ABSTRACT

Studies have shown that foreign policy events can sway voting intentions. While initial analyses have explored Germany’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its foreign policy implications, public perspectives on this matter remain relatively unexplored, despite visible consequences like soaring energy and food prices, and concerns about escalating the war. To address this gap, the article delves into how Germans’ attitudes towards NATO’s role in the Russian invasion and the supply of weapons to Ukraine impact their voting intentions. Drawing on GLES data, our research reveals that rejecting further weapons deliveries significantly increases support for the radical-right AfD. Conversely, endorsement of such deliveries sees increased support for the Greens, FDP, and CDU/CSU. No significant effects are observed for the SPD and the Left Party. Notably, attitudes towards NATO and weapons play a role in the likelihood of supporting a new party associated with former Left Party politician, Sahra Wagenknecht. Crucially, these effects persist even when considering socio-demographic and ideological factors, underscoring the pivotal role of these issues in shaping party competition.

Can We Find the ‘Zeitenwende’ at the Ballot Box?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in Spring 2022 represents a significant geopolitical event that has led to substantial political, economic, and humanitarian consequences. It also led to widespread condemnation from the international community (Blumenau Citation2022; Arzheimer Citation2023; Masch et al. Citation2023). It has strained relations between Russia and Western nations, resulting in sanctions and diplomatic tensions (Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023). In a remarkable departure from its longstanding foreign policy stance, Germany finds itself at the centre of a geopolitical Zeitenwende (political paradigm shift), as it takes unprecedented steps to support Ukraine in the face of the Russian invasion (Blumenau Citation2022; Fröhlich Citation2023; Mader and Schoen Citation2023; Masch et al. Citation2023). As Germany undergoes ‘an international orientation change in (…) foreign policy’ (Mello Citation2024), it becomes imperative to explore the implications of such a strategic shift on the domestic front. While previous studies have been mainly focussed on the German policy shift itself in order to react to the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Fröhlich Citation2023; Mader and Schoen Citation2023), party reactions (Wondreys Citation2023) or the shift of public opinion in the months following the invasion (Masch et al. Citation2023), potential electoral consequences have yet to be analysed. This specifically is of great importance as previous studies have impressively demonstrated the extent to which foreign policy crises contribute to the politicisation of the German public (e.g. Rattinger Citation1990a, Citation1990b; Pulzer Citation2003; Schoen Citation2004).

In this research, we examine the attitudes of the German public towards foreign policy and voting intentions using recent German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) data. We focus on perceptions regarding NATO’s role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine and whether Germany should continue supporting Ukraine militarily. Germany offers a particularly interesting case that can be used to explain why the extent to which the parties condemned the invasion diverged greatly and why it might have an impact on the party electorates (Mader and Schoen Citation2023). These historical influences continue to manifest culturally today (Kleuters Citation2012; Pickel and Pickel Citation2023), shaping the party system and foreign policy attitudes towards NATO (Gavras et al. Citation2020).

Notably, we examine domestic voter attitudes during the war in Ukraine, drawing connections between party politics and foreign policy analysis. The research confirms some common assumptions, such as strong support for Ukraine among Greens supporters and a significant portion of AfD voters believing NATO provoked Russia. Moreover, it sheds light on how attitudes towards the newly launched Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) correlate with beliefs about NATO’s role and military support for Ukraine. These findings are particularly significant given that no other voter group had as many voters indicating their choice was due to the party’s anti-war stance as the BSW in the 2024 European election (Tagesschau Citation2024). This study contributes significantly to existing literature by bridging the gap between party politics and foreign policy discourse.

In the following sections, we delve into the implications of this significant shift in foreign policy and explore how these developments are related to voter perceptions and influencing political stances in Germany. Firstly, we discuss the literature on foreign policy attitudes before examining the specific relationship between Germany and Russia prior to the Russian war on Ukraine. Secondly, we elaborate on the party positions on Russia and the party’s responses to the invasion before hypothesising our expectations. Following this, we discuss our research design before presenting our analysis and concluding our research.

Vote Intentions and Foreign Policy Attitudes

For a long time, foreign issue voting was neglected in empirical election research (Campbell, Gurin, and Miller Citation1954; Citation1960). Elites hesitated to acknowledge public opinion on foreign policies. The public was not deemed capable of forming a reliable opinion on this matter, as it was considered overly complex and not something ordinary citizens engage with (Lippmann Citation1955; Holsti Citation1992). The notion that ‘voting ends at the water’s edge’ (Aldrich et al. Citation2006, 477) shaped the general understanding, suggesting that foreign policy attitudes could be excluded from models explaining voting behaviour because they were not considered pertinent to the public in their voting decisions.

However, subsequent decades have shown that foreign policy positions not only structure party competition (Masch et al. Citation2023), but also significantly influence individual voting behaviour (Milner and Tingley Citation2015; Angelucci and Isernia Citation2020; Rattinger Citation1990a). In contrast to earlier literature, international affairs have ‘become salient and controversial on the level of mass politics’ (Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2014, 1275; Pulzer Citation2003; Schoen Citation2004). Although domestic issues continue to be regarded as dominant factors influencing electoral decisions (Rattinger Citation1990b; Milner and Tingley Citation2015), individuals may periodically be influenced by major foreign policy events (Aldrich, Sullivan, and Borgida Citation1989; Masch et al. Citation2023). For example, in the context of international crises and subsequent reactions, ‘foreign policy performance voting’ (Oktay Citation2018, 588) can be observed, in which the behaviour of political elites is sanctioned or gratified (Schoen Citation2004). Therefore, leaders make conscious efforts to influence public opinion in their favour, knowing the importance of gaining public support for military undertakings (Stein Citation2015; Wittkopf Citation1990). However, fundamental foreign policy positions are not only formulated based on public opinion. They are also subject to historical dynamics of party development, from which they derive part of their identity (Chryssogelos Citation2022; Wondreys Citation2023). In this research, we examine the case of Germany in terms of how different electorates have responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Following Graf, Steinbrecher, and Biehl (Citation2024), the German case is particularly informative, as it presents us with an important player in NATO, along with a complex history and responsibilities. In the following section, we outline the important context dependencies that influence the German case to fully understand the role of foreign policy being associated with voting intentions for political parties in Germany.

The Case of Germany

German-Russian Relations

The historical and economic ties between the Federal Republic of Germany and the former Soviet Union, as well as present-day Russia, are closely linked due to the enduring impact of the German division into the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The division has shaped German foreign policy and political attitudes for decades within both parts of the country (Pickel and Pickel Citation2023). Initially, parts of the political elite, particularly the left-leaning SPD, aimed for West Germany to be more neutral and act as a bridge between East and West, while the Christian Democrats advocated for a clear commitment to the West (Blumenau Citation2022; Kleuters Citation2012). The détente policy of Social Democratic chancellors in collaboration with the liberal FDP from 1969 sought reconciliation not only with the GDR but also with the Soviet Union, facing opposition from the Christian Democrats (Kleuters Citation2012; Hofmann and Martill Citation2021). This policy of rapprochement later became a significant factor leading to German unification in 1990 during the Christian Democrat chancellorship of Helmut Kohl (Kleuters Citation2012).

West and East Germany were reunified into a single state in 1990; however, noticeable differences in voting behaviour, political culture, derived political attitudes, and generally divergent political interests persist to this day (Pickel and Pickel Citation2023). A visible consequence of German division is also found in the fact that the political party systems of Western and Eastern Germany significantly differ, with distinct regional identities and strong political forces emerging. The once totalitarian ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) transformed into the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), which, in 2007, merged with a social democratic splinter party to form the new all-German Left, although its electoral successes continued to be mainly confined to Eastern Germany. This historical context explains why The Left Party, considering itself a representative of Eastern German culture and a voice for peace (Hough and Keith Citation2019; Wurthmann Citation2023), occupied NATO-sceptical positions for years and called for the abolition of NATO (Gavras et al. Citation2020). Whether these historical ties may have influenced the political parties’ positions on the Russian invasion of Ukraine will be explained in the following.

German Parties’ Reactions to the Invasion and its Consequences

Representatives of almost all German parties initially condemned the Russian invasion on February 24th, 2022. At the same time, they resisted calls for weapons shipments or further support to Ukraine, citing the risk of escalation by Russia and insisting on Germany’s long-standing foreign policy philosophy not to intervene in armed conflicts (Deutsche Welle Citation2022).Footnote1 Few days after the invasion, a political paradigm shift was decided upon, involving the delivery of weapons to Ukraine and comprehensive sanctions against Russia (Fröhlich Citation2023; Mader and Schoen Citation2023; Masch et al. Citation2023). While Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), Social Democrats (SPD), Free Democrats (FDP), and Greens followed a common course, radical left (the Left Party) and radical right (AfD) parties voted against the proposal. The Left Party justified their stance with a commitment to disarmament and opposition to weapons shipments. The AfD pointed to Western culpability for the escalations, even accusing Chancellor Scholz of reactivating the Cold War (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2022). For this reason, Mader and Schoen (Citation2023, 532) rightly note that ‘there were different levels of condemnation of Russia and different positions on how assertive the new Russia policy should be’ across German political parties.

Notable politicians had to admit to underestimating the situation in Ukraine prior to the war such as FDP politician and Vice President of the Bundestag Wolfgang Kubicki, a supporter of German Ostpolitik and détente policies (Schult and Weiland Citation2022). While in the past, Kubicki had opposed the deployment of NATO soldiers on the eastern Polish border in 2015, arguing that these might be perceived as a threat by Russia (Wallet Citation2015), FDP defence experts criticised Germany for not providing sufficient support to Ukraine, particularly urging more decisive action on weapons shipments (Tagesschau Citation2022a). Overall, the FDP leadership has been openly supportive of Ukraine and of NATO. The SPD, having an ambiguous stance on how to react to the war, faced internal conflicts between foreign policy realists/pragmatists and advocates for peace efforts. The party’s hesitant position is marked by delays in offering support to Ukraine, largely influenced by the internal dispute between these two factions (Terhalle Citation2023). One of the reasons for this could be the SPD’s foreign policy philosophy Wandel Durch Annäherung (change through rapprochement), in which trade was used to encourage systemic transformation in authoritarian regimes (Blumenau Citation2022; Mello Citation2024). Notably, SPD Chancellor Scholz delayed the delivery of so-called ‘offensive’Footnote2 weapons for months. In late April 2022, he described the risk of a possible nuclear war, which he intended to prevent (Amann and Knobbe Citation2022). The caution exhibited by the Social Democrats in dealing with support for Ukraine, was evident in June 2022 when the incumbent SPD Defence Minister refused to label the anti-aircraft tank Gepard a tank. There was a significant fear that doing so might be interpreted as an escalation by the Russian side (Metzger and Klaus Citation2022). From July 2022 onwards, the debate intensified, with representatives of CDU/CSU, FDP, and Greens calling for direct weapon deliveries to Ukraine, while the SPD remained opposed (Schulze Citation2022), causing ‘substantial friction within the government, particularly between the SPD and Greens’ (Mello Citation2024, 12).

In September and October 2022, the German debate shifted as the three-way exchange process (‘Ringtausch’) enabled the delivery of tanks to Ukraine. Germany supplied modern weapons to NATO partners, allowing them to deliver older models of battle tanks to Ukraine (Tagesschau Citation2022b). Following weeks of debate, the German government decided in January 2023 to directly supply Leopard 2 battle tanks to Ukraine, marking a paradigm shift in German foreign policy (Tagesschau Citation2023).

In protest at this decision, a peace demonstration took place organised by Left Party politician Sahra Wagenknecht, who has since left the party (Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek Citation2023). Wagenknecht became known as ‘the key figure of the current anti-war movement in Germany’ (Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023, 210). In the past, Wagenknecht has argued that the West is fighting an economic war against Russia, calling for an end to sanctions and the immediate resumption of gas deliveries to Germany— causing dissent within the Left Party leadership (Wolf Citation2022). In June 2022, the Left Party’s congress called for an end to weapons deliveries while demanding comprehensive sanctions against Russian elites and peace negotiations conditioned on a complete withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory. This was met with rejection by Wagenknecht and her supporters. The German left attempted to maintain a neutral position, opposing the supply of weapons to Ukraine, corresponding to an increasingly ‘equidistant’ position. Finding a clear stance on the Russian aggression in Ukraine paralysed the Left Party. In March 2023, Bernd Riexinger, former party chairman, described his party as highly divided. While some actors within the party were condemning the Russian invasion, others insisted that doing so would be a relativisation of U.S. imperialistic aspirations and dissent was held on arms shipments to Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia (Riexinger Citation2023).

Besides Wagenknecht, the AfD also rejected weapons deliveries to Ukraine (Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023). Moreover, the party articulated a mutual political responsibility for the war, blaming Russia and emphasising Western involvement (Wondreys Citation2023), similar to Wagenknecht’s faction within the Left Party. While ‘the parties on the political fringes condemned the Russian attack, they did so less vehemently and were critical of German arms deliveries to Ukraine’ (Mader and Schoen Citation2023, 541). More critically, Wagenknecht and the AfD have been ‘open advocates of Russia, putting appeasement actions towards it as its major foreign policy priority’ (Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023, 201). Both the AfD and Wagenknecht emphasised that economic rapprochement is the only way in which peace in Ukraine can be achieved, and any sanctions, regardless of their nature, would only harm this process (Wondreys Citation2023). The fact that this resonated with voters in the 2024 European election is evidenced by the very strong approval ratings for this policy among the voters of Wagenknecht’s new party, the BSW (Tagesschau Citation2024).

On the Association of Foreign and Security Policy with Voting Intentions

The link between public opinion and political responses is crucial, especially during crises and increasing polarisation along foreign policy lines (Aldrich, Sullivan, and Borgida Citation1989; Schoen Citation2004). This dynamic is expected to apply to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Recent findings indicate that the invasion has not reversed fundamental foreign policy perspectives among the German public (Masch et al. Citation2023). However, it has impacted attitudes directly linked to the war (see Graf, Steinbrecher, and Biehl Citation2024; Mader and Schoen Citation2023; Mader Citation2022).

During times of significant crises, there tends to be a surge in unity among citizens, leading to heightened levels of political support for those in power or their policies. This rally-round-the-flag phenomenon plays a pivotal role in how threats affect governing bodies by granting policymakers the flexibility to navigate challenging decisions and bridge political divides (Mueller Citation1970). Johansson, Hopmann, and Shehata (Citation2021) highlight two essential elements of this effect: salience and polarisation. Public support tends to rise when a crisis captures the public’s attention and when support transcends political affiliations. However, this effect does not remain constant over time and polarisation on national, and European, policies accelerate this decline (Truchlewski, Oana, and Moise Citation2023). As Graf, Steinbrecher, and Biehl (Citation2024) examine, solidarity among the German public for Ukraine has shown a significant shift. As the public started perceiving Russia as a threat to German security (Kucharczyk and Lada-Konefal Citation2022; Zink Citation2022), war-related attitudes towards the invasion are likely to be related to voting intentions in Germany.

Two key issues in the German debate are first, the responsibility for the escalation with some parties attributing responsibility to NATO expansion while others solely blame Russia; and, second, the question of deliveries of weapons to Ukraine.Footnote3 We argue that both these issues will be resonating in different ways among the electorate of political parties in Germany. Based on the party’s responses during the initial stages of the war and their long-term policies towards Russia, the positions of the parties are likely to be reflected within the supporters of the parties. In this research, we are testing whether some long-held assumptions on these electorates hold true in terms of their foreign policy preferences, specifically in relation to the highly salient issue of the Russian war on Ukraine (Graf Citation2024). We divide our expectations by voting intentions towards the different parties in the German party system, as we expect that there is a strong relationship between the preferences of individuals on NATO and/or weapon exports and the likelihood of voting for a specific party in the party system.

In both issues, attributing responsibility to NATO and weapon exports, the AfD, aligning early with Russia (Wondreys Citation2023; Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023), and whose supporters minimally advocated for Ukraine’s support (Masch et al. Citation2023), has developed a distinctive position. The AfD consistently called for closer ties with Russia, an end to sanctions, and a halt to weapons deliveries. This should be reflected in the demand-side perspective. Therefore:

H1: The stronger the approval of the statements that the war was provoked by NATO and in favour of a weapons delivery stop, the more likely is an intention to vote for the AfD.

H2: The stronger the approval of the statements that the war was provoked by NATO and in favour of a weapons delivery stop, the less likely is an intention to vote for the Greens.

H3: The stronger the approval of the statements that the war was provoked by NATO and in favour of a weapons delivery stop, the less likely is an intention to vote for the CDU/CSU.

H4: The stronger the approval of the statements that the war was provoked by NATO and in favour of a weapons delivery stop, the less likely is an intention to vote for the FDP.

Similarly, in terms of the Left Party, internal divisions are evident in how to deal with the war in Ukraine. Strongly revisionist positions, blaming NATO, and categorically rejecting weapon deliveries can be found, especially in the Left Party around then Left Party politician Sahra Wagenknecht. Therefore, based on Riexinger (Citation2023) and the discussions about Wagenknecht in Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek (Citation2023) and Hartleb and Schiebel (Citation2023), no directional expectation on the Left Party can be hypothesised. However, considering Wagenknecht’s salient positioning, and in the context of the new party by Wagenknecht, we argue that NATO- and weapons-critical positions may contribute to the success of Wagenknecht’s future party. This is particularly notable as many voters cited the party’s anti-war stance as their reason for support in the 2024 European election (Tagesschau Citation2024). Our hypothesis is as follows:

H5: The stronger the approval of the statements that the war was provoked by NATO and in favour of a weapons delivery stop, the more likely the support of a Wagenknecht party.

Research Design

Case Selection and Data

To address our research inquiry, we will utilise data from the GLES. A total of 1,112 individuals were surveyed between April 17, 2023, and April 21, 2023. The chosen survey period is especially pertinent for our research question, given that the survey was carried out in the aftermath of the intense discourse in Germany concerning the provision of armoured vehicles to Ukraine. Additionally, a few weeks prior to the survey, there was a notable peace demonstration organised under the leadership of Sahra Wagenknecht, an event that received subsequent coverage in both the media and literature (Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek Citation2023; Arzheimer Citation2023). The data sample was gathered using a quota sampling method applied for an online access panel, aligning with recommended age, gender, and education parameters for the online population derived from a study conducted by the Society for Integrated Communication Research (Gesellschaft für integrierte Kommunikationsforschung). To mitigate socio-demographic variations, GLES employs design weighting in its surveys, adjusting the analyses according to parameters identified in the micro-census (for more information, see the documentation of GLES Tracking T54, ZA7712). These weights have been applied in our contribution.

Dependent Variables

The central variable to be explained is the respondents’ intention to vote for one of the parties currently represented in the German parliament. For this purpose, respondents were asked which party they intended to vote for if there was an election held next Sunday. The participants received a list containing the parties represented in the Bundestag: SPD, CDU/CSU, Greens, FDP, AfD, and the Left Party. Additionally, they had the opportunity to indicate other alternatives. This arrangement led to the creation of six dichotomously encoded variables to operationalise vote intention. Each variable portrays voting behaviour, indicating support for one of the mentioned parties (coded as 1), or lack thereof for the parties not explicitly stated (coded as 0).

To gauge support for Wagenknecht, the GLES questionnaire included the following item: Please indicate how likely you think it is, generally speaking, to vote for a party that could be re-established under the leadership of politician Sahra Wagenknecht? To answer this question, the survey participants were able to indicate their position on a scale from (1) −5 very unlikely to (11) + 5 very likely. In contrast to the preceding analysis of vote intention, the propensity to vote is instead an indicator reflecting electoral accessibility, not the specific intention to vote for a certain party (Wagner and Krause Citation2021). As the BSW was announced six months after this survey was fielded, this indicator is subject to several uncertainties that cannot be conclusively resolved here.

Independent Variables

The central concern of this article is to examine the influence of attitudes on specific issues that explicitly refer to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the war that broke out as a result. For this purpose, the respondents were presented with a series of statements, which they were then asked to rate on a scale from (1) Strongly agree to (2) Agree via (3) Neither agree nor disagree and (4) Disagree to (5) Strongly disagree. Regarding the invasion, respondents were asked to give their assessment of the following statement: NATO provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Regarding the question of how Germany should behave with regard to the war, respondents were asked to express their attitudes towards the following statement: Germany should completely stop supplying weapons to Ukraine.

Control Variables

Traditionally, Western party systems such as Germany are described by a socio-economic and a socio-cultural conflict dimension (Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek Citation2023). Accordingly, the respondents’ attitudes to the following two statements are included as representatives of the socio-economic dimension: The state should stay out of the economy and The government should take measures to reduce income disparities. Regarding the cultural dimension, the following two indicators are included Immigrants should be obliged to adapt to German culture and Energy supply should also be secured through nuclear power. The latter aspect has regained relevance in Germany due to the Ukraine war and has once again become structuring for the German party system with a view to impending energy shortages (Masch et al. Citation2023).

We also include a number of other control variables. We control for the age of the respondents, their sex ((1) female and (0) male) and their school-leaving qualification. In order to control for the East–West cleavage in Germany, we control for the respondents’ place of residence which is divided into Eastern Germany (1) and Western Germany (0). Moreover, we control for subjective class affiliation ((1) lower and working class, (2) lower middle class, (3) middle class and (4) upper middle class and upper class). To control for the political ideology of the respondents, we use their self-placement on a scale ranging from (1) left to (11) right.

Method

We explore the question of how foreign policy attitudes influence voting intention using logistic regressions, from which we calculate average marginal effects models. Furthermore, we explain the propensity to vote for a potential Wagenknecht party using linear regression models.

Voting Intention in Germany and Attitudes towards the Russian Invasion

Descriptives

50.3 percent of respondents clearly reject the statement that NATO provoked a Russian invasion of Ukraine. 24.4 percent agree with this statement, while another 25.2 percent are indifferent. Overall, the respondents in Germany perceive Ukraine as a victim of Russian aggression (see Online Appendix Figure A1). However, this does not mean that an equally clear attitude regarding the cessation of arms deliveries to Ukraine can be ascertained. Only 36.7 percent of respondents are in favour of arms deliveries. 22.6 percent are indifferent, while more than 40 percent of the respondents favour suspending arms deliveries to Ukraine (see Online Appendix Figure A2).Footnote4 Nevertheless, the correlation between the two variables is very strong and highly pronounced at r = 0.63***. Those who reject the belief that NATO provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are also more likely to oppose the suspension of arms deliveries to Ukraine.

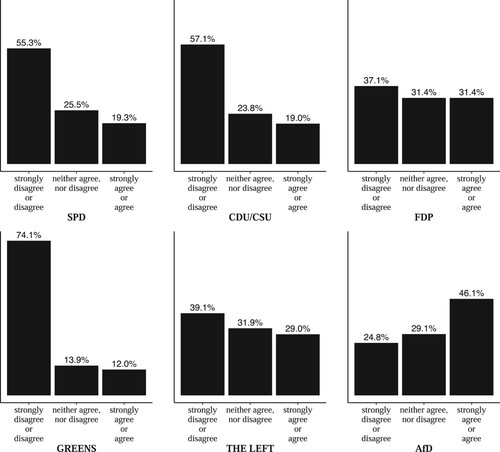

Regarding the question of whether NATO provoked the Russian invasion of Ukraine, four distribution patterns can be observed concerning the attitudes within the German electorates. The strongest rejection of this assumption is found among supporters of the Greens (N = 171). Over 74 percent clearly reject the statement. Among supporters of CDU/CSU (N = 205), the rejection is over 57 percent, and for the SPD (N = 177), slightly over 55 percent hold a rejecting stance. The third group consists of voters from the FDP (N = 74) and the Left Party (N = 75). In the case of the FDP, just over 37 percent reject the statement, and for the Left Party, slightly more than 38 percent reject it; however, over 31 percent of FDP supporters and just under 30 percent of Left supporters agree with the statement. Among AfD supporters (N = 179), there is a predominant agreement of over 46 percent. Only just under a quarter of AfD supporters do not agree with the ascribed responsibility (see ).

Figure 1. Attitude towards the statement that NATO provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Note: Weighted distribution of voters’ attitudes. For a more accessible presentation of the descriptive results, we have collapsed the top two categories (support) and the bottom two categories (opposition). Source: GLES (Citation2023).

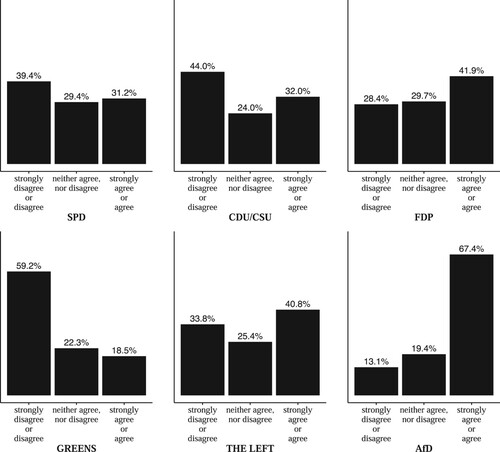

Clearer shifts emerge when considering whether weapons supply to Ukraine should be completely halted, with approval of the statement being higher across all supporter groups compared to the NATO question. Nevertheless, the groups remain similar in the fundamental distribution logic. Among Green supporters, 59 percent oppose ending weapons supply, while 44 percent of CDU supporters and just under 40 percent of SPD supporters hold corresponding positions. Regarding the FDP and the Left Party, supporters in favour now outnumber those in opposition. Approximately 42 percent of FDP and over 40 percent of Left Party supporters favour ending weapons supply to Ukraine. However, these figures are much lower than the almost 68 percent of all AfD supporters advocating for a halt to weapons supplies (see ).Footnote5

Figure 2. Attitude towards the statement that Germany should completely stop supplying weapons to Ukraine.

Note: Weighted distribution of voters’ attitudes. For a more accessible presentation of the descriptive results, we have collapsed the top two categories (support) and the bottom two categories (opposition). Source: GLES (Citation2023).

Foreign Policy Attitudes Association with Vote Intention

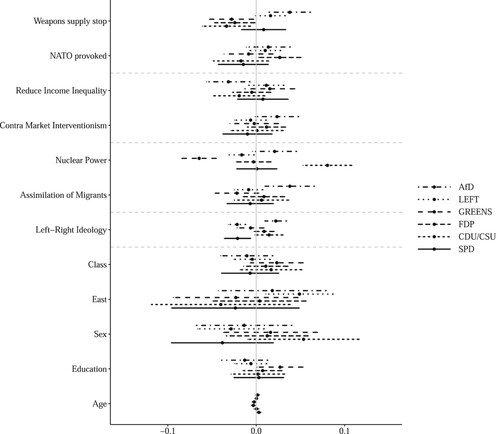

While the descriptive results reveal overarching trends among various supporter groups, intriguing effects concerning the voting intentions for the described German parties can also be identified based on these attitudes. In the case of the SPD, no significant effect was observed regarding individual foreign policy preferences and their voting intentions meaning that the intention to vote for the SPD cannot be elucidated by the issue-related stances of their supporters. A different picture emerges when we compare this with the findings regarding the CDU/CSU. Although attitudes towards NATO are not significantly related to the intention to vote for the Christian democrats, this is not the case regarding the position on arms supplies. When a weapons supply stop to Ukraine is rejected, the probability of intending to vote for CDU/CSU increases by an average of 3.42 percent (p < 0.05). Only the effect of supporting nuclear power for energy production is stronger here - the corresponding effect is an average 8.84 percent increase in the probability of voting (p < 0.001). The findings seem understandable since the CDU/CSU has recently spoken out in favour of both longer lifetimes for nuclear power and arms deliveries to Ukraine as a consequence of the Russian aggression.

When examining vote intention towards the liberal FDP, we find two contrasting effects, different to our anticipation. While the FDPs representatives have been positive of NATO after the Russian invasion in 2022, leading FDP politician Kubicki has been more critical of NATO in the past. It therefore does not seem entirely incomprehensible that a vote intention in favour of the FDP increases by an average of 2.6 percent (p < 0.05) when NATO is seen as responsible for the Russian invasion. At the same time, leading FDP politicians have also expressed their support for Ukraine and supported the delivery of weapons. Accordingly, the rejection of stopping arms deliveries to Ukraine leads to an average 2.38 percent (p < 0.05) higher probability of voting for the FDP. In summary, this results in an ambiguous profile for the FDP within its own supporters, which can be understood as a reflection of a division between the main leadership and faction around Kubicki. While the FDP electorate may be more likely to support sending weapons to Ukraine, the FDP electorate also does not solely blame Russia for the invasion. The findings for the FDP electorate showcase that the two items, NATO responsibility and weapon supply, test different dynamics.

After the Russian invasion, the German Greens proved to be allies of Ukrainian interests. It is, therefore, hardly surprising that in addition to traditional issues such as the rejection of nuclear power and a liberal immigration policy, support for further arms deliveries also significantly influences the Greens vote intention. The intention to vote for the Greens increases by an average of 2.88 percent if a weapons supply stop is rejected (p < 0.05). While attitudes towards NATO are not significantly related to voting intention towards the AfD, demand for a weapons supply stop shows a higher probability of voting intention by an average of 4.89 percent (p < 0.001).

For the Left Party, neither attitudes towards NATO nor weapons supplies are significantly correlated to the vote intention (see ). This is relatively unsurprising, given internal disagreements lead to one of its prominent representatives, Sahra Wagenknecht, launching a new party. The new party, BSW - Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht was launched in early 2024. Disagreements also included the reaction towards the invasion, as Wagenknecht, rejects blaming Russia for the conflict in Ukraine (Wondreys Citation2023; Arzheimer Citation2023; Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023) and has been a supporter of peace negotiations - at the expense of Ukraine and the loss of territorial integrity (Arzheimer Citation2023; Hartleb and Schiebel Citation2023). Preliminary analyses suggest that the establishment of such a left-authoritarian party would be able to fill a political space that has so far been unoccupied in German political party space (Hillen and Steiner Citation2020; Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek Citation2023). When examining the findings for left-wing economic parties, significant effects are only evident in the case of the Greens whose stance is explicitly pro-NATO and supportive of weapons deliveries. This raises the question of whether Wagenknecht could successfully incorporate peace policy, NATO-opposed, and Russia-friendly positions into her own left-wing economic agenda.

Figure 3. Effects on Vote Intention – Average Marginal Effects.

Note: Average marginal effects (in percentage points) and 95% confidence intervals based on logit coefficients are given. The dependent variable is dichotomously coded into intention to vote for a party (1) and no corresponding intention (0). See Online Appendix Table A2 for further details. Source: Author’s own calculation and presentation, based on GLES (Citation2023).

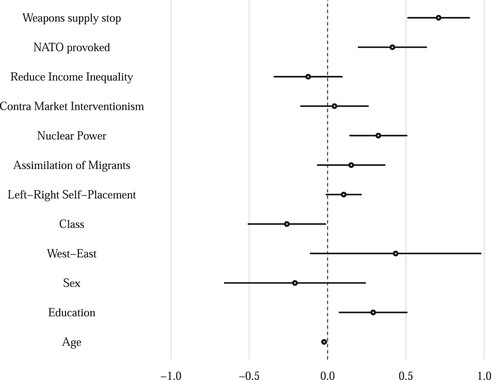

In , we see the results of a linear regression providing evidence that the propensity to vote for a party by Sahra Wagenknecht is significantly higher (p < 0.001) when an individual agrees that NATO provoked the Russian invasion of Ukraine or when they support a weapons supply stop (see Online Appendix Table A3 for further details). It is important to note here that both effects exist simultaneously and while controlling for other important issues that might correlate with voting for a future Wagenknecht party (see Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek Citation2023). While Wagenknecht did launch the party BSW in the beginning of 2024, the survey was fielded in April of 2023. This means that respondents at this point had no knowledge of the BSW, its political profile or structure. While this is an important factor to bear in mind, the BSW is a highly personalised party. We therefore can assume that positions that Wagenknecht has publicly held, are likely replicated in her party – at the very least, this was how it was perceived within the BSW electorate of the 2024 European election (Tagesschau Citation2024).

Figure 4. Explaining Propensity to Vote for the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW).

Note: Linear regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals are given. Source: GLES (Citation2023). N = 696. See Online Appendix Table A3 for further details. Source: Author’s own calculation and presentation.

We observe that both attitudes towards NATO and towards arms deliveries are factors indicating a higher propensity to vote in 2023. In addition to other factors described here, Wagenknecht’s longstanding foreign policy stance, might significantly influence the success of the BSW. However, the extent to which this occurs remains unclear based on the available data and as the BSW continues to develop a clearer profile and manifesto.

Conclusion

This article has asked to what extent the Russian invasion of Ukraine is reflected within recent vote intentions. Using the case of the Federal Republic of Germany, we examined two issues specifically related to this conflict and their effects.

We found that a clear majority of Germans surveyed rejected the statement that NATO had provoked the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Concerning the statement whether arms deliveries to Ukraine should be stopped completely, the opinions were far more differentiated. In particular, AfD supporters clearly state that NATO should be identified as the guilty party and that arms deliveries should be stopped. Voters of the Left Party and FDP take a somewhat undecided role, while supporters of SPD, CDU/CSU and Greens reject the attribution of blame to NATO. It is even more interesting that the position that NATO provoked a Russian invasion was only significantly related to the intention to vote for the FDP. When a stop to supplying weapons to Ukraine is advocated, the probability of intending to vote for the AfD increases. The opposite effect is visible for the Greens, the CDU/CSU and the FDP. Therefore, our hypotheses H1 (AfD), H2 (Greens), and H3 (CDU/CSU) can only be partially confirmed. The contradictory findings regarding the FDP require further analysis. We therefore decide to reject hypothesis H4.

In party competition, socio-economic right-wing parties, advocating for market freedom and competition, show a clear spectrum of both NATO-critical and NATO-supportive positions among their supporters. The same diversity applies to attitudes towards arms deliveries to Ukraine. However, socio-economically left-wing parties, emphasising a strong welfare state, present a less nuanced landscape. The Greens stand out for their clear stance on Ukraine and the transatlantic alliance. The SPD, despite initial hesitation, eventually supported Ukraine, but its position remains somewhat ambiguous, causing complications within the government coalition with the Greens and FDP.

The Left Party’s prolonged internal conflicts have paralysed the party and contributed to the absence of a unified and unambiguous image of a coherent party position. This is particularly related to the former Left Party politician Sahra Wagenknecht, who launched her own party, BSW, in January 2024. Wagner, Wurthmann, and Thomeczek (Citation2023) suggest that the Russian invasion could influence Wagenknecht’s success; in this article, we provide further evidence for their assumption. Wagenknecht’s party, the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, received 6.2% of the vote share in the European election, in part due to their position on the Russian invasion. In the European Parliament manifesto, they openly argue that ‘as a first step, we want the Ukrainian war to be ended as quickly as possible with a ceasefire and the initiation of peace negotiations’ (BSW Citation2024). While there is no explicit mention of NATO, the manifesto clearly argues that sanctions against Russia ought to be stopped, as it harms the economy and does not result in an end to the war. Wagenknecht’s foreign policy positions seem to be compatible for voters across party lines and, based on the analysis at hand, could even contribute to supporting her in future elections. Our Wagenknecht party hypothesis can thus be confirmed (H5).

Three conclusions can be drawn from our findings. Firstly, following Aldrich, Sullivan, and Borgida (Citation1989) we find that foreign policy attitudes can be associated with vote intention for certain parties, both positively and negatively. Secondly, the findings presented show the complexity that can unfold along foreign policy issues - and how differentiated these are perceived by the population and within party supporter groups. Through testing both, NATO attitudes and weapon delivery attitudes, we show the differences in how these two items are perceived by the population and highlight that the foreign policy issue is more complex than a pro-Ukraine or pro-Russia position. Thirdly, when considering future developments in German party competition, foreign policy attitudes may remain influential even once the Russian-Ukrainian war is over. Populist opposition parties such as AfD, the Left Party or BSW are very likely to mobilise on issues such as NATO or the German-Russian relationship.

This article is not without its shortcomings. Firstly, the fundamental issue with this analysis is that it is a cross-sectional analysis. This means that while we can observe interesting patterns of attitudes and vote intention, we do not know how much of an impact a shift in foreign policy attitudes may have on future elections. As the data is from April 2023, it is over two years away from the next general election and therefore cannot serve as a predictor for voting behaviour at the upcoming election. Furthermore, it is important to note that the data, reliant on a quota sample, carries a fundamental disadvantage. While it allows for the emulation of representative parameters through weighting, it excludes the group of older respondents above the age of 69 who are not covered by the online tracking. Consequently, distortions in the attitudes of the population cannot be entirely ruled out. Similarly, support for a Sahra Wagenknecht party might be the consequence of individuals projecting their own preferences onto the party as the survey was conducted prior to its foundation and manifesto publication. Nevertheless, this article contributes a more nuanced perspective that goes beyond descriptive patterns that have been largely observed thus far.

Based on our analysis, one might assume that individuals do indeed consider what foreign policy positions parties and politicians have adopted in the past and, therefore, align their voting intention accordingly. Nevertheless, we have no verified knowledge of what foreign policy positions the respondents assume the parties might have occupied – and there is, to the best of our knowledge, no survey that has collected data in this regard in the past. This would be, however, of great interest as one might calculate spatial proximity on foreign policy issues. One avenue might be analysing long-term changes in foreign policy attitudes, especially from now on and after the war. Further, future research should examine different items on individuals’ perspectives of NATO as this will help us unravel some of the more complicated dynamics of foreign policy attitudes and their relationship with vote intentions.

Supplemental Data and Research Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the Taylor & Francis website, https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2024.2372562.

Online_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (207.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers, whose feedback has enhanced the contribution of our paper. We also thank Luke March and Jakub Wondreys for the opportunity to present an initial idea for this paper at the ECPR General Conference 2023. We found their suggestions, as well as those from the audience, very helpful. Finally, we thank Matthias Fuchs, whose perspective on foreign policy provided a critical view of our paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

L. Constantin Wurthmann

L. Constantin Wurthmann is currently an Interim Professor for Comparative Politics at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. Usually, he is a member of the team at the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES). His research interests lie in the field of electoral, party, and attitude research. In his work, he explores how party systems change and how this is influenced by newly developing party potentials and specific voter groups such as LGBTQ* individuals. His works have been published in various journals, including Electoral Studies, European Political Science Review, Political Research Exchange, Party Politics, and German Politics.

Sarah Wagner

Sarah Wagner is a Lecturer in Quantitative Political Science at Queen’s University Belfast. She is interested in political parties and their strategies - in particular in regard to their policy positions. She researches this in the context of radical left parties and shows that their position on cultural (non-economic) positions can substantially influence their success at the ballot box. Her work has been published in Electoral Studies, Party Politics, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, and Political Studies Review.

Notes

1 In the context of weapon deliveries, a notable paradigm shift occurred prior to February 24th 2022, during the War against ISIS, particularly when Germany provided significant military support to Kurdish forces in Northern Iraq. Germany’s decision to supply anti-tank weapons, assault rifles, and other military equipment directly to Kurdish fighters represented a shift in policy and strategy (Andersson and Gaub Citation2015).

2 While this distinction has been frequently used in political and media discourse, it is worth mentioning that it has been frequently regarded as ‘no useful distinction between these categories: All weapons can be used for attacking and defending’ (Mearsheimer 2015).

3 It should be noted that one can believe NATO expansion is responsible but still support sending weapons to Ukraine.

4 Similar descriptive distributions can also be found in the 2023 ZMSBw public opinion survey (see Graf Citation2024), with agreement to military support of Ukraine at 45%, opposition to support at 30% and the undecided group making up 23%. The survey also examines whether NATOs eastward enlargement contributed to the conflict between the West and Russia with distributions being more equal (34% agree and 33% disagree with 24% being undecided). However, given the high specificity of this question, deviations from the descriptive results presented here are to be expected.

5 If interested in the distribution of the controls used, see Online Appendix Table A1.

References

- Aldrich, John H., Christopher Gelpi, Peter D. Feaver, Jason Reifler, and Kristin T. Sharp. 2006. “Foreign Policy and the Electoral Connection.” Annual Review of Political Science 9: 477–502.

- Aldrich, John H., John L. Sullivan, and Eugene Borgida. 1989. “Foreign Affairs and Issue Voting: Do Presidential Candidates ‘Waltz Before a Blind Audience?’”.” The American Political Science Review 83 (1): 123–141.

- Amann, Melanie, and Martin Knobbe. 2022. “Es darf keinen Atomkrieg geben”. Der Spiegel, April 22, 2022. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/olaf-scholz-und-der-ukraine-krieg-interview-es-darf-keinen-atomkrieg-geben-a-ae2acfbf-8125-4bf5-a273-fbcd0bd8791c.

- Andersson, Jan, and Florence Gaub. 2015. “Adding fuel to the fire? Arming the Kurds.” European Union Institute for Security Studies. Accessed March, 6, 2022.

- Angelucci, Davide, and Pierangelo Isernia. 2020. “Politicization and Security Policy: Parties, Voters and the European Commonsecurity and Defense Policy.” European Union Politics 21 (1): 64–86.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2023. “To Russia with Love? German Populist Actors’ Positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin.” In The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe, edited by Gilles Ivaldi, and Emilia Zankina, 157–167. Brussels, Belgium: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS).

- Blumenau, Bernhard. 2022. “Breaking with Convention? Zeitenwende and the Traditional Pillars of German Foreign Policy.” International Affairs 98 (6): 1895–1913.

- BSW. 2024. Unsere Ziele im Europäischen Parlament. https://bsw-vg.eu/ (accessed on 7th of May 2024).

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Campbell, Angus, Gerald Gurin, and Warren E. Miller. 1954. The Voter Decides. New York, USA: Row, Peterson, and Company.

- Chryssogelos, Angelos. 2022. Party Systems and Foreign Policy Change in Liberal Democracies: Cleavages, Ideas, Competition. London, UK: Routledge.

- Deutsche Welle. 2022. “Doch deutsche Waffen für die Ukraine?.” Deutsche Welle, February 24, 2022. https://www.dw.com/de/doch-deutsche-waffen-für-die-ukraine/a-60904039.

- Deutscher Bundestag. 2022. “Stenografischer Bericht.” 19. Sitzung. Berlin, Sonntag, den 27. Februar 2022. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/20/20019.pdf#P.1350.

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, Matthias. 2014. “Why Parties Politicise International Institutions: On Globalisation Backlash and Authority Contestation.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (6): 1275–1312.

- Fröhlich, Manuel. 2023. “‘Wenn möglich bitte wenden?’ Die deutsche Außenpolitik und die Navigation der Zeitenwende.” Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 33 (1): 81–92.

- Gavras, Konstantin, Thomas J. Scotto, Jason Reifler, Stephanie Hofmann, Catarina Thomson, Matthias Mader, and Harald Schoen. 2020. “NATO and CSDP: party and public positioning in Germany and France.” NDC Policy Brief, 11-20.

- GLES. 2023. GLES Tracking April 2023, T54. GESIS, Cologne. ZA7712 Data file Version 1.0.0. doi:10.4232/1.14145.

- Graf, Timo. 2024. “Was bleibt von der Zeitenwende in den Köpfen?” https://zms.bundeswehr.de/de/aktuelles/zmsbw-kanal-aktuelles-meldungen/bevoelkerunsgbefragung-zeitenwende-in-den-koepfen-5730686 (accessed on 13th of June 2024).

- Graf, Timo, Markus Steinbrecher, and Heiko Biehl. 2024. “From Reluctance to Reassurance: Explaining the Shift in the Germans’ NATO Alliance Solidarity Following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Contemporary Security Policy 45 (2): 298–330.

- Hartleb, Florian, and Christoph Schiebel. 2023. “Promoting Peace to End Russia’s War Against Ukraine: An Unholy Alliance Between the Far Right and Far Left in Germany?” In Producing Cultural Change in Political Communities: “the Impact of Populism and Extremism on the International Security Environment”, edited by Holger Mölder, Camelia F. Voinea, and Vladimir Sazonov, 197–215. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Hillen, Sven, and Nils D. Steiner. 2020. “The Consequences of Supply Gaps in two-Dimensional Policy Spaces for Voter Turnout and Political Support: The Case of Economically Left-Wing and Culturally Right-Wing Citizens in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (2): 331–353.

- Hofmann, Stephanie C., and Benjamin Martill. 2021. “The Party Scene: New Directions for Political Party Research in Foreign Policy Analysis.” International Affairs 97 (2): 305–322.

- Holsti, Ole R. 1992. “Public Opinion and Foreign Policy: Challenges to the Almond-Lippmann Consensus Mershon.” International Studies Quarterly 36 (4): 439–466.

- Hough, Dan, and Dan Keith. 2019. “The German Left Party.” In The Populist Radical Left in Europe, edited by Giorgos Katsambekis, and Alexandros Kioupkiolis, 129–144. London, UK: Routledge.

- Johansson, Bengt, David Nicolas Hopmann, and Adam Shehata. 2021. “When the Rally-Around-the-Flag Effect Disappears, or: When the COVID-19 Pandemic Becomes ‘Normalized.’.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 31 (sup1): 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924742.

- Kleuters, Joost. 2012. Reunification in West German Party Politics from Westbindung to Ostpolitik. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien.

- Kucharczyk, Jacek, and Agnieszka Lada-Konefal. 2022. “Mit einer Stimme: Deutsche und Polen über den russischen Angriff auf die Ukraine: Deutsch-polnisches Barometer 2022 Sonderausgabe.” Deutsches Polen-Institut. https://www.deutsches-polen-institut. de/assets/downloads/einzelveroeffentlichungen/Deutsch-Polnisches-Barometer2022.-Sonderausgabe.pdf.

- Lippmann, Walter. 1955. Essays in the Public Philosophy. Boston, USA: Little, Brown and Company.

- Mader, Matthias. 2022. “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: A Watershed for European Public Opinion?” Mershon center for international security studies conference paper series, U.S. and NATO relations with Russia and security in Europe conference.

- Mader, Matthias, and Harald Schoen. 2023. “No Zeitenwende (yet): Early Assessment of German Public Opinion Toward Foreign and Defense Policy After Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 64: 525–547.

- Masch, Lena, Ronja Demel, David Schieferdecker, Hanna Schwander, Swen Hutter, and Jule Specht. 2023. “Shift in Public Opinion Formations on Defense, Energy, and Migration: The Case of Russia’s War Against Ukraine.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 35 (4): edad038.

- Mello, Patrick A. 2024. “Zeitenwende: German Foreign Policy Change in the Wake of Russia’s War Against Ukraine.” Politics and Governance 12.

- Metzger, Nils, and Julia Klaus. 2022. “Wann ist ein Panzer ein Panzer?.” ZDF, June 22, 2022. https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/lambrecht-panzer-definition-gepard-bundestag-ukraine-krieg-100.html.

- Milner, Helen V., and Dustin Tingley. 2015. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press.

- Mueller, John. E. 1970. “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64 (1): 18–34.

- Oktay, Sibel. 2018. “Clarity of Responsibility and Foreign Policy Performance Voting.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (3): 587–614.

- Pickel, Susanne, and Gert Pickel. 2023. “The Wall in the Mind–Revisited Stable Differences in the Political Cultures of Western and Eastern Germany.” German Politics 32 (1): 20–42.

- Pulzer, Peter. 2003. “The Devil They Know: The German Federal Election of 2002.” West European Politics 26 (2): 153–164.

- Rattinger, Hans. 1990a. “Domestic and Foreign Policy Issues in the 1988 Presidential Election.” European Journal of Political Research 18 (6): 623–643.

- Rattinger, Hans. 1990b. “Einstellungen zur Sicherheitspolitik in der Bundesrepublik und in den Vereinigten Staaten: Ein Vergleich von Befunden und Strukturen in den späten achtziger Jahren.” In Wahlen und Wähler: Analysen aus Anlaß der Bundestagswahl 1987, edited by Max Kaase, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 377–418. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien.

- Riexinger, Bernd. 2023. “LINKE Antworten auf den Ukrainekrieg.” Links Bewegt, March 22, 2023. https://www.links-bewegt.de/de/article/697.brüche-krisen-und-die-linke.html.

- Schoen, Harald. 2004. “Winning by Priming? Campaign Strategies, Changing Determinants of Voting Intention, and the Outcome of the 2002 German Federal Election.” German Politics & Society 22 (3): 65–82.

- Schult, Christoph, and Severin Weiland. 2022. “50 Jahre meiner politischen Agenda haben sich in Luft aufgelöst.” Der Spiegel, April 09, 2022. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/wolfgang-kubicki-fdp-ueber-russland-wladimir-putin-und-den-krieg-in-der-ukraine-a-77e6084f-0ce5-47ab-9a58-ecf7e572cacf.

- Schulze, Tobias. 2022. “Ampelzank geht weiter.” Die tageszeitung, September 25, 2022. https://taz.de/Waffenlieferungen-an-die-Ukraine/!5869859/.

- Stein, Rachel M. 2015. “War and Revenge: Explaining Conflict Initiation by Democracies.” American Political Science Review 109 (3): 556–573.

- Tagesschau. 2022a. “Strack-Zimmermann kritisiert Kanzleramt.” Tagesschau, December 27, 2022. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/strack-zimmermann-kritik-101.htm.

- Tagesschau. 2022b. “Deutsche Panzer im Ringtausch nach Tschechien.” Tagesschau,October 11, 2022. https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/leopard-panzer-ukraine-101.html.

- Tagesschau. 2023. “Deutschland liefert 14 “Leopard”-Panzer.” Tagesschau, January 25, 2023. https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/ukraine-leopard-panzer-103.html.

- Tagesschau. 2024. “Welche Themen entschieden die Wahl?” Tagesschau, June 12, 2024. https://www.tagesschau.de/wahl/archiv/2024-06-09-EP-DE/umfrage-wahlentscheidend.shtml (accessed on 13th of June 2024).

- Terhalle, Maximilian. 2023. “Zeitenwende ohne Stärke? Strategische Spiegelachsen vitaler deutscher Sicherheitsinteressen: Ostflanke und Ostasien.” In Russlands Angriffskrieg gegen die Ukraine. Zeitenwende für die deutsche Sicherheitspolitik, edited by Stefan Hansen, Olha Husieva, and Kira Frankenthal, 333–356. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Truchlewski, Zbigniew, Ioana-Elena Oana, and Alexandru D. Moise. 2023. “A Missing Link? Maintaining Support for the European Polity After the Russian Invasion of Ukraine.” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (8): 1662–1678.

- Wagner, Aiko, and Werner Krause. 2021. “Putting Electoral Competition Where it Belongs: Comparing Vote-Based Measures of Electoral Competition.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 33 (2): 210–227.

- Wagner, Sarah, L. Constantin Wurthmann, and J. Philipp Thomeczek. 2023. “Bridging Left and Right? How Sahra Wagenknecht Could Change the German Party Landscape.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 64: 621–636.

- Wallet, Norbert. 2015. “Interview mit Wolfgang Kubicki. ‘Gesetze gegen jedermann durchsetzen.’” General-Anzeiger, January 04, 2015. https://ga.de/news/politik/deutschland/gesetze-gegen-jedermann-durchsetzen_aid-42188083.

- Wittkopf, Eugene R. 1990. Faces of Internationalism: Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy. Durham, UK: Duke University Press.

- Wolf, Georg. 2022. “Nach Wagenknecht-Rede zu Russland: Zerreißprobe für die Linke.” BR, September 11, 2022. https://www.br.de/nachrichten/deutschland-welt/nach-wagenknecht-rede-zu-russland-zerreissprobe-fuer-die-linke,TH8LY1Y.

- Wondreys, Jakub. 2023. “Putin’s puppets in the west? The far right’s reaction to the 2022 Russian (re)invasion of Ukraine.” Party Politics.

- Wurthmann, L. Constantin. 2023. “Kooperation oder Abgrenzung? Einstellungen zum oppositionellen Umgang der CDU/CSU mit der Linken und der AfD.” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 54 (1): 69–86.

- Zink, Wolfgang. 2022. “Die Sicherheitslage aus Sicht der Bevölkerung: Ein Stimmungsbarometer.” PricewaterhouseCoopers. https://www.pwc.de/de/branchenund-markte/oeffentlicher-sektor/die-sicherheitslage-aus-sicht-der-bevoelkerung.pdf.