Abstract

A widespread view in political science is that minority cabinets govern more flexibly and inclusively, more in line with a median-oriented and 'consensual' vision of democracy. Yet there is only little empirical evidence for it. We study legislative coalition-building in the German state of North-Rhine-Westphalia, which was ruled by a minority government between 2010 and 2012. We compare the inclusiveness of legislative coalitions under minority and majority cabinets, based on 1028 laws passed in the 1985–2017 period, and analyze in detail the flexibility of legislative coalition formation under the minority government. Both quantitative analyses are complemented with brief case studies of specific legislation. We find, first, that the minority cabinet did not rule more inclusively. Second, the minority cabinet’s legislative flexibility was fairly limited; to the extent that it existed, it follows a pattern that cannot be explained on the basis of the standard spatial model with policy-seeking parties.

INTRODUCTION

It is widely believed that minority cabinets govern more flexibly and inclusively, more in line with a median-oriented and ‘consensual’ vision of democracy. Ward and Weale (Citation2010) argue that minority cabinets can lead to flexible legislative coalition-building and empower the issue-specific median party in parliament (see also Weale Citation2018). Lijphart (Citation1999, 104) treats multi-party minority cabinets as similar to oversized cabinets and as indicators of a consensual style of democracy. Moury and Fernandes (Citation2018, 351) combine these two ideas and suggest that ‘[m]inority governments offer a more inclusive and consensual democracy by giving the median party the pivotal role for legislation approval.’

These views are highly relevant for current debates about the performance of different cabinet types and how institutional reforms might facilitate better democratic performance. Yet, while scholars gained robust insights into the fiscal and electoral performance (Powell Citation2000, 54; Pech Citation2004) as well as the stability of different cabinet types (Saalfeld Citation2008; Grotz and Weber Citation2012), there is less systematic empirical evidence on inclusiveness and flexibility. The legislative coalition-building tendencies of majority and minority cabinets are often studied with a focus on legislative success (Cheibub, Przeworski, and Saiegh Citation2004; Field Citation2016), pledge fulfilment (Moury and Fernandes Citation2018; Matthiess Citation2019), the compliance with legislative programmes (Klüver and Zubek Citation2017) or government-opposition voting (Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2006; Godbout and Høyland Citation2011; Louwerse et al. Citation2017; De Giorgi and Ilonszki Citation2018). When studies look (at least indirectly) at inclusiveness, the emerging picture is far from clear. For instance, the evidence presented by Christiansen and Pedersen (Citation2014, 947) suggests that the rare majority cabinets in Denmark do not govern less inclusively than the more common minority cabinets (see also Green-Pedersen and Hoffmann Thomsen Citation2005). Similarly, evidence from the Dutch case provided by Otjes and Louwerse (Citation2014) suggests that a minority cabinet may be even less inclusive than its majoritarian counterpart. As to the flexibility of legislative coalition-building, we are not aware of any studies that compare the performance of different cabinet types.

This paper contributes to the literature by studying legislative coalition-building in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), Germany’s most populous state. Minority cabinets are rare in Germany, partly due to demanding investiture rules (Ganghof and Stecker Citation2015). However, after the most recent federal election in 2017 an intense public debate on the potential advantages of a minority cabinet took place, especially with respect to the flexibility of legislative coalition-building. Significant resistance to such a cabinet emerged, however, and eventually a ‘Grand’ coalition of Social and Christian Democrats was formed once again. One of the few instances in which a minority cabinet did form is the coalition of Social Democrats and Greens in NRW between 2010 and 2012.Footnote1 This cabinet is the focus of our study.

To study the inclusiveness of legislative coalition-building in NRW, we analyze a novel data set covering all 1028 bills passed in 30 years (from 1985 to 2017) of legislative politics in NRW. We show that once a long-term perspective is adopted, there is no evidence that the minority cabinet governed more inclusively. Instead, we show that inclusiveness increases with the ‘technical’ or non-political nature of a bill and decreases with a certain pattern of cabinet alternation. Based on our data, we reject the inclusiveness hypothesis, which is assumed by important studies in comparative politics.

To study the flexibility of legislative coalition-building under the minority cabinet in NRW, we collected detailed data on the positions of parties, proposals and the status quo along different policy dimensions. We show that, given the configuration of party positions and status quo locations, the standard spatial model with purely policy-seeking parties would predict no shifting legislative coalitions whatsoever (e.g. Tsebelis Citation2002). Yet, while the minority cabinet did rely mostly on the Left Party to pass legislation, it did sometimes build legislative coalitions exclusively with the opposition parties to its right. To explain this pattern, we advance a flexibility hypothesis that departs from the standard model and highlights the number of minimal winning coalitions the government can build to shift the status quo in its desired direction. As this number increases, so does the likelihood of shifting legislative coalitions. When the right-leaning opposition parties wanted to maintain the status quo or shift policies in the opposite direction, the government had to rely on the Left Party for support. In contrast, when Christian Democrats and Liberals agreed with the government at least on the desirable direction of policy change, shifting legislative coalitions became possible.

The discussion proceeds as follows. Sections 2 and 3 specify our theoretical expectations about inclusiveness and flexibility, respectively. Section 4 elaborates on our case and presents the data. Sections 5 and 6 conduct our empirical analyses of inclusiveness and flexibility, respectively. In both sections we complement our quantitative results with qualitative case studies. Section 7 discusses the results.

THEORY: INCLUSIVENESS

This section distinguishes two competing views on whether or not the majority status of cabinets affects the inclusiveness of legislative coalitions. One of these views will inform the causal hypothesis to be tested, the other provides a substantive interpretation of the null hypothesis.

Two notions of inclusiveness can be distinguished. According to a broader and more majoritarian notion of inclusiveness, every opposition party can become part of every potential legislative majority on a particular bill. This notion is consistent with the actually realized legislative coalitions being minimal-winning, i.e. including only the minimal number of parties required for a legislative majority. Inclusiveness in this sense can still be high when minimal-winning coalitions form with changing parties across a legislative term. Indeed, this notion of inclusiveness is very close to the idea of legislative flexibility that we discuss in the next section. Here we want to focus on the narrower and more ‘consensual’ notion of inclusiveness, according to which inclusiveness is maximised when all parties are in fact included in the legislative coalition on every bill. Inclusiveness in this sense can be measured by the share of legislation passed by oversized or all-party coalitions or by the average share of voters represented in legislative coalitions.

There are two competing views on how minority cabinets affect inclusiveness in this narrower sense. One assumes that minority cabinets tend to lead to more inclusive legislative coalitions. For example, Lijphart’s (Citation2012) highly influential study on comparative patterns of democracy treats minority coalitions as being as ‘consensual’ as oversized cabinets. Some authors in the same tradition even consider all minority cabinets, including single-party governments, to be as consensual as oversized cabinets (Bernauer, Giger, and Vatter Citation2014). Other studies make similar assumptions (Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2006; Giuliani Citation2008; Freitag and Vatter Citation2009; Vatter and Bernauer Citation2009). However, neither of these studies tests these assumptions or specifies causal mechanisms that could connect cabinets’ minority status to oversized legislative coalitions. One such mechanism has been suggested by Christiansen and Seeberg (Citation2016), who argue that cabinets tend to seek broader support in order to reduce public criticism of their proposals. It remains somewhat unclear, however, why similar incentives do not exist for majority cabinets (Christiansen and Seeberg Citation2016, 1176).

A rival perspective suggests that the legislative inclusiveness we see in countries like Denmark is not due to the prevalence of minority cabinets but to deeper causes, most notably a fragmented and multi-dimensional party system. This rival perspective holds that if majority cabinets form in highly fragmented parliaments with a multidimensional structure of partisan preferences, they face very similar incentives for inclusive and consensus-seeking behaviour.

For example, McGann and Latner (Citation2013, 830–832) argue that in a multi-party parliamentary system like Denmark, even majority cabinets might have an incentive to seek broader consensus and take into account the policy preferences of opposition parties. The causal mechanism suggested here is that opposition parties have the ability to split the existing portfolio coalition by offering one or more of its members favourable terms to join an alternative majority coalition. Hence: ‘We would expect majority-rule bargaining to often produce outcomes that are consensual in the sense that all or most participants find them broadly acceptable’ (McGann and Latner Citation2013, 832). This perspective would lead us to expect no systematic differences in the legislative inclusiveness under different cabinet types, once we control for the format of party system (the effective number of parties and multidimensionality of party preferences).

Existing empirical studies do not discriminate clearly between these rival views. Consider two recent examples. Christiansen and Pedersen (Citation2014) compare the only post-1973 majority cabinet in Denmark (in office from 1993 to 1994) to two minority cabinets. They investigate the extent to which these cabinets rely on their own ‘bloc majorities’ when passing bills rather than seeking cooperation with at least one party from the competing bloc. They find that the majority government was slightly less likely to rely solely on its majority within its own political bloc than the two minority cabinets. There is thus no evidence that majority cabinets are less inclusive at the legislative stage. Louwerse et al. (Citation2017) study the legislative cooperation between cabinets and opposition parties in the Netherlands and Sweden and find that a cabinet’s minority status has a positive effect on this cooperation. They note, however, that a large part of this effect is purely mechanical: minority cabinets simply need at least one additional support party to pass legislation, so that this analysis tells us little about the difference in inclusiveness between majority and minority cabinets.

While we find the second view described above more plausible, we treat it as the null hypothesis for the purpose of our analysis. It is tested against the following hypothesis derived from the first view:

Inclusiveness hypothesis: Minority cabinets are more likely to build inclusive legislative coalitions than majority cabinets, everything else being equal.

THEORY: FLEXIBILITY

This section starts from the observation that the standard spatial models used in influential theories such as veto player theory cannot explain why some minority governments build shifting legislative coalitions. To explain these cases, we gather and combine a number of theoretical arguments advanced in the relevant literature and derive a testable hypothesis for the case of the NRW minority cabinet.

Our discussion is restricted to ‘substantive’ minority cabinets (Strøm Citation1990, 62). Merely ‘formal’ minority cabinets rely on stable support from at least one opposition party in parliament, which becomes a ‘veto player’ on all bills (Strøm Citation1990, 97–99; Tsebelis Citation2002).Footnote2 The possibility of shifting coalitions is thus limited.

The standard spatial model of legislative politics assumes that parties are pure policy seekers and that all relevant aspects of their choice situation are exogenously fixed. From this perspective, whether or not a minority cabinet governs with shifting legislative coalitions depends on the configuration of parties’ policy preferences as well as the cabinets’ agenda-setting power. For example, Tsebelis (Citation2002, 97–99) argues that if party preferences are two- or multi-dimensional and the minority cabinet consists of a single party and this party is located in the centre of the policy space and possesses agenda-setting power, it may choose among different parties to support its various bills and prevent alternative majorities. The cabinet’s flexibility in choosing support parties then allows it to govern without the need for making substantial concessions to opposition parties (cf. also Thomson et al. Citation2017; Matthiess Citation2019).

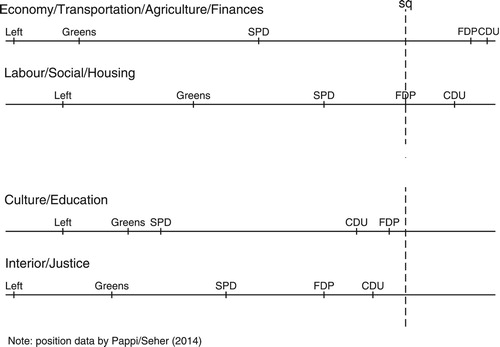

However, this view also implies that under different conditions, minority cabinets are unlikely to govern with shifting legislative coalitions. To illustrate this, shows parties’ policy preferences and the status quo in four distinct policy dimensions during the NRW minority government. Party position data are taken from Pappi and Seher (Citation2014), who apply the wordfish method to manifestos of German subnational parties.Footnote3 The figure shows that parties’ preferences are highly correlated across policy dimensions. The SPD-Green minority cabinet included the median representative and needed only a single seat for a majority, so that the support of any of the three opposition parties (CDU, FDP or Left Party) was sufficient. Based on the assumptions of the standard spatial model and the position of the status quo, the minority government had no reason to ever seek support from the opposition parties on its right. It could always rely on the Left Party, which is assumed to offer its support for any policy to the left of the status quo. Hence, for our case of the NRW minority cabinet, the standard spatial model actually predicts no shifting legislative coalitions. It predicts that the government predominantly relied on the support of the Left Party.

Yet we know this ‘prediction’ to be wrong. As we will show below, the NRW minority cabinet excluded the Left Party on a number of important bills and sought the support of the parties to its right. How can this be explained? The existing literature makes a number of suggestions, which we will review in order to derive a testable hypothesis for the case of NRW.

First, a substantial literature suggests that parties do not behave as pure policy-seekers in legislative coalition-building (e.g. Klüver and Zubek Citation2017; Angelova et al. Citation2018). A basic idea is that a potential support party like the Left Party in NRW may be able to credibly threaten to vote against the government’s proposal. This threat is based on this party’s belief that if policy is not moved sufficiently in its direction, it may suffer a relative disadvantage in electoral competition. The potential support party may thus be less ‘accommodative’ than the standard model assumes (Ganghof and Bräuninger Citation2006). The resulting decrease in the win-set of the centre-left coalition may force the government to make concessions – up to a point where building a legislative coalition with the right-leaning opposition parties becomes equally or even more attractive.

Second, the right-leaning parties might, of course, also try to issue a veto threat, based on electoral considerations as well as their closeness to the status quo. However, once we assume that the credibility of veto threats is not based on parties’ policy positions alone, the availability of alternative coalition-building options may itself increase the governments’ bargaining power and reduce opposition parties’ demands. All opposition parties have to take into account the fact that their own refusal of a government proposal might not be an effective way to protect the status quo, but may likely lead to an alternative legislative majority that moves policy further away from their own policy preference. Hence, if an opposition party expects a ‘reversion policy’ that is substantially less attractive than the status quo, it will be more willing to compromise with the government.

Third, in many parliamentary systems, governments can threaten to dissolve parliament (Goplerud and Schleiter Citation2016). This is important because it creates an additional uncertainty about the policy that will be implemented after a potential election (Becher Citation2012). Moreover, the threat of a new election is most effective against those opposition parties that are doing badly in the polls when the negotiations with the government take place (Becher and Christiansen Citation2015; see also Green-Pedersen, Mortensen, and So Citation2018). Since the vulnerability of opposition parties to the dissolution threat may vary over time and across issues, this threat may increase the likelihood of shifting legislative coalitions, even in an essentially unidimensional policy space.

Fourth, the government may also have more substantive reasons to sometimes seek agreement with the opposition parties that are closer to the status quo. One is the goal of achieving longer-term policy stability (cf. Tommasi, Scartascini, and Stein Citation2014). The government may grant greater concessions to a major opposition party on the right in order to achieve greater long-term policy stability in return. This consensus may also be a legal necessity, when certain parts of a reform require constitutional change and hence legislative supermajorities.

The existing literature has not yet produced a comprehensive theory that shows how these theoretical ideas can be reconciled with the insights of the standard model. Our modest goal here is to formulate a testable hypothesis that is informed by these ideas and contradicts the standard model. This hypothesis focuses on an important difference between the upper two and the lower two policy dimensions in : in the latter, the two opposition parties to the right of the government prefer a policy change in the same direction as the government. We expect this constellation to make a centre-right coalition that excludes the Left Party more likely. When the stance of the Left Party becomes sufficiently non-accommodative while the parties to the right are sufficiently accommodative, a centre-right coalition can be the better choice for the government. In contrast, when the right parties want to change the status quo in the opposite direction, it seems unlikely that this policy preference can be outweighed by other motivations. We thus state the following hypothesis.

Flexibility hypothesis: The higher the number of winning coalitions that want to change the status quo in the same direction as the minority cabinet, the greater the likelihood of shifting legislative coalitions.

DATA

This section first introduces the case of NRW, then elaborates on the construction of our data set and finally explains our method for distinguishing ‘technical’ from ‘political’ bills.

The Case of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW)

NRW uses a unicameral parliamentary system. As shown in , during the period under consideration (1985–2017), the effective number of parties has been comparatively moderate. It slowly increased from 2.2 to 3.5 parliamentary parties. The case thus provides a useful contrast to cases with greater party system fragmentation such as Denmark. In line with our theoretical discussion on inclusiveness, we will control for the effective number of parties in order to distinguish a potential causal effect of cabinets’ majority status from the incentives emerging from the party system.

Table 1 LEGISLATIVE TERMS AND GOVERNMENTS IN NRW SINCE 1985

When analyzing the flexibility hypothesis, the focus will be on the ‘Red-Green’ minority cabinet of Social Democrats and Greens that governed from 2010 to 2012. This cabinet stated its intention to govern with flexible majorities and abstained from negotiating any formal or informal agreements with potential support parties. All opposition parties signalled their willingness to conditionally support specific pieces of legislation. In March 2012 the government broke down prematurely after an unexpected bargaining failure over the state budget, and was replaced by a Red-Green majority cabinet after early elections ().Footnote4

Since the governments’ dissolution power plays a role in our theoretical argument, it is useful to note that the NRW constitution at the time provided for two ways to force early elections (Reutter Citation2014, 52). First, an absolute majority in parliament could vote for parliamentary dissolution (article 35(1)). Second, until 2016 the government could also initiate a referendum on any bill that failed to get majority support in parliament (article 68(3)). A successful referendum would have allowed the government to unilaterally dissolve parliament, while losing the referendum would have forced the government to resign. In 2016, as part of a larger revision of the constitution, this second path towards parliamentary dissolution was removed.

A Data set on ‘Technical’ and ‘Political’ Bills

We constructed a novel data set covering more than 30 years of legislative politics in NRW (1985–2017). We used web-scraping and pattern-matching scripts implemented in R to harvest information on all passed bills including the introducing actors, descriptors for the affected policy areas, the length of plenary debates and the formation of legislative coalitions. This data enables us to compare legislative coalitions under the minority cabinet to six other legislative terms that were governed by minimal winning coalitions. Altogether, we analyze 1028 approved bills, including 243 bills of the latest, 16th term (2012–2017), during which the party system is most similar to that of the time of the minority cabinet.

To test the flexibility hypothesis, we add more fine-grained qualitative data on the positions of parties, proposals and the status quo for the period of the minority cabinet in office. We read plenary protocols and committee reports to qualitatively analyze the 59 bills that were passed during the minority government’s term.

When analyzing legislative coalition formation, a possible source of bias might be differences in the ‘technicality’ of bills. Many bills concern technical matters with limited scope for political disagreements. Examples include adaptations to new court rulings or European law and the consolidation of terminable laws. For the 59 bills that were approved during the minority government’s term, we qualitatively identified 25 ‘technical’ bills and coded the remaining 34 as ‘political’.Footnote5

For a comparison of legislative coalition-building covering the entire period under consideration, the qualitative coding of bills becomes impractical. Hence we propose a quantitative indicator based on the length of the public debate during a bill’s parliamentary reading. We use the length of the longer of the two readings, measured in pages in the parliamentary protocol, to approximate the technicality of a bill. The length of debates is agreed upon in the steering committee of parliament, usually in a consensus among all parties. A substantial debate thus indicates that at least one party attaches importance to a matter and wants its position to be publicly presented in parliament.

For some of the following tests we transform this indicator into a dummy variable. It deems all bills ‘technical’ for which number of pages in the protocols does not exceed four. We determined this threshold by estimating a logit model that predicts our qualitative coding of the 15th term’s 59 cases based on the length of their respective parliamentary debates. This analysis shows that as the page lengths surpasses the value of 4.5, the probability that a bill is qualitatively coded as non-technical exceeds 50 per cent. Our qualitative and quantitative derived dummy variables agree in 50 of 59 cases on the classification of a bill as ‘technical’ or ‘political’.Footnote6 The correlation coefficient is .69 for the page lengths and .70 for the transformed dummy variable (N = 59).

EVIDENCE: INCLUSIVENESS

This section shows that our data does not support the inclusiveness hypothesis. Controlling for other factors, the minority cabinet in NRW did not build more inclusive legislative coalitions than the minimal-winning cabinets that preceded and followed it. We first present our quantitative evidence and then illustrate the argument by taking a closer look at an important bill on the integration of immigrants.

Quantitative Evidence

There are different plausible ways to operationalise legislative inclusiveness (Müller and Jenny Citation2004; Williams Citation2012). Studies interested in the quality of representation might opt for popular legislative inclusiveness, that is, the combined vote share of parties included in a legislative winning coalition. As we are more interested in parties’ coalition-building incentives than in their relative seat shares, we operationalise inclusiveness mainly as the share of oversized coalitions that formed during the final vote on a bill. However, our findings are corroborated by robustness tests based on other measures (see online appendix).

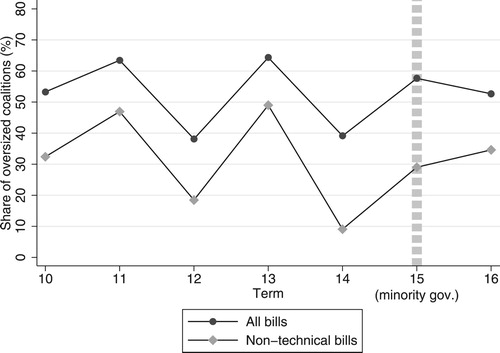

Under the minority cabinet, the majority of bills (34 of 59, or 58 per cent) were passed by oversized coalitions.Footnote7 If one takes a short-term perspective and compares this share of oversized coalitions only to the respective shares under the minimal-winning coalitions that preceded and followed the minority cabinet (39 and 53 per cent, respectively), the minority cabinet seems more inclusive. A longer-term view shows a different picture, though (). The share of oversized coalitions is higher in two of the terms with minimal-winning cabinets (terms 11 and 13). During the 13th term around 65 per cent of bills were passed by oversized coalitions. The picture becomes even more pronounced when we exclude technical bills (square markers in ). Now the share of oversized coalitions during the term of the minority government is lower compared to four of the six minimal-winning cabinets. These patterns do not support the inclusiveness hypothesis.

We can test for the effect of the cabinet’s minority status more formally by building a logit model of the 1028 bills passed from 1986 to 2017 (). Our dependent variable is a dummy that indicates the formation of an oversized legislative coalition. Our central explanatory variable Minority government is 1 for those bills that were passed during a minority government and 0 otherwise. We control for the Effective Number of Parties, since a more fragmented party system might make oversized coalitions more likely (Volden and Carrubba Citation2004; McGann and Latner Citation2013). We also include a dummy variable, anti-hegemonic alternation, for the CDU/FDP majority government during the 14th term. Since this cabinet implied a complete change of cabinet parties after three decades of social-democratic rule (either alone or with the Greens), it was likely to face a rather undesirable status quo along many issue-dimensions and hence to govern more exclusively. Finally, we control for a bill’s technicality, based on the logged length of the debate of the first or second reading (whichever one was longer). Technical bills are more likely to be passed with broad support.

Table 2 THE EFFECT OF THE MINORITY STATUS ON LEGISLATIVE INCLUSIVENESS

The results confirm the visual impression in . There is no significant effect of the minority government on inclusiveness. Contrary to our expectations, the effect of party system fragmentation on the formation of oversized legislative coalitions is also zero or negative, depending on the choice of control variables. As expected, the technicality of a bill increases inclusiveness and anti-hegemonic alternation reduces it.Footnote8 All in all, our quantitative analysis does not support the inclusiveness hypothesis: the minority cabinet was not more inclusive than the minimal winning cabinets before and after.

Of course, given that we analyze only a single case (NRW) with a single instance of a minority government, our ability to generalise beyond this case is very limited. The point of our analysis was not to estimate the size of some general casual effect as precisely as possible, but to comparatively test the explanatory power of the two competing theoretical views when applied to the minority government under investigation. The evidence provided here certainly cannot ‘refute’ the inclusiveness hypothesis but calls it into question.

Qualitative Evidence

What distinguishes the two theoretical views is not that one of them denies incentives for inclusive or consensus-seeking behaviour of cabinets in parliament. Instead, one view simply assumes that this behaviour is as likely to exist under minority and majority cabinets, everything else being equal. To illustrate this point, it is useful to take a closer qualitative look at a specific case of inclusive lawmaking. One of the most important bills that was passed consensually under the minority government was the Integration Law (‘Integrationsgesetz’, cf. Morfeld Citation2015, 66). It was also the most debated (i.e. clearly non-‘technical’) bill that was decided consensually.Footnote9 The bill merged preexisting integration-policy guidelines of the government and created some new provisions for the integration of immigrants.

From a short-term perspective, the Integration Bill might be misinterpreted as evidence for particularly inclusive decision-making under minority cabinets. Already during her inauguration speech, Prime Minister Hannelore Kraft referred to the bill as central to her ‘coalition of invitations’ and stressed the hope to find broad parliamentary support (Plenary protocol Citation15/Citation36, 3621). This consensus-oriented style was maintained during the extra-parliamentary preparation of the bill as well as during the parliamentary negotiations. It involved various compromises on the side of the governing coalition as well as on the side of the opposition parties, e.g. on the issue of discrimination and the involvement of migrant organisations (Plenary protocol Citation13/Citation42, 4566). While an amendment of the Left Party was rejected, some of its demands were incorporated into the bill during the committee stage (Plenary protocol Citation15/Citation45, 5514).

As in our quantitative analysis, however, we need to take a long-term perspective. In fact, the consensual style of policy-making on integration policy had been long-established by the time the minority cabinet came into office. Already in 2001, under a Red-Green majority cabinet and in response to an initiative of the oppositional CDU, all parliamentary parties had agreed to start an ‘integration offensive’ (Integrationsoffensive, Burger Citation2010, 5; Plenary protocol Citation15/Citation54, 3619). This integration policy consensus reflected the strong will of all parties to achieve a lasting political and social compromise on integration, continuing disagreements notwithstanding (Plenary protocol Citation15/Citation45, 4143; Burger Citation2010).

In the debate on the Integration Law, all parties stressed that it was a continuation of the existing compromise. Indeed, large parts of the bill already had been prepared under the previous CDU-FDP coalition (Plenary protocol Citation13/Citation42, 4564). Thus the bill cannot serve as an example of how minority cabinets foster inclusiveness. It rather shows that strong incentives for consensus-seeking may also exist when majority cabinets are in place.

EVIDENCE: FLEXIBILITY

This section tests the flexibility hypothesis, which states that shifting legislative coalitions become more likely as the number of winning legislative coalitions that the government can form to change the status quo in the desired direction increases. We find some support for this hypothesis based on quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Quantitative Evidence

As already established in section 3, the configuration of party preferences was essentially unidimensional, and in all policy dimensions the status quo was located to the right of the government. Based on the insights of the standard spatial model, therefore, the potential for shifting legislative coalitions was quite limited under the minority cabinet in NRW. In line with these insights, our qualitative coding of the direction of policy change revealed that each and every bill passed during the term of the minority governments moved the SQ to the left, and that the government relied mainly on the Left Party to implement its agenda. This party was excluded from legislative coalitions in only 15 percent of the non-technical bills (5 of 33).

On the other hand, the fact that other legislative coalitions did form on some bills shows that the standard spatial model cannot be the whole story. The question thus becomes: Can the flexibility hypothesis help us explain the patterns of legislative coalition formation? Based on this hypothesis, we can distinguish two pairs of policy dimensions (see above):

High flexibility: On Culture/Education and Interior/Justice all three opposition parties are located left of the status quo. Hence the government could choose between three winning coalitions for moving the status quo in its desired direction.

Low flexibility. On Economy and Labour/Social/Housing, in contrast, neither CDU nor FDP were interested in any move towards the SPD/Green government. Based on the measured policy preferences, therefore, there was only one winning coalition, with the Left Party, possible for changing the status quo in the desired direction.

relates the degree of flexibility (low or high) to the different kind of coalitions formed. It focuses exclusively on political bills and neglects those classified as ‘technical’. On the dimensions with low flexibility, each and every bill was passed with the support of the Left Party. This is in line with the flexibility hypothesis. For 69 percent of bills, the government had to rule with the sole support of the Left Party, for 31 percent there was additional support from one or both of the parties on the right. For the dimensions with high flexibility, the picture looks decidedly different. Most importantly, 25 percent of the bills were passed with a legislative coalition that excluded the Left Party. The fact that the parties to the right of the government wanted to move a policy in the same direction as the government seems to have facilitated agreement. In line with this interpretation, the share of bills passed with the sole support of the Left Party is cut in half (35 percent).

Table 3 FLEXIBILITY OF THE GOVERNMENT AND LAW MAKING

We can test for a difference between high and low flexibility more formally. Two sample t-tests show that when flexibility is high, there are significantly fewer bills passed exclusively with the left (p = .029) and significantly more bills passed without the left (p = .026). Another way to test the flexibility hypothesis is a two sample proportions test. Here, the proportion of those bills passed exclusively with the Left Party to those exclusively passed with parties on the right is significantly higher (and closer to 1) when flexibility is low (p = 0.0001, z = 4.05). All in all, these tests support the flexibility hypothesis.

Qualitative Evidence

Again, we want to use qualitative evidence to provide insights into some of the relevant causal mechanisms. We provide two brief illustrative case studies of individual bills, the bill on local budgets (Stärkungspaktgesetz) and the arguably most important legislation during the minority government’s term, the so-called ‘school peace’ (Schulfrieden). Both bills belong to dimensions with high flexibility, Interior/Justice and Culture/Education, respectively (see ).Footnote10 In both cases, the Left Party was excluded from the winning coalition.

The local budgets bill aimed at stabilising the budgets of municipalities in NRW by combining expenditure cuts and grants from the state government. When the minority cabinet took office, many cities and municipalities were heavily indebted due to a vicious circle of falling employment and increasing social expenditures set in motion by the decline of heavy industries in the Land. The municipal debt per capita amounted to 3200€ and was growing by 133€ per year. The government wanted to combine carrots and sticks for over-indebted municipalities. On the one hand, municipalities were to receive about 350 million Euro for ten years, on the other hand they had to implement far-reaching reforms to consolidate their budgets.

The original draft bill of the government met with unanimous refusal by all opposition parties. Most importantly, the Left Party made its support dependent on an amendment that would increase the financial support from the state and demanded only moderate cuts to the municipalities’ budgets. The Left Party suggested funding these measures with a debt relief at the expense of banks and private creditors as well as with a new wealth tax (Drucksache Citation15/Citation2849; Drucksache Citation15/Citation2848). In other words, the Left Party adopted a rather ‘non-accommodative’ stance (Ganghof and Bräuninger Citation2006) and demanded a substantial leftward shift of the governments’ policy proposal. In the absence of alternative support partners, the government might have been forced to concede this shift.

As suggests, however, the Liberals were a potential support party to the right of the Social Democrats. They wanted a rightward shift of the governments’ proposal, but a fairly moderate one, in the form of a tighter monitoring mechanism and a limit to the bills’ redistributive effects between rich and poor municipalities. Observers suggest that the Liberals compromising stance was facilitated by the threat of early elections in combination with weak poll results.Footnote11 A legislative amendment incorporated the compromise with the Liberals into the bill and was finally passed against the votes of CDU and Left Party.

Our second example is the so-called ‘school peace’ (Schulfrieden), a bill that passed with the support of the Christian Democrats. Education policy is one of the major conflict lines in the politics of the German states (Wolf and Kraemer Citation2012). While left-leaning parties favour a more egalitarian school system, Christian Democrats and Liberals prefer greater differentiation of pupils at an early age. The minority cabinet in NRW wanted to merge these different types into a comprehensive school (Gemeinschaftsschule), whereas the position of the CDU was fairly close to the status quo of a three-tier school system of Haupt-, Realschule, and Gymnasium. As suggests, however, the CDU did not want to move the status quo in the opposite direction, but was open to limited change in the preferred direction of the government. More specifically, the CDU leadership was under intense pressure from its local party organisations to move towards the government’s position. Due to an overall shrinking number of pupils and a low demand for the low-tier school type, the Hauptschule, many municipalities favoured the introduction of a more comprehensive school system (Morfeld Citation2015, 108–109).

This basic agreement between the government and the CDU on the direction of policy change was reinforced by a number of additional factors. First, the CDU had to consider the possibility that the government could strike a deal with the Left Party, which would have implied a considerable policy loss for the CDU. Second, the government knew that parts of the reform needed constitutional changes and hence the CDU’s consent. Finally, both sides were aware that any reform passed against the wishes of either of the large parties, SPD or CDU, was likely to be unstable in the medium to long term.

In the end, therefore, the minority government and the CDU quickly agreed on the terms of a far-reaching reform of the school system (Morfeld Citation2015, 103). The constitutional guarantee of the lowest-tier school type was removed and a new type of school was introduced that comprised elements of the middle- and high-tier schools. In choosing the exact degree of differentiation between pupils much discretion was granted to municipalities and individual schools.

DISCUSSION

Political scientists’ perspectives on minority cabinets have changed considerably. Once almost invariably seen as a crisis phenomenon, they are now often regarded as a particularly attractive form of governance. Yet our analysis of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, suggests that the advantages of minority cabinets can easily be exaggerated.

As to the inclusiveness of legislative coalitions, we have found no evidence that the majority status of cabinets makes a difference. While we cannot generalise from this one case, we noted from the outset that the inclusiveness of minority cabinets has more often been assumed than demonstrated. We have also given theoretical reasons to believe that the cabinet type might be less important for the inclusiveness of decision-making than the structural context – most notably with respect to the party system – in which coalition-formation takes place. More systematic and comparative empirical research is needed to properly evaluate whether and under what conditions minority cabinets govern in a more inclusive manner.

As to the flexibility of legislative decision-making, our findings are more nuanced. One the one hand, our analysis corroborates a basic insight of the standard spatial model: If the policy space is essentially unidimensional and the government wants to move policy consistently in one direction, the potential for shifting legislative coalitions is quite limited. 85 percent of the non-technical bills passed under the minority cabinet in NRW were supported by the Left Party. This finding qualifies the arguments that (substantive) minority cabinets govern in a more flexible manner. The attractiveness of governing with shifting legislative coalitions may increase, as the legislative party system becomes more fragmented and multidimensional. Yet, greater fragmentation also makes the formation of single-party minority cabinets less likely (Taagepera Citation2002). Since each cabinet party then becomes a veto player, and since more veto players may also reduce the value of agenda-setting powers, median outcomes are far from guaranteed (see also Martin and Vanberg Citation2014). This finding also implies that if governing with shifting, median-oriented legislative coalitions is seen as a normative priority, it might provide a reason to consider alternatives to a pure parliamentary system of government such as presidential or ‘semi-parliamentary’ government (see Ganghof Citation2018; Ganghof, Eppner, and Pörschke Citation2018).

On the other hand, we have provided evidence that there is a degree of flexibility in legislative coalition-building even when the configuration of party preferences is essentially one-dimensional and the minority government wants to consistently shift the status quo in one direction. Governments seem more likely to govern with shifting legislative coalitions, the higher the number of support parties (with sufficient seats) on the same side of the status quo. We have suggested that to make theoretical sense of this finding, we need to move away from the standard spatial model with its assumption of purely policy-seeking parties. In contradiction to this model, minority cabinets are willing to compromise with opposition parties that want to limit policy change because none of the opposition parties typically offers its support without demanding concessions. An important question for further theoretical analysis is how this insight might be reconciled with the insights of the standard model.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA AND RESEARCH MATERIALS

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2019.1635120

Supplemental Material_Appendix

Download MS Word (103.5 KB)ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Steffen Ganghof is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Potsdam. His research focuses on democratic theory, political institutions and political economy. His articles have appeared in the British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, and the European Journal of Political Research, among others.

Sebastian Eppner is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Department of Social Sciences and Economics, University of Potsdam. His research focuses on political institutions, party competition and democratic representation in advanced democracies as well as quantitative research methods.

Christian Stecker is a postdoctoral researcher at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research. His research focuses on the design of democratic institutions, party competition and legislative politics. His work has been published in journals such as the European Journal of Political Research, Political Analysis, Party Politics, and West European Politics.

Katja Heeß was a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for the Study of Democracy at Leuphana University Lüneburg. Her research focuses on political institutions and their development. In her dissertation she analysed institutional change of legislative veto points in parliamentary democracies.

Stefan Schukraft was a research fellow at the Chair of Comparative Politics, University of Potsdam. He wrote his PhD thesis about patterns of legislative conflict in the German Länder.

ORCID

Christian Stecker http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9577-7151

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Other notable instances of minority governments in Germany are the two SPD-led minority governments that ruled Saxony-Anhalt between 1994 and 2002.

2 Strøm’s (Citation1990, 62) definition of formal minority cabinets also entails that parliamentary support ‘(1) was negotiated prior to the formation of the government, and (2) takes the form of an explicit, comprehensive, and more than short-term commitment to the policies as well as the survival of the government’. We discuss elsewhere (Ganghof and Stecker Citation2015), that it is useful to differentiate between the types of legislative coalitions minority cabinets build and how these types are institutionalised in long-term agreements or ad-hoc-coordination (see also Bale and Bergman Citation2006a, Citation2006b).

3 We like to thank Franz Urban Pappi for kindly providing his data on party positions and saliences in North Rhine-Westphalia. The grouping of issues into raw dimensions was done by Pappi and Seher (Citation2014). We exclude a fifth dimension (environment), because no non-technical bill was passed during the minority government’s term that would fit into that category. We use the previous government’s position as an approximation of the status quo. The positions are normalised using the status quo on each dimension.

4 It remains controversial how actively the Red-Green government provoked this bargaining failure in order to trigger early elections (Goos Citation2012; Morfeld Citation2015, 141–144; Pfafferott Citation2018, 334–348).

5 One third of those bills adapted state laws to new European and federal rulings. Another third consolidated terminable laws without further controversy. Two further bills regulated the organisation of parliament, which is usually done with a broad consensus between parties. We treat the (more heated) discussions about the increase of allowances for members of parliament as non-technical. Examples of other bills we deemed technical included a bill that made it possible for cities to name themselves ‘University town’ on their official town signs or a bill that introduced a new accounting system in certain areas of the administration.

6 Morfeld (Citation2015, 66) quantitatively identified a list of 15 key bills that were passed during the minority government's term. All of those key bills have been classified as non-technical or political by both our qualitative and quantitative indicators. This increases our trust in our indicators’ ability to effectively get rid of purely technical bills while not falsely identifying political bills as technical.

7 If we count abstaining parties as supporters, 38 (64 per cent) of coalitions are oversized.

8 Our main results are robust to an alternative treatment of abstentions. If we count abstentions as support, the inclusiveness of the minority government is even significantly smaller than that of majority governments based on model 3.

9 ‘Consensual’ here means the absence of any nay votes.

10 One might argue that the first of these two bills belongs into the ‘finance’ category. However, the responsible department was the department of the interior and the main committee was the municipal committee. Indeed, the bill is as much about financial aid to communes as it shapes the powers of communes versus the Land (‘kommunale Selbstverwaltung’). More importantly, our qualitative study confirms that parties actual policy positions are better approximated by the estimated positions along the ‘interior’ dimension, with the FDP being positioned to the left of the status quo.

11 There are other examples for the importance of the early election threat (Burger Citation2011). One is the abolition of University tuition fees. Whereas the government planned to abolish them only from the winter term 2011/2012, the Left Party pushed for an immediate abolition. The government had to withdraw a motion which planned to delay the abolition because the Left Party refused to support it. Just before another vote, the prime minister threatened the Left Party with early elections. As this party polled less than the 5 per cent of votes necessary to gain any seats in parliament, it eventually agreed on the delayed abolition.

References

- Angelova, M., H. Bäck, W. C. Müller, and D. Strobl. 2018. “Veto Player Theory and Reform Making in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 282–307. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12226

- Bale, T., and T. Bergman. 2006a. “Captives No Longer, but Servants Still? Contract Parliamentarism and the New Minority Governance in Sweden and New Zealand.” Government and Opposition 41 (3): 422–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2006.00186.x

- Bale, T., and T. Bergman. 2006b. “A Taste of Honey Is Worse Than None at All? Coping with the Generic Challenges of Support Party Status in Sweden and New Zealand.” Party Politics 12 (2): 189–202. doi: 10.1177/1354068806061337

- Becher, M. 2012. “Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Redistribution.” General Conference of the European political Science Association, Berlin, Germany.

- Becher, M., and F. J. Christiansen. 2015. “Dissolution Threats and Legislative Bargaining.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 641–655. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12146

- Bernauer, J., N. Giger, and A. Vatter. 2014. “New Patterns of Democracy in the Countries of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2.” In Elections and Democracy: Representation and Accountability, edited by Jacques Thomassen, 20–37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burger, R. 2010. “Der Aufstieg des netten Herrn Laschet.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 28 March, 5.

- Burger, R. 2011. “Ultraflexibel statt ultraorthodox.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 11 October, 4.

- Cheibub, J. A., A. Przeworski, and S. M. Saiegh. 2004. “Government Coalitions and Legislative Success Under Presidentialism and Parliamentarism.” British Journal of Political Science 34 (4): 565–587. doi: 10.1017/S0007123404000195

- Christiansen, F. J., and H. H. Pedersen. 2014. “Minority Coalition Governance in Denmark.” Party Politics 20 (6): 940–949. doi: 10.1177/1354068812462924

- Christiansen, F. J., and H. B. Seeberg. 2016. “Cooperation between Counterparts in Parliament from an Agenda-Setting Perspective: Legislative Coalitions as a Trade of Criticism and Policy.” West European Politics 39 (6): 1160–1180. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1157744

- De Giorgi, E., and G. Ilonszki. 2018. Opposition Parties in European Legislatures: Conflict or Consensus?, Routledge Studies on Political Parties and Party Systems. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Drucksache 15/2848. 2011. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument/MMD15-2848.pdf.

- Drucksache 15/2849. 2011. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument/MMD15-2849.pdf.

- Field, B. N. 2016. Why Minority Governments Work: Multilevel Territorial Politics in Spain., Europe in Transition. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Freitag, M., and A. Vatter. 2009. “Patterns of Democracy: A sub-National Analysis of the German Länder.” Acta Politica 44 (4): 410–438. doi:10.1057/ap.2009.22.

- Ganghof, S. 2018. “A new Political System Model: Semi-Parliamentary Government.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 261–281. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12224

- Ganghof, S., and T. Bräuninger. 2006. “Government Status and Legislative Behaviour. Partisan Veto Players in Australia, Denmark, Finland and Germany.” Party Politics 12 (4): 521–539. doi: 10.1177/1354068806064732

- Ganghof, S., S. Eppner, and A. Pörschke. 2018. “Australian Bicameralism as Semi-Parliamentarism: Patterns of Majority Formation in 29 Democracies.” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 211–233. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2018.1451487

- Ganghof, S., and C. Stecker. 2015. “Investiture Rules in Germany: Stacking the Deck Against Minority Governments.” In Parliaments and Government Formation. Unpacking Investiture Rules, edited by Björn Erik Rasch, Shane Martin, and José Antonio Cheibub, 67–85. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Giuliani, M. 2008. “Patterns of Consensual Law-Making in the Italian Parliament.” South European Society and Politics 13 (1): 61–85. doi: 10.1080/13608740802005777

- Godbout, J.-F., and B. Høyland. 2011. “Legislative Voting in the Canadian Parliament.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 367–388. doi: 10.1017/S0008423911000175

- Goos, C. 2012. “Die Erste Landtagsauflösung in Nordrhein-Westfalen.” Bonner Rechtsjournal, no. 1: 26–30.

- Goplerud, M., and P. Schleiter. 2016. “An Index of Assembly Dissolution Powers.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (4): 427–456. doi: 10.1177/0010414015612393

- Green-Pedersen, C., P. B. Mortensen, and F. So. 2018. “The Agenda-Setting Power of the Prime Minister Party in Coalition Governments.” Political Research Quarterly. doi:10.1177/1065912918761007.

- Green-Pedersen, C., and L. Hoffmann Thomsen. 2005. “Bloc Politics vs. Broad Cooperation? The Functioning of Danish Minority Parliamentarism.” Journal of Legislative Studies 11 (2): 153–169. doi: 10.1080/13572330500158581

- Grotz, F., and T. Weber. 2012. “Party Systems and Government Stability in Central and Eastern Europe.” World Politics 64 (4): 699–740. doi: 10.1017/S0043887112000196

- Klüver, H., and R. Zubek. 2017. “Minority Governments and Legislative Reliability: Evidence From Denmark and Sweden.” Party Politics. doi:10.1177/1354068817695742.

- Lijphart, A. 1999. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- Lijphart, A. 2012. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. 2nd ed. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

- Louwerse, T., S. Otjes, D. M. Willumsen, and P. Öhberg. 2017. “Reaching Across the Aisle: Explaining Government–Opposition Voting in Parliament.” Party Politics 23 (6): 746–759. doi: 10.1177/1354068815626000

- Martin, L. W., and G. Vanberg. 2014. “Parties and Policymaking in Multiparty Governments: The Legislative Median, Ministerial Autonomy, and the Coalition Compromise.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 979–996. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12099

- Matthiess, T. 2019. “Equal Performance of Minority and Majority Coalitions? Pledge Fulfilment in the German State of NRW.” German Politics 28 (1): 123–144. doi:10.1080/09644008.2018.1528235.

- McGann, A. J., and M. Latner. 2013. “The Calculus of Consensus Democracy: Rethinking Patterns of Democracy Without Veto Players.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (7): 823–850. doi: 10.1177/0010414012463883

- Morfeld, D. 2015. Regieren im Vielparteiensystem: Das Minderheitskabinett Kraft 2010–2012 in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Vol. 23. Stuttgart: ibidem Press.

- Moury, C., and J. M. Fernandes. 2018. “Minority Governments and Pledge Fulfilment: Evidence From Portugal.” Government and Opposition 53 (2): 335–355. doi: 10.1017/gov.2016.14

- Mújica, A., and I. Sánchez-Cuenca. 2006. “Consensus and Parliamentary Opposition: The Case of Spain.” Government and Opposition 41 (1): 86–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2006.00172.x

- Müller, W. C., and M. Jenny. 2004. “"Business as usual“ mit getauschten Rollen oder Konflikt statt Konsensdemokratie? Parlamentarische Beziehungen unter der ÖVP-FPÖ-Koalition.” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 33: 309–326.

- Otjes, S., and T. Louwerse. 2014. “A Special Majority Cabinet? Supported Minority Governance and Parliamentary Behavior in the Netherlands.” World Political Science 10 (2): 343–363. doi: 10.1515/wpsr-2014-0016

- Pappi, F. U., and N. Seher. 2014. “Die Politikpositionen der deutschen Landtagsparteien und ihr Einfluss auf die Koalitionsbildung.” In Räumliche Modelle der Politik, edited by Eric Linhart, Bernhard Kittel, and André Bächtiger, 171–205. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Pech, G. 2004. “Coalition Governments Versus Minority Governments: Bargaining Power, Cohesion and Budgeting Outcomes.” Public Choice 121 (1): 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11127-004-4326-7

- Pfafferott, M. 2018. Die Ideale Minderheitsregierung. Zur Rationalität Einer Regierungsform. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Plenary protocol 13/42. 2001. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument?Id=MMP13%2F42|4125|4141.

- Plenary protocol 15/36. 2011. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument?Id=MMP15%2F36|3618|3622.

- Plenary protocol 15/45. 2011. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument?Id=MMP15%2F45|4559|4572.

- Plenary protocol 15/54. 2012. Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia. https://www.landtag.nrw.de/portal/WWW/dokumentenarchiv/Dokument?Id=MMP15%2F54|5507|5519.

- Powell, B. G. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy. Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Reutter, W. 2014. Zur Zukunft des Landesparlamentarismus: Der Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen im Bundesländervergleich. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag.

- Saalfeld, T. 2008. “Institutions, Chance, and Choices: The Dynamics of Cabinet Survival.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining, edited by Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, 327–368. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Strøm, K. 1990. Minority Government and Majority Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taagepera, R. 2002. “Implications of the Effective Number of Parties for Cabinet Formation.” Party Politics 8 (2): 227–236. doi: 10.1177/1354068802008002005

- Thomson, R., T. Royed, E. Naurin, J. Artés, R. Costello, L. Ennser-Jedenastik, M. Ferguson, et al. 2017. “The Fulfillment of Parties’ Election Pledges: A Comparative Study on the Impact of Power Sharing.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 527–542. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12313

- Tommasi, M., C. Scartascini, and E. Stein. 2014. “Veto Players and Policy Adaptability: An Intertemporal Perspective.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 26 (2): 222–248. doi: 10.1177/0951629813494486

- Tsebelis, G. 2002. Veto Players. How Political Institutions Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Vatter, A., and J. Bernauer. 2009. “The Missing Dimension of Democracy Institutional Patterns in 25 EU Member States between 1997 and 2006.” European Union Politics 10 (3): 335–359. doi:10.1177/1465116509337828.

- Volden, C., and C. J. Carrubba. 2004. “The Formation of Oversized Coalitions in Parliamentary Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (3): 521–537. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00085.x

- Ward, H., and A. Weale. 2010. “Is Rule by Majorities Special?” Political Studies 58 (1): 26–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00778.x

- Weale, A. 2018. “What’s so Good About Parliamentary Hybrids? Comment on ‘Australian Bicameralism as Semi-Parliamentarianism: Patterns of Majority Formation in 29 Democracies’” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 234–240. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2018.1451489

- Williams, B. D. 2012. “Institutional Change and Legislative Vote Consensus in New Zealand.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 37 (4): 559–574. doi:10.1111/j.1939-9162.2012.00062.x.

- Wolf, F., and A. Kraemer. 2012. “On the Electoral Relevance of Education Policy in the German Länder.” German Politics 21 (4): 444–463. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2012.740633