Abstract

Public Inquiry is an established process for effective testing and scrutiny of plans in terrestrial planning and is regarded as a means of providing credibility and accountability. Independent Investigation is its marine equivalent and was included as a provision in the UK marine planning regime and subsequent legislation since its inception. However, it has been noticeably absent in practice. This paper investigates the reasons behind this situation within the context of the proposed and actual role of II in the marine planning process in the UK. It additionally considers the future use of II in enhancing the quality and effectiveness of the marine planning system. This paper concludes that as the use of the marine resource of the UK becomes increasingly contested and controversial, II could be utilized to enhance marine plans and marine planning decisions and thus warrants further investigation.

1. Introduction

Public Inquiry is an established process for effective testing and public scrutiny of plans in the town and country planning system, providing credibility and accountability. It has been included as a provision in the UK marine planning statutory regime and subsequent legislation and renamed Independent Investigation (II) since its inception. However, it has been noticeably absent in practice. This article investigates the development of the statutory marine planning process in relation to II, including a comparison with the terrestrial planning system. We consider how the perceived role and value of II has changed with the development of marine spatial planning (MSP) in practice in the process of creating the first tranche of marine plans in the UK. Subsequently, we explore in detail why II has scarcely been used and identify the perceived issues and benefits of this tool for marine planning. We seek to uncover whether II in MSP is necessary or discretionary. In answering this, we consider whether II of marine plans enhances the credibility, effectiveness and implementation of marine planning in the UK and, if so, what form this should take. Supplementary issues are raised in terms of why II was included in legislation, if it was not to be utilized in practice? We suggest the inclusion of II could be the reinvigoration that the statutory marine planning system needs in the UK, with marine areas facing ever mounting pressures after more than 10 years of the current planning regime, and an increasing frequency with which development decisions are being contested? In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to first understand the nature and origins of II.

2. Background

This section explores the development and origins of II as a concept comparable with ‘Independent Examination’, ‘Public Inquiries’ and ‘Public Examinations’ ‘Examinations in Public’. These terms are part of the public discourse and engagement with primarily high-level, high-profile land use decisions. We then explain the steps toward embracing a marine planning system in the UK, including the adoption of II as part of the marine plan-making apparatus and its consequent underemployment in the marine plan-making process.

3. Inquiries and the environment

The concept of an inquiry or an examination of a plan and its policies before adoption is well established in terrestrial planning procedures (Reeves and Burley Citation2002). Public scrutiny is an important part of the planning process. Murray and Greer (Citation2002) usefully clarify the concept of the examination tool as generally designed to provide information through informed discussion of certain matters relevant to policy making. Whilst the principles have rarely been challenged, the objective remains clear. It is both a means to collect evidence to enable decisions to be made and, at the same time, it is an adjudicated hearing allowing for conflicting opinions to be heard.

In Great Britain, the tool has long been used for the preparation of Structure Plans. It was a marked shift away from the conventional, highly formalized and adversarial public inquiry process and is viewed as a style of planning through dialogue. Leach and Wingfield (Citation1999) note the use of more participatory, inquisitorial, tools are the mainstream of initiatives to secure citizen deliberation over contemporary public policy.

The Examination in Public (EiP), is essentially an inquisitorial process but it allows for adversarial procedures and was used for, the now defunct, Regional Spatial Strategies (RSS). Inquiries are often the arena which displays the tension between policies in the national interest and local interests, and going back to their origins, setting public versus private interests (Baker, Roberts, and Shaw Citation2003). It does, however, provide opportunities for effective deliberative discourse as participants are able to engage with each other’s rationale and objectives through informed discussion, leading some to suggest that it has the potential to be a highly inclusive process, attracting a high level of confidence from participants (Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010; McEldowney and Sterrett Citation2001; Murray and Greer Citation2002). Furthermore, some have noted how such planning fora have provided critical institutional challenges for questioning the overall trajectory of policy progression (Cowell and Owens Citation2006). Looking back into the origins of public inquiries in the UK, O’Riordan, Kemp, and Purdue (Citation1988, 21) suggested they could be traced back to the time of the enclosures in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and that their purpose was to facilitate the private acquisition of communal property, mainly common land.

Following a landmark case over the public acquisition of land at Crichel Down in 1954 the ‘Franks Committee’ (Lord Chancellor’s Department Citation1957) was established to determine the principles by which public inquiries should be conducted. The Committee’s report, published in 1957, established three principles for the conduct of inquiries: openness, fairness and impartiality. ‘Openness’ implies public involvement, ‘fairness’ requires clear procedures and even-handedness, and ‘impartiality’ requires independence of judgment from responsible organizations. These principles still apply today. Franks argued that they “must allow for the exercise of a wide discretion in the balancing of public and private interests” (para 272).

Following growing discontent and contestation at the approach to, and the experience of, slum clearance programmes and postwar regeneration in the UK, the Planning Advisory Group was established in 1964 to recommend changes to the town planning system. In its report ‘The Future of Development Plans’ (Planning Advisory Group Citation1965) it was recommended that decisions about the future planning of local areas should be devolved to local authorities and that there should be scope for greater public participation in that process. Baker, Coaffee, and Sherriff (Citation2007) note that stakeholder engagement is one of the fundamental components of the planning system. Morphet (Citation2005) went on to say that planning was the first UK public service to introduce public participation. The subsequent publication of the Skeffington Report (HM Government Citation1969) set out many of the principles of public involvement in town planning and in development planning. This reflects a growing revolt, at that time, against the technocratic framing of planning activities. In addition, and in line with the rise of communicative planning, there was a move away from viewing plans as fixed structures, toward plans as strategies; opening up opportunities for more proactive and inclusive approaches for achieving a plan’s intended outcomes. Baker, Coaffee, and Sherriff (Citation2007) add that whilst Skeffington is limited in many ways compared to today’s requirements and expectations, the report’s principles remain sensible and practical.

One of the consistent features of the contemporary terrestrial planning system in the UK is the adoption of a plan-led system which is characteristically recognized by development plan arrangements. Development plans form the basis for decisions on individual planning applications. These provide the allocation of land (and now marine) resources and provide the policy context for consistent decision making. Yet this must be clarified by noting that whilst development plans indicate which sites are acceptable for development, planning authorities have more discretion in determining planning applications (Reeves and Burley Citation2002), so the UK system is not legally binding. For example, this is unlike the German system, where appeals can only be made on legal grounds. Forward planning reflects the aspirational nature of the development plans as they guide future development, discourage undesirable development and set a strategic direction for the plan period (typically 15–20 years) (Sheppard et al. Citation2017). In the UK, after the development plan is drafted, it is sent to the Secretary of State (and equivalent in the devolved nations) who appoints an inspector to carry out an independent examination in scrutinizing the plan. The purpose of the examination is to assess whether the plan has been prepared in accordance with legal compliance and procedural requirements and if it is sound. The inspectors consider the evidence put forward by the Local Planning Authority (LPA) to support the plan and any representation that has been put forward by local people and other interested parties. In most cases there will be a public hearing session. At the end of the examination, the inspector sends their report to the LPA recommending whether the plan can be adopted or if modifications are required. This is the general process for scrutinizing plans and is known by various titles and using similar but different formats. Yet, the term “Independent Investigation” is the equivalent title given to the scrutiny phase in marine planning under the UK Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (MCAA, HM Government Citation2009). This legislation and the introduction of marine planning in the UK is discussed later. It is notable that the PINS document ‘Marine Plans: Independent Investigations’ (Citation2014) makes it clear that the Franks’ principles of openness, fairness and impartiality shall apply and that once an II has been called, if at all, that any member of the public may make representations. In the MCAA, the decision to initiate an II lies with the parent government department on the recommendation of the MMO or other marine plan-making bodies in the UK. Even then it is merely a recommendation that the Secretary of State has the option to act on. Under the II it is envisaged that the engagement is initially in written form between the Independent Investigator and the key stakeholders involved. If the issues are not resolvable in this manner, a full II will follow, with the investigator deciding who to invite. However, the invitation of a public gallery is not guaranteed for the II.

This is in contrast to the provisions of Town and Country Planning legislation in the UK where the responsibility for investigating the soundness of draft plans lies solely with the commissioning central government agencies. In terrestrial planning this is nearly always the case, but in marine planning, so far, the opportunity to investigate the plan has only been utilized once. It is also important to clarify that II is wholly different to public scrutiny, which is limited to public consultation on marine plans. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission recently published an international guide on MSP (Citation2021) and in evaluating Marine Plans and their relevance, they mention ‘anticipatory evaluation’. This is about the evaluation of plans, yet it is connected and may be complementary to II. As well as public consultation, there are other assessment practices involved in the development of a marine plan, Strategic Environmental Assessment and Sustainability Appraisal. Aligning II to these other assessments may be one way to help MSP practitioners understand the relevance of II.

4. Development of marine spatial planning in the UK: the influence of town and country planning

The process of planning is straightforward – data gathering – analysis – plan – monitor – review. Patrick Geddes is regarded as the originator of the concept of ‘survey, analysis, plan’. As a zoologist, he was strongly influenced by theories of evolution but argued that his formula could be applied to social, as well as natural science. Such an approach is a classic example of rational decision-making (Lindblom Citation1968). Sometimes described as a top-down approach, its principles underlie both terrestrial and marine plan-making. Critically, II is part of the review element of such a process where policies arrived at through a logical and rational decision-making process are checked to ensure that they do not have unforeseen outcomes for stakeholders.

Experience from terrestrial planning has helped to inform the design of the emerging marine planning system (see Tyldesley Citation2004; Marine Spatial Planning Project Consortium Citation2006). Clearly, one of the most significant commonalities between the two systems is the concern to control adverse impacts of human development (Kidd and Ellis Citation2012). The negative impacts of human development causing almost ‘industrialisation’ of the marine environment is well documented and is set to worsen in coming decades (Berkes et al. Citation2006; Douvere Citation2008; Nellemann, Hain, and Alder Citation2008; Halpern et al. Citation2008; Worm et al. Citation2006; Worm and Lotze Citation2021). Jay (Citation2010) highlighted that growth in the maritime sectors not only increases demand for marine space, but generated potential conflicts amongst marine users.

The disjointed regulation of marine activities and associated cumulative and conflicting uses and pressures have given rise to the ‘marine problem’ (Peel and Lloyd Citation2004; Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010). While not discussed at length in this paper, conflicts in the marine environment are commonplace. As outlined by Tafon et al. (Citation2021, 7), this is especially true at the land–sea interface, “where land- and sea-based value-rationalities and interests often clash in a multiscale terrain of plural actors, institutions, worldviews and visions.” Such conflicts include competing values, identities, and property rights as well as the uneven distribution of costs and benefits (Cicin-Sain Citation1992; Ritchie and McElduff Citation2020; Tafon et al. Citation2021). These conflicts are likely to intensify, and new disputes emerge, as human uses and demands of the marine resource increase. MSP has established itself as a dominant tool for overcoming the traditional sectoral approach to marine management, and managing current, and future, conflicts in a sustainable and integrated manner (Douvere Citation2008). It is therefore essential that the MSP process is transparent and inclusive, and that marine plans are equitable, integrated and well-informed (Flannery et al. Citation2016, 136), to help ensure issues of power and exploitation do not emerge (Flannery and Ellis Citation2016).

Some would argue that planning marine resources can be undertaken by a similar manner to terrestrial planning in terms of the emphasis placed on promoting sustainable development, facilitating stakeholder engagement and public participation, and devising a plan-led approach to inform individual development and consenting decisions in a coordinated, coherent, integrated and consistent way (Sheppard et al. Citation2017). Similarities between land and marine environments are often contested, especially around different and complex public and private property rights and responsibilities, and access and exploitation of marine resources (Feeny et al. Citation1996), as well as the three-dimensional aspect of the marine environment (Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010). Kidd and Ellis (Citation2012) specifically highlight the intricate pattern of land ownership and resulting territoriality have shaped the legal form of TSP and the number of stakeholders involved (Campbell and Marshall Citation2000; Healey Citation1997).

The UK was one of the first countries in the EU to establish a fully integrated planning system for its marine environment. It extended the broad principles of the terrestrial planning system to the territorial (12 nm) and offshore waters out to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (200 nm) (Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010). This included a plan-led system adopting the same predominance of a plan, similar to the terrestrial system, whilst maintaining the discretionary nature of the overall system (again as exists in the British planning system as a whole) (MCAA Citation2009) (Sheppard et al. Citation2017).

The introduction of primary legislation, the MCAA 2009 marked a major watershed, if under-appreciated, milestone for environmental regulation in the UK. It has established a comprehensive regulatory planning system for the UK’s marine environment (Ritchie and Ellis Citation2010). The MCAA was responding to the fact that marine and coastal frameworks needed to be updated to better fit the complex 21st century demands of the rapidly expanding marine sector (Ritchie and Flannery Citation2017; Boyes and Elliot Citation2015). In an attempt to redress the piecemeal approach to marine legislation and regulation that had built up over centuries, the UK Government recognized the need for a new framework for the sustainable management of the sea. MSP would, strategically, seek to balance conservation, energy and resource needs and that would contribute to the UK’s shared vision of a clean, healthy and productive marine environment (Defra Citation2002, Citation2007). Ritchie and McElduff (Citation2020) note that early literature tracing the evolution of MSP highlighted the impetus toward the creation of a new institutional framework to improve coordination, overcome sectoral fragmentation and address policy duplication (for example see, Bull and Laffoley Citation2003; Canning Citation2003; Tyldesley Citation2004).

It is important to note that the marine planning system emerged at a time of seismic shifts in planning policy development across the UK. For example, the National Policy Statements (NPS) in England as part of the 2008 Planning Act covering major infrastructure development in the marine and terrestrial environments were introduced. The third National Planning Framework (NPF) in Scotland and offshore wind policy sectoral plans were all emerging over this period. It is interesting to note that these all had significant public consultation and engagement requirements and processes, but none of them resulted in a public inquiry or II. In Scotland, a significant marine use, aquaculture, was part of the terrestrial planning system and therefore was well established in terms of policy by the new local development plans being rolled out as part of a fundamental reform of the planning system in Scotland (Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006). These local development plans were, and continue to be, subject to examination by Scottish Ministers.

5. Devolved nature of UK marine planning

The passing of the MCAA was followed by the publication of a joint UK National Marine Policy Statement (MPS) (HM Government, Northern Ireland Executive, Scottish Government, Welsh Assembly Government Citation2011) which was to be elaborated through a series of regional marine and national plans. The management of UK waters is complicated by the devolution of responsibilities from central government to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland with the result that territorial seas (0–12nm) are the responsibility of devolved administrations (EC Citation2008). Consequently, Scotland and Northern Ireland adopted their own parallel legislation in 2010 and 2013 through the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 and Marine (Northern Ireland) Act 2013 shown in .

Table 1. Summary of Marine Plan development, legislation and marine authorities.

The issue we are concerned with is the neglected area of II. Whilst the equivalent of II is prevalent and well established in the terrestrial planning environment, it is under-researched and under-utilized in the marine environment, given the infancy of the emerging MSP system. Initial research shows there appears to be a perceived reticence to engage with the II process. The research methods used to explore this question in detail are now set out.

6. Research approach

A mixed method of qualitative empirical research was employed to address the issue of whether II in MSP is necessary or discretionary. The approach was designed around three key stages. The first was a content analysis of policy documents which contained an explicit reference to II. This included key word searches and analysis of legislation and plans across the UK. This provided detail on the origins and original vision for the statutory marine planning process in the UK. It also identified detail concerning the inclusion of II, what it meant and how the role of II has changed with the development of MSP in practice. The list of documents consulted is included in .

Table 2. List of documents reviewed and analyzed for Independent Investigation in the development of Marine planning.

The research process of document review and analysis established that the emerging MSP regime was being developed drawing on methods and processes of terrestrial planning, while creating distinct processes and procedures for marine planning governance. As many of the documents noted above were instrumental to the development of the MSP process, namely the early RSPB/RTPI publication (Citation2004) and the MSP Irish Sea Pilot (Citation2006), it was interesting to observe the emergence of the broad objectives of the MSP system, to the detailed guidance in the later documents regarding the conduct of II (PINS Citation2014). Running throughout all the documents is a recognition that “all marine users will have an opportunity to get involved in the planning process” (Defra Citation2008, 26) with extensive opportunities for ‘stakeholder involvement and consultation’. It is important to note that this is in relation to public scrutiny, not so much on the mechanics of II. There did not appear to be details specifically on how to mediate the different views expressed by respondents to the draft plans. Consequently, Ritchie and Ellis (Citation2010, 707) noted that how participation would work in the marine context remained ‘untested’ and had attracted ‘very little speculation’. This remains the case and so it was apparent, that there was ‘clear blue water’ between the existing town and country planning system and the emerging MSP. This process of compare and contrast continued in the second stage of the research. This examined existing arrangements for II, or the equivalent, in the terrestrial and the marine environment across the UK and devolved administrations. This is set out in detail later in the paper and is summarized in .

Table 3. Overview of Marine Plans route to adoption: UK.

The final stage of the process consisted of a series of seventeen semi-structured interviews. These interviews were conducted utilizing the information gathered from the first two stages of the project. The aim was to interrogate the role of II in marine planning with a selection of key actors involved in all aspects of the statutory marine planning process across the UK. Due to the novel and niche nature of this area of research, the pool of potential interviewees was small. Additionally, the interviews were conducted remotely during the COVID-19 lockdown. This meant the uptake to interview was further narrowed, yet the results from those interviews secured provided a rich insight into MSP in practice. A variety of techniques were used, including video-conferencing platforms (Zoom and MS Teams), telephone and email. Participants were selected by the researchers as being known to them as experts in their field in the four administrations with the breakdown as follows: seven were from Northern Ireland, five from Scotland and five from England and Wales (taken together). To allow for the depth and breadth of responses, the interviewees were selected for their involvement in the process of marine and terrestrial planning from a variety of professional perspectives. Some are currently involved in marine planning; others were instrumental in drawing up the guidance and influencing the legislation and some were involved in both. The range of planning professionals, including consultants (three), advisers (two), public engagement officers (one), NGO representatives (two), examining inspectors (one), lawyers (two), developer (one), marine and terrestrial planners (five). The interviews were based around the following questions:

Why has II not been used in the majority of adopted marine plans?

What would be the benefits of utilizing the option of II?

What would be the costs of having an II?

What form should II take if used?

The interviews were designed to augment the material collated in the review of legislation and policy; and to explore why the terrestrial and marine planning systems, should diverge over this key area. Indeed, the rich cross-section of interviewees gave very different perspectives on the process of plan-making without the use of a formal II. All responses have been anonymised and are non-attributable.

In practice, there is little evidence to draw on, as only in one case has there been an attempt to initiate II into a marine plan, in Scotland’s Marine Plan, 2015 (discussed later). However, the failure to utilize that opportunity has, in itself, had consequences. It was these lost opportunities that the researchers sought to explore through the interviews with key stakeholders and practitioners. The next section sets out the results and findings of the research.

7. Findings of the document analysis

The foundational stage of the research was a content analysis of documents which contained an explicit reference to II. This included key word searches and analysis of legislation and plans across the UK. This provided detail on the origins and original vision for the statutory marine planning process in the UK. It also identified detail about the inclusion of II, what it meant, and how the role of II has changed with the development of MSP in practice.

The review established that the concept of MSP was first raised in connection with UK marine waters in the Interim Report of the UK Government’s ‘Review of Marine Nature Conservation Working Group’ (Citation2001) and was followed up in ‘Safeguarding our Seas’ (Defra Citation2002) when the government (Defra, Scottish Executive and Welsh Assembly) committed to develop spatial planning processes for the management of marine activities. The Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC Citation2002) was tasked with reviewing Marine Nature Conservation using the Irish Sea as a pilot area to test out a framework for nature conservation. The report ‘Irish Sea Pilot Project, Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Framework’ (Citation2004) prepared by David Tyldesley and Associates was commissioned by JNCC to evaluate the need and principles of MSP. It advocated a participatory planning system and made reference to an EiP of marine plans. David Tyldesley Associates was also responsible for a joint study into MSP for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Scotland and Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) Scotland; ‘Making the Case for Marine Spatial Planning in Scotland’ (Citation2004). In it, the authors set out the benefits of MSP and what it might entail. The report similarly recommended a participatory approach and again makes reference to an EiP.

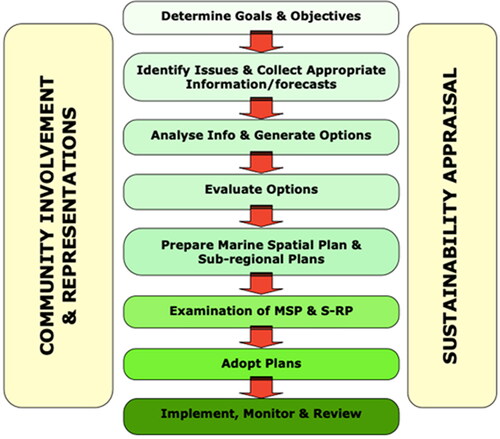

The review noted the importance of the Marine Spatial Planning Irish Sea Pilot (Citation2006). This piece of work recommended to Defra (the commissioning department) the use of II in a form akin to EiP and illustrated the Examination as an integral part of the plan production process (see ).

The MCAA incorporated a section on Marine Planning (Part 3) which detailed the role of the Marine Policy Statement, Marine Plans, Delegated Functions and Implementation. Schedule 6 para 13 set out the basis upon which an II was to be considered. Para 13(1) “A marine plan (…) must consider appointing an independent person to investigate the proposals contained in that draft and to report on them”. Para 13(2) cited the circumstances under which an independent person might be appointed to conduct such an investigation. The three circumstances identified were that representations had been received about (a) matters in the plan, (b) matters in a consultation draft, (c) where such matters had not been resolved. In addition, beyond those three circumstances the marine plan authority might decide to appoint such a person on the basis of “such other matters as (they) consider relevant”.

A guidance note prepared by the Planning Inspectorate (PINS); ‘Marine Plans: Independent Investigations’ (Citation2014) interpreted the statute in a specific way. The PINS note said “after public consultation on the draft has closed, the Marine Management Organization (MMO) will consider the need for an Independent Investigation, they will then make a recommendation to the Secretary of State for Defra…Through the engagement of stakeholders, it is expected that most, if not all, issues will be dealt with throughout the plan preparation process”. The PINS advice consequently discouraged II by focusing on Para 13(2c) but ignoring the rest of the paragraph.

A key question in this research is when did the concept of independent investigation change from mandatory to discretionary and why? The review revealed that ‘A Marine Bill – A consultation document’ (Defra Citation2006) stated in para 8.94:

If a plan were to have some binding effect on regulatory decision making, then a more rigorous examination might be considered (…) Consideration would be needed as to whether there would be a need for further independent scrutiny of this kind for marine spatial planning, to test the plan, and to discuss competing or conflicting interests.

In the subsequent Defra consultation on ‘A Sea Change – A Marine Bill White Paper’ (Defra Citation2007), para 4.66 said “The planning body, or relevant ministers or departments would consider whether there was a need for a formal public examination or hearing on the plan, or parts of it. In making their decision, they would be required to have regard to the public response to the plan, the level of stakeholder involvement that there had already been in the preparation and drafting of the plan, and any other matters they consider relevant. It may be that some elements of this process could be similar to the Examination in Public that takes place within planning on land.” Furthermore, para 4.67 states “An independent expert or inspector could chair any public hearing. They would report on their findings to the relevant planning body, ministers and departments, who would then consider whether to amend the draft plan, as a result of the report, or other representations received during the consultation process, on doing so publishing their decision on the rationale behind any changes”.

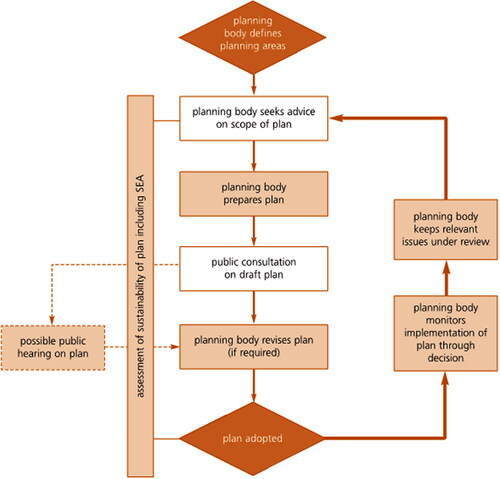

The iterative diagram for the process (see ), sets the “possible public hearing on plan” outside the central process of planning. Introduction of the word ‘possible’, makes this a discretionary feature; no longer necessary or mandatory.

Figure 2. Outline of planning process (Defra Citation2007).

The M&CA Bill (2008) Schedule 6 para 13 (1) referred to II and required that marine plan authorities “must consider appointing an independent person to investigate the proposals contained in that draft and to report on them.”

Another later publication, ‘Managing our Marine Resources: The Marine Management Organisation’ (Defra Citation2009) repeated the iterative marine planning process but reintroduced the word ‘possible’ and distinguished between MMO and SoS functions.

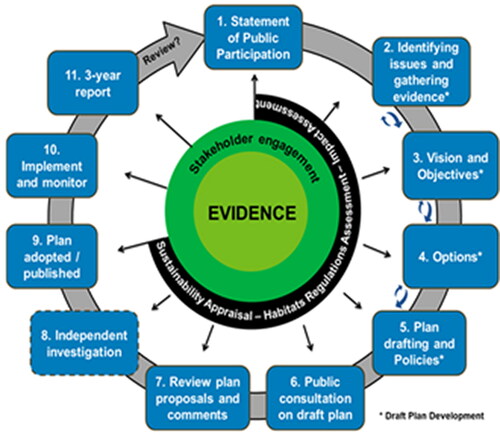

At the same time Defra was preparing for the establishment of the MMO. In doing so it produced a number of working documents, such as ‘A Description of the Marine Planning System for England’ (Defra Citation2011). This document contained a circular diagram of the marine planning process () from which the word ‘possible’ was omitted from the ‘Independent Investigation’ but the text made it clear that the II was dependent on the consideration of the SoS (para 4.45) and that the MMO should make such a recommendation. It identified the EiP as the terrestrial equivalent and anticipated that it would be conducted by a single inspector assisted by independent experts, should that be necessary (para 4.47). Again clear evidence the direction of travel was toward discretionary, not mandatory or necessary.

Figure 3. A description of the Marine Planning System in England (Defra Citation2011).

Para 4.48 states, “It is expected that when an II is required it will focus on specific issues/policies within the Marine Plan, to be defined by the Secretary of State based on the recommendations of the MMO, rather than the whole Plan.”

More recently, in a diagram contained within ‘Marine Planning and Development’ (MMO Citation2021), the II stage is shown within a dotted edged box, unlike other stages, indicating the optional, discretionary, nature of this element of the process ().

Figure 4. Marine planning and development (MMO Citation2021).

The review presented in this section has tracked the origins of II in the marine planning process and its inclusion in the MCAA. It traced its change of status from mandatory and necessary to discretionary through the key documents for England.

8. Comparison of independent investigation arrangements

The next stage of the research was to identify the existing arrangements for II across the UK and devolved administrations to understand why and when II was included ().

The UK MPS is laid before Parliament and does not require II (MCAA Citation2009, Sch 5). Marine plans for the English marine areas (MCAA Citation2009, Sch 6 para 13), the Scottish National Marine Plan, the Scottish Regional Marine Plans (Marine (Scotland) Act 2010, Sch 1 Para 11), the Welsh National Marine Plan (MCAA (Citation2009) Section 51 Sch 6) and the Marine Act (Northern Ireland) Citation2013 (Sch13) all allow for an II prior to adoption.

indicates that the only in Scotland has II been employed as part of the development process for a marine plan. Planning Scotland’s Seas was published for consultation in July 2013. The document, ‘set marine planning in context, presented key objectives and planning policies’ (PAS Citation2014) The consultation was standard in format and consisted of a series of general questions on the draft Plan, followed by questions on the different sector chapters. The process attracted 124 responses consisting of viewpoints and opinions from 108 organizations and 16 individuals (PAS Citation2014). The responses were first analyzed by Why Research, then Planning Aid for Scotland was appointed by Scottish Ministers as the independent investigator. It is interesting to note that two organizations formally requested that an II be conducted to consider their concerns: The Scottish Fishermen’s Association and the Clyde Fishermen’s Association.

The II focused its analysis on the key themes identified by Why Research and sought to establish how these issues have been addressed in the draft NMP, how effective these approaches have been, and if changes should be made for the production of the finalized document (PAS Citation2014). The II was undertaken by Planning Aid for Scotland as a desktop study, except for the particular attention given to the organizations who had requested the II, with telephone interviews being conducted. The report covered 12 themes and made 22 recommendations. Generally, it is supportive of the plan, stating, that it presents an ambitious and optimistic range of policies intended to maximize the benefits of the marine environment and the resources it contains’. It assesses the policies as ‘largely coherent and sound’ (PAS Citation2014), There was a general recommendation relating to facilitating comprehension through enhanced presentation.

Before the plan was adopted there was a further process of parliamentary scrutiny, including a debate in the Scottish Parliament. Scotland’s National Marine Plan was adopted in March 2015. An accompanying Modifications Report itemizes and explains how the plan had been amended to take into account the consultation responses, the II report and the Parliamentary scrutiny (Marine Scotland Citation2015).

9. Interview responses

The following summarizes the last part of the empirical research, the responses from the interviews. When asked why II has not been used in the majority of adopted plans, most interviewees agreed that there had been little demand from stakeholders for an investigation into draft marine plans, but the explanations of why that should be were varied. Commonly it was argued that plans had been written at a high strategic level (meaning there is limited detail included in policies) and consequently it would be difficult to formulate meaningful debate. More critically, this lack of specificity was also described as ‘aspirational’, ‘not robust’ and ‘lacking in evidence’.

Generally, it was argued that the culture in marine decision making is more conciliatory than terrestrial planning and that the avoidance of conflict motivated plan makers. Again, a variety of explanations of this culture were proposed from those who saw this as the influence of powerful stakeholders who did not wish to see their interests threatened. There were those who attributed this to the success of an open, front-loaded process in which issues were resolved in formative stages through extensive consultation early on in the planning process. Some went so far as to suggest that holding an II would be a sign of failure. Most agreed that marine planning is different from terrestrial and should not be constrained by procedures applicable to the latter.

A further set of arguments attributed the lack of investigation to governmental priorities. For example, it was argued that Ministerial scrutiny of plans and policies ensured sufficient examination and that the political priority was to “get plans done”. It was considered by at least one interviewee that Defra was resistant to the idea of II of the plans and what it saw as the unnecessary prolongation of the planning process. There is, it was said “little precedent for such a procedure in this branch of government.” Most critical was the view that MMO and others were under pressure to get plans done and the delay of II was not politically palatable.

One further view was that marine policies were low ranking in governmental priorities. For example, in determining nationally significant infrastructure proposals, marine policies only have to be taken into account, being less important than the policies enshrined in NPS, although this only applies to England and Wales.

Finally, a view that underpinned a number of responses, was that the marine planning system is still in its infancy, “early evolution” as one interviewee described it, and that future iterations of plans would be potentially more contentious and require independent examination through II. It was also noted that although these were the first iterations of statutory plans, in some instances these were building on previous non-statutory, or pilot, marine or coastal plans. These, in some instances, were met with initial skepticism or indifference. But the process of conciliatory front-loaded engagement with stakeholders has been seen to build trust and acceptance of the marine planning process. However, that was a marine planning process without the ‘threat’ of an inquiry hanging over it.

While some interviewees saw no potential benefit in II, most did. From the point of view of strengthening the planning process, many saw II as a means of making it more robust and increasing the legitimacy of the process. It was believed that policies that have been examined publicly and independently would provide greater clarity and improve both content and wording. II would give greater certainty to developers and act as a form of risk management to those who may otherwise fall foul of the consenting process. From the plan maker’s perspective, it was felt that II would increase stakeholder engagement and buy-in to the process. In addition, it would provide a further opportunity for public involvement and increase accountability to a process that has limited political input. More specifically, II was seen as a means of reducing the potential for Judicial Review of decisions in future. Some saw the benefits of II being more long-term, offering an opportunity to examine future plans as the marine planning system matures.

It was generally accepted that introducing II into the process of MSP would add both delay and financial cost. A common concern was that II would introduce an element of division to marine relationships, which is contrary to the culture. In any event, it was pointed out that the legislation only requires decision makers to “have regard” to the recommendations of the II. However, others suggested that the costs of not having II were currently being decanted elsewhere, and that having an investigation may not necessarily be divisive and could contribute to the consensual nature of plan-making. It was emphasized by one interviewee that holding an II should not be seen as sign of failure.

Participants were asked what form II should take if it were to be used. A small number of the interviewees with marine backgrounds were insufficiently familiar with the different forms of investigation of plan policies in terrestrial planning and consequently felt constrained in their replies. However, among those opposed to the use of II at least one felt that decisions on the appropriateness of a plan should be left to the government as it was their policies. Of those advocating II, there was a general acceptance that no specific terrestrial model should be transposed into the marine process, and that some form of bespoke or hybrid practice should be adopted. There was a variety of opinions on the desired characteristics of the procedure. Most felt that only selected topics and related policies should be examined in detail, that the style should be inquisitorial and non-adversarial in nature. Opinions were expressed that II should primarily be seen as a written process while others felt the focus should be the soundness of the plan.

A further point of interest that emerged from the interviews was whether there is evidence that having II of marine plans would actually make a difference? Perhaps the best examples of the argument in support of the view that II could have made a difference are to be found in the determination of applications for offshore windfarms off the English coast. The marine plans for England appear to accept the Crown Estate Round 3 allocations in all areas except where there had previously been a refusal of permission (e.g. Navitus Bay) or where potential developers had withdrawn interest (e.g. Atlantic Array and Celtic Array). It is speculation as to whether these sites would have appeared in regional marine plans, but the precedence elsewhere suggests they would. However, II of such plans would have identified the policy and practical obstacles to such allocations, and depending on the outcome of the II, could have provided more robust evidence for support of those locations, or for the identification of alternative sites.

In recent years, a number of offshore wind farm applications in locations identified in marine plans, accompanied by policy support, have also been subject to delay and opposition through Judicial Review, delayed decisions, or attracting recommendations for refusal from the Examining Authority (e.g. East Anglia One North, East Anglia Two, Norfolk Vanguard, Norfolk Boreas and Hornsea Project Three). II of the marine plans which identified these sites for development would have allowed for greater in-depth investigation of the merits of the sites, and in particular, the cumulative impact issues. Marine plans should resolve the question of which sites to prioritize for development, and assess their cumulative impact on environmental and social receptors in advance of applications for development. It is for these reasons that some of the interviewees (particularly those from users of marine plans) identified II as contributing to the risk management of future projects and that failure to undertake such investigations merely pushed problems into the future, resulting in Judicial Review or the failure of project proposals which impose unnecessary expense on all parties.

10. Discussion

This article has identified how the concept of II in the marine planning process was inherited from terrestrial planning as an integral part of the plan-making process. Our research reveals two further points of interest. Firstly, that in the process of developing marine planning, there is little evidence that the merits of II were ever discussed in-depth, or the presence of an II stage in the process ever questioned. Secondly, that the setting aside of II, as an integral part of marine plan formulation, seems to have occurred without any apparent justification.

The absence of II certainly makes life easier for plan-making bodies. They are thus excused the onus of presenting, justifying and defending the proposed policies of the draft plan from direct interrogation by interested parties and alternative evidence that may be presented by them. Defending a plan’s policies is not only onerous, but time consuming and costly. It is particularly difficult if the plan-making authorities have target dates by which plans must be complete. This was evident with that the last tranche of English marine plans that were completed concurrently to allow for publication simultaneously in 2021.

In early literature it was indicated that II would be part and parcel of MSP’s DNA. Yet in a publication issued by Defra (Citation2011) “A description of the marine planning system for England”, contains a section that highlights that the SoS is to consider, after the public consultation, whether there is a need for II to resolve outstanding issues. Though through engagement of, and facilitation between stakeholders, it is noted: “it is expected that most issues will be dealt with within the marine planning process. The intention is to avoid the need for an II.” (Defra Citation2011, 57). A clear nod to the aspirations of front-loading the planning system.

It would be fair to say that opinions from the interviews about the desirability and benefit of II in marine planning were divided. It would also be accurate to say that those who oppose the use of II tended to be those working in marine planning bodies. The support for II came mainly from terrestrial planners, consenting officers, consultants and advisers. There is clearly a cultural difference between those who are embedded in organizations with a marine planning responsibility and those outside. The marine planners interviewed regarded II as a mechanism that would induce delay, cost and potential conflict into what they would see as a process where differences are resolved by negotiation and mediation during the plan-making process. This is a culture that places conciliation above confrontation.

As well as cultural differences, marine planners asserted that planning for the marine environment is entirely different from the terrestrial environment. Clearly, there are differences in the natural environment, the three-dimensional nature of the marine (seabed, surface and column), the lack of administrative and ownership boundaries and the fact that there is no residential population. However, the process of planning by way of “survey, analysis, plan”, is applicable to many administrative tasks. Sometimes described as a technocratic, top-down approach, its principles underlie both terrestrial and marine plan-making. The II is part of the review element of such a process where policies arrived at through a logical and rational decision-making process are checked to ensure that they do not have unforeseen outcomes. For example, have the tradeoffs between different interests led to disproportionate and unfair outcomes for one or more parties affected by the plan?

Those outside marine planning bodies consider that inevitable conflicts of interest are avoided by generalized policies, high-level strategies and an obscure process of resolution during the consultation phases of plan-making. They would argue that the current approach merely postpones conflict and decants it elsewhere, to the consenting phase or to a Judicial Review. Those who see II as desirable consider it could bring a number of benefits to marine planning, including encouraging more detailed, robust and useful plans.

There appears to be no enthusiasm for II in either plan-making bodies or in the government departments that host those bodies. In fact, quite the opposite, there appears to be a collective hostility to this part of the marine plan process as originally envisaged and enshrined in legislation. This is supplemented by those who feel that marine plans (and the MPS) are lower order than other areas of policy, such as NPSs. That is not to say, however, that the policies of marine plans are ignored. Rather, it confirms previous findings that awareness by decision makers that the marine planning system is a plan-led system and the statutory requirement for all government bodies to take marine plans into account in decision making is limited (Slater and Claydon Citation2020). In regard to the impact of marine plan policies on consenting decisions, a planning lawyer advised that where policies have been adopted and independently examined, that they would carry greater weight in decision-making. However, even among those inside marine plan-making bodies, there is an acceptance, by some, that future plans may be subject to II and consequently how that should be conducted, is a valid question.

Furthermore, the view that marine plans (and the MPS) are lower order than other areas of policy expressed by interviewees could also be attributable to the proliferation of legislation, plans and policy documents that exist for the marine environment. Boyes and Elliot (Citation2014) “Ultimate Horrendogram” shows the complexity of 200 pieces of legislation having repercussions for marine environment policy and management. As noted above, the new marine planning system emerged at a time of seismic shifts in planning policy development across the UK. Decision makers were confronted with the NPS in England, the NPF in Scotland and a reform of the whole terrestrial planning system in Northern Ireland, an array of sectoral plans, as well as terrestrial development plans. This, combined with the negotiated nature of licensing decisions for the marine environment, suggests that marine plan policies are often of limited value. This raises questions, again, concerning how the legitimacy of marine plans and their status in practical and real-life situations can be enhanced. Could the incorporation of II as part of the process achieve this? This and other reflections are discussed in the final section of this paper.

11. Reflections and conclusions

The origins of inquiries and their adoption in spatial planning systems go back to the nineteenth century. That history and experience influenced those who, much more recently, sought to translate the practice into marine planning, as one of the most recent developments in spatial planning. Consequently, the guidance that eventually emerged and the documents that shaped that guidance have been investigated to plot the trajectory of advice that led to the adoption of an optional approach to II.

In short, unlike its terrestrial counterpart, II has been articulated as a discretionary requirement in MSP. Findings from the qualitative interviews illuminated three key potential reasons behind this.

First, while general support for II was mooted by the majority of interviewees, there is also a strong desire not to impose additional regulatory burden and avoid adversarial procedures in any form. For some, such concerns for conciliation render II as a sign of failure, further intensifying negative connotations associated with II due, in part, to previous terrestrial experience and/or renowned cases. Indeed, whilst the evolution of MSP in the UK has been informed by terrestrial land use planning there are important contextual and cultural differences that necessitate much greater appreciation. Critically, knowledge and understanding of established terrestrial planning procedures by marine planners (and vice versa) cannot be assumed. Terrestrial planners will have received education and training on the legal aspects of planning, as part of a planning degree; as mandated by professional bodies who accredit programmes, such as the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI). In contrast, those undertaking marine planning often come from a scientific background with skills in areas such as Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and environmental assessment or marine biology. Traditional notions of “scientific authority” in the marine environment stem from a technocratic, rational approach to defining problems.

Yet, in more recent years, “marine social science” has been recognized as an equally important and robust body of knowledge and scientific authority (Bennett Citation2019; Shah Citation2020; Ritchie and McElduff Citation2020). This opens up new (multi-disciplinary) arenas of exploration, education and debate which may serve to combine with and rationalize marine knowledge sets and skills. It is clear that marine social science has picked up on many themes, such as the importance of good governance and the need for transparency and early and meaningful engagement throughout the entire planning process. However, the increased public awareness of marine issues, as an environmental crisis, is raising the profile of people-place relationships and strong attachments to place (Kaur and Chahal Citation2018; Kratzig and Warren-Kretzscmer Citation2014). Similarly, there are now much higher levels of involvement in the management of the marine environment which is promoting an increased sense of “marine citizenship” (McKinley and Fletcher Citation2010; Jefferson et al. Citation2015; Potts et al. Citation2016).

Second, questions were raised as to the current value being placed on marine plans and the extent to which they are being utilized as part of the decision-making process. For example, in the National Infrastructure Planning System in England and Wales, the policies of marine plans need only to be “taken into account” in determining applications for major infrastructure proposals whereas decisions must be “made in accordance” with the policies of the NPS.

In Scotland, the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 establishes a hierarchy of plans as it requires that the national marine plan and regional marine plans must be in conformity with any MPS and a regional marine plan must also be in conformity with any national marine plan currently in effect (Marine (Scotland) Act 2010s.6). The MPS is, therefore, at the top of the hierarchy, followed by the Scottish National Marine Plan, with regional marine plans, created by regional marine planning partnerships being at the bottom of the hierarchy. This has established a top-down level of conformity for marine plans in Scotland, but also that Scotland has had in existence a marine plan since the national marine plan was adopted in 2015. Since then, all public authorities in Scotland have been required to take all relevant authorization or enforcement decisions in accordance with the appropriate marine plans, unless relevant considerations indicate otherwise. Yet, the research indicates that this legal requirement to utilize marine plans as key criteria to be followed in making marine decisions was not widely recognized or understood as a comprehensive requirement to take into account marine plans. It may be that the plan-led system is a concept that is not readily understood and embraced by those making decisions for the marine environment to date. It is considered that the use of II would not only test the policies of marine plans but would also enhance their profile. The testing mechanisms would enhance their value by decision makers and contribute to ensuring that they were more widely understood as part of marine decision-making processes.

Third and perhaps most compelling, this research, particularly highlighted in the interview responses, has shown that the marine planning system is widely considered not to be working effectively. For example, in relation to cumulative impact, it requires to incorporate processes that assess strategic issues as a whole. A vicious circle of ineffective or vague policies, having little impact on marine decisions, is leading to uncertainty for stakeholders and communities, perpetuating a lack of regard for the system. A necessary supplementary question to consider is whether II would improve decision making in the marine planning system? Put succinctly, this paper has found that the relatively novel status of marine planning across the UK means it is too early to tell. MSP was set up to address marine issues in a holistic and integrative manner, to be a plan-led system. It was also set up to include II to ensure openness, fairness and impartiality. A lack of appetite or familiarity with the process is, in itself, not a valid argument against utilizing II. Critically, as MSP matures and new iterations of marine plans are produced, it is likely that II will form a more integral part of a transparent, open and accountable marine planning process in the future as was anticipated earlier in the legislation. In this regard, the current attitudes toward II, and failure to incorporate procedures for II in marine policy and plans, creates issues for the future, and warrants further investigation.

There are real opportunities to utilize II in a positive way. The plan as a whole may be improved in terms of coherence and effectiveness, if it is subject to independent scrutiny, while individual policies could be sharpened up, made more relevant and effective. At the same time, exposure of the plan to public gaze would ensure greater appreciation of its scope and purpose, and more particularly bodies (both public and private) with responsibilities for the marine environment and its future, are more likely to receive buy-in to the outcome if they have been involved in shaping the plan. An II and potential public hearing is likely to heighten expectations and performance of all involved.

This research has reviewed the place of II in the marine planning process through analysis of documents extending back to 2001 and eliciting the views of experts in the area. It is clear that II was expected to be a key part of the marine planning process. It could be argued that the lack of utilization of II has built up trust and thus facilitated the delivery of the first tranche of marine plans. The future use of II as marine plans mature, however, could enhance the quality and effectiveness of marine plans and marine planning decisions. This is certainly a prize worth pursuing, as the focus on the oceans and sea space around the UK becomes more contested and controversial.

The research has established a distinction between the views of those engaged in marine plan-making, and those whose involvement was in shaping the legislation and advice, and/or may now be observers or external participants in marine decision making. Generally, the former are unpersuaded of the value of II, while the latter favor its use. This could lead to the conclusion that in marine planning practice the role of plans and policies is primarily aspirational. This research cannot conclude definitively on this assertion, which needs to be addressed when more evidence is available, but if there is any truth in it, then the next relevant question is “does this matter?”

Dislcosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baker, M., J. Coaffee, and J. Sherriff. 2007. “Achieving Successful Participation in the New UK Spatial Planning System.” Planning Practice and Research 22 (1): 79–93. doi:10.1080/02697450601173371.

- Baker, M., P. Roberts, and R. Shaw. 2003. Stakeholders Involvement in Regional Planning. London: Town and Country Planning Association.

- Bennett, N. J. 2019. “Marine Social Sciences for the Peopled Sea.” Coastal Management 47 (2): 244–252. doi:10.1080/08920753.2019.1564958.

- Berkes, F., T. P. Hughes, R. S. Steneck, J. A. Wilson, D. R. Bellwood, B. Crona, C. Folke, et al. 2006. “Globalization, Roving Bandits, and Marine Resources.” Science 311 (5767): 1557–1558.

- Boyes, S. J, and M. Elliot. 2014. “Marine Legislation: The Ultimate ‘Horrendogram’: International Law, European Directives and National Implementation.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 86 (1–2): 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.06.055.

- Boyes, S. J., and M. Elliot. 2015. “The Excessive Complexity of National Marine Governance Systems: Has This Decreased in England Since the Introduction of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009?” Marine Policy 51: 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.07.019.

- Bull, S. K., and D. Laffoley. 2003. Networks of Protected Areas in the Maritime Environment (Report for the Review of Marine Nature Conservation and the Marine Stewardship Process Stakeholder Workshop, London, 19 June 2003), (English Nature research report, no. 537), Peterborough: English Nature.

- Campbell, H., and R. Marshall. 2000. “Public Involvement and Planning: Looking beyond the One to the Many.” International Planning Studies 5 (3): 321–344. doi:10.1080/713672862.

- Canning, R., 2003. “The Elements of Marine Spatial Planning: Key Drivers and Obligations.” In Spatial Planning in the Coastal and Marine Environment: Next Steps to Action, edited by R. Earll, CoastNET conference SOAS, University of London.

- Cicin-Sain, B. 1992. “Multiple Use Conflicts and Their Resolution: Toward a Comparative Research Agenda.” In Ocean Management in Global Change, edited by P. Fabbri, 280–307. London: Elsevier.

- Cowell, R., and S. Owens. 2006. “Governing Space, Planning Reform and the Politics of Sustainability.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 24 (3): 403–421. doi:10.1068/c0416j.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2002. Safeguarding Our Seas: A Strategy for the Conservation and Sustainable Development of Our Marine Environment. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2002. Seas of Change: Consultation Paper. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2006. A Marine Bill: A Consultation Document. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2007. A Sea Change: A Marine Bill White Paper. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2008. The Marine and Coastal Access Bill. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2009. Managing our Marine Resources. London: Defra.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2011. A Description of the Marine Planning System for England. London: Defra.

- Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA). 2018. “Draft Marine Plan for Northern Ireland.” https://www.daera-ni.gov.uk/articles/marine-plan-northern-ireland

- Douvere, F. 2008. “The Importance of Marine Spatial Planning in Advancing Ecosystem-Based Sea Use Management.” Marine Policy 32 (5): 762–771. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2008.03.021.

- European Parliament. 2008. Directive 2008/56/EC of the establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive) OJ L164/19.

- Feeny, D., S. Hanna, and A. F. McEvoy. 1996. “Questioning the Assumptions of the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ Model of Fisheries.” Land Economics 72 (2): 187–205. doi:10.2307/3146965.

- Flannery, W., and G. Ellis. 2016. “Marine Spatial Planning: Cui Bono.” Planning Theory and Practice 17 (1): 122–128.

- Flannery, Wesley, Geraint Ellis, Geraint Ellis, Wesley Flannery, Melissa Nursey-Bray, Jan P. M. van Tatenhove, Christina Kelly, Scott Coffen-Smout, Rhona Fairgrieve, Maaike Knol, Svein Jentoft, David Bacon and Anne Marie O’Hagan. 2016. “Exploring the Winners and Losers of Marine Environmental Governance/Marine Spatial Planning: Cui bono?/“More than Fishy Business”: Epistemology, Integration and Conflict in Marine Spatial Planning/Marine Spatial Planning: Power and Scaping/Surely not all Planning is Evil?/Marine Spatial Planning: A Canadian Perspective/Maritime Spatial Planning - “Ad Utilitatem Omnium”/Marine Spatial Planning: “It is Better to be on the Train than Being Hit by It”/Reflections from the Perspective of Recreational Anglers and Boats for Hire/Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Renewable Energy.” Planning Theory and Practice 17 (1): 121–151. doi:10.1080/14649357.2015.1131482.

- HM Government, Northern Ireland Executive, Scottish Government, Welsh Assembly Government. 2011. National Marine Policy Statement. London: The Stationary Office.

- HM Government. 1969. People and Planning: Report on the committee on public participation in planning (Skeffington Committee). London: The Stationary Office.

- HM Government. 2009. Marine and Coastal Access Act. London: The Stationary Office.

- HM Government. 2011. Localism Act. London: The Stationary Office.

- Halpern, B. S., S. Walbridge, K. A. Selkoe, C.V. Kappel, F. Micheli, C. D’Agrosa, J. F. Bruno., et al. 2008. “A Global Map of Human Impact on Marine Ecosystems.” Science 319 (5865): 948–952. doi:10.1126/science.1149345.

- Healey, P. 1997. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Macmillan.

- Jay, S. 2010. “Planners to the Rescue: Spatial Planning Facilitating the Development of Offshore Wind Energy.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 60 (4): 493–499. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.11.010.

- Jefferson, R. L., I. Bailey, D. d′A Laffoley, J. P. Richards, and M. J. Attrill. 2015. “Public Perceptions of the UK Marine Environment.” Marine Policy 43: 327–337. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2013.07.004.

- Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC). 2002. The Irish Sea Pilot. Report to Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs by JNCC. Peterborough: JNCC.

- Kaur, A., and H. S. Chahal. 2018. “The Role of Social Media in Increasing Environmental Awareness.” Journal of Arts, Science and Commerce 9 (1): 19–27. doi:10.18843/rwjasc/v9i1/03.

- Kidd, S., and G. Ellis. 2012. “From the Land to Sea and Back Again? Using Terrestrial Planning to Understand the Process of Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 14 (1): 49–66. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2012.662382.

- Kratzig, S., and B. Warren-Kretzscmer. 2014. “Using Interactive Web Tools in Environmental Planning to Improve Communication about Sustainable Development.” Sustainability 6: 236–250.

- Leach, S., and M. Wingfield. 1999. “Public Participation and the Democratic Renewal Agenda: Prioritisation or Marginalisation?” Local Government Studies 25 (4): 46–59. doi:10.1080/03003939908433966.

- Lindblom, C. E. 1968. The Policy-Making Process. Prentice-Hall Foundations of Modern Political Science Series. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Lord Chancellor’s Department. 1957. Committee on Administrative Tribunals and Enquiries Report. Franks Committee.

- Marine Management Organisation. 2021. Marine Planning and Development. Newcastle: Marine Management Organisation.

- Marine Scotland. 2015. Scotland’s National Marine Plan Modifications Report. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Marine Scotland. 2015. Scotland’s National Marine Plan: A Single Framework for Managing Our Seas. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

- Marine Spatial Planning Project Consortium. 2006. Marine Spatial Planning Irish Sea Pilot, London: Marine Spatial Planning Project Consortium.

- McEldowney, M., and K. Sterrett. 2001. “Shaping a Regional Vision: The Case of Northern Ireland.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 16 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1080/02690940010016949.

- McKinley, E., and S. Fletcher. 2010. “Individual Responsibility for the Oceans? An Evaluation of Marine Citizenship by UK Marine Practitioners.” Ocean and Coastal Management 53 (7): 379–384. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.04.012.

- Morphet, J. 2005. “A Meta-Narrative of Planning Reform.” Town Planning Review 76 (4): iv–ix.

- Murray, M., and J. Greer. 2002. “Participatory Planning as Dialogue: The Northern Ireland Regional Strategic Framework and Its Public Examination Process.” Policy Studies 23 (3): 191–209. doi:10.1080/0144287022000045984.

- Nellemann, C., S. Hain, and J.E. Alder. 2008. In Dead Water: Merging of Climate Change with Pollution, Over-Harvest, and Infestations in the World’s Fishing Grounds. Arendal: UNEP/GRID-Arendal.

- Northern Ireland Assembly. 2013. Marine Act (Northern Ireland), Belfast.

- O’Riordan, T., R. Kemp, and M. Purdue. 1988. Sizewell B: An Anatomy of the Inquiry. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Peel, D. and M. G. Lloyd. 2004. “The Social Reconstruction of the Marine Environment: Towards Marine Spatial Planning?” The Town Planning Review 75 (3): 359–378. doi:10.3828/tpr.75.3.6.

- Planning Advisory Group. 1965. The Future of Development Plans. London: HMSO.

- Planning Aid for Scotland (PAS). 2014. Report to Scottish Ministers, Independent Investigation of Proposals in the Draft National Marine Plan.

- Planning Inspectorate. 2014. Marine Plans: Independent Investigations. London: Planning Inspectorate.

- Potts, T., C. Pita, T. O’Higgins, and L. Mee. 2016. “Who Cares, European Attitudes towards Marine and Coastal Environments.” Marine Policy 72: 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.012.

- Reeves, D., and K. Burley. 2002. “Public Inquiries and Development Plans in England: The Role of Planning Aid.” Planning Practice and Research 17 (4): 407–428. doi:10.1080/02697450216352.

- Ritchie, H., and G. Ellis. 2010. “A System That Works for the Sea’? Exploring Stakeholder Engagement in Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 53 (6): 701–710. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.488100.

- Ritchie, H., and W. Flannery. 2017. “Advancing Integrated Marine Spatial Planning in Northern Ireland.” In Planning Law and Practice in Northern Ireland, edited by S. McKay and M. Murray, 177–190. London: Routledge

- Ritchie, H., and L. McElduff. 2020. “The Whence and Whither of Marine Spatial Planning: Revisiting the Social Reconstruction of the Marine Environment in the UK.” Maritime Studies 19 (3): 229–240. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00170-6.

- Scottish Executive. 2006. Marine (Scotland) Act. Edinburgh: Scottish Parliament.

- Shah, H. 2020. “Global Problems Need Social Science.” Nature 577 (7790): 295–295. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00064-x.

- Sheppard, A., D. Peel, H. Ritchie, and S. Berry. 2017. The Essential Guide to Planning Law: Decision-Making and Practice in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Slater, A. M., and J. Claydon. 2020. “Marine Spatial Planning in the UK: A Review of the Progress and Effectiveness of the Plans and Their Policies.” Environmental Law Review 22 (2): 85–107. doi:10.1177/1461452920927340.

- Tafon, R., B. Glavovic, F. Saunders, and M. Gilek. 2021. “Oceans of Conflict: Pathways to an Ocean Sustainability PACT.” Planning Practice and Research. 37 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1080/02697459.2021.1918880.

- Tyldesley, D. 2004. Making the Case for Marine Spatial Planning in Scotland, Edinburgh, RSPB, Scotland and RTPI in Scotland.

- UK Government. 2001. Interim Report of the UK Government. Review of Marine Nature Conservation Working Group.

- UNESCO – IOC. 2021. MSP Global: International guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning, DG Fisheries and Maritime Affairs

- Worm, B., E. B. Barbier, N. Beaumont, J. E. Duffy, C. Folke, B. S. Halpern, J. B. C. Jackson, et al. 2006. “Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 314 (5800): 787–790. doi:10.1126/science.1132294.

- Worm, B., and H. K. Lotze. 2021. “Marine Biodiversity and Climate Change.” In Climate Change, edited by T. M. Letcher, 445–464. Amsterdam: Elsevier.