ABSTRACT

This article introduces the special issue on smaller states and their relation to Germany in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). While there has been a mushrooming literature on the role of Germany in EMU, there has been hardly any research on how smaller states interact with EMU’s most powerful member. However, recent developments such as the rise of populism, Brexit, or the emergence of small state coalitions such as the ‘New Hanseatic League’ and the ‘Frugal Four’ give reason to take a closer look at the role of smaller states. Therefore, this special issue gathers the preferences of smaller EMU members, analyses the strategies they use to pursue them vis-à-vis Germany, and investigates the reasons for their choice as well as Germany’s reaction. At a theoretical level, we put forward an analytical framework providing causal propositions on why and how smaller states adopt certain strategies when they act in the shadow of hegemony. At an empirical level, we present the findings of the single contributions. We conclude by discussing the results in the light of our theoretical expectations.

Introduction

At least since the outbreak of the eurozone crisis, Germany has moved centre stage in the European Union (EU) (Paterson Citation2011). This applies in particular to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) (Bulmer Citation2014; Jacoby Citation2015; Schoeller Citation2019). While its central role has prompted many authors to write about Germany’s hegemony in the eurozone (Bulmer and Paterson Citation2019; Schild Citation2020; Webber Citation2019), there is hardly any research on how smaller eurozone states interact with EMU’s most powerful member. However, recent developments give reason to take a closer look at the role of smaller states.

On a global scale, the retreat of the United States under President Trump as a reliable partner for Europe has caused fears among smaller states. For example, the eurozone’s so-called creditor states fear that Germany could make concessions to France in EMU, given the need for cooperation in other policies such as defence, and the Baltics push for more integration to hedge against geopolitical risks emanating from Russia (Vilpišauskas Citationthis issue). At the European level, Brexit gives small liberal states reason to mobilise, as the exit of Great Britain means the loss of a powerful ally (Verdun Citationthis issue). At the national level, finally, the rise of populist parties and an increasing ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009) make it more difficult for smaller states to compromise at the European level and, in particular, to follow a Franco-German compromise (Jones Citationthis issue; Heidebrecht and Schoeller Citationthis issue). In view of these developments, it is hard to justify that we still lack in-depth knowledge about the preferences and strategiesFootnote1 of smaller states in interacting with the eurozone’s alleged hegemon.

These developments are reflected in unprecedented emancipation efforts of some smaller member states. Most notably, eight smaller countries built a coalition, labelled the ‘New Hanseatic League’, to promote their fiscally frugal views on EMU governance and reform. In doing so, they bypassed or even opposed Germany and its hegemonic position in the eurozone. For instance, the New Hansa rejected the Franco-German proposal of a genuine eurozone budget (Schoeller Citation2020b). In the context of fighting the economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis, another coalition, called the ‘Frugal Four’ (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden), opposed the spending plans proposed by the Franco-German tandem and the European Commission (Lofven Citation2020). The four smaller states rejected a Franco-Germany plan for a recovery fund and put forward their own proposal, which is based on loans rather than grants (Bayer, Smith-Meyer, and de La Baume Citation2020). When the final recovery package (‘Next Generation EU’) was negotiated as part of the EU budget negotiations, the Frugal Four, joined by Finland, took a hard bargaining stance and reached a reduction of grants for crisis-stricken member states (as compared to loans) and a considerable increase of EU budget rebates for themselves (Fleming, Khan, and Brunsden Citation2020). Most recently, a group of twelve smaller EU member states issued a position paper expressing a rather reserved stance on the ‘Conference on the Future of Europe’, which is in stark opposition to the originally great expectations put forward by France, for example (Khan and Hindley Citation2021; Non-Paper Citation2021).

Against this background, this special issue provides a comprehensive analysis of the relations between smaller EMU member states and Germany: It gathers the preferences of smaller states, analyses the strategies they use to pursue them vis-à-vis Germany, and investigates the reasons for their choice as well as Germany’s reaction. Hence, in this special issue we seek to answer the following questions: What are the preferences of smaller states in EMU governance and reform, and how do they relate to those of Germany? How do smaller states pursue their preferences in the shadow of German hegemony, i.e. what strategies do they use to influence or circumvent Germany? What explains their choice of strategies, and how is this choice conditioned by their relationship to Germany? Finally, how does Germany react?

Analysing the role of smaller states in the ‘shadow of hegemony’ invokes the controversial question of whether Germany can actually be considered a hegemon in EMU (see e.g. Matthijs Citation2020; Schild Citation2020). While we do not associate any normative content with the concept of hegemony, we acknowledge that Germany’s role in EMU goes beyond that of a merely powerful actor and thus differs considerably from its role in other EU policy fields. Relying on the below criteria derived from Hegemonic Stability Theory (e.g. Gilpin Citation1987; Kindleberger Citation1981; Snidal Citation1985), we therefore see an analytical value-added in applying the concept of hegemony to the relations between Germany and smaller states in EMU. However, we refrain from making any deterministic assertions on whether Germany acts as a ‘benign hegemon’ à la Kindleberger or rather as a ‘coercive hegemon’ as described by Robert Gilpin, for example. First of all, and opposed to other powerful actors, Germany is systemically relevant for EMU: without its most powerful member, the present monetary union is not conceivable in Europe. Second, Germany determined the ‘rules of the game’ in EMU, ranging from the early convergence criteria over the independence of the European Central Bank and the prohibition of monetary financing through to the Stability and Growth Pact (Dyson and Featherstone Citation1999; Schild Citation2020; Schoeller and Karlsson Citation2021). Third, a stable monetary union as upheld by Germany is a collective good, even if the way to achieve it is controversial (Caporaso forthcoming Citation2022). Fourth, as Germany benefits asymmetrically from this collective good (Jacoby Citation2015; Scharpf Citation2018), it is willing to maintain it by bearing a large part of the costs itself or by imposing them on other states.

With regard to its theoretical contribution, our special issue focuses on the conceptualisation and explanation of small state strategies in dealing with a hegemonic power (see below: ‘Theoretical Framework’). When it comes to theorising these strategies, Robert Keohane’s early call to study the ‘Lilliputians as carefully as the giant’ (Citation1969, 310) has largely been ignored (Long Citation2017, 157; Thorhallsson and Wivel Citation2006, 664). To be sure, there is an abundant literature on the (economic) adjustment strategies of small states in a globalised environment (Katzenstein Citation1985; Jones Citation2008; Baldersheim and Keating Citation2015). However, except for some notable exceptions (e.g. Panke Citation2010a), little has been written on the diplomatic strategies that small states may use to pursue their preferences in the context of regional (economic) integration (see below: ‘State of the Art’). Therefore, we put forward an explanatory framework providing causal propositions on why and how smaller states adopt certain roles when they act in the shadow of hegemony, such as ‘foot-dragging’ or ‘pace-setting’ (Börzel Citation2002),Footnote2 and what strategic tools they may use to realise them. Drawing on the ‘institutional fabric’ (Krotz and Schild Citation2013, 29–35) and the power asymmetry between smaller states and the hegemon, the framework also provides conjectures on whether smaller states confront or bypass the hegemon, and whether they rely on bargaining- or persuasion-based strategies in doing so. By applying the common framework, the individual contributions to the special issue not only examine the varying relations between smaller states and Germany, but also help us understand Germany’s reactions, that is, whether Germany acts as a leader, ally, mediator, or even opponent of smaller states.

Empirically, we contribute to the small states literature in International Relations and European integration (e.g. Archer, Bailes, and Wivel Citation2014; Cooper and Shaw Citation2009; Thorhallsson Citation2000). As Bohle and Jacoby (Citation2017) have pointed out, the success of small states depends not only on their domestic adjustment strategies, but also on external factors. We therefore introduce the role of Germany as a key factor in understanding the strategies of small states in EMU. Moreover, the questions of which strategies small EMU member states adopt vis-à-vis Germany and why they vary in time and across states have not been answered in the academic literature. Finally, by examining the strategies and relations of small states towards Germany, we link up with the burgeoning literature on Germany’s reluctance to take the lead in EMU governance and reform (Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013; Newman Citation2015; Schoeller Citation2018a). Based on carefully targeted empirical studies of small states and their relationship to Germany, our special issue thus addresses a blind spot in the analysis of Germany’s role in the EU.

Besides Germany, our universe of cases comprises all ‘small’ EMU member states that have adopted the euro. As regards the definition of ‘small’, we apply a pragmatic approach. Despite an abundant literature on the conceptualisation of ‘small states’, there is no satisfactory – let alone generally agreed – definition of ‘smallness’ in International Relations or European integration research (see e.g. Long Citation2017; Sutton Citation2011; Thorhallsson Citation2006; Verdun Citation2013). For heuristic reasons, we therefore use total GDP as an adequate indicator of size in the context of EMU politics, defining ‘small states’ as those with a GDP below the eurozone average (see ). In addition, given their recent role as a leader of smaller eurozone states (see Verdun Citationthis issue), we include the Netherlands in this selection, even though their GDP is somewhat above the eurozone average.

Table 1. Eurozone countries’ GDP at market prices 2019 (in million euro). Source: Eurostat (own compilation).

Within this universe of cases, our contributors offer theory-guided analyses of seven smaller eurozone countries and their relations to Germany (Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Greece, the Netherlands). The seven smaller states represent different positions on the cleavages between ‘creditor’ vs. ‘debtor states’ and old vs. new member states. This case selection helps us identify generalisable patterns that do not depend on the idiosyncrasies of single countries. Moreover, our selection reflects the fact that there are more small creditor states than small debtor states in the eurozone. It thus allows us to draw general conclusion that apply to the entire universe of cases. An additional contribution to the special issue analyses how the newly founded ‘Hanseatic League’ affects the alleged hegemony of Germany, and how the German government is torn between them and France (Howarth and Schild Citationthis issue). The final contribution unites the various themes of the special issue – Franco-German leadership, hegemony, and the role of small states – by arguing that smaller states find it increasingly hard to follow Germany or the Franco-German tandem as their political leaders are increasingly constrained by domestic political developments (Jones Citationthis issue) (for brief summaries, see below: ‘Contributions’). Regarding data collection, the contributions draw on a broad range of untapped sources, such as elite interviews, policy documents, public speeches and declarations, voting patterns and public opinion polling.

State of the Art and Gap in the Literature

There is a distinct strand of literature dealing with the role of small states in international relations (see Archer, Bailes, and Wivel Citation2014; Chong and Maass Citation2010; Cooper and Shaw Citation2009; Ingebritsen et al. Citation2006). The origins of this literature date back to the 1960s, when mostly US-American scholars discovered that alliances with the United States increased the influence of small states on American foreign policy (see Keohane Citation1969, Citation1971). Paradoxically, small states were thus found to exercise substantial influence over great powers through alliances and multilateral institutions (Lindell and Persson Citation1986). A second strand of literature has focused on the role of small states in international political economy and the adjustment strategies they use to adapt to a competitive environment (see Bishop Citation2012; Jones Citation2008; Verdun Citation2013). The arguably most seminal work in this strand of literature is Katzenstein’s (Citation1985) study of small states in world markets (see also Katzenstein Citation2003).

For a long time of European integration research little attention was paid to the role of small states (for an exception, see Jones Citation1993). However, since the EU’s 1995 enlargement, political scientists have increasingly turned to the role played by small states in Europe (Archer and Nugent Citation2002; Goetschel Citation1998; Jakobsen Citation2009; Nasra Citation2011; Thorhallsson and Wivel Citation2006). In so doing, they also focused on policies outside the realm of foreign and security issues (Arter Citation2000; Lee Citation2004; Panke Citation2010a; Thorhallsson Citation2000). On the one hand, this literature has highlighted the structural disadvantages of small states in the EU: ‘Small states have fewer votes, undersized staff and fewer financial means’ (Panke Citation2010b, 801). Moreover, the size and openness of their economies provide little bargaining leverage when it comes to issues of Single Market or economic governance in the EU. On the other hand, scholars revealed alternative sources of power that are typical of small states.

First, small administrations allow for more informality, flexibility, and autonomy in EU decision-making (Baillie Citation1998, 200; Thorhallsson Citation2015, 2–3). Second, relative gains of small states are less threatening to their larger partners, whereas losses or concessions are deemed less acceptable (Baillie Citation1998, 202–4). Third, small states may profit from their typical role as a broker between larger member states in EU negotiations (Maes and Verdun Citation2005, 343; Thürer Citation1998, 39). Finally, a crucial but often neglected way of compensating for structural disadvantages is the use of particular agenda-setting and decision-making strategies (Björkdahl Citation2008; Grøn and Wivel Citation2011; Schure and Verdun Citation2008).

However, the political or diplomatic strategies of small states in EMU – let alone their relation to Germany – have been analysed by very few scholars. Maes and Verdun (Citation2005) analysed the roles of Belgium and the Netherlands in the creation of EMU, concluding that they played a significant role as pace-setter and gate-keeper, respectively. The few other works dealing with the role small states in EMU (Chang Citation2006; Jones, Frieden, and Torres Citation1998) do not focus on these states’ political strategies or their relation to Germany.

Theoretical Framework

In analysing the preferences and strategies of smaller states acting in the shadow of hegemony, we adopt a parsimonious theoretical framework. We conjecture that a small state’s choice of strategy is determined by its preferences in relation to the status quo, the power asymmetry in the relationship to the hegemon, and the ‘institutional fabric’ (regularised intergovernmentalism, symbolic acts and practices, and ‘parapublic’Footnote3 underpinnings; see below) of this relationship. In favour of theoretical parsimony we keep our conjectures as general and – at the same time – as limited as possible, but we do not rule out that additional factors may crucially affect the strategies of small states in dealing with a hegemon. This regards in particular the role of domestic factors, which are often idiosyncratic and therefore hard to theorise (see e.g. Waltz Citation1979). We thus leave room for our empirical contributions to collect inductive insights that go beyond our ex ante propositions.

We define preferences as an actor’s evaluative rank order of outcomes possible in a given environment. A strategy, by contrast, is an actor’s attempt to come as close as possible to its most preferred outcome. In the words of Jeffry Frieden:

‘States, groups, or individuals require ways to obtain goals, paths to their preferences. These paths must take into account the environment – other actors and their expected behaviour, available information, power disparities. Given this strategic setting, strategies are tools the agent uses to get as close to its preferences as possible’ (Citation1999, 45).

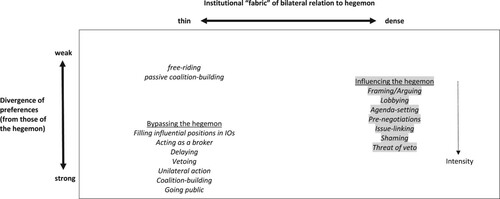

Table 2. Small state strategies vis-à-vis hegemon (strategies in italics, bilateral interaction with hegemon shaded in grey) Reference: own compilation.

Hence, we understand a strategy as a behaviour that helps small states achieve an interaction result as close as possible to their most preferred outcome. This corresponds to the understanding of strategies as applied in the works of Panke (Citation2010a) or Grøn and Wivel (Citation2011), for example. However, our definition differs from what the political economy literature refers to as an ‘adjustment strategy’, which is a small state’s way of adapting its political institutions and public policies to problems of international competitiveness (e.g. Bohle and Jacoby Citation2017; Jones Citation2008; Katzenstein Citation1985).

In the context of Europeanization research, Börzel (Citation2002) has proposed a useful distinction between three types of member state behaviour (or roles), namely ‘foot-dragging’, ‘fence-sitting’ and ‘pace-setting’. We build on this typology to categorise the multitude of strategic tools that we find in the literature and previous empirical research (e.g. Panke Citation2010a; Ingebritsen et al. Citation2006). Accordingly, our conceptualisation starts with the proposition that the choice of a certain strategy depends on the distance between a state’s preferences and the status quo (SQ), ranging from ‘foot-dragging’ (smallest distance) via ‘fence-sitting’ and ‘co-shaping’ through to ‘pace-setting’ (largest distance) (see ).

If states prefer the status quo to any policy or institutional change on the table, they will use a veto or at least threaten to do so, build counter-coalitions and blocking minorities, or try to delay the decision-making process in other ways (e.g. through rhetorical action). Although such ‘foot-dragging’ manoeuvres may not suffice to prevent a policy or institutional change altogether, they can bring about concessions (package deals), compensation (side-payments), or derogations (opt-out clauses) (Börzel Citation2002, 205).

If smaller states fear that any such action may be more costly than the expected outcome (be it status quo or change), we expect them to opt for ‘fence-sitting’. In this case, they adopt a passive position and may even swap coalitions (Börzel Citation2002, 206). If, by contrast, they conclude that an active participation in the decision-making process pays off, they will use ‘shaping strategies’ (Panke Citation2010a, 20–9) to influence the outcomes in the desired way (‘co-shaping’). These strategies range from bargaining tactics such as issue-linking or pre-negotiations to persuasion-based activities such as framing and shaming (see ). Once a group of states has decided to actively engage in the decision-making process, the question arises who will move first and ‘set the pace’ for the others to follow. We argue that those who suffer the highest status quo costs move first as they would profit most from change.

As illustrated by , the choice of a certain strategy (foot-dragging, fence-sitting, co-shaping, pace-setting) implies a given set of strategic tools available to a small state. However, this does not tell us whether the state relies on bargaining or rather opts for persuasion-based activities in pursuing its preferences vis-a-vis the hegemon (Panke Citation2010a, 20–9). We argue that this choice depends on the asymmetry of power between the small state and the hegemon. Defining power by a state’s ‘fall-back position’ (i.e. its best alternative to negotiated agreement), we assume states with a good fall-back position to expect more success from employing a bargaining-based strategy. Less powerful states, by contrast, anticipate the futility of bargaining against a hegemon and therefore tend to rely on persuasion-based strategies. Hence, our second proposition states: The larger the asymmetry in power between a smaller state and the hegemon, the more likely the smaller state will rely on persuasion rather than hard bargaining.

Our third and last proposition concerns the question of whether a state interacts directly with the hegemon or seeks to bypass it through multilateral action (e.g. in international organisations or counter-coalitions). We argue that this depends on the ‘institutional fabric’ of the relation between the small state and the hegemonic power. According to Krotz and Schild, the institutional fabric consists of ‘regularised intergovernmentalism’ (i.e. patterns of interaction and communication between individual representatives of their states), symbolic acts and practices, and ‘parapublic underpinnings’ such as cultural exchange programmes or transnational partnerships (Citation2013, 29–35). We therefore expect states with a ‘dense’ institutional fabric in their relationship to the hegemon to channel their preferences directly through the hegemon, whereas others choose to bypass the hegemonic power. However, they will bypass the hegemon only if they regard this as truly worthwhile. In other words, the divergence between a small state’s preferences and those of the hegemon also plays a role: in case of a thin institutional fabric, we expect states to oppose a hegemon only if they have strongly diverging preferences. If, by contrast, their preferences diverge only slightly, these states will not make the effort of bypassing the hegemon, but rather adopt a ‘free-rider strategy’ by accepting the anticipated outcomes and saving transaction or bargaining cost (see ).

While the divergence of preferences from the status quo and the power asymmetry between small states and the hegemon are variables that are well embedded in the rationalist research tradition, the institutional fabric of bilateral relationships relates to a rather constructivist reasoning. However, as it is not our aim to test a theory, but to provide a sufficient explanation of empirical outcomes, we consider it appropriate to combine these variables in a coherent theoretical model. In other words, by engaging in ‘eclectic theorising’, we ‘engage adherents of different traditions in meaningful conversations about substantive problems in international life’ (Katzenstein and Sil Citation2008, 111).

and summarise our conceptualisation of possible strategies and relate them to our theoretical propositions. Those strategic tools that can (also) be used in direct interaction with the hegemon are shaded in grey.

Contributions and Findings

In the first empirical contribution to this special issue, Michele Chang examines the role of Belgium, which traditionally acted as a bridge between Germany and France. By comparing Belgium’s preferences and strategies before and after the outbreak of the global financial crisis and relating them to those of Germany, Chang finds that Belgium evolved from a co-shaper and pace-setter into a fence-sitter in EMU politics. While the EU founding member formerly relied on persuasion-based strategies, cultivated alliances and brokered compromises, the financial crisis and domestic turmoil constrained its room for manoeuvre. The findings largely confirm our propositions. Given the large power asymmetry in the relationship to Germany, Belgium relied on persuasion-based strategies rather than hard bargaining. Moreover, as the institutional fabric of the bilateral relationship is weak compared to that of other member states, Belgium preferred multilateral settings over direct interaction with Germany. For the post crisis period, however, our theoretical expectations could be assessed only to a limited extent since Belgium was largely absent from the debate.

In the special issue’s second contribution, Sebastian Heidebrecht and Magnus Schoeller focus on Austria’s role in EMU governance and its relationship to Germany. They argue that despite strong political, cultural and economic ties between the two countries, Austria has assumed an increasingly independent role. Based on the analysis of three different periods of EMU reform since the outbreak of the eurozone crisis, the authors investigate how and why the close partnership of the two countries is slowly growing apart. They find that converging economic preferences and the strong power asymmetry of the bilateral relationship can explain Austria’s cooperative strategy until 2016. By contrast, Austria’s shift from loyal followership towards more pronounced independence is largely caused by domestic developments, notably a rise of populism and a particularly assertive head of government responding also to the Eurosceptic parts of the electorate.

Shifting the focus to the Baltic States – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – Ramūnas Vilpišauskas sets out to examine three small states whose role in EMU governance is largely underexplored. The author shows that the three Baltic states not only consider the economic dimension of EMU. As a project that further deepens European integration, EMU also implies a geopolitical dimension for the Baltics: by being part of the EU’s core, they also seek to hedge against external security risks stemming from Russia. Although their economic preferences differ to some extent from those of Germany, with the Baltics being more sceptical about fiscal integration but more integrationist in financial governance, their geopolitical interests are paramount. Hence, after they had succeeded in joining the eurozone, the Baltic States adopted the role of cautious ‘fence sitters’.

Georgios Maris and Panagiota Manoli scrutinise Greece’s strategies in EMU governance and reform as well as the difficult relationship between Greece and Germany. Standing on the brink of economic collapse and eurozone exit, Greece had an extremely bad fall-back position in pursuing its preferences during and after the eurozone crisis. By putting the asymmetric power relation between chief creditor (Germany) and main debtor (Greece) at the centre of their analysis, the authors plausibly explain why Greece adopted ‘only’ a fence-sitter position in EMU politics. However, Greece’s short-lived repositioning during the negotiations of the third bailout in 2015 and its failed attempts of hard bargaining cannot be explained by changes in the power relations, but rather by relying on an incremental decision-making model in which decisions are taken based on unclear and changing government preferences. Like other contributions to this special issue, the analysis of Maris and Manoli therefore shows that domestic politics can be indispensable to sufficiently explain specific small state strategies in the context of EMU politics, even if they are often idiosyncratic and therefore hard to theorise.

In her analysis of the Netherlands and the New Hanseatic League, Amy Verdun shifts the focus on the other side of the continuum in terms of member state preferences, as the Dutch are seen by many observers as the most hawkish state in EMU governance and reform. In addition to their special role in terms of preferences, the Netherlands are an extremely important case because, as the author points out, they can be seen as ‘the greatest of the small’ eurozone members. Verdun finds that Dutch preferences are close to the status quo in EMU, which often results in a pronounced foot-dragging role. In order to pursue their preferences, the Dutch have built or joint counter-coalitions such as the New Hanseatic League or the Frugal Four. Although the Netherlands maintain a good rapport with Germany, the smaller asymmetry in power (compared to other member states) makes the use of bargaining-based strategies more rewarding. Based on a relatively dense institutional fabric of the bilateral relationship, the Dutch also engaged in intense bilateral contacts with Germany. Hence, Verdun’s case study finds confirming evidence for all three of our theoretical conjectures.

Putting Germany at the centre of their analysis, David Howarth and Joachim Schild trace how EMU’s most powerful state is torn between France and the New Hanseatic League countries. They argue that economic preferences can partly explain the extent of concessions made by Germany to both the New Hansa countries and France. However, in order to explain the choice of German governments on how and with whom best to pursue their preferences, the authors also consider existing norms of cooperation and geostrategic interests. As a result, they find that German governments have performed a balancing act between the New Hansa and France, which is skewed towards the latter. Moreover, the authors argue that the presence of economic crises increases the degree to which this balancing act is skewed towards France.

In the final contribution to this special issue, Erik Jones unites its various themes: Franco-German leadership, reluctant hegemony, and the role of small states. In doing so, Jones bridges the gap between the Political Economy literature on the adjustment strategies of small states and the International Relations literature on their diplomatic strategies. Jones argues that small states find it increasingly hard to follow Franco-German leadership in EMU. While political fragility, based on a breakdown of internal compensation mechanisms and increasing domestic conflict, results in an inability to follow, strongly held views in the domestic arena lead to an unwillingness to compromise at the European level. Both developments are reflected in the Eurosceptic populist movements that are also highlighted by some of the other contributions to this special issue. As Jones points out, these EU-wide domestic tendencies are likely to result in foot-dragging strategies vis-à-vis Germany (and France) despite striking asymmetries in political power and economic interdependency. Taking the example of the Netherlands, he concludes that a small country government can resist any proposal (‘foot-dragging’), but it can hardly persuade larger member states that are not experiencing the same combination of social forces (‘co-shaping’ or ‘pace-setting’).

In summary, the empirical analyses of this special issue corroborate our theoretically informed expectations that the preferences of small states and the asymmetry of power vis-à-vis Germany determine their choice of strategy and thus the relationship to the eurozone’s hegemon. In addition, the articles reveal important insights leading beyond our parsimonious framework. First, the material preferences related to EMU do not reflect a cleavage between large and small member states, but rather a creditor–debtor divide, with export-oriented ‘creditor states’ in the north preferring national adjustment (‘austerity’) and less competitive ‘debtor states’ in the south promoting fiscal redistribution (‘solidarity’). While this confirms previous research (e.g. Armingeon and Cranmer Citation2018; Frieden and Walter Citation2017; Lehner and Wasserfallen Citation2019), we found that the preferences of smaller eurozone states are more heterogeneous than meets the eye. Even the supposedly homogeneous camp of ‘creditor states’, formerly led by Germany, is split on crucial EMU issues such as a genuine eurozone budget, EDIS, or the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposure in the context of Banking Union (also Howarth and Quaglia Citation2018; Schoeller Citation2020a). This heterogeneity has even led to new coalitions of fiscally conservative states without Germany, such as the New Hanseatic League or the Frugal Four.

Second, despite this divergence of preferences, we observe much fence-sitting and increasing instances of foot-dragging, but only very little co-shaping or pace-setting attempts. To be sure, until the negotiations of a COVID-19 recovery package in 2020Footnote4, and with the exception of the Netherlands, no smaller member state had opposed EMU initiatives by deploying hard bargaining strategies such as the use or threat of a veto. Smaller states may find it increasingly hard to follow, but they also know that they need other member states in future decisions or different policies. They therefore have long time accepted second-best outcomes rather than blocking a decision. At the same time, however, the stance of smaller states appears to be hardening, as recent small state coalitions opposing Franco-German initiatives have shown. The contributors of this special issue have investigated the New Hanseatic League as one of these small state coalitions. Still, it is still not clear whether the New Hansa actually supports Germany (Verdun Citationthis issue) or rather keeps it from making important compromises with France (Jones Citationthis issue). Moreover, pointing to some weaknesses and countervailing dynamics, Verdun is rather sceptical about the continued existence of the coalition.

Third, our empirical findings reveal that the institutional fabric of the relationship between smaller states and the hegemon has less influence on the choice of strategies than expected. Contrary to the Franco-German relationship (Howarth and Schild Citationthis issue), in the case of smaller states economic preferences seem to prevail over the institutional fabric if the two are at odds.

Fourth, several contributions have emphasised the importance of domestic factors in explaining small state strategies in EMU governance (CitationChang; CitationHeidebrecht and Schoeller; CitationMaris and Manoli; Jones Citationthis issue). From a theoretical perspective, the consideration of domestic idiosyncrasies is problematic as they hardly allow us to generalise. However, our contributions have pointed to some generalisable developments, most importantly the rise of populism and an increasing constraining dissensus regarding further integration. Hence, the ‘domestic variable’ constitutes a relevant avenue for future research on smaller states in EU or international economic governance and should therefore not be omitted.

Finally, this special issue focuses on the strategies that small eurozone states use to pursue their preferences in the shadow of German hegemony. Their actual influence, by contrast, has partially been assessed elsewhere (Lundgren et al. Citation2019) and remains an important task for future research. Still, based on the contributions to this issue, we can draw some tentative conclusions on the power and influence of small states in EMU. While our authors find that their influence roughly corresponds to their size, as they lack material, institutional and bureaucratic resources compared to their larger peers, small states can punch over their weight by using certain strategies (see above; Panke Citation2010a; Schoeller Citation2020b).

The most effective strategic tool to exert influence is to build coalitions (Verdun Citationthis issue) if they are credible and consistent in presenting their positions. Although small states also have veto power in many EMU-related decisions, they tend not to use it (Vilpišauskas Citationthis issue). The reason may be that they lack the ‘go-it-alone power’ of their larger peers. At the same time, we observe a growing number of instances, where states like the Netherlands or Austria at least threaten to use a veto, which may point to the fact that smaller states find it increasingly hard to follow the Franco-German tandem (Jones, this issue). The salient impact of smaller states in negotiating the Recovery and Resilience Facility, for example, can thus be read in two ways: On the one hand, the ‘Frugal Four’ plus Finland succeeded in decreasing the amount of grants from 500bn, as proposed by Germany and France, to 390bn. On the other hand, the ‘frugals’ failed to prevent debt-financed grants from entering the EU agenda in the first place (Howarth and Schild Citationthis issue). This episode also shows how problematic it is to estimate influence by mere preference attainment. Moreover, our case studies indicate that attaining preferences through free-riding – if not on the negotiation efforts of France or Germany, then on those of the Netherlands – rather than exerting own influence seems to remain characteristic of smaller states in EMU (see Chang Citationthis issue).

With regard to the role of Germany, we saw that it considers the relationship with France as way more important than that with smaller eurozone states. Neither has Germany acted as a mediator vis-à-vis smaller states, nor has it been a real ally. Even where economic preferences largely converge, as in the case of the New Hanseatic League, Germany has been cautious not to impair the relationship with France by openly siding with smaller member states. On the contrary, the German strategy has always been to seek a bilateral and often difficult compromise with France before consulting its smaller partners (Dyson Citation1999; Krotz and Schild Citation2013; Webber Citation1999). While there are good reasons for applying this strategy also to EMU governance and reform (see Schild Citation2013; Schoeller Citation2018b), the increasing emancipation of smaller states shown by this special issue suggests the need for a more explicit consideration of their preferences. This does not mean that Germany and France should forego the tried and tested practice of striking bilateral deals to further European integration. Rather, they should consult smaller states early on and, once an agreement has been found, make explicit how they have included their preferences. This might make it easier for smaller states to compromise at the European level despite a constraining dissensus at home.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Magnus G. Schoeller

Magnus G. Schoeller is Principal Investigator and APART-GSK Fellow of the Austrian Academy of Sciences at the Centre for European Integration Research (EIF), Department of Political Science, University of Vienna. His research on the governance of the Economic and Monetary Union, Germany's role in the EU, and political leadership appeared with Palgrave Macmillan and journals such as the European Political Science Review, the Journal of European Public Policy, or the Journal of Common Market Studies.

Gerda Falkner

Gerda Falkner directs the Centre for European Integration Research in the Department of Political Science, University of Vienna, Austria. Her publications focus on various EU policies and their implementation, with publishers such as Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, Routledge, and the leading international journals in the field. Most recently, she set up a team researching the EU's role in the digital revolution and how to protect democracy.

Notes

1 While we define ‘preferences’ as actors’ evaluative rank orders of possible outcomes in a given environment, we understand ‘strategies’ as ways to get as close as possible to the preferred outcome (for a more elaborated definition, see below: ‘Theoretical Framework’).

2 In defining the different roles we build on a typology proposed by Börzel (Citation2002), but enhance it by adding a causal explanatory framework, specifying the respective strategic tools, and contributing the category of ‘co-shaping’ (see below: ‘Theoretical Framework’).

3 ‘Parapublic underpinnings of international relations are cross-border interactions that belong neither to the public world of states nor to the private realm of societies’ (Krotz and Schild Citation2013, 32). Although these activities are usually state-financed or -organized, the participants do not act as official state representatives. Parapublic relations include, for example, school exchange or municipal partnerships.

4 At the negotiations of a COVID-19 recovery package (‘Next Generation EU’), the ‘Frugal Four’ (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden), later joined by Finland, took a hard bargaining stance and thus reached a reduction of grants for crisis-stricken member states and an increase of EU budget rebates for themselves.

References

- Archer, Clive, Alyson J.K. Bailes, and Anders Wivel. 2014. Small States and International Security: Europe and Beyond. London/New York: Routledge.

- Archer, Clive, and Neill Nugent. 2002. “Introduction: Small States and the European Union.” Current Politics and Economics of Europe 11 (1): 1–10.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Skyler Cranmer. 2018. “Position-taking in the Euro Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (4): 546–566.

- Arter, David. 2000. “Small State Influence Within the EU: The Case of Finland’s ‘Northern Dimension Initiative’.” Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (5): 677–697.

- Baillie, Sasha. 1998. “The Position of Small States in the EU.” In Small States Inside and Outside the European Union: Interests and Policies, edited by Laurent Goetschel, 193–205. Boston,MA/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Baldersheim, Harald, and Michael Keating. 2015. Small States in the Modern World: Vulnerabilities and Opportunities. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bayer, Lili, Bjarke Smith-Meyer, and Maïa de La Baume. 2020. “Franco-German recovery deal meets resistance.” Politico, 19 May. https://www.politico.eu/article/franco-german-recovery-deal-meets-resistance/.

- Bishop, Matthew Louis. 2012. “The Political Economy of Small States: Enduring Vulnerability?” Review of International Political Economy 19 (5): 942–960.

- Björkdahl, Annika. 2008. “Norm Advocacy: a Small State Strategy to Influence the EU.” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (1): 135–154.

- Bohle, Dorothee, and Wade Jacoby. 2017. “Lean, Special, or Consensual? Vulnerability and External Buffering in the Small States of East-Central Europe.” Comparative Politics 49 (2): 191–212.

- Börzel, Tanja A. 2002. “Pace-Setting, Foot-Dragging, and Fence-Sitting: Member State Responses to Europeanization.” Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (2): 193–214.

- Bulmer, Simon. 2014. “Germany and the Eurozone Crisis: Between Hegemony and Domestic Politics.” West European Politics 37 (6): 1244–1263.

- Bulmer, Simon, and William E. Paterson. 2013. “Germany as the EU’s Reluctant Hegemon? Of Economic Strength and Political Constraints.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (10): 1387–1405.

- Bulmer, Simon, and William E. Paterson. 2019. Germany and the European Union: Europe's Reluctant Hegemon? London: Palgrave Macmillan / Red Globe Press.

- Caporaso, James A. forthcoming 2022. “Germany and the Eurozone Crisis: Power, Dominance, and Hegemony.” In Power Relations and Regionalism: Europe, Asia, and Latin America in Comparative Perspective, edited by Min-hyung Kim, and James A. Caporaso. London/New York: Routledge.

- Chang, Michele. 2006. “Reforming the Stability and Growth Pact: Size and Influence in EMU Policymaking.” Journal of European Integration 28 (1): 107–120.

- Chang, Michele. This issue. “The Art of Compromise: Belgium as the Bridge Between Germany and France.” German Politics. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2002847

- Chong, Alan, and Matthias Maass. 2010. “Introduction: the Foreign Policy Power of Small States.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 23 (3): 381–382.

- Cooper, Andrew F., and Timothy M. Shaw. 2009. The Diplomacies of Small States: Between Vulnerability and Resilience. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dyson, Kenneth. 1999. “The Franco-German Relationship and Economic and Monetary Union: Using Europe to ‘Bind Leviathan’.” West European Politics 22 (1): 25–44.

- Dyson, Kenneth, and Kevin Featherstone. 1999. The Road to Maastricht. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fleming, Sam, Mehreen Khan, and Jim Brunsden. 2020. “EU leaders strike deal on €750bn recovery fund after marathon summit.” Financial Times, 21 July. https://www.ft.com/content/713be467-ed19-4663-95ff-66f775af55cc.

- Frieden, Jeffry. 1999. “Actors and Preferences in International Relations.” In Strategic Choice and International Relations, edited by David A Lake, and Robert Powell, 39–72. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Frieden, Jeffry, and Stefanie Walter. 2017. “Understanding the Political Economy of the Eurozone Crisis.” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1): 371–390.

- Gilpin, Robert. 1987. The Political Economy of International Relations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Goetschel, Laurent. 1998. Small States Inside and Outside the European Union: Interests and Policies. Boston,MA/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Grøn, Caroline H., and Anders Wivel. 2011. “Maximizing Influence in the European Union After the Lisbon Treaty: From Small State Policy to Smart State Strategy.” Journal of European Integration 33 (5): 523–539.

- Heidebrecht, Sebastian, and Magnus G. Schoeller. This issue. “The Austrian-German Relationship in EMU Reform: From Asymmetric Partnership to Increased Independence.” German Politics. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2005029

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23.

- Howarth, David, and Lucia Quaglia. 2018. “The Difficult Construction of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme: a Step Too far in Banking Union?” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (3): 190–209.

- Howarth, David, and Joachim Schild. This issue. “Torn Between Two Lovers: German Policy on Economic and Monetary Union, the New Hanseatic League and Franco-German Bilateralism.” German Politics.

- Ingebritsen, Chrisitine, Iver Neumann, Sieglinde Gstöhl, and Jessica Beyer. 2006. Small States in International Relations. Seattle/Reykjavik: University of Washington Press/University of Iceland Press.

- Jacoby, Wade. 2015. “Europe’s New German Problem: The Timing of Politics and the Politics of Timing.” In The Future of the Euro, edited by Matthias Matthijs, and Mark Blyth, 187–209. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jakobsen, Peter Viggo. 2009. “Small States, Big Influence: The Overlooked Nordic Influence on the Civilian ESDP.” Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (1): 81–102.

- Jones, Erik. 1993. “Small Countries and the Franco-German Relationship.” In France-Germany, 1983-1993: The Struggle to Cooperate, edited by Patrick McCarthy, 113–138. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Jones, Erik. 2008. Economic Adjustment and Political Transformation in Small States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Erik, Jeffry Frieden, and Francisco Torres. 1998. Joining Europe's Monetary Club: The Challenges for Smaller Member States. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Jones, Erik. This issue. “Hard to Follow: Small States and the Franco-German Relationship.” German Politics.

- Katzenstein, Peter J. 1985. Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Katzenstein, Peter J. 2003. “Small States and Small States Revisited.” New Political Economy 8 (1): 9–30.

- Katzenstein, Peter J., and Rudra Sil. 2008. “Eclectic Theorizing in the Study and Practice of International Relations.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, edited by Christian Reus-Smit, and Duncan Snidal, 109–130. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Keohane, Robert O. 1969. “Lilliputians’ Dilemmas: Small States in International Politics.” International Organization 23 (2): 291–310.

- Keohane, Robert O. 1971. “The Big Influence of Small Allies.” Foreign Policy 1 (2): 161–182.

- Khan, Mehreen, and David Hindley. 2021. “EU’s dirty dozen pour cold water on Conference on Future of Europe.” Financial Times, 23 March. https://www.ft.com/content/d1dc2d24-c82f-400d-b447-0302a7ee06d4.

- Kindleberger, Charles P. 1981. “Dominance and Leadership in the International Economy: Exploitation, Public Goods, and Free Rides.” International Studies Quarterly 25 (2): 242–254.

- Krotz, Ulrich, and Joachim Schild. 2013. Shaping Europe: France, Germany, and Embedded Bilateralism from the Élysée Treaty to Twenty-First Century Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, Moo Sung. 2004. “The European Union Beyond 2004: Small States and Trade Policy.” International Area Review 7 (1): 19–35.

- Lehner, Thomas, and Fabio Wasserfallen. 2019. “Political Conflict in the Reform of the Eurozone.” European Union Politics 20 (1): 45–64.

- Lindell, Ulf, and Stefan Persson. 1986. “The Paradox of Weak State Power: A Research and Literature Overview.” Cooperation and Conflict 21 (2): 79–97.

- Lofven, Stefan. 2020. “‘Frugal four’ warn pandemic spending must be responsible.” Financial Times, 16 June. https://www.ft.com/content/7c47fa9d-6d54-4bde-a1da-2c407a52e471?emailId=5ee9a70ddfb6ef0004d5eeed&segmentId=488e9a50-190e-700c-cc1c-6a339da99cab.

- Long, Tom. 2017. “It’s not the Size, It’s the Relationship: From ‘Small States’ to Asymmetry.” International Politics 54 (2): 144–160.

- Lundgren, Magnus, Stefanie Bailer, Lisa M. Dellmuth, Jonas Tallberg, and Silvana Târlea. 2019. “Bargaining Success in the Reform of the Eurozone.” European Union Politics 20 (1): 65–88.

- Maes, Ivo, and Amy Verdun. 2005. “Small States and the Creation of EMU: Belgium and the Netherlands, Pace-Setters and Gate-Keepers.” Journal of Common Market Studies 43 (2): 327–348.

- Maris, Georgios, and Panagiota Manoli. This issue. “Greece, Germany and the Eurozone Crisis: Preferences, Strategies and Power Asymmetry.” German Politics.

- Matthijs, Matthias. 2020. “Hegemonic Leadership is What States Make of it: Reading Kindleberger in Washington and Berlin.” Review of International Political Economy (Online First, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1813789.

- Nasra, Skander. 2011. “Governance in EU Foreign Policy: Exploring Small State Influence.” Journal of European Public Policy 18 (2): 164–180.

- Newman, Abraham. 2015. “The Reluctant Leader: Germanýs Euro Experience and the Long Shadow of Reunification.” In The Future of the Euro, edited by Matthias Matthijs, and Mark Blyth, 117–135. Oxford/New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Non-Paper. 2021. “Conference on the Future of Europe: Common Approach Amongst Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Sweden.

- Panke, Diana. 2010a. Small States in the European Union: Coping with Structural Disadvantages. London/New York: Routledge.

- Panke, Diana. 2010b. “Small States in the European Union: Structural Disadvantages in EU Policy-Making and Counter-Strategies.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (6): 799–817.

- Paterson, William E. 2011. “The Reluctant Hegemon? Germany Moves Centre Stage in the European Union.” Journal of Common Market Studies 49 (S1): 57–75.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 2018. International Monetary Regimes and the German Model. MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/1. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Schild, Joachim. 2013. “Leadership in Hard Times: Germany, France, and the Management of the Eurozone Crisis.” German Politics and Society 31 (1): 24–47.

- Schild, Joachim. 2020. “The Myth of German Hegemony in the Euro Area Revisited.” West European Politics 43 (5): 1072–1094.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2018a. “Germany, the Problem of Leadership, and Institution-Building in EMU Reform.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform:Online First, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2018.1541410.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2018b. “The Rise and Fall of Merkozy: Franco-German Bilateralism as a Negotiation Strategy in Eurozone Crisis Management.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (5): 1019–1035.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2019. Leadership in the Eurozone: The Role of Germany and EU Institutions. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2020a. “Free Riders, Allies or Veto Players? Preferences and Strategies of Smaller Creditor States in the Euro Area.” EIF Working Paper No. 2/2020. Vienna: Centre for European Integration Research (EIF). https://eif.univie.ac.at/workingpapers/index.php.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2020b. “Preventing the Eurozone Budget: Issue Replacement and Small State Influence in EMU.” Journal of European Public Policy (Online First), doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1795226.

- Schoeller, Magnus G., and Olof Karlsson. 2021. “Championing the ‘German Model’? Germany’s Consistent Preferences on the Integration of Fiscal Constraints.” Journal of European Integration 43 (2): 193–209.

- Schure, Paul, and Amy Verdun. 2008. “Legislative Bargaining in the European Union: The Divide Between Large and Small Member States.” European Union Politics 9 (4): 459–486.

- Snidal, Duncan. 1985. “The Limits of Hegemonic Stability Theory.” International Organization 39 (4): 579–614.

- Sutton, Paul. 2011. “The Concept of Small States in the International Political Economy.” The Round Table 100 (413): 141–153.

- Thorhallsson, Baldur. 2000. The Role of Small States in the European Union. Aldershot/Burlington,VT: Ashgate.

- Thorhallsson, Baldur. 2006. “The Size of States in the European Union: Theoretical and Conceptual Perspectives.” Journal of European Integration 28 (1): 7–31.

- Thorhallsson, Baldur. 2015. “How Do Little Frogs Fly? Small States in the European Union. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

- Thorhallsson, Baldur, and Anders Wivel. 2006. “Small States in the European Union: What Do We Know and What Would We Like to Know?” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 19 (4): 651–668.

- Thürer, Daniel. 1998. “The Perception of Small States: Myth and Reality.” In Small States Inside and Outside the European Union: Interests and Policies, edited by Laurent Goetschel, 33–42. Boston,MA/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Verdun, Amy. 2013. “Small States and the Global Economic Crisis: An Assessment.” European Political Science 12 (3): 276–293.

- Verdun, Amy. This issue. “The Greatest of the Small? The Netherlands, the New Hanseatic League and the Frugal Four.” German Politics.

- Vilpišauskas, Ramūnas. This issue. “Baltic States in the Economic and Monetary Union: Standing in the Shadow of Germany or Helping to Counterbalance ‘the South’?” German Politics.

- Waltz, Kenneth N. 1979. Theory of International Politics. Boston: Mc Graw-Hill.

- Webber, Douglas. 1999. The Franco-German Relationship in the European Union. London and New York: Routledge.

- Webber, Douglas. 2019. European Disintegration? The Politics of Crisis in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan / Red Globe Press.