?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

School choice can segregate schools by academic ability, income or ethnicity, but is this because of households’ choices, or constraints in access to good schools? We examine whether segregation is by choice, finding that households’ school choices are segregating in most areas. Through counterfactual simulation, we find that implementing a policy of ‘neighbourhood’ schools would, in contrast, reduce segregation in most areas, under the assumption that each household’s location is fixed. Policymakers require further evidence to weigh up the effects of school choice systems on sorting across schools and neighbourhoods, relative to potential efficiency benefits of school choice.

1. Introduction

School choice – broadly defined as any system in which parents’ preferences over schools partly determine allocation to school – has theoretical benefits: increasing competition between schools drives productivity (Friedman Citation1955; Hoxby Citation2003) and freedom of choice promotes equality of access to ‘good’ schools (Cantillon Citation2017). There is long-standing concern, however, that allowing households school choice will increase school segregation between groups of different social class, income level and ethnicity, that may be problematic for educational outcomes (Guryan Citation2004; Reber Citation2010; Hanushek et al. Citation2009; Lutz Citation2011; Johnson and Rucker Citation2011; Billings, David, and Deming Citation2014) and wider outcomes such as crime (Billings, David, and Deming Citation2014; Citation2019). It is also likely to be problematic for society, as integrated schools ‘offer the opportunity to enhance intergroup relations’ (Burgess and Platt Citation2021) and pro-social behaviour (Rao Citation2019).

This paper focuses on whether school segregation is by choice, rather than due to constraints in school access or residential segregation. This is important, because to design policies to reduce segregation ‘knowledge about its driving forces is indispensable’ (Oosterbeek Citation2021). We use data from parents’ submitted school choices, under-explored due to their recent availability. This improves upon using school allocations, as these are the product of school choices and assignment to school, considering school over-subscription criteria and capacity constraints.

Consider an example of a high-attaining state school that has few low-income pupils, neighbouring a low-attaining state school with the reverse. This segregation could be due to households’ preferences: preferences for a peer-group ‘like us’ (Clark, Dieleman, and de Klerk Citation1992; Schneider and Buckley Citation2002; Karsten et al. Citation2003; Elacqua, Schneider, and Buckley Citation2006; Noreisch Citation2007; Byrne Citation2009; Hastings et al. Citation2009; Bunar Citation2010; Saporito Citation2003; Abdulkadiroğlu, Agarwal, and Pathak Citation2017; Glazerman and Dotter Citation2017), the ‘right mix’ (Byrne Citation2006; Hollingworth and Williams Citation2010; Vowden and James Citation2012) or for distance over academic quality (Weekes-Bernard Citation2007; Hastings et al. Citation2009; Burgess et al. Citation2015; Borghans et al. Citation2015; Glazerman and Dotter Citation2017; Beuermann et al. Citation2018; Harris and Larsen Citation2019; Walker and Weldon Citation2020; Abdulkadiroğlu et al. Citation2020; Bertoni, Gibbons, and Silva Citation2021). Alternatively, this could be driven by constraints in access: all households could prefer the high-attaining school, but if places are rationed by distance to the school and prices rise accordingly (Black and Machin Citation2011; Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger Citation2011), only the higher-income households are able to gain admission through residential sorting. In England, around 15% of households each year are not admitted to their first-choice school because of capacity constraints (Burgess, Greaves, and Vignoles Citation2019), with this percentage higher in urban areas. Using the current allocation of pupils to schools to infer the role of preferences in driving segregation is therefore problematic: segregation could be driven by differences in preferences or differences in constraints across groups.

We provide the first evidence on whether segregation is by choice in a national school choice environment where school choice is not typically constrained by academic ability. Using national administrative data for England, we find that school choices are segregating across most Local Authorities (LAs). A counterfactual exercise that allocates all pupils to their first-choice school, removing all constraints in access, leads to equally highly segregated schools than the current allocation in most areas. This is true for segregation by ethnic group, income deprivation and prior-attainment. In contrast, a counterfactual that assigns pupils to their closest school reduces segregation across all groups in most areas. This final finding would be reversed if only a small percentage of households changed their residential choice in response to such a reform, however.

England is an excellent laboratory to study the functioning of school choice. The right for parents to express a preference for their child’s school has been enshrined since the 1988 Education Reform Act. School choices are collected by a central authority and the allocation mechanism used to assign pupils to schools is truth-revealing. National, complete and high-quality data on each pupil in a state-funded school is collected by Government, including their school choices. We exploit the variation in density, ethnic and social composition of LAs to explore how school choice may or may not contribute to segregation in different areas.

A significant body of qualitative research across fields studies households’ school choices. Choices are often driven by the reproduction of cultural capital (Ball, Bowe, and Gewirtz Citation1995; Reay and Ball Citation1998; Ball Citation2003; Butler and Robson Citation2003; Bridge Citation2006; Byrne Citation2006) as the middle-classes fear the ‘destructive and contaminating effects of going to the local comprehensive’ (Reay and Lucey Citation2004).

This process leads to ‘white flight’ from some schools (Reber Citation2005; Noreisch Citation2007; Baum-Snow and Lutz Citation2011; Vowden and James Citation2012) and consequently segregated ‘idealized’ and ‘demonized’ schools (Reay and Lucey Citation2004) while working-class households are traditionally characterised as ‘disconnected’ choosers (Gewirtz, Ball, and Bowe Citation1994). Research focusing on the interaction between class and ethnicity has also shown preference against ‘white’ schools for some ethnic minority households to avoid the possibility of racism/bullying and enhance community (Reay and Lucey Citation2004; Byrne Citation2009; Weekes-Bernard Citation2007; Bunar Citation2010).

One may suppose, therefore, that observed levels of segregation in England’s schools are through choice, but in fact there are also ‘structural constraints on the choices available to parents in economically deprived areas’ (Weekes-Bernard Citation2007). This is because over-subscribed schools must choose a way to ration places, that is often by proximity. Admission to a school at the top of the local hierarchy, dependent on a ‘fragile equation of colour, ethnicity and social class’ (Reay and Lucey Citation2004) therefore typically depends on parents’ willingness and means to afford higher property prices in the desirable catchment area. This is one of the ‘circuits of schooling’ identified by Ball, Bowe, and Gewirtz (Citation1995). Burgess et al. (Citation2011) and Hamnett and Butler (Citation2011) describe how school catchment areas limit access for economically disadvantaged households, who have only the illusion of choice to over-subscribed schools. Hamnett and Butler (Citation2013) conclude that ‘distance-based rationing of supply of school places in the face of high demand serves to reinforce and reflect existing patterns of residential social segregation and to indirectly undermine the principles underlying the policy of greater school choice’.

Previous empirical research has used either event analysis or counterfactual simulation to study segregation under school choice. In a meta-review of research, Wilson and Bridge (Citation2019) conclude that ‘school choice is associated with higher levels of segregation of pupils between schools’, remarkably consistent across school choice systems and contexts.

In the former strand of research, the consensus is that introducing school choice has not led to markedly higher segregation between social groups in England (Allen and Vignoles Citation2007; Goldstein and Noden Citation2003; Gorard and Fitz Citation2000; Noden Citation2000) or German primary schools (Schneider et al. Citation2012; Makles and Schneider Citation2015).

Elsewhere worldwide, school choice is typically related to increases in segregation across schools. In Chile, by ability (Hsieh and Urquiola Citation2006); New Zealand and the US by race (Ladd and Fiske Citation2001; Bifulco and Ladd Citation2007), Sweden by ability and family background (Söderström and Uusitalo Citation2010; Böhlmark, Holmlund, and Lindahl Citation2016) and South Korea by ability (Oh, Jung, and Sohn Citation2019).

In the latter, counterfactual, strand of research, segregation is typically found to decrease under ‘neighbourhood’ allocation to schools (Allen Citation2007; Taylor Citation2009; Östh, Andersson, and Malmberg Citation2013; Bernelius and Vaattovaara Citation2016; Glazerman and Dotter Citation2017; Boterman Citation2019) although Harris and Johnston (Citation2020) find that school intakes generally reflect the surrounding neighbourhoods. Glazerman and Dotter (Citation2017) find that a neighbourhood schools policy would decrease segregation by race but increase segregation by income.

Our paper builds most closely on Allen (Citation2007), who assesses the allocation of pupils in earlier administrative data for England, relative to counterfactual simulations. Allen (Citation2007) concludes that where pupils sort into non-proximity schools it tends to increase segregation by ability and income. The difference between the current and counterfactual simulations is largest in urban areas, presumably as pupils have a more diverse choice set of schools within a reasonable commuting time. We extend this analysis by using administrative data on households’ school choices in addition to allocation to explore the role of preferences relative to constraints.

Recent work studying Amsterdam is the first to quantitatively isolate the effect of parents’ school choices (preferences) on segregation. Using administrative data from the secondary school match, Oosterbeek (Citation2021) find that 70% of school segregation (within school tracks) is driven by preference heterogeneity across groups. In Amsterdam, pupils are free to choose any school that offers their ability track. As Amsterdam is relatively small and school density is high, the authors suggest that residential segregation should not necessarily be a main driver of school segregation. The results may not therefore generalise to cities without free school choice, larger cities, or cities with less developed public transport.

The next section describes the system of school choice in England in more detail, followed by our data and methodology. The results follow, including robustness checks. The final section provides discussion, including possible policy options to reduce segregation, and our conclusion.

2. School choice in England

School choice is England is broadly defined as ‘open enrollment’ as opposed to ‘opt-out’ (see Wilson and Bridge Citation2019). That is, households are not assigned to a default school that they can opt out from (as is common in the US, Scotland, and some areas in Germany) and instead can submit preferences for any preferred school(s), locally or further afield. This is like the system in many European countries – for example Sweden and the Netherlands – New Zealand, and South America – Chile and Brazil (Wilson and Bridge Citation2019). Butler and Hamnett (Citation2007) characterise the English education system as sitting between ‘a choice-driven North American model of educational allocation and a more geographically driven allocation model traditionally favoured in Europe’.

Parents in or entering the English state education system provide a ranking of their preferred choices of school on a form that is submitted in a centralised system to their LA. All government-funded schools, including faith, selective and academy schools participate in this common system. Applications made to private schools are not coordinated, although parents can apply to both private and state schools simultaneously. The process is the same for primary and secondary schools.

Depending on the LA, parents can provide up to three to six choices of school in rank order, with three being the mode (). Parents may apply to school(s) outside their LA by ranking the school(s) on the application form submitted to their home LA.Footnote1 The number of choices parents can make therefore depends on the restriction of their home LA.

Table 1. Summary statistics on 115 Local Authorities.

A set of published school admissions criteria are used where a school is over-subscribed. Typically, these include: whether the child has a statement of special educational need, whether the child is looked-after by the LA; whether the child has a sibling at the school already; the distance of the family home from a school; and less commonly, the faith or aptitude of a child (Burgess, Greaves, and Vignoles Citation2019). Each child is allocated to their highest ranked school where they are admitted according to the criteria of each school. This allocation is done using an algorithm (student optimal stable allocation, see Pathak and Sönmez Citation2013). If a pupil is not allocated to any preferred school, they are assigned to a school with spare capacity (that is by definition less popular).

The algorithm used is weakly truth-revealing, meaning that parents can do no better than by reporting their true preferred schools, although the short list implies that low probability schools may be omitted (Haeringer and Klijn Citation2009; Calsamiglia, Haeringer, and Klijn Citation2010; Fack, Grenet, and He Citation2019). Theoretically, the first school choice should not be strategic, as parents’ need for a ‘safe school’ (to avoid being unassigned) can be satisfied using the lower ranked choices. Fack, Grenet, and He (Citation2019) show that non-trivial application costs can induce non-truthful application behaviour, however. Unfortunately, we therefore cannot rule out that parents’ ‘skip the impossible’ (as coined by Fack et al. [Citation2019]) for their first school choice. Parents may also have erroneous beliefs that imply that some preferred schools are omitted from the submitted choice list. For this reason, we treat the list of chosen schools as ‘stated’ preferences rather than necessarily parents’ true underlying preferences.

Parents may consider transport provision when making school choices. There are official regulations from the Department for Education regarding school transport, which in general provides free transport if the ‘nearest suitable school’ is sufficiently difficult to access by foot.Footnote2 This could in principle restrict parents’ school choices, although in practice, described later, most parents choose a school that is not their closest.

This system leads to a level of segregation in England’s schools that is around the middle of OECD countries, typically lower than countries where selection by ability is the norm (Jenkins et al. Citation2008).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data

Data on each household’s secondary school choice(s) covers the whole cohort of pupils seeking admission to any English state secondary school in the school-year 2014/2015. Access to these data was provided by the Department for Education, through the National Pupil Database (NPD) application process.

We derive the closest, or neighbourhood, school from pupils’ home location. We calculate the straight-line distance between home and school rather than travel distance, as this is most relevant for school admissions and most computationally feasible. The data include the following pupil-level characteristics that we use to study segregation: eligibility for Free School Meals (FSM) in any of the last six years, a binary variable as a marker of poverty; ethnic group, that we group into White British and non-White British; prior-attainment according to performance in nationally set and externally examined assessments at the end of primary school (KS2). This measure is grouped into the top 20% of prior-attainment and bottom 80%. These are coarse measures, that miss subtlety across the distributions of socio-economic status and prior-attainment, and across ethnic groups. Taylor (Citation2018) shows that there is a meaningful proportion of children ‘who could be described as disadvantaged’ who are not recorded as eligible for FSM, for example. Hobbs and Vignoles (Citation2010) show that FSM children are more likely to be in low-income households than non-FSM children, but between 50% and 75% of FSM children are not in the lowest income households. Additionally, FSM does not capture a broader definition of social class that is shown to influence the process of school choice in other contexts (see for example Boterman [Citation2021]).

Our sample excludes 15 LAs that have a middle school system, where pupils enter secondary school at age 13 rather than age 11. We also exclude 21 LAs where at least 10% of schools are selective – that accept pupils according to performance on an entrance test. We also exclude schools in other LAs that have a selective admissions policy (163 in total). This is to focus our analysis on schools and LAs that operate a non-selective admissions policy, so that our findings are generalisable to non-selective settings.

shows the descriptive statistics for our final sample at the LA-level, for the 115 LAs remaining. The population of students is all students who didn’t choose and weren’t allocated to a Special school (catering for children with special educational needs) or selective school. The median LA has 80% of secondary school pupils that are white, 34% FSM and 39% high prior-attainment. In the median LA, 89% of pupils are assigned to their first-choice school, although there is wide variation across LAs, with the minimum at 66% and maximum at 99%. In the median LA, 45% choose their closest school as first-choice, and 45% attend their closest school. Again, there is variation across LAs, from 19% to 81%.

These data are supplemented with area-level characteristics, such as pupil composition, school density (schools per km2), spare capacity (the ratio of total school places to total applications), rural/urban category, and whether the LA allocates pupils according to ‘fair-banding’ where an equal proportion of pupils from across ability bands is admitted to the school. This policy variable is binary, defined according to whether at least 20% of schools in the LA operate fair-banding, and was collected as part of a wider project on secondary schools’ admissions criteria led by Simon Burgess at the University of Bristol.

3.2. Measuring segregation

A common measure of segregation is the Index of Dissimilarity (D) (Duncan and Duncan [Citation1955]). For two disjoint sub-groups of the population indexed by t ∈ {0,1} representing, for example, white and minority pupils, and G non-overlapping geographical units (for example neighbourhoods or schools), the index is defined as.

where ng,t is the number of group t in unit g, and Nt is the total population of group t across all units. At the LA level, N0 would be the total population of White pupils in the LA, for example.

If D takes its maximum value of 1, this implies that no two members of different sub-groups share the same geographical unit or school. At its minimum value of 0, D implies that the empirical distribution of each sub-group is identical to that of the other. The index has an intuitive interpretation as the proportion of either of the groups who would have to move between geographical units (for example schools) to equalise the spatial distributions of the two groups.

Although popular in the segregation literature, D is known to be upward-biased for finite samples. This problem is especially acute when numbers of one or both groups are small in some geographical units. To address this, we use the bias correction method in Allen et al. (Citation2015), described in Appendix A.

3.3. Counterfactual simulation

Segregation under first-choices is calculated using each household’s first-choice rather than actual school in the measure of D. School capacities are allowed to vary, with popular schools expanding and unpopular schools contracting. By removing capacity constraints, this simulation isolates the effect that parents’ school choices (interpreted as preferences) have on school segregation. We discuss caveats to this interpretation in section 4.5.

An advantage of D as a measure of segregation is that it is additive, that means that the observed D and D resulting from the counterfactual estimates can be differenced. For example, post-residential sorting would be . To assess the degree to which D reflects post-residential rather than underlying residential segregation, we compute segregation under an additional simulated scenario in which all children attend their nearest school. In this scenario, all segregation is residential, so the difference between the actual measured levels of segregation, and the levels measured under this counterfactual indicates the extent of post-residential segregation.

This method is very similar to that described by Allen (Citation2007). The main difference is that way that school capacities are treated in the counterfactual. To treat school capacities as exogenously fixed, Allen uses a ‘Boston’ matching mechanism where some pupils are therefore allocated to schools far away. In contrast, we remove fixed capacities, so each pupil is allocated to his/her nearest school: the de facto catchment area of each school is its Voronoi neighbourhood.

4. Results

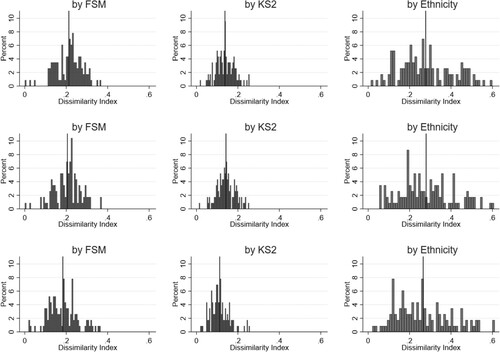

presents the distribution of segregation of secondary schools across LAs in our sample. The first column shows segregation by FSM. The second column shows segregation by prior-attainment and the third by ethnic group. Each row represents a different school choice environment. From top to bottom: current allocation, allocation by first-choice, and allocation by nearest school.

Figure 1. Distribution of segregation indices for 115 LAs in England. Source: Author’s calculations from national preference data and the National Pupil Database. Note: The first column shows segregation index (D) by Free School Meals status; the second column by Key Stage 2 prior-attainment (top 20% vs bottom 80%); and the third column by White/non-White. The first row shows the observed allocation. The second row shows the counterfactual allocation to first choice school. The third row shows the counterfactual allocation of students to their nearest school. The vertical line shows the mean of segregation in each panel.

4.1. Segregation under current allocation

The current distribution of segregation in England’s secondary schools is shown in the first row of . The average level of segregation by FSM is around 0.21: 21% of pupils would have to be re-allocated across schools for there to be an even spatial distribution across schools within the LA. This is slightly lower than found for the cohort of pupils entering secondary school in 2000 (Allen Citation2007). There is variation in segregation across LAs, with some having levels of segregation around zero and some close to 0.4. The inter-quartile range is narrow, however (0.10, ). The average segregation by prior ability is lower, with a mean of 0.14. Recall that this sample excludes selective schools and LAs with at least 10% of selective schools. (Segregation by prior ability would therefore be higher if these schools were included.) The interquartile range is also narrower than for FSM (0.06). In contrast, the average segregation by ethnic group is higher (0.28) and has a wider distribution (inter-quartile range 0.19). Some LAs have levels of segregation close to zero while others are around 0.6, meaning that over half of pupils would have to re-allocated across schools for there to be no segregation within the LA.

Table 2. Distribution of dissimilarity indices of 115 Local Authorities.

England’s secondary schools are therefore more segregated by ethnic group than income deprivation, and least segregated by prior-attainment (excluding the selective system). A high level of segregation by ethnic background is consistent with earlier research, dis-aggregated by ethnic group (Burgess, Wilson, and Lupton Citation2005). The cause may be the interaction between class and race in white middle-class school choices (Byrne Citation2009) and ‘tipping points’ in the acceptable percentage of ‘other’ students (Noreisch Citation2007; Vowden and James Citation2012) but could also reflect active choices by non-White ethnic groups. For example, Burgess, Greaves, and Vignoles (Citation2019) and Walker and Weldon (Citation2020) show, using the nationally representative data we employ here, that the school choice patterns of non-White households are consistent with active engagement in the school choice process and ‘ambitious’ school choices consistent with valuing school quality. Households from the non-majority ethnic group in England may also seek a safe and respectful place for their child, free of bullying (Weekes-Bernard (Citation2007); Bunar (Citation2010)) and low teacher expectations (Weekes-Bernard (Citation2007)). Harris and Johnston (Citation2020) also explore the interaction between ethnic and socio-economic segregation, finding that, for some groups in some LAs, apparent ethnic segregation has ‘underlying socio-economic causes’.

The current level of segregation across LAs is correlated with several observable LA characteristics (). These vary across groups. The percentage of White students in the LA is negatively correlated with segregation by FSM, but positively with segregation by ethnic group. Segregation by ethnic group is higher where there is a higher proportion of non-White pupils, even conditional on geographical characteristics such as school density and market tightness. Segregation by ethnic group is lower in London than other regions, conditional on these other factors.Footnote3

Table 3. Correlates with dissimilarity indices in 115 Local Authorities.

Other variables have a similar effect across categories. For example, as in Allen (Citation2007) urban LAs have higher segregation relative to rural LAs.

Several area-level characteristics are notably uncorrelated with the current level of segregation, however, such as whether households are permitted to express more than three school choices.

4.2. Segregation under first choice allocation

The distribution of segregation across LAs would change only marginally if all pupils in England were assigned to their first-choice school rather than the actual allocation. The second row of shows the distribution for segregation by ethnic group, FSM and prior-attainment. The distributions for FSM and prior-attainment are very similar to the distributions under the current allocation. For example, the mean level of segregation for FSM is 0.21 under both the current allocation and simulated allocation using first-choice school. For prior-attainment, the mean level of segregation remains at 0.14 (). The inter-quartile ranges are also almost identical. The mean and inter-quartile range for segregation by ethnic group are also largely unchanged, although the shape of the distribution is altered, with weight moving from the very lowest to slightly higher levels of segregation. These patterns are perhaps unsurprising given the high percentage of households that are allocated to their first-choice school. At the mean in our sample, 88% of households are allocated to their first-choice school, so the first-choice counterfactual would be affected by only 12% of households.

The lower panel of shows the distribution of the difference in segregation between current and simulated allocations across LAs. There is no difference in segregation by ethnic group, FSM or prior-attainment for the majority of LAs: the mean, mode and median are close to zero in each case. There are LAs where allocating all pupils to their first-choice would increase or decrease segregation, however, up to around 0.13. The interpretation is that constraints on admission to first choice school in some LAs change the proportion of pupils that would have to change schools to equalise the distribution of pupils by around 13%.

At face value, these results suggest therefore that segregation from school choice is a result of parents’ preferences rather than any constraints in accessing preferred schools. Whether this is true depends on whether parents’ school choices reflect their true preferences, or whether, instead, parents’ stated choices are influenced by other factors such as the probability of admission to each school. We return to this in section 4.5.

4.3. Segregation under proximity allocation

In contrast, the distribution of segregation across LAs changes when all pupils are assigned to their closest school. The mean level of segregation typically decreases: by prior-attainment, 0.11 under neighbourhood assignment compared to 0.14 under the current allocation; by FSM, 0.18 compared to 0.21; by ethnic group, 0.27 compared to 0.28 ().

At the LA-level, moving to neighbourhood schools would reduce school segregation in most LAs. This is most obvious for segregation by prior-attainment and FSM, where the mean difference across LAs is −0.03: moving from a system of school choice to neighbourhood allocation would reduce segregation (the proportion of pupils that would need to move schools to equalise the distribution) by 3% in the mean LA. The magnitude of this effect for FSM is equivalent to moving from the median of the distribution to the 35th percentile. For prior-attainment, moving from the median to the 26th percentile. The distributions are also wide, with segregation increasing in around 24%, 22% and 36% of LAs under the neighbourhood allocation compared to the current allocation, for FSM, prior-attainment, and ethnic group, respectively.

These results imply that, overall, school choice exacerbates rather than reduces school segregation arising from residential segregation. This does not take into account that residential choices are endogenous pupil assignment, however. This has two (related) implications. First, that under the counterfactual neighbourhood assignment, parents’ residential choices may be more segregating. For example, parents’ choice of residential neighbourhood becomes even more important when it entirely determines access to schools. Second, that under the current assignment, parents’ residential choices may be more integrating. The current level of neighbourhood segregation may be endogenous to the current school choice environment, as school choice allows some households to choose school and residence independently. Both possibilities are discussed in section 4.5.

4.4. Where does school choice exacerbate segregation?

This section explores the circumstances where allocation by first-choice exacerbates or reduces segregation, presenting results from a multivariate regression with the difference in segregation under the first-choice allocation and current allocation () as the dependent variable. The interpretation of

is the difference in sorting due to school choices when admission constraints are removed. The current allocation, D[alloc], is included as a covariate, as the current allocation is likely to reflect some structural features of the LA that cannot be captured by other observable characteristics. A negative coefficient means that the covariate lowers

, that is equivalent to decreasing segregation under the first-choice allocation relative to the current allocation. The first three columns of show that the coefficient for D[alloc] is negative for each category, and significant for the first two columns: when households face a more segregated school system, their first school choices tend to be less segregating.

Table 4. Correlates with the difference in dissimilarity indices under alternative counterfactuals in 115 Local Authorities.

Geographical characteristics of the LA are typically not correlated with the dependent variable. Two exceptions are first, in London, allocation by first-choice lowers segregation across ethnic groups relative to the current allocation. Second, allocation by first-choice lowers segregation by prior-ability (relative to the current allocation) when school density is higher.

One policy characteristic of the LA is correlated with the difference between current and counterfactual segregation. Areas with fair-banding have higher segregation by FSM and prior-attainment under the first-choice allocation relative to the current allocation. Fair-banding means that parents have a positive probability of admission to a larger set of schools. This result could therefore suggest that when given more freedom to choose schools, households make choices that lead to higher segregation. This suggestion is tentative, however, as the effect of other factors that would theoretically act in a similar way, like parents having more than 3 choices, are close to zero.

In summary, there are no clear or universal characteristics of LAs that are correlated with school choices that are highly segregating or desegregating. The strongest relationship is between the current level of segregation in the LA, that is correlated with first-choices being desegregating relative to the current allocation. Other than that, policy options have the clearest correlation. Where parents have more freedom in their choices (through fair-banding) their choices appear to result in slightly more segregation for some groups.

In the final three columns of , the dependent variable is , and again, D[alloc] is an important covariate. Unsurprisingly, the nearest-school counterfactual is more desegregating (relative to the current allocation) where schools are currently more segregated.

There are few other policy or geographical characteristics that affect the change in segregation between counterfactuals. The coefficient for fair-banding is negative but not significant. This could reflect lower residential segregation in LAs with fair-banding, or more segregating choices/allocations in these LAs. Segregation by ethnic group decreases in the neighbourhood allocation relative to the current allocation where the LA has a higher percentage of FSM pupils and increases with a higher percentage of pupils with low prior-attainment.

Overall, there is an emerging (but tentative) pattern that LAs that currently allow parents more freedom in their school choices are more segregated under first-choices and less segregated under neighbourhood assignment. This strengthens the case that households’ preferences affect the current level of segregation in England’s schools in addition to schools’ capacity constraints, rather than solely by schools’ capacity constraints.

4.5. Robustness

Throughout, we have assumed that school choices reflect parents’ true preferences for schools. This is justified in part by the truth-revealing allocation mechanism used to assign pupils to schools in England. The restricted list length for school choices means that parents may rationally be strategic in their school choices, omitting schools with zero/low probability of admission (Haeringer and Klijn Citation2009; Calsamiglia, Haeringer, and Klijn Citation2010; Fack, Grenet, and He Citation2019). If so, then school choices do not map perfectly to preferences, but instead incorporate constraints (through the expected probability of admission) to some extent.

To explore this, we first interpret the results that school choices are segregating (and neighbourhood allocation desegregating) where households’ school choices are currently less bound by residential location. These are areas for which a meaningful proportion of schools allocate pupils according to prior ability, equalising the distribution (fair-banding LAs). Across these areas where it is most likely that school choices to equate to preferences, school choices generally lead to more segregation relative to the current allocation.

A limitation of all counterfactual studies to date is that households’ location is fixed, rather than responsive to changes in school assignment mechanisms. Local school quality currently informs households’ residential decisions as admission is often implicitly tied to location, for example through ‘catchment areas’ or distance. A substantial body of literature finds that house prices, indicative of demand, respond to local school quality (Black Citation1999; Leech and Campos Citation2003; Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan Citation2007; Gibbons and Machin Citation2008; Fack and Grenet Citation2010; Gibbons, Machin, and Silva Citation2013; Machin and Salvanes Citation2016). Exploring the variation in this response, He (Citation2017) finds heterogeneous effects across cheaper and more expensive school districts and Cheshire and Sheppard (Citation2004) show the house price premium is responsive to the ‘suitability’ of potential homes for families and local constraints in the supply of housing.

How would households’ choice of neighbourhood change if it were explicitly (rather than implicitly) tied to school choice? Theory suggests that households’ location responds to changes in school admission policies (Nechyba Citation2000; Epple and Romano Citation2003; Bayer, Ferreira, and McMillan Citation2007; Ferreyra and Marta Citation2007; Calsamiglia, Martínez-Mora, and Miralles Citation2015, Citation2020). This has been confirmed through empirical work using changes in school choice environments over time (Thrupp Citation2007; Baum-Snow and Lutz Citation2011; Brunner, Cho and Reback Citation2012; Chakrabarti and Roy Citation2015). The re-introduction of school zones (catchment areas) in New Zealand indicates that residential segregation is likely to increase in response to neighbourhood schooling (Thrupp Citation2007). Baum-Snow and Lutz (Citation2011) find a strong migration response of White households in response to desegregation policies in the US, while Reber (Citation2005) estimates that ‘white flight’ reduced the effects of desegregation plans by about one-third.

We find that neighbourhood allocation decreases income (FSM vs non-FSM) segregation compared to the current allocation by 3% at the mean. This implies that, for the mean LA, more segregating residential choices of 3% of non-FSM households would reverse this finding. This seems modest, given the findings in the literature.

A related limitation is that households may respond to a change in school admissions policies by exit to the private sector (Clotfelter Citation1976; Clotfelter Citation2001; Reardon and Yun Citation2003; Reber Citation2005; Saporito Citation2013; Saporito and Sohoni Citation2007; Söderström and Uusitalo Citation2010; Baum-Snow and Lutz Citation2011; Calsamiglia and Güell Citation2018; Calsamiglia, Fu, and Güell Citation2020) that is one method of admission to a preferred school (Butler and Robson Citation2003; Rangvid and Schindler Citation2007; Maloutas Citation2007; Cordini, Parma, and Ranci Citation2019; Bonal, Zancajo, and Scandurra Citation2019; Nielsen, Skovgaard, and Andersen Citation2019; Boterman Citation2021). Again, for the mean LA, a relatively small exit response by more affluent households would reverse the finding that neighbourhood assignment is desegregating.

Like previous counterfactual analysis, we can therefore conclude that neighbourhood allocation would decrease segregation in schools if households have no endogenous responses. Incorporating households’ changes in residential location and exit to the private sector is likely to mean that neighbourhood allocation is no longer desegregating, as in empirical studies of real-world cases.

Finally, our results are similar in an alternative specification where no density correction is applied to the Dissimilarity Index and where schools outside the LA are not aggregated to a single ‘outside option’ (not shown due to space constraints).

5. Discussion

Segregation in schools between different groups of pupils has been shown to have negative short-term and long-term consequences. This paper extends previous research to explore whether, under a system of school choice, segregation is by choice. This is important, as different policies are required to address segregation depending on the cause: driven by parents’ preferences, or constraints in accessing their preferred school. Using national administrative data for England, we find that school choices are segregating across most Local Authorities. Allocating all pupils to their first-choice school, removing all constraints in access, leads to equally highly segregated schools than the current allocation in most areas. This is true for segregation by ethnic group, income deprivation and prior-attainment.

A potential limitation to these results is the interpretation of the first-choice as reflecting parents’ preferences. Despite the truth-revealing assignment mechanism used in England, the short list length (between three and six across England) may induce strategic school choices if households ‘skip the impossible’ where there is no chance of admission (Fack, Grenet, and He (Citation2019)). Our interrogation of the data suggests that this is not the case: school choices are more segregating in areas where school choices are less constrained by a geographically based probability of admission, suggesting that segregation is, to some extent, by choice.

In our second counterfactual, following Allen (Citation2007), we find that ‘neighbourhood’ schooling – where all pupils are assigned to their closest school – reduces segregation relative to the current allocation in most Local Authorities. At face value, this implies that removing school choice would integrate schools. However, interpretating this finding requires careful consideration of the school and neighbourhood choices made by parents in both counterfactuals.

First, parents’ residential choices might be more integrating under school choice than neighbourhood assignment. For example, Boterman (Citation2021) finds that free school choice in Amsterdam has allowed neighbourhood integration, as parents need no longer move to gain admission to their preferred school. (See also Rangvid and Schindler (Citation2007) and Rangvid (Citation2009) for Copenhagen, and Söderström and Uusitalo (Citation2010) for Stockholm.) In contrast, residential sorting is particularly strong in areas where location largely determines school admission, such as Finland (Bernelius and Vilkama Citation2019) and Paris (Oberti and Savina Citation2019). For example, higher income households that choose to live in more integrated neighbourhoods under free school choice may decide to sort into more segregated neighbourhoods around ‘good’ schools to gain admission in a neighbourhood system.

Given the likely residential responses, a ‘neighbourhood’ policy would therefore be likely to lead to increased sorting across neighbourhoods, which in turn might have detrimental effects, such as lower well-being, education, and employment outcomes. Theoretically, outcomes for the minority or disadvantaged group could be reduced due to neighbourhood/peer effects and increased spatial mismatch between workers and jobs (Boustan Citation2012). The causal effect of residential segregation is difficult to establish empirically (Manski Citation1993; Durlauf Citation2004), although experimental evidence suggests that randomly assigning households to less disadvantaged neighbourhoods leads to wide-ranging benefits to households (Katz, Kling, and Liebman Citation2007; Ludwig et al. Citation2013; Chetty, Hendren, and Katz Citation2016). Reducing residential segregation may be a positive externality resulting from school choice, that would be reversed by returning to a neighbourhood schools policy. Returning to a neighbourhood schools policy may change segregation at the school-level by little, while increasing segregation at the neighbourhood level, with potentially adverse consequences for more disadvantaged groups.

Alternative policies for increasing equality of access and reducing segregation in schools should be considered, such as the introduction of fair-banding, marginal lotteries or quotas. Fair-banding, where an equal proportion of pupils from across ability bands is admitted to the school, could be expanded across England, as considered by Hamnett and Butler (Citation2011) and Hamnett and Butler (Citation2013). Hamnett and Butler (Citation2013) state that fair banding ‘appears to have much to commend it in terms of overcoming the role of distance-based allocational systems’, although Weekes-Bernard (Citation2007) notes the potential for parents (particularly those with English as an Additional Language) to misunderstand fair banding as a selective, 11 + style, admissions test.

There are other non-geographical admissions arrangements, such as lotteries for over-subscribed schools. This policy has been trialled in Brighton and Hove (see Allen, Burgess, and McKenna Citation2013) and was vehemently opposed by residents in formerly desirable catchment areas. Local pressure meant that the lottery became district-wide rather than LA-wide, with ‘district’ arguably gerrymandered to retain segregation between higher and lower attaining schools.

These political problems are noted by Hamnett and Butler (Citation2013) as a significant barrier to implementation. Parents may also be opposed to the uncertainty created by lotteries (Vowden and James Citation2012) and mourn the loss of local schools that serve as a community for many parents, particularly of primary school age children (one reason for attaining the ‘right mix’ of children is to form friendships with the ‘right mix’ of parents). Burgess, Greaves, and Vignoles (Citation2020) consider the feasibility of ‘marginal ballots’ – where a substantial proportion of school places would be allocated as normal, and the remaining places would be reserved for a random draw among unaccepted applicants – and a simple priority for disadvantaged families, or reserved places for applicants from less well-off backgrounds. Burgess, Greaves, and Vignoles (Citation2020) state that:

Our personal view of the evidence is that there is much to recommend a marginal ballot approach, with perhaps 10% or 20% of places reserved for non-priority applicants. However, how the ballot is communicated to potential applicants is also key to avoid a rejection of a “postcode lottery” approach which is perceived to be a major problem in other public services.

Even a relatively modest reform – such as a controlled choice system designed to ensure that the proportion of children eligible for free school meals in every Hammersmith & Fulham primary school fell between 25 and 50% – might prompt a significant exodus of middle-class parents from the local state system. The most popular schools in the study area had lower proportions than that, and for many respondents this was an important part of their appeal.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Access to these data was provided by the Department for Education, through the National Pupil Database (NPD) application process. These data are available to ONS Approved Researchers through the Secure Research Service.

Notes

1 The proportion of pupils that apply to a school outside their home LA varies across regions, from 4% in the North East to 21% in London. The full distribution is as follows: North East: 4%; East: 5%; Yorkshire: 5%; South East: 6%; North West: 7%; South West: 7%; East Midlands: 7%; West Midlands: 10%; London: 21%.

2 Secondary school aged pupils are eligible for free school transport if they attend their ‘nearest suitable school’ and that school is at least three miles from their home, or there is no safe walking route to that school, or the pupil has a special educational need, disability or mobility problem that prevents them from walking to school (DfE (Citation2022)). Pupils from low-income families have slightly more generous free transport provision: if they attend one of their 3 nearest suitable schools, which is between 2 and 6 miles from their home, or, a school between 2 and 15 miles away chosen because of the family's religion of belief (DfE (Citation2022)).

3 The negative coefficient for London has a larger magnitude than the positive coefficient for Urban, implying that the net effect is lower segregation by ethnic group in the capital city.

References

- Abdulkadiroğlu, Atila, Nikhil Agarwal, and Parag A. Pathak. 2017. “The Welfare Effects of Coordinated Assignment: Evidence from the New York City High School Match.” American Economic Review 107 (12): 3635–3689. doi:10.1257/aer.20151425.

- Abdulkadiroğlu, Atila, Parag A. Pathak, Jonathan Schellenberg, and Christopher R. Walters. 2020. “Do Parents Value School Effectiveness?” American Economic Review 110 (5): 1502–1539. doi:10.1257/aer.20172040.

- Allen, Rebecca. 2007. “Allocating Pupils to Their Nearest Secondary School: The Consequences for Social and Ability Stratification.” Urban Studies 44 (4): 751–770. doi:10.1080/00420980601184737.

- Allen, Rebecca, Simon Burgess, Russell Davidson, and Frank Windmeijer. 2015. “More Reliable Inference for the Dissimilarity Index of Segregation.” The Econometrics Journal 18 (1): 40–66. doi:10.1111/ectj.12039.

- Allen, Rebecca, Simon Burgess, and Leigh McKenna. 2013. “The Short-run Impact of Using Lotteries for School Admissions: Early Results from Brighton and Hove’s Reforms.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (1): 149–166. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00511.x.

- Allen, Rebecca, and Anna Vignoles. 2007. “What Should an Index of School Segregation Measure?” Oxford Review of Education 33 (5): 643–668. doi:10.1080/03054980701366306.

- Ball, Stephen J. 2003. Class Strategies and the Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage. London: Routledge.

- Ball, Stephen J., Richard Bowe, and Sharon Gewirtz. 1995. “Circuits of Schooling: A Sociological Exploration of Parental Choice of School in Social Class Contexts.” The Sociological Review 43 (1): 52–78. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1995.tb02478.x.

- Baum-Snow, Nathaniel, and Byron F. Lutz. 2011. “School Desegregation, School Choice, and Changes in Residential Location Patterns by Race.” American Economic Review 101 (7): 3019–3046. doi:10.1257/aer.101.7.3019.

- Bayer, Patrick, Fernando Ferreira, and Robert McMillan. 2007. “A Unified Framework for Measuring Preferences for Schools and Neighborhoods.” Journal of Political Economy 115 (4): 588–638. doi:10.1086/522381.

- Bernelius, Venla, and Mari Vaattovaara. 2016. “Choice and Segregation in the ‘Most Egalitarian’ Schools: Cumulative Decline in Urban Schools and Neighbourhoods of Helsinki, Finland.” Urban Studies 53 (15): 3155–3171. doi:10.1177/0042098015621441.

- Bernelius, Venla, and Katja Vilkama. 2019. “Pupils on the Move: School Catchment Area Segregation and Residential Mobility of Urban Families.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3095–3116. doi:10.1177/0042098019848999.

- Bertoni, Marco, Stephen Gibbons, and Olmo Silva. 2021. “School Choice During a Period of Radical School Reform. Evidence from Academy Conversion in England.” Economic Policy. doi:10.1093/epolic/eiaa023.

- Beuermann, Diether, C. Kirabo Jackson, Laia Navarro-Sola, and Francisco Pardo. 2018. What is a Good School, and Can Parents Tell? Evidence on the Multidimensionality of School Output. Working Paper, Working Paper Series 25342. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w25342 http://www.nber.org/papers/w25342.

- Bifulco, Robert, and Helen F. Ladd. 2007. “School Choice, Racial Segregation, and Test-Score Gaps: Evidence from North Carolina's Charter School Program*” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 26 (1): 31–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30164083. doi:10.1002/pam.20226

- Billings, Stephen B., J. David, and Jonah Rockoff. Deming. 2014. “School Segregation, Educational Attainment, and Crime: Evidence from the End of Busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (1): 435–476. doi:10.1093/qje/qjt026.

- Billings, Stephen B., David J. Deming, and Stephen L. Ross. 2019. “Partners in Crime.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11 (1): 126–150. doi:10.1257/app.20170249.

- Black, Sandra E. 1999. “Do Better Schools Matter? Parental Valuation of Elementary Education.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (2): 577–599. doi:10.1162/003355399556070.

- Black, Sandra E., and Stephen Machin. 2011. “Chapter 10 - Housing Valuations of School Performance.” in Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann, 3:485–519. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00010-7.

- Bonal, Xavier, Adrián Zancajo, and Rosario Scandurra. 2019. “Residential Segregation and School Segregation of Foreign Students in Barcelona.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3251–3273. doi:10.1177/0042098019863662.

- Borghans, Lex, Bart H. H. Golsteyn, and Ulf Zölitz. 2015. “Parental Preferences for Primary School Characteristics.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 15. doi:10.1515/bejeap-2014-0032.

- Boterman, Willem R. 2019. “The Role of Geography in School Segregation in the Free Parental Choice Context of Dutch Cities.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3074–3094. doi:10.1177/0042098019832201.

- Boterman, Willem R. 2021. “Socio Spatial Strategies of School Selection in a Free Parental Choice Context.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. doi:10.1111/tran.12454.

- Boustan, Leah. 2012. “The Oxford Handbook of Urban Economics and Planning” in Nancy Brooks, Kieran Donaghy, and Gerrit-Jan Knaap (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Urban Economics and Planning, 318–339. Oxford: Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195380620.013.0015.

- Böhlmark, Anders, Helena Holmlund, and Mikael Lindahl. 2016. “Parental Choice, Neighbourhood Segregation or Cream Skimming? An Analysis of School Segregation After a Generalized Choice Reform.” Journal of Population Economics 29 (4): 1155–1190. doi:10.1007/s00148-016-0595-y.

- Bridge, Gary. 2006. “It’s not Just a Question of Taste: Gentrification, the Neighbourhood, and Cultural Capital.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (10): 1965–1978. doi:10.1068/a3853.

- Brunner, Eric J., Sung-Woo Cho, and Randall Reback. 2012. “Mobility, Housing Markets, and Schools: Estimating the Effects of Inter-District Choice Programs.” Journal of Public Economics 96 (7): 604–614. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.04.002.

- Bunar, Nihad. 2010. “The Geographies of Education and Relationships in a Multicultural City” Acta Sociologica 53 (2): 141–159. doi:10.1177/0001699310365732.

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, and Anna Vignoles. 2019. “School Choice in England: Evidence from National Administrative Data.” Oxford Review of Education 45 (5): 690–710. doi:10.1080/03054985.2019.1604332.

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, and Anna Vignoles. 2020. School Places: A Fair Choice? School Choice, Inequality and Options for Reform of School Admissions in England.

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, Anna Vignoles, and Deborah Wilson. 2011. “Parental Choice of Primary School in England: What Types of School do Different Types of Family Really Have Available to Them?” Policy Studies 32 (5): 531–547. doi:10.1080/01442872.2011.601215.

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, Anna Vignoles, and Deborah Wilson. 2015. “What Parents Want: School Preferences and School Choice.” The Economic Journal 125 (587): 1262–1289. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12153.

- Burgess, Simon, and Lucinda Platt. 2021. “Inter-ethnic Relations of Teenagers in England’s Schools: The Role of School and Neighbourhood Ethnic Composition.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 2011–2038. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1717937.

- Burgess, Simon, Deborah Wilson, and Ruth Lupton. 2005. “Parallel Lives? Ethnic Segregation in Schools and Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 42 (7): 1027–1056. doi:10.1080/00420980500120741.

- Butler, Tim, and Chris Hamnett. 2007. “The Geography of Education: Introduction.” Urban Studies 44 (7): 1161–1174. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43197619. doi:10.1080/00420980701329174

- Butler, Tim, and Gary Robson. 2003. “Plotting the Middle Classes: Gentrification and Circuits of Education in London.” Housing Studies 18 (1): 5–28. doi:10.1080/0267303032000076812.

- Byrne, Bridget. 2006. “In Search of a ‘Good Mix’: ‘Race’, Class, Gender and Practices of Mothering.” Sociology 40 (6): 1001–1017. doi:10.1177/0038038506069841.

- Byrne, Bridget. 2009. “Not Just Class: Towards an Understanding of the Whiteness of Middle-Class Schooling Choice.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (3): 424–441. doi:10.1080/01419870802629948.

- Calsamiglia, Caterina, Chao Fu, and Maia Güell. 2020. “Structural Estimation of a Model of School Choices: The Boston Mechanism Versus Its Alternatives.” Journal of Political Economy 128 (2): 642–680. doi:10.1086/704573.

- Calsamiglia, Caterina, and Maia Güell. 2018. “Priorities in School Choice: The Case of the Boston Mechanism in Barcelona.” Journal of Public Economics 163: 20–36. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.04.011.

- Calsamiglia, Caterina, Guillaume Haeringer, and Flip Klijn. 2010. “Constrained School Choice: An Experimental Study.” American Economic Review 100 (4): 1860–1874. doi:10.1257/aer.100.4.1860.

- Calsamiglia, Caterina, Francisco Martínez-Mora, and Antonio Miralles. 2015. School Choice Mechanisms, Peer Effects and Sorting. Discussion Papers in Economics 15/01. Leicester: Department of Economics, University of Leicester. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:lec:leecon:15/01.

- Cantillon, Estelle. 2017. “Broadening the Market Design Approach to School Choice.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (4): 613–634. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grx046.

- Chakrabarti, Rajashri, and Joydeep Roy. 2015. “Housing Markets and Residential Segregation: Impacts of the Michigan School Finance Reform on Inter- and Intra-District Sorting.” Journal of Public Economics 122: 110–132. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.08.007.

- Cheshire, Paul, and Stephen Sheppard. 2004. “Capitalising the Value of Free Schools: The Impact of Supply Characteristics and Uncertainty.” The Economic Journal 114 (499): F397–F424. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00252.x.

- Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. 2016. “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” American Economic Review 106 (4): 855–902. doi:10.1257/aer.20150572.

- Clark, W. A. V., F. M. Dieleman, and L. de Klerk. 1992. “School Segregation: Managed Integration or Free Choice?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 10 (1): 91–103. doi:10.1068/c100091.

- Clotfelter, Charles T. 2001. “Are Whites Still Fleeing? Racial Patterns and Enrollment Shifts in Urban Public Schools, 1987–1996.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (2): 199–221. doi:10.1002/pam.2022.

- Cordini, Marta, Andrea Parma, and Costanzo Ranci. 2019. “‘White Flight’ in Milan: School Segregation as a Result of Home-to-School Mobility.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3216–3233. doi:10.1177/0042098019836661.

- (DfE (2022)). www.gov.uk/free-school-transport

- Duncan, Otis D., and Beverly Duncan. 1955. “A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes.” American Sociological Review 20 (2): 210–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2088328. doi:10.2307/2088328

- Durlauf, Steven. 2004. “Neighborhood Effects.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, vol. 4, edited by J. V. Henderson and J.-F. Thisse, 2173–2242. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Elacqua, Gregory, Mark Schneider, and Jack Buckley. 2006. “School Choice in Chile: Is It Class or the Classroom?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 25 (3): 577–601. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30162742. doi:10.1002/pam.20192

- Epple, Dennis N., and Richard Romano. 2003. “Neighborhood Schools, Choice, and the Distribution of Educational Benefits.” In in The Economics of School Choice, edited by Caroline M. Hoxby, 227–286. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10090.

- Fack, Gabrielle, and Julien Grenet. 2010. “When do Better Schools Raise Housing Prices? Evidence from Paris Public and Private Schools.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (1): 59–77. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.10.009.

- Fack, Gabrielle, Julien Grenet, and Yinghua He. 2019. “Beyond Truth-Telling: Preference Estimation with Centralized School Choice and College Admissions.” American Economic Review 109 (4): 1486–1529. doi:10.1257/aer.20151422.

- Ferreyra, Maria Marta. 2007. “Estimating the Effects of Private School Vouchers in Multidistrict Economies.” American Economic Review 97 (3): 789–817. doi:10.1257/aer.97.3.789.

- Friedman, Milton. 1955. “The Role of Government in Education.” In in Economics and the Public Interest, edited by Robert A. Solo, 123–144. NJ: Rutgers University Press New Brunswick.

- Gamoran, Adam, and Brian P. An. 2016. “Effects of School Segregation and School Resources in a Changing Policy Context.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 38 (1): 43–64. doi:10.3102/0162373715585604.

- Gewirtz, Sharon, Stephen J. Ball, and Richard Bowe. 1994. “Parents, Privilege and the Education Market-Place.” Research Papers in Education 9 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1080/0267152940090102.

- Gibbons, Stephen, and Stephen Machin. 2008. “Valuing School Quality, Better Transport, and Lower Crime: Evidence from House Prices.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24 (1): 99–119. https://ideas.repec.org/a/oup/oxford/v24y2008i1p99-119.html. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn008

- Gibbons, Stephen, Stephen Machin, and Olmo Silva. 2013. “Valuing School Quality Using Boundary Discontinuities.” Journal of Urban Economics 75: 15–28. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2012.11.001.

- Glazerman, Steven, and Dallas Dotter. 2017. “Market Signals: Evidence on the Determinants and Consequences of School Choice from a Citywide Lottery.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39 (4): 593–619. doi:10.3102/0162373717702964.

- Goldstein, Harvey, and Philip Noden. 2003. “Modelling Social Segregation.” Oxford Review of Education 29 (2): 225–237. doi:10.1080/0305498032000080693.

- Gorard, Stephen, and John Fitz. 2000. “Investigating the Determinants of Segregation Between Schools.” Research Papers in Education 15 (2): 115–132. doi:10.1080/026715200402452.

- Guryan, Jonathan. 2004. “Desegregation and Black Dropout Rates.” American Economic Review 94 (4): 919–943. doi:10.1257/0002828042002679.

- Haeringer, Guillaume, and Flip Klijn. 2009. “Constrained School Choice.” Journal of Economic Theory 144 (5): 1921–1947. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2009.05.002.

- Hamnett, Chris, and Tim Butler. 2011. “‘Geography Matters’: The Role Distance Plays in Reproducing Educational Inequality in East London.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (4): 479–500. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00444.x.

- 317–330. doi:10.1080/03050068.2013.807165.

- Hanushek, Eric A., John F. Kain, and Steven G. Rivkin. 2009. “New Evidence About Brown v. Board of Education: The Complex Effects of School Racial Composition on Achievement” Journal of Labor Economics 27 (3): 349–383. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086600386. doi:10.1086/600386

- Harris, Richard, and Ron Johnston. 2020. Ethnic Segregation Between Schools: Is it Increasing or Decreasing in England? Bristol: Policy Press.

- Harris, Douglas N, and Matthew F Larsen. 2019. The Identification of Schooling Preferences: Methods and Evidence from Post-Katrina New Orleans. Technical Report. Technical Report. New Orleans: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans.

- Hastings, Justine, Thomas J Kane, and Douglas O Staiger. 2009. “Heterogeneous Preferences and the Efficacy of Public School Choice.” NBER Working Paper 2145.

- He, Yinghua. 2017. Gaming the Boston School Choice Mechanism in Beijing. Technical Report. TSE Working Paper.

- Hobbs, Graham, and Anna Vignoles. 2010. “Is Children’s Free School Meal ‘Eligibility’ a Good Proxy for Family Income?” British Educational Research Journal 36 (4): 673–690. doi:10.1080/01411920903083111.

- Hollingworth, Sumi, and Katya Williams. 2010. “Multicultural Mixing or Middle-Class Reproduction? The White Middle Classes in London Comprehensive Schools.” Space and Polity 14 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1080/13562571003737767.

- Hoxby, Caroline. 2003. “School Choice and School Competition: Evidence from the United States.” Swedish Economic Policy Review 10 (3): 9–65.

- Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Miguel Urquiola. 2006. “The Effects of Generalized School Choice on Achievement and Stratification: Evidence from Chile’s Voucher Program.” Journal of Public Economics 90 (8): 1477–1503. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.11.002.

- Jenkins, Stephen P., John Micklewright, and Sylke V. Schnepf. 2008. “Social Segregation in Secondary Schools: How Does England Compare with Other Countries?” Oxford Review of Education 34 (1): 21–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20462369. doi:10.1080/03054980701542039

- Johnson, Rucker C. 2011. Long-run Impacts of School Desegregation & School Quality on Adult Attainments. Working Paper, Working Paper Series 16664. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w16664. http://www.nber.org/papers/w16664.

- Karsten, Sjoerd, Guuske Ledoux, Jaap Roeleveld, Charles Felix, and DorothÉ Elshof. 2003. “School Choice and Ethnic Segregation.” Educational Policy 17 (4): 452–477. doi:10.1177/0895904803254963.

- Katz, Lawrence, Jeffrey Kling, and Jeffrey Liebman. 2007. “Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects.” Econometrica 75: 83–119. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2007.00733.x.

- Ladd, Helen F, and Edward B Fiske. 2001. “The Uneven Playing Field of School Choice: Evidence from new Zealand.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1002/1520-6688(200124)20:1<43::AID-PAM1003>3.0.CO;2-4.

- Leech, Dennis, and Erick Campos. 2003. “Is Comprehensive Education Really Free? A Case-Study of the Effects of Secondary School Admissions Policies on House Prices in one Local Area.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 166 (1): 135–154. doi:10.1111/1467-985X.00263.

- Ludwig, Jens, Greg J. Duncan, Lisa A. Gennetian, Lawrence F. Katz, Ronald C. Kessler, Jeffrey R. Kling, and Lisa Sanbonmatsu. 2013. “Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Low-Income Families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity.” American Economic Review 103 (3): 226–231. doi:10.1257/aer.103.3.226.

- Lutz, Byron. 2011. “The End of Court-Ordered Desegregation.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3 (2): 130–168. doi:10.1257/pol.3.2.130.

- Machin, Stephen, and Kjell G Salvanes. 2016. “Valuing School Quality via a School Choice Reform.” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 118 (1): 3–24. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:bla:scandj:v:118:y:2016:i:1:p:3-24. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12133

- Makles, Anna, and Kerstin Schneider. 2015. “Much Ado About Nothing? The Role of Primary School Catchment Areas For Ethnic School Segregation: Evidence from a Policy Reform.” German Economic Review 16 (2): 203–225. doi:10.1111/geer.12048.

- Maloutas, Thomas. 2007. “Middle Class Education Strategies and Residential Segregation in Athens.” Journal of Education Policy 22 (1): 49–68. doi:10.1080/02680930601065742.

- Manski, Charles F. 1993. “Identification of Endogenous Social Effects: The Reflection Problem.” The Review of Economic Studies 60 (3): 531–542. doi:10.2307/2298123.

- Nechyba, Thomas J. 2000. “Mobility, Targeting, and Private-School Vouchers.” American Economic Review 90 (1): 130–146. http://www.jstor.org/stable/117284. doi:10.1257/aer.90.1.130

- Nguyen-Hoang, Phuong, and John Yinger. 2011. “The Capitalization of School Quality Into House Values: A Review.” Journal of Housing Economics 20 (1): 30–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2011.02.001.

- Nielsen, Rikke Skovgaard, and Hans Thor Andersen. 2019. “Ethnic School Segregation in Copenhagen: A Step in the Right Direction?” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3234–3250. doi:10.1177/0042098019847625.

- Noden, Philip. 2000. “Rediscovering the Impact of Marketisation: Dimensions of Social Segregation in England’s Secondary Schools, 1994-99.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 21 (3): 371–390. doi:10.1080/713655353.

- Noreisch, Kathleen. 2007. “School Catchment Area Evasion: The Case of Berlin, Germany.” Journal of Education Policy 22 (1): 69–90. doi:10.1080/02680930601065759.

- Oberti, Marco, and Yannick Savina. 2019. “Urban and School Segregation in Paris: The Complexity of Contextual Effects on School Achievement: The Case of Middle Schools in the Paris Metropolitan Area.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3117–3142. doi:10.1177/0042098018811733.

- Oh, Sun Jung, and Hosung Sohn. 2019. “The Impact of the School Choice Policy on Student Sorting: Evidence from Seoul, South Korea.” Policy Studies: 1–22. doi:10.1080/01442872.2019.1618807.

- Oosterbeek, Hessel, 2021. “Preference Heterogeneity and School Segregation.” Journal of Public Economics 197. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104400.

- Östh, John, Eva Andersson, and Bo Malmberg. 2013. “School Choice and Increasing Performance Difference: A Counterfactual Approach.” Urban Studies 50 (2): 407–425. doi:10.1177/0042098012452322.

- Pathak, Parag A., and Tayfun Sönmez. 2013. “School Admissions Reform in Chicago and England: Comparing Mechanisms by Their Vulnerability to Manipulation.” American Economic Review 103 (1): 80–106. doi:10.1257/aer.103.1.80.

- European Sociological Review 26 (3): 319–335. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp024.

- Rangvid, Beatrice Schindler. 2007. “Living and Learning Separately? Ethnic Segregation of School Children in Copenhagen.” Urban Studies 44 (7): 1329–1354. doi:10.1080/00420980701302338.

- Rao, Gautam. 2019. “Familiarity Does Not Breed Contempt: Generosity, Discrimination, and Diversity in Delhi Schools.” American Economic Review 109 (3): 774–809. doi:10.1257/aer.20180044.

- Reardon, Sean F, and John T Yun. 2003. “Integrating Neighborhoods, Segregating Schools: The Retreat from School Desegregation in the South, 1990-2000.” North Carolina Law Review 81: 1563–1596.

- Reay, Diane, and Stephen J. Ball. 1998. “‘Making Their Minds Up’: Family Dynamics of School Choice.” British Educational Research Journal 24 (4): 431–448. doi:10.1080/0141192980240405.

- Reay, Diane, and Helen Lucey. 2004. “Stigmatised Choices: Social Class, Social Exclusion and Secondary School Markets in the Inner City.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 12 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1080/14681360400200188.

- Reber, Sarah J. 2005. “Court-Ordered Desegregation.” Journal of Human Resources XL: 559–590. doi:10.3368/jhr.XL.3.559.

- Reber, Sarah J. 2010. “School Desegregation and Educational Attainment for Blacks.” Journal of Human Resources 45 (4): 893–914. doi:10.1353/jhr.2010.0028.

- Saporito, Salvatore. 2003. “Private Choices, Public Consequences: Magnet School Choice and Segregation by Race and Poverty.” Social Problems 50 (2): 181–203. doi:10.1525/sp.2003.50.2.181.

- Saporito, Salvatore, and Deenesh Sohoni. 2007. “Mapping Educational Inequality: Concentrations of Poverty among Poor and Minority Students in Public Schools.” Social Forces 85 (3): 1227–1253. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0055.

- Schneider, Mark, and Jack Buckley. 2002. “What Do Parents Want from Schools? Evidence from the Internet.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 24 (2): 133–144. doi:10.3102/01623737024002133.

- Schneider, Kerstin, Claudia Schuchart, Horst Weishaupt, and Andrea Riedel. 2012. “The Effect of Free Primary School Choice on Ethnic Groups — Evidence from a Policy Reform.” European Journal of Political Economy 28 (4): 430–444. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2012.05.002.

- Söderström, Martin, and Roope Uusitalo. 2010. “School Choice and Segregation: Evidence from an Admission Reform.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 112 (1): 55–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40587796. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9442.2009.01594.x

- Taylor, Chris. 2009. “Choice, Competition, and Segregation in a United Kingdom Urban Education Market.” American Journal of Education 115 (4): 549–568. doi:10.1086/599781.

- Taylor, Chris. 2018. “The Reliability of Free School Meal Eligibility as a Measure of Socio-Economic Disadvantage: Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study in Wales.” British Journal of Educational Studies 66 (1): 29–51. doi:10.1080/00071005.2017.1330464.

- Thrupp, Martin. 2007. “School Admissions and the Segregation of School Intakes in New Zealand Cities.” Urban Studies 44 (7): 1393–1404. doi:10.1080/00420980701302361.

- Vowden, Ki James. 2012. “Safety in Numbers? Middle-Class Parents and Social mix in London Primary Schools.” Journal of Education Policy 27 (6): 731–745. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.664286.

- Walker, Ian, and Matthew Weldon. 2020. School Choice, Admission, and Equity of Access: Comparing the Relative Access to Good Schools in England. Technical Report.

- Weekes-Bernard, Debbie. 2007. School Choice and Ethnic Segregation: Educational Decision-Making Among Black and Minority Ethnic Parents; a Runnymeade Report. London: Runnymede Trust.

- Wilson, Deborah, and Gary Bridge. 2019. “School Choice and the City: Geographies of Allocation and Segregation.” Urban Studies 56 (15): 3198–3215. doi:10.1177/0042098019843481.