?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Access to Britain’s highly-resourced private schools matters because of concerns surrounding social mobility. Using the UK Family Resources Survey, we document a high and mostly stable income concentration of private school access since 1997. Nevertheless, some low-income participation persists. Bursaries are income-progressive but cannot account for this participation. Housing wealth is, however, found to be greater for private school participants. We estimate that a 10 per cent rise of family income and home value raises private school participation by 0.9 points, respectively. Neither effect changes over time. The income effect, however, falls sharply outside the top income decile.

1. Introduction

This paper studies access to Britain’s private schools over recent decades. This issue’s relevance lies in its potential implications for educational inequality and, hence, social mobility. In Britain, private schoolsFootnote1 propel a narrow sector of the population towards successful careers in elite positions (Elliot Major and Machin Citation2018).

In some countries, private schools have little or no resource advantage over state-run schools – an example is Germany (DESTATIS Citation2016). Moreover, in many countries, private schooling has little effect on student academic outcomes (e.g. Elder and Jepsen Citation2014; Pianta and Ansari Citation2018, for the US; Nghiem et al. Citation2015 for primary schooling in Australia. However, Britain is distinctive: the socio-economic divide between private and state school children is among the highest in the developed world (OECD Citation2012, Table B2.3); and its private schools, funded by exceptionally high fees, have a very substantial resource advantage over state schools (Green and Kynaston Citation2019). Significant effects on educational attainments at both primary and secondary levels have been found over the past 50 years (e.g. Halsey, Heath, and Ridge Citation1980; Feinstein and Symons Citation1999; Dearden, Ferri, and Meghir Citation2002; Sullivan and Heath Citation2003; Malacova Citation2007; Parsons et al. Citation2017; Henderson et al. Citation2020), consistent with the evidence of the effects of large resource gaps and peer effects on academic achievement (e.g. Sacerdote Citation2011).

There are considerable labour market advantages associated with Britain’s private schooling (Macmillan, Tyler, and Vignoles Citation2015; Green, Henseke, and Vignoles Citation2017; Belfield et al. Citation2018). Recruitment to the upper echelons of power in British business, politics, administration and media continues to be tied to private schools (Reeves et al. Citation2017; Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission Citation2019). The labour market premium for private schooling increased for generations growing up in the 1960s to 1980s (Green et al. Citation2012). Considering the persistent ability of private school alumni to access high-ranking universities (Jerrim et al. Citation2016) and that the higher education premium has grown more dispersed (Lindley and McIntosh Citation2015; Lindley and Machin Citation2016), there is little reason to expect a break in the trend. Many private schools have become more internationalist in their orientation, both admitting more international students and channelling more British pupils towards a global upper echelon of universities. Such a global outlook has the potential to open up worldwide job market opportunities with high earnings expectations (e.g. Weenink Citation2008; Kenway and Fahey Citation2014).

Even though only about 9 per cent of adults have ever been to a private school, the British private school sector is, therefore, a significant pathway through which some families obtain long-term advantages for their children. An appreciation of the, possibly changing, extent to which participation in Britain’s private education is unequal and exclusive to those with higher income and wealth should thus provide a highly relevant contribution to the understanding of educational and economic inequality. While high fees make it self-evident that Britain’s private schools are more accessible by high-income families, we know little about the income concentration of private school access, how that concentration might be changing, the extent and distribution of bursary provision, or how family income and wealth may affect access.

This paper contributes to the small literature on private school participation in several ways. First, we document the concentration of private school participation in family income and how it has changed since the 1990s. We find that attendance is highly income-concentrated, but not so much that there are not some in the low-income deciles attending private school. We also find that the concentration ratio is quite stable over time, though there is a modest drop in the last period analysed (2011–2018). Second, we also document that, for many, average private school fees have become unaffordable out of family income; the change is starker for those on lower incomes. Despite the lack of affordability, the presence of low-income families at private schools point to either bursaries or family wealth. Third, therefore, we also document the distribution of bursaries. We find that the distribution of bursaries is overall progressive, their value linked to financial needs, though with no evidence of substantive change; yet most low-income private school families do not receive bursaries.

The low frequency of bursaries and declining affordability suggest an essential role of longer-term financial family resources. In aggregate, the private wealth-income ratio in twenty-first century Britain is substantially higher than in the 1980s and 1990s despite the losses following the 2008 financial crisis (Atkinson Citation2018). Therefore, our fourth contribution is to estimate the marginal effects of family income using a pseudo-panel with cells defined by the region of residence and by grouped income deciles. Our models find a substantive, non-linear income effect. It is substantial for those in the top income decile and smaller for those below. Fifth, we estimate the relationship of housing wealth (a large fraction of total wealth) with private school access among owner-occupier families. We find a significant positive association of home value with private school access, which is, unlike the income effect, similar across the income distribution.

In Section 2 we describe the British system of private schooling and consider potential expectations about trends in the income concentration of participation, the role of family resources in private school choice and the distribution of fee-assistance through bursaries and scholarships. Sections 3 describes our empirical model and the primary data source, the Family Resources Survey. Our findings are presented in Sections 4 and 5. In our conclusion, Section 6, we note the implications of our findings for the schools’ policies on bursaries and for the government’s policies on social mobility.

2. Access to private schooling in Britain

2.1. The British private school sector

One in eleven schools in Britain is private. Notwithstanding some heterogeneity, private schools are generally considered elite institutions, reflecting both the social composition of their pupil intake, their resources and their alumni’s destinations (Maxwell and Aggleton Citation2015; Reeves et al. Citation2017). On average, the fee income from families with children in private day schools exceeds the government expenditure on state schools by a factor of around 2.5 or more, depending on the education stage. When supplemented by private schools’ physical and financial wealth, the per-pupil resource gap becomes at least three (Green and Kynaston Citation2019).

With these resources, British private schools can specialise in small class sizes, with a pupil-teacher ratio of less than half that of state-maintained schools in 2016 (ISC Citation2019, 25). Although there is some heterogeneity across private schools, the private-state resource gap is typically much higher than in many other countries, though data are scarce. In Germany, for example, where schools have a legal obligation to accommodate families regardless of income, there is a financial resource gap of −5.3 per cent at upper-secondary level (DESTATIS Citation2016). In Australia, the resource advantage is 30 per cent for non-sectarian private schools and −5 per cent for private religious schools (ACARA Citation2019). However, there is considerable fee variation linked to their pupils’ social background (Lye and Hirschberg Citation2017). The United States has in recent years become another exception where non-sectarian private schools, though relatively small in number, deploy a teacher-pupil ratio twice that in public schools. In contrast, Catholic private schools have a slight resource advantage (Broughman, Kincel, and Peterson Citation2019).

Private schools are managed and governed autonomously. Three-quarters of them are charities, which qualifies them for a small amount of public subsidy through tax relief. Since the start of the 1980s, private schools’ resources have transformed. With the cessation of the Assisted Places Scheme that ran from 1981 till 1997 (Whitty et al., Citation1998), neither schools nor potential pupils receive direct public subsidies except for small government programmes targeted at vulnerable children in foster care or those qualifying for the UK’s Music & Dance Scheme in specialist schools.

There are notable regional variations in the availability of private schools. For example, in England’s North East, there were 1.2 private schools per 10,000 pupils whereas, in the South East and Greater London, the figures were 3.6 and 3.8 private schools, respectively (DfE Citation2018). In Wales and Scotland, the figures were 1.5 and 1.4 private schools per 10,000 pupils (Scottish Government Citation2018; Welsh Government Citation2018). Although boarding is an option for the very affluent, region-specific differences in private school provision will likely correlate with participation.

Since the 1980s, the average participation rate in private education has remained stable at around 7 per cent of all school pupils in England (DfE Citation2018). Yet private schools now operate in a different environment from the one they faced in 1980. The external economic and social context has changed substantially through wider access to higher education, rising ‘value’ of education credentials, increased income and wealth inequality, and the emergence of a global elite in a connected world. Approximately 5 per cent of the pupils in Britain’s private schools have non-British parents living abroad (Ryan and Sibieta Citation2011).

2.2. Inequality of access and the determinants of private school participation

Broader economic developments will have affected the extent and distribution of private school participation in contrasting ways since the 1990s: the pull of the earlier discussed potentially increasing benefits; the increasing costs; changes in the provision of means-tested bursaries; changes in income and wealth inequality and in the relationship between family income and wealth – especially given increases in housing wealth and potential wealth transfers within the extended family.

The costs of private schooling have risen considerably. By 2018 the average annual fee before any extras had reached £14,280 for day school and £33,684 for boarding school: in real terms about 60 per cent above the figures for 2000, and three times the 1980 fees. Meanwhile, while income inequality has fallen a little since its peak in 2001Footnote2, the rising wealth-income ratio may have enabled some lower-income families to gain better access to private school than before.

Fee reductions for some students are also potentially important. In Britain, the Assisted Places Scheme– through which the state had funded, at its height in 1998, 8.5 per cent of places at private schools – was ended in 1997 and fully phased out by 2004 (Whitty et al., Citation1998). Spurred by the requirements of the Charities Act 2006, provision of means-tested bursaries expanded. The Independent Schools Council (ISC), the umbrella association of UK private school groups, reported in 2019 that around 28 per cent of pupils received some financial assistance from the schools, up from 19 per cent in 1998. Fee discounts, typically small reductions for siblings or for teachers’ children, were the most common form of financial support (13.2 per cent of students), followed by scholarships (10.8 per cent) and means-tested bursaries (7.8 per cent) (ISC Citation2019). Only one per cent of pupils attended for free. While scholarships are allocated based on academic or cultural/sporting abilities, the award of means-tested bursaries often also entails academic or other ability selection. In total, the bursaries amount to about four per cent of private school turnover.

With these developments pulling in different directions, it is impossible to state whether access to private school has become more or less dependent on family finances over time. Earlier studies of private school choice in Britain have found that current and permanent income enters non-linearly; that other socio-economic background indicators and school location are also important; and that demand is sensitive to price with an estimated elasticity of −0.26 for private school choice at age 7 (Anders et al. Citation2020; Blundell, Dearden, and Sibieta Citation2010; Dearden, Ryan, and Sibieta Citation2011). Furthermore, sociological research has found a mix of motivations and some ambivalence among parents choosing private schooling; emphasising roles both for traditional values and allegiances and for an instrumental approach to choosing private education as a way to gain access to high-ranking universities and rewarding careers (Anders et al. Citation2020; Fox Citation1985; Ball Citation1997; West et al. Citation1998; Foskett and Hemsley-Brown Citation2003).

Educational choices are likely to be taken for a long horizon, given the costs of switching between sectors. In Britain, school choices generally happen at key ages: seven, eleven (sometimes 13) and 16. Given the magnitude of the investments, the choice of school sector will be affected by long-term financial family resources (Carneiro and Ginja Citation2016). Wealth gains may influence school choice either through life-cycle wealth effects or by relaxing credit constraints through additional collateral (Cooper Citation2013). There is a positive association of household net worth with total educational achievement in Britain (McKnight and Karagiannaki Citation2013). Private households hold about two-thirds of their wealth (except pensions) in property (ONS Citation2018). Home value gains may thus have the potential to influence household decisions, including educational choices. In general, housing wealth has been found to correlate with outcomes such as household consumption, individual health, fertility, and labour supply (Dettling and Kearney Citation2014; Fichera and Gathergood Citation2016; Burrows Citation2018; Disney and Gathergood Citation2018). Lovenheim and Reynolds (Citation2013) found that housing wealth gains changed students’ chances to access flagship universities in the US. Although with notable regional heterogeneity, residential real estate prices have more than doubled in real terms since 2000 across England (HM Land Registry Citation2018b). At the same time, equity withdrawal expanded (Reinold Citation2011). Therefore, it appears appropriate to consider the role of family wealth either in property or financial assets in addition to income to study private school access.

In light of the above, our empirical description and analysis address these questions: How has the family income concentration of private school attendance been changing in Britain? Who receives bursaries: how large are they and are they progressive in their distribution? What are the effects of family income? What is the correlation of housing wealth with private school access?

3. Data and variables

3.1. Data

Our primary data comes from the Family Resources Survey (FRS) and the Households Below Average Income (HBAI) programme. The FRS is a series of annual cross-sectional random probability surveys of private households in the UK. Since its launch in 1994, it has collected information on household composition, economic activity, income and broader financial resources from all adults in around 25,000 households (20,000 after 2010) (DWP Citation2018a, Citation2018b). We use data from 1997 onward for families in Great Britain with dependent children aged 5–15 years (the years of compulsory primary and secondary schooling). We further restrict the sample to families with family heads aged 25–64 years to avoid confounding from transitions into and out of the labour market.

FRS queries survey participants "What type of school or college does [name] attend?" From the responses, we derive private school attendance as a dummy variable that distinguishes children in private schools (defined as any school where at least some pupils pay fees) from children in state-maintained schools. Because the focus is on mainstream primary and secondary schools, we remove observations on special schools and on those few who have moved on to non-advanced further education.Footnote3 In all, the analytical sample includes information about 157,618 children in 99,118 families.

3.2. Measuring income and home value

FRS includes detailed questions about families’ current income from all sources. As part of HBAI, the Department for Work and Pensions re-weights and imputes very high incomes to compensate for under-representation and under-reporting in the raw data at the top of the income distributions. This is unique among income surveys. Although not without issues, the procedure goes some way towards reconciling the survey data with data from income tax records (Burkhauser et al. Citation2018). All monetary variables are in 2018/19 prices. Under the assumption that all family members benefit from total disposable income, we equivalise total net income by dividing it by the square root of family size, i.e. the combined number of adults and dependent children in the family.

FRS asks a set of questions about households’ housing tenure, the type of accommodation (detached, semi-detached, terraced, flat, others), the number of bedrooms, the council tax band, and, for mortgaged home-owners (86% of all owner-occupiers in the survey), the purchase price and the year of purchase. However, the survey does not collect information on the current value of the property. Thus, to examine the role of housing wealth changes for private school access, we treat it as a missing data problem and impute plausible values of the current home value for all owner-occupier families from the information in the survey using a multiple imputation approach. Multiple imputations can lead to consistent and asymptotically efficient estimates whilst allowing for greater flexibility than a system of equations (Allison Citation2002).

In the imputation stage, we estimate a log-linear regression model of the of the initial purchase price of the accommodation in 2018/19 prices on the number of bedrooms, type of accommodation, council tax band, and purchase year in addition to the covariates of the analytical model in the sample of mortgagors with children aged 5–15 years over the survey waves 1997/98–2018/19. Year of purchase enters as a linear and quadratic time trend which can vary by family income rank and region. The estimated coefficients together with random draws form the residual distribution are used to predict multiple plausible values of the log property value at 2018/19 prices for each owner-occupier household with children aged 5–15 years in FRS from 1997 onward. Table A1 in the appendix summarises the imputation model. Because current home value is missing for all but 2.2 per cent of owner-occupiers who purchased their accommodation in the survey year, we generate 50 imputation, which is a relatively large number of imputations (Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath Citation2007). Averaged over the different imputations by survey year, government region, and property type, there is a strong correlation (r = 0.87) of the imputed home value with average property prices published by the HM Land Registry (HM Land Registry Citation2018a). See table A2 in the appendix for details. In subsequent analyses, estimation results from the 50 imputations are pooled to obtain consistent home value effects with appropriate standard errors.

Furthermore, FRS also includes information on financial awards (scholarship, bursary, grant or similar award) for education for children in secondary education or above. From this information, we construct an indicator variable whether a child in lower secondary education receives any bursary/ scholarship and if so, the total annual value deflated to 2018/19 prices.

Besides these variables, we also use information about the region of residence, the number of adults in the family, the age of the family head, housing tenure, the parents’ socio-economic class and their age when leaving full-time education in the imputation and analytical model.

4. Analytical model

To test the relationship of financial family resources with private school access, we draw on a set of common assumptions which imply a structural relationship between both (e.g. Acemoglu and Pischke Citation2001; Solon Citation2004).

Parents care about their children’s future life chances and decide whether to enrol their children at a private school. The decision is assumed to be non-separable over time, reflecting typical school choices at the beginning of primary and secondary school, respectively. Because credit markets are imperfect, parents cannot borrow against their children’s future human capital returns. Since there is no public loan scheme that could help to secure credit, private school access will depend on families’ access to financial resources through income and capital markets. For wealthy, high-income families who are not credit constrained in their decision to send their children to private school, additional financial resources may not affect the private education decision; except if private education has characteristics of a consumption good. However, for families who are credit constrained a rise in lifetime income or wealth is predicted to increase the likelihood of investing in private education. Moreover, we assume a third group of lower-income parents who face an affordability constraint, namely that lifetime consumption is constrained to be above an absolute minimum. For all in this group, the decision is the corner solution of non-participation; even in response to marginal increases in income or wealth. Additional wealth can raise private school access by relaxing credit constraints through a collateral effect or by easing the lifetime budget constraints.

Our econometric model builds on these assumptions:

(1)

(1) Demand for private school education for children of family i,

, is a function of the natural log of permanent family resources,

(income or home value), a set of control variables with an influence on financial family resources and private school access, region-by-year effects,

, and a family-specific taste shifter for private education,

, which can include expected returns from private school education. The region-by-year effects control for common factors that influence all families within regions and years and will be modelled by region-specific linear time trends. The effect of financial family resources on private school access is given by

. The term

is unobserved and possibly correlated with financial family resources

and school choice. Thus, a cross-sectional analysis will potentially lead to biased estimates.

Moreover, while private school choice will depend on longer-term resources such as permanent income, survey data measures current income. The gap between measured current and family permanent income can be either transitory shocks to family income or measurement error. If ignored, this gap will attenuate the estimated income effect.

To solve both issues, we construct cohorts that we track through repeated cross-sections to estimate a fixed-effects model (Deaton Citation1985). By aggregating the family decision to the cohort level, we derive the following model:

(2)

(2) where

is the proportion of privately educated children for all

children in family cohort

at time

. Similarly,

are the average permanent family resources of cohort

at time

, respectively. Because region and period effects are assumed to be the same for all cohorts who live in region

at time

,

remains unchanged.

Since the families who form the cohorts in the sample will differ for each year, is time-variant. Following the literature around pseudo-panels, we can treat

as an unknown fixed parameter with

if sample sizes for each cohort are sufficiently large (Deaton Citation1985; Verbeek Citation2008).

Thus, the pseudo-panel allows assessing the effect of family financial resources for private school access whilst holding unobserved heterogeneity constant. Similarly, in a pseudo-panel with sufficiently large cohorts, the average measurement error in family resources should approach zero and eliminate classic attenuation bias from switching to a fixed effect strategy (Antman and McKenzie Citation2007). For income, is, therefore, closer to the concept of permanent income,

will pick up common trends that affect all families within a region. However, if measurement error occurs at the cohort level, the resulting pseudo-panel estimates may remain biased. Therefore in robustness analyses, we use an alternative cohort definition.

Families are grouped into mutually exclusive cohorts, c, based on family income decile and region of residence. There is a trade-off between cohort size and the number of observations in the panel. We distinguish between families with incomes in the tenth decile, in the seventh to the ninth decile, in the fourth to the sixth decile, and families with incomes at or below the third decile across eight British regions (North East and Yorkshire, North-West, the Midlands, East of England, Greater London, South East, South West, and the combined devolved nations of Scotland and Wales). Income deciles were calculated for each survey sample of all non-pensioner families with children in the age bracket 5–15 years in Great Britain. The 32 family cohorts are tracked over the 22 cross-sections of the FRS 1997–2018. Table A3 in the online appendix gives mean cohort sizes. Alternatively, in robustness analyses, we also look at cohorts-based on region and socio-economic class instead of income rank.

We arrive at the following baseline estimation model:

(3)

(3) The model identifies family resource effects,

for income and

for home value, on school access through variations in

conditional on income rank, region and region-period effects. The family income effect,

, is identified from differential income growth over the income distribution within regions. Likewise, the home value effect

is identified from the differential growth of home values across family income ranks within regions. As in Acemoglu and Pischke (Citation2001), families’ rank in the income distribution is thought to control for their unobservable characteristics. Because private school fees are high and credit markets are imperfect, we will also test if

or

differ across grouped income deciles.

Like with any other method, there are some caveats. First, the fixed effects estimator can be imprecise without enough time variation in the dependent and independent variables. Although there is within variation in cell-average income, home values, and private school participation, it is conceivable that with finite samples, some cohorts contribute little information to the parameter estimates. To assess the importance of sources of variation, we also estimate more restrictive models with and pooled period effects

Second, while the fixed effects estimator conditions out time-invariant unobserved characteristics, omitted time-variant factors might lead to biased estimates. For example, the analysis of home values on private school participation is limited to the self-selected group of home-owners. If the percentage of home-owning families with children remained the same within cohorts, the fixed effects would condition out the unknown selection mechanism. However, homeownership has started to slip after 2007 from 68 per cent to 57 per cent of families in 2018, which suggests possible changes in the selection mechanism. Ideally, we would instrument for self-selection. In the absence of a convincingly exogenous time-varying instrument, the set of time-variant control variables,

, can account for some of the changes. But even if the parameter estimate for

is biased upward, it can still document how changing access to permanent private financial resources may facilitate private school access.

5. Documenting the income concentration of private school participation and bursary provision

The main aim of this section is to document, for the first time, the extent to which private school participation is family income concentrated, and whether this concentration is changing. In addition, we describe the extent of bursary provision and its correlates; if large enough and income-progressive, bursaries might be expected to modify the link between family resources and private school participation.

5.1. Income concentration

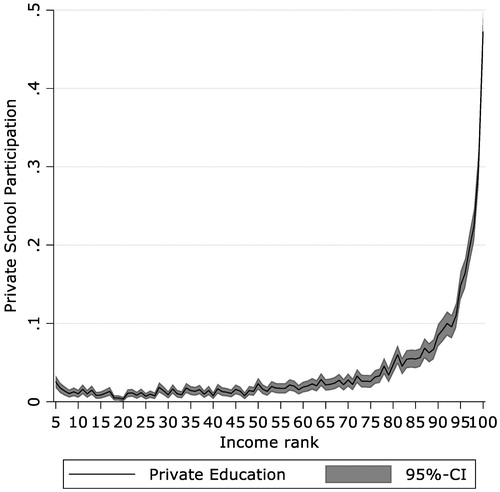

plots participation in private schooling after 1997 against the percentile rank of net equivalised weekly family income for families with children in the 5–15 age range. It shows the extent to which participation is especially skewed at the very top of the income distribution. At the 100th percentile, about half of the children go to private school. At the 95th percentile, however, this proportion is much lower, with only 15 per cent of children in the private sector. While still much greater than the average, it is striking that only a minority of the affluent families in the top 5 per cent are paying for private education.Footnote4

Figure 1. Income concentration of private school participation, 1997–2018. Note: Participation of 5-15-year-olds in private schools in Great Britain by equivalised net family income percentile rank across all non-pensioner households with children aged 5–15 years. Equivalised using the square root of family size. The chart is restricted to families with income at or above the 5th percentile. Target: Families with 5-15-year-old children in Great Britain. Source: HBAI, 2019. FRS 1997/98-2018/19.

also shows a non-zero – albeit very low – private-school participation among low- or middle-income families, for whom full fees would be difficult or impossible to cover out of current income alone.

A key question for policy discourse is whether access to private school has been widening. summarises the income concentration of private school participation over the periods 1997–2003, 2004–2010 and 2011–2018. The top panel reports the participation rate in private education across the income distribution. Consistent with , around one in five children in the top-income decile went to a private school. This proportion and the overall participation rates have remained remarkably stable since 1997. Only the bottom third of the income distribution increased their participation slightly from 1.1 per cent to 2.1 per cent over the study period. Despite this improvement, children from top-decile families remained more than ten times more likely to access private education than those with family incomes below the 4th decile in 2018.

Table 1. Private school participation across the net income distribution of families with children at private school and concentration index, 1997–2018

The bottom panel gives the income concentration index of private school attendance. This index encapsulates the inequality of private school uptake over the whole distribution.Footnote5 Index values can range from −1 (all private school concentrated among the poorest) to +1 (all concentrated among the richest). A value of 0 would indicate the absence of income inequalities in private school choice. The estimates confirm the substantial pro-rich income concentration of private school participation. This income concentration remained stable until the early 2010s then shows a statistically significant drop in the latest period.

The comparative stability in both the rate and the distribution of private school participation contrasts with trends in the ‘affordability’ of private education out of family income. The first panel of shows the rises of incomes between 1997 and 2018, while the second panel shows the rises in home value, at each income decile. Overall, income grew at about two per cent per year. Within income groups, family income rose fastest at the top and the bottom of the income distribution. Home value increased substantially more than family incomes. Average home value expanded 2.7-fold from £133,200 in 1997 to £366,100 in 2018, an increase of about eight per cent per year. Top-income families saw the largest absolute rise in projected home value, but the relative gains were larger for the lower 60 per cent of the family income distribution. Given this strong growth, housing wealth gains may have contributed to family resources for private education among home-owners.

Table 2. Family financial resources and the relative costs of private education relative to school fees, 1997–2018.

The third panel then shows the substantively declining affordability of school fees relative to net family income: from 18 per cent to 26 per cent at the top decile, and from 106 per cent to 133 per cent for those in the bottom third. Indeed, by 2018, only those in the top decile could send children to private school without spending more than half their income per equivalised family member. The last panel shows, however, that affordability in relation to home value, for owner-occupiers, improved significantly.

If home value were associated with private school access, we would expect lower-income families with privately educated children to own relatively more valuable property. breaks down the ratio of imputed home value over annual equivalised net family income by income decile for children in the private sector and in state schools. As expected, the figures show a substantially higher home value-to-income ratio for children in the private school sector. The private-state gap is larger for families at the bottom of the income distribution; which further indicates that families with children at private schools may draw on other financial resources than income.

Table 3. Ratio of home value to annual equivalised net income by children's school type in Britain, 1997–2018.

5.2. Bursaries and scholarships

Bursaries or scholarships may have offset some of the fee rises. About 4 per cent of school turnover is spent overall on bursaries, while 1 per cent of pupils receive full bursaries and go free (e.g. ISC Citation2019). We know, however, little about the distribution of financial support among private school families.

Using the FRS data, shows the proportion of pupils in lower secondary education at private schools who receive bursaries or scholarships and the average awarded amount, split by family income deciles. Throughout the period, around 15 out of every 100 pupils received direct financial support. Significantly, for all those below the top decile, a large majority – up to four out of five children – receive no grants or bursaries. Evidently, this source of funds cannot account for private school participation in this group. The value of financial support was around £4,900 in 2011–2018, little changed from earlier periods and thus accounting for a smaller fraction of the fees: 35 per cent compared with 57 per cent in the first period.

Table 4. Frequencies and value of bursaries/scholarships by income rank for the periods 1997/2003, 2004/2010 and 2011/2018.

Both the allocation and the value of bursaries are, as expected, progressive with respect to parents’ incomes. Nonetheless, even at the 10th decile, around ten per cent of students received financial aid. It is conceivable that these are scholarships, that eligibility is not only tested against income, or that schools are not fully informed about parent’s financial circumstances. Relatively large standard errors make it difficult to draw confident conclusions about the changing degree of progressiveness. Nevertheless, there is a suggestion of a decline in the allocation of bursaries to lower-income families in the middle period (following the cessation of the Assisted Places Scheme) and recovery thereafter, and an increasingly progressive redistribution of the awarded amount to lower-income families.

To analyse who received bursaries or grants we ran separate multivariate analyses (see Table A4 in the online appendix). These show that economic needs matter for the amount awarded and the likelihood of receiving an award. Higher levels of material deprivation, a family head who is not in work, and family income below the top-10 per cent are jointly associated with the likelihood and the annual value of bursaries. Overall, however, the data could not conclusively support claims that the private school sector has widened access for students from low-income families through more generous financial support.

6. Analysis of income and wealth effects

Given that the affordability of fees out of income seems in question for all but the top-income decile, and that bursaries are far too small to explain much of the participation, we now turn to analyse the effects of family resources in the pseudo-panel described above. If private school access remained tied to family financial resources, we would expect to find substantive and time-constant income and home value effects.

6.1. Family income

First, we consider family income effects. reports our main findings. In column (1), we condition only on a linear time trend and a set of socio-demographic control variables. The coefficient of family income is 0.119. However, this estimate does not account for unobserved heterogeneity in the family background across income ranks and regions. In column (2), we thus add panel fixed effects (income rank-region dummies). The estimated income effect drops to 0.088.

Table 5. Income effects on the probability of attending private school from pseudo-panel fixed effects regressions (N = 704), 1997–2018.

Column (3) give the headline estimate based on equation (3). Despite panel fixed effects, control variables and regional time trends, the coefficient of mean log family income remains substantial at 0.088. In other words, a 10 per cent increase in family income is associated with a 0.9 point rise of private school participation. Out of the 19-point participation gap between children from the top decile and the bottom third of the income distribution, income alone can roughly explain 17 points (0.088×LN(1,279/189)).

The descriptive analysis points to largely stable private school access across the income distribution. Column (4) confirms this conclusion. An interaction term between log income and the linear time trend is indistinguishable from zero. The importance of income for private school access has thus changed very little over the last two decades.

Our conceptual framework allows for heterogeneous income effects across the income distribution. Therefore, column (5) estimates income effects for each income bracket. According to the estimates, marginal income effects on private school participation are largest for families in the top decile, where the estimate is 0.135. For families below the top income decile, increases in cell-average income might raise private school access by less. An F-test of equal income effects across the income distribution is rejected (F(3,31) = 4.16, p = 0.014). Overall, there is no evidence of a very affluent group unaffected by income – a finding similar to that of Acemoglu and Pischke (Citation2001) regarding college attendance in the US.

Robustness tests with the pseudo-panel based on socio-economic class instead of income deciles lead to similar conclusions: Income affects private school access, the effect does not change with time, and the point estimates are larger for families at the top of the socio-economic hierarchy. Table A5 in the appendix summarises.

6.2. Housing wealth

We next assess how housing wealth, through home value changes, correlate with private school participation. This is done for owner-occupier families, for whom we imputed current home value deflated to 2018/19 prices as described earlier.

presents estimates for the effect of home value on private school attendance. Column (3) has the key finding from an estimation of equation (3): a 10 per cent appreciation of projected home value for owner-occupier families raised private school participation by 0.9 points; unchanged over the last two decades (column 4). The addition of panel fixed effects and region-period effects slightly increased the estimated coefficient of home value compared with column (1).

Table 6. The effects of home value on the probability of attending private school from pseudo-panel fixed effects regressions, 1997–2018.

Columns (5) estimates separate home value effects by family income band. As before, income deciles are based on the family income distribution across all non-pensioner households with children aged 5–15 in Great Britain in each survey wave. Unlike for family income, the home value effect does not seem to vary across the income distribution.

Although owner-occupiers are a self-selected sub-sample the family income effect on private school access in columns (6) is similar to the estimate in column (3) of . With the addition of home value (column 7), the income effect drops to 0.041, whereas the estimated impact of home value remains substantial at 0.078. It appears that it is the access to permanent wealth, measured by home value, rather than family income that influences private school access among owner-occupier families.

Robustness tests in the alternative pseudo panels confirm the substantial and stable (over time and across income ranks) effect of home value on private school access for owner-occupier (Table A6 in the online appendix).

7. Conclusions

Access to private schools in Britain matters, given the success these schools have in incubating future elites, and the important discourse surrounding social mobility. The fees have risen much more than income, to the extent that the costs for just one child have become more than half of net family income per family member for all but the highest income decile, while the ratio of housing wealth to fees has changed little. The degree of income concentration is high, despite a small fall in the recent period: the income concentration index is 0.48 over 2011–2018. For comparison, access to after school activities such as sports clubs is associated with an income concentration index of 0.08. A small proportion of non-income-rich households do attend private school. Though income progressive and related to need, bursaries and grants are relatively low in value and distributed to only one in five of families outside the top decile; they cannot, therefore, account for more than a minor share of the participation of these non-income-rich families. However, among home-owners, non-rich families with privately educated children have much greater housing wealth than families with children in state schools. Other factors, including parental values and location (distance from good quality state schooling), are also significant determinants of private school choice. Being steady over time, these factors affect choices specifically of those able to afford the fees through either income or wealth (Anders et al. Citation2020).

Following these descriptive findings, we have deployed pseudo-panel methods to estimate that the income effect of a 10 per cent income rise on private school access is a 1.35 percentage point rise in participation for top-income families; and substantially smaller outside the top-income decile. The impact of a 10 per cent rise in housing wealth is for a 0.9 percentage point rise in participation for home-owner families. These effects are substantial.

These results contribute further understanding to debates about Britain’s social mobility trends (Elliot Major and Machin Citation2018). The exclusiveness of access, and its stability over more than two decades of social and economic change, is arguably one reason for the lack of progress over social mobility. The data on bursaries and scholarships have shown how little they can have contributed to any change. Our finding of the stable and robust link between wealth and private schooling underpins other recent research showing how family wealth affects success in adult life (Fagereng, Mogstad, and Rønning Citation2018).

While these results are the first to show the importance of family wealth for access to high-quality education in Britain, they may understate the role of family resources. With our data, we can only examine one, albeit substantial, component of family wealth. Other elements, such as the wealth of family relatives, especially grandparents, are likely to be very important. In the case, resources within the extended family have gained in importance; the here estimated home value effect is expected to proxy some of it.

The estimates imply that the future demand for private schooling will be linked to trends in wealth, as well as the growth of top incomes. The trend will be exacerbated if, in particular, homeownership continues its downward trend while home values continue to rise. In that light, we can conclude that policies to improve social mobility should include the opening up of private school access to wider sections of the population. Externally-imposed reforms such as removing the schools’ charitable status, taxing school fees, focusing ‘contextual admissions’ to universities on school-type, or integrating private schools either partially or entirely with the state sector aim to reduce demand.Footnote6 Internally driven reform focuses mainly on an expansion of means-tested bursaries. Our analysis supports that hitherto bursaries have been income progressive, though too small and scarce to affect overall exclusivity substantially. Means-tested bursaries would need to expand considerably in reach and scale, and the selection criteria should include a strong focus on family wealth, not just income. Whether such internal-driven change is feasible remains uncertain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper ‘private schools’ are fee-paying schools; elsewhere these are also variously termed ‘independent schools’, ‘prep schools’ at primary level, and confusingly ‘public schools’ in the case of the more prestigious secondary schools.

3 While the school type question has remained unchanged throughout, the wording of the response option underwent a minor change, from ‘Any PRIVATE school (prep or secondary)’ before the 2002/2003 wave to ‘Any PRIVATE/Independent school (prep, primary, secondary, City Technology Colleges)’ thereafter. This coincided with a significant increase in the estimated private school participation rate from 3.4 percent in 2001 to 4.4 percent between in 2002. Yet a simple pooled OLS regression of private school participation on income decile interacted with period dummies in the pooled 2001/2002 data revealed no significant period-income rank interaction effects (F=0.71, p=0.70). We judge that this change is unlikely to seriously bias the trend analysis of private school access.

4 The chart is restricted to families with income at or above the 5th percentile. Income data becomes more unreliable at the very bottom of the distribution (Brewer, Etheridge, and O'Dea Citation2017).

5 The concentration index is a bivariate generalisation of the Gini coefficient, and there is a theoretical literature that examines the properties of different definitions and their relation to different concepts of inequality (e.g., O'Donnell et al. Citation2016).

References

- ACARA. 2019. National Report on Schooling in Australia 2017. Sydney. www.acara.edu.au.

- Acemoglu, D., and J.-S. Pischke. 2001. “Changes in the Wage Structure, Family Income, and Children’s Education.” European Economic Review 45 (4–6): 890–904. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00115-5.

- Allison, P. D. 2002. Missing Data. London: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Anders, J., F. Green, M. Henderson, and G. Henseke. 2020. “Determinants of Private School Participation: All About the Money?” British Educational Reserach Journal. doi:10.1002/berj.3608.

- Antman, F., and D. J. McKenzie. 2007. “Earnings Mobility and Measurement Error: A Pseudo-Panel Approach.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 56 (1): 125–161. doi:10.1086/520561

- Atkinson, A. B. 2018. “Wealth and Inheritance in Britain from 1896 to the Present.” The Journal of Economic Inequality 16 (2): 137–169. doi:10.1007/s10888-018-9382-1.

- Ball, S. J. 1997. “On the Cusp: Parents Choosing between State and Private Schools in the UK: Action Within an Economy of Symbolic Goods.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 1 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/1360311970010102

- Belfield, C., J. Britton, F. Buscha, L. Dearden, M. Dickson, L. Van Der Erve, L. Sibieta, A. Vignoles, I. Walker, and Y. Zhu. 2018. The Relative Labour Market Returns to Different Degrees. IfS Research Report: June 2018.

- Blundell, R., L. Dearden, and L. Sibieta. 2010. “The Demand for Private Schooling in England: The Impact of Price and Quality.” IFS Working Papers 10 (21): 1–33. doi:10.1920/wp.ifs.2010.1021

- Brewer, M., B. Etheridge, and C. O'Dea. 2017. “Why are Households That Report the Lowest Incomes So Well-Off?” The Economic Journal 127 (605): F24–F49. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12334

- Broughman, S. P., B. Kincel, and J. Peterson. 2019. Characteristics of Private Schools in the United States: Results From the 2017–18 Private School Universe Survey First Look (NCES 2019-071). US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

- Burkhauser, R. V., N. Hérault, S. P. Jenkins, and R. Wilkins. 2018. “Survey Under-Coverage of Top Incomes and Estimation of Inequality: What is the Role of the UK’s SPI Adjustment?” Fiscal Studies 39 (2): 213–240. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12158

- Burrows, V. 2018. “The Impact of House Prices on Consumption in the UK: A New Perspective.” Economica 85 (337): 92–123. doi:10.1111/ecca.12237

- Carneiro, P., and R. Ginja. 2016. “Partial Insurance and Investments in Children.” The Economic Journal 126 (596): F66–F95. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12421

- Cooper, D. 2013. “House Price Fluctuations: The Role of Housing Wealth as Borrowing Collateral.” Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (4): 1183–1197. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00323

- Dearden, L., J. Ferri, and C. Meghir. 2002. “The Effect of School Quality on Educational Attainment and Wages.” Review of Economics and Statistics 84 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1162/003465302317331883

- Dearden, L., C. Ryan, and L. Sibieta. 2011. “What Determines Private School Choice? A Comparison between the United Kingdom and Australia.” Australian Economic Review 44 (3): 308–320. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8462.2011.00650.x

- Deaton, A. 1985. “Panel Data from Time Series of Cross-Sections.” Journal of Econometrics 30 (1–2): 109–126. North-Holland. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(85)90134-4

- DESTATIS. 2016. Finanzen der Schulen. Schulen in Freier Trägerschaft und Schulen des Gesundheitswesens 2013. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. www.destatis.de.

- Dettling, L. J., and M. S. Kearney. 2014. “House Prices and Birth Rates: The Impact of the Real Estate Market on the Decision to Have A Baby.” Journal of Public Economics 110: 82–100. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.09.009

- DfE. 2018. Schools, Pupils, and Their Characteristics: January 2018. London. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and-their-characteristics-january-2018.

- Disney, R., and J. Gathergood. 2018. “House Prices, Wealth Effects and Labour Supply.” Economica 85 (339): 449–478. doi:10.1111/ecca.12253

- DWP. 2018a. Family Resources Survey: Background Note and Methodology. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/692141/family-resources-survey-2016-17-background-note-and-methodology.pdf.

- DWP. 2018b. Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Quality and Methodology Information Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/691919/households-below-average-income-quality-methodology-2016-2017.pdf.

- Elder, T., and C. Jepsen. 2014. “Are Catholic Primary Schools More Effective Than Public Primary Schools?” Journal of Urban Economics 80: 28–38. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2013.10.001

- Elliot Major, L., and S. Machin. 2018. Social Mobility and its Enemies. London: Penguin Random House.

- Fagereng, A., M. Mogstad, and M. Rønning. 2018. “Why Do Wealthy Parents Have Wealthy Children?’, CESifo Working Paper, No. 6955.

- Feinstein, L., and J. Symons. 1999. “Attainment in Secondary School.” Oxford Economic Papers 51 (2): 300–321. doi:10.1093/oep/51.2.300

- Fichera, E., and J. Gathergood. 2016. “Do Wealth Shocks Affect Health? New Evidence from the Housing Boom.” Health Economics 25 (Suppl 2): 57–69. doi:10.1002/hec.3431

- Foskett, N., and J. Hemsley-Brown. 2003. “Economic Aspirations, Cultural Replication and Social Dilemmas–Interpreting Parental Choice of British Private Schools.” In British Private Schools: Research on Policy and Practice, edited by G. Walford, 188–201. London: Routledge.

- Fox, I. 1985. Private Schools and Public Issues: The Parents’ View. London: Macmillan Press.

- Graham, J. W., A. E. Olchowski, and T. D. Gilreath. 2007. “How Many Imputations are Really Needed? Some Practical Clarifications of Multiple Imputation Theory.” Prevention Science 8 (3): 206–213. doi:10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9

- Green, F., G. Henseke, and A. Vignoles. 2017. “Private Schooling and Labour Market Outcomes.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (1): 7–28. doi:10.1002/berj.3256

- Green, F., and D. Kynaston. 2019. Engines of Privilege: Britain’s Private School Problem. London: Bloomsbury.

- Green, F., S. Machin, R. Murphy, and Y. Zhu. 2012. “The Changing Economic Advantage from Private Schools.” Economica 79 (316): 658–679. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.2011.00908.x

- Halsey, A. H., A. F. Heath, and J. M. Ridge. 1980. Origins and Destinations: Family, Class, and Education in Modern Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Henderson, M., J. Anders, F. Green, and G. Henseke. 2020. “Private Schooling, Subject Choice, Upper Secondary Attainment and Progression to University.” Oxford Review of Education 46: 295–312. doi:10.1080/03054985.2019.1669551

- HM Land Registry. 2018a. “About the UK House Price Index.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/about-the-uk-house-price-index/about-the-uk-house-price-index.

- HM Land Registry. 2018b. UK House Price Index England: May 2018, UK house price index. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-house-price-index-england-may-2018/uk-house-price-index-england-may-2018.

- ISC. 2019. ISC Census and Annual Report 2019. https://www.isc.co.uk/media/5479/isc_census_2019_report.pdf.

- Jerrim, J., P. Parker, A. Chmielewski, and J. Anders. 2016. “Private Schooling, Educational Transitions, and Early Labour Market Outcomes: Evidence from Three Anglophone Countries.” European Sociological Review 32 (2): 280–294. doi:10.1093/esr/jcv098

- Kenway, J., and J. Fahey. 2014. “Staying Ahead of the Game: The Globalising Practices of Elite Schools.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 12 (2): 177–195. doi:10.1080/14767724.2014.890885

- Lindley, J., and S. Machin. 2016. “The Rising Postgraduate Wage Premium.” Economica 83 (330): 281–306. doi:10.1111/ecca.12184

- Lindley, J., and S. McIntosh. 2015. “Growth in Within Graduate Wage Inequality: The Role of Subjects, Cognitive Skill Dispersion and Occupational Concentration.” Labour Economics 37: 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.015

- Lovenheim, M. F., and C. L. Reynolds. 2013. “The Effect of Housing Wealth on College Choice: Evidence From the Housing Boom.” Journal of Human Resources 48 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1353/jhr.2013.0001

- Lye, J., and J. Hirschberg. 2017. “Secondary School Fee Inflation: An Analysis of Private High Schools in Victoria, Australia.” Education Economics 25 (5): 482–500. doi:10.1080/09645292.2017.1295024

- Macmillan, L., C. Tyler, and A. Vignoles. 2015. “Who Gets the Top Jobs? The Role of Family Background and Networks in Recent Graduates’ Access to High-Status Professions.” Journal of Social Policy 44 (3): 487–515. doi:10.1017/S0047279414000634

- Malacova, E. 2007. “Effect of Single-Sex Education on Progress in GCSE.” Oxford Review of Education 33 (2): 233–259. Routledge. doi:10.1080/03054980701324610

- Maxwell, C., and P. Aggleton, eds. 2015. Elite Education: Inernational Perspectives. London: Routledge.

- McKnight, A., and E. Karagiannaki. 2013. “The Wealth Effect: How Parental Wealth and Own Asset-Holdings Predict Future Advantage.” In Wealth in the UK: Distribution, Accumulation, and Policy, 119–146. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199678303.003.0006

- Nghiem, H., H. Nguyen, R. Khanam, and L. Connelly. 2015. “Does School Type Affect Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Development in Children? Evidence from Australian Primary Schools.” Labour Economics 33: 55–65. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.02.009

- O'Donnell, O., S. O'Neill, T. Van Ourti, and B. Walsh. 2016. “Conindex: Estimation of Concentration Indices.” The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 16 (1): 112–138. doi:10.1177/1536867X1601600112

- OECD. 2012. Public and Private Schools: How Management and Funding Relate to Their Socio-Economic Profile. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- ONS. 2018. Wealth in Great Britain Wave 5: 2014 to 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/wealthingreatbritainwave5/2014to2016/previous/v2.

- Parsons, S., F. Green, G. Ploubidis, A. Sullivan, and D. Wiggins. 2017. “The Influence of Private Primary Schooling on Children’s Learning: Evidence From Three Generations of Children Living in the UK.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (5): 823–847. doi:10.1002/berj.3300

- Pianta, R. C., and A. Ansari. 2018. “Does Attendance in Private Schools Predict Student Outcomes at Age 15? Evidence From A Longitudinal Study.” Educational Researcher 47 (7): 419–434. doi:10.3102/0013189X18785632

- Reeves, A., S. Friedman, C. Rahal, and M. Flemmen. 2017. “The Decline and Persistence of the Old Boy: Private Schools and Elite Recruitment 1897 to 2016′.” American Sociological Review 82 (6): 1139–1166. doi:10.1177/0003122417735742

- Reinold, K. 2011. “Housing Equity Withdrawal Since the Financial Crisis.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Q2: 127–133.

- Ryan, C., and L. Sibieta. 2011. “A Comparison of Private Schooling in the United Kingdom and Australia.” Australian Economic Review 44 (3): 295–307. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8462.2011.00651.x

- Sacerdote, B. 2011. “Peer Effects in Education: How Might They Work, How Big are They and How Much Do we Know Thus Far?” In Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by E. Hanushek, S. Machin, and L. Woessmann, vol 3, 249–277. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00004-1

- Scottish Government. 2018. Summary Statistics for Schools in Scotland. https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/School-Education/Summarystatsforschools.

- Solon, G. 2004. “A Model of Intergenerational Mobility Variation Over Time and Place.” In Generational Income Mobility in North America and Europe, edited by M. Corak, 38–47. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sullivan, A., and A. F. Heath. 2003. “Intakes and Examination Results at State and Private Schools.” In British Private Schools: Research on Policy and Practice, edited by G. Walford, 77–104. London: Woburn Press.

- Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission. 2019. Elitist Britain 2019: The Educational Backgrounds of Britain's Leading People. London: Sutton Trust and the Social Mobility Commission. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/elitist-britain-2019.

- Verbeek, M. 2008. “Pseudo-Panels and Repeated Cross-Sections.” In The Econometrics of Panel Data, edited by L. Mátyás, and P. Sevestre, 369–383. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Weenink, D. 2008. “Cosmopolitanism as a Form of Capital: Parents Preparing Their Children for a Globalising World.” Sociology 42 (6): 1089–1106. doi:10.1177/0038038508096935

- Welsh Government. 2018. School Census Results, 2018. Cardiff: Welsh Government. https://gov.wales/schools-census-results-january-2018

- West, A., P. Noden, A. Edge, M. David, and J. Davies. 1998. “Choices and Expectations at Primary and Secondary Stages in the State and Private Sectors.” Educational Studies 24 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1080/0305569980240103

- Whitty, G., S. Power, and T. Edwards. 1998. “The Assisted Places Scheme: Its Impact and Its Role in Privatisation and Marketisation.” Journal of Education Policy 13 (2): 237–250. doi:10.1080/0268093980130205