ABSTRACT

Do lasting differences in the political cultures of social subgroups call into question the legitimacy of democracy? This danger has been discussed for three decades now, always in the run up to German Unity Day, which marks the reunification of Germany in 1990. Is there still a ‘wall in people’s minds’, as postulated in the late 1990s? This article examines the question comparatively and over time: Do political cultures and their main political attitudes still differ between Western and Eastern Germany 30 years after reunification? And, if so, to what extent? Using an extended concept of political support, we analyse East–West differences by drawing on different data material from representative surveys. What we show that there is no deficit of legitimacy in Eastern Germany in terms of democracy. Nevertheless, there are consistent East–West differences in terms of people’s satisfaction with democracy as it is currently practised. These differences can be explained neither by existing socio-economic and socio-structural inequalities between Eastern and Western Germany, and nor by feelings of nostalgia for socialism. Rather, they are due to a combination of feelings of disadvantage, of a lack of recognition, and corresponding narratives that can draw on objective manifestations of inequality.

Introduction – Persistence or Adaptation?

If we look at the 2017 and 2021 election results and public debates, it seems that the success of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party is due not only to its strong anti-immigration and anti-Islamic stance, but also to its self-portrayal as the party of East German citizens (Arzheimer Citation2019; Lengfeld and Dilger Citation2018).Footnote1 This ‘claim to represent the East Germans’ is not new. The Left (die Linke) party was considered for many years to represent specifically East German interests (see Zelle Citation1998). What is remarkable here is the consistency with which electoral behaviour in Eastern Germany deviates from that in Western Germany, and how persistent and virulent the idea of a kind of ‘East German special mentality’ is (Pickel Citation1998, 157–159). This is expressed not only in electoral behaviour, but also in various patterns of political attitudes, including attitudes towards democracy (see Conradt Citation2015; Dalton and Weldon Citation2010; Veen Citation1997). However, media observations of these differences are very different from how political science observes them. While there were still vehement arguments about a ‘wall in people’s minds’ in the late 1990s, these subsided in the early 2000s because it was assumed that generational change would level out the differences in attitudes. Only in the wake of the strengthening of the right-wing populist AfD since about 2018 have debates about the different political cultures in Eastern and Western Germany become important again,Footnote2 and there are now many descriptions of the Eastern German situation (Pollack Citation2020), some supported biographically (Mau Citation2019).

Besides the state of mind and mentality of East Germans, what is now of interest is the question of political-cultural coalescence and how attitudes are distributed in the population. Individual questions gauging how people assess democracy are repeatedly invoked to describe an apparent problem in Eastern Germany when it comes to the legitimacy of democracy. Also, public and academic discourse argue that society is becoming increasingly polarised and that social cohesion is dwindling.Footnote3 At the same time, though, other population surveys also show a high level of attachment to the idea of democracy among East Germans; they certainly do not want ‘the old GDR’ back. It is important for German democracy to resolve this issue. This is where research on political culture can help, since it focuses on the interplay between the legitimacy, effectiveness, and recognition of democracy (Almond and Verba Citation1963; Lipset Citation1981; Norris Citation1999). Such research assumes that the persistence of democracies depends on a democratic political culture among the population. Put simply, political culture comprises diffuse political support (legitimacy of the system and trust in its institutions), and specific political support (performance of the political system) (Easton Citation1979). According to this approach, the institutional structure of a democracy cannot survive if there is no democratic political culture. Democratic societies also live from the fact that their members recognise each other as free and equal citizens. It is precisely this recognition and mutual respect that could suffer from the entrenchment of different political cultures in a unified Germany.

In view of the 30th anniversary of reunification, we need to clarify various questions: Do the political cultures and the political attitudes most important to these cultures still differ between Western and Eastern Germany 30 years after the peaceful revolution – and, if so, to what extent? Should there be such consistent differences, then the follow-up question is: What are the reasons for these differences and the consequences for representative democracy?

The theoretical foundations of our work are provided by political culture theory, and more specifically research on political support (Easton Citation1975; Norris Citation1999). Our approach builds on the earlier work of authors and on the explanatory concepts already developed in the 1990s (Fuchs Citation2002; Norris and Inglehart Citation2019; Norris Citation1999; Pickel and Pickel Citation2006, Citation2016), and opens up the possibility of fitting current developments in a unified Germany into a theoretical structure. We draw on different approaches that have emerged in recent decades from discussions about East–West differences in political culture and political support to create our explanatory models of these differences (Pollack Citation1997; Veen Citation1997; Wegener and Liebig Citation2000). To answer the questions posed, we first use classical concepts of political culture theory and political support to derive a differentiated concept. We then focus our analysis on the differences in political support between Western and Eastern Germany, and present theoretical explanations. After a descriptive presentation of the indicators of political support and legitimacy, we test the explanatory approaches introduced using a combination of descriptive presentations and regression analyses.

The Reference Concept – Theory of Political Culture

Political Culture of Modern Societies

When looking at a potential crisis of representative democracy in the comparison between Western and Eastern Germany, it is worth using political culture theory as a reference concept. This is particularly so as Germany has traditionally been a much analysed case when political culture theory has been discussed (Almond and Verba Citation1963; Conradt Citation2015). According to classical research in the field, political culture refers to the attitudes and value orientations that the citizens of a collective entity (usually conceived nationally) have with regard to political objects, these attitudes and value orientations being the consequence of historical processes, collectively similar individual socialisation, and political experience (Almond and Verba Citation1963, 14). According to Almond and Verba (Citation1963), Lipset (Citation1981), Easton (Citation1975), and Norris (Citation1999), the theory of political culture covers the subjective side of politics in a communal system by aggregating the attitudes surveyed representatively that citizens have with regard to political objects. The primary goal of research on political culture is to capture the subjective conditions that promote or endanger the stability of a (democratic) political system (Almond and Verba Citation1963, 498). Thus, political culture focuses on the stability of a democratic political system. If the structure and culture of the political system are congruent, then the system is expected to last even when there are major (political, social or economic) crises. A democratic institutional system therefore needs a democratic political culture to survive in the long term. Easton (Citation1975) calls for positive political support from a substantial proportion of citizens without specifying it. In a meta-study, Diamond (Citation1999, 68–71) points out that if democratic political systems are to remain in place in the long term after a transition from an autocracy, then at least 70–75 percent of the population should show diffuse support for democracy and feel that it is legitimate. If 15 per cent of citizens turn out to be active opponents of democracy, then this poses a risk to the stability of the political system. One can stick to this proportion. In other words, if there is not at least a positive-neutral attitude towards the political system, then any crisis might threaten the system with collapse: most citizens will no longer be willing to stand up actively for the current system and will simply follow the existing rules and norms. The political structure will thereby change (reform) or collapse (revolution).

A political culture develops over generations (Conradt Citation2002). Different political objects in the political system can serve as reference points for political values and attitudes. Easton (Citation1975) did much to distinguish between these objects. We draw in this article on an extension of the concept of political support, which Easton understands as an attitude, favourable or unfavourable, that a person has towards a (political) object. Easton (Citation1979, 171–225) identifies three objects of political support. First, long-term diffuse support relates to the political community, the members of a political system, and their basic value patterns. A sense of community and an overarching object classification (such as the nation and the people living in it) are the basis of this component of the political order (Easton Citation1975). Second, the political regime includes the basic structure of the respective institutional system. The orientations refer to the institutions themselves, i.e. the roles of office. Third, short-term, specific political support for the object of political authority, on the other hand, applies to the holders of roles of political authority, who receive political support because people accept the decisions that they have made. The evaluations that citizens make result from their satisfaction with the outputs of the political authorities (Pickel Citation2016, 325).

According to Easton, authorities are the main object of specific support, such assessments being subject to fluctuations and external influences. A typical response to crises of specific support in democracies would be to replace political personnel by voting the government out of office. It is only when this fails as a strategy to combat the perceived ineffectiveness of the political system that problems arise at the level of the general political order. For example, the political system – in this case, democracy – faces a crisis of legitimacy (Pharr and Putnam Citation2000; Watanuki, Crozier, and Huntington Citation1975; Pickel Citation2019). Diffuse support is to be distinguished from specific support, since the former denotes an approval of objects for their own sake, Easton dividing such support into legitimacy and trust. Legitimacy arises when citizens believe that their own values and perceptions of the political system are consistent with its actual structure. Trust involves the hope that these objects or the persons representing them are ‘oriented towards the common good’ and is based on political socialisation and generalised output experiences. Short-term, specific support for the political system’s performance generates trust in the long term (for more detailed models see author 2016; Fuchs Citation2002, 37; Norris Citation2011, 24, 44).Footnote4

Political Culture in Germany – United Divided?

Turning to the situation in unified Germany today, we are interested in two areas: the fundamental legitimacy of the political system, and support for the current political system. Both form the core of legitimacy of the existing political system in Germany: that of representative democracy (Lipset Citation1981). De facto legitimacy of the values and norms of democracy ‘as such’ and political support for the values and norms of German democracy form the core of the long-term political support (diffuse support) that democratic political systems need to survive times of crisis (Diamond Citation1999). If this form of political support no longer exists, then there is the greatest danger for the survival of the political system. Economic or political effectiveness (short-term specific support) are then seen here rather as justifying factors for certain anchors of political support for democracy. Almond and Verba (Citation1963) identify different patterns of political orientations of citizens towards political objects – participant, subject or parochial culture as well as mixed types thereof – as a fundamental threat to the stability of political systems when the balance and mix of orientations within the population become imbalanced at the expense of one type of political culture. This is all the more true if supportive attitudes turn into apathetic or even alienated ones.

Political socialisation and political experience are crucial factors that generate political support and positive orientations towards political objects. If we follow previous research (Conradt Citation2015, 251–253), then we would expect an alignment of political cultures in Western and Eastern Germany after 30 years of reunification. However, empirical observations prove that this has not been the case for a long time.

Hypothesis (1): Even 30 years after reunification, Western and Eastern Germany differ in terms of key political and pre-political attitudes.

Conradt’s (Citation2015) assumption of adaptation contrasts with observations of differences between Western and Eastern Germany in terms of political support for democracy. Discussion in the German-speaking world uses different arguments to explain these differences. These arguments point to enduring economic differences (situation hypothesis), and to a primarily economic sense of injustice among East Germans when they compare themselves with West Germans (relative deprivation). Both arguments refer to political experience, while political socialisation is the assumption that there is a specific East German identity (identity hypothesis), and that the generations pass on different political socialisations in a democracy (West) and in an autocracy (East) (socialisation hypothesis).

Like some researchers working on political culture and political support, politicians still assumed in 1990 that existing differences in political attitudes would disappear due to the changes in political socialisation that generational change would bring about (socialisation hypothesis; Fuchs Citation1998; Fuchs, Roller, and Wessels Citation1997; Gabriel Citation2007; Rohrschneider Citation1999). This assumption is directly linked to the assumption made by classical research on political culture that a change in political socialisation due to the political framework conditions would alter political support (political upheaval). This research assumed that those born in the post-1989 ‘GDR’ would experience a different social environment and a different upbringing, and would therefore identify more strongly with the current democracy and less with the pre-1989 ‘GDR’, thus strengthening political support for German liberal democracy ().

Hypothesis (2): The more people believe in the benefits of (GDR) socialism, the less they support the legitimacy of the (German) political system and the less satisfied they are.

Table 1. Differences between Eastern and Western Germany – explanatory concepts.

Hypothesis (3): The more unfavourable the economic conditions in Eastern Germany are perceived to be, the more East Germans withhold their political support for German democracy.

Hypothesis (4): The more East Germans feel disadvantaged compared to West Germans, the less they support the legitimacy of German democracy and the less satisfied they are.

Hypothesis (5): A strong East German identity reduces people’s political support for and satisfaction with democracy.

Data and Methods

The database for the quantitative-empirical comparison comprises the European Social Surveys (ESS) (2002–2018), the German General Social Survey data series (GGSS) (1991–2018), and the Leipzig Authoritarianism Studies (LAS) (2002–2020). In addition, two lesser-known studies from Saxony are included in the analysis, since they allow statements to be made regarding the explanatory concepts of relative deprivation and the identity hypothesis. Unfortunately, this hypothesis is insufficiently operationalised in nationwide population surveys. Since in alternative surveys Saxony differs little from the other East German states in some of the results used, the results obtained there should be representative for Eastern Germany and transferable to the other Eastern German states (Backes and Kailitz Citation2020). In order to compile our time series on how the legitimacy of democracy has developed, we use data for 2010 from the ARD Deutschlandtrends, a survey conducted by public television in Germany. We think that combining different data sources allows us to gain an impression of developments in Germany. All the surveys that we use are representative and have more than 1,000 respondents.

As a dependent variable, we identified political support for democracy and the legitimacy of democracy as the most central resources for sustaining current democracy and democracy in general. We operationalise legitimacy in a tried and tested way by means of general attitudes towards democracy, although there are slight variations in the questions asked across the different datasets. As we will show in the following section, however, these variations have barely a differentiating effect. Political support is measured by satisfaction with democracy, which is also a standard instrument. For the explanatory variables, situation (via satisfaction with the economic situation) and socialisation (via attitude towards the idea of socialism) are easy to operationalise (). Relative deprivation can be measured well by assessing whether a person has a ‘fair’ standard of living. All three are established instruments. It is more difficult to capture the East Germans’ own identity, however. Here, we can only fall back on quite inadequate bridge items in the general population surveys, such as GGSS. For this reason, we also use data from two surveys in Saxony for the description. As additional, purely descriptive variables, we use publicly available data to illustrate attitudes towards reunification and to descriptive visualisations, we use linear regression models to answer the questions raised (; data from GGSS). We use these models mainly to identify effects of the indicators for the different approaches to explaining satisfaction with democracy.

Table 2. Operationalisation.

No Legitimacy Crisis, but Disenchantment with Politicians and Differences in Satisfaction with Democracy

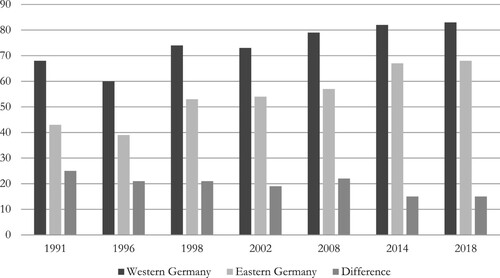

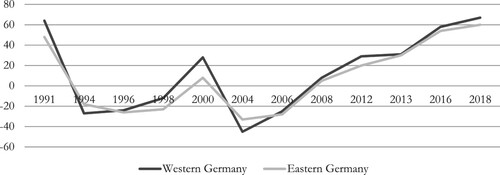

The initial question with regard to reunification is of course whether the citizens of Eastern Germany are still clinging to the former political system. If we look at current data, then we can conclude that this is by no means the case. The vast majority of Eastern German citizens agree that reunification was the right thing to do (), which was the case in 2004, and remained so until 2019. Although an even larger number of West Germans support reunification, the differences are minimal. Only a small minority of Germans want the wall back or see reunification as a mistake.

Figure 1. Approval of reunification.Sources: Forschungsgruppe Wahlen: Politbarometer-Extra 20 Jahre Mauerfall, 2009; Köber-Stiftung 30 Jahre Mauerfall, 2019; SFZ Volkssolidarität ‘20 Jahre friedliche Revolution’, 2010; Focus-Einheitsstudie, 2010.

If they do, then these feelings are symbolic trifles and memories of individual aspects of their former life in the pre-1989 ‘GDR’ that they dwell on, and in no case do they dwell on the political system itself. This is related to the key elements of political support.

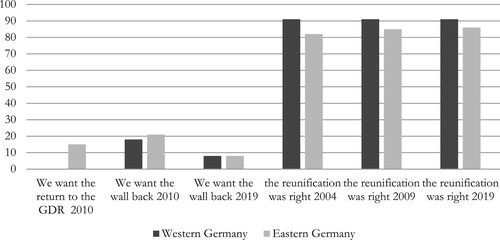

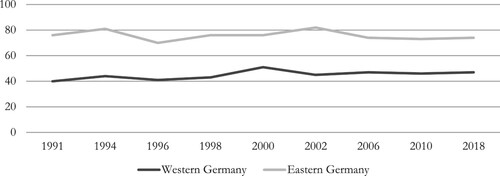

We can speak of democracy having a legitimacy deficit per se in neither West nor East Germany. In 2020, 90 per cent of West Germans and almost 90 per cent of East Germans viewed democracy as the best form of government, while 95 per cent and 91 per cent respectively considered democracy to be the most suitable political system for their own society, thus bestowing legitimacy on democracy (). Legitimacy has indeed been consistently high since 1991, which is in line with research on political culture. We cannot speak of a legitimacy crisis or of a legitimacy deficit on the part of democracy at least at this level – neither in Western nor in Eastern Germany. The levels in Eastern Germany regarding the legitimacy of democracy were still somewhat lower in 1991, but they have since been rising and are now close to the levels seen in Western Germany. However, since the question of support for democracy is very general, some room for interpretation remains. Ultimately, people’s ideas about what democracy is and what they expect (representative versus direct, liberal versus socialist) can vary considerably.

Figure 2. Legitimacy of democracy in Germany.Sources: Political culture in the new democracies (PCND), 2002; ARD-Deutschlandtrend, 2010; European Social Survey (ESS), 2002–2018 (6–10 on an 11-point scale); GGSS 1991–2018; Leipzig Authoritarianism Study (LAS), 2020; agreement in per cent.

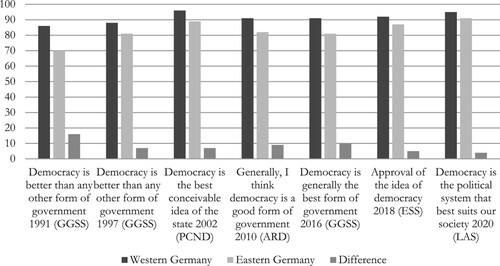

This now raises the question of how far people support the current system of democracy? Despite the current debates, the approval rates for democracy are decidedly positive here, too (). Even if other surveys that word their questions and answers differently sometimes yield somewhat lower rates of satisfaction, there is no general withdrawal of support for the system in Germany in this area, either – although there is occasionally a higher level of dissatisfaction and a certain scepticism (see GGSS or European Values Surveys). Dissatisfaction is recognisably more widespread in Eastern than in Western Germany, and it has shrunk only slightly since reunification. It is true that a process of adjustment between Eastern and Western Germans is also taking place here; it is just not complete yet.

It’s the Economy, Stupid – or is it Socialisation, or Identity?

But what accounts for the East–West differences? It makes sense here to look specifically at the central differences in satisfaction with democracy. Various factors show a statistical effect in the regression models (): statistically, the difference between Western and Eastern Germany in the level of satisfaction with democracy is due primarily to how people assess the overall economic situation in the Federal Republic of Germany (and not their personal economic situation). If a person deems the economic situation in Germany to be good, then he or she is very likely to support the current system of democracy (regardless of whether the person lives). This corresponds to the assumption made by research on political culture that economic success has a positive effect on support for democracy, even if this is captured here as a mediated perception (Lipset Citation1981; Welzel and Inglehart Citation2009). The opposite is the case if a person feels that he or she does not have a fair share with regard to the standard of living in Germany, which is an indicator of relative deprivation. If a person feels deprived or belongs to a disadvantaged group, then his or her level of satisfaction with the current system of democracy (but not with the legitimacy of democracy) falls. How people assess their identity, for which there are few reliable empirical data, also has an (albeit limited) effect, especially on people’s support for the political system.

Table 3. The foundations of democratic political support, 2018.

However, endorsement of the idea of socialism as an indicator of the socialisation hypothesis has no significant effect on satisfaction with democracy. With the exception of authoritarian attitudes and the rejection of a pluralistic society, which mainly influence attitudes towards the idea of democracy (i.e. legitimacy), the other factors have no significant effect. Interestingly, the structure of the explanatory model changed only slightly between 1991 and 2018. The idea of socialism has since lost relevance as an explanatory factor, and no longer had any influence on satisfaction with democracy and thus support for the system in 2018. The identity variables have also lost some of their influence. People’s assessment of their country’s economic well-being and relative deprivation remain the chief explanatory factors when it comes to people’s satisfaction with democracy. Thus, the answer to the question of why there are East–West differences with regard to satisfaction with democracy seems simple: the situation hypothesis is correct, and ‘it’s the economy, stupid’ (Walz and Brunner Citation1998, 113).

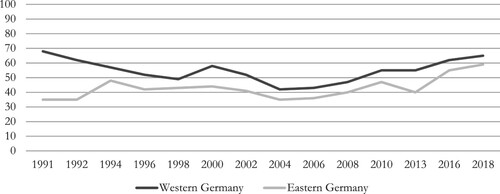

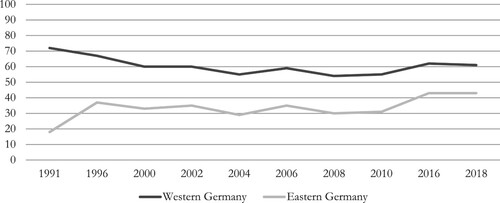

But an East–West comparison of how people assess the economic situation raises questions (see and ). Contrary to what supporters of the situation hypothesis assume, assessments of the economic situation in Germany have for several years now differed only slightly between Western and Eastern Germany. Almost 70 per cent of East Germans saw their economic situation as being good in 2018, which is only marginally lower than the assessment in Western Germany (). Assessments of the overall economic situation have converged increasingly in recent years (). East Germans underwent all the crises and economic successes together with West Germans and assessed them in a similar way. This becomes even clearer in how people have assessed their own economic situation since 1991, with East Germans adapting to West Germans early on in this regard; they no longer assess their situation in a fundamentally different way but do so in a way that is shaped by situational experiences. This also means, however, that, despite the influence of the economic situation on satisfaction with democracy found in , difference in political support between East and West Germans can’t result from the assessment of the economic situation due to this convergence of the assessments of prosperity. Only minor differences in how people assess the economic situation in Germany could have a negative effect on the assessment of the democratic system in Germany. But the effect of this difference is rather small. The minor East–West difference in the evaluation of the economic situation in Germany gives a first indication that specific (collective) perceptions have an effect.

Figure 4. Economic satisfaction in Germany.Source: GGSS 1991–2018; n > 2000; How do you assess the economic situation in Germany? (in per cent).

Figure 5. Satisfaction with own economic situation.Source: GGSS 1991–2018; n > 2000; How do you assess your own economic situation? Difference indicator: Answers of agreement-answers of disagreement.

Is it then, perhaps, the socialist upbringing () that causes the East–West differences? A look at the frequencies suggests that this could indeed be the case. Approval of the idea of socialism remained almost unchanged at around 70 per cent in Eastern Germany between 1991 and 2018 (GGSS) and was thus consistently 30 percentage points higher than approval in Western Germany (). The fact that the positive assessment of the idea of socialism is so consistent in both areas of the country is remarkable. In Germany, the idea of socialism seems to be strongly associated with equality and is understood to be the obverse of inequality. At the same time, the idea is now barely related directly to real existing socialism. Thus, judgments about the actually existing socialism of the pre-1989 ‘GDR’ are clearly predominantly negative (88 per cent). Moreover, the value in Western Germany can also be deemed relatively high and is higher than the rates of approval in many Eastern European states. Nevertheless, the relevance for political culture in Germany of attitudes towards the idea of socialism has diminished. Looking again at , we can see that attitudes towards the idea of socialism today (unlike in 1991) have no empirical relevance for attitudes towards contemporary democracy (or with regard to trust in political institutions). Although support for the idea of socialism differs in Germany, it no longer has any influence on political support for democracy. Thus, (non-existent) socialist nostalgia does not explain differences in satisfaction with democracy between Eastern and Western Germany.

Figure 6. Socialisation: The idea of socialism?Source: GGSS 1991–2018; n > 2000; Socialism as an idea is generally good, but it was poorly executed (in per cent).

If neither political socialisation nor the economic situation is the trigger, then what leads to the intra-German differences in satisfaction with democracy? One reason is relative deprivation (). While 35 per cent West Germans expected in 2018 to receive less or very much less than their fair share with regard to the standard of living, this figure has been 55–60 per cent in Eastern Germany for the last 25 years.

Figure 7. Relative deprivation in Germany.Source: GGSS 1991–2018; Compared to how others live here in Germany: Do you think you get your fair share? Answers = Get my fair share + get more than my fair share (in per cent).

While many East Germans are satisfied with their current economic situation, they feel that, as ‘East Germans’, they are disadvantaged compared to their West German counterparts. In 2018, for example, just 43 per cent of East Germans (compared to 61 per cent of West Germans) expected to receive their fair share with regard to the standard of living. This longstanding feeling of being treated unfairly has deep roots in many East German citizens (see also Foroutan and Hensel Citation2020). After convergence in the early 1990s in how East and West Germans assess whether they receive their fair share, there was hardly any such convergence in the 2000s. There is a clear and consistent gap in perceptions of inequality between Western and Eastern Germany, this gap causing East–West-differences in terms of people’s support for the political system at all points in time since 1991 (). The feeling of relative deprivation has a documented statistical effect on satisfaction with democracy. Thus, the central driving force behind a stronger dissatisfaction with democracy is the fact that East Germans do not feel that they receive their fair share when it comes to the standard of living in Germany.

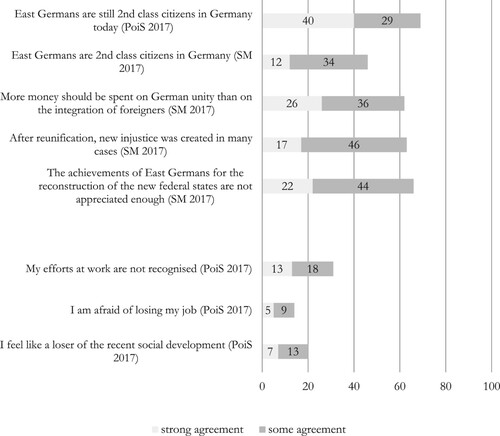

For many East Germans, the feeling of disadvantage is combined with the impression that they are devalued and disrespected by West Germans. In a survey limited to Saxony that was conducted in 2018, over 60 per cent of the respondents said that, ‘as East Germans in Germany’, they saw themselves ‘as second-class citizens’ (Sächsische Zeitung Citation2018, 1–2; ).Footnote6 Similar values are found in nationwide surveys (57 per cent in the German Unity Report, 2019; 70 per cent in surveys conducted by the Emnid opinion research institute, 2000–2010; 67 per cent in the LAS, 2020).Footnote7 At the same time, East Germans do not see themselves personally as losers of reunification (just 20 per cent; Saxony Monitor, 2016–2018, or Thuringia Monitor, 2010–2020; last three items in ). They feel like a disadvantaged identity group – disadvantaged collectively but not personally.

Figure 8. The sense of devalued identity and collective inequality (and the personal sense as point of comparison).Sources: Saxony Monitor (SM), 2016, 2017; Politics in Saxony (PoiS), 2017; Respondents in Saxony only; n > 1000; Answers of agreement in per cent; upper indicators related to collective identity, and lower indicators, to personal sense of deprivation (for reasons of comparison).

This feeling is based on a mixture of observations and narratives. It serves as a starting-point for an identity-based demarcation of East and West Germans. Narratives that have developed over a long period of time, such as the term ‘Besser-Wessi’ (know-it-all West Germans who patronise East Germans), or the idea of the merciless capitalist from the West who owns all the businesses in the former Eastern Germany. These narratives underlie an amalgamation of feelings, personal experiences, and objective examples of difference. The narrative of the West Germans who is not well-disposed towards the East Germans includes the evaluation of Treuhand (the trust agency established by the GDR to privatise East German enterprises), which is symbolically marked and negatively connoted as an instrument by which the West Germans humiliated the East Germans and liquidated their businesses and properties. A difference in identity opens up between East and West Germans at this point, one comprising a mixture of emotions, experiences of transformation, and observable inequalities (Decker and Brähler Citation2020, 22–23).

This is also shown by a simple change in the wording of surveys. For example, changing the second-class citizen question by adding ‘even today’ increases the rates of agreement with the statement by 13 percentage points. For many East Germans, the impression that living conditions are still unequal in Eastern and Western Germany outweighs their feeling that they are better off or at least doing well today. Two-thirds of those living in Saxony feel that the achievements of East Germans have not been and are still not appreciated adequately – and this in the East German federal state that has been the most successful economically since reunification. Almost as many believe that the transformation process since 1991 has created new injustices (). This ‘sense of mortification as an East German’ is partly transformed into a rejection of other groups, and especially of groups with a different identity, such as migrants and Muslims. This amalgamation of assessments, demarcations and feelings is the core element for understanding East German dissatisfaction. Few East Germans feel that their jobs are at risk (those that do see this as being caused by immigrants), hardly any see themselves personally as losers of reunification, and most feel that they are given recognition in their jobs (). But two-thirds of East Germans express agreement when it comes to discrimination, non-recognition, and devaluation with regard to East Germans as a collective group.

The consequences for representative democracy are considerable. Not only do right-wing populist parties in Eastern Germany succeed by referring to their own East identity; there is also less belief in the problem-solving abilities of representative democracy. Unlike with economic disparities, it is not possible to solve the problem caused by feelings of relative deprivation and the emergence of a special East German identity based on the notion of common disadvantage simply by redistributing political resources. There is still political support for the current system of democracy, but, if the cultural distance between Eastern and Western Germany is not addressed, then this will also have an impact on the legitimacy of representative democracy.

Summary – an Imagined Wall as a Danger for German Democracy

If we define the legitimacy of democracy in accordance with Diamond’s (Citation1999) guideline value of 70 per cent, then the data show that there is no deficit of legitimacy with regard to democracy in Germany (in neither Eastern nor Western Germany; ). However, the results presented also show that East–West differences in political culture are extremely stable. Despite people’s clear approval of reunification and democracy, there are still disparities in political culture 30 years after reunification. It is perhaps not necessary, as was the case in the 1990s, to speak of a ‘wall’ in people’s minds, but there are statistically significant and stable differences in attitudes. In contrast to the interpretation put forward by Conradt (Citation2015, 260), we can suggest that the identity thesis and deficits in recognition will play an important role in explaining differences in political culture in Germany. This is hardly the case for the legitimacy of democracy, which is high in West and Eastern Germany. In addition, certain ‘critical junctures’ have taken place in recent years that reinforce the idea among a group of citizens of a ‘still mentally divided Germany’ or ‘an imagined wall’, such as discussions about Treuhand, the solidarity surcharge, and the promotion of East Germans to leading positions in business and politics.Footnote8 As a consequence, the revitalisation of the East–West debate is part of the discussion that has emerged in recent years about a polarisation of political attitudes.Footnote9 This debate brings to the surface differences in attitudes between Eastern and Western Germans with regard to the current democratic system. These differences had long remained largely invisible but are now being taken up and exploited for their own purposes by the right-wing populist AfD (Wende 2.0), which is reinforcing dissatisfaction with (mostly Western) politicians and drawing on the perceived threat to identity posed by the influx of non-Christian refugees since 2015. Identity differences are thereby being used to strike at the heart of Germany’s political culture.

Besides minor shifts in terms of impact, the reasons for the differences in political support between East and West have also remained the same. Perhaps contrary to expectations, these differences are not, or hardly ever, due to socioeconomic dissatisfaction or to an attachment to the values and ideas of the previous socialist system. Rather, they are due to a feeling among East Germans that they are unfairly treated in comparison to West Germans. East–West differences in terms of support for the current democratic system are therefore a result of feelings of relative deprivation and collective disadvantage, as well as a lack of recognition. This feeling of collective disadvantage and lack of recognition arises from a combination of experiences, of experiences and narratives handed down and socialised further in recent decades. East Germans certainly want the advantages of democracy and (as shown) ascribe legitimacy to democracy, but many have doubts about how democracy is currently being implemented, and then withdraw their political support from it. In our opinion, this is a result of negative experiences at the time of reunification and during the process of transformation, experiences that were passed on in families and strengthened by new (negative) experiences of West Germans (e.g. Pollack Citation1997). That this feeling of collective disadvantage is justified is shown by the fact that East Germans are still objectively disadvantaged in Germany as a whole 30 years after reunification (in terms of participation in economic and political elites). It is a feeling less of actual personal disadvantage, and more of collective disadvantage. East Germans rarely feel disadvantaged as individuals, but often do so as a social group of ‘East Germans’.

Thus, the research question posed at the beginning of this article – ‘Do the political cultures and the political attitudes central to them still differ between Western and Eastern Germany 30 years after reunification, and to what extent?’ – can be answered as follows: Yes, they differ in terms of support for the current political system and how democracy is practised, but not in terms of the general legitimacy of democracy. This is still true 30 years after the fall of the wall. The reasons for the differences in attitudes have changed somewhat, but their core, i.e. the feeling of collective disadvantage, has remained central. Differences between Eastern and Western Germany are due less to socio-structural aspects, and more to cultural-identitarian feelings. These feelings are not so much individual assessments as group processes and the perception of group disadvantages, as well as the perception at least among many East Germans of a lack of recognition.

Why is this possibly dangerous for the common political culture? In the eastern part of Germany, feelings of apathy and alienation from German democracy have crept into the minds of many citizens: they still feel like second-class citizens and tie their satisfaction with German democracy almost exclusively to performance-based assessments of the political system. An important cause of this assessment is again a perception that divides East and West – the belief that the East has not benefited from reunification and is still disadvantaged. The AfD uses these attitudes, reinforces them, and can create a desire among some sympathisers and followers to eliminate German democracy, not only but especially in East Germany. Differences in political culture are thus related to perceived differences between East and West and consequently can only be resolved when these perceived differences are overcome.

Support for the idea of socialism is no longer part of these differences. Socialism no longer plays a role. Although the idea is more widespread in Eastern than in Western Germany, it is no longer related to the assessment of democracy. It remains to be seen whether these identity differences will lead in the future to a stronger polarisation of society. At present, the East–West differences in political support for the current system of democracy in Germany have become so entrenched that they will not be reduced in the next few years simply by generational change. Since these differences have now persisted through more than one generation, there is little hope that they will grow out generationally if Germany’s democratic politicians do not intervene.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susanne Pickel

Susanne Pickel is Chair of Comparative Politics at the University of Duisburg-Essen. She publishes on the topics of comparative politics, political science research methods and political culture. In recent years she has conducted research on understandings of democracy.

Gert Pickel

Gert Pickel is Chair of Religion and Church at Leipzig University. He works on the sociology of religion and political culture, social cohesion and prejudice. He has a long-standing interest in attitudes towards reunification and democracy in East–West comparison.

Notes

1 See Wagner (Arzheimer Citation2019, 98–100; Lengfeld and Dilger Citation2018, 190–195).

2 The extent to which this impression has also become entrenched in Germany can be seen from a survey conducted by the Forschungsgruppe Wahlen in 2019, in which 75 per cent of West Germans and 59 per cent of East Germans suspected that right-wing populist attitudes were more prevalent in the Eastern Germany (3 per cent Western Germany).

3 See Hebenstreit in this issue.

4 See Braun und Trüdinger in this issue.

5 In a survey conducted for the second German television broadcaster (ZDF) in June 2019, 49 per cent of East Germans and 30 per cent of West Germans said that there were still ‘Besser-Wessis’ (know-it-all West Germans) (Hübscher Citation2019).

6 Unfortunately, only the combination of data from Saxony was available for the corresponding items. Since alternative surveys have shown Saxony to differ little from the other Eastern German states in the results used, the results obtained for Saxony should be transferable to the other Eastern German states (see Backes and Kailitz Citation2020).

7 Only 20 per cent of West Germans have a similar opinion (our own calculation, LAS 2020).

8 See the articles of Kintz, of Veit and of Vogel in this issue.

9 See Hebenstreit and Wagner in this issue.

References

- Almond, Gabriel, and Sidney Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: University Press.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2019. “‘Don’t Mention the War!’ How Populist Right-Wing Radicalism Became (Almost) Normal in Germany.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57: 90–102.

- Backes, Uwe, and Steffen Kailitz, eds. 2020. Sachsen – Eine Hochburg des Rechtsextremismus? Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Conradt, David. 2002. “Political Culture in Unified Germany: The First Ten Years.” German Politics and Society 20 (2): 43–74.

- Conradt, David. 2015. “The Civic Culture and Unified Germany: An Overview.” German Politics 24 (3): 249–270.

- Dalton, Russell, and Steven Weldon. 2010. “Germans Divided? Political Culture in a United Germany.” German Politics 19 (1): 9–23.

- Decker, Oliver, and Elmas Brähler. 2020. Autoritäre Dynamiken. Alte Ressentiments – neue Radikalität. Leipziger Autoritarismus Studie 2020. Gießen: Psychosozial.

- Diamond, Larry. 1999. Developing Democracy. Toward Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

- Easton, David. 1975. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5: 435–457.

- Easton, David. 1979. A System Analysis of Political Life. New York: University Press.

- Foroutan, Naika, and Jana Hensel. 2020. Die Gesellschaft der Anderen. Berlin: Aufbau Verlag.

- Fuchs, Dieter. 1998. The Political Culture of Unified Germany. WZB Discussion Paper, FS III 98-204. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Fuchs, Dieter. 2002. “Das Konzept der politischen Kultur: Die Fortsetzung einer Kontroverse in konstruktiver Absicht.” In Bürger und Demokratie in Ost und West. Studien zur politischen Kultur und zum politischen Prozess. Festschrift für Hans-Dieter Klingemann, edited by Dieter Fuchs, Edeltraut Roller, and Bernhard Wessels, 27–49. Wiesbaden: VS.

- Fuchs, Dieter, Edeltraut Roller, and Bernhard Wessels. 1997. “Die Akzeptanz der Demokratie des vereinten Deutschlands. Oder: Wann ist ein Unterschied ein Unterschied?” Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 51: 3–12.

- Gabriel, Oscar. 2007. “Bürger und Demokratie im vereinigten Deutschland.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 48 (3): 540–552.

- Hübscher, Christine. 2019. Wie die Deutschen in Ost und West übereinander denken. https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/heute/umfrage-zur-zdf-deutschland-bilanz-wie-die-deutschen-in-ost-und-west-uebereinander-denken-100.html.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: University Press.

- Lengfeld, Holger, and Clara Dilger. 2018. “Kulturelle und ökonomische Bedrohung. Eine Analyse der Ursachen der Parteiidentifikation mit der „Alternative für Deutschland“ mit dem Sozio-Oekonomischen Panel 2016.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 47 (3): 181–199.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1981. Political Man. The Social Bases of Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Print.

- Mau, Steffen. 2019. Lütten Klein. Leben in der ostdeutschen Transformationsgesellschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

- Norris, Pippa. 1999. Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Government? Oxford: University Press.

- Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit. Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: University Press.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash. Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: University Press.

- Pharr, Susan, and Robert Putnam. 2000. Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries. Princeton: University Press.

- Pickel, Gert. 1998. “Eine ostdeutsche “Sondermentalität acht Jahre nach der Vereinigung? Fazit einer Diskussion um Sozialisation und Situation.” In Politische Einheit – Kultureller Zwiespalt? Die Erklärung politischer und demokratischer Einstellungen in Ostdeutschland vor der Bundestagswahl 1998, edited by Susanne Pickel, Gert Pickel, and Dieter Walz, 157–178. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

- Pickel, Susanne. 2016. “Konzepte und Verständnisse von Demokratie in Ost- und Westeuropa.” In Demokratie jenseits des Westens. Theorien, Diskurse, Einstellungen. Sonderheft 51. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, edited by Sophia Schubert, and Alexander Weiß, 318–342. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Pickel, Gert. 2019. “Auf dem Weg in die Postdemokratie.” In Legitimität und Legitimation, edited by Claudia Wiesner, and Philipp Harfst, 97–138. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Pickel, Susanne, and Gert Pickel. 2006. Politische Kultur- und Demokratieforschung. Grundbegriffe, Theorien, Methoden. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Pickel, Susanne, and Gert Pickel. 2016. “Politische Kultur in der Vergleichenden Politikwissenschaft.” In Handbuch Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, edited by Hans-Joachim Lauth, Marianne Kneuer, and Gert Pickel, 541–556. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Pollack, Detlef. 1997. “Das Bedürfnis nach sozialer Anerkennung: der Wandel der Akzeptanz von Demokratie und Marktwirtschaft in Ostdeutschland.” Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte B13: 3–14.

- Pollack, Detlef. 2020. Das unzufriedene Volk. Protest und Ressentiment in Ostdeutschland von der friedlichen Revolution bis heute. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Rohrschneider, Robert. 1999. Learning Democracy: Democratic and Economical Values in Unified Germany. Oxford: University Press.

- Sächsische Zeitung. 2018. Jeder zweite Sachse fühlt sich benachteiligt: 1–2.

- Veen, Hans-Joachim. 1997. “‘Inner Unity’ - Back to the Community Myth? A Plea for a Basic Consensus.” German Politics 6 (3): 1–15.

- Walz, Dieter, and Wolfram Brunner. 1998. “It’s the Economy, Stupid!” – Revisited. Die Ostdeutschen als Bürger zweiter Klasse? – Benachteiligungsgefühle in Ostdeutschland vor der Bundestagswahl 1998.” In Politische Einheit – Kultureller Zwiespalt? Die Erklärung politischer und demokratischer Einstellungen in Ostdeutschland vor der Bundestagswahl, edited by Susanne Pickel, Gert Pickel, and Dieter Walz, 113–130. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

- Watanuki, Joji, Michel Crozier, and Samuel P. Huntington. 1975. The Crisis of Democracy: Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission. New York: New York University Press.

- Wegener, Bernd, and Stefan Liebig. 2000. “Is the “Inner Wall” Here to Stay? Justice Ideologies in Unified Germany.” Social Justice Research 13: 177–197.

- Welzel, Christian, and Ronald Inglehart. 2009. “Political Culture, Mass Beliefs, and Value Change.” In Democratization, edited by Christian Haerpfer, Patrick Bernhagen, Ronald Inglehart, and Christian Welzel, 126–144. Oxford: University Press.

- Zelle, Carsten. 1998. “Factors Explaining the Increase in PDS Support after Unification.” In Stability and Change in German Elections: How Electorates Merge, Converge or Collide, edited by Christopher Anderson, and Carsten Zelle, 188–207. New York: Praeger.