Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are promoted as a global action plan for transformational change. Through calls to localise the global agenda, local governments have been made key actors in implementing the agenda. In Norway, the government ascribes municipalities a formal role in the national effort to implement the SDGs. Drawing on the concept of policy translation, we explore localisation processes at the strategic level of planning in Norwegian municipalities. Through analysis of municipal master plans and interviews with planners, we find that municipalities use a selective approach, prioritising goals that largely support existing policies, while more challenging goals become lost in translation. We argue that while the Norwegian planning system provides an institutional framework for implementing and following up on the SDGs, new rounds of translation will be needed to also handle difficult goals, if the SDGs are to create actual and much-needed policy change.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has been called “a notoriously difficult, slippery and elusive concept to pin down” (Williams and Millington Citation2004, 99). While “superficially simple,” it is also “capable of carrying a wide range of meanings and supporting sometimes divergent interpretations” (Adams Citation2001, 4). It can legitimate business as usual, while it also holds a “radical potential” for societal transformation (Brown Citation2016, 125). It has become a ubiquitous political concept, but to avoid that it becomes “everything and nothing” (Connelly Citation2007, 260), it must be translated into action. The 2030 Agenda, including 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets, is an attempt to make clear what sustainable development should be about in the 21st century (United Nations Citation2015). The 2030 Agenda was adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 after years of intergovernmental negotiations and dialogue with civil society, business, local governments, interest groups and others (Biermann et al. Citation2022). The SDGs are framed as universal and applicable to all countries, and should be achieved by 2030.

The 2030 Agenda takes as its point of departure that sustainable development must be approached holistically and that the three core dimensions, economic, social and environmental, are interlinked and indivisible. As such, its 17 SDGs and 169 targets should be addressed as a coherent whole (United Nations Citation2015). By stressing the integrated nature of the SDGs, Agenda 2030 encourages implementation that is not “siloed” (McGowan et al. Citation2019, 43). In this holistic view, implementation needs to take into account the interactions between different goals instead of focusing on individual goals and targets, as this “would imperil progress across multiple elements of the 2030 Agenda” (Messerli et al. Citation2019, xxi). However, while an integrated and indivisible framework is one of the underlying commitments of the 2030 Agenda (Long Citation2018), the agenda also acknowledges that countries, according to their own realities, capacities and development levels, may define their own priorities and focus on specific needs at national and sub-national levels to ensure consistent development pathways (Kulonen et al. Citation2019; United Nations Citation2015).

There is, in other words, a tension between the indivisibility of the SDGs on the one hand and the need to make room for national and local priorities on the other. This tension risks unbalanced attention being given to some goals and targets instead of others (Long Citation2018). A selective approach, moreover, opens up for cherry-picking, where only the goals that support existing priorities are selected, thus reducing the 2030 Agenda’s potential to leverage change (Fukuda-Parr Citation2016; Forestier and Kim Citation2020; Stafford-Smith et al. Citation2017, Gneiting and Mhlanga Citation2021). Through selective mobilisation of the goals, the SDGs might “add another layer of legitimacy to policies that were already identified as key for national development before the ratification of Agenda 2030” (Horn and Grugel Citation2018, 82).

These studies point to a risk of selectivity at the national level and in the private sector. However, implementation of the SDGs is increasingly happening at the local level, and there is a need to explore these tensions from a local perspective. What has come to be known as “SDG localisation” requires that the global goals “be translated into local contexts in ways that make them appear recognizable, urgent, and meaningful” (Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing Citation2022, 42). Selective engagement with the global goals is encouraged as part of this translation, as local governments are advised to make “choices and prioritize those goals and targets that best respond to their specific contexts and needs” (Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments Citation2016, 25). In a case study from England, Perry et al. (Citation2021) observe that local-level actors in principle acknowledged the SDGs as a holistic framework, but that the complexity of the framework, combined with a lack of national support and resources, increased the pressure to prioritise between the goals. There are, however, few studies that explore this selectivity in depth. The purpose of this paper is therefore to critically examine selectivity in municipal localisation processes.

In a literature review focused on subnational implementation, Ordóñez Llanos et al. (Citation2022) highlight that while much research is oriented towards how the SDGs could be implemented, there is a lack of studies providing examples of implementation in local contexts. While there is a growing body of literature on localisation (Krantz and Gustafsson Citation2021; Fox and Macleod Citation2021; Valencia et al. Citation2019; Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing Citation2022; Egelund Citation2022), there have been few attempts to critically assess how local governments are localising the SDGs and the consequences these distinct processes have for transformational change. We contribute to addressing this gap through an empirical examination of how the SDGs are localised in Norwegian municipalities, with a focus on what happens when local governments are relating the global goals to different contexts.

Norway presents an interesting case for investigating localisation processes, as the Norwegian government has ascribed a formal role to the country’s 356 municipalities in achieving the 2030 Agenda. According to national planning guidelines, the SDGs should be incorporated into social and land-use planning (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation Citation2019). Following this, municipalities have largely been localising the SDGs in strategic planning (Lundberg et al. Citation2020). Our contribution therefore also lies in examining the possibilities and challenges when SDG localisation is framed as an issue for planning. We ask the following research questions: 1) How are the SDGs localised in strategic municipal planning in Norway? 2) What are the benefits and limits of localising the SDGs in strategic planning?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we present the analytical approach, centred on policy translation in strategic municipal planning. In Section 3, we describe the methods used. Through document analysis and interviews, we provide both an overview of the output of SDG localisation processes among Norwegian municipalities and an in-depth understanding of localisation processes in four municipalities. In Section 4, we present the results. In Section 5, we discuss localisation through the lens of policy translation, and in Section 6 we conclude by suggesting where more research is needed.

2. Translating the SDGs in strategic municipal planning

While the universality of the 2030 Agenda might risk that the framework is not experienced as relevant at the local level, it might also inspire action, as it forces “the users to interpret the concept/goals according to their ambitions and understanding” (Gustafsson and Ivner Citation2018, 305). To explore localisation of the SDGs in strategic municipal planning, we draw on the concept of policy translation (Stone Citation2012). Policy translation emphasises the need for making adjustments to global policy frameworks, keeping in mind that policymaking is “intensely and fundamentally local, grounded and territorial” (McCann and Ward Citation2011, xiv). Mukhtarov (Citation2014, 6) defines policy translation as “the process of modification of policy ideas and creation of new meanings and designs in the process of cross-jurisdictional travel of policy ideas.” Through its emphasis on the creation of new meanings, the translation perspective is an interpretive approach to policy analysis, seeking to explore how actors make arriving policies “meaningful and workable” (Kortelainen and Rytteri Citation2017, 361).

A policy such as the SDGs brings with it certain pre-defined problem definitions, which act as “discursive frames that focus attention to specific realms of possibility in which solutions might be sought or constructed” (Temenos and McCann Citation2012, 1393). At the same time, the policy should also “speak to a recognized problem” in environment (Tait and Jensen Citation2007, 124). The translation process involves creating linkages between these policy frames. It involves “selecting aspects of a concept (and thus rejecting, reframing, or modifying others) or adding new elements” (Gómez and Oinas Citation2022, 5). Policy translation is, moreover, an ongoing process (Kingfisher Citation2013), consisting of a “successive chain of translations” (Kortelainen and Rytteri Citation2017, 368). This means that what is meaningful and workable at one point might not be later, when other actors are drawn into the translation process. In this paper, this means that localisation of the SDGs in strategic municipal planning is seen as only the first translation, and that new rounds of translations are needed in other types of plans, which can involve modifications to the SDGs in new ways.

Healey (Citation2013, 152) notes that translation is a process where ideas are “drawn down, adapted and inserted intro struggles over discourse formation and institutionalisation in new contexts.” This points to the importance of the institutional context where the translation is happening, including the actors involved in the translation. In this paper, we explore localisation in the context of strategic municipal planning. Municipal planning in Norway is regulated by the Planning and Building Act (PBA). The PBA provides municipal planning with an institutional framework that aims to ensure sustainable development and coordination between the interest of different sectors and government levels, as well as predictability, public participation and openness (Planning and Building Act Citation2008). Through this inclusiveness, planning can add politics to policy, including the mobilisation of counterhegemonic ideas (Temenos and McCann Citation2012; McCann and Duffin Citation2023). As such, planning presents an opportunity to politicise what is often referred to as a de-politicised policy framework (Fisher and Fukuda-Parr Citation2019).

In addition to the PBA, municipal planning is also guided by planning guidelines and steering signals from national and regional authorities. National planning guidelines are revised every fourth year, and in 2019 they emphasised that county and municipal authorities should base their social and land-use planning on the SDGs (Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation Citation2019). At the local level, this has led municipalities to incorporate the SDGs in their strategic planning (Lundberg et al. Citation2020). Strategic planning can be seen as “a first step to systematically gather ‘information about the big picture and using it to establish a long-term direction and then translate that direction into specific goals, objectives, and actions’” (Poister and Streib 2005, cited in Krantz and Gustafsson Citation2021, 4). Strategic planning concerns overarching and comprehensive political clarifications and visions, and it aims to arrive at a normative consensus about which values should guide future development (Holsen Citation2017). According to Albrechts (Citation2004, 751), strategic planning is “selective and oriented to issues that really matter.” In other words, the aim is not to cover all possible challenges, but to prioritise what is most important for the local community (Ringholm and Hofstad Citation2018).

At the top of the municipal planning hierarchy in Norway, is the municipal master plan. The municipal master plan contains both a social and a land-use element. In this paper we focus on the social element, a key strategic plan in the Norwegian planning system (Aarsæther and Hofstad Citation2018). According to the PBA, this plan “shall determine long-term challenges, goals and strategies for the municipal community as a whole and the municipality as an organisation” (Planning and Building Act Citation2008, § 11–2). The plan should, in principle, form the basis for other municipal plans and strategies, including budgets and legally binding land-use plans. However, while the strategic plan should be a tool for strategic and political steering, in practice, it has been criticised for being too overarching and consensus-oriented, lacking clear priorities and being difficult to translate into concrete policies at later stages (Kleven Citation2012; Ringholm and Hofstad Citation2018; Bang-Andersen, Plathe, and Hernes Citation2019; Plathe, Hernes, and Dahle Citation2022).

3. Methods

Since 2019, we have been involved in different research projects with the aim of both understanding and contributing to the localisation processes of the SDGs at the local and regional levels in Norway. In 2020, we conducted a study on behalf of the Ministry for Local Government and Modernisation to document how municipalities were working with the SDGs in their planning and the challenges involved (Lundberg et al. Citation2020). One finding indicated that municipalities that were quite different in terms of size, location, population and local challenges selected similar SDGs. As the finding was based on survey responses from municipalities early in the implementation stage, we were curious to know whether we would find the same tendency if we looked at adopted plans.

In this paper, we combine methods to provide both an overview and an in-depth understanding through a case study of four municipalities. To gain an overview of goal selection at the strategic level, we went through all municipal master plans adopted from 2019 to 2021 (from now on called strategic plans). We began by searching the websites of all 356 Norwegian municipalities and found that 116 plans had been adopted during this period. Using the SDGs as a keyword, we found 89 plans that included a reference to the SDGs, and a closer examination of these plans revealed that 57 contained a selection of SDGs, suggesting that close to half of the municipalities had made some choices about which SDGs they found most relevant. With the aim of better understanding which goals were selected and why, we chose to include only the 57 plans in our study. Plans that contained all the SDGs, or did not address them, were excluded.

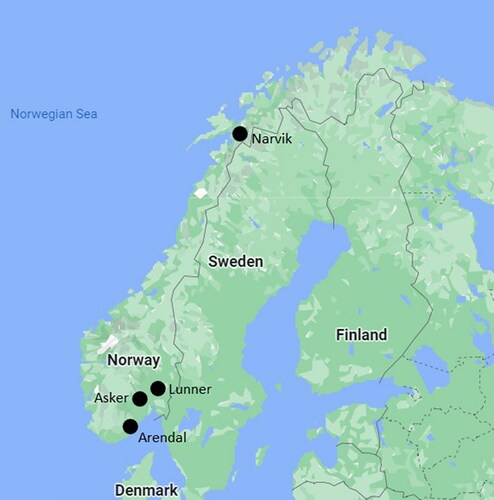

With this overview as a backdrop, we decided to do a case study of four municipalities that had all made selections of SDGs as part of their localisation processes. The four municipalities were part of the original study in 2020, and were included based on the following criteria: different size, population and location (see map in ), urban and rural municipalities and municipalities with experience from recent municipal merging processes. The municipalities were Asker (96,000 inhabitants), Arendal (45,000 inhabitants), Lunner (9,000 inhabitants) and Narvik (22,000 inhabitants). They had all worked on relating the SDGs to local planning for some years, and two had been identified as “first movers” of SDG implementation in a Nordic context (Sánchez Gassen, Penje, and Slätmo Citation2018). Through interviews with planners and analyses of official planning documents, we explored the selective approach in more depth.

The documents we analysed included the planning programme for the social element of the municipal master plan (draft and adopted plan), the social element of the municipal master plan (draft and adopted plan), supplements to the plans with details on the methods and processes of goal selection, as well as 239 written statements to these plans received during public consultations. In addition, we analysed previously adopted master plans in the four municipalities. In total, this amounted to 260 documents. We used sustainable development, sustainability, UN and SDGs as keywords and focused the analysis on how the SDGs were related to the local context, the arguments for selecting certain goals and targets, the description of the localisation process and the participants. In the documents from the consultation phase, we examined what kind of public debate the SDGs created.

We interviewed eight municipal officials in the four case municipalities, including planners and municipal managers. The interviews were conducted in Spring 2020 and again in Spring 2022. While the first round of interviews was part of the study from 2020, the new round of interviews allowed us to ask how the strategic plans had been followed up and how the interviewees evaluated the use of SDGs as a framework for planning in their municipalities. In the interviews, we explored how the SDGs were perceived and how the municipalities had worked to relate them to a local planning context, including how and why they had selected particular goals. We also focused on their experiences of these processes, what other municipalities could learn from them and how the SDGs were followed up in subsequent planning. The interviews were conducted digitally or by telephone, audio recorded and later transcribed. All quotes from interviews and documents have been translated from Norwegian by the authors.

Ethical approval was granted by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (https://www.nsd.no/en, reference number 887995), and all interviewees provided written consent to take part in the study. To ensure anonymity in line with the ethical approval, each interviewee is referred to with a number (1–8) in the text, without making a link to a specific municipality. This anonymisation does not distort the scholarly meaning.

4. Findings

4.1. Three goals to rule them all: goal selection and limited debate

Among the 356 Norwegian municipalities, we found that 114 of them had adopted municipal master plans between 2019 and 2021. Of these, 89 referenced the SDGs as an important policy framework for the development of the municipality. This indicates that most Norwegian municipalities had picked up the steering signal sent out by the government in national planning guidelines. In 57 plans, the municipalities had selected specific SDGs that would guide local development. The number of goals selected varied between 3 and 16, with an average of 10 goals per municipality.

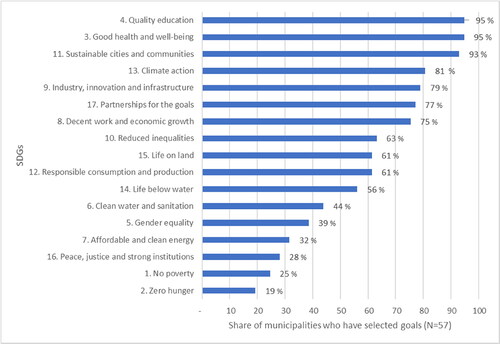

When it comes to which goals the municipalities selected, our review discerned a pattern. Three goals, related to health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4) and cities and communities (SDG 11), were selected by more than 90 percent of the municipalities. These three goals correspond well with the key policy areas of Norwegian municipalities, as required by law: provision of health services, primary schools and kindergartens, planning and development. Not far behind were goals related to climate action (SDG 13), industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), partnerships (SDG 17) and decent work and economic growth (SDG 8). These were selected by more than three-quarters of the municipalities. Among the less popular SDGs were goals related to energy (SDG 7), peace and justice (SDG 16), poverty (SDG 1) and hunger (SDG 2). An overview of SDG selection in Norwegian municipalities is presented in .

This overview does not say much about why these goals were selected or what kinds of policy problems they address in the local contexts. To gain a better understanding of the types of issues to which the SDGs were linked, we turned to four municipalities. The four case municipalities all selected the four goals at the top of the list in (SDGs 3, 4, 11 and 13). Two municipalities also included goals about peace and justice (SDG 16) and gender equality (SDG 5). None had selected the two goals related to poverty (SDG 1) and hunger (SDG 2) at the bottom of the hierarchy. Document analyses of the plans in the four municipalities showed similarities and differences in how the SDGs were employed in the municipality plans. Three municipalities had used the SDGs as overarching themes to structure their master plans, while one municipality had developed four overarching focus themes and then sorted the selected SDGs under these themes. All four municipal master plans covered visions, targets and strategies for their selected goals, and one municipality had specified what the goals meant for their citizens.

Two municipalities had chosen to complement the selected SDGs with local goals, while one municipality had included targets from a wider range of SDGs in its plan. When it comes to the local policy issues covered by the selected SDGs, the plans covered similar issues. All the municipalities had, for example, selected SDG 13 (climate action), and in the plans, this goal was linked with issues such as climate adaptation, reducing fossil fuels in transport and ensuring environmental demands in public procurements. SDG 11 (cities and communities) was linked with issues such as densification and reducing transport needs, access to public transport and civil protection. Another goal selected by all the municipalities, SDG 17 (partnerships), was linked to a need for the municipalities to work with the local community, including businesses and civil society. In several places, the SDGs were used to supplement other policies. For example, SDG 11 (cities and communities) was linked to national planning guidelines concerning land use and transport planning. The SDGs were also used to support existing policies in the municipalities. For example, as part of the effort to achieve SDG 13 (climate action), Narvik set out an intention to certify the municipal organisation according to an environmental standard, implementing a decision made by the municipal council a few years earlier.

When we compared the plans with previously adopted municipal master plans in these four municipalities, we found the old and new plans to be similar in terms of overarching strategies and policy issues. Rather than bringing in new issues, then, the newer plans included more processual aspects, such as the need to cooperate across sectors both within and outside the municipal organisation, with a reference to SDG 17 (partnerships). The document analysis, in other words, showed that the SDGs aligned well with established municipal priorities and, to a small extent, seemed to challenge these. The municipalities, when making their plans, made the SDGs fit their planning needs by combining elements from the SDG framework with local priorities, attaching the goals to existing policies. The fact that the SDGs can easily be linked with local issues and priorities might explain their appeal and quick uptake in the municipal sector.

In the public consultation phase, the selection of SDGs did not seem to generate any particular debate. Of the 239 comments the four municipalities received during the planning process, 61 addressed the SDGs in one way or another. Most of these comments welcomed the municipalities’ approaches to incorporate the SDGs in their plans. Around 20 comments were more critical about the chosen goals, and some suggested different goals, using the SDGs to support their arguments. Most of the critical comments concerned the omission of environmental SDGs. A few comments concerned the practice of selecting specific goals versus having a broader perspective that included all goals.

While the SDGs did not seem to generate much debate in the consultation phase, using the SDGs in the planning processes in the four municipalities did, however, involve broad participation – although not necessarily with the intent of selecting SDGs.

4.2. Selection criteria: local impact and room for manoeuvre

As shown, the planning documents provided little insight into why the four municipalities had selected particular goals over others. In a methodology booklet published by Asker municipality in 2018, local impact and room for manoeuvre were pointed to as important selection criteria. The 17 SDGs, it was emphasised, “constitute a whole, but a developing municipality needs to prioritise” (Asker Municipality Citation2018, 10). Goals were therefore chosen where the municipality could have the most impact. This statement was echoed in Narvik’s planning proposal:

The SDGs form a whole, but a developing municipality has to prioritise. Narvik municipality has therefore selected eight SDGs on which the greatest emphasis will be placed. This does not mean that the municipality will not work with the other sustainability goals but that it is these eight priority goals that are particularly emphasised in the municipality’s plans. (Narvik Municipality Citation2021, 14)

The localisation process had resulted in some variation between the four municipalities in terms of the selected SDGs. The planners described different processes with varying degrees of involvement from politicians, the municipal administration, local businesses, stakeholders and local residents. In Asker and Lunner, local politicians were central in selecting goals. In Arendal, the selection was made by a steering group comprising politicians, administrative staff and stakeholders, while in Narvik, the planning administration itself selected the SDGs. Through the interviews, it became clear that Asker municipality’s localisation process had been an important inspiration for the other municipalities. Asker had started working with the SDGs in 2016, inspired by the work of local authorities in other countries and influenced by a merger with two neighbouring municipalities, which created a need to reorganise their planning system. Having decided that they would use the SDGs as a framework for the new municipality, a political group with members from the three merging municipalities met several times over the course of a year. During that time, they developed a method for localising the SDGs with the help of a consultancy firm. The method involved assessing which SDGs were most important for the local community and on which goals the municipality could make the most impact. According to a report describing the localisation process in Asker, the members of the group “managed to put aside their own political positions while working with the SDGs as a framework” (Pure Consulting Citation2018, 9), suggesting a mostly technocratic framing of the process.

Inspired by Asker, one of the other municipalities used the same consultancy firm to help them prioritise SDGs when starting their localisation process, including the same method for localisation. Although recognising that the consultancies contributed knowledge and facilitation skills, the municipality soon decided to take control of the process: “At some point, we found out that we needed to do it ourselves because we had to get the goals anchored locally. Sometimes it might be a bit too easy to use consultants” (Interviewee 8, March 2020). The two other municipalities had also looked to Asker for inspiration, but in interviews, the planners stated that they did not have the same resources or staff to conduct a similar process, including an analysis of the local impact and importance of the goals.

Among the interviewees, few reflected on what was left out when some SDGs were selected and others were not. One exception was a planner, who noted that if they had repeated the process, they should have selected all the SDGs:

I think that if we had done it again, we would have included them all […] and not selected some. But the thing with selecting and weighing, perhaps it made the process of getting people to understand the content of the different goals easier. But I think I would choose to include them all. […] There’s a reason why there are 17 goals. The goals that are not selected need to be indirectly included somehow. (Interviewee 8, March 2020)

4.3. From goals to practice: a challenging translation

Across the interviews, the planners expressed high expectations regarding the SDGs’ potential contribution to a more holistic and cross-sectoral approach to societal development and sustainability in planning. At the same time, this enthusiasm was pending the next planning phase. Ringholm and Hofstad (Citation2018) point out that the most difficult part of strategic planning is to translate the visions of a strategic plan into concrete policies without losing the strategic “spirit.” Going from vision to policies proved challenging, according to our interviewees. Several interviewees stressed that since the municipal plans were at an overall strategic level, the SDGs had to be backed up by action in financial planning and municipal budgeting, thematic plans and land-use planning. Whereas the social element of the municipal plan only guides development, land-use plans are legally binding and thus depict the municipality’s spatial development.

Several interviewees emphasised that future decision-making would show if and to what extent local politicians would feel committed to following up the SDGs when having to prioritise between goals and interests. As was the case when they started working with the SDGs at the strategic level, there was no recipe for how to follow up a plan based on the SDGs:

It is not obvious how to go on to the next step. Because it is fine to do it on the highest level and insert the SDGs and then have some goals and strategies around that. But [it is another thing] going from there to linking this with the municipal organisation. (Interviewee 2, June 2022)

How far the municipalities had come in implementing the strategic plan in the municipal organisation varied. To ensure a “common thread” from the strategic plan to thematic plans, one of the municipalities had dedicated human resources – a “sustainability team” – to follow up the SDGs down the line. Another municipality had structured action plans and budgets around the goals of the strategic plan. The aim was to break down organisational silos and enable the elected officials to allocate resources based on the SDGs. In this way, the strategic plan could hopefully be used as a practical tool. Making this a useful tool would, however, take time, it was acknowledged. According to one interviewee, this way of thinking was anchored at the top level in the municipality, but it would take a while before the rest of the municipal organisation followed:

[First] they adjust their language, so we [the municipal managers] can be happy. And then it takes a few years and they follow the arrangement as planned. So it’s a process […] you cannot just introduce it like that. You need to take the system with you, and it takes some years before they understand what we mean. (Interviewee 8, June 2022)

Another challenge with following up the goals in the rest of the municipal planning system was that the politicians did not want to make too firm commitments in the strategic plan. They would rather have “round formulations that everyone can agree on” (Interviewee 8, June 2022). According to one interviewee, the politicians would rather take on political battles in other places, for example, when negotiating budgets. The problem with this approach is that it makes the strategic plan difficult to operationalise. This reflects the consensual character of strategic planning. While this might be politically convenient, from the point of view of the administration, it was more problematic:

If you think about the municipal master plan as a tool for steering, it is […] very easy to make things fit there, because it is so general. So we could have wanted […] that some of the disagreements were handled in that plan. (Interviewee 8, June 2022)

On a more general theme, when asked whether the introduction of the SDGs in the strategic plan had led to any visible changes in political priorities in the municipalities, the interviewees expressed cautious optimism. However, it was noted that it could be difficult to pinpoint the origin of different measures and policies exactly, including what came from the SDGs, and what would be done, regardless of having these goals as a framework. There was something about the present time and many things pulling in the same direction. As one interviewee expressed, “the SDGs hit us and we are very prepared to think along these lanes” (Interviewee 2, June 2022).

5. Discussion

Returning to our first research question, our findings show that during localisation, goals were associated with local problems and modified to make a better local fit, while those goals that did not resonate with local challenges were omitted from the plans. We identified a pattern to this goal selection among the municipalities, with SDGs related to health, education and cities and communities at the top of the prioritisation list. Goals related to poverty and hunger were scarcely selected. Given that the most frequently selected goals are part of key municipal service areas, our findings indicate path dependency rather than a changing course due to the SDGs (Kortelainen and Rytteri Citation2017). Meanwhile, Norway has major challenges related to several of the SDGs (Sachs et al. Citation2022). Loss of biodiversity and consumption are areas where Norway is performing poorly (Ministries of Local Government and Modernisation and of Foreign Affairs Citation2021). The goals related to these issues were, however, only moderately popular. There is, in other words, a gap between some of the “burning issues” and the selection of SDGs in Norwegian municipalities.

In making the SDGs “speak” to local problems (Tait and Jensen Citation2007), goals were filled with local content and merged with old policies. Rather than introducing new policy issues in municipal policymaking, our study suggest that the SDGs were aligned with existing priorities (Horn and Grugel Citation2018; Perry et al. Citation2021). This confirms the observation that local policymaking, while connecting with global agendas, first and foremost is a territorial and grounded activity (McCann and Ward Citation2011). Localisation, however, risks making the SDGs a near-sighted policy, missing the wider spatial and temporal dimensions of the 2030 Agenda. As Biermann et al. (Citation2022) observe, so far there is limited evidence of the SDGs making an impact beyond a change of rhetoric. With much attention given to localisation both in guidelines and policy studies (e.g. Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments Citation2016; Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing Citation2022), our findings suggest that localisation is no panacea. The risk is that localisation simply leads to “the relabelling of existing priorities and programmes without changing their substance, targets, or timelines” (Gneiting and Mhlanga Citation2021, 922).

Our interviewees were all aware of this dilemma, and some warned against the SDGs simply becoming a new way of repackaging existing policies. From a practical point of view, a selective approach to the 2030 Agenda can be understood as a way to limit the scope of a plan and make it more targeted. There are, in other words, good reasons why municipalities make certain selections with limited resources and capacity. As we have shown, selectivity is associated with assessments of importance, local challenges and potential influence at the local level. Moreover, when trying to create public awareness and local ownership of the SDGs, it is probably easier to reduce the complexity by focusing on local challenges related to only some of the goals rather than the whole menu (Perry et al. Citation2021). A selective approach is also a reasonable approach in light of the critique that strategic municipal plans are often too broad and lack political priorities (Ringholm and Hofstad Citation2018). The challenge will, however, be to follow up this first round of SDG translations at later stages, with other actors, discussions and interests (Kortelainen and Rytteri Citation2017).

This brings us to our second research question. We show that when the SDGs become localised in Norwegian strategic municipal planning, they become a part of a system where they should be further operationalised and followed up through formal processes such as reporting, budgeting and binding land-use plans. In principle, then, there is a system for following through from visionary statements at the global level to concrete local action, accompanied by procedural rules in the Planning and Building Act. Strategic municipal planning in Norway is intended to be an important tool for local political steering and development (Plathe, Hernes, and Dahle Citation2022). Thus, localising the SDGs at the overall planning level should, in theory, make political priorities visible and commit politicians to deliver on concrete action in subsequent plans. Making the SDGs a part of the planning system also contributes to broad anchoring of the goals through participatory processes, something emphasised by all our interviewees. This “convening power” in summoning different stakeholders to discussions around the same issues has been noted as a value of SDG localisation (Fox and Macleod Citation2021).

As we have shown, incorporating the SDGs in strategic municipal planning also has distinct constraints. New rounds of translations, from overarching ambitions in strategic plans into concrete and binding policies continues to be a challenge. At the same time, this is what will make the SDGs have an actual impact on policy (Ringholm and Hofstad Citation2018). While our findings point to efforts to ensure a “common thread” from the strategic plan to more operative plans, our material also points in the other direction – that introducing the SDGs as policy objectives complicates implementation of the strategic plan, since the goals remain vague. Although localisation processes have contributed to translating and relating the global goals to different local contexts, the municipalities’ selective approach suggests that more challenging translations have been left to later stages of planning.

The SDGs, as we see it, have potential to contribute to local discussions about long-term challenges and consequences of local planning practices in a broader perspective. However, this requires that also the difficult SDGs – typically the environmental goals and targets – are included in the discussion, and not ignored (Stafford-Smith et al. Citation2017). Our findings show that there was limited political and public debate concerning the selection of SDGs. Again, this seems to reflect a more general problem for strategic municipal planning in Norway. If the 2030 Agenda is to be taken seriously as a political project, which is also emphasised in national planning guidelines, then it is a paradox that localisation processes in Norway have generated so little debate to date.

6. Conclusion

In this paper we have explored localisation of the SDGs in strategic municipal planning in a Norwegian context. By focusing on the practice of selecting SDGs, our findings indicate that SDG localisation has largely supported existing priorities in the municipalities. In Norway and elsewhere, the 2030 Agenda is being referred to as an important policy framework for sustainable development (European Commission Citation2019; Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation Citation2019). Through calls to localise the SDGs, implementation of the goals is delegated to lower levels of government, where they become part of plans and strategies. Based on our findings, we will argue that there is little reason to believe that adding the SDGs to strategic municipal planning in itself contributes to a change in course. While localisation puts the fate of the SDGs in the hands of local decision-makers and might contribute to engagement around global issues, there is also reason to warn against the SDGs becoming just another box to tick in a municipal plan, rather than inspiring actual and much-needed policy changes. Nevertheless, we will argue that the planning system could be a useful framework for implementing the SDGs in a Norwegian context. The planning system offers a democratic and knowledge-based system for following up on overarching goals and ensuring action and evaluation of local efforts. It also has the capacity to make conflicting interests visible and engage productively with goal conflicts instead of steering towards consensus. Finally, it gives the public an opportunity to hold politicians accountable for their commitments. However, this requires that the goals that seem too difficult or challenging at first glance, do not become lost in translation.

As our study shows, Norwegian municipal master plans have largely incorporated the SDGs in one way or another. While we have focused on the municipal administration and the viewpoints of planners, future studies should critically examine to what extent commitments about the SDGs in strategic planning are followed up in the following rounds of policy translation. As our study suggests, strategic planning is largely oriented towards consensus, and this is therefore not where political differences and conflicts become visible. Future research could therefore explore how politicians, developers and stakeholders draw on the SDGs to argue, mobilise and justify different positions in controversial planning processes. Exploring how SDGs are used to legitimise conflicting positions at the local level could contribute to greater understanding of how goal conflicts are played out in specific planning processes and to what extent the SDGs can spur alternative policies that move beyond business as usual.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the interviewees who participated in this study. We also wish to thank everyone who took part in discussions and commented on earlier drafts of the paper, including Kjersti Granås Bardal, Tim Richardson, Maiken Bjørkan, Bjørn Vidar Vangelsten and three anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarsæther, Nils, and Hege Hofstad. 2018. “Samfunnsdelen – flaggskipet i pbl.-flåten?.” In Plan-og bygningsloven 2008 – fungerer loven etter intensjonene?, edited by Gro Sandkjær Hanssen and Nils Aarsæther, 157–172. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Adams, Bill. 2001. Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Albrechts, Louis. 2004. “Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31 (5): 743–758. doi:10.1068/b3065.

- Ansell, Christopher, Eva Sørensen, and Jacob Torfing. 2022. Co-Creation for Sustainability: The UN SDGs and the Power of Local Partnerships. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. doi:10.1108/9781800437982.

- Asker Municipality. 2018. The New Asker Municipality is Based on the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Asker: Asker kommune. https://www.asker.kommune.no/globalassets/samfunnsutvikling/fns-barekraftsmal/dokumenter/engelske-tekster/2018_08_15-rapport_nye_asker_fn_barekraftmal_engelsk-kortversjon.pdf.

- Bang-Andersen, Stig, Erik Plathe, and May Britt Hernes. 2019. Prioriterte mål i kommunalt og fylkeskommunalt planarbeid. Bergen: Asplan Viak. https://www.ks.no/contentassets/9b46a6940db54fae865da7dcd06fb7ec/rapport-fou-prosjekt-184011.pdf.

- Biermann, Frank, Thomas Hickmann, Carole-Anne Sénit, Marianne Beisheim, Steven Bernstein, Pamela Chasek, Leonie Grob, et al. 2022. “Scientific Evidence on the Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 5 (9): 795–800. doi:10.1038/s41893-022-00909-5.

- Brown, Trent. 2016. “Sustainability as Empty Signifier: Its Rise, Fall, and Radical Potential.” Antipode 48 (1): 115–133. doi:10.1111/anti.12164.

- Connelly, Steve. 2007. “Mapping Sustainable Development as a Contested Concept.” Local Environment 12 (3): 259–278. doi:10.1080/13549830601183289.

- Egelund, Jannik. 2022. “FN’s Verdensmål i danske kommuner: Et casestudie af tre danske kommuners oversættelse og samskabelse af verdensmålene.” PhD diss., Roskilde University.

- European Commission. 2019. Reflection Paper: Towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030. Brussels: European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-02/rp_sustainable_europe_30-01_en_web.pdf

- Fisher, Angelina, and Sakiko Fukuda-Parr. 2019. “Introduction: Data, Knowledge, Politics and Localizing the SDGs.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 20 (4): 375–385. doi:10.1080/19452829.2019.1669144.

- Forestier, Oana, and Rakhyun E. Kim. 2020. “Cherry-Picking the Sustainable Development Goals: Goal Prioritization by National Governments and Implications for Global Governance.” Sustainable Development 28 (5): 1269–1278. doi:10.1002/sd.2082.

- Fox, Sean, and Allan Macleod. 2021. “Localizing the SDGs in Cities: Reflections From an Action Research Project in Bristol, UK.” Urban Geography. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/02723638.2021.1953286.

- Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko. 2016. “From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Shifts in Purpose, Concept, and Politics of Global Goal Setting for Development.” Gender & Development 24 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1080/13552074.2016.1145895.

- Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments. 2016. Roadmap for Localizing the SDGs: Implementation and Monitoring at Subnational Level. Nairobi: UN Habitat. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/commitments/818_11195_commitment_ROADMAP%20LOCALIZING%20SDGS.pdf.

- Gneiting, Uwe, and Ruth Mhlanga. 2021. “The Partner Myth: Analysing the Limitations of Private Sector Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals.” Development in Practice 31 (7): 920–926. doi:10.1080/09614524.2021.1938512.

- Gómez, Lucía, and Päivi Oinas. 2022. “Traveling Planning Concepts Revisited: How They Land and Why It Matters.” Urban Geography. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/02723638.2022.2127267.

- Gustafsson, Sara, and Jenny Ivner. 2018. “Implementing the Global Sustainable Goals (SDGs) into Municipal Strategies Applying an Integrated Approach.” In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research, edited by Walter Leal Filho, 301–316. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Healey, Patsy. 2013. “Circuits of Knowledge and Techniques: The Transnational Flow of Planning Ideas and Practices.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (5): 1510–1526. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12044.

- Holsen, Terje. 2017. “Samfunnsplanlegging, arealplanlegging og plangjennomføring.” Kart og Plan 77 (3): 237–249.

- Horn, Philipp, and Jean Grugel. 2018. “The SDGs in Middle-Income Countries: Setting or Serving Domestic Development Agendas? Evidence from Ecuador.” World Development 109: 73–84. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.005.

- Kingfisher, Catherine. 2013. A Policy Travelogue: Tracing Welfare Reform in Aotearoa/New Zealand and Canada. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Kleven, Terje. 2012. “‘If Planning is Everything…’: Wildavsky Revisited.” Plan 44 (2): 48–53. doi:10.18261/ISSN1504-3045-2012-02-11.

- Kortelainen, Jarmo, and Teijo Rytteri. 2017. “EU Policy on the Move: Mobility and Domestic Translation of the European Union’s Renewable Energy Policy.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (4): 360–373. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2016.1223539.

- Krantz, Venus, and Sara Gustafsson. 2021. “Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals Through an Integrated Approach in Municipalities: Early Experiences from a Swedish Forerunner.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 64 (14): 2641–2660. doi:10.1080/09640568.2021.1877642.

- Kulonen, Aino, Carolina Adler, Christoph Bracher, Susanne Wymann, and von Dach. 2019. “Spatial Context Matters in Monitoring and Reporting on Sustainable Development Goals: Reflections Based on Research in Mountain Regions.” GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 28 (2): 90–94. doi:10.14512/gaia.28.2.5.

- Llanos, Andrea Ordóñez, Rob Raven, Magdalena Bexell, Brianna Botchwey, Basil Bornemann, Jecel Censoro, Marius Christen, et al. 2022. “Implementation at Multiple Levels.” In The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance through Global Goals?, edited by Frank Biermann, Thomas Hickmann and Carole-Anne Sénit, 59–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009082945.

- Long, Graham. 2018. “Underpinning Commitments of the Sustainable Development Goals: Indivisibility, Universality, Leaving No One Behind.” In Sustainable Development Goals, edited by Duncan French and Louis J. Kotzé, 91–116. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lundberg, Aase., Kristine, Kjersti, Granås Bardal, Bjørn Vidar Vangelsten, Mathias Brynildsen Reinar, Maiken Bjørkan, and Tim Richardson. 2020. Strekk i laget: en kartlegging av hvordan FNs bærekraftsmål implementeres i regional og kommunal planlegging. Bodø: Nordlandsforskning. https://nforsk.brage.unit.no/nforsk-xmlui/handle/11250/2723330

- McCann, Eugene, and Kevin Ward. 2011. “Urban Assemblages: Territories, Relations, PRactices, and Power.” In Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age, edited by Eugene McCann and Kevin Ward, xiv–xxxv. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McCann, Eugene, and Tony Duffin. 2023. “Mobilising a Counterhegemonic Idea: Empathy, Evidence, and Experience in the Campaign for a Supervised Drug Injecting Facility (SIF) in Dublin, Ireland.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 48 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1111/tran.12565.

- McGowan, Philip J. K., Gavin B. Stewart, Graham Long, and Matthew J. Grainger. 2019. “An Imperfect Vision of Indivisibility in the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 2 (1): 43–45. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0190-1.

- Messerli, Peter, Endah Murniningtyas, Parfait Eloundou-Enyegue, Ernest G. Foli, Eeva Furman, Amanda Glassman, Gonzalo Hernández Licona, Eun Mee Kim, Wolfgang Lutz, and J.-P. Moatti. 2019. Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now: Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/24797GSDR_report_2019.pdf.

- Ministries of Local Government and Modernisation and of Foreign Affairs. 2021. Voluntary National Review 2021 – Norway. Oslo: Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/cca592d5137845ff92874e9a78bdadea/en-gb/pdfs/voluntary-national-review-2021.pdf.

- Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. 2019. National Expectations Regarding Regional and Municipal Planning 2019–2023. Oslo: Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/cc2c53c65af24b8ea560c0156d885703/nasjonale-forventninger-2019-engelsk.pdf.

- Mukhtarov, Farhad. 2014. “Rethinking the Travel of Ideas: Policy Translation in the Water Sector.” Policy & Politics 42 (1): 71–88. doi:10.1332/030557312X655459.

- Narvik Municipality. 2021. Kommuneplanens samfunnsdel 2022–2040 (planforslag). Narvik: Narvik kommune. https://www.narvik.kommune.no/_f/p-1/i7bffbe9b-79c5-4450-a8cf-38a1d9708cdc/kommuneplanens-samfunnsdel-2022-2040_planforslag_06012022.pdf.

- Perry, Beth, Kristina Diprose, Nick Taylor Buck, and David Simon. 2021. “Localizing the SDGs in England: Challenges and Value Propositions for Local Government.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3: 746337. doi:10.3389/frsc.2021.746337.

- Planning and Building Act. 2008. “Act of 27 June 2008 No. 71 Relating to Planning and the Processing of Building Applications.” https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/planning-building-act/id570450/.

- Plathe, Erik, May Britt Hernes, and Kristin Karlbom Dahle. 2022. Ny agenda for kommuneplanens samfunnsdel. Kongsberg: Asplan Viak. https://www.ks.no/contentassets/60bfa3a0abf946c0927dfecbee78ddb0/KS-FoU-Kommuneplanens-samfunnsdel-som-lokalpolitisk-styringsverktoy-Sluttrapport.pdf.

- Pure Consulting. 2018. FNs bærekraftsmål som rammeverk for felles kommuneplan for nye Asker kommune. Oslo: Pure Consulting. https://www.asker.kommune.no/globalassets/nye-asker-kommune/kommuneplan/vedlegg/21-a_p1-rapport-fra-utvalg-barekraftsmal.pdf.

- Ringholm, Toril, and Hege Hofstad. 2018. “Strategisk vending i planleggingen?.” In Plan-og bygningsloven – en lov for vår tid?, edited by Gro Sandkjær Hanssen and Nils Aarsæther, 107–121. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Sachs, Jeffrey, Christian Kroll, Guillame Lafortune, Grayson Fuller, and Finn Woelm. 2022. Sustainable Development Report 2022. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009210058.

- Sánchez Gassen, Nora, Oskar Penje, and Elin Slätmo. 2018. Global Goals for Local Priorities: The 2030 Agenda at Local Level. Stockholm: Nordregio. http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1251563/FULLTEXT03.pdf.

- Stafford-Smith, Mark, David Griggs, Owen Gaffney, Farooq Ullah, Belinda Reyers, Norichika Kanie, Bjorn Stigson, Paul Shrivastava, Melissa Leach, and Deborah O'Connell. 2017. “Integration: The Key to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals.” Sustainability Science 12 (6): 911–919. doi:10.1007/s11625-016-0383-3.

- Stone, Diane. 2012. “Transfer and Translation of Policy.” Policy Studies 33 (6): 483–499. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.

- Tait, Malcolm, and Ole B. Jensen. 2007. “Travelling Ideas, Power and Place: The Cases of Urban Villages and Business Improvement Districts.” International Planning Studies 12 (2): 107–128. doi:10.1080/13563470701453778.

- Temenos, Cristina, and Eugene McCann. 2012. “The Local Politics of Policy Mobility: Learning, Persuasion, and the Production of a Municipal Sustainability Fix.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44 (6): 1389–1406. doi:10.1068/a44314.

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

- Valencia, Sandra C., David Simon, Sylvia Croese, Joakim Nordqvist, Michael Oloko, Tarun Sharma, Nick Taylor Buck, and Ileana Versace. 2019. “Adapting the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda to the City Level: Initial Reflections From a Comparative Research Project.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 11 (1): 4–23. doi:10.1080/19463138.2019.1573172.

- Williams, Colin C., and Andrew C. Millington. 2004. “The Diverse and Contested Meanings of Sustainable Development.” The Geographical Journal 170 (2): 99–104. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.00111.x.