ABSTRACT

Museum managers face mounting pressures to increase and widen audiences, with families often perceived as a key audience requiring particular forms of engagement. The article utilises spatial ethnographic research at a major international art museum (Tate Modern) to examine how family museum practices relate to museum spatial design. Liminal spaces were found to be vital in shaping the experiences of family visitors by affording opportunies for more banal practices (such as playing, sitting, talking, eating and resting). Although they may be partially supported by collection displays, liminal spaces do not usually feature in museum management agendas. As the social purpose of museums continues to be debated, the paper argues for a greater understanding of the full range of affordances of museums for families, paying attention to the significance of different types of museum spaces in mediating experience and the importance of optimising those spaces for greater access.

Introduction

Methods for demonstrating the value of museums for specific audiences continue to evolve (Scott Citation2009). The utilisation of museum space is vital for museum managers seeking to establish legitimacy with stakeholders, whether government funders, grant-giving bodies or the paying public (Lindqvist Citation2012). Among the latter, families are key audiences through which museums discharge their general missions and generate sustainable income (Black Citation2016). Understanding the behaviour of family visitors and how they use museum space is critical for museum managment, especially from a perspective of marketing and positioning their appeal to different types of visitors (Prior Citation2003). This paper explores how family museum practices relate to museum spatial design and the reproduction of family life. It addresses two related research questions: how do families utilise different types of museum spaces, and what are the implications of the associated spatial practices of family museum visits for museum management?

Within the museum studies literature and museums practice, families are often depicted as an audience requiring particular forms of engagement (O’Reilly and Lawrenson Citation2021; Sterry Citation2011; Eardley et al. Citation2018) and methodological complexities can frustrate more extensive research on them (Sterry and Beaumont Citation2006). Among the distinctive body of knowledge on family museum visits, learning is often understood as a key motivator (Black Citation2012) and outcome (Duncan Citation1995; Hooper-Greenhill Citation2007; Moussouri and Hohenstein Citation2017), and this is reflected in family decisions about museum visitation by both parents and children (Cicero and Teichert Citation2018). However, important knowledge gaps persist. First, studies concerned with understanding learning as an outcome of family museum experiences rarely consider learning (or anything else) that may occur when families are not directly engaged with exhibits (Astor-Jack et al. Citation2007). Second, in response to a competitive museum market and the wider leisure industry (Black Citation2005), there have been advances in profiling visitors (Falk Citation2008). Yet, in the rare instances where segmentation techniques have been applied to ‘family’ audience groups, children have been the main focus rather than families (Cicero and Teichert Citation2018) and important intra-familial or group distinctions have been overlooked (Astor-Jack et al. Citation2007). Finally, approaches to understanding family museum experiences are largely concerned with analysis of a museum visit, yet there is an emergent body of work that aims to analyse family museum experiences at the level of family life per se (Garner Citation2015; Hackett Citation2016). The shift in unit of analysis, from the family museum visit towards the practices of family life within the museum, provides a means of recognising alternative systems of value and impact within museums.

Focusing on the practices of family life, this paper explores practices within museum spaces that are categorised as being more or less liminal. The concept of liminality is important here because museums, similar in some respects to tourist destinations, are spaces where ‘existing norms, behaviours and values of home are more open to subversion or abandonment’ (Osman, Johns, and Lugosi Citation2014, 239). By focusing on family practices in spaces that are more or less liminal, as defined by their deviation from museum norms, we seek to understand how family behaviours and museum spaces are co-constituted.

Literature review

The potential interconnections between museum spaces, displays and visitors are vital in the planning and operation of any museum (Lord, Lord, and Martin Citation2012). Once constructed, curatorial decisions about utilising museum spaces are key considerations for museum managers (Communications Design Team Citation1999; Schorch Citation2013). Architecture and spatial layouts combine with displays to form a spatial syntax (Hillier and Tzortzi Citation2006), which act as a condition of meaning-making and is interpreted by visitors through their own frameworks (Schorch Citation2013).

This conceptual focus on spatial syntax has focused attention on the way in which spatial design facilitates visitor movement through the interconnection of spaces. Depending upon the physical layout, museums restrict or enable visitor movement on a continuum between poles of ‘spatially random movement and spatially dictated movement’ (Wineman and Peponis Citation2010, 92). Giving attention to the materiality of museum spaces, Tzortzi (Citation2017) differentiates between: occupation spaces, which cannot be passed through (i.e., cul-de-sacs); control spaces, which control access to other spaces; circulation spaces, which form circular routes; and choice spaces, which have multiple access and egress points allowing users to choose their museum route. Identifications of this nature are based on the configuration of museum spaces and displays and how they are used by visitors. Occupation spaces, for example, which might display spatio-temporary or immersive exhibits, such as sound installations and videos, are ‘spaces that must be lived in and experienced, rather than passed through’ (Tzortzi Citation2017, 497).

Spatial design has behavioural consequences, not only for visitor engagement with museum architecture and displays but also by creating patterns of visitors’ ‘co-presence and co-awareness’ within the visual field (Wineman and Peponis Citation2010, 106). Museum managers now have the opportunity to apply new technologies to facilitate understanding of how visitors move in relation to the spatial morphology of the museum (Yoshimura et al. Citation2014), visitors’ biometric responses (Kirchberg and Tröndle Citation2015) and their visual attention (Jung, Zimmerman, and Koraly Citation2018). Understanding visitor reactions and behaviours in museum spaces is becoming increasingly important because it enables the ‘construction of a hierarchy of messages’ by managers (Wineman and Peponis Citation2010, 87).

Tzortzi’s work, in particularly, demands that attention is paid to museum spaces that are subject to the sensory turn in museum and art practice (Classen Citation2017). Building on the spatial framing of museum research to address family museum practices, the paper now explores two related frameworks, those of embodiment and liminality.

Embodied practices in the museum

Recent research into museum practices has advocated understanding audiences through the lens of embodiment (Kai-Kee, Latina, and Sadoyan Citation2020). Embodiment focuses upon human experience and action expressed through talk and movement, and mediated by the human senses. Paying attention to talk has been trialled as a method of analysing museum experiences, generating scope for exploration of the role of sociality (Tröndle et al. Citation2012) and the body in the museum (Christidou and Pierroux Citation2019). In some cases, research has focused on conversations occurring between family group audiences (Kopczak, Kisiel, and Rowe Citation2015; Vandermaas-Peeler, Massey, and Kendall Citation2016; Callanan et al. Citation2017). These are typically analysed in the context of established pedagogical or cognitive frameworks, with the aim of understanding how people make meaning from museum exhibits (Callanan et al. Citation2017; Ash Citation2003, Citation2004).

Research exploring movement has led to a call for ethnographies of museum visitor conduct (Heath and vom Lehn Citation2004). Movement has been analysed in conjunction with talk to gain a more thorough understanding of the nature of time spent in front of exhibits and displays, and of how family group members might relate to one another thereby supporting intra-group learning and engagement (Zimmerman, Reeve, and Bell Citation2010; Heath and vom Lehn Citation2004; Patel et al. Citation2016; Povis and Crowley Citation2015). Nevertheless, museum experiences are typically regarded as valuable only if they occur in proximity and relation to a display, object or programme (e.g., Heath and vom Lehn Citation2004). Research that breaks with this tradition points to the significance of threshold spaces, such as museum entrances, which perform ‘multiple complex functions, from way-finding and informational exchange, to rule setting and ambience setting’ (Parry, Page, and Moseley Citation2018, 1).

Hetherington (Citation2015) highlights how the role of the spectator’s body relates to museum space. The spectator’s body has been understood as inherently social, time-progressively public, shaped by historically situated manners and one that is walking, looking, and conversing (Duncan Citation1995; Colomina Citation1994; Bennett Citation1995). Leahy (Citation2012, 11) historicises spectatorship, describing it as knowing how to look while also knowing that looking in a museum incorporates ‘knowing how and where to stand, where and how fast to walk, what to say and what not to say, and what not to touch’. Leahy also reminds us that different museums and artworks have produced different normative behaviours, different audience performances, and have occasionally generated audience transgression and resistance. Duncan (Citation1995), drawing upon Bourdieu, Darbel, and Schnapper (Citation1991) notion of the museum as a mechanism of social class reproduction, argues that the socially-distinguishing nature of the art museum and its politicised cultural contents means that it can be conceptualised as a stage set, script and dramatis personae. In this sense, the museum materially situates and represents a complex interplay of social, cultural and political (and potentially economic) agendas capable of constructing and regulating an audience according to normative values (Macdonald Citation2007). Crucially though, it also supports the potential of attending to the relationship between the body of the spectator and the materiality of the museum.

The concept of embodiment has also been used to understand the outcomes of museum experience at the level of individual museum users. For example, analysis of the spatial and embodied experiences of museum users has highlighted (dis)comfort as a key factor of the museum experience for (dis)able-bodies (Guffey Citation2015; Leahy Citation2012). Other research, drawing on Ingold’s (Citation2015) theory of wayfaring, suggests place is produced through movements and perceptions, explaining how very-young children gain confidence and independence through movement over the course of repeated museum visits (Hackett Citation2016). Although the literature is restricted to observations of walking, looking and conversing, it points to the possibility of fruitfully employing embodiment and spatiality as lenses through which to explore museum experiences.

Liminality and family museum practices

Liminality is a concept that has been used to explore the interplay between people and the built environment in museum research (Duncan and Wallach Citation1980; Sftinteş Citation2012). Pioneering work by van Gennep (Citation1909), taken up by Turner (Citation1974), defines liminality as a description of ritual transitions in which a person is separated from social norms. Duncan argues that Turner recognised aspects of liminality in modern activities such as ‘visiting an art exhibition’ and that art museums ‘open a space in which individuals can step back from the practical concerns and social relations of everyday life and look at themselves and their world’ (Citation1995, 11). Liminality, in this sense of separation from social norms, provides two key frames of interpretation: first, as a lens through which to view family behaviour in museums, because it is by no means clear that carers can step back from the practical concerns and social relations of everyday life; and second, in relation to museum spaces, which can be liminal in respect of breaking with established norms of curation and display.

Liminality and family life

Taking the first framing of liminality in relation to the norms of family life, museums offer the potential for families to escape domestic routines, but also hold the potential for home making and reaffirming family norms. Research in tourism has highlighted the blurred boundaries between ‘home’ and ‘away’ (Light and Brown Citation2020), with the potential for tourists to reassert the familiarity of home and domestic norms in new environments (Andrews Citation2005; Obrador Citation2012). Family members may also seek freedom from family norms to pursue their own interests, taking a break from the family group (Schänzel and Smith Citation2014). Drawing upon cultural appropriation theory in anthropological research (Carù and Cova Citation2006), Isabelle, Dominique, and Statia (Citation2019) identify processes of nesting, investigating and stamping to describe how mundane routines take place within the liminoid state of the holiday, and how they are conceptually related to the achievement of family togetherness.

Nesting is the process of making oneself at home in a new situation, achieved through establishing anchorage points. Home is defined as a place of freedom, autonomy, privacy, routines (e.g., sleeping, eating and cleaning), identity construction, safety, security, friendship and hospitality (Isabelle, Dominique, and Statia Citation2019). To this, we add play, as a vital element of freedom. Facilitating nesting within the museum is vital if families are to feel at home and prolong their stay. Investigating, involves moving away from the nest and appropriating new space through routines, technology (e.g., guides, maps and apps) and behaviours that facilitate mobility (e.g., decision making). Stamping, involves assigning personal meaning to experiences. In the broadest sense, this involves drawing comparisons with previous experiences and communicating with others.

Liminality and museum space

Turning to the second framing of liminality in relation to museum spaces, a key question concerns whether museum spaces can be defined as liminoid? In the context of designing a digital interface for a hotel lobby, Mason (Citation2018, 58) asks: ‘Can we (or do we) overtly design a space that is liminal?’. Addressing this question in relation to museum norms, the dominant form of design and programming is orientated towards the contemplation of art objects, and it prioritises the occulacentric mode of engagement (Bal Citation2003; Bennett Citation2006); although we note that contemporary art often includes appears to other senses. Although liminality will be experienced differently by visitors, it is proposed that museum spaces that depart from the dominant form are more likely to be experienced as liminoid. Spaces with these liminal qualities are likely to include thresholds, which include the quotidian and under-researched spaces of entrances, atria, connective thoroughfares (e.g., stairwells) and waiting areas (e.g., lift lobbies).

Researching the function that museum thresholds hold for families is important if we are to discover how families make themselves at home in the museum. Skellen and Tunstall (Citation2018, 13) suggest:

Inclusive or progressive museum cultures seek to create a space of welcome instead of intimidation for visitors, of diversity instead of homogeneity, and atria are often playful liberatory spaces, sites of complementary activities, educational workshops, self-improvement practices, and consumer attractions.

Huizinga's (Citation1949) seminal work on the ontology of play defines play as freedom and as prior to culture. Several aspects of Huizingian play are used as an analytical framework in this paper to make sense of family play in the museum. First, ludic play is identified as ‘pleasure’, ‘passion’, ‘intensity’, ‘absorption’, ‘fun and excitement’ (Huizinga Citation1949, 2). Ludic play can be observed as simple frolicking or it can be present in complex cooperative actions (Sennett Citation2013). Ludic play sits alongside everyday life and has a spiritual quality that means it is prior to the work of reproducing family life, yet is vitally important to the ‘well-being of the group’ (Huizinga Citation1949, 9). Second, play as pun is indentified as present in language and the play on words that provides metaphors with their symbolic meanings (Huizinga Citation1949). In this sense, play relies upon routines and established rules, but equally upon the playful adaptation and transgressing of these rules. Family play in the museum, therefore, has the potential to observe and/or reject museum conventions. Third, play has the sense of illusion and the sense of things ‘not being real’ (Huizinga Citation1949, 22). Drawing from ritual cultic practices, Huizinga observes that participants are not afraid, because they know they have staged the whole ceremony. Therefore, there is a sense of play as simulation, which can be extended to family museum practices as family members may play at simulating family life in the museum environment. Finally, Huizinga (Citation1949, 10) notes that play has a ‘limitation as to space’ and therefore marking out space as a playground is an important activity. This final theoretical framing that has been applied in spatial ethnographies of play in public space (Jones Citation2013) and is later used to frame the analysis of ethnographic data in the paper.

Research approach and method

Ethnographic research was conducted at Tate Modern between 2014 and 2018. Tate has had a long-term committment to families as an under-represented audience and in its latest vision Tate (Citation2020) seeks to engage with them by focusing on ‘making, doing and participation’ (22) via, inter alia: experiencing exhibitions and displays; learning, in relation to programmes that are ‘playful, co-designed with colleagues, hands-on and artist led’ (26); and eating, in the context of catering outlets and ‘Members Rooms’ (40). That participation, playing and eating have come to be regarded as pivotal to family experiences of Tate, provided the rationale for the research which this paper now turns to report. The main contribution to museum research of this study is that it develops a deeper understanding of embodied family practices taking place in spaces where programming and display are marginal, and hence which may be considered liminal.

Context

Tate is an executive non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Sport and Media (DDCMS), receiving funds from the central UK government and generating over half its annual income through commercial and charitable functions (Tate Citation2017). Its mission is to increase public understanding and enjoyment of British art from the sixteenth century to the present day through its four museums, including Tate Modern, which are important domestic and international cultural attractions (ALVA Citation2018).

Empirical data was generated in five distinct spaces at Tate Modern: the Turbine Hall; the Natalie Bell Building Level Four concourse; the Tanks; the Architecture Room; and the Start Display. These spaces were purposively selected because they meet the norms, expectations and values of museum space to different extents; put another way, they all exhibited characteristics of liminality to varying degrees. For instance, they were subject to traditional modes of museum management (i.e., curation, conservation, display, education and visitor management) to greater or lesser extent, but they differed in relation to their function, curation and spatial syntax ().

Table 1. Description of the Tate Modern spaces.

The Turbine Hall and Level Four concourse are the most liminal, because although they host artworks, they also serve a variety of visitor management functions, such as ticket sales and transit. As transit spaces with multiple functions they qualify as choice spaces, to use Tzortzi's (Citation2017) terminology noted above. During our research, the art work in both spaces was curated to provide visitors with visual and auditory sense experiences. Occupying a medium level of liminality, the Tanks displayed video art, a durational medium reliant on visual and auditory engagement. The Tanks were more liminal than the Architecture Room and Start Display because soft furnishings (i.e., bean bags), carpets, low lighting and noise from the art installation meant that a wider range of visitor behaviours could be accommodated without disrupting the primary visitor function of viewing art.

The Tanks are less liminal than the Turbine Hall and Level Four Concourse, because as an occupation space, accessed via a control space, they do not facilitate visitor transit nor other museum functions. The Architecture Room is a conventional circulation space with no additional museum management functions, yet it exhibits medium-low liminality because the artwork is visual and tactile. The Start Display is a circulation space and has low liminality; it displays artworks on walls, prioritises visual engagement, and provides a clear ‘walk through’ for visitors. The Start Display conforms to a traditional museum display and it is included in the research because it includes interpretation that was purposefully didactic and specifically designed for family audiences and those relatively unfamiliar with visiting art museums.

Researching with families

When conducting ethnographic research in public spaces is not always apparent what affiliations group members have to each other without obtrusive interventions that introduce observer bias and disrupt ‘natural’ family practices. By adopting Tate’s broad definition of children and their domestic adults (Hood Citation2019), the research was able to address the complexities of family without disrupting naturally occurring behaviours.

Data generation

Observations of family groups at Tate Modern took place during the four-year period, with special consideration given to time of day, week and year, to account for the natural rhythms of family museum audiences. Raw data from over 100 h of observation was recorded in fieldnotes. Intercept interviews were conducted with family groups during and around the school half-term holidays in October 2016 and February 2017. The discrete time frame was intended to minimise disruption and coincide with increased audience numbers.

The sample focused on both unusual and varied cases in line with standard ethnographic practice (Pink Citation2007). Overall, 44 visitors participated in intercept interviews, which ranged in length from 90 s to 20 min. In addition to collecting basic information about participants, these interviews were designed to illicit narrative accounts of their experiences of Tate. Discussion of museum visiting practices served as an ice-breaking exercise and a socio-economic marker (Archer et al. Citation2016), approximate ages of children were recorded and roles in the family group, but no other identity data relating to ethnicity, sexuality, gender or disability, for instance, was collected. All but one intercept interview were audio recorded and transcribed. Other visual sources included: photographs taken during in-gallery observations; visitor maps and gallery signage; printed resources for families; and a range of organisational policies, evaluations and reports. These are referred to below as ‘documentary data’.

In addition, sixteen in-depth interviews with twelve practitioners at Tate were conducted during the period of the research. Practitioners were white, female and employed by Tate (in one case, on a freelance basis) in a variety of family-audience related positions. The interviews lasted between 17 and 90 min, and all but one were audio recorded and transcribed. Sampling was purposive; it was not representative but sought to generate expert data (Symon and Cassell Citation2012). Views and opinions from Tate practitioners with no specific responsibility for family audiences during in-gallery observations through conversation, were also recorded in fieldnotes.

Approach to analysis

The data from observations and intercept interviews with families was coded thematically. Subsequent analysis employed the established approach of the ethnographer as bricoleur, using methods of analysis at hand iteratively and pragmatically (Van Maanen Citation2011). Key themes of family practices (for example the maintenance of family life and family dynamics) and subcategories (for example, spatial cohesion and dissonance, mothering, family portraiture), that had been identified during early phases of the research provided an initial basis for the coding structure, but attention was also paid to the possibility of emergent themes which included playing and behaviour management outside the home (Gibbs Citation2007). Simultaneously, data was considered in terms of existing theories; this meant moving backwards and forwards between theory and data (O'Reilly Citation2009).

Findings

The Turbine Hall

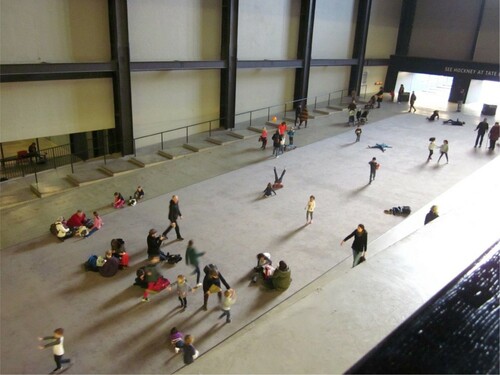

The Turbine Hall houses a newly commissioned contemporary artwork each year and also operates as an entrance, ticket hall and as a bridge between gallery spaces. An example of a choice space, the Turbine Hall provides access to other areas in the museum and is the most liminal with respect to museum conventions of display. Similar to other museum threshold spaces with a high level of liminality (Parry, Page, and Moseley Citation2018), the Turbine Hall is distinguished by its industrial size and the scale of the art works on display (see ). Observations were conducted during the installation of Anywhen (2016), a site-specific, immersive artwork by Philippe Parreno exhibited between October 2016 and April 2017. The artwork, comprising light and sound as well as objects, changed throughout each day of the commission and evolved throughout its period of installation. The changes and evolution in it were triggered by software responding to micro-organisms in the Turbine Hall, affording all those present a role in the artwork. In some senses, it may best be understood as an environment, existing, at least to some extent, through audience presence. Though it afforded aural and visual opportunities for audiences to engage, the ability to engage through presence alone emphasised a unique dimension to art museum visitation. Significantly, the Tubine Hall was partially carpeted during this installation.

During observations, an almost-constant flow of people walked through the Turbine Hall, supported by spatial planning that enables direct access from the south side of the museum complex to its river frontage (Dercon and Serota Citation2016). Family visitors took part in investigating practices through walking, looking and conversing. It was observed that families occupied the space through a variety of territorial nesting practices. Shortly after the museum opened each day, the carpeted slope of the west end of the Turbine Hall became a seating area for family groups of two or more, with group members positioning their bodies and possessions to create small, inward-facing circles. In some cases, these temporary arenas were used to corral young and very-young children, with small toys and activities being supplied by their adults. In one example, two adults arranged themselves and their child’s pushchair into a bounded area in which they could play with their young child and a toy car. Temporarily constructed spaces were often sensitive to the ages of children in groups; for example, older children would be allowed to play in a satellite fashion, away from their seated adults, so the space constructed would be partially outward facing and boundaries would be marked by material features in the wider space such as the edge of the carpet. Tate staff noted that visitors spent ‘longer than usual’ resting in the Turbine Hall during this installation, which was attributed to the addition of ‘carpets’ [Senior Leader, Learning and Research, Tate Modern, February 2017].

Stamping was also evident. A member of a family group participating in an intercept interview described how the group visit to Tate had just involved time spent in the Turbine Hall, undertaking creative activities, ‘ … it's a lovely space, I'm trying to inspire her with drawing and also with her writing, I want her to write down about what she's seen and things like that and show her art if I can, you know … ’ [Adult member of family group visitor, Turbine Hall, February 2017].

The play happening on the carpet was dynamic and represented all four types of Huizingian play. Ludic play was very much in evidence. The slope and soft surface of the carpet was used for acrobatics (e.g., cartwheels and rolls), toy car games, ball games (e.g., throwing and catching) and sliding games. As one Tate practitioner stated:

… just to be able to have your children roll down the hill in the Turbine Hall really makes a difference [to families] I think, and so, if you’ve got an environment where children can be able to behave in ways that are less constraining whether because of the nature of the building, the nature of the collection, whatever, it makes a huge difference. (Tate practitioner, in-depth interview, February 2017)

Level Four concourse

The Level Four concourse is another choice space offering access to the collection display spaces to the east and west of the original Tate Modern building. The Level Four concourse is typical of other connecting spaces at Tate Modern, which have been designed to be spacious and include seating areas (see ).

The need for good quality space between galleries was recognised as an important requirement during the conversion of the power station to form the original building and the subsequent development of the extension, known as the Blavatnik Building (Dercon and Serota Citation2016). Although principally serving the function of audience transit, at the time of the research the Level Four concourse displayed an artwork, entitled Untitled by Rudolf Stingel, a wall-mounted orange carpet that invites touch from its audiences. Level Four is at the top of the building and there were fewer people moving through this space than in the lower levels, with the exception of the Architecture Room.

Eating was frequently observed in the Level Four concourse as another form of nesting. In one observation, three young adolescent girls selected seats and ate their packed lunches whilst chatting. After they finished their lunches, an adult joined the group from a nearby chair and asked them if they were ready to go into the galleries. The girls all agreed and began to tidy away the remains of their lunches, with the adult collecting rubbish. After disposing of the rubbish, the adult instructed the girls, should they get separated from the group, to return to their current location. The group then walked into the adjoining gallery (i.e., investigating). The mundane practice of eating is an important way of carving out a more intimate space in an industrial scale museum, a nest to which the family may return.

Playing was less visible in the concourse. Pairs or groups of children, aged eight years and upwards, were observed unaccompanied by adults and playing in silence on their mobile phones. In the majority of cases, adults returned from visiting other parts of the museum to rejoin their children. Family members were observed waiting and resting. Individuals were observed sleeping in the chairs in some of the spaces off the main passageway, but they did not appear to be connected to family groups.

One participant described the Level Four concourse as a space where ‘the kids can be themselves’ [Adult member of family group visitors, Tate Modern, July 2016]. We interpret this to mean that adults regard children to be most authentically themselves in the home environment, and that the choice spaces at Tate Modern provide the opportunity to make a home away from home. The Level Four concourse, similar to the Turbine Hall, has a high level of liminality with regard to museum conventions of display, but in regard to the home, it has a low level of liminality, because family members are able to enact norms of home.

The Tanks

Like the Turbine Hall, the Tanks at Tate Modern retain the aesthetic and scale of their original industrial use. The space is organised with a control space, that provides access to three occupation spaces. The data presented here was generated in the time immediately after the Tanks permanently opened in June 2016, during the exhibit of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s multi-screen video artwork Primitive. The artwork which comprised seven videos varying in duration from one minute to 29 min, was installed on cinema-sized screens; during the display, a large, circular red carpet and cushions were installed in the Tanks. The primary function of the space was the display of art works, with the carpet and cushions intended to provide a more comfortable environment in which to view the video installation. To some extent, the carpet and cushions represent a departure from museum norms that are premised on viewers standing to view works and therefore acted to suggest a more liminal space.

During one observation session, a group of three adults and five children, all made themselves at home by removing coats. Aged between three and eleven years, the children were sitting and lying on the carpeted floor. Initially, there was little-to-no conversation amongst the group members, with two members using phones silently. After a period of quiet, three of the older children began to play-fight, and activity condoned by all the adults whilst the youngest child arranged some cushions into a bed. As the child settled to sleep, he was given a teddy bear by one of the adults. Another adult announced to the group that she was going to look around the museum, at which point the four awake children started to engage with the video, arranging cushions in a line to allow them to watch one of the screens. The children then returned to play fighting and lounging. The remaining adults began to chat and after approximately 40 min, the absent adult returned, and the group prepared to leave the space. The sleeping child on waking was notified of the intention to move whilst being helped to put on his shoes. The group agreed to visit the café before they left the museum. This episode was reminiscent of time spent by a family in a living room, demonstrating the potential of the liminal museum spaces to be constructed both for and by audiences in such a way that they resonate with, or even replicate, the intimacy of private space. The Tanks provided the strongest examples of family nesting. In contrast to the Turbine Hall where children investigated the museum from the safety of a family nest, in the Tanks it was adults that were observed investigating the museum from family nests.

Architecture Room

Meschac Gaba’s Architecture Room is a circulation space and contains one part of the artist’s larger works The Museum of Contemporary African Art (1997–2002). The artwork, developed over time and in different settings, comprises twelve installations each representing Gaba’s understanding of the core functions of a museum. Architecture Room is located in a traditional gallery space at Tate Modern that is subject to museum practices relating to curation, conservation and display. However, part of the installation includes an expansive blue carpet with wooden building bricks that invite the audience to participate through designing a proposal for a fixed Museum of Contemporary African Art (see ). Therefore, the liminality of the space could be considered to be low, but is lifted to medium-low status because of the disruptive presence of the tactile art object and carpet space.

Approximately a quarter of family groups entering Architecture Room included at least one group member who participated in the artwork through sitting on the carpet and using the bricks. No lone individuals were observed sitting on the carpet and using the bricks, and visitors were more likely to sit on the carpet and use the bricks if the carpet was empty of other visitors. In one specific episode, two children entered the room with their adults and immediately began playing with the bricks; one adult joined the boys on the carpet whilst the other documented the activity through photography. The two boys started to argue and were asked by their adults to be quiet, a request ignored by both boys and prefacing the older boy knocking down the younger boy’s building. The adult playing with the bricks physically removed the older boy from the carpet and directed him towards looking at another part of the artwork. The second adult joined the younger boy on the carpet and efforts were made by the adults to reconcile the boys. Away from the carpet, the older boy described the artwork to the adults and attempted to understand its meaning through discussion. More photos were taken and both boys resumed playing with the bricks, following a reconciliation brokered by their adults. Their play was closely overseen and, after a further ten minutes, was stopped by the adults who directed the children out of the gallery spaces. A feature of the Architecture Room is the invitation made to visitors to propose their own architectural structures within the circumscribed space of the blue carpet. A regular feature during the installation of this display involved family visitors collaborating with each other to create structures that drew on their own personal experiences of architectural spaces. Adults were observed prompting each other and children, at times sitting alongside them on the carpet, at other times moving away to look at the other objects in the installation, returning at times to encourage the children or to create structures for themselves. Such stamping activities accompanied the associated nesting and investigating behaviours that were observed through play and the exercise of family disciplinary practices.

The Start Display

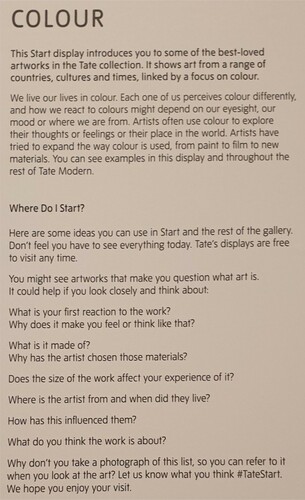

The Start Display is a circulation space and comprises two rooms and shows some of the most well-known artworks in Tate Modern’s collection (see ). It was designed to be walked through and to increase the confidence of visitors to the museum by providing a tool kit for approaching other artworks. Unlike the other spaces included in this study, the Start Display does not include any soft seating or a carpeted area.

The invitation to families and other visitors to engage more actively with the art on display is made through the written texts on the walls. Specifically, these interpretation texts are framed as questions designed to encourage visitors to look carefully and to draw on their own knowledge and experience to understand and make meaning from the works (see ).

Figure 5. The Start Display visitor guide curated by Ann Coxon and Valentina Ravaglia with Kirsteen McSwein and Gilian Wilson, Tate Learning, December 2021.

The Start Gallery was described by one Tate practitioner as being:

really about enabling families to come in and pick up a set of skills or competencies about looking at art. They are kind of like top tips for looking at art, er, in a way that hopefully isn’t either patronising or impenetrable, so the tone has to be, ‘if you’re looking at art, these kind of things might help.’ (Tate practitioner during in-depth interview, February 2017)

As an introductory, confidence-building space, the Start Gallery seeks to promote nesting. Furthermore, the interpretation texts in the display are designed to support investigation through the provision of conceptual tools that can be applied when looking at art elsewhere in the museum. Equally, the rationale underpinning the Start Gallery is that everyone can make their own personal meanings from art; that is by stamping. During observations, the space was often busy and characterised by an irregular visitor flow, with groups frequently stopping and starting and splitting before reforming. In one instance of nesting and stamping, an adult and child sat on a bench and used art materials bought in the gift shop to recreate one of the artworks on display. In another episode of investigating, a group comprising one adult and two girls, read the display panels and art labels together. The adult subsequently asked the children questions about the artwork and directed their looking according to the advice given in the display. One of the girls moved away from the group to look at a different part of the display but her attention remained with the core group and her trajectory reflected their movements. These behaviours were characteristic of the family interactions observed in this space. The Start Display actively invites conversation between individuals and adults and children were regularly observed reading the questions to each and inviting personal responses. The contained space of the display also affords opportunities for groups to come together to look at particular works and then separate to view other works individually, without adults losing contact with children.

Cross case analysis and discussion

Mundane family museum practices

A variety of routine and mundane activities were observed as important family practices. Nesting was the most frequently observed practice as families were sitting, talking, eating, drinking and resting. These activities are key audience practices in the spaces of the Turbine Hall, the Level Four concourse and the Tanks, suggesting that more liminal spaces facilitate these activities for family members. Further, the research identified resting as an important family practice. Tate Modern, similar to many industrial scale museums, is an expansive site and moving around this space inevitably drains the energy of family visitors. Sitting, lying down and sleeping were observed in the Tanks and was also observed of young children in pushchairs in various locations. As children rested, adults were able to engage with the museum by investigating the space to a greater extent, whether this involved leaving children in nests under supervision, or conveying children in pushchairs through the spaces. Mundane practices were observed most frequently in the Turbine Hall and the Level Four concourse, illustrating how the more liminal spaces of the museum can be constructed as semi-private spaces able to meet intra-familial needs (Astor-Jack et al. Citation2007; Dawson and Jensen Citation2011). Nesting and investigating were connected activities in the more liminal spaces at Tate Modern. Stamping, as means of making sense of the museum, was observed regardless of the spatial design, but was more evident in the Start Display where art works were curated to facilitate access to the Tate Modern collections and generate conversations between visitors. The research confirmed that conversing is a typical feature of audience practice (Kopczak, Kisiel, and Rowe Citation2015) and occurs with other aspects of spectatorship including sitting, walking, looking and learning (Leahy Citation2012; Kopczak, Kisiel, and Rowe Citation2015).

Playing and liminal museum space

Play was observed to be an important family practice. Ludic play was frequently observed in the Turbine Hall, which was encouraged by the presence of children, but was evidently enjoyed across generations. Spontaneity and light-heartedness were enduring features of family practices in the Turbine Hall. Ludic play also was evident in the Tanks, where children choose to playfight or play games on their mobile devices, as well as in Architecture Room, where play was facilitated by participatory artwork. In all three spaces, carpet was the setting for play. The physical properties of the carpets afforded a comfortable environment, but functioned as an invitation to, as well as a material space for, play. In Architecture Room, being removed from the carpet signified the prevention of play. In the expanse of the Turbine Hall, if play went beyond the boundary of the carpet, it was typically regarded as less acceptable by staff and many parents.

Whilst children’s ludic play in all three carpeted spaces was initially encouraged, even facilitated by adults, further parental management of play varied across the spaces. In Architecture Room, play was closely managed by parents to limit noise disruption and to ensure harmony; play-fighting children in the Tanks were left by their adults to self-regulate; and children in the Turbine Hall were, in several cases, supported by adults to transgress staff guidance through play. These differences could be attributed to variations in parental attitudes and behaviour management strategies, yet the environment and curation contributed to how adults decided to manage their children’s ludic play. In the Tanks, there was a reduced need for children’s play to be limited by adults, because play was obscured by the low light and the sound of the artwork. The design of the building, combined with the artwork, meant that visitor play did not disrupt the participation of other visitors, relieving families of the burden of conforming to social norms upheld in other Tate spaces. In Architecture Room, play was intentionally curated to intensify visitor participation. When play is curated we observed that parents regulated childrens’ play according to perceived social norms. Typically, when the sound of the children playing (and squabbling) obscured previous quiet, parents acted to regulate play and discipline children. In sum, ludic play was afforded through the provision of a comfortable non-quiet place in which to sit and stay, but this was moderated when play was designed to facilitate visitor engagement with art works. The more liminal museum spaces were found to offer visitors with opportunities to resist (and even subvert) traditional museum visitor practices to meet their own social needs. This finding has evident implications for museums seeking to widen access to family visitors.

Second, play as pun was also evident as families made themselves at home. In the Tanks, the family practices observed were reminiscent of time spent by a family group in their living room. By using museum spaces according to their own needs, rather than according to conventions associated with more typical modes of museum visiting, the meaning of the museum visit appeared to shift from education and public recreation to that of private leisure.

Third, play as simulation, or ‘playing at’ relates to the museum as a performative space (Duncan Citation1995). Eating on the Level Four concourse demonstrated a version of simulation by affording adolescents an opportunity to ‘play at’ the independence associated with adulthood. Visiting a museum and the ludic playing observed, especially in the Turbine Hall, revealed an audience ‘playing at’ a particular version of family life or leisure pursuit which can be broadcast to acquaintances and beyond via the internet as a mechanism of social distinction (Choi Citation2016). Put another way, visiting a museum is a complex articulation of intersecting identities as groups ‘play at’ being families while individuals ‘play out’ their particular roles as family members. Both intra- and extra-group relationships emerge as vital in establishing a family identity and the ability of family audiences to use Tate to achieve the privacies associated with family as well as public expectations. This would appear to reflect the disputed position between public and private that the family has sometimes occupied (Laslett Citation1973; Fahey Citation1995)

Finally, marking out space as a playground, was facilitated by carpeted areas in the museum and was enacted by families through territorial nesting practices. These were most notable in the most liminal space of the Turbine Hall as temporary nests were constructed by families with the equipment they had to hand. Territorial practices were facilitated by the presence of benches in the least liminal space of the Start Display, but play was not a family behaviour observed in this space. More playful family behaviour was observed as the spatial design of museum departed from occularcentric curatorial norms.

Intra-group family practices

Multiple intra-group needs were met to a greater extent in the more liminal spaces. In the Tanks the group were able to sit, play, converse and sleep according to their own wishes. One group member left the space and the group for a significant period of time, presumably safe in the knowledge that the group would easily be reunited. In contrast, in the least liminal case, the Start Display, group members took steps to experience the space independently, but were still required to pay attention to the movements of other audience members. For Leahy (Citation2012), museum walking is understood as a public, social practice. The walking museum audience is often required to move at the same pace and in the same direction; audience members might need to overtake or make space for others, or they might block the view of an artwork or display for others. Conversely, as this research demonstrates, the sitting museum audience produces a social space orientated towards intra-group needs. The received wisdom is that family group museum visitation can make family responsibilities more acute (Garner Citation2015), but the research found that that liminal museum spaces can provide respite from particular familial roles.

Conclusion

The conclusions are framed by the two research questions informing the study. These questions are important as museum managers are faced with the challenge of attracting family audiences in a crowded marketplace for leisure. Typical recommendations suggest the importance of family-friendly galleries, programmes, events, entertainment and social media (Mendoza Citation2017). This research, in contrast, suggests that museums should also concern themselves with the mundane needs of family visitors as a means of enhancing the accessibility of their public spaces.

How do families utilise different types of museum spaces?

Through a spatial ethnographic lens, the research established that practices in more or less liminal museums spaces (including playing, sitting, talking, eating, drinking, resting and sleeping), taken together, present a compelling opposition to the mannered and sometimes uncomfortable or alienating practices of the typical museum visit (Duncan Citation1995; Leahy Citation2012; Guffey Citation2015). Focusing on mundane family practices adds to our understanding of the complex role of the museum as public space. Such family practices typically combine to produce flexibly-bounded generative spaces within the museum orientated by the needs of the museum audience. They represent multiple spaces of privacy within the public space of the museum (Fahey Citation1995), and they fulfil several functions including, not least, the maintenance of social relationships and the development of social skills. Though the spaces might be partially supported by collection displays, crucially, these and other museum management agendas, are not necessarily at their centre. At the same time, this research reveals the potential museum displays and spaces do have for nurturing playfulness and positive family engagement. As such, the research raises the issue of how these alternative audience practices should be further supported and how they should be reconciled with existing versions of spectatorship and museum management practices. Tate Modern possesses several liminal spaces that exemplify how alternative audience provision is valued by families and contributes to family members investigating spaces curated in more conventional ways. In creating these spaces, the museum is inviting families to inhabit the museum in ways that divulge from what is traditionally seen as acceptable visitor behaviour. Yet it is not apparent that the museum sector is fully aware of the specific benefits accruing from this less formal family provision that, importantly, gives greater agency to the visitor. Further research that interrogates the value families give to liminal space practices is therefore needed.

What are the implications of the associated spatial practices of family museum visits for museum management?

The research demonstrates that more liminal spaces support and stretch the idea that museums should create ‘spaces for the audience’ (Black Citation2018, 308). Through its more liminal spaces, Tate Modern is offers an important way of impacting society through the provision of public space that is responsive to family group agency. Of course, more liminal spaces in museums also provide respite from time spent in front of displays. Notwithstanding, this research suggests that liminal spaces are undervalued in this respect. Alternative audience practices such as play, whilst important in their own right to groups, also provide families with support to engage with other spaces subject to more typical museum management practices. Crucially, as the coronavirus pandemic has reduced public funding for museums and managers seek to restructure around agendas for social transformation (Harris Citation2021), the research raises awareness that museum inclusion and diversification policies must pay more attention to the affordances of liminal spaces for groups otherwise under-represented in museum policy and practice.

Disclosure statement

One of the co-authors of the paper, Dr Emily Pringle, is an employee of Tate.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louisa Hood

Louisa Hood is an Associate Researcher at the University of Exeter. Between 2014 and 2018 Louisa was a collaborative doctoral student at the University of Exeter and Tate where she researched the socio-spatial museum and was particularly focused on family visitor experiences. Since obtaining her doctorate she has worked as an Assistant Curator for the National Trust and as city walls manager for City of York Council, where her research and practice remains focused on how spaces designated as cultural relate to people's everyday lives.

Adrian R. Bailey

Adrian R. Bailey is Senior Lecturer in Management at the University of Exeter Business School. His previous research has spanned a wide variety of themes including museum evaluation, geographies of religion, retailing and sustainable supply chain management. His current research focuses on issues of collaboration and governance in co-operatives and social enterprises.

Tim Coles

Tim Coles is Professor of Management at the University of Exeter Business School. His previous research has examined a wide range of issues relating to the sustainable development of tourism and leisure, including the social impacts of museums and other cultural institutions. His current research is focused on issues of participation among different social groups in the tourism sector on both the demand- and supply-sides.

Emily Pringle

Emily Pringle is the Head of Research at Tate. Her previous research explores how art can make a difference to people's lives and society, with a focus on practice-led research and learning. Her recent work is presented in ‘Rethinking Research in the Art Museum’, published in 2019.

References

- ALVA. 2018. “Association of Leading Visitor Attractions: Latest Visitor Figures.” http://www.alva.org.uk/details.cfm?p=423.

- Andrews, H. 2005. “Feeling at Home: Embodying Britishness in a Spanish Charter Tourist Resort.” Tourist Studies 5 (3): 247–266. doi:10.1177/1468797605070336.

- Archer, L., E. Dawson, A. Seakins, and B. Wong. 2016. “Disorientating, Fun or Meaningful? Disadvantaged Families’ Experiences of a Science Museum Visit.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 11 (4): 917–939. doi:10.1007/s11422-015-9667-7.

- Ash, D. 2003. “Dialogic Inquiry of Family Groups in a Science Museum.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 40 (2): 138–162. doi:10.1002/tea.10069.

- Ash, D. 2004. “How Families Use Questions at Dioramas: Ideas for Exhibit Design.” Curator: The Museum Journal 47 (1): 84–100. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2004.tb00367.x.

- Astor-Jack, T., K. L. K. Whaley, L. D. Dierking, D. L. Perry, and C. Garibay. 2007. “Investigating Socially Mediated Learning.” In In Principle, in Practice: Museums as Learning Institutions, edited by J. H. Falk, L. D. Dierking, and S. Foutz, 217–228. New York: AltaMira Press.

- Bal, M. 2003. “Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 2 (1): 5–32. doi:10.1177/147041290300200101.

- Bennett, T. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge.

- Bennett, T. 2006. “Civic Seeing: Museums and the Organisation of Vision.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by S. MacDonald, 263–281. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Black, G. 2005. The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. London: Routledge.

- Black, G. 2012. Transforming Museums in the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge.

- Black, G. 2016. “Remember the 70%: Sustaining ‘Core’ Museum Audiences.” Museum Management and Curatorship 31 (4): 386–401. doi:10.1080/09647775.2016.1165625.

- Black, G. 2018. “Meeting the Audience Challenge in the ‘Age of Participation.’” Museum Management and Curatorship 33 (4): 302–319. doi:10.1080/09647775.2018.1469097.

- Bourdieu, P., A. Darbel, and D. Schnapper. 1991. The Love of Art: European Art Museums and Their Public. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Callanan, M. A., C. L. Castañeda, M. R. Luce, and J. L. Martin. 2017. “Family Science Talk in Museums: Predicting Children's Engagement from Variations in Talk and Activity.” Child Development 88 (5): 1492–1504. doi:10.1111/cdev.12886.

- Carù, A., and B. Cova. 2006. “How to Facilitate Immersion in a Consumption Experience: Appropriation Operations and Service Elements.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review 5 (1): 4–14. doi.org/10.1002/cb.30.

- Choi, K. 2016. “Habitus, Affordances, and Family Leisure: Cultural Reproduction Through Children’s Leisure Activities.” Ethnography 18 (4): 427–449. doi:10.1177/1466138116674734.

- Christidou, D., and P. Pierroux. 2019. “Art, Touch and Meaning Making: An Analysis of Multisensory Interpretation in the Museum.” Museum Management and Curatorship 34 (1): 96–115. doi:10.1080/09647775.2018.1516561.

- Cicero, L., and T. Teichert. 2018. “Children's Influence in Museum Visits: Antecedents and Consequences.” Museum Management and Curatorship 33 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1080/09647775.2017.1420485.

- Classen, C. 2017. The Museum of the Sense: Experiencing Art and Collections. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Colomina, B. 1994. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Communications Design Team, Royal Ontario Museum. 1999. “Spatial Considerations.” In The Educational Role of the Museum. 2nd ed., edited by E. Hooper-Greenhill, 178–190. London: Routledge.

- Dawson, E., and E. Jensen. 2011. “Towards A Contextual Turn in Visitor Studies: Evaluating Visitor Segmentation and Identity-Related Motivations.” Visitor Studies 14 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1080/10645578.2011.608001.

- Dercon, C., and N. Serota. 2016. Tate Modern: Building a Museum for the 21st Century. London: Tate Publishing.

- Duncan, C. 1995. Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge.

- Duncan, C., and A. Wallach. 1980. “The Universal Survey Museum.” Ariel 137: 212–199.

- Eardley, A. F., C. Dobbin, J. Neves, and P. Ride. 2018. “Hands-On, Shoes-Off: Multisensory Tools Enhance Family Engagement Within an Art Museum.” Visitor Studies 21 (1): 79–97. doi:10.1080/10645578.2018.1503873.

- Fahey, T. 1995. “Privacy and the Family: Conceptual and Empirical Reflections.” Sociology 29 (2): 687–702. doi:10.1177/0038038595029004008.

- Falk, J. H. 2008. “Viewing Art Museum Visitors Through the Lens of Identity.” Visual Arts Research 34 (2): 25–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20715472

- Garner, B. 2015. “Mundane Mommies and Doting Daddies: Gendered Parenting and Family Museum Visits.” Qualitative Sociology 38 (3): 327–348. doi:10.1007/s11133-015-9310-7.

- Gibbs, G. 2007. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Sage.

- Guffey, E. 2015. “The Disabling Art Museum.” Journal of Visual Culture 14 (1): 61–73. doi:10.1177/1470412914565965.

- Hackett, A. 2016. “Young Children as Wayfarers: Learning About Place by Moving Through It.” Children & Society 30 (3): 169–179. doi:10.1111/chso.12130.

- Harris, G. 2021. “The Cost of the Cuts: What now for the UK Museums as the Covid-19 Crisis Bites?” The Art Newspaper, 21 March. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/03/31/the-cost-of-the-cuts-what-now-for-uk-museums-as-the-covid-19-crisis-bites.

- Heath, C., and D. vom Lehn. 2004. “Configuring Reception: (dis-)Regarding the Spectator in Museums and Galleries.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (6): 43–65. doi:10.1177/0263276404047415.

- Hetherington, K. 2015. “Foucault and the Museum.” In The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by S. Macdonald and H. R. Leahy, 21–40. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hillier, B., and K. Tzortzi. 2006. “Space Syntax: The Language of Museum Space.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by S. MacDonald, 282–301. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hood, L. 2019. “The Family Display: A Spatial Analysis of Family Practices at Tate.” Unpublished PhD diss., University of Exeter.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. 2007. Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance. London: Routledge.

- Huizinga, J. 1949. Homo Ludens Ils 86. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2015. The Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

- Isabelle, F., K. Dominique, and E. Statia. 2019. “Home Away from Home: A Longitudinal Study of the Holiday Appropriation Process.” Tourism Management 71: 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.025.

- Jones, A. 2013. “A Tripartite Conceptualisation of Urban Public Space as a Site for Play: Evidence from South Bank, London.” Urban Geography 34 (8): 1144–1170. doi:10.1080/02723638.2013.784081.

- Jung, Y. J., H. T. Zimmerman, and P.-E. Koraly. 2018. “A Methodological Case Study with Mobile Eye-Tracking of Child Interaction in a Science Museum.” TechTrends 62 (5): 509–517. doi:10.1007/s11528-018-0310-9.

- Kai-Kee, E., L. Latina, and L. Sadoyan. 2020. Activity-Based Teaching in the Art Museum: Movement, Embodiment, Emotion. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Kirchberg, V., and M. Tröndle. 2015. “The Museum Experience: Mapping the Experience of Fine Art.” Curator: The Museum Journal 58 (2): 169–193. doi:10.1111/cura.12106.

- Kopczak, C., J. Kisiel, and S. Rowe. 2015. “Families Talking About Ecology at Touch Tanks.” Environmental Education Research 21 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.860429.

- Kristiansen, E., and A. Moseley. 2018. “Games in the Lobby: A Playful Approach.” In Museum Thresholds: The Design and Media of Arrival, edited by R. Parry, R. Page, and A. Moseley, 175–188. London: Routledge.

- Laslett, B. 1973. “The Family as a Public and Private Institution: An Historical Perspective.” Journal of Marriage and Family 35 (3): 480–492. doi:10.2307/350583.

- Leahy, H. R. 2012. Museum Bodies: The Politics and Practices of Visiting and Viewing. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Light, D., and L. Brown. 2020. “Dwelling-Mobility: A Theory of the Existential Pull Between Home and Away.” Annals of Tourism Research 81: 102880. doi.10.1016/j.annals.2020.102880

- Lindqvist, K. 2012. “Museum Finances: Challenges Beyond Economic Crises.” Museum Management and Curatorship 27 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/09647775.2012.644693.

- Lord, B., G. D. Lord, and L. Martin. 2012. Manual of Museum Planning: Sustainable Space, Facilities, and Operations. New York: Rowman Altamira.

- Macdonald, S. 2007. “Interconnecting: Museum Visiting and Exhibition Design.” CoDesign:International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 3 (sup1): 149–162. doi:10.1080/15710880701311502.

- Mason, M. 2018. “Design-Driven Innovation for Museum Entrances.” In Museum Thresholds: The Design and Media of Arrival, edited by R. Parry, R. Page, and A. Moseley, 58–77. London: Routledge.

- Mendoza, N. 2017. The Mendoza Review: An Independent Review of Museums in England. London: Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport.

- Moussouri, T., and J. Hohenstein. 2017. Museum Learning: Theory and Research as Tools for Enhancing Practice. London: Routledge.

- O'Reilly, K. 2009. Key Concepts in Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Obrador, P. 2012. “The Place of the Family in Tourism Research: Domesticity and Thick Sociality by the Pool.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (1): 401–420. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.006.

- O’Reilly, C., and A. Lawrenson. 2021. “Democratising Audience Experience: Making Space for Families in Blockbuster Exhibitions.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36 (2): 136–153. doi:10.1080/09647775.2020.1766995.

- Osman, H., N. Johns, and P. Lugosi. 2014. “Commercial Hospitality in Destination Expereinces: McDonald’s and Tourists’ Consumption of Space.” Tourism Management 42: 238–247. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.009.

- Parry, R., R. Page, and A. Moseley. 2018. Museum Thresholds: The Design and Media of Arrival. London: Routledge.

- Patel, M., C. Heath, P. Luff, D. vom Lehn, and J. Cleverly. 2016. “Playing with Words: Creativity and Interaction in Museums and Galleries.” Museum Management and Curatorship 31 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1080/09647775.2015.1102641.

- Pink, S. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research, Second Edition. London: Sage.

- Povis, K. T., and K. Crowley. 2015. “Family Learning in Object-Based Museums: The Role of Joint Attention.” Visitor Studies 18 (2): 168–182. doi:10.1080/10645578.2015.1079095.

- Prior, N. 2003. “Having One’s Tate and Eating It: Transformations of the Museum in a Hypermodern Era.” In Art and Its Publics: Museum Studies at the Millennium, edited by A. McClellan, 51–74. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Schänzel, H. A., and K. A. Smith. 2014. “The Socialization of Families Away from Home: Group Dynamics and Family Functioning on Holiday.” Leisure Sciences 36 (2): 126–143. doi:10.1080/01490400.2013.857624.

- Schorch, P. 2013. “The Experience of a Museum Space.” Museum Management and Curatorship 28 (2): 193–208. doi:10.1080/09647775.2013.776797.

- Scott, C. A. 2009. “Exploring the Evidence Base for Museum Value.” Museum Management and Curatorship 24 (3): 195–212. doi:10.1080/09647770903072823.

- Sennett, R. 2013. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. London: Penguin Books.

- Sftinteş, A. 2012. Rethinking Liminality: Built Form as Threshold-Space. Bucharest: Universitatea de Architectura si Urbanism Ion Mincu Bucuresti.

- Skellen, H., and B. Tunstall. 2018. “Hysterica Atria.” In Museum Thresholds: The Design and Media of Arrival, edited by R. Parry, R. Page, and A. Moseley, 13–23. London: Routledge.

- Sterry, P. 2011. “Designing Effective Interpretation for Contemporary Family Visitors to Art Museums and Galleries.” In Museum Gallery Interpretation and Material Culture, edited by J. Fritsch, 179–190. London: Routledge.

- Sterry, P., and E. Beaumont. 2006. “Methods for Studying Family Visitors in Art Museums: A Cross-Disciplinary Review of Current Research.” Museum Management and Curatorship 21 (3): 222–239. doi:10.1080/09647770600402103.

- Symon, G., and C. Cassell. 2012. Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges. London: Sage.

- Tate. 2017. Tate Report 2016/17. London: Tate.

- Tate. 2020. Tate Vision 2020-25. London: Tate.

- Tröndle, M., S. Wintzerith, R. Wäspe, and W. Tschacher. 2012. “A Museum for the Twenty-First Century: The Influence of ‘Sociality’ on Art Reception in Museum Space.” Museum Management and Curatorship 27 (5): 461–486. doi:10.1080/09647775.2012.737615.

- Turner, V. 1974. “Liminal to Liminoid in Play, Flow and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology.” Rice Univeristy Studies 60 (3): 53–92.

- Tzortzi, K. 2017. “Museum Architectures for Embodied Experience.” Museum Management and Curatorship 32 (5): 491–508. doi:10.1080/09647775.2017.1367258.

- van Gennep, A. 1909. The Rites of Passage, Second Edition. Translated by M. Vizedom and G. Caffee. London: Routledge.

- Van Maanen, J. 2011. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography, Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Vandermaas-Peeler, M., K. Massey, and A. Kendall. 2016. “Parent Guidance of Young Children’s Scientific and Mathematical Reasoning in a Science Museum.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (3): 217–224. doi:10.1007/s10643-015-0714-5.

- Wineman, J. D., and J. Peponis. 2010. “Constructing Spatial Meaning: Spatial Affordances in Museum Design.” Environment and Behavior 42 (1): 86–109. doi:10.1177/0013916509335534.

- Yoshimura, Y., S. Sobolevsky, C. Ratti, F. Girardin, J. P. Carrascal, J. Blat, and R. Sinatra. 2014. “An Analysis of Visitors' Behavior in the Louvre Museum: A Study Using Bluetooth Data.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 41 (6): 1113–1131. doi:10.1068/b130047p

- Zimmerman, H. T., S. Reeve, and P. Bell. 2010. “Family Sense-Making Practices in Science Center Conversations.” Science Education 94 (3): 478–505. doi:10.1002/sce.20374.