Abstract

This study examines how a government’s majority status affects coalition governance and performance. Two steps are investigated: the inclusion of government parties’ electoral pledges into the coalition agreement, and the ability to translate pledges into legislative outputs. The main results of a comparative analysis of 183 pledges of a minority (without a formal support partner) and majority coalition in the German State North Rhine-Westphalia indicate that government parties with minority status include fewer pledges in the coalition agreement. But this does not mean that they also perform badly at pledge fulfilment. In fact, they show an equivalent performance in fulfilling election pledges, at least partially, when compared to majority government parties. However, there is tentative evidence that the prime minister’s party shows a lower quality of pledge fulfilment, as measured by a higher share of partially enacted pledges.

INTRODUCTION

Political parties in Germany are used to forming stable coalitions that have a secure majority in parliament. This has been confirmed yet again after the recent German federal elections in 2017: instead of forming a minority government that would have been a viable alternative, the former government parties CDU/CSU and SPD agreed to revive the grand coalition, despite the social democratic party leader Martin Schulz repeating several times after the elections that his party would not join another. At the German state level, however, there is some precedent for minority governments: in Saxony Anhalt, the SPD twice formed a minority government that was tolerated by the Left Party (1994–98, 1998–2002), and in 2010 the Social Democrats and the Green Party joined a minority coalition in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). The latter especially attracted a lot of attention because it was a ‘real minority government’ and did not rely on a stable support partner. Consequently, it had to form alternating coalitions with changing support partners among the opposition parties. At face value, the red-green minority coalition formed in NRW confirms the previous held general belief that minority governments are unstable, weak and symbols of political crisis (Beyme Citation1970; Johnson Citation1975, 87; Steffani Citation1997). The minority government abruptly ended after two years of existence on 14 March 2012. The government parties failed as a result of lack of support for what is considered the most distinguished privilege in parliament: the budget. However, this is not necessarily informative about how the minority coalition performed during the time it was in office. This article studies the legislative work of this NRW-minority coalition in comparison to its preceding majority coalition at the party level. Do the minority and majority coalitions display equal performance?

This study contributes to the empirical and theoretical debate on minority government’s performance. With the pioneering work of Strøm (Citation1990), previous negative preconceptions of minority governments have largely been diminished. Strøm has argued that the formation of a government without a secure majority in parliament might be a rational choice for political parties, and found that minority governments work effectively in various countries such as Norway, where most governments have no majority in parliament. This has also been supported by other scholars, such as Mayhew (Citation2005) in relation to the United States and Conley (Citation2011) in relation to Canada. Crombez has suggested that ‘minority governments are signs of the largest party’s strength’ and not of its weakness, given that the government parties in question control the median legislator (Citation1996, 1). For a long time, empirical studies analysing a government’s performance in dependence of its majority status that go beyond a purely quantitative record of laws passed were absent. Building upon the normative concept of democratic promissory representation as proposed by Mansbridge (Citation2003), scholars from the Comparative Party Pledges Project (CPPP) have only recently analysed whether parties are able to successfully enact the policies that they had promised before elections to their voters. These findings suggest that minority governments, when compared to majority governments, are not at a disadvantage in translating their election pledges into policy output.

I draw on these previous studies on pledge fulfilment. The substantive research value of this article stems from the following three elements. First, it concentrates on the central arena of decision making, the parliament. Recent studies have investigated fulfilment while relying on various documents and sources external to parliament. In this study, pledge fulfilment is traced directly back to parliamentary party responsibility – and not to extra-parliamentary events or actors. Legislative enactments are the ultimate challenge for minority governments that have to find additional support in order to pass laws. Second, this article studies pledge fulfilment in coalitions and acknowledges that there is an intermediate stage: the agreement between the coalition partners. More than one third of West European governments are minority governments, and out of that a further one third are minority coalitions (Müller and Strøm Citation2003). Considering the double challenge involving majority building (intra-coalitional and legislative), minority coalitions make a compelling research topic.Footnote1 The study of minority coalitions can teach us how majority building and agreements between coalition partners operate in situations of large uncertainty. Third, while previous research has mostly focused on the national level, this study provides an analysis at the regional-state level and is thereby relevant to debates on federalism and multi-level governance. So far, pledge fulfilment at the regional level has been studied only in Canada (Pétry et al. Citation2015; Pétry and Duval Citation2015).

This article takes an explorative, theoretically guided stance and seeks to reveal more information about legislative performance of a minority coalition when compared to a majority coalition at two stages: the coalition agreement and the legislative output. For the first stage, I argue that minority government parties include fewer pledges in their coalition agreement in order to manage uncertainty and avoid failure. For the second stage, there are arguments both supporting and opposing that idea that minority and majority coalitions perform equally in terms of pledge fulfilment. Based on the pledges approach from the CPPP, who define pledges as ‘commitments in parties’ programmes to carry out certain policies’ (Thomson et al. Citation2017, 528),Footnote2 I have identified 183 electoral pledges on education, which is the most important policy field for regional governments. The results indicate that the minority governments parties studied include fewer pledges in their coalition agreement, but display the same performance in at least partially fulfilling election pledges within the available time of two years. There is also some suggestion that the quality of pledge fulfilment is lower for the minority government’s large coalition party, as measured by a higher share of only partially and not fully fulfilled pledges. These findings have major implications for understanding legislative effectiveness and political representation in times of high uncertainty in majority building in parliament (Strøm, Müller, and Bergman Citation2010).

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 elaborates on the process of coalition governance and pledge fulfilment in minority coalitions and formulates working hypotheses that guide the analysis. Section 3 describes the methods and introduces the data and selected cases. Section 4 presents the empirical results concerning the two stages: the support of a pledge in the coalition agreement and its legislative enactment depending on a government’s majority status by balancing quantitative and qualitative presentations of the data. The final section summarises the results, infers implications, and suggests where further research is needed.

COALITION GOVERNANCE AND PLEDGE FULFILMENT OF MINORITY AND MAJORITY COALITIONS

Before elaborating more thoroughly on the role that a government’s majority status might exert on coalition governance and pledge fulfilment, it is necessary to clarify how substantive minority coalitions, as the type of government that this study is interested in, are defined. Substantive minority coalitions are governments that are composed of at least two parties, lack a majority in parliament and do not have a stable support partner, and as such can form legislative coalitions with different support partners. In contrast, the functioning of minority governments with stable support is often very similar to majority governments, and consequently, they are also called ‘hidden majority governments’ (Strøm Citation1990, Citation1997, 56; Bale and Bergman Citation2006).

It is useful to think of two stages when considering pledge fulfilment of government parties in coalitions: the coalition agreement and the final policy output. The process of election pledge fulfilment of a single party majority government is straightforward: it can commit itself to a policy agenda before elections, and as soon as it is in office, it can enact the policies listed in its electoral programme – with the condition that there are no other veto players. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the highest rates of pledge fulfilment are found in countries with single-party governments, such as the UK. In countries where coalition governments are usually formed, such as Germany or the Netherlands, the rate of fulfilled pledges is much lower (Thomson et al. Citation2017). Since coalition partners have to agree on a common agenda, they cannot directly enact what they have individually promised before elections. Usually, the agreement on this common agenda takes place before they enter government, and the coalition agreement represents this inter-party agreement. I consider these two stages – the coalition agreement and the final policy output – when looking at pledge fulfilment of government parties in coalitions with two different majority statuses. At which of these two stages does a government’s majority status have an effect?

Transferring Election Pledges Into the Coalition Agreement

Before election pledges are enacted, they have to go through an intra-coalitional filter: the coalition agreement. According to models of coalition theory and cabinet governance, coalition agreements are key elements of mutual control between parties in a coalition. Drafting a coalition agreement is an ex ante control instrument that prevents any shifting of the coalition partner from ever occurring, in particular in policy areas for which that partner controls the ministry. Once in power, there is an immediate risk that cabinet ministers act as agents of their own parties, rather than of the whole cabinet. From this perspective, the coalition agreement is a means to prevent agency problems. It represents a formal understanding between the coalition partners, who will keep tabs on each other and monitor compliance with the coalition treaty (Thies Citation2001; Müller and Strøm Citation2003; Kim and Loewenberg Citation2005; Strøm, Müller, and Smith Citation2010). If the coalition agreement is just a contract between the coalition partners in which the government parties agree on a common agenda after elections in order to prevent mutual shifts, there should be no difference between minority and majority coalitions when controlling for the ideological distance between parties.

However, there is serious doubt as to whether coalition agreements have an equal meaning for both minority and majority government parties. Christiansen and Pedersen (Citation2014) have argued and shown that for Denmark, majority governments’ coalition agreements largely pre-regulate policy outputs because they have high certainty and predictability. For substantive minority coalitions the empirical evidence is less clear, but they appear to have a tendency towards a ‘compromise-strategy’: laws that are passed during a minority coalition’s term are less likely to be pre-regulated in a coalition agreement. Coalition agreements of minority governments set the agenda of the parliament, but parts of the coalition partner’s policy proposals must still be renegotiated. Thus, if policies contained in coalition agreements have a lower chance of being translated into outputs, there is also reason to assume that the preceding drafting of a coalition agreement differs between government parties with and without a secure majority in parliament.

Drafting a coalition agreement comprises two steps: first, deciding whether to draft a coalition treaty, and second, setting the scope of this treaty (Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013, 826). Since the writing of coalition agreement is nowadays well established in Germany (Kim and Loewenberg Citation2005, 1110), and for the cases selected in this analysis coalition agreements have indeed been drafted, I concentrate on the second part of the decision, regarding the scope of the contracts.Footnote3 Of course, coalition agreements are always incomplete arrangements that do not pre-regulate all issues that the future government has to take care of because many events are not predictable (Müller and Strøm Citation2010, 177). However, when drafting a coalition agreement, there is a still a choice to be made by coalition partners on how extensive it should be.

Minority coalitions are in situations of great uncertainty: they must not only reach an intra-coalitional agreement after elections, but also rely on support of one or more opposition parties in parliament in order to form legislative coalitions. According to Indridason and Kristinsson (Citation2013), in situations of great uncertainty the desire to have as many issues stipulated as possible is very high, so coalition agreements from minority government parties should be more comprehensive. However, this prediction only considers that a minority government’s coalition agreement is more extensive when it has a stable support partner so that desired policies, not just from government parties but also from the support partner, are included in the coalition agreement. Nothing is said about the scope of a coalition agreement when a minority coalition builds ad hoc coalitions to pass laws.Footnote4 Drafting an extensive coalition agreement with many pre-regulations concerning legislation is a risky choice for substantial minority coalitions. The likelihood of failing to implement pre-formulated policies included in the coalition agreement is very high. Failure to implement promised policies reduces a government’s credibility from a voter’s perspective, and consequently might result in electoral loss, which explains why most parties have strong incentives to keep their pledges formulated in election and coalition programmes (Klingemann, Hofferbert, and Budge Citation1994; Aragonès, Postlewaite, and Palfrey Citation2007; Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013, 825; Eichorst Citation2014).Footnote5 Thus, when considering that government parties want to avoid failure, instead of pre-regulating as much as possible in the coalition agreement, minority government parties who have no stable support partner might instead act with restraint when drafting their coalition agreement.Footnote6 In addition, their coalition agreement sends signals to the opposition parties. A formulation of a coalition agreement of narrow scope with few pre-regulations implies an open negotiation-arena for all actors in parliament. When opposition parties are confronted with strongly pre-regulated policies, they might have little incentive to engage in discussions with minority governments parties (Strøm Citation1990). In accordance with this argument, minority coalitions would be expected to draft a coalition agreement of narrow scope. I call this ‘auto-limitation’: the government parties act with restraint when drafting the coalition agreement, even with regard to the inclusion of policies on which they agree upon. Consequently, I expect that the minority government parties are less likely to list their election pledges in the coalition agreement in comparison to the majority government parties.

H1 (auto-limitation): A minority government is less likely to include government parties’ election pledges in its coalition agreement, when compared to a majority government.

Translating Election Pledges Into Legislative Output

In relation to the second stage of pledge fulfilment, this study examines the legislative output produced by the minority and majority coalition. This means looking at whether each party’s election pledges have been legislatively enacted. The reasons for focusing on legislative enactments are that such regulations have higher democratic legitimation, are more sustainable, and compose more fundamental changes when compared to delegated legislation. Primary legislation is the ultimate challenge for minority governments because it requires approval by a majority in parliament, which in contrast is not necessary for delegated legislation. This means that minority government parties must find support partners among opposition parties in order to enact legislation in accordance with their preferred policy projects, as formulated in their electoral programmes.Footnote7

There are arguments both supporting and opposing the idea that minority and majority governments perform equally well at fulfilling pledges. The expectation of an equal performance depends on the government parties’ bargaining power. When considering whether a minority government is in a powerful bargaining position, two crucial conditions should be examined: whether they occupy the median position, and the extent of their agenda power, including for example the right of last amendment (Laver and Shepsle Citation1990; Crombez Citation1996; Tsebelis Citation2002; Ganghof et al. Citation2012). Agenda power and the control of the median legislator allow for the formation of dynamic and issue-specific legislative coalitions. In a standard spatial model, given the assumption that opposition parties are motivated by reasons solely to do with policy, a centrally located minority government might even be able to choose a support partner for its preferred policy change: right-wing parties will support changing a left-wing status quo towards a more right-wing policy, and vice versa. As a result, minority governments can enact laws in accordance with their own preferences (Tsebelis Citation2002, 97–99; Ward and Weale Citation2010; Ganghof et al. Citation2012, 888f). This means that government parties with and without a secure majority in parliament should be able to translate their election pledges into legislative outputs to the same degree – given that the government has a strong bargaining position, which as will be shown later, was the case with the minority coalition in NRW.

However, even if minority governments have positional advantages and agenda power, they might be restricted when translating their preferred policies outputs. Opposition parties – as potential support partners of minority governments – might not consider just their policy motives when evaluating their willingness to cooperate in the legislative arena. Ganghof and Bräuninger (Citation2006) have argued that a party’s policy-based utility function is conditional on expected consequences, such as losses in future elections. Even if minority governments have positional power, they may struggle to find support for their proposals when opposition parties have a low sacrifice ratio, that is, ‘the maximal policy sacrifice the actor is willing to make relative to its policy ambition’ (Ganghof and Bräuninger Citation2006, 525). A low sacrifice ratio is associated with opposition parties that have realistic chances of becoming part of a future government. Consider an opposition party with an ideological position very different to that of the minority government. If it has a low sacrifice ratio, because for example it considers itself to have a chance of becoming part of a future government, then it may not support a legislative proposal that moves the status quo to the minority government’s preferred policy, even if according to standard spatial models it would record relative policy gains from this policy change. Thus, opposition parties that have low sacrifice ratios ‘will not simply help the government to pass its own programme, but try to extract significant concessions’ (Ganghof and Bräuninger Citation2006, 526). In this situation, agenda power and a central location are not sufficient conditions for minority governments to find support partners for legislative coalitions and to directly enact bills in accordance with their preferences. When opposition parties have low sacrifice ratios, minority government parties need to make compromises on their own propositions to find support – and consequently, they will have lower rates on pledge fulfilment.

To summarise the discussion, I formulate two working hypotheses that guide the empirical analysis:

H2a (equal performance): Given a strong bargaining position, a minority government performs equally well in relation to election pledge fulfilment as a majority government.

H2b (concessions): Despite a strong bargaining position, a minority government tends to have a poorer performance on election pledge fulfilment when compared to a majority government, when opposition parties have a low sacrifice ratio.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The Minority and Majority Coalition in NRW

I compare the performance of two coalitions in relation to educational pledges: the minority government composed of the Social Democrats and the Green Party, who were in office after the elections in 2010, and the preceding majority government of the Christian Democratic Union and the Liberals, formed in 2005 in NRW. This section first introduces the minority government with regard to the theoretical considerations presented above, and then justifies the case selection for conducting a comparative analysis.

First, the red-green coalition was a substantial and powerful minority government. It did not rely on a stable support partner, and government and opposition parties were willing to negotiate with each other (Klecha Citation2010, 162; Ganghof et al. Citation2012; Vielstädte Citation2013, 119). The minority government was in a strong negotiating position because of positional advantages, agenda power and parliamentary seats occupied by the coalition parties. It was located in the centre of the ideological space. Among the parties that entered the parliament after the elections in 2010, the Social Democratic Party occupied the median position (Bräuninger and Debus Citation2012, 118). Due to this positional advantage the SPD conducted the coalition negotiations and finally, formed a minority government with the Green Party. Additionally, the minority had agenda power. According to article 68 of the state constitution of NRW it is the government’s right to hold a referendum, for example, if the parliament rejects one of its legislative propositions. The only way to avoid a referendum is the election of a new prime minister – which was very unlikely during the 15th legislative term since none of the other candidates were expected to receive a necessary majority in parliament. Moreover, the minority government was only one seat short of an absolute parliamentary majority. In the case of the abstention of one opposition party (or at least two opposition members), the minority government could pass bills in the legislation process (Grunden Citation2011).

In addition, there was an imminent danger that re-elections would need to be held, and especially the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP) and the Left Party were not interested in holding new elections as they feared failing to meet the five percent threshold and not re-entering the parliament (Ganghof et al. Citation2012, 898). In particular, the Left Party was in an exceptional situation, as it had only entered the parliament in NRW for the first time in 2010. Thus, in contrast to the CDU and FDP, it was unlikely to have any chance to be part of a future government, and so its motivation to participate in policy-making and be accommodating was relatively high from the beginning. The Left Party helped the social democrat Hannelore Kraft to be elected prime minister by abstaining in the second ballot, and during the legislature most legislative coalitions were formed with its support (Ganghof et al. Citation2012). The CDU’s willingness to cooperate and be accommodating might have been ambivalent. Both the CDU and SPD received the same number of seats and wanted the office of prime minister. The previous prime minister Jürgen Rüttgers (CDU) indicated his intention to remain in office by either forming a grand coalition with the SPD or a Jamaica coalition with the FDP and the Greens. The SPD however refused to support Rüttgers, instead desiring that its own candidate Kraft occupy the position, and the FDP was not interested in talking to the Greens after they had invited the Left Party together with the SPD to coalition talks – and so that also failed in the end. In summary, the minority government appears to have had good prospects for enacting its preferred policies: it was centrally located, possessed a significant amount of agenda power, and the Left Party appears to have had a high sacrifice ratio. Since the Left Party was located to the ideological left of the coalition parties, it was inclined to be a legislative support partner that would help government parties enact pledges that would move the status quo to the left. However, the minority government’s bargaining power might also have been restricted due to the lower sacrifice ratios possessed by the CDU and FDP. In instances where the SPD and Greens wanted (or had) to form legislative majorities with one of the other two parties, they might have been forced to make concessions.

Second, the majority and minority coalition in NRW selected for comparison make it possible to control for a great degree of extraneous variance: the institutional and political-cultural setting remains the same. Normally, researchers study the functioning of minority governments in those countries where minority governments frequently occur, such as in Scandinavia (Strøm Citation1990; Christiansen and Pedersen Citation2014; Klüver and Zubek Citation2017). But institutions and behaviour patterns have adapted over the years in these countries, lending bias to their results. For instance, the relationship between government and opposition parties has sometimes been institutionalised in the form of formal agreements. As a consequence, minority governments gain stability but lose flexibility. In Germany, minority government formation is uncommon. At the federal level, there are – aside from ‘caretaker governments’ – no examples of a minority government in office. At the state level, two parties usually form a majority government (Klecha Citation2010). All governments in North Rhine-Westphalia, except between 2010 and 2012, have had a majority in parliament and between 1946 and 2010, there have only been four one-party governments as opposed to 17 coalition governments. Hence, this study is conducted in an environment where minority governments are atypical and therefore controls variables that are caused by institutional adaptations rather than by a government’s majority status itself.Footnote8

Furthermore, the ideological distance between the coalition partners on the socio-cultural dimension was similar for the minority and the majority government (Bräuninger and Debus Citation2012, 188). Hence, the intra-coalitional conflict potential on the issue of education was similar for both governments. Additionally, both coalitions succeeded governments composed of different parties. Consequently, the status quo was far away from many of the requested policy changes which facilitated policy change. For example, the parties of the majority coalition committed to introducing tuition fees at universities and to introducing behaviour grades – and could implement it. The minority coalition parties abolished those measures.

This study focuses on pledges related to education because it is the most important policy field whose responsibility lies exclusively with the German states. In most policy areas the German federation and the states are shared sovereigns, whereas the federation is exclusively responsible for matters of defence and foreign relations. For policies dealing with culture and education however, the States of Germany have exclusive responsibility (Art. 30 of the German Constitution). Education comprises various issues from child care, education (primary school to university) and vocational training, to research and science (Hepp Citation2011). In addition, there was significant media attention during the electoral campaign in NRW on educational issues (Burger Citation2010; Graalmann and Schultz Citation2010; Spiegel Citation2010; Vitzthum Citation2010), and according to surveys, education was (together with the labour market) the most important issue for voters in 2005 and 2010 in NRW (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen Citation2005, Citation2010).

This study controls for time. The minority coalition ended early after two years of existence on 14 March 2012. In total, it was in office 609 days. The fail of the minority government was a consequence of budget rejection in parliament. Initially, the opposition parties did not want to reject the entire budget proposal. They instead wanted to gain bargaining power by opposing one section of the government’s budget bill, but were not aware of the fact that the denial of one section of the budget results in the rejection of the whole budget. Shortly before the parliamentary vote, a legal report informed the parliament about the procedure, but the opposition nevertheless did not change its strategy at the last minute (Ganghof et al. Citation2012). In order to obtain equivalent results, I investigate only the first two years of the majority coalition’s term. More specifically, I analyse the legislative period before the 22 February 2010, which includes the adoption of the budget for 2007.Footnote9

Measurement of Pledge Support in the Coalition Agreement and Pledge Fulfilment

In the first step of the data collection, election pledges had to be identified before their status – in terms of inclusion in the coalition agreement and fulfilment (the dependent variables of interest) – could be determined. The quantity and quality of pledges differ within and between electoral programmes (Naurin Citation2014). As a consequence, what a pledge actually is (as it appears in this study) had to be clearly defined. In total, 82 election pledges from the government parties in the majority coalition (30 CDU, 52 FDP) and 101 from those in the minority coalition have been identified (34 SPD, 67 The Greens). As has been stated above, the study focuses on educational pledges in order to ensure exclusive autonomy on decision making at the state level. Mere implementations of educational policies decided by the European Union or the German federal government are not considered because the scope of political action by the regional government is enormously restricted.

Each pledge considered in this study is precise and comprised of an action as well as a shift in the status quo. A pledge should offer a clear commitment and one should be able to determine whether it was fulfilled: ‘A pledge is a statement committing a party to an action or outcome that is testable: That is, we can gather evidence and make an argument that the action or outcome was either accomplished or not.’ (Thomson et al. Citation2017, 532, emphasis in original). An example of a vaguely formulated commitment that does not meet the testability criteria and is therefore not defined as a pledge is the following: ‘we support fair treatment for all’ (Thomson et al. Citation2017, 532). I exclude these types of vague commitments. Furthermore, I focus on pledges that constitute an action, and exclude those promises that constitute a goal but not the means (outcome pledges). It is doubtful that it can be determined whether the fulfilment of outcome pledges is really caused by enacted policies.Footnote10 Additionally, I also exclude pledges favouring the status quo in order to avoid biased results. It is easier for a party to enact status quo maintaining commitments than pledges asking for a policy change (Costello and Thomson Citation2008, 250; Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2014, 577). It might be the case that the subject was not discussed or that the parties could not agree on a new policy, and as a consequence the status quo remained. In the data considered, all status quo maintaining pledges were fulfilled, though more of these pledges originated from the majority government. Consequently, I focus on pledges requiring policy change and exclude status quo maintaining pledges, in order to control for the effect of pledge type.

In the first stage of the analysis, I considered whether a pledge was mentioned in the coalition agreement. A pledge can be not supported, partially supported or fully supported in the coalition agreement. A pledge was identified as fully supported if the coalition agreement fully reflected its ideas, for example the abolition of tuition fees that was proposed by the SPD and Greens in 2010. The category of partial support was used if the coalition agreement generally reflected a party’s favoured policy, but did not encompass all aspects, had slight variations or was less concrete. For example, the Greens promised in 2010 to introduce Islamic religious education in school in German and to establish chairs at universities in NRW in order to train those teachers of the Islamic religion. In the coalition agreement with the SPD, the intention to introduce Islamic religious classes held in German and supervised by German school authorities was supported, but there were no details in relation to establishing new chairs for ensuring the relevant training of teachers. A pledge was identified as not supported if the policy mentioned in the electoral programme was not addressed in the coalition agreement.

In determining the legislative enactment status of a pledge, I categorised each pledge as either not fulfilled, partially fulfilled or fully fulfilled. A pledge is unfulfilled if no ‘significant [legislative] action has taken place’ (Naurin Citation2014, 1052). Partial fulfilment means that a party succeeded in significantly changing the status quo but did not fully achieve its objective. For example, the FDP promised in 2005 to introduce mandatory German language tests for children one year before starting school, and if children fail, language training for one year should be obligatory. The language test was introduced in 2006, but the additional language training was not mandatory. The coding decision of the status of fulfilment was made on the basis of laws during the term of the minority coalition (2010–12) and during the first two years of the majority coalition’s term (2005–07). The restriction to bills recognises the high degree of commitment of pledge fulfilment required, and the importance of parliament as a crucial decision making arena. Extra parliamentary agreements with non-democratically legitimised stakeholders, and non-legislative actions involving a lesser degree of commitment and not requiring parliamentary confirmation (secondary legislation) were excluded from the analysis.

Measurement of Control Variables

Following the approach that has been suggested by CPPP-scholars (Thomson et al. Citation2017), I include a number of control variables which possibly obscure the relation between the majority status and the two dependent variables. I consider the relations among pledges made by different parties. First, I control for intra-coalitional agreement. Therefore, I identified whether a pledge was supported by all government parties. A pledge that is supported by both government parties is more likely to be fulfilled than a pledge that is supported by only one government party. Common pledges do not require major intra-coalitional bargaining and therefore have a higher chance of being enacted, shown by various studies (Thomson Citation2001; Kostadinova Citation2013; Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2014; Thomson et al. Citation2017). I identify a pledge as supported if government parties generally agree on the favoured policy even if their preferred specifics vary slightly. For example. both coalition parties want more kindergarten, the SPD asked for 10 new kindergarten and the Greens for 12. However, non-agreement is not the same as disagreement between parties. It only means that a pledge of one party does not correspond to a pledge of an-other party because the latter did not mention the policy in its own electoral programme (Costello and Thomson Citation2008, 243). Still, I expect agreement between government parties to positively influence the chance of a pledge to be fulfilled.

I also consider the relation between pledges made by government and opposition parties. I identified whether a pledge formulated by a government party was supported by at least one opposition party. Especially for the minority government, agreement with opposition parties might have increased the likelihood of a pledge to be fulfilled.Footnote11

Lastly, I consider whether or not a pledge originated from a government party receiving the prime ministership or the relevant ministerial portfolio. According to models of government formation, a party that receives the prime ministership has greater control over legislation when compared to a junior partner (Austen-Smith and Banks Citation1988). In the portfolio approach, a pledge is more likely to be fulfilled if a party holds the relevant portfolios (Laver and Schofield Citation1990; Thomson et al. Citation2017, 530). During the minority government’s term, the social democratic Hannelore Kraft was prime minister, and the Christian Democrat Jürgen Rüttgers was prime minister of the majority coalition. The pledges from both governments were related to different portfolios that were either controlled by the executive chief’s party or the junior partner. Nearly half of all pledges from the minority government parties (48 from 101) were concerned with school and training issues, for which the Green Party had ministerial power. The SPD had responsibility for early childhood education, vocational training, and for higher education and research. For the majority coalition, three quarters of pledges were concerned with childhood education, school education, and vocational and continuous training, over which the executive chief’s party, the CDU, had ministerial control. The FDP was responsible for higher education and research.Footnote12

ANALYSES OF THE MINORITY AND MAJORITY COALITION IN NRW

For the analysis, two stages must be considered: both the inclusion of a pledge in the coalition agreement and the legislative enactment of a pledge, in the context of a government’s majority status.

Support in Coalition Agreement

An initial look at the average percentages per government suggests that the minority government differs from the majority coalition with regards to pledge support in the coalition agreement: the relative share of pledges that are at least partially supported in the coalition agreement is higher by more than eight percent for the parties of the majority government (50 vs 58 per cent).

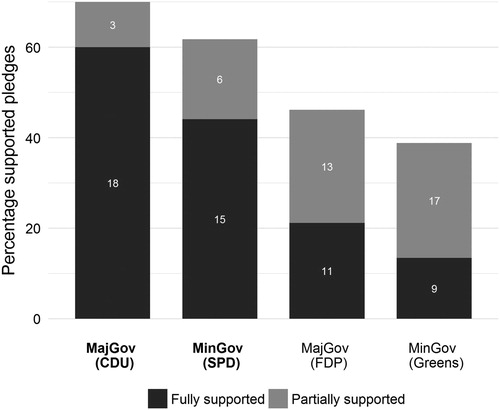

breaks pledge support in coalition agreement and fulfilment down by party and differentiates between partial and full support. It indicates that differences in supporting pledges in the coalition agreement are also found at the party level. For both governments, the large government parties holding the prime ministership have higher rates of pledges supported by the coalition agreement than their junior partners. However, between the CDU and SPD there is a difference of eight percent for the category of at least partial support. In addition, for full support, not only the relative share but also the total number of pledges is higher for the CDU. Likewise, when looking at the junior partners, it becomes obvious that the FDP when compared to the Green Party had the advantage when concluding its pledges in the coalition agreement with the Christian Democrats.

FIGURE 1 PLEDGE SUPPORT IN COALITION AGREEMENT BY PARTY

Note: n = 183; each bar refers to all pledges made by one party; MajGov-Majority Government, MinGov-Minority government; parties printed in bold hold the prime ministership; the white numbers in each bar indicate the total numbers of partially and fully supported pledges. Source: Own data.

The difference regarding the extent to which electoral pledges entered the coalition agreement of both governments is especially interesting when considering that the agreement at the pledge level amongst the minority government’s coalition partners initially was higher than the majority government’s: 59 per cent for the SPD and 28 per cent for the Greens in contrast to 43 per cent for the CDU and 21 per cent for the FDP. The minority government’s coalition agreement did not include the 20 per cent of pledges common to both parties (four pledges of each party), whereas the coalition agreement of the majority government included all but one of their common pledges (96 per cent).

The results given by correlate with the multivariable binary regression model in that accounts for further hypothesised confounding variables, such as the agreement between government parties at the pledge level. The model calculates the odds ratio of a pledge being included in the coalition agreement (1 = partially/fully supported; 0 = not supported), with respect to a government’s majority status. Each of the 183 observations refers to one of the educational pledges that has been identified. The parties in the minority government are the reference category. The odds ratio of 2.31 for the variable majority government indicates that the odds of pledge fulfilment are 131 per cent higher for the majority than for the minority government. The model also reveals that agreement between the coalition partners has a strong, significant effect. The coefficients for the other variables – agreement with the opposition parties and control of resources (prime minister and ministry) – are also positive, but much weaker and not statistically significant.Footnote13

TABLE 1 EXPLAINING SUPPORT OF PLEDGES IN THE COALITION AGREEMENT

Pledge Fulfilment

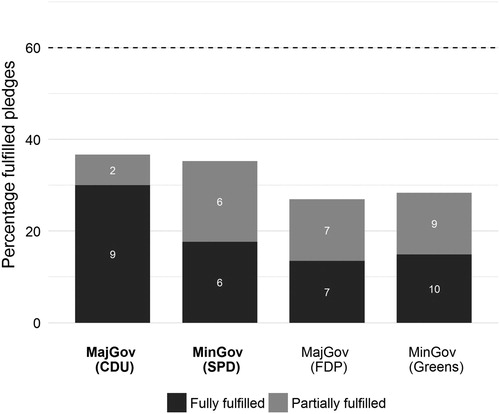

A descriptive comparison of the average percentages of pledge fulfilment per government suggests that there is no substantial difference between the minority and majority government: for both governments, 32 per cent of the pledges were at least partially fulfilled. The low rates of pledge fulfilment indicate that the majority of pledges remained unfulfilled: 70 of 101 pledges from the minority government parties and 57 of 82 pledges from the majority government parties. In comparison with other studies that show average enactment rates of 60 per cent, this is relatively low. Though, this is not surprising on account of the shortened legislative term of two years instead of five.

reveals a more detailed view on the status of pledge fulfilment by party. For the junior partners, the rates of pledge fulfilment are similar; the Green Party even slightly outperforms the FDP in absolute and relative numbers. For the large parties, when full and partial fulfilment are taken together – as is usually done by pledge scholars (Schermann and Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2014; Thomson et al. Citation2017) – there is no difference between the CDU and SPD.

FIGURE 2 PLEDGE FULFILMENT BY PARTY

Note: n = 183; the dashed line represents the average pledge fulfilment as shown by previous studies (Pétry and Duval Citation2015; Thomson et al. Citation2017). Source: own data.

The multivariable model in also support that the parties in the majority government do not show a better performance on pledge performance when compared to those of the minority government. reports the results of two binary logistic regressions that calculate the odds ratios of a pledge being enacted (1 = full/partial fulfilment; 0 = non-fulfilment), with respect to a government’s majority status while controlling for other factors. Model B adds support of a pledge in the coalition agreement as an additional predictor. Both models suggest that minority and majority governments perform equally in terms of pledge fulfilment: pledges supported by the majority government parties do not have higher odds of being enacted than those supported by the minority government parties. Apart from ‘prime minister’, the effects of the control variables are consistent with results of recent studies: agreement between government parties has a strongly positively effect on pledge enactment, and so does pledge support in coalition agreements (model B).Footnote14 The variables considering whether the pledge-making party holds the prime ministership or relevant ministry, and if an opposition party supports a pledge, do not or only marginally influence the odds ratio of legislative pledge enactment.Footnote15 Consequently, it appears that there is no substantial difference in performance on party pledge fulfilment when a government does not have a majority in parliament.

TABLE 2 BINARY LOGISTIC REGRESSION FOR EXPLAINING PLEDGE FULFILMENT

However, also includes information on the quality of pledge fulfilment (partial vs full fulfilment). It suggests that the chief executive’s party of the minority government, the SPD, was at a disadvantage with regards to fully translating its pledges into legislative outputs, when compared with the CDU. Nearly one third of all CDU pledges are fully fulfilled, whereas the share of full fulfilment for the SPD is much lower with 18 per cent. It is worth taking a closer look at these partial fulfilments.

Four of the six partially enacted SPD-pledges were also supported by coalition partner the Greens, and three among these were fully supported in the coalition agreement. One of these pledges concerns the structure of the school system in NRW – an issue that had attracted a lot of attention during the electoral campaign and for which all parties had formulated positions in their manifestos. The SPD pledged to enter a new era of the school system and to switch from the existing model to a ‘school of future’. The existing school model consisted of joint learning until the 4th grade, and after that pupils were allocated to different schools with varying educational levels depending on their performance. The SPD wanted to expand the period of joint learning to make it compulsory until the 6th grade, and after that voluntary, if desired by parents and teachers. Therefore, the different existing secondary schools (Hauptschule, Realschule, and Gymnasium) would be brought together into one school type, so called ‘Gemeinschaftsschulen’. The Greens supported the establishment of Gemeinschaftsschulen, but promised a longer period of compulsory joint teaching – until the 10th grade. The CDU, in contrast, stated in its electoral programme they would maintain the existing structured secondary school system. In the end, the government reached a compromise: the ‘school consensus’, with the CDU demanding concessions from the SPD as well from the Greens. The structured system was not abolished, but ‘Sekundarschulen’ were introduced as an additional school type. Sekundarschulen offered joint teaching until the 6th grade, and after that pupils could attend schools of different education levels. At first, one might have expected a different outcome. Initially the government did indeed want to establish Gemeinschaftsschulen without any legal basis, but the constitutional court declared this as unlawful. In reaction to this, the government drafted a bill in order to enact its vision. If just considering the parties’ policy motives, the Left Party would have been the most likely support partner in implementing the government’s school project.Footnote16 But the government withdrew this proposal, and shortly thereafter another bill jointly drafted with the CDU was introduced and finally passed as the 6th amendment of the school law in 2011. There were also additional motivations leading to this agreement. Concurrent with the revision of the legislation, changes in the NRW-constitution were made, for which a two-third majority in parliament (that the minority government only reached with support of the CDU) was necessary. Thus, during the tough negotiations on the school issue, the power and flexibility of the minority government was obviously restricted. But the agreement also forced concessions from the CDU, who had initially not wanted to change anything. The school consensus that was finally reached resolved a protracted conflict over the school system. The involved parliamentary parties were interested in an agreement amounting to a sustainable and cross-wing compromise, and the final outcome demanded concession from all parties.

CONCLUSION

Returning to the initial question: did the minority and the majority coalitions in NRW perform equally? This study has shown that the minority and its preceding majority coalition performed equally in terms of at least partially enacting each government party’s policy proposals as legislation – a result that fits with previous studies . This study has contributed to the debate by analysing legislative performance of a real minority coalition – neither with a pre-election agreement between the coalition partners nor a stable support partner among the opposition – at the regional level.

In addition, the results suggest that the quality of pledge fulfilment of a party is related to whether that party holds the position of prime minister. More pledges from the SPD in the minority government were only partially and not fully fulfilled when compared to the CDU. A more thorough look at one of the most important compromises that the Social Democrats and the Greens reached with the Christian Democratic Union in 2011, the ‘school consensus’, shows that the CDU, which had a low sacrifice ratio, was able to extract significant concessions from the government parties. However, this particular agreement was a compromise for all parties and also required concessions from the CDU, who initially had wanted to maintain the status quo. Consequently, it is hard to generalise from this finding and further research is needed that considers the quality of pledge fulfilment – as a measure of legislative concessions.

This study went beyond existing studies by going further than just comparing the input-output-linkage and by prying open the black box of decision making in coalitions. The analysis has shown that fewer pledges of the minority government parties entered the coalition agreement. Coalition partners without a legislative majority and who have to manage high uncertainty appear to act with restraint when drafting the coalition agreement. A coalition agreement of narrow scope avoids failure and signals to the opposition parties that there is an open negotiation-arena.

These findings have important implications for understanding legislative effectiveness and political representation in times of high uncertainty. First, this study has provided further evidence that minority governments are as effective as majority governments (Crombez Citation1996; Thomson et al. Citation2017) – at least for the time that they are in office. On average, both governments had enacted a third of their original pledges in less than half of their terms (two out of five years). Even still, minority governments remain a complex phenomenon. In absolute terms, minority governments have a poorer performance when compared to majority governments because they are often terminated before the end of the legislative term (Lijphart Citation2012, 125), as was the case for the red-green minority government studied. However, this study's interest was to analyse how effective minority governments are during the time that they are in office, and it showed that the minority government parties were not disadvantaged in at least partially fulfilling their pledges. Consequently, with regard to promissory representation at the regional level (Mansbridge Citation2003; Pétry et al. Citation2015), both cabinets have proved to be equally responsible with respect to pledge fulfilment. Second, the difference in quality of pledge fulfilment that has been found is not necessarily synonymous with a worse performance. Instead, one might argue that minority governments give opposition parties opportunities to influence policy making – and the revival of parliamentary deliberation amongst parties with different ideologies has a strong normative desirability in democratic regimes (Strøm Citation1990; Powell Citation2000; Lijphart Citation2012; Ganghof Citation2015). Third, with regard to differences in coalition contracting, comprehensive coalition agreements are obviously not the only methods that can be used to coordinate intra-coalition policy making and combat the moral hazard problems that arise as a result of delegation to ministers (Indridason and Kristinsson Citation2013). Government parties that have no majority in parliament also anticipate that further bargaining may be necessary in the legislative arena, and so they limit themselves when communicating common political visions to their voters and the other parties in parliament.

Generalisation of the results is limited due to the small number of cases. Nevertheless, the choice of research design has provided a high control over extraneous variance. More comparative studies on minority governments’ legislative performances, especially those that look at quality of pledge fulfilment, are desirable. Such studies should give attention to issues particular to minority governments; for example, how they manage to build legislative majorities. More in-depth studies looking at legislative decision making, and examining how minority governments and especially minority coalitions adapt their behaviour, also have great potential to uncover further insights. The ‘auto-limitation hypothesis’ when drafting the coalition agreement – suggested in this paper, needs to be empirically tested in further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Aiko Wagner, Pola Lehmann, Thomas M. Meyer and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Theres Matthieß has been a researcher in the long-term DFG-funded MARPOR project since 2015. Her research focusses on political representation, party pledge fulfilment, and electoral accountability from a comparative perspective.

Notes

1 Frequently, minority coalitions are thought to perform poorly (Bäck, Debus, and Dumont Citation2011; Thomson et al. Citation2017); however until now, we have known little about how they actually work. Thomson et al. (Citation2017) consider four minority coalitions (of a total of 57 executives), but two of them had a stable support partner, and consequently should be considered as ‘hidden majority governments’, see (Strøm Citation1990, 94–99; Ganghof et al. Citation2012, 888). The two remaining minority coalitions in Italy and Sweden were part of pre-coalitions with joint manifestos, and consequently coalition partners a priori agreed on policies. This analysis provides evidence of party pledge fulfilment for a minority coalition that did not have a stable support partner and where the governing parties were not part of pre-electoral coalitions.

2 The original definition by Thomson et al. (Citation2017) also includes outcome pledges that are excluded from this analysis, see Chapter 3.3.

3 In some countries where minority governments are common, the practice of drafting of coalition agreements was established relatively late (e.g. 1994 in Denmark), see Christiansen and Pedersen (Citation2014, 4).

4 Indridason and Kristinsson (Citation2013) argue that substantive minority coalitions do not draft coalition agreements at all, but their empirical support for this argument is less convincing than that of other findings. Obviously, there are substantive minority coalitions, for example in NRW and Denmark (Christiansen and Pedersen Citation2014), where coalition agreements have been drafted.

5 Even though coalition agreements are not legally binding, they do not appear to be cheap talk. Empirical evidence suggests that they are very good predictors of government parties’ legislative agendas. Moury (Citation2011) finds that most pledges included in coalition agreements in Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy are transferred into cabinet decisions, and studies of pledge fulfilment have shown that the likelihood of enactment of elections pledges significantly increases when they have been included in the coalition agreement (Thomson Citation2001; Costello and Thomson Citation2008; Thomson et al. Citation2017). In addition, coalition agreements appear to increase cabinet stability (Timmermans and Moury Citation2006; Krauss Citation2018).

6 Some empirical evidence for a narrow scope of coalition agreements in situations of high uncertainty has been already provided by Müller and Strøm (Citation2010), but in their study the scope of a coalition agreement is measured by its length and not in terms of its content, and minority governments are not explicitly addressed.

7 In this sense, concentrating on legislation is a very stringent test. In order to avoid having to pass legislation, the minority government could try to implement policies without legal approval – which the minority government in NRW did indeed attempt.

8 ‘Contract parliamentarism’ (Bale and Bergman Citation2006).

9 The minority government enacted 59 bills during the time it was in office. During the same time period, the majority government passed fewer laws (46). One might object that it is unfair to restrict the majority government to the same time period, because the minority government parties knew about their fragile situation and may have rushed to complete as many projects as they could as soon as possible. However, the results do not change when considering 13 more bills for the majority government (in order to reach the same total of 59 bills).

10 For the distinction between outcome and action pledges, see Naurin (Citation2011, 55). One example of an outcome pledge is the decrease in the rate of unemployment. If the goal is attained it is hard to determine whether the promise was fulfilled due to a specific political measure or due to general economic growth.

11 I include this control variable as a precautionary measure, even though other analyses have provided evidence that this probably does not have an effect (Thomson et al. Citation2017, 537).

12 The SPD controlled the ministries for ‘Innovation, Science and Research’ and ‘Work, Integration and Social Affairs’, and the Greens held the ministry for ‘School and Training’. The CDU controlled the ministries for, Work, Health and Social Affairs’ and ‘School and Training’, and the FDP held the ministry for ‘Innovation, Science, Research and Technology’.

13 I have also estimated a multinominal logistic regression that considers all three values the dependent variable can take (not, partially or fully supported). However, the results are not substantially different, so I only present the results of the binary regression in the main text.

14 Thomson et al. (Citation2017, 537) have found evidence that a pledge originating from a party which holds the prime ministership is more likely to be enacted.

15 Also when “ministry” is taken out of the model, there is still no effect for “prime minister” – and vice versa.

16 The Left Party had the most progressive position and wanted to abolish the existing system and unify different schools into ‘one school for all’: a full-time day school until the 10th class level, without any school grades and full integration of disabled children.

REFERENCES

- Aragonès, Enriqueta, Andrew Postlewaite, and Thomas Palfrey. 2007. “Political Reputations and Campaign Promises.” Journal of the European Economic Association 5 (4): 846–884. doi:10.1162/JEEA.2007.5.4.846.

- Austen-Smith, David, and Jeffrey Banks. 1988. “Elections, Coalitions, and Legislative Outcomes.” The American Political Science Review 82 (2): 405–422. doi:10.2307/1957393.

- Bale, Tim, and Torbjörn Bergman. 2006. “Captives No Longer, but Servants Still? Contract Parliamentarism and the New Minority Governance in Sweden and New Zealand.” Government and Opposition 41 (3): 422–449. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2006.00186.x.

- Bäck, Hanna, Marc Debus, and Patrick Dumont. 2011. “Who Gets What in Coalition Governments? Predictors of Portfolio Allocation in Parliamentary Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (4): 441–478. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01980.x.

- Beyme, Klaus von. 1970. Die Parlamentarischen Regierungssysteme in Europa. München: R. Piper.

- Bräuninger, Thomas, and Marc Debus. 2012. Parteienwettbewerb in den deutschen Bundesländern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Burger, Reiner. 2010. “Eine Doppelpressekonferenz namens Fernsehduell.” Frankfurter Allgemeine, April 27. http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/wahl-in-nrw/nrw-wahl-eine-doppelpressekonferenz-namens-fernsehduell-1968689.html.

- Christiansen, Flemming Juul, and Helene Helboe Pedersen. 2014. “Minority Coalition Governance in Denmark.” Party Politics 20 (6): 940–949. doi:10.1177/1354068812462924.

- Conley, Richard S. 2011. “Legislative Activity in the Canadian House of Commons: Does Majority or Minority Government Matter?” American Review of Canadian Studies 41 (4): 422–437. doi:10.1080/02722011.2011.623237.

- Costello, Rory, and Robert Thomson. 2008. “Election Pledges and Their Enactment in Coalition Governments: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 18 (3): 239–256. doi:10.1080/17457280802227652.

- Crombez, Christophe. 1996. “Minority Governments, Minimal Winning Coalitions and Surplus Majorities in Parliamentary Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 29 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00639.x.

- Eichorst, Jason. 2014. “Explaining Variation in Coalition Agreements: The Electoral and Policy Motivations for Drafting Agreements.” European Journal of Political Research 53 (1): 98–115. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12026.

- Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. 2005. “Landtagswahl in Nordrhein-Westfalen: 22. Mai 2005.” http://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Wahlen/Wahlanalysen/Newsl_Nord05_2.pdf.

- Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. 2010. “Landtagswahl in Nordrhein-Westfalen: 9. Mai 2010.” http://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Wahlen/Wahlanalysen/Newsl_NRW_10.pdf.

- Ganghof, Steffen. 2015. “Four Visions of Democracy: Powell's Elections as Instruments of Democracy and Beyond.” Political Studies Review 13 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1111/1478-9302.12069.

- Ganghof, Steffen, and Thomas Bräuninger. 2006. “Government Status and Legislative Behaviour Partisan Veto Players in Australia, Denmark, Finland and Germany.” Party Politics 12 (4): 521–539. doi:10.1177/1354068806064732.

- Ganghof, Steffen, Christian Stecker, Sebastian Eppner, and Katja Heeß. 2012. “Flexible und inklusive Mehrheiten? Eine Analyse der Gesetzgebung der Minderheitsregierung in NRW.” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 43 (4): 887–900.

- Graalmann, Dirk, and Tanjev Schultz. 2010. “Abgehängt in NRW.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 21. http://www.sueddeutsche.de/karriere/debatte-um-schulsystem-abgehaengt-in-nrw-1.939311#redirectedFromLandingpage.

- Grunden, Timo. 2011. “Düsseldorf ist nicht Magdeburg–oder doch. Zur Stabilität und Handlungsfähigkeit der Minderheitsregierung in Nordrhein-Westfalen.” Regierungsforschung.de, Politikmanagement und Politikberatung.

- Hepp, Gerd F. 2011. Bildungspolitik in Deutschland: Eine Einführung. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Indridason, Indridi H., and Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson. 2013. “Making Words Count: Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Management.” European Journal of Political Research 52 (6): 822–846. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12022.

- Johnson, Nevil. 1975. “Adversary Politics and Electoral Reform: Need We Be Afraid?.” In Adversary Politics and Electoral Reform, edited by S. E. Finer, 79–95. London: William Clowes.

- Kim, Dong-Hun, and Gerhard Loewenberg. 2005. “The Role of Parliamentary Committees in Coalition Governments: Keeping Tabs on Coalition Partners in the German Bundestag.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (9): 1104–1129. doi:10.1177/0010414005276307.

- Klecha, Stephan. 2010. Minderheitsregierungen in Deutschland. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Landesbüro Niedersachsen.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Richard I. Hofferbert, and Ian Budge. 1994. Parties, Policies, and Democracy. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Radoslaw Zubek. 2017. “Minority Governments and Legislative Reliability.” Party Politics 1–12. doi:10.1177/1354068817695742.

- Kostadinova, Petia. 2013. “Democratic Performance in Post-Communist Bulgaria: Election Pledges and Levels of Fulfillment, 1997–2005.” East European Politics 29 (2): 190–207. doi:10.1080/21599165.2012.747954.

- Krauss, Svenja. 2018. “Stability Through Control? The Influence of Coalition Agreements on the Stability of Coalition Cabinets.” West European Politics 1–23. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1453596.

- Laver, Michael, and Norman Schofield. 1990. Multiparty Government: The Politics of Coalition in Europe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle. 1990. “Coalitions and Cabinet Government.” The American Political Science Review 84 (03): 873–890.

- Lijphart, Arend. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Mansbridge, Jane. 2003. “Rethinking Representation.” American Political Science Review 97 (04): 515–528. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000856.

- Mayhew, David R. 2005. Divided we Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking and Investigations, 1946-2002. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Moury, Catherine. 2011. “Coalition Agreement and Party Mandate: How Coalition Agreements Constrain the Ministers.” Party Politics 17 (3): 385–404. doi:10.1177/1354068810372099.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm. 2003. Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm. 2010. “Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: the Democractic Life Cycle in Western Europe, edited by Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, 159–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Naurin, Elin. 2011. Promising Democracy. Parties, Citizens and Election Promises. Department of Political Science; Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

- Naurin, Elin. 2014. “Is a Promise a Promise? Election Pledge Fulfilment in Comparative Perspective Using Sweden as an Example.” West European Politics 37 (5): 1046–1064. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.863518.

- Pétry, François, Lisa Birch, Èvelyne Brie, and Aldan Hasanbegovic. 2015. “Le gouvernement de Philippe Couillard tient-il ses promesses?” In L'état du Québec 2015: 20 clés pour comprendre les enjeux actuels, edited by Annick Poitras, Michel Venne, Serge Belley, and Louis-Félix Binette, 119–129. Montréal: Del Busso.

- Pétry, François, and Dominic Duval. 2015. “La réalisation des promesses des partis au Québec 1994-2014: Communication présentée dans le cadre du Congrès annuel de la Société québécoise de science politique.” Unpublished manuscript, last modified March 02, 2018. https://www.poltext.org/sites/poltext.org/files/petry_duval_sqsp_20151_0.pdf.

- Powell, G. Bingham. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Schermann, Katrin, and Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik. 2014. “Coalition Policy-Making Under Constraints: Examining the Role of Preferences and Institutions.” West European Politics 37 (3): 564–583. doi:10.1080/01402382.2013.841069.

- Spiegel. 2010. “SPD abgewählt.” Spiegel, May 22. http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/nrw-wahl-spd-abgewaehlt-cdu-triumphiert-a-357071.html.

- Steffani, Winfried. 1997. “Zukunftsmodell Sachsen-Anhalt? Grundsätzliche Bedenken.” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 28 (4): 717–722.

- Strøm, Kaare. 1990. Minority Government and Majority Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strøm, Kaare. 1997. “Democracy, Accountability, and Coalition Bargaining. The 1996 Stein Rokkan Lecture.” European Journal of Political Research 31 (1–2): 47–62.

- Strøm, Kaare, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Daniel Markham Smith. 2010. “Parliamentary Control of Coalition Governments.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (1): 517–535. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.071105.104340.

- Strøm, Kaare, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, eds. 2010. Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: The Democractic Life Cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thies, Michael F. 2001. “Keeping Tabs on Partners: The Logic of Delegation in Coalition Governments.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 580. doi:10.2307/2669240.

- Thomson, Robert. 2001. “The Programme to Policy Linkage: The Fulfilment of Election Pledges on Socio–Economic Policy in The Netherlands, 1986–1998.” European Journal of Political Research 40 (2): 171–197. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00595.

- Thomson, Robert, Terry Royed, Elin Naurin, Joaquín Artés, Rory Costello, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Mark Ferguson, et al. 2017. “The Fulfillment of Parties’ Election Pledges: A Comparative Study on the Impact of Power Sharing.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 527–542. doi:10.1111/ajps.12313.

- Timmermans, Arco, and Catherine Moury. 2006. “Coalition Governance in Belgium and The Netherlands: Rising Government Stability Against All Electoral Odds.” Acta Politica 41 (4): 389–407. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500139.

- Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; Princeton University Press.

- Vielstädte, André. 2013. Der Kraftakt: Die Minderheitsregierung in Nordrhein-Westfalen: Funktionsbedingungen von Minderheitsregierungen im parlamentarischen Regierungssystem der Bundesrepublik Deutschland auf Landesebene. Eine empirische Analyse. München: GRIN Verlag.

- Vitzthum, Thomas. 2010. “In NRW steht ein Schulkrieg ums Gymnasium bevor.” Welt, May 5. https://www.welt.de/politik/bildung/article7486972/In-NRW-steht-ein-Schulkrieg-ums-Gymnasium-bevor.html.

- Ward, Hugh, and Albert Weale. 2010. “Is Rule by Majorities Special?” Political Studies 58 (1): 26–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00778.x.