Abstract

German governments, dominated by the conservative CDU/CSU, have historically not been at the forefront in recognising LGBTI rights in Europe. Yet, significant advances have occurred under Angela Merkel’s leadership since 2005. This article seeks to understand the conditions under which these unexpected advances have occurred, to what degree Merkel and her government facilitated or obstructed them, and which groups benefitted from these advances. I use parliamentary questions, coalition agreements and party programmes to map the expansion of LGBTI rights and the forces Merkel and her government had to navigate. Comparing the four terms of Merkel’s chancellorship, I find that she played a passive or indirectly facilitating role, only moving on LGBTI issues when pressured by international norms, the Federal Constitutional Court or electoral pressure. Although LGBTI interests are increasingly visible on the political agenda, the advances made did not benefit all groups under the LBGTI-umbrella equally, as bisexual, trans* and intersex interests remain mostly invisible. Taking a birds-eye view of Merkel’s chancellorship I illustrate how and what kind of change can occur under conservative-led governments.

Introduction

The landscape of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans* and intersex (LGBTI)Footnote1 representation in Germany has changed dramatically since the first Angela Merkel cabinet. German governments, dominated by the conservative Christian Democrats, have historically been slower than other nations to recognise LGBTI rights. Yet, significant advances have occurred under Merkel’s leadership since 2005, though not always benefitting all groups assembled under the acronym equally. This article seeks to understand the conditions under which these unexpected advances have occurred, to what degree Merkel and her governments facilitated or obstructed them, and which groups benefitted from these advances.

Scholarship analysing the expansion of LGBTI rights has emphasised the importance of both domestic politics and international pressure (Kollman Citation2013; Ayoub Citation2016) and the effects of judicial change (Helfer and Voeten Citation2018). Charting the dynamics behind LGBTI rights’ expansion during Merkel’s tenure, I analyse major policy changes and the visibility of issues on the political agenda. To map the visibility of LGBTI interests, I collected parliamentary questions, submitted to the Bundestag since 2005 that reference LGBTI interests. Using qualitative thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke, and Terry Citation2015), I combine this dataset with coalition agreements and party programmes to map the forces Merkel had to navigate, analyse the driving factors behind policy milestones and identify the groups that benefitted from them.

Merkel has been described as the ‘chancellor of the heterosexuals’ (Berliner Morgenpost, July 12, 2008) and advances in LGBTI legislation have not been initiated by her. Merkel not only had to navigate increasing pressure from the opposition bringing LGBTI rights issues to the table but also changing international dynamics. I find Merkel played a passive or indirectly facilitating role (see introduction, this issue), expanding LGBTI legislation with reluctance by simply not blocking proposals or when forced by the Federal Constitutional Court, international pressure or electoral politics. The resulting policy often only just complies with rulings of the Constitutional Court or EU mandates and is not as comprehensive as LGBTI activists’ demands. The German case thus shows more inclusive change does not necessarily stem from domestic political ideals to enhance LGBTI rights or from responsiveness to political consensus, but from external pressure to comply with international human rights norms.

However, the advances made did not benefit all groups under the LBGTI-umbrella equally. Comparing the four terms of Merkel’s chancellorship, I find that LGBTI interests are increasingly visible on the German political agenda. Studying LGBTI representation requires particular attention to answering which groups and what interests we are talking about specifically (Paternotte Citation2018). Those who do not fit the prototypes of their groups can experience intersectional invisibility (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Citation2008). For example, in pursuing marriage equality as a movement goal, lesbian and gay movements have often framed their goals from a homonormative perspective (Duggan Citation2002) that privileges the more normative monogamous married couples and reproduces gender roles at the expense of those that are less normative (Browne and Nash Citation2014). Intersectionally analysing LGBTI representation during the Merkel era reveals hierarchies within the representation of the different groups under the LGBTI-umbrella. I find gay men and to a lesser extent lesbian women take centre stage on the political agenda. Additionally, the parliamentary data shows the opposition parties focus strongly on foreign policy and LGBTI rights violations abroad, and do not exert as much pressure on domestic matters. Most advances in LGBTI rights under Merkel’s leadership did not benefit the most marginalised, who are often absent from the political agenda, although I find that visibility for the most marginalised groups under the LGBTI-umbrella does increase over time. Taking an intersectional approach to LGBTI representation contributes to our understanding of mechanisms of political representation of marginalised groups, because it demands zooming-in on within-group variation and contextualising the way visibility works. Additionally, comparing the milestones in legislation and the visibility of LGBTI interests during Merkel’s chancellorship reveals how more inclusive change can occur under conservative-led governments.

In the following, I provide a theoretical framework followed by the methodological approach. The empirical body charts the issues that reached the political agenda and major policy changes and the driving forces behind them. It assesses Merkel’s role in these advancements and analyses which groups mostly benefitted from them, providing a unique bird’s eye view to LGBTI policy change over almost two decades.

Understanding LGBTI Policy Change

To explore the Merkel era from the perspective of LGBTI interests, I draw on theories of substantive representation, LGBTI politics, and intersectionality. In the fields of representation theory and intersectionality, sexuality and gender identity are often mentioned, for example in enumerations of possible axes of disadvantage and privilege. However, sexuality and gender identity are seldom the central focus and when gender is discussed, it often refers solely to women’s rights. I contribute to these bodies of work by unpacking the domestic and international conditions under which LGBTI rights were expanded during Merkel’s tenure, with an intersectional focus on which interests gained visibility.

Visibility of LGBTI Interests on the Political Agenda

Research on political representation rarely includes sexuality or gender identity as a lens (Ahrens et al. Citation2018). Exceptions often focus on the role of descriptive representatives, or the presence of ‘out’ LGBTI politicians in national parliaments (Reynolds Citation2013). Haider-Markel (Citation2010) studies involvement of gay men and lesbian women in electoral politics in the United States and Tremblay (Citation2019) shows how out lesbian, gay and bisexual members of parliament in Canada envision their representative roles. Hunklinger and Ferch (Citation2020) offer an alternative view to the predominance of North American-focused work in this domain by analysing the political preferences, attitudes and voting behaviour of trans* people in Germany. Substantive representation refers to what parliamentarians do and what interests they represent. Substantive representation refers to ‘acting in the interests of the represented in a manner responsive to them’ (Pitkin Citation1967, 209). However, studies of the way LGBTI citizens are substantively represented are scarce (but see Bönisch Citation2021 and Hansen and Treul Citation2015 for an exception).

I aim to contribute to this body of work by analysing the visibility of LGBTI interests on the political agenda and the policy measures that were introduced during the Merkel era. To do so, I use parliamentary questions and unpack what issues and interests gained visibility. The submission of parliamentary questions has been used as an indicator of substantive representation (Bönisch Citation2021; Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Citation2019; Saalfeld Citation2011). Representatives can use parliamentary questions to include the interests of certain groups in the legislative process and demonstrate responsiveness to the concerns of minoritised citizens (Saalfeld and Bischof Citation2013). Especially in the case of the Bundestag during Merkel and her party’s conservative leadership, political opportunities for the substantive representation of LGBTI interests may be slim. Parliamentary questions provide an important representative tool and allow me to map what opposition Merkel encountered.

International and Judicial Change

The visibility of LGBTI interests on the national political agenda alone cannot explain the advances in LGBTI rights made during the Merkel era, as she also had to navigate international or judicial pressure. Actors such as courts, activists and international organisations together with changing societal norms influenced Merkel’s passive facilitation of LGBTI rights advancement. Scholars of LGBTI politics have identified conditions under which advances in LBGTI legislation can occur (Ayoub Citation2016; Paternotte and Kollman Citation2013). As the introduction of marriage quality in Germany also shows (see introduction, this issue), domestic politics is influenced by international dynamics, which also shape Merkel’s decision-making (Lemke and Welsh Citation2018). Germany’s connection to its international community, both through the influence of other states and through its membership in international organisations that advance LGBTI rights, creates pressure to adopt similar policies on the national level. These mechanisms are especially effective in a state like Germany that is committed to its reputation and human rights record, especially given its history (Kollman Citation2014). External pressure combined with domestic political opposition or activism can force reluctant German governments into implementing more inclusive policies and expanding LGBTI rights (Davidson-Schmich Citation2017; Schotel and Mügge Citation2021).

Scholars have identified judicially motivated change as another important factor in explaining the expansion of LGBTI rights (Helfer and Voeten Citation2018; van der Vleuten Citation2014). Aside from international pressure, Merkel and her government have had to navigate rulings of the Federal Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The Constitutional Court has especially been a driving factor of the expansion of LGBTI rights during the Merkel era, consistently chipping away at LGBTI equalities. ‘Going to Karlsruhe’ has become an important tool for political parties, state governments and activists to challenge policies (Lemke and Welsh Citation2018, 47). For example, Germany became the first country in Europe to introduce a non-binary option for registering legal sex, after the Constitutional Court forced the government into action (‘Intersex rights’, this issue). A combination of domestic politics, judicial demands and international pressure can create a window of opportunity for LGBTI rights expansion that pushes Merkel into her role of passive facilitation.

Intersectionality

During the Merkel era, unexpected advances in LGBTI rights occurred. However, these advances did not benefit all groups under the LGBTI-umbrella equally. Whose interests actually reached the political agenda? I use the submission of parliamentary questions to shed light on structural inequalities in the visibility of LGBTI interests over time.

Intersectionality theory provides a perspective on the way experiences of inclusion and exclusion are shaped by the interaction of categories such as gender, race and class (Crenshaw Citation1997; Hill Collins Citation1998). The intersection of these categories creates specific positions of marginalisation and privilege, depending on the context in which they operate. People with identities that do not match normative frameworks of gender and sexuality face a variety of disadvantages because legislative and institutional structures are built on heterosexuality and gender binarism, limiting the possibilities of moving outside of the mainstream (Monro Citation2005). However, even outside of the mainstream, experiences of disadvantage and privilege differ for the groups contained within the LGBTI-umbrella. As Altman argues: ‘We cannot use the acronym as if there were clear boundaries to these categories (…)’ (Citation2020, 452). There have been longstanding tensions between all groups included within the acronym, as well as rapidly changing categories and new emerging identities. The use of the acronym is criticised for claiming inclusivity, but in practice only referring to some, for example (white) gay men. Bisexuality has historically been marginalised and the inclusion of the T is problematic, as a person with trans* experiences may also be located within the L,G or B parts of the acronym (Murib Citation2017; Hunklinger and Ferch Citation2020). Considering LGBTI citizens as one homogenous group risks obfuscating within-group inequalities. An intersectional approach underlines the need to expose the way such homogenous conceptions of groups privilege the experiences of some over others (Hancock Citation2007), which the case of the German Bundestag provides.

To unpack which interests gain visibility during the Merkel era, I build on work in social psychology that has operationalised intersectionality to analyse within-group differences (Parent, DeBlaere, and Moradi Citation2013; Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Citation2008). This framework is especially useful for studying LGBTI representation as it highlights hierarchies among members of identity groups. Because those with multiple subordinate identities, such as lesbian women, do not fit the prototypes of either of their identity groups they can experience intersectional invisibility (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Citation2008). Representatives devote less attention and resources to constituents that are not archetyical members of their identity group (Strolovitch Citation2007). Cohen argues: ‘certain segments of the population are privileged with regard to the definition of political agenda’s’ (Citation1999, 11). I use to the concept of intersectional invisibility to analyse which interests reach the political agenda in the Bundestag during the Merkel era.

Methods

To map the advances in LGBTI legislation during the Merkel era, I combine parliamentary questions, coalition agreements and electoral programmes for each legislative period. The major policy milestones that were achieved during this timeframe serve as anchor points to provide a snapshot of the different actors influencing Merkel’s decision-making at the time.

Parliamentary questions have been operationalised as an indicator of substantive representation of minoritised groups (Chaney Citation2013; Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Citation2019; Bönisch Citation2021) and allow me to map the political agenda on LGBTI rights Merkel and her party had to navigate during her time as Chancellor. Parliamentary questions are an important representative instrument since the member of cabinet addressed in a written question is obliged to answer, making questions an effective method for generating attention to certain issues and influencing the political agenda (Bird Citation2005; Saalfeld Citation2011). I retrieved minor interpellations (Kleine Anfragen) and written questions (Schriftliche Fragen) from the online database of the German parliament,Footnote2 using a search string with the timeframe of 22-01-2005–01-04-2020 since the fourth legislative period is ongoing at the time of writing.Footnote3 The search strings were constructed inductively by starting with parliamentary questions containing common key words (such as lesben, schwule, bisexuelle and transgender) and adding them until no new keywords were identified. Because parliamentary questions are mostly an instrument of the opposition, coalition agreements of all four Merkel governments were also included in the analysis. Additionally, I collected the electoral programmes of parties that won seats in 2005, 2009, 2013 and 2017 national elections using the Manifesto Project database (Volkens et al. Citation2019). The parties are Die Linke, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, FDP, CDU/CSU and AfD. Electoral programmes provide a useful snapshot of the ambitions, if there are any, for LGBTI equality and can influence activism by shaping available policy opportunities (Carabine and Monro Citation2004). Data was coded in MAXQDA and analysed using qualitative thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke, and Terry Citation2015). The coding process was semi-inductive to remain open to the full range of themes that might be relative to sexual minorities, without assuming what their exact preferences on these issues are. Specific attention was paid to references to relevant themes and actors, such as the Constitutional Court or international treaties, identified from the literature (see for example Davidson-Schmich Citation2018), and adding themes that emerged from the data.

In what follows, I explore the domestic and international conditions under which LGBTI policy changes occurred, unpack whose interests gained visibility and whose did not and how Merkel and her government navigated these dynamics.

LGBTI Representation During the Merkel Era

Historically, Germany has been characterised as a laggard in implementing LGBTI equality measures. Still, LGBTI rights have been expanded in Germany since the beginning of the Merkel Era in 2005. After describing some general trends, the next section will explore the conditions under which LGBTI rights were expanded for each of the legislative periods under Merkel’s leadership, analyse Merkel’s role in them and chart which groups under the LBGTI-umbrella benefitted from them.

Despite the CDU/CSU dominance, major changes such as the introduction of marriage equality in 2017, have created greater visibility for diversity in gender identity and sexual orientation. LGBTI rights increasingly take up space on the political agenda. Looking at the Merkel era as a whole, I find the number of parliamentary questions submitted on the topic of LGBTI interests has steadily increased since 2005 (see ). Still, a total of 385 questions (about 0.5 per cent) is an extremely small number compared to the total of written questions and minor interpellations (84461) submitted during this timeframe, which shows LGBTI equality remains a marginal issue in Germany.

Table 1. Overview of Merkel governments and milestones for LGBTI rights from 22-01-2005–01-04-2020 (n = 385).

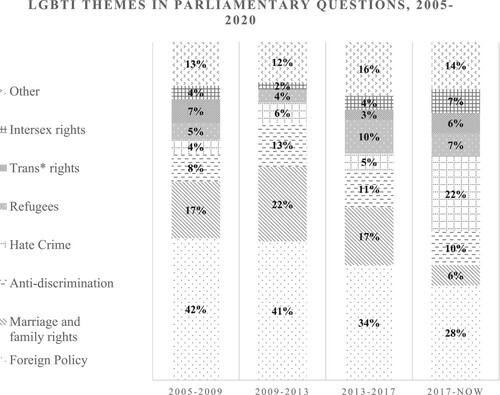

What specific interests did representatives address when they did put LGBTI interests on the agenda? I find that LGBTI interests are addressed within the following themes: (1) foreign policy; (2) marriage and family rights; (3) anti-discrimination policy and legislation; (4) hate crimes; (5) refugees and asylum policies; (6) trans* rights; (7) intersex rights; (8) religion; (9) healthcare and (10) government support and subsidies for LGBTI advocacy; (11) reparations for the prosecution of LGBTI people during or after the Nazi-regime and (12) education on LGBTI rights (in order of prominence). shows the most prominent thematic areas and their visibility on the political agenda over time.

Figure 1. Overview of most prominent LGBTI themes found in minor interpellations (Kleine Anfragen) and written questions (Schriftliche Fragen) during the four legislative periods of the Merkel era from 22-01-2005–01-04-2020 (n = 385).

Looking at the topics of parliamentary questions over time shows that foreign policy dominates the political agenda throughout the Merkel era. The overwhelming majority of questions submitted on LGBTI issues address the protection of gay men and sometimes lesbian women in the Global South. LGBTI interests within domestic affairs are far less visible. Strikingly, the number of questions on foreign policy is lowest when Germany had an openly gay Minister of Foreign Affairs in Guido Westerwelle (2009-2013). The focus on the human rights violations abroad has also been analysed as part of a homonationalist discourse, since it contrasts countries in the Global South with ‘gay-friendly’ nations such as Germany as modern and progressive states (Rahman Citation2019; Puar Citation2013). However, most parliamentary questions on foreign policy are submitted by the Greens, who do not combine this focus with a nationalist ideology. On the other side of the political spectrum, AfD only submits one question on foreign policy and does not use a homonationalist frame either.

Whose interests gain visibility during the Merkel era? I find that the most privileged groups under the LGBTI-umbrella, gay men and lesbian women, are also the centre of concern in questions on the other dominant themes: marriage and family rights and anti-discrimination policies. Bisexuality is mentioned in explaining the abbreviation LGBTI or LSBT, but the specific interests of bisexual people are completely absent from the political agenda in all four legislative periods. Trans* and intersex experiences as well as the position of LGBTI refugees or migrants in Germany are only addressed in a very small number of questions. The interests of senior LGBTI citizens or those with disabilities are also not mentioned. Although attention to their interests does increase, these hierarchies reveal that those with multiple subordinate identities experience the most invisibility.

The next section zooms in on these trends for each legislative period, addressing major policy advancements and mapping the forcefield of domestic politics, judicial change and international pressure Merkel had to navigate.

Merkel I: A Coalition of Standstill, 2005–2009

Looking through the lens of LGBTI interests, Germany looked vastly different in 2005 than it does now. For example, registered life partnerships for same-sex couples had been introduced in 2001, but lacked the same tax and inheritance benefits, marriage and adoption rights granted to heterosexual couples.

At the start of the Merkel era, the CDU/CSU reluctantly forms a Grand Coalition with the SPD. The FDP, the Greens and Die Linke make up the opposition. The coalition agreement does not contain any statements on LGBTI rights (CDU/CSU/SPD Citation2005), which is reflective of this legislative period as a whole. Merkel is described by Green Party Leader Roth as a ‘chancellor of heterosexuals’ (Berliner Morgenpost, July 12, 2008) and in parliamentary questions on unequal rights of same-sex couples in registered partnerships submitted by the FDP, the government is called a ‘coalition of standstill’ (FDP Citation2006).

Besides the lack of leadership of Merkel and her government, the opposition also demonstrates a lack of action. The number and type of parliamentary questions submitted during this legislative period indicate the experiences of LGBTI citizens are a marginal issue on the political agenda. MPs do not use the abbreviation LGBTI or LSBT yet. Parliamentary questions mostly address the challenges gay men and sometimes lesbian women face while the interests of other groups remain invisible. Most of the questions submitted during this period are focused on human rights violations of gay men in the Global South and Turkey. Although Germany lags behind other European countries during the first of Merkel’s cabinets, the opposition does not pressure the government as much on the inequalities LGBTI citizens within Germany face. The Greens do question the government on marriage equality and family rights, which is the second most addressed topic during this time, pushing for full equality after the introduction of registered partnerships in 2001. The position of LGBTI people with a migration background is also absent from the political agenda, except for questions submitted by the Greens critiquing the labelling of countries safe to return to for gay male asylum-seekers, despite a risk of persecution.

Despite the narrow focus of the parliamentary questions, this period does feature two important changes for LGBTI people in Germany. In 2006, the controversial Equal Treatment Act (Allgemeine Gleichbehandlungsgesetz) comes into force, which now includes sexual orientation as a grounds for protection against discrimination, despite strong and sustained opposition from the CDU/CSU. The Act was not the result of steps taken by the government to protect LGB citizens or pressure from the opposition; instead, Germany was ‘whipped into it by only EU dictate’ (Joppke Citation2007, 255).

The second milestone during this legislative period, the amendment of the Transsexual Act (Transsexuellegesetz) was also not achieved through political action but through international developments and judicial change. Following previous ECtHR-rulings and international standards such as the Yogyakarta Principles, the Constitutional Court rules in 2008 that the requirement within the Transsexual Act for changing a person’s registered sex that the applicant not be or no longer be married, was unconstitutional. This results in practice in ‘Ehe für alle in Transfällen’. However, the Act still requires sterilisation and surgical interventions for legal sex registration changes at that time. Earlier in 2008, the FDP had already pressured the government to act and strike these requirements, highlighting violation of the right to self-determination and the need for extensive reforms given the fact that the Act had remained unchanged since 1981. This pattern contributes to answering how more inclusive policies came to be introduced despite the Merkel government’s inertia; these unlikely changes are the result of judicial coercion from the Constitutional Court or international pressure, while Merkel only played a (barely) passively facilitating role.

Merkel II: Reluctant Change, 2009–2013

After the 2009 election, Merkel is able to form her second cabinet with the CDU/CSU’s preferred partner, the FDP, moving the coalition towards the centre-right. A double majority in the Bundestag and the Bundesrat enables the coalition to continue to pursue more conservative policies (Mushaben Citation2016). Merkel does appoint FDP-leader Guido Westerwelle, who became the first openly gay minister of foreign affairs and vice-chancellor. Nevertheless, the coalition agreement is silent on LGBTI interests with two exceptions: FDP and CDU/CSU commit to ‘reduce discrimination in tax law and in particular, to implement the decisions of the Constitutional Court on the equality of life partners and spouses’ and to follow the Constitutional Court in implementing reform of the Transsexual Act (CDU/CSU/FDP Citation2009, 108). Similar to the previous legislative period, the Constitutional Court acts as the main driver of more inclusive legislation and the initiative of the Merkel government is limited to meeting the Court’s requirements.

The number of parliamentary questions submitted on LGBTI interests during the second Merkel cabinet decreases, compared to the previous governing cycle. Despite earlier attempts of the FDP to further LGBTI rights, the governing coalition now resists further improvements, for example by repeatedly blocking proposals of the Greens and Die Linke to equate registered partnerships and marriage rights. However, questions submitted during this period also show the opposition starts to exert increasing pressure. MPs start to widen their frames beyond the interests of gay men and lesbians. In 2010, the abbreviations LSBT or LSBTI and LGBT are used for the first time. Parliamentary questions now also include specific questions on intersex or trans* concerns. Especially the Greens and Die Linke start to demonstrate intersectional awareness and include other interests than those of the ‘prototypical’ minority in their questions (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Citation2008).

Despite the use of the new label LSBT, the most prominent theme during this time remains foreign policy and only addresses human rights violations of gay men abroad. Marriage and family rights are the second most visible. While in 2010, the minister of Family Affairs Kristina Schröder (CDU) declares that ‘it is vital for children’s development to be raised by both sexes’ (The European, 2010, October 20), in 2013 adoption rights for same sex partners are nevertheless expanded. Both Die Linke and the Greens previously addressed the privileging of heterosexual couples in their parliamentary questions, which according to the government served the ‘normative purpose’ of prioritising the institution of marriage. However, attempts to equate registered partnerships with full marriage rights are still consistently blocked by the CDU/CSU, until marriage equality becomes a reality in 2017.

The two major advances in LGBTI rights made during this legislative period are both the result of rulings by the Constitutional Court. First, in 2011 the Court declared parts of the Transsexual Act (Transsexuellengesetz), that required sterilisation or gender reassignment surgery for legal gender recognition to be unconstitutional as they violate the right to physical integrity. Leading up to the ruling, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), Commissioner of Human Rights and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe had already expressed concerns at these requirements. Second, in 2013 the Constitutional Court ruled that members of a civil partnership should be able to adopt their partners stepchild or adoptive child. In practice, same-sex couples could now adopt children individually, though not yet as a couple. Where Merkel and her party usually explicitly reject or strategically ignore the need for increased LGBTI-rights, under pressure from the UN, EU or Constitutional Court, arguments based on human rights principles can outweigh this internal logic, albeit reluctantly.

Merkel III: Increased Visibility, 2013–2018

During the third Merkel cabinet, LGBTI interests moved closer to the centre of the political agenda, illustrated by the most parliamentary questions submitted on the topic to date. The third Merkel cabinet consists of another Grand Coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD, after the FDP faced a sweeping electoral loss. The coalition agreement now contains a paragraph on ‘rainbow families’, but does not mention marriage equality despite earlier demands of the SPD. Yet, it does state the coalition partners aim to ‘take into account the particular position of trans- and intersexual people’ (CDU/CSU/SPD Citation2013, 74). This specific consideration can partly be explained by another ruling of the Constitutional Court in 2013, which declared parents of intersex children should be able to leave the registered legal sex of their child blank (see ‘Intersex rights’, this issue).

Despite the lack of ambition of the coalition, several important steps are made during this period. The introduction of full marriage equality in 2017 is the most prominent of these. The political struggle for marriage equality has been analysed from several perspectives already (see introduction, this issue; Davidson-Schmich [Citation2018]), and an in-depth analysis lies outside the scope of this article. Important to note is that despite this major milestone, most parliamentary questions submitted during this period still addressed foreign policy and not marriage and family rights. Again, the introduction of marriage equality is not the result of a widely shared political consensus, the government’s responsiveness to LGBTI citizens or a ruling from the Constitutional Court. In 2013, marriage equality has become a central point in the election race. During the campaign, party leaders of SPD, the Greens and FDP make ‘Ehe für Alle’ a precondition for entering a coalition. When pressed on the issue at an election event, Merkel surprisingly states she would allow for a conscience vote. SPD-leader Schulz responds by directly calling for the vote and the marriage equality bill is passed with a large majority on 30 June 2017. Seventy-five Christian Democrats vote in favour, Merkel herself votes against. Her manoeuvring in response to multi-level pressure, conforming to the party line by voting against the Marriage Equality Act herself while expecting it to pass, is illustrative of her role of passive facilitation during this legislative period and her Chancellorship.

The scope of LGBTI interests on the political agenda widens and intersectional consciousness seems to expand. Parliamentary questions now demonstrate more awareness to those at invisible intersections, for example underlining the need to explicitly consider sexual orientation and gender identity in anti-discrimination legislation by the Greens or to protect LGBTI asylum-seekers by Die Linke. In only two interpellations on LGBTI rights in foreign policy multiple axes of inequality are considered. The Greens include a question on statistics on ‘transsexual asylum-seekers’ from Honduras (2015) and Die Linke ask about police violence against trans* people in Turkey (2016). Questions also show increased attention to the specific position of people with trans* experiences. Several Green MPs explicitly reflect on possible further marginalising trans* experiences by using LGBTI as a blanket term and ask which part of the budget for LGBTI counselling centres is reserved specifically for supporting trans* people. Still, trans* and intersex people are often treated as a homogenous group. For example, Die Linke MPs ask the government what support exists for those ‘in between the sexes’ (Citation2016, 2). Once again, international standards also provide ammunition for MPs to pressure the government. In 2014 the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance reprimands the federal government for failing to address hate crimes and discrimination against LGBTI people. The report also critiques the differences between the rights of registered partners and married couples, which the Greens use to pressure the government into taking concrete steps to combat these issues.

Merkel IV: Gender ‘Ideology’ and Self-Determination, 2017–2021

During the fourth and, at time of writing current, Merkel cabinet, the variety in parliamentary questions illustrates more polarisation but also increased intersectional awareness of LGBTI interests. The dominance of the CDU/CSU continues in 2017, when Merkel is able to form another Grand Coalition with the SPD. The coalition agreement again contains few specific references to topics related to LGBTI equality. While often overlooked, the coalition partners do specifically mention the position of those with intersex characteristics, and declare their commitment to the ruling by the Constitutional Court earlier in 2017 which introduced a ‘third’ option for registering legal sex (CDU/CSU/SPD Citation2018, 21, see ‘Intersex rights’, this issue).

While this legislative period is still ongoing at the time of writing, the number of parliamentary questions submitted on LGBTI themes has increased compared to previous governing cycles. Similar to the previous legislative periods, foreign policy occupies most of the political agenda. After the introduction of marriage equality in 2017, the number of questions on marriage and family rights decreases and instead anti-discrimination legislation and combatting hate crime appear prominently.

During the final governing cycle of the Merkel era, LGBTI rights are expanded in several ways. Surprisingly, CDU-Minister of Health Jens Spahn, who is considered a leading figure of the conservative wing of the CDU, is at the forefront of the instalment of a ban on conversion therapy, an important milestone for LGBTI representation. Spahn, who is openly gay, announced the ban in 2019 and the Bundestag adopted the Act to Protect against Conversion Treatments in May 2020, prohibiting medical interventions aimed at changing or ‘curing’ non-normative sexual orientations and gender identities. MPs from the Greens and Left Party had been submitting parliamentary questions on the topic since 2008. Volker Beck, MP for the Greens, had already proposed a bill in 2013 which failed to garner enough support after which the topic disappeared from the political agenda. Aside from the ban on conversion therapy, Spahn has accomplished other break-throughs, such as have state health insurance funds cover the costs for the pre-exposure HIV prevention drug (PreP).

In 2016, the 89th Conference of Health Ministers had put forward a proposal to remove the blanket ban on gay and bisexual men donating blood at the initiative of Saarland Health Minister Monika Bachmann (CDU). The German Medical Association headed the proposal in 2017 and men who have sex with men are now allowed to donate blood after they have abstained for twelve months. According to the opposition, these requirements discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation without medical necessity. Spahn has acknowledged the discriminatory nature of the rules on blood donation but refuses nonetheless to commit to further changes. Nonetheless, Spahn has been strongly criticised by LGBTI activists and these initiatives do not reflect a broader shift within the CDU/CSU.

Furthermore, as LGBTI rights become more visible, backlash also increases. For example, in 2017 the AfD proposes a bill to abolish marriage equality which was rejected. In one interpellation the AfD asks the government what international projects it has subsidised that support those that have been ‘diagnosed with a disturbed sexual identity’ (Citation2019, 2). Resistance against LGBTI equality has not only become more visible on the radical-right but also from conservatives. After having taken over party-leadership from Merkel, then CDU-leader Kramp-Karrenbauer, openly joked about the ‘third’ sex (Die Welt, March 3, 2019) and CDU-Minister of Education Karliczek argued for the need to scientifically investigate the harmful effects of growing-up in same-sex families on national television. Both received heavy political and public criticism for their outdated remarks. While Merkel has also explicitly opposed LGBTI-rights expansion, she has not evoked the same responses or scandals as her party members, which highlights her unique position. She has carefully maintained a balance between not alienating conservative party members while avoiding controversy with social progressives.

Conclusion

Significant advances have been made for LGBTI rights in Germany since the start of the Merkel era, despite resistance and reluctance of Merkel’s CDU/CSU. Looking at this era through the lens of LGBTI interests, this article analysed the conditions under which these advances could occur, mapped the forces Merkel had to navigate and unpacked which groups under the LGBTI-umbrella benefitted from increased visibility.

The advances for LGBTI rights cannot directly be attributed to Merkel, and as her role has consistently been one of passive facilitation. Under Merkel’s leadership, the German government has reluctantly had to adapt to an evolving international landscape of LGBTI rights that made strategic silence impossible. Besides reacting to international pressure, the government has time and time again been forced to implement change by the Federal Constitutional Court or by coalition restraints. Despite the fact that we cannot credit Merkel or her government for the expansion of LGBTI rights, it simply must be acknowledged that her politics have influenced until-recently-unthinkable possibilities for progressive change. Unlike other members of her party, Merkel has steered clear of controversy in the way she addresses LGBTI rights and has managed a balancing act that has facilitated opportunities for progressive change. Given the CDU/CSU’s dominance, the expansion of rights does not stem from intrinsic political ideals or public consensus, but from a sensitivity to and application of legal principles of equality and human rights norms, that Merkel especially seems to embody. Henninger and von Wahl (Citation2014) have illustrated how the expansion of gender equality policies stalled during the 17th legislative period, which aligns with my findings. The coalition with the FDP was the least productive for LGBTI rights expansion, illustrating the impact of coalition restraints. Research on women’s leadership in conservative also highlights the role of coalition governments for conservative women’s gender policy adoption (Och Citation2016). LGBTI rights were expanded most when Merkel was pushed by the SPD as coalition partner.

While significant reform was implemented during her tenure, I find that LGBTI rights remain a marginal topic on the political agenda and increased visibility is accompanied by backlash and contestation. Taking an intersectional approach, I find that when LGBTI interests do reach the political agenda during the Merkel era, gay men and to a lesser extent lesbian women take centre stage. Parliamentary questions throughout this time focus predominantly on the violations of human rights in the Global South and pay significantly less attention to domestic issues. The experiences of refugees or those with trans* experiences or intersex characteristics are increasingly addressed on the political agenda.

But many intersectionally invisible groups remain invisible: bisexuality, disability or race are almost completely absent from political agenda and trans* and intersex rights are often subsumed under ‘gender identity’ without explicit consideration. Although the Greens and Die Linke are increasingly championing LGBTI rights, the Left Party has never served in the national government and the Greens have been in the opposition since 2005. LGBTI citizens have therefore also had to rely on other actors such as social movements to take up their interests. This study has focused on the political, highlighting the actions of members of parliament and political parties. Future research is needed to take into account the demand side of representation (Celis and Mügge Citation2017; Hunklinger and Ferch Citation2020), such as the indispensable role LGBTI movements and advocacy groups play in securing policy change.

This bird’s eye view to the Merkel era has shown how expansion of LGBTI rights can occur under conservative-led governments. However, looking towards the future, a new CDU /CSU chancellor may not share Merkel’s strategic sensitivity that has reluctantly facilitated change in the past. In fact, the new leader of the CDU/CSU, Armin Laschet has opposed marriage equality and has been criticised for his connections with homophobic organisations (Der Spiegel, 12 July, 2021). My findings thus suggest there will only incremental change in the future, unless the Greens or Die Linke enter into a coalition or if a conservative government continues to be forced by the Federal Constitutional Court, making structural inclusion on the political agenda of the intersectionally invisible unlikely.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous versions of this paper and Mirte van Hout for her research assistance. This work was supported by the Amsterdam Centre for European Studies (ACES).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anne Louise Schotel

Anne Louise Schotel is a doctoral researcher in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam and the Germany Institute Amsterdam (Duitsland Instituut Amsterdam). Her work focuses on the political representation of sexuality and gender identity and LGBTI politics.

Notes

1 The use of acronyms such as LGBT or LGBTI is disputed. Gender identity should not be conflated with sexual orientations. I use LGBTI, not only for simplicity and recognisability, but also because lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans* and intersex interests are specifically discussed in the data. I use the term parliamentary questions broadly to combine both Kleine Anfragen (minor interpellations) and Schriftliche Fragen (written questions).

2 See https://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21.web/bt (last accessed 18-05-2020).

3 LSBT, LSBTI, LGBT, LGBTI, LSBTTI, LSBTTIQ, schwul, homosexual!, homosexuel!, lesben! or lesbisch! bisexuel!, bisexual!, transsexuel!, transsexual!, intersexuel!, intersexual!, intergeschlecht!, hetersexuel!, heterosexual!, geschlechtsidentität, homophob!, transphob!, lebenspartnerschaft! Exclamation marks are used for truncation.

References

- AfD. 2019. “Genderstrategie der Bundesregierung.” Drucksache 19/10539.

- Ahrens, Petra, Karen Celis, Sarah Childs, Isabelle Engeli, Elizabeth Evans, and Liza M. Mügge. 2018. “Politics and Gender: Rocking Political Science and Creating New Horizons.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 1 (1–2): 3–16.

- Altman, Dennis. 2020. “Academia Versus Activism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics, edited by Michael J. Bosia, Sandra M. McEvoy, and Momin Rahman, 451–462. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ayoub, Phillip M. 2016. When States Come Out: Europe’s Sexual Minorities and the Politics of Visibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bird, Karen. 2005. “Gendering Parliamentary Questions.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7 (3): 353–370.

- Bönisch, Lea Ewe. 2021. “What Factors Shape the Substantive Representation of Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals in Parliament? Testing the Impact of Minority Membership, Political Values and Awareness.” Parliamentary Affairs. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsab033.

- Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, and Gareth Terry. 2015. “Thematic Analysis.” In Qualitative Research in Clinical and Health Psychology, edited by Poul Rohleder and Antonia C. Lyons, 95–113. London: Macmillan.

- Browne, Katherine, and Catherine J. Nash. 2014. “Resisting LGBT Rights Where ‘We Have Won’: Canada and Great Britain.” Journal of Human Rights 13 (3): 322–336.

- Carabine, Jean, and Surya Monro. 2004. “Lesbian and Gay Politics and Participation in New Labour’s Britain.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 11 (2): 312–327.

- CDU/CSU/FDP. 2009. “Wachstum. Bildung. Zusamennhalt. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und FDP”.

- CDU/CSU/SPD. 2005. “Gemeinsam für Deutschland – mit Mut und Menschlichkeit. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD”.

- CDU/CSU/SPD. 2018. “Deutschlands Zukunft gestalten. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU/ CSU und SPD”.

- CDU/CSU/SPD. 2018. “Ein neuer Aufbruch für Europa. Eine neue Dynamik für Deutschland. Ein neuer Zusammenhalt für unser Land”. Koalitionsvertag zwischen CDU/CSU und SPD.

- Celis, Karen, and Liza M. Mügge. 2017. “Whose Equality? Measuring Group Representation.” Politics 38 (2): 197–213.

- Chaney, Paul. 2013. “Institutionally Homophobic? Political Parties and the Substantive Representation of LGBT People: Westminster and Regional UK Elections 1945-2011.” Policy and Politics 41 (1): 101–121.

- Cohen, Cathy J. 1999. “What is This Movement Doing to My Politics?” Social Text 61 (1999): 111–118.

- Crenshaw, Kimberley. 1997. “Intersectionality and Identity Politics: Learning from Violence Against Women of Color.” In Reconstructing Political Theory. Feminist Perspectives, edited by M. Lyndon Shanley, and U. Narayan, 178–193. Political Press: Cambridge.

- Davidson-Schmich, Louise K. 2017. “LGBT Politics in Germany: Unification as a Catalyst for Change.” German Politics 26 (4): 534–555.

- Davidson-Schmich, Louise K. 2018. “LGBTI Rights and the 2017 German National Election.” German Politics and Society 36 (2): 27–54.

- Die Linke. 2016. “Die sicherheitspolitische Zusammenarbeit mit der Türkei.” Drucksache 18/8057.

- Duggan, Lisa. 2002. “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism.” In Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics, edited by Russ Castronovo, and Dana D. Nelson, 175–194. Durham: Duke University Press.

- FDP. 2006. “Reform des Lebenspartnerschaftsgesetzes.” Drucksache 16/420.

- Haider-Markel, Donald P. 2010. Out and Running: Gay and Lesbian Candidates, Elections and Policy Representation. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Hancock, Ange Marie. 2007. “Intersectionality as a Normative and Empirical Paradigm.” Politics and Gender 3 (2): 248–254.

- Hansen, Eric R., and Sarah A. Treul. 2015. “The Symbolic and Substantive Representation of LGB Americans in the US House.” Journal of Politics 77 (4): 955–967.

- Helfer, Laurence R., and Erik Voeten. 2018. “International Courts as Agents of Legal Change: Evidence from LGBT Rights in Europe.” International Organization 68 (1): 77–110.

- Henninger, Annette, and Angelika von Wahl. 2014. “Grand Coalition and Multi-Party Competition: Explaining Slowing Reforms in Gender Policy in Germany (2009–13).” German Politics 23 (4): 386–399.

- Hill Collins, Patricia. 1998. “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia 13 (3): 62–82.

- Hunklinger, Michael, and Niklas Ferch. 2020. “Trans* Voting: Demand and Supply Side of Trans* Politics in Germany.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3 (3): 389–408.

- Joppke, Christian. 2007. “Transformation of Immigrant Integration: Civic Integration and Antidiscrimination in the Netherlands, France, and Germany.” World Politics 59: 243–273.

- Kollman, Kelly. 2013. The Same-Sex Unions Revolution in Western Democracies: International Norms and Domestic Policy Change. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kollman, Kelly. 2014. “Deploying Europe: The Creation of Discursive Imperatives for Same-Sex Unions.” In LGBT Activism and the Making of Europe, edited by Phillip M. Ayoub, and D. Paternotte, 97–118. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lemke, Christiane, and Helga A. Welsh. 2018. Germany Today: Politics and Policies in a Changing World. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Monro, Surya. 2005. Gender Politics: Citizenship, Activism and Sexual Diversity. London: Pluto Press.

- Murib, Zein. 2017. “Rethinking GLBT as a Political Category in US Politics.” In LGBTQ Politics: A Critical Reader, edited by Marla Brettschneider, Susan Burgess, and Christine Keating, 14–33. New York: NYU Press.

- Mushaben, Joyce Marie. 2016. “The Best of Times, the Worst of Times in: German Politics and Society Volume 34 Issue 1 (2016).” German Politics and Society 34 (118): 1–25.

- Mügge, Liza M., Daphne J. van der Pas, and Marc van de Wardt. 2019. “Representing Their Own? Ethnic Minority Women in the Dutch Parliament.” West European Politics 42 (4): 705–727.

- Och, Malliga. 2016. “The Adoption of Feminist Policies Under Conservative Governments.” PhD. thesis, University of Denver.

- Parent, Mike C., Cirleen DeBlaere, and Bonnie Moradi. 2013. “Approaches to Research on Intersectionality: Perspectives on Gender, LGBT, and Racial/Ethnic Identities.” Sex Roles 68 (11–12): 639–645.

- Paternotte, David. 2018. “Coming out of the Political Science Closet: The Study of LGBT Politics in Europe.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 1 (1–2): 55–74.

- Paternotte, David, and Kelly Kollman. 2013. “Regulating Intimate Relationships in the European Polity: Same-Sex Unions and Policy Convergence.” Social Politics 20 (4): 510–533.

- Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Puar, Jasbir. 2013. “Rethinking Homonationalism.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 45 (2): 336–339.

- Purdie-Vaughns, Valerie, and Richard P. Eibach. 2008. “Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-Group Identities.” Sex Roles 59 (5–6): 377–391.

- Rahman, Momin. 2019. “What Makes LGBT Sexualities Political? Understanding Oppression in Sociological, Historical, and Cultural Context.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics, edited by Michael Bosia, Sandra M. McEvoy, and Momin Rahman, 15–30. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, Andrew. 2013. “Representation and Rights: The Impact of LGBT Legislators in Comparative Perspective.” American Political Science Review 107 (2): 259–274.

- Saalfeld, Thomas. 2011. “Parliamentary Questions as Instruments of Substantive Representation: Visible Minorities in the UK House of Commons, 2005–10.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 17 (3): 271–289.

- Saalfeld, Thomas, and Daniel Bischof. 2013. “Minority-Ethnic MPs and the Substantive Representation of Minority Interests in the House of Commons, 2005–2011.” Parliamentary Affairs 66 (2): 305–328.

- Schotel, Anne Louise, and Liza M. Mügge. 2021. “Towards Categorical Visibility? The Political Making of a Third Sex in Germany and the Netherlands.” Journal of Common Market Studies (JCMS). 59 (4): 981–1024.

- Strolovitch, Dara Z. 2007. Affirmative Advocacy: Race, Class, and Gender in Interest Group Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Tremblay, Manon. 2019. “Outing Representation: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Queer Politicians’ Narratives.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 2 (2): 221–236.

- van der Vleuten, Anna. 2014. “Transnational LGBTI Activism and the European Courts: Constructing the Idea of Europe.” In LGBT Activism and the Making of Europe, edited by Phillip M. Ayoub, and D. Paternotte, 119–144. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Volkens, Andrea, Werner Krause, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Bernhard Weßels. 2019. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2019b. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).