?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We examine the effects of HIV-infection on school attendance in Zimbabwe using recent nationally representative data of 11,673 children aged 6–18 years. We employ a non-linear multivariate decomposition approach to examine how HIV affects gender gaps in school attendance. We find gaps in school attendance between HIV-positive boys and girls and between HIV-negative and positive girls. About 44% of the attendance gap in both cohorts is attributed to differences in observable characteristics. About 56% of this gap is attributed to differences in the effects of these characteristics. The results indicate that HIV mainly affects girls’ school attendance.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Despite efforts aimed at ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the disease remains a major global public health concern. In 2017, about 940,000 people died of AIDS and about 1.8 million people were newly infected globally (WHO Citation2018). With less than 4% of the world's population, Southern Africa contains nine countries with the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world. Zimbabwe is ranked sixth with a national prevalence rate of 13.3% (UNAIDS 2018). An estimated 1.3 million individuals are currently living with HIV in Zimbabwe, and about 77,000 (6%) are children under 14 years (UNAIDS 2018). HIV is not only a health concern in Zimbabwe, it also has economic consequences. Due to HIV/AIDS-related mortality and morbidity, families, employers, and the country at large lose productive members (Matshe and Pimhidzai Citation2008). The loss of human capital can be traced back to the time an HIV-positive child starts missing school. Examining the extent to which HIV-positive children lag behind in schooling adds to the literature that examines the human capital loss brought about by HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

HIV can affect children's schooling through (i) a child missing school days due to illness- or treatment-related issues (Anabwani, Karugaba, and Gabaitiri Citation2016); (ii) HIV-positive parents not being able to facilitate their children's schooling (Akbulut-Yuksel and Turan Citation2013); and (iii) socio-economic issues related to the disease, given the interplay between HIV and poverty (Lopman et al. Citation2007). These issues can vary by gender. That is, HIV-positive girls may be more likely to drop out of school due to early marriage while boys are more likely to drop out to seek employment (Mpofu and Chihenga Citation2016). In addition, HIV may stigmatize girls more than boys (Chikovore et al. Citation2009). However, there is a dearth of literature that analyzes the direct effects of HIV on intergender and intragender gaps in schooling.

Data that contain biomedical information about HIV test results of children is scant. Hence, most of the studies that examine the effects of HIV on children's educational attainment have focused on orphans (Guo, Li, and Sherr Citation2012; Zinyemba, Pavlova, and Groot Citation2020). Biomedical information on HIV-infection allows distinguishing whether HIV-positive children are different from HIV-negative children. Evaluating these direct effects of HIV infection on educational attainment can highlight the extent to which HIV affects human capital accumulation. This study will use data with biomedical information on HIV of children in Zimbabwe to examine whether there are inter-gender differences (HIV-positive boys vs. HIV-positive girls) and intragender-differences (HIV-negative girls and HIV-positive girls) in how HIV affects school attendance.

Literature review

A small number of studies have examined the direct effects of HIV on children's educational attainment. Anabwani, Karugaba, and Gabaitiri (Citation2016) examined HIV-infected children aged 6–17 years in Botswana and found that about 60% reported having missed at least one day of school in the preceding month. Similarly, Parchure et al. (Citation2016) found that compared to HIV-affected children (e.g. children with HIV-positive parents), HIV-infected children aged 6–16 years in India were seven times more likely to be out of school. Henning et al. (Citation2018) found that children between 10 and 17 years in Rwanda were twice as likely to not be in the correct grade for their age compared to their HIV-negative counterparts. However, for Zimbabwe, the results are mixed. On the one hand, Bandason et al. (Citation2013) found that HIV-infected children aged 11–13 years were more likely to be behind by one or more grades. On the other hand, Pufall et al. (Citation2014) found that HIV was not associated with educational outcomes for children aged 6–17 years in the eastern province of Zimbabwe (Manicaland).

These two studies for Zimbabwe had some shortcomings. First, Bandason et al. (Citation2013) only conducted a bivariate analysis. Conducting a multivariate analysis helps to identify variables that have a statistically significant effect on the outcome (school attendance) after controlling for other determinants. Secondly, Pufall et al. (Citation2014) only focused on one region in Zimbabwe (Manicaland), which leaves out nine other regions, including the three ‘hotspots’ regions that had high mother-to-child transmission rates (McCoy et al. Citation2015) and regions with the highest prevalence rates.Footnote1 Thirdly, none of these studies examined effects of HIV on intragender differences. For example, girls affected by HIV may have poor educational outcomes compared to unaffected girls (Kitara et al. Citation2013).

A recent literature review by Zinyemba, Pavlova, and Groot (Citation2020) showed that the results of studies that examine the relationship between HIV and gender-differences in educational attainment, are mixed. Some authors have found that HIV-affected girls obtain less education compared to HIV-affected boys. For example, Bhargava (Citation2005) studied AIDS orphans in Ethiopia and found that following the death of a mother, girls were less likely to participate in school. Similarly, Delva et al. (Citation2009) examined girls and boys orphaned by AIDS in Guinea and found that boys were more likely to attend school. In a more recent study, Harrison et al. (Citation2017) showed that girls who had a biological parent with HIV or were orphaned by AIDS reported lower grades and less interest in school. Other studies found that HIV-affected boys obtain less education than HIV-affected girls or found no gender differences. For instance, Floyd et al. (Citation2007) found that there was no difference in mean grade average between boys and girls with HIV-positive parents in Malawi. Another study by Kidman et al. (Citation2012) showed that being a maternal orphan has a stronger effect on boys compared to girls. Similarly, Orkin et al. (Citation2014) found that orphaned boys in South Africa reported concentration problems and difficulties with grade progression. The results from these studies confirm that most studies that examine gender-differences in schooling in HIV-affected children focus on orphans. In addition, the results vary by country. One potential reason is that education, gender, and HIV policies differ by country and evolve over time. Hence, the use of country-specific data allows for contextual interpretations that stem from cultural differences (about gender roles) and enables the recommendation of relevant policies.

This paper examines the effects of HIV and gender on educational attainment using a recent nationally representative survey from Zimbabwe. This is the first study to use a nationally representative sample that contains biomedical information on HIV infection of children aged 0–18 years. The study also examines the effects of HIV on inter-gender and intra-gender differences in educational attainment by decomposing gaps in school attendance between various groups of HIV-positive and HIV-negative boys and girls. This is the first study to perform this type of analysis in an HIV context in SSA. Specifically, the contributions of this paper are three-fold. First, we examine whether HIV and/or gender have an effect on school attendance for a nationally representative sample of school-aged children in Zimbabwe. Second, we analyze whether there are (inter and/or intra) gender-differences in how HIV affects school attendance. Third, we examine the factors that contribute to any existing gender gaps in school attendance. Given that young girls in Zimbabwe are more vulnerable to HIV, we expect that girls will be more affected by the disease (Schaefer et al. Citation2017).

The education system of Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country and a former British colony with a population of about 16 million and a GDP of $3281 per capita PPP (World Bank Citation2018). The Education Act (25:04) of Zimbabwe states that children of school-going age have the right to primary education. This Act does not specify what it means to be a child of school-going age.Footnote2 However, in 2016, the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (Ministry) published a document that outlined the levels of education in Zimbabwe.Footnote3 These levels of education follow the International Standard Classification of Education published by UNESCO in 2011.

According to the Ministry, the education system of Zimbabwe starts with 4 years of infant education which are comprised of two years of Early Childhood Development for children aged 4 and 5 years, and two years of formal primary education (grade 1 and grade 2) for children aged 6 and 7 years. This is followed by 5 years of junior education (grade 3 to grade 7). At the end of grade 7 (typically at 12 years), students take a national exam which marks the completion of primary school. Secondary education in Zimbabwe typically starts at age 13. After four years of secondary school children write Ordinary level (O level) exams at 16 years. Up to this point, the Ministry classifies this as the level of ‘basic education’. At age 18, some children will proceed to write Advanced level (A level), which is comprised of two years of post-secondary education. As in the British system, A level results mostly determine whether an individual will be able to enter university.

Data

This study uses a nationally representative sample from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Since 1984, the DHS Program has been collecting information on demographic characteristics of households, women, men, and children in over 90 developing countries. In 2001, the DHS started conducting population-based HIV testing for women and men aged 15–49 years. However, the 2015 wave of the Zimbabwe DHS (ZDHS) is unique in that it contains HIV test results for children 0–5 years, minors aged 6–14 years, women aged 15–49 years, and men aged 15–54 years. The survey was conducted by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) from July to December 2015 (ZDHS Citation2015).

In order to obtain a representative sample of all ten provinces in Zimbabwe, ZDHS used an existing sampling frame applied in the 2012 population census conducted by ZIMSTAT. During the survey, provinces were divided into districts and these districts were further split into smaller administrative units called wards. Each ward was subdivided into enumeration areas (EA's), which were used as primary sampling units by the ZDHS. The sample for the 2015 ZDHS was selected using a stratified two-stage cluster sampling procedure. In the first stage, there were 400 (166 urban and 234) EA's included in the 2015 ZDHS. In the second stage, maps were drawn for each cluster and every household was listed. A representative sample of 11,196 households was randomly selected across the EA's for interviews and of these, 10,534 households were successfully interviewed, which translates to a 94% response rate (ZDHS Citation2015).

This study uses four ZDHS datasets, i.e. Household Listing, Individual Women's, Men's, and HIV Test datasets. The Household Listing dataset contained 43,706 observations and was used to identify 11,673 children who had their blood specimens for HIV tests taken. The HIV Test dataset with 32,192 observations was used to obtain HIV test results for these individuals (children, mothers and fathers) included in our study. During the HIV data collection process, an anonymously linked protocol was used to allow for the merging of test results with socio-demographic factors. The Individual Women's and the Men's datasets were used to identify demographic and HIV data for mothers and fathers of the 11,673 children in the household dataset. Both the Men's and Women's surveys contained information of school-going children aged 15–18 years. However, the women were asked to provide health and demographic information about all children they gave birth to. Men were not asked about their children's health and demographic data. Therefore, we were only able to link fathers to their children if they were the head of the household. The four datasets were linked using a unique cluster, household, and individual identifiers.

Empirical analysis

We anchor the analysis by adopting multivariate logit regressions and the calculation of their marginal effects on the full sample of boys and girls, a sample of boys only, a sample of girls only, a sample of HIV-negative children, and a sample of HIV-positive children. The dependent variable is school non-attendance. The survey question is as follows: ‘Did you attend school at any time during the [previous] school year?’ This variable takes the value of 1 if a child did not attend school in the previous school year and is zero otherwise. The independent variables include gender, HIV-status, age, parental, household, and wealth-level characteristics. These variables help us examine the aforementioned mechanisms that influence school attendance. To make a comparison with HIV, we also included anemia as a control variable for children aged 15 years and above. Anemia is a disease that develops when the blood is deficient of hemoglobin. This disease may cause fatigue, headaches, and shortness of breath. Therefore, anemic children's school attendance may be affected (Ayoya et al. Citation2012). Children are classified as anemic if they have a hemoglobin level adjusted by altitude of less than 11.0 g/dl (ZDHS Citation2015). The Women's and Men's data contain biomedical data of anemic levels of individuals aged 15 years and above who consented to testing. We also include dummy variables for employment status and marriage for analyses that only include children aged 15 years and above. There is no employment or marriage data for children under 15 years because these variables are only available in the Men and Women's surveys. We also disaggregate the analyses by age. That is, we provide regression results for all children aged 6–18, primary school-aged children 6–12, secondary school children aged 13–18, and older children aged 15–18 years. The results from the regression analyses will set the basis for the decomposition analysis to examine intergender and intragender gaps in school attendance.

To analyze gender gaps in school non-attendance, we use the multivariate decomposition method by Blinder (Citation1973) and Oaxaca (Citation1973). This analysis allows for the decomposition of the outcome variable into two groups in a counterfactual manner. These two groups are differences in characteristics (endowments) and differences in the effects of these characteristics (coefficients). Fairlie (Citation2005) and Powers, Yoshioka, and Yun (Citation2011) extended this method to non-linear models. We use the extension by Powers, Yoshioka, and Yun (Citation2011) because it overcomes issues associated with identification and path dependence. We first decompose school attendance by gender to examine intergender differences in educational attainment. Second, to examine effects of HIV on intra-gender differences in educational attainment, we separately decompose non-attendance for the group of boys and the group of girls by HIV status. The goal is to examine whether there is an unexplained gap in non-attendance between boys and girls, HIV-negative boys and HIV-positive boys, HIV-negative girls and HIV-positive girls, HIV-negative boys and girls, and HIV-positive boys and girls. The decomposition is as follows:

where

is the difference in mean school attendance,

are the characteristics, and

are estimated coefficients. The first part of the equation,

represents differences due to endowments, the second part,

represents difference due to coefficients, and the third part,

is the difference in interaction between endowments and coefficients.

Results

provides summary statistics of child, parents, household, and wealth for 11,673 children aged 6–18 years in Zimbabwe. These children were all tested for HIV. Children with an undetermined HIV test result were omitted from the sample. Only 12 children had undetermined HIV tests. The summary statistics are split by gender and HIV-status. The number of boys and girls in the sample is almost equal (5908 boys and 5705 girls). About 3% (298) of the sampled children were HIV-positive. This is proportional to the population of HIV-positive children in Zimbabwe (UNICEF 2019). Of these, 48% (about 144) were boys and 52% (about 154) were girls. The education variable that is used in this study, is school non-attendance. This is the only educational variable available for children aged 6–18 in the survey and represented by a dummy variable that is coded 1 if a child did not attend school in the previous school year and is zero otherwise. About 13% (1507) of the children in the complete sample did not attend school in the previous school year. Boys and girls aged 6–18 years had similar non-attendance rates (12.7% and 13.1%, respectively). The attendance of HIV-positive boys is similar to that of the full sample. About 12.5% of HIV-positive boys did not attend school in the previous school year. However, the number of HIV-positive girls who did not attend school was more than double that of their HIV-negative counterparts. About 27% of HIV-positive girls did not attend school in the previous school year. This calls for further examination of this gap. The group of HIV-positive boys and girls had a higher percentage of children living in female-headed households (about 55% and 58%, respectively) compared to that of the main group of boys and girls (about 44% and 43%, respectively).

Table 1. Main Summary statistics of children aged 6–18 in Zimbabwe.

We estimate the association between school non-attendance and child, parental, household, and wealth characteristics with logit regressions. shows logit regression and average marginal effects results for all children aged 6–18 years.Footnote4 The dependent variable is a binary variable ‘non-attendance’ that takes the value of 1 if a child did not attend school in the previous school year. There are four specifications in this table. The first column shows the effects of HIV and gender on school attendance without the interaction term (i.e. without the HIV-gender interaction) and without covariates. The second column shows the effects of HIV and gender on school attendance with the interaction term and without covariates. The third column shows the effects of HIV and gender on school attendance without the interaction term and with covariates. Column four shows the effects of HIV and gender on school attendance, including both the interaction term and covariates.

Table 2. Logit estimations and average marginal effects for all children aged 6–18 years.

The results show that the HIV coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level in column 1, but it is not statistically significant after including the interaction term (columns 2 and 4). The results also show that the size of the HIV-gender interaction term decreases when child, parental, wealth and regional (or provincial) characteristics are added. This indicates that, in general, the status of being HIV-positive is not statistically significantly associated with school attendance and is likely to be correlated with other variables such as wealth.

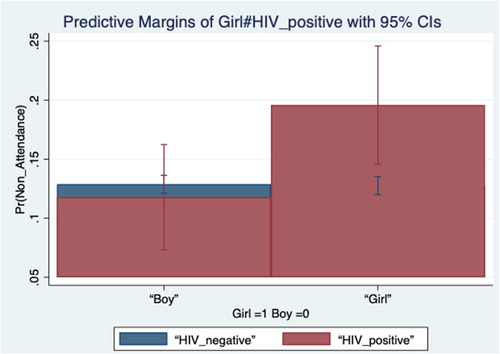

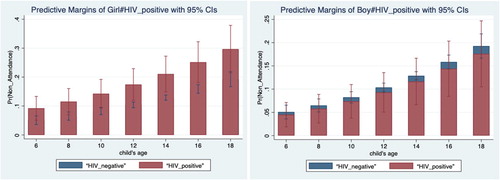

The coefficient of the interaction variable is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level in the full model (column 4). However, the effect of the interaction term cannot be determined from the z-statistic obtained from the results (Norton, Wang, and Ai Citation2004). In order to examine the marginal effect of a change in the interacted variables, we use below, which shows the predicted probabilities Pr (Non-attendance =1) by gender and HIV status. The figure shows that the predicted probabilities are larger for HIV-positive girls, indicating that they are less likely to attend school. On the other hand, the predicted probabilities are larger for HIV-negative boys. We also use a graph to visualize the marginal effects of the interaction term. presents the predicted probabilities of non-attendance by gender and HIV status at various ages. The figure shows that HIV-positive girls have a higher predicted probability of non-attendance compared to HIV-negative boys, HIV-positive boys, and HIV-negative girls. In fact, HIV-negative girls and boys have the lowest predicted probability, followed by HIV-positive boys and lastly, HIV-positive girls. The figure also shows that the predicted probability of non-attendance increases by age for all groups.

also shows that the status of being anemic does not affect school attendance in general. As in the case of HIV, we also interacted anemia with gender (the status of being a girl) and we found no indication of a gender gap (results not shown). The results also show that children who are older (statistically significant at the 1% level), whose mother is primary educated or less (statistically significant at the 1% level), whose father is primary educated or less (statistically significant at the 1% level), with an HIV-positive mother (statistically significant at 5%) and those who are not from the richest wealth group (all statistically significant at the 1% level) are more likely to not attend school. However, children with an HIV-positive father (statistically significant at the 5%) level, children who live in female-headed households (statistically significant at 1%), and children from households with older household heads (statistically significant at 1%), are less likely not to attend school. The results also show that children living in Manicaland, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland West, Matabeleland North, and Masvingo province are less likely not to attend school in comparison to children living in the capital city province of Harare. Orphanhood and residing in a rural area do not have an effect on school attendance.

As a robustness check, we estimate a linear probability model (results not shown). We find that the logit regression results are robust to estimation by the linear probability model. We find similar results as in . Gender and HIV are not statistically significant. However, the interaction between gender and HIV is positive. We also estimated regressions for primary school-aged children (6–12 years), secondary school aged children (13–18 years), and older children (15–18 years) for girls and boys (results in Appendix B and C). In Appendix B, we find that the status of being HIV-positive does not affect school attendance for boys. We also find that being anemic, an orphan, or married does not affect school attendance for older boys. However, we find that older boys who are currently employed attend school at a rate that is 26 percentage points lower than their unemployed counterparts. Unlike boys, we find that HIV affects school attendance of older girls. That is, HIV-positive girls aged 15–18 years are 17 percentage points less likely to attend school than their HIV-negative counterparts. The status of being HIV-positive does not affect school attendance among children aged 6–12 years (See Appendix C). We find that being HIV-positive does not affect school attendance for boys aged 6–12 years and boys aged 13–18 years (see Appendix C). In addition, girls who are married are 58.7 percentage points less likely to attend school than unmarried girls. The status of being anemic, orphaned or employed does not affect attendance for older girls. Appendix D shows the results for HIV-positive children only. The last column of the table shows the marginal effects. The results show that HIV-positive girls are 6.4 percentage points less likely to attend school than HIV-negative boys.

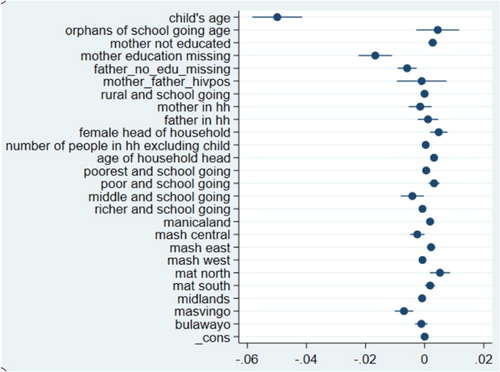

The major advantage of using the decomposition method is that we are able to examine factors that contribute to gaps in schooling attendance by HIV-status and by gender. We are also able to examine the explained and unexplained differential in school attendance between boys and girls. The explained differential shows the gender gap to be related to the observed (child, parental, household, wealth, and regional) characteristics. The unexplained differential in school attendance will highlight the gender gap in school attendance that exists due to the effects of these characteristics. This unexplained gender gap shows that a portion of the gender gap in school attendance is due to factors not observed in the data. The factors may only be unique to the group of HIV-positive girls. A summary of the decomposition results is shown in . The table shows the effects of differences in endowments (explained), differences in coefficients (unexplained), and partly explained by the interaction of the differences. This analysis uses the same child, parental, household, wealth, and regional characteristics as in the logit regressions. The first column of shows that there is a statistically significant non-attendance gap between HIV-positive boys and girls (statistically significant at the 1% level). About 56% of the gap is attributed to the differences in coefficients, while 44% is attributed to differences in characteristics. Results for girls by HIV status are shown in column 2. The differences in the effects of the characteristics and effects of the characteristics are negative and statistically significant at the 1% level and 5% level, respectively. This implies that HIV-negative girls are endowed with characteristics that allow them to attend more school and that the effects of these endowments are larger than HIV-negative girls. Similar to the case of HIV-positive children, about 44% of the non-attendance gap between HIV-negative and HIV-positive girls is attributed to differences in observable characteristics between HIV-negative and HIV-positive girls. About 56% of this gap (statistically significant at the 1%level) is attributed to differences in the effects of these characteristics (coefficients), with differences in age accounting for most of these gaps. shows the coefficient plot for the decomposition of the cohort of girls. The figure shows that variables ‘age of child’ explains most of these gaps. This is consistent with and that visually show that older HIV-positive girls attend less school compared to their HIV-negative counterparts.

Table 3. Multivariate decomposition results for all children, boys, and girls aged 6–18 in Zimbabwe.

Discussion

We have estimated the effects of HIV on school non-attendance in Zimbabwe because HIV-infected children are expected to be less likely to attend school due to illness (Anabwani, Karugaba, and Gabaitiri Citation2016; Pufall et al. Citation2014; Parchure et al. Citation2016), their parents not being able to facilitate their schooling (Akbulut-Yuksel and Turan Citation2013), stigma or discrimination (Henning et al. Citation2018; Anabwani, Karugaba, and Gabaitiri Citation2016; Campbell et al. Citation2014), and financial issues (Hong Citation2011 and Poulsen Citation2006). This is the first study to examine inter-gender and intra-gender gaps in school attendance. That is, we analyze school attendance gaps between HIV-positive boys and HIV-positive girls; HIV-positive and HIV-negative boys; as well as HIV-positive and HIV-negative girls. The results show no direct effects of being HIV-positive on school attendance. We also do not find parental HIV to have a direct effect on the school attendance of children. However, we find that (older) HIV-positive girls attend less school than HIV-negative girls. After decomposing school attendance gender gaps (), we find a statistically significant school attendance gap between HIV-positive girls and HIV-positive boys. We also find a school attendance gap between HIV-positive girls and HIV-negative girls. Results for the full sample () are in concurrence with Pufall et al. (Citation2014), who found that HIV infection alone did not affect children's educational outcomes in (Eastern) Zimbabwe. In addition, as mentioned earlier, previous studies have mainly focused on examining how orphanhood affects children's education (Guo, Li, and Sherr Citation2012). Results from these studies have shown that the effects of (HIV) orphanhood on schooling are mixed. In our study, we do not find effects of orphanhood on school attendance. This result is similar to that of studies such as Harrison et al. (Citation2017).

It is not surprising that we do not find schooling gaps between boys and girls in general. This is because there is gender parity in school enrollment in Zimbabwe (Mawere Citation2013; UNICEF 2011). However, the fact that we do not observe the same result for HIV-positive boys and girls is quite puzzling. This is compounded by the fact that there is a dearth of literature that solely investigates HIV-related issues between school-aged boys and girls. Although it is not clear why we only find schooling gaps among girls. We conjecture that school non-attendance among girls can be explained by a few factors discussed below.

Diseases may more often go untreated among girls than among boys and may worsen girls’ health status. Given that the age of the child constitutes a larger share of the unexplained gaps in our study, older girls maybe experiencing disease-related symptoms more than boys. HIV-related outcomes for children are affected by caregivers’ willingness to invest in children's access to care, which translates to better (schooling) outcomes for children (Ferrand et al. Citation2017). While there are currently no studies that have examined gender-differences in healthcare access among HIV-infected children in Zimbabwe, Ferrand et al. (Citation2017)'s study highlights that caregivers’ investment in children's health does affect children's schooling outcomes. The schooling gaps we observe could indicate that HIV-positive girls attend less school due to lower investment in their health, thereby affecting their school attendance. About 89% of HIV-infected children in Zimbabwe have access to Antiretroviral drugs (ARV's) (UNAIDS 2018). It is therefore important to focus on ensuring that the remaining 11% have access to ARV's as well as it may affect HIV-infected children's mortality/morbidity and may lead to a further loss of human capital.

HIV-positive girls may experience internalized stigma (Simbayi et al. Citation2007), bullying (Campbell et al. Citation2014), and/or mental health issues (Vreeman et al. Citation2015). For example, Kitara et al. (Citation2013) found that HIV orphaned girls in Uganda had the most negative attitude towards education and were less assertive compared to non-orphaned girls. These differences in mental health or internalized stigma have not been extensively studied between HIV-positive/orphaned boys and girls. Results on gender-differences in mental health or internalized stigma are mixed and vary by country. Therefore, there is no evidence as to whether HIV-positive girls in Zimbabwe experience more stigma and/or mental health issues compared to boys. This is a topic that needs to be further investigated.

HIV-positive girls may experience gender-related stigma. HIV-positive girls may be missing school due to being female and HIV-positive. The intensity of HIV-related stigma may be compounded by gender (Sangaramoorthy, Jamison, and Dyer Citation2017; Logie et al. Citation2011). Intersectional effects brought about by the status of being HIV-positive and being female may contribute to the reasons why HIV more strongly affects girls’ school attendance. New studies that examine gender-related stigma are needed in order to draw more definite conclusions as to why HIV-positive girls attend less school in Zimbabwe (Mbonu, van den Borne, and De Vries Citation2009). In addition, older girls may engage in age-desperate sexual relationships, which may increase the risk of contracting HIV and pregnancy, which may interfere with their schooling.

We also find that in general, poor children, employed boys and married girls are less likely to attend school. Due to poverty, some adolescent boys may start working and adolescent girls may get married. This is not surprising given that these issues have been found to affect school attendance in SSA (Walker Citation2012; Moyi Citation2011). Given the relationship between HIV and poverty (Lopman et al. Citation2007), studies in Zimbabwe have shown that HIV-positive adolescent girls are frequently either married to or in a relationship with men who are at least 3–5 years older (Schaefer et al. Citation2017). In addition, household power dynamics may have an influence on children's school attendance. We found varying results about the gender-roles of parents/guardians. Specifically, our results show that boys and girls who live in female-headed households are likely to have less non-attendance. Similarly, Nyamukapa and Gregson (Citation2005) found that Zimbabwean orphans who reside in female-headed households, particularly girls, were more likely to complete school.

We also found that boys, who live in the same household as their mothers, are less likely to attend school. This result was not found for girls and it is not clear why this is the case. One potential explanation could stem from the fact that a mother's presence in the household does not necessarily mean that the mother is the decision-maker in the children's schooling. These results may signify that power dynamics in the household may have an influence on children's educational attainment (Lloyd and Blanc Citation1996). That is, a mother's presence in the household does not necessarily mean that the mother can enable education for her child, especially when the child is male. This is a topic that will need further investigation as well. We were only able to link a small fraction of HIV-tested fathers who were head of household and reside in the same household as the children. However, we find that HIV-negative children with HIV-fathers are less likely to not attend school. This is in contrast to Akbulut-Yuksel and Turan (Citation2013), who found that children of HIV-positive fathers experienced 0.13 fewer years increase in schooling compared to children with HIV-negative fathers. Our results could reflect that HIV-infection of a parent may not have a statistically significant impact on school attendance, as shown by the results of the other groups of children.

This study has some limitations. We are only able to analyze school attendance in the previous school year as it is the only educational variable available for school-going children. Therefore, we cannot fully determine whether a child dropped out of school permanently. In addition, we cannot extensively contrast our paper with that of Pufall et al. (Citation2014) and other papers that examine orphans’ schooling attainment. We are limited to only one wave of data, since this is the first DHS dataset that contains information on HIV-infection among children. Therefore, we are limited to analyses that only allow us to examine the association between HIV status (an endogenous variable) and educational outcomes. Hence, we cannot draw causal inferences. Lastly, we were only able to link HIV-tested fathers to their children if they were the head of the household and resided in the household. This resulted in fewer observations for this variable.

Conclusion

We find a gap in school attendance between HIV-positive girls and HIV-negative boys, and between HIV-positive girls and HIV-negative girls. In both cases, the major contributor to this gap is age (i.e. being an older HIV-positive girl). Specifically, while the marginal effect results initially show that HIV-positive girls are less likely to attend school, the results from the decomposition analysis show that this result is influenced by older girls. These results can be explained by the fact that adolescent girls are at a higher risk of contracting HIV in Zimbabwe. Recent studies have highlighted that age influences the intergender and intragender gaps in school attendance. This result may be due to some adolescent girls in Zimbabwe entering early marriages or relationships with older men as a way of escaping poverty. These girls may already be HIV-positive or may acquire HIV from their older husbands or romantic partners (Mavhu et al. Citation2018). However, is not clear whether marriage/partnership with an older man alone, HIV-infection alone, or both lead to non-attendance (or possibly dropout) among girls. Future research should further examine this in order to determine what actually causes this gap. Due to the age-difference with older partners and the power dynamics between men and women, some girls feel that they are unable to negotiate for condom use (Mavhu et al. Citation2018). It is therefore important to continue to implement programs that educate men (and women) about the importance of condom use. It is also important to continue to address issues related to violence against women as it contributes to the issues related to power dynamics in relationships in Zimbabwe (Mavhu et al. Citation2018). Until this study, there had not been studies that have examined how HIV contributes to inter-gender and intra-gender gaps in schooling in Zimbabwe. More studies are needed to further examine whether HIV-positive girls acquired HIV from their romantic partners and whether they are aware of their health status. This will help clarify whether HIV, early marriage, or any other reason leads to non-attendance or dropout. Future studies should also qualitatively examine whether older HIV-positive adolescent girls (who are not in school) are willing to attend school and provide solutions to this issue in order to inform HIV and education policies that target adolescent girls.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The ‘hotspots’ in McCoy's study are Zimbabwe's capital Harare, Mashonaland West, and Mashonaland Central. The regions with highest HIV rates are Matebeleland North and Matebeleland South (Zimbabwe Demographic and Heath Surveys Citation2015).

2 The Education Act (25:04) of Zimbabwe defines a school going child as ‘a child of an age within such limits as may be prescribed’.

3 This was noted in the Ministry's strategic plan for 2016–2020.

4 The results for the marginal effects are in square brackets.

References

- UNAIDS. Zimbabwe. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zimbabwe.

- UNESCO. Education Act of Zimbabwe. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://www.unesco.org/education/edurights/media/docs/d0945389cdf8992e8cb5f3a4b05ef3b3aa0e6512.pdf.

- UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf.

- UNICEF. Gender Review of Education in Zimbabwe. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://www.ungei.org/paris2011/docs/2010%20ZIM%20summary%20report.pdf.

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care Zimbabwe National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://www.saywhat.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Zimbabwe-National-HIV-and-AIDS-Strategic-Plan-III-1.pdf.

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education of Zimbabwe “A discussion paper on the review of the Education Act [Chapter 25:04].” Accessed April 15, 2019. http://www.justice.gov.zw/imt/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/EDUCATION-ACT-REVIEW-IMT-DISCUSSION-PAPER-MINISTRY-OF-PRIMARY-AND-SECONDARY-EDUCATION.pdf.

- Zimbabwe- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Accessed April 15, 2019. http://uis.unesco.org/country/ZW.

- Akbulut-Yuksel, M., and B. Turan. 2013. “Left Behind: Intergenerational Transmission of Human Capital in the Midst of HIV/Aids.” Journal of Population Economics 26: 1523–1547.

- Anabwani, G., G. Karugaba, and L. Gabaitiri. 2016. “Health, Schooling, Needs, Perspectives and Aspirations of HIV Infected and Affected Children in Botswana: A Cross-Sectional Survey.” Bmc Pediatrics 16 (1): 132.

- Ayoya, M. A., G. M. Spiekermann-Brouwer, A. K. Traoré, and C. Garza. 2012. “Effect on School Attendance and Performance of Iron and Multiple Micronutrients as Adjunct to Drug Treatment of Schistosoma-Infected Anemic Schoolchildren.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin 33 (4): 235–241.

- Bandason, T., L. F. Langhaug, M. Makamba, S. Laver, K. Hatzold, S. Mahere, S. Munyati, S. Mungofa, E. L. Corbett, and R. A. Ferrand. 2013. “Burden of HIV among Primary School Children and Feasibility of Primary School-Linked HIV Testing in Harare, Zimbabwe: A Mixed Methods Study.” AIDS Care 25: 1520–1526.

- Bhargava, A. 2005. “Aids Epidemic and the Psychological Well-Being and School Participation of Ethiopian Orphans.” Psychology, Health & Medicine 10: 263–275.

- Blinder, A. S. 1973. “Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates.” The Journal of Human Resources 8: 436–455.

- Campbell, C., L. Andersen, A. Mutsikiwa, C. Madanhire, M. Skovdal, C. Nyamukapa, and S. Gregson. 2014. “Children's Representations of School Support for HIV-Affected Peers in Rural Zimbabwe.” BMC Public Health 14 (1): 1–13.

- Chikovore, J., L. Nystrom, G. Lindmark, and B. M. Ahlberg. 2009. “HIV/AIDS and Sexuality: Concerns of Youths in Rural Zimbabwe.” African Journal of AIDS Research 8 (4): 503–513.

- Delva, W., A. Vercoutere, C. Loua, J. Lamah, S. Vansteelandt, P. De Koker, P. Claeys, M. Temmerman, and L. Annemans. 2009. “Psychological Well-Being and Socio-Economic Hardship among Aids Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children in Guinea.” Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV 21: 1490–1498.

- Fairlie, R. W. 2005. “An Extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca Decomposition Technique to Logit and Probit Models.” Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 30: 305–316.

- Ferrand, R. A., V. Simms, E. Dauya, T. Bandason, G. Mchugh, H. Mujuru, P. Chonzi, J. Busza, K. Kranzer, and S. Munyati. 2017. “The Effect of Community-Based Support for Caregivers on the Risk of Virological Failure in Children and Adolescents with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe (Zenith): An Open-Label, Randomised Controlled Trial.” The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 1: 175–183.

- Floyd, S., A. C. Crampin, J. R. Glynn, N. Madise, M. Mwenebabu, S. Mnkhondia, B. Ngwira, B. Zaba, and P. E. Fine. 2007. “The Social and Economic Impact of Parental HIV on Children in Northern Malawi: Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study.” AIDS Care 19: 781–790.

- Guo, Y., X. M. Li, and L. Sherr. 2012. “The Impact of HIV/Aids on Children's Educational Outcome: A Critical Review of Global Literature.” Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV 24: 993–1012.

- Harrison, S. E., X. Li, J. Zhang, P. Chi, J. Zhao, and G. Zhao. 2017. “Improving School Outcomes for Children Affected by Parental HIV/Aids: Evaluation of the Childcare Intervention at 6-, 12-, and 18-Months.” School Psychology International 38: 264–286.

- Henning, M., C. M. Kirk, E. Franchett, R. Wilder, V. Sezibera, C. Ukundineza, and T. Betancourt. 2018. “Over-Age and Underserved: A Case Control Study of HIV-Affected Children and Education in Rwanda.” Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 13: 81–93.

- Hong, Y. 2011. “Care Arrangements of Aids Orphans and Their Relationship with Children's Psychosocial Well-Being in Rural China.” Health Policy and Planning 26: 115–123.

- Kidman, R., J. A. Hanley, G. Foster, S. Subramanian, and S. J. Heymann. 2012. “Educational Disparities in Aids-Affected Communities: Does Orphanhood Confer Unique Vulnerability?” Journal of Development Studies 48: 531–548.

- Kitara, D. L., H. C. Amongin, J. C. Oonyu, and P. K. Baguma. 2013. “Assertiveness and Attitudes of HIV/Aids Orphaned Girls towards Education in Kampala (Uganda).” African Journal of Infectious Diseases 7: 36–43.

- Lloyd, C. B., and A. K. Blanc. 1996. “Children's Schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Fathers, Mothers, and Others.” Population and Development Review 22: 265–298.

- Logie, C. H., L. James, W. Tharao, and M. R. Loutfy. 2011. “HIV, Gender, Race, Sexual Orientation, and Sex Work: A Qualitative Study of Intersectional Stigma Experienced by HIV-Positive Women in Ontario, Canada.” PLoS Medicine 8: e1001124.

- Lopman, B., J. Lewis, C. Nyamukapa, P. Mushati, S. Chandiwana, and S. Gregson. 2007. “HIV Incidence and Poverty in Manicaland, Zimbabwe: Is HIV Becoming a Disease of the Poor?” AIDS 21 (Suppl. 7): S57–S66.

- Matshe, I., and O. Pimhidzai. 2008. “Macroeconomic Impact of HIV and Aids on the Zimbabwean Economy: A Human Capital Approach.” Botswana Journal of Economics 5: 32–45.

- Mavhu, W., E. Rowley, I. Thior, N. Kruse-Levy, O. Mugurungi, G. Ncube, and S. Leclerc-Madlala. 2018. “Sexual Behavior Experiences and Characteristics of Male-Female Partnerships Among HIV Positive Adolescent Girls and Young Women: Qualitative Findings from Zimbabwe.” PloS one 13 (3): e0194732.

- Mawere, D. 2013. “Evaluation of the Nziramasanga Report of Inquiry into Education in Zimbabwe, 1999: The Case of Gender Equity in Education.” International Journal of Asian Social Science 3 (5): 1077–1088.

- Mbonu, N. C., B. van den Borne, and N. K. De Vries. 2009. “Stigma of People with HIV/Aids in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Literature Review.” Journal of Tropical Medicine 2009: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2009/145891.

- McCoy, S. I., R. Buzdugan, N. S. Padian, R. Musarandega, B. Engelsmann, T. E. Martz, A. Mushavi, A. Mahomva, and F. M. Cowan. 2015. “Implementation and Operational Research: Uptake of Services and Behaviors in the Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission Cascade in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69 (2): e74–e81. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000597.

- Moyi, P. 2011. “Child Labor and School Attendance in Kenya.” Educational Research and Reviews 6 (1): 26–35.

- Mpofu, J., and S. Chimhenga. 2016. “Performance in Schools by Students from Child Headed Families in Zimbabwe: Successes Problems and Way Forward.” IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) 6 (3): 37–41.

- Norton, E. C., H. Wang, and C. Ai. 2004. “Computing Interaction Effects and Standard Errors in Logit and Probit Models.” The Stata Journal 4 (2): 154–167.

- Nyamukapa, C., and S. Gregson. 2005. “Extended Family's and Women's Roles in Safeguarding Orphans’ Education in Aids-Afflicted Rural Zimbabwe.” Social Science & Medicine 60: 2155–2167.

- Oaxaca, R. 1973. “Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets.” International Economic Review 14: 693–709.

- Orkin, M., M. E. Boyes, L. D. Cluver, and Y. Zhang. 2014. “Pathways to Poor Educational Outcomes for HIV/Aids-Affected Youth in South Africa.” Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV 26: 343–350.

- Parchure, R., V. Jori, S. Kulkarni, and V. Kulkarni. 2016. “Educational Outcomes of Family-Based HIV-Infected and Affected Children from Maharashtra, India.” Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 11: 332–338.

- Poulsen, H. 2006. “The Gendered Impact of HIV/Aids on Education in South Africa and Swaziland: Save the Children's Experiences.” Gender & Development 14: 47–56.

- Powers, D. A., H. Yoshioka, and M.-S. Yun. 2011. “Mvdcmp: Multivariate Decomposition for Nonlinear Response Models.” The Stata Journal 11: 556–576.

- Pufall, E. L., C. Nyamukapa, J. W. Eaton, C. Campbell, M. Skovdal, S. Munyati, L. Robertson, and S. Gregson. 2014. “The Impact of HIV on Children's Education in Eastern Zimbabwe.” Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/HIV 26: 1136–1143.

- Sangaramoorthy, T., A. Jamison, and T. Dyer. 2017. “Intersectional Stigma among Midlife and Older Black Women Living with HIV.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 19: 1329–1343.

- Schaefer, R., S. Gregson, J. W. Eaton, O. Mugurungi, R. Rhead, A. Takaruza, R. Maswera, and C. Nyamukapa. 2017. “Age-Disparate Relationships and HIV Incidence in Adolescent Girls and Young Women: Evidence from Zimbabwe.” Aids (london, England) 31 (10): 1461–1470.

- Simbayi, L. C., S. Kalichman, A. Strebel, A. Cloete, N. Henda, and A. Mqeketo. 2007. “Internalized Stigma, Discrimination, and Depression among Men and Women Living with HIV/Aids in Cape Town, South Africa.” Social Science & Medicine 64: 1823–1831.

- Vreeman, R. C., M. L. Scanlon, I. Marete, A. Mwangi, T. S. Inui, C. I. McAteer, and W. M. Nyandiko. 2015. “Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adolescents Enrolled in a Disclosure Intervention Trial in Western Kenya.” AIDS Care 27 (Suppl. 1): 6–17.

- Walker, J. A. 2012. “Early Marriage in Africa–Trends, Harmful Effects and Interventions.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 16 (2): 231–240.

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2018. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD?locations=ZW.

- World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://www.who.int/hiv/data/en/.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency [Zimbabwe], and ICF. 2015. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2015 [Dataset]. Rockville, Maryland: The Zimbabwe Nationals Statistics Agency and ICF [Producers]. ICF [Distributor], 2018.

- Zinyemba, T. P., M. Pavlova, and W. Groot. 2020. “Effects of HIV/Aids on Children’s Educational Attainment: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Economic Surveys 34: 35–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12345.