Abstract

Calls for transformational adaptation are increasing. Government authorities, expected to lead adaptation, are in the difficult situation of changing a governance system from within. This demands a capacity for critical reflection among civil servants involved. Adopting a Social Practice Theory approach, we argue this capacity must be understood as emerging in practice, not simply held by individuals. Empirically, we focus on a central network of government authorities in Sweden’s adaptation governance, and identify assumptions and routines guiding their meaning making process. We focus on how situations of contestation are dealt with to explore the practice’s capacity to facilitate critical reflection. We show how a focus on efficient information transmission and an assumption of incremental adaptation as sufficient leads their practice to play down the consequences of the climate crisis. A practice approach suggests interventions to the group level in order to create joint critical reflection, necessary for enabling transformational adaptation.

1. Introduction – critical reflection as a basis for transformational practices

The 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement is slipping away, and it is still highly uncertain if staying below 2 °C warming will be achieved (Anderson, Broderick, and Stoddard Citation2020; Böhm and Sullivan Citation2021; Roelfsema et al. Citation2020). The risk of crossing tipping points and unleashing uncontrollable cascading effects increases with every ton of CO2 released into the atmosphere (AghaKouchak et al. Citation2020; Lenton et al. Citation2019; Milner et al. Citation2017). This has raised serious doubt about the effectiveness of the reactive and incremental approach to adaptation that has dominated governments’ polices and strategies (Kates, Travis, and Wilbanks Citation2012; Nightingale et al. Citation2020), and has led to increased calls to go beyond such approaches towards transformational adaptation (Fazey et al. Citation2018; Fook Citation2017; Jacob and Ekins Citation2020).

The call for transformational adaptation places particular focus on government authorities, as they have a significant role to play in leading adaptation (Keskitalo, Juhola, and Westerhoff Citation2012; Köhler et al. Citation2019; Oberlack Citation2017; Scott and Moloney Citation2022), and ultimately contribute to a sustainable society able to deal with the climate crisis. These authorities are, however, part of systems that have led to the situation we as a society now find ourselves in. The call for transformational adaptation, therefore, puts government authorities tasked with leading the process in the difficult position of being expected to change a system they themselves are part of.

Changing a system from within presupposes the capacity of those involved to create work situations that encourage them to critically examine organizational routines and identify shortcomings of their own approaches. They need to be prepared to reflect upon, challenge and discard routines, assumptions and mind-sets that keep them in the status quo (Göpel Citation2016; Grin Citation2020; Löf Citation2010; O’Brien Citation2012; Rietig Citation2019; Gerlak, Heikkila, and Newig Citation2020). It follows that changing the current governance system, a crucial part of achieving transformational adaptation (Ulibarri et al. Citation2022), demands a capacity for critical reflection (Grin Citation2020; Schön Citation1983). In order to understand the potential for transformational adaptation, responsible actors in adaptation governance, such as government authorities, need to be scrutinised for this particular capacity (Paschen and Ison Citation2014).

In this paper, we build on this reasoning about the need for critical reflection and changing mind-sets in order to create transformational adaptation. Further, we argue that this capacity cannot be regarded as a capacity simply held or not held by individual civil servants. It must be explored in the social context, or the practice, in which civil servants responsible for adaptation are embedded (Hoffman and Loeber Citation2016). Using Social Practice Theory, we focus on the “practice” as the unit of analysis, instead of the civil servants as isolated individuals. Social Practice Theory views “practice” as a situated patterning of behaviour (speech, body language, even thoughts) that, through taken for granted assumptions and routines, guide its performers towards a shared purpose. However, even if a practice shapes the assumptions and behaviour of its performers, it remains open-ended to the extent that subversive acts carried out by the performers themselves, can challenge assumptions and routines (Behagel, Arts, and Turnhout Citation2019; Butler Citation1990; Nicolini Citation2012).

We apply these insights to explore the potential of a central government actor in Sweden, the National Network for AdaptationFootnote1, to initiate and maintain transformational approaches to adaptation. Sweden is a particularly interesting case as a country with high ambitions in sustainability and high adaptive capacity (Metzger et al. Citation2021; Sarkodie and Strezov Citation2019) and where government authorities and their civil servants have a high degree of independence to perform their given tasks (Pierre Citation2020). It can, thus, be described as a “most likely” case (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) for transformational adaptation led from inside the system, i.e. by civil servants.

To explore the Network and its practice we have followed it over the course of two years, through participant observations combined with interviews and document analysis. This has allowed us to delve into how the ongoing interaction forms and reproduces the sensemaking process, routines and assumptions that maintain the Network’s approach to adaptation. Further, it has allowed us to identify openings for critical reflection and change induced by the members of the Network, and to discuss the Network’s potential and limitations as a catalyst for transformational adaptation in Sweden. Specifically, we ask: How does the Network’s practice make sense of adaptation and its role in the governance regime, and what distinguishable routines and assumptions reproduce this sensemaking? To explore the space for, and openness to, critical reflection in the practice we ask: How are questions and critique related to established ways of making sense of adaptation, coming from the members themselves, dealt with?

The main contribution of this paper is to demonstrate the usefulness of understanding potentials for transformational adaptation and the necessary mind-shift required through a Social Practice Theory approach. Based on our findings, we discuss how such an approach helps to focus attention beyond individual capacity to more promising interventions, targeting situated and shared sensemaking to move towards transformational adaptation.

Our approach means that we explore communication and other forms of interaction as a co-construction of meaning in the context where it is carried out. In our case, this context is the Network’s practice created by the participating civil servants engaged in climate change adaptation in Sweden. A practice approach contributes to this special issue by highlighting how meaning making is context dependent, as assumptions, priorities and identities change depending on what practice an individual perceives themselves to be in. Our study further contributes to showing how meaning making processes around key ideas, such as adaptation, link to action. More specifically we show how assumptions on what needs to be done and why, are (re)produced and negotiated in practice, in turn shaping the space and limitations for how central actors respond to one of the greatest sustainability challenges of our time, the climate crisis.

We introduce our empirical context and the Network in the next section (Section 2), before moving on to explaining our theoretical framework (Section 3), followed by descriptions of methods and materials (Section 3). We then return to the Network and describe its main activities and arenas for interaction (in Section 5), before moving on to analysis (Section 6), and concluding discussion (Section 7).

2. Empirical background: the emergence of the national network for adaptation

Adaptation has primarily been seen as a largely apolitical and technical planning issue (Eriksen, Nightingale, and Eakin Citation2015; Remling Citation2019) and Sweden is no exception in this regard. As a consequence, municipalities in charge of planning land use have been seen as the natural level for adaptation (Granberg et al. Citation2019; Hjerpe, Storbjörk, and Alberth Citation2015). This has, however, led to a void at the national level (Massey et al. Citation2015). This lack of political leadership is not unique to Sweden either. A common response to this void has been to find new types of governance approaches, often through the creation of networks (Broto Citation2017; Di Gregorio et al. Citation2019; Ulibarri et al. Citation2022). The Network we have followed started as such a response.

The Network began with a few national government authorities coming together in 2005 to share knowledge and start capacity building. Adaptation was seen as increasingly important by these members, but there was a sense of lacking regulation, guidance and knowledge (National Network for Adaptation Citation2019). The central activity of the Network in its early and more informal state was a website, where activities and events related to adaptation were published (Keskitalo in Keskitalo Citation2010, 205).

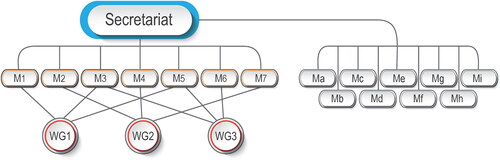

In 2016, the Network was formalised and reshaped into the National Network for Adaptation, as the members wanted to use the network constellation “to do something more” (Interview 1). This formalisation saw the Network take on a more ambitious purpose, not just to build the competence of its members, but to work more with outreach, strengthening other actors in society and work towards improvements in regulations and instruments (National Network for Adaptation Citation2018). The knowledge sharing and capacity building among the participating authorities was still the main activity, but a coordinated push for legislation was now initiated as well (Interview 1). With this restructuring of the Network, the Swedish Metrological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) offered to take on the role of secretariat (leading the meetings, taking notes, hosting servers, etc.), giving them a central role in the reshaped Network. For a representation of the Network’s structure, see .

Figure 1. The organisational structure of the Network. “M” for Member organisation. “WG” for Working Group. The right side represents the expansion of the Network following the new legislation in 2019.

Finally, at the beginning of 2019, the national legislation on adaptation, which members of the Network and the Network itself had been pushing for, took effect. The new legislation meant that 53 authorities were charged with planning for, and regularly reporting, their work with adaptation (Ministry of the Environment Citation2018). The Network expanded to include the newly charged authorities. With the new legislation and the expansion of the Network the explicit purpose was slightly revised to read:

“the purpose of the network is to contribute to the development of a long-term sustainable and robust society that actively meets climate change by reducing vulnerability and taking advantage of opportunities” (National Network for Adaptation Citation2019, 3, authors’ translation from Swedish).

3. Theory: understanding adaptation governance practice from within

Research focusing on the contribution of state actors in developing transformational adaption approaches is mainly discussed in governance literature. This literature covers questions related to the conditions for institutional innovations to open up for changes (Heikkila and Gerlak Citation2019; Patterson and Huitema Citation2019), and coordination between different government levels to make use of synergies (Clar Citation2019; Howes et al. Citation2015). In addition, many scholars emphasize that governing transformational change requires transformation of the governance systems themselves (Termeer, Dewulf, and Biesbroek Citation2017) and show an increasing interest in learning as crucial for deeper system shifts initiated from within (Gonzales-Iwanciw, Dewulf, and Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen Citation2020). However, so far research has, with few exceptions (see e.g. Metzger et al. Citation2021; Wamsler et al. Citation2020), focused on methodological approaches limited to outside assessment of governance actors’ efforts and achievements with adaptation (cf. Baker et al. Citation2012; Glaas and Juhola Citation2013; Owen Citation2020; Bauer, Feichtinger, and Steurer Citation2012). This has led to calls for studies that manage to gain in-depth understanding of adaptation governance and the situated meaning making of governance actors (Denton and Wilbanks Citation2014; Patterson Citation2021). Our study is a direct response to this call by taking a Social Practice Theory approach that allows us to study the potential for transformational adaptation from within a governance setting.

3.1. Using social practice theory to identify potentials for change

A key characteristic of Social Practice Theory is to view “practice” as the unit of analysis. This means that agency and structures are always seen in relation to, and even as a product of, the practice in focus (Arts et al. Citation2014). Agency is thus always situated (Bevir Citation2005) and structures are only relevant to the extent that they are made relevant in the specific practice. This view allows for a fine-grained analysis of how stability is “achieved” and how change can be initiated, since neither stability nor change are external to the analysis (Nicolini Citation2012).

We understand practices as shared and routinized ways of making sense and acting performed by knowledgeable actors that are historically, socially and materially situated; Practices have normative dimensions, implying that they guide the participants in how to act and in what is seen as normal and or acceptable (Birtchnell Citation2012; Nicolini Citation2017; Spaargaren, Lamers and Weenink Citation2016).

The Network and its activities can fruitfully be understood as a practice. To develop understanding of the Network’s practice, and thereby discuss its potential and limitations to contribute to transformational adaptation, we have chosen one concept to capture its stability, “the logic of practice”, and another to capture deviations from this stability as openings for change, “performativity”.

3.2. Analytical Concepts: Logic of practice and performativity

3.2.1. Logic of practice

We utilise Bourdieu’s (Citation1990) concept “logic of practice”, to explore the organizing principles of the activities taking place in the Network. This logic “is not that of the logician” (Bourdieu Citation1990, 86), but rather the logic that guides what makes sense for members of a practice to perceive, think, say and do (and not). A practice, and the logic that guides it, activates and reproduces certain “routine behaviour and collective sense-making” (Arts et al. Citation2014, 6). Moreover, a practice is always practical in the sense that it has a purpose. The logic of the practice thus comprises a normativity, as it carries assumptions on how members of a practice ought to (re)act and make sense of tasks at hand in order to fulfil its purpose. For Bourdieu (Citation1990) this “ought to” means that practices contain regularities and continuation, guiding which ways of making sense and act are regarded as “correct” given the situation. The correctness is seldom explicit and hardly anything that the members consciously relate to. Rather it is hidden behind routines, norms and assumptions that newcomers to a practice need to “learn” in order to be accepted as full members (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). Focusing on the logic of the Network’s practice, we capture the routines, norms and assumptions that govern its approach to adaptation.

3.2.2. Performativity

The logic of a practice carries a normativity that guides how its members ought to make sense of, and act upon, tasks to fulfil its purpose. This prompts a “correct” reaction to a given situation. For example, a raised hand during a lecture usually prompts the lecturer to the “correct” response of pausing the presentation to answer the question. However, there are also actions that are seen as acceptable in the sense that they do not conflict with the opportunities to meet the given purpose of the teaching practice. For instance, the lecturer could acknowledge the raised hand, but state: “questions will be answered after the presentation”. In this example, the purpose of presenting is not compromised in either of the responses. If the lecturer, on the other hand, acknowledges the raised hand and invites the student to speak and the student expresses a wish to use more time for discussion and less for listening to monologues by the lecturer, the student challenges the particular teaching norm. The lecturer could shut down the suggestion by responding: “No, I have not planned for that”. Alternatively, the lecturer could open up the practice by inviting the students to discuss the suggestion.

The examples above illustrate how tolerance for irregularities of a practice opens up for a multitude of acceptable actions to fulfil its purpose, implying that a practice is, in principle, always open to change through the dialectical relationship between the logic of practice and its performance (Higginson et al. Citation2015; Westberg and Waldenström Citation2017).

To capture this openness analytically we use “performativity”. We regard every action as performative since it either reproduces the norm (or the “ought to”), or is subversive, meaning it challenges what is expected in the practice (Butler Citation1990). If an action does neither it means that the initiated members of the practice do not recognize it as a meaningful action in the practice (Salih Citation2007). Crucially, “performativity” assumes a degree of improvisation and creativity, which allows for changing practices from within (Behagel, Arts, and Turnhout Citation2019).

In our analysis, we focus on subversive performative acts to understand when and how members of the Network’s practice deviate and challenge norms, routines and taken for granted assumptions about what to do and why. This means that we see subversive performative acts as interactions challenging the logic of the practice. Such situations also highlight how these deviations are responded to by other members of the practice and, thereby, the openness to the change implied by the challenge of the subversive act.

3.2.3. Applying “logic of practice” and “performativity”

We use “logic of practice” to answer the first research question. The concept captures what assumptions and routines steer the practice, and how the Network makes sense of key ideas, e.g. adaptation, and of its own role in the Swedish climate change adaptation governance regime. We need to understand the logic of the Network’s practice in order to also be able to identify deviations and disruptions. Subversive performative acts cause disruptions, and it is these disruptions from the routines that can offer openings for reflection. Answering our second research question, we focus on these situations of contestation. We explore the openness and potential of the practice to take these challenges as opportunities to reflect on routine ways of thinking and acting, in order to be able to discuss the Network’s capacity to enable and contribute to transformational adaptation. This means that we view critical reflection as accomplished jointly in the practice: when successful it is enabled by the practice, initiated by a subversive performative act and fulfilled through acknowledging responses by the members.

4. Methods and materials

In this section, we start by explaining why Sweden was chosen as a context for our case. This is followed by a description of the types of data that we generated and how it was analysed. In Section 5 we return to our case, the Network, and describe their arenas for interaction in more detail.

Our argument for choosing Sweden is twofold. First, as described in the introduction, the circumstances for transformational adaptation led by government authorities are more likely in Sweden than in many other countries, which makes Sweden a “most likely” case (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Second, the Social Practice Theory approach we adopt in this study demands familiarity with the broader social context in which the cases under study unfold. As is implied in the theory section, it also demands developed understanding of the language in use (including body language) in order to be at its most effective. Since we (the authors) are based in Sweden the choice of Sweden as a case is methodologically relevant.

4.1. Data generating methods

Drawing on a range of methods used in ethnographic studies, such as participant observation, interviews and document analysis (Crang and Cook Citation2007), we generated a rich material following the Network between autumn 2018 and spring 2020. During this period, the first author participated in all the Network’s meetings, both the physical and digital. The second author was present at the majority of these gatherings. All meetings were audio recorded and additionally individual field notes where taken. Concluding each participatory observation we had a short joint reflection, alternatively a debriefing by the first author to the second author. When we gained access as observers to the meetings, we were also added to the Network’s email list. It is from this list and the associated website that we have gathered the documents analysed in this study.

During the same period, semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with members of the Network. The interviews focused on the informants’ view on the Network and its value and role in the Swedish adaptation governance regime, including their experiences of being members (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2015). Five were conducted via a videoconference program and the remaining three in person. We purposively selected interviewees (Silverman Citation2014) among members that we perceived as dominant in shaping the Network’s practice. These members were particularly vocal in meetings, successful in getting projects funded, and or represented authorities charged with specific responsibilities by the government. All interviews were recorded, transcribed by two research assistants working with an audio-to-transcript software, and the transcripts were finally checked by the interviewer. To keep the informants anonymous, we are not naming them or the authorities they represent in the text. Instead, we present a list of all members in the Appendix (online supplemental material).

4.2. Types and quantities of data used

The material we generated includes recordings and notes from four physical meetings (M1-M4), one virtual meeting (VM1, rearranged due to the Covid-19 pandemic), four phone meetings (PM1-PM4), two working group meetings (WGM1-WGM2) and eight interviews (I1-I8). In total, our material consists of approximately 60 recorded hours (12 h of interviews and 48 h of participatory observations).

The documents included in the material consist of meeting agendas and minutes (taken by the secretariat of the Network), reports produced by Network members and distributed via the email list, and the purpose statement of the Network. Additionally, the yearly activity reports of the Network and relevant legal texts were included in the data.

4.3. Data analysis methods

The combination of participatory observations, interviews and document analysis allows for triangulation of the Network’s practice and its logic (Alvesson and Sköldberg Citation2018). Furthermore, it allows us to delve into the experiences of the civil servants in the nexus between policy, climate science and on-the-ground implementation, which Goodman describes as the purpose of “climate ethnography” (Goodman Citation2018).

By following the Network over time in various arenas, and continuously making field notes, combined with reading the collected reports and documents, we developed our understanding of important routines that appear to maintain the practice. We continued by developing tentative ideas of the logic characterising the Network’s practice and what functions it serves for its members, by asking questions like “why does it make sense for the members to do what they do?” (Schatzki Citation1996), and “what assumptions must the practice hold for these norms and routines to make sense?” (Bueger Citation2014).

These initial insights were used to build our interview guide. Through the interviews, we gained access to the members’ own perspective and reflections on the importance of the Network for their own work. Importantly, this gave use their reflection on the Network with a degree of distance as the interviews, by definition, were outside of the Network’s practice.

Through repeated listening to meeting recordings and reading of interview transcripts, we made categories of routines in the Network and what kind of reactions deviations from these routines generated. This was done in several iterations. The first author made a first categorization of themes in NVivo. In the second iteration, the second author narrowed the material down, focusing on the Network’s view on its own role and the value of the network as perceived by the civil servants, while the first author focused on the civil servants’ understanding of adaptation. In the third iteration, we worked closely focusing on interactions where routines and assumptions were identified in order to develop a description of the logic of practice. With the logic of the practice in mind, we identified subversive performative acts, when members of the practice on occasions deviated or challenged the logic of the practice, including how these actions were responded to. For example if they were appreciated or only accepted, or if they led to open or hidden disputes, or even immediate sanctions.

5. The main activities of the network

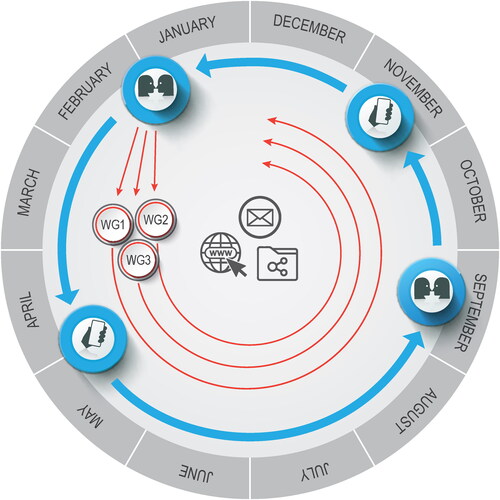

The Network has four arenas within which members interact: meetings, working groups, a shared virtual workspace and a joint e-mail list. In addition to these, there is a website for external communication. Understanding the purpose of these arenas and how the members use them is important for our analysis. Therefore, we described them in some detail. For an overview of these arenas see .

The dominant communication in these arenas was concerned with how the authorities map, plan, model, pilot, and investigate etc. to address knowledge gaps in the preparedness to meet climate change within their respective areas of responsibility. Climate change as a phenomenon (for example scenarios or scientific developments) or the consequences (especially indirect effects, cross-sectoral consequences and cascading effects) were very rarely discussed or even mentioned. Rather, climate change and its consequences served as a seldom explicitly acknowledged backdrop to this communication. Below, we give a brief description of each arena.

5.1. The meetings

Four times per year, the Network arranges meetings, two by phone and two in person, to which all members are invited.

The two annual phone meetings last for about 90 min and follow a standard agenda to update the members on the latest information regarding the website and progress of the working groups (described in more detail below). The Chair of the Network from SMHI leads the meetings with encouraging exclamations indicating that the agenda is tight. Discussions are very rare during these meetings. Questions asked by the members are of a clarifying nature, including, for example, the content of the website or details related to the ongoing working groups.

Between the two phone meetings, the Network meets in person twice a year, as a minimum (replaced by virtual meetings in 2020). These meetings are hosted by one of the members of the Network, i.e. at the head office of one of the authorities. One is a full-day meeting held at the beginning of the year and the other, held six months later, runs from lunch to lunch with an overnight stay. The first part of these meetings has the same general agenda as the phone meetings. The difference is that there is more room for discussion and questions compared to the phone meetings, but in general, they are kept short and move along quickly in order to get through the whole agenda. The second part of the meetings is used for presenting and discussing ideas for new working groups, study visits abroad or new responsibilities or assignments given by the government to specific government authorities. In addition, coffee breaks, lunches, and for the two-day meeting, a joint dinner and breakfast, allow for small talk and making contacts. The two annual in-person meetings are the only opportunities for formal and informal discussions among the members organised within the Network.

5.2. Working groups

The working groups take a central role when it comes to the actual outputs from the Network. The working groups are set up to foster practical collaboration between the members, and to address perceived knowledge gaps by producing reports, models and guides etc. The groups are created through an intricate and complex process of proposal, evaluation through voting, and finally funding through SMHI’s budget for adaptation projects. At least three different authorities need to support a proposal for a project to be eligible for funding. All the proposals are submitted and evaluated individually by all members of the Network through a multi-criteria scheme, created jointly in 2016, where different aspects of the proposed projects are judged and scored. The projects are then ranked according to average score and funded from top downwards until the budget for the current year is allocated, provided the projects meet a certain minimum score. The projects are always on a one-year basis, but in reality they start in the second quarter and have to finish before the year ends. A consultant often does the practical work decided upon by the working group.

5.3. The shared virtual workspace and the email list

The Network also has a shared platform for working on and uploading documents. Agendas, minutes, reports, suggestions for working groups are uploaded here. We have not been allowed into this virtual space. However, it has been increasingly clear to us through the meetings and interviews that it works more as a repository or archive, rather than as an active workspace.

Finally, the Network also has an email list of all the individual civil servants who participate in the Network’s activities. This list is almost exclusively used by the secretariat and other functions at SMHI for information prior to meetings, and for reminders about material that has been uploaded to the shared workspace. Occasionally, other members use the list to inform the Network of an upcoming seminar or final report from a working group.

5.4. The Website – klimatanpassning.se

In addition to the spaces where representatives can interact, described above, the Network hosts a website. Essentially, the Network started as a website-network, and the website still has a special standing within the Network. It is, as already described, a standing item on the agenda of every meeting, but it is additionally often mentioned spontaneously during the meetings; especially by the Chair, who reminds members to contribute with information to and promote the website when appropriate.

6. Results and analysis

The analysis is presented in two segments corresponding to our analytical concepts and research questions. The first section uses “logic of practice” to capture the dominant sense-making process, routines and assumptions regarding adaptation and the Network’s own role in the adaptation governance regime, i.e. responding to our first question. The second section focuses on subversive performative acts and the responses to which they give rise. Subversive performative acts are challenges to the logic of practice, and therefore openings for critical reflection. Exploring this potential for joint critical reflection is key to understanding the practice’s potential for leading transformational adaptation.

6.1. The logic of the practice: sharing information and demonstrating action

The arenas for interaction, described above, were all used in ways that facilitated effective information sharing and favoured activities that provided fast and visible results. The standard agenda for the Network meetings was tight, focusing on presentations and updates from the Chair and the members. The Chair often dominated, especially in the phone meetings and the virtual meeting. The Chair rarely reminded the members of the tight agenda, but instead led the meetings by cheerful and rapid speaking to encourage them to move on. The members showed how well accepted this way of conducting the meetings was by only asking clarifying questions demanding simple answers, thereby reproducing the idea that deviations from the agenda were not desirable. On occasions when questions related to presentations were more open and complicated, they were tabled and it was suggested that they be solved later, e.g. via email or a separate meeting. One interviewee demonstrated how the ability to keep to the agenda and be time efficient in meetings makes sense by commenting: “the members are well-trained, which is necessary. Otherwise the meetings would turn into a cacophony!” (I1). During the in-person meetings, there was more room for discussion, but the discussions were, with few exceptions, instrumental in character.

The activities in the other three arenas followed a similar pattern, focusing on efficient information sharing with little room or inclination to go beyond clarifying questions. The working groups have been initiated for two reasons: to implement projects to produce information to address knowledge gaps related to adaptation, and to strengthen the collaboration between the members. However, as the selection of projects was based on the individual members voting on proposals without prior discussion, there was no room for joint explorations on whether the chosen projects actually target the most relevant gaps. Some of those we interviewed considered the voting process to be too complicated and said they did not feel qualified to make judgements about the relevance of the proposed projects. Others said the outcomes and the scores given were too subjective and driven by the knowledge and interest of individual civil servants and the authority they represent (I1, I2, I3, I6). The selection procedure was up for discussion in two meetings (M2 & M4) but did not lead to any changes. As already mentioned, to facilitate collaboration at least three authorities must support new project proposals for funding. Based on the interviews, documents and meeting notes, it is clear the projects usually lasted for less than a year, were often driven by a single authority that hired a consultant to produce the report, with two other authorities as tag-alongs to fulfil the requirements to obtain funding.

The email list was, according to our interviewees, used for information spreading and as a shorthand to get in contact directly with civil servants at other authorities, rather than for questions or discussions directed to the whole network. Similarly, the virtual working space was used as an archive rather than as a collaborative space. For example, it was indicated that the working groups, which perhaps should benefit the most from this virtual working space, usually found other ways of communicating, and only uploaded the final reports.

Our analysis makes clear that the arenas for interaction did not offer space for the members to discuss matters that are more complex. This was not based on any explicit discussions or decisions made by the Network. Rather, their design and the way of using them have taken form in a routine way, guided by a logic that emphasizes the importance of efficient information sharing. From this logic, it makes sense to disregard and ignore information and questions that would demand deeper and more critical discussions related to the work and priorities of the Network.

The other characteristic of the logic of the Network’s practice is the importance of demonstrating energy and action. Two recurring phrases that were used when the members reported on their activities were: “pick the low hanging fruits” and “join things that are already happening”. Taking this a step further, indicating how it is internalized into practice, a representative of one of the central authorities, during a presentation for the entire Network proclaimed: “The low hanging fruits are the most prioritized!”. Since these phrases were never openly questioned or commented, we interpret them as reflecting the implicit normativity and logic behind an incremental approach to climate change adaptation: Members “ought to” do anything that is easy to accomplish in order to show that things are moving forward, get a foot in with other already ongoing projects, to gain some small wins.

The way the website was used reveals similar logic. The Network was once formed around the website to share information and it still served the members’ need to keep themselves updated on what is happening concerning adaptation in Sweden’s public sector. But the website also had another, less explicit but as salient, purpose. It was regarded important to keep it constantly updated with knowledge that the Network produced and with activities that were arranged, as it was seen as the face of the Network towards the public, politicians and decision-makers. The website was a standing item on the meeting agenda and members were reminded to promote the page when appropriate. On occasions, members apologized (without prompting) for having forgotten to send new information to be published on the website since the last meeting. This shows that the members collectively share the understanding of the importance of their work being visible and appearing effective to the outside world.

To summarize, three key ideas characterise the practice and work as taken for granted assumptions shaping the logic of the practice. First, efficient exchange of information and the continuous production of more information are assumed to lead to appropriate and effective adaptation action. Second, an incremental approach to adaptation, focusing on “easy” wins, as sufficient to manage the consequences of the climate crisis. Third, visibility is seen key for the Network to be able to fulfil its mission of being part of developing “a long-term sustainable and robust society that actively meets climate change” (National Network for Adaptation Citation2019, 3, authors’ translation from Swedish).

With the logic of the practice, its routines and assumptions described, we now turn to describing situations where these are challenged by subversive performative acts.

6.2. Subversive performative acts: challenges to the “logic” and the subsequent responses

The members did not always strictly follow the logic described above. Challenges occurred, especially during the physical meetings (M2 and M4), where there was more time and it was somewhat easier to intervene than during the phone meetings. Occasionally, they challenged what we have identified as the “ought to” of the practice by commenting or asking questions that significantly differed from the typical questions, along the lines of “when will a report be available?” or” how long will a specific project run?”. We interpret these challenges as openings for critical reflection on the logic of practice and, therefore, a window for change. Below, we provide four examples of subversive performative acts, as well as the reactions they gave rise to by the other members of the practice.

At one meeting (M4), a member challenged the “more information is needed” logic by hinting at the indisposition of the Network to take advantage of the opportunities offered to jointly maintain overviews of activities and connect previous projects with new ones. Two influential members of the practice had recently been given a government assignment concerning land changes (e.g. erosion, mudslides and landslides) due to climate effects. This assignment was presented together with an outline for the project. Another Network member pointed out that the proposed project strongly overlapped with an already finished project, and thus questioned the relevance of yet another scoping project. Why not, instead, build upon and use the previous project, and aim more for implementation of ideas already presented in the previous report? The presenters replied that they would look into this overlap, but also pointed out that the government assignment needed to be completed, regardless of any duplication of work, effectively putting themselves beyond responsibility and shutting down the opportunity for reflection.

A similar notion, but more questioning the effectiveness of information alone, was aired at one of the Working Group Meetings (WGM2). Here, the project manager expressed a hope to “actually do something” in the next project, as the last two projects this member had initiated had gathered valuable information, but so far stayed as desk products. This was said in earnest, but light-heartedly. As it was said by the project manager, who also acted as chair of the meeting, at the very end of the meeting, we do not interpret it as an intention to open up a discussion. Rather the person behind the suggestion was aware that the suggestion violated the norms of the practice.

At another meeting (M2), a member addressed the consequences of changing climate and thus broke with the unspoken norm that meetings should serve instrumental purposes of information sharing and not deviate from the agenda. The member made reflections based on a report concerning how climate change will have devastating effects on food production globally, and in turn in Sweden, which is a food importing country. The member continued by saying, “this is really worrying and could be a real crisis in just a couple of decades”. There was a moment of silence before the same member continued: “it makes you think that maybe we need to rethink weekend trips to New York and so on”. The issues raised here clearly point to concerns about how the Network’s incremental approach to adaptation neglects obvious risks with the climate crisis. However, the response to this challenge of the prevailing logic was sanctioning through laughter, silence, and quickly moving on to the next item on the agenda by the other members.

At the same meeting (M2), a discussion emerged about how the Network has interpreted the legislation that took effect at the beginning of 2019 and that many of the members had been pushing for. The legislation instructs the member authorities to analyse their vulnerabilities and adaptation needs, as well as their already taken adaptation measures. At the meeting, the author of one of the first reports presented their process and the results. They based their report on the RCP 4.5 scenario to assess their vulnerabilities, while “only looking at some aspects of 8.5”. This raised a challenge from another member: “Did they (the authors) think that RCP 4.5 was the correct or sensible scenario to plan for?” to which the answer by the author was “no, probably not”. The answer did not give rise to any further discussion or questions. This highlights the high acceptance of the tendency to produce and show visibility (in form of a quickly finished report) at the cost of more complex and, most likely, more useful results.

These four challenges were aimed at different aspects of the logic of practice, but shared the same outcome. None of these situations led to further reflection or discussions. Other members of the practice closed three of them down, and one was more of a quip than a serious attempt for discussion.

7. Concluding Discussion

In this article, we have started from the assumption that the unprecedented, unpredictable and existential situation we as society find ourselves in due to the unfolding climate crisis cannot be dealt with solely through predetermined ideas and familiar measures. To contribute to a society able to withstand known and unknown effects of the climate crisis (Hallgren and Ljung Citation2005), those responsible for developing, enabling and implementing adaptation measures need to question ingrained thought patterns, routines and preconceived working methods. They need to create practices that are open and reflexive in planning, prioritising and decision-making, and foster critical (self) reflection (Paschen and Ison Citation2014). Empirically we have focused on a government network in Sweden and theoretically we have utilized a framework of Social Practice Theory to explore this capacity for critical reflection necessary for achieving transformational adaptation.

In this section, we start by discussing our findings relating to the case in two sections corresponding to our research questions. The third and last part extrapolates these findings and brings them into discussion with related studies concerned with transformational adaptation, especially from an institutional and governance perspective.

7.1. The “low hanging fruit” strategy – making sense of roles and priorities

Our analysis shows that the Network’s practice assumes (more) information is a sufficient (or at the very least the prioritised) catalyst for effective and appropriate adaptation action. This, in turn, leads to positioning the Network as an information hub, producing reports, handbooks and visual guides, mainly for government authorities and municipalities. The analysis further reveals a strong tendency to prioritise and promote “low hanging fruit” and bandwagoning on ongoing projects in order to achieve easy, quick and generally small victories. Consequently, an incremental approach to adaptation is promoted and an implicit assumption of transformational adaptation being unnecessary permeates the practice. Related to the idea of focusing on “low hanging fruit”, and efficient information flow, is the notion of visibility as crucial for the Network and its members. The routines (re)producing this sensemaking are tightly scheduled meetings, focused on efficient information sharing and favouring questions of an instrumental and technical character, while pushing deeper discussion into separate venues (effectively out of the practice). It is clear that the logic of practice is well established, as members rarely deviate. The routines and sensemaking the practice fosters make it difficult for members to question the assumptions. Instead, focus is on implementing and demonstrating activities that can be carried out without threatening the prevailing logic of the practice.

7.2. Adapting climate change – on the closing of critical questions

Still, even stable practices are open to challenges and change. Using the concept of “performativity” to understand this openness we identified subversive performative acts in our material. Challenges occur, but we find that instead of opening up for joint reflection the challengers are often sanctioned for breaking the norms. The responses from the other members imply that questions and views that do not correspond to the assumptions in practice must not be actively engaged. However, since members are reacting to the deviations, it is also clear that they do not go unnoticed, i.e. they fulfil the criteria of being within the conceivable bounds of the practice. Rather, what is lacking is a capacity of the practice to appreciate them and treat them as openings for critical reflection on routines, priorities and taken for granted assumptions.

The gravest consequence of the sensemaking the practice fosters is downplaying the seriousness of the climate crisis. This is shown, for example, in the way disruptions to routine assumptions are reacted to, such as the (nervous) laughter to potential food crisis and concerns about the relevance of the Network’s approach to adaptation. Another example is the way the choice of a more optimistic climate scenario than they say they believe in as a base for a strategy, does not lead to further discussions. To put it more bluntly, members of the network adapt their interpretation of the climate crisis to fit the current modus operandi of the practice, rather than question the logic of the practice in order to respond to the climate crisis more effectively.

Interviewees, who expressed that they find their way of working unsatisfactory, and that they would like to see more ambitious and radical action, support our interpretation. Members thus show they, in fact, have the ability to reflect, express doubts about and criticise the prevailing adaptation approach, which reveals how the “logic of practice” stifles this ability in their joint practice in the Network.

We acknowledge that the civil servants we have followed and worked with are competent, committed and set on reducing vulnerabilities through their adaptation strategies. We therefore see considerable potential in the Network as a central actor within the Swedish adaptation governance regime, with the ability to influence both vertically (from the ministries to the municipalities) and horizontally (building momentum and pushing government authorities lagging) to steer adaptation into a more transformational approach. This potential can be realised if the members can be encouraged to raise awareness of, and jointly explore, the implicit assumptions behind their routines and current way of organizing and prioritizing their activities (Patterson and Huitema Citation2019). To create conditions for this joint critical reflection they need to at least partially “de-routinize” their practice (Hoffman and Loeber Citation2016) and deliberately create space for exploring different sets of values and knowledge (Gerlak, Heikkila, and Newig Citation2020). We argue such conditions could prompt and inspire them to create joint working procedures that enable continuous reflection on how they can utilize the opportunities the Network offers, and the vast knowledge they collectively hold. In doing so it would open up for jointly contesting ongoing activities, identifying gaps in priorities, acknowledge high impact scenarios, and consider their work and ambitions in relation to long- and short-term impacts of the climate crisis.

7.3. Social Practice theory insights for achieving transformational adaptation

In this paper, our main thrust has been to introduce a Social Practice Theory approach to transformational adaptation. We are, here, bringing our practice approach into dialogue with the governance literature focused on institutional (re-)arrangements to induce transformational adaptation, which has dominated this literature.

Our results are relevant for, and have parallels with, studies of adaptation governance that recognise the need for reorganisation of current ways of working to meet the climate crisis. For example, we largely agree with Grin (Citation2020) who states that governance actors less committed, or reluctant, need inspiration to actively start re-thinking the logics that govern their work. We would add that, from a practice theoretical view, assumptions, routines and know-how are being created and activated within the social practices the actors are in (rather than something individual members carry in their heads). This indicates that group-level interventions are needed to achieve the desired changes. This conclusion is supported by the disparate ideas regarding what constitutes effective adaptation presented by the same individuals, depending on whether they are in the Network practice or in the interview practice.

The results of our study also feed into the debate about coordination as a means for achieving adequate adaptation (Clar Citation2019; Howes et al. Citation2015). The very nature of the climate crisis demands responses that are coordinated over sectors and governing levels. However, following a Network that largely strives to work for coordinating and amplifying adaptation measures, horizontally on the national level and vertically between governing levels, casts doubt over coordination as a silver bullet for adaptation. The Network excels at coordinating (at least horizontally), but what is coordinated is dictated by the meaning making process shaped by the practice. In other words, if incremental (and often reactive) adaptation is understood as sufficiently effective to deal with climate change effects, coordinating this across actors is not necessarily beneficial.

Our conclusions also have bearings on Termeer, Dewulf, and Biesbroek’s (Citation2017) suggested third way for effective adaptation, to continuously seek small wins with high impact instead of either incremental or transformational adaptation. The Network’s practice seems to favour a similar approach, which is indicated by quotes like “the low hanging fruit are the most prioritized!”. However, our study shows that even in generally favourable conditions, this strategy may end up in the same insufficient incremental and often reactive adaptation measures deemed inadequate by large parts of the science community (Kates, Travis, and Wilbanks Citation2012; Nightingale et al. Citation2020; Schultze et al. Citation2022). Considering the increasing alarm with which even the IPCC now is urging (Western) societies to transform their ways of adaptation (IPCC Citation2022), it is worth questioning all strategies that build upon the assumption of small efforts leading to big effects.

Using practice as the unit of analysis, we join in the framing of meaning making as social endeavour created in interaction. A practice approach brings a specific focus on how routines and norms, in situ, is part of shaping interaction and thereby meaning making process. This implies that changes in meaning making processes are not only an issue of communicating differently, but rather changing the conditions in which the communication occurs. By focusing on subversive performative acts, understood as a way of critical engagement and challenging the prevailing order, our study contributes with a method to distinguish openings for joint critical reflection, as a strategy to change the conditions. Recognizing such challenges as opportunities for making assumptions, routines and norms explicit is crucial to change meaning making process, which in turn is necessary to create a more sustainable society.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the National Network for Adaptation [Myndighetsnätverket för klimatanpassning] for generously giving us the opportunity to observe and record their meetings, for taking the time to be interviewed and for sharing their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Hereafter called ‘the Network’.

References

- AghaKouchak, Amir, Felicia Chiang, Laurie S. Huning, Charlotte A. Love, Iman Mallakpour, Omid Mazdiyasni, Hamed Moftakhari, Simon Michael Papalexiou, Elisa Ragno, and Mojtaba Sadegh. 2020. “Climate Extremes and Compound Hazards in a Warming World.” In Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Vol. 548, edited by R. Jeanloz and K. H. Freeman, 48, 519–48. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-071719-055228.

- Alvesson, Mats, and Kaj Sköldberg. 2018. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Anderson, Kevin, John F. Broderick, and Isak Stoddard. 2020. “A Factor of Two: How the Mitigation Plans of ‘Climate Progressive’ Nations Fall Far Short of Paris-Compliant Pathways.” Climate Policy 20 (10): 1290–1304. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1728209.

- Arts, Bas, Jelle Behagel, Esther Turnhout, Jessica de Koning, and Séverine van Bommel. 2014. “A Practice Based Approach to Forest Governance.” Forest Policy and Economics 49 (Dec): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2014.04.001.

- Baker, Ingrid, Ann Peterson, Greg Brown, and Clive McAlpine. 2012. “Local Government Response to the Impacts of Climate Change: An Evaluation of Local Climate Adaptation Plans.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.009.

- Bauer, Anja, Judith Feichtinger, and Reinhard Steurer. 2012. “The Governance of Climate Change Adaptation in 10 OECD Countries: Challenges and Approaches.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 14 (3): 279–304. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2012.707406.

- Behagel, Jelle Hendrik, Bas Arts, and Esther Turnhout. 2019. “Beyond Argumentation: A Practice-Based Approach to Environmental Policy.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 479–491. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2017.1295841.

- Bevir, Mark. 2005. New Labour: A Critique. London: Routledge.

- Birtchnell, Thomas. 2012. “Elites, Elements and Events: Practice Theory and Scale.” Journal of Transport Geography 24: 497–502. Special Section on Theoretical Perspectives on Climate Change Mitigation in Transport (Sep): doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.020.

- Böhm, Steffen, and Sian Sullivan. 2021. “Introduction: Climate Crisis? What Climate Crisis?” In Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis, edited by Steffen Böhm and Sian Sullivan, xxxiii–lxx. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/obp.0265.29.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Broto, Vanesa Castan. 2017. “Urban Governance and the Politics of Climate Change.” World Development 93 (May): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.031.

- Bueger, Christian. 2014. “Pathways to Practice: Praxiography and International Politics.” European Political Science Review 6 (3): 383–406. doi:10.1017/S1755773913000167.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity.” Routledge Classics. New York: Routledge.

- Clar, Christoph. 2019. “Coordinating Climate Change Adaptation across Levels of Government: The Gap between Theory and Practice of Integrated Adaptation Strategy Processes.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (12): 2166–2185. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1536604.

- Crang, Mike, and Ian Cook. 2007. Doing Ethnographies. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Denton, Fatima, and Thomas J. Wilbanks. 2014. “Climate-Resilient Pathways: Adaptation, Mitigation, and Sustainable Development.” In Climate Change 2014 Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, edited by Christopher B. Field, Vicente R. Barros, David Jon Dokken, Katharine J. Mach, and Michael D. Mastrandrea, 1101–1131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415379.025.

- Di Gregorio, Monica, Leandra Fatorelli, Jouni Paavola, Bruno Locatelli, Emilia Pramova, Dodik Ridho Nurrochmat, Peter H. May, Maria Brockhaus, Intan Maya Sari, and Sonya Dyah Kusumadewi. 2019. “Multi-Level Governance and Power in Climate Change Policy Networks.” Global Environmental Change 54 (Jan): 64–77. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.003.

- Eriksen, Siri H., Andrea J. Nightingale, and Hallie Eakin. 2015. “Reframing Adaptation: The Political Nature of Climate Change Adaptation.” Global Environmental Change 35 (Nov): 523–533. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.014.

- Fazey, Ioan, Peter Moug, Simon Allen, Kate Beckmann, David Blackwood, Mike Bonaventura, Kathryn Burnett, et al. 2018. “Transformation in a Changing Climate: A Research Agenda.” Climate and Development 10 (3): 197–217. doi:10.1080/17565529.2017.1301864.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Fook, Tanya Chung Tiam. 2017. “Transformational Processes for Community-Focused Adaptation and Social Change: A Synthesis.” Climate and Development 9 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1080/17565529.2015.1086294.

- Gerlak, Andrea K., Tanya Heikkila, and Jens Newig. 2020. “Learning in Environmental Governance: Opportunities for Translating Theory to Practice.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (5): 653–666. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1776100.

- Glaas, Erik, and Sirkku Juhola. 2013. “New Levels of Climate Adaptation Policy: Analyzing the Institutional Interplay in the Baltic Sea Region.” Sustainability 5 (1): 256–275. doi:10.3390/su5010256.

- Gonzales-Iwanciw, Javier, Art Dewulf, and Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen. 2020. “Learning in Multi-Level Governance of Adaptation to Climate Change: A Literature Review.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 63 (5): 779–797. doi:10.1080/09640568.2019.1594725.

- Goodman, James. 2018. “Researching Climate Crisis and Energy Transitions: Some Issues for Ethnography.” Energy Research & Social Science 45: 340–347. Special Issue on the Problems of Methods in Climate and Energy Research (Nov): doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.07.032.

- Göpel, Maja. 2016. The Great Mindshift - How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations Go Hand in Hand. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-43766-8.

- Granberg, Mikael, Karyn Bosomworth, Susie Moloney, Ann-Catrin Kristianssen, and Hartmut Fünfgeld. 2019. “Can Regional-Scale Governance and Planning Support Transformative Adaptation? A Study of Two Places.” Sustainability 11 (24): 6978. doi:10.3390/su11246978.

- Grin, John. 2020. “‘Doing’ System Innovations from within the Heart of the Regime.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (5): 682–694. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1776099.

- Hallgren, Lars, and Magnus Ljung. 2005. Miljökommunikation: Aktörsamverkan Och Processledning. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Heikkila, Tanya, and Andrea K. Gerlak. 2019. “Working on Learning: How the Institutional Rules of Environmental Governance Matter.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (1): 106–123. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1473244.

- Higginson, Sarah, Eoghan McKenna, Tom Hargreaves, Jason Chilvers, and Murray Thomson. 2015. “Diagramming Social Practice Theory: An Interdisciplinary Experiment Exploring Practices as Networks.” Indoor and Built Environment 24 (7): 950–969. doi:10.1177/1420326X15603439.

- Hjerpe, Mattias, Sofie Storbjörk, and Johan Alberth. 2015. “‘There is Nothing Political in It’: Triggers of Local Political Leaders’ Engagement in Climate Adaptation.” Local Environment 20 (8): 855–873. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.872092.

- Hoffman, Jesse, and Anne Loeber. 2016. “Exploring the Micro-Politics in Transitions from a Practice Perspective: The Case of Greenhouse Innovation in The Netherlands.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (5): 692–711. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1113514.

- Howes, Michael, Peter Tangney, Kimberley Reis, Deanna Grant-Smith, Michael Heazle, Karyn Bosomworth, and Paul Burton. 2015. “Towards Networked Governance: Improving Interagency Communication and Collaboration for Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation in Australia.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 58 (5): 757–776. doi:10.1080/09640568.2014.891974.

- IPCC. 2022. “Summary for Policymakers.” In: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.00110.1017/9781009157926.001’.

- Jacob, Klaus, and Paul Ekins. 2020. “Environmental Policy, Innovation and Transformation: Affirmative or Disruptive?” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22: 1–15. (Jul), doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1793745.

- Kates, Robert W., William R. Travis, and Thomas J. Wilbanks. 2012. “Transformational Adaptation When Incremental Adaptations to Climate Change Are Insufficient.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (19): 7156–7161. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115521109.

- Keskitalo, Carina. 2010. “Adapting to Climate Change in Sweden: National Policy Development and Adaptation Measures in Västra Götaland.” Chap. 5. In Developing Adaptation Policy and Practice in Europe: Multi-Level Governance of Climate Change, edited by Carina Keskitalo, 189–232. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9325-7.

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., Sirkku Juhola, and Lisa Westerhoff. 2012. “Climate Change as Governmentality: Technologies of Government for Adaptation in Three European Countries.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 55 (4): 435–452. doi:10.1080/09640568.2011.607994.

- Köhler, Jonathan, Frank W. Geels, Florian Kern, Jochen Markard, Elsie Onsongo, Anna Wieczorek, Floortje Alkemade., et al. 2019. “An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31 (Jun): 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lenton, Timothy M., Johan Rockström, Owen Gaffney, Stefan Rahmstorf, Katherine Richardson, Will Steffen, and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. 2019. “Climate Tipping Points — Too Risky to Bet Against.” Nature 575 (7784): 592–595. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0.

- Löf, Annette. 2010. “Exploring Adaptability through Learning Layers and Learning Loops.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5-6): 529–543. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505429.

- Massey, Eric, Dave Huitema, Heiko Garrelts, Kevin Grecksch, Heleen Mees, Tim Rayner, Sofie Storbjörk, Catrien Termeer, and Maik Winges. 2015. “Handling Adaptation Policy Choices in Sweden, Germany, the UK and The Netherlands.” Journal of Water and Climate Change 6 (1): 9–24. doi:10.2166/wcc.2014.110.

- Metzger, Jonathan, Annika Carlsson Kanyama, Per Wikman-Svahn, Karin Mossberg Sonnek, Christoffer Carstens, Misse Wester, and Christoffer Wedebrand. 2021. “The Flexibility Gamble: Challenges for Mainstreaming Flexible Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 23 (4): 543–558. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2021.1893160.

- Milner, Alexander M., Kieran Khamis, Tom J. Battin, John E. Brittain, Nicholas E. Barrand, Leopold Füreder, Sophie Cauvy-Fraunié., et al. 2017. “Glacier Shrinkage Driving Global Changes in Downstream Systems.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114 (37): 9770–9778. doi:10.1073/pnas.1619807114.

- Ministry of the Environment. 2018. Förordning (2018:1428) Om Myndigheters Klimatanpassningsarbete. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://rkrattsbaser.gov.se/sfst?bet=2018:1428.

- National Network for Adaptation. 2018. “Organisation Description”. Created 2017-01. Revised 2018-05-21.

- National Network for Adaptation. 2019. “Organisation Description”. Revised version from 201911-21.

- Nicolini, Davide. 2012. Practice Theory, Work, and Organization: An Introduction. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicolini, Davide. 2017. “Practice Theory as a Package of Theory, Method and Vocabulary: Affordances and Limitations.” Chap. 2. In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories, edited by Michael Jonas, Beate Littig, and Angela Wroblewski, 19–34. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52897-7_2.

- Nightingale, Andrea Joslyn, Siri Eriksen, Marcus Taylor, Timothy Forsyth, Mark Pelling, Andrew Newsham, Emily Boyd, et al. 2020. “Beyond Technical Fixes: Climate Solutions and the Great Derangement.” Climate and Development 12 (4): 343–352. doi:10.1080/17565529.2019.1624495.

- Oberlack, Christoph. 2017. “Diagnosing Institutional Barriers and Opportunities for Adaptation to Climate Change.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 22 (5): 805–838. doi:10.1007/s11027-015-9699-z.

- O’Brien, Karen. 2012. “Global Environmental Change II: From Adaptation to Deliberate Transformation.” Progress in Human Geography 36 (5): 667–676. doi:10.1177/0309132511425767.

- Owen, Gigi. 2020. “What Makes Climate Change Adaptation Effective? A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Global Environmental Change 62 (May): 102071. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102071.

- Paschen, J.-A, and R. Ison. 2014. “Narrative Research in Climate Change Adaptation: Exploring a Complementary Paradigm for Research and Governance.” Research Policy 43 (6): 1083–1092. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.12.006.

- Patterson, James J. 2021. “More than Planning: Diversity and Drivers of Institutional Adaptation under Climate Change in 96 Major Cities.” Global Environmental Change 68 (May): 102279. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102279.

- Patterson, James J., and Dave Huitema. 2019. “Institutional Innovation in Urban Governance: The Case of Climate Change Adaptation.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (3): 374–398. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1510767.

- Pierre, Jon. 2020. “Nudges against Pandemics: Sweden’s COVID-19 Containment Strategy in Perspective.” Policy & Society 39 (3): 478–493. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783787.

- Remling, Elise. 2019. “Adaptation, Now?: Exploring the Politics of Climate Adaptation through Poststructuralist Discourse Theory.” PhD diss. Södertörn University, Huddinge.

- Rietig, Katharina. 2019. “Leveraging the Power of Learning to Overcome Negotiation Deadlocks in Global Climate Governance and Low Carbon Transitions.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (3): 228–241. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1632698.

- Roelfsema, Mark, Heleen L. van Soest, Mathijs Harmsen, Detlef P. van Vuuren, Christoph Bertram, Michel den Elzen, Niklas Hoehne., et al. 2020. “Taking Stock of National Climate Policies to Evaluate Implementation of the Paris Agreement.” Nature Communications 11 (1): 2096. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15414-6.

- Salih, Sara. 2007. “On Judith Butler and Performativity.” Chap. 3. In Sexualities & Communication in Everyday Life: A Reader, edited by Karen Lovaas and Mercilee M. Jenkins, 55–68. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Sarkodie, Samuel Asumadu, and Vladimir Strezov. 2019. “Economic, Social and Governance Adaptation Readiness for Mitigation of Climate Change Vulnerability: Evidence from 192 Countries.” The Science of the Total Environment 656 (Mar): 150–164. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.349.

- Schatzki, Theodore R. 1996. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schön, Donald A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schultze, Lisbeth, Carina Keskitalo, Irene Bohman, Robert Johannesson, Erik Kjellström, Henrik Larsson, Elsabeth Lindgren, Sofie Storbjörk, and Gregor Vulturius. 2022. “Första Rapporten Från Nationella Expertrådet För Klimatanpassning 2022. [The First Report by the National Expert Council on Climate Change Adaptation 2022]. Stockholm: SMHI.

- Scott, Helen, and Susie Moloney. 2022. “Completing the Climate Change Adaptation Planning Cycle: Monitoring and Evaluation by Local Government in Australia.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 65 (4): 650–674. doi:10.1080/09640568.2021.1902789.

- Silverman, David. 2014. Interpreting Qualitative Data: David Silverman. 5th ed. London: SAGE.

- Spaargaren, Gert, Machiel Lamers, and Don Weenink. 2016. “Introduction: Using Practice Theory to Research Social Life.” Chap. 1. In Practice Theory and Research: Exploring the Dynamics of Social Life, edited by Gert Spaargaren, Don Weenink, and Machiel Lamers, 3–27. London: Routledge.

- Termeer, C. J. A. M., Art Dewulf, and G. Robbert Biesbroek. 2017. “Transformational Change: Governance Interventions for Climate Change Adaptation from a Continuous Change Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60 (4): 558–576. doi:10.1080/09640568.2016.1168288.

- Ulibarri, Nicola, Idowu Ajibade, Eranga K. Galappaththi, Elphin Tom Joe, Alexandra Lesnikowski, Katharine J. Mach, Justice Issah Musah-Surugu, et al. 2022. “A Global Assessment of Policy Tools to Support Climate Adaptation.” Climate Policy 22 (1): 77–96. doi:10.1080/14693062.2021.2002251.

- Wamsler, C., J. Alkan-Olsson, H. Björn, H. Falck, H. Hanson, T. Oskarsson, E. Simonsson, and F. Zelmerlow. 2020. “Beyond Participation: When Citizen Engagement Leads to Undesirable Outcomes for Nature-Based Solutions and Climate Change Adaptation.” Climatic Change 158 (2): 235–254. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02557-9.

- Westberg, Lotten, and Cecilia Waldenström. 2017. “How Can We Ever Create Participation When We Are the Ones Who Decide? On Natural Resource Management Practice and Its Readiness for Change.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (6): 654–667. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1264298.