Abstract

In 2020, the pandemic impacted the social and economic dynamics of cities around the world. Entertainment districts hosting events, festivals, and other cultural activities were particularly affected, as their loss of attractiveness also impacted their livability. Reflecting on how the experience of the sonic environment contributes to attractiveness and livability in an urban environment, we propose a sonic perspective to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Montreal’s entertainment district – Quartier des Spectacles (QDS). Through semi-structured interviews, we focus on how the sonic experience of QDS’s residents changed throughout 2020, and on how their experiences can provide valuable insight into addressing the district’s future planning and management. Looking at QDS as a case study to orient the post-pandemic trajectories of entertainment districts, we present a number of sound-related governance recommendations aimed at strengthening QDS residents’ involvement in the neighborhood’s cultural, artistic, and political life and its decision-making processes.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly impacted the social and economic dynamics of metropolitan areas around the world. Effects were observed on the economic geography of urban systems at a large scale, as well as at a smaller scale, on the structure, demography, and social workings of urban neighborhoods (Florida, Rodríguez-Pose, and Storper Citation2021). The entertainment and tourism sectors were most affected by the lockdowns, restrictions and strict social distancing rules that led to a freezing of events and a dramatic decrease in visitors, and, in many cases, a general decrease in urban attractivenessFootnote1 for visitors and residents. The unprecedented impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and entertainment sectors (Nhamo, Dube, and Chikodzi Citation2020; for a review see Kowalczyk-Anioł, Grochowicz, and Pawlusiński [Citation2021]) has undermined the attractiveness of touristic and cultural destinations (Abbas et al. Citation2021), that were previously driven by the growing processes of touristification (Sequera and Nofre Citation2018) – and has also affected the livability of those districts, stalling their economies and suspending everyday activities in the public realm.

While perspectives for post-pandemic recovery have been outlined elsewhere (McCartney, Pinto, and Liu Citation2021), further research is needed to (re)define what makes entertainment districts both attractive and livable in the current pandemic, as well as for the future post-pandemic contexts. As the pandemic has shown, such districts are less resilient to impactful events (such as COVID-19) especially when the attractiveness geared toward visitors is not balanced by a sense of livability among residents. This is particularly interesting from a sonic perspective, given the critical role that sound (and its negative counterpart – noise) plays in urban life, urban dynamics and urban cohabitation (Ren, Tang, and Cai Citation2022), and given the challenge related to the planning and management of the sonic environment (Brown and Muhar Citation2004; Kang and Schulte-Fortkamp Citation2017).

While many COVID-19 studies reported decreased sound pressure levels during the pandemic in different urban contexts (for a review see Steele and Guastavino [Citation2021]), the in-depth effects of such transformations on residents’ experiences, to our knowledge, have so far remained underexplored. Focusing on the role of sound in the attractiveness of urban areas and aiming to encourage a direct engagement of residents in shaping future post-pandemic recovery strategies, we propose a sonic approach to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the residents of Montreal’s entertainment district: Quartier des Spectacles (QDS). We use QDS as an example to illustrate how the unprecedented 2020 sonic experience has transformed the ‘image’ of an entertainment and cultural destination, affecting also its livability and potentially limiting its future attractiveness.

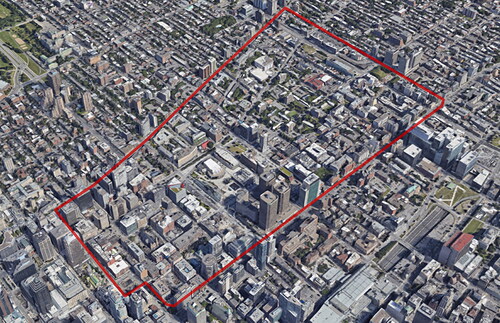

Located in downtown Montreal, QDS is a neighborhood undergoing constant transformation, where large public spaces and numerous entertainment venues alternate with dense new residential developments, a social housing complex, and older housing units ( and ). It is internationally known for hosting “North America’s most concentrated and diverse group of cultural venues as well as numerous festivals and events” (Quartier des Spectacles Montréal Citation2021). The uniqueness of the mixed-use profile neighborhood and the unusually long duration of its festival season – in pre-COVID-19 times, canceled or moved online for 2020, makes QDS a remarkable case to study how the experienced sonic environment of an entertainment neighborhood – and its public image – changed during the pandemic.

Figure 2. Place des Arts, one of the main public spaces of QDS, during a typical festival season (on the left) and during the 2020 lockdown (on the right). Photo credits: Nicola Di Croce (left), Catherine Guastavino (right).

We thus aim to answer the following research questions: (i) how did the pandemic affect the sonic environment of QDS? (ii) how did it impact the district’s perceived attractiveness and livability? and (iii) what lessons can we learn from the pandemic sonic experiences of QDS residents to inform the district’s future environmental planning and management strategies?

The article is organized as follows: we start with a threefold literature review where we focus on attractiveness and livability within entertainment districts, the effects of COVID-19 on urban sonic environments and detail the QDS context. We then describe the methods and main findings from interviews with QDS residents on their indoor and outdoor sonic experiences in 2020. We conclude by proposing recommendations related to festival management, nightlife policy, and broader urban sound planning strategies for QDS, where the case study is discussed as a model for understanding the post-pandemic future of cultural neighborhoods.

2. Literature review

2.1. Attractiveness and livability of entertainment districts before and during the pandemic

Over the past decades, tourism, culture, leisure, and entertainment have become the main strategic points used to foster the revitalization of degraded urban areas and city centers worldwide as part of ‘touristification’ efforts (Sequera and Nofre Citation2018, 843–844). However, with a new focus on the growing number of tourists and visitors, cities were faced with the new challenge of the negative impacts of touristification on urban livability. As remarked by Cocola-Gant (Citation2018), touristification challenges the balance between urban attractiveness (oriented mainly toward both visitors and, to a far lesser extent, to residents) and livability (oriented toward locals) in contemporary post-industrial cities.

Romão et al. (Citation2018) investigated urban attractiveness for residents and visitors and its impact on livability in 40 different cities worldwide, highlighting the difficulty of striking a balance between city growth and livability (often measured through e.g. price of rent, working conditions, unemployment rates, or perceptions of safety). Their study indicates that attractiveness and livability are not necessarily incompatible, especially within cultural neighborhoods, as “[c]ultural dynamics appears to be a major determinant for attracting new residents and supporting a strong international tourism industry” (67). Moreover, while the presence of creative activities in urban areas has been shown to positively affect urban economies (Arribas-Bel, Kourtit, and Nijkamp Citation2016), many studies have highlighted the need to consider social conflicts arising from population dynamics (Sassen Citation2010; Colomb and Navy Citation2017). This is especially relevant when the economic benefits arising from the growing number of visitors are not equally re-allocated to local populations (WTO [World Tourism Organization] Citation2012).

Understanding urban attractiveness and livability – especially within entertainment districts – requires close attention to both the ‘body and soul’ of the city (Kourtit, Nijkamp, and Wahlström Citation2021). A city’s ‘body’ (the visible built environment) and ‘soul’ (the socio-cultural, lived component) are of equal importance in the formation of residents and city users’ appreciation of a given urban area, which opens up avenues for interdisciplinary studies to experiment with participatory design approaches (Xiao, Lavia, and Kang Citation2018). In this context, the sonic dimension of the urban experience is of particular interest given that noise is often at the center of many of the aforementioned conflicts and also an essential component of the ‘soul’ of the city. Taking this sonic angle, the notions of attractiveness and livability recall the concept of “soundscape vibrancy” (Aletta and Kang Citation2018) that has been proposed in soundscape literature – which broadly researches the sonic environment as perceived by people, in context (ISO [International Organization for Standardization] Citation2014). As soundscape vibrancy has been related to social activity and human presence, in this article the critical role of human activities in shaping soundscapes is extremely relevant when considering how public space uses have been affected by lockdowns (Mitchell et al. Citation2021), which, in turn, had consequences on how cities and particularly entertainment districts were experienced.

Recent studies investigate place attachment, place identity, and residents’ satisfaction (Casakin, Hernandez, and Ruiz Citation2015; Devine-Wright Citation2013; Zenker and Rütter Citation2014) in the context of touristification efforts. These are an interesting background against which to situate the documentation of more recent, yet urgent, impacts of the pandemic on touristic, cultural and entertainment neighborhoods – from the perspective of residents of such neighborhoods. Studies have started to report on the impact of the first year of COVID-19 on tourism (UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development) Citation2021; Nhamo, Dube, and Chikodzi Citation2020; Kowalczyk-Anioł, Grochowicz, and Pawlusiński Citation2021). Abbas et al. (Citation2021, 1) state that “[the] tourism and leisure industry has faced the COVID-19 tourism impacts hardest-hit and lies among the most damaged global industries”, with unavoidable consequences on urban areas devoted to cultural, leisure and entertainment activities. Anecdotal evidence in the media and first-person accounts (Ducas Citation2020) indicate that the pandemic radically transformed touristic and entertainment areas, contributing to a quiet, yet uncanny, daily life, upending the experience of previously crowded and vibrant urban spots. Yet, to our knowledge, no study has investigated the effects of the pandemic with a focus on residents in entertainment neighborhoods, and particularly focusing on the sonic dimension of their everyday environments.

2.2. Effects of COVID-19 on urban sonic environments

The transformation of the experienced sonic environment during the pandemic fostered a new interest in everyday urban sounds among the general public (Bui and Badger Citation2020), as well as a wide variety of research fields including biology and ecology (Derryberry et al. Citation2020). Several studies indicate that the interruption of human activities and the reduction in road and air traffic during the first lockdown (spring 2020) led to a significant decrease in measured sound pressure levels in major cities (Basu et al. Citation2021; Munoz et al. Citation2020). While many studies focused on traffic noise reduction (Pagès et al. Citation2020; Asensio, Pavón, and de Arcas Citation2020; Vogiatzis et al. Citation2020), others analyzed the soundscape and showed an increase in the presence or audibility of pleasant human sounds in the public space (e.g. voices or footsteps) due to the significant drop in mechanical sounds and other unpleasant sound sources (Lenzi, Sadaba, and Lindborg Citation2021).

Despite this finding, during the first lockdown, two studies in London showed that while the outdoor noise levels were perceived as lower, the other sounds were not all perceived as pleasant, as noise complaints due to noise from neighbors went up significantly (Lee and Jeong Citation2021; Tong et al. Citation2021). Given the increased amount of time people were required to spend indoors and the fact that the home had to also accommodate leisure, work and study activities (often with others within the same space), a special consideration has been paid to sonic environments inside the home, both during the lockdown and throughout the pandemic. Torresin et al. (Citation2021) showed that dwellers stated that they could better control and alter their (indoors) sonic environment when performing leisure activities than when working. The lockdown has, thus, reignited previous conversations on the sonic quality of dwellings (Smith and Pijanowski Citation2014, 65) in which all of the everyday activities of household members now had to take place, as well as on the notion of “acoustic comfort” as related to people’s age and other individual factors such as education and gender (Ren, Tang, and Cai Citation2022).

In this context, only a handful of studies investigated the soundscape transformations during the pandemic within touristic areas. The focus was rather on acoustic measurements; Manzano et al. (Citation2021) observed a strong decrease in environmental noise levels compared to 2019 in four touristic sites in Granada (Spain). The authors commented on the dramatic loss of unique sonic character that had been associated with the places. Results from London (Aletta et al. Citation2020) also confirm that, among 11 different locations studied, those that were major tourist destinations had the highest reduction in environmental noise levels.

Specifically for Montreal – and in QDS itself – Steele and Guastavino (Citation2021) analyzed the sound levels of the district by comparing the pre-pandemic situation (of 2019 and winter 2020) with the spring and summer periods of 2020. There was a moderate drop in sound levels in 2020 due to the absence of visitors in the neighborhood, compared to a period in 2019 when no festivals and events took place, observable especially during nighttime (see also Ducas [Citation2020]). But background sound levels, despite a documented drop in traffic, did not decrease as expected, likely due to the HVAC systems from larger buildings in the area (museums, concert halls, hotels, shopping malls and large residencies) as well as construction work, which was suspended only for a short window during spring 2020. In summary, despite the absence of cultural events, the background noise levels in QDS during lockdown and over the summer of 2020 were still quite high, raising questions about the impact of mechanical and construction noise on the neighborhood’s livability, and on its attractiveness, especially for new potential residents.

2.3. Montreal’s Quartier des Spectacles before the pandemic

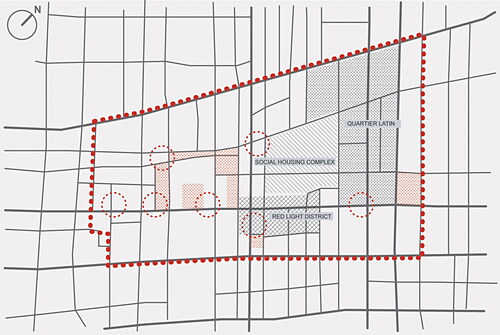

The Quartier des Spectacles Partnership (PQDS) was established in 2002 by the City of Montreal, together with a group of stakeholders, cultural organizations and private developers in downtown Montreal (within the administrative borough of Ville-Marie). This non-profit organization aims to consolidate the majority of Montreal’s cultural and entertainment events within a 1 km2 area, including the old city’s Red-Light district, the bustling student neighborhood of the Quartier Latin,and the Jeanne-Mance social housing complex (see ). From 2007 onwards, the district underwent massive renovations, with new housing projects added, and now includes 8 large public spaces hosting over 40 festivals and events every yearFootnote2.

Figure 3. Schematic visualization of the QDS area. Official margins of the area are marked with a red dotted line, the main public spaces are marked with red horizontal hashes, and the main entertainment buildings and features are marked with red dotted circles. Colour online.

Through the establishment of QDS, the PQDS intended to attract new investors, cultural organizations, and residents, thus helping position Montreal as an international destination for entertainment, culture and tourism (Barrette Citation2018). Following this new approach, in the last decade, QDS helped attract a growing number of visitors to Montreal, as the city started to experience the first symptoms of tourism overcrowding – or overtourism (Khomsi, Fernandez-Aubin, and Rabier Citation2020), an issue considered as increasingly problematic for many destinations worldwide. Within this touristification trend, while researchers have investigated the attractiveness of QDS, particularly taking into account the successful governance of the PQDS (Darchen and Tremblay Citation2013), others have concentrated on the livability of QDS, especially from the perspective of its residents (for a review, see Bild, Steele, and Guastavino [Citation2021]).

The experience of living in an entertainment district like QDS has also been investigated by Bélanger and Cameron (Citation2016), who studied the impact of the redevelopment projects on its residents. While acknowledging that QDS has created “a distinct and identifiable atmosphere of spectacle” (Cameron and Bélangerr Citation2012, 359), the authors reveal how residents’ “home territories” (considered as the set of everyday experiences within and around their homes) are profoundly affected by the ‘spectacularization’ of the public space (see also Margier and Ethier [Citation2021]). Especially from the perspective of long-time residents, Bélanger and Cameron reported how QDS’s home territories are endangered by the territory of spectacle i.e. how the neighborhood’s livability is threatened by the entertainment environment ().

Figure 4. Place des Arts during the festival season. Photo credits: Caribb, uploaded on Flickr website under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The experience of living in QDS was further investigated by Bild, Steele, and Guastavino (Citation2021), who paid special attention to the indoor and outdoor sonic environment, as perceived by residents during the festival season of 2019. The study revealed that not only younger, but, more interestingly and perhaps unexpectedly, older generations, were and still are attracted to move to QDS in order to live close to the festivals, which proved to be key connecting factors between residents and the neighborhood. The study also showed that, while according to many residents, sound levels and the general management of festivals have improved in recent years, complaints were rather directed toward night life and night noise more broadly as well as the new (expensive) housing developments under construction in the area. Finally, the research refers to the comparative absence of other day to day activities when festivals are not happening, which for some respondents contributed to a quiet and almost uneventful experienced environment, raising further questions on urban comfort and livability for residents.

Building on this complex background of a touristified neighborhood hosting an almost yearlong season of festivals and events, we focus on the exceptional change produced by the pandemic on the everyday life of an entertainment district by investigating the urban sonic environment as perceived by QDS residents over 2020. The focus on the sonic dimension, as it relates to attractiveness and the ‘image’ of a neighborhood, represents a promising, yet underdeveloped, way to unpack the effects of the pandemic on neighborhoods hit by the restrictions and an absence of cultural and leisure events.

3. Methodology

We conducted an interview study to understand the effects of the pandemic on the indoor and outdoor experiences of QDS residents during the spring and summer of 2020. Below we describe the timeline of the COVID-19 restrictions in place in Montreal (with an emphasis on decisions pertinent to cultural and social life) – and the research protocol.

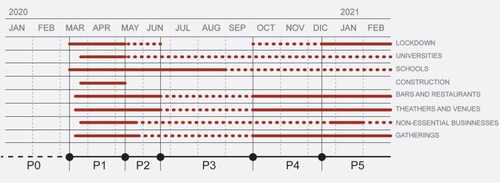

Figure 5. Visualization of the main activities affected by “closure” and "partial reopening” measures, divided by periods (P0 to P5). For each activity the red line corresponds to “closure”, while the red-dotted line corresponds to “partial reopening”. Colour online.

3.1. Timeline

The interviews were conducted between November and December 2020, following weeks of increasing second-wave restrictions and just a few weeks before the second lockdown. We provide a timeline and a description of each period considered for this study in and an overview of the main measures taken against COVID-19 in . In QDS, most of the large festivals and events usually take place during late spring, summer and early fall; there are many other activities organized during the colder season, but Montreal’s rough winter conditions considerably limit the number of outdoor activities offered. Within this framework, restrictions in Montreal started in the second week of March 2020, and immediately hit large indoor gatherings, cinemas, theaters, and museums – all core activities of QDS (see Rowe Citation2020). Restrictions were then eased in May 2020 as outdoor gatherings were allowed in public spaces, but large events and big festivals remained canceled, with only small-scale events permitted. New restrictions were introduced in October 2020, as Quebec was expecting a second wave and Montreal was declared a red-alert zone (December 2020).

Table 1. COVID-19 timeline in Montreal (March 2020 - March 2021).

Interviewees were asked to talk about their experience for the March – November 2020 period, that included the First wave Lockdown (P1) and the spring (P2), summer (P3) and fall (P4), when new restrictions for the second wave were introduced. Interviewees were also invited to reflect and compare their pandemic (sonic) experience with the pre-pandemic situation.

3.2. Data collection

Building on our ongoing collaboration with PQDS, we invited residents living within or around the borders of the entertainment neighborhood to participate in online interviews. The choice to also include people living around the immediate administrative boundaries of the neighborhood was intentional; other studies have suggested that the experience of living in an entertainment district like QDS (Bélanger and Cameron Citation2016) – and particularly when it comes to the sonic experience (Bild, Steele, and Guastavino Citation2021) – is not restricted to its pre-defined physical boundaries but is also shared by those from surrounding areas. Covering the spring, summer and fall of 2020 allowed us to address both the lockdown period, when residents spent most of their time indoors, as well as the summer period, which saw an easing of restrictions and thus allowed for a documentation of the outdoor sonic experience, but without the usual planned events and activities. The invitation was posted in English and in French on the research team’s official website and circulated on the mailing list of PQDS as well as other organizations active in the neighborhood. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the interviews were conducted online; they lasted around 90 minutes, were video recorded with the permission of the participant and later transcribed in full for analysis. Participants were previously informed via email about the broader topics of the discussion and were invited to sign a consent form prior to the interview.

Seven interviewees were recruited: three francophones and four anglophones, four men and three women, four under 40 years of age and three over 40. While the number of participants was limited due to the difficulties in conducting research during the pandemic; the selected participants covered a diverse range of ages and social groups, thus representing diverse perspectives of QDS residents’ sonic experiences throughout 2020. Exploratory in nature, the qualitative study aimed to initiate an in-depth investigation of an unprecedented situation (about which no research was previously available), and to inform approaches for further studies at a larger scale.

The interview guide included topics from the ISO soundscape standards (ISO Citation2016, 20–24), adapted to the pandemic context, for example, inviting participants to compare their sonic experience before and during the pandemic.

The interview was semi-structured and divided into three parts (see interview guide in Appendix – online supplementary material):

Demographics and general neighborhood information, focusing on the global experience of the neighborhood during the spring, summer and fall of 2020. This part included the overall perception of the neighborhood (including who it was for, or what it sounded like in general), their overall experience with the pandemic and the changes brought to their way of life.

The sonic environment as experienced indoors, including the use of indoor spaces and differences indoors or in sounds compared to the pre-pandemic period. This part sought to examine the everyday activities affected by “noise”, the major sources of annoyance, their attitude toward filing noise complaints, and their strategies for coping with noise.

The outdoor sonic environment and the overall experience of public spaces throughout 2020, again as compared to past years. This last part explored outdoor activities, with special attention to those affected by particular sounds or “noises”, the outdoor sources of annoyance, as well as those considered as “positive” or “missing” within the everyday environment.

3.3. Data analysis

The transcribed corpus was coded according to the topics covered in the three sections structuring the interview. We identified emerging themes within each section using the constant comparison method (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967), referring to sound considerations as well as topics more indirectly related to sound, such as the indoor and outdoor space use in relation to the sonic environment during the pandemic.

This inductive process resulted in a coding scheme where we identified 18 emerging themes (further formulated as distinct statements), and afterwards grouped into eight broader topics (see in the next section for details). Emerging themes and topics were then aggregated into four macro themes: (I) the neighborhood’s livability and attractiveness; (II) residents’ indoor everyday sonic experiences; (III) QDS’s identity factors; and (IV) residents’ outdoor everyday sonic experiences. These four macro themes were the basis for formulating recommendations addressing the post-pandemic recovery and future of QDS.

Table 2. Schematic representation of the framework emerging from the interviews.

Special attention was paid to the relationship between livability and attractiveness in the context of the transformations caused by the pandemic in QDS. The concepts of attractiveness and livability were operationalized following Romão et al. (Citation2018): urban attractiveness describes public space’s uses of both residents and local or international visitors, while livability included aspects related to the general impression of the living environment, the presence of services, the cost of living, and the perceived level of safety.

Below, we structure and report on our findings according to the four macro-themes. For ease of reading, we use a format of ‘I x’ to refer to interviewees, where x is the assigned interviewee ID. For the sake of clarity, all quotations are in italics, and are presented in English in the text, with original versions in French as footnotes, when applicable.

4. Findings

4.1. QDS’s loss of attractiveness and livability during the pandemic

QDS’s physical boundaries were defined by the City of Montreal and PQDS on top of pre-existing districts, yet a cohesive identity of the neighborhood is not always readily acknowledged by residents. Interviewees rarely mention living in QDS and they seem to barely define its social and cultural presence within the geography of other well identifiable nearby areas (such as Chinatown, Quartier Latin, the Gay Village). Many interviewees describe QDS only as the intersection of other, more recognizable, neighborhoods (quartiers) with stronger identities. In this regard, I5 explained why she chose to live in QDS: “I was looking for a neighbourhood close to downtown…And then I realized it was fun to live close to the Gay Village, and also maybe to Chinatown. But two identities” (I5)Footnote3.

Although not entirely acknowledging its exact boundaries and even a cohesive identity, residents describe QDS as a central and well-served area. Interviewees’ choice to live in or around QDS is dominantly related to its proximity to downtown and to the main university campuses, to a high number of services and infrastructures, and, to a slightly lesser extent, to the entertainment offered by festivals. Despite these reported qualities, the sonic environment of the neighborhood was perceived as having been deeply affected by the pandemic, because of the absence of the tourism-related neighborhood life, underused public spaces, and the lack of parks, which discouraged residents (and others) from passing by or spending time in QDS: “Obviously the festivals aren’t happening anymore, they didn’t happen during the summer, so that was a lot quieter. I think that area is pretty dead.” (I4). I6 also shared this feeling: “I honestly was not going there anymore [in QDS] because I felt it was like a ghost area.” (I6).

Some interviewees even considered moving out of QDS, especially when the lack of a lively atmosphere (absence of human activities, events, and neighborhood everyday life) did not justify the disadvantages arising from e.g. high rents, smaller houses, and lack of private outdoor space:

We [have] always love[d] living here. We still find advantages because you can move everywhere in town. But now that you don’t have anywhere to go, it’s kind of a choice that we are going to revisit […] we don’t find it necessary to pay our rent for Quartier des Spectacles now. (I6).

4.2. The indoor sonic experience

Having to spend most of their time at home due to the pandemic, most residents experienced a new understanding of the idea of ‘sonic coexistence’. Interviewees acknowledged and accepted the difficulties related to an unprecedented proximity both with neighbors and housemates: “I would say that the lockdown at home, [when] everyone’s at home, it was noisier for everyone” (I3)Footnote4. Most of the participants agreed that during the lockdown their apartments were not suitable to house multiple activities, as they often interfere sonically with each other. This is particularly true for families, as explained by an interviewee: “I live actually [in a] small apartment, but [we are still] a big family. Six people, me, my wife and four children. So, for us it’s very congested.” (I7).

Whereas neighbors’ noise is generally tolerated among residents, construction and maintenance noise was considered by most interviewees as the primary source of nuisance over the summer of 2020. For some, construction work was even more present than usual, which can be explained by the fact that after a short break (25 March to 11 May) construction activities resumed in Montreal, even while most other facets of public life remained on hold: “I certainly have the impression that there’s more construction noise” (I5)Footnote5. Interestingly, construction noise is considered particularly disturbing when (and likely because) there is a lack of clear communication toward residents on e.g. working hours or the nature of maintenance or construction. In this regard, an interviewee confirms that: “they say [the City] ‘it’s something that we have to do’, but they didn’t specify the working hours and the heaviness of this kind of worksFootnote6. Sometimes the house trembled” (I6). In addition to the noise, what was particularly frustrating for residents was the workers’ seeming disregard for residents, for example in terms of the daily duration of construction noise: “So people felt free to work even at 10:00 PM sometimes. They kept working because they thought: ‘OK, here, no one is living’ because [it] seems that no one was living here.” (I6).

A difference in noise perception and evaluation was observed between students and young professionals (who tended to be short-term residents, usually renters), and families and homeowners (who tended to be longer-term residents). While the desire to live in an enjoyable sonic environment is shared by all interviewees, it’s the latter category that is more willing to make steps toward changing their current environment, by engaging with the complaint system or using other strategies. However, some interviewees added that they feel this category represents a limited number of residents, with one long-term resident arguing that there are too few of them to have true agency or to have a voice on the institutional level.

I spoke to my neighbours a little bit, but we’re not in an area that’s cool where people have that level of expectation. I don’t want to sound stereotypical, but you look at the profile of our street, there’s a lot of renters. […] So it’s not the profile of working professionals, like in the Plateau [a close neighbourhood], who bought property that’s relatively expensive and have high expectations for their quality of life.” (I2)

In turn, students and young professionals seem to have a more passive approach toward handling noise issues; they rarely file noise complaints or report the lack of communication on situations that may cause nuisance. Interestingly, most interviewees share an idea that QDS is mostly a neighborhood for students and young workers: for people more inclined to adapt or leave, thus unwilling to fight for a better sonic environment as they are just temporarily living in the area. Instead of filing noise complaints, young residents are more likely to rely on an array of coping strategies such as masking unwanted sounds with music, using noise-cancelling headphones or re-creating their own sonic environment. One young renter explains their view of QDS: “[The neighbourhood] is for young people like me, because you have to be able to adapt, elder people looking for peace and tranquillity can opt for the countryside or the suburbs” (I3)Footnote7.

4.3. The role of music events in the identity of QDS

Residents experienced a quieter and less dynamic sonic environment during the lockdown, in large part due to the absence of festivals and events and other related activities. Reflecting on previous years, residents referred to nuisances they had sometimes experienced before the pandemic, especially during nighttime; these included, above all, festivalgoers at the end of events, house parties, and more general nightlife activities. In this regard, a house owner and long-term resident comments: “In the middle of the night we weren’t bothered a single time by partygoers coming home from bars, or we didn’t get that really this summer as opposed to other years.” (I2). Even if the quieter sonic environment led to residents having less “negative” experiences, most interviewees emphasized they were, in fact, missing the sounds coming from music festivals, a feeling shared not only among students and young workers, but also among older and long-term residents: “I miss… I love music festivals. So we miss music.” (I7). This aspect is particularly interesting as it draws attention to those events and public activities that became part of the (sonic) identity of the neighborhood.

Residents also stated missing the presence and sometimes participating in music events directly from their homes; enjoying the events from home is certainly a plus for most residents: “So I took the advantage so far to listen to the Jazz Festival, and whatever other festival right from the window.” (I6). Yet, the pandemic-induced break from concerts made some of them reflect on how the indoor/outdoor permeability of music and festival activities can be problematic at times. It was particularly longer-term residents who complained about the frequency and high number of festivals during the summer, as well as about the noisy crowds that remain in QDS after the end of the events: “Like for the festival, because [there are] so many festivals outside around our apartment […] some summer festivals [are] two weeks or four weeks, ten days. [They start] one after the other, you know.” (I7)

However, residents (and particularly the younger ones) employed a wide array of strategies to cope with the absence of music events: some interviewees listened to music through headphones when walking outside, while others played back music in the park to re-create an eventful atmosphere. A young student commented on the situation:

We are all very sad about the concerts we are missing… I think, in general, we all miss going to loud events, but that’s OK. Sometimes we just play music loudly… We listen to our music when we hang out. So I guess that’s, like, a decent substitute. It’s nice sometimes to be in venues with loud music and we have done our best to recreate that. (I4).

4.4. Outdoor sonic experiences in and outside QDS

During the pandemic, most interviewees chose to spend their free time outside the neighborhood, looking for big parks in the closer, often greener, residential areas. Bigger parks were described as the most welcoming and friendly public spaces in town, where people were able to meet and perform activities that would not have been possible elsewhere: “Actually, the only music that I could listen to was in the parks, just spontaneous music that musicians did there.” (I6). The sonic environment perceived in these parks strongly contributed to their attractiveness, especially over the spring and summer of 2020. Many interviewees enjoyed natural sounds and noticed a growing intensity of bird song and the calls of other animals. Additionally, the sounds from human activities performed in parks, and even the simple chattering of other people, were considered as extremely pleasant: “I like going to the public gardens. It’s nice when there’s a lot of people. I enjoy that… I think it’s generally more enjoyable when there’s more people.” (I4).

While parks became the gathering points for many Montrealers – as the overlapping of informal, yet permitted, outdoor activities resulted in a highly diversified and enjoyable sonic environment – interviewees were concerned by the general lack of human activities in QDS public spaces. The effects of too quiet a sonic environment led to a sense of disorientation and even lack of safety: “[about walking in QDS] It’s actually very anxious. You say: ‘My God, where are we?’ And that can give a little sense of insecurity… I’m all alone” (I1)Footnote8. Many interviewees reflected on QDS’s perceived “emptiness” during the pandemic, acknowledging that few people actually live there and that the the area is mainly frequented by tourists and workers, which is why the neighborhood, and the larger public spaces usually hosting big events and activities, felt “dead”. An interviewee comments that: “these areas are very, very touristic, or you can usually see a lot of foreign visitors, and it was completely empty and silent, as there are not many people living there.” (I1)Footnote9. The impression was that little adaptations were made to QDS to encourage its residents to use their neighborhood. For example, one interviewee explained that outdoor installations in one of the main squares (Place des Festivals) failed to enliven the public space as their contents had not been updated from before the pandemic started, so it ended up contributing to a repeating and monotonous sonic environment:

The outdoor spaces, they put some installation that they had also used the year before. Nice that they put something, but the fact that they didn’t renew it from the year before actually sounded [like] ‘OK, there’s nothing new to see here’. (I6).

5. Envisioning the post pandemic future of QDS: a discussion and policy recommendations

Investigating the indoor and outdoor sonic experiences of QDS residents throughout the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic was intended as a starting point for a discussion on how to reorient the process of balancing attractiveness and livability within the entertainment neighborhood. The discussion below builds on the four macro-themes presented in the findings by examining: (i) the importance of animating public QDS spaces by directly engaging QDS residents; (ii) the identity of QDS and its different residents; (iii) the sonic impact of QDS events on residents’ everyday lives; and (iv) the role of residents in the future attractiveness and livability of QDS. We end this section by offering policy recommendations aimed at strengthening the involvement of residents in the social and political life of QDS (see at the end of the section).

Table 3. Schematic representation of the framework emerging from the discussion, and related recommendations.

5.1. Discussion

The success of big parks and pedestrianization projects outside of the entertainment district demonstrated that QDS, unlike other neighborhoods, was not able to attract its own residents and other city users throughout the pandemic period, as its primary attractions – festivals and other large events – were mostly canceled in 2020. This was despite the presence of local pedestrian areas and public spaces in QDS, that seemed to fail to engage locals. The lack of tourists and festival goers profoundly affected the everyday life in QDS, validating other research on touristic destinations that showed they were the locations most affected by the pandemic (Manzano et al. [Citation2021] for Granada, Aletta et al. [Citation2020] for London). Although, before the pandemic, Montreal, and especially QDS, was attracting an increasing number of visitors (Khomsi, Fernandez-Aubin, and Rabier Citation2020), our study described the scenario where the absence of tourists and events (coupled with the constant presence of unpleasant sound sources such as construction or maintenance work) contributed to residents’ often unpleasant experiences of everyday sonic environments in their neighborhood. The perceived unattractive sonic environments of QDS during 2020 raises a question on how QDS could have animated public spaces for its own residents, to offset the absence of tourists and festivalgoers. This opens a discussion on future strategies and participatory soundscape design approaches (Xiao, Lavia, and Kang Citation2018) that QDS and other entertainment districts can develop in order to strengthen their resilience by engaging both tourists and residents in creating public spaces that are attractive for more potential users.

Second, in line with the findings of Bild, Steele, and Guastavino (Citation2021), our findings revealed that short-term renters (students and young professionals) and longer-term residents or homeowners (more likely older generations) share several reasons for living in QDS, especially in relation to the vibrant environment of the neighborhood and the presence of festivals. Yet, we showed that, especially during the lockdown, age and living situations were crucial factors shaping the experience of living in QDS, which confirms some of the main conclusions of Ren, Tang, and Cai (Citation2022) when investigating the notion of acoustic comfort. The absence of events and the decline of the district’s lively atmosphere – and accordingly the emergence of nuisances related to construction and maintenance works, as highlighted by Steele and Guastavino (Citation2021) – increased the gap between long-term residents and young renters, with renters keener to accept construction and maintenance works without complaining, or to simply move out when it became ‘too much’. As the entertainment district is undergoing development, we showed that most negative experiences in the sonic environment can be attributed to construction and maintenance works. This situation confirms the critical impact of QDS redevelopment projects on residents’ everyday life, as claimed by Bélanger and Cameron (Citation2016). Also, this scenario suggests that real estate developers – with the tacit approval of the municipality – seem to encourage and capitalize on the presence of short-term residents in the neighborhood, while using the festivals and events to invite new residents that would be readily accepting of the current living conditions in QDS.

Third, QDS festivals attract a large audience every year and are a key (and inescapable) part of residents’ everyday life, in line with a pre-COVD study (Bild, Steele, and Guastavino Citation2021). During the pandemic, the absence of festivals made residents realize more acutely the importance of musical events in shaping, conveying and reinforcing the identity of their neighborhood. Nonetheless, residents also stated that they experienced and enjoyed a quieter neighborhood, particularly during the nighttime. The pandemic thus offered the chance to better acknowledge both the relevance of festivals in their everyday life – and more broadly QDS’s lively and vibrant sonic environment – as well as the potential negative impact of certain concerts or the crowds at the end of bigger events. Building on these findings, we argue that QDS can strive toward finding a new balance between the sonic experiences and expectations of residents and festival goers in the near and further future.

Finally, the pandemic revealed the overwhelming role of festivals and events in the vitality of QDS and the extent to which residents feel left out or uninvolved in the vitality of the entertainment district outside of the special events taking place. While themselves partaking in events in the neighborhood, the residents’ potential for a unique form of involvement and active participation in the public life of the neighborhood is not sufficiently acknowledged by e.g. PQDS or other event organizers. Since the identity of QDS seems to be well articulated for a visitor audience, that image is far less consolidated for those living immediately inside and outside the neighborhood, with the residents’ sense of belonging to the area needing reinforcement. Nonetheless, despite expectations to the contrary from other touristified areas around the world, residents had a positive evaluation of the festivals and events – elements driving the vitality aspect of QDS in a non-pandemic past, and described a sense of desolation in a generally unpleasant sonic environment left behind in e.g. lockdown conditions. This was similar to the findings of Lenzi, Sadaba, and Lindborg (Citation2021) on the lockdown quietness of a neighborhood in the Basque Country, where the lack of human voices and activities was perceived as particularly unpleasant by participants in the study. Here, the idea that a lively sonic environment is central for the attractiveness of a district also reinforces Kourtit, Nijkamp, and Wahlström’s (Citation2021) claim that the “soul” of the city – the feelings, perceptions and socio-cultural qualities experienced within an urban environment – is crucial for the appreciation of urban areas. Building on these findings, we support the argument that attractiveness and livability within an entertainment neighborhood are not incompatible with each other, as previously discussed by Romão et al. (Citation2018).

5.2. Recommendations and future directions

Confirming the efficient governance of PQDS in the raising of the district’s attractiveness during the festival season over the past decade, yet revealing its lack of inclusiveness – in line with what has been described by Darchen and Tremblay (Citation2013) – we recognize the importance of strengthening PQDS’s resilience and inclusiveness toward residents. This is particularly relevant when no festivals are taking place, and even more so to strengthen the post-pandemic recovery of QDS. To enhance the district’s sonic environment outside of festivals and events and to encourage residents’ participation and use of public space, QDS could further invest in the organization of small-scale interactive outdoor events. Such events could target specific age groups, experiment with new uses of public space, and potentially initiate the regeneration of underused and degraded urban spots – starting by e.g. developing temporary activities around construction sites. Along these lines, we recommend a more extensive use of interactive sound installations throughout the district, as we believe that, combined with other amenities and visual incentives, they could actively contribute to the attractiveness of the area by engaging visitors and residents in unique forms and encourage lingering behaviors and increased social interactions (Steele et al. Citation2019). Also, to enliven underused areas within QDS, new temporary and long-term pedestrianization projects (now limited to summertime) could be developed to contribute to a year-long lively and welcoming sonic environment.

Another issue to be addressed is the management of construction and maintenance works: the lack of communication on these projects alienates residents from feeling involved in the decision-making processes in their neighborhood. To encourage a sense of belonging for both current and future residents of QDS, we propose to articulate regular public consultation strategies between residents, developers and noise control officers. Such public meetings can promote a shared understanding of existing noise by-laws, clarify the rights and duties of involved parties, and help make new proposals to the CityFootnote12, encouraging sonic empowerment among residents and helping them articulate and act upon any potential future noise issues.

The active involvement of residents in the negotiations of the district’s noise by-laws and relative communication should also consider urban nighttime management strategies (see Global Nighttime Recovery Plan [Citation2021]). Here, we underline the key role of PQDS in consistently bridging residents’ needs for livable sonic environments at night with the City’s endeavors to promote the neighborhood’s attractiveness and liveliness during the night. In this sense, we suggest extending public discussions with the different actors involved to further explore the impact of festivals on residents’ everyday life. For example, residents could be involved in designing the soundscapes of shared public spaces or the programming of future festivals and events in a manner that would strengthen their attachment to QDS. Such public discussions could support the engagement of different stakeholders (including residents as key participants) and can thus help QDS to better understand how to adjust to some of the residents’ most pressing sound-related problems. A participatory approach using public consultations with residents and private and public stakeholders could help broaden existing frameworks on participatory soundscape planning (Xiao, Lavia, and Kang Citation2018) beyond the ISO (Citation2016) recommendations to involve participants through interviews, soundwalks, and questionnaires. In summary, we believe that by actively and consistently involving diverse categories of residents in the sound and noise management of the district, the PQDS and the City could effectively prevent future sonic-related issues and promote more inclusive sonic goals striking that fine balance between livability and vitality.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we researched the impact of the pandemic on the sonic experience of residents of Montreal’s Quartier des Spectacles throughout 2020. As the district’s attractiveness was strongly hit by cancelation of the usual festival and events throughout the spring, summer and fall periods, the area failed to welcome tourists and other visitors, and it all led to a significant change in its sonic environment. Conversations with residents in the neighborhood, who used both their indoor and outdoor spaces in QDS throughout the pandemic, showed that the neighborhood was perceived as empty and unwelcoming, with largely uneventful sonic environments. That new reality led to reflections on several sound-related issues faced by the residents (from construction work nuisances to nightlife and festival management during ‘normal’ years) that affected, and will certainly affect in the future, the neighborhood’s livability, and that challenge the environmental planning and management of the district’s sonic environment (Brown and Muhar Citation2004; Kang and Schulte-Fortkamp Citation2017).

Contributing to the debate around the factors enhancing or limiting attractiveness and livability within entertainment districts in the pandemic and post-pandemic city, our study showed the centrality of everyday urban sounds in the district’s potential to attract visitors, while providing residents with a suitable environment for their daily needs. In particular, we have highlighted the need for an increased role for residents in the development of a livelier and more welcoming everyday sonic environment – and a more resilient neighborhood – beyond the presence (or absence) of festivals and events.

Drawing from our results, we suggested that the key challenge for the future of Montreal’s entertainment district is finding ways for a stronger involvement of its residents in its everyday cultural life and decision-making. We further argued that the reinforcement of QDS’s livability does not contrast with – yet is the condition for – the district’s future attractiveness, as the development of new touristic and entertainment economies can substantially benefit from a neighborhood that is also lively in times of crisis.

To strengthen residents’ engagement in cultural activities and their involvement in the life of the district, we argue that multiple, sound-oriented participatory processes could be developed to connect the everyday sonic experiences to different urban policies and programs addressing current noise regulations, urban nightlife governance, and QDS’s festival management. Taking a sonic perspective for the post-pandemic recovery of Montreal’s entertainment district, we argue that urban attractiveness and livability do not have to conflict in QDS, as they are closely intertwined within people’s sonic experiences. Building on these findings, we highlight avenues for entertainment districts to consolidate both their attractiveness and livability, ultimately building more cohesive and inclusive identities as well as resilience.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at http://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2022.2100247.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Following Romão et al. (Citation2018), in this paper we define attractiveness at the residents’ and visitors’ appreciation of an area for both living and entertainment purposes. For an overview of the impact of COVID-19 on the Tourism sector in Canada see: Statistics Canada (Citation2021).

2 “While only broad information is available, estimates suggest that 12,000 residents live in the neighbourhood (a number that is growing), with 45,000 jobs available and around 50,000 students using the many educational buildings.” (Steele and Guastavino [Citation2021], 2).

3 “Je voulais un quartier qui est proche du centre ville… Après moi je trouve que c’est fun d’être, proche du village gay. Et puis aussi, euh, peut être proche du Chinatown. Mais 2 identités…” (I5).

4 “Je te dirais que le confinement en général à la maison, tout le monde est à la maison, c’était plus bruyant pour tout le monde” (I3).

5 “C’est sûr que j’ai l’impression qu’il y a plus de bruit de construction” (I5).

6 The term “heaviness” is an anglicization. The interviewee refers here to the intensity of the construction works.

7 “[Le quartier] est pour des personnes jeunes comme moi, parce qu’il faut être capable de s’adapter avec ça, c’est une personne âgée qui cherchent la tranquillité paisible pour que la campagne ou les banlieues.” (I3).

8 “[Marcher dans QDS] C’est très anxiogène en fait. Tu dis ‘mon Dieu, mais où est-ce qu’on est?’ Et ça, ça peut donner un petit sentiment d’insécurité […] Je suis tout seul.” (I1)

9 “Des places sont très très touristiques d’habitude où tu vois énormément de touristes étrangers et là en fait c’était complètement vide et silencieux comme y’a pas grand monde qui habite là-bas” (I1).

10 “T’as toujours un espèce de brouhaha de fond parce que t’as toujours des restos, des machins, puis t’as des gens qui marche” (I1).

11 “Il y avait beaucoup de gens dans les rues normalement, mettons sur Saint-Denis. Tu sais, quand il devient piéton, c’est quand même vraiment cool” (I5)

12 In the city of Montreal each borough has a specific noise by-law. For the Quartier des Spectacles, which falls under the Ville-Marie borough, see City of Montreal (Citation2001) and subsequent amendments. For a systematic overview of the municipal noise regulations in Québec see Trudeau et al. (Citation2020).

References

- Abbas, J., R. Mubeen, P. Terhemba Iorember, S. Raza, and G. Mamirkulova. 2021. “Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism: Transformational Potential and Implications for a Sustainable Recovery of the Travel and Leisure Industry.” Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2: 100033. doi:10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033.

- Aletta, F., T. Oberman, A. Mitchell, H. Tong, and J. Kang. 2020. “Assessing the Changing Urban Sound Environment during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period Using Short-Term Acoustic Measurements.” Noise Mapping 7 (1): 123–134. doi:10.1515/noise-2020-0011.

- Aletta, F., and J. Kang J., 2018. “Towards an Urban Vibrancy Model: A Soundscape Approach.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (8): 1712. 10.3390/ijerph15081712.

- Arribas-Bel, D., K. Kourtit, and P. Nijkamp. 2016. “The Sociocultural Sources of Urban Buzz.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 34 (1): 188–204. doi:10.1177/0263774X15614711.

- Asensio, C., I. Pavón, and G. de Arcas. 2020. “Changes in Noise Levels in the City of Madrid during COVID-19 Lockdown in 2020.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 148 (3): 1748. doi:10.1121/10.0002008.

- Barrette, Y. 2018. “Le Quartier des spectacles à Montréal: La consolidation du spectaculaire.” Téoros 33 (2). doi:10.7202/1042435ar.

- Basu, B., E. Murphy, A. Molter, A. Sarkar Basu, S. Sannigrahi, M. Belmonte, and F. Pilla. 2021. “Investigating Changes in Noise Pollution Due to the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Case of Dublin, Ireland.” Sustainable Cities and Society 65: 102597. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102597.

- Bélanger, H., and S. Cameron. 2016. “L’expérience d’habiter dans ou autour du Quartier des spectacles de Montréal.” Lien Social et Politiques 77 (77): 126–147. doi:10.7202/1037905ar.

- Bild, E., D. Steele, and C. Guastavino. 2021. “At Home in Montreal’s Quartier Des Spectacles Festival Neighbourhood.” Journal of Sonic Studies 21. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1278472/1278473.

- Brown, A. L., and A. Muhar. 2004. “An Approach to the Acoustic Design of Outdoor Space.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 47 (6): 827–842. doi:10.1080/0964056042000284857.

- Bui, Q., and E. Badger. 2020. “The Coronavirus Quieted City Noise. Listen to What’s Left.” The New York Times, May 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/22/upshot/coronavirus-quiet-city-noise.html.

- Cameron, S., and H. Bélanger. 2012. “Home Territories and the Atmosphere of Spectacle: The Experience of Residents Living in and around Montreal’s Quartier des Spectacles - A Phenomenological Inquiry.” Paper presented at the Ambiances in Action/Ambiances en acte(s) - International Congress on Ambiances, Montreal, September, 359–364. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00745941/document.

- Casakin, H., B. Hernandez, and C. Ruiz. 2015. “Place Attachment and Place Identity in Israeli Cities.” Cities 42: 224–230. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.07.007.

- City of Montreal. 2001. “Urban Planning By-Law for Ville-Marie Borough (By-law 01-282).” https://montreal.ca/en/reglements-municipaux/recherche/60d761dbfd65315b185780ec

- Cocola-Gant, A. 2018. “Tourism Gentrification.” In Handbook of Gentrification Studies, edited by L. Lees and M. Phillips, 281–293. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Colomb, C., and J. Navy. 2017. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City. London: Routledge.

- Darchen, S., and D. G. Tremblay. 2013. “The Local Governance of Culture-Led Regeneration Projects: A Comparison between Montreal and Toronto.” Urban Research & Practice 6 (2): 140–157. doi:10.1080/17535069.2013.808433.

- Derryberry, E. P., J. N. Phillips, G. E. Derryberry, M. J. Blum, and D. Luther. 2020. “Singing in a Silent Spring: Birds Respond to a Half-Century Soundscape Reversion during the COVID-19 Shutdown.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 370 (6516): 575–579. doi:10.1126/science.abd5777.

- Devine-Wright, P. 2013. “Think Global, Act Local? The Relevance of Place Attachments and Place Identities in a Climate Changed World.” Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions 23 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.08.003.

- Ducas, I. 2020. “Baisse de 92% de La Fréquentation Du Centre-Ville de Montréal.” La Presse, September 16. https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/grand-montreal/2020-09-16/baisse-de-92-de-la-frequentation-du-centre-ville-de-montreal.php.

- Florida, R., A. Rodríguez-Pose, and M. Storper. 2021. “Cities in a Post-COVID World.” Urban Studies. doi:10.1177/00420980211018072.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Global Nighttime Recovery Plan. 2021. “Chapter Five: Nighttime Governance in Times of Covid.” https://www.mcgill.ca/centre-montreal/files/centre-montreal/ch5_nighttime_governance_gnrp.pdf.

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization). 2014. Acoustics — Soundscape — Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework. ISO/FDIS 12913-1:2014. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization). 2016. Acoustics - Soundscape - Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements. ISO/CD 12913-2:2016(E). Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- Kang, J., and B. Schulte-Fortkamp, eds. 2017. Soundscape and the Built Environment. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/b19145.

- Khomsi, M. R., L. Fernandez-Aubin, and L. Rabier. 2020. “A Prospective Analysis of Overtourism in Montreal.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 37 (8–9): 873–886. doi:10.1080/10548408.2020.1791782.

- Kourtit, K., P. Nijkamp, and M. H. Wahlström. 2021. “How to Make Cities the Home of People: A ‘Soul and Body’ Analysis of Urban Attractiveness.” Land Use Policy 111: 104734. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104734.

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, Joanna, Marek Grochowicz, and Robert Pawlusiński. 2021. “How a Tourism City Responds to COVID-19: A CEE Perspective (Kraków Case Study).” Sustainability 13 (14): 7914. doi:10.3390/su13147914.

- Lee, P. J., and J. H. Jeong. 2021. “Attitudes towards Outdoor and Neighbour Noise during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Case Study in London.” Sustainable Cities and Society 67: 102768. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2021.102768.

- Lenzi, S., J. Sadaba, and P. Lindborg. 2021. “Soundscape in Times of Change: Case Study of a City Neighbourhood during the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 570741. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.570741.

- Manzano, J., J. Pastor, R. Quesada, F. Aletta, T. Oberman, A. Mitchell, and J. Kang. 2021. “The “Sound of Silence” in Granada during the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Noise Mapping 8 (1): 16–31. doi:10.1515/noise-2021-0002.

- Margier, A., and G. Ethier. 2021. “Urban Spectacularisation and Social Housing: An Asymmetrical Relation? The Habitations Jeanne-Mance in Montreal’s Quartier Des Spectacles.” Urban Research & Practice : 1–24. . doi:10.1080/17535069.2021.1938196.

- McCartney, G., J. Pinto, and M. Liu. 2021. “City Resilience and Recovery from COVID-19: The Case of Macao.” Cities (London, England) 112: 103130. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103130.

- Mitchell, A., T. Oberman, F. Aletta, M. Kachlicka, M. Lionello, M. Erfanian, and J. Kang. 2021. “Investigating Urban Soundscapes of the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Predictive Soundscape Modeling Approach.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 150 (6): 4474–4488. doi:10.1121/10.0008928.

- Munoz, P., B. Vincent, C. Domergue, V. Gissinger, S. Guillot, Y. Halbwachs, and V. Janillon. 2020. “Lockdown during COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Road Traffic Noise and on the Perception of Sound Environment in France.” Noise Mapping 7 (1): 287–302. doi:10.1515/noise-2020-0024.

- Nhamo, G., K. Dube, and D. Chikodzi. 2020. Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Industry. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56231-1.

- Pagès, R., F. Alías, P. Bellucci, P. Cartolano, I. Coppa, L. Peruzzi, A. Bisceglie, and G. Zambon. 2020. “Noise at the Time of COVID 19: The Impact in Some Areas in Rome and Milan, Italy.” Noise Mapping 7 (1): 248–264. doi:10.1515/noise-2020-0021.

- Quartier des Spectacles Montréal. 2021. “Re-Imagining Urban Spaces and Culture during a Global Pandemic.” https://www.quartierdesspectacles.com/en/media/re-imagining-urban-spaces.

- Ren, X., J. Tang, and J. Cai. 2022. “A Comfortable Soundscape Perspective in Acoustic Environmental Planning and Management: A Case Study Based on Local Resident Audio-Visual Perceptions.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 65 (9): 1753–1780. doi:10.1080/09640568.2021.1947203.

- Romão, J., K. Kourtit, B. Neuts, and P. Nijkamp. 2018. “The Smart City as a Common Place for Tourists and Residents: A Structural Analysis of the Determinants of Urban Attractiveness.” Cities 78: 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.007.

- Rowe, D. J. 2020. “COVID-19 in Quebec: A Timeline of Key Dates and Events.” CTV News, July 14. https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/covid-19-in-quebec-a-timeline-of-key-dates-and-events-1.4892912.

- Sassen, S. 2010. “The City: Its Return as a Lens for Social Theory.” City, Culture and Society 1 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2010.04.003.

- Sequera, J., and J. Nofre. 2018. “Shaken, Not Stirred. New Debates on Touristification and the Limits of Gentrification.” City 22 (5–6): 843–855. doi:10.1080/13604813.2018.1548819.

- Smith, J. W., and B. C. Pijanowski. 2014. “Human and Policy Dimensions of Soundscape Ecology.” Global Environmental Change 28: 63–74. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.05.007.

- Steele, D., and C. Guastavino. 2021. “Quieted City Sounds during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Montreal.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (11): 5877. doi:10.3390/ijerph18115877.

- Steele, D., E. Bild, C. Tarlao, and C. Guastavino. 2019. “Soundtracking the Public Space: Outcomes of the Musikiosk Soundscape Intervention.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (10): 1865. doi:10.3390/ijerph16101865.

- Tam, S., S. Sood, and C. Johnston. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector, second quarter of 2021.” Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00023-eng.htm

- Tong, H., F. Aletta, A. Mitchell, T. Oberman, and J. Kang. 2021. “Increases in Noise Complaints during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Spring 2020: A Case Study in Greater London, UK.” Science of the Total Environment 785: 147213. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147213.

- Torresin, S., R. Albatici, F. Aletta, F. Babich, T. Oberman, A. E. Stawinoga, and J. Kang. 2021. “Indoor Soundscapes at Home during the COVID-19 Lockdown in London – Part I: Associations between the Perception of the Acoustic Environment, Occupantś Activity and Well-Being.” Applied Acoustics 183: 108305. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2021.108305.

- Trudeau, C., E. Bild, T. Padois, M. Perna, R. Dumoulin, T. Dupont, and C. Guastavino. 2020. “Municipal Noise Regulations in Québec.” Paper presented at Forum Acusticum, Lyon, December, 7–11.

- UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development). 2021. “Covid-19 and Tourism, an Update. Assessing the Economic Consequences.” https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditcinf2021d3_en_0.pdf.

- Vogiatzis, K., V. Zafiropoulou, G. Gerolymatou, D. Dimitriou, B. Halkias, A. Papadimitriou, and A. Konstantinidis. 2020. “The Noise Climate at the Time of SARS-CoV-2 VIRUS/COVID-19 Disease in Athens – Greece: The Case of Athens International Airport and the Athens Ring Road (Attiki Odos).” Noise Mapping 7 (1): 154–170. doi:10.1515/noise-2020-0014.

- WTO (World Tourism Organization). 2012. “Global Report on City Tourism: Cities 2012 Project.” doi: 10.18111/9789284415300.

- Xiao, J., L. Lavia, and J. Kang. 2018. “Towards an Agile Participatory Urban Soundscape Planning Framework.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61 (4): 677–698. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1331843.

- Zenker, S., and N. Rütter. 2014. “Is Satisfaction the Key? The Role of Citizen Satisfaction, Place Attachment and Place Brand Attitude on Positive Citizenship Behavior.” Cities 38: 11–17. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.12.009.