Abstract

Since 2001, the Indonesian government has formulated and implemented several restoration programs to improve the Citarum’s water quality. However, these programs were often contested, particularly concerning the meanings of ‘water quality’ and how those informed approaches to responsibility and involvement. This paper problematises river restoration in view of these controversies towards improving people’s lives and their environment. Our investigation found (1) a selective use of scientific knowledge of water quality and related responsibilities; (2) a tension between broader inclusion and military involvement in river restoration; and (3) a diverse host of informal restoration practices that largely remain unnoticed in view of the government programs. The findings indicate that river governance can benefit from recognising and tuning into below-the-radar restoration practices to tackle river pollution.

1. Introduction

Improving water quality represents an international development priority. The 2030 UN Agenda for Sustainable Development aims to improve water quality by reducing dumping, pollution, chemical materials and untreated wastewater (UN Citation2019). However, population growth and intensified anthropogenic activities still continue to degrade biodiversity and quality of life. Rivers in the Global South continue to deteriorate, despite sustained restoration efforts (FAO and IWMI Citation2018).

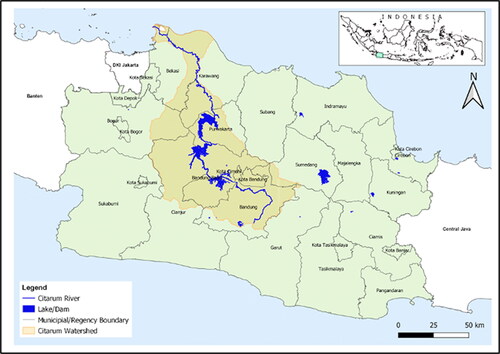

Restoring rivers comprises interventions to improve river conditions such as riverine habitat, recreation and water quality (Wohl, Lane, and Wilcox Citation2015). In Indonesia, the government has implemented restoration programs for rivers nationwide, one of which is the Citarum, West Java’s primary waterway (). More than seventeen million people depend on the river as a vital source for the irrigation of rice fields, local industries, energy production and biodiversity. Despite these essential roles, the river is also a waste disposal outlet for users such as households, industries and farmers.

Figure 1. Map of the Citarum river and its watershed in West Java province. Source: Development Planning Agency, Government of West Java Province, 2019.

Since 2001, successive governments have designed flagship programs to address river pollution. As of 23 March Citation2018, Kumparan listed on its website that efforts to clean the river started through the Citarum Bergetar program (2001), followed by other restoration programs, namely, Citarum Terpadu (2008) and Citarum Bestari (2013) (Kumparan Citation2018). Each program took on specific targets. Citarum Terpadu drew on long-term solutions to pollution, flooding and illegal land use conversion. When the program received fierce criticism for its emphasis on infrastructure projects, it was terminated (Interview with an activist, 27 February 2021). Thereafter, the Citarum Bestari adopted a focus on behavioural change and technical solutions, via projects such as ecovillages, and even the high ambition of making the Citarum water potable within five years (Interview with a public official, February 18, 2021; see also Merdeka, 6 February Citation2013).

Despite these restoration programs, river pollution persisted. Many residents and activists criticised the government restoration programs for prioritising pollution indicators and engineering solutions, and for organising participation only on the governments’ terms. For instance, as noted in a Kumparan article on 23 March 2018, environmental activists claimed that these programs, in fact, marginalised non-governmental actors.

In 2017, international media flagged the Citarum as one of the world’s most polluted rivers (BI and GCS Citation2013; see Make a Change, November 15, Citation2017). This pressured the government to launch yet another restoration program, Citarum Harum (2018), to improve water quality by 2025 (CT Citation2019).

1.1. The role of knowledge in river restoration

River restoration inevitably involves diverse ways of knowing (Sneddon, Magilligan, and Fox Citation2017). Multiple studies have specifically explored the role and transformation of knowledge (e.g. Rydin Citation2007; Van Assche et al. Citation2011), the struggle between knowledge claims (e.g. Buchanan Citation2013; Colebatch Citation2015; Sneddon, Magilligan, and Fox Citation2017), and the performativity of knowledge in particular (e.g. Arts et al. Citation2014; Callon Citation2007; Law Citation2009; Turnhout Citation2018; Turnhout, Dewulf, and Hulme Citation2016; Turnhout et al. Citation2020; Wesselink et al. Citation2013). Hence, our research regards forms of knowledge as situated (Haraway Citation1988), and questions how these shape river governance strategies in the Citarum.

The Citarum’s case is not that different from others where scientific knowledge is instrumental in classifying water quality as either ‘polluted’ or ‘clean’. Across the globe, this has fostered various debates among authorities, local activists and communities on the meanings of water quality (Choudhury, Mahanta, and Mahanta Citation2018). Here, we focus on how the presumably neutral role of scientific knowledge informs certain views of responsibility for polluting and subsequently restoring the Citarum.

The starting point of our exploration is the contestation over various forms of knowledge of river restoration (see Wesselink et al. Citation2013). We explore the resulting discursive space to discern its implications for current and future river governance, particularly when it concerns questions of water quality, responsibility and involvement.

We draw on three main insights: (1) how contestations over river restoration reveal different meanings of water quality; (2) how these different meanings shape particular views of responsibility and involvement; and (3) how the resulting discursive space accommodates restoration practices.

Our paper sets off by elaborating on discourse and discursive space, understood in terms of knowledge performativity. We will also review current debates on water quality, responsibility and involvement. Then the main findings will be discussed, along with the implications for future river restoration efforts.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Performative aspects of discourse and knowledge

Drawing on discourse approaches to investigate multiple knowledges, we took inspiration from Hajers’ oft-quoted definition of discourse: “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts and categorisations that are produced, reproduced and transformed in a particular set of practices, and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities” (1995, 44). This means that the content of what is said, such as ideas and categorisations of water quality that appear across a range of texts, are linked to practices that produce or reproduce this content. It also defines what is considered relevant ‘knowledge’. How a topic is discursively constructed can legitimise some actions and delegitimize others. Discourse thus influences discussions and articulations of a topic and regulates its practices (Hall Citation1997; Hussein Citation2017, Citation2019; Edwards Citation2013).

Further, our inquiry draws on the notion of discursive space. The idea of discursive space emerges as a response to spatial planning practices and theories that embrace the idea of stakeholder engagement towards achieving consensus. Critics of the consensus-based approaches argue that the latter conceal the political in decision-making. On the contrary, matters of contestation, disagreement and difference show how choices are made and hence a political dimension. Such matters are conducive to the emergence of discursive spaces, whereby genuine differences (Metzger, Allmendinger, and Oosterlynck Citation2014) and those whose voices are distorted or silenced (Rancière Citation1996) can become manifest. Their inclusion in a (metaphorical) discursive space thus fosters, according to these authors, mutual criticism, recognition and, ultimately, respect (see Mouffe [Citation2005, Citation2013] on agonistic democracy).

The idea of discursive space has inspired various studies, such as those focussed on climate policy (e.g. Lövbrand Citation2011), the interplay between science and policy (e.g. Wesselink et al. Citation2013), the politics of knowledge (e.g. Turnhout Citation2018) and participatory governance (e.g. Fischer Citation2006). They argue that discursive spaces provide opportunity for critical scrutiny and contestation (Turnhout Citation2018), policy deliberation (Lövbrand Citation2011) and discourse formation at the science-policy interface (Wesselink et al. Citation2013). Unpacking this discursive space may prove productive for rethinking current approaches to river restoration and for asking how effective use can be made of such discursive space for governing the Citarum river.

In policy-making, Neumann (Citation2005) states that through the way knowledge is mobilised, discourse shapes priorities and produces social and environmental effects (see also Movik and Stokke Citation2015). Indeed, “knowledge is performative, because it impacts not just on how we understand the world, but also on how we act upon it” (Arts et al. Citation2014, 6; see also Callon Citation2007; Law Citation2009; Turnhout Citation2018; Turnhout, Dewulf, and Hulme Citation2016; Turnhout et al. Citation2020). Discourse is performative in shaping contexts and, as such, it affects society and the environment more broadly (Buchanan Citation2013; Nursey-Bray et al. Citation2014; Wesselink et al. Citation2013).

Looking at knowledge, or rather, ‘knowledges’ (Rydin Citation2007) and their implications in shaping different interpretations of water quality (in Bahasa Indonesia: kualitas air) means that we dwell on diverse sources and ways of knowing, articulating their situatedness (Haraway Citation1988). That is, we ask how knowledge is presented as neutral whilst being used to underpin choices made in the process of policy formulation and implementation that are not neutral at all (Rydin Citation2007; Turnhout, Dewulf, and Hulme Citation2016).

Hence, we employ a discourse lens to look into how contestation over river restoration shapes restoration governance, particularly how knowledges come into play and delineate discursive space. We are particularly concerned with discursive constructions of water quality and how these structure interpretations of responsibility. At the same time, we explore how the latter interpretations raise questions about stakeholder involvement in river restoration. We ask, in other words, how diverse knowledges are mobilised to create particular ideas of water quality, responsibility and involvement.

2.2. Water quality debates and discursive space

Worldwide, various measures are used to evaluate river restoration programs, whereby successful projects are found that focus on reducing the input of pollutants or nutrients into the river (Chittoor Viswanathan and Schirmer Citation2015). In addition to water quality, restoration is considered qua socioeconomic values (Perni, Martínez-Paz, and Martínez-Carrasco Citation2012), ecological aspects (Palmer et al. Citation2005) and sustainable development goals (Ezbakhe Citation2018). Ioris (Citation2008) argues that rather than spending most efforts on assessing restoration through scientific models and techniques, water governance should consider its political dimension (see Ioris Citation2008).

Considering the political dimension of water governance means appreciating how water quality has become discursively contested, and that knowledge is socially constructed (see Sharp and Richardson Citation2001). As such, understandings of water quality or other nature-related phenomena cannot be reduced to a scientific understanding but need to come with analysis of the ways in which other parts of society attribute meanings to phenomena. They require delving into everyday experiences that shape how people think and act (see Hajer Citation1995). This type of attention allows us to understand how particular groups of stakeholders have opportunities to shape interventions more than others (see Mehta, Huff, and Allouche [Citation2019] on politics of scarcity), by which they are able to reinforce their position in the discursive space while marginalising others. As we have already explained, we conceptualise the political in relation to ‘discursive space’, as the opportunity to debate, question and criticise how differences and disagreement can be articulated in ways that encourage mutual recognition and respect towards different stances (Mouffe Citation2005). For our case, we seek to understand how particular ideas of water quality which were defined and became embedded in the restoration programs may emphasise or downplay certain meanings and practices, and further benefit or marginalise associated stakeholders.

Sneddon and Fox (Citation2006) point out that water regulations continue to largely rely on a managerial perspective, and often ignore the controversies, dilemmas and challenges of public involvement in governing river restoration (Adams, Perrow, and Carpenter Citation2004; Lee and Choi Citation2012; Movik and Stokke Citation2015; Sneddon, Magilligan, and Fox Citation2017). For our paper, it is therefore important to understand the discursive space articulated by various conceptualisations of water quality through formal sources, such as governmental documents, as well as everyday experiences.

2.3. Responsibility

Our focus on contestation over meanings of water quality invoked important questions about those responsible for polluting and cleaning the river. Researchers in the field of environmental and water governance conceptualise responsibility in different ways. Here, we focus on conceptions of (i) duty-based responsibility (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007), including the notions of shared responsibilities (Snel et al. Citation2021; Speed et al. Citation2016; Wilson Citation1996) and duty dumping (Buchanan and Decamp Citation2006), and (ii) global and intergenerational dimensions of responsibility (Massey Citation2004, Citation2006; Popke Citation2003; Young Citation2006).

The first conceptualisation draws on traditional interpretations of responsibility as compliance with duty (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007). For Snel et al. (Citation2021); fulfilling one’s duty to mitigate floods is a legal responsibility. Our paper focuses on how governmental actors understand duty as specified via the restoration program and, subsequently, on the ways certain meanings of water quality shape practices of sharing and transferring responsibilities to other actors. To understand this, we examine how the government approaches responsibility concerning other, non-governmental stakeholders.

In addition to duty-based interpretations of responsibility, we have the notion of ‘shared responsibility’. For example, Wilson (Citation1996) discusses the shared responsibility of producers for managing the waste they produce rather than expecting consumers to pay for waste collection and disposal. On a different note, Snel et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate how public authority discourse on flood risk has shifted from the role of government bodies towards that of residents in increasing flood resilience. In our study, we are primarily interested in how governmental views of water quality create interpretations of shared responsibility and how these are (or not) brought into practice.

The notion of ‘duty dumping’ is particularly relevant here, and it entails the transfer of responsibility and related obligations to others without providing adequate reasoning for doing so (Buchanan and Decamp Citation2006). Working on global health, Buchanan and Decamp (Citation2006) argue that duty dumping diverts attention away from those failing to fulfil their obligations. Similar to Gunder and Hillier (Citation2007), who elaborate on duty dumping in planning, we look into how articulated meanings of water quality imply practices of duty dumping that are not always immediately visible.

The second conceptualisation of responsibility responds to the critique that expositions of responsibility as duty accomplishment neglect the fact that duty is socially constructed and deserves critical reflection (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007, 84). For instance, some authors contend that responsibility expands beyond spatial and temporal proximity and is far more geographically extensive than is often depicted (Massey Citation2004; Popke Citation2003). Responsibility to ‘distant people’ considered in connection to future generations (Young Citation2006) is yet another perspective we bring into our investigation. In so doing, we trace how debates in the Citarum construct a heterogeneous interpretation of responsibility, for instance, towards future-oriented and global dimensions of responsibility and how the latter interpretations inform restoration practices.

2.4. Involvement

Contestation over responsibility notably raises questions about involvement and how those shape restoration practices. Planning and decision-making on environmental issues have increasingly involved various publics in improving the legitimacy of the planning and decision-making processes (Turnhout, Van Bommel, and Aarts Citation2010), but the growing prominence of public involvement has also sparked much criticism. Cooke and Kothari (Citation2001) point to the importance of considering preconceptions about whom to involve, issues at stake and expected outcomes. Scott (Citation2011) problematises participation with respect to claims of empowerment and inclusivity, and how those could lead to marginalisation. This implies that formal involvement arrangements may exclude certain actors and knowledges underlying particular understandings of water quality, including related restoration efforts (see Ioris Citation2008; Turnhout, Van Bommel, and Aarts Citation2010). In problematising involvement, we therefore look at both formal and informal practices. Informal practices allow involvement beyond governmental arrangements, such as citizen initiatives to block illegal outfall pipes of allegedly polluting factories.

In investigating involvement in the restoration program, we follow Turnhout, Van Bommel, and Aarts’ (Citation2010) take on participation as performative practice, which inherently entails some form of selection and, as such, exclusion. Moreover, those taking part in river restoration are often confronted with certain expectations about their role and level of involvement (Leach, Scoones, and Wynne Citation2005; Mosse Citation2001). In summary, involvement is bound to assumptions about the issue at stake, the participants’ conduct and even expected outcomes (Turnhout, Van Bommel, and Aarts Citation2010, 26).

Building on these vantage points, we question how knowledge performativity shapes the meanings of a clean river, related conceptions of responsibility, and involvement towards restoration practices.

3. Methodology

An interpretive methodology (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012) with attention to discourse seemed particularly suited for investigating the diverse knowledges underlying river restoration debates. In short, it helped to untangle the different interpretations of a ‘clean river’ and how those informed particular views of responsibility and involvement. A word of caution is in order on the matter of language and translation. Our research participants associate ‘improving water quality’ with ‘cleaning-up’ and ‘control’. ‘Cleanliness’ appears in writings and discussions in Bahasa Indonesia, as stakeholders loosely refer to ‘river restoration’ as ‘to clean-up the river from pollution’ (membersihkan sungai dari polusi) and ‘to control river pollution’ (penanganan pencemaran sungai). ‘Cleaning-up’ and ‘cleanliness’ are commonly used to contest water quality. Most English versions of government websites use both ‘cleaning-up’ and ‘restoration’. Therefore, although we use the notion of ‘water quality’ throughout the paper, we also connect ‘water quality’ to the common references to ‘cleanliness’, particularly in analysing research materials.

For our research, we gathered secondary data from local to international media and policy documentation. Because of our interest in problematising water quality, responsibility and involvement, we focused on materials published from the start of restoration programs in early 2001 to 2021. We collected data from international, national and local media, governmental agencies (i.e. restoration-related regulations, action plans and other associated archives) and non-governmental actors (i.e. organisation reports on Citarum-related activities). Additionally, in January–April 2021, we conducted 14 semi-structured interviews with government officials (4), residents living near the Citarum (4), environmental experts (3) and activists (3). The interviews took 40–130 min involving five main and follow-up questions to probe further. The interviews were aimed at generating information on meanings of water quality, responsibility and involvement. As such, we asked questions that revolved around (1) the participants’ understandings of water quality (or cleanliness), responsibility and involvement; (2) what informs such understandings; and (3) how they articulate such understandings into their contexts (i.e. regulations, plans, talks, discussions and everyday practices). The interviews provided some valuable complementary insights on contested meanings and what causes participants to emphasise particular meanings over others (Hussein Citation2018). In delving deeper into practices, we combined interviewing with visual elicitation to further allow the participants to reflect and elaborate on specific meanings and their associated practices. The resulting reflections helped participants and researchers to gain in-depth insights into the information and analysis of everyday practices that might appear mundane and taken for granted (Rose Citation2014).

We involved interviewees from different parts of the river (i.e. upstream and downstream) because practices often vary between areas. We identified participants through media reportage and government archives. The participants were selected based on (1) their connectedness with the river, such as daily water uses; or (2) their engagement with the program, for instance, in formulating, executing, protesting, or evaluating the program. We used thick description (Geiger Citation2009; Ponterotto Citation2006) to analyse and interpret the data through multiple iterations to elucidate (1) competing meanings of water quality, responsibility and involvement, and (2) how these competing meanings inform restoration interventions (Mehta Citation2007). In order to ensure trustworthiness, we relied on member-checking methods (Birt et al. Citation2016).

Our work on the Citarum represents a critical case of river restoration (see Flyvbjerg Citation2006), meaning that it provides possibilities of strategic importance to address contemporary water governance problems, such as making policies more inclusive and knowledge-driven. By considering the role of multiple knowledges, we deliver insights into how such heterogeneity shapes river governance and restoration. The underlying normative assumption is that resulting insights are essential to understand how different meanings and practices are contested and articulated within river restoration. Such an understanding can foster more comprehensive approaches to river-related problems (Allouche, Middleton, and Gyawali Citation2015; Sneddon, Magilligan, and Fox Citation2017). This in-depth research on river restoration in the Indonesian context – with its own administrative, political and cultural characteristics – is also expected to render some valuable takeaways for other countries facing river pollution.

4. Contesting meanings of water quality, responsibility and involvement in river restoration discourse

Contemporary debates on river restoration involve multiple forms of knowledge. To substantiate the restoration program, the government referred to official reports, such as those commissioned by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, to identify pollution sources and, therefore, overall water quality in the Citarum (MEF Citation2016). The report pinpointed multiple pollution sources and supported their findings with numerical data, for example, for industrial and domestic waste. Whilst the latter were most contested in river restoration debates, they featured prominently in policy statements, discussions, talks and practices.

The following subsections present our findings on how diverse ways of knowing and living by the river shaped restoration. Specifically, we discuss the relationships between meanings of water quality, responsibility and involvement.

4.1. Contested meanings of water quality

Multiple contested meanings of water quality and related restoration efforts shape the Citarum river restoration discourse. Four main meanings of ‘a clean river’ stand out, namely (1) drinking water, (2) for general use excluding drinking, (3) the absence of domestic sources pollutants and (4) free from industrial contaminants.

The first meaning was derived from the president’s statement in 2018 when he emphasised that the river restoration efforts should turn the Citarum into a source of potable water:

… The Citarum [river], which was once clean, is now the most polluted river. Together, we clean the Citarum…and hopefully, in the next seven years, it will be a source of drinking water. (Joko Widodo [@jokowi] Citation2018)

… based on our forecasting and considering current water quality in Citarum … in 2025, we set to achieve water quality that complies with the state of low-polluted water. (CT Citation2019, 10)

The excerpt above shows the target changed into ‘achieving low-polluted water’, which equally means water quality for general use except drinking. This reveals that the interpretation of water quality differed among the governmental actors based on the adopted forms and sources of knowing, such as environmental analysis and related standards. We see here that knowledge is situated, and that its credibility and validity depend on how it is produced, circulated and sustained (Haraway Citation1988; see also Petts and Brooks Citation2006; Movik and Stokke Citation2015).

The governments relied on their own interpretation of scientific knowledge to shape and sustain particular meanings of water quality, while downplaying others. For example, the official statements (Ayo Bandung, Citation2019; Jurnal Jabar Citation2019) and studies by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MEF Citation2016) and the Citarum taskforce (CT Citation2019) singled out domestic waste, amongst other forms of waste, as the primary source of pollution by testing for coliform. Through the focus on coliform measurements, the government enacted a particular interpretation of water pollution as mainly caused by domestic waste. This resulted in a restoration agenda focused on educating people living along the Citarum to stop discharging their waste into the river and to adopt pro-environmental actions. This instance is suggestive of the performative character of knowledge, in particular, in pointing out how meanings and practices of water quality enable the government to intervene in ways that, for example, emphasise individuals’ role in reducing waste and water pollution (Hajer and Versteeg Citation2005; see also Shove Citation2010). This example further implies the tendency to normalise a certain articulation of river restoration at the expense of others (see Turnhout Citation2018). The resulting intervention thus emphasises that communities living by the Citarum have to embrace environmentally-friendly actions, which is somewhat in contrast to how the following activists and citizens attributed another set of meanings to restoration efforts by tackling industrial contamination.

… we also have a few phthalates that exceed the limits set up by the European Union quality standard. There is nonylphenol… that is above the environmental standard in force in Europe…. (DW Documentary, January 25, Citation2020)

Our example shows that scientific knowledge informed different meanings of water quality through multiple focal points from which types of measurements, methods and analyses were selectively deployed. This calls attention to the intentional selection of facts that underpin specific scientific arguments or decisions (Lövbrand Citation2011; Miller Citation2007; Roth et al. Citation2004; Turnhout, Dewulf, and Hulme Citation2016). Our case pinpoints a clear contrast between the government’s agenda to combat river pollution from domestic sources and the environmental activists’ initiatives geared towards industrial contaminants. As for the latter group, on 1 June Citation2016, GreenpeaceFootnote1 stated in its website that science provided a foundation to defend their claims on industrial pollutants and ultimately win a lawsuit against major factories (Greenpeace Citation2016). Adding to the activists’ claims, people living along the river also indicated the presence of industrial contamination.

Taking water from a well, Nur checked the colour of its water. The water smells horrible; one day, water would be red; the other days, it would be black, she said. (DW Documentary, January 25, Citation2020)

This vignette reveals the experiential knowledge of residents like NurFootnote2 and her neighbours. They understand water pollution by observing its colour and odour. The experience allows residents to identify industrial contamination and further shows how different ways of knowing enact specific meanings of water quality (see Rydin Citation2007; Movik and Stokke Citation2015). Hence, for Nur and others alike, a clean river means water free from industrial pollutants, a view not prioritised as part of the government restoration program(s) (see also Mehta et al. Citation2007).

This subsection on meanings of water quality shows that scientific and experiential forms of knowledge articulate competing meanings of water quality, thus leading to contestation over questions of responsibility and involvement. On the one hand, contestation appears here to frustrate the government’s restoration efforts. On the other, it arguably provides a productive space to expand the restoration repertoire by connecting the aforementioned meaning-making processes to concrete pro-environmental actions in the field.

4.2. Confined interpretations of responsibility?

The meaning-making processes discussed earlier implicate important questions about responsibility in river restoration. Two main approaches to the issue of responsibility concern contestation over knowledge claims and their translation into restoration measures. The first approach concerns the government’s orientation towards compliance with formally ascribed legal duties. The latter are enacted via legal procedures and regulations, whereby responsibility is defined by spatial proximity and attributed to localised actors (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007). The second approach to responsibility concerns the work of environmental activists and people living along the Citarum. Whilst their work includes reference to rules, it expands the understanding of restoration efforts beyond the confines of legal duties and extends the understanding of accountability into wider spatial and temporal dimensions transcending the present generation living in the Citarum river.

Regarding the former approach, the presidential regulation on the Citarum restoration required governmental bodies at all levels to take part in the program. For example, Article 12 of the regulation assigned duties to the Ministry of Environmental and Forestry to provide waste facilities (PI Citation2018). This example shows that for the government to take responsibility means that government bodies need to comply with duties defined in the regulation.

As for the residents, the regulation does not explicitly specify responsibilities. However, several articles stipulated that people adopt pro-environmental actions and appointed the taskforce, including the military, to educate people about acting in more environmental-friendly ways. Here, the military divided the river into 23 sectors led by a commander. Each commander adopted particular ways to translate restoration-related regulations into practice (CT Citation2019). For example, the military approached community leaders in their sector to mobilise residents to clean the river and to convene information meetings about the program and required actions. During a military-led information meeting, a village leader expressed that:

If the residents who litter rubbish into the river are identified, [they] can be chased [the direct object was unspecified]. It is the role of the residents to keep the Citarum clean…. (Pikiran Rakyat, March 17, Citation2021)

It is impossible for the government to restore the river without a collective effort from all stakeholders in keeping it clean. (Official NET News, 18 January Citation2018)

This idea of shared responsibility echoes Snel et al. (Citation2021) account, which suggests that collaboration between the authority and residents could solve issues of government incapacity and lack of public funding (Snel et al. Citation2021). However, in our case, what might appear as shared responsibility tends to resemble duty dumping (see Buchanan and Decamp Citation2006).

‘Duty dumping’ occurs when the government holds people responsible for managing household waste, while not specifying which government bodies are responsible for solving issues of waste flowing along the river. The local government in the downstream area argued that waste on their part of the river belongs to regions upstream; hence, those living in the latter regions should be held responsible. Ambiguity and multiple interpretations and articulations of duty-based responsibility show that ‘duty’ itself is socially constructed (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007), an insight prompting an alternative view of responsibility.

Different from the notion of responsibility as compliance with duty, the alternative view refers to broader spatial and temporal dimensions. The view is derived from international reports investigating the connections between factories along the Citarum and worldwide textile supply chains of international fashion brands (see DW Documentary, January 25, 2020; Unreported World, November 15, Citation2017). The investigation found that some well-known global brands subcontracted textile factories along the Citarum River. Akin to this investigation, other reportages attempted to unravel local-global connections in the fashion industry and pushed inquiries towards the brands whose subcontractors allegedly discharged untreated wastewater (e.g., Sanghani Citation2018).

These findings add yet another dimension to the question of responsibility by linking river pollution with the global supply chains of fashion brands. By not pinpointing industries as culpable, we note that the government’s restoration program eludes traces of the global fashion industry network and its liability towards the Citarum pollution as these global corporations were not enlisted explicitly in the restoration-related regulations. This invokes responsibility towards the ‘distant people’, a notion that refers to people in other places and their relationship with future generations.

Sunardi, a biologist, expressed his concern about the effects of harmful substances found in water samples in children.

People who drink contaminated water are at risk of cancer, inhibiting mental and physical growth primarily in children…. Therefore, they have to be saved from consuming such water…. (Unreported World, November 15, Citation2017; Sanghani Citation2018; Wallen n.d.)

The excerpt offers insights on future-oriented responsibility towards unborn generations (Massey Citation2006), which also aligns with Adam and Groves’ plea (Citation2011) to move outside the interpretation of ‘responsibility for the present’ by proposing a focus on the concept of ‘care’. This, they argue, brings ‘the future’ to the forefront of concerns towards responsibility. For our case, the orientation towards ‘the future’ broadens the understanding of responsibility; yet debates on responsibility in the restoration program were mainly dominated by narrower, legalistic understandings of responsibility that emphasise the role of individuals for whom the river is central in their everyday lives.

Summarizing, our investigation reveals two main approaches to responsibility, which proved instrumental for the ways restoration efforts were coordinated in practice. Contestations over the two approaches involved the government, activists and people living by the river. Despite a longstanding debate on those contrasting views of responsibility, the current restoration program still relies on the duty-based approach. Our findings suggest that ignoring diverse interpretations of responsibility in formulating and implementing restoration actions risks confining actors to a homogenous notion of accountability which may prove counterproductive to the Citarum restoration.

4.3. Towards inclusiveness?

In 2018, the central government invited a broad group of actors to participate in the Citarum Harum restoration program, such as government bodies from multiple levels and civic organisations. As stipulated in Article 18 (a) of the Citarum presidential regulation: “Civil society participates in preventing and restoring environmental pollution and degradation in the Citarum basin” (PI Citation2018). Here the civil society includes “individuals, community and non-secular organisations, philanthropists, entrepreneurs, academics and other groups of stakeholders” (Article 18 [b]).

The quotes from the Citarum presidential regulation imply that the government pursued a participatory approach and a more inclusive restoration program by considering what appeared to be an exhaustive list of stakeholders. However, despite an emphasis on inviting varying stakeholders, the regulations gave little attention to on-going citizen-based participation and involvement in restoring the river.

A major controversy emerged when a local activist indicated:

People in the Citarum have never been invited to plan and formulate restoration programs, as well as designate execution for the program. (Interview extract, 2 March 2021)

Attempting to be more inclusive, the government designed The Pentahelix Synergy Model. The model was meant to involve diverse stakeholders, such as government, private sectors, academia, local communities and media, in the restoration program. The list of stakeholders appeared to enable inclusiveness, and yet, at the same time, the list also constrained it. Only listed stakeholders were considered relevant to be part of the restoration program, for example, the model does not seem to do justice to underrepresented categories, such as homemakers and children (see Rancière Citation1996).

Moreover, the Pentahelix model implies that stakeholders were expected to accept and follow the government’s take on restoring the Citarum. That way, the model risks skewing participation to stakeholders whose stance complies with the government’s interests. Take the example of a blogger who wrote about the Citarum restoration program on an opinion platform:

I (am) involved in the Citarum restoration program through disseminating positive information…. to amplify what the Citarum (program) achieved and to counter negative information…. As stated by the head of the Citarum taskforce. (Extract from a blog, 27 November 2020)

Our example of the Pentahelix model and the blogger’s account implies that participation is exclusive in this case (Turnhout, Van Bommel, and Aarts Citation2010). Although stakeholders are invited and have the opportunity to exchange opinions, public participation is staged in a tokenistic fashion (Arnstein Citation1969), as the government decides it fits best. However, a lower participation level does not always imply a less authentic sense of involvement (Lawrence Citation2006).

While favouring participatory approaches (and quite at odds with the latter), the presidential regulation at the same time delegated tasks to the military, particularly for educating people. This triggered a sceptical response from local environmental activists, mainly as they thought the military acted beyond their tasks when requiring prior approval for conducting restoration-related activities, such as citizen-based pollution monitoring. In an interview, an activist claimed that:

Now, we [activists and people living by the Citarum] have to ask the military’s approval before we can perform restoration actions… This was unfortunate as we previously performed such efforts without seeking any of those [approval]. (Interview extract, 27 February 2021)

Despite all criticism and concerns, on September 29, Citation2019, Kompas in its website reported that the government continued to involve the military due to their seemingly effective role in educating people and executing river clean-up projects (Kompas Citation2019). These practices led the government to further endorse military involvement in (this type of) restoration. Colebatch (Citation2006) conceptualises similar attempts by the government to overtly steer involvement as authoritative instrumentality. In our case, such instrumentality appeared to impose the government’s views of other stakeholders and influence how others are supposed to behave or organise their involvement in accordance with restoration-related policies and regulations (Leach, Scoones, and Wynne Citation2005; Mosse Citation2003; see Anggoro Citation2020). This further extended the realm of authoritative instrumentality in the restoration program.

However, before the government implemented the Citarum Harum restoration program, multiple local activists participated in restoration efforts, for instance, by shutting down pipes from factories discharging untreated wastewater into the river (). These efforts were intended to issue warnings to polluting factories, without formal interference from the government (see Díaz-Reviriego, Turnhout, and Beck Citation2019). Such informal efforts facilitated broader involvement and coordinated responses to the insufficient impact of formal strategies to combat river pollution. In this context, Roy (Citation2009) explains informality as inscribed by formality.

Figure 2. Local activists blocked an illegal outlet that allegedly discharged untreated wastewater to the river by using stones and any materials found nearby. Source: Unreported World, 15 November Citation2017.

Pipe blocking became well-known throughout the Citarum as a tactical response to ineffective strategies for restoring the river (Interview with an activist, March 20, 2021; see also Make a Change, 15 November 2017). The ample coverage of these informal responses in the national and international media had led the government to recognise and formalise pipe blocking as restoration practice (see CT Citation2021). Notwithstanding this specific instance, our investigation revealed that the government often overlooked other informal restoration efforts, such as those of plastic scavengers, in reducing waste flowing in the river.

Informality can thus be either recognised or ignored based on how informality fits the governmental agenda (Roy Citation2005; Haid Citation2017). Our example shows that the government may selectively incorporate prominent informal practices to further justify the formal restoration program and promote the officials’ roles in combating pollution (see CEDS-FEBPU Citation2020). Subsequently, such an opportunistic approach risks ignoring other informal practices (e.g. scavenging plastics) and the possibilities of increasing the impact of restoration efforts.

This subsection shows that contestation over involvement in Citarum restoration sways between government-initiated participation and citizen-based involvement. On the one hand, the authorities performed the former via bureaucratic stewardship and relied on the Pentahelix model. Somewhat paradoxical to the intention of creating a more inclusive program, the government deployed the military, which the activists and residents criticised as disruptive to their restoration efforts, as well as to broader involvement. On the other hand, the key tenet of citizen-based involvement lies in the informal initiatives, which adds a variety of practices to formal restoration efforts. Although such informality has yet to be recognised in the program, the initiatives would entail a shift beyond the rather narrow and instrumentalist approach of the government restoration efforts.

5. Discussion

5.1. Problematising knowledge of water quality

At the outset, we questioned whether contestation over the Citarum’s restoration was indeed justified when considering the scientific knowledge brought to bear on tackling pollution. Our investigation showed that different meanings of water quality were skewed towards rather instrumental forms of river governance. For instance, we showed how the government and activists generated meanings of water quality based on categories, classifications, methods and measuring instruments that steered attention to particular groups as primarily responsible for polluting the river (Hajer and Versteeg Citation2005; Mehta Citation2007), highlighting particular meanings of water quality, assigning responsibility to some while ignoring others (Turnhout Citation2018).

In our case, the government mobilised a particular definition of water quality, which was amenable to interventions targeting domestic sources of pollution. By assessing water quality via coliform measurements in the river, the government associated responsibility with individual behavioural change towards pro-environmental actions. Meanwhile, other pieces of evidence were sidelined. Yet, they emerged and circulated through talks, routines and actions performed in the neighbourhoods near the Citarum; hence showing how stakeholders were able to mobilise multiple ‘knowledges’ of water quality (e.g. Rydin Citation2007; Sneddon, Magilligan, and Fox Citation2017). Residents and activists, for example, associated water quality with distinctive colours and odours. Additionally, they notably performed various tactics to combat pollution, such as the collective blocking of illegal wastewater outlets. These tactics circulated meanings of water quality held by residents and activists and helped amplify such meanings to become recognised and formalised into river restoration efforts. Such tactics align productively with Haraway’s (Citation1988) account of ‘situated knowledges’, as they are produced, circulated and sustained within specific groups and communities (Petts and Brooks Citation2006; see also Movik and Stokke Citation2015).

The selective use of knowledge refers here not only to the divide between scientific and local ways of knowing, but also to the marginalisation of different science-based representations. Such an approach, whether intentional or not, would only limit the space to recognise, discuss and continuously contest dominant meanings (Tsouvalis and Waterton Citation2012). We suggest, for the future, that restoration policies consider each form of knowledge as having its own credibility and validity criteria (Petts and Brooks Citation2006). More importantly, ongoing restoration efforts should be considered in terms of a discursive space, where those actors that are currently excluded from the formal restoration program are enabled to debate, learn and share different forms of knowledge as a basis for collective action (Klenk and Meehan Citation2015; Stepanova, Polk, and Saldert Citation2020; Nursey-Bray et al. Citation2014; Allouche, Middleton, and Gyawali Citation2015).

5.2. Expanding interpretations of responsibility

As a starting point for our study, we distinguished two notions of responsibility. First, we have the notion that concerns compliance with duty (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007), including debates on shared responsibility (Snel et al. Citation2021) and duty dumping (Buchanan and Decamp Citation2006). Second, we have a reading of responsibility that transcends spatial and temporal proximity (Massey Citation2004, Citation2006; Popke Citation2003).

The government understood responsibility rather narrowly in terms of aligning with institutional mandates (i.e. duties as they were inscribed in the regulations) (Gunder and Hillier Citation2007). This, in fact, mainly promoted measures towards combating pollution from domestic sources, whereby residents were chiefly held responsible for managing their waste. The concept of ‘shared responsibility’ was imposed accordingly, for instance, in educating the residents by means of military involvement. That way, the government promoted a normative view of responsibility through which regulations could be enforced and stabilised.

Duty-based approaches often assume spatial and temporal proximity by designating the locals as responsible. However, as Massey (Citation2004, Citation2006) and Popke (Citation2003) argue, responsibility is far more extensive. For the Citarum, we see textile subcontractors connected with the global supply chain of fashion industries with headquarters in different parts of the world. As such, the question of responsibility moves beyond spatial boundaries to consider pollution in the Citarum as the manifestation of a global phenomenon. However, the current approach to responsibility cannot tackle global polluters and hold these liable for transnational environmental problems in rivers (Evans, Welch, and Swaffield Citation2017; Vanderheiden Citation2011). In this context, activists and locals took the lead and contested the formal approach to responsibility. Activists investigated the connections of Citarum textile subcontractors with global brands to the boycott and even filed lawsuits against themFootnote3 (see also the work of Ramaswami et al. Citation2012).

Raising a global environmental perspective on the role and relationships between different structures (Shaw Citation1992), such as government, society and the global fashion industry, could expose and open up debates about pressing concerns, such as the environmental issues resulting from conspicuous fashion consumption (see Goodhart Citation2017). Meanwhile, debates on global responsibility should also draw attention to the risk of embracing particular views of responsibility while overlooking others (see Swyngedouw Citation2009). In a similar vein, the Citarum residents recognised that responsibility extends to future generations (Massey Citation2006), which highlighted a broader temporal understanding of responsibility, particularly when considering the physical and mental health of children exposed to chemical contaminants. Consequently, intergenerational involvement in river restoration distinguishes itself as particularly important. This can be achieved in various ways, for instance, via game-based approaches and role-play to develop alternative ideas for river restoration (see Sanchez et al. Citation2017; Wu and Lee Citation2015). As such, younger generations may contribute unexpected inputs to ongoing restoration efforts.

Although the global and future orientations of responsibility circulated through the media, discussions between activists, residents and those interested in the issue of river pollution and public health, they hardly contributed to shaping the restoration program. Hence, we suggest expanding the restoration agenda to include matters of global responsibility (e.g. address multinational industries) and future-oriented responsibility (e.g. intergenerational exchanges) as means to move beyond the dominance and confines of duty-based responsibility.

5.3. Beyond selective involvement

Government-initiated participation and citizen involvement were both parts of the Citarum river restoration; with the former following a strict bureaucratic approach of authoritative instrumentality from its planning to execution (Colebatch Citation2006). Following this line of reasoning, the government formulated the Pentahelix participation model, which allowed the government to steer involvement through selecting of relevant stakeholders and practices for the restoration program. Such an approach resembles tokenism (Arnstein Citation1969), whereby involvement is formally arranged in practice and bears little weight for actual river restoration.

Our analysis showed how informal ways of engaging in river restoration, such as citizen-led river monitoring, provided alternative forms of involvement. However, our findings also show that even such informal initiatives ultimately had to seek formal approval. By means of formalisation, authorities such as the military and the government reinforced their standing in the restoration program, which in turn, strengthened their position. Such attempts to formalise citizen-led initiatives, in fact, risk hampering local capacity towards those local restoration efforts.

Other than the specific initiatives to tackle river pollution, some locals contributed indirectly to restoration efforts through practices such as scavenging for plastics. Scavenging provided a livelihood opportunity, as well as a contribution to cleaning the river. Yet, only a few such informal practices actually captured the government’s attention. For instance, the government drew inspiration from citizen-led river monitoring, which led the government itself to issue warnings for polluting factories. However, the practice of scavenging for plastics was long overlooked in the formal approach to river restoration. Put differently, the government proved rather selective and opportunistic in terms of which practices count towards river restoration, which arguably only hampers progress in restoring the Citarum. Hence, the government might want to provide greater space for various informal initiatives and learn from those to shift towards more authentic forms of involvement in governing river restoration.

6. Conclusion

This research provides insights into the interplay of three main aspects: various meanings of water quality, related notions of responsibility and involvement in river restoration. Our research shows how discourse shapes meanings and practices and how knowledge is socially constructed, which subsequently affect the social and environmental conditions of people living by the Citarum. As pointed out throughout this paper, the government’s narrow interpretation of water quality played out at the expense of other important forms of scientific and experiential knowledge, as evoked through the various informal restoration initiatives. A shift beyond the government’s instrumental approach, which included a role for the military, towards more inclusive approaches, may create space to learn from different meanings and practices, hence strengthening the capacity to restore the Citarum river. On this note in particular, we acknowledge that this line of work could benefit from future research into the lives and practices of people living by the Citarum, to further our understanding of how everydayness is produced as part of both formal and informal restoration efforts. Finally, we suggest that it is time to create more opportunities for debate towards meaningful and, not least, transformative change in governing the Citarum’s restoration, which can also benefit in terms of lessons for more inclusive river restoration elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time and effort necessary to review the manuscript. We appreciate all valuable comments and suggestions. We are especially grateful to the research participants involved in the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The sources of this information include https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7522/this-court-victory-in-indonesia-could-send-shock-waves-across-the-fashion-world/, last accessed in October 2022; https://issuu.com/pawapeling/docs/laporan_melawan_limbah, last accessed in October 2022; https://www.greenpeace.org/seasia/id/press/releases/Puluhan-Tahun-Mencemari-3-Perusahaan-Tekstil-Digugat/, last accessed in September 2019. The last link was inaccessible in October 2022. However, similar information can be retrieved from: https://www.ejatlas.org/print/pt-kahatex-pt-insan-sandan-internusa-and-pt-five-star-textile, last accessed in October 2022.

2 Names in publicly available sources were cited as they were.

3 Information related to the lawsuits filed by the activists can be accessed at the similar links provided in the first note.

References

- Adam, Barbara, and Chris Groves. 2011. “Futures Tended: Care and Future-Oriented Responsibility.” Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 31 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1177/0270467610391237.

- Adams, William M., Martin R. Perrow, and Angus Carpenter. 2004. “Conservatives and Champions: River Managers and the River Restoration Discourse in the United Kingdom.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 36 (11): 1929–1942. doi:10.1068/a3637.

- Allouche, Jeremy, Carl Middleton, and Dipak Gyawali. 2015. “Technical Veil, Hidden Politics: Interrogating the Power Linkages behind the Nexus.” Water Alternatives 8 (1): 610–626.

- Anggoro, Bayu. 2020. “Public Participation for Citarum Harum Must Be Improved.” Media Indonesia, December 17. https://mediaindonesia.com/nusantara/278301/partisipasi-masyarakat-untuk-citarum-harum-harus-ditingkatkan.

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Arts, Bas, Jelle Behagel, Esther Turnhout, Jessica de Koning, and Séverine van Bommel. 2014. “A Practice Based Approach to Forest Governance.” Forest Policy and Economics 49: 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2014.04.001.

- Ayo Bandung. 2019. “LIPI: Limbah Rumah Tangga Bebani 70% Pencemaran Di Citarum [Indonesian Institute of Sciences: Domestic Waste Contributes 70% of Pollution in the Citarum River].” March 24. https://www.ayobandung.com/regional/pr-79647428/lipi-limbah-rumah-tangga-bebani-70-pencemaran-di-citarum.

- Assche, Kristof van, Martijn Duineveld, Raoul Beunen, and Petruta Teampau. 2011. “Delineating Locals: Transformations of Knowledge/Power and the Governance of the Danube Delta.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 13 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2011.559087.

- BI and GCS (Blacksmith Institute and Green Cross Switzerland). 2013. The Worlds Worst 2013: The Top Ten Toxic Threats Cleanup, Progress, and Ongoing Challenges. New York: Blacksmith Institute and Green Cross Switzerland. https://www.worstpolluted.org/docs/TopTenThreats2013.pdf.

- Birt, Linda, Suzanne Scott, Debbie Cavers, Christine Campbell, and Fiona Walter. 2016. “Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811. doi:10.1177/1049732316654870.

- Buchanan, Allen, and Matthew Decamp. 2006. “Responsibility for Global Health.” Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 27 (1): 95–114. doi:10.1007/s11017-005-5755-0.

- Buchanan, Karen S. 2013. “Contested Discourses, Knowledge, and Socio-Environmental Conflict in Ecuador.” Environmental Science and Policy 30: 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.12.012.

- Callon, M. 2007. “What Does It Mean to Say the Economics is Performative?” In Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, edited by D.A. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, and L. Siu, 311–357. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- CEDS-FEBPU (CEDS-Faculty of Economy and Business Padjadjaran University). 2020. “Survei Persepsi Masyarakat Terhadap Pembangunan Jawa Barat Di DAS Citarum [Survey for Citizens’ Perception of Development in the Citarum Watershed Area, West Java].” January 31.

- Chittoor Viswanathan, Vidhya, and Mario Schirmer. 2015. “Water Quality Deterioration as a Driver for River Restoration: A Review of Case Studies from Asia, Europe and North America.” Environmental Earth Sciences 74 (4): 3145–3158. doi:10.1007/s12665-015-4353-3.

- Choudhury, Runti, Anjana Mahanta, and Chandan Mahanta. 2018. “Water Quality in Assam: Challenges, Discontentment and Conflict.” In Water Conflicts in Northeast India, edited by K.J. Joy, Partha J. Das, Gorky Chakraborty, Chandan Mahanta, Suhas Paranjape, and Shruti Vispute, 37–49. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315168432-7.

- Colebatch, Hal K. 2006. “What Work Makes Policy?” Policy Sciences 39 (4): 309–321. doi:10.1007/s11077-006-9025-4.

- Colebatch, H. K. 2015. “Knowledge, Policy and the Work of Governing.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 17 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1080/13876988.2015.1036517.

- Cooke, Bill, and Uma Kothari. 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

- CT (Citarum Taskforce). 2019. “Rencana Aksi Pengendalian Pencemaran Dan Kerusakan Daerah Aliran Sungai Citarum Tahun 2019–2025 [Action Plan: Controlling Pollution and Environmental Deterioration in the Citarum Watershed Area].” June 19. https://citarumharum.jabarprov.go.id/renaksi/.

- CT (Citarum Taskforce). 2021. “Satgas Citarum Harum Tutup Saluran Limbah Hotel Di Bandung [Citarum Task Force Shutting down Polluting Outfall].” 3 March. https://youtu.be/atWtMS7qosA.

- Díaz-Reviriego, I., E. Turnhout, and S. Beck. 2019. “Participation and Inclusiveness in the Intergovernmental Science: Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” Nature Sustainability 2 (6): 457–464. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0290-6.

- DW Documentary. 2020. “The World’s Most Polluted River.” January 25. https://youtu.be/GEHOlmcJAEk.

- Edwards, Gareth A. S. 2013. “Shifting Constructions of Scarcity and the Neoliberalization of Australian Water Governance.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (8): 1873–1890. doi:10.1068/a45442.

- Evans, David, Daniel Welch, and Joanne Swaffield. 2017. “Constructing and Mobilizing ‘the Consumer’: Responsibility, Consumption and the Politics of Sustainability.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (6): 1396–1412. doi:10.1177/0308518X17694030.

- Ezbakhe, Fatine. 2018. “Addressing Water Pollution as a Means to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.” Journal of Water Pollution Dan Control 1 (6): 1–9.

- FAO and IWMI (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and International Water Management Institute). 2018. More People, More Food, Worse Water? A Global Review of Water Pollution from Agriculture. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

- Fischer, Frank. 2006. “Participatory Governance as Deliberative Empowerment: The Cultural Politics of Discursive Space.” American Review of Public Administration 36 (1): 19–40. doi:10.1177/0275074005282582.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research,” 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Geiger, Daniel. 2009. “Revisiting the Concept of Practice: Toward an Argumentative Understanding of Practicing.” Management Learning 40 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1177/1350507608101228.

- Goodhart, Michael. 2017. “Interpreting Responsibility Politically.” Journal of Political Philosophy 25 (2): 173–195. doi:10.1111/jopp.12114.

- Greenpeace. 2016. “This Court Victory in Indonesia Could Send Shock Waves across the Fashion World.” June 1. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/7522/this-court-victory-in-indonesia-could-send-shock-waves-across-the-fashion-world/.

- Gunder, Michael, and Jean Hillier. 2007. “Problematising Responsibility in Planning Theory and Practice: On Seeing the Middle of the String?” Progress in Planning 68 (2): 57–96. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2007.07.002.

- Haid, Christian G. 2017. “The Janus Face of Urban Governance: State, Informality and Ambiguity in Berlin.” Current Sociology 65 (2): 289–301. doi:10.1177/0011392116657299.

- Hajer, Maarten A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, Maarten A., and Wytske Versteeg. 2005. “A Decade of Discourse Analysis of Environmental Politics: Achievements, Challenges, Perspectives.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 7 (3): 175–184. doi:10.1080/15239080500339646.

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. “The Work of Representation.” In Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, 13–74. Milton Keynes: Sage and the Open University.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” In Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3178066. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Head, Brian W. 2007. “Community Engagement: Participation on Whose Terms?” Australian Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 441–454. doi:10.1080/10361140701513570.

- Hussein, Hussam. 2017. “Whose ‘Reality’? Discourses and Hydropolitics along the Yarmouk River.” Contemporary Levant 2 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1080/20581831.2017.1379493.

- Hussein, Hussam. 2018. “Lifting the Veil: Unpacking the Discourse of Water Scarcity in Jordan.” Environmental Science and Policy 89 (July): 385–392. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.09.007.

- Hussein, Hussam. 2019. “Yarmouk, Jordan, and Disi Basins: Examining the Impact of the Discourse of Water Scarcity in Jordan on Transboundary Water Governance.” Mediterranean Politics 24 (3): 269–289. doi:10.1080/13629395.2017.1418941.

- Ioris, Antonio A. R. 2008. “Water Institutional Reforms in Scotland: Contested Objectives and Hidden Disputes.” Water Alternatives 1 (2): 253–270.

- Joko Widodo [@jokowi]. 2018. “Air Sumber Kehidupan Dan Ekonomi Warga. Sungai Citarum Yang Dulu Jernih Kini Paling Tercemar [Water Is a Source of Life and People’s Economy. The Citarum, Which Was Once Clean, Is Now the Most Polluted River].” February 22. https://twitter.com/jokowi/status/966571627688247296.

- Jurnal Jabar. 2019. “Memprihatinkan 70 Persen Limbah Domestik Cemari Citarum [Seventy per Cent of Pollutants Come from Domestic Waste].” February 18. https://www.jurnaljabar.id/bewara/memprihatinkan-70-persen-limbah-domestik-cemari-citarum-b1Xbl9FC.

- Klenk, Nicole, and Katie Meehan. 2015. “Climate Change and Transdisciplinary Science: Problematizing the Integration Imperative.” Environmental Science and Policy 54: 160–167. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.05.017.

- Kompas. 2019. “Emil: Without the Military, Massive Change in Citarum Won’t Happen.” September 23. https://regional.kompas.com/read/2019/09/23/15002821/emil-no-tni-massive-change-in-citarum-won’t-happen?page=all.

- Kumparan. 2018. “Gonta-Ganti Jurus Pemerintah Untuk Citarum [Government’s Everchanging Strategy for the Citarum].” March 23. https://kumparan.com/kumparannews/gonta-ganti-jurus-pemerintah-untuk-citarum.

- Law, John. 2009. “Seeing Like a Survey.” Cultural Sociology 3 (2): 239–256. doi:10.1177/1749975509105533.

- Lawrence, Anna. 2006. “No Personal Motive?’ Volunteers, Biodiversity, and the False Dichotomies of Participation.” Ethics, Place and Environment 9 (3): 279–298. doi:10.1080/13668790600893319.

- Leach, M., I. Scoones, and B. Wynne. 2005. “Introduction: Science, Citizenship and Globalization.” In Science and Citizens: Globalization and the Challenges of Engagement, edited by M. Leach, I. Scoones, and B. Wynne, 3–14. London, New York: Zed Books.

- Lee, Seungho, and Gye-woon Choi. 2012. “Governance in a River Restoration Project in South Korea: The Case of Incheon.” Water Resources Management 26 (5): 1165–1182. doi:10.1007/s11269-011-9952-5.

- Lövbrand, Eva. 2011. “Co-Producing European Climate Science and Policy: A Cautionary Note on the Making of Useful Knowledge.” Science and Public Policy 38 (3): 225–236. doi:10.3152/030234211X12924093660516.

- Make a Change. 2017. “Kayaking down the World’s Most Polluted River, the Citarum River.” August 29. https://youtu.be/c8Hv15bV5lw.

- Massey, Doreen. 2004. “Geographies of Responsibility.” Geografiska Annaler 86 B 86 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00150.x.

- Massey, Doreen. 2006. “Space, Time, and Political Responsibility in the Midst of Global Inequality.” Erdkunde 60 (2): 89–95. doi:10.3112/erdkunde.2006.02.01.

- MEF (The Ministry of Environment and Forestry). 2016. Pollution Load of the Citarum River. Jakarta: The Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

- Mehta, Lyla. 2007. “Whose Scarcity? Whose Property? The Case of Water in Western India.” Land Use Policy 24 (4): 654–663. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2006.05.009.

- Mehta, Lyla, Amber Huff, and Jeremy Allouche. 2019. “The New Politics and Geographies of Scarcity.” Geoforum 101 (November 2018): 222–230. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.027.

- Mehta, Lyla, Stephen Marshall, Synne Movik, Andrew Stirling, Esha Shah, Adrian Smith, and John Thompson. 2007. “Liquid Dynamics: Challenges for Sustainability in Water and Sanitation,” 60. http://www.steps-centre.org/news/sanitation&hygieneweek08.html.

- Merdeka. 2013. “Aher Ingin Air Sungai Citarum Bisa Diminum Lima Tahun Lagi [Aher Wants Water from the Citarum River Potable in Five Years].” February 6. https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/aher-ingin-air-sungai-citarum-bisa-diminum-5-tahun-lagi.html.

- Metzger, Jonathan, Philip Allmendinger, and Stijn Oosterlynck. 2014. Planning against the Political: Democratic Deficits in European Territorial Governance. New York: Routledge.

- Miller, Clark A. 2007. “Democratization, International Knowledge Institutions, and Global Governance.” Governance 20 (2): 325–357. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00359.x.

- Mosse, David. 2001. “Inside Organizations.” In Inside Organization, edited by David N. Gellner and Eric Hirsch, 159–181. New York: Berg. doi:10.2307/3556628.

- Mosse, David. 2003. The Rule of Water: Statecraft, Ecology, and Collective Action in South India. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2005. On the Political. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2013. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. London: Verso.

- Movik, Synne, and Knut Bjørn Stokke. 2015. “Contested Knowledges, Contested Responsibilities: The EU Water Framework Directive and Salmon Farming in Norway.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 69 (4): 242–255. doi:10.1080/00291951.2015.1061049.

- Neumann, Roderick P. 2005. Making Political Ecology. London: Hodder Arnold.

- Nursey-Bray, Melissa J., Joanna Vince, Michael Scott, Marcus Haward, Kevin O’Toole, Tim Smith, Nick Harvey, and Beverley Clarke. 2014. “Science into Policy? Discourse, Coastal Management and Knowledge.” Environmental Science and Policy 38 (Icm): 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2013.10.010.

- Official NET News. 2018. “Citarum Riwayatmu Kini [Citarum Your Story Today].” January 16. https://youtu.be/IlTmQd7cH-M.

- Palmer, M. A., E. S. Bernhardt, J. D. Allan, P. S. Lake, G. Alexander, S. Brooks, J. Carr, et al. 2005. “Standards for Ecologically Successful River Restoration.” Journal of Applied Ecology 42 (2): 208–217. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01004.x.

- Perni, Ángel, José Martínez-Paz, and Federico Martínez-Carrasco. 2012. “Social Preferences and Economic Valuation for Water Quality and River Restoration: The Segura River, Spain.” Water and Environment Journal 26 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.2011.00286.x.

- Petts, Judith, and Catherine Brooks. 2006. “Expert Conceptualisations of the Role of Lay Knowledge in Environmental Decisionmaking: Challenges for Deliberative Democracy.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (6): 1045–1059. doi:10.1068/a37373.

- PI (President of the Republic of Indonesia). 2018. Presidential Regulation Number 15 Year 2018 on Acceleration in Controlling Pollution and Environmental Deterioration in the Citarum Watershed Area. Jakarta: President of the Republic of Indonesia.

- Pikiran Rakyat. 2021. “Satgas Citarum Harum Sektor 4 Majalaya Laksanakan Sosialisasi Penanganan DAS Citarum [The Role of the Military in Educating People Living near the Citarum].” March 17. https://galajabar.pikiran-rakyat.com/jabar/pr-1081624686/satgas-citarum-harum-sektor-4majalaya-kembali-melaksanakan-sosialisasi-penanganan-das-citarum.

- Ponterotto, Joseph G. 2006. “Brief Note on the Origins, Evolution, and Meaning of the Qualitative Research Concept Thick Description.” The Qualitative Report 11 (3): 538–549.

- Popke, E. Jeffrey. 2003. “Poststructuralist Ethics: Subjectivity, Responsibility and the Space of Community.” Progress in Human Geography 27 (3): 298–316. doi:10.1191/0309132503ph429oa.

- Ramaswami, Anu, Christopher Weible, Deborah Main, Tanya Heikkila, Saba Siddiki, Andrew Duvall, Andrew Pattison, and Meghan Bernard. 2012. “A Social-Ecological-Infrastructural Systems Framework for Interdisciplinary Study of Sustainable City Systems: An Integrative Curriculum across Seven Major Disciplines.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 16 (6): 801–813. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00566.x.

- Rancière, Jacques. 1996. “Post-Democracy, Politics and Philosophy.” Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities 1 (3): 171–178.

- Rose, Gillian. 2014. “On the Relation between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture.” The Sociological Review 62 (1): 24–46. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

- Roth, Wolff Michael, Janet Riecken, Lilian Pozzer-Ardenghi, Robin McMillan, Brenda Storr, Donna Tait, Gail Bradshaw, and Trudy Pauluth Penner. 2004. “Those Who Get Hurt Aren’t Always Being Heard: Scientist-Resident Interactions over Community Water.” Science Technology and Human Values 29 (2): 153–183. doi:10.1177/0162243903261949.

- Roy, Ananya. 2005. “Urban Informality: Toward and Epistemology of Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 71 (2): 147–158. doi:10.1080/01944360508976689.

- Roy, Ananya. 2009. “Strangely Familiar: Planning and the Worlds of Insurgence and Informality.” Planning Theory 8 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1177/1473095208099294.

- Rydin, Yvonne. 2007. “Re-examining the Role of Knowledge within Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 6 (1): 52–68. doi:10.1177/1473095207075161.

- Sanchez, Eric, Réjane Monod-Ansaldi, Caroline Vincent, and Sina Safadi-Katouzian. 2017. “A Praxeological Perspective for the Design and Implementation of a Digital Role-Play Game.” Education and Information Technologies 22 (6): 2805–2824. doi:10.1007/s10639-017-9624-z.

- Sanghani, Radhika. 2018. “Stacey Dooley Investigates: Are Your Clothes Wrecking the Planet?” BBC Three, October 9. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/5a1a43b5-cbae-4a42-8271-48f53b63bd07.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., and D. Yanow. 2012. Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes. New York: Routledge.

- Scott, Alister. 2011. “Focussing in on Focus Groups: Effective Participative Tools or Cheap Fixes for Land Use Policy?” Land Use Policy 28 (4): 684–694. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.12.004.

- Sharp, Liz, and Tim Richardson. 2001. “Reflections on Foucauldian Discourse Analysis in Planning and Environmental Policy Research.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 3 (3): 193–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jepp.88.

- Shaw, Martin. 1992. “Global Society and Global Responsibility: The Theoretical Historical and Political Limits of International Society.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 21 (3): 421–434. doi:10.1177/03058298920210031101.

- Shove, Elizabeth. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: Climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42 (6): 1273–1285. doi:10.1068/a42282.

- Sneddon, Chris, and Coleen Fox. 2006. “Rethinking Transboundary Waters: A Critical Hydropolitics of the Mekong Basin.” Political Geography 25 (2): 181–202. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.11.002.

- Sneddon, Chris S., Francis J. Magilligan, and Coleen A. Fox. 2017. “Science of the Dammed: Expertise and Knowledge Claims in Contested Dam Removals.” Water Alternatives 10 (3): 677–696.

- Snel, Karin A. W., Sally J. Priest, Thomas Hartmann, Patrick A. Witte, and Stan C. M. Geertman. 2021. “‘Do the Resilient Things.’ Residents’ Perspectives on Responsibilities for Flood Risk Adaptation in England.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 14 (3): 1–14. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12727.

- Speed, Robert A., Yuanyuan Li, David Tickner, Huojian Huang, J. Robert, Jianting Cao, Gang Lei, et al. 2016. “A Framework for Strategic River Restoration in China.” Water International 41 (7): 998–1015. doi:10.1080/02508060.2016.1247311.

- Stepanova, Olga, Merritt Polk, and Hannah Saldert. 2020. “Understanding Mechanisms of Conflict Resolution beyond Collaboration: An Interdisciplinary Typology of Knowledge Types and Their Integration in Practice.” Sustainability Science 15 (1): 263–279. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00690-z.

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2009. “The Antinomies of the Postpolitical City: In Search of a Democratic Politics of Environmental Production.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (3): 601–620. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00859.x.

- Tsouvalis, Judith, and Claire Waterton. 2012. “Building ‘Participation’ upon Critique: The Loweswater Care Project, Cumbria, UK.” Environmental Modelling and Software 36: 111–121. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.01.018.

- Turnhout, Esther. 2018. “The Politics of Environmental Knowledge.” Conservation and Society 16 (3): 363–371. doi:10.4103/cs.cs.

- Turnhout, E., S. Van Bommel, and N. Aarts. 2010. “How Participation Creates Citizens: Participatory Governance as Performative Practice.” Ecology and Society 15 (4): 15–21. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art26/.

- Turnhout, Esther, Art Dewulf, and Mike Hulme. 2016. “What Does Policy-Relevant Global Environmental Knowledge Do? The Cases of Climate and Biodiversity.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 18: 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.09.004.

- Turnhout, Esther, Tamara Metze, Carina Wyborn, Nicole Klenk, and Elena Louder. 2020. “The Politics of Co-Production: Participation, Power, and Transformation.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42 (2018): 15–21. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009.

- UN (United Nations). 2019. “Annex: Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Work of the Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 1–21. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global Indicator Framework after 2019 refinement_Eng.pdf%0Ahttps://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global Indicator Framework_A.RES.71.313 Annex.pdf.