Abstract

The relationship between Austria and Germany is characterised by many political and cultural commonalities and strong economic interdependencies. Moreover, the asymmetry between the two countries, both in terms of economic size and political power, has long time characterised the relationship as one between ‘leader’ and ‘follower’. Yet, despite these strong ties, Austria has assumed an increasingly independent role in recent EMU politics. Therefore, this article asks whether and why the close partnership of the two countries is slowly growing apart. Based on the analysis of three periods of EMU reform, the article shows that Austria followed Germany during the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis (2010–12), became more self-reliant in its slow-burning phase (2012–16), and even opposed German positions in post-crisis reform (2016–20). Converging economic preferences and the strong power asymmetry between the two countries can explain Austria’s cooperative strategy until 2016. By contrast, Austria’s shift from loyal followership towards more pronounced independence is largely caused by domestic developments. The reluctance of the Austrian government to share risks and build joint capacities in EMU reflects a Europe-wide trend, as an increasing ‘constraining dissensus’ at the national level makes it difficult for small state governments to compromise at the European level.

Introduction

In May 2020, France and Germany presented a joint proposal for a ‘Recovery Fund’ to fight the consequences of the Corona crisis. The ambitious proposal involved not only a common European debt instrument, but also grants for crisis-stricken member states (Bundesregierung Citation2020). These elements signal a departure from a long-standing position of Germany, which has traditionally opposed far-reaching European risk mutualisation and fiscal redistribution. The proposal received immediate and outright opposition from smaller creditor countries, expressed most saliently by Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, who gathered the ‘Frugal Four’ (Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands) to support him. Together, the four countries prepared a more restrictive counterproposal, which was based on loans instead of grants. The three Austrian allies also participated in a small-state coalition labelled the ‘New Hanseatic League’, which inter alia opposed a Franco-German proposal for a euro area budget (Schoeller Citation2020b). At the time, Austria signalled support for the New Hansa, but did not officially join their club. Hence, while Austria has been a very close ally of Germany since the introduction of the single currency, more recent episodes like that of the eurozone budget or the Corona recovery fund point to an increasing divergence of preferences between the two neighbours. Therefore, this article asks whether and why the close partnership of the two countries is slowly growing apart.

The article argues that Austria followed Germany when the eurozone’s most powerful state was representing their shared interests as ‘creditor states’ in EMU negotiations on fiscal risk-reduction and risk-sharing (2010–12). During the reform of EMU’s financial governance (2012–16), however, the Austrian government started to pursue a more independent – albeit not opposing – strategy. Only in the post-crisis period since 2016, when Germany signalled substantial concessions to France, Austria has openly departed from German negotiation positions. While we explain Austria’s cooperative strategy towards Germany until 2016 with overlapping economic preferences, the large power asymmetry and the dense institutional fabric (Krotz and Schild Citation2013) of the bilateral relationship, we attribute the Austrian departure from loyal followership towards more pronounced independence to domestic developments. In particular, the increasingly ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009) limits the room for manoeuvre of the Austrian government when it comes to making compromises at the European level.

Empirically, the article’s contribution thus consists in mapping and explaining the evolving preference constellation between Germany and Austria. In doing so, the article shows that the recent trend of smaller creditor states to emancipate themselves from Germany even applies to Austria as one of Germany’s closest allies (Jones, Citation2021; Schoeller Citation2020a). In addition, the empirical analysis allows us to identify the varying strategies Austria has been using to pursue its preferences. From a theoretical perspective, a changing relationship of the two countries represents a least likely case for the conceptual framework of this special issue, since the values of the central variables – preferences, power asymmetry, and institutional fabric – have largely remained the same (see Schoeller and Falkner, Citation2021). In the following analysis, we therefore open the ‘black box’ of states and focus also on domestic developments as an additional explanatory factor of the evolving partnership.

The article is structured as follows. The next section (2) provides the empirical background to our theory-guided analysis by elaborating on the special economic, political and cultural relations between Austria and Germany. We then proceed to present our theoretical expectations, methods and data (3). In our subsequent empirical analysis (4), we examine selected EMU reforms by analytically distinguishing three periods since the outbreak of the euro crisis in 2010. We then summarise and discuss our findings (5), before we draw our conclusions in the last section (6).

Commonalities, Differences and Asymmetric Interdependence

Austria and Germany have a special relationship, which is characterised by many political and cultural commonalities as well as strong economic interdependencies. The two countries share not only the same language, but also a long-standing history. Nowadays, there remains a vivid cultural and parapublic exchange between the two countries, which is underpinned by the fact that more than 200.000 Germans live in Austria (representing 2.3 per cent of the population and thus the largest group of foreigners), while 186.000 Austrians reside in Germany (Statistik Austria Citation2020; Statistisches Bundesamt Citation2020a). Moreover, the political systems of the two countries are very similar. Their parliamentary democracies share key ingredients, such as proportional representation, federalism, a key role of political parties (‘party democracies’), and similarities in the party systems, which are reflected in the parliamentary representation of a populist right-wing party (FPÖ – AFD), a dominant conservative/centre-right party (ÖVP – CDU/CSU), traditionally strong social democrats (SPÖ – SPD), a liberal (Neos – FDP) and a green party (Die Grünen – Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), respectively.

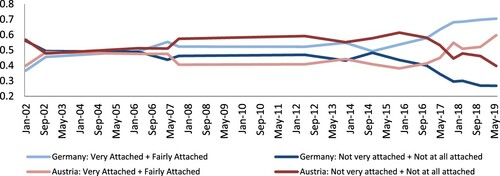

However, Austria and Germany also differ in some important aspects. In addition to their obvious difference in size, Germany is a co-founder of what has become today’s EU, whereas Austria joined the EU only after a referendum in 1995. Moreover, despite many similarities in the political attitudes, public opinion differs in the two countries with Austria being more Eurosceptic according to Eurobarometer polls (see ). In contrast to Germany, Austria also faced EU diplomatic sanctions in 2000. They were a reaction to racist statements by politicians of the radical right party FPÖ, which at that time had become part of the Austrian government. While the sanctions were lifted after consideration of an EU commissioned report of three wise persons, the Austrian centre-right government came out more strongly and unified after that period (Falkner Citation2001, 12). The FPÖ remained in government (after the split of the party as BZÖ) until 2007, positioned itself successfully as EU- and euro-sceptic, and entered the first government of ÖVP Chancellor Sebastian Kurz from 2017 to 2019.

Figure 1. Attachment to the EU in Austria and Germany 2002–2019.

Source: Eurobarometer, own calculation and presentation.

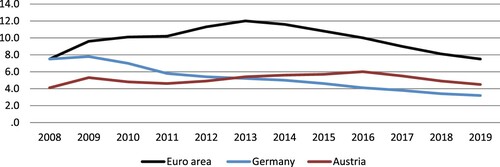

Austria and Germany also share important political-economic features. Both countries are so-called ‘creditor states’ in EMU, as they have relatively sound fiscal positions and run a permanent current account surplus. While they are both characterised by very open economies, Austria is even more trade dependent than Germany, with exports amounting to more than 50 per cent of its GDP (OECD data). Their economic adjustment strategy proved successful to the extent that both countries achieved higher economic growth and lower unemployment rates than the EMU average (), budget surpluses and relatively low debt levels before the breakout of the Corona crisis.Footnote1 In addition, the banking sectors of both countries are composed of a high number of public, cooperative and savings banks (Landesbanken, Sparkassen, Volksbanken and Raiffeisenbanken) with high importance for the financing of small and medium sized companies.

Figure 2. Unemployment in Austria, Germany and the Euro area, 2008–2019.

Source: Eurostat, own presentation.

While the two economies are strongly interdependent, their difference in size results in an obvious asymmetry of the relationship. Germany’s population and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are around nine times higher than in Austria, with Germany amounting to 27 and Austria to 3 per cent of total euro area GDP (OECD data). For Austria, Germany is by far the most important trading partner accounting for more than 30 per cent of all exports and even 35 per cent of total imports. Vice versa, Austria is ‘only’ the seventh most important trading partner for Germany when it comes to exports, while it ranks ninth in terms of imports. Moreover, Austria is more dependent on trade with EU members than Germany. While 70 per cent of Austrian exports go to the EU, the German economy is more globalised and maintains stronger ties to the US, China and the UK (Statistisches Bundesamt Citation2020b; WKÖ Citation2020a). The asymmetric interdependence between the two economies is also reflected in the important tourism sector, which amounts to more than 15 per cent of Austria’s GDP. In this key sector for Austria, Germans accounted for 50 per cent of overnight stays by foreigners in 2019 (WKÖ Citation2020b, 47).

Theoretical Expectations and Implications for the Empirical Analysis

In the introduction of this special issue, Schoeller and Falkner suggest that the strategies of smaller states and their interaction with Germany are a result of three key factors: the distance of preferences from the status quo, the asymmetry of power between a smaller state and Germany, and the regularised political, cultural and parapublic exchange (‘institutional fabric’) between the two countries. Drawing on our above discussion of the two countries’ commonalities, differences and interdependencies, these theoretical propositions allow us to derive concrete expectations that inform our subsequent analysis.

First, both Austria and Germany are creditor states. We therefore expect that the two countries have converging preferences for maintaining the status quo in EMU. Since Germany, as EMU’s ‘reluctant hegemon’ (Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013), has often played a ‘foot-dragging’ role in EMU reform, we expect Austria to act as a ‘fence sitter’. However, should Germany depart from the previously shared position in favour of the status quo, we expect Austria to ‘drag its feet’. Second, as the power asymmetry between the two countries is substantial, we expect Austria to choose ‘soft’ strategies in relation to Germany, for instance arguing or framing, rather than opting for bargaining-based strategies such as using veto-threats or building counter-coalitions. Third, the political and cultural commonalities, the economic interdependencies and the strong parapublic exchange between Germany and Austria provide for a dense ‘institutional fabric’. As regards the ‘regularized intergovernmentalism’ (Krotz and Schild Citation2013) between the two countries, for instance, they have frequent exchanges at the working level of government officials and they collaborate in special forums like the meeting of German-speaking finance ministers (accompanied by Luxembourg, Switzerland and Liechtenstein) on an annual basis (Interview AT1). We therefore expect Austria to opt for bilateral contacts to Germany rather than bypassing it in multilateral settings such as the EU institutions.

In summary, based on the framework of Schoeller and Falkner (Citation2021), our theoretically informed expectations are as follows:

Austria acts as a ‘fence sitter’ if it shares positions with Germany. If Germany changes its position, Austria will make use of ‘foot-dragging’ strategies.

Austria relies on persuasion strategies rather than hard bargaining in its interaction with Germany.

Austria opts for bilateral rather than multilateral strategies in interacting with Germany.

In the remainder of this article, we provide a theory-guided analysis of the changing relationship between Austria and Germany in EMU politics. Accordingly, we examine institutional issues of EMU reform that occurred from 2010 to mid-2020. In particular, we analyse crucial fiscal and financial integration projects in three periods: the fiscal reforms in the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis from 2010 to 2012, the financial reforms in the slow-burning phase from 2012 to 2016, and three major projects in the period from 2016 to 2020 (Euro Area Budget, European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS) and Corona Recovery Fund). The analysis first identifies the preferences and strategies of the two countries. Subsequently, we examine how our cases map on the theoretical propositions. Where our findings diverge from the theoretical expectations, we inductively identify plausible causes for the mismatch between expectations and findings as well as explanations for change in the bilateral relationship over time. This approach rests on a triangulation of various sources providing us with primary and secondary data (legislative files, policy disseminations, press statements, publicly available data, previous studies such as the EMU choices project and secondary literature). We cross-check this information by own in-depth elite interviews with high-ranking officials who are closely involved in EMU politics. These interviews were used as a complementary source to validate and deepen our findings.

Empirical Analysis: Staying Together or Growing Apart?

Starting in 2010, the euro crisis posed an existential threat to the single currency and forced policy makers to reform EMU. In the eyes of most observers, the problems of EMU stem from its asymmetric institutional design. While monetary policy has been delegated to the independent European Central Bank (ECB), fiscal and financial policy remained largely national prerogatives. Therefore, member states not only had to coordinate institutional solutions in response to the crisis, but also had to face the distributional consequences of adjusting to the new circumstances. While the ‘creditor states’, including Austria and Germany, preferred to keep the adjustment costs at the national level by reinforcing austerity measures and structural reforms, the ‘debtor states’ preferred to shift adjustment to the European level by establishing common fiscal capacities and refinancing mechanisms. In a first ‘fast-burning’ phase of the euro crisis, governments focused on strengthening fiscal rules and providing financial assistance (2010–2012). In a second ‘slow-burning’ phase (2012–2016), reforms concerned primarily the euro area’s financial architecture (Carstensen and Schmidt Citation2018). While Germany and Austria had been close allies throughout these crisis periods, their relationship has shown signs of growing apart over negotiations on further integration steps in the latest period since 2016.

EMU Reform in the Fast-Burning Phase of the Euro Crisis: Austria as a Loyal Follower

The euro crisis brought enhanced supervision of fiscal policies and financial assistance mechanisms on the European agenda (Chang Citation2013). First, EMU’s institutions designed to rein in public finances, most notably the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the ‘no bailout clause’, turned out to be insufficient (Buti and Carnot Citation2012). Against the background of looming refinancing difficulties in some member states and contagion risks for the rest of the eurozone, the SGP was reinforced through the so-called ‘Six Pack’ and ‘Two Pack’ measures. Moreover, a ‘Fiscal Compact’ between member states should enshrine balanced budget rules into national law (Laffan and Schlosser Citation2016). Second, the sovereign debt crises in Greece and other member states required the establishment of financial assistance mechanisms, notably the temporary European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and its permanent successor, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

Many of these post-crisis EMU reform steps have a traceable ‘German fingerprint’ and favour the preferences of creditor states (e.g. Schimmelfenning Citation2015). Since the consent of the largest and economically most powerful eurozone member was required for all projects related to financial assistance, Germany could exert considerable influence in the fast-burning phase of the crisis, especially when it managed to get France on board (Schoeller Citation2018b). Hence, while it was reluctant with regard to risk-sharing and capacity-building in the eurozone, Germany took the lead on a coalition of creditor states that advocated the enhancement of fiscal rules and austerity measures as a condition for financial assistance (Schoeller Citation2018a, Citation2019).

Throughout these reforms, the Austrian governments followed Germany’s fiscally conservative negotiation positions. Exchanges of views were frequently held on staff working levels, but the Austrian government saw little need to approach the Germans outside the multilateral settings, as they shared the general German line (Interview AT1). The Austrian government joined Germany in its demands for fiscal rule enforcement, such as in the cases of Reversed Qualified Majority Voting in the ‘Six Pack’ or the demand for ‘strict conditionality’ in the ESM (Nationalrat Citation2011a). Accordingly, Austria also followed the German initiative of linking the ESM to the Fiscal Compact (Nationalrat Citation2012a). Besides the agreement on the general terms of eurozone crisis management, some of Austria’s more nuanced positions diverged from those of Germany. During the ESM negotiations, for instance, the Austrian government was open to a larger ESM volume, which could have signalled more ‘firepower’ to the anxious financial markets (Schult Citation2012). Important Austrian decision-makers, such as the Governor of the Austrian National Bank, presented these positions as technical rather than political issues (Gocaj and Meunier Citation2013, 249), which was welcomed by the grand coalition government led by social democrats. This allowed the Austrian government to let the Germans push for austerity and conditionality, thereby avoiding risk-sharing and redistribution in the eurozone, while showing some public understanding for the southern member states. This was the case, for instance, when Austrian Chancellor Faymann tried to mediate between Greek Prime Minister Tsipras and the German government in 2015 (Vytiska Citation2015).

Such departures from Austria’s ‘fence-sitter’ role in the first phase of the eurozone crisis are arguably caused by domestic factors. As regards the above-mentioned case of the ESM, for example, the grand coalition needed the votes of the fiscally less conservative Greens in the parliament to reach the necessary 2/3 majority and therefore supported a larger volume (Nationalrat Citation2012b). In the case of the Fiscal Compact, by contrast, not only the euro-sceptic FPÖ, but also the Greens were firmly against the instrument (Nationalrat Citation2011b). This prevented the Austrian government from incorporating the debt brake into constitutional law as demanded by Germany. The government reached a compromise only by linking the conservatives’ support for the Fiscal Compact with the left’s approval of the ESM. In the end, the ‘Austrian Stability Pact’ (BGBI. No. 30/2013) was thus given the status of an Interstate Treaty which is in effect equivalent to constitutional legislation (Burret and Schellenbach Citation2014).

In summary, in the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis between 2010 and 2012, Austria proved to be a loyal follower of Germany. As Germany represented most of Austria’s positions in crisis management, the latter could adopt the role of a fence-sitter, thereby free-riding on the negotiation efforts of its bigger neighbour. In the few cases where Austria departed from Germany’s positions, this was due to domestic politics.

Financial Governance Reform in the Slow Burning Phase of the Euro Crisis: Austria as a Self-Reliant Ally

The euro crisis revealed also the failure of the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS) to address the vicious circle between sovereign debt and banks’ balance sheets (‘doom-loop’). Hence, the ‘Four Presidents Report’ of June 2012 (EUCO Citation2012) called, inter alia, for central financial supervision, a European resolution mechanism, and a common deposit insurance scheme. Following up in the same year, the European Commission advanced a number of initiatives, which are known as the ‘Banking Union’. Many observers regard the Banking Union as one of the most significant steps of European integration since the Maastricht Treaty (e.g. Heidebrecht Citation2017). The Banking Union consists of three pillars: banking supervision, bank resolution, and, so far unrealised, a common deposit insurance scheme.

First, by adopting the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) in October 2013, direct financial supervision powers over the euro area’s ‘most significant banks’ were transferred to the ECB. Second, a directive on banks’ recovery and resolution (BRRD) sets out so-called ‘bail-in’ rules (BRRD Article 37.51–52). Moreover, the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) allows bank resolution through a Single Resolution Board (SRB) and a Single Resolution Fund (SRF), which shall be fully operational in 2023 (see Howarth and Quaglia Citation2014). The third element, a directive on deposit guarantee schemes, was proposed by the Commission already in 2010 (European Commission Citation2010) but stalled due to German and Austrian opposition (Howarth and Quaglia Citation2018, 193). In November 2015, the Commission proposed a regulation to set up EDISFootnote2, which has so far not materialised mainly due to German opposition. This time, however, the Austrian government has been more willing to proceed with EDIS, and actually advanced the debate under its EU Presidency in 2018.

In the Banking Union, German preferences are reflected less significantly than in the EMU reforms during the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis (Schild Citation2018). Moreover, the German banking sector was divided on key issues of the reform proposals. The two large private banks (Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank) were in favour of an all-encompassing scope of the SSM (Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016, 452) and called for joint funding for the SRM. However, the influential public and savings banks collectively lobbied for a limited scope of the Banking Union (BVR/VÖB/DSGV Citation2012) and a system of national resolution funds, which became the position of the German government (Howarth and Quaglia 2014). In order to shield the institutional protection scheme of its ‘alternative banks’, Germany has also vetoed EDIS (Interview EX1).

The Austrian government followed the German concerns in some respects, especially when it comes to the pooling of resources, but it diverged and presented a more integration-friendly position on apparently technical issues that do not involve fiscal transfers. Austria joined Germany in arguing against a mutualisation of funds for bank rescues, which however materialised through the gradual integration of national resolution funds into the SRF. By contrast, Austria diverged from the German position regarding the scope of the Banking Union, its decision-making rules and the role of the ESM in the transition period to an effective SRM. While Austria initially aligned itself with Germany in its demands for a narrow scope of the SSM (including only the largest banks) and a strong role of member states in bank resolution, and even joined the German opposition against centralised supervision under the auspices of the ECB, it quickly softened all of these positions in the negotiation process. Finance Minister Maria Fekter (2011–13) and her successor Michael Spindelegger (2013–14; both ÖVP) signalled that they could compromise on a wider scope of the SSM, centralised supervision by the ECB, and exclusion of Member States interference in bank resolution (e.g. Hacker-Walton and Sileitsch-Parzer Citation2013; Nationalrat Citation2014). This reflects an intermediate position between the conservative preferences of Germany and the integrationist preferences of Southern member states. The Austrian government pursued its preferences through public arguing rather than using hard bargaining strategies towards Germany. For instance, Finance Minister Fekter publicly criticised the German negotiators for maintaining stubborn positions sheltering their alternative banks (Euronews Citation2012) and Finance Minister Spindelegger questioned the at the time unsuccessful discussions about using the ESM as a backstop for the SRF (Der Standard Citation2014).

Why is Austria, despite being a creditor state, more willing to make concessions to the demands of southern member states for greater centralisation of banking supervision and resolution than Germany? An explanation can be found in the different banking systems and the domestic politics of the two countries. While both countries have a large system of alternative banks, the Austrian cooperatives rely on a joint liability arrangement built around two of the most internationalised banks in Europe (Volksbank and Erste). These banks have a strong exposure to southern and eastern Europe. While joint supervision could enhance the control of the Austrian government over the foreign subsidiaries of its internationalised banks, these banks would obtain a more levelled playing field. Hence, the more internationalised structure of its banking system provides the Austrian government with incentives for supranational solutions, whereas German politicians seek to protect their politically well embedded and less internationalised alternative banks (Howarth and Quaglia Citation2016, 452–453). Accordingly, the Austrian government’s shift towards more European financial integration was discussed favourably by most political groups in the parliament, with the sole exception of the FPÖ (Nationalrat Citation2014).

Hence, in the slow-burning phase of EMU reform, Austria left its fence-sitter position and moved towards a more active and self-reliant role. Sharing Germany’s opposition against greater risk-sharing in EMU, the Austrian government still acted as an ally of Germany. However, it also expressed its diverging positions with regard to banking supervision, resolution and EDIS, and thus became a more active ‘co-shaper’ of the Banking Union. At the same time, the moderate stance of the Austrian grand-coalition government faced a more Eurosceptic public than the German government (see above). The FPÖ won seven additional percentage points in the European election of May 2014, thereby reaching almost twenty percent of votes and thirteen percent more than the euro-sceptic AFD in Germany at the time. This points to an increasing ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009) which the Austrian government has to deal with when adopting integrationist positions in EMU.

Post-Crisis Reform and Corona Response: Austria as a Self-Assertive Small State

The historical influx of refugees in 2015 increased the camp of EU-sceptical parties in both countries. In Austria, however, the ‘Schengen Crisis’ not only led to more scepticism towards the EU, but also towards Germany and its Chancellor Angela Merkel. Although the German Chancellor’s famous dictum ‘wir schaffen das’ (‘we can do it’) was welcomed by the Austrian SPÖ and parts of the Austrian civil society, the crisis led to an increasing popularity of the FPÖ, which temporarily reached more than 30 per cent in Austrian opinion polls (Rheindorf and Wodak Citation2018, 16). For the Austrian government, and in particular then Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz (ÖVP), this provided an incentive to openly depart from the German line. Kurz announced his opposition to Germany and signalled his support to ‘close the Balkan route’ (Die Presse Citation2016). He also supported Hungary in building up a fence on its Serbian border and joined the demand for restrictive solutions (see Rheindorf and Wodak Citation2018).

At the same time, the political clout of the FPÖ increased further. The success of FPÖ candidate Hofer and the poor performance of the SPÖ candidate in the first round of the Austrian presidential election led to the resignation of Social Democratic Chancellor Faymann in May 2016 (Kogelnik, Egyed, and Völker Citation2016). After an early election in 2017, the FPÖ reached almost 26 per cent of votes and became a strong partner in the first government coalition of Chancellor Kurz. While the German AFD received ‘only’ 12 per cent in the federal elections of 2017, the new government in Austria was partly built on populist positions expressing scepticism towards European integration and, at least in the context of the Schengen crisis, German-led crisis-management. In the subsequent debates and negotiations on fiscal integration (Eurozone Budget and Corona Recovery Package) and EMU financial architecture (EDIS), Austria took an increasingly independent stance.

The increasing Austrian independence became visible in the negotiations about further fiscal integration, as proposed by France and Germany in their joint ‘Meseberg Declaration’ (Deutsche Bundesregierung Citation2018a). In response, a group of eight northern creditor states, referred to as the ‘New Hanseatic League’, expressed outright opposition to the proposed Eurozone Budget (see Schoeller Citation2020b; Verdun, Citation2021). Austria signalled its sympathy for the New Hansa, but, due to its 2018 EU Presidency and diverging preferences regarding other EMU reform issues such as the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures, refrained from joining the club (Interview AT1; Schoeller Citation2020a). In particular, Austria expressed legal concerns with regard to the euro area budget and shared the criticism of the New Hansa (Die Presse Citation2018). Moreover, Chancellor Kurz underlined the ‘like-mindedness’ and formulated joint positions in public statements (Kurz Citation2020). In the Eurogroup negotiations of June and October 2019, the Franco-German proposal of a genuine Eurozone Budget was watered down and converted into a reform delivery tool within the EU budget, labelled ‘Budgetary Instrument for Convergence and Competitiveness’ (BICC), before it was silently dropped in the context of the Corona crisis measures (Schoeller Citation2020b).

A similar pattern can be observed with regard to EDIS. In this case, however, the Austrian government diverged from the German stance by positioning itself as a mediator between Germany and the ‘periphery’. The new position became most obvious during the Austrian EU Council Presidency in the second half of 2018, where Austria pro-actively advanced the debate on EDIS despite German resistance (Interviews AT1, BRU4). By contrast, during the first discussions in 2010, a common deposit insurance scheme was still blocked jointly by Austria and Germany (Howarth and Quaglia Citation2018, 193). Since the European Commission’s 2015 proposal to establish an EDIS (European Commission Citation2015), the issue has been negotiated only at a technical level, with member states being split into two camps: while one camp feared that their banks would become net contributors to the scheme (notably Germany), the other camp demanded early risk-sharing at the European level (Donnelly Citation2018). Against this background, the Austrian government made its proposal for a ‘hybrid model’ of EDIS. This model represents a compromise by suggesting an EDIS that is anchored both at the national and the European level. It envisages the build-up of a centralised fund through contributions from national deposit insurance schemes. National level deposit insurance schemes encountering shortfalls could, however, request liquidity from the European level only after having depleted their own funds (European Council Citation2018). Although the Austrian proposal represents a middle-ground in the debate about an EDIS, it received unchanged opposition from the German government, referring to remaining moral hazard concerns (Bundesregierung Citation2018b). An apparently more moderate stance expressed by German Finance Minister Scholz in November 2019 (Scholz Citation2019) has been regarded as largely symbolic due to hardly realisable conditions attached to his proposal (Interviews AT1, DE1).

Facing the severe consequences of the Corona crisis starting in early 2020, France and Germany proposed in May 2020 to set up an ambitious European Recovery Fund (Bundesregierung Citation2020). The proposal represented an unprecedented shift in Germany’s position on fiscal integration, as the Fund, with an envisaged volume of EUR 500bn, should be based on grants to member states (instead of loans) and be financed by the European Commission borrowing on financial markets. To the extent that such a fund would constitute an EU debt instrument, for which member states would ultimately share the risk, it resembled the controversial Eurobonds proposal which had long time been opposed by Germany (Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015). Although the proposed Fund would only be temporary, it was hailed as a potential ‘Hamiltonian moment’ for the EU.

The Franco-German proposal faced immediate and outright opposition by Austrian Chancellor Kurz, who was joined by his ministers of Finance and European Affairs (Der Standard Citation2020). In a media-effective manoeuvre, the Austrian government took on a leading role in mobilising the ‘Frugal Four’ (Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden) as an explicit counter-coalition to the Franco-German plan. The Frugal Four even drafted a counter-proposal based on loans instead of grants (Murphy Citation2020). While the FPÖ was cohesively against the Franco-German initiative (FPÖ Citation2020), the Austrian Green Party – junior coalition partner in the second Kurz cabinet since January 2020 – was closer to the Franco-German line (OÖN Citation2020). Already in their 2019 election campaign, the Austrian Green Party had called for relaxed fiscal rules in EMU (Die Grünen Citation2019, 79). Consequently, leading Green politicians such as Vice-Chancellor Werner Kogler and ‘Europe’ spokesperson Michel Reimon criticised Chancellor Kurz’ ‘frugal’ position in the parliament debate and the media (Österreichischer Nationalrat Citation2020; SN Citation2020). However, the diverging positions of the Greens did not have any traceable impact on Kurz’ government position, which, on the contrary, became even more opposed to fiscal redistribution in EMU.

On July 21, the European Council adopted conclusions on the Corona recovery plan, which can be interpreted as a compromise between the Franco-German tandem and the Frugal Four. According to the final agreement, support under the recovery plan (Next Generation EU) will only in part be based on grants (EUR 390 billion), whereas almost a half of the funds will be paid out as loans (EUR 360 billion). While the Frugal Four reluctantly agreed to debt-financed grants as proposed by Germany and France, they succeeded in reducing the amount of grants and cutting some countries’ contributions to the EU budget. Accordingly, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands benefit from reduced contributions for the 2021–2027 period (European Council Citation2020, 65).

The episode of the Franco-German recovery fund proposal reminds of crisis management in the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis, when the two countries exerted co-leadership and smaller countries would eventually gather behind an emerging compromise (see Schild Citation2013). For Austria, however, this latest episode means the most obvious departure from its previous role as a fence-sitter and loyal partner of Germany towards a more independent role in E(M)U politics. While in the case of EDIS Austria acted as a ‘co-shaper’, it assumed the role of a ‘foot-dragger’ in the cases of the Eurozone Budget and the Corona Recovery Fund proposal. However, when Austria opposed the Eurozone Budget proposal, it relied exclusively on ‘soft’ strategies such as public arguing and framing. When it came to the Corona Recovery Fund, by contrast, the Austrian government also engaged in building counter-coalitions to defend the status quo in EMU (see Schoeller and Falkner, Citation2021).

Explaining Change in a Special Relationship

Our empirical findings are summarised in . The two countries’ positions were closely aligned throughout the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis (2010–12), when the European response focused primarily on fiscal policy. The slow-burning phase (2012–16), by contrast, was more about financial governance and regulation. While Austria and Germany took a common stance against centralisation and mutualisation at the outset of the negotiations, Austria was soon ready to make concessions towards greater integration of financial supervision and bank resolution. The ensuing period, which was overshadowed by diverging preferences in coping with the ‘Schengen crisis’, further divided the two countries. In the area of fiscal policy, Germany departed from its strict stance against fiscal capacity-building in EMU, which it had previously shared with Austria. Austria thus became a foot-dragger. In the realm of financial governance, instead, the Austrian government acted as an active co-shaper despite Germany’s reluctance to complete Banking Union. The Corona crisis divided the positions of the two countries even further. Germany, together with France, made a far-reaching proposal for a recovery fund that included common European debt instruments and transfers in the form of grants, whereas Austria took the lead of a counter-coalition (‘Frugal Four’) opposing generous financial assistance. Hence, if we apply the typology proposed by Schoeller and Falkner in this issue, Austria has moved from a fence-sitter to a foot-dragger in fiscal policy, whereas it has become a co-shaper in the area of financial governance.

Table 1. Summary of findings.

The analysis of the two countries’ relationship in light of our theoretical propositions allows us to paint a nuanced picture of the Austrian-German relationship in EMU. The empirical findings largely confirm our first expectation: Austria acts as a ‘fence sitter’ as long as it shares positions with Germany. If Germany changes its positions, Austria makes use of ‘foot-dragging’ strategies. However, our analysis also shows that not only Germany changes its positions. In the case of financial governance, where Germany has so far kept its firm opposition against EDIS, Austria has adopted a more differentiated and integration-friendly position. We therefore argue that Austria’s changing role in EMU politics cannot be explained by focusing only on the preference constellation at the international level. We also have to consider domestic factors. As regards Banking Union, Austria’s move towards a co-shaping role can be explained with the structure of its banking sector and, in particular, the central role of two strongly internationalised banks. In other areas, such as fiscal integration, our analysis suggests that the participation of the Eurosceptic FPÖ in government (2017–19) and the assertive governing style of Chancellor Kurz, who is responsive to the Eurosceptic parts of his electorate, have contributed to a change in the bilateral relationship. By contrast, the participation of the Austrian Greens as a coalition partner in government has apparently not altered the government’s frugal stance in EMU. This may be explained by the fact that Chancellor Kurz seeks to attract voters from the target group of the FPÖ rather than from that of the Greens. Concessions to typical FPÖ positions are therefore more rewarding for the Chancellor than compromises with the Greens.

Second, given the power asymmetry between the two countries, we expected Austria to rely on persuasion strategies rather than hard bargaining with Germany. Our analysis largely confirms this expectation, too, albeit with a notable deviation in the most recent Corona crisis management. For the first time, Austria set out to oppose a Franco-German proposal by actively building a counter-coalition rather than relying on ‘soft strategies’ such as persuading with the ‘better argument’. During the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis, Austria largely followed Germany in its negotiation positions. When Germany changed its positions with the (in)famous Meseberg declaration, Austria argued against the proposal of a Eurozone budget based on legal considerations and tried to convince Germany to support more Europeanisation in the area of financial integration through lobbying and, occasionally, even ‘shaming’. While the use of such persuasion-based strategies is perfectly in line with our theory-guided expectation, the most recent attempts at coalition-building cannot be sufficiently explained with the power asymmetry between the countries, which has remained relatively stable. Instead, we also have to take account of an increasingly assertive government under Chancellor Kurz, which responds to the Eurosceptic parts of its electorate by defending the alleged national interest against excessive European integration and fiscal profligacy in Southern member states.

Our third proposition expects Austria to opt for bilateral rather than multilateral strategies in interacting with Germany. This expectation has been partly disconfirmed. Despite the constantly dense ‘institutional fabric’ between the two countries, which manifests itself in a regularised intergovernmental exchange and strong parapublic underpinnings (e.g. in higher education or cross-border cooperation projects), Austria has not always chosen bilateral venues. Instead, it has increasingly bypassed Germany through multilateral settings. Not only has Austria joined a more integration-friendly coalition in completing the Banking Union and even acted as a multilateral broker in the EDIS debate; in the negotiations about a Corona recovery package, the Austrian government has even joined an explicit counter-coalition (‘Frugal Four’). This suggests that under conditions of high issue salience and Eurosceptic tendencies in the domestic arena, strong preferences reflecting the alleged national interest trump the institutional fabric of the Austrian-German relationship.

Conclusions

Analysing and comparing three periods of EMU governance and reform, we have shown how the asymmetric, but close partnership of Austria and Germany is slowly growing apart. Especially in the fast-burning phase of the euro crisis, Austria followed its bigger neighbour. Since then, however, Austria has assumed an increasingly independent role in EMU politics. To be sure, the special relationship between the two countries is still sustained by a strong foundation of cultural, political and economic commonalities and interdependencies. Yet, the government participation of the populist radical right FPÖ (2017–19) and an assertive Chancellor, who is responsive to the Eurosceptic parts of his electorate, have led to a more reluctant stance on risk-sharing and capacity-building at the European level. It would be an interesting task for future research to investigate as to why the participation of the Greens has not reversed that trend. In any case, these findings tie in with the more general argument of Jones in this issue, who contends that smaller states find it increasingly hard to follow Germany or the Franco-German tandem as the rise of right-wing populist tendencies creates a ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009) that makes it difficult for small state governments to make concessions at the European level.

With regard to the theoretical framework of this special issue, our findings suggest that the ‘domestic variable’ may need to be considered more explicitly when explaining the role of small states in dealing with a regional hegemon. For instance, Austria’s outspoken opposition to the Franco-German recovery plan in coping with the Corona crisis reflects domestic developments rather than the dense institutional fabric of the bilateral relationship. Here, domestically induced short-term interests seem to trump long-term path dependencies. However, apart from such country-specific idiosyncrasies, the preference constellation and the power asymmetry between Austria and Germany can explain large parts of the relationship.

In political terms, the more inward-looking strategy by the Austrian government might turn out to be detrimental to its own goals. The government’s minor coalition partner, the Austrian Green Party, has become warier about the Chancellor’s EU policy, and also the EU-export dependent Austrian economy could become more critical about the government’s restrictive positions. Parts of the constituency might take the view that the Austrian success as a creditor state rests on the integration of its relatively small and open economy into the single market. One may therefore wonder whether Austria would not pursue its preferences better by assuming collective responsibility for the European integration project in the form of a self-confident partnership with Germany than by defending its current benefits in a persistently incomplete EMU.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Heidebrecht

Sebastian Heidebrecht is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for European Integration Research (EIF), Department of Political Science, University of Vienna. His research focuses on current issues of European integration, in particular EU digital policy and European economic and monetary policy. His research has appeared with Routledge and in journals such as the Journal of Political Science (Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft) and the Journal of Contemporary European Research.

Magnus G. Schoeller

Magnus G. Schoeller is Principal Investigator and APART-GSK Fellow of the Austrian Academy of Sciences at the Centre for European Integration Research (EIF), Department of Political Science, University of Vienna. His research on the governance of Economic and Monetary Union, Germany’s role in the EU, and political leadership appeared with Palgrave Macmillan and journals such as the European Political Science Review, the Journal of European Public Policy, or the Journal of Common Market Studies.

Notes

1 For 2019, the numbers are 59.8 per cent of GDP in Germany and 70.4 percent in Austria (Eurostat).

2 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52015PC0586 last accessed 2020-05-22.

References

- Bulmer, Simon J., and William E. Paterson. 2013. “Germany as the EU’s Reluctant Hegemon? Of Economic Strength and Political Constraints.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (10): 1387–1405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.822824.

- Bundesregierung. 2020. “A French-German Initiative for the European Recovery from the Coronavirus Crisis.” Pressemitteilung 173/20. https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/973812/1753772/414a4b5a1ca91d4f7146eeb2b39ee72b/2020-05-18-deutsch-franzoesischer-erklaerung-eng-data.pdf?download=1.

- Burret, Heiko T., and Jan Schellenbach. 2014. “Implementation of the Fiscal Compact in the Euro Area Member States: Expertise on the behalf of the German Council of Economic Experts.” Working Paper 08/2013, partly updated 2014, Walter Eucken Institute.

- Buti, Marco, and Nicolas Carnot. 2012. “The EMU Debt Crisis: Early Lessons and Reforms.” Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (6): 899–911. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02288.x.

- BVR/VÖB/DSGV. 2012. Gemeinsames Positionspapier zu einem Einheitlichen Aufsichtsmechanismus für Kreditinstitute, Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken; Bundesverband Öffentlicher Banken Deutschlands; Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband, September 3.

- Carstensen, Martin B., and Vivien A. Schmidt. 2018. “Power and Changing Modes of Governance in the Euro Crisis.” Governance 31 (4): 609–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12318.

- Chang, Michele. 2013. “Fiscal Policy Coordination and the Future of the Community Method.” Journal of European Integration 35 (3): 255–269.

- Der Standard. 2014. “Bankenabwicklung weiter offen: Spindelegger sieht noch Diskussionsbedarf in Europa.“ Der Standard, January 28, 2014. https://www.derstandard.at/story/1389858536775/bankenabwicklung-weiter-offen.

- Der Standard. 2020. “Österreich, Niederlande, Schweden und Dänemark gegen Merkel-Macron-Plan.“ Der Standard, May 19, 2020. https://www.derstandard.de/story/2000117593256/oesterreich-niederlande-schweden-und-daenemark-gegen-merkel-macron-plan.

- Deutsche Bundesregierung. 2018a. “Erklärung von Meseberg Das Versprechen Europas für Sicherheit und Wohlstand erneuern.” Pressemitteilung 214, June 19. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/erklaerung-von-meseberg-1140536.

- Deutsche Bundesregierung. 2018b. “Vorschlag der österreichischen Ratspräsidentschaft für ein Hybrid-Modell bei der europäischen Einlagensicherung.” Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Dr. Florian Toncar, Christian Dürr, Frank Schäffler, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der FDP, Drucksache 19/4310.

- Die Grünen. 2019. “Wen würde unsere Zukunft wählen: Wahlprogramm Nationalratswahl 2019.” https://www.gruene.at/partei/programm/wahlprogramme/das-gruene-wahlprogramm-2019.pdf.

- Die Presse. 2016. “Kurz: Ende der Balkanroute ‘keine Überraschung’.” Die Presse, March 8. https://www.diepresse.com/4942107/kurz-ende-der-balkanroute-keine-uberraschung.

- Die Presse. 2018. “Eurozonenbudget: Österreich sieht offene Fragen.” Die Presse, June 20, 2018. https://www.diepresse.com/5450094/eurozonenbudget-osterreich-sieht-offene-fragen.

- Donnelly, Shawn. 2018. “Advocacy Coalitions and the Lack of Deposit Insurance in Banking Union.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (3): 210–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2017.1400437.

- EUCO. 2012. “Towards a Genuine Economic and Monetary Union.” Report by President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy, Brussels June 26.

- Eurobarometer (European Commission Eurobarometer Interactive; Accessed July 2, 2020). https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/index.

- Euronews. 2012. “Talks on European Banking Union End in Failure.” Euronews, December 4, 2012. https://www.euronews.com/2012/12/04/talks-on-european-banking-union-end-in-failure.

- European Commission. 2010. “Proposal for a Directive on Deposit Guarantee Schemes [Recast].” COM/2010/0368 final. July 12. Accessed February 2, 2017. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0368:FIN:EN:PDF.

- European Commission. 2015. “The Five President's Report: Completing Europe's Economic and Monetary Union.” June 22.

- European Council. 2018. Interinstitutional File:2017/0270 (COD). Brussels, November 23.

- European Council. 2020. Special meeting of the European Council (17, 18, 19, 20 and 21 July 2020) – Conclusions. CO EUR 8 CONCL 4, Brussels 21 July 2020.

- Eurostat (Eurostat database; Accessed July 2, 2020). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- Falkner, Gerda. 2001. “The Europeanisation of Austria: Misfit, Adaption and Controversies.” European Integration Online Papers 5 (13). http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2001-013a.htm.

- FPÖ. 2020. “FPÖ – Steger: Klares Nein zu einem 500 Milliarden Euro EU-Corona-Fonds.“ Presseaussendung OTS0014, May 21.

- Gocaj, Ledina, and Sophie Meunier. 2013. “Time Will Tell: The EFSF, the ESM, and the Euro Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 35 (3): 239–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774778.

- Hacker-Walton, Philipp, and Hermann Sileitsch-Parzer. 2013. “Wer soll bei Pleitebanken den Ton angeben?“ Kurier, July 9. https://kurier.at/wirtschaft/eu-kommission-wer-soll-bei-pleitebanken-den-ton-angeben/18.553.342.

- Heidebrecht, Sebastian. 2017. “Trying Not to Be Caught in the Act: Explaining European Central Bank’s Bounded Role in Shaping the European Banking Union.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 13 (2): 1125–1143.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2009. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409.

- Howarth, D., and L. Quaglia. 2014. “The Steep Road to European Banking Union.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52: 125–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12178.

- Howarth, David, and Lucia Quaglia. 2016. “Internationalised Banking, Alternative Banks and the Single Supervisory Mechanism.” West European Politics 39 (3): 438–461.

- Howarth, David, and Lucia Quaglia. 2018. “The Difficult Construction of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme: A Step too Far in Banking Union?” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (3): 190–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2017.1402682.

- Jones, Erik. 2021. “Hard to Follow: Small States and the Franco-German Relationship.” German Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2002300

- Kogelnik, Lisa, Marie-Theres Egyed, and Michael Völker. 2016. “Faymann-Nachfolger innerhalb einer Woche.” Der Standard, May 9. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000036594374/ein-schneller-ruecktritt-mit-langem-anlauf.

- Krotz, Ulrich, and Joachim Schild. 2013. Shaping Europe: France, Germany and Embedded Bilateralism from the Elysée Treaty to Twenty-First Century Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kurz, Sebastian. 2020. “The ‘Frugal Four’ Advocate a Responsible EU Budget.” Financial Times, February 16. https://www.ft.com/content/7faae690-4e65-11ea-95a0-43d18ec715f5.

- Laffan, Brigid, and Pierre Schlosser. 2016. “Public Finances in Europe: Fortifying EU Economic Governance in the Shadow of the Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 38 (3): 237–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140158.

- Lofven, Stefan. 2020. “‘Frugal Four’ Warn Pandemic Spending Must Be Responsible.” Financial Times, June 16. https://www.ft.com/content/7c47fa9d-6d54-4bde-a1da-2c407a52e471.

- Matthijs, Matthias, and Kathleen McNamara. 2015. “The Euro Crisis’ Theory Effect: Northern Saints, Southern Sinners, and the Demise of the Eurobond.” Journal of European Integration 37 (2): 229–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.990137.

- Murphy, Francois. 2020. “Austria Says EU ‘Frugals’ to Present Alternative to Franco-German Fund Plan.” Reuters, May 19. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-germany-eu-austria/austria-says-eu-frugals-to-present-alternative-to-franco-german-fund-plan-idUSKBN22V2HS.

- OECD data (OECD database; accessed July 2, 2020). https://data.oecd.org/.

- OÖN. 2020. “EU-Coronahilfen: Kogler für ‘direkte Zuschüsse’.“ Oberöstrreichische Nachrichten, May 24. https://www.nachrichten.at/politik/innenpolitik/eu-coronahilfen-kogler-fuer-direkte-zuschuesse;art385,3260582.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2011a. “BM Fekter: Helfen, reformieren, kontrollieren, sanktionieren EU-Ausschuss diskutiert über Europäischen Stabilitätsmechanismus.“ Aussendung der Parlamentskorrespondenz, OTS0327, November 11.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2011b. “Regierungsmehrheit verankert Schuldenbremse im Haushaltsrecht.“ Parlamentskorrespondenz No. 1204, December 7. https://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/PR/JAHR_2011/PK1204/#XXIV_I_01516.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2012a. “Hitzige Debatten zu ESM und Fiskalpakt.“ Hintergrundskorrespondenz zum 4. Juli. https://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/AKT/SCHLTHEM/SCHLAG/J2012/2012_07_04_ESM_Fiskalpakt.shtml.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2012b. “ESM und Fiskalpakt nehmen Hürden im Nationalrat.“ Parlamentskorrespondenz No. 587, July 4. https://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/PR/JAHR_2012/PK0587/index.shtml.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2014. “Entscheidung über die zentrale Bankenabwicklung noch vor EU-Wahlen?” Parlamentskorrespondenz No. 120, February 19. https://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/PR/JAHR_2014/PK0120/.

- Österreichischer Nationalrat. 2020. „Hauptausschuss debattiert über Aufbaufonds der EU zur Bewältigung der COVID-19-Folgen.“ Parlamentskorrespondenz No. 619. June 15. https://www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/PR/JAHR_2020/PK0619/.

- Rheindorf, Markus, and Ruth Wodak. 2018. “Borders, Fences, and Limits—Protecting Austria from Refugees: Metadiscursive Negotiation of Meaning in the Current Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 15–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1302032.

- Schild, Joachim. 2013. “Leadership in Hard Times: Germany, France, and the Management of the Eurozone Crisis.” German Politics and Society 31 (1): 24–47.

- Schild, Joachim. 2018. “Germany and France at Cross Purposes: The Case of Banking Union.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 21 (2): 102–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2017.1396900.

- Schimmelfennig, Frank. 2015. “Liberal Intergovernmentalism and the Euro Area Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (2): 177–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994020.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2018a. “Germany, the Problem of Leadership, and Institution-Building in EMU Reform.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform. Advance online publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2018.1541410.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2018b. “The Rise and Fall of Merkozy: Franco-German Bilateralism as a Negotiation Strategy in Eurozone Crisis Management.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (5): 1019–1035. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12704.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2019. Leadership in the Eurozone: The Role of Germany and EU Institutions. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2020a. “Free Riders, Allies or Veto Players? Preferences and Strategies of Smaller Creditor States in the Euro Area.” EIF Working Paper No. 02/2020, Vienna: Centre for European Integration Research.

- Schoeller, Magnus G. 2020b. “Preventing the Eurozone Budget: Issue Replacement and Small State Influence in EMU.” Journal of European Public Policy. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1795226.

- Schoeller, Magnus G., and Gerda Falkner. 2021. “Acting in the Shadow of German Hegemony? The Role of Smaller States in the Economic and Monetary Union (Introduction to the Special Issue).” German Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2005028

- Scholz, Olaf. 2019. “Germany Will Consider EU-Wide Bank Deposit Reinsurance.” Financial Times, November 5. https://www.ft.com/content/82624c98-ff14-11e9-a530-16c6c29e70ca.

- Schult, Christian. 2012. “‘Nichts versprechen‘: Der sozialdemokratische österreichische Bundeskanzler Werner Faymann, 51, über größere Rettungsschirme, mehr Kredite für Griechenland und die deutsche Krisenpolitik. Der Spiegel, January 30. https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-83774675.html.

- SN. 2020. “Kogler distanziert sich von Kurz-Linie beim EU-Gipfel.“ Salzburger Nachrichten, July 23. https://www.sn.at/politik/innenpolitik/kogler-distanziert-sich-von-kurz-linie-beim-eu-gipfel-90548371.

- Statistik Austria. 2020. „Bevölkerung zu Jahresbeginn 2002-2020 nach detaillierter Staatsangehörigkeit.“ https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstruktur/bevoelkerung_nach_staatsangehoerigkeit_geburtsland/index.html.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2020a. „Ausländische Bevölkerung nach Geschlecht und ausgewählten Staatsangehörigkeiten am 31.12.2019.“ https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Tabellen/auslaendische-bevoelkerung-geschlecht.html.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2020b. “Rangfolge der Handelspartner im Außenhandel der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.“ https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Wirtschaft/Aussenhandel/Tabellen/rangfolge-handelspartner.html.

- Verdun, Amy. 2021. “The Greatest of the Small? The Netherlands and the New Hanseatic League.” German Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.2003782

- Vytiska, Herbert. 2015. “Faymann bei Tspiras: Zwischen Vermittlungsversuch und Höflichkeitsbesuch.“ Euractiv, June 18. https://www.euractiv.de/section/osterreich/opinion/faymann-bei-tspiras-zwischen-vermittlungsversuch-und-hoflichkeitsbesuch/.

- Wirtschaftskammer Österreich. 2020a. “Österreichs Außenhandel 1980–2019: Wichtigste Handelspartner Vorläufige Ergebnisse März 2020.”

- Wirtschaftskammer Österreich. 2020b. „Tourismus und Freizeitwirtschaft in Zahlen: Österreichische und internationale Tourismus- und Wirtschaftsdaten 56.“ Ausgabe April 2020.

Interviews

- Interview AT1. 2019. Senior government official, Federal Ministry of Finance (Austria), 30 January, Vienna, Austria.

- Interview BRU4. 2018. Seconded national expert, European Commission, DG FISMA, 30 October, Brussels, Belgium.

- Interview DE1. 2019. Senior government official, Federal Ministry of Finance (Germany), 15 November, phone interview.

- Interview EX1. 2018. Former senior EU official, Council of the European Union, 24 September, Vienna, Austria.