?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Museums must assess visitors’ experience to understand them and their needs. TripAdvisor provides an accessible source of user-generated data about the visit experience, but there is limited empirical evidence on the value of automated elaboration of this data for museum management. This paper uses topic modeling to identify the latent dimensions of the visit experience for the 30 most-visited Italian museums in 2019 using online reviews. Differences in the latent dimensions are assessed between visitors with different cultural backgrounds, as identified by whether they write in the local or non-local language. The results show that while all visitors share three cross-cultural dimensions of experience (museum cultural heritage, personal experience, and museum services), specific latent dimensions are emphasized by local (i.e., ‘wow effect’ and hospitality) and non-local visitors (i.e., time management and unfavorable experiences).

Introduction

Museums must provide visitors with multifaceted experiences to increase the attractiveness of cultural heritage sites (Li et al. Citation2021; Kydros and Vrana Citation2021; Ayala, Cuenca-Amigo, and Cuenca Citation2020). While assessing the visit experience is a priority for museum managers, this process is not straightforward, as shown by disagreement over the dimensions of the museum visit experience (Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Komarac, Ozretic-Dosen, and Skare Citation2020; Ponsignon and Derbaix Citation2020).

Without a common definition of these dimensions, each museum must design specific customer satisfaction surveys (Oren, Shani, and Poria Citation2021; Tranta, Alexandri, and Kyprianos Citation2021; Korani and Mirdavoudi Citation2021). Tailoring these survey questions requires considerable effort and reduces the possibility of grasping latent perceptions of experiences, since survey questions are defined according to museum experts’ expectations. Online user-generated data, such as TripAdvisor reviews, are a valuable resource for assessing the latent dimensions of experience, since they consist of the visitors’ own words rather than the predefined expectations of museum experts.

This article provides a statistical analysis of the latent dimensions of the museum experience using the visitors’ own words from their TripAdvisor reviews. We explore differences in the latent dimensions perceived by local and non-local visitors, as identified by the language of their reviews, because visitors’ cultural backgrounds are a key factor in museum experiences (Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Jia Citation2020; Tsiropoulou, Thanou, and Papavassiliou Citation2017). Because the extant literature has not assessed the role of language as proxy for cultural background empirically (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017; Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Imamoǧlu and Yilmazsoy Citation2009), this paper addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the latent dimensions of the museum visitor experience perceived by visitors who write reviews in the local language?

RQ2: What are the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience perceived by visitors who write reviews in non-local languages?

RQ3: What are (if any) the differences in latent dimensions of museum visitor experience perceived by visitors who write reviews in the local language compared to those who write in non-local languages?

The study explores 36,460 TripAdvisor reviews of the 30 most-visited Italian state museums in 2019, using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) (Blei Citation2012) to analyze differences between local and non-local reviewers. The results show differences in the latent dimensions of museum visit experience based on the language of the reviewers. While some dimensions are shared across visitors (i.e., museum cultural heritage, personal experience, and museum services), others are specific to locals (i.e., ‘wow effect’ and hospitality) and non-locals (i.e., time management and unfavorable experiences).

This article enriches the current debate on the assessment of visit experience in museums at two levels. First, this paper shows how online user-generated data (i.e., TripAdvisor reviews) can be used in the assessment of visit experience, which is typically measured using visitor satisfaction surveys (Oren, Shani, and Poria Citation2021; Richards, King, and Yeung Citation2020; Prayag and Del Chiappa Citation2016) or visitors’ movements (Tsiropoulou, Thanou, and Papavassiliou Citation2017; Limsui Citation2021; Hashemi and Kamps Citation2018). We provide a methodology for using visitors’ textual descriptions to identify the dimensions of their experiences; we apply this method to a large sample of online user reviews of Italian state museums; and we discuss the costs of implementing this approach. Second, the results demonstrate how language can serve as proxy for cultural background (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017) which shapes perceptions of the museum experience. This contributes to the debate on museum visit experience and linguistic inclusion (Lyons et al. 2020; Lipovsky Citation2020; Jiang Citation2018) and may improve the conceptualization of visitors’ inclusion within the dimensions of museum visit experience.

The rest of the paper is organized into four sections. The first section details the academic debates to which this paper contributes. The second section describes the methodology used to analyze online reviews of museum visitors. The third section presents the results and the final section discusses the implications of the results for scholars and practitioners.

Literature

Online reviews to assess museum visitor experience

Assessing visitors’ experiences helps museum managers and curators to design and redesign exhibits (Villaespesa Citation2019; MacLeod, Dodd, and Duncan Citation2015) and to improve the overall attractiveness of the museum (Thurner Citation2017; Li et al. Citation2021; Ayala, Cuenca-Amigo, and Cuenca Citation2020). In the last 30 years, research has focused on identifying the dimensions of the museum visit experience (Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Martín-Ruiz, Castellanos-Verdugo, and de los Ángeles Oviedo-García Citation2010; Foster et al. Citation2020) and the variables that influence it (Kawashima Citation2007; Stylianou-Lambert Citation2009; Tsiropoulou, Thanou, and Papavassiliou Citation2016).

Traditionally, museum visit experience has been assessed using direct surveys of visitors on a predefined set of dimensions (Brida, Meleddu, and Pulina Citation2016; Kosmopoulos and Styliaras Citation2018; Moreno-Mendoza et al. Citation2021; Nowacki and Kruczek Citation2021). This literature finds heterogeneity among different visitor groups, like young visitors (Batat Citation2020; Kim and Chung Citation2020; Manna and Palumbo Citation2018), students (Mesmoudi, Hommet, and Peschanski Citation2020), and those with special needs (Giaconi et al. Citation2021).

Though survey-based studies contribute the discussion of the heterogeneity in the visitor experience, they have two main limitations. First, the dimensions of the experience are defined a priori by museum experts rather than visitors, which risks missing some latent dimensions of experience perceived by visitors. Second, the visitors’ satisfaction is usually measured through numerical scales, which do not capture visitors’ thoughts completely.

An alternative methodological approach involves studying the movements of visitors within a museum, which allows the identification of different visitor profiles. Since the seminal paper of Eliseo and Martine (Citation1991), the four basic visiting styles of ant, butterfly, fish and grasshopper have been analyzed quantitatively (Zancanaro et al. Citation2007). Extant literature studies onsite visiting styles, such as the paths museum visitors take (Tsiropoulou, Thanou, and Papavassiliou Citation2017; Limsui Citation2021; Juniarta et al. Citation2018), visitor flows (Centorrino et al. Citation2021), time and walking speed (Castro, Botella, and Asensio Citation2016), as well as online behavior such as website clicks (Kelpšiene Citation2019; Villaespesa Citation2019; Meneses, Ojeda, and Vilkaité-Vaitoné Citation2021).

While competing views on the dimensions of the museum experience and how to assess them remain, digital and online technologies and data offer new opportunities for analyzing the visit experience (Najda-Janoszka and Sawczuk Citation2021; Marini and Agostino Citation2021; Palumbo Citation2021). This study uses online user-generated content, which is a less intrusive method for assessing the museum visit experience (Kuflik, Boger, and Zancanaro Citation2012). This content consists of ‘spontaneous, insightful and passionate feedback provided by consumers that is widely available, free or low cost, and easily accessible anywhere, anytime’ (Guo, Barnes, and Jia Citation2017, 2), which provides the personal narratives of visitors. Although the richness of personal narratives of museum visitors is widely acknowledged (Dimache, Wondirad, and Agyeiwaah Citation2017; Lunchaprasith and Pasupa Citation2019; Jagger, Dubek, and Pedretti Citation2012), few studies analyze online reviews of museums (Craig Wight Citation2020; Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Dai Citation2021; Simeon et al. Citation2017; Su and Teng Citation2018; Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan Citation2019; Gursoy, Akova, and Atsız Citation2021). Rather than manually identifying dimensions of museum visitor experience, Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan (Citation2019) and Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Dai (Citation2021) perform automated analyzes of the content of online reviews. Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan (Citation2019) define the dimensions of visitor experience using LDA on online reviews; however, they analyze reviews of various tourist attractions in Phuket, Thailand rather than specifically focusing on museums. Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Dai (Citation2021) study the Terracotta Army Museum in China; however, they criticize the use of unsupervised topic models rather than using visitors’ narratives to identify specific dimensions of visit experience.

Despite recognizing the centrality of museum visitors (Deligiannis et al. Citation2020; ICOM Citation2007; Villaespesa and Álvarez Citation2020), the literature has not adequately used visitor narratives to assess dimensions of museum visitor experience (Gursoy, Akova, and Atsız Citation2021; Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Dai Citation2021; Simeon et al. Citation2017; Su and Teng Citation2018). In particular, research has not engaged in statistical automated analysis of online voices of visitors to identify dimensions of museum visitor experience (Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Dai Citation2021; Taecharungroj and Mathayomchan Citation2019). Our study eschews methodologies that use predefined dimensions and instead proposes automated analysis of online reviews in order to discover and assess the latent dimensions of the museum experience. We also explore differences in the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience based on the visitors’ cultural background.

Cultural differences in museum visitor experience

Various cultural tourism studies suggest that visitors’ cultural background shapes their experiences (de Carlos et al. Citation2019; Nakayama and Wan Citation2018; Phillips et al. Citation2020). This is particularly true in the museum context, where visitors’ cultural backgrounds impact how they perceive, interpret, and filter their socio-cultural distance from the site (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017; Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Imamoǧlu and Yilmazsoy Citation2009; Ang Citation2005; Md Ali et al. Citation2019).

Yet few studies have empirically explored this relationship (Cetin and Bilgihan Citation2016; Gil and Brent Ritchie Citation2009; Hogg, Liao, and O’Gorman Citation2014; Imamoǧlu and Yilmazsoy Citation2009; Jeanneret et al. Citation2010; Kirilenko, Stepchenkova, and Hernandez Citation2019; Trinh and Ryan Citation2017). These studies rely on proxies such as nationality or the visitor’s country of residence (Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Trinh and Ryan Citation2017), which are ‘crude’ indicators of the cultural background of visitors ‘in a world of increased migration’ (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017, 68), since nationality does not necessarily capture cultural background. We use the language of museum visitors in their online reviews to indicate cultural background and compare the latent dimensions of the experience between those writing in the local language and visitors writing in non-local language.

Methodology

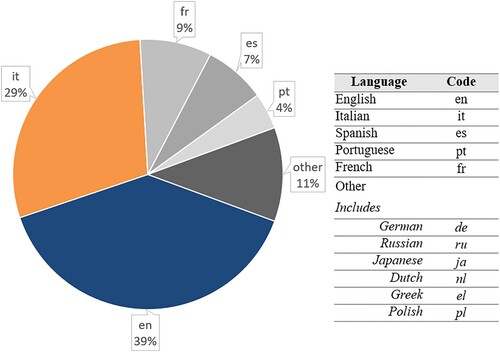

We compared the dimensions of the experience evaluated by local and non-local visitors from TripAdvisor reviews of the 30 most-visited Italian museums in 2019 (see Appendix for additional details). First, we collected 36,460 online reviews written between January and December 2019 on the TripAdvisor pages of these museums. We selected TripAdvisor since it is one of the largest online review sites globally (Liu et al. Citation2017). Each TripAdvisor webpage was certified for authenticity with museum managers before being entered in a customized Python system to download reviews automatically. Second, we automatically detected the language of each review and translated non-English reviews into EnglishFootnote1 (see ). At the end of this stage, we defined two separate datasets: one of 10.663 Italian reviews and the other of 25.797 non-Italian reviews (either written or translated into English).

Figure 1. Language distribution identified using Dandelion API (https://dandelion.eu/docs/api/datatxt/li/) on TripAdvisor reviews of museums. Language codes follow the two-letter coding ISO 639-1.

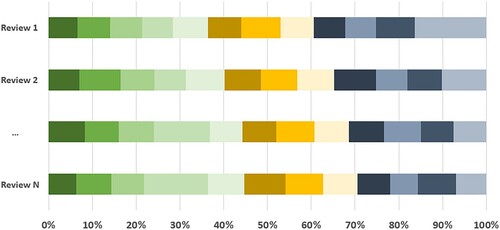

Third, we analyzed the text of Italian and non-Italian reviews. To model user-generated text, we selected LDA (Blei Citation2012) as it enables the identification of latent dimensions through an unsupervised Bayesian model without prior assumptions about the distribution of online reviews other than the existence of hidden semantic concepts. Using LDA, each review can be viewed as a composition of probability distributions over latent topics (), since latent topics are mixtures of semantically similar words that we interpreted as latent dimensions of the museum visitor experience as expressed in the reviews.

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the per-document topic proportions for each review – that is, the probability distribution of K = 12 latent dimensions over reviews.

Fourth, we compared the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience between reviewers writing in Italian and other languages. We identified three overarching conceptual dimensions of museum visitor experience and determined the probability that a review would include each dimension. Also, for each latent dimension, we selected exceptional reviews – that is, those reviews with a per-document topic probability of presenting the latent dimension

at exceeded the 95th percentile of the per-document topic probability over all of the reviews. We selected a high value of the probability distribution of observing each specific topic in order to extract only those reviews that were the most representative for the interpretability of the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience, in order to emphasize the subtle differences among these latent dimensions perceived by the two cross-cultural groups of visitors.

Results

Our results are presented in four parts. First, we discuss the dimensions of museum visitor experience that are shared among visitors across cultural background. In the second and third sections, we discuss the latent dimensions addressed by local and non-local reviewers. Finally, we offer a critical analysis of the latent dimensions of these two groups of visitors.

Museum visitor experience: shared perspectives

Comparing the 10,663 Italian reviews and 25,797 non-Italian reviews of Italian museums, we identified these three common dimensions:

Museum Cultural Heritage, a dimension related to museum artefacts, such as exhibited collection and artworks, as well as to the location’s heritage, such as the museum’s history and tradition, the cultural landscape, and the museum building.

Personal Experience, a dimension related to visitors’ descriptions of personal experiences or specific events that occurred during the visit, such as the encounter, perceptions and reactions to the site’s beauty, or personal suggestions to other visitors.

Museum Services, a dimension related to the services offered by museums, such as ticketing, guided tours, personnel and welcoming services, as well as key information for planning the visit, such as timing, queuing, and accessibility.

Museum visitor experience: the Italian perspective

The content analysis of the 10,663 Italian reviews allowed us to answer the first research question (RQ1). We found 12 latent dimensions of the museum visitor experience perceived by online reviewers who wrote in Italian. details each of these 12 latent dimensions, connecting them to the three overarching dimensions shared across local and non-local visitors.

Table 1. Latent dimensions of museum visitor experience from online reviews written in Italian.

Five latent dimensions addressed by Italian reviewers were related to Museum Cultural Heritage: ‘The Museum from Outside’, ‘Artistic Collection’, ‘Museum History & Tradition’, ‘Charming Antiquity’, and ‘Exhibition & Findings’. These five latent dimensions are connected to the museum heritage, as they include comments on exhibited collections and artworks, the museum’s history and tradition, as well as cultural landscapes and buildings, such as facades, churches, or castle descriptions. The following is an example of an Italian review with a high probability of observing the overarching dimension of Museum Cultural Heritage:

… Officially established in 1809 by the will of the Napoleonic government of Eugene of Beauharnais on the example of the Louvre, the picture gallery was enriched with various paintings from the looting carried out by French troops in the conquered territories and from those that derived from the heritage of the suppressed Lombard churches. There were added purchases and donations made in the following period. We point out the essential works. After the polyptych of Valle Romita, a masterpiece by Gentile da Fabriano with the coronation of the Virgin in the centre, we reach the room that houses Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini. Of the first, we remember the Madonna of the cherubs and the dead Christ, a work that reveals an emotional involvement of the artist … .Footnote2

We observed three latent dimensions related to Personal Experience: ‘At least once’, ‘Breathtaking’, and ‘Revisit & Expectations’. Emphasizing these latent dimensions, reviewers writing in Italian commented on the majesty of the museum and the ‘wow effect’ felt during the visit, and they suggested visiting the museum at least once in one’s lifetime. The following is an example of an Italian review with a high probability (47%) of observing the overarching dimension Personal Experience:

Well what to say to visit very nice safe tiring and great to go around all but very beautiful and once it must be visited for sure!!!!! (see note 2)

We observed four latent dimensions related to Museum Services: ‘Ticketing (purchase, price, book)’, ‘Hospitality’, ‘Guided Tours’, and ‘Must Know (Accessibility & Transport)’. Italian reviews that addressed the services offered by museums emphasized aspects such as ticketing, guided tours, personnel and welcoming service, and key information for planning the museum visit, such as timing, queuing, and accessibility. The following is an example of a review written in Italian with a high probability (31%) of observing the overarching dimension Museum Services:

Well organized museum, possibility to choose, through a special device, 3 different tours of the museum to listen to the explanations. There is the complete tour, which is the longest and most complicated, lasts 150 min. There is the short tour that it lasts 60 min, and there is the family tour, with less detailed explanations and stories suitable for children and it lasts 90 min. We did the complete one and it’s worth it, it’s really exciting. (see note 2)

Museum visitor experience: the non-Italian perspective

The content analysis of the 25,797 non-Italian reviews allowed us to answer the second research question (RQ2). We found 12 latent dimensions of the museum visitor experience perceived by online reviewers who wrote in languages other than Italian. details each of these 12 latent dimensions, connecting them to the three overarching dimensions shared across local and nonlocal visitors.

Table 2. Latent dimensions of museum visitor experience from online reviews written in non-Italian languages.

We recognized four latent dimensions addressed by non-Italian reviewers and related to Museum Cultural Heritage: ‘The Museum from Outside’, ‘Artistic Collection’, ‘Museum History & Tradition’, and ‘Charming Antiquity’. These four latent dimensions are connected to the museum artefacts and heritage, such as artwork and historical aspects, with particular reference to Romanesque antiquity. The following is an example of a non-Italian review with a high probability (36%) of observing the overarching dimension Museum Cultural Heritage:

The unique castle of the Rocca Scaligera of the twelfth century was built on the remains of an old roman fortress and is a dominant landmark of the spa resort of Sirmione on lake Lago di Garda. The entire fortress is surrounded by water … the highest tower is 37 metres … a spectacular view of the lake Lago di Garda and the entire peninsula of Sirmione. On a nice sunny day we made also ride a boat around the lake and the view of the castle was out of here a perfect.

We found two latent dimensions related to Personal Experience: ‘Worth Visiting’ and ‘Unfortunately’. These two latent dimensions were manifest in non-Italian comments that were appreciative or recommended visiting, as well as descriptions of unfortunate events like robberies outside the museum or scams connected to the visit and tickets. The following is an example of non-Italian review with a high probability (35%) of observing the overarching dimension Personal Experience:

I visited the Colosseum with my wife and it exceeded my expectations. Initially, to get away from the queues, we bought the Roma Pass, and we entered the straight … Entering the Colosseum was amazing. I felt a huge thrill, to be visiting the main symbol of Italy … Was the tourist attraction that impressed me the most in all of Italy and the visit is mandatory.

We observed six latent dimensions related to Museum Services: ‘Ticketing (line and book)’, ‘Access Hours & Ticketing’, ‘Guided Tours’, ‘Must Know’, ‘Take Your Time’, and ‘Museum Service Failure’. Reviews emphasizing these latent dimensions commented on ticketing, guided tours, personnel, and welcoming service; they offered suggestion for visitors for the planning of their visit, including timing, queuing, and accessibility. Non-Italian reviewers paid particular attention to timing issues, with comments on queues, the necessity of booking the visit, and the time that should be budgeted for a visit. The following is an example of an excerpt of a non-Italian review with a high probability (33%) of observing the overarching dimension Museum Services:

… I have done this same tour with another company 12 months ago but this was way superior. Mainly due to our guide Christian, a very passionate, knowledgeable and wonderful communicator (in English). I chose Crown Tours because this tour option was AUD $50 cheaper per person than all other options … .

A critical analysis of results

Both Italian and non-Italian reviews emphasized the three overarching dimensions of Museum Cultural Heritage, Personal Experience and Museum Services. However, a detailed comparison between the Italian and non-Italian reviews allowed us to answer the third research question (RQ3), identifying similarities and differences in the perception of the experience between local and non-local reviewers.

The comparative analysis reveals that Italian and non-Italian reviews ascribed different importance to the three overarching dimensions of a museum visit (see and ). Italian reviews discussed Museum Cultural Heritage with a probability of 41.5%, while this percentage was 33.4% for non-Italian reviews. On the contrary, the average probability of addressing Museum Services was higher in non-Italian (50%) than in Italian reviews (34%).

We also compared each of the latent dimensions expressed by Italian and non-Italian reviews at a fine-grained level (). With respect to Museum Cultural Heritage, we observed similar tendencies between Italian and non-Italian reviews, which both emphasized latent dimensions connected to cultural artefacts (‘Artistic Collection’ and ‘The Museum from Outside’) and history (‘Charming Antiquity’). However, we also observed some differences; the dimension ‘Exhibitions & Findings’ was clearly emphasized within Italian reviews but less prominent within non-Italian reviews.

Figure 3. Comparison of latent dimensions identified in Italian and non-Italian reviews that are related to the three overarching dimensions of museum visit – Museum Cultural Heritage, Personal Experience, and Museum Services.

With reference to Personal Experience, we identified both similarities and differences. Both Italian and non-Italian reviews credit praised the cultural sites, as indicated by the presence of ‘At least once!’ for Italian and ‘Worth visiting’ for non-Italian reviews. However, non-Italian reviews emphasized unfortunate experiences that occurred during the visits (‘Unfortunately’), such as language problems, scams, or robbery, aspects that were not identifiable as a latent dimension within Italian reviews. Italian reviews revealed a latent dimension associated with returning to the museum and expectations connected to this re-visit (‘Revisit & Expectation’), which was not discussed in non-Italian reviews.

For Museum Services, we observed similar attention among Italian and non-Italian reviews to the latent dimensions ‘Ticketing’, ‘Guided Tour’, and ‘Must Know’. However, Italian reviews placed greater emphasis on the latent dimension ‘Hospitality’ than non-Italian reviews did. Among non-Italian reviews, we identified the latent dimension ‘Museum Service Failure’, which emphasized problems with a variety of museum services beyond hospitality, such as lack of information and ticketing or booking issues. Non-Italian reviews also placed particular emphasis on time-related issues, highlighted by the specific latent dimensions ‘Access Hours and Ticketing’ and ‘Take Your Time’, which indicate the relevance of opening hours and budgeting sufficient visit time; these aspects were not emphasized in Italian reviews.

Discussion and conclusion

Main contributions

This study offers three main contributions for academics and practitioners. First, this study contributes to the academic debate around the identification and assessment of the dimensions of visitor experiences at museums. Our study empirically confirms the multifaceted dimensions of the experience showing the relevance of the socio-cultural context in museum visitor experience (Falk and Dierking Citation2012) and questions adopting predefined dimensions for the assessment of visitor experience based on surveys. Instead, we propose using an automatic topic model to analyze user-generated reviews; this method does not assume predefined dimensions (Prayag and Del Chiappa Citation2016; Oren, Shani, and Poria Citation2021; Richards, King, and Yeung Citation2020) but allows the dimensions of museum visitor experience to emerge from the visitors’ voluntary online reviews. The dimensions can be derived without surveying users or accessing their profiles, since the only information required about the user is the language in which they write online.

Second, this study uses online reviews that visitors provided voluntarily to identify their profiles. We empirically recognize the importance of language as proxy of cultural background (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017) and its impact in shaping the perception of the museum experience (Jia Citation2020). We empirically demonstrate that the online voices of visitors and the language in which visitors express themselves can reveal cross-cultural variation in the latent dimensions of visitor experience, which can then be leveraged upon to personalize the visitor experience, offer targeted services and design visitor-centered experiences. Rather than considering the home country of origin or the country of residence as factors influencing the museum experience, our results show the importance of language in identifying cross-country variation in the museum visit experience. Though we focused specifically on Italian museums, our results have a broader scope and contribute to the current debate on the influence of visitors’ cultural background on their museum experiences (Trinh and Ryan Citation2017; Falk and Dierking Citation2012; Imamoǧlu and Yilmazsoy Citation2009) and to the debate around museum visit experience and linguistic inclusion (Lyons et al. 2020; Lipovsky Citation2020; Jiang Citation2018). Indeed, we believe that future research in other museum settings may support further developments in the conceptualizations of visitors’ inclusion within the dimensions of museum visit experience, along with the relevance of language as a factor for museum visit experience.

At the managerial level, this study offers insights to museum managers on how to assess the visit experience. Museum managers can use online data from TripAdvisor to assess the latent dimensions of the experience. This avoids the limitations of visitors’ surveys, such as the risk of missing some latent dimensions of experience and of using non-exhaustive numeric measures that do not capture visitors’ thoughts fully. Finally, we provide insights on the latent dimensions of the experience for Italian state museums, showing policy-makers and museum directors that visitor origin (proxied by review language) is associated with different needs and perceptions. A clear understanding of the visitors’ needs can help managers identify priorities and tailoring services based on the types of visitors.

Future research

Our study is based on two main assumptions, whose relaxation may lead to future research. First, we separated reviews into those written in Italian and other languages, which included those written in English (39% of overall collected reviews) and reviews automatically translated into English from over 30 other languages (32% of overall collected reviews). Our aim was to consider the difference between local (Italian) and non-local (not Italian) perceptions of museum visitor experience; however, future work could analyze differences across more than two language groups, distinguishing museum visitors according to the language at a European or even worldwide scale.

Second, we analyzed the top 30 Italian state museums in terms of tickets sold in 2019 rather than a random sample. Our assumption was that these institutions share similar problems in terms of visitors’ management. Future research could look at other museums – for example, looking beyond national barriers, considering various forms of museum governance, or focusing on specific features, like the type of artistic collection.

Implementation costs

To support the replication of our study, we discuss the costs incurred in the collection, analysis, and interpretation phases. First, future researchers should be aware of the costs of collecting user-generated data from online platforms. This may require time to acquire knowledge of the specific platform of interest, which information is relevant, and from which web sources the data can be extracted. For example, we dedicated time to the selection of the TripAdvisor pages of the museums in our study and then extracted the text of the reviews only. Though this preliminary phase does not require technical skills, we suggest future researchers use automated collection during this preliminary phase; those interested in collecting online user-generated data may rely on free API systems (see for instance Twitter API: https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api), which use many free programming languages (see for instance R and Python: https://cran.r-project.org/; https://www.python.org/). In our case, this phase required technical skills as we implemented a Python system to collect automatically and store in a repository the text of the 36,460 TripAdvisor reviews.

Second, researchers should be aware of the technical costs of analyzing online user-generated text. This requires technical skills to process the qualitative information contained in text through a computer-based algorithm. Support documents for the automated analysis of online user-texts are available (see for instance https://monkeylearn.com/blog/what-is-text-analytics/; https://d99999oi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1387238). We used a free external service (i.e., Yandex) to identify the writing language and we programmed the code necessary to model text automatically in R, using pre-existing R packages for the qualitative information in the reviews.

Third, researchers should be aware of the costs of interpreting the results, which includes both technical and professional skills. Technical knowledge is required to interpret the output, while the professional knowledge of the specific context of museums is necessary to translate the output into substantive results. We interpreted the latent dimensions of the museum visitor in both analytical and contextual terms. Looking at statistically significant correlations between online expressions in written text, we derived 12 latent dimensions of the experience for local visitors and 12 for non-local visitors. We then read reviews and compared the dimensions identified for local and for non-local visitors in order to identify differences between the two linguistic groups.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paola Riva

Paola Riva is Ph.D. candidate in Management Engineering at Politecnico di Milano. After earning her Master degree in Mathematical Engineering in 2018 at Politecnico di Milano, she become a researcher at the Observatory Digital Innovation in Arts and Cultural Activities at Politecnico di Milano. At the intersection of Mathematics, Performance Management, Public Management and Culture, her Ph.D. research explores the role that automated techniques for the statistical analysis of online user-generated contents play for performance management of cultural institutions.

Deborah Agostino

Deborah Agostino is Associate Professor of Management Accounting at Politecnico di Milano, where she is the Director of the Observatory in Digital Innovation in Arts and Cultural Activities. She is co-director of the Executive Master in Management of Cultural Institutions at MIP Politecnico di Milano Graduate School of Business. Her research activities are focused on data analytics and digital innovation in cultural institutions. She is authors of over 30 publications in national and international journals on performance measurement and management in public institutions.

Notes

1 Italian stopwords: roma, colosseo, pantheon, pantheum, phantheon, pompei, Firenze; English stopwords: rome, colosseum, pantheon, pantheum, phantheon, Pompeii, Florence, Uffizi

1 For 98 reviews (0.27% of the total), the system (https://yandex.com/dev/translate/) did not recognize the language.

2 The original text of an Italian review is translated in English here in order to make it easier for international readers. We emphasize that the analysis of text has been performed on the original Italian text, as described in Methodology section.

References

- Ang, Ien. 2005. “The Predicament of Diversity: Multiculturalism in Practice at the Art Museum.” Ethnicities 5 (3): 305–320. doi:10.1177/1468796805054957.

- Arun, R., Suresh, V., Veni Madhavan, C.E., Narasimha Murthy, M.N. 2010. On Finding the Natural Number of Topics with Latent Dirichlet Allocation: Some Observations. In: Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. PAKDD 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, edited by Zaki, M.J., Yu, J.X., Ravindran, B., Pudi, V, vol 6118. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springe. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13657-3_43.

- Ayala, Iñigo, Macarena Cuenca-Amigo, and Jaime Cuenca. 2020. “Examining the State of the Art of Audience Development in Museums and Heritage Organisations: A Systematic Literature Review.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35 (3): 306–327. doi:10.1080/09647775.2019.1698312.

- Batat, Wided. 2020. “How Can Art Museums Develop New Business Opportunities? Exploring Young Visitors’ Experience.” Young Consumers 21 (1): 109–131. doi:10.1108/YC-09-2019-1049.

- Berland, M., de Royston, M. M., Lyons, L., Kumar, V., Hansen, D., Hooper, P., Lindgren, R., Planey, J., Quigley, K., Thompson, W., Beheshti, E., Uzzo, S., Hladik, S., Ozacar, B. H., Shanahan, M., Sengupta, P., Ahn, J., Bonsignore, E., Kraus, K., Kaczmarek-Frew, K., & Booker, A. 2020. Reframing Playful Participation in Museums: Identity, Collaboration, Inclusion, and Joy. In The Interdisciplinarity of the Learning Sciences, 14th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2020, edited by Gresalfi, M. and Horn, I. S., 3, 1503–1510. Nashville, Tennessee: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Blei, David M. 2012. “Introduction to Probabilistic Topic Models.” Communications of the ACM 55 (4): 77–84.

- Brida, Juan Gabriel, Marta Meleddu, and Manuela Pulina. 2016. “Understanding Museum Visitors’ Experience: A Comparative Study.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 6 (1): 47–71. doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-07-2015-0025.

- Castro, Yone, Juan Botella, and Mikel Asensio. 2016. “Re-Paying Attention to Visitor Behavior: A Re-Analysis Using Meta-Analytic Techniques.” Spanish Journal of Psychology 19: 1–9. doi:10.1017/SJP.2016.39.

- Cao, Juan, Xia Tian, Li Jintao, Zhang Yongdong, and Sheng Tang. 2009. A density-based method for adaptive LDA model selection. Neurocomputing, 72 (7–9): 1775–1781. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2008.06.011.

- Centorrino, P., A. Corbetta, E. Cristiani, and E. Onofri. 2021. “Managing Crowded Museums: Visitors Flow Measurement, Analysis, Modeling, and Optimization.” Journal of Computational Science 53 (July): 101357. doi:10.1016/J.JOCS.2021.101357.

- Cetin, Gurel, and Anil Bilgihan. 2016. “Components of Cultural Tourists’ Experiences in Destinations.” Current Issues in Tourism 19 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1080/13683500.2014.994595.

- Craig Wight, A. 2020. “Visitor Perceptions of European Holocaust Heritage: A Social Media Analysis.” Tourism Management 81 (May): 104142. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104142.

- de Carlos, Pablo, Elisa Alén, Ana Pérez-González, and Beatriz Figueroa. 2019. “Cultural Differences, Language Attitudes and Tourist Satisfaction: A Study in the Barcelona Hotel Sector.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (2): 133–147. doi:10.1080/01434632.2018.1493114.

- Deligiannis, Kimon, Paraskevi Raftopoulou, Christos Tryfonopoulos, Nikos Platis, and Costas Vassilakis. 2020. “Hydria: An Online Data Lake for Multi-Faceted Analytics in the Cultural Heritage Domain.” Big Data and Cognitive Computing 4 (2): 7. doi:10.3390/bdcc4020007.

- Deveaud, R., SanJuan, E. & Bellot, P. 2014. Accurate and effective latent concept modeling for ad hoc information retrieval. Document numérique, 17: 61-84. https://doi.org/10.3166/DN.17.1.61-84

- Dimache, Alexandru, Amare Wondirad, and Elizabeth Agyeiwaah. 2017. “One Museum, Two Stories: Place Identity at the Hong Kong Museum of History.” Tourism Management 63: 287–301. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.020.

- Eliseo, V., and L. Martine. 1991. Ethnographie de l’exposition. Etudes et recherche, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris: Bibliothèque publique d'Information.

- Falk, J. H., and Lynn D Dierking. 2012. The Museum Experience Revisited. The Museum Experience Revisited. California: Left Coast Press.

- Foster, Scott, Ian Fillis, Kim Lehman, and Mark Wickham. 2020. “Investigating the Relationship Between Visitor Location and Motivations to Attend a Museum.” Cultural Trends 29: 213–233. doi:10.1080/09548963.2020.1782172.

- Giaconi, Catia, Anna Ascenzi, Noemi Del Bianco, Ilaria D’Angelo, and Simone Aparecida Capellini. 2021. “Virtual and Augmented Reality for the Cultural Accessibility of People with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pilot Study.” International Journal of the Inclusive Museum 14 (1): 95–106. doi:10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/V14I01/95-106.

- Gil, Sergio Moreno, and J. R. Brent Ritchie. 2009. “A Comparison of Residents and Tourists.” Journal of Travel Research 47 (4): 480–493.

- Griffiths, T.L. and Steyvers, M. 2004. “Finding scientific topics”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 5228–5235. 10.1073/pnas.0307752101.

- Guo, Yue, Stuart J. Barnes, and Qiong Jia. 2017. “Mining Meaning from Online Ratings and Reviews: Tourist Satisfaction Analysis Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Tourism Management 59: 467–483. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.009.

- Gursoy, Dogan, Orhan Akova, and Ozan Atsız. 2021. “Understanding the Heritage Experience: A Content Analysis of Online Reviews of World Heritage Sites in Istanbul.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 3: 1–24. doi:10.1080/14766825.2021.1937193.

- Hashemi, Seyyed Hadi, and Jaap Kamps. 2018. “Exploiting Behavioral User Models for Point of Interest Recommendation in Smart Museums.” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 24 (3): 228–261. doi:10.1080/13614568.2018.1525436.

- Hogg, Gill, Min Hsiu Liao, and Kevin O’Gorman. 2014. “Reading Between the Lines: Multidimensional Translation in Tourism Consumption.” Tourism Management 42: 157–164. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.005.

- ICOM. 2007. “ICOM International Statuten.” http://icom-oesterreich.at/page/icom-international-statuten.

- Imamoǧlu, Çaǧri, and Asli Canan Yilmazsoy. 2009. “Gender and Locality-Related Differences in Circulation Behavior in a Museum Setting.” Museum Management and Curatorship 24 (2): 123–138. doi:10.1080/09647770902857539.

- Jagger, Susan L., Michelle M. Dubek, and Erminia Pedretti. 2012. “‘It’s a Personal Thing’: Visitors’ Responses to Body Worlds.” Museum Management and Curatorship 27 (4): 357–374. doi:10.1080/09647775.2012.720185.

- Jeanneret, Yves, Anneliese Depoux, Jason Luckerhoff, Valérie Vitalbo, and Daniel Jacobi. 2010. “Written Signage and Reading Practices of the Public in a Major Fine Arts Museum.” Museum Management and Curatorship 25 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1080/09647770903529400.

- Jia, Susan (Sixue). 2020. “Motivation and Satisfaction of Chinese and U.S. Tourists in Restaurants: A Cross-Cultural Text Mining of Online Reviews.” Tourism Management 78: 104071. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104071.

- Jiang, Chengzhi. 2018. “Bilingual Representation of Distance in Visual-Verbal Sign Systems: A Case Study of Guo Xi’s Early Spring.” Semiotica 2018 (222): 47–80. doi:10.1515/SEM-2015-0126/MACHINEREADABLECITATION/RIS.

- Juniarta, Nyoman, Miguel Couceiro, Amedeo Napoli, and Chedy Raïssi. 2018. “Sequential Pattern Mining Using FCA and Pattern Structures for Analyzing Visitor Trajectories in a Museum.” International Conference on Concept Lattices and Their Applications CLA2018: 231–242.

- Kawashima, Nobuko. 2007. “Knowing the Public. A Review of Museum Marketing Literature and Research1.” Museum Management and Curatorship 17 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1080/09647779800301701.

- Kelpšiene, Ingrida. 2019. “Exploring Archaeological Organizations’ Communication on Facebook: A Review of MOLA’s Facebook Page.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 7 (2): 203–214. doi:10.1017/aap.2019.9.

- Kim, Sukran, and Jaewoo Chung. 2020. “Enhancing Visitor Return Rate of National Museums: Application of Data Envelopment Analysis to Millennials.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 25 (1): 76–88. doi:10.1080/10941665.2019.1578812.

- Kirilenko, Andrei P., Svetlana O. Stepchenkova, and Xiangyi Dai. 2021. “Automated Topic Modeling of Tourist Reviews: Does the Anna Karenina Principle Apply?” Tourism Management 83 (September 2020): 104241. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104241.

- Kirilenko, Andrei P., Svetlana O. Stepchenkova, and Juan M. Hernandez. 2019. “Comparative Clustering of Destination Attractions for Different Origin Markets with Network and Spatial Analyses of Online Reviews.” Tourism Management 72 (January): 400–410. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.001.

- Komarac, Tanja, Durdana Ozretic-Dosen, and Vatroslav Skare. 2020. “Managing Edutainment and Perceived Authenticity of Museum Visitor Experience: Insights from Qualitative Study.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35 (2): 160–181. doi:10.1080/09647775.2019.1630850.

- Korani, Zohreh, and Kimiya Mirdavoudi. 2021. “A Cup of Tea in History: Visitors’ Perception of the Iran Tea Museum and the Ho Yan Hor Museum in the Modern Age (a Comparative Study).” Museum Management and Curatorship: 1–23. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1969681.

- Kosmopoulos, Dimitrios, and Georgios Styliaras. 2018. “A Survey on Developing Personalized Content Services in Museums.” Pervasive and Mobile Computing 47 (July): 54–77. doi:10.1016/J.PMCJ.2018.05.002.

- Kuflik, T., Boger, Z., Zancanaro, M. (2012). Analysis and Prediction of Museum Visitors’ Behavioral Pattern Types. In Ubiquitous Display Environments. Cognitive Technologies, edited by Krüger, A., Kuflik, T. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27663-7_10

- Kydros, Dimitrios, and Vasiliki Vrana. 2021. “A Twitter Network Analysis of European Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36 (6): 569–589. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1894475.

- Li, Zhao, Shujin Shu, Jun Shao, Elizabeth Booth, and Alastair M. Morrison. 2021. “Innovative or Not? The Effects of Consumer Perceived Value on Purchase Intentions for the Palace Museum’s Cultural and Creative Products.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 13 (4): 1–19. doi:10.3390/SU13042412.

- Limsui, Christian Y. 2021. “Perrugia: A First-Person Strategy Game Studying Movement Patterns in Museums.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 12790 LNCS: 345–354. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77414-1_25/FIGURES/5.

- Lipovsky, Caroline. 2020. “Shaping Learning for Young Audiences: A Comparative Case Study of Children’s Texts from Two Parisian Museums.” Visitor Studies 23 (2): 237–265. doi:10.1080/10645578.2020.1819744.

- Liu, Yong, Thorsten Teichert, Matti Rossi, Hongxiu Li, and Feng Hu. 2017. “Big Data for Big Insights: Investigating Language-Specific Drivers of Hotel Satisfaction with 412,784 User-Generated Reviews.” Tourism Management 59: 554–563. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.08.012.

- Lunchaprasith, Thanya, and Sarakard Pasupa. 2019. “The Contribution of Social Media on Heritage Experience: A Case Study of Samchuk Community and Old Market District, Suphanburi.” Proceedings of the European Conference on E-Learning ECEL 2019-November: 329–339. doi:10.34190/EEL.19.113.

- MacLeod, Suzanne, Jocelyn Dodd, and Tom Duncan. 2015. “New Museum Design Cultures: Harnessing the Potential of Design and ‘Design Thinking’ in Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30 (4): 314–341. doi:10.1080/09647775.2015.1042513.

- Manna, Rosalba, and Rocco Palumbo. 2018. “What Makes a Museum Attractive to Young People? Evidence from Italy.” International Journal of Tourism Research 20 (4): 508–517. doi:10.1002/JTR.2200.

- Marini, Camilla, and Deborah Agostino. 2021. “Humanized Museums? How Digital Technologies Become Relational Tools.” Museum Management and Curatorship: 1–18. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1969677.

- Martín-Ruiz, David, Mario Castellanos-Verdugo, and Ma de los Ángeles Oviedo-García. 2010. “A Visitors’ Evaluation Index for a Visit to an Archaeological Site.” Tourism Management 31 (5): 590–596. doi:10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2009.06.010.

- Md Ali, Zuraini, Rodiah Zawawi, Nik Elyna Myeda, and Nabila Mohamad. 2019. “Adaptive Reuse of Historical Buildings: Service Quality Measurement of Kuala Lumpur Museums.” International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation 37 (1): 54–68. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-04-2018-0029.

- Meneses, Gonzalo Díaz, Miriam Estupiñán Ojeda, and Neringa Vilkaité-Vaitoné. 2021. “Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace.” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16 (7): 2750–2767. doi:10.3390/JTAER16070151.

- Mesmoudi, Salma, Stanislas Hommet, and Denis Peschanski. 2020. “Eye-Tracking and Learning Experience: Gaze Trajectories to Better Understand the Behavior of Memorial Visitors.” Journal of Eye Movement Research 13 (2): 1–15 doi:10.16910/JEMR.13.2.3.

- Moreno-Mendoza, H., Agustín Santana-Talavera, and José Molina-González. 2021. “Formation of Clusters in Cultural Heritage – Strategies for Optimizing Resources in Museums.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 11 (4): 580–595. doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-12-2019-0155.

- Najda-Janoszka, Marta, and Magdalena Sawczuk. 2021. “Interactive Communication Using Social Media – the Case of Museums in Southern Poland.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36: 590–609. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1914135.

- Nakayama, Makoto, and Yun Wan. 2018. “Is Culture of Origin Associated with More Expressions? An Analysis of Yelp Reviews on Japanese Restaurants.” Tourism Management 66: 329–338. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.019.

- Nowacki, Marek, and Zygmunt Kruczek. 2021. “Experience Marketing at Polish Museums and Visitor Attractions: The Co-Creation of Visitor Experiences, Emotions and Satisfaction.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1080/09647775.2020.1730228.

- Oren, Gila, Amir Shani, and Yaniv Poria. 2021. “Dialectical Emotions in a Dark Heritage Site: A Study at the Auschwitz Death Camp.” Tourism Management 82 (May 2020): 104194. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104194.

- Palumbo, Rocco. 2021. “Enhancing Museums’ Attractiveness Through Digitization: An Investigation of Italian Medium and Large-Sized Museums and Cultural Institutions.” International Journal of Tourism Research 24: 202–215. doi:10.1002/JTR.2494.

- Phillips, Paul, Nuno Antonio, Ana de Almeida, and Luís Nunes. 2020. “The Influence of Geographic and Psychic Distance on Online Hotel Ratings.” Journal of Travel Research 59 (4): 722–741. doi:10.1177/0047287519858400.

- Ponsignon, Frédéric, and Maud Derbaix. 2020. “The Impact of Interactive Technologies on the Social Experience: An Empirical Study in a Cultural Tourism Context.” Tourism Management Perspectives 35: 100723. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100723.

- Prayag, Girish, and Giacomo Del Chiappa. 2016. “Antecedents of Heritage Tourists’ Satisfaction: The Role of Motivation, Discrete Emotions and Place Attachment.” 2016 Travel and Tourism Research Association Canada International Conference 3.

- Richards, Greg, Brian King, and Emmy Yeung. 2020. “Experiencing Culture in Attractions, Events and Tour Settings.” Tourism Management 79 (January 2019): 104104. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104104.

- Simeon, Maria I., Piera Buonincontri, Fernando Cinquegrani, and Assunta Martone. 2017. “Exploring Tourists’ Cultural Experiences in Naples Through Online Reviews.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 8 (2): 220–238. doi:10.1108/JHTT-10-2016-0067.

- Stylianou-Lambert, Theopisti. 2009. “Perceiving the Art Museum.” Museum Management and Curatorship 24 (2): 139–158. doi:10.1080/09647770902731783.

- Su, Yaohua, and Weichen Teng. 2018. “Contemplating Museums’ Service Failure: Extracting the Service Quality Dimensions of Museums from Negative on-Line Reviews.” Tourism Management 69 (August 2017): 214–222. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2018.06.020.

- Taecharungroj, Viriya, and Boonyanit Mathayomchan. 2019. “Analysing TripAdvisor Reviews of Tourist Attractions in Phuket, Thailand.” Tourism Management 75 (April): 550–568. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2019.06.020.

- Thurner, Mira. 2017. “Adult Audience Engagement: Learning in the Public Exhibition Space.” International Journal of the Inclusive Museum 10 (3): 1–11. doi:10.18848/1835-2014/CGP/v10i03/1-11.

- Tranta, Alexadra, Eleni Alexandri, and Konstantinos Kyprianos. 2021. “Young People and Museums in the Time of Covid-19.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36: 632–648. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1969679.

- Trinh, Thu Thi, and Chris Ryan. 2017. “Visitors to Heritage Sites: Motives and Involvement—A Model and Textual Analysis.” Journal of Travel Research 56 (1): 67–80. doi:10.1177/0047287515626305.

- Tsiropoulou, Eirini Eleni, Athina Thanou, and Symeon Papavassiliou. 2016. “Modelling Museum Visitors’ Quality of Experience.” Proceedings – 11th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization, SMAP 2016 November: 77–82. doi:10.1109/SMAP.2016.7753388.

- Tsiropoulou, Eirini Eleni, Athina Thanou, and Symeon Papavassiliou. 2017. “Quality of Experience-Based Museum Touring: A Human in the Loop Approach.” Social Network Analysis and Mining 7 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1007/s13278-017-0453-2.

- Villaespesa, Elena. 2019. “Museum Collections and Online Users: Development of a Segmentation Model for the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Visitor Studies 22 (2): 233–252. doi:10.1080/10645578.2019.1668679.

- Villaespesa, Elena, and Ana Álvarez. 2020. “Visitor Journey Mapping at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza: Bringing Cross-Departmental Collaboration to Build a Holistic and Integrated Visitor Experience.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/09647775.2019.1638821.

- Zancanaro, Massimo, Tsvi Kuflik, Zvi Boger, Dina Goren-Bar, and Dan Goldwasser. 2007. “Analyzing Museum Visitors’ Behavior Patterns.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 4511 LNCS: 238–246. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-73078-1_27.

Appendix

Table A1. TripAdvisor accounts retrieved by authors, in association to the 30 Italian museums that registered the highest number of tickets sold in 2019 according to the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Tourism: https://storico.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/sito-MiBAC/Contenuti/visualizza_asset.html_1000300163.html (last accessed July 2020).

A1. Methodological details on data analysis

To construct a document-term representation of textual data that is suitable for the application of the Bayesian model to the user-generated text, each of the two datasets of Italian and non-Italian reviews has been pre-processed with R software by means of lowercase conversion, elimination of specific characters (e.g., emojis, URLs, punctuation, and numbers), exclusion of language-specific and context-specific stopwordsFootnote1, and applying language-specific Porter’s stemming algorithms (see tm, SnowballC, and ldatuning packages).

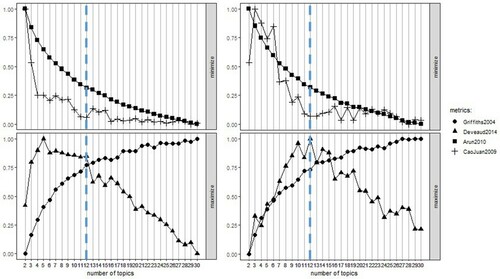

The choice of the most suitable number of latent topics discussed by Italian and non-Italian reviewers of museums has been based on the metrics proposed by (Arun et al. Citation2010; Cao et al. Citation2009; Deveaud et al. Citation2014; Griffiths and Steyvers Citation2004), with the number of topics varying between 2 and 30 and selecting the candidate number of latent topics following the elbow criterion (). For each of the models obtained from the selection of the candidate values, we checked the interpretability of the resulting latent topics, examining for each identified latent topic the 30 most probable stems as well as the content of reviews characterized by the highest probability of being associated with each specific latent topic. Repeating these steps for both Italian and non-Italian reviews separately, we were able to identify 12 highly interpretable latent dimensions of museum visitor experience for both Italian and non-Italian reviews, as depicted in .

Figure A1. Graphical representation of metrics used to determine the candidate number of latent topics discussed in Italian reviews (left) and non-Italian reviews (right). The graphics depict the value of each metric (y-axis) as a function of the number of latent topics (x-axis). The vertical dashed line highlights the selected number of latent topics.

The interpretation and comparison of the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience identified by Italian and by non-Italian reviewers lead us to identify three overarching conceptual dimensions of museum visitor experience, which have been compared in terms of the average probability that a review addresses each overarching dimension of museum visit.

Specifically, for each review , we define the probability that the review

addresses the

overarching dimension of museum visitor experience as:

where

is the probability that the review

addresses the latent dimension

(i.e., topic proportion for topic

in review

) and

is the set of latent dimensions that we associated with the

overarching dimension

. Then, we compared the average probability that a review addresses each overarching dimension of museum visitor experience

for each

overarching dimension shared across both Italian and non-Italian reviews.

To further the comparison, for each latent dimension of the museum visitor experience, we selected only exceptional reviews – that is, those reviews that have a probability

of presenting the latent dimension

over the 95th quantile of

, which is the distribution of the latent dimension

over reviews. We selected a high value of the probability distribution of observing each specific topic in order to extract only those review which are statistically most representative for the interpretability of the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience. The main reason behind this rationale was to identify, emphasize, and discuss the subtle differences among latent dimensions of museum visitor experience perceived by the two cross-cultural groups of visitors. Indeed, following this logic enabled us to further exemplify the latent dimensions of museum visitor experience according to the perspectives of Italian and non-Italian reviewers.