Abstract

Volunteers are crucial for ecological research and nature conservation. However, despite calls in the volunteering literature to look beyond recruitment only and pay more attention to retaining and supporting volunteers, nature volunteers’ experiences have received little empirical attention. Using open survey questions among a diverse sample of formal and informal Dutch nature volunteers (N = 3775), we present a qualitative analysis of the factors that could cause nature volunteers to quit, and what keeps them going. Furthermore, we relate these to the three fundamental human needs for self-determination (autonomy, competence and relatedness). We find that reasons to quit nature volunteering include difficult situations (e.g. conflicts and tensions), volunteers’ personal circumstances, and insufficient support or appreciation. Respondents are motivated to continue because of pleasure in the activities and the people they meet, but also by a connection with nature, and the role of nature volunteering in living a meaningful and fulfilling life.

1. Introduction

As is true for many important challenges in the twenty-first century, the conservation of nature and biodiversity is highly dependent on volunteers. Volunteers play an important role in protecting and managing nature and greenspace, ecological research, and nature education (Bixler, Joseph, and Searles Citation2014; Dresner et al. Citation2015; McKinley et al. Citation2017). Concerns related to recruitment challenges and the demographic profile of current nature volunteers are voiced frequently (Hobbs and White Citation2012; Merenlender et al. Citation2016). This is not just true of the scientific literature; in the Netherlands the recent “Action Plan Green Volunteers” (“Actieplan Groene Vrijwilligers” 2018) highlights both the need for recruiting more volunteers, and for more diversity in their demographic profile.

However, volunteering scholars have cautioned that it is important to look beyond the question of how to recruit more volunteers, and pay much more attention to the experiences and support of current volunteers. Brudney and Meijs (Citation2009) argue that current practices in volunteer management place an overly strong emphasis on recruitment, to the detriment of committing resources to supporting and appreciating current volunteers. These authors propose an alternative model of volunteer management that takes volunteers’ current and future engagement and motivation as a starting point, rather than just the needs of the specific organisation to which a volunteer is currently committed. This is not just important to sustainably manage volunteer involvement in their current role and prevent volunteer burnout (Byron and Curtis Citation2001), but also to prevent volunteers from growing disillusioned with volunteering in the future, making it an important priority for all organisations working with volunteers (Brudney and Meijs Citation2013).

Such a perspective on volunteering emphasises the importance of maintaining volunteers’ motivation over the longer term, helping them deal with difficult situations such as conflicts with fellow volunteers or balancing volunteering with work and family life, and supporting them to avoid burnout and other reasons to quit. In other words, it invites an increased interest in understanding volunteering from the perspective of the volunteer. This involves research to help understand volunteers’ motivations, but also their experiences (West and Pateman Citation2016). Indeed, Bussell and Forbes (Citation2002, 250) argue that “in a dynamic changing environment, where the number of voluntary organisations is growing and the volunteer pool is diminishing, organisations must understand not only what motivates volunteers but also what keeps them”.

Paying specific attention to the experiences of volunteers also resonates with the notion of volunteering as a process; Snyder and Omoto’s (Citation2008) Volunteer Process Model emphasises not only the factors that initially drive and motivate volunteering (which they refer to as antecedents), but also the experiences of volunteers. These experiences include both the volunteers themselves as well as the social and organisational setting. The former includes, amongst others, volunteers’ freedom of choice, match with the organisation and satisfaction with their volunteer work, while the latter encompasses the way in which a volunteer organisation matches volunteers with tasks, and the degree to which volunteers bond and interact with fellow volunteers (Snyder and Omoto Citation2008). Within this broad theme of volunteer experiences, in this paper we investigate both nature volunteers’ reasons for staying, as well as the factors that drive them to quit. In addition, we specifically inquire into difficult situations that volunteers encounter, as these can play a role in the decision to stay or quit.

1.2. Experiences and self-determination

Despite this clear need for research into volunteers’ experiences, Wilson (Citation2012) found that the experiences of volunteers have received far less attention in empirical scholarship compared to the antecedents of volunteering, such as volunteers’ background and personality (Ackermann Citation2019; Handy and Cnaan Citation2007). Li, Cho, and Wu (Citation2022) similarly call for more research on volunteer experiences. Looking beyond antecedents also means investigating not just motivations to start volunteering, but also the factors that encourage volunteers to remain active.

In terms of how volunteering can be encouraged and fostered, Stukas, Snyder, and Clary (Citation2016) stress the importance of further research on how intrinsic and extrinsic motivations affect sustained volunteerism. The notions of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations form the basis of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), in which motivation is conceptualised as a scale running from more intrinsic motivations (in which action is undertaken for the inherent interest in or enjoyment of an activity) to more extrinsic ones (where a certain external outcome or reward is the motivating factor) (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). According to SDT, people are more motivated to take action if their behaviour feels self-determined to them, when they experience “a personal choice and self-control of one’s actions” (Haivas, Hofmans, and Pepermans Citation2013, 1870). From this theoretical perspective, investigating sustained volunteering requires assessment of the degree to which the everyday reality of volunteering stimulates or hampers intrinsic motivation.

SDT argues that an individual’s growth towards this state of self-control is dependent on meeting three fundamental human needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. As described by Chen et al. (Citation2015, 217):

Relatedness satisfaction refers to the experience of intimacy and genuine connection with others (…), whereas relatedness frustration involves the experience of relational exclusion and loneliness. Competence satisfaction involves feeling effective and capable to achieve desired outcomes (…), whereas competence frustration involves feelings of failure and doubts about one’s efficacy. (…) Finally, autonomy refers to the experience of self-determination, full willingness, and volition when carrying out an activity. In contrast, autonomy frustration involves feeling controlled through externally enforced or self-imposed pressures (…).

Before moving to the research aim and questions, we first review what the literature on nature volunteering has found related to volunteers’ reasons to stay and quit, supplemented by insights from the general volunteering literature.

1.3. Reasons to stay and quit in nature volunteering

As argued above, there is a need for more empirical insights into the difficult situations volunteers encounter, and their reasons for staying and quitting. Overgaard (Citation2019) calls for recognition of domain-specific contexts when studying volunteering. For instance, in terms of relatedness, nature-oriented volunteering presents an interesting case context: while volunteering in social domains involves relatedness with other humans, nature volunteering additionally involves a relationship with non-human others, either fellow animals or plants, trees or landscapes. Similarly, Snyder and Omoto (Citation2008) note that there can be important differences in volunteering for in-groups and out-groups, yet nature volunteering does not neatly map onto this dichotomy. Krasny et al. (Citation2014) and Pagès, Fischer, and Van der Wal (Citation2018) add that place-specific and biophysical factors play a specific role of importance when studying nature volunteering, and this form of volunteering may also stand out from other forms of volunteering for its relatively tangible outcomes (Bramston, Pretty, and Zammit Citation2011). These considerations invite research into volunteering experiences in this specific domain.

In line with the literature discussed earlier, some scholars in the field have investigated the differences between motivations to start and reasons to stay as a nature volunteer. For example, Asah and Blahna (Citation2013) found that nature-related motivations scored higher when conservation volunteers were asked why they volunteer in the first place, compared to motivations related to contributing to the community and meeting social aims, which instead were better predictors of volunteers’ sense of commitment. In an earlier study, Ryan, Kaplan, and Grese (Citation2001) had similarly found that volunteers gave high importance to motivations such as learning and contributing to the environment, yet commitment over a longer period of time was better predicted by social relations (meeting new people and bonding with familiar ones) and organisational support (including clarity of tasks and well-organised activities). O’Brien, Townsend, and Ebden (Citation2010) also looked at the experiences of conservation volunteers, including hindering factors. Participants highlighted the physical nature of the work and social bonding with fellow volunteers as important draws, while barriers to continue included a lack of challenge or feedback, and exclusionary group dynamics.

Social factors can thus be important for sustained nature volunteering, but also lead to difficult situations and reasons to quit. This important role of the social setting is confirmed by Abell’s (Citation2013) study of volunteers in animal conservation, which found that social factors played an important role in explaining continued volunteering. Respondents appreciated feeling valued within a project, and meeting and working with likeminded people, while conflicts could arise if some volunteers were perceived as having different goals or priorities, which threatened group motivation and could result in the decision to quit (Abell Citation2013). Studies on volunteering in other domains have confirmed that group processes, such as a lack of appreciation, can be important reasons to quit (e.g. Willems et al. Citation2012), as can conflicts over resources (Hurst, Scherer, and Allen Citation2017) or organisational identity, i.e. how different members of an organisation answer the question “What do we think this organization is really about?” (Kreutzer and Jäger Citation2011, 638). Like Abell (Citation2013) found, conflicting goals or priorities (among volunteers, or between volunteers and their organisation) can be a reason to quit. Locke, Ellis, and Smith (Citation2003, 90) specifically highlight the importance of “a congruence between the goals of the organisation and those of the individual”, and persistent volunteering is linked to identification with the volunteer role (Snyder and Omoto Citation2008) and the organisation. Boezeman and Ellemers (Citation2007) demonstrate that both pride (linked to perceived importance of the volunteer work) and a sense of respect (linked to organisational support) were related to intention to stay.

While the studies by Asah and Blahna (Citation2013) and Ryan, Kaplan, and Grese (Citation2001) thus found that nature-related motivations were more important for initial motivation rather than sustained volunteering, other studies did find the sense of contributing to nature conservation to be an important reason to keep going. Ganzevoort and Van den Born (Citation2020) found that Dutch nature volunteers ranked “contributing to nature conservation” and “being connected to nature” as their main motivation to take action, and Dresner et al. (Citation2015) found that both social bonding and love for working in nature helped to keep some volunteers going. Related to this, these authors found that others quit due to failure to see how their effort could make a significant contribution. Similarly, respondents in a study on environmental volunteering projects in Greece (Liarakou, Kostelou, and Gavrilakis Citation2011, 659) reported that they valued “immediate and visible results”. Gooch (Citation2005) also found that volunteers valued doing important work that contributed to environmental stewardship and learning.

Finally, in terms of difficult situations and reasons to quit, a few studies have highlighted personal issues that affect volunteering. For instance, Pagès, Fischer, and Van der Wal (Citation2018) found personal circumstances, such as commitments to work or family, to be common reasons for conservation volunteers to become inactive, and Gooch (Citation2005) similarly found that stewardship volunteers sometimes struggled to balance volunteering with other time demands (work, family). These results mirror personal factors found in the broader volunteering literature: Locke, Ellis, and Smith (Citation2003) found that common personal reasons to quit include rapid changes in one’s personal life, moving house, or other time commitments (e.g. family care, a new job or the birth of a child).

1.4. Research aim

The preceding sections have demonstrated that there remains much to learn about how volunteers experience their volunteer work, and that there is value in a domain-specific investigation among nature volunteers. As discussed previously, the present study further explores the difficult situations these volunteers experience, and their reasons for staying or quitting.

The objective of the present paper is to provide further insight into the main reasons why nature volunteers decide to quit or continue and how they relate to the three basic needs of SDT, using the Dutch context to do so. Besides formal volunteering, i.e. those activities conducted under the auspices of some formal organisation (Lee and Brudney Citation2012), we also include nature volunteering in more informal settings such as neighbourhood initiatives. This allowed us to include a broader community of nature volunteers, although the goal of our analysis is not to compare both groups. Based on our objectives, we formulated the following four research questions to guide our empirical enquiry:

What are the most difficult situations that nature volunteers report experiencing?

What do nature volunteers report as the most important (actual and potential) reasons to quit nature volunteering?

What do nature volunteers report as the most important reasons to continue their activities?

How do these difficult situations and reasons to stay and quit relate to the three fundamental needs from SDT (autonomy, competence and relatedness)?

2. Data and methods

The data presented in this paper were collected as part of a larger survey study into the profile, motivations and experiences of current Dutch nature volunteers (Ganzevoort and Van den Born Citation2020). As part of a section on volunteers’ experiences, the survey included a series of four open questions to which respondents could enter free-text responses of any length. In line with our research questions, these four questions were as follows (translated from Dutch):

What was the most difficult situation you were confronted with in your nature volunteering? (n = 1,883).

If you know people who quit nature volunteering, what was the most important reason for doing so? (n = 2,039).

For what reason have you ever quit nature volunteering, or what could be a reason for you? (n = 1,852).

What is the most important reason for you to continue with your nature volunteering? (n = 2,730).

We opted for open questions for several reasons. First, we did not identify a suitable existing model or typology to use as a survey instrument, and encountered a limited availability of existing survey items on reasons to stay or quit volunteering, especially in the context of nature-oriented volunteer work. As such, we opted for a more exploratory empirical approach using open survey questions. Perhaps a more important methodological consideration, however, was the added depth a more qualitative analysis of free-text responses would offer (Braun et al. Citation2021): by allowing for free-text responses, we offered respondents the opportunity to voice their reasons and experiences in their own words, without being biased by prompts from pre-designed response options formulated by the researchers. Our questions specified that we were looking for key situations, reasons or considerations; while our objective is not to isolate one “most important” factor at the expense of all others, we did want to challenge our respondents to identify truly crucial considerations for them in the decision to stay or quit.

Formal ethical review and approval were waived for this study, following institutional proceedings at the time of carrying out the empirical work and considering the design of the research and the target population. The research was carried out in full adherence with the research data management policy of the institute to ensure that all relevant ethical principles and guidelines related to data collection and storage were taken into account.

The online survey was launched in October 2017 and distributed through the networks and social media of a great number of Dutch organisations and platforms involved in nature volunteering. These included biodiversity monitoring societies working with volunteers to collect biodiversity data, organisations working with volunteers for nature and greenspace management and restoration, volunteer nature education programmes, botanical gardens and nature-oriented citizen initiatives. We also mobilised the social networks of the volunteers themselves by requesting respondents to send the survey to fellow volunteers. Over the span of five weeks, we collected 3,786 responses; after data cleaning, 3,775 responses remained as the final sample of the survey study.

Since open questions are relatively demanding for respondents, and our questions tackled some potentially sensitive topics, we opted to make each of the four questions optional. This means that response rates differed per question (between 49% and 72%); the number of responses are listed after each of the questions mentioned at the beginning of Section 2. Missing responses are not uncommon for optional open questions, and our aim was not to compare responses at the level of individual respondents. In addition, since even the question with the lowest response rate still left almost 2,000 responses to analyse, we were able to continue with the analytical phase.

In order to analyse these data, for each of the four datasets we used an inductive qualitative coding approach to categorise the answers provided by the respondents. As a first step, the second author carefully read each of the responses in a dataset, applying codes to each response. Since responses sometimes reflected more than one event, reason or issue, we opted to allow more than one code per response, where appropriate. As more codes were developed, these were constantly compared to the existing code list, sometimes resulting in codes being split or merged with previous ones. This process of constant comparison continued until an entire dataset had been fully coded. At this point, a final check of the completed code list was done to verify that codes did not overlap with others and that they reflected the contents of the coded passages well.

These steps resulted in four code lists, one for each of the four datasets. For each code, we then counted the number of times it was used within that dataset, and then we calculated the percentages of total responses in that dataset.

As the final step in our inquiry, we aimed to explore to what degree the main difficult situations and reasons to stay and quit, as experienced and voiced by our respondents, could be categorised under the three fundamental needs from SDT. To do this, we classified the main themes in our responses (see Section 3) along Chen et al.’s (Citation2015) descriptions of satisfaction and frustration of autonomy, competence and relatedness needs.

3. Results

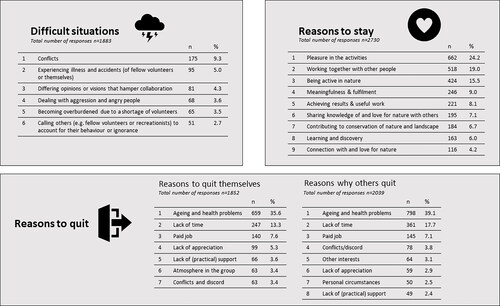

In the following section, we describe the main themes in the responses, based on the most common answers. shows these commonly mentioned difficult situations, reasons to quit and reasons to stay, along with the absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency with which they were reported. In this section, we describe these in more detail, and provide some illustrative quotes from the datasets (translated into English). However, in a qualitative analysis importance should not only be attributed to the most common responses, as it is exactly the diversity in viewpoints and experiences that such approaches aim to discover. As such, in the text we also describe responses that occurred less often, but still revealed some interesting events or experiences.

Figure 1. Most commonly reported difficult situations (

), and reasons to stay (

), and reasons to stay ( ). For each code we list the absolute number of coded passages in a dataset (n) and the relative frequency considering the total number of responses in each dataset (%). For difficult situations and reasons to quit, all codes that were applied at least 50 times were included (with the exception of one “reasons why others quit” that was mentioned 49 times). For reasons to stay, all codes that occurred at least 100 times are reported.

). For each code we list the absolute number of coded passages in a dataset (n) and the relative frequency considering the total number of responses in each dataset (%). For difficult situations and reasons to quit, all codes that were applied at least 50 times were included (with the exception of one “reasons why others quit” that was mentioned 49 times). For reasons to stay, all codes that occurred at least 100 times are reported.

We start with the difficult situations respondents brought up, followed by the reasons to quit (for both the volunteers themselves and fellow volunteers) and reasons to stay. Finally, we end the results section by categorising the responses along the three fundamental needs from SDT: autonomy, competence and relatedness.

3.1. Difficult situations encountered in nature volunteering

When analysing the difficult situations that nature volunteers had to deal with, six types of situations were mentioned more than 50 times (, top left). By far the most mentioned are conflicts: disputes and arguments among volunteers, or between the volunteer and other individuals or involved parties (e.g. nature organisations). Respondents describe situations in which fellow volunteers “demand more and more privileges for themselves little by little, and try to maintain those privileges through intrigue and stirring trouble” or note “conflicts with farmers, local citizens or hunters who are not happy with bird protection measures”. Being confronted with illness, accidents or even death of fellow volunteers is also something that volunteers experience as very difficult and distressing, for instance accidents when performing conservation work such as trimming or cutting trees.

Working on a project together requires a mutually agreed-upon vision, yet this is not always the reality of volunteering. The third most mentioned type of difficult situation related to differences in opinion and clashing visions that obstruct collaboration. These can be among volunteers, but can also relate to disagreement with the decisions or demands made by a volunteer organisation; for example, one respondent struggled with a “mismatch between my vision on sustainability and those of the rest of the organisation”. Nature volunteers also encounter aggression: they mention dog owners who refuse to leash their dogs, angry recreationists or authoritarian colleagues. Moreover, and related to this aggression, several volunteers note that they find it difficult to call people to account to address this kind of behaviour and ignorance.

As will have become clear from our analyses above, five out of the six most common difficult situations that nature volunteers encounter are related to interaction and collaboration with fellow volunteers and others. However, we also encountered one issue of a different order. Because of a general perceived shortage of volunteers and difficulties in recruiting and retaining them, current volunteers frequently feel that they are being asked to do too much. Some specifically refer in this context to the small number of young people that join the group.

Also mentioned regularly, though less so than the situations described above, are managerial hassle, intense physical work, people or organisations that do not stick to agreements and rules, and having to keep enthusing fellow volunteers or excursion participants. Some volunteers also report a lack of appreciation, or feel that they themselves or others lack sufficient knowledge. Others mention macho behaviour and one-upmanship (which, according to these respondents, especially men are guilty of) and situations in which they as women did not feel they were treated equally. Finally, some mention the tension between professionals and volunteers: “The unpleasant feeling that volunteers have to do the work formerly done by paid employees”.

3.2. Reasons to quit nature volunteering

Our analysis indicated a strong resemblance between the reasons to quit for our respondents’ fellow nature volunteers, and the reasons why they themselves have ever quit, or potentially would quit (, bottom). In fact, the top three reasons are identical. By far the most commonly expressed reason in both cases is ageing and health problems: respondents are afraid that advanced age and health problems could make it physically too strenuous to continue their volunteer work in nature. Lack of time, often caused by obligations to family (including family care) and education, are also mentioned often. One volunteer noted in this context that fellow volunteers had quit due to “age, lack of time and because volunteers are asked to do more and more, which slowly changes the voluntary character into something obligatory”. Related to this, we also found signs of conflict between paid and volunteer work: many respondents mention that fellow volunteers quit when they found a job or found their regular job to be too demanding. People also mention that fellow volunteers’ interests changed.

Lack of support and appreciation from organisers were reported as important reasons for fellow volunteers to drop out, but our respondents are especially likely to voice them as reasons for quitting themselves. One respondent would quit if they ever noticed “that my organisation offered no or insufficient support to their volunteers, while at the same time expressing how incredibly happy they are with the efforts of the volunteers”, while another complains about “the totally inactive attitude of the organisation towards the volunteers. Even a New Year’s wish is too much to ask”. Talking about a fellow volunteer quitting, one respondent feels that “conservation organisations don’t listen well (enough) to people on the ground doing the work. People don’t feel like they’re taken seriously”.

In terms of why volunteers would themselves quit (or have done so), atmosphere in the group and conflict were also mentioned relatively often. This confirms findings from section 3.1, as the difficult situations in nature volunteering presented there often related to social interactions (involving fellow volunteers, paid staff or other stakeholders). It thus comes as no surprise that people are inclined to leave if such interactions are not characterised by a positive atmosphere in the group, when conflicts arise, or when people disagree about the direction of the volunteer work and involved organisations, or with the actions of fellow volunteers. One respondent voiced this reason to quit as follows: “When collaborating with colleagues doesn’t go well. There has to be a connection with the people you work with”.

Mentioned less frequently than the reasons above are situations in which bureaucracy and rules prevail or when too much time is spent on administrative tasks: “The organisational stuff, that is something I already have to do at my job. I want to go out in nature and get to work without first having to make all sorts of arrangements”. Volunteers are also inclined to quit if they no longer perceive their work as meaningful and effective. Another reason is moving house, although several respondents mention they would look again for nature volunteer work at their new place. Fellow volunteers also quit because of that reason, and also because of tensions between professionals and volunteers: fellow volunteers sometimes felt that they were doing work previously done by paid employees, and that paid employees think they know better.

Finally, it is striking that although we asked for reasons to quit here, several volunteers emphasise they do not consider quitting at all, as illustrated by responses such as “Stopping is not an option. Nature needs nature workers”, “Stopping with green work is unthinkable for me” and “I have never stopped and would only stop if I pass away”.

3.3. Reasons to continue nature volunteering

The reasons our respondents gave for why they continue nature volunteering are highly diverse (, top right). The top three reasons mentioned relate very strongly to the activities themselves: respondents reported taking pleasure in being involved in their activities, and they enjoy working together with other people. The opportunity to be outside in nature while volunteering is also an important and unique reason to continue with nature volunteering: “To be outside in nature is always a pleasure, especially when it contributes to nature management”. Volunteers report that they want to continue as long as the volunteer work is useful and achieves results, and many add the condition that they experience the work to be meaningful and fulfilling. One respondent notes that “it is fulfilling to be able to give people, young and old, a nice and educational experience in nature” while another comments that “it brings joy and meaning to my retired life”.

Besides the desire to be active in nature, four other nature-related reasons are frequently mentioned. First, we encountered many statements on the importance of passing on love for and knowledge about nature to others. Almost as many respondents are driven to continue by their desire to contribute to the conservation of nature and landscapes, often in their own local area. Finally, we found both learning about, and connectedness with and love for nature, to be important reasons for continued nature volunteering.

Some reasons to stay that were voiced less frequently included: that the work is important and necessary (out of care for nature and the earth); for the sake of future generations; enjoying the beauty of nature; staying healthy by doing nature volunteering; and volunteering being part of respondents’ identity (“Nature volunteering is a way of living for me”).

3.4. The fundamental needs met by nature volunteering

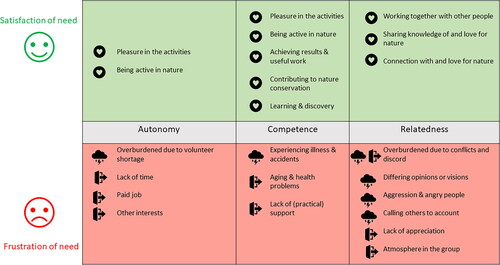

As discussed in the introduction, SDT argues that the decision to stay or quit relates to the degree to which volunteering meets three fundamental needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. We thus categorised each code from under these three fundamental needs. The results of this analysis can be found in .

Figure 2. Codes reflecting the most common survey responses, categorised under the three fundamental needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness). The top half of the figure reflects satisfaction of each fundamental need (green colour), the bottom half frustration of these needs (red colour). The symbols in front of each item reflect the categories of that the code originates from: (difficult situations (

), and reasons to stay (

), and reasons to stay ( ). “Pleasure in the activities” and “Being active in nature” are listed twice.

). “Pleasure in the activities” and “Being active in nature” are listed twice.

As shown by , many of the survey responses encountered in our study align well with the three fundamental needs identified by SDT. In terms of autonomy, several need frustrations were encountered. The clearest example is the feeling of being overburdened by too many tasks due to lack of volunteers. Common reasons to quit related to a lack of time or other commitments (other interests or paid employment) that limited possibilities for investing time in volunteering. In terms of autonomy satisfaction, the clearest expression was found in two key reasons to stay: a pleasure experienced from the volunteering activities, and the opportunity to carry out physical and active work in nature. Both of these suggest an opportunity for volunteers to pursue what they really want to do.

However, these two need satisfactions can also be interpreted as relating more to competence, and are thus also repeated in that section of the figure. Some of the pleasure and joy experienced from the (physical) work in nature may have just as much to do with possessing or developing knowledge, experience and routine in such activities; such developments in confidence and skill contribute to competence satisfaction. The “learning and discovery” reason to stay also aligns with competence, as does the perception of carrying out useful work that contributes to the conservation of nature and landscape. In terms of competence frustration, aging and health problems and a lack of practical support constitute barriers to carrying out one’s volunteering effectively and efficiently. Getting into an accident, or witnessing fellow volunteers get hurt, similarly affects experienced competence.

Finally, we found many dimensions of relatedness in our respondents’ comments. Relatedness frustrations included lacking appreciation, and different expressions of interpersonal tensions (conflict and aggression, clashing visions, or negative group atmosphere). Relatedness satisfaction could be found in two forms: the joy of working with other people (i.e. relatedness to other people), but also experiencing a relatedness with nature through volunteering. Sharing love for and connection with nature with other people could be said to exist at the interface between both of these forms of relatedness.

4. Discussion

Overall, the difficult situations and reasons to stay and quit elicited in this study mapped out well onto the three fundamental needs of SDT: autonomy, competence and relatedness. In terms of autonomy and competence, some interesting points for discussion arise. Two reasons to stay (“pleasure in the activities” and “being active in nature”) seem to relate to both competence and autonomy, depending on one’s interpretation: it may be an indication of increasing confidence and skill (signifying competence satisfaction) or a sense of freedom in choosing what one really wants to do (a clear expression of autonomy). Of course, these are not the only examples of experiences that speak to multiple fundamental needs; for instance, in-group conflicts are a clear relatedness frustration, but frustrations of competence or autonomy may lie at their basis. These observations remind us that the three fundamental needs are connected.

Pressures due to lack of time, employment and other interests were grouped under autonomy frustrations, as they limit the freedom to carry out volunteer work. One may also argue that quitting volunteer work due to work or family pressure is actually an expression of autonomy: not feeling forced to stick with something, but making the active choice to shift priorities. The importance of time as a barrier to volunteering is also recognised in work on the “volunteerability” of current and non-volunteers (Haski-Leventhal et al. 2018): in this model, the choice (not) to volunteer is understood as arising not merely out of one’s willingness and capability, but also one’s availability. Concepts such as volunteerability may thus offer a useful addition to work investigating reasons to stay and quit using the SDT framework.

In terms of relatedness, the SDT framework tends to conceptualise relatedness as relatedness to other people specifically. As argued in our introduction, when investigating action for nature the connection between people and nature is an important factor as both a motivation for nature volunteering and a reason to keep going. This importance of connection with and love for nature for continued volunteering is in line with other studies (Bell et al. Citation2008; Ganzevoort and Van den Born Citation2020; Guiney and Oberhauser Citation2009) that have identified connection with, concern for and desire to learn about nature as important motivations for action for nature. Our investigation makes clear that social relatedness is of great importance in nature volunteering, especially in terms of difficult situations and reasons to quit, but we advocate including nature connectedness in conceptualisations of relatedness needs in the context of action for nature (Pritchard et al. Citation2020). This helps to avoid an overly anthropocentric interpretation that could be too narrow for investigating nature volunteering.

Two of the commonly cited responses did not comfortably fit under one of the three fundamental needs. One reason for fellow volunteers to quit was “personal circumstances”, and analysis of the responses made it clear that there was usually not enough detail to determine which need frustration was most crucial. It is no surprise that this response appeared as a reason to quit communicated by fellow volunteers; “personal circumstances” might be shorthand for people quitting without wishing to provide further elaboration.

The second was a reason to stay: “meaningfulness and fulfilment”. Meaningfulness has been conceptualised in different ways in relation to the three fundamental needs; for example, Scarduzio et al. (Citation2018) argue that in the context of work, meaningfulness can relate to each of the three fundamental needs, and can sometimes even be somewhat distinct from them. We would argue that in nature volunteering, however, there are strong arguments to be made for why meaningfulness has a strong relatedness quality in terms of connectedness with nature. Research shows that meaningfulness is a key motivation for highly committed actors for nature, and that connectedness with nature plays an important part in making action for nature meaningful (Van den Born et al. Citation2018). The literature on relational values of nature has discussed how “living a meaningful life” can be interpreted hedonically and individualistically, but has also argued that meaningfulness often arises out of relationships with nature that have meaning in themselves (and are not a means to an end) (Chan, Gould, and Pascual Citation2018). As such, in our view, a strong case can be made for meaningfulness in the context of action for nature to align mostly with the fundamental need for relatedness, especially connection to nature. However, considering the aforementioned different conceptualisations of meaningfulness, and the fact that our typology in was based directly on our survey responses (which did not always reveal whether meaningfulness came from a connection to nature), we feel there are not sufficient grounds to characterise “meaningfulness and fulfilment” under any of the three fundamental needs. Future research could further explore this connection between relatedness and meaningfulness.

4.1. Implications for practice

As stated in the introduction, scholars have argued that current practices in volunteer management tend to emphasise recruitment at the expense of supporting and appreciating current volunteers (Brudney and Meijs Citation2009). Our results show that volunteers themselves recognise this lack of support and appreciation, as it appears to be a reason to quit for themselves as well as for others. Besides practical reasons to quit (age, health, lack of time), social factors are common difficult situations that can lead to quitting. In line with Byron and Curtis (Citation2001), this shows the importance of helping volunteers to deal with barriers and difficult situations, avoid burnout and prevent volunteers from growing disillusioned with volunteering in the future.

Our results illustrate how the three fundamental needs can help to identify fruitful approaches to meet these needs. In terms of autonomy, respondents expressed how volunteering can allow them to do the things they really want. Houle, Sagarin, and Kaplan (Citation2005) similarly found that the freedom to choose volunteer activities that match personally relevant motivations contributes towards more rewarding volunteering, which may in turn strengthen intentions to remain a volunteer. Studies of community gardening identified similar factors that may lead volunteers to quit: for example, Pitt (Citation2014) highlighted a lack of freedom in carrying out the activities, and Rosol (Citation2012) found that bureaucratic control would diminish commitment amongst community gardeners. Our data give several indications that nature volunteers can experience pressure to carry on their volunteering. This makes supporting autonomy one route through which nature organisations can foster commitment. Recommendations include clearly defined roles that prevent role ambiguity (Harp, Scherer, and Allen Citation2017) as well as freedom and flexibility in choosing and scheduling activities (Haivas, Hofmans, and Pepermans Citation2013; Studer and Von Schnurbein Citation2013).

Relatedness, both in terms of nature relatedness and social relatedness, was similarly of great importance. Relatedness needs may be especially important for volunteers as compared to paid staff (Boezeman and Ellemers Citation2009; Pearce Citation1983) and fostering social interaction (e.g. through offering different routes for volunteers to interact with each other) could support satisfaction of these needs. Clary (Citation1987) highlighted the importance of supporting and showing appreciation for volunteers’ efforts, both in terms of practical support and emotional support (acknowledgement and appreciation). Expressing appreciation and providing emotional support is an important way for organisations to inspire volunteer engagement (Alfes, Shantz, and Bailey Citation2016), and Garner and Garner (Citation2011) illustrate how support offered to volunteers by their organisation becomes especially important in light of negative events or experiences.

Practical support can be offered in diverse ways, for instance by offering educational and training materials or courses, material support (e.g. equipment) and support with legal and administrative tasks. In terms of emotional support, nature organisations would do well to make this clear and explicit, as sometimes it is the small gestures that make volunteers feel seen, valued, supported and taken seriously. In the words of one of our respondents, a simple New Year’s wish should not be too much to ask.

This connects to the importance of feedback. In line with other studies among nature volunteers (e.g. Dresner et al. Citation2015), we found that volunteers greatly value seeing the importance and effectiveness of what they are doing, and understanding how what they do matters for nature conservation. Feedback that makes volunteers’ contribution and value explicit is an important way to achieve this (Guiney and Oberhauser Citation2009). Positive feedback can support satisfaction of competence needs (Tiago et al. Citation2017), may increase volunteers’ pride in their work (Boezeman and Ellemers Citation2007) and can be combined effectively with showing appreciation. In line with work on motivation matching (Clary and Snyder Citation1999), such feedback strategies should take the diverse motivations of volunteers into account.

4.2. Methodological reflection and suggestions for further research

This study is based on a survey approach, using open questions to gain insight in reasons to quit and stay as a nature volunteer. While able to offer new information on these topics, our inquiry also invites future research in several directions. For instance, our data did not include a specific assessment of respondents’ duration of service as a volunteer; future research could incorporate this aspect, for instance by comparing professed reasons to quit and stay with actual behavior. In addition, while our dataset includes both volunteers active for formal nature organisations and informal citizen initiatives (or both), our analysis precluded direct comparison of which reasons to stay and quit were more or less common amongst these subgroups. Future research could also develop more nuanced insights by using qualitative data collection methods. For instance, respondents reported different types of social tensions, ranging from specific conflicts to bad atmosphere in the group or conflicting opinions or visions. To learn more about how volunteers deal with these situations, approaches such as in-depth case studies would be fruitful.

One aspect of the study that would also merit further exploration is the role of the local context in nature volunteering. Nature volunteering activities are often carried out in a greenspace or nature area close to where respondents work or live, and previous research has demonstrated how attachment to place can motivate nature volunteering (Krasny et al. Citation2014) or how nature volunteering can strengthen place bonds (Haywood Citation2019). The data presented in this paper do suggest that attachment to the specific local context matters, as the reason to stay “Contributing to conservation of nature and landscape” was often linked to a local area. However, these data do not shed further light on why local attachments play a role for our study participants. This calls for further research into the role of place attachment in motivating nature volunteering, or how contributing to conservation in a local place can satisfy needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness.

Interestingly, while we found social relatedness as both a reason to quit and reason to stay, we did not find expressions of nature connectedness as a relatedness frustration (e.g. reduced nature connectedness, conflicts with animals or a negative atmosphere in nature). The degree to which relatedness with nature can be a fundamental need frustration would be an interesting avenue for further research. For instance, is nature connectedness perhaps less subject to rapid change than connectedness to other humans, and if so how could this be explained? Future research can also further explore how different forms of relatedness play different roles in the decision to start, stay and quit nature volunteering (e.g. Asah and Blahna Citation2013).

Like most studies based on self-reporting, this study is vulnerable to some biases. Although responses were anonymous, they could still be influenced by the (subconscious) wish to provide socially desirable responses. This may be true especially for the question on reasons to quit of respondents’ fellow volunteers: there is a double danger of interpretation bias here, since participants report to us what others told them. Some volunteers might have quit because of in-group conflicts or clashing visions, but opted to tell the group that they did not have time anymore. However, while we recognise these possible biases, we also consider the collected data on this issue very valuable, as it provides us with insight into a larger group than only our study participants. Moreover, our high number of respondents helps to strengthen the reliability of our results.

5. Conclusions

Reasons for continuing to volunteer can be different compared to the initial motivations to do so (Clary, Snyder, and Stukas Citation1996), and the decision to stay or quit is influenced by both individual factors (e.g. motivations) and the events and circumstances encountered in the everyday reality of volunteering (Clary and Snyder Citation1999; Penner Citation2002). This highlights the importance of eliciting and understanding the situations that volunteers encounter.

To contribute to this research agenda, this study reports on the difficult situations nature volunteers experienced and on their reasons to stay or quit nature volunteering. Regarding difficult situations and reasons to quit, a significant finding is that many of the situations, barriers and reasons reported by our respondents do not appear specific to nature volunteering, rather matching well with factors identified in earlier research on broader volunteering. These common factors include practical and personal issues of time and health, group tensions and conflicts, a feeling of being overburdened with requests to volunteer, and a lack of support or appreciation.

However, some barriers and issues seem to be more characteristic to the activities common to nature volunteering. For instance, some respondents highlighted how bureaucratic control and administrative tasks presented a barrier to get in contact with nature. This speaks to how many types of nature volunteering involve relatively physical tasks (especially those related to nature management or restoration) while simultaneously relating to the general competence need of wanting to see direct positive impact of one’s action. The physical nature of such work can be an important draw for participants (e.g. O’Brien, Townsend, and Ebden Citation2010), but as our results show they may also constitute reasons to quit (for instance due to ailing health), or may increase the risk of accidents and injuries, competence frustrations that were mentioned frequently as difficult situations. Dealing with anger or aggression, such as in conflicts with recreationists over protected areas, is a relatedness frustration that may be relatively common in some types of nature volunteering.

When looking at the most important reasons to stay, they seem to be mainly action-oriented (taking pleasure in the activities, achieving results, being active in nature) and a clear relatedness need, namely working together with other people. All other reasons to continue volunteering are more specific to nature volunteering, such as sharing love for and knowledge of nature, connectedness with nature and learning about nature. The importance of enjoyment in the volunteer work and productive co-operation with other people, and the significant impact of conflicts and personal circumstances on the decision to quit, show that the everyday reality of nature volunteering involves nature-related, individual and social motivations and fits well with the three fundamental needs of SDT.

Finally, it is important to reflect on the broader context of nature volunteering. In line with discourses extolling the virtues of active citizenship, there is an increasing pressure on citizens to actively contribute to nature and greenspace (Buijs et al. Citation2019). While recognition of the great contribution and potential of nature volunteering is a positive thing, such pressure has its risks. Our data illustrate how some volunteers feel that they are being asked to do too much, or do work previously done by paid staff, both of which may eventually factor into the decision to quit. Increasing pressures to volunteer may frustrate fundamental needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness and by doing so erode intrinsic motivation and deplete volunteer energy in the long term (Brudney and Meijs Citation2013). Considering the importance of a sense of freedom and lack of coercion, organisations and governments should be careful in how they approach promoting nature volunteering. By taking the experiences and motivations of current nature volunteers as a starting point, as this study does, it becomes evident that motivations relate to the three fundamental human needs of SDT. Therefore, key priorities will be to not only support and appreciate nature volunteers, but also give them the ability to choose and perform activities that fulfil their autonomy, competence and relatedness needs. Moreover, volunteers are driven to act for nature in pursuit of a meaningful life, which should be recognised in order to preserve both their motivation and their crucial importance for nature conservation now and in the future.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was conducted as part of the PhD thesis of the first author. We thank Bernadette van Heel for research support. Finally, our gratitude goes to all our respondents who took the time to tell us about their reasons to stay and reasons to quit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to considerations of participant privacy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- “Actieplan Groene Vrijwilligers” [Action Plan Green Volunteers]. 2018. http://www.degroenevrijwilliger.nl/over-het-manifest/.

- Abell, J. 2013. “Volunteering to Help Conserve Endangered Species: An Identity Approach to Human–Animal Relationships.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 23 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1002/casp.2114.

- Ackermann, K. 2019. “Predisposed to Volunteer? Personality Traits and Different Forms of Volunteering.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (6): 1119–1142. doi:10.1177/0899764019848484.

- Alfes, K., A. Shantz, and C. Bailey. 2016. “Enhancing Volunteer Engagement to Achieve Desirable Outcomes: What Can Non-Profit Employers Do?” International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 27 (2): 595–617. doi:10.1007/s11266-015-9601-3.

- Asah, S. T., and D. J. Blahna. 2013. “Practical Implications of Understanding the Influence of Motivations on Commitment to Voluntary Urban Conservation Stewardship.” Conservation Biology 27 (4): 866–875. doi:10.1111/cobi.12058.

- Bell, S., M. Marzano, J. Cent, H. Kobierska, D. Podjed, D. Vandzinskaite, H. Reinert, A. Armaitiene, M. Grodzińska-Jurczak, and R. Muršič. 2008. “What Counts? Volunteers and Their Organisations in the Recording and Monitoring of Biodiversity.” Biodiversity and Conservation 17 (14): 3443–3454. doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9357-9.

- Bixler, R. D., S. L. Joseph, and V. M. Searles. 2014. “Volunteers as Products of a Zoo Conservation Education Program.” The Journal of Environmental Education 45 (1): 57–73. doi:10.1080/00958964.2013.814618.

- Boezeman, E. J., and N. Ellemers. 2007. “Volunteering for Charity: Pride, Respect, and the Commitment of Volunteers.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 92 (3): 771–785. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.771.

- Boezeman, E. J., and N. Ellemers. 2009. “Intrinsic Need Satisfaction and the Job Attitudes of Volunteers versus Employees Working in a Charitable Volunteer Organization.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 82 (4): 897–914. doi:10.1348/096317908X383742.

- Bramston, P., G. Pretty, and C. Zammit. 2011. “Assessing Environmental Stewardship Motivation.” Environment and Behavior 43 (6): 776–788. doi:10.1177/0013916510382875.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, E. Boulton, L. Davey, and C. McEvoy. 2021. “The Online Survey as a Qualitative Research Tool.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24 (6): 641–654. doi:10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550.

- Brudney, J. L., and L. C. P. M. Meijs. 2009. “It Ain’t Natural: Toward a New (Natural) Resource Conceptualization for Volunteer Management.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38 (4): 564–581. doi:10.1177/0899764009333828.

- Brudney, J. L., and L. C. P. M. Meijs. 2013. “Our Common Commons: Policies for Sustaining Volunteer Energy.” Nonprofit Policy Forum 4 (1): 29–45. doi:10.1515/npf-2012-0004.

- Buijs, A., R. Hansen, S. Van der Jagt, B. Ambrose-Oji, B. Elands, E. L. Rall, T. Mattijssen, et al. 2019. “Mosaic Governance for Urban Green Infrastructure: Upscaling Active Citizenship from a Local Government Perspective.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 40: 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.06.011.

- Bussell, H., and D. Forbes. 2002. “Understanding the Volunteer Market: The What, Where, Who and Why of Volunteering.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 7 (3): 244–257. doi:10.1002/nvsm.183.

- Byron, I., and A. Curtis. 2001. “Landcare in Australia: Burned out and Browned off.” Local Environment 6 (3): 311–326. doi:10.1080/13549830120073293.

- Chan, K. M. A., R. K. Gould, and U. Pascual. 2018. “Editorial Overview: Relational Values: What Are They, and What’s the Fuss About?” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 35: A1–A7. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.003.

- Chen, B., M. Vansteenkiste, W. Beyers, L. Boone, E. L. Deci, J. Van der Kaap-Deeder, B. Duriez, et al. 2015. “Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Need Frustration, and Need Strength across Four Cultures.” Motivation and Emotion 39 (2): 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1.

- Clary, E. G. 1987. “Social Support as a Unifying Concept in Voluntary Action.” Journal of Voluntary Action Research 16 (4): 58–68. doi:10.1177/089976408701600408.

- Clary, E. G., and M. Snyder. 1999. “The Motivations to Volunteer: Theoretical and Practical Considerations.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 8 (5): 156–159. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00037.

- Clary, E. G., M. Snyder, and A. A. Stukas. 1996. “Volunteers’ Motivations: Findings from a National Survey.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 25 (4): 485–505. doi:10.1177/0899764096254006.

- Dresner, M., C. Handelman, S. Braun, and G. Rollwagen-Bollens. 2015. “Environmental Identity, Pro-Environmental Behaviors, and Civic Engagement of Volunteer Stewards in Portland Area Parks.” Environmental Education Research 21 (7): 991–1010. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.964188.

- Ganzevoort, W., and R. J. G. Van den Born. 2020. “Understanding Citizens’ Action for Nature: The Profile, Motivations and Experiences of Dutch Nature Volunteers.” Journal for Nature Conservation 55: 125824. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125824.

- Garner, J. T., and L. T. Garner. 2011. “Volunteering an Opinion: Organizational Voice and Volunteer Retention in Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40 (5): 813–828. doi:10.1177/0899764010366181.

- Gooch, M. 2005. “Voices of the Volunteers: An Exploration of the Experiences of Catchment Volunteers in Coastal Queensland, Australia.” Local Environment 10 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1080/1354983042000309289.

- Guiney, M. S., and K. S. Oberhauser. 2009. “Conservation Volunteers’ Connection to Nature.” Ecopsychology 1 (4): 187–197. doi:10.1089/eco.2009.0030.

- Haivas, S., J. Hofmans, and R. Pepermans. 2013. “Volunteer Engagement and Intention to Quit from a Self‐Determination Theory Perspective.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (9): 1869–1880. doi:10.1111/jasp.12149.

- Handy, F., and R. A. Cnaan. 2007. “The Role of Social Anxiety in Volunteering.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 18 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1002/nml.170.

- Harp, E. R., L. L. Scherer, and J. A. Allen. 2017. “Volunteer Engagement and Retention: Their Relationship to Community Service Self-Efficacy.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 46 (2): 442–458. doi:10.1177/0899764016651335.

- Haski‐Leventhal, D., L. C. P. M. Meijs, L. Lockstone‐Binney, K. Holmes, and M. Oppenheimer. 2018. “Measuring Volunteerability and the Capacity to Volunteer among Non‐Volunteers: Implications for Social Policy.” Social Policy & Administration 52 (5): 1139–1167. doi:10.1111/spol.12342.

- Haywood, B. 2019. “Citizen Science as a Catalyst for Place Meaning and Attachment.” Environment, Space, Place 11 (1): 126–151. doi:10.5749/envispacplac.11.1.0126.

- Hobbs, S. J., and P. C. L. White. 2012. “Motivations and Barriers in Relation to Community Participation in Biodiversity Recording.” Journal for Nature Conservation 20 (6): 364–373. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2012.08.002.

- Houle, B. J., B. J. Sagarin, and M. F. Kaplan. 2005. “A Functional Approach to Volunteerism: Do Volunteer Motives Predict Task Preference?” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 27 (4): 337–344. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2704_6.

- Hurst, C., L. Scherer, and J. Allen. 2017. “Distributive Justice for Volunteers: Extrinsic Outcomes Matter.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 27 (3): 411–421. doi:10.1002/nml.21251.

- Krasny, M. E., S. R. Crestol, K. G. Tidball, and R. C. Stedman. 2014. “New York City’s Oyster Gardeners: Memories and Meanings as Motivations for Volunteer Environmental Stewardship.” Landscape and Urban Planning 132: 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.08.003.

- Kreutzer, K., and U. Jäger. 2011. “Volunteering versus Managerialism: Conflict over Organizational Identity in Voluntary Associations.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40 (4): 634–661. doi:10.1177/0899764010369386.

- Lee, Y. J., and J. L. Brudney. 2012. “Participation in Formal and Informal Volunteering: Implications for Volunteer Recruitment.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 23 (2): 159–180. doi:10.1002/nml.21060.

- Li, C., H. Cho, and Y. Wu. 2022. “Basic Psychological Need Profiles and Correlates in Volunteers for a National Sports Event.” International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 33 (2): 322–333. doi:10.1007/s11266-020-00307-5.

- Liarakou, G., E. Kostelou, and C. Gavrilakis. 2011. “Environmental Volunteers: Factors Influencing Their Involvement in Environmental Action.” Environmental Education Research 17 (5): 651–673. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.572159.

- Locke, M., A. Ellis, and J. D. Smith. 2003. “Hold on to What You’ve Got: The Volunteer Retention Literature.” Voluntary Action 5 (3): 81–99.

- McKinley, D. C., A. J. Miller-Rushing, H. L. Ballard, R. Bonney, H. Brown, S. C. Cook-Patton, D. M. Evans, et al. 2017. “Citizen Science Can Improve Conservation Science, Natural Resource Management, and Environmental Protection.” Biological Conservation 208: 15–28. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.015.

- Merenlender, A. M., A. W. Crall, S. Drill, M. Prysby, and H. Ballard. 2016. “Evaluating Environmental Education, Citizen Science, and Stewardship through Naturalist Programs.” Conservation Biology 30 (6): 1255–1265. doi:10.1111/cobi.12737.

- O’Brien, L., M. Townsend, and M. Ebden. 2010. “Doing Something Positive’: Volunteers’ Experiences of the Well-Being Benefits Derived from Practical Conservation Activities in Nature.” VOLUNTAS 21 (4): 525–545. doi:10.1007/s11266-010-9149-1.

- Overgaard, C. 2019. “Rethinking Volunteering as a Form of Unpaid Work.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (1): 128–145. doi:10.1177/0899764018809419.

- Pagès, M., A. Fischer, and R. Van der Wal. 2018. “The Dynamics of Volunteer Motivations for Engaging in the Management of Invasive Plants: Insights from a Mixed-Methods Study on Scottish Seabird Islands.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61 (5–6): 904–923. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1329139.

- Pearce, J. L. 1983. “Job Attitude and Motivation Differences between Volunteers and Employees from Comparable Organizations.” Journal of Applied Psychology 68 (4): 646–652. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.68.4.646.

- Penner, L. A. 2002. “Dispositional and Organizational Influences on Sustained Volunteerism: An Interactionist Perspective.” Journal of Social Issues 58 (3): 447–467. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00270.

- Pitt, H. 2014. “Therapeutic Experiences of Community Gardens: Putting Flow in Its Place.” Health & Place 27: 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.02.006.

- Pritchard, A., M. Richardson, D. Sheffield, and K. McEwan. 2020. “The Relationship between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (3): 1145–1167. doi:10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6.

- Reis, H. T., K. M. Sheldon, S. L. Gable, J. Roscoe, and R. M. Ryan. 2000. “Daily Well-Being: The Role of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26 (4): 419–435. doi:10.1177/0146167200266002.

- Rosol, M. 2012. “Community Volunteering as Neoliberal Strategy? Green Space Production in Berlin.” Antipode 44 (1): 239–257. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00861.x.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Ryan, R. L., R. Kaplan, and R. E. Grese. 2001. “Predicting Volunteer Commitment in Environmental Stewardship Programmes.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 44 (5): 629–648. doi:10.1080/09640560120079948.

- Scarduzio, J. A., K. Real, A. Slone, and Z. Henning. 2018. “Vocational Anticipatory Socialization, Self-Determination Theory, and Meaningful Work: Parents’ and Children’s Recollection of Memorable Messages about Work.” Management Communication Quarterly 32 (3): 431–461. doi:10.1177/0893318918768711.

- Snyder, M., and A. M. Omoto. 2008. “Volunteerism: Social Issues Perspectives and Social Policy Implications.” Social Issues and Policy Review 2 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2409.2008.00009.x.

- Studer, S., and G. Von Schnurbein. 2013. “Organizational Factors Affecting Volunteers: A Literature Review on Volunteer Ccoordination.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 24 (2): 403–440. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9268-y.

- Stukas, A. A., M. Snyder, and E. G. Clary. 2016. “Understanding and Encouraging Volunteerism and Community Involvement.” The Journal of Social Psychology 156 (3): 243–255. doi:10.1080/00224545.2016.1153328.

- Tiago, P., M. J. Gouveia, C. Capinha, M. Santos-Reis, and H. M. Pereira. 2017. “The Influence of Motivational Factors on the Frequency of Participation in Citizen Science Activities.” Nature Conservation 18: 61–78. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.18.13429.

- Van den Born, R. J. G., B. Arts, J. Admiraal, A. Beringer, P. Knights, E. Molinario, K. Polajnar Horvat, et al. 2018. “The Missing Pillar: Eudemonic Values in the Justification of Nature Conservation.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61 (5–6): 841–856. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1342612.

- West, S. E., and R. M. Pateman. 2016. “Recruiting and Retaining Participants in Citizen Science: What Can Be Learned from the Volunteering Literature?” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 1 (2): 15. doi:10.5334/cstp.8.

- Willems, J., G. Huybrechts, M. Jegers, T. Vantilborgh, J. Bidee, and R. Pepermans. 2012. “Volunteer Decisions (Not) to Leave: Reasons to Quit versus Functional Motives to Stay.” Human Relations 65 (7): 883–900. doi:10.1177/0018726712442554.

- Wilson, J. 2012. “Volunteerism Research: A Review Essay.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41 (2): 176–212. doi:10.1177/0899764011434558.