Abstract

While blue justice has gained traction, recognition and capability, which are necessary conditions for procedural and distributive justice, remain under-developed. We develop a four-dimensional blue justice framework that builds on recognition and capabilities to critically examine and advance justice in Poland’s marine spatial planning (MSP). We find that misrecognition of differential identities and capacities scripted powerless stakeholders out of participation and reduced possibilities for fair distribution. Conversely, MSP regulation augmented the rights of powerful actors through granting de jure “objecting” rights to some, inviting only strategic sectors to agenda-setting fora and, limiting MSP communication to meeting legal requirements. Several stakeholders also see defence and wind energy as key winners of MSP. While society will benefit from national security and energy sufficiency, especially given Russia’s increased weaponization of energy, many believe that financial profits from wind energy will accrue to developers. We offer governmental and planning measures to enhance capabilities.

1. Introduction

In the late 2000s, the idea of marine spatial planning (MSP) as a holistic approach to governing the sustainable management and use of the seas gained momentum worldwide following the first international workshop on MSP in 2007 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Just over a decade later, this “new kid” (i.e. MSP) “on the block” – i.e. ocean governance – (Smith Citation2015, 133) has matured and across the world. MSP is currently under development in about 70 countries; with states, industries, civil society and supranational institutions continuing to push for its acceleration. For instance, the European Union (EU) and UNESCO recently developed a joint international guide on MSP (UNESCO-IOC/European Commission Citation2021) to help triple the marine area under the status of MSP implementation worldwide by 2030.

In large parts, the sway of MSP as a better alternative to fragmented marine management systems lies in its rhetorical appeal to normative principles around equity, rationality, multi-use, consensus, ecosystem-based management, sustainable development, energy transitions and integration of sectors, stakeholders, land-sea, knowledge and climate change (Tafon Citation2018). However, recent evaluations have found MSP wanting on many of these principles. For instance, far from applying the ecosystem-based approach to balance social and ecological goals with economic objectives, MSP is seen as enabling extension of the ocean as a frontier of the neoliberal market economy (Flannery, Clarke, and McAteer Citation2019). Consequently, questions around power imbalances, community exclusion from decision-making, local knowledge, value systems, socioecological relationships to the sea and the distributed risks and vulnerabilities (human and non-human) to climate and environmental change, remain unaddressed (Germond-Duret, Heidkamp, and Morrissey Citation2022; St. Martin and Hall-Arber Citation2008; Tafon, Saunders, et al. Citation2019; Saunders, Gilek, and Tafon Citation2019; Tafon et al. Citation2022; Domínguez-Tejo and Metternicht Citation2018). In other words, overly blue growth-focused ocean governance and MSP in particular pays limited attention to the effects of climate change on nature and coastal community groups and does not sufficiently consider how transformations to sustainability may further affect marine life or people’s social, cultural, and environmental relationships with the marine environment.

The critical scholarship has advanced a blue justice framework to address some of the inadequacies of ocean governance and MSP, with particular emphasis on procedural and distributive justice (Bennett Citation2022; Bennett et al. Citation2021). Procedural justice unravels issues of power in decision-making, in terms of who can participate, how, when, and with what degree of influence (Saunders et al. Citation2020), while distributive justice is concerned with the way risks, burdens, benefits and responsibilities associated with blue growth/economy, and climate and environmental change, are distributed across groups (Tafon et al. Citationforthcoming).

While contributing toward a more inclusive and equitable ocean governance and MSP, the blue justice scholarship will have more transformative bite by addressing four important challenges. First, conceptions of blue justice must go beyond anthropocentric frames to include considerations of more-than-human entities, e.g. marine/coastal biodiversity and organisms that are equally, if not more, affected by diverse stressors, including climate change and related solutions (e.g. transitions to climate-neutrality), but also different blue economy and other sustainability transformation projects. Second, distributive and procedural accounts of justice fall short of addressing issues of historical injustices, unequal power relationships and institutional and structural arrangements that often undergird resource maldistributions and procedural injustice. This calls for greater emphasis on recognitional justice, or respect and protection of vulnerable identities at the intersection of gender, race, status, age, place, space etc. (Saunders et al. Citation2020; Bennett Citation2022). Third, there is need for a set of standards to determine the scope of justice. Nussbaum’s (Citation2006) capability approach offers insights, as it speaks to groups’ abilities to live a flourishing life, which we see as groups’ ability (or lack thereof) to organize themselves into collectives, to participate and influence decisions, to protect and strengthen their multidimensional wellbeing relationships to the sea/coast and to contribute to effective MSP. Relatedly, a key question is, how can MSP be reinvented to improve the conditions of coastally marginalized groups, such as small-scale fishers (SSFs), women and indigenous peoples, whose rights, capabilities and multidimensional relationships to the sea are threatened by climate change and different ocean interventions, including conservation, blue growth/economy and rapid energy transitions. A fourth and final issue is that conceptions of blue justice far outrun empirical examination of situated (in)justices as they are variously perceived, framed, experienced, or claimed across groups. As more countries move to the implementation phase of MSP, there is need to examine the extent to which ocean governance in different contexts is underpinned by principles and practices of justice, so as to generate empirically informed knowledge on challenges and possibilities for MSP to deliver blue recognitional, procedural and distributive justice, as well as capabilities.

We therefore elaborate a four-dimensional model of blue justice that centres recognition and capabilities as the conditions and necessary requirements for the procedural and distributive dimensions of justice, the ultimate goal of which is wellbeing – human and non-human. Our four-dimensional blue justice framework sheds light on how MSP can contribute to the broader sustainability dimensions of Agenda 2030 and beyond, particularly in terms of more explicitly addressing possibilities of coastally inclusive, just, equitable and greener blue economy (Louey Citation2022; Morrissey Citation2021; Axon et al. Citation2022) and low-carbon transitions at sea. Focusing on Poland, we deploy this framework to generate empirical insights into how MSP engages with blue justice and reflect on what might be critical enabling factors and impediments to realizing mutual benefits between MSP and blue justice. We pay particular attention to SSFs and other coastal groups (e.g. youth) that have multidimensional, yet underrecognized and undervalued, relationships to the sea/coast. Considering that the implementation phase of the Polish MSP is underway, this paper provides valuable insights against which policymakers and planners can address extant injustices of the first planning cycle.

In Section 2, we elaborate our four-dimensional blue justice framework with emphasis on recognition and capabilities. Section 3 outlines our research method. Section 4 is a synopsis of the institutional structure and planning processes of Poland’s MSP. Section 5 analyzes misrecognition in Polish MSP and its effects on procedural and distributive justice dimensions. Then, drawing on capability theory, we generate insights on how Polish authorities can better empower marginalized stakeholders. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. A four-dimensional framework of justice: bringing in recognition and capabilities

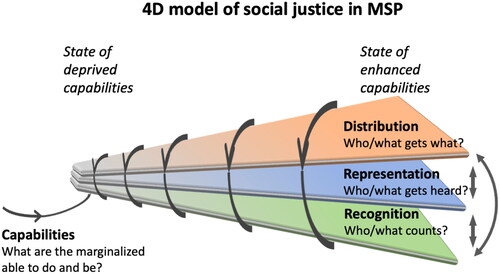

Fraser (Citation2009) developed a social justice framework that stresses the interdependence between recognition, representation and distribution, thus providing a tridimensional lens to consider how multiple aspects of power interact to affect recognition (of vulnerabilities, socio-cultural status), procedural justice and material and non-material aspects of distribution (of ‘goods’ and ‘bads’). The patterns of injustices associated with ocean interventions are complex (Germond-Duret, Heidkamp, and Morrissey Citation2022) and therefore difficult to attribute solely to any one of these dimensions, which is why Fraser (Citation2009) argues that they are indivisible and must be taken together. While we agree that the three dimensions of justice need to be interactively considered, we pay closer attention to recognition in MSP, or a lack thereof (i.e. misrecognition), as a factor that underlies procedural injustice (in decision-making spheres), maldistribution (of benefits, risks burdens and responsibilities) and limited agency, both for the planner to correct the previous two and for marginalized actors to contribute to MSP and to lead a flourishing life. In positive terms, we see purposeful action to strengthen the capabilities of marginalized groups as a necessary condition and requirement for better political influence, distributive justice and agency, or social contribution to ocean governance and individual/group self-realization.

From this premise, we follow Honneth’s (Citation1995) theory of recognition because it makes it possible to go beyond participatory spaces in MSP to interrogate MSP structural arrangements, including legal frameworks and policies that confer ocean citizenship and agency, and drive institutions and practices of ocean stewardship and political participation. We believe that societal marginalization is often rooted in structural injustices that require high-level political and legal remedies beyond MSP processes, so that vulnerable groups can participate as full subjects capable of leading a flourishing life and contributing toward nature-positive, people-centred blue economy and transitions to sustainability. Recognitional justice thus focuses on the structural and historical conditions that limit recognition of marginalized identities (e.g. the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, women, youths, etc.), interests, visions, beings and doings, sense of belonging, as well as knowledge and value systems, material and spiritual connections to the sea, which can have ramifications in terms of harm to the self and lead to capability deprivation. Harm can be ecological crimes (Lynch and Long Citation2022), as in the destruction of ecosystems and organisms, and their relationships and capabilities (Celermajer et al. Citation2021). It can also be psychological (relating to health and cultural wellbeing), political (e.g. incapacity to take part in and contribute to governance) and distributive (relating to risks, responsibilities, burdens and benefits). Recognition as a corrective is thus embodied in love or solidarity (loving care for the other’s wellbeing in light of their needs); respect (the organization of a system of political, legal and civil rights that allow subjects to be respected as autonomous beings with the same rights as others); and esteem (by which every being enjoys esteem according to their own identity and achievement as productive subjects) (Honneth in Fraser and Honneth Citation2003).

The actualization of love, respect and esteem is contingent on deeper understandings of the multiple ways that people and non-human Others relate to one another and to the functioning of ecosystems and life below and above water – a task for which we must cast our theoretic-analytical net beyond recognitional justice for guidance. We therefore broaden the tridimensional concept of justice to include capabilities theory ().

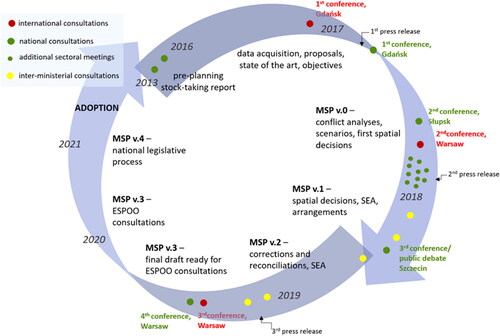

Figure 1. A 4-dimensional conceptual model of blue justice in MSP consisting of recognition, representation, distribution and capabilities. The model shows how these different blue justice dimensions and their interactive dynamic become more distinctive as capabilities are enhanced. Enhancing capabilities in MSP requires building an equitable structural basis to generate processes that interactively work to enhance recognition, representation and distribution to deliver improved blue justice outcomes.

At the core of justice is the idea that all beings, human and non-human, should be able to live a flourishing life. While procedural, distributive, and recognitional justice are constitutive of wellbeing, they can make a difference only insofar as they are informed by an understanding of what constitutes a flourishing life (Schlosberg Citation2013). Nussbaum (Citation2006) lists a range of human capabilities. They include life, bodily health and integrity, emotional, sensory and cultural bonds, affiliations, control over one’s environment and being able to protect others. In relation to care for nature as a form of capability, capability enhancement is “being able to live with concern for, and in relation to, animals, plants and the world of nature” (Nussbaum Citation2006, 70).

First, capability helps to map out why certain things like place and group identity, social bonds, good health, job security, aesthetics, recreation, biodiversity, the future, ocean health, therapy, culture and history matter to people (Robeyns Citation2020; Tafon, Howarth, et al. Citation2019). In terms of MSP and our focus on social justice, capability deprivation occurs through a lack of recognition and influence in decisions that impact on the environmental engagements and relationships to the sea that people value for their material and non-material wellbeing. Such dimensions of capability related to wellbeing (beyond only material concerns) include being able to: enjoy recreational (play) and spiritual activities, bodily health, adaptation to stressors, sensory (imaginative) engagement with the coast, emotional feelings/bonds of affiliation with others in relation to the sea, as well as being able to participate freely in and influence marine governance decisions and to care for and protect non-human nature. This is a particular problem in the case of SSFs, where the sea plays an important role in maintaining culture, economic welfare, community and inter-community affiliations and identity. But as intimated above, capability theory is concerned not only with social actors’ capabilities (ability to live the good life and to respond to stressors) but also those of non-human nature, including sentient non-human animals (Nussbaum Citation2006) and ecosystems (Fulfer Citation2013; Tschakert Citation2022). Here, capabilities are important for non-humans, including the ecosystems that provide opportunities to live a dignified and flourishing life.

Second, and following from the last point, capability partly explains why blue growth and energy transition practices often face struggles by communities, grassroots movements and other environmental stewards and defenders that seek to protect nature and multidimensional wellbeing relationships with the sea. Arguably, this is because some ocean managers and planners do not sufficiently visualize or consider the multidimensional beings and doings that make up social wellbeing or ecosystem integrity, nor the factors impeding their realization. Accordingly, perceptions or experiences of ocean/coastal interventions as threatening capabilities can lead to conflict, where conflict refers to struggle, or a challenge to institutionalized norms and practices and a demand for love, respect and esteem toward the vulnerable, human and non-human.

Third, capability theory acknowledges that an intrinsic feature of society is the uneven distribution of social, political and economic agency, resulting in unequal capacities among humans to participate, articulate interests and needs, and respond to multiple stressors. It also acknowledges the inherent inability of non-humans to do the above. Given this uneven playing field, capability lends itself less toward all people and more toward a vulnerability informed preferential treatment of the historically marginalized – a positive discrimination or affirmative action aimed at increasing recognition, rights and capabilities of vulnerable humans and non-human Others, while redressing past wrongs, harms, traumas and impediments, and minimizing future occurrences.

It follows from the above arguments that a capability-informed recognitional blue justice is critical to multispecies wellbeing. A capability-enhancing recognition is central to ocean governance as a normative foundation for ethico-political relationships concerned not only with identification of marginalized or vulnerable ocean subjects, but also respect and protection of their identity, the actualization and strengthening of their capacities and the esteem of their socioecological (including knowledge, biodiversity and nutritional) contribution. Capability as advanced thus, is crucial not only for ocean democracy and equity but also for achieving the environmental, economic and climate dimensions of sustainability. Conversely, misrecognition of multidimensional wellbeing and differential vulnerabilities and responsive abilities will undermine prospects for MSP to deliver its expressed sustainability objectives.

In this section, we have developed a four-dimensional framework of blue justice, in which we broaden conceptions of justice beyond anthropocentric frames and a narrow focus on procedural and distributive justice to encompass recognition and capabilities, human and non-human, as central elements of just transformations to sustainability. While non-humans are part of our justice framework (given relationalities and interdependencies between humans and non-human nature [Schlosberg Citation2007]), the empirical examination that follows focuses on the social/human dimension of justice alone. Specifically, we both examine how structural misrecognition plays out procedurally, and with what implications for distributive justice, and suggest measures to enhance capabilities for marginalized social actors. But first, we present our methodological strategy.

3. Methodology

To examine blue justice in the Polish MSP, we focused on the following capability-based recognition dimensions:

How vulnerabilities, capabilities and wellbeing related to the marine environment were considered and engaged with in MSP practice.

How acts of (mis)recognition in MSP regulation affected prospects for social representation in decisions and the distribution of material and non-material aspects of wellbeing.

Conditions for better recognition of vulnerabilities and/or strengthening of capabilities.

Empirically, we examined the institutional context of Poland’s MSP, focusing on the regulatory framework which directed and shaped the process of MSP development and its goals. We then examined planning documents and stakeholders’ written consultation submissions to discern diverse justice issues at stake and how these relate to structural conditions. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted in Polish during January-March 2021 and July-August 2021, focusing on social justice concerns. This was followed up in March 2022 with interviews with different SSF community representatives. This was in recognition that SSFs are a key MSP stakeholder group that relies on the sea for their socio-cultural and economic wellbeing and that past relationships between Polish maritime governance authorities and SSFs have been tumultuous (Tafon, Saunders, et al. Citation2019). We sought to gain insights into different perspectives and experiences of MSP (with a focus on procedural and distributive issues) as a basis for making policy and practice proposals on how to strengthen capabilities in MSP.

Purposive sampling was used in order to select and recruit interviewees, resulting in four broad groups of stakeholders (see online supplementary material 1): (a) MSP officers from various governmental agencies who managed the MSP process (i.e. the Maritime Administration), (b) stakeholders invited in line with Polish legislation to participate in the process, some of whom either did not participate very actively or refused to participate (this group was composed of terrestrial spatial planners and scientists), (c) stakeholders who were invited, participated but showed dissatisfaction with the process and/or outcome, (d) stakeholders who were not invited or did not participate but have clear maritime stakes i.e. non-represented stakeholders (mainly SSF communities, but also coastal citizens, youths and tourists). The sampling strategy was adopted to gain insights into the experiences and perceptions of MSP-participating actors, and the values, needs and concerns of non-participating MSP stakeholders who have a relationship with the sea. We also sought marginalized actors’ ideas about how MSP could better strengthen their wellbeing relationships with the sea (interview questions are presented in online supplementary material 2). The interviews were recorded, transcribed, anonymized and subsequently translated into English and coded into themes reflecting our theoretical framing.

4. Background: MSP context in Poland

In Poland, MSP provisions are laid down in the 1991 Act Concerning the Maritime Areas of the Polish Republic and the Maritime Administration (hereafter: the Act). The Act was updated in 2003, and later in 2015, to specify the legal basis and goals, as well as procedural requirements linked to the development and assessment of the Polish MSP. The amended Act introduced the following guiding principles for planning the Polish sea: (i) ensuring sustainable development of the maritime sector including environmental, social and economic dimensions; (ii) ensuring national security and defence; and (iii) providing opportunities for coordinated action between different sea users.

A team of planners prepared the first national plan, under supervision of the Maritime Office in Gdynia in conjunction with Maritime Offices in Szczecin and Słupsk (hereafter: Maritime Administration). The plan was adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers in April 2021. It covers the entire Polish sea area including internal waters, the territorial sea and exclusive economic zone, but not the lagoons and port area waters, which are subject to more detailed plans since spatial conflicts are expected to be more prominent in the coastal vicinity (Zaucha Citation2018). In addition to the overarching goals specified in the Act, the plan contains detailed objectives focusing on reserving sea areas for future uses, strengthening the competitiveness of Polish seaports and enhancing the maritime economy. Development of the Polish MSP was divided into two steps: (i) preparation of a stock-taking report (2015-2016), and (ii) preparation of a draft plan (2016–2019). The first step was designed to provide a knowledge base for the subsequent planning phase.

The second step (2016–2019) culminated in successive draft plans (). The first stage focused on conflict analysis and the allocation of sea space to priority uses. This provided the basis for preparing ‘draft 0′ containing a proposed zoning pattern which, after public debates, resulted in ‘draft 1′. ‘Draft 1′ contained a detailed list of proposals of prohibitions and limitations for each marine zone. Debating this draft in conjunction with the Strategic Environmental Assessment led to ‘draft 2′, which was also debated and updated into ‘draft 3′. The latter was submitted to the EspooFootnote1 transnational consultation process, and the resulting ‘draft 4′ was presented to and adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers. Public engagement took place in the framework of four national conferences. Besides these formal processes, several less formal meetings were organised to discuss conflicts and synergies between uses, including meetings with ministries and national agencies and three meetings with international stakeholders following Baltic Sea regional HELCOM-VASAB guidelines on transboundary consultations, public participation and co-operationFootnote2. Key issues arising from the various discussions related to the location of offshore wind farms (OWFs), cables, port development, hydrocarbon mining and construction of coastal tourism infrastructure.

5. Results/analysis: misrecognition, misrepresentation, maldistribution and capabilities in Polish MSP

Following our conceptual premise that the root of societal inequalities is structural, we anchor our results/analysis on recognition, which enables us to unravel processes of misrecognition and effects on representation, capabilities and fair distributions of responsibilities, risks, burdens and benefits across marginalized groups. Therefore, our point of departure is the legal foundation for Polish MSP practice.

5.1. Misrecognition: empowering the powerful over the weak

Poland’s planning regulation, the Act, sets out what factors need to be considered in planning, who can participate in the planning process and on what basis, how stakeholders are to be invited and with what level of influence. In general, anybody can contribute to the plan by submitting suggestions, information and opinions. However, the Act gives more weight to public authorities, who can be grouped into two broad categories that define and assign different degrees of influence: (i) those with the right to agree or object to the plan, and (ii) those with the right to submit opinions on draft plans ().

Table 1. Public authorities recognized and empowered by law in the MSP process.

Considering the above, three implications for political voice (procedural justice) can be made. First, while planning regulation augments the power of both categories of public authorities, those with powers to consent/object are more empowered than those with legally given rights to submit opinions. Second, formal recognition of public authorities makes their position much stronger in terms of enabling better access to, and influence in, MSP decision-making when compared to what we shall call “non-MSP legally empowered” groups (e.g. non-governmental organizations, civil society, the public and others). This is captured by the following quote by a marine planner:

The authorities indicated in the Act as having consenting power on the plan have an advantage… over other stakeholders. They have a stronger bargaining power than the general public. [MSP Planner2]

One statement from… the navy, that this is our space and that’s it, and it ended everything. [Scientist3]

I also had the impression that the stakeholders related to national defence, that is, the army, also had a slightly privileged position. There, I did not notice a tendency to dialogue, but rather they simply communicated their needs and what should be taken into account. [National Agency]

For national security reasons, interaction with the defence sector sometimes took the form of exclusive, bilateral discussions in closed spaces with MSP authorities.

Even from what I remember, at one of the meetings, officers from the Navy appeared for a while, greeted us, and then went to talk to the director in a separate room… Later we were told that it was about hidden, secret, confidential training grounds. But the first impression was that there are two qualities [of stakeholders]. [Big enterprise]

As a third implication of misrecognition for procedural justice, because the source of power of governmental authorities in MSP is structural, planners have very limited power vis-à-vis those at the procedural level. Besides this assertion having a strong theoretical basis, the experience of planning by a marine planner adds an empirical dimension to it. This planner wondered:

Undoubtedly, it would be nice if everyone could have equal power in the planning process. [But] the planners do not create these power imbalances. Can this be solved by them? I do not know. [MSP Planner]

At least planners tried to take into account everyone’s interests. I have not seen any form of discrediting or special preference … just such a rational approach to embrace everything, to try to take into account the interests and demands of everyone. [Scientist3]

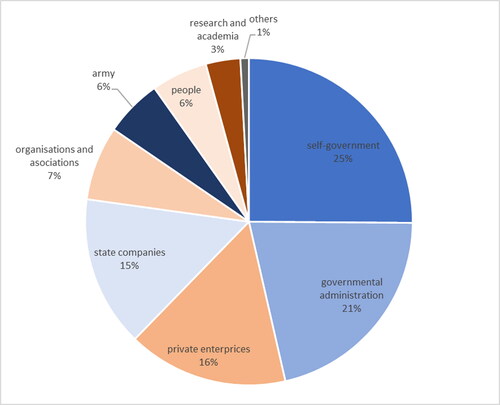

The argument that regulation augmented the power of governmental actors at the Polish MSP procedural level is also supported by the percentage of submissions they made to different MSP draft plans. shows that of a total of 9 broad stakeholder groups that submitted comments to draft plans, 52% of all submissions came from three public authorities alone; that is, government administration (21%), local self-elected government (25%), and the Navy (6%). The remaining 48% of all submissions were shared among 6 (non-MSP legally empowered) groups. Furthermore, a substantial share of submissions within the latter category came from powerful groups, that is, state-owned companies (15%) and private companies, mainly involved in wind energy production (16%), while organizations and associations (including fishers, wind energy, conservation), individuals, scientific institutions and others respectively shared only 7%, 6%, 3%, and 1%.

5.2. Communicating to “big” actors and misrecognizing the public

So far, we have highlighted three procedural implications following from legal augmentation of the power of public authorities. Another finding that explains why public authorities had influence over other stakeholder groups relates to communication strategies, which are also largely a regulatory issue. Indeed, early on, information on starting the planning process was, as specified by law, published in traditional newspapers, on the internet (websites of Maritime Administration) and distributed by post to representatives of key sectors that were legally recognized as having a stake. Planning authorities recognized this practice as potentially exclusionary of the public.

The average person would have a problem to catch up with this process, because in order to be informed about it, you have to either follow… specific websites, specific newsletters, or some industry portals…. [Terrestrial Planner 1]

The claim that communicating information about MSP through regular channels risks excluding the public, thereby cutting them off from important information about MSP (e.g. planning goals, topics, modes, dates and spaces of engagement) was reinforced by some non-participating stakeholders, who note that they seldom consult regular MSP communication channels.

I don’t really look at the website of the maritime office. [Tourist2 Sailor]

As a city planner, I was not excluded, because we received a notification. We had materials available on the website of the Maritime Office, or we participated in meetings…. But as a resident, I have not actually seen information anywhere else. [Local Planner]

In some cases, information about MSP was sent to the required institutions such as universities, but the latter failed to forward it to relevant staff.

The University was notified, but at least to my level as an academic teacher associated with the department that deals with planning issues, such information was never officially forwarded. [Scientist3]

Recognizing the limits of the communication strategy, planners made some steps toward closing the gap with the public. This involved rolling out intuitive, less formal one-on-one and group meetings with various local sectors.

We started with the authorities specified in the Act, but later we focused on local companies or associations or some organizations… The law only requires public discussions in the form of a consultation meeting [… but], we did many other meetings: presentation of the conditions study… and later, before the public discussion, there were probably three or four more meetings. There were probably only two with communes and with fishermen and probably with tourism…. [MSP Planner2]

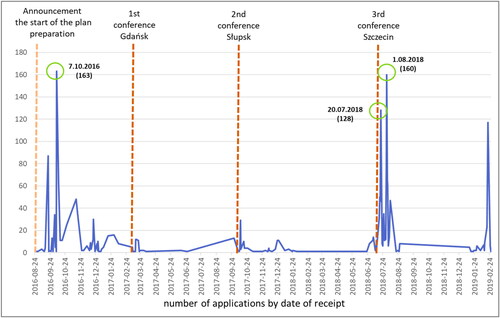

5.3. Procedural injustices: “closed” space of participation, time and resource constraints and group fragmentation

In the previous sections, we have shown how “big” actors were structurally empowered in the Polish MSP. In this section, we consider the procedural implications for the misrecognized. A key point to make is that influential actors with structurally given power were invited to share their knowledge with the planning team through submitting proposals that would form the basis for starting the planning process. Incidentally, this early process, which took place in 2016, received the highest number of submissions (i.e. 163) when compared to other invited spaces, as shown in . The implication is that, to the disadvantage of weaker groups, these powerful actors (the majority of whom wield significant economic, political and institutional power) may have significantly shaped the conditions and direction of MSP during this early, “closed” space of participatory MSP. This is because this early process corresponds to agenda-setting, where the objectives and priorities of MSP are often set, which is seen as effectively giving some actors a two-dimensional power advantageFootnote3 over others (Tafon, Saunders, et al. Citation2019a). Thus, despite the proactive steps taken by planners to open up more invited spaces for local stakeholders in the later stages of planning, it is possible that their concerns would only be secondary to those of the strategic sectors who shaped MSP in the early planning stage.

Figure 4. Public submissions to Polish planners during MSP plan developmentFootnote4.

Besides powerful stakeholders influencing the direction of MSP in the early stages, the public was also under-represented in subsequent planning stages. Despite organising several informal meetings, participation was dominated by stakeholders who had time and resources to do that. This was due to technical reasons relating to communication methods, but also to issues of time and resources constraining the active engagement of weaker stakeholders.

But I still have the feeling that this plan did not reach ordinary people […] who ultimately make use of the sea in some ways…. But I do not know how to [make them] participate in something like MSP, especially in such a large, formal process. [MSP Planner]

Society is very neglected. It is the weakest player these days. [Student 2]

Another key barrier to effective participation is group fragmentation. In Poland, some sectors such as local tourism and small-scale fisheries are largely fragmented and disorganized, compared to the more structured shipping, OWF and other sectoral groups. Group fragmentation is thus regarded as a challenge to procedural justice, as expressed by a local resident.

And when it comes to tourist entities, they are so scattered and fragmented that it is probably difficult to invite each individual stakeholder […]. It is similar with fishermen. There are many fishermen […]. They are not taking part in it. [Local Resident]

5.3.1. Neglecting small-scale fishers

In this section, we focus on the implications of misrecognition for SSFs, given that previous literature (Tafon, Saunders, et al. Citation2019) identifies them as Poland’s most vulnerable ocean group. Planners too, through the stock-taking report (the Study) identified SSFs as the most vulnerable coastal group needing 1) protection because of increased decline in small-scale fisheries over the years, and 2) capacity building due to their inability to organize themselves as a collective in marine decision-making processes. Based on these insights, Polish maritime authorities commissioned additional studies devoted to SSFs. However, despite these efforts, the result of interactions with SSFs in subsequent MSP processes did not support recognition of their vulnerabilities or capability-enhancing needs. Rather, MSP, like previous marine governance practices, was felt by SSFs as a management system designed to ensure enforcement of pre-determined projects relating to OWFs and marine protection.

Windmills are generally controversial […]. And I tried to get information at one of the meetings, but this was the answer I got: that it had been agreed in advance and there is no point in discussing it. [Western Polish Territorial Sea Fisher]

There are conferences, for example on harbour porpoises, and we have participated online in these conferences, but any of our arguments, whatever, was simply overlooked because the most important thing is simply to protect the harbour porpoise, which no one [fisherman] here has seen […] for over 20 years. [Coastal fisher]

Now we feel like small, irrelevant users of the Baltic Sea who simply have to remove themselves and make room for huge amounts of money. [Fishing Cooperative]

Besides the sentiment of being disregarded or treated unfairly in the marine governance process, SSFs were also often lumped together with industrial fishers during planning as if Poland’s fishery were a homogenous sector. This often led to cacophonous and unproductive debates with industrial fishers.

About the fishermen: the meetings were held in several different places with fishing groups. Every group has a different opinion. It was not really possible to make them discuss the matter with each other, because they were furious. For instance, the coastal fishermen and those fishing farther from the coast had slightly different wishes. [MSP Planner]

Some respondents took cacophony as a sign that SSFs were a powerful group.

From what I saw, fishermen were a very strong group. It was undoubtedly one group that was loud. They did not always speak on the merits, because they just wanted to be visible. [Researcher 2]

Yet, others believe that lumping SSFs together with industrial fishers effectively drowned the voices of SSFs, rendering their communication ineffective. However, SSFs themselves are heterogenous and cannot be regarded as an internally coherent group on all matters of values and interests.

It seems to me that the area that is a bit neglected is fishing and fishermen, but I am not able to identify what is the reason, only that… I do not feel in their voice, such unity… speaking with one voice. It seems to me that the problem was that they were quite a divided group and because of that maybe were less effective. [National Agency]

5.4. Distributive implications

While the stakeholder perceptions and experiences analysed indicate how structural misrecognition led to misrepresentation of weaker groups in MSP, they also point to potential distributive impacts. We emphasize the word potential because concrete distributional effects are not possible to map out until some years after MSP implementation. While interviews with planners reveal that distributive justice was not explicitly considered in the MSP process, interviews with other actor groups reveal varied perspectives about potential distributive effects of MSP to misrecognised groups. The defence sector, as we have seen earlier, seems to be a key winner. Others include large scale interventions such as OWFs, as traditional sea users such as fishers and residents are required to make space for this newcomer. Undoubtedly, society at large will benefit from the defence sector through national security, and from OWFs through sufficient and relatively clean energy, both of which have proven challenging recently given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and increased weaponization of energy supplies. Yet some interviewees reflected that while the socio-spatial costs of OWFs are borne by society, especially people in close vicinity of OWFs, key financial profits from OWFs will only accrue to developers and investors. These actors shared sceptical views about ultimate balance: costs and risks are distributed but financial profits are clustered. For these actors, planning was experienced as little more than a zero-sum game, in which bigger actors are the winners and weaker actors are the losers:

For sure, when we have large OWFs, a large part of the costs are now distributed to society. The profits, on the other hand, are not evenly distributed. [Scientist 4]

We know that there are some priorities, and energy is the strategic one. And fishing, which produces little GDP, is doomed to failure in this context. [Fishing Cooperative]

I know the fishermen are dissatisfied […]. They’re going to have areas excluded from fishing, so they’re definitely dissatisfied unless they’re compensated […] and the tourist group is concerned because it is afraid of visual…. pollution. [Local Resident]

The communes took the floor, but not all of them; many did not feel competent enough to identify various dangers posed by the plan for them. [Terrestrial Planner1]

Other actors believe that those with specialized knowledge and skills to understand geotechnical data such as maps are more able to participate effectively than those without such skills, thereby limiting possibilities to draw benefits or to minimize potential risks.

We, having the necessary competences and people dealing with maps and data, were able to put information on the map […]. I think this could be a big limitation for smaller entities that did not have such resources. [Big Enterprise]

On their part, SSFs see themselves as the ultimate losers who have to make space for OWFs and conservation interests and whose activity is also greatly constrained by different management regimes that place restrictions on what and how much should be fished.

The loss of sea areas that will be granted to wind turbines in the future is a tragedy for us…. The fisherman is expelled from the most fertile fisheries, so fishing is in a deteriorating condition. [Fishing Cooperative]

Generally [marine governance has] a strong emphasis on ecology, a great emphasis on limiting fishing quotas, and this has resulted in crowding out fishermen. [Coastal Fisher]

Finally, for SSFs, ceding of vital fishing grounds to OWFs may lead to a mad rush for available fishing grounds, potentially intensifying conflict among SSFs and overfishing in areas where fishing is allowed.

After the [wind] farms take the sea, fishing pressure will be in those places where catch is allowed. And it will often be the case that ships from Ustka, Łeba, Kołobrzeg, and Dziwnów will concentrate in one area. First, it is dangerous, and second […] this may induce local conflicts between fishermen. [Fishing Cooperative]

5.5. Building capabilities of SSFs and marginalized others

5.5.1. The planner’s role

The fact that misrecognition has structural roots raises the question of how structural injustices can be overcome to enhance the capabilities and wellbeing of marginalized coastal communities. At the procedural level, a capability-based recognition of SSFs and coastal communities would mean 1) mapping and integrating socio-cultural sensitivities; 2) addressing livelihoods threats, economic vulnerabilities and obstacles to participation (e.g. time, funding, logistics, incapacity to self-organize); 3) integrating socioecological values and knowledge systems; and 4) meaningfully taking account of aspirations of a sustainable future. This means recognizing that fishing and attachment to place (coastal, sea environments) are important and even constitutive of coastal identity and a flourishing life. Mapping multidimensional wellbeing relationships with coasts and oceans, both material and immaterial, should be seen as an indispensable first step toward a coastally just and equitable MSP and transformations to sustainability. This may mean using innovative engagement practices, such as arts-based participatory processes to better see and hear “themes of cultural, spiritual and traditional connections to the ocean and coast” (Strand, Rivers, and Snow Citation2022, 7) to inform future MSP and blue economy activities.

Planners should also strive to engage with SSFs separately from industrial fishers, as a means of gaining deeper understandings of their vulnerabilities, priorities and needs, which may be different from those of industrial fishers.

Contact with the fishing industry needs to be improved …. Meetings must be on point and purposeful, specifically devoted to a given type of fisher […]. They [industrial fishers] have different priorities, a different method of operation and fishing… and we coastal fishermen have different priorities. [Coastal Fisher]

This is not to say that SSFs will have uniform views about how sea values relate to collective capabilities – the heterogeneity of SSF groups and distinctive relationships with the sea suggests that relative importance given to different sea resources is likely to vary (for instance, between Kashubian fishers along the Hel Peninsula and those who fish on the Szczecin and Vistula bays).

Furthermore, planners should also adopt more user-appropriate and innovative approaches to communicating about MSP and ocean sustainability transformation activities. It is crucial that planners do not use technical jargon and refrain from simply informing citizens in vague terms that planning of diverse ocean-related activities will be undertaken. Rather, key information about MSP should be communicated early on, including the purpose of planning, modes of engagement, scope for influence and the potential socioeconomic and cultural effects of planning for citizens and communities.

So, it is necessary to first build this type of awareness among all stakeholders about how [the plan] will affect their lives, their quality of life, their dignity and economic conditions. [Local Citizen]

Maybe, you need to domesticate this process. Maybe you need to make it a little more human, less professional. [Terrestrial Planner1]

Innovative communication strategies could also include communicating through channels other than those stated in planning law. This could mean localizing MSP and ocean communication, e.g. through publishing information about blue economy/growth projects and related engagement modalities in local newspapers in the affected areas. Another strategy is digitalization of ocean and MSP information, which could mean communicating through diverse social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp etc. Like any other social topic, groups can chat about conservation issues and favorite tourism destinations, which can be used as an important supplementary knowledge base for planners to map out potential cultural and conservation hotspots. By localizing and digitalizing ocean communication, planners respond to the needs of current and older generations, and address some of the obstacles to effective community participation (e.g. time, logistics, funding, difficulties to express oneself orally, stakeholder tyranny).

But I have the feeling that it would be easier for everyone else to get involved, for example, [through] a chat: there you don’t need to speak at all, for example. It is also important for some people that they do not have to say anything, but write something instead. [Student1]

[…] taking part in a meeting in your city is not simple […]. Logistically, it [participation] is difficult for a natural person, i.e., for a stakeholder who is not organized and is not an entity or institution but simply a participant. [Local Citizen]

Communication through such portals as Trójmiasto.pl should work, because it is the first source of information for people. [Tourist2 Sailor]

Effecting the above changes would require allocating additional time and financial resources for project planning, monitoring and implementation, which was not properly considered in the Polish MSP. Furthermore, these required changes are transformative only to the extent that they address injustices at the procedural level. Many recognitional injustices, however, have structural roots and, therefore, require state intervention.

5.5.2. The role of the state

Addressing misrecognition in ways that build capabilities of SSFs may require the state to establish policies, enact laws, or deliver court decisions or memoranda of understanding that recognize, grant and protect territorial use rights for SSFs. The Polish government can draw inspiration from the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Small-Scale Fisheries (FAO Citation2015), which member states of the Food and Agricultural Organization endorsed in 2014. Recognizing SSFs as critical to food security and poverty eradication, the FAO Guidelines advocate a human rights approach to small-scale fisheries and spell out several capability-enhancing measures (e.g. secure tenure and access to fairer markets etc.) as critical to protecting the integrity and human rights of SSFs and in supporting their agency. The Guidelines also recognize SSFs as powerless vis-à-vis more formalized sectors and call on states to secure special protection for SSFs, as stated in paragraph 5.9

“States should recognize that competition from other users is increasing within small-scale fisheries areas and that small-scale fishing communities, in particular vulnerable and marginalized groups, are often the weaker party in conflicts with other sectors and may require special support if their livelihoods are threatened by the development and activities of other sectors” (FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization) Citation2012). Such a move treats SSFs as not just another interest group but acknowledges their special affiliation as social actors with specific place attachments and relationships to each other and the sea that are important for them to realize their capabilities. Reforming small-scale fisheries in this direction would better support the capabilities of SSFs to act with collective agency and to socially reproduce over time.

Of course, state intervention will take different forms, depending on context. Real life examples of state intervention exist that Poland can adapt to its context. In Estonia, for instance, following the country’s national MSP process, the government intervened and took concrete actions that recognize and strengthen the rights of SSFs vis-à-vis pressure from new maritime uses such as OWF. Specifically, the government suspended (until 2027) considerations of OWF development in marine areas that are crucial for fishing. The MSP plan also lays down over twenty conditions for the development of OWFs, including avoidance of overlap with traditional fishing, and development of mechanisms for the inclusion of coastal communities in the construction and maintenance of turbines, among others (Tafon et al. Citationforthcoming). While not granting legal tenure rights, this action at least recognizes that SSFs in Estonia are weak (in terms of forwarding their rights, values, knowledge, interests and aspirations in MSP) and require special protection and therefore, protects their rights to fishing grounds, albeit only temporarily.

Recently, EU Member States have been pushing for rapid and large-scale development of OWFs as a means to accelerate the switch to energy security and independence from an increasingly volatile and politically weaponized Russian energy. For Baltic states such as Poland, the need to wean the economy off Russian energy is particularly pressing and well justified, given the country’s communist legacy. Yet rapid renewables development is likely to result in further marginalization of SSFs in terms of loss of rights to fishing grounds, which may accelerate or worsen infringement on or erasure of human rights, sociocultural identity, livelihoods, community cohesion and food and economic security. Economic measures may remediate some of these impacts. For instance, given the precarity and economic downturn of Polish fisheries, the Polish government could take practical measures to increase the profitability of small-scale fisheries, which has been negatively affected by the decision by the EU Council in 2021 to reduce catch quotas of the most important fish species (e.g. cod, herring, and sprat). Some fishers note:

The challenge for fisheries is not lack of administrative will, it is generally about EU regulations…. There are new regulations, new restrictions, and it simply deletes us… The problem is ensuring the profitability of the vessels so that they can hire people. [Fishing Cooperative]

The biggest problem is the lack of access to fish, in terms of limits. How are we going to improve the economic result if [they] have cut the limits practically to zero…? […] Coastal fishing has become uneconomical. [Coastal Fisher]

We realize how strategic energy independence is…. The only thing we would ask is that you consider places that are fertile fishing grounds… Ideally, a more cooperative approach based on jointly designing the deployment of OWFs in order to combine them with other types of use, reduce their potential impact on fisheries [and] strengthen relationships between the relevant sectors. [Fishing Cooperative]

I understand this energy transformation […] I understand that it has to happen, and it will happen, but it should be more on a partnership basis between the fishing community and investors. [Western Polish Territorial Sea Fisher]

Furthermore, institutionalizing financial incentives for SSFs within the broader framework of the blue economy and energy transitions could also contribute toward more coastally equitable transformations to sustainability and energy security. For example, the Estonian government is currently revising its planning regulation to include mechanisms that support the provision of financial incentives to coastal communities in the ownership and maintenance of OWFs and ensure that their concerns are considered in OWF permit processes. Interestingly, this action aligns with recommendations contained in the revised Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security, which urges states to consider granting SSFs “just compensation where tenure rights are taken for public purposes” (FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization Citation2022, 4). A similar process could be initiated in Poland, with emphasis on local partnerships and integration of SSFs in OWF projects.

Finally, another key challenge to the sustainability of coastal communities and small-scale fisheries is the absence of ocean-based conflict resolution/transformation institutions. The Polish government could provide policy, legal and administrative frameworks that promote effective adjudication of tenure rights disputes, in line with paragraph 4.9 of the FAO Guidelines, which states: “States should provide access through impartial and competent judicial and administrative bodies to timely, affordable and effective means of resolving disputes over tenure rights…which may include a right of appeal, as appropriate” (FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization) Citation2022, 7).

6. Conclusion

The four-dimensional blue justice framework used to examine the Polish MSP has highlighted several structural and process-related factors that have resulted in the first iteration of Polish MSP heavily favouring and enabling the public sector and maritime industry (e.g. OWFs) while further marginalising or excluding the general public and key coastal actors, including SSFs, tourism and others. A key explanation is the insufficient embeddedness of justice concerns in the MSP legislation and plan.

The results show that structural (or formally institutionalized) reinforcement of the powerful over already marginalized stakeholders results in misrecognition and therefore capability deprivation for weaker stakeholders. This misrecognition flowed through to shaping MSP agendas of what was to be formally discussed, who got to be represented and active in discussions, on what terms, and with what influence. While these forms of misrecognition result from Polish legal frameworks, our results show that marginalization also has roots in structures beyond the nation state, such as in the case of EU-related restrictions on fishing of important species in the Baltic Sea, which undermines the profitability and survival of Poland’s SSFs. One approach to overcome this structural problem discussed here and adopted in other small-scale fisheries contexts (e.g. Chile, South Africa, Spain) would be to more formally recognize SSFs’ different historic rights, such as territorial use rights, catch quota rights etc. Such an approach would more formally institutionalize recognition of SSFs within MSP.

Furthermore, notions of planning to support a living coast that harbours the multidimensional wellbeing of coastal residents and key social groups in relation to their environment that was spelled out in the Stocktaking (preplanning) phase of Polish MSP were found to have faded away in the course of planning. The adverse social justice effects of the formalized emphasis on prescribed large-sector stakeholders were tangible, despite some efforts by planners (which could have been further augmented) to reach out to less organised or less empowered actors.

There was also no explicit consideration of the distribution of benefits and costs at any stage of the MSP process. That is, there has not been an informed calculation of the distributed flows of effects to public or private sectors and/or different social groups, including those most affected or marginalized. Instead, the Polish MSP seemed to be underpinned by implicit assumptions about pursuing a common or national good, based mostly on favouring strategic and legally prescribed sectoral interests. We have argued that this led to acts of misrecognition and misrepresentation toward coastal actors, most importantly SSFs. That said, arguably broader national benefits will be accrued through the preferencing of public goods in terms of national security and renewable energy capacity, among others. In terms of the latter, OWF investors and developers will also accrue benefits through preferential planning treatment, although this is not acknowledged by planners.

The findings point to the need for planners and policymakers to rethink the decoupling of sea and land and move toward a relational ontology in which MSP and different sustainability transformation activities are embedded in, and have effects across, species, place, scale, space and time (Garland et al. Citation2019). In response to these insights into Polish MSP practice, we have argued that a capability-based approach is able to support integration of the multidimensional aspects of wellbeing in relation to the coast/sea. Adopting a capability-based approach would require emphasizing sociocultural, economic and livelihood connections to the coast/sea and effectively recognizing them in MSP, the blue economy and other ocean sustainability transformation activities. This would increase stewardship towards the coast/sea, since people’s multidimensional relationships are recognized as embedded in contextual seascapes that are integral for their wellbeing. This would, in turn, contribute to building a more coastally just and equitable MSP, beyond its current predilections toward strategic state/private imperatives. To further harness the multiple social, environmental, blue growth and climate benefits of the ocean and coasts, MSP legal frameworks and planning procedures need to shift from simply strengthening the influence of the powerful, toward embracing a capability-based approach that recognizes uneven distributions of economic, political and mobilizational power and takes concrete steps to level the playing field for historically marginalized actors, such as SSFs. This suggests that planners and policymakers can still be focused on public value but be more mindful that this depends upon public trust and acceptability for its success. That is, they need to be able to listen carefully and differently, allowing publics to pose difficult questions, being responsive to those questions in planning dynamics and outcomes, and letting this dialogue inform the planning ‘balance’ (Yellow Book Citation2017). This especially relates to those social groups that have been marginalized and excluded. Otherwise, there is a danger that needed strategic imperatives, such as offshore wind energy, get locked into interminable conflict as marginalized groups mobilize opposition to the public value arguments (Tafon, Saunders, et al. Citation2019).

Finally, building on the four-dimensional blue justice framework developed in this paper, future research would benefit from engaging empirically with different practices of (mis)recognition and their multidimensional wellbeing effects for variously marginalized justice subjects (e.g. women, SSFs, indigenous communities and non-human Others) whose capabilities are increasingly eroded by anthropogenic climate change, as well as climate mitigation and ocean industrialization-related poverty, human rights violations, habitat destruction, small-scale fisheries marginalization, cultural erosion and community destabilization. Future blue justice research should also develop the framework further in dialogue with empirical analysis of multispecies blue justice in different policy and planning contexts, alongside development of innovative methods for engaging more-than-humans in sustainability transformation research. How vulnerable communities, grassroots movements and local ocean stewards and defenders respond to socioenvironmental threats and/or seek to steer people-centred, nature-positive MSP and transformations to sustainability, and with what enabling factors and impediments, should also be at the centre of this promising line of scholarship, as should be explorations of tensions and trade-offs between social justice and justice for non-humans, in terms of the added complexities that a more-than-human approach potentially brings to social justice aspirations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Espoo Convention is a United Nations Economic Commission for Europe convention signed in Espoo, Finland in 1991 that came into force in 1997. It sets out the obligations of Parties to carry out environmental impact assessment of certain activities at an early stage of planning and to notify and consult each other on all major projects under consideration that are likely to have a significant environmental impact beyond national borders.

2 Developed by HELCOM-VASAB MSP Working Group, a joint co-chaired working group established in 2010 to ensure cooperation among Baltic Sea Region countries for coherent regional MSP processes in the region.

3 A two-dimensional power advantage is where one group has power to (de)limit the scope of what is debated, thereby confining decision-making to issues that are deemed safe, appropriate or worthy with the implication of structurally excluding groups (and their concerns) not represented.

4 The high number of submissions in 2018 results from proposals but also from the consultation of plan v.1. Applications submitted in early 2019 correspond to consultation of plan v.2. The v.3 version was submitted to the ESPOO consultations and then national legislation process.

References

- Axon, S., A. Bertana, M. Graziano, E. Cross, A. Smith, K. Axon, and A. Wakefield. 2022. “The U.S. Blue New Deal: What Does It Mean for Just Transitions, Sustainability, and Resilience of the Blue Economy?” Geographical Journal. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/geoj.12434.

- Bennett, N. 2022. “Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean.” Frontiers in Marine Science 10: 1–6. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.873572.

- Bennett, N., J. Blythe, C. White, and C. Campero. 2021. “Blue Growth and Blue Justice: Ten Risks and Solutions for the Ocean Economy.” Marine Policy 125: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387.

- Celermajer, D., D. Schlosberg, L. Rickards, M. Stewart-Harawira, M. Thaler, P. Tschakert, B. Verlie, and C. Winter. 2021. “Multispecies Justice: Theories, Challenges, and a Research Agenda for Environmental Politics.” Environmental Politics 30 (1–2): 119–140. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1827608.

- Domínguez-Tejo, E., and G. Metternicht. 2018. “Poorly-Designed Goals and Objectives in Resource Management Plans: Assessing Their Impact for an Ecosystem-Based Approach to Marine Spatial Planning.” Marine Policy 88: 122–131. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.013.

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization). 2012. The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. Rome: FAO.

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization). 2015. Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Rome: FAO.

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization). 2022. The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security. Rome: FAO.

- Flannery, W., J. Clarke, and B. McAteer. 2019. “Politics and Power in Marine Spatial Planning.” In Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future, edited by Zaucha, J. and K. Gee, 201–217. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fraser, N. 2009. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fraser, N., and A. Honneth. 2003. Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange. London: Verso.

- Fulfer, K. 2013. “The Capabilities Approach to Justice and the Flourishing of Nonsentient Life.” Ethics and the Environment 18 (1): 19–38. doi:10.2979/ethicsenviro.18.1.19.

- Garland, M., S. Axon, M. Graziano, J. Morrissey, and P. Heidkamp. 2019. “The Blue Economy: Identifying Geographic Concepts and Sensitivities.” Geography Compass 13 (7): 1–21. doi:10.1111/gec3.12445e12445.

- Germond-Duret, C., P. Heidkamp, and J. Morrissey. 2022. “ (In)Justice and the Blue Economy.” Geographical Journal. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1111/geoj.12483.

- Honneth, A. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Kelly, M. 2022. “Beyond Stakeholder Engagement in the Coastal Zone: Toward a Systems Integration Approach to Support Just Transformation of the Blue Economy.” Geographical Journal. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1111/geoj.12452.

- Louey, P. 2022. “The Blue Economy’s Retreat from Equity: A Decade Under Global Negotiation.” Frontiers in Political Science 4: 999571. doi:10.3389/fpos.2022.999571.

- Lynch, M., and M. Long. 2022. “Green Criminology: Capitalism, Green Crime and Justice, and Environmental Destruction.” Annual Review of Criminology 5 (1): 255–276. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-114647.

- Morrissey, J. 2021. “Coastal Communities, Blue Economy and the Climate Crisis: Framing Just Disruptions.” Geographical Journal. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1111/geoj.12419.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2006. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Robeyns, I. 2020. “Wellbeing, Place and Technology.” Wellbeing, Spcae and Society 1: 100013. doi:10.1016/j.wss.2020.100013.

- Saunders, F., M. Gilek, A. Ikauniece, R. Tafon, K. Gee, and J. Zaucha. 2020. “Theorizing Social Sustainability and Justice in Marine Spatial Planning: Democracy, Diversity, and Equity.” Sustainability 12 (6): 1–18. doi:10.3390/su12062560.

- Saunders, F., M. Gilek, and R. Tafon. 2019. “Adding People to the Sea: Conceptualizing Social Sustainability in Maritime Spatial Planning.” In Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future, edited by Zaucha, J. and K. Gee, 175–199. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schlosberg, D. 2013. “Theorising Environmental Justice: The Expanding Sphere of a Discourse.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 37–55. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.755387.

- Schlosberg, D. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, G. 2015. “Creating the Spaces, Filling Them Up: Marine Spatial Planning in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters.” Ocean and Coastal Management 116: 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.07.003.

- St. Martin, K., and M. Hall-Arber. 2008. “The Missing Layer: Geo-Technologies, Communities, and Implications for Marine Spatial Planning.” Marine Policy 32: 779–786. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2008.03.015.

- Strand, M., N. Rivers, and B. Snow. 2022. “Reimagining Ocean Stewardship: Arts-Based Methods to ‘Hear’ and ‘See’ Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Ocean Management.” Frontiers in Marine Science 9: 1–19. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.886632.

- Tafon, R., B. Glavovic, F. Saunders, and M. Gilek. 2022. “Oceans of Conflict: Pathways to an Ocean Sustainability PACT.” Planning Practice and Planning 37 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1080/02697459.2021.1918880.

- Tafon, R., F. Saunders, and M. Gilek. 2019. “Re-Reading Marine Spatial Planning through Foucault, Haugaard and Others: An Analysis of Domination, Empowerment and Freedom.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 21 (6): 754–768. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1673155.

- Tafon, R., D. Howarth, and S. Griggs. 2019. “The Politics of Estonia’s Offshore Wind Energy Programme: Discourse, Power and Marine Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37 (1): 157–176. doi:10.1177/2399654418778037.

- Tafon, R. 2019. “Small-Scale Fishers as Allies or Opponents? Unlocking Looming Tensions and Potential Exclusions in Poland’s Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 21 (6): 637–648. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1661235.

- Tafon, R. 2018. “Taking Power to Sea: Towards a Post-Structuralist Discourse Theoretical Critique of Marine Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36 (2): 258–273. doi:10.1177/2399654417707527.

- Tafon, R., F. Saunders, T. Pikner, and M. Gilek. Forthcoming. “Transition Politics in an Era of Blue Growth, Energy Security, and Decarbonization: Implications for Wind Energy Conflict Transformation, Multispecies Justice and Capabilities.” Maritime Studies.

- Tschakert, P. 2022. “More-than-Human Solidarity and Multispecies Justice in the Climate Crisis.” Environmental Politics 31 (2): 277–296. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1853448.

- UNESCO-IOC/European Commission. 2021. MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning. Paris: UNESCO. (IOC Manuals and Guides no 89).

- Zaucha, J. 2018. “Methodology of Maritime Spatial Planning in Poland.” Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology 19 (2): 713–720.

- Yellow Book. 2017. Barriers to Community Engagement in Planning: A Research Study. Edinburgh: Yellow Book.