Abstract

During the 2019 centennial celebration of women’s suffrage in Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel conceded that gender quotas are important and that the ultimate goal must be gender parity. Merkel’s legacy in terms of advancing women within her own party, however, is mixed. Surrounding herself with a tight circle of women professionals and arguably modelling success for fellow women party members, she nonetheless remained noncommittal on parity. Her support for the ‘quorum’, a 33 per cent inner-party ‘quota light’ adopted in 1996, appeared muted and inconsequential. Throughout Merkel’s chancellorship, the CDU failed to adhere to this quota in party offices and among parliamentarians. Analysing gender-disaggregated party and electoral data with insights gleaned from semi-structured interviews with party members, this article sheds light on CDU quota implementation challenges. We assess inner-party politics and policies within the context of the CDU’s struggle to attract female voters, to respond to an increasingly progressive Women’s Union, and to accommodate its Bavarian sister party, the CSU. We find that despite a reframing of its gender equality agenda and strong inner-party mobilisation, the CDU majority still resists quotas. The mismatch between party statutes and electoral system, moreover, obstructs quota implementation, making gender parity in the CDU an elusive goal.

INTRODUCTION

Angela Merkel’s final year as Chancellor of Germany might well be entering, if not the history books, then the annals of her Christian Democratic Party (CDU) as the ‘year of the quota curse.’ First off, in summer 2020, the Chancellor’s long-time heir-apparent and leader of the CDU, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, circulated a submission to the party’s programmatic commission that, if passed by the party convention, would revolutionise the way the party selects candidates for elections as well as for inner-party positions. Replacing the CDU’s 1996 soft quota, the so-called 33 per cent ‘quorum,’Footnote1 the party would establish a set gender quota that by 2025 would reach 50 per cent for all party offices and candidate lists (CDU Citation2020, 8). A few months later, in November 2020, Merkel’s public support was crucial for passing a revised corporate board quota law – proposed by her Social Democratic Party (SPD) coalition partner – in order to address the massive underrepresentation of women on executive boards (Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 21, 2020; on labour market policies see Ahrens and Scheele, Citationthis issue).

In both cases, CDU inner-party opposition was immediate and strong, illustrating how many in the party perceive the quota as a ‘curse’ that threatens to upend party unity. When the CDU Programmatic Commission endorsed the quota for party offices and list mandates, one of Merkel’s then-potential successors, Friedrich Merz, retorted ‘I remain a sceptic: quotas are merely the second-best solution’ (Focus July 10, 2020).Footnote2 The influential CDU Mittelstandsunion (CDU Small and Medium-Size Business Association), its Wirtschaftsrat (CDU Economic Advisory Council), the CDU Student Association, as well as the Junge Union, the party’s youth association, all voiced strong opposition to the quota initiative (Focus July 10, 2020; Der Spiegel July 9, 2020). When the corporate board quota was announced, a spokesperson for the party caucus’ parliamentary CDU Mittelstandsunion argued that the quota would upend Germany’s social market economy and ultimately lead to not just large companies, but also small- and medium-sized enterprises having to abide by it (Tagesschau November 23, 2020). Defying her critics and risking inner-party strife, Merkel stands solidly behind both initiatives. When celebrating 100 years of the women’s vote in 2019, she declared that ‘quotas were important, but parity has to be the goal’ (Merkel Citation2018). Chastising legislators across parties, she argued in the Bundestag that publicly traded companies without a single woman on their executive boards are ‘a situation that one can’t find reasonable’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung November 21, 2020). By supporting the quota, Merkel broke with aspects of her longstanding governing style of ‘leading from behind,’ showcasing public-facing agenda-setting instead of facilitating backroom decisions (see Ahrens, Ayoub and Lang, Citationthis issue).

Even though Merkel has not established herself as a leader in women’s rights, she has helped facilitate what for some in the CDU is a curse and for others a revolution: that the party debates and acts on quotas. The process by which a troika of three CDU women leaders, Merkel as Chancellor, Ursula von der Leyen as EU Commission President, and Kramp-Karrenbauer as party leader and Secretary of Defence, managed to open up space to bring quotas from the margins to the centre of the party debate, marks a critical juncture in CDU gender politics. This article will focus on the quota in political representation (see Ahrens and Scheele, Citationthis issue, on the corporate board quota), unpacking the historical stages of the CDU’s quota debate. What explains the party’s trajectory from being staunchly ‘anti-quota’ to debating a 50 per cent quota in political representation? We argue that three factors under Merkel’s leadership help explain this surprising transformation from quietly opposing to facilitating quotas: shifts in the framing of gender equality, electoral strategy, and gendered mobilisations within the party and beyond.

In order to assess how Merkel’s CDU struggled with the quota, we employ a mixed-methods approach that incorporates results from a comparative research project on party quota adoption in Germany and Austria on the federal and selected Land-levels from the 1980s to the present (see Ahrens et al. Citation2020). Data includes party regulations, related media reports and respective electoral laws. We also make contextual inferences based on six semi-structured interviews on the ‘quorum,’ conducted between 2017 and 2019 with CDU spokespersons on women’s issues in appointed and elected offices (Ahrens et al. Citation2020). To ensure broad coverage, we chose interviewees from the federal and Länder level, the latter including a progressive city–state and a conservative territorial state.

The article proceeds as follows. We start by embedding the CDU quota in the broader theoretical context of the literature on symbolic, descriptive, and substantive representation. We will then assess the party’s pathway during the Merkel era from staunch quota opposition to adaptation, highlighting frames that help reposition the CDU’s gender equality agenda. Next, we use electoral data to explain why the need for the CDU to shift its stand towards representational equality became more pressing over time. We then address the mobilisation of the CDU Women’s Union and civil society allies to increase CDU investment into parity. Finally, we assess CDU positions regarding parity laws and federal electoral reforms. Together these sections develop our concluding argument, that both the parity law and electoral reform debate highlight how Merkel opened up discursive spaces in her party that condoned shifts in frames, electoral strategy, and women’s mobilisation. Merkel’s longstanding ‘leading from behind’ strategy, however, might limit CDU reform capacity and in turn extend the party’s quota curse into the post-Merkel era.

ANCHORING THE CDU QUOTA IN DESCRIPTIVE, SUBSTANTIVE, AND SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATION

Since 2017, Angela Merkel featured globally as the female leader with the longest tenure (Geiger and Kent Citation2017). 16 years as German Chancellor gained her Time Magazine covers as ‘Chancellor of the Free World’ (2015), and ‘Frau Europa’ (2019), and a Der Spiegel cover as ‘Mutter Angela’ (2015) for her engagement during the refugee crisis. In terms of symbolic representation of gender in politics, Germany under Merkel’s tenure took a big leap. Her visibility as woman Chancellor with internationally high marks, however, neither translated into decisive CDU action against underrepresentation of women in the party nor into a mainstreamed government focus on women and gender issues. Having a female leader and an enhanced symbolic representation of gender thus had only spurious effects on increasing descriptive and substantive representation of women’s issues in the CDU.

Literature on descriptive representation has become increasingly cautious with ascribing direct linkages between women’s presence in politics and policy change (Childs and Lovenduski Citation2013, 492). Instead of constructing common ‘women’s interests,’ research has shifted the ‘politics of presence’ (Phillips Citation1995) argument into an equal rights argument and thereby upended and de-ideologised the quota debate. This shift in the representation frame highlights that under-representation distorts diversity of societal input into political processes, abandoning the need for common women’s interests to legitimise their representation. It allows for the performance and public acknowledgement of ‘critical acts’ by women that are not necessarily feminist but are borne out by particular experiences (Dahlerup Citation1988). Angela Merkel, we claim, has performed such critical acts, particularly in her tenure, that in turn emboldened women in her party and helped bring to the fore the inner-party conflict on quotas.

As theorising on gender and representation has shifted from a ‘common interest’ frame to a ‘women’s poverty of representation’ frame (Celis and Childs Citation2020, 32), it stipulates that ‘when women are well represented in representative democracies, the formal political agenda is recalibrated away from the political representation of men and their interests.’ This preposition does not need a unified ‘female subject.’ Instead, it opens the representative realm towards a de-centering of men’s interests. Unburdening descriptive representation from a substantive rationale has arguably helped the quota debate in conservative parties, in particular (Celis and Childs Citation2014). Implicitly acknowledging ‘poverty of representation’ led Angela Merkel to advance women in her cabinets on an unprecedented scale. Over her four tenure periods as Chancellor, she successively appointed more women Ministers than any previous government: her fourth coalition government formed in 2018 showcased 43.8 per cent women (Brandt Citation2018). Including Merkel, the CDU even took the lead regarding cabinet posts with four women and three men, followed by the SPD with parity; three men and three women. The Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) sent three men, thus upending parity.

Whereas Merkel championed women in ministerial and staff appointments, playing a critical role in enhancing symbolic and descriptive representation, she appeared much less committed to interfere in her party’s nomination practices, its outcomes, as well as overall electoral processes. During most of her tenure, she neither spoke up for women’s representation in the party nor did she endorse early quota demands. Just as in other European conservative parties, CDU programmatic positions under Merkel’s first two legislative periods advanced primarily formal representational claims, arguing that if more women wanted to enter politics, democratic processes ensured that there was nothing standing in their way. As more CDU gender equality activists pointed to the fact that – despite the quorum – women were not advancing in the party, Merkel became quietly more amenable to their cause. Convincing a majority of party members to vote for a corporate board quota (Och Citation2018) increased the inner-party debates and emboldened the Women’s Union.

Under Merkel’s watch and alongside her, conservative women increasingly severed the knot between descriptive and substantive representation as a frame for demanding better representation. Merkel herself provided the clarion call for this awakening, as she – despite having served as Women’s and Youth Minister between 1991 and 1994 – herself never ran on women’s issues. She did, however, hear the demand for a new electoral strategy to attract more women from within the party’s Women’s Union. Observing the CDU’s ongoing ‘women’s poverty of representation’ as well as incrementalism and stasis induced by the quorum, she allowed for more powerful pro-quota voices to rise. Reframing gender equality in the CDU to invite a renewed debate on enhanced representation might not have happened at Merkel’s invitation, but arguably it could not have happened without her quiet consent.

THE CDU AND WOMEN’S REPRESENTATION: FROM ANTAGONISM TO ADAPTATION

Scholars have established that the CDU traditionally was antagonistic towards quotas (Wiliarty Citation2010; Davidson-Schmich Citation2016). As the party saw their rivals from the SPD and the Greens attract more women members and women voters by utilising voluntary party quotas, the CDU witnessed substantial losses of its female electoral base. Until 1972, considerably more women than men had voted for the CDU in every post-war federal election (Böhmer Citation2008, 19). In 1980 (and again in 2002), however, the CDU women’s vote reached all-time lows (Hien Citation2014, 48) and calls for action became louder. In 1986, the CDU vowed to increase the number of women in party offices and parliaments in line with their party membership by the early 1990s (Böhmer Citation2008, 20). Without the party showcasing more tangible results, the Women’s Union pushed for stronger commitments. During an agitated party congress in 1988, the majority refused to use the term quota and instead advised a voluntary 33 per cent women’s quorum for party candidate lists and office lists (Lemke 2001; Davidson-Schmich Citation2016, 31–32). Despite the difference in terminology, the CDU followed the example of SPD and Greens, experiencing the first symptoms of ‘quota contagion’ (Davidson-Schmich Citation2016; Lépinard and Rubío Citation2018).

When, after the fall of the Wall and German unification in 1990, two different gender regimes merged (Lang Citation2017), the landscape for CDU women’s activism changed dramatically overnight. West German CDU party ideology – having struggled in the 1980s with providing a roof for both a politics of gender difference, women’s family-orientation and anti-abortion, as well as for younger women’s interests in combining careers and family and pro-choice orientation – was radically reframed in the post-unification CDU. East German party members with a strong sense of accomplishment as career women and mothers, and accustomed to public childcare and reproductive rights, brought new perspectives to the Women’s Union and into party offices. The share of women party members, however, stayed constant at 25 per cent between 1992 and 2008 (Böhmer Citation2008, 21). In 1996, the presence of CDU women from the eastern Länder helped to elevate the quorum from an advisory to a mandatory provision laid down in the party’s bylaws. In 2001, with abolishing the quorum’s sunset clause, the CDU acknowledged that the problem of women’s underrepresentation was not going away (CDU Citation2018, 6). Merkel, first as the party’s secretary general (1998–2000) then as party leader from 2000 onwards, despite her East German socialisation, remained noncommittal on the issue.

When in 2005 Angela Merkel was elected to become the first woman Chancellor in Germany, the CDU women’s equality activists took this as a signal for an increased push towards gender equality. Maria Böhmer, then leading the Women’s Union, argued in 2008 ‘I’m convinced that the election of the first female Chancellor will be seen in hindsight as just as an important step as the introduction of the women’s right to vote in Germany in 1918 and the anchoring of equal rights in the Basic Law in 1949’ (Böhmer Citation2008, 19). The Women’s Union was determined to utilise the first women Chancellor to scandalise the party’s continued disenfranchisement of women. The initial focus was on data gathering and documenting the party’s gender gap. In 2006, the CDU annual ‘Women’s Report’ was replaced with a more encompassing ‘Gender Equality Report’ in which not just national and Land-level data, but also mayoral, district and EU-level candidacies and elections were disaggregated by gender (Böhmer Citation2008, 22). The results were striking: even though the party’s gender balance had improved since introducing a quorum, CDU women had only made small advances in parliamentary representation, from 14.7 per cent in the pre-quorum 1995 Bundestag to 21.5 per cent in 2019 (CDU Citation2015, 2019).

Whereas women’s representation in the CDU stagnated during the first two Merkel cabinets from 2005 to 2013, the party shifted ideologically, especially regarding family and labour market policies (Henninger and von Wahl Citation2014; see Auth and Peukert, CitationForthcoming). Propelled by eastern members, women activists, and a social investment approach to the labour market, CDU support for the male breadwinner model softened and the party increasingly turned toward a dual earner/caretaker model (Henninger and von Wahl Citation2014; Hien Citation2014). This ideological ‘feminisation’ of the CDU ‘only became possible once the party realigned from a Catholic to a liberal Protestant constituency […] facilitated by the German reunification process’ (Hien Citation2014, 42). Historically, the CDU’s alliance with the Catholic Church had fortified the male breadwinner model and traditional family values (Hien Citation2014). As the idea of equal participation of women and men in paid and unpaid work took hold, it also spilled over into the realm of political representation.

During her early tenure, Merkel quietly endorsed the CDU Headquarters’ initiative to attract women to the party by starting various women mentoring programmes. Under Secretary General Ronald Pofalla and in coordination with the Women’s Union, the CDU published a detailed instruction manual for members on how to apply the quorum (CDU Citation2007). Pofalla, and surely not against Merkel, established an official grievance office within the legal unit of the party headquarters to address violations of the quorum (Böhmer Citation2008, 23; CDU Citation2007). Böhmer interpreted the party headquarters’ message as ‘no more tricks’ (Böhmer Citation2008, 23), advising party leadership from national to local levels to take the quorum seriously.

Overall, however, the CDU showed much less gender balance in parliamentary settings than the SPD, the Greens, or the Left – only the CSU and the Liberal Party (FDP) (and from 2017 onwards the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)) had fewer women legislators in the Bundestag and in party leadership positions. Kintz (Citation2019), comparing legislative leadership positions across German parties in the ‘pre-Merkel’ Schröder era (election periods 14 and 15) to the Merkel era (election periods 16–18) concludes that under Merkel, CDU women made some advances in leadership positions, but by far not on the scale of the SPD or the Greens. Gender in the CDU, she argues, ‘does not have a significant impact on being recruited to leadership positions for the first time’ (Kintz Citation2019). Instead, seniority remains the strongest predictor of advancement in the party. When Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer became Secretary General of the CDU in 2018, she called out the rather dismal women’s representation: ‘It is notable that the share of women among CDU legislators in the German Bundestag is at 20 per cent – and that is the same share as 20 years ago. […] in some Länder there are fewer women members of the legislature today [in 2018] than 20 years ago’ (CDU Citation2018, 4).

Why is the CDU at an apparent impasse over the attempt to increase women’s representation, more than three decades after the first voluntary quota was introduced in the party? The next section will address factors that impacted CDU women’s advancement in legislatures during Angela Merkel’s tenure as Chancellor.

THE ELECTORAL OUTPUT: WHY THE QUORUM HAD TO FAIL

The CDU states programmatically, as do all German voluntary quota parties, that the goal of affirmative action measures is to achieve equal participation of women and men in politics and society – in today’s parlance, all parties’ goal is to reach parity (Ahrens et al. Citation2020). CDU General Secretary Pofalla articulated this when explaining the women’s quorum in 2007: ‘The equal representation of women in shaping politics is part of our identity as Christian Democrats. This, in and of itself, is enough to oppose those who at times reduce our cause to a strictly regulatory framing of the women’s quorum’ (CDU Citation2007). Thus, the 33 per cent women’s quorum is, according to Pofalla, not simply going ‘through the motions,’ and it marks not a ceiling, but a bottom-line of women’s representation in the party, with the goal of gender parity. Building on this de-facto affirmative action approach, we contend that asking if parties adhere to their ‘regulatory framing’ of party policies would be a limiting perspective. We must also explore if and to what degree these policies achieve their stated goal of reaching parity.

Although, starting with the Greens and SPD, voluntary party quotas have been employed in German elections for more than three decades, the Bundestag is far from reaching gender parity. If we disregard the strict quota-opposing parties, the FDP and AfD, and only look at voluntary quota parties, we find a clear discrepancy between quota intention and results. This is particularly true of the former ‘catch all parties’ CDU and SPD. In addition to quota-stretching and -bending granted within parties’ regulatory frameworks (Ahrens et al. Citation2020, 67–70), numerous intersecting factors can undermine a quota on its path from party statute to implementation. Not only do soft recruitment policies within soft regulations upend voluntary quotas. They also do not sit well within the German mixed-member proportional system, which combines Länder-level electoral lists with direct mandates for candidates running in one of the 299 electoral districts. The majority of voluntary party quotas apply only to electoral lists and thus to only about half of the parliamentary seats. To be more effective, quotas would also need to be implemented for direct candidacies. Ultimately, quota effectiveness can be measured by assessing differences between a party’s quota stipulation and outcome, a measurement that has been defined as ‘post-quota gender gap’ (Ahrens et al. Citation2020).

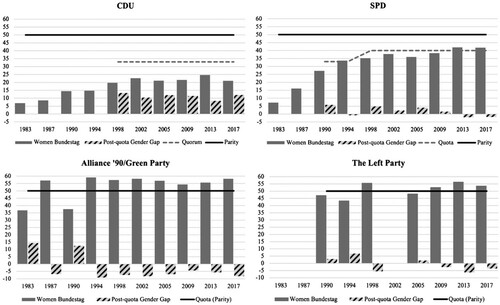

We visualise the post-quota gender gap by juxtaposing a party’s stated quota objective and its output in parliamentary seats for women over time. Thus, the post-quota gender gap does not assess objectively how parity-oriented a party really is, but the effectiveness of a party’s quota policy. A ‘positive’ bar for the post-quota gap signifies missing a party’s quota – 33 per cent for the CDU, 40 per cent for the SPD, 50 per cent for Greens and the Left – and disadvantaging women. In case a party exceeds its quota target to the advantage of women, the bar for the post-quota gender gap turns ‘negative’ thereby illustrating the surpassing of the target.

shows that the CDU has not reached a 33 per cent threshold in women’s representation in any federal election since 1988, when the voluntary quorum was first recommended or after 1996, when it was formalised. For example, in the election 2017, the CDU women’s share in the Bundestag was at 21 per cent, resulting in a post-quota gender gap of 12 percentage points. By contrast, the Greens had a 58.6 per cent women’s share and thus even a ‘negative’ post-quota gender gap of 8.6 per cent. Compared to the CDU, all other quota parties – SPD, Greens, The Left – fared better in avoiding a post-quota gender gap for women.

Figure 1. Post-quota gender gaps of german quota parties in the Bundestag, 1983–2020.

Source: Bundeswahlleiter Citation2017, Citation2018. Calculation and design by authors.

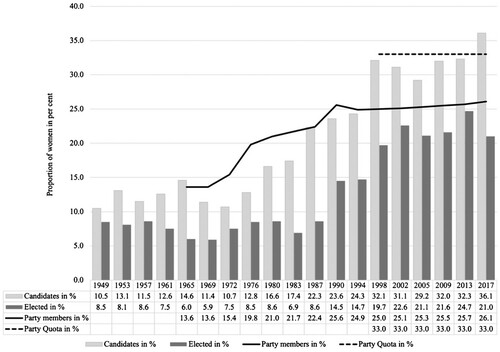

During Merkel’s four tenure periods as Chancellor between 2005 and 2021, the CDU consistently missed its quota target by more than 10 percentage points (with one exception: 8.3 per cent in 2013). The federal election of 2017 with 21 per cent CDU women representatives in parliament increased the post-quota gender gap to 12 per cent, more than three percentage points up from the 2013 election. Indeed, even among candidates the CDU only reached its quota in 2017. , which compares data for party membership, candidates, and elected, also shows that, since 1949, CDU women were never represented proportionally to their party membership (see ; see also Davidson-Schmich Citation2018).Footnote3

Figure 2. Party membership, candidates and elected – CDU women, 1949–2017.

Source: Bundeswahlleiter Citation2017, Citation2018; Niedermayer Citation2017. Calculation and design by authors.

Two factors explain the CDU’s quota failure: (1) it is by design a weak party measure as a non-sanctionable, almost facultative provision, and (2) it does not fit with the CDU’s electoral paths to power, which are driven by direct candidacies that are not subject to the quorum. Soft quota rules and weak recruitment are often cited as the most obvious reasons for women’s underrepresentation. Even though the quorum for all candidate lists in elected office is fixed in the party statutes, its regulatory framing is weak, and it is implemented rather haphazardly. Davidson-Schmich (Citation2016, 199) found in her ‘Candidate Interest Survey’ that 11 per cent of CDU members ‘erroneously believed their party had no affirmative action policy at all’ – as opposed to only one per cent of Greens and two per cent of Social Democrats. CDU women party members are also less likely than their male counterparts to accept a nomination for local elections (Davidson-Schmich Citation2016), due to the difficult cultural environment in which the CDU recruits for office. Additionally, the quorum applies only to first-round nominations for electoral lists, and not to direct candidacies. If fewer than 33 per cent women are nominated in the second round of list compilation, missing the quorum does not lead to sanctions. Overall, there has historically not been sufficient party pressure to fulfil the quorum in candidate selection. In some cases where women have challenged party list composition by way of internal and non-disclosed complaint procedures to the CDU general legal counsel, the outcome has been to their disadvantage (Ahrens et al. Citation2020, 69).

Whereas many of these challenges go publicly unnoticed, a case in point presented itself in advance of the election of CDU candidates to the Bundestag in Saxony-Anhalt in 2017. Here, the CDU leadership had crafted a candidate list with a woman leading the list as top candidate – followed by eight men. The Head of Saxony-Anhalt’s Women’s Union, representing 2,000 women CDU members, decided to appeal to the national party headquarters’ legal counsel, as stipulated in the CDU bylaws (Bock Citation2017; CDU Citation2007). In her letter to the legal team, she stated that the list in its current form discriminated against women and that she would go public if the party would not reject the list. She advised the head of the legal team to consult with Land-level party leadership to achieve compliance with party regulations (Bock Citation2017). The national party legal counsel, however, did not reply to her letter before the CDU party convention voted on the list. After internal consultation, the Women’s Union decided not to press formal charges against the list; the CDU Land-level general secretary argued that the women’s quota ‘is a “should” regulation and not a must’ (Volksstimme May 12, 2017). He declared it to be an unwritten law that all direct candidates of the party in Saxony-Anhalt need to be secured by way of the top list positions. The retort from the Women’s Union, that the quorum was a ‘written law,’ did not alter the party stance. The party congress voted to accept the original list with one woman and eight men. The unwritten Saxony-Anhalt practice of first securing direct candidates on top list positions, and only then employing the quorum, however, is not always practiced in CDU nomination processes. In adjacent Thuringia, candidate nominations in the same year reflected adherence to the quorum as the top priority instead of securing direct candidates by way of list placement.

CDU quota resistance is also evident in European Parliament elections which operate exclusively with electoral lists. Differing from other major parties, the CDU compiles Land-level electoral lists instead of a national list. Effectively, in the 2014 elections, the subnational CDU chapters missed the quorum by ten percentage points, absent a single woman among the two to three candidates in each of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, and Saxony-Anhalt, and with Baden-Württemberg nominating nine men and one woman (Lang Citation2018, 288).

The second factor fuelling the CDU’s post-quota gender gap is the party’s success with direct candidacies, while ‘women are more frequently list-only candidates than men, and by extension less often dual or district-only candidates’ (Coffé and Davidson-Schmich Citation2020, 88). Under Merkel’s four tenure periods, the CDU increased its share of all direct mandates in Germany’s federal elections from 50 per cent to almost 80 per cent (Behnke Citation2020, 4). In the election of 2017, the CDU received 231 direct mandates and only 15 parliamentary seats via the list.Footnote4 Of these 231 direct mandates, CDU women received 34, a mere 14.7 per cent. Not just in the CDU, but also in the SPD, selecting direct candidates ‘independently,’ that is without interference from higher-level party offices, is sacrosanct. In the Green and Left parties, by contrast, parity is seen as a higher good which leads to women actively utilising the ‘gender card’ to gain direct candidacy nominations. Direct candidacies, however, are less central to overall electoral performance of these parties, as they acquire almost all seats by way of list mandates (Ahrens et al. Citation2020; Höhne Citation2020).

The CDU selects direct candidates either by way of a district-level member caucus or a delegate meeting (Höhne Citation2017, 236). Incumbents generally have a substantial advantage of being re-nominated; only rarely are there challengers from within the party. The ‘incumbency rate’, that is the percentage of mandates that are held by the same legislator pre- and post-election, has traditionally been higher for the CDU and CSU than for any other party (Höhne Citation2017). In 2013, 81 per cent of CDU members of the Bundestag had been holding their seat already in the previous electoral period, while the SPD had a lower incumbency rate of 70 per cent. To make the quorum a reality for CDU direct candidacy nominations would have needed an outspoken commitment from the Chancellor. Merkel has acknowledged that the damage done to women’s representation by direct mandates cannot be ‘repaired’ via party lists (Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland Citation2018). Framing the issue adequately, however, did not result in a parity campaign to reform nomination processes. Merkel thus allowed continuing the practice of leaving ‘CDU men’s circles [to] brood in closed chambers over “who gets where what”’ (Die ZEIT, July 15, 2020).

In sum, gender-sensitive electoral strategies have been lacking during Angela Merkel’s tenure as chancellor and party leader. The soft quota in conjunction with the CDU’s success in direct candidacies has cemented a substantial CDU post-quota gender gap. A 33 per cent quorum is in and of itself a less than ‘minimum’ standard for gender equality, compounded by the fact that the quorum is only applied to party lists, to only the first round of list composition, and lacks meaningful sanctions. The quorum’s ineffectiveness and a laissez-faire approach to direct candidacy parity signals that the CDU, under Merkel’s watch, serves two opposing constituencies: Party leadership has tacitly accommodated quota critics, allowing the quorum to be bent and stretched as needed, while publicly endorsing it as a forward-looking strategy. At the same time, Merkel’s apparent non-intervention opened up discursive spaces for those within the party who tout the quorum as ineffective. Thus, rather than steering the CDU towards better women’s representation, the chancellor played a facilitating role in allowing the inconsistencies and ineffectiveness of the quorum to surface, while more recently also acknowledging that parity is the only fair standard to employ.

When Merkel addressed the Women’s Union on the occasion of its 70th birthday in 2018, she declared that increasing women’s representation in the party is an ‘existential question’ and that ‘the quorum is not sufficient anymore’ (Merkel Citation2018). While she did not present an alternative path to gender equality, the Women’s Union took Merkel’s message to heart: It renewed and increased advocacy for a stricter quota with effective sanctions, and mobilised with the message that the CDU might lose women if the party does not modernise swiftly.

QUOTA ACTIVISTS FROM WITHIN: THE WOMEN’S UNION PUSHING FOR REFORMS

The CDU Women’s Union is the key actor in the process we have sketched out above. With its approximately 155.000 members, we credit it with nudging Angela Merkel from a staunch quota resister to tacitly tolerating and finally endorsing it. As we pointed out earlier, it was the reframing of the quota debate in terms of a ‘poverty of representation’ argument that over the past decade convinced more and more CDU women that the quorum in its current form is ineffective. The CDU Women’s Union is the place in which this revisionist framing took place, pointing to the linkages between parliamentary representation and wider civic spaces with modes of doing representation in civil society that weigh on gender politics (Celis et al. Citation2014; Saward Citation2020, 9–11.) According to Celis et al. (Citation2014, 152), ‘political representation is best conceptualised as an active, multifaceted, and contingent process, driven by a broad swathe of actors with various views on group issues and interests.’ Thus, contestations over the future of the representation of women in the CDU did not only occur within the party committees in charge of statutes and regulations, but it prominently featured in the party’s women’s organisation with its linkages into civil society.

The achievements of CDU women in party offices and electoral settings can be traced directly to the rise of the Women’s Union from a largely social club to a power hub within the party (Wiliarty Citation2010). Beginning in the 1980s, its members loudly articulated support for stricter quota measures (Böhmer Citation2008). Women’s Union leader Annette Widmann-Mauz admonished her party in 2018 to read the writing on the wall: ‘Since inner-party political structures and the electoral law in fact make women hit a glass ceiling or be shut out, we need new regulations’ (Widmann-Mauz Citation2018, 118). She asked the CDU to respect the quorum just as much as it respects other quotas such as Länder representation on national committees. Party lists, according to Widmann-Mauz, should not just have a 33 per cent quorum, but should be gender-balanced. In 2020 the Women’s Union, in concert with then party leader Kramp-Karrenbauer, initiated a revolutionary statutory reform to raise the CDU quorum to a veritable 50 per cent quota for electoral office and candidacies by 2025.

The Women’s Union initiatives were also applauded by their conservative Bavarian partner organisation, the CSU Women’s Union. When it met in 2017 to debate their proposals for the upcoming party convention, one of the last items on their 120-page agenda held just as much dynamite as earlier CDU Women’s Union proposals. The CSU women asked their party leadership to support a motion to employ a zippered candidate selection system from the Land- to the district-level, acknowledging that this was in effect a ‘women’s quota of 50 per cent, with male and female candidates alternating’ (CSU Citation2017a, 111). The rationale for this party motion by the Munich chapter of the association resembles a modernised Merkel-version of adequately representing women and thus a ‘poverty of representation’ argument. Women, according to this motionFootnote5, need to be equally represented because they make up ‘50 per cent of the polity and 60 per cent of voters.’ (CSU Citation2017a, 111). The motion was not supported by a majority of delegates in the Women’s Union meeting; instead, the majority endorsed establishing a Commission called ‘Strong Women for the CSU’ (CSU Citation2017b, 86). In contrast to Merkel’s longstanding quota resistance, Bavarian CSU Governor Markus Söder after his election in 2019 intended to lead with increasing women’s representation, emulating a strategy that ÖVP party leader Sebastian Kurz had pioneered in Austria.Footnote6 Even though Söder’s attempt to establish a 40 per cent hard quota on party lists could be viewed as symbolic politics, as the CSU tends to win a majority of seats in Bavaria via direct mandates, it did not convince the party base. The party convention turned the hard quota into a soft quota. CSU Women’s Union leadership, however, seemed undeterred: ‘We will evaluate the implementation of the quotas and work with the results’ (Scharf Citation2020).

In sum, CDU and CSU mobilisation in their respective Women’s Unions contributed to the parties’ quota fights in different ways. Whereas Merkel, for the majority of her tenure, set her policy goals for women’s representation in the CDU according to what she perceived to be the majority position while quietly and simultaneously placating the Women’s Union, Söder aligned himself with the CSU Women’s Union to promote a hard quota. In both cases, the party base resisted change, resulting in friction between modernisers and traditionalists and publicly displaying the quota curse’s hold over the party. At the same time, however, new stages for the fight over women’s political representation emerged by way of Land-level parity initiatives and electoral law reform on the federal level.

CHOOSING THE LESSER EVIL? THE QUOTA CURSE IN THE CONTEXT OF PARITY INITIATIVES AND ELECTORAL LAW REFORM

The CDU’s more recent quota debates occur in a societal context that increasingly embraces a ‘women’s poverty of representation’ frame (Celis and Childs Citation2020) and acknowledges that voluntary party quotas might not be able to redress legislative imbalances. Public awareness for women’s representation was particularly high when, in 2019, Germany celebrated the centennial of the women’s vote. With a sizable drop in women’s Bundestag representation after the federal elections on 2017, calls for legislating parity – as France had done in 2000 – became louder. As a consequence, the CDU witnessed increasing Land-level legislative activities to counter women’s underrepresentation as well as calls to use a long overdue reform of the federal electoral law to advance parity.

At the core of these mobilisation were women’s NGOs and cross-party alliances that had long promoted parity. Networks including the German Women’s Council, the sixteen Land-level Women’s Councils, professional women’s organisations and those of the political parties, including the CDU’s, lobbied for effective legislative measures on Land- and federal levels (Abels and Cress Citation2019; Lang Citation2018). As of early 2021, proposals for legislative quotas had been discussed in 15 Länder parliaments (except Hesse). Seven Länder (Bavaria, Brandenburg, North-Rhine Westphalia, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig-Holstein, and Thuringia) had already debated or scheduled to debate formal legislation.Footnote7 However, the two parity laws stipulating alternating electoral lists (adopted in 2019 in Brandenburg and Thuringia) (Abels and Cress Citation2019; Lang and Ahrens Citation2020), were ruled unconstitutional by respective Land-level Constitutional Courts, requiring parity law activists to design other innovative proposals that could pass legal challenges. Even though the Women’s Union helped mobilise for parity law initiatives, party leadership did not shepherd the proposals through parliament.

Overt or latent resistance also appear to be the CDU’s strategies regarding parity-oriented federal electoral reform. A cross-party electoral reform commission, headed by the President of Parliament Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU), has become the main target of electoral gender quota advocates. A cross-party women’s parliamentary group started meeting in 2019 to explore strategies to tackle women’s underrepresentation and exert influence on the envisaged electoral reform (Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 20, 2019; Der Spiegel February 13, 2019). The Women’s Union joined other parties and women’s NGOs in lobbying for combining electoral reform with legislative quotas, directly appealing to fellow CDU-member Schäuble. Yet, Schäuble rejected any such proposal, calling ‘rules that in any way might imply prescribing to a voter who he should vote for as doubtful’ (cited in Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 12, 2018). For the federal election of 2021, only few electoral law revisions were agreed upon by the Schäuble Commission; a larger reform is intended for the next legislative period. The CDU, however, knows that parity mobilisation has only just begun. Raising and fortifying the inner-party quorum might be considered by many in the CDU to be a lesser evil than parity reform on both Land and federal levels.

CONCLUSION

This article investigated Angela Merkel’s influence on increasing women’s political representation in the CDU by way of quotas. We argued that, while Merkel clearly was no bold leader in women’s rights, she did help facilitate what some in the CDU see as a ‘curse’ and others (within and outside the party) see as a ‘revolution’ in gender equality: the CDU is now obliged to debate and seriously consider a stricter quota. Merkel has changed her position on quotas from subtle opposition by way of indifference to active endorsement. While she ‘gladly’ spoke out against quotas in the early years of her political career, she later acknowledged that she ‘would not have made it’ without the quorum (cited in Mushaben Citation2017, 39). Her ‘coming out’ in support of quotas might have been facilitated by the troika of three CDU women leaders, with Merkel as Chancellor, Ursula von der Leyen in various ministerial positions, and Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer in different party and executive leadership positions (see Mushaben CitationForthcoming). This constellation of three powerful CDU women leaders managed to open up space in the party to bring quotas from the margins to the centre of the debate. Top-down leadership on women’s representation – to some degree sidelining resistance at the party’s base – thus appear to be central drivers for gender equality in the CDU. They were already in play when Rita Süssmuth in 1996 pushed her party to adopt the quorum. Since then, the CDU and Merkel tried to serve these opposing constituencies by allowing the quorum to be bent and stretched while publicly endorsing it as the CDU’s major strategy towards parity. With her recent ‘coming out’ on strict quotas, however, Merkel inadvertently may herself have initiated a critical juncture in CDU gender politics.

We have argued that three factors contributed to moving the CDU from a staunchly ‘anti-quota’ party under Merkel’s leadership to accepting a stronger interventionist hand in achieving gender equality in political representation. The factors speak to shifts in framing gender equality, electoral strategy, and gendered mobilisations in the party and beyond. More specifically, we analysed, first, how Merkel advanced an explicitly non-feminist equality agenda within an adaptive social conservatism that in turn was influenced by her East German background. She actively supported the CDU moving from a narrow focus on the male breadwinner model to acceptance of dual worker/caretaker models. This, in turn, over time led to more gender-inclusive programmatic party stances across different policy fields, and it spilled over into political representation. Second, Merkel critically assessed the effects of negative electoral outcomes for women in relation to declining party membership and women voter appeal, realising that resisting quotas would be the wrong signal in her attempt to modernise the party. Having, with the SPD, a more gender-progressive coalition partner at her side most likely contributed to Merkel’s interventionist turn. Third, Merkel over time allowed growing influence of inner-party gender equality actors and in particular the Women’s Union in reshaping the CDU stance on quotas.

Notably, intersectional dimensions to these changes – aside from appealing to younger women – have been mostly absent from the CDU quota debates.Footnote8 Despite major underrepresentation of persons with a so-called migration background, particularly Muslim women, none of the German quota parties endorses affirmative action measures for these constituencies (Jenichen Citation2018). When the Federal Conference of Migrant Organisations (BKMO) proposed to adopt a Federal Participation Law with mandatory quotas for cabinets and ministries, the CDU position was in line with public opinion: the majority of voters of all parties consider quotas for migrants unnecessary – CDU supporters by almost 86 per cent (CSU 97 per cent) (Coffé and Reiser Citation2018, 182).

The CDU may have inadvertently paved a path to harder voluntary party quotas for women, with Merkel evolving from opposing to facilitating quotas. Many in the party will perceive this to be the lesser evil, faced with much stronger demands to reframe representation with an intersectional lens and champion parity by way of legislative quotas within an electoral reform. In line with this ‘choice’, Merkel shifted her tone on women’s underrepresentation during the 4th term of her tenure. While still not actively championing parity, she appeared to embrace the notion that the ‘Gruppenbild mit Dame,’ the ‘group photo with lady’ approach to politics is irritating (New York Times January 30, 2019). This irritation, however, does not compensate for her long-lasting silence regarding inner-party masculinist structures. Carefully orchestrated positive action – rather than Merkel tacitly leading from behind on gender equality – may have left the party less masculinist. The debate and vote on the party’s programmatic commission proposal of a 50 per cent quota for party offices and candidates by 2025 has been shelved until at least the next party convention. Party leader and CDU chancellor candidate Armin Laschet has not led by example on the Land-level: His 2021 cabinet in North Rhine-Westphalia features seven men and only two women. His cautious tactical approach to quotas has been on display when he on the one hand promised parity in his future cabinet in March 2021 and at the same time had his party and equality minister refrain from advancing the North Rhine-Westphalia parity initiative.Footnote9 Without committed leadership on this issue, gender parity in the CDU will almost certainly remain an elusive goal for years to come.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Petra Ahrens

Petra Ahrens is Senior Researcher in the ERC-funded research project EUGenDem, Tampere University, Finland. She focuses on gender policies and politics in the European Union, civil society organisations, and gender equality in Germany. She has published in journals such as the Journal of Common Market Studies, Parliamentary Affairs, and West European Politics. Her latest books cover Gender Equality in Politics: Implementing Party Quotas in Germany and Austria (2020, co-authors Katja Chmilewski, Sabine Lang, Birgit Sauer), Gendering the European Parliament. Structures, Policies, and Practices (2019, co-editor Lise Rolandsen Agustín), and Actors, Institutions, and the Making of EU Gender Equality Programs (2018).

Sabine Lang

Sabine Lang is Professor of European and International Studies in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington, where she directs the Center for West European Studies/Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence. Her work focuses on gender politics and civil society in comparative perspective and in the EU. Her most recent publications are Gender Equality in Politics: Implementing Party Quotas in Germany and Austria. Springer 2020 (co-authors Petra Ahrens, Katja Chmilewski, Birgit Sauer) and Gendered Mobilizations and Intersectional Challenges: Contemporary Social Movements in Europe and North America. ECPR Press/Rowman & Littlefield 2019 (co-edited with Jill Irvine and Celeste Montoya).

Notes

1 Trying to soften the stigma of the term quota, the CDU created the label ‘quorum’ for its voluntary party quota. We use the term throughout to acknowledge its low compulsory character compared to other voluntary party quotas, but simultaneously consider it a de facto quota. The Bavarian sister party Christian Social Union (CSU) developed different rules that are not the focus on this article.

2 All translations are from the German and by the authors.

3 The party’s youth organisation, Junge Union, which serves as a recruitment pool for future higher office, by contrast, had increased its share of women to 44 per cent by 2018 (CDU Citation2018). Yet, this source appears to remain untapped and dramatically dried up within a year: in 2019 the Junge Union women’s share dropped to 30 per cent (CDU Citation2019).

4 Information at Deutscher Bundestag https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/biografien/mdb_zahlen_19/direktmandate_landeslisten-52951, accessed December 7, 2020.

5 The CSU Frauenunion motion is not just noteworthy for its content and political verve, but also for its use of academic literature to support its argument for quotas.

6 In the Austrian snap election of 2017, Kurz had presented a national electoral list for the ÖVP based on a 50 per cent zippered gender quota (Ahrens et al. Citation2020, 73).

7 For details see https://www.frauen-macht-politik.de/gesetzesinitiativen-in-den-bundeslaendern/, accessed February 16, 2020.

8 For changes in inner-party attitudes towards out LGBT CDU politicians see Juvonen Citation2019; see Henninger as well as von Wahl, both CitationForthcoming, for LGBTIQ+ policies under Merkel.

References

- Abels, Gabriele, and Anne Cress. 2019. “Vom Kampf ums Frauenwahlrecht zur Parité: Politische Repräsentation von Frauen gestern und heute.” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 50 (1): 232–251.

- Ahrens, Petra, Katja Chmilewski, Sabine Lang, and Birgit Sauer. 2020. Gender Equality in Politics – Implementing Party Quotas in Germany and Austria. Cham: Springer.

- Ahrens, Petra, Phillip Ayoub and Sabine Lang. Forthcoming. “Leading from Behind? Gender Equality in Germany During the Merkel Era.” German Politics.

- Ahrens, Petra and Alexandra Scheele. Forthcoming. “Game-changers for Gender Equality on Germany’s Labour Market? Corporate Board Quotas, Pay Transparency and Temporary Part-Time Work.” German Politics.

- Auth, Diana and Almut Peukert. Forthcoming. “Gender Equality in the Field of Care: Policy Goals and Outcomes During the Merkel Era.” German Politics.

- Behnke, Joachim. 2020. Schriftliche Stellungnahme zur öffentlichen Anhörung des Innenausschusses des Deutschen Bundestages am 25. Mai 2020 in Berlin. Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat, Ausschussdrucksache 19(4)502 A. Deutscher Bundestag. https://www.math.uni-augsburg.de/htdocs/emeriti/pukelsheim/2020Berlin/A-092-Sitzung-Drs-19-4-502-A-Behnke1.pdf.

- Bock, Michael. 2017. “Landesvize der CDU-Frauen tritt zurück.” Volksstimme. May 7. https://www.volksstimme.de/sachsen-anhalt/streit-landesvize-der-cdu-frauen-tritt-zurueck.

- Böhmer, Maria. 2008. “Die Arbeit der Frauen Union der CDU: ‘Mut zur Macht in Frauenhand.’” Die Politische Meinung, November 23. https://www.frauenunion.de/sites/www.frauenunion.de/files/downloads/mut_zur_macht_in_frauenhand_60_jahre_fu_.pdf.

- Brandt, Mathias. 2018. “Merkel IV fast paritätisch besetzt.” Statista Infografiken. March 29. https://de.statista.com/infografik/13061/zusammensetzung-der-bundeskabinette-seit-1961/.

- Bundeswahlleiter. 2017. Wahl zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag am 24. September 2017: Sonderheft Wahlbewerber. Die Wahlbewerberinnen und Wahlbewerber für die Wahl zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag. Informationen des Bundeswahlleiters, September. https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/dam/jcr/f44145b0-99b6-4e87-bec9-b8c7dd4aa79a/btw17_sonderheft_online.pdf.

- Bundeswahlleiter. 2018. Ergebnisse früherer Bundestagswahlen. Informationen des Bundeswahlleiters. November. https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/en/dam/jcr/397735e3-0585-46f6-a0b5-2c60c5b83de6/btw_ab49_gesamt.pdf.

- CDU. 2007. Das Frauenquorum in der CDU. CDU-Bundesgeschäftsstelle Berlin. https://www.fu-steinburg.de/sites/www.fu-steinburg.de/files/docs/frauenquorum.pdf.

- CDU. 2015. Bericht zur politischen Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern. 28. Parteitag der CDU. https://www.cdu.de/system/tdf/media/dokumente/bericht-zur-gleichstellung.pdf?file=1.

- CDU. 2018. Bericht zur politischen Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern. 31. Parteitag der CDU. https://www.cdu.de/system/tdf/media/dokumente/ov_gleichstellungsbericht_31_parteitag_2018.pdf?file=1.

- CDU. 2019. Bericht zur politischen Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern. 32. Parteitag der CDU. https://www.frauenunion.de/sites/www.frauenunion.de/files/gleichstellungsberichte/ov_32._parteitag_2019_gleichstellungsbericht_ansicht_0.pdf.

- CDU. 2020. Beschlossene Vorschläge der CDU Struktur- und Satzungskommission der CDU Deutschlands. https://www.cdu.de/system/tdf/media/beschlossene_vorschläge_struktur-und_satzungskommission_0.pdf?file=1&type=field_collection_item&id=21332.

- Celis, Karen, and Sarah Childs. 2014. Gender, Conservatism and Political Representation. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

- Celis, Karen, and Sarah Childs. 2020. Feminist Democratic Representation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Celis, Karen, Sarah Childs, Johanna Kantola, and Mona Lena Krook. 2014. “Constituting Women’s Interests through Representative Claims.” Politics & Gender 10 (2): 149–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000026.

- Childs, Sarah, and Joni Lovenduski. 2013. “Representation.” In Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics, edited by Georgina Waylen, Karen Celis, Johanna Kantola, and Laurel S. Weldon, 489–513. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coffé, Hilde, and Louise K. Davidson-Schmich. 2020. “The Gendered Political Ambition Cycle in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3 (1): 79–99.

- Coffé, Hilde and Marion Reiser. 2018. Unterstützen die Bürger*innen die Einführung von Quoten und anderen Gleichstellungsmaßnahmen in Deutschland? MIP Zeitschrift für Parteienwissenschaften 2: 180–185.

- CSU. 2017a. Landesversammlung der Frauen-Union der CSU 6./7.10.2017. Frauen-Union der CSU. https://www.fu-bayern.de/common/fu/content/Aktuelles/PDF/Antraege2017.pdf.

- CSU. 2017b. Nachtragsbuch zur Landesversammlung der Frauen-Union der CSU. Frauen-Union der CSU. https://www.fu-bayern.de/common/fu/content/Publikationen/Nachtragsbuch_fuer_LV_2017.pdf.

- Dahlerup, Drude. 1988. “From a Small to a Large Minority: Women in Scandinavian Politics.” Scandinavian Political Studies 11 (4): 275–298.

- Davidson-Schmich, Louise K. 2016. Gender Quotas and Democratic Participation: Recruiting Candidates for Elective Offices in Germany. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Davidson-Schmich, Louise K. 2018. “Addressing Supply-Side Hurdles to Gender-Equal Representation in Germany.” Femina Politica 27 (2): 53–70.

- Geiger, A. W., and Lauren Kent. 2017. “Number of Women Leaders around the World Has Grown, but They’re Still a Small Group.” Fact Tank: News in the Numbers. Pew Research Center, March 8. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/08/women-leaders-around-the-world/.

- Henninger, Annette. Forthcoming. “Marriage Equality in Germany: Conservative Normalization Instead of Successful Anti-Gender Mobilisation.” German Politics.

- Henninger, Annette, and Angelika von Wahl. 2014. “Grand Coalition and Multi-Party Competition: Explaining Slowing Reforms in Gender Policy in Germany (2009–13).” German Politics 23 (4): 386-399.

- Hien, Josef. 2014. “Christian Democratic Party Feminisation: The German Christian Democratic Union and the Male Breadwinner Model.” In Gender, Conservatism and Political Representation, edited by Karen Celis, and Sarah Childs, 41–62. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

- Höhne, Benjamin. 2017. “Wie stellen Parteien ihre Parlamentsbewerber auf? Das Personalmanagement vor der Bundestagswahl 2017.” In Parteien, Parteiensysteme und politische Orientierungen, edited by C. Koschmieder, 227–253. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Höhne, Benjamin. 2020. “Frauen in Parteien und Parlamenten: Innerparteiliche Hürden und Ansätze für Gleichstellungspolitik.” Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 38. https://www.bpb.de/apuz/315247/frauen-in-parteien-und-parlamenten.

- Jenichen, Anne. 2018. “Muslimische Politikerinnen in Deutschland: Erfolgsmuster und Hindernisse politischer Repräsentation.” Femina Politica 27 (2): 70–82.

- Juvonen, Tuula. 2019. “Out and Elected: Political Careers of Openly Gay and Lesbian Politicians in Germany and Finland.” Redescriptions: Political Thought, Conceptual History and Feminist Theory 19 (1): 49–71.

- Kintz, Melanie. 2019. “Front Row or Backbench? The Access to Leadership Positions of CDU Women in the Merkel Era.” In Presentation for ECPG Conference Amsterdam.

- Lang, Sabine. 2018. “Gender Quotas in Germany: Diffusion, Derailment, and the Quest for Parity Democracy.” In Transforming Gender Citizenship: the Irresistible Rise of Gender Quotas in Europe, edited by Eléonore Lépinard, and Ruth Maria Rubío, 279–307. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lang, Sabine, and Petra Ahrens. 2020. “Paritätsgesetz oder Wahlrechtsreform? Warum Deutschland beides braucht.” In Rechtshandbuch für Frauen- und Gleichstellungsbeauftragte, edited by Sabine Berghahn, and Ulrike Schultz. Dashoefer: Hamburg.

- Lang, Sabine. 2017. “Gender Equality in Post-Unification Germany: Between GDR Legacies and EU-Level Pressures.” German Politics 26 (4): 556–573.

- Lépinard, Eléonore and Ruth Maria Rubío (eds.). 2018. Transforming Gender Citizenship: the Irresistible Rise of Gender Quotas in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Merkel, Angela. 2018. “Rede von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel.” Presented at 100 Jahre Frauenwahlrecht. https://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/bkin-de/aktuelles/rede-von-bundeskanzlerin-merkel-bei-der-festveranstaltung-100-jahre-frauenwahlrecht-am-12-november-2018-1548938.

- Mushaben, Joyce M. 2017. Becoming Madam Chancellor: Angela Merkel and the Berlin Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mushaben, Joyce M. Forthcoming. “Against All Odds: Angela Merkel, Ursula von der Leyen, Anngret Kramp-Karrenbauer and the German Paradox of Female CDU Leadership.” German Politics.

- Niedermayer, Oskar. 2017. “Parteimitglieder in Deutschland: Version 2017.” Arbeitshefte aus dem Otto-Stammer-Zentrum 27. doi:https://doi.org/10.17169/refubium-25183.

- Och, Malliga. 2018. “Conservative Feminists? An Exploration of Feminist Arguments in Parliamentary Debates of the Bundestag.” Parliamentary Affairs 72 (2): 353–378.

- Phillips, Anne. 1995. The Politics of Presence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland. 2018. “Frauen Union - Merkel erklärt höheren Frauenanteil zur Existenzfrage.” Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten. May 5, 2018. https://www.dnn.de/Nachrichten/Politik/Merkel-erklaert-hoeheren-Frauenanteil-zur-Existenzfrage.

- Saward, Michael. 2020. Making Representations: Claim, Counterclaim and the Politics of Acting for Others. Colchester, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Scharf, Ulrike. 2020. “Ohne Frauen ist keine Volkspartei zu machen.” CSU Frauen-Union. October. https://www.fu-bayern.de/aktuelles/oktober-2020/ohne-frauen-ist-keine-volkspartei-zu-machen/.

- Von Wahl, Angelika. Forthcoming. “From Private Wrongs to Public Rights: The Politics of Intersex Activism in the Merkel Era.” German Politics.

- Widmann-Mauz, Annette. 2018. “‘Ich packe das und kandidiere!’: Ein Impuls aus Anlass von 100 Jahren Frauenwahlrecht.” Die Politische Meinung, October 10. https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/253252/7_dokument_dok_pdf_53670_1.pdf/60824508-95db-dcbf-823d-4c3458dd3106?t=1539646924415.

- Wiliarty, Sarah Elise. 2010. The CDU and the Politics of Gender in Germany: Bringing Women to the Party. New York: Cambridge University Press.