Abstract

This article contributes to the increasing traction of social justice in marine spatial planning (MSP) by exploring perceptions and experiences of social justice from the viewpoint of planners and different social groups who were included and (self)excluded in MSP processes. The study builds on empirical material from Poland, Latvia, and Germany consisting of interviews, MSP legislation, and documents that were analysed through the lens of a multidimensional social justice framework centring on recognition, representation, distribution, and capabilities. Results indicate that MSP institutional arrangements constrain possibilities for marginalised and less consolidated actor groups (residents, coastal tourism, and small-scale fisheries) to enjoy the same degree of recognition that is given to groups representing strategic national interests (renewable energy and shipping). We also highlight the role of planners’ self-reflectivity in enhancing/depriving capabilities of vulnerable social groups whose wellbeing and multidimensional relationships with the sea call for institutional responses adaptive to specific planning contexts.

1. Introduction

The rollout of marine/maritime spatial planning (MSP) policy and practice has been guided by high ambitions to unlock sustainable blue growth while realizing environmental and social goals at sea (Ehler, Zaucha, and Gee Citation2019). Recently, however, there are emergent concerns that MSP is too heavily biased towards blue growth, thereby limiting its capacity to be a socially integrative and equitable planning instrument that facilitates multidimensional sustainability at sea (Grimmel et al. Citation2019; Gilek, Saunders, and Stalmokaitė Citation2018; Strand, Rivers, and Snow Citation2022; Saunders, Gilek, and Tafon Citation2019). Social justice plays an essential role in promoting marine sustainability as it supports the recognition of the rights of coastal communities and vulnerable groups,Footnote1 facilitates fair participation and representation, and ensures equitable sharing of the benefits and costs associated with the marine environment’s values, resources, and experiences (Crosman et al. Citation2022; Evans et al. Citation2023; Bennett et al. Citation2021). In response, increasing attention has been given to deepening the understanding of social justice-related concerns, including research on how participation, knowledge and power are included in MSP (cf. Flannery et al. Citation2020; Jentoft Citation2017; Tafon Citation2019a; Gilek et al. Citation2021; Pikner et al. Citation2022). What has been broadly labeled, blue justice scholarship has begun to investigate and influence the potentially transformative role of MSP. Blue Justice, here, refers to the concept of applying principles of justice to the marine context related to a broad range of issues, including marine planning and governance, marine conservation, and sustainable use of coastal and ocean resources. Areas of interest include distributions of ocean risks, burdens, and benefits (Bennett Citation2018; Saunders, Gilek, and Tafon Citation2019; Saunders et al. Citation2020), and democratization of the planning processes (Yet et al. Citation2022; Bennett et al. Citation2019), for instance, through enabling influential involvement of vulnerable and marginalized groups such as women, small-scale fishers (Gustavsson et al. Citation2021), and Indigenous communities (Bennett et al. Citation2021). Other areas of interest include strategies to identify, as well as “hear” and “see”, sociocultural values and local knowledge (Strand, Rivers, and Snow Citation2022; Gee et al. Citation2017) and how to better recognize and address conflict and stakeholder tyrannies that arise or fester as blue growth practices intensify (Tafon et al. Citation2022). Previous research also notes that social justice in MSP can support and enable recognition of multiple ocean claims linked to human wellbeing and especially that of vulnerable communities, who are increasingly exposed to competing interests over ocean space and resources (Jouffray et al. Citation2020). While much of the blue justice scholarship focuses on justice concerns that can be broadly termed as “social” (i.e. the human dimension of justice), some scholars have expanded the concept of blue justice beyond social wellbeing concerns, drawing particular attention to injustices of non-human nature, which recent blue growth and ocean-related climate policies may create or amplify (Tafon, Saunders, Pikner, et al. 2023; Saunders et al. Citation2020). As this paper does not examine justice concerns related to non-human nature, we use the term social (rather than blue) justice to reflect our focus on the social dimension of blue justice.

Despite the increasing body of scholarship on social justice in marine governance and MSP, there is limited empirically informed understanding of how social justice is framed, invoked, claimed, and experienced by stakeholders in MSP planning processes. In response, Tafon, Saunders, Zaucha, et al. (Citation2023) elaborated a four-dimensional social justice framework for the empirical analysis of MSP and ocean governance interventions in terms of (1) recognition, which refers to the extent to which affected, and often less organized, actors are acknowledged and included in the planning process, with consideration given to their rights, social identities, status, vulnerabilities, risks, and capacities; (2) procedural justice, which relates to issues of procedural (un)fairness, including transparency, representation, inclusion and planning processes and decisions that affect weaker or vulnerable stakeholders; (3) distribution, which captures (un)fair distributions of risks, burdens, benefits, and responsibilities that culminate through planning practices and plans; and (4) capabilities, which refers to enhancing the opportunities and freedoms that vulnerable or neglected communities have in relation to MSP to pursue their goals and aspirations in a way that promotes their wellbeing. In the context of MSP, this framework can help to identify and address issues of recognition, access, and distribution of marine experiences, values, and resources, particularly in relation to vulnerable or neglected communities.

To study how diverse social groups are recognized, included in decision-making, and given access to marine values, experiences, and resources, we apply a social justice theoretical framework to three Baltic Sea cases of MSP. Our aim is to contribute to a deeper understanding of how social justice is currently finding expression in MSP and explore ways in which it can be better integrated into planning processes to support just outcomes.

After this introductory Section 1, Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, while Section 3 describes the methodology. Section 4 presents the results and Section 5 discusses the broader literature and implications of the findings. Section 6 summarizes the key findings and outlines future research needs.

2. Theoretical framework: social justice in MSP

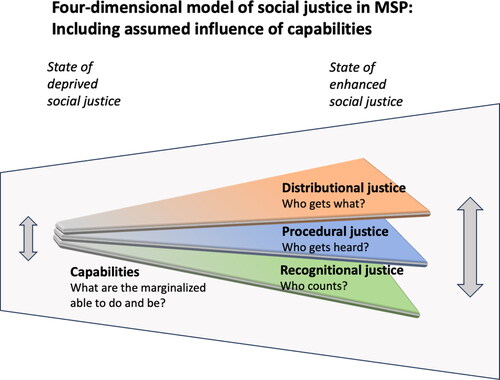

A conceptual understanding of social justice in relation to MSP is integral to informing, balancing, and contextualizing the competing demands of sustainability’s multidimensional goals: society, environment, and economy (Saunders et al. Citation2020). We draw on social justice and capability theories as developed by Honneth (Citation1995), Fraser (Citation2009), and Nussbaum (Citation2006) to both analyse how aspects of recognitional, procedural, and distributive (in)justice manifest in Baltic Sea MSP practices and explore modalities for enhancing the capabilities of affected actor groups. In doing so, our work builds on, and empirically advances, the four-dimensional conceptual account of social justice in MSP elaborated by Tafon, Saunders, Zaucha, et al. (Citation2023). As noted earlier, in this paper we only focus on the social (i.e. people-centred) dimension of blue justice, leaving out the ecological dimension, which is nonetheless critical to achieving MSP’s multidimensional sustainability objectives. Furthermore, our social justice framework views recognitional, procedural, and distributive justice as well as capability as interdependent and indivisible, yet for analytical clarity we treat them individually (see ).

Figure 1. Four-dimensional conceptual model of social justice in marine spatial planning (MSP) consisting of recognitional, procedural, distributional justice as well as capabilities. The model shows how these different social justice dimensions and their interactive dynamic become more distinctive as social justice is enhanced. Adapted from Tafon, Saunders, Zaucha, et al. (Citation2023).

The first aspect of justice is recognition, which entails the organisation of a system of political and civil rights that allows actors to be respected as autonomous beings with the same rights as others. Rather than at the level of individual powerholders, recognition theory focuses on structural arrangements to close gaps in access to social power (economic, organizational, etc.), which renders disadvantaged groups more vulnerable to different ocean interventions. Because of its focus on the structural sources of injustice, we assume that recognition is foundational for the realization of the other three aspects of justice. That is, we see recognition – of differential identities (ethnic, religious, gender, and racial) and values, as well as socioeconomic and political statuses and capacities – as a precondition for procedural and distributive justice. From a capability perspective, a recognition-informed MSP would go beyond simply acknowledging difference and diversity. Rather, as a public policy intervention, MSP would seek to strengthen the capabilities and resilience of weaker groups so that they can better enjoy multidimensional wellbeing relationships with the sea, while effectively contributing to and reaping benefits from blue growth, renewable energy transitions, climate change mitigation, and environmental care. Recognition in this radical sense does not limit itself to invited, participatory spaces of MSP, where exclusionary politics and injustice may take a more “visible” form. Rather, it takes seriously the institutional conditions that script relatively “safe” or innocuous issues into public debate, and potentially problematic ones out. Such institutional elements include among others, policy and regulatory instruments both at the national level (e.g. MSP regulation and sectoral legislation) and at the supranational level (e.g. the EU MSP Directive, blue growth/economy policies) which privilege strategic sectors such as defence, renewables, deep-sea mining, among others, over smaller sectors and people’s ties to the sea, and the democratic norms of participation, accountability, diversity, gender equality, and human rights.

Our second aspect of justice is procedural justice, which we conceptualize, based on research on MSP practices, in terms of three principles: participation, balance, and self-reflectivity. The participation principle holds that the aim of justice is to ensure the fairness and inclusivity of ocean decision-making processes, with particular emphasis on involving and giving voice to marginalized social actors. The balancing principle maintains that the role of the marine planning process is to strike a fair balance between different ocean values, interests, needs, and ways of knowing in relation to different views of sustainability. In the context of social justice, striking a balance means ensuring that blue growth practices and global climate actions align with the norms of place-based socio-natural ties and interdependencies, social inclusion, and distributive fairness. Finally, the self-reflectivity principle holds that the function of the planner is not simply to ensure correct application of planning regulation to the planning process, but to self-reflect – to question their own knowledge and routine actions and be critical of the norms that structure them. In other words, a self-reflective agent would not limit themselves to the general planning rules but combine these with practical knowledge of the critical moment, or the particular circumstances of context that require critical action (Tafon et al. Citation2019), which in MSP could mean bridging the land-sea divide (Jay Citation2022), among others.

The third aspect, distributive justice can be broadly defined as concerned with the way risks, responsibilities, burdens, and benefits associated with an intervention, in this case, expansion of the blue economy, climate change, and conservation are distributed across social groups. For such distributions to be truly equitable, the greatest burden and cost should be borne by those most responsible for environmental/climate change as well as those who have benefitted most from past and ongoing environmental degradation, while positive discrimination should be put in place to empower marginalized groups most vulnerable to the change, i.e. through enhancing their capabilities.

Our fourth element of social justice, viz. capability, considers structural enablers and impediments to people’s ability to live a fulfilling life. In theorizing capability, Nussbaum considered how lack of attention to difference (at the intersection of age, (dis)ability, ethnicity, nationality, and species) affects groups’ potentials and wellbeing. A capability approach to justice also draws attention to how people relate to place and nature, and how unreflective governance practices may inhibit socio-natural relationships. From this view, capability theory explains why certain things such as landscape, fishing, community, job security, place identity, a “quiet” sea, an “unindustrialized” or “attractive” coast, care for nature, etc., matter to people (Tafon, Saunders, Zaucha, et al. Citation2023). We, therefore, take capability enhancement to mean factors that enable less powerful actors to live a fulfilling life that they have defined for themselves, which could mean fuller engagement conducive to social wellbeing, i.e. the aesthetic, emotional, environmental, religious, livelihood, or economic benefits that the sea might offer them. Besides being conducive to groups’ attainment of wellbeing, capability enhancement is also beneficial to ocean sustainability, in the sense that communities with enhanced capability can participate more effectively and enhance MSP goals. Indeed, coastal communities are sometimes important change agents or ocean stewards and defenders who seek to improve socially and environmentally unjust ocean interventions and practices.

Gleaned from the above arguments, it seems that positive interventions at the structural level (recognition) are likely to increase marginalized actors’ prospects for more effective participation and influence in MSP, which in turn, can increase distributional benefits for these actors. When all these three dimensions of social injustice are addressed, MSP and related governance institutions can become an important avenue for, and enabler of, enhanced capabilities for the marginalized, thereby leading to social justice. As Schlosberg (Citation2007, 143) noted in his attempt to advance the capabilities approach in environmental institutions, it “is a lack of flourishing that is indicative of injustice, and the absence of specific capabilities that produce flourishing that is to be remedied.” We, therefore, believe that increased recognition, fair participation, and equitable planning outcomes can empower people with capabilities necessary for achieving social wellbeing, flourishing and integrity.

In examining our conceptual framework (see ) across the three case studies, we acknowledge the fundamental role of structural intervention in efforts to enhance the capabilities of weaker groups. While structural transformations are fundamental to a socially just and capability-enhancing MSP, they are not the only remedy and are often not easily achievable. Planners can also play a role at the procedural level, particularly through applying self-reflectivity and explicitly working around structural impediments to meaningfully include vulnerable or structurally neglected social groups (Jentoft Citation2017; Jouffray et al. Citation2020; Saunders et al. Citation2020; Tafon et al. Citation2019).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach and case selection

To analyse how the four justice dimensions play out in MSP practices, we focus on three case study countries in the Baltic Sea Region, namely Poland, Latvia, and Germany. Our cross-case research design places a deliberate focus on one justice dimension (except for capabilities) in each case study setting. While we recognise the interconnected nature of the four justice dimensions described above and the value of a full comparison of all dimensions across the three cases, we consciously highlight real-life examples to illustrate how each dimension plays out in a practical MSP context. That said, the complexity of empirical reality demands that we, at least in part, also explicate the non-focused dimensions given the integrated character of the multidimensional social justice framework. In adopting this study design, we are concerned with not only bringing clarity to the dynamics of justice within each social justice dimension but also rendering how these often-abstract theoretical concepts are given expression in the reality of MSP practices. We also accept that this approach, as well as the inclusion of only three MSP cases, constrains our ability to make more comprehensive comparisons and generalizations.

Past knowledge/studies of the respective MSP plans and planning processes guide the choice of these cases and their relevance to each social justice dimension chosen for study. Prior research has established that Poland’s first MSP plan put considerable effort into securing the recognition of all stakeholders. Latvia is considered a leader in terms of representation. Germany, with planning legislation demanding “orderly” and “balanced” spatial development in the long term (Federal Spatial Planning Act §1 and 2) and a first round of MSP in the EEZ, criticised for unequal distributional effects (Aschenbrenner and Winder Citation2019; Jay et al. Citation2012), can be expected to consider distributional effects at least to some degree, while distribution was not an obvious issue for Poland as an MSP newcomer. We note that each of our case study countries has a different governance context (e.g. overlapping jurisdictions, see in the online supplementary material), influencing opportunities for participation, which may be more strongly focused on the local and regional level in Latvia and Germany (Länder), different from Poland and Germany (EEZ) with their national MSP approach and the associated domination of national goals over local and regional ones. This differing context is important when considering which stakeholders are invited to participate in each MSP process.

In line with the EU (2014) MSP Directive, all three case study countries have MSP plans in place, but only Germany is implementing second-generation plans. Poland and Latvia each have a general MSP plan covering their respective exclusive economic zones (EEZ), territorial sea and inland waters. Germany has a plan for the EEZ (covering both the North Sea and the Baltic Sea) and three state-level plans encompassing both terrestrial areas and the territorial sea (see Figure 1 in the online supplementary material).

We focused on three MSP plans and associated processes, namely the Latvian and Polish general MSP plans and the Federal State of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV) MSP plan in Germany (for an overview of MSP planning context in each country see and Table 1 in the online supplementary material). The MV plan was chosen as representing the Baltic Sea; in addition, this plan has been in place for some time (unlike the EEZ plan which was in the process of being revised while the study was conducted). All selected countries were part of several EU pilot and research projects focusing on different aspects related, albeit indirectly, to social justice such as participation, knowledge and stakeholder integration.Footnote2 Accordingly, the possibility to draw on previous research findings (e.g. BaltSpace project) as well as the existing expertise within the research team (e.g. knowledge of MSP planning contexts and practices in respective countries as well as abilities to read document material and engage in interviews in the different case country languages) were taken into consideration during the selection of case study countries and the respective MSP plans.

3.2. Data and analysis

Our analysis draws on multiple data sources such as interviews, planning documents, MSP legislation, and previous literature (see Table 2 in the online supplementary material). In line with our emphasis on different dimensions of social justice in each country, our empirical focus and sampling strategies differed between the cases (e.g. in Poland, institutional arrangements related to recognition were given more weight).

In each country, planning and legal documents and existing overviews were used to obtain a detailed understanding of the planning context and institutional conditions which guide MSP processes and, with this, opportunities for implementing social justice dimensions in respective case countries. For example, plans were analysed to highlight any MSP objectives and/or planning principles related to social justice; MSP legislation was analysed to e.g. establish the scope for public participation in MSP processes (see Table 2 in the online supplementary material).

Document analysis was complemented by semi-structured interviews with planners and/or national authorities and selected stakeholders. Stakeholders were defined as sector organisations, NGOs, scientists, local entrepreneurs, and residents (see ). A point was made to interview stakeholders who were involved in the respective MSP processes, as well as some who chose not to participate (such as some local authorities in Latvia), including those who felt strongly underrepresented or had a negative opinion of the MSP process (such as fishers in Poland) or were not specifically invited as a group (e.g. young people).

Table 1. A Summary of interviews.

Interviews were conducted in two stages. The first stage covered MSP planners, MSP authorities, and stakeholders involved in the respective MSP process. Based on some of the issues identified in these interviews, additional stakeholders were interviewed to gain more insight into specific topics. In the Polish case, for example, the number of interviewees was enlarged from initially 11 to 26 stakeholders to cover stakeholders not represented properly in MSP. Non-participating stakeholders were identified based on similar experience in terrestrial contexts.

A list of representatives of each stakeholder group was drawn up for each country based on the knowledge of the planners involved in the respective MSP processes (such as which sectors are relevant in each country and who participated in public consultation on draft plans). The aim was to interview at least one representative per stakeholder category. Potential interviewees were contacted by email or telephone. The number of interviews conducted per category ultimately depends on the scope and scale of the MSP process (in Poland, for example, many more planners were involved than in Germany), but also on constraints experienced during the empirical phase, such as Covid-related travel restrictions which limited outreach. Some sector representatives and local entrepreneurs contacted declined to be interviewed, making bias in our sample inevitable.

An interview guide was drawn up that was used in all three countries, reflecting the social justice dimensions of recognition, procedural justice, and distribution, and asking slightly different questions of planners and stakeholders (see Table 3 in the online supplementary material). Interviews focused on the roles, practices, experiences, and perceptions of a wide set of practitioners and stakeholder groups. This included planners and those groups of actors who were included and (self)excluded in Latvian, Polish, and German MSP processes. (Self)excluded groups included those stakeholders who were informed but did not participate and those who were not properly informed about the MSP process. Interviews were one-to-one, with interviewees asked about procedural aspects such as identification and prioritization of various groups of actors during the planning process, planners’ engagement with stakeholders, constraints, and possibilities for designing inclusive/just MSP plans, as well as mechanisms that were used to consider social implications of MSP. Due to the Covid pandemic, most interviews took place online or via telephone, although some were conducted in person.

In addition, five complementary interviews conducted as part of the BaltSpace research project (in 2016) were re-analysed. This was particularly relevant for the German case where experience of the process is not as fresh as in Poland and Latvia. The BaltSpace interviews covered a broad range of topics, with some lines of questioning specific to participation and representation in MSP, which made them suitable for re-analysis in this particular context. They enabled incorporating local national authorities’ and sectoral actors’ experiences.

All interviews were fully transcribed in the respective native languages, anonymized, and subsequently analysed with the aid of NVivo software. A coding scheme was developed iteratively, using the relatively broad definitions of social justice dimensions set out in Section 2 to define sub-codes which could be placed under the three overarching codes of recognition, procedural justice, and distribution. Capabilities were operationalized as a cross-cutting dimension; this is explicitly addressed in the discussion, focusing on how social justice could be more effectively adopted in MSP. All coded text passages were translated into English to allow for joint analysis and comparison. Text passages from the interviews that explain a point particularly well were selected as quotes. Although all social justice dimensions were coded for each country individually, and there are similarities in how these dimensions present themselves across all case countries, our findings highlight the thematic focus chosen for each country (see Section 3.1).

4. Findings

4.1. Recognitional justice in Polish MSP

4.1.1. Structural (mis)recognition of vulnerable social groups

Our findings indicate that current legislative frameworks, which regulate and shape the MSP process, structurally empower some social groups more than others and establish status inequalities already in the formative stages of the MSP process. For example, the Polish MSP legislation (Act Citation1991) distinguishes public authorities from other groups of actors and stipulates different degrees of influence they are entitled to exercise in MSP decision-making. While some public authorities such as line ministries in charge of defence, economy, fisheries, environment, tourism, transport, and culture as well as environmental protection agencies, coastal and regional governments and seaport authorities are given the right to agree or disagree with MSP decisions, other public authorities such as regional heritage agency, regional and national water management authority, etc., including the public, are given the right to submit an opinion during the MSP consultation process. In practice, this means that MSP legislation does not recognise the equal right of some actor groups to participate in the MSP process on a par with others. Although Polish MSP planners recognised this obstacle from the beginning of the planning process and tried to follow general spatial planning principles in order to balance different interests, this proved difficult to uphold in practice. The fact that de jure recognition of public authorities in MSP law provides them with more rights to participate in the MSP process is reflected in the experiences of one interviewed planner:

Those institutions indicated in the Act as having consenting power on the plan have an advantage over other stakeholders. They have a stronger bargaining power than the general public. (PL_Interview-2, planner)

The companies involved in the development of offshore farms had very strong interventions […] stakeholders related to national defence […] I did not notice a tendency to dialogue, but rather, [they] communicated how their requirements needed to be taken into account. (PL_Interview-8, national authority)

I am afraid that these [prioritised groups] would primarily be industry groups, more related to the maritime economy than to living in the vicinity of maritime areas, or to marine life, like these fishermen, [who are] cultivating on the one hand a form of employment but on the other hand a certain family tradition. (PL_Interview-11, urban planner)

That economic issues are taken into account the most, then, due to the already existing structures of environmental protection, ecological issues are taken into account […] and social issues are generally the least deeply considered, due to the fact that they were not recognized [in MSP]. (PL_Interview 4, urban planner)

We know that there are some priorities, and energy is the strategic one. And fishing, which produces little GDP, is doomed to failure in this context […] The loss of sea areas that will be granted to wind turbines in the future is a tragedy for us […] It may also turn out that the fisherman will have to avoid windmills, extending the travelling distance. (PL_Interview-20, fisherman)

4.1.2. Fragmentation among vulnerable groups – an obstacle for recognition and participation

In contrast to institutionally empowered sectoral actor groups and public authorities, some interviewees raised a concern that coastal residents, the publics as well as SSFs, were underrepresented in the Polish MSP process. The group diversity of vulnerable social groups (i.e. SSFs) and broader publics’ diverse relationships with the coast and sea (cultural, economic, and social) were challenging to incorporate in the MSP process. Although Polish planners exercised self-reflectivity and recognised the vulnerabilities of SSFs in the MSP stocktaking report (i.e. pre-planning stage), addressing the multidimensional, place-based interests of SSFs proved difficult in the course of planning despite planners’ (extra) efforts to arrange consultations with SSFs in their working environment. Internal fragmentation within fishery groups, their distributed (unconsolidated) character and failure to be able to “talk in one voice” were highlighted as factors contributing to their relative weak position vis-a-vis other stakeholder groups such as shipping, OWE or the defence sector. For example, one interviewed representative from the tourism sector reflected on why there were difficulties in effectively including parts of civil society:

They [inhabitants of coastal municipalities] are more neglected than they even think. The plan took into account the needs and interests of a large lobby, a strong stakeholder, and the weak, because they are dispersed, remained uninformed. (PL_Interview-12, business and tourism representative)

One specific set of interest groups which was not included were people living in the area not connected with the use of the sea or the coast in terms of having some profit out of it directly. But simply citizens. And these are very diverse […] but they might have something interesting to say. (PL_Interview-18, national authority)

I think that fishermen may have some emotional stress… since they treat the sea as their homeland. They have such emotional connection with the sea […]. If in fact, there was a situation that they would be cut off from the sea in some way. (PL_Interview-5, business representative)

Meetings must be on point and purposeful, specifically devoted to a given type of fishery […] Other meetings are necessary when we are talking about coastal fisheries, others are necessary when we are talking about larger fisheries, that is, with trawl units above 12 meters. They have different priorities […] and we, coastal fishermen, have different priorities. (PL_Interview-19, fisherman)

4.2. Procedural justice in Latvian MSP

4.2.1. Structural conditions enabling and hindering representation of different social groups

The Latvian spatial planning law referring to MSP does not specify how social groups beyond sectoral actors or public authorities are expected to engage in MSP. However, the principles that guide MSP (see Table 1 in the online supplementary material) suggest that planners are required to balance the interests of various actors with respect to sustainable spatial development, including the general public and private individuals. Nonetheless, the public participation strategy of Latvian MSP distinguishes between three stakeholder groups: those who are expected to be (i) informed; (ii) consulted; and (iii) actively involved. Although the public is entitled to participate in the planning process, the planning authorities are obliged to inform and consult the public in the decision-making processes rather than to actively involve it. During the MSP elaboration in Latvia, the general public were informed and consulted via media and public hearings held at coastal regional cities and the capital. Although the general public was given a chance to present their opinions during the public consultations, interviews with national level planners and a coastal tourism entrepreneur suggest that a top-down planning approach stymied their effective and meaningful participation. The general public(s) was not considered a competent and relevant stakeholder (i.e. in terms of active engagement in MSP decision-making). In addition, they were assumed to be represented through other stakeholder groups. This is reflected in the experiences of those involved in MSP plan development:

Maybe we didn’t involve society [meaning the public] as such, although representatives of society were present at the meetings we organized in the coastal areas. But we didn’t have a strong emphasis on society [as a stakeholder]. Still, […] during the process [I felt] that society does not have knowledge about the sea, it is something abstract for them. (LV_Interview-7, planner)

I have a feeling that in our [county name] the opinion of local residents has never been important … the public hearing was during a working day, if you have to work, you cannot be present. So only few municipality officials were there. (LV_Interview-12, coastal tourism entrepreneur)

In addition to the general public, Latvian MSP regulations and planners also distinguish between two groups of actors who are expected to actively engage in MSP decision-making process namely (i) the MSP working group comprised of representatives from public authorities and sectoral organizationsFootnote4, and (ii) strategic sectoral stakeholders representing national interests (i.e. ports, shipping, defence, fisheries, environment protection, and energy). One such targeted group of stakeholders is the OWE sector with institutional support from international and national-level policies. Our results show that planners perceived OWE developers to be a silent/self-excluded stakeholder since during the elaboration of Latvian MSP, they did not show particular interests (LV_Interview-11, planner, national authority). Consequently, planners used their discretion to adopt targeted communication aimed to actively engage OWE developers:

We, as a ministry, took their [energy sector] role and got into a fight for their place. They didn’t have any proposals until we involved them in scenario seminars and made them draw [locations] on the maps. (LV_Interview-11, planner, national authority)

The setup of equal stakeholders is present at the start of every planning process. Then during the process corrections have to be made due to particular stakeholders who can just veto everything. The shipping sector used their tools […] like council of ports to get the wanted result. (LV_Interview-11, planner, national authority)

The military was probably the only one who could say – you know, that’s how it’s going to be. […] There was a plan for a wind farm, they said – no, there won’t be any wind farms, because they interfere with a radar. (LV_Interview-4, scientist)

Tourism [representation] was not nationally organized, so the local interests were not taken into account very much […] we tried to make meetings with the tourism, they were more like some kind of individual representatives, but there was [not] such a representation of the industry and clearly defined interests. (LV_Interview-7, plan developer)

4.2.2. Ambiguous role of coastal municipalities and misrepresentation of the public

Latvian coastal municipalities are expected to participate in MSP processes because they are responsible for planning and managing the 2 km zone seawards from the coastline. They are also responsible for representing the interests of residents in high-level strategic planning documents such as the MSP. However, interviews with planners from local municipalities and national authorities indicate that the participation of coastal municipalities in MSP was marginal at best. According to a representative from the national authority, local municipalities were not actively engaged:

They [coastal municipalities] were informed but were quite inactive and didn’t submit any proposals because they simply didn’t have them. So, the local level and the local community have not understood to full extent their linkage with MSP. (LV_Interview-11, planner, national authority)

We mostly learned and listened there. There was not much to object […] The sectoral experts were present, and we were mostly a receiving side who nods – yes, that’s so […] It all was balanced and worth to support from our viewpoint. (LV_Interview-10, local planner)

They [LV MSP planners] have made many infographics and videos… They have done some work on how to explain it… I think it should be explained more […] there is a need to explain how they [general public] can profit from the MSP plan and its implementation. (BaltSpace interview, planning region)

4.3. Distributional justice of German MSP in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

4.3.1. Structural conditions influencing distributional justice

The second MSP plan covering internal and territorial sea areas of MV is part of the Spatial Development Programme (LEP) of MV, which applies to the entire territory of the State including its marine territory. The MV Spatial Planning Act (Landesplanungsgesetz - LPlG) specifies a set of general principles to which an LEP must adhere. While some of these principles refer to specific elements (e.g. infrastructure, nature, economic development), two principles are fundamental, namely that plans and measures should contribute to equivalent living conditions in all parts of the State, and that plans must aim to balance competing spatial functions and demands. A balanced allocation of marine space that affords access to marine space to different social groups regardless of their living location and contributes to quality of life can be understood as distributional justice.

While state planning law specifies sectors and topics to which the LEP must refer, there is no additional specification for the marine part of the LEP. This allows considerable scope for the planning authority to design MSP in response to the topics and issues at hand. Nonetheless, sectoral priorities arise from international obligations (i.e. EU-level directives) regarding nature conservation and shipping, or Federal policies linked to renewable energy. This implies giving privilege to some sectors in the sense that space must be made available for these functions (DE_Interview-4, planner). For the 2016 plan, relevant sectors and topics were offshore wind farming, cables and pipelines, shipping, fishery and aquaculture, tourism and recreation, coastal protection, raw material extraction and nature conservation.

4.3.2. Stakeholder and planner perceptions on distribution of harms and benefits

Conducted interviews with planners in Germany indicate that distributional justice is often associated with equivalent living conditions and balance, both of which are important principles in state development planning. However, balancing allocation of space in the territorial sea, e.g. in terms of ensuring access to sea and engagement of the general public in MSP decision-making were found to be challenging. Interviewees noted that the principle of equivalent living conditions is difficult to apply in the sea since it is not inhabited by people (DE_Interview-2, Interview-4, Interview-9). Nonetheless, planners emphasized the need to regard land and sea as “one space” rather than distinct planning spaces with distinct groups of stakeholders: “Yes, the sea is not inhabited, but still, it has so much influence on land, and we influence it in return. So […] I wouldn’t want to exclude anyone.” (DE_Interview-4, planner).

Even though coastal citizens may feel distant from the MSP planning context, planners acknowledged the importance of the sea to coastal regions (job creation, wellbeing, etc.) (DE_Interview-4, planner). The strategic nature of an LEP compared to regional or municipal plans represents an additional barrier for some stakeholders, in particular the general public to become involved, as this makes the plan more abstract and remote:

Well, an LEP is […] [on] an abstract level, where stakeholders probably don’t necessarily feel so directly affected. Or they don’t know exactly how and where they are affected. (DE_Interview-5, State planning advisory board)

To involve, let’s say, the public bodies, that can be done relatively well. But we wanted to involve the population, the individuals. So informal formats helped us to get closer to the people […] Sometimes the impacts of the LEP’s provision on living conditions only become apparent at second glance, and that’s what we wanted to get into a discussion on. And this goes beyond representatives of citizens, like associations and so on. It’s about the people themselves. (DE_Interview-10, planner)

A good spatial planning result is characterised by the fact that everyone feels a bit of a loser […] you have to compromise. All those who clearly have a claim to space, in particular environment and the economy, they would all liked to have got a bit more. (DE_Interview-4, planner)

The first draft of the LEP contained a lot more areas for offshore wind. They were then taken out as a result of protests. It was a real movement that arose. […] FREIER HORIZONT [a campaign] mobilized coastal tourism, so it was both. Certainly, those in the municipalities affected by wind energy, plus the tourism operators on the coast. (DE_Interview-7, fisheries)

It was very clear from the texts that offshore wind energy was one of the State’s major goals […] Some things were dropped in the second draft. (DE_Interview-8, Water and Shipping Directorate)

So, these areas [the areas planned as nursery areas] became reservation areas for fishery […]. And the fishers were happy. I think it’s good that fishery was considered at all. (DE_Interview-7, ENGO)

The planning authority and the fishers struggled with this for some time, there were intense conversations. Now things have calmed down a bit, but it really was a tug of war. But this is also […] to show that spatial planning can do something for [small-scale coastal] fishery. (DE_Interview-4, planner)

So, there are topics that go into the process with more weight or are important early in the process and might have some parameters already established. Still, the purpose of planning is to connect different issues. […] So other factors come into play, such as landscape and how attractive is the coast for tourists […] the desire to preserve traditional small-scale coastal fishery, and to achieve a balance between it all. (DE_Interview-4, planner)

5. Discussion

The previous sections elaborated on MSP stakeholder and planner perspectives linked to recognitional, procedural, and distributive justice across three countries as well as institutional conditions shaping differential recognition of some social groups in MSP processes. In the following section we discuss how different dimensions of social justice influence stakeholders’ capabilities, or lack thereof, to engage and benefit from the use of marine space and resources. Although our study provides a country-specific analysis, we situate our findings within a broader MSP literature which enhances the relevance of our observations.

First, in all of the MSP contexts, recognition and representation of coastal (and other) publics and other less organized or consolidated sectors (such as SSFs and coastal tourism) are not institutionally emphasized in MSP. These findings resemble earlier observations suggesting that actors with a strong institutional representation have more favourable conditions to participate and influence the outcome of marine governance processes compared to individuals, less organized stakeholders and vulnerable groups (Flannery and Ó Cinnéide Citation2008; Jentoft Citation2017; Jones, Lieberknecht, and Qiu Citation2016). This has several implications for MSP’s sustainability goals and justice ambitions. In contrast to previous research indicating avenues for socially inclusive MSP processes (e.g. Finke et al. Citation2020), our results show that institutional settings that have grown up around MSP limit the inclusion and consideration of diverse place-based, socially situated values and knowledge. This is likely to inhibit coastal people’s capabilities to nurture their wellbeing and socio-cultural relationships with the sea such as placed-based attachments, aesthetics, livelihoods, economic opportunities as well as environmental care; all of which are important for the realization of multidimensional sustainability goals at sea. Similarly, Zuercher et al. (Citation2022) raise the concern that while most existing MSP plans give emphasis to environmental, economic, and governance concerns, they remain silent about other objectives linked to human wellbeing, cultural heritage, Indigenous rights, human safety, and climate change. This is also evident in the formal ambitions and practices that we have scrutinised in the MSP cases we have examined here.

Second, our findings indicate that while extant institutional arrangements can entrench social justice inequalities, through the imprimatur of formal relative privilege, planners have varying levels of discretion to exercise self-reflectivity when engaging in planning practice. This may be to conduct more targeted recognition and inclusion of marginalized groups (e.g. SSFs and coastal communities in Germany and recognition of SSFs vulnerabilities in Poland) or to ensure that more strategic interests are countenanced (e.g. OWE in Latvia). These insights relate to earlier observations by Ehler, Zaucha, and Gee (Citation2019) that MSP processes require continuous reinterpretation and adaptation to changing social preferences. Our results indicate the role of planners’ agency in this process and support earlier calls (e.g. Kidd and Ellis Citation2012; Tafon et al. Citation2019) for marine planners to self-reflect and alleviate the adverse social distributional impacts that MSP plans may create.

Relatedly, the second iteration of MSP process in Germany showed planner reflectivity to the extent that there was a willingness to reconsider the initial allocation of sea space to strategic imperatives, such as OWE, when it became apparent that other coastal interests, such as tourism were likely to be adversely affected. This was also the case with SSFs, where German planners appeared to consider how SSFs could be meaningfully included in MSP. While the Polish MSP case showed that Polish planners demonstrated self-reflectivity by recognising and reporting the vulnerabilities of SSFs during the preplanning stage of MSP, this faded away during the course of planning (cf. Ciołek et al. Citation2018; Piwowarczyk et al. Citation2019; Tafon Citation2019b). Whether this was because of differences in institutional recognition between stakeholders and/or the difficulty encountered when engaging with SSFs in MSP is not clear. Meanwhile, the Latvian MSP process indicated how planners’ discretion to exercise self-reflectivity advanced representation of self-excluded sectoral stakeholders such as OWE and smaller ports. These examples show that planners’ self-reflectivity can be directed to enact capabilities of vulnerable groups of actors but also of those groups that already enjoy a strong institutional representation. This resonates with Jay’s (Citation2022) argument for the importance of an experiential approach to marine planning whereby planners’ knowledge and planning processes can be improved via direct engagement with (vulnerable) stakeholders. Accordingly, understanding the needs of different sea users via direct observation of their interaction/relationships with the sea could potentially lead to increased self-reflectivity of the planner and in turn deliver planning decisions that are more just to all social groups regardless of their differentiated formal recognition.

Finally, further means to enhance capabilities of currently marginalized social groups in MSP would be to explicitly elevate coastal populations (in their diversity) to (at least) equal formal recognitional status with other strategic interests and to emphasise that place-based stakeholder engagement is paramount to understanding the different place-based relationships and contexts in which MSP will have effects. The “abstract character” of MSP, as evidenced by stakeholder perspectives across all case countries, has been seen to be an impediment to constructively engage broader publics. As evident in Germany and in Polish planners’ experiences linked to SSFs, a more relational and situated planning approach coupled with strategic planning to further common goods is important for coastal actors’ wellbeing. Such an approach is more likely to generate more knowledge around socio-cultural values and nature-people relationships that may be important for the wellbeing of different social groups (and conservation interests).

6. Concluding remarks

The results of the MSP cases studied in this article display that the conceptual framework developed to examine social justice is able to generate multidimensional analytical insights highlighting existing impediments/enablers affecting different social groups’ engagement in MSP practices across different planning contexts.

The three cases presented, focusing on different dimensions of social justice, illustrated how current institutional arrangements work to constrain recognition and inclusion, but also how planners have some discretionary capacity (which they may or may not exercise) to adopt “workaround strategies” to mitigate the effects of differentiated formal recognition. The Polish case showed how differentiated institutionalized recognition can lead to constraints in who counts in MSP, and shape the scope for planner reflectivity (i.e. oriented towards specific groups of marginalized actors such as SSFs but not others e.g. different coastal publics) which can have negative flow-on effects for ‘weaker’ and less organized stakeholders. The Latvian case also highlighted challenges in representation of coastal voices but also how planners proactively engaged with self-excluded stakeholder groups. Meanwhile, benefitting from previous MSP experience relating to difficulties to engage and gain trust from SSFs and local communities, the German case showed that the more reflective (and responsive) MSP practices were able to go some way to redressing power imbalances between institutionally privileged stakeholders (e.g. offshore wind developers) and marginalized social groups (e.g. SSFs). The resulting more targeted recognition and inclusion of SSFs and coastal communities in the second-generation MSP process in the German case, enabled greater consideration and inclusion of placed-based relationships, values and knowledge of the sea that would have been overlooked by adopting an overly strategic sectoral approach. It also enabled a more nuanced planning approach that is likely to be more inclusive and deliver more just outcomes but also reflects a broader range of relationships to the sea important for wellbeing. On the other hand, the first-generation MSP processes in Poland and Latvia, seemingly provided less experiential scope for planners to practice self-reflectivity enabling meaningful inclusion of vulnerable social groups. Whether this was also due to particular institutional pressures (time, costs, etc.), first-time experience of MSP, the effects of historical legacies, the prevalence of strategic interests (international/national) or because the marginalized actors themselves were less active in these jurisdictions remains to be clarified in future research.

To conclude, a four-dimensional social justice approach to MSP consisting of recognitional, procedural, distributional justice as well as capabilities would not forgo consideration of strategic interests that fulfil a common good or need. However, it may help to analyse and address more directly how institutionalized disadvantages could be alleviated, so as to better understand and enact MSP to capture a broader range of socio-environmental relationships important to both social justice and the realization of sustainability more generally. Hence, while this study generated some enhanced insights on how social justice is practiced and can be strengthened in various MSP jurisdictions in the Baltic Sea region, additional multidimensional analysis of social justice in MSP is called for. In particular, we urge for more capabilities-centred research to generate more acute understandings of important multidimensional relationships with the sea of currently often marginalized MSP actors (e.g. SSFs, coastal inhabitants, tourism operators, local NGOs, etc.).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (94.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful to five anonymous reviewers and the editor for providing insightful comments on early versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Following Saunders et al. (Citation2020) we see vulnerable groups as those that “stand to be most ‘harmed’ or whose values/benefits, experiences, and forms of knowledge have been marginalized/misrecognized in MSP (and/or the broader society)—in other words, ‘the worst off.’” (7).

2 Projects: BaltSeaPlan (2009–2012), PartiSEApate (2012–2014), BaltSpace (2015–2017), and Baltic SCOPE (2015–2017).

3 During the development of the Polish MSP plan, a new strategic document “Poland's energy policy until 2040” was prepared. According to this document (adopted by the Council of Ministers in February 2021) offshore wind energy is foreseen to have a capacity of 5.9 GW by 2030 and the first OWE are to be built by 2024.

4 According to the rules laid down in the Cabinet Regulation No. 740 Procedures for the Development, Implementation and Monitoring of the Maritime Spatial Plan, Adopted 30 October 2012, the MSP working group should consist of (i) representatives of the ministry in charge of MSP development as well as line ministries in charge of defence, foreign affairs, economy, internal affairs, culture, transport, justice and agriculture (ii) representatives from the Cross-sectoral Coordination Centre, Kurzeme planning region, Riga planning region, and (iii) representatives from sectoral organizations: Latvian Association of Coastal Local and Regional Governments, the Environmental Advisory Council, the Fisheries Advisory Council, the Latvian Port Association, the Latvian Transit Business Association.

5 Stakeholders’ submissions: http://awd.mv-regierung.de/lep_2014_01/index.php,%20accessed%2024%20August%202022

References

- Act. 1991. “Act concerning the Maritime Areas of the Polish Republic and the Marine Administration, 21 March 1991 with Further Amendments.” Journal Laws of the Republic of Poland 1991 No. 32 item 131.

- Aschenbrenner, Marie, and Gordon M. Winder. 2019. “Planning for a Sustainable Marine Future? Marine Spatial Planning in the German Exclusive Economic Zone of the North Sea.” Applied Geography 110: 102050. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.102050.

- Bennett, Nathan J. 2018. “Navigating a Just and Inclusive Path towards Sustainable Oceans.” Marine Policy 97: 139–146. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001.

- Bennett, Nathan J., J. Blythe, A. M. Cisneros-Montemayor, G. G. Singh, and U. R. Sumaila. 2019. “Just Transformations to Sustainability.” Sustainability 11 (14): 3881. doi:10.3390/su11143881.

- Bennett, Nathan James, Jessica Blythe, Carole Sandrine White, and Cecilia Campero. 2021. “Blue Growth and Blue Justice: Ten Risks and Solutions for the Ocean Economy.” Marine Policy 125: 104387. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387.

- Ciołek, Dorota, Magdalena Matczak, Joanna Piwowarczyk, Marcin Rakowski, Kazimierz Szefler, and Jacek Zaucha. 2018. “The Perspective of Polish Fishermen on Maritime Spatial Planning.” Ocean & Coastal Management 166: 113–124. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.07.001.

- Crosman, Katherine M., Edward H. Allison, Yoshitaka Ota, Andrés M. Cisneros-Montemayor, Gerald G. Singh, Wilf Swartz, Megan Bailey, et al. 2022. “Social Equity is Key to Sustainable Ocean Governance.” Npj Ocean Sustainability 1 (1): 4. doi:10.1038/s44183-022-00001-7.

- Ehler, C., J. Zaucha, and K. Gee. 2019. “Maritime/Marine Spatial Planning at the Interface of Research and Practice.” In Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future, edited by J. Zaucha and K. Gee, 1–21. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Evans, Louisa S., Pamela M. Buchan, Matt Fortnam, Maria Honig, and Louise Heaps. 2023. “Putting Coastal Communities at the Center of a Sustainable Blue Economy: A Review of Risks, Opportunities, and Strategies.” Frontiers in Political Science 4: 1032204. doi:10.3389/fpos.2022.1032204.

- Finke, Gunnar, Kira Gee, Anja Kreiner, Maria Amunyela, and Rodney Braby. 2020. “Namibia’s Way to Marine Spatial Planning - Using Existing Practices or Instigating Its Own Approach?” Marine Policy 121: 104107. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104107.

- Flannery, Wesley, Hilde Toonen, Stephen Jay, and Joanna Vince. 2020. “A Critical Turn in Marine Spatial Planning.” Maritime Studies 19 (3): 223–228. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00198-8.

- Flannery, Wesley, and Micheál Ó Cinnéide. 2008. “Marine Spatial Planning from the Perspective of a Small Seaside Community in Ireland.” Marine Policy 32 (6): 980–987. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2008.02.001.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2009. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gee, Kira, Andreas Kannen, Robert Adlam, Cecilia Brooks, Mollie Chapman, Roland Cormier, Christian Fischer, et al. 2017. “Identifying Culturally Significant Areas for Marine Spatial Planning.” Ocean & Coastal Management 136: 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.026.

- Gilek, Michael, Aurelija Armoskaite, Kira Gee, Fred Saunders, Ralph Tafon, and Jacek Zaucha. 2021. “In Search of Social Sustainability in Marine Spatial Planning: A Review of Scientific Literature Published 2005–2020.” Ocean & Coastal Management 208: 105618. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105618.

- Gilek, Michael, Fred Saunders, and Ignė Stalmokaitė. 2018. “The Ecosystem Approach and Sustainable Development in Baltic Sea Marine Spatial Planning: The Social Pillar, a ‘Slow Train Coming’.” In The Ecosystem Approach in Ocean Planning and Governance, edited by David Langlet and Rosemary Rayfuse, 160–194. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Grimmel, Henriette, Helena Calado, Catarina Fonseca, and Juan Luis Suárez de Vivero. 2019. “Integration of the Social Dimension into Marine Spatial Planning – Theoretical Aspects and Recommendations.” Ocean & Coastal Management 173: 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.02.013.

- Gustavsson, Madeleine, Katia Frangoudes, Lars Lindström, María Catalina Álvarez Burgos, and Maricela de la Torre-Castro. 2021. “Gender and Blue Justice in Small-Scale Fisheries Governance.” Marine Policy 133: 104743. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104743.

- Honneth, Axel. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Jay, Stephen. 2022. “Experiencing the Sea: Marine Planners’ Tentative Engagement with Their Planning Milieu.” Planning Practice & Research 37 (2): 136–151. doi:10.1080/02697459.2021.2001149.

- Jay, Stephen, Thomas Klenke, Frank Ahlhorn, and Heather Ritchie. 2012. “Early European Experience in Marine Spatial Planning: Planning the German Exclusive Economic Zone.” European Planning Studies 20 (12): 2013–2031. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722915.

- Jentoft, Svein. 2017. “Small-Scale Fisheries within Maritime Spatial Planning: Knowledge Integration and Power.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (3): 266–278. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2017.1304210.

- Jones, Peter, J. S., L. M. Lieberknecht, and W. Qiu. 2016. “Marine Spatial Planning in Reality: Introduction to Case Studies and Discussion of Findings.” Marine Policy 71: 256–264. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.04.026.

- Jouffray, Jean-Baptiste, Robert Blasiak, Albert V. Norström, Henrik Österblom, and Magnus Nyström. 2020. “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean.” One Earth 2 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2019.12.016.

- Kidd, Sue, and Geraint Ellis. 2012. “From the Land to Sea and Back Again? Using Terrestrial Planning to Understand the Process of Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 14 (1): 49–66. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2012.662382.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2006. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pikner, Tarmo, Joanna Piwowarczyk, Anda Ruskule, Anu Printsmann, Kristīna Veidemane, Jacek Zaucha, Ivo Vinogradovs, and Hannes Palang. 2022. “Sociocultural Dimension of Land-Sea Interactions in Maritime Spatial Planning: Three Case Studies in the Baltic Sea Region.” Sustainability 14 (4): 2194. doi:10.3390/su14042194.

- Piwowarczyk, Joanna, Magdalena Matczak, Marcin Rakowski, and Jacek Zaucha. 2019. “Challenges for Integration of the Polish Fishing Sector into Marine Spatial Planning (MSP): Do Fishers and Planners Tell the Same Story?” Ocean & Coastal Management 181: 104917. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104917.

- Polish MSP Plan. 2021. DZIENNIK USTAW RZECZYPOSPOLITEJ POLSKIEJ Warszawa, dnia 21 maja 2021 r. Poz. 935 ROZPORZĄDZENIE RADY MINISTRÓW z dnia 14 kwietnia 2021 r. w sprawie przyjęcia planu zagospodarowania przestrzennego morskich wód wewnętrznych, morza terytorialnego i wyłącznej strefy ekonomicznej w skali 1:200 000, with further amendments Journal of Laws of 2022, item 2518.

- Saunders, Fred, Michael Gilek, Anda Ikauniece, Ralph Voma Tafon, Kira Gee, and Jacek Zaucha. 2020. “Theorizing Social Sustainability and Justice in Marine Spatial Planning: Democracy, Diversity, and Equity.” Sustainability 12 (6): 2560. doi:10.3390/su12062560.

- Saunders, Fred, Michael Gilek, and Ralph Tafon. 2019. “Adding People to the Sea: Conceptualizing Social Sustainability in Maritime Spatial Planning.” In Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future, edited by Jacek Zaucha and Kira Gee, 175–199. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schlosberg, David. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature: Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Strand, Mia., Nina Rivers, and Bernadette Snow. 2022. “Reimagining Ocean Stewardship: Arts-Based Methods to ‘Hear’ and ‘See’ Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Ocean Management.” Frontiers in Marine Science 9:1 doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.886632.

- Tafon, Ralph. 2019a. “The “Dark Side” of Marine Spatial Planning: A Study of Domination, Empowerment and Freedom through Theories of Discourse and Power.” PhD diss., Södertörn University.

- Tafon, Ralph, Bruce Glavovic, Fred Saunders, and Michael Gilek. 2022. “Oceans of Conflict: Pathways to an Ocean Sustainability PACT.” Planning Practice & Research 37 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1080/02697459.2021.1918880.

- Tafon, Ralph, Fred Saunders, and Michael Gilek. 2019. “Re-Reading Marine Spatial Planning through Foucault, Haugaard and Others: An Analysis of Domination, Empowerment and Freedom.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (6): 754–768. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1673155.

- Tafon, Ralph, Fred Saunders, Tarmo Pikner, and Michael Gilek. 2023. “Multispecies Blue Justice and Energy Transition Conflict: Examining Challenges and Possibilities for Synergy between Low-Carbon Energy and Justice for Humans and Nonhuman Nature.” Maritime Studies 22 (4): 45. doi:10.1007/s40152-023-00336-y.

- Tafon, Ralph, Fred Saunders, Jacek Zaucha, Magdalena Matczak, Ignė Stalmokaitė, Michael Gilek, and Jakub Turski. 2023. “Blue Justice through and beyond Equity and Participation: A Critical Reading of Capability-Based Recognitional Justice in Poland’s Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09640568.2023.2183823.

- Tafon, Ralph V. 2019b. “Small-Scale Fishers as Allies or Opponents? Unlocking Looming Tensions and Potential Exclusions in Poland’s Marine Spatial Planning.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (6): 637–648. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1661235.

- Yet, Maggie, Patricia Manuel, Monica DeVidi, and Bertrum H. MacDonald. 2022. “Learning from Experience: Lessons from Community-Based Engagement for Improving Participatory Marine Spatial Planning.” Planning Practice & Research 37 (2): 189–212. doi:10.1080/02697459.2021.2017101.

- Zuercher, Rachel, Nicole Motzer, Rafael A. Magris, and Wesley Flannery. 2022. “Narrowing the Gap between Marine Spatial Planning Aspirations and Realities.” ICES Journal of Marine Science 79 (3): 600–608. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsac009.