ABSTRACT

Visitors’ criticisms demand a shift from passive, encyclopaedic exhibitions with curatorial authority, to ones that engage visitors and place them at the centre of focus. This has ignited a change in approaches to exhibition design. One of them is the employment of immersive approaches together with strong storytelling, which can create memorable experiences and redefine the visitor experience. This study investigates the design and production process behind immersive exhibitions, which requires the close collaboration of multidisciplinary experts.

Introduction

For decades, exhibitions employed an encyclopaedic approach with curatorial authority and material objects in order to achieve their educational purposes and assist visitors’ learning experience (Muller, Edmonds, and Connell Citation2006; Wang and Lei Citation2016). Such exhibitions have been criticized by visitors for restricting their participation exclusively to observation, something that affects their efficiency in the process of discovery, while diminishing their experiences (Carrozzino and Bergamasco Citation2017). However, with the evolution of learning technologies and cultural informatics, approaches to museum and art exhibition design have changed as well. Technology-driven and multi-sensory design emerged as innovative ways of offering narrative through experience (Dal Falco and Vassos Citation2017). The technology-backed narrative experience (Dal Falco and Vassos Citation2017) started taking advantage of visual and audio materials such as images, objects, sound, music and high-tech hardware like holograms or touch screens (Wang and Lei Citation2016), making museums and art galleries hybrid places where the virtual and digital aspects of exhibitions are combined with the physical artefacts (Irace and Ciagà Citation2013). These changes offer the potential to redefine the role of visitors, which in turn might lead them to assume a more active role and co-create and co-produce exhibitions by interacting with their environment and taking a central role in the experience (Barnes and McPherson Citation2019; Muller, Edmonds, and Connell Citation2006). This way, technology has emerged as a tool to make art relevant again, while simultaneously renewing the museum experience (Olesen, Holdgaard, and Laursen Citation2020) and contributing to a ‘new museology’ paradigm that contrasts with the classic collections-centred approach (Desvallées and Mairesse Citation2010).

The changing role of the museum, as embodied by the exhibition design that fuses rigorous education with entertainment, interactivity, play, and participation (Olesen, Holdgaard, and Laursen Citation2020; Wang and Lei Citation2016), triggers a vivid discussion both in academia and the public sector. As Marshall McLuhan has claimed, ‘we are swiftly moving at present from an era when business was our culture into an era when culture will be our business’ (McLuhan Citation2011, 384). Simultaneously, exhibition design connects understandings of our past, the need to generate new knowledge, and inspiring ways to imagine our future, all integral elements in our information-saturated world (Lake-Hammond and Waite Citation2010). In other words, museological practice is trying to keep up with the demands of the digital technology era in which we are living, where the experience is valued more than anything, though not without criticism (Barnes and McPherson Citation2019). Nonetheless, when curators take advantage of the new means available in exhibition design, which enhance interactivity, convey meaning, and tell stories, they can create exhibitions with greater impact in society (Giannini and Bowen Citation2019).

The storytelling of immersive exhibitions is different from the exhibition of tangible objects curated for structured exploration. Accordingly, these new design and production processes usually require a creative talent with altered (from a traditional) range of skills, which in turn reshapes the dynamics of the conventional design process. Increasingly, exhibition design is a collaborative process, bringing creative individuals from different disciplines and backgrounds together (Dal Falco and Vassos Citation2017; Holmlid Citation2007; Vavoula and Mason Citation2017).

Existing research attempts to bridge the gap between academia and contemporary practices in the field, notably by exploring the shift towards a digital culture and identity which blurs the lines of the physical with the digital reality (Barnes and McPherson Citation2019; Giannini and Bowen Citation2019; Irace and Ciagà Citation2013). The present study aims to contribute to the discussion by providing insights into the creative process by breaking down the process of the design and production of storytelling in immersive exhibitions, and incorporating the point of view of those involved in the exhibitions’ development. Therefore, the contribution of this study is threefold: (1) it expands existing knowledge on exhibition design by determining the process behind the creation of narrative immersive exhibitions; (2) it combines diverse narratives of experts from different sides of the creative process and (3) it offers industry practitioners a more in-depth look at the exhibition creative process.

Theory and previous research

Immersive exhibitions

The term immersion has for a long time been almost exclusively linked to the gaming industry. In-game environments, immersion is conceptualized by three levels of involvement in a game: engagement, engrossment and total immersion (Jennett et al. Citation2008), and was often linked with the physical feeling of being in a virtual space (Carrozzino and Bergamasco Citation2010). However, the term cannot be associated solely with gaming as it can refer to a broad spectrum of experiences – from literature and music to learning (Derda Citation2020). Immersion can also be linked to museum exhibitions, where it is defined as a multisensory experience that ‘transports’ visitors to a different time, place or situation and makes them active participants in what they encounter (Gilbert Citation2002). Likewise, Mortensen (Citation2010) described an immersive museum exhibition as one that creates a three-dimensional world by distorting the feeling of time and place, all the while integrating visitors in the experience. Immersion then describes the feeling of being submerged by a completely different reality, able to grasp, absorb, and engross our attention and perception (Gilbert Citation2002). Nevertheless, immersion is neither the outcome of the evolution of digital technologies, nor is it even a new concept, as many researchers have historicized (Bolter and Grusin Citation2000; Grau Citation2003; Ndalianis Citation2000; Stafford, Terpak, and Poggi Citation2001). What is more important in the context of this research, is that it is a new dimension of design that needs to be taken into consideration.

Techniques to immerse audiences and the goal of complete immersion are an ongoing fascination of many artists, curators and theorists (Bartlem Citation2005). Gilbert (Citation2002) identified that museum professionals behind the creation of immersive exhibitions are motivated to create experiences that are more attractive and thus competitive leisure-time options, that are more memorable and engaging, and finally more effective in making meaning and communicating content, all integral factors for museums’ success. In addition, several scholars have argued that pleasurable experiences that utilize all senses in an attempt to offer an immersive event can create lasting impressions and thus favourable memories (Muthiah and Suja Citation2013; Stapleton and Hughes 2005). Those are important for museums’ identity-building, perception-shaping and marketing efforts, while also playing an important role in word-of-mouth advertising (Muthiah and Suja Citation2013). Consequently, immersive methods, with their interactive and engaging possibilities, offer a new aesthetic experience and spectatorship, while transcending the human–technology relationship (Bartlem Citation2005).

Exhibition design and production

Design processes are creative (Ames, Franco, and Frye Citation1997). Creative processes, according to Guilford (Citation1950), refer to the sequence of thoughts and actions that lead to production. Everything, from material objects to immaterial processes, is the outcome of the practice of design, even if it is not immediately observable by the human eye (Margolin Citation1989). The creative process is widely acknowledged to be composed of four steps (Sadler-Smith Citation2015), or better known as Wallas’ ‘four-stage model’, consisting of preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification (Wallas Citation1926). Even though the model was conceptualized decades ago, it has come to be considered fundamental in any creativity research (Sadler-Smith Citation2015). Wallas’ framework is limited, however, because it lacks the required attention to sub-processes and variation according to the domain (Lubart Citation2001), issues that are both crucial in any attempt to define a creative process.

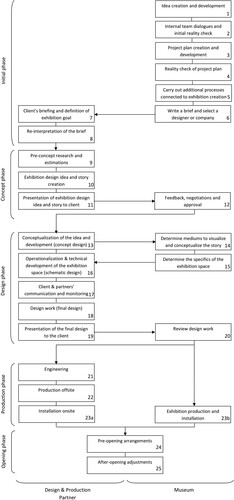

Looking at some contemporary approaches, Lake-Hammond and Waite (Citation2010) proposed a model of exhibition design that maps the roles of curator, designer, and audience by examining the case of the Museum of New Zealand. The map () is a response to the challenges of bridging the gap between expert knowledge and audiences; it highlights the intertwinement of content, concept, context and narrative that guide the exhibition design process, and acts as a preliminary approach to exhibition design (Lake-Hammond and Waite Citation2010).

Figure 1. Model of the exhibition design process (Lake-Hammond and Waite Citation2010).

Dean (Citation2015) explored (what he calls) the ideal process behind exhibition development. Arguing that a clear focus on the development process can enhance all outcomes, Dean identifies five distinct design phases: conceiving of concept, planning and development, production, functional and presenting phase, followed by assessment stages (Dean Citation2015). Dean’s model draws on his personal work experience and established practice in the field of museum project management, which, he argues, is understudied in academic literature. He proposed that each of the stages is composed of product-oriented, management-oriented, and administrative activities (Dean Citation2015). Finally, Dean also acknowledged that this linear model can be somewhat idealistic, when in reality a holistic approach that blends the margins of the separate phases reflects the process more accurately.

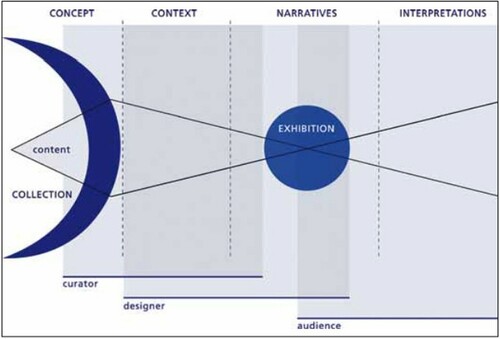

Davies (Citation2010) similarly supported that a clearly defined step-by-step process cannot be determined due to the complexity, creativity and variation of activities between different exhibitions and museums, even though some tasks have to precede others (Davies Citation2010; Macdonald Citation2007). For his study, he investigated traditional exhibitions, which he defined as ‘an exhibition of tangible objects in a venue for a specific time period’ (Citation2010, 307). Thus, Davies identified six non-linear functions behind the creation of an exhibition (), which are: initial idea and development, management and administration, design and production, understanding and attracting an audience, curatorial functions, and planning the associated programme.

Figure 2. The key constituents of creating a traditional exhibition (Davies Citation2010).

However, contemporary museums have moved beyond the sole placement and exhibition of artefacts (Carrozzino and Bergamasco Citation2010). Exhibition design as a discipline includes all manner of efforts at communication and culture accessibility (Carrozzino and Bergamasco Citation2010; Macdonald Citation2007).

One common approach throughout scholarly literature is that an interdisciplinary practice that encompasses a range of professionals contributes to the intertwinement of physical and virtual spaces, content and objects, visitors and information while maintaining the museum’s purpose and attributes (Mason Citation2015).

Collaboration and co-production approaches

Design is often a collaborative and social activity (Warr and O'Neill Citation2005). In the context of exhibitions, collaborative design or, in other words, co-creative, co-design or participatory development, occurs when individuals coming from different disciplines become part of the museum team at different design stages (Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015).

Studies on interdisciplinary collaboration have focused on intermediary objects that facilitate the process (Mason Citation2015; Vavoula and Mason Citation2017). Extending the creative team to include members with multidisciplinary expertise has simultaneously altered the design and production process (Carrozzino and Bergamasco Citation2010). To manage such diverse teams, a great deal of organizing vision and skill is required, provided that the goal-creating an experience that satisfies the visitor-is common among collaborators, but each disciplinary approach differs (Vavoula and Mason Citation2017). Indeed, Carrozzino and Bergamasco (Citation2010) reported on the lack of development tools in multidisciplinary teams, which makes the design process more time- and resource-consuming. Therefore, intermediary design deliverables can be used as means to clarify intentions, negotiate, establish viewpoints and goals and agree on or reject future directions along with the design and production phases (Vavoula and Mason Citation2017). Those deliverables are defined as objects that reflect the design stage or problem. For instance, prototyping is a means to support the co-design process and combine knowledge from different experts (Mason Citation2015).

The studies also focused on factors that influence the success of co-designed exhibitions (Ewenstein and Whyte Citation2007; Govier Citation2009; Lynch Citation2011; Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015; Simon Citation2010). In particular, Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen (Citation2015) reported that proactively managing differences in language, disagreements, everyday workflow and organizational culture both contribute to the gap between different teams and influence their effectiveness. Moreover, they underlined the importance of having a consistent strategy throughout all organizational levels when engaging in collaborative development, and allowing the external collaborators the freedom to make choices when needed (Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015).

Another aspect of co-production that was touched upon in the previous analysis has been visitors as co-creators of their experiences (Antón, Camarero, and Garrido Citation2018; Macdonald Citation2007; Minkiewicz, Evans, and Bridson Citation2014; Simon Citation2010; Skydsgaard, Møller Andersen, and King Citation2016; Thyne and Hede Citation2016). Notably, visitor participation or co-production can make museums more relevant and accessible, enable visitor engagement, and enhance the learning experience, all the while addressing the public’s frustration regarding the exclusive and distant nature of cultural institutions (Antón, Camarero, and Garrido Citation2018; Simon Citation2010). Visitors can be co-creators in two ways: either by actively participating (mentally or physically), or by interacting with the environment, other visitors, and museum staff (Antón, Camarero, and Garrido Citation2018). Active participation requires visitors to be able to develop and shape their own experiences physically, emotionally and either as planned by the museum or spontaneously (Antón, Camarero, and Garrido Citation2018). This elevates the role of visitors from mere spectators to active actors and explorers. Deciding on what moments and how visitors will engage with artefacts is an integral dimension of experience design (Muthiah and Suja Citation2013; Simon Citation2010), though this study will focus on other elements of exhibit development.

Method

The study applied a qualitative approach, due to its orientation toward exploration, discovery and inductive logic (Patton Citation2014). Therefore, to examine the design and production process of immersive exhibitions, it was important to gather descriptive information first, and build toward more general patterns afterwards (Patton Citation2014). For this purpose, qualitative research was used to interpret experts’ narratives within their contextual (museum operations) and social spheres (new requirements for experience design and changing roles of museums) (Flick Citation2009).

The present research used semi-structured expert interviews as its method. The targeted interviewees consisted of professionals who work on the design and production of exhibitions. The participants were selected based on four criteria: (1) employment in a Europe-based museum or exhibition design and/or production company, (2) having a highly involved role in exhibition design, (3) having mid-level seniority in their organization (to ensure level of expertise and involvement in decision-making process) and (4) experience in immersive exhibitions development. The researchers’ intent was to focus on the Netherlands, which is known for its museum scene with close to 32 million museum visitors annually. However, as the top exhibition design companies operate in an international market, the sample consisted of representatives from a variety of European companies that have experience working in the Netherlands and in cooperation with Dutch museums and art galleries. The complete list of participants from cultural institutions and design and production companies can be found in .

Table 1. List of interviewees.

To ensure all of the requirements were met, the study employed a purposeful sampling method. The recruitment occurred through cold calling, mining the researchers’ personal networks, and snowball sampling. In total, 14 interviews, lasting between 30 and 60 min, were conducted. The mix of participants offers a range of cultural institutions (n = 6) and production companies (n = 8), and facilitates synergy among diverse perspectives, thus ensuring a deeper understanding of the design process (Tucker Citation2015). The interviewees were offered anonymity.

To guide the semi-structured interview, a topic guide was developed and led the exploration through the themes of: the nature of immersive museum exhibitions, the process of designing and producing exhibitions and issues of multisided co-production. The topic guide was designed to allow flexible, interactive and meaning-making exploration, allowing for the discussion of topics and concepts that might come forth during the interviews. Essentially, the chosen approach allowed for new dimensions of the subject to emerge (Roulston and Choi Citation2018) without presupposing each and every one of them beforehand (Patton Citation2014).

All the interviews were conducted with Skype and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts of the interviews comprised the data that were used to answer the research question. The study applied thematic analysis to the data using a six-phase process proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Atlas.ti was employed to facilitate and organize the analysis process.

Results

I think that is a thing in museum studies, you always learn about working in a museum, but not all the work of an exhibition is being done in a museum. I always call it the onion. There are so many layers around the core (…) so many more companies involved. (Interviewee 1)

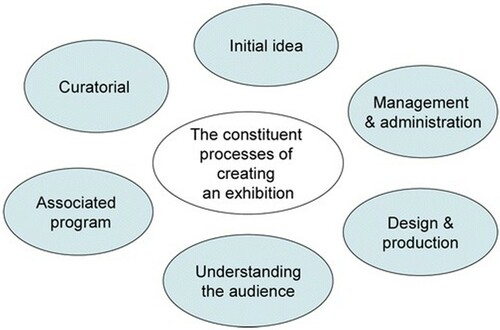

Notably, the sub-steps were described by the interviewees as ‘projects’ that together create an exhibition, and which sometimes progress in a less-than-linear manner or even simultaneously, even though some phases must clearly precede others (Interviewees 2 and 4). Interestingly, interviewees also highlighted how the creative nature of the process makes it difficult to explain it as a straightforward series of steps (Interviewees 2 and 4). For example, each phase must be completed before the next one commences; however, the sub-processes within different phases might at times progress simultaneously. In essence, the design and production process of immersive exhibitions was described by the majority of participants as a multi-stage, creative and collaborative process that requires the involvement of many parties (11 out of 14 experts).

Initial phase

The start of every immersive exhibition originates amongst a museum team where the initial idea is created and developed (step 1). This idea might be generated from a curator or artistic director, it could be the result of a co-production with another museum, or it could be born of suggestions from third parties such as designers, experts or even visitors. This idea is shaped and reshaped throughout the production process, but the museum team is responsible for deciding the final scope of the exhibition.

All museum experts pointed out varying factors that might influence this initial idea generation but placed importance on developing an idea that puts visitors at the heart of the exhibition, one that confronts and challenges audiences, and that fits the rest of the museum portfolio and museum identity. It should be noted also, that all experts placed emphasis on developing an exhibition topic that has some sort of societal relevance, since the ability to generate conversations was directly connected to the production of an audience-centred exhibition. Interviewee 4 argued that ‘we have specific curators who are responsible for these [immersive] kinds of exhibitions. So, they are used to work with the dynamics of an immersive exhibition’.

The initial idea will be the subject of an initial internal reality check (step 2). More specifically, the museum team will have discussions as ‘a sort of peer review’ (Interviewee 3). According to the museum experts, the internal dialogues are expanded to involve broader teams of museum staff, whose feedback will result in a first ‘go’ to start developing the idea (Interviewee 3, 4 and 6). This will bring the museum team to create and develop a project plan (step 3) of the exhibition, in order to make the concept of the exhibition more specific and concrete, help determine a general story that brings across the message, identify what artefacts are needed, estimate the required budget and funding, and select the team that will work on the exhibition.

Next is a reality check of the project plan (step 4), described by a majority of the museum experts as a step to receive the necessary approval before officially commencing the creation of the exhibition (4 out of 6 museum experts). It involves checking the feasibility of the project plan with a museum’s department directors, assessing the availability of budget, people, resources and space, and considering the rest of the exhibition mix.

During the initial phase, the museum team must also carry out additional processes connected to the creation of the exhibition (step 5) as it was stressed by almost all museum experts (5 out of 6 museum experts). These are specific processes for marketing and communication, (possible) loan of artworks, funding and sponsoring, co-creating with foundations and living artists, and creation of educational supplements, programmes, and catalogues. This results in gradually broadening the team to involve all museum departments, while everyone continuously works on the next process of the plan.

All of the museum experts emphasized the importance of cross-domain exhibition creation and explained that they could not possibly carry out the process on their own. Therefore, the museum teams’ last task for the initial phase is to write a brief and ultimately to select a freelance designer or a design and production company (step 6) to assist them for the remaining process (e.g., art handlers, conservators, designers, freelancers, owners of artworks, foundations, technicians, writers, painters, video artists, performers, designers and companies involved in concept creation and curatorial boards). Interviewee 2 argued: ‘We buy in expertise and knowledge and creativity from (…) agencies or artists (…) what we do is we initiate it and we guide it, but we tap into other people’s knowledge, expertise, creativity, contribution to make it work.’ Thus, this step marks the beginning of the collaboration. The role of a design and production partner starts with receiving the brief from the client (the museum) and defining the goals of the exhibition (step 7).

The final step of the initial phase is for the design and production partner to re-interpret the brief (step 8). Interviewees stressed the need to ‘establishing a common language with the client’ in cases when the museum team with whom they work with do not have the experience or knowledge to produce an extensive brief that can guide the process effectively (Interviewee 9) or to ensure common understanding and expectations (Interviewees 10 and 13). Thus, this re-interpretation is necessary to reach a common denominator between the two stakeholders. In addition, Interviewee 7 attributed importance to establishing ‘how important is the educational aspect of the exhibition compared to the entertainment aspect (…) to make sure that this balance is already from the beginning agreed with the client’.

Concept phase

The concept phase begins with some pre-concept research and budget estimates (step 9) by the design and production partner. The majority of the design and production experts stressed the importance of conducting research about the topic and exploring the relevance of the collection before coming up with an exhibition plan, especially when the client does not have a clear vision (5 out of 8 design and production experts).

All design and production experts mentioned that the exhibition design idea and story creation (step 10) is a core element and a crucial moment for the overall process. Ultimately, museums want to create stories that people want to engage with, since every exhibition is a story. Interviewee 3 argued that the concept is equally important as the artwork. The exhibition concept is the outcome of the combined effort of both sets of stakeholders and needs to fit the why, the what, and the who – the target group. The outcome of this step is a grand concept that contains ‘values, emotions, messages and limitations that you are aware of’ (Interviewee 9). The big idea acts as a narrative arc that will be the reference point throughout the creative process. This step also determines the function and emotional sides of this narrative.

Having defined a concept, the next step is the presentation of the exhibition design idea and story for the approval of the museum team (step 11). Simultaneously, the museum team provides regular feedback to their partners, negotiates with them, and gives the approval to move on to the next phase (step 12). Interestingly, all interviewees mentioned the communication between the two stakeholders, but two museum experts described explicitly having a frequent back-and-forth communication with their partners, in a way incorporating the external collaborators into the team.

Design phase

When the design phase commences, both the museum and their production partner collaborate on different exhibition design aspects. A range of activities opens this phase, which can be summarized as the conceptualization of the idea and its development (step 13). The majority of experts used terms such as master planning, sketch design, or concept design to describe the tasks that fall under this step (5 out of 8 design and production experts). All the experts stated that through this step the story is translated to a realistic concept and it is determined how exactly it will come to life. Interviewee 7 argued that ‘The story is something that you have in your mind, that you can write down (…) and the immersive aspect of the exhibition is actually the way you translate the story (…) into reality.’

While discussing this phase, experts often mentioned the importance of the exhibition space (as the design of the story will be influenced by the space it will be installed in), synesthesia (as an immersive exhibition has to stimulate multiple senses at the same time and in a holistic manner), the visitors’ role (understood as everything that the visitor will experience, do, and see in each room), and ‘interaction design’ (how elements of interactivity should work).

Some, like Interviewee 9, also emphasized that the design often exceeds the exhibition itself and should be considered as a broader ecosystem:

You can also connect emotions to what you want people to do. So, for example, if you want people to feel good and then at the end, for example, buy some additional services (…) Then you build like a larger ecosystem that you are not designing, only an exhibition, you are designing (…) an experience which has connected events, a marketing campaign (…) and props that are around that experience.

The next step of the design phase is the operationalization and technical development of the exhibition or schematic design (step 16). ‘A schematic design is really more the technical development of everything inside the exhibition space, inside each room (…) you have to think about lighting, you have to think about the hardware or the computer, the projection, the screen’ (Interviewee 7). Consequently, some experts explained that the concept receives a reality check primarily under the parameters of budget and resource limitations, to make any necessary adjustments (4 out of 8 design and production experts).

As it becomes apparent from the last two steps, the design and production team has to seek advice and collaborate with other experts throughout the design phase. Thus, it is important to have open communication with the museum team, their client (step 17), as it was discussed by all design and production experts. This step is followed by design work, or in other words, creating the final design (step 18). The final design details all aspects of the exhibition in order to create packages of design work that the client can send out to suppliers for bids. Likewise, Interviewee 8 described this process as drawing up scenarios that would result in a definite design, containing a mood board, a keynote, and any kind of scripts for the multimedia.

The completion of the final design work brings us to its presentation to the museum team (step 19) and consequently its review (step 20).

Production phase

Engineering (step 21) is the first step of the implementation of the design, ‘making it technically all feasible’ (Interviewee 10). The next step is the offsite production (step 22), during which the collaboration with production specialists is integral, as most experts stressed (6 out of 8 design and production experts). These collaborators range from production agencies, multimedia experts, renderers, light designers, audiovisual hardware agencies, to furniture builders and many other specialized partners. One of the interviewees went on to explain that specialists make the design stronger by attributing their knowledge and craftsmanship while equating the process to that of making a movie:

The director and scriptwriter have got a big idea and then the other people are giving all the details and make, bring the movie to life, bring the story to life. (…) Together with the client, we are the director (…) so it is a process that we do together. (Interviewee 11)

Opening phase

Reaching the last phase of the creative process of producing immersive exhibitions, once the exhibition is ready, the stakeholders focus on tasks concerning its opening. A specific museum team makes pre-opening arrangements (step 24), such as making sure to invite all members, sponsors, and employees of the museum for the opening night, amongst other considerations. The museum has to also establish a team that is readily available to handle any technical issue that might arise once the exhibition opens (Interviewee 1 and Interviewee 5). In addition, both the museum team and their design collaborator prepare for the opening, put the final touches on the exhibition, and perform a ‘rehearsal’, to ensure that the exhibition serves its purpose and functionality.

Nevertheless, the adjustments and efforts to optimize the exhibition do not stop once the opening is over. Therefore, both the museum and the design company engage in after-opening adjustments (step 25). Interviewee 10 exemplified the review and optimization of an exhibition after its opening:

It means that you track visitors and you even change and improve things when it is opened, just like an app or a digital project. You can change an exhibition after it is open. You do not have to think, well, this is it. And I hope it works.

Finally, the cycle of the creation of an exhibition is completed and a new one has already begun, as the majority of experts emphasized that each creation process must begin even a few years prior to its opening.

Discussion

Design and production model

As it became apparent from the findings, the shift of approaches in exhibition design from curatorial authority toward audience-centred experience through the use of storytelling and immersion is gradually being established as an important principle in modern exhibition design. Nonetheless, previous studies have neglected issues that influence exhibition design, notably paying insufficient attention to the contributions and expertise of designers (Macdonald Citation2007) and the implications of this for the design and production process.

Nevertheless, other scholars have also attempted to map the creative process behind museum exhibitions. Interestingly, the findings of Davies’s (Citation2010) study into traditional exhibitions of tangible objects somewhat seems to contradict the current model. More specifically, Davies (Citation2010) proposed a non-linear model that contains six functions that summarize the activities behind the creation of an exhibition. These are initial idea and development, management and administration, design and production, understanding and attracting an audience, curatorial functions, and planning the associated programme (Davies Citation2010). Even though there are similarities in the activities of each function with the five phases by this study, the approach behind the two models is different, since Davies (Citation2010) did not account for the progression of the process. The findings acknowledged that during a creative process, the sequence of the sub-steps might not always be maintained. However, a non-linear model cannot explicitly describe the interconnections between the phases and their sub-steps, nor offer a logical sequence to the overall process. Therefore, our model depicts a methodical template of the creative process, which is characterized as complex but with sequenced activities, and collaborative but with defined responsibilities and roles.

The five phases, which structure and explain the findings, offer some new insights into the creative process, while at the same time substantiating some of Dean’s (Citation2015) remarks regarding the phases identified in his study of museum exhibitions. More specifically, the concept and production phase are evident in both studies, whereas the design and opening phases contain activities that resemble Dean’s planning and development, and functional and presenting, respectively. According to the findings, the involvement of a wide range of experts in the creative process is integral for the design and production of immersive exhibitions. Thus, the present study offers an alternative account to Dean’s (Citation2015) by showcasing the progression of the five phases and the division of the necessary activities between the museum and the design and production team.

Moreover, the model identified an additional phase that marks the start of the cooperation of (at least) two stakeholders and was highlighted as an important moment during the creative process. Due to the collaboration with external partners, the proposed model provides evidence of the necessary steps that are performed by both stakeholders in order to ensure that the objectives are well defined and understood. For this reason, findings suggest the importance of the museum team to effectively brief their partners, who in turn make sure to establish a mutual understanding with their client. This extends previous studies, which emphasize the significance of proactively addressing differences in backgrounds, disagreements, and lack of knowledge to establish a common language in order to successfully co-design the exhibition (Mason Citation2015; Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015). Hence, the present study offers a visual representation and extends studies of interdisciplinary collaboration (Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015; Olesen, Holdgaard, and Laursen Citation2020) by showcasing the collaboration during the design and production process in the form of steps that concern such activities.

Collaborative nature of the creative process

The identified model emphasizes the involvement of multiple specialists during the different phases of the creative process. It illustrates that the design and production of an immersive exhibition does not solely concern the museum team anymore. The findings of the study are in accordance with Davies (Citation2010) and Dean (Citation2015), whose descriptions of the creation process involves multiple disciplines. More specifically, the findings suggest the interdependence of the role of curators and designers as the main stakeholders, similarly to Lake-Hammond and Waite’s (Citation2010) research. Interestingly, their model presents curators as solely responsible for concept creation, who work on the context of the exhibition together with designers, while designers are ultimately responsible for creating the exhibition on their own. However, the identified model requires the input and close co-operation of both sets of stakeholders throughout the process. Put differently, exhibition design now requires the combined efforts of multiple specialists throughout most of the creative process. This notion coincides with the understanding that a successful exhibition is the result of a balanced collaboration between curators and designers (Davies Citation2010). For this reason, sub-steps depicting the need for an open flow of feedback and communication are present in all design and production phases. In a way, the findings indicate that the museum team is the client who the design and production partner have to please. At the same time, the museum team still preserves control of the creative process, since they are the ones who decide if the outcome of each phase satisfies them enough to give their approval and continue with the next design and production phase.

The necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration is evident. This is also widely acknowledged in a range of studies (Davies Citation2010; Dean Citation2015; Mygind, Hällman, and Bentsen Citation2015; Olesen, Holdgaard, and Laursen Citation2020). Nonetheless, the proliferation of the different roles required by exhibition design and production has been filled by external collaborators, while the core museum team has not expanded, as might have been expected. Consequently, the findings suggest that specialists from different disciplines temporarily collaborate with the museum team during the different phases. Museums have always worked collaboratively, working together with artists to co-create exhibitions of their work or collaborating with other museums and lenders of artworks. However, incorporating external collaborators early on into the creative process who do not only bring the ideas of the museum team to life, but are actively involved in nearly all aspects of design and production, marks a shift in the broader exhibition process. At the same time, it is important to notice that even though the proposed model explores the expanded collaboration practice, the visitors’ co-creation is usually limited to the way they consume the exhibition after its opening. Museums’ approach to being more inclusive and engaging visitors more by placing them at the centre of an immersive exhibition design, does not make visitors equal co-creators and co-producers. In that sense the developed design model is similar to more traditional ones and contrasts with the alternative ways to design and produce exhibitions through the ‘democratisation of the museums’ content and programming’ (Barnes and McPherson Citation2019, 261) approach, as it could be seen in the example of the Dutch ‘Temporary Museum’, where the exhibition objects were created and curated together with refugees.

Story-driven immersion

Storytelling is stronger if it goes through all the senses (…) We share a story through all the senses in that space and anchor people in a moment of wonder in that space. (Interviewee 6)

In addition, the conceptualization and operationalization of an immersive exhibition is not dependent on technology, but rather is assisted by it. This finding is consistent with scholars’ arguments that immersion does not equal the use of digital technologies (Bartlem Citation2005; Giannini and Bowen Citation2019). Accordingly, technology strengthens exhibition design by supporting the creation of a multi-sensory, visceral, and hence immersive space capable of engaging visitors in the story. Nonetheless, any exhibition requires a level of authenticity, which is provided through the physical artefacts in the exhibition space. This is why technology has a secondary, supportive role and is used only when it can add value to the exhibition concept, a balance that is often distorted when exhibition design is falsely seen as technology-driven. Quite simply, exhibition design is media independent and the pluralism of digital technologies offers a wide range of methods to convey a story.

Conclusion

The present study sought to expand knowledge around the creative process of immersive exhibitions in light of the shifting approaches in museum exhibition design. Our two-sided model offers insights into the necessary stages to create an immersive exhibition. The findings identified five distinct phases (initial, concept, design, production, and opening phase) consisting of 25 steps, which exhibits the necessity of close co-operation between the museum team and their design partner. However, it has to be acknowledged that developing an exhibition in a ‘real-life’ situation might not always follow such a clear-cut, linear process and that the same process might vary depending on the institution, its organizational structure, and the balance between exhibition-related tasks and informal daily activities. For this reason, the current model identifies the creative process as an organized template where each phase is completed before the next one starts, but the sub-steps allow for greater flexibility, creativity and overlap. Thus, the five phases clarify the main tasks and required roles, while establishing the flow of the overall process.

The identified process offers a detailed and expanded model that considers the contributions of new stakeholders, hence making the model a new addition to existing scholarship on the topic. It is important to note that the museum team might lead the process and ultimately have the final say, but the design and production partner’s involvement is integral for the creation of an immersive exhibition since they are active actors who determine the end result as well. Consequently, immersive exhibitions are the outcome of a two-sided process, which require the creative collaboration of both stakeholders who share responsibilities and look for the optimal solutions or sometimes compromise in order to design and produce an exhibition that satisfies all parties.

Additionally, through the study, the role of immersion within the exhibition became clearer. It has been identified as a mean to bring forth the story (exposed through an exhibition) and enhance its inspirational and emotional aspect while offering an additional multisensory layer that surrounds the art and helps visitors submerge in the storyline. For this reason, exhibition design is not technology-driven but story-driven and the varying digital methods are selected only to reinforce the storytelling and create an immersive environment.

The study corresponds to current discussions in the field about the changing role of museums and the need to create more socially relevant exhibitions, with the empirical findings offering a structured model for the creative process behind modern exhibition design. Based on the accounts of experts in the field, immersive elements are employed in most contemporary exhibitions to engage visitors in a story that can have a greater impact on society, without losing their educational purposes in favour of entertainment.

While the study expands our understanding of the process behind the creation of immersive exhibitions, the findings need to be considered within the limitations of the research design. The main limitation lies in a relatively small sample size of experts, which hinders the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the experts were selected due to their ability to provide an extensive account of all phases of the creative process. However, it became clear that an intricate web of collaborators is required along with the design and production process. Consequently, it would be valuable to analyse the accounts of other types of collaborators, given that the present study covered only the points of view of the two main stakeholders (the museum team and their primary design and production partner), in order to discover how they influence our model. Lastly, the interviews were conducted with experts who are based and operate predominantly in Europe. Accordingly, future research could investigate if the proposed model is valid in other regions. Finally, the study confined itself to identifying the creative process associated with creating an immersive exhibition whilst emphasizing the co-operative nature of the model, hence another avenue for research could concern the analysis and implications of the relationships between the many interdisciplinary collaborators.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zoi Popoli

Zoi Popoli is a graduate of the Master Media & Creative Industries program at ESHCC involved in the ‘Smartification of audience experience’ project.

Izabela Derda

Izabela Derda, Ph. D., is a researcher and lecturer at Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication in the Media & Communication Department in Rotterdam, Netherlands. She investigates how new technologies influence transmedia design and reshape content-medium-consumer-creator networks.

References

- Ames, K. L., B. Franco, and L. T. Frye. 1997. Ideas and Images: Developings Interpretive History Exhibits. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers AltaMira Press.

- Antón, C., C. Camarero, and M. J. Garrido. 2018. “Exploring the Experience Value of Museum Visitors as a Co-creation Process.” Current Issues in Tourism 21 (12): 1406–1425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1373753.

- Barnes, P., and G. McPherson. 2019. “Co-creating, Co-producing and Connecting: Museum Practice Today.” Curator: The Museum Journal 62 (2): 257–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12309.

- Bartlem, E. 2005. “Reshaping Spectatorship: Immersive and Distributed Aesthetics.” Fibreculture Journal: Distributed Aesthetics 7), Retrieved from http://www.immersence.com/publications/2005/2005-EBartlem.html.

- Bolter, J. D., and R. Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Carrozzino, M., and M. Bergamasco. 2010. “Beyond Virtual Museums: Experiencing Immersive Virtual Reality in Real Museums.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (4): 452–458. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2010.04.001.

- Dal Falco, F., and S. Vassos. 2017. “Museum Experience Design: A Modern Storytelling Methodology.” The Design Journal 20 (sup.1): S3975–S3983. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352900.

- Davies, S. M. 2010. “The co-Production of Temporary Museum Exhibitions.” Museum Management and Curatorship 25 (3): 305–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2010.498988.

- Dean, D. K. 2015. “Planning for Success: Project Management for Museum Exhibitions.” In The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, 357–378. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118829059.

- Derda, I. 2020. “Od zaangażowania do immersji w aktywacjach sportowych” [from Engagement to Immersion in Sports Activations].” In Chap. 2 in Marketing Sportowy. Profesjonalne Zarządzanie w Sporcie [Sports Marketing. Professional Management in Sports], edited by P. Godlewski and P. Matecki, 39–55. Gdansk: Gdansk University of Physical Education and Sport.

- Desvallées, A., and F. Mairesse. 2010. Key Concepts of Museology. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Ewenstein, B., and J. Whyte. 2007. “Beyond Words: Aesthetic Knowledge and Knowing in Organizations.” Organization Studies 28 (5): 689–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078080.

- Flick, U. 2009. An Introduction to Qualitative Research (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Giannini, T., and J. P. Bowen. 2019. Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research. Cham. CH: Springer.

- Gilbert, H. 2002. “Immersive Exhibitions: What’s the Big Deal?” Visitor Studies Today 5 (3): 10–13.

- Govier, L. 2009. “Leaders in Co-creation? Why and How Museums Could Develop Their Co-creative Practice with the Public, Building on Ideas from the Performing Arts and Other Non-museum Organisations.” Leicester: University of Leicester Research Report 3: 10. Retrieved from http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/museumstudies/rcmg/projects/leaders-in-co-creation/Louise%20Govier%20-%20Clore%20Research%20-%20Leaders%20in%20Co-Creation.pdf.

- Grau, O. 2003. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

- Guilford, J. P. 1950. “Creativity.” American Psychologist 5 (9): 444–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063487.

- Holmlid, S. 2007. “Interaction Design and Service Design: Expanding a Comparison of Design Disciplines.” Nordes 2. Retrieved from https://archive.nordes.org/index.php/n13/article/view/157.

- Irace, F., and G. L. Ciagà. 2013. Design & Cultural Heritage. Milano: Electa.

- Jennett, C., A. L. Cox, P. Cairns, S. Dhoparee, A. Epps, T. Tijs, and A. Walton. 2008. “Measuring and Defining the Experience of Immersion in Games.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 66 (9): 641–661. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.04.004.

- Lake-Hammond, A., and N. Waite. 2010. “Exhibition Design: Bridging the Knowledge gap.” The Design Journal 13 (1): 77–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/146069210X12580336766400.

- Lubart, T. I. 2001. “Models of the Creative Process: Past, Present and Future.” Creativity Research Journal 13 (3-4): 295–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_07.

- Lynch, B. T. 2011. “Custom-made Reflective Practice: Can Museums Realise Their Capabilities in Helping Others Realise Theirs?” Museum Management and Curatorship 26 (5): 441–458. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2011.621731.

- Macdonald, S. 2007. “Interconnecting: Museum Visiting and Exhibition Design.” CoDesign 3 (S1): 149–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701311502.

- Margolin, V. 1989. Design Discourse: History, Theory, Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mason, M. 2015. “Prototyping Practices Supporting Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Digital Media Design for Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30 (5): 394–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1086667.

- McLuhan, M. 2011. The Book of Probes: Marshall McLuhan. Corte Madera, CA: Ginkgo Press.

- Minkiewicz, J., J. Evans, and K. Bridson. 2014. “How Do Consumers Co-create Their Experiences? An Exploration in the Heritage Sector.” Journal of Marketing Management 30 (1-2): 30–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.800899.

- Mortensen, M. F. 2010. “Designing Immersion Exhibits as Border-crossing Environments.” Museum Management and Curatorship 25 (3): 323–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2010.498990.

- Muller, L., E. Edmonds, and M. Connell. 2006. “Living Laboratories for Interactive Art.” CoDesign 2 (4): 195–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880601008109.

- Muthiah, K., and S. Suja. 2013. “Experiential Marketing – A Designer of Pleasurable and Memorable Experiences.” Journal of Business Management & Social Sciences Research 2 (3): 28–34.

- Mygind, L., A. K. Hällman, and P. Bentsen. 2015. “Bridging Gaps Between Intentions and Realities: A Review of Participatory Exhibition Development in Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30 (2): 117–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1022903.

- Ndalianis, A. 2000. “Baroque Perceptual Regimes.” Senses of Cinema 5: 4.

- Olesen, A. R., N. Holdgaard, and D. Laursen. 2020. “Challenges of Practicing Digital Imaginaires in Collaborative Museum Design.” CoDesign, 16, 189–201.

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Roulston, K., and M. Choi. 2018. “Qualitative Interviews.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, edited by U. Flick, 233–249. London: Sage Publications.

- Sadler-Smith, E. 2015. “Wallas’ Four-stage Model of the Creative Process: More Than Meets the eye?” Creativity Research Journal 27 (4): 342–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277.

- Simon, N. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

- Skydsgaard, M. A., H. Møller Andersen, and H. King. 2016. “Designing Museum Exhibits That Facilitate Visitor Reflection and Discussion.” Museum Management and Curatorship 31 (1): 48–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2015.1117237.

- Stafford, B. M., F. Terpak, and I. Poggi. 2001. Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Thyne, M., and A. M. Hede. 2016. “Approaches to Managing Co-production for the Co-creation of Value in a Museum Setting: Whens Authenticity Matters.” Journal of Marketing Management 32 (15-16): 1478–1493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1198824.

- Tucker, E. L. 2015. “Museum Studies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative, edited by P. Leavy, 341–356. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vavoula, G., and M. Mason. 2017. “Digital Exhibition Design: Boundary Crossing, Intermediary Design Deliverables and Processes of Consent.” Museum Management and Curatorship 32 (3): 251–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2017.1282323.

- Wallas, G. 1926. The art of Thought. London: J. Cape.

- Wang, Q., and Y. Lei. 2016. “Minds on for the Wise: Rethinking the Contemporary Interactive Exhibition.” Museum Management and Curatorship 31 (4): 331–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2016.1173575.

- Warr, A., and E. O'Neill. 2005. Understanding Design as a Social Creative Process. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Creativity & Cognition (pp. 118–127). London: ACM. https://doi-org.eur.idm.oclc.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1056224.1056242.