Abstract

This introduction connects some of the main themes covered in this special issue on Chancellor Merkel's second coalition cabinet, which was formed in October 2009 and ended with the electoral collapse of the FDP in the Bundestag election of September 2013. It starts by setting out an interesting ‘puzzle’: the parties forming the coalition of 2009–2013 (CDU, CSU and FDP) had expressed a strong preference for this coalition in the run-up to the election of 2009. Despite their seeming agreement in many policy areas, the coalition formed in 2009 faced tough negotiations and conflicts between the parties from the beginning. The economic crisis the preceding government faced between 2005 and 2009 and unforeseen events during the course of the CDU/CSU–FDP coalition 2009–2013 (e.g. the Euro crisis and the Fukushima environmental disaster) had altered the policy agenda in important ways and rendered the former ‘Christian–Liberal reform project’ obsolete.

INTRODUCTION

In the run-up to the Bundestag election of 2009, both Christian Democrats (CDU and CSU) and Liberals (FDP) expressed a clear preference for a centre–right coalition with one another. Such a coalition was seen as a return to the ‘normality’ of the dominant pattern of coalition formation in Germany since 1949. After all, CDU, CSU and FDP had been almost ‘natural’ partners right of the political centre except in the period between the late 1960s and early 1980s. The Grand Coalition the CDU/CSU formed with the SPD after the election of September 2005 had not been their preferred coalition. Christian Democrats and Liberals were in broad agreement in economic and budgetary policies as well as foreign affairs. In addition, the Grand Coalition was ‘costly’ for the Christian Democrats in terms of ministerial offices. The coalition they formed with the Social Democrats in 2005 had been an arithmetic necessity arising from the election result: CDU/CSU and FDP simply had not won a sufficient number of seats in the Bundestag to replace the ‘red–green’ coalition of Social Democrats and Greens under Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (SPD). The Christian Democrats could only take over the helm of government by forming a coalition with the ruling Social Democrats, although they were able to secure the chancellorship for their leader, Angela Merkel. For the first time since 1998, the election of 2009 presented both CDU/CSU and FDP with the long-awaited opportunity to form their preferred coalition, largely due to the Liberals' strong electoral performance. Despite the perceived broad agreement on policy and a relatively swift agreement, the coalition negotiations between the two parties in 2009 were surprisingly tough.Footnote1 Many contentious issues could not be resolved in explicit compromises. Rather, the formulation of specific policies had to be postponed to the time after Angela Merkel's election to Federal Chancellor. The Christian–Liberal ‘project’ of economic reforms – a project that had emerged in 2002/03 but was perceived to have been slowed down during the Grand Coalition of 2005–09 – was quickly superseded by the exogenous constraints arising from the Euro crisis. At the end of the 2009–13 legislative term, the Christian Democrats – and especially the Federal Chancellor – were rewarded for their seemingly successful crisis management in Europe, and for a moderate programme of modernisation in a number of policy areas, which moved the CDU/CSU closer to the SPD in many respects while it disappointed many of the FDP's voters. As a result, the FDP failed to clear the 5 per cent hurdle of Germany's electoral system and was not represented in the German Bundestag after the 2013 election. The contributions to this volume will deal with this puzzle from a variety of angles, partly from the perspective of the study of parties and elections, partly from the vantage point of public policy analysis.

In this Introduction, we will lay some foundations for this volume. We will start by examining the extent to which there was, in fact, far-reaching policy agreement between the CDU/CSU and the FDP in the 2009–13 Bundestag, in other words, whether it is justified to speak of a common ‘project’ of the two parties. After that we will shed some light on the starting conditions for the coalition in the autumn of 2009. This will be followed by a brief analysis of the coalition negotiations and the resulting agreement before we move on to summarise some of the key challenges the government faced between 2009 and 2013.

A ‘CHRISTIAN–LIBERAL REFORM PROJECT’? POLICY AGREEMENTS AND DISAGREEMENTS

After the defeat of the centre–right ‘bloc’ in the Bundestag election of 2002, something that might be referred to as a ‘Christian–Liberal’ (i.e. CDU/CSU–FDP) project of far-reaching economic and welfare reforms seemed to be evolving. Much evidence points to the conclusion, however, that the economic conditions and the CDU/CSU's strategy had changed by the time the ‘Christian–Liberal’ coalition of CDU/CSU and FDP actually assumed office in 2009. Thus, by the time the coalition Merkel–WesterwelleFootnote2 took office, the project was already out of date. Especially the FDP failed to respond to these changes appropriately.

After the narrow re-election of Gerhard Schröder's ‘red–green’ coalition in 2002, the CDU made an effort to strengthen its profile in economic policy and in relation to welfare reforms by putting a stronger emphasis on market elements.Footnote3 This partial reorientation culminated in the resolutions of the CDU's Leipzig Annual Conference in December 2003, where the party decided to push for far-reaching reforms both in tax and health policy.Footnote4 In health policy, the CDU proposed a new system based on a flat-rate, income-independent per capita premium, a freezing of the employers' contributions and some compensation for people on low incomes and children.Footnote5 The tax reform envisioned by the Christian Democrats was based on proposals of the then deputy leader of the CDU/CSU parliamentary party in the Bundestag, Friedrich Merz. The reform proposal included a simplified income-tax system with only three tax rates at 12, 24 and 36 per cent. This new tax scale would in turn have reduced the top income tax rate from 42 to 36 per cent. This amounted to a significant reduction in income tax which was to be funded by the reduction of tax exemptions and loopholes.

Although resistance in the CSU prevented these ideas from being incorporated into the CDU/CSU's manifesto for 2005, the document did include a general commitment to the introduction of an income-independent system of health-insurance premiums and a reduction of income tax. In addition, the two Christian parties – who have always run with a joint manifesto in national elections – agreed on proposals for a liberalisation of labour laws and the extension of the licensed run-time of nuclear-power stations. Moreover, Merkel appointed the former constitutional court judge Paul Kirchhof to her team with responsibility for financial policy, which was generally seen as a further signal for a strong commitment to economic liberalisation.

This adjustment of the CDU's economic policy increased the commonalities with the FDP, which advocated similar, if frequently more far-reaching policies.Footnote6 Given the overwhelming importance of economic policy in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the fact that the parties' policy positions were much less congruent in other areas such as home affairs and justice did not seem to create significant obstacles to a relatively harmonious collaboration. Thus, liberal economic and welfare policies could be seen as the core of a Christian–Liberal reform project.

Instead of a detailed and comprehensive qualitative analysis of the programmatic similarities and differences between the CDU/CSU and the FDP in the run-up to the coalition formed in 2009, and are designed to provide a summary indicator for the areas of economic and social policy on the one hand and home, justice and societal affairs on the other. The relevant parts of the parties' election manifestos were analysed using Wordfish to estimate policy positions for these two areas.Footnote7 shows for the election manifestos of both the CDU/CSU and the FDP a moderate but clearly discernible move from the political centre towards a more market-oriented position. This development was almost parallel between 1998 and 2005, although the FDP's move towards a more market-oriented position was even more pronounced than was the case for the Christian Democrats. In questions of home affairs, justice and social-liberal values, the FDP's manifesto of 2005 opened up a growing gap in relation to the CDU/CSU. Thus, the differences in aggregated policy preferences in this area were larger in 2005 than before or after this election.

FIGURE 1 ESTIMATES OF THE MAIN PARTIES' POLICY POSITIONS IN THEIR ELECTION MANIFESTOS, 1994–2013: ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL WELFARE

Source: M. Hornsteiner and T. Saalfeld, ‘Parties and Party System’, in S. Padgett, W.E. Paterson and R. Zohlnhöfer (eds), Developments in German Politics 4 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p.96.

FIGURE 2 ESTIMATES OF THE MAIN PARTIES' POLICY POSITIONS IN THEIR ELECTION MANIFESTOS, 1994–2013: SOCIETAL VALUES, HOME AFFAIRS AND JUSTICE

Source: Hornsteiner and Saalfeld, ‘Parties and Party System’, p.96.

In short, prior to the election of 2005, the ideological proximity of Christian Democrats and Liberals in the areas of economic and welfare policies seems to have provided favourable conditions for a Christian–Liberal reform project.Footnote8 Nevertheless, the centre–right parties failed to convince a sufficiently large number of voters to provide them with a majority in the Bundestag – despite the strong lead they had had in the opinion polls in the run-up to the election of 2005. Hence, the Christian Democrats did not get the chance to realise the Christian–Liberal reform programme outright. Rather, they had to contend with a coalition with the Social Democrats. When the CDU/CSU and the FDP were eventually able to form a coalition in 2009, the starting conditions for this government were already strongly shaped by its predecessor, the Grand Coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats. This will be discussed in the following section.

BACKGROUND CONDITIONS FOR THE 2009–13 GOVERNMENT

Despite the fact – or perhaps even because – the SPD had pushed through far-reaching reforms in economic and welfare policies in the second ‘red–green’ coalition under Chancellor Schröder and the Green Party leader Joschka Fischer between 2002 and 2005, the SPD leadership was not in a position to support the even more far-reaching ideas the Christian Democrats had committed to at their Leipzig Conference. Too strong had been the backlash within the SPD and in the electorate. Thus, most of the more radical aims of the CDU's Leipzig Annual Conference – from the liberalisation of employment protection legislation to the extension of the life span of German nuclear power stations – could not be achieved between 2005 and 2009. The only reforms under the Grand Coalition that reflected the ambition of the Leipzig resolutions were the increase of the statutory pension age to 67 years and the reform of corporate taxation with a marked reduction of business tax. In addition, the CDU/CSU was able to achieve an increase in value-added tax, which allowed it to make some progress in fiscal consolidation and to fund some reductions in social insurance contributions. The reform of the financing of statutory health insurance did not make a great deal of progress, although some seemingly minor reforms paved the way for greater changes in the future.Footnote9 Therefore, the core elements of the Christian–Liberal reform project had not been realised by 2009. Thus, the new coalition of the CDU/CSU and the FDP could have been expected to develop a clearly defined programme and carry it through, especially as the balance of votes in the Bundesrat was still favourable in 2009.

However, the economic conditions in 2009 were strikingly different from those in 2005. While German voters in 2005 had been stunned by the fact that the number of unemployed had increased to over five million persons for the first time in the Federal Republic's history and that the government had breached the fiscal deficit criteria enshrined in the EU's Stability and Growth Pact, the economic situation had improved substantially by the autumn of 2008. This could partly be interpreted as a success of the reforms of the ‘red–green’ coalition of 1998–2005 (especially 2002–2005). More importantly, however, it reduced the problem load in economic policy substantially.

However, this upturn ended with the start of the global financial crisis in the autumn of 2008, which led to the largest drop in Gross National Product in the history of the Federal Republic. Although economic problems thus dominated the agenda in 2009 to the same extent as in 2005, there were remarkable differences: on the one hand, the economic crisis of 2008/09 was widely seen as being triggered by external factors such as the collapse of the United States housing market. Therefore, the Grand Coalition was not blamed for the crisis. On the contrary, its economic management in times of extreme adversity was seen as relatively successful.Footnote10 On the other hand, the sense of urgency was reduced even further by the fact that most of the Federal Republic's economic performance indicators at the time seemed more favourable than those of most other comparable western democracies. All in all, therefore, pressure for root-and-branch economic or welfare reforms was low, although fiscal consolidation after the crisis was an important issue given the enormous sums that needed to be provided to underwrite the saving of German banks and to boost the economy.Footnote11

In addition to the policy decisions of the Grand Coalition of 2005–09, which constituted the ‘policy status quo’ for the incoming CDU/CSU–FDP coalition of 2009 in the parlance of veto-player theory, any analysis of Merkel's second cabinet needs to account for the main parties' strategic development. Before the Bundestag election of 2009, the CDU/CSU and the FDP leaderships appeared to behave ‘rationally’ in the sense of normative prescriptions of formal theories. As the largest party in the German party system (in terms of voters), the Christian Democrats opted for a DownsianFootnote12 strategy of pursuing the median voter – or of a ‘catch-all party’ in Kirchheimer'sFootnote13 terms. Although the extent of this strategy is subject to some discussion in the literature, many authors claim that the CDU had begun a cautious programmatic modernisation under Merkel's leadership since 2005.Footnote14 As a result, it was argued, the CDU had moved to the political centre. To some extent, this can be seen in the lines in and where the CDU/CSU moved to the centre in economic and welfare policies and, to a much lesser extent, in the area of home affairs, justice and societal values. This may have partially been a result of the programmatic reforms of the CDU under Merkel and the influence of the ‘Christian–social’ credentials of the CSU leader and Bavarian State Minister President, Horst Seehofer. Whatever the trigger for these developments, the – moderate – responses of conservative forces in the Christian Democratic parties by state leaders such as the former Hessian Minister President, Roland Koch, and his Baden-Württemberg counterpart, Stefan Mappus, demonstrate that they were also debated in the ‘real world’ of intra-party politics.

While the CDU/CSU seemed to have leaned towards a median-voter strategy, the FDP's strategy would be described more aptly as one of a ‘niche party’ in the terminology of Adams and his co-authors.Footnote15 According to the studies of Adams et al.,Footnote16 MeguidFootnote17 and Spoon,Footnote18 the competition between ideologically adjacent smaller and larger parties is often characterised by a particular dynamic: not only does the political survival of small parties depend on their own electoral strategies, but also those of their larger ideological ‘neighbours'. In her analysis of British and French Green parties Spoon, for example, found that small parties can survive in the shadow of ideologically similar larger parties, if they maintain a certain ideological distinction from the larger parties without allowing the distance to grow too much. The data in and are compatible with the hypothesis that the FDP pursued such a strategy of limited competition between 2005 and 2009. In their economic and welfare policies the FDP consistently pursued a more market-oriented position than the CDU/CSU without moving too far from the Christian Democrats. In questions of home affairs, justice and societal values the party moved towards the position of the Greens and the Left Party, displaying a much stronger conflict with the CDU, the CSU and the SPD in these policy areas. It is important to distinguish between a party's position in a ‘policy space’ (e.g. in social issues) and the ‘salience’ of the relevant issue. Since the coalition of the CDU/CSU and the FDP had lost power in 1998, the FDP's strategy was strongly shaped by its appearance as a party promoting lower taxes. In this context, it pursued a confrontational course vis-à-vis all other parties, including the CDU/CSU in the Grand Coalition of 2005–09. By comparison, the relatively clear differences between the FDP and the CDU/CSU in questions of home affairs, justice, civil liberties and societal values was generally seen as less ‘important’ in the parties' competition for voters in Germany's multi-dimensional policy space.

Thus, the programmatic developments of both the CDU/CSU and the FDP add up to a co-ordinated strategy. Jesse, for example, constructs a plausible argument to suggest that Merkel made the CDU more attractive for less committed, centrist voters, and that this move opened up space for the CSU and the FDP to capture the more conservative and economically liberal vote. This, he argues, was consistent with a strategy to transform the zero-sum game between the centre–right parties in 2002 and 2005 (where voters mainly moved between these parties) into a positive-sum game in 2009, which made it possible to reach out to voters beyond the traditional clientele of the CDU/CSU and the FDP. From the Christian Democrats' perspective, this strategy bore fruit in 2013 only. In 2009, the FDP seemed to have benefited from this strategy, while the CDU/CSU's election result was almost as disappointing as in 2005. This strengthening of the FDP combined with the relatively weak performance of the CDU/CSU was to influence the atmosphere of the coalition negotiations in 2009 pitching a confident FDP against a defensive CDU/CSU.Footnote19

CONSENSUS AND DISSENSUS DURING THE COALITION NEGOTIATIONS 2009

The negotiations between the CDU, the CSU and the FDP to form a coalition government in 2009 were partly influenced by the fact that the centre–right majority was made possible through the spectacular electoral gains of the FDP. At the same time, however, the CDU/CSU had a strategically favourable position in the party system as far as the policy dimension ‘economic policy and social welfare’ is concerned. On this dimension, which was by far the most salient dimension of party conflict, the Christian Democrats had the position of a ‘strong’ party in Laver and Shepsle's terms.Footnote20 The CDU/CSU, not the relatively extreme FDP, controlled the legislative median in this central policy dimension. And the Christian Democrats, not the FDP, had a number of theoretical alternatives to the Christian–Liberal coalition that both sides wanted.

Moreover, the focus on economic policy and particularly on taxation had introduced a strong element of competition among the centre–right parties from the start of the coalition negotiations. Although the negotiations of 2009 allowed agreement on a number of smaller package deals,Footnote21 the area of tax policy constituted a battleground during the negotiations with the FDP demanding comprehensive tax cuts and the CDU/CSU insisting on fiscal consolidation as a priority. The outcome of the negotiations was much closer to the CDU/CSU's than to the FDP's position. Most compromises were vague. Most importantly, the Finance Minister's veto over all government expenditure and income was written into the coalition agreement. Concessions to the FDP, especially the reduction of value-added tax for hotels, damaged the FDP's public image. It turned out problematic that there was no second policy area of similar salience for the FDP where ‘complementary’ or ‘tangential’ compromisesFootnote22 could be achieved with the CDU/CSU, that is, a type of logrolling, or an agreement across a number of policy dimensions utilising variations in the salience of different issues for the parties involved in the negotiations. In questions of home affairs, justice and socio-cultural issues – an area where the FDP still had a very distinctive position vis-à-vis the Christian Democrats in 2005 – the Liberals had moved towards the Christian Democratic parties, and these issues did not play a very strong role for the FDP's ‘brand’ of 2009. The FDP ‘brand’ in the 2009 election campaign had been clearly defined by tax policy.Footnote23

Taken in its totality, the agreement of 2009 demonstrated considerable potential for conflict between the coalition partners, not least in tax and health-care policies, the core ingredients of the Christian–Liberal reform project of the first half of the 2000s. It was no longer possible to speak of a common project when the coalition led by Merkel and the FDP chairman Guido Westerwelle took office in 2009.Footnote24

The strategic literature on party competition and coalitions demonstrates that ideological proximity between coalition partners can be a double-edged sword. Even so-called ‘projects', that is, clearly defined policy goals shared by the coalition partners and a certain ideological proximity in these policy areas do not necessarily suspend competition in these areas.Footnote25 The coalition negotiations of 2009 and the experience of the CDU/CSU–FDP coalition of 2009–13 confirm the risks for niche parties highlighted by Adams and his co-authors.Footnote26 Smaller niche parties can only be successful in the long run, if they develop a clear ideological profile vis-à-vis ideologically close larger parties. Therefore, they often position themselves more extremely than the larger parties. In this case, however, niche parties run the risk of becoming ‘prisoners' of their ideology or strategy, if they lose the necessary responsiveness vis-à-vis voter preferences. While the FDP arguably had benefitted from its relatively aggressive tax policy during the election campaign of 2009, it became a prisoner of this position in the CDU/CSU–FDP government of 2009–13. It had staked its credibility on the delivery of significant tax reductions in office. Once in office the Liberals did not have the clout (and portfolio, namely the finance portfolio) to fulfil its pledges. Beyond personal idiosyncrasies, the problems of the cabinet Merkel II could be partly seen to result from this dilemma. The FDP leadership was clearly emboldened by a very good election result, which it saw as the result of a clear, radical profile in tax policy. This profile was rewarded by the voters. But these new FDP voters expected the party to deliver on the pledges it had made using a very robust and competitive oppositional strategy between 2005 and 2009. However, the Liberals did poorly during the coalition negotiations. Their leaders, inexperienced in government, found it difficult to switch from an oppositional to a governmental role. This peculiar competitive situation within the centre–right bloc thus impeded the formulation of a shared reform project from the outset and, in turn, also complicated consensus building in the coalition negotiations.

GOVERNING IN THE SHADOW OF CRISIS

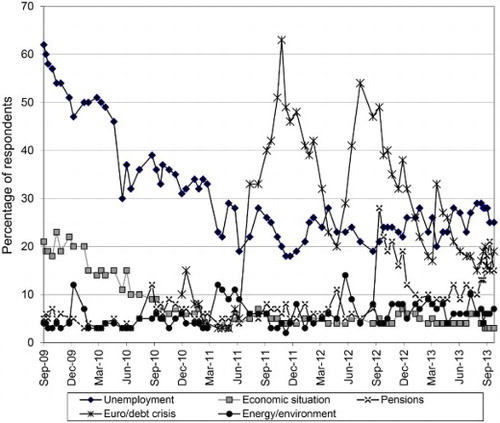

Coalition negotiations are strongly shaped by the information coalition leaders have at the time of the talks. Yet, coalition agreements are inevitably incomplete contracts, because in the post-negotiation phase the governments established as a result of these negotiations usually face unanticipated developments in the policy environment. The second Merkel government (2009–13) is a very good case in point. The government's policy options were strongly constrained by a number of crises that began to emerge after its formation. This is illustrated by , which summarises data of a regular representative poll of Forschungsgruppe Wahlen where respondents are asked to identify the most important policy problems facing Germany. At the beginning of the Christian–Liberal coalition in 2009, the effects of the global financial crisis and concerns about Germany's economic performance clearly dominated public perceptions. These items' importance declined in the second half of 2010 and remained at a low level until the end of the 2009–13 Bundestag election period – which is remarkable in the case of the item economic performance given the evolving Euro crisis.

FIGURE 3 POPULAR PERCEPTIONS OF THE MOST IMPORTANT POLICY PROBLEMS IN GERMANY, SEPTEMBER 2009 TO SEPTEMBER 2013 (SELECTION)

Although the crisis of the European currency surfaced in December 2009 with the downgrading of Greece's credit rating,Footnote27 the Euro crisis developed a strong resonance in public opinion only in the autumn of 2010. By the summer of 2011, it had climbed to the position of the most important political problem. It remained the most important problem in the voters' as well as the elite's perceptions until the end of the legislative term in September 2013. This is not surprising given the considerable uncertainty about the causes of the crisisFootnote28 and, in particular, of the most appropriate policy options including the anticipated and unanticipated economic and political consequences of any response. Potentially, huge sums of German taxpayers' money were at stake. At the same time, a failure to respond effectively could have put the common European currency and, as Chancellor Merkel argued, the entire process of European integration at risk – involving costs that could have potentially even exceeded the funds made available to underwrite bad government debt in a number of EU member states. This balancing act between saving the Euro and protecting German interests (by ensuring that the costs of the economic adjustment processes were born by the states in the European periphery) dominated the government's policy agenda for the entire period 2009–13.Footnote29 Given the magnitude of the task and the scope of decisions that were generally not welcomed enthusiastically by the German voters, the Federal Chancellor, Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU) and other key actors in the coalition had to use their entire political capital to persuade the public to support the government's policy.

In comparison, the reverberations of the environmental catastrophe in the Japanese nuclear power station Fukushima-Daiichi on 11 March 2011 were relatively moderate. Although Germany was not affected by the environmental catastrophe directly, environmental and energy policy became one of the most salient political problems in Germany for a few weeks after the accident. Again, the CDU/CSU–FDP coalition took far-reaching decisions with potentially very high costs for consumers and taxpayers, including a complete u-turn in the government's policy towards extending the run-time of nuclear power stations.Footnote30 In the context of this unanticipated policy of an accelerated withdrawal from nuclear power, the government had to expend a significant amount of political capital which it lacked in other areas as a result.

In addition, smaller crises with fewer reverberations in the opinion polls forced the second Merkel cabinet to make hard choices it would have preferred to avoid. In Germany's external affairs the events surrounding the ‘Arab Spring’ led to the downfall of a number of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. At the same time it triggered civil wars in some countries such as Libya and Syria, which forced the federal government to consider questions of German support for military intervention. Especially in the case of Libya this caused significant political problems for the government in relation to its external allies.

In the area of home affairs and justice the events not anticipated during the coalition negotiations included a number of rulings of the Federal Constitutional Court; the discovery of the shocking murders of 10 persons, predominantly Turkish immigrants, by the extreme right-wing terrorist group NSU (National Socialist Underground)Footnote31 over a number of years; and the fallout from the revelations about the extent of surveillance by US agencies.

While all of these unexpected developments provided a very challenging policy environment, the Chancellor and her party seemed to benefit from these developments. The crisis management in the context of the Euro crisis was attributed to the Chancellor and her Finance Minister. This boosted the Christian Democrats' poll ratings, while the FDP failed to benefit from it.Footnote32 According to critics, the Chancellor had perfected her strategy of ‘asymmetric demobilisation’ and succeeded in presenting herself as a pragmatic, politically moderate problem-solver who was above narrow party-political quarrels and took competent decisions in a policy environment characterised by tight constraints and few attractive choices. The Chancellor succeeded, so the argument goes, to present herself, as well as her policies, as being without real alternatives. The SPD as the main opposition party faced a serious dilemma in this situation. It could not help but to support many of the key decisions in the area of EU policy.Footnote33 The party's dilemma, resulting partly from Merkel's strategy, became particularly evident when it nominated Peer Steinbrück to run as Merkel's challenger and the Social Democrats' candidate for the chancellorship in 2013. Although the party had moved to the left after the Schröder years (see and ), it nominated Steinbrück as a leading proponent of Chancellor Schröder's (1998–2005) policies of welfare cuts and the Finance Minister of the Grand Coalition under Merkel between 2005 and 2009.

The rise and fall of various small parties during the17th Bundestag's legislative period (2009–13)Footnote34 demonstrated how opposition parties could be partially successful in specific policy areas.Footnote35 In the shadow of the Fukushima reactor accident, the Green Party temporarily managed to increase its electoral support to such an extent that it was temporarily seen as a party that could compete for the second rank in the German party system after the Christian Democrats. In 2011, the Berlin government parties' annus horibilis, it managed to capture the prize of State Minister President in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg.

The Pirates Party gained considerable, if unsustainable, electoral support as a left-libertarian protest party with a strong emphasis on grass-roots participation. This support was largely based on the party's policies regarding access to the internet, data protection and copyright. It succeeded in overcoming the 5 per cent hurdle in a number of regional elections and entered the state assemblies of Berlin, Northrhine-Westfalia, Saarland and Schleswig-Holstein.

Finally, the Eurosceptic, conservative-national AfD (Alternative for Germany),Footnote36 founded only in February 2013, narrowly missed its target of 5 per cent of the national vote in the Bundestag election of September 2013, a figure that would have guaranteed it proportional representation in the German parliament. The AfD's gains contributed to the FDP's failure to clear the 5 per cent hurdle in the 2013 Bundestag election and the end of the Christian–Liberal reform project for the foreseeable future. Anticipating the Liberals' crisis, the Chancellor and CDU politicians close to her had started during the 2009–13 legislative period to remove obstacles for a future cooperation with the SPD (e.g. by supporting a statutory minimum wage) and the Greens (by accelerating the complete phasing out of nuclear energy).

CONCLUSIONS

This introductory contribution argued that there was something akin to a Christian–Liberal political project in economic and social policy during the first half of the 2000s. In a nutshell, this project consisted of a moderate reduction of the role of the state and a stronger emphasis on people's self-reliance. Although the ‘red–green’ coalition of the SPD and the Greens between 1998 and 2005 had initiated a large number of liberalising reforms, it did not satisfy core elements of the CDU/CSU–FDP ‘project’, namely a root-and-branch reform of taxation and of the funding of health care in Germany. The Grand Coalition of the CDU/CSU and the SPD, which followed the ‘red–green’ coalitions under Chancellor Schröder, did not make much headway with regard to these more ambitious elements of the Christian–Liberal reform project between 2005 and 2009.

We also argued that by 2009 the agenda of dominant policy problems and issues had shifted considerably. The performance of the German economy had improved at least until 2008; unemployment and the fiscal deficit were reduced. And the severe financial and economic crisis of 2009 was not attributed to domestic policy gridlock (‘Reformstau’). Against the backdrop of this changed policy environment, the leaders of the CDU/CSU–FDP coalition, which until election day 2009 seemed to be the harmonious ‘dream team’ of German politics, found it difficult to overcome policy differences even during the coalition negotiations in the autumn of 2009. This problem was strongly exacerbated by the fact that the second Merkel cabinet had to face crises whose extent could not be anticipated during the coalition negotiations. The Euro crisis is the most obvious, but not the only example. Throughout the 2009–13 legislative period, these challenges largely absorbed the attention of the main actors and forced the coalition to expend much of its political capital in dealing with these crises. The consequences of this situation, a government in the shadow of multiple crises, both for the political actors themselves and policy reforms in a number of areas are the topic of the following contributions to this volume.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Thomas Saalfeld is Professor of Political Science at the University of Bamberg and the founding Director of the Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences (BAGSS), an institution funded under the German Excellence Initiative. Before joining the University of Bamberg he was Professor of Political Science at the University of Kent (Canterbury, UK). He also held visiting professorships at Boğaziçi University Istanbul, the Institut d’Études Politiques de Lille and the University of Mannheim. Professor Saalfeld is Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences (AcSS) and member of the Advisory Board of the Italian Political Science Review. His research focuses on representation, legislative behaviour, parliamentary accountability and coalition government in European democracies. His work was published in academic journals including the European Journal of Political Research, International Studies Quarterly, the Journal of Legislative Studies, the Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, Parliamentary Affairs and West European Politics. His most recent publications include The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies (jointly edited with Shane Martin and Kaare Strøm, 2014) and The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities (jointly edited with Karen Bird and Andreas M. Wüst, 2011).

Reimut Zohlnhöfer is Professor of Political Science at Ruprecht-Karls-University, Heidelberg, Germany. In 2001, Prof. Zohlnhöfer received his PhD from the University of Bremen where he also worked at the Center for Social Policy Research. He spent his postdoctoral years at the Political Science Department at Ruprecht-Karls-University, Heidelberg, and at the Center for European Studies at Harvard University. From 2008 to 2011 he was professor of comparative public policy at the University of Bamberg before returning to Heidelberg. His research focuses on economic policy and the welfare state in Germany as well as in comparative perspective with a focus on the OECD countries. He has published and edited numerous books and special issues of academic journals, most recently Developments in German Politics 4 (Palgrave 2014, co-edited with Stephen Padgett and William Paterson). Furthermore, he has published articles in many leading journals, including Comparative Political Studies, Journal of European Public Policy, Governance, West European Politics and others.

Notes

1. T. Saalfeld, ‘Regierungsbildung 2009: Merkel II und ein höchst unvollständiger Koalitionsvertrag’, Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 41/1 (2010), pp.181–206.

2. Named after the Chancellor and the FDP leader of 2009, Guido Westerwelle, who was replaced as FDP leader by Philip Rösler in 2011.

3. R. Zohlnhöfer, ‘Eine zu spät gekommene Koalition? Die Bilanz der wirtschafts- und sozialpolitischen Reformtätigkeit der zweiten Regierung Merkel’, in E. Jesse and R. Sturm (eds), Bilanz der Bundestagswahl 2013 – Voraussetzungen, Ergebnisse, Folgen (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2014), pp.477–93.

4. See R. Zohlnhöfer, ‘Zwischen Kooperation und Verweigerung: Die Entwicklung des Parteienwettbewerbs 2002–2005’, in C. Egle and R. Zohlnhöfer (eds), Ende des rot-grünen Projekts: Eine Bilanz der Regierung Schröder 2002–2005 (Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007), pp.124–50; U. Zolleis and J. Bartz, ‘Die CDU in der Großen Koalition – Unbestimmt erfolgreich’, in C. Egle and R. Zohlnhöfer (eds), Die zweite Große Koalition: Eine Bilanz der Regierung Merkel, 2005–2009 (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010), pp.51–68.

5. A. Hartmann, ‘Die Gesundheitsreform der Großen Koalition: Kleinster gemeinsamer Nenner oder offenes Hintertürchen?’, in Egle and Zohlnhöfer (eds), Die zweite Große Koalition, pp.331–2.

6. H. Vorländer, ‘Partei der Paradoxien: Die FDP nach der Bundestagswahl 2005’, in O. Niedermayer (ed.), Die Parteien nach der Bundestagswahl (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008), p.143.

7. For more detailed information see M. Hornsteiner and T. Saalfeld, ‘Parties and the Party System’, in S. Padgett, W.E. Paterson and R. Zohlnhöfer (eds), Developments in German Politics 4 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp.96–7.

8. See also E. Jesse, ‘Schwarz-Gelb – Vergangenheit, Gegenwart, aber Zukunft?’, in F. Decker and E. Jesse (eds), Die deutsche Koalitionsdemokratie vor der Bundestagswahl 2013 (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2013), pp.323–47.

9. Hartmann, ‘Die Gesundheitsreform’, p.336; for more detail on the reforms of the Grand Coalition in general see R. Zohlnhöfer, ‘New Possibilities or Permanent Gridlock? The Policies and Politics of the Grand Coalition’, in S. Bolgherini and F. Grotz (eds), Germany after the Grand Coalition: Governance and Politics in a Turbulent Environment (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp.15–30; and the contributions to Egle and Zohlnhöfer (eds), Die zweite Große Koalition.

10. See R. Zohlnhöfer, ‘The 2009 Federal Election and the Economic Crisis', German Politics 20/1 (2011), pp.12–27.

11. See H. Enderlein, ‘Finanzkrise und große Koalition: Eine Bewertung des Krisenmanagements der Bundesregierung’, in Egle and Zohlnhöfer (eds), Die zweite Große Koalition, pp.234–53; Zohlnhöfer, ‘The 2009 Federal Election’.

12. A. Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1957).

13. O. Kirchheimer, ‘The Transformation of the Western European Party Systems’, in J. LaPalombara and M. Weiner (eds), Political Parties and Political Development (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966), pp.177–200.

14. See, for example, S. Green, ‘Societal Transformation and Programmatic Change in the CDU’, German Politics 22/1–2 (2013), pp.46–63.

15. J. Adams, M. Clark, L. Ezrow and G. Glasgow, ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and the Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties' Policy Shifts, 1976–1998’, American Journal of Political Science 50/3 (2006), pp.513–29. For a slightly different interpretation of the concept of ‘niche party’ see B.M. Meguid, Party Competition between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

16. Adams et al., ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different’.

17. Meguid, Party Competition.

18. J.-J. Spoon, Political Survival of Small Parties in Europe (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011).

19. Jesse, ‘Schwarz-Gelb’.

20. M. Laver and K. Shepsle, Making and Breaking Governments: Cabinets and Legislatures in Parliamentary Democracies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

21. See Saalfeld, ‘Regierungsbildung 2009’.

22. A. Falcó-Gimeno, ‘The Use of Control Mechanisms in Coalition Governments: The Role of Preference Tangentiality and Repeated Interactions', Party Politics 20/3 (2014), pp.341–56.

23. Saalfeld, ‘Regierungsbildung 2009’.

24. See also T. Grunden, ‘Ein schwarz-gelbes Projekt? Programm und Handlungsspielräume der christlich-liberalen Koalition’, in K.-R. Korte (ed.), Die Bundestagswahl 2009: Analysen der Wahl-, Parteien-, Kommunikations- und Regierungsforschung (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010), pp.345–70; K. von Beyme, ‘Die schwarz-gelbe Koalition als “Projekt”? Vergleiche mit den Regierungserklärungen von 1969, 1982 und 1998’, in E. Jesse and R. Sturm (eds), Superwahljahr 2011 und die Folgen (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2012), pp.175–90.

25. Jesse, ‘Schwarz-Gelb’.

26. Adams et al., ‘Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different’, p.526.

27. See H. Zimmermann's contribution to this volume.

28. More detail on this topic is provided by A. Johnston, B. Hancké and S. Pant, ‘Comparative Institutional Advantage in the European Sovereign Debt Crisis', Comparative Political Studies 47/13 (2014), pp.1771–1800.

29. For more details see F. Wendler's and H. Zimmermann's contributions to this volume.

30. See C. Huß's contribution to this volume.

31. In German: Nationalsozialistischer Untergrund.

32. See H. Schoen and R. Greszki's contribution to this volume.

33. See F. Wendler's contribution to this volume.

34. See the survey by O. Niedermayer, ‘Aufsteiger, Absteiger und ewig “Sonstige”: Klein- und Kleinstparteien bei der Bundestagswahl 2013’, Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 45/1 (2014), pp.73–93.

35. See also R. Zohlnhöfer and N. Engler's contribution to this volume.

36. In German: Alternative für Deutschland.