization was observed compared to the previous period (+45,082 m2). In 2020, there was no evidence of new urban development in flood risk areas. In summary, the aforementioned data highlight the implementation gap between the risk-based policies of the hydrographical district Authority and regional and local planning practices.

5. Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, by applying the politicized IAD framework, we aimed to obtain insights into the contextual, discursive, and institutional factors that influence decision-making in nested action arenas and explore the implementation of spatial strategies in flood risk management.

Triggered by the Tragedia di Sarno and European policies, the hydrographical district Authority has developed ambitious flood risk policies, which include both engineering solutions and spatial strategies by defining risk classes and formulating restrictions to further spatial development in flood risk zones. This policy approach supports both ecological and socio-ecological resilience rather than engineering resilience only. The hydrographical district Authority encourages the implementation of both structural and non-structural measures in flood risk management, thus supporting the shift towards a risk-based approach. However, when looking at the policy outcomes, the hydrographical district Authority regulations have only been partially implemented at both the collective and operational choice levels. This is explained by the poor coordination across levels of government due to the following factors.

(1) The implementation of strategies to cope with floods is dependent on the physical/material conditions in a river basin. Recent discussions on flood prevention have stressed the importance of restricting city expansion into flood-prone areas, flood-proofing cities, or delocalizing buildings (Oosterberg, van Drimmelen, and van der Vlist Citation2005; Veerbeek et al. Citation2012). The hydrographical district Authority considers the delocalization of buildings in the cluster of possible strategies to reduce the consequences of floods (focusing both on exposure and vulnerability reduction rather than solely on probability reduction measures). However, because of the current number of buildings in R4 and R3 flood risk areas, which were either built without planning permits and are thus illegal or were built before the introduction of the river basin regulations, the delocalization option turns out to be economically unsustainable for local and regional authorities. Regional and local authorities rather support the realization of flood control infrastructure due to the costs and long-term trajectory that floodplain restoration would demand.

(2) A better understanding of the power play between the actors involved in flood risk management may help to explain the poor coordination across the levels of government. As a result of the process of institutional decentralization that started in the 1970s, the Italian regions were gradually entrusted with tasks and competencies in flood risk management. Through the establishment of the river basin authorities as a state-regional organization in 1989, the state attempted to regain some of its former tasks. In contrast to monocentric forms of governance, multi-level governance settings rely on the interplay between different levels of government (or administrative levels) to achieve collective goals. Centralization occurs when policies formulated at a higher level of government are implemented at lower levels in a top-down fashion; decentralization, instead, advocates for multi-level governance arrangements, a polycentric system of actors, and a better combination of top-down and bottom-up instances (Dieperink et al. Citation2016; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013). Multi-level governance “with its focus on activating relevant cross-level interactions, is considered to have more potential to deal with complex multiscale problems” (Termeer, Dewulf, and van Lieshout Citation2010, 6).

In Italy, the institutional decentralization that commenced in the 1970s fostered multi-level institutional settings. However, successful multi-level coordination has been hampered by closed decision-making, which has offered space to criminal power making the formal power either complicit or collusive with it. Illegal housing has been encouraged by both formal (e.g., building amnesties) and informal institutions (e.g., criminal organizations) (Chiodelli Citation2019). As Chiodelli (Citation2019) claims, illegal buildings have often been used by local administrators to respond to residents’ need for housing or as a means of obtaining electoral support. In addition, the decentralization process has often created an unclear allocation of tasks and competencies that are further hindered by the lack of coordination across levels of government. As Ostrom (Citation2005, 21) points out, even in settings where investments are geared towards monitoring the actions of participants, still a “considerable difference between predicted and actual behavior can occur as a result of the lack of congruence between a model of lawful behavior and the illegal actions that individuals frequently take in such situations”. Illegal spatial development in high-risk zones is an indication that formal institutions do not influence informal institutions in some cases. This confirms the importance of the relationship between formal and informal rules. In this case study, it corresponds to the third type of relationship between formal and informal institutions introduced by Cole (Citation2014, 19): “the formal legal rule bears no apparent relation to the working rules”.

(3) When considering the dominant discourses of resilience in flood risk management, although the river basin district Authority promotes spatial flood risk policies at the constitutional choice level – and thus supports vulnerability and exposure reduction measures (ecological and socio-ecological resilience discourses), the region mostly relies on flood probability reduction measures (engineering resilience discourse). At the collective choice level, indeed, flood risk management is conceived as a highly specialized technical field characterized by top-down decision-making and the promotion of engineering solutions. For these reasons, the water storage reservoirs designed by the GP Sarno did not trigger a shift in flood risk management. Both procedural (rather closed decision-making process) and technical features (e.g., sealed mono-purpose water storage reservoirs) are indicators of a dominant engineering resilience discourse. This is further reinforced by local authorities expecting the national and regional governments to prevent flooding. While civil protection services and emergency management plans have been enhanced at the local scale, municipalities do not see the urgency of taking measures oriented to limit exposure and vulnerability to floods (e.g., flood-proofing buildings).

(4) The scientific community agrees on the crucial role of spatial planning in reducing flood risks (Müller Citation2013; Klijn, Samuels, and van Os Citation2008; Warner, van Buuren, and Edelenbos Citation2012; Hartmann and Juepner Citation2017; Howe and White Citation2004; Ran and Nedovic-Budic Citation2016; Neuvel and van den Brink Citation2009). However, spatial measures for flood risk mitigation are barely implemented, as demonstrated by the rather progressive spatial measures prescribed by the hydrographical basin district Authority but that remained unfulfilled in the Sarno River basin. This can be partly explained by the attributes of the community of actors involved. First, the communities of actors involved in water management and spatial planning are rather separated in this case. The community of actors involved in flood risk management is dominated by technical experts (primarily hydraulic engineers) who are not familiar with matters concerning the landscape and the environment (see also Wolsink Citation2006). The community of planners at the regional and local levels neglects the potential of spatial planning in reducing the consequences of floods. They are not inclined to restrict urbanization because of flood risks and rather support the realization of new flood protection infrastructure. This is further supported by national flood managers, whose emphasis is on flood control infrastructure rather than on spatial planning measures, with most of the national funding being geared towards flood probability reduction measures (Vitale et al. Citation2020). The lack of “bridging concepts” to provide common ground for discussion, presented by Dieperink et al. (Citation2016) as one of the key features of successful multi-level interactions, may help explain why coordination across levels of government is hardly in place in the Sarno River basin. As Dieperink et al. (Citation2016) contend, successful coordination of multi-level policies related to urban flood resilience can be achieved only by offering a common ground for discussion, in combination with the presence of policy entrepreneurs, clarity of divisions and tasks, and knowledge and sharing of funding.

(5) The analysis of the rules-in-use across the three nested action arenas shows that local authorities are barely involved in decision-making processes at the collective and constitutional choice levels. This lack of involvement (boundary rules) may explain the lack of support for national policies and it is another indication of poor multi-level governance. In addition, our overview of rules-in-use also reveals that the hydrographical district Authority and the region are formally entitled to control actions taken at the operational choice level by issuing binding opinions (authority rules). Nevertheless, when looking at the spatial outcomes, urbanization has occurred in the basin over the last decades with little concern for both flood risk and the river basin district regulations. This gap between formal and informal institutions is partly explained by the influence of criminal organizations, which have an interest in the development of flood-prone areas, and building and construction work (informal rules). Encouraged by scarce enforcement and poor control (payoff rules), policy outcomes deviate from the policy as intended.

By drawing on Ferry’s (Citation2021) first and second policy coordination mechanisms, we contend that formal “rules-based coordination” (first mechanism) – with higher levels of government prescribing what lower levels have to do (e.g., no longer developing in R3 and R4 flood risk areas) – pursued through formal legislative standards and regulations only, runs the risk of overlooking informal planning practices that still play a role in hampering vertical coordination. “Organizational coordination” (second mechanism) is needed to enhance vertical coordination and “foster the management of a cross-cutting policy problem” (Ferry Citation2021, 5). However, organizational coordination is lacking in our case study, partly due to the closed action arenas and the lack of involvement of actors from lower levels of government in decision-making. Openness and participation in decision-making are crucial not only for systematic deliberation, but also for the improvement of information and social learning (Pahl-Wostl Citation2002) and enhancement of disaster preparedness and risk perception (Miceli, Sotgiu, and Settanni Citation2008). As Pahl-Wostl et al. (Citation2013, 13) contend, the integration of participation into a technocratic management approach “seems to be more threatening to the identity of an expert culture”. This is also proven by the findings of our semi-structured interviews, through which we gained additional information on the involved expertise. Based on the interviews and the policy outcomes, we can conclude that the discourse on engineering resilience is still dominant.

Better coordination across levels of government and actors displaced at each of these levels is also challenging for other European countries (Hegger, Driessen, and Bakker Citation2016). Decentralization usually involves a shift in financial and executive tasks from the state to the local governments, but with the national governments “holding the strings” (Hegger, Driessen, and Bakker Citation2016, 29). In Sweden (Ek et al. Citation2016) and France (Larrue et al. Citation2016), successful bottom-up initiatives have encouraged local engagement and the design of tailor-made solutions in flood risk management; nevertheless, there is still room for enhancing coordination across levels of government. This coordination was rather positively experienced in the Netherlands with the “Room for the River programme” and the “Delta Programme” (van Buuren and Teisman Citation2014) and in Belgium with the river contracts (Mees et al. Citation2016); in both cases, innovative institutional arrangements have encouraged coordination across several levels of government.

Juhola (Citation2016) identifies three multi-level barriers to the implementation of climate change adaptation in land use planning, which are relevant to our study on flood risk management. These are (a) lacking coordination between actors across levels of government, (b) diverging objectives, focus and frames, and (c) lack of effective and coordinated policy instruments. The lack of coordination between actors relates to our findings on a closed action arena, lack of a participatory approach, and the sometimes unclear distribution of tasks and competencies. Diverging objectives, focus, and frames relate to the attributes of the community, discourses of resilience, and the differences between the policy objectives of the hydrographical basin district Authority and local governments. The lack of effective and coordinated policy instruments relates to the use of regulatory instruments to stop floodplain occupancy without providing the necessary financial resources to do so. However, our analysis with the politicized IAD framework points to the importance of two other multi-level barriers that may hinder the implementation of spatial flood risk management strategies: informal planning practices and the power distribution and play between levels of government.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all the interviewees who were willing to share their knowledge on the Sarno River basin and engage in discussions on flood risk management and spatial planning in Italy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 As Cole (Citation2014) contends “[…] among at least some social scientists, the term ‘rules-in-use’ has come to imply that ‘rules-on-paper’ are irrelevant. For that reason, I prefer the label ‘working rules’ which seems a broader term, not necessarily in conflict with either informal norms or formal legal rules”. In this paper, we use rules-in-use as a synonym of working rules.

2 Introduced by the Environmental Code in 2006, the hydrographical district authorities suppressed national, interregional and regional river basin authorities taking over competences, staff, and financial resources. Prior to this reform, the Sarno River basin was under the jurisdiction of Campania Centrale river basin Authority, which included the former Sarno and Campania Nord-Occidentale river basin authorities.

3 The first river basin plan (2002) allowed urban development in high flood risk class (R3) in case of urban development programmes started before the adoption of the river basin plan (this was only allowed in urban development zones, normally identified in the urban plans with the letter B) (Autorità di Bacino del Sarno Citation2002). According to the latest version of the river basin plan, new urban development is prohibited both in R3 and R4 flood risk zones (Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale Citation2015b).

4 The Nomenclature of Territorial Statistical Units (NUTS) divides the European NUTS2 regions into less developed (per capita GDP less than 75% of the EU average), in transition (75%-90%) and more developed regions (over 90%) (Dühr, Colomb, and Nadin Citation2010).

5 The data reported by Legambiente (Citation2018) refer to the fourteen municipalities part of the Agro-Nocerino Sarnese.

6 The original name of the project was Completamento della riqualificazione e recupero del fiume Sarno, Axes 1 – Sostenibilità ambientale ed attrattività culturale e turistica (Regione Campania Citation2012). The Grande Progetto Sarno (here: GP Sarno) was initially part of the so-called European major projects, namely “large-scale investments with a value of more than EUR 50 million each, supported by the EU’s cohesion policy funding” (EC Citation2020). The GP Sarno was financed via European Regional Development Funds and regional funding (Regione Campania Citation2012). Currently, it draws upon the programming periods 2007-2013 and 2014-2020. The budget increased from 217 million euro, during the first phase, to 401 million euro during the second phase. The project is now known as Programma degli interventi di mitigazione del rischio idraulico di interesse regionale afferenti il bacino idrografico del fiume Sarno (Regione Campania Citation2018).

7 In the Natural Water Retention Measures (NWRM) overview, the European Commission (Citation2013) makes a difference between detention and retention basins. Detention and retention basins are infrastructure used for the lamination of water during floods. Detention basins are kept dry if not used during flooding events; retention basins usually contain water (e.g., ponds) throughout the year. In this paper, we will generally refer to them as water storage reservoir/s.

References

- Adger, W. Neil, Terry P. Hughes, Carl Folke, Stephen R. Carpenter, and Johan Rockström. 2005. “Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters.” Science 309 (5737): 1036–1039. doi:10.1126/science.1112122.

- Alexander, M., S. Priest, and H. Mees. 2016. “A Framework for Evaluating Flood Risk Governance.” Environmental Science & Policy 64: 38–47. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.004.

- Autorità di Bacino del Sarno. 2002. Piano Stralcio per L’Assetto Idrogeologico (PAI). Norme Di Attuazione. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Autorità di Bacino del Sarno. 2003. La Rivista Dell’Autorità Di Bacino Del Sarno - Libro Bianco. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale. 2015a. Piano Stralcio per L’Assetto Idrogeologico (PSAI). Allegato A - Compatibilità Idraulica Nelle Aree a Rischio. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale. 2015b. Piano Stralcio per L’Assetto Idrogeologico (PSAI). Norme Di Attuazione. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale. 2015c. Piano Stralcio per L’Assetto Idrogeologico (PSAI). Relazione Generale. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Autorità di Bacino Regionale della Campania Centrale. 2015d. Piano Stralcio per L’assetto Idrogeologico (PSAI). Relazione Idraulica. Naples, Italy: Autorità di Bacino del Sarno.

- Banca D’Italia. 2019a. Economie Regionali. L’economia Delle Regioni Italiane. Dinamiche recenti e aspetti strutturali. Rome, Italy: Banca D’Italia.

- Banca D’Italia. 2019b. Economie Regionali. L’economia Delle Regioni Italiane. Rome, Italy.

- Blomquist, W., and P. De Leon. 2011. “The Design and Promise of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 39 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00402.x.

- Chiodelli, F. 2019. “The Dark Side of Urban Informality in the Global North: Housing Illegality and Organized Crime in Northern Italy.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (3): 497–516. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12745.

- Clement, F. 2008. “A Multi-Level Analysis of Forest Policies in Northern Vietnam: Uplands, People, Institutions and Discourses.” PhD Thesis. Newcastle University Library.

- Clement, F. 2010. “Analysing Decentralised Natural Resource Governance: Proposition for a ‘Politicised’ Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” Policy Sciences 43 (2): 129–156. doi:10.1007/s11077-009-9100-8.

- Clement, F., and J. M. Amezaga. 2009. “Afforestation and Forestry Land Allocation in Northern Vietnam: Analysing the Gap between Policy Intentions and Outcomes.” Land Use Policy 26 (2): 458–470. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.06.003.

- Cole, D. H. 2014. “Formal Institutions and the IAD Framework: Bringing the Law Back In.” SSRN Electronic Journal doi:10.2139/ssrn.2471040.

- Cowie, G. M., and S. R. Borrett. 2005. “Institutional Perspectives on Participation and Information in Water Management.” Environmental Modelling & Software 20 (4): 469–483. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2004.02.006.

- D’Alisa, G., and G. Kallis. 2016. “A Political Ecology of Maladaptation: Insights from a Gramscian Theory of the State.” Global Environmental Change 38: 230–242. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.006.

- Dieperink, C., H. Mees, S. Priest, K. Ek, S. Bruzzone, C. Larue, and P. Matczak. 2016. “Enhancing Urban Flood Resilience as a Multi-Level Governance Challenge: An Exploration of Multilevel Coordination Mechanisms.” In Proceedings of the Nairobi Earth System Governance Conference, 1–26. 7–9 December 2016. Nairobi: KEN.

- Dietz, Thomas, Elinor Ostrom, and Paul C. Stern. 2003. “The Struggle to Govern the Commons.” Science 302 (5652): 1907–1912. doi:10.1126/science.1091015.

- Driessen, P. P. J., C. Dieperink, F. Laerhoven, H. A. C. Runhaar, and W. J. V. Vermeulen. 2012. “Towards a Conceptual Framework for the Study of Shifts in Modes of Environmental Governance: Experiences from The Netherlands.” Environmental Policy and Governance 22 (3): 143–160. doi:10.1002/eet.1580.

- Driessen, P. P. J., D. L. T. Hegger, M. H. N. Bakker, H. F. M. W. Van Rijswick, and Z. W. Kundzewicz. 2016. “Toward More Resilient Flood Risk Governance.” Ecology and Society 21 (4): 53. doi:10.5751/ES-08921-210453.

- Dühr, S., C. Colomb, and V. Nadin. 2010. European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation. European Spatial Planning and Territorial Cooperation. Abingdon: Routledge.

- EC (European Commission). 2013. “Natural Water Retention Measures (NWRM). 53 NWRM Illustrated.” http://nwrm.eu/sites/default/files/documents-docs/53-nwrm-illustrated.pdf.

- EC (European Commission). 2020. “European Commission. Major Projects.” https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/major/.

- EEA (European Environment Agency). 2013. “Flood Risk in Europe: The Long-Term Outlook.” http://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/flood-risk-in-europe-2013.

- Ek, K., S. Goytia, M. Pettersson, and E. Spegel. 2016. Analysing and Evaluating Flood Risk Governance in Sweden. Adaptation to Climate Change? Utrecht: STAR-FLOOD Consortium.

- Ferry, M. 2021. “Pulling Things Together: Regional Policy Coordination Approaches and Drivers in Europe.” Policy and Society 40 (1): 37–57. doi:10.1080/14494035.2021.1934985.

- Feyen, L., R. Dankers, K. Bódis, P. Salamon, and J. I. Barredo. 2012. “Fluvial Flood Risk in Europe in Present and Future Climates.” Climatic Change 112 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0339-7.

- Gibson, C. C., E. Ostrom, and T.K. Ahn. 2000. “The Concept of Scale and the Human Dimensions of Global Change: A Survey.” Ecological Economics 32 (2): 217–239. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00092-0.

- Guadagno, E. 2011. “Il Rischio Idrogeologico, Il Quadro Normativo e La Pianificazione Delle Aree a Rischio: Il Caso Della Regione Campania (Estratto).” Rivista Giuridica Dell’ambiente 5: 699–710.

- Hajer, M. A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Hartmann, T., and R. Juepner. 2017. “The Flood Risk Management Plan between Spatial Planning and Water Engineering.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 10 (2): 143–144. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12101.

- Hegger, D. L. T., P. P. J. Driessen, and M. H. N. Bakker. 2016. A View on More Resilient Flood Risk Governance: Key Conclusions of the STAR-FLOOD Project. Utrecht: STAR-FLOOD Consortium.

- Hegger, D. L. T., P. P. J. Driessen, C. Dieperink, M. Wiering, G. Raadgever, and H. van Rijswick. 2014. “Assessing Stability and Dynamics in Flood Risk Governance.” Water Resources Management 28 (12): 4127–4142. doi:10.1007/s11269-014-0732-x.

- Holling, C. S. 1996. “Engineering Resilience versus Ecological Resilience.” In Engineering within Ecological Constraints, edited by Peter C. Schulze, 31–44. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Howe, J., and I. White. 2004. “Like a Fish out of Water: The Relationship between Planning and Flood Risk Management in the UK.” Planning Practice and Research 19 (4): 415–425. doi:10.1080/0269745052000343244.

- Huntjens, P., C. Pahl-Wostl, and J. Grin. 2010. “Climate Change Adaptation in European River Basins.” Regional Environmental Change 10 (4): 263–284. doi:10.1007/s10113-009-0108-6.

- Hurk, M. van den., E. Mastenbroek, and S. Meijerink. 2014. “Water Safety and Spatial Development: An Institutional Comparison between the United Kingdom and The Netherlands.” Land Use Policy 36: 416–426. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.09.017.

- Jabareen, Y. 2013. “Planning the Resilient City: Concepts and Strategies for Coping with Climate Change and Environmental Risk.” Cities 31: 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.004.

- Juhola, S. 2016. “Barriers to the Implementation of Climate Change Adaptation in Land Use Planning.” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 8 (3): 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-03-2014-0030

- Klijn, F., P. Samuels, and A. van Os. 2008. “Towards Flood Risk Management in the EU: State of Affairs with Examples from Various European Countries.” International Journal of River Basin Management 6 (4): 307–321. doi:10.1080/15715124.2008.9635358.

- Kreibich, H., P. Bubeck, M. van Vliet, and H. De Moel. 2015. “A Review of Damage-Reducing Measures to Manage Fluvial Flood Risks in a Changing Climate.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 20 (6): 967–989. doi:10.1007/s11027-014-9629-5.

- Kundzewicz, Z. W., D. L. T. Hegger, P. Matczak, and P. P. J. Driessen. 2018. “Opinion: Flood-Risk Reduction: Structural Measures and Diverse Strategies.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (49): 12321–12325. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818227115.

- Larrue, C., S. Bruzzone, L. Lévy, M. Gralepois, T. Schellenberger, J. Trémorin, M. Fournier, C. Manson, and T. Thuilier. 2016. Analysing and Evaluating Flood Risk Governance in France. From State Policy to Local Strategies. Tours, FR: STAR-FLOOD Consortium.

- Legambiente. 2018. “Fango. Il Modello Sarno Vent’anni Dopo.” Rome.

- Leo, D. De. 2017. “Urban Planning and Criminal Powers: Theoretical and Practical Implications.” Cities 60: 216–220. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.002.

- Manzione, R. 2006. Commissione parlamentare d’inchiesta sulle cause dell’inquinamento del Fiume Sarno. Rome: Parlamento della Repubblica Italiana.

- McGinnis, M. 1999. Polycentricity and Local Public Economies: Readings from the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. Michigan, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Mees, H., C. Suykens, J-C. Beyers, A. Crabbé, B. Delvaux, and K. Deketelaere. 2016. Analysing and Evaluating Flood Risk Governance in Belgium. Dealing with Flood Risks in an Urbanised and Institutionally Complex Country. Leuven: STAR-FLOOD Consortium.

- Meijerink, S., and W. Dicke. 2008. “Shifts in the Public–Private Divide in Flood Management.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 24 (4): 499–512. doi:10.1080/07900620801921363.

- Miceli, R., I. Sotgiu, and M. Settanni. 2008. “Disaster Preparedness and Perception of Flood Risk: A Study in an Alpine Valley in Italy.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 28 (2): 164–173. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.006.

- Moel, H. de., J. van Alphen, and J. C. J. H. Aerts. 2009. “Flood Maps in Europe: Methods, Availability and Use.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 9 (2): 289–301. doi:10.5194/nhess-9-289-2009.

- Müller, U. 2013. “Implementation of the Flood Risk Management Directive in Selected European Countries.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 4 (3): 115–125. doi:10.1007/s13753-013-0013-y.

- Munafò, M. 2019. “Consumo Di Suolo, Dinamiche Territoriali e Servizi Ecosistemici.” Vol. Report SNP. https://www.snpambiente.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Rapporto_consumo_di_suolo_20190917-1.pdf.

- Neuvel, J. M. M., and A. van den Brink. 2009. “Flood Risk Management in Dutch Local Spatial Planning Practices.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 52 (7): 865–880. doi:10.1080/09640560903180909.

- Newig, J., and O. Fritsch. 2009. “Environmental Governance: Participatory, Multi-Level - And Effective?” Environmental Policy and Governance 19 (3): 197–214. doi:10.1002/eet.509.

- Nigussie, Z., A. Tsunekawa, N. Haregeweyn, E. Adgo, L. Cochrane, A. Floquet, and S. Abele. 2018. “Applying Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development Framework to Soil and Water Conservation Activities in North-Western Ethiopia.” Land Use Policy 71: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.039.

- Oosterberg, W., C. van Drimmelen, and M. van der Vlist. 2005. “Strategies to Harmonize Urbanization and Flood Risk Management in Deltas.” In Proceedings of the 45th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: Land Use and Water Management in a Sustainable Network Society, 1–31, Amsterdam, NL.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2007. “Institutional Rational Choice. An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 2nd ed., 21–64. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Ostrom, E. 2010. “Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change.” Global Environmental Change 20 (4): 550–557. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. 2002. “Towards Sustainability in the Water Sector: The Importance of Human Actors and Processes of Social Learning.” Aquatic Sciences 64 (4): 394–411. doi:10.1007/PL00012594.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., G. Becker, C. Knieper, and J. Sendzimir. 2013. “How Multilevel Societal Learning Processes Facilitate Transformative Change: A Comparative Case Study Analysis on Flood Management.” Ecology and Society 18 (4): 58. doi:10.5751/ES-05779-180458.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., L. Lebel, C. Knieper, and E. Nikitina. 2012. “From Applying Panaceas to Mastering Complexity: Toward Adaptive Water Governance in River Basins.” Environmental Science & Policy 23: 24–34. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.07.014.

- Rahman, H. M. T., S. K. Sarker, G. M. Hickey, M. M. Haque, and N. Das. 2014. “Informal Institutional Responses to Government Interventions: Lessons from Madhupur National Park, Bangladesh.” Environmental Management 54 (5): 1175–1189. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0325-8.

- Ran, J., and Z. Nedovic-Budic. 2016. “Integrating Spatial Planning and Flood Risk Management: A New Conceptual Framework for the Spatially Integrated Policy Infrastructure.” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 57: 68–79. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.01.008.

- Regione Campania. 2012. Delibera Della Giunta Regionale n. 119 Del 20/03/2012. Oggetto Dell’Atto: Grande Progetto Completamento Della Riqualificazione e Recupero Del Fiume Sarno.

- Regione Campania. 2018. Delibera Della Giunta Regionale n. 144 Del 13/03/2018. Oggetto Dell’Atto: Programma Degli Interventi Di Mitigazione Del Rischio Idraulico Di Interesse Regionale Afferenti Il Bacino Idrografico Del Fiume Sarno.

- Renn, O., A. Klinke, and M. van Asselt. 2011. “Coping with Complexity, Uncertainty and Ambiguity in Risk Governance: A Synthesis.” Ambio 40 (2): 231–246. doi:10.1007/s13280-010-0134-0.

- Rhodes, R.A.W. 1997. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Rinne, P., and A. Nygren. 2016. “From Resistance to Resilience: Media Discourses on Urban Flood Governance in Mexico.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (1): 4–26. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1021414.

- Termeer, C. J. A. M., A. Dewulf, and M. van Lieshout. 2010. “Disentangling Scale Approaches in Governance Research: Comparing Monocentric, Multilevel, and Adaptive Governance.” Ecology and Society 15 (4): 29. doi:10.5751/ES-03798-150429.

- Trigila, A., C. Iadanza, M. Bussettini, and B. Lastoria. 2018. Dissesto Idrogeologico in Italia: Pericolosità e Indicatori Di Rischio. Edizione 2018. Rome: ISPRA.

- van Buuren, A., and G. R. Teisman. 2014. “Samen Verder Werken Aan de Delta.” In De Governance Van Het Nationaal Deltaprogramma Na, 2014, Rotterdam, NL

- Veerbeek, W., R. M. Ashley, C. Zevenbergen, J. Rijke, and B. Gersonius. 2012. “Building Adaptive Capacity for Flood Proofing in Urban Areas through Synergistic Interventions.” In WSUD 2012 - 7th International Conference on Water Sensitive Urban Design: Building the Water Sensitive Community, Final Program and Abstract Book.

- Vitale, C., and S, Meijerink. 2021a. “Flood Risk Policies in Italy: A Longitudinal Institutional Analysis of Continuity and Change.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 1–25. doi:10.1080/07900627.2021.1985972.

- Vitale, C., and S. Meijerink. 2021b. “Understanding Inter-Municipal Conflict and Cooperation on Flood Risk Policies for the Metropolitan City of Milan.” Water Alternatives 14 (2): 597–618.

- Vitale, C., S. Meijerink, F. D. Moccia, and P. Ache. 2020. “Urban Flood Resilience: A Discursive-Institutional Analysis of Planning Practices in the Metropolitan City of Milan.” Land Use Policy 95: 104575. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104575.

- Warner, J. F., A. van Buuren, and J. Edelenbos. 2012. “Making Space for the River.” In Governance Experiences with Multifunctional River Flood Management in the US and Europe. London: IWA Publishing.

- Witting, A. 2017. “Ruling out Learning and Change? Lessons from Urban Flood Mitigation.” Policy and Society 36 (2): 251–269. doi:10.1080/14494035.2017.1322772.

- Wolsink, M. 2006. “River Basin Approach and Integrated Water Management: Governance Pitfalls for the Dutch Space-Water-Adjustment Management Principle.” Geoforum 37 (4): 473–487. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.07.001.

- Zanfi, F. 2013. “The Città Abusiva in Contemporary Southern Italy: Illegal Building and Prospects for Change.” Urban Studies 50 (16): 3428–3445. doi:10.1177/0042098013484542.