Abstract

This paper studies party-movement interactions in Germany, focusing on Die Linke and the AfD, the two most recent additions to Germany’s multi-party system. The electoral rise of both challenger parties went along with mass protests, opposition to Hartz IV in the mid-2000s and anti-Islamic PEGIDA mobilisation in the mid-2010s. We shift the emphasis from how social movements turn into political parties, including significant organisational and personal overlap, to more indirect ways of how protest and electoral politics interact. Specifically, we identify a process composed of two interrelated mechanisms: an external politicisation spiral and an intra-party innovation spiral. We show how mass protest triggers both discursive shifts in the public sphere and internal strategic realignment, providing an opportunity for parties to ride the wave, secure their competitive advantages, and mobilise on the protestors’ grievances in the electoral arena. In such a way, challenger parties can take advantage of street protests even when they do not directly emerge from a movement. Methodologically, the article is based on a paired comparison, relying on survey data and an original protest event analysis that provides novel data on anti-Hartz IV and PEGIDA protest mobilisation in Germany.

Introduction

How do social movement and protest dynamics contribute to the electoral breakthrough of challenger parties? The classic notion of ‘the long march of movements through the institutions’ directly touches upon the relationship between the protest and the electoral arena. The typical modern example for such a march – or institutionalisation process – is the Greens. Across Western Europe, Green parties emerged from the environmental movement and related new social movements in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g. Dalton and Kuechler Citation1990; Kitschelt Citation1989; Müller-Rommel Citation1989). As McAdam and Tarrow (Citation2010) aptly stated, after these heydays of party-movement interactions, electoral and party research has neglected the importance of social movements and protest for understanding transformations in party competition. However, since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 and particularly in the context of the anti-austerity movements in Southern Europe, party-movement interactions have re-emerged as a central theme in public and scholarly debates (e.g. Bremer et al. Citation2020; Borbáth and Hutter Citation2021; Caiani and Císař Citation2019; Castelli Gattinara and Pirro Citation2019; della Porta et al. Citation2017). In Spain, for example, leading figures of the 15-M movement were involved in the founding of the new challenger party Podemos (Chironi and Fittipaldi Citation2017; de Nadal Citation2021; Portos Citation2021). These historical and recent examples share that mass protests were followed by party formation, with significant organisational and personal overlap between protestors and party founders.

In this paper, we assess how social movement and protest dynamics have contributed to establishing the two most recent newcomers in Germany’s multi-party system, Die Linke (The Left) and the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD; Alternative for Germany). In contrast to the typical examples listed above, we focus on two challenger parties that already existed when party-movement interactions kicked in. Still, their electoral breakthrough was preceded by mass protests focusing on a grievance that corresponded to the parties’ core issue: starting in 2004, anti-Hartz IV protest targeted welfare state retrenchment. Starting in 2014, PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the Occident) mobilised mainly against Muslim immigration and multiculturalism more generally. This observation points to the need to (a) link research on the German party system with social movement studies and (b) further specify the processes through which protest and electoral politics relate to each other, in line with the goals of this special issue (see Hutter and Weisskircher Citation2022).

More than three decades ago, the rise of the German Greens led scholars of the German party system to pay close attention to movement-party interactions.Footnote1 More recent literature on Die Linke (e.g. Hough et al. Citation2007; Olsen Citation2007; Spier et al. Citation2007) and AfD (e.g. Art Citation2018; Arzheimer Citation2019), however, tends to neglect the importance of protest mobilisation for these party’s electoral rise. So far, Patton (Citation2017) has explored the link between movement activism and the rise of Die Linke and the AfD most systematically, highlighting the role of eastern Germany as a breeding-ground for changes to the German-wide party system. We go beyond a descriptive account by proposing an innovative and generalisable theoretical conceptualisation. We also connect to international debates on party-movement interactions by providing systematic and novel empirical evidence for the processes at work.

More precisely, our paper contributes in three ways to scholarly debates over party-movement interactions and German politics: Theoretically, we go beyond the ‘standard model’ of party-movement interactions and its focus on a fairly direct relationship between the protest and electoral arena. Instead, we propose a process of two inter-related mechanisms that more indirectly link the streets with the electoral breakthrough of a challenger party. On the one hand, movement emergence may trigger an external politicisation spiral, amplifying the salience and polarisation of an issue in public discourse. On the other hand, movement emergence may trigger an intra-party innovation spiral, contributing to a strategic shift of the emerging challenger party. Ultimately, both dynamics contribute to the party’s electoral breakthrough.

Secondly, we contribute empirically to explaining the emergence of the two latest additions to Germany’s now six-party system by highlighting the importance of street protest. Finally, the article is based on a methodological paired comparison, relying on survey data and an original protest event analysis that provides novel data on anti-Hartz IV and PEGIDA protest mobilisation.

The paper is structured in four parts. First, we summarise key features of recent scholarship on party-movement interactions. Based on this review, we introduce two mechanisms linking movement and protest politics to the electoral breakthrough of challenger parties, even in the absence of substantial organisational and personal overlaps. Second, we introduce our design and methods. Third, we apply our theoretical framework in our case studies on Die Linke and the AfD. In the concluding section, we discuss the implications of our findings for understanding political conflict in and beyond Germany.

Party-Movement Interactions: System- and Organisation-Centered Perspectives

Before focusing on their interactions, we start by defining political parties and social movements. Taking the minimal definition of Sartori (Citation1976, 64), a party is ‘any political group that presents at elections, and is capable of placing through elections, candidates for public office’. Parties take part in elections, where they compete with other parties. In addition, we adopt de Vries and Hobolt’s (Citation2020) notion of challenger parties as parties without government experience. These parties often aim to disrupt the status quo by raising new issues and positioning themselves against the mainstream. While social movements may share the ambition of challenger parties, as organisational forms they are often understood as ‘networks of informal interaction between a plurality of individuals, groups and/or organisations, engaged in a political and/or cultural conflict, on the basis of a shared collective identity’ (Diani Citation1992, 3). Although the conceptual boundaries between parties and social movements are fuzzy and permeable (Burstein Citation1999), parties are closer to institutionalised politics than protestors (Goldstone Citation2003), a fact that shapes their complex relations.

Taking up Doug McAdam and Sidney Tarrow’s (Citation2010) powerful call made a decade ago, scholars have recently returned to study the manifold interactions between movement and electoral dynamics. In our understanding, the literature has taken two broad perspectives to conceptualise these interactions (for a review: Hutter et al. Citation2019). The first perspective focuses on the systemic level and understands party-movement interactions as a loose set of relationships where weak ties link and influence the electoral and the protest arenas. The second perspective zooms in on the organisational level. Scholars who adopt such a perspective are interested in how more tightly coupled interactions between parties and movements may lead to organisational innovation and transformation. We label the first school of thought system-centred, the second organisation-centred. In what follows, we sketch the main ideas of both perspectives before we discuss how we integrate them to understand better how the processes unfold through which movement emergence may trigger the electoral breakthrough of challenger parties.

Within the system-centred perspective, we distinguish between the political process, cleavage, and agenda-setting approaches. The political process approach in social movement studies (e.g. McAdam Citation1982; Tarrow Citation1989; Kriesi et al. Citation1995) identifies parties as potential elite allies or adversaries of movements with the power to amplify or silence the issues advocated by movements through controlling the institutional channels of politics. Most importantly, scholars in this tradition considered the type of party system and the government participation of likely allies as key variables. Kriesi et al. (Citation1995), for example, showed how the left in opposition facilitated protest mobilisation by the new social movements in the 1970s and early 1980s. The cleavage approach focuses on the long-term ebb-and-flow of the core issues associated with cleavage transformation and examines how the political left and the right mobilise them across political arenas. Importantly, this strand of the literature has shown that, in Western Europe, the left tends to rise and decline in the electoral and protest arenas simultaneously, whereas the (far) right favours the electoral arena and only mobilises forcefully in the protest arena when it did not yet gain a foothold in electoral politics (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2013; Hutter and Borbáth Citation2019). The agenda-setting approach, by contrast, focuses on protests as a more short-term signalling device for public opinion to raise the salience of a particular issue, shifting the agenda of institutionalised politics (e.g. Jennings and Saunders Citation2019; Walgrave and Vliegenthart Citation2012; Vliegenthart et al. Citation2016). The climate strikes by Fridays for Future, for example, have been widely regarded as having had such an impact on parties’ agendas (Berker and Pollex Citation2021). Overall, the system-centred perspective interprets party-movement interactions in the broader framework of the relationship between the protest and the electoral arenas, focusing on aggregate and programmatic effects.

Within the organisation-centred perspective, we distinguish between the contentious politics and ‘movement party’ approaches. Following the contentious politics approach, party-movement interactions contribute to electoral polarisation. They strengthen the influence of an activist base over the party leadership, leading to ideological radicalisation of established parties captured by movement logics. For example, McAdam and Kloos (Citation2014) describe how pressure from movement activists led to the radicalisation of both the U.S. Democrats and the Republicans from the civil rights movements in the 1960s onwards. Thus, the latest developments during the Trump administration (Meyer and Tarrow Citation2018) mirror previous episodes of movement-induced party polarisation. According to the ‘movement party’ approach, the nexus between protest and electoral politics happens when social movements become political parties but still maintain movement-like features. That is, such movement parties focus on a selective set of issues, invest little in strong organisations, and rely heavily on protest mobilisation (Kitschelt Citation2006). Being a movement party has been conceptualised as a phase of party development at the beginning of the lifecycle of political parties, such as in case of the Green party family (Kitschelt Citation1989). Recent research, however, has investigated to what extent movement party features may constitute more permanent features of left-wing (della Porta et al. Citation2017) and far-right political parties (Caiani and Císař Citation2019; Castelli Gattinara and Pirro Citation2019). For example, the Hungarian Jobbik has reduced its involvement in street activism only during its moderation process (Pirro et al. Citation2021). Overall, the organisation-centred perspective formulates a more demanding concept of party-movement interactions than the system-centred perspective as interactions with movements are expected to contribute to the organisational development and innovation of parties.

To understand the processes at work when challenger parties already exist and profit from movement and protest dynamics, we suggest combining the two perspectives. On the one hand, our discussion of the scholarly literature indicates that narrowly understood organisational transformations, where a new party builds on a preceding movement by harnessing its organisational and personal resources, only represent a specific and highly demanding view of party-movement interactions. However, such an organisation-centred perspective points to organisational hybridity and substantial overlaps in support base and leadership of movements and parties, which may strongly influence the trajectories of both. On the other hand, the system-centred perspective suggests how developments in the protest arena and the electoral arena may strongly affect each other above and beyond the organisational level, most importantly, through shifts in public attention to the issues and demands at stake.

We draw on insights from the two perspectives and adopt the focus on mechanisms and processes from the contentious politics framework (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Citation2001). Therefore, we understand mechanisms as ‘a delimited class of events that alter relations among specified sets of elements in identical or closely similar ways over a variety of situation’ (ibid.: 24). The goal is not to propose causal laws about when protest leads to electoral breakthrough, but to ‘single out relatively common processes (combinations and sequences of mechanisms) for closer study, comparing episodes and families of episodes to detect how those processes operate’ (ibid.: 84). Innovatively, these mechanisms link protest to the electoral breakthrough of challenger parties, even when they do not harness organisational and personal resources of the corresponding movement (for an overview, see ):

Table 1. A process of protest-initiated opportunity spirals for an electoral breakthrough.

The first mechanism – the external politicisation spiral – follows the emphasis on programmatic and discursive shifts from the system-centred approach. Here, we stress the importance of discursive ‘opportunity-spirals’ (Karapin Citation2011) set in motion by initial protest mobilisation, underlining that discursive contexts may contribute to the success of specific forms of collective action (Koopmans and Olzak Citation2004; McCammon et al. Citation2007). Notably, research has shown that movements may be critical in shaping discursive fields and politicising an issue (Gaby and Caren Citation2016; see also Gheyle and Rone Citation2022 in this special issue). In turn, the electoral success of political parties may be boosted by favourable discursive opportunity structures (Koopmans and Muis Citation2009). Thus, protestors may open-up discursive opportunity structures through triggering and decisively shaping public debates – particularly useful for a challenger party with a credible claim for issue ownership.

The second mechanism – the intra-party innovation spiral – follows the organisation-centred perspective and zooms in on party-internal processes (e.g. Close and Gherghina Citation2019). Given the ideological proximity to the movement and increasing visibility of its claims in public debates, the emerging challenger party can hardly opt to ignore what is happening on the streets. As research shows, challenger parties are more responsive to concerns of their support base in their core issue areas (e.g. Spoon and Klüver Citation2014) and to protest politics (Hutter and Vliegenthart Citation2018) than their mainstream competitors. After initial protest mobilisation, party politicians start to develop ambivalent relations with protestors, ranging from cooperation to competition. These intra-party dynamics triggered by the streets may cause a strategic realignment within the challenger party, boosting efforts to align with movement claims.

Ultimately, it will depend on the outcome of both dynamics (external and party-internal) to what extent mass protest contributes to the electoral breakthrough of a challenger party. As highlighted, mass protest may trigger both discursive shifts in the public sphere and internal strategic decisions, which may involve power struggles, providing an opportunity for parties to ride the wave, secure their competitive advantages, and mobilise on the protestors’ grievance in the electoral arena. However, seising this opportunity is most likely when the external politicisation spiral and the intra-party innovation spiral result in reinforcing the issue ownership (Petrocik Citation1996) of the challenger party, i.e. amplifying its public and internal association with a certain stance. In such an ideal-typical process, a challenger party can take electoral advantage of street protests, even without strong organisational and personal overlap.

Design and Methods

We apply this perspective to understand the relationships between anti-Hartz IV protests and Die Linke as well as PEGIDA and AfD, political forces on the opposite side of the political spectrum and emerging at different moment in time, which both benefited from very similar party-movement interactions. We pursue a paired comparison, exploiting its advantage for theory generation through the in-depth analysis of processes that link causes to outcomes (Tarrow Citation2010). The aim is ‘not to maximise resemblance or even to pinpoint differences […], but to discover whether similar mechanisms and processes drive “changes” (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Citation2001, 82).

We collected original protest event data on anti-Hartz IV and PEGIDA mobilisation. Our conception of a protest event is encompassing and operational: we surveyed all politically motivated, ‘unconventional’ actions. Thereby, we do not rely on a precise definition but a detailed list of types of unconventional or protest-like activities (see Kriesi et al. Citation1995). Furthermore, there is no required minimum number of participants. We analysed the coverage of the Die Tageszeitung, a left-wing national newspaper that regularly covers protest on the left and the right. For PEGIDA, we supplemented this national newspaper with the regional newspaper Sächsische Zeitung, published in Dresden, where the group emerged and mobilised most strongly. We identified relevant articles for the manual coding with a set of keywords referring to different forms of protest and Hartz IV and PEGIDA, respectively. In the case of anti-Hartz IV mobilisation, we coded events from the beginning of these protests in July 2004 until the end of 2005. In the case of PEGIDA, we started with the first protest in October 2014 and coded them until the end of 2015.

We complement the dataset with two additional sources. Firstly, to study shifts in public opinion, we analyse the Politbarometer monthly surveys, collected since 1977. We rely on two questions. The first item asks the respondents to identify the most important problem facing Germany. The second item asks respondents whom they would vote for if the parliamentary elections were next Sunday. We recoded the most important problems to identify the ones related to Hartz IV and the issues contested by PEGIDA.Footnote2 Secondly, to study shifts in the press and public party-movement associations, we analyse the coverage of one of the largest daily national newspapers, the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Using a dictionary approach, we identify articles that mention the movement associated with the issue and articles that mention both the movement and the party.Footnote3 We then use the monthly share of the coded documents as our measure of issue attention in the press.

For our qualitative analysis, we rely on secondary literature on the respective movements and parties, newspaper coverage, and primary material, i.e. publications by party and protest actors. Our focus is on the organisation of the protests, the career paths of key movement activists and party politicians involved, and how party actors responded to street mobilisation.

Empirical Analysis

Anti-Hartz IV Protest and the Rise of Die Linke

For a long time, the Federal Republic of Germany was among the few western European countries without an established radical left party. This situation did not change in the 1990s, after Wiedervereinigung, when the successor party of the Communist SED (Socialist Unity Party) failed to make inroads in the west: The PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism) remained an eastern phenomenon only, with sizable electoral support there. Koß (Citation2007) emphasises three explanatory factors for the failure of PDS to expand in the west. First, the party had only little incentive to organise in the west at the first joint Bundestag election in 1990: A special rule guaranteed that meeting the five percent threshold only in the east was enough to enter the Bundestag. Second, it was mainly radical leftists who became active for the party in the west, proving unable to have some broader appeal within the electorate. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the western branches of PDS always suffered from the stigma of being the SED successor. In short, in the decade before the anti-Hartz IV demonstrations, PDS remained an eastern German force only. In 2002, it ended up with only four percent of the vote in all of Germany, substantially below the five percent threshold (gaining merely two seats through direct mandates). The gloomy prospects for the radical left in Germany changed only in the following years, after the rise of the anti-Hartz IV protest.

2004 marked the beginning of a change of fortunes. The bone of contention was the Hartz IV reforms by the Red-Green government (Schröder II), substantially reducing and shortening unemployment benefits. The policy was part of the Red-Green Agenda 2010, which deregulated the German labour market. The legislation was a gamechanger in German party competition, contributing to the long-term electoral decline of the social-democratic party and changing coalition dynamics (Dostal Citation2017; Schwander and Manow Citation2017). Before that, however, controversy surrounding the policy had already shaped the protest arena – when the issue was not yet addressed in the arena of party politics.

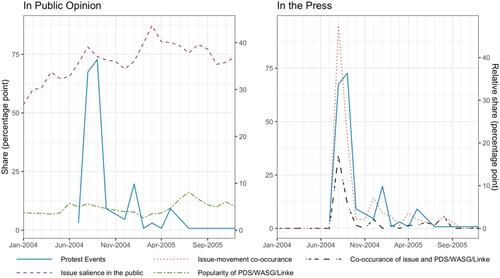

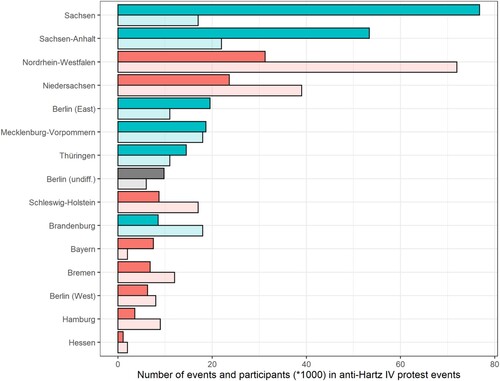

Starting in the early summer of 2004, anti-Hartz IV protests emerged in several German cities, quickly diffused, and soon attracted broader support.Footnote4 shows the distribution of protest events and the number of participants by federal states. The figure underlines the large variation in mobilisation across Germany. Given the poor shape of eastern Germany’s economy after the difficult transformation of the 1990s, it is not surprising that movement emergence occurred there. Eastern Germany was also where anti-Hartz IV protests were most attended. Protest only later diffused to the west, on a smaller scale only. On August 30, 2004, protests reached their climax, with events in more than 200 cities with at least 200,000 in total. In the second half of 2004, protests sharply declined. Still, some important events took place: on October 2, 2004, the protestors went to the central stage of German politics, with 50,000 protestors in Berlin; a day later still mobilising 25,000 supporters at Alexanderplatz. Overall, the east is clearly overrepresented: the absolute number of demonstrators was about four times as high as in the west even though only about 15 percent of the German population lived there.

Figure 1. Anti-Hartz IV mobilisation across Germany. Note: The colour distinguishes eastern and western federal states. Darker colours indicate the number of participants divided by 1000, lighter colours show the number of protest events.

Who was organising the anti-Hartz IV protests? For the protests’ early stages, the initiative came from private, sometimes unemployed individuals and soon from far-leftist circles such as the Marxist–Leninist Party of Germany (MLPD). Other organisations joined in, e.g. various associations of the unemployed or sections of trade unions, which are generally less organised in the east. Other organisations involved were the so-called Forum für Arbeit und soziale Gerechtigkeit (Forum for Labour and Social Justice) and Sozialforum (Social Forum). Attac was also involved and important for the spread of the protests in western Germany. Interestingly, trade unions were divided over the question of whether to support the protests. On the grassroots level, many local chapters joined. However, national trade union leaders were more skeptical: Michael Sommer, then DGB-head and SPD member, warned about the danger of extremists and anti-democrats in charge of the demonstrations (Rein 2004: 606f). While PDS was usually not among the sponsors, the party was nevertheless present (Rink and Philipps Citation2007, 56). Moreover, and importantly, protest participants supported the PDS. In on-site protest surveys on September 13, 2008, at demonstrations in Berlin, Dortmund, Leipzig, and Magdeburg, the PDS was supported by 33% (west) respectively 49% (east) of respondents (Rucht and Yang Citation2004).Footnote5

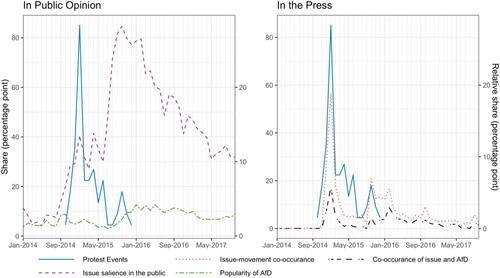

The protests against Hartz IV created a stir, causing what we call an external politicisation spiral. To illustrate the dynamic, shows the development of the number of anti-Hartz-IV protest events along with public and media attention for social issues, as well as the popularity of PDS in the polls. The data indicate that the anti-Hartz IV protests pre-empted a shift in the discursive climate. Although the social issues associated with the protests are regularly among the most important problems that citizens name, we observe a substantial increase in their salience following the protest wave. In January and February of 2004, 53 respectively 60 percent of respondents listed social issues among the most important problems. From April onwards, the value was constantly higher, peaking at 78 percent in August. At the end of 2004, 70 percent of respondents listed social issues among the most important problems. In March 2015, their share reached a peak of 87 percent. Following the anti-Hartz IV mobilisation, we also observe an increase in the national popularity of PDS: from 9 percent in May 2005 to 16 percent in July 2005. The right-hand panel shows that attention to the movement and the movement’s issue in the press have been rising at the same time as protest mobilisation peaked. A substantial part of the coverage of Hartz IV is associated with PDS and the trade unions. The association between the two peaks at the same time as does the protest mobilisation. The temporal sequence in the discursive climate suggests that these increases were related to the protest wave peaking in the late summer of 2004.

Crucially, the anti-Hartz IV protest also triggered an intra-party innovation spiral with lasting consequences for Germany’s radical left. Again, note that the PDS was not behind the initiation of the protests. However, it soon started to ride the wave. On the one hand, key representatives stated that they wanted to remain cautious and did not aim to be at the forefront of the demonstrations (e.g. Neues Deutschland, Citation18.04.2004). On the other hand, the party quickly took advantage of bottom-up mobilisation. Ahead of the upcoming regional elections in Brandenburg and Saxony, many PDS politicians expressed their support for the protests or even acted as guest speakers. Prominent speakers included Gregor Gysi and Brandenburg top candidate Dagmar Enkelmann (see ). Even in Berlin, where PDS was under critique for its role in implementing the federal Hartz IV laws in regional government with SPD, the party representatives expressed solidarity with the anti-Hartz IV protest.Footnote6 Ahead of the regional elections, PDS made opposition to Hartz IV its most prominent cause: With reference to the protests, PDS federal chairman Lothar Bisky underlined that ‘we are part of the indignation’ (Neues Deutschland, Citation24.08.2004). Ultimately, the party could celebrate record results in both Brandenburg and Saxony. In Brandenburg, the SPD started exploratory coalition talks with the PDS. However, the PDS soon withdrew, justifying its decision with strong disagreement over Hartz IV (Neues Deutschland, Citation24.09.2004).

Table 2. Key politicians for Die Linke‘s emergence.

Apart from PDS, also other left-wing actors crucial for the formation of ‘PDS. Die Linke’ rode the wave of the Monday demonstrations. Most prominently, Germany’s former finance minister Oskar Lafontaine, then still a member of SPD, gave a speech at a demonstration in Leipzig, criticising his party-in-government for introducing Hartz IV (see ).Footnote7 Importantly, also activists of WASG (Arbeit und soziale Gerechtigkeit – die Wahlalternative; Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative) soon started to (co)-organise Monday demonstrations in the west and also gave speeches at Monday demonstrations in the east. WASG was a ‘heterogenous group of disillusioned SPD members, union leaders, and left-wing intellectuals and peace activists’ (Olsen Citation2007, 208) that had already formed in the first half of 2004, before the emergence of the Monday demonstrations, and which aimed for a fundamental change of the direction of socioeconomic policies in Germany.Footnote8 WASG activists have emphasised the importance of their involvement in the Monday demonstrations in the west, especially in industrial North Rhine-Westphalia (e.g. taz, Citation01.Citation08.Citation2005).

WASG’s transformation from an association into a party was also driven by the street protests. As a report by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (Citation2012: Xf, our translation) highlighted: ‘Supported by the ongoing wave of protests against the ‘Agenda‘ policy (especially in the form of the Monday demonstrations) on the one hand and high poll numbers in the so-called Sunday question on the other, the WASG leadership aimed at party formation’. In January 2005, WASG was established as party.

Most importantly for our argument, the dynamics around the anti-Hartz IV protests provided incentives for both PDS and WASG to cooperate in the electoral arena, underlining the potential of a nationally unified party left of SPD. Even before WASG’s official registration as party, Gregor Gysi spoke in favour of cooperation at the PDS party conference in October 2004. In March 2005, the first formal talks between PDS and WASG representatives took place. Ultimately, the North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) regional election in May 2005 turned out to be a crucial event. Both parties did not perform well on their own: WASG gained 2.2 percent of the vote, while the PDS only attracted 0.9 percent (even 0.2 less than in the previous election). At the same time, SPD was the main electoral loser on that day and, right after its loss in one of its traditional strongholds, the party called for snap elections for the Bundestag. Now everyone had to move fast: Oskar Lafontaine announced his intention to leave the SPD, offering to run as lead candidate should WASG and PDS cooperate. In July 2005, a WASG party conference voted for a common list of WASG and PDS in the federal elections.Footnote9 At that conference, Lafontaine referred to the established parties as ‘Hartz-IV parties’ (FAZ, Citation03.Citation07.Citation2005), presenting opposition to the policy as the unique selling point of the new formation.

Mobilising so staunchly against Hartz IV was crucial for the new platforms’ electoral breakthrough. In September 2005, ‘PDS. Die Linke’ received 8.7% in the federal election. It managed to do so without participation of leading anti-Hartz protest activists, especially not in the east, where the PDS could ride the wave. At the organisational level, the anti-Hartz IV activists never had the strength to enter the electoral arena. At the individual level, key eastern activists kept their distance to the new party project. Perhaps the most prominent ‘Monday demonstrator’ ultimately entering the arena of party politics was from the west: Trade unionist Bernd Riexinger from Baden-Württemberg, who even became the party’s co-chairman in 2012 ().

Table 3. Key anti-Hartz-IV activists.

The formation of PDS. Die Linke was also followed by movement decline. Over the course of the electoral campaign year 2005, the number of protest events, and even more the number of participants, sharply shrank (see ). In the following years, it was mostly rare Berlin-based protests against Hartz IV that could attract large number of protests, such as in June 2006 with over 10,000 supporters – an event organised by a large coalition of radical left and unemployment organisations. However, like the established trade unions, also ‘PDS. Die Linke’ was hardly involved, especially not at the leadership level. Outside of Berlin, the situation looked even direr, with occasional demonstrations of a few dozen against Hartz IV in cities such as Magdeburg and Leipzig, as in November 2006. The new radical left party channelled the dismay over Hartz IV into the electoral arena.

PEGIDA and the Rise of Alternative für Deutschland

The case of AfD-PEGIDA interaction illustrates the process of protest-initiated opportunity spirals for an electoral breakthrough even more strikingly. Germany was also long-known for not having a far-right party in national parliament (Backes and Mudde Citation2000). Before the rise of AfD, such parties always remained subnational and short-lived phenomena (Decker Citation2000). While the foundation of AfD in 2013 preceded the emergence of PEGIDA a year later, it is well-established that AfD did not start out as ‘populist’ radical right party – in its early days, neoliberal critics of the Eurozone, mainly based in western Germany, were dominant, with radical right politicians in secondary roles only. In its electoral manifesto of 2013, AfD’s positions on immigration were ‘not overly restrictive by German standards and […] [did] not display any nativist tendencies’ (Arzheimer Citation2015, 546). With this agenda, the party narrowly failed to enter the Bundestag in 2013 (4,7 percent). In the following years, however, the mobilisation success of PEGIDA contributed to the transformation of AfD into a typical anti-immigration party, which laid the ground for the latter’s electoral breakthrough in 2017.

The context of international migration is crucial for understanding the rise of anti-immigrant actors in German politics. The early 2010s saw a significant annual growth in the number of asylum-seekers: numbers quadrupled from 2010 to 2014. Locally, far-right protest groups against immigration quickly appeared – and quickly faded away. Similarly, no established party made opposition to immigration a central part of their platform. CDU has instead developed increasingly liberal stances over time. Before PEGIDA emerged, no anti-immigration player had a comparable influence in shaping the national debate. Like a decade earlier with protest against Hartz IV, PEGIDA mobilised on an issue which was not as strongly addressed by the Bundestag parties.

PEGIDA’s movement emergence occurred in October 2014. Unlike AfD, opposition to immigration was at its core from the very beginning. The group was established in Dresden, Saxony, by individuals linked to the local sports and party scene. Its leading figure, Lutz Bachmann, has a criminal record, but also volunteered when Dresden faced a flood in 2013 (on key activists, see ). While PEGIDA was first founded as a Facebook group, it quickly proceeded to protest on the streets. Apart from opposition to Muslim immigration, criticism of political elites and mainstream media were key issues put forward. In Dresden, participation in PEGIDA protests skyrocketed in December 2014 and January 2015, with up to 20,000 sympathisers present. Afterwards, numbers declined, but especially from September 2015 to the following winter, and also in exceptional cases afterwards, PEGIDA could still mobilise several thousand followers (for a detailed analysis of PEGIDA, see Vorländer, Herold, and Schäller Citation2018).Footnote10 Importantly, in protest surveys, a vast majority of PEGIDA demonstrators stated their support for AfD (e.g. 89 percent according to Daphi Citation2015). Likewise, the Facebook audiences of PEGIDA and AfD have been found to be quite similar (Stier et al. Citation2017). Given the overlapping audiences, it is unsurprising that the PEGIDA protests left their mark on the trajectory of the AfD.

Table 4. Key PEGIDA activists.

Despite being mainly active on the local level, PEGIDA shaped nationwide debates, initiating what we call an external politicisation spiral. As indicates, the rise of PEGIDA at the end of 2014 goes along with a substantial increase in the public and media interest in the issues associated with the protestors. The peak of the PEGIDA protests in the winter of 2014/15 went along with the first peak of public and media salience. The issues contested by PEGIDA remained on the public agenda throughout the first half 2015, when radical right factions inside AfD became ever more powerful: In June 2015 30 percent of respondents listed the issues contested by PEGIDA among the most important problems. By October, after AfD’s transformation and the intensification of the ‘refugee crisis’, their share rose to 85 percent. Similarly, the AfD’s popularity also increased. In June 2015 the party was measured with 4 percent popularity which increase to 9.5 percent by October 2015. PEGIDA’s framing of issues concerning immigration and integration arguably played an important part. As the right-hand side panel shows, when PEGIDA’s mobilisation peaks, the association between the group and the AfD in the press also peaks.

Soon after PEGIDA’s emergence, the ambivalent relationship between PEGIDA and AfD (Weisskircher and Berntzen Citation2019) led to an intra-party innovation spiral, strongly influencing the trajectory of AfD. The party itself played even less of a role for the development of PEGIDA protests than PDS did for street opposition to Hartz IV: While a local AfD member provided PEGIDA with some resources in its early stage, AfD was not involved in the establishment or breakthrough of the protest group. If some of the key figures of AfD’s radical right turn were involved in PEGIDA, then mostly as external special attractions (see ). Importantly, though, while the western German economic liberals still dominating the party remained rejective, some AfD politicians expressed sympathies from the very beginning, especially for the issues addressed, less so for leading figure Bachmann. Co-founder Alexander Gauland, born in Saxony, was one of the first key AfD figures attending a PEGIDA event – in the audience, not on stage. Afterwards, he spoke in support of PEGIDA’s goals and denied having witnessed xenophobia (Der Spiegel, Citation19.Citation12.Citation2014). After a January 2015 meeting between PEGIDA organisers and AfD Saxony, spokesperson Frauke Petry, the key face behind the party’s radical right turn in the summer of 2015, referred to ‘obviously substantial overlaps’ between the party and PEGIDA, for example on migration and direct democracy (FAZ, Citation08.Citation01.Citation2015) – even though she remained skeptical of the PEGIDA organisers. The members of the party’s then radical right faction ‘Patriotic Platform’ (Patriotische Plattform) strongly supported PEGIDA, with its founder Hans-Thomas Tillschneider as regular attendant.

Table 5. Key politicians for AfD’s radical right turn.

In the following months, AfD’s radical right faction pushed for a sharp turn to the right and a focus on anti-immigration stances. In March 2015, leading eastern AfD politicians, first and foremost Björn Höcke, formed the far-right ‘The Wing’ (Der Flügel) inside the party. In its Erfurt Resolution, it criticised the AfD party leadership for ‘keeping away and, in anticipatory obedience, even distancing, itself from bourgeois protest movements even though thousands of AfD members participate in these upheavals as co-demonstrators or sympathisers’ (Der Flügel Citation2015). Also the supporters of the neoliberal Eurozone critics underlined the importance of PEGIDA: Asked in an interview whether Gauland was ‘dividing’ the party, Lucke friend Bernd Kölmel described the protests as turning point:

‘As a result, yes. The crossroads began for us with PEGIDA and Mr. Gauland’s statement that we were natural allies of this movement. For the first time it became clear that there were significant differences in our understanding of politics.’ (FAZ, Citation28.Citation06.Citation2015).

The transformation of AfD into a member of the ‘populist radical right’ family in western Europe (Arzheimer Citation2019) was crucial for its electoral breakthrough. With AfD successfully adopting PEGIDA’s anti-immigration rhetoric, it was in a perfect position to benefit from the ‘refugee crisis’. Its opposition to the German government’s ‘welcome culture’ went unchallenged inside the party. Unlike 2013, AfD finally entered the German Bundestag in September 2017 – as biggest oppositional party. It managed to do so without participation of leading PEGIDA figures. At the organisational level, it never had the strength to do so. At the individual level, key activists remained uninvolved, either staying loyal to PEGIDA or ending up in other far-right circles (see ).

Since then, AfD is Germany’s far-right main event. Its rise has gone along with PEGIDA’s movement decline, even though PEGIDA itself experienced a second wave over the course of the ‘refugee crisis’. The group is now mainly noteworthy because of its longevity at the local level in Dresden (Volk Citation2021). Elsewhere, such as in some Bavarian cities, there are very small instances of mobilisation efforts that still makes use of the PEGIDA label. Importantly, by now, the radical right forces inside AfD and what is left of PEGIDA frequently cooperate. Indicative of this process is PEGIDA’s 200th event in Dresden in February of 2020, when AfD Thuringia leader Björn Höcke gave a guest speech, which attracted a few thousand participants, highlighting that more people by now come to ‘watch’ AfD than PEGIDA. Still, the group has remained an important symbol in German far-right politics, with its protest events remaining a popular point of reference among AfD politicians that want to show street presence. Some of those have now actively promoted a movement-party strategy, frequently reaching out to ideologically close street protestors (Heinze and Weisskircher Citation2021; see also Heinze and Weisskircher Citation2022 in this special issue).

Conclusion

This article has examined how social movement and protest dynamics have profoundly shaped the structuring and polarisation of German party politics in the last two decades. That is, we have discussed the movement-initiated spirals at play in the electoral breakthrough of the latest ‘additions’ to Germany’s multi-party system – Die Linke and AfD. While party-movement interactions have by now become an increasingly important topic in social movement studies, they figure much less prominently in standard accounts on the transformation of the German party system. To emphasise these dynamics, we have combined qualitative evidence with original protest event data and available public opinion data on shifts in issue attention and parties’ electoral fortunes.

Based on our paired case studies of the two challenger parties from the left and the right, we have illustrated a process constituted by two mechanisms, linking the protest and electoral arena and which help us to understand the relationship between anti-Hartz-IV mobilisation and Die Linke as well as PEGIDA and AfD: Movement emergence may trigger (1) an external politicisation spiral and (2) an intra-party innovation spiral, contributing to the electoral breakthrough of the challenger party. In contrast to the ‘standard model’ of movement-party emergence, we do not find significant organisational and personal overlap among our cases. Most importantly, we have emphasised how mass protest causes discursive shift, providing an opportunity for parties to ride the wave, mobilising on the protestors’ grievance in the electoral arena. While the electoral breakthrough and stabilisation of new parties in a highly institutionalised party system like the German one is due to multiple factors, the cases of Die Linke and AfD underscore that we should not overlook protest dynamics to understand challenger parties’ trajectories.

Our study also points to the importance of eastern Germany as the main site for these consequential party-movement interactions and the recent transformation of the German party system more generally (Patton Citation2017). Both Anti-Hartz-IV protest and PEGIDA mainly took off in the neue Bundesländer of eastern Germany. Eastern Germany has been fertile soil for initiating the transformation of party competition: This corresponds to research that shows how eastern Germans trust political parties less and that the eastern German party system is significantly more volatile (Arzheimer Citation2016). Overall, these patterns reflect the significant east–west divide in Germany, related to long-lasting economic, cultural, and political differences (Weisskircher Citation2020).

Beyond the case of Germany, our analysis calls for integrating what we have called system- and organisation-centered perspectives on party-movement interactions. A next step in this direction could be a more thorough assessment at the individual level, linking support and participation in specific protest events to the electoral fortune of challenger and mainstream parties. Moreover, online activism has become an increasingly important part for both street and party actors. The online sphere might provide ample opportunity for party politicians to ride the wave of social movement mobilisation – its impact on movement-party relations, however, has hardly been studied (but see Klinger et al. Citation2022). Crucially, future research should also investigate why most street protests do not give rise to external politicisation and intra-party innovation, and why some important exceptions, like the two cases discussed in this article, actually do.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the two reviewers for their helpful comments, as well as Danique van Dalen, Antonia Kühmichel, and Ines Schäfer for assisting the data collection process. Furthermore, we are grateful for the support of the Research Council of Norway (Reaching out to Close the Border, grant number 303219) and the Volkswagen Foundation (Lichtenberg Professorship, grant number 93598).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manès Weisskircher

Manès Weisskircher is postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography and affiliated researcher at the Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX), University of Oslo.

Swen Hutter

Swen Hutter is a Lichtenberg-Professor in political sociology at Freie Universität Berlin and Vice Director of the Center for Civil Society Research, a joint initiative of Freie Universität and WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

Endre Borbáth

Endre Borbáth is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Sociology, Freie Universität Berlin, and at the Center for Civil Society Research, a joint initiative of Freie Universität and WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

Notes

1 Apart from the comparative work cited above, see also Müller-Rommel Citation1985; Poguntke Citation1987.

2 As issues related to Hartz-IV we coded the following answer categories: ‘Renten und Alte’, ‘Sozialpolitik’, ‘Streikrecht, Tarife’, ‘Lohnfortzahlung’, ‘Arbeitslosigkeit’, ‘soziales Gefälle’, ‘Hartz IV, Montagsdemos’. As issues related to Pegida we coded the following answer categories: ‘Asylanten, Asyl’, ‘Ausländer’, ‘Islam, Islamismus’, ‘Pegida/Anti-Islam’, ‘Medien/Lügenpresse’.

3 For Pegida we use ‘pegida’, in conjunction with (‘Alternative für Deutschland’, ‘afd’). For Hartz IV we use (hartz*) AND (‘demonstration*’, ‘Montagsdemo*’), in conjunction with (‘PDS’, ‘Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus’, ‘WASG’, ‘Arbeit und soziale Gerechtigkeit’, ‘Linkspartei*’)

4 Importantly, as a precursor, the end of 2003 and the beginning of 2004 already saw street mobilization against the Agenda 2010 more generally (Rein Citation2008).

5 It is important to note that also the far-right NPD tried to link to the anti-Hartz-IV protest, which contributed to internal rifts.

6 The Berlin branch only renounced support in October 2004, when the protests had already become weak. In Berlin, divisions between the party and some of the Hartz IV protestors became most openly visible: in the capital, often two different marches against Hartz IV were held, one with far-left groups such as MLDP, another with PDS, Attac, and established trade unions.

7 Organisers were divided over whether to invite Lafontaine – the Leipziger Sozialforum was opposed to the invitation, preferring to stay politically neutral. At the end of Lafontaine’s speech, protestors chanted „Wir sind das Volk’, another inspiration coming from the 1989 demonstrations that was later also reused by PEGIDA.

8 In Southern Germany, trade unionists Klaus Ernst and Thomas Händel (both IG Metall) were key in forming the Initiative Arbeit & soziale Gerechtigkeit (Initiative for Labour and Social Justice; ASG), trying to influence SPD from the left. In Northern Germany, the Wahlalternative 2006 (Electoral Alternative 2006; WA), described as ‘left-wing democratic triangle’ (Vollmer Citation2013, 63), had an even broader left-wing agenda. Ultimately, both groups founded a common association, but not yet party, in July 2004, Arbeit und soziale Gerechtigkeit – die Wahlalternative (Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative; WASG) (Vollmer Citation2013, 67, 70).

9 In doing so, both sides overcame important concerns, related to the different strategic directions of a principled left-winged opposition (WASG) and an eastern Volkspartei in regional government (PDS), and the shadow of PDS’ SED past (Micus Citation2007).

10 PEGIDA was significantly less successful outside of Dresden: Here, it only had local and short-lasting mobilization successes, such as in nearby Leipzig (as LEGIDA).

References

- Art, David. 2018. “The Afd and the End of Containment in Germany?” German Politics and Society 36 (2, SI): 76–86.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2015. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?” West European Politics 38 (3): 535–556.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2016. “Wahlverhalten in Ost-West-Perspektive.” In Wahlen und Wähler. Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2013, edited by Harald Schoen, and Bernhard Weßels, 71–89. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2019. “Don’t Mention the War!” How Populist Right-Wing Radicalism Became (Almost) Normal in Germany”.” Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (S1): 90–102.

- Backes, Uwe, and Cas Mudde. 2000. “Germany: Extremism Without Successful Parties.” Parliamentary Affairs 53 (3): 457–468.

- Berker, Lars E., and Jan Pollex. 2021. “Friend or foe?—Comparing Party Reactions to Fridays for Future in a Party System Polarised Between AfD and Green Party.” Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 15: 165–183.

- Borbáth, Endre, and Swen Hutter. 2021. “Protesting Parties in Europe: A Comparative Analysis.” Party Politics 27 (5): 896–908.

- Bremer, Björn, Swen Hutter, und Hanspeter Kriesi. 2020. “Dynamics of Protest and Electoral Politics in the Great Recession.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (4): 842–866.

- Burstein, Paul. 1999. “Social Movements and Public Policy.” In How Social Movements Matter, edited by Marco Giugni, Doug McAdam, and Charles Tilly, 3–21. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Caiani, Manuela, and Ondrej Císař. 2019. Radical Right Movement Parties in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro, and Andrea Pirro. 2019. “The far Right as Social Movement.” European Societies 21 (4): 447–462.

- Chironi, Daniela, and Raffaella Fittipaldi. 2017. “Social Movements and New Forms of Political Organization: Podemos as a Hybrid Party.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 10 (1): 275–305.

- Close, Caroline, und Sergiu Gherghina. 2019. “Rethinking Intra-Party Cohesion: Towards a Conceptual and Analytical Framework.” Party Politics 25 (5): 652–663.

- Daphi, Priska, et al. 2015. Protestforschung am Limit. Eine soziologische Annäherung an PEGIDA. https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/protestforschung-am-limit_ipb-working-paper_web.pdf (01.07.2016).

- Decker, Frank. 2000. Über das Scheitern des neuen Rechtspopulismus in Deutschland Republikaner, Statt-Partei und der Bund Freier Bürger. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 29 (2): 237–255.

- de Nadal, Lluis. 2021. “On Populism and Social Movements: From the Indignados to Podemos.” Social Movement Studies 20 (1): 36–56.

- della Porta, Donatella, Joseba Fernández, Hara Kouki, and Lorenzo Mosca. 2017. Movement Parties Against Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Der Spiegel. 08.07.2015. Bernd Lucke zu seinem Austritt aus der AfD. Available at: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/bernd-lucke-erklaerung-zu-austritt-aus-der-afd-a-1042734.html (18.04.2021).

- Der Spiegel. 19.12.2014. AfD-Vize Gauland verteidigt Pegida-Märsche. Available at: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-und-pegida-afd-vize-gauland-rechtfertigt-pegida-maersche-a-1009270.html (18.04.2021).

- de Vries, Catherine, and Sara Hobolt. 2020. Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Diani, Mario. 1992. “The Concept of Social Movement.” The Sociological Review 40 (1): 1–25.

- Dostal, Jörg. 2017. “The Crisis of German Social Democracy Revisited.” The Political Quarterly 88 (2): 230–239.

- FAZ. 03.07.2005. Linke Alternative zu den „Hartz-IV-Parteien“. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/parteitag-der-wasg-linke-alternative-zu-den-hartz-iv-parteien-1252789.html (18.04.2021).

- FAZ. 08.01.2015. AfD schließt Zusammenarbeit mit Pegida nicht aus. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/pegida-afd-trifft-organisatoren-am-mittwoch-im-saechsischen-landtag-a-1010987.html (18.04.2021).

- FAZ. 28.06.2015. „ … dann kann es ein Kampf bis aufs Messer werden“. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/gauland-und-koelmel-im-streitgespraech-ueber-die-afd-13668346.html?printPagedArticle = true#pageIndex_2 (18.04.2021).

- Flügel, Der. 2015. Erfurter Resolution.

- Gaby, Sarah, and Neal Caren. 2016. “: The Rise of Inequality: How Social Movements Shape Discursive Fields.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly December 1 2016 21 (4): 413–429.

- Gheyle, Niels and Julia Rone. 2022. “‘The Politicization Game’: Strategic Interactions in the Contention over TTIP in Germany”. German Politics. Advance online publication.

- Goldstone, Jack. 2003. “Introduction: Bridging Institutionalized and Noninstitutionalized Politics.” In States, Parties, and Social Movements, edited by Jack Goldstone, 1–24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heinze, Anna-Sophie, and Manès Weisskircher. 2021. “No Strong Leaders Needed? AfD Party Organisation Between Collective Leadership, Internal Democracy, and ‘Movement-Party’ Strategy.” Politics and Governance 9 (4): 263–274.

- Heinze, Anna-Sophie, and Manès Weisskircher. 2022. “How Political Parties Respond to Pariah Street Protest: The Case of Anti-Corona Mobilisation in Germany.” German Politics. Advanced online publication.

- Hough, Dan, Michael Koß, and Jonathan Olson. 2007. The Left in Contemporary German Politics. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Hutter, Swen, and Endre Borbáth. 2019. “Challenges from Left and Right: The Long-Term Dynamics of Protest and Electoral Politics in Western Europe.” European Societies 21 (4): 482–512.

- Hutter, Swen, Hanspeter Kriesi, J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, and B. Klandermans. 2013. “Movements of the Left, Movements of the Right Reconsidered.” In The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, edited by Jacquelien van Stekelenburg, Conny Roggeband, and Bert Klandermans, 281–298. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2018. “Who Responds to Protest? Protest Politics and Party Responsiveness in Western Europe.” Party Politics 24 (4): 358–369.

- Hutter, Swen, Jasmine Lorenzini, Hanspeter Kriesi, D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, H. Kriesi, and H. J. McCammon. 2019. Social Movements in Interaction with Political Parties.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David Snow, Sarah Soule, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Holly McCammon, 322–337. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hutter, Swen and Manès Weisskircher. 2022. “New Contentious Politics. Civil Society, Social Movements, and the Polarization of German Politics.” German Politics. Advance online publication.

- Jennings, Will, and Clare Saunders. 2019. “Street Demonstrations and the Media Agenda: An Analysis of the Dynamics of Protest Agenda Setting.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (13-14): 2283–2313.

- Karapin, Roger. 2011. “Opportunity/Threat Spirals in the US Women’s Suffrage and German Anti-Immigration Movements.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 16 (1): 65–80.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1989. The Logics of Party Formation: Ecological Politics in Belgium and West Germany. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

- Kitschelt, Herbert, R. S. Katz, and W. J. Crotty. 2006. “Movement Parties.” In Handbook of Party Politics, edited by Richard Katz and William Crotty, 278–290. London/Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Klinger, Ulrike, Lance Bennett, Curd Knüpfer, Franziska Martini, and Xixuan Zhang. 2022. “From the fringes into mainstream politics: intermediary networks and movement-party coordination of a global anti-immigration campaign in Germany.” Information, Communication & Society. Advanced Online Publication.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Susan Olzak. 2004. “Discursive Opportunities and the Evolution of Right-Wing Violence in Germany.” American Journal of Sociology 110 (1): 198–230.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and J. Muis. 2009. “The Rise of Right-Wing Populist Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands: A Discursive Opportunity Approach.” European Journal of Political Research 48: 642–664.

- Koß, Michael. 2007. “Durch die Krise zum Erfolg? Die PDS und ihr Langer Weg Nach Westen.” In Die Linkspartei Zeitgemäße Idee Oder Bündnis Ohne Zukunft?, edited by Tim Spier, Felix Butzlaff, Matthias Micus, and Franz Walter, 117–153. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Ruud Koopmans, Jan Willem Duyvendak, and Marco Giugni. 1995. New Social Movements In Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McAdam, Doug. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- McAdam, Doug, and Karina Kloos. 2014. Deeply Divided: Racial Politics and Social Movements in Post-War America. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- McAdam, Doug, and Sidney Tarrow. 2010. “Ballots and Barricades: On the Reciprocal Relationship Between Elections and Social Movements.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (2): 529–542.

- McAdam, Doug, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly. 2001. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McCammon, H. J., C. S. Muse, H. D. Newman, and T. M. Terrell. 2007. “Movement Framing and Discursive Opportunity Structures: The Political Successes of the US Women’s Jury Movements.” American Sociological Review 72: 725–749.

- Meyer, David S., and Sidney Tarrow. 2018. The Resistance. The Dawn of the Anti-Trump Opposition Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Micus, Matthias. 2007. “Stärkung des Zentrums Perspektiven, Risiken und Chancen des Fusionsprozesses von PDS und WASG.” In Die Linkspartei. Zeitgemäße Idee Oder Bündnis Ohne Zukunft?, edited by Tim Spier, Felix Butzlaff, Matthias Micus, and Franz Walter, 185–237. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand. 1985. “Social Movements and the Greens: New Internal Politics in Germany.” European Journal of Political Research 13 (1): 53–67.

- Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand. 1989. New Politics in Western Europe. Boulder: Westview.

- Neues Deutschland. 18.08.2004. 100 PDS-Fahnen bleiben im Keller. https://www. https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/58194.pds-fahnen-bleiben-im-keller.html (18.04.2021).

- Neues Deutschland. 24.08.2004. »Wir sind Teil der Empörung«. https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/58516.wir-sind-teil-der-empoerung.html (18.04.2021).

- Neues Deutschland. 24.09.2004. Potsdaer Notfall. https://www.nd-aktuell.de/artikel/60199.potsdamer-normalfall.html (18.04.2021).

- Offe, Claus. 1990. “Reflections on the Institutional Self-Transformation of Movement Politics: A Tentative Stage Model.” In Challenging the Political Order, edited by Russell J. Dalton, and Manfred Küchler, 232–250. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Olsen, Jonathan. 2007. “The Merger of the PDS and WASG: From Eastern German Regional Party to National Radical Left Party?” German Politics 16 (2): 205–221.

- Patton, David. 2017. “Monday, Monday: Eastern Protest Movements and German Party Politics Since 1989.” German Politics 26 (4): 480–497.

- Petrocik, John. 1996. “Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850.

- Pirro, Andrea, Elena Pavan, Adam Fagan, and David Gazsi. 2021. “Close Ever, Distant Never? Integrating Protest Event and Social Network Approaches Into the Transformation of the Hungarian far Right.” Party Politics 27 (1): 22–34.

- Poguntke, Thomas. 1987. “The Organisation of a Participatory Party - The German Greens.” European Journal for Political Research 15 (6): 609–633.

- Portos, Martín. 2021. Grievances and Public Protests. Political Mobilisation in Spain in the Age of Austerity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rein, Harald. 2008. “Proteste von Arbeitslosen.” In Die Sozialen Bewegungen in Deutschland Seit 1945. Ein Handbuch, edited by Roland Roth, and Dieter Rucht, 593–612. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

- Rink, Dieter, and Axel Philipps. 2007. “Mobilisierungsframes auf den Anti-Hartz IV-Demonstrationen 2004.” Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen 20 (1): 52–60.

- Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. 2012. Findbücher/12. Bestand: Wahlalternative Arbeit und Soziale Gerechtigkeit (WASG) (2004 bis 2007). Available at: https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/ADS/Findbuch_12.pdf (20.04.2021).

- Rucht, Dieter, and Mundo Yang. 2004. “Wer Demonstrierte Gegen Hartz IV?” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 17 (4): 21–27.

- Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schwander, Hanna, and Philip Manow. 2017. “‘Modernize and Die’? German Social Democracy and the Electoral Consequences of the Agenda 2010.” Socio-Economic Review 15 (1): 117–134.

- Spoon, Jae-Jae, and Heike Klüver. 2014. “Do Parties Respond? How Electoral Context Influences Party Responsiveness.” Electoral Studies 35: 48–60.

- Spier, Tim, Felix Butzlaff, Matthias Micus, and Franz Walter. 2007. Die Linkspartei Zeitgemäße Idee Oder Bündnis Ohne Zukunft? Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Stier, Sebastian, Lisa Posch, Arnim Bleier, and Markus Strohmaier. 2017. “When Populists Become Popular: Comparing Facebook use by the Right-Wing Movement Pegida and German Political Parties.” Information, Communication and Society 20 (9): 1365–1388.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 1989. Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965-75. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 2010. “The Strategy of Paired Comparison: Toward a Theory of Practice.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (2): 230–259.

- taz. 01.08.2005. Einsame Party. https://taz.de/!567906/ (18.04.2021).

- Vliegenthart, Rens, Stefaan Walgrave, Ruud Wouters, Swen Hutter, Will Jennings, Roy Gava, Anke Tresch, et al. “The Media as a Dual Mediator of the Political Agenda–Setting Effect of Protest. A Longitudinal Study in Six Western European Countries.” Social Forces 95, no. 2 (2016): 837–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26166852.

- Volk, Sabine. 2021. “Die rechtspopulistische PEGIDA in der COVID-19-Pandemie.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 34 (2): 235–248.

- Vollmer, Andreas. 2013. Arbeit & Soziale Gerechtigkeit - Die Wahlalternative (WASG). Entstehung, Geschichte und Bilanz. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Vorländer, Hans, Maik Herold, and Steven Schäller. 2018. PEGIDA and New Right-Wing Populism in Germany. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2012. “The Complex Agenda-Setting Power of Protest: Demonstrations, Media, Parliament, Government, and Legislation in Belgium, 1993-2000.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 17 (2): 129–156.

- Weisskircher, Manès. 2020. “The Strength of Far-Right AfD in Eastern Germany: The East-West Divide and the Multiple Causes Behind ‘Populism.” The Political Quarterly 91 (3): 614–622.

- Weisskircher, Manès, and Lars-Erik Berntzen. 2019. “Remaining on the Streets. Anti- Islamic PEGIDA Mobilization and its Relationship to Far-Right Party Politics.” In Radical Right ‘Movement Parties’ in Europe, edited by Manuela Caiani, and Ondrej Cisar, 114–130. London and New York: Routledge.