ABSTRACT

This study challenges institutionalised collection and documentation practices at museums, providing a space for the reconfiguration of concepts and boundaries of collections data with respect to digital objects in particular. While various technology-driven approaches have been introduced for the management of collections data, little attention has been given to the nature of collections data and how museums can gather them to improve plurality. As part of the experimental project titled Content/Data/Object at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, this research analyses the public workshop wherein participants discussed a digital object at the museum (i.e., Minecraft) as a case study and proposes a conceptual framework with expanded concepts of collections data and possible documentation methods. It provides museums with a dynamic model to diversify collections data that is able to reflect the various needs of the public and allow the interpretation of our heritage to flourish.

Data of museum collections in a digital age

Data about museum collections are fundamental for the digital services of museums (Cameron and Robinson Citation2010; Pavlidis Citation2019). Vast amounts of data on museum collections have been produced via digital transformation in museums since the mid-twentieth century (Cameron and Kenderdine Citation2010; Parry Citation2010). Globally accepted data standardisation, glossaries and controlled vocabularies for museums’ collection records have increased the interoperability and efficiency of collections data management and data exchange for museum research and practices (Bearman Citation2010; Skinner Citation2014). Recent initiatives for the redevelopment of museums’ collections management systems (CMSs) further emphasise the connectivity of such systems to internal content management systems, and other cultural institutions’ systems with linked data models, challenging existing systems designed to work in isolation (Freire Citation2020; Devine and Royston Citation2021; Dutia and Stack Citation2021; Giannakoulopoulos et al. Citation2021).

This paper highlights the need for a shift from the static model of collection and documentation practices, which convey a singular voice of a certain aspect of museum collections, to a dynamic model that reflects plural aspects. The current standardised, institutionalised collection and documentation practices are based primarily on the perspectives of subject-oriented experts (Cameron Citation2008; Cameron and Robinson Citation2010; Park Citation2021). Such practices regard collections data as objective and factual and fail to fully acknowledge the plural aspects of collections (Park Citation2021). This inability leads researchers to revisit what collections data should be (i.e., the epistemology of data) and how museums can gather them (i.e., methods) to improve the plurality of collections data. A few exceptional research projects that aim to discuss such issues are driven by perspectives of decolonisation that challenge inscribed human biases in data and relevant systems, which are affected by westernised thinking and elitism (Turner Citation2015; Kizhner et al. Citation2021).

Notably, digital objects in museums further challenge the current static collection and documentation practices (Delve and Anderson Citation2014; Foti Citation2018; Rees Citation2021). Museum practices developed basically for physical objects do not provide suitable frameworks for digital objects (e.g., video games) that have a performative, experiential or hybrid nature (physical/material and intangible/immaterial) (Kirschenbaum Citation2008; Drucker Citation2013; Geismar Citation2018). When applying a static model of the current protocols of collections documentation, such natures of digital objects cannot be recorded because of the requirement of additional approaches (Park Citation2021; Rees Citation2021). This research adopts participatory bottom-up approaches concerning collections documentation to materialise multiple actors’ voices on digital objects at museums (Park Citation2021). Public participation in collections documentation is studied through experimental forms of social tagging (Trant Citation2009; Pennington and Spiteri Citation2019) and crowdsourcing methods (Ridge Citation2014). However, there is a gap between such research-driven data enrichment methods and museum practices as they are rarely adopted by the museums (Stimler, Rawlinson, and Lih Citation2019; Park Citation2021).

This study discusses the public workshop wherein workshop participants discussed a digital object, Minecraft, as a case study, and proposes expanded concepts of collections data and possible methods for gathering them with the help of computing technologies to deepen discussions on the epistemology of collections data and the practical methods of collections documentation to ensure plurality in collections data. Analysis of the public online workshop is followed by a section on research methodology, which continues building the argument for a dynamic model of collection and documentation practices at museums, whereby partnerships are formed beyond the museum sector.

Public workshop as a research method

Context of the research project Content/Data/Object at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A)

The research presented in this paper is part of a cross-departmental research project titled Content/Data/Object that was conducted within the V&A Research Institute (2017–2021) to address the challenges of collecting, documenting, displaying and preserving digital objects at the museum. The V&A, whose collections include art and design objects from the ancient times to the present day (V&A Citation2019), has recently expanded its institutional interest to collecting digital objects (e.g., software, digital devices and video games) with the formation of the new collection department called Digital, Architecture and Design (DAD) in 2015 (V&A Citation2019, 9). As a Data Research Fellow of the research project, I was contributing to the theoretical understanding of such objects’ digital materiality in a museum context (Park and Samms Citation2019), articulating challenges that curators experienced when documenting digital objects on the museum's CMS (Park Citation2021). For example, the system does not allow space and methods for curators to record the performative, experiential aspects of such objects, which can be materialised through the involvement of those who have actually used the objects. This approach requires both a conceptual and practical shift in museum practices because involving objects’ users in collection and documentation practices is rare at museums. Such practices were just considered the professionalism of trained, experienced curators. Thus, I planned and conducted a public workshop in January 2021 to better understand the perspective of digital objects’ users as well as the public's expectations of data on the museum's digital objects, which can be found in the museum's online catalogue through ‘Search the Collections’.

Aim and research questions

This study intends to provide a space for the reconfiguration of the concepts and boundaries of collections data related to digital objects in particular. Accordingly, the following research questions were targeted.

What stories and data about digital design objects of the museum do the public believe are important to capture and record for future generations? How can that be conceptualised?

How can such data be gathered with the help of computational methods?

Research design

The V&A values public engagement events (e.g., talks, seminars and workshops) not only for the distribution of research findings but also to invite the public into the research process. In particular, a workshop on research methods can facilitate deep conversations on a specific topic, encouraging fruitful group discussions and the exchange of opinions between participants (Orngreen and Levinsen Citation2017). To offer a space where the public can actively participate in a dialogue with each other and the researcher and engage in the learning experience, a public workshop as a research method was chosen over other qualitative data collecting methods for this study.

A public workshop was designed to identify gaps between the metadata in use in the museum's CMS and data that the public expects to find in the museum's online catalogue. The workshop was not intended to develop and propose a metadata schema in detail. Rather, it sought to learn from participants and build a theory based on the grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss Citation2014). Testing the usability of the museum's CMS and comparing and evaluating the metadata schema for museums’ digital objects was not the objective of this study, which had been the main purpose of other researchers (Lee et al. Citation2013; Delve, Pinchbeck, and Bergmeyer Citation2014; Lee, Clarke, and Perti Citation2015; Chapman Citation2021). This literature was not irrelevant to the current research, but the research team wanted to avoid introducing constraints that could impact the thoughts and opinions of the workshop participants. The workshop was designed to give workshop participants a safe, open space to discuss and share their thoughts with the research team and other participants and provide consultancy to improve the collection and documentation practices at the museum. Moreover, the public workshop-driven suggestions can contribute to the future re-development or re-design of the CMS and collection and documentation practices.

Instead of museum professionals, members of the general public were invited to reflect the interest of the museum and the research team. A call for participants was selectively circulated to a few groups, including V&A adult volunteers, university students and researchers who might be interested in the intersection of museums, art, design and digital technology. Altogether, 24 people joined the workshop. The study was conducted following the museum's internal protocols for research ethics and data management. All workshop participants signed consent forms allowing the recordings of their oral communications to be analysed and used, in tandem with the artefacts produced during the workshop; all data presented in this paper are anonymous.

For the case study, the video game Minecraft (object number: B.94-2015), which is a sandbox game where game players can use the virtual game environment in various ways, was chosen through discussions and consultation with the museum's curators, mainly because of its popularity among the public. The V&A houses various types of digital objects (e.g., digital devices, software and video games) (V&A Citation2019, 12–13). Though the video game may not be considered representative of all digital objects at the museum, it certainly possesses their key features, such as digitality, interactivity, performativity, associations with digital tech companies and individual creators and so on, which allow discussions about the workshop to be diverse and relevant to the context of the museum.

The online workshop programme

Due to the outbreak of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in early 2020, the workshop moved online, using Miro for interactive activities and Microsoft Teams for oral communication.

To ensure that workshop participants were familiar with the topics of the workshop in advance, they were asked to complete pre-tasks to help them learn about the workshop's context. They were expected to read a section about the DAD's collections in the V&A's collections development policy document, watch two videos (i.e., one on metadata, one on Minecraft) and complete a board on Miro to gain hands-on experience with the new digital tool before the workshop.

Workshop participants were categorised into five small groups to ensure active participation and discussion, with four to five people in each group. The two-hour-long workshop programme included an icebreaker activity, a short presentation about Content/Data/Object and two interactive activities. In Activity 1, workshop participants worked as a group to categorise their initial writing after they had written their thoughts about data and stories that were important to collect and record about Minecraft on individual Miro boards. In Activity 2, the new categorisations they had created were compared with the metadata used at the museum for video game records.

Data analysis

The workshop participants’ discussion was recorded in digital files and transcribed to facilitate qualitative data analysis. A coding process (Corbin and Strauss Citation2014) was used to facilitate comparisons among the five different groups of participants. Coding facilitated the creation of key themes that were frequently discussed among the groups. Moreover, the categorisations created by the workshop participants on Miro boards during Activity 2 acted as visual data to increase the triangulation of data analysis. The purpose was to identify emergent or repetitive themes in the data for a better understanding of the public's expectations of collections data.

The public’s expectations of data on the museum object, Minecraft

This section highlights five key points discussed in the workshop, with participants’ quotes, to propose a conceptual framework for the reconfiguration of the epistemology of collections data and alternative computational methods for collections documentation. First, data about museum collections are presented in a wider social context, after which the concept of object makers is provided. Subsequently, data about objects in use, data about the object's life and data about the technical description of museum objects for the future are presented one after the other. Ultimately, this section articulates why a shift to a dynamic model of collection and documentation practices is necessary to reflect the public's expectations of data around digital collections at museums.

Data about museum collections in a wider social context: games as socio-cultural media

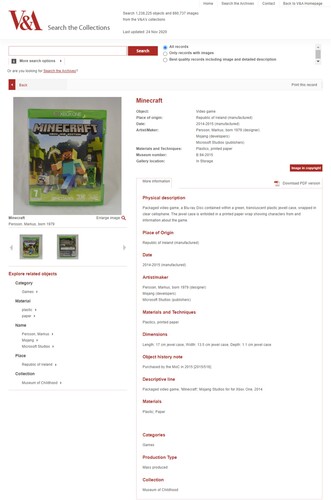

The data about Minecraft available on the museum's current online catalogue (refer to ) showcase the game as an end product created solely by the maker (e.g., Mojang [developers], Microsoft Studios [publishers], Markus Alexej Persson [designer]). Workshop participants expressed disappointment because, for instance, the Wikipedia page of Minecraft contains richer information than the corresponding museum catalogue page. Workshop participants expect more data to be available on the museum's object record page online, with connections showing the game as part of the contemporary media environment.

Data that workshop participants expect to find on the museum's online catalogue include detailed information about not only the game itself but also its relationship with other media and events in society. They suggest that the museum should document details, such as the type of game (sandbox), visual style (pixelated, square, boxy), genre, release dates of each version, prices, ratings and so on. These suggestions echo the metadata schema that other researchers have developed for the documentation of video games (Lee et al. Citation2013; Chapman Citation2021). Participant A explains:

‘When we were talking about Minecraft, I thought things like, what genre of the video game is it, and what platforms is it on. I feel like having that in a structured form is quite important’.

‘I put that rating there because I think it is about … Well, I mentioned PEGI (Pan-European Game Information) here. It's an institute that's assessing games and judging whether they’re suitable for everyone to play, or you have to be, say, seven years and older or you have to be an adult to play a game. I think that's about social issues’.

‘I know we keep going back to it, the rating one. I think it is really interesting in a way that it is just a fact about the game, but it explains so much more than just … It's not just a piece of information. It has a narrative around it, which you wouldn't think about immediately. It tells a story about the game and the society’.

Workshop participants also recommended gathering archival materials. For example, published articles from magazines about the game and its subculture should be prioritised, which can enrich contemporary collections. This area is an intersection between museums and archives, where both can work together. Each has its own standards and protocols for collection and documentation that have not been well connected yet. For example, one of the issues in data practices at the V&A is designing a system that could connect the CMS to its digital archive catalogue (Price Citation2019). More research is required to overcome such siloed systems and connect them under a dynamic model to improve the plurality of collections data (Giannini and Bowen Citation2022).

Expanded concept of object makers: game players as co-creators

One of the categorisations that all five groups of workshop participants created focuses on game players (i.e., users of the game software). Highlighting the interactivity and participatory features of the game as key elements, they shared that they expected to find data about game players, who can be understood as co-creators of the game, in the museum's online catalogue. Workshop participants believe that the official creators of the game only provided a foundation of the basic environment. They understand that users contribute to building and developing the meanings and values of the game while playing it and participating in discussions within user communities. They believe that game players are as significant as game developers (makers). Some participants, including Participant D and Participant E, even shared that they think that game players are game makers to some degree as they creatively use and enlarge the game platform in unexpected ways.

Participant D: ‘I feel like the museum takes quite a narrow view of what it means to be a creator or a maker. The game here might have been developed or conceptualised by a person, but it is made by communities of practice. All of the features that we’re drawing out have to do with that community-generated identity rather than, this is the game, these are the features. But that's a really big conceptual shift to cataloguing’.

Participant E: ‘I realise that it is a digital collection. So, what's the difference between digital collections and physical collections. That's why I changed one group's name to ‘user’ because, especially for Minecraft, it offers high engagement to players. The worlds, the buildings and everything created in the game are not created by the producers. They only provide you with some basic elements. All the magnificent things are created by the users. So involving the users’ part in the records of this collection is highly important’.

It is interesting to see their understanding of game players because this understanding can be understood through the digital culture, where the boundary between producers (makers) and consumers has blurred (Arakji and Lang Citation2007; Baldwin and von Hippel Citation2011). However, no data or metadata records game players in the current object records of the game at the museum. Museums need to reconceptualise the meaning of object makers with the reflection of contemporary digital culture, wherein digital users have significant roles not only as consumers but also as co-creators. Hence, a dynamic model of collection and documentation practices is imperative to reflect the wider notion of digital object makers.

Data that workshop participants would like to acquire most about game players include demographic data (age, sex, geographic location, etc.), data evidencing the game's worldwide popularity (e.g., number of users, number of downloads, etc.), data regarding game addiction, gameplay footage and related data (e.g., average or maximum gameplay duration, etc.). These kinds of data are quantitative and statistically measurable. Digital objects like video games are reproducible, unlike a physical object or a piece of artwork, so multiple copies co-exist with the same monetary value. Workshop participants see the video game, the museum object, as a representative of other mass-produced copies of the game. Via statistical data, numerous game players worldwide can be shown in terms of patterns and numbers. Museums recently began to seek opportunities to apply data science methods, such as data visualisation, in practice and research (Davis, Vane, and Kräutli Citation2016; Topaz et al. Citation2019; Villaespesa and Crider Citation2021). However, the documentation practices at museums have been developed solely to accompany objects with descriptive textual data, and statistical data have not been introduced to museum documentation practices yet. Thus, it would be worth exploring the possibility of computational methods for collection documentation at museums. At the same time, collecting data about game players requires ethical considerations, even though the data can remain anonymous. For instance, who would govern such data (i.e., the museum or the game development company)? How can museums as public institutions ensure the transparency of such data under a partnership with private game companies? Answering these ethical questions is beyond the scope of this paper, but museums should consider them in advance.

Other data types that workshop participants expect to know are qualitative, including data about the purposes of gameplay, changes in gameplay over time, and gameplay experience. Workshop participants specifically mentioned data that can contextualise fan-based Minecraft culture (e.g., Minecon) and online user communities around the game several times. They recommend recording interview data to present an oral history of game players alongside the game object. Community archives around the game are also noted as important resources to be preserved with the object. In terms of the practicality of these suggestions, however, museums should consider the nature of human resources that they can use when experiencing financial challenges due to funding cuts. Therefore, museum practitioners must have relevant skillsets (and proper training) to collect qualitative data, such as interview data and oral history data, and not many museums have such resources. Working with skilful volunteers could be an option to consider, but critical discussions around unpaid workers in arts and culture sectors nowadays should be acknowledged as well (Holmes Citation2006; Brook, O’Brien, and Taylor Citation2020).

Data about objects in use: user-created contents

In conjunction with data about game players, workshop participants expect to see examples of user-created content and related data on the video game's object page online. They understand that user-created content is crucial to understanding the game culture, as it represents what the game is about and how it works.

Overall, two types of user-created content were discussed in the workshop. The first type involved examples that were created by game players within the world of Minecraft, including virtual buildings, terraforming and other artefacts. More specifically, significant derivatives that game players created (e.g., the Uncensored Library) were recommended for collection and documentation. The Uncensored Library in Minecraft (The Uncensored Library Citationn.d.) is a well-known case wherein the game platform is used as a medium to distribute news that is locally censored. In this way, the game functions as a platform upon which game players present their creative outputs. Moreover, screenshots of virtual structures or recordings, like a demo video, were suggested as viable collection methods. Exporting Minecraft creations into different digital systems, such as Paint 3D, can also preserve artefacts in separate files. Digital preservation strategy (Delve and Anderson Citation2014; Owens Citation2018) and digital objects’ ownership and copyright issues (Fouseki and Vacharopoulou Citation2013; Liddell Citation2021) should be considered for such digital objects. The application of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) could provide a method to ensure the originality of such objects as it has already been implicated in digital collections at some museums and galleries (Valeonti et al. Citation2021). The sustainability and applicability of the technology should be first discussed in the museum sector to build a common ground since such an approach is still in its infancy in terms of development and acceptance in society.

The second type of user-created content discussed in the workshop was digital content published and shared in other media formats and social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitch. Game players exchange their experience, knowledge, thoughts and ideas with other players while using various media platforms. This activity also contributes to how the game is popularised and publicised. Even non-players can learn what the game is about by watching live streams of gameplay online, reflecting the evolution of game culture that must be understood within a digital online media ecosystem (Arakji and Lang Citation2007; Johnson and Woodcock Citation2019). Particularly, workshop participants suggest documenting game players’ live discussions in online forums that even influence game development and updates. Participant F further explains:

‘For example, posts in the communities have really gotten the entire community's attention. For example, if Minecraft has a new update, people would be discussing how this update might affect gameplay. So, there are like 10,000 long-post replies. That might be worth recording, right’.

Data about the object's life: evolution of game development as a collective effort

According to the official website of Minecraft, the game has been continuously evolving since its launch in 2009. Workshop participants see the game in the museum collection as part of the continuity of the game's evolutionary path, rather than understanding it as a unique, isolated and separate object. They consider the date of creation of the object as only a point in the object's biography and expect to see data that demonstrates the entire life of the object from its initial launch. Participant G notes:

‘I think the difficulty of trying to produce metadata of something like Minecraft is that you’re dealing with a platform, and a platform is not a discrete object. It slowly changes and evolves. It gets vetted and it's huge’.

Moreover, workshop participants expect the museum to record data about the people involved in various processes of the game's development instead of only acknowledging the specific creator of the initial version (i.e., Markus Alexej Persson). They perceive the game's development as a collective effort. Although the creator may have come up with the initial idea, various people's contributions to its development enable its global success. Documenting only the initial creator's name on the object record does not fully reflect the entirety of the process. Like the long lists of credits customary in commercial films, the workshop participants expect the people involved in the game's development to be acknowledged and named in the object record. Participant H emphasises:

‘I assume this problem exists for a lot of other items in the V&A's collection, but because it's kind of a collective project, you’ll end up with a lot of names, like the one who worked on the soundtrack, or those who contributed to the design, did a bit of programming, or provided artwork. I feel like that's another interesting thing to record. It is kind of noting the different roles that people have in a more nuanced idea of like who made it’.

Workshop participants also suggested the collection of archival materials, such as designers’ and developers’ working notes and oral history from game sound composers, to, for example, materialise different aspects of the object's life. These kinds of materials have been on display when the V&A had an exhibition on video games in 2018 (Foulston and Volsing Citation2018). Rather than applying such practice for only the show, museum sectors need to build a shared protocol to continue developing methods for digital collection and documentation.

Data about the technical description of museum objects for the future: digital preservation and research in the future

Workshop participants, especially those who played the game, clearly recognised the challenges of preserving the game for future generations and the importance of rich documentation concerning the technical aspects of the game and gameplay. They expect information on the object record page to not only be about the devices on which the game can run but also regarding the digital infrastructures that underpin the game and make its development and playability possible. Participant I stated:

‘It's interesting to think about the materiality of extending beyond this one object, the whole kind of infrastructure that it requires. Obviously, recording more things about the production process will be quite useful for long-term preservation, which is really important. … Only collecting the game disc is completely pointless if you’re not collecting the whole infrastructure around it because it's a naive assumption that they’re still going to be able to loan an X-Box and a TV that can plug into the X-Box 50 years later’.

Towards a dynamic model of collection and documentation practices at museums

This study has opened a topic on digital collections with the consideration of the epistemology of collections data and data collection methods. With a case study on a digital object at the museum, this research signifies the need for the conceptual and practical shift in collection and documentation practices at museums from a static model to a dynamic model that invites the public to collaborate beyond the museum sector and apply computational methods to reflect the plural aspects of digital objects. Digital collection cannot be conducted in a siloed manner at museums as it requires collaborations with multiple actors. The data analysis of the public online workshop revealed that the public is unsatisfied with the conservative approach of data collection the museum currently maintains within a static model. Workshop participants’ expectations of collection data are both extensive in terms of volume and diversity as they view museum objects as video games embedded in a complex society, associated with various actors and elements and evolving continuously. They have requested museums to record data about individuals who have not yet been acknowledged as co-creators in the current object records (e.g., game players, communities of users and people involved in various stages of game development). Hence, they expect that various stories can be told via museum objects. Regarding methods of data collection, mixed computational and qualitative methods were anticipated. Computational methods can even provide new opportunities to capture the plurality of collections data (e.g., multiple users’ data in the pattern), which will introduce fundamental changes to museums’ object records and documentation practices.

Three directions for future research are proposed in this paper to further study the dynamic model of collection and documentation practices at museums. First, a system for collections documentation can be prototyped through a combination of Web 2.0 approaches (e.g., participatory documentation [Srinivasan et al. Citation2009; Alemu Citation2018] and social tagging [Trant Citation2009; Pennington and Spiteri Citation2019]), which invite anonymous members of the public to join the process of object documentation, with Web. 3.0 approaches (e.g., semantic web and linked data technology). Notably, the moderation and trustworthiness of data should be critically considered. Second, as an experimental attempt at dynamic data gathering with the application of artificial intelligence technology, systematic solutions that support automatic aggregation from various resources can be designed to collect and document data associated with museum-digital objects. This approach might also require a critical investigation of data ethics when aggregating and managing data at museums. Third, it might be interesting to compare the public's expectation of physical collections data with one of the digital objects, similar to the ones studied in this paper, thus helping museums handle both objects under one integrated system.

I acknowledge the methodological limitations of this research design. Firstly, the workshop participants who contributed to the research may not fully represent the general publicFootnote1 due to their semi-professionality in subject areas such as design and museums. Although the workshop discussions were fruitful because of their expertise, their opinions and ideas might also have been framed according to their educational backgrounds. Secondly, the resources provided to them for the pre-tasks might have impacted the thoughts and ideas they presented and discussed in the workshop. However, those resources could have also helped to build common ground and a shared understanding among the participants, especially for those who were unfamiliar with the video game and the concept of metadata.

Various data types about museum objects co-exist and narrate different stories. Museums should revisit the conventional collection and documentation practices and ask about aspects missing in terms of the plurality in collections data. A dynamic approach to such practices, which invites the public and facilitates collaboration with other partner institutions for the plurality and enrichment of collections data, will help museums to be more relevant in our society. Transparent collection, documentation and presentation of collections data from various resources will allow our understanding of museum collections to expand.

Geolocation information

United Kingdom (UK).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the members of the research team, Marion Crick, Corinna Gardner, Natalie Kane, Richard Palmer and Anouska Samms, for sharing their thoughts and fruitful discussions, together with the V&A Research Institute for its enormous support in multiple ways. The author would also like to thank all the workshop participants for their time, collaboration and valuable insights. Without their contributions, this study would not have been possible.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to the V&A internal policy. The data may be available on direct request to the museum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Juhee Park

Juhee Park was a Data Research Fellow working on the research project Content/Data/Object (2017 - 2021) at the V&A where the study of this paper was conducted. Currently, she is a Senior Researcher at the Augmented Reality Research Center (ARRC) at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) in Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

Notes

1 I admit that it was not easy to define ‘the general public’ and to invite them to the research workshop. The research team, including me, endeavoured to have an open mind when sending out a call for research participants and choose potential participants having various backgrounds if possible. However, it is a limitation of this research that it was unsuccessful in involving those people who do not visit museums often. It will be worth conducting future research that invites non-regular museum visitors and compare their thoughts on collections data with those of regular museum goers. This comparison will help museums understand diverse communities in our society.

References

- Alemu, G. 2018. “Metadata Enrichment for Digital Heritage: Users as Co-Creators.” International Information & Library Review 50 (2): 142–156. doi:10.1080/10572317.2018.1449426.

- Arakji, R. Y., and K. R. Lang. 2007. “Digital Consumer Networks and Producer-Consumer Collaboration: Innovation and Product Development in the Video Game Industry.” Journal of Management Information Systems 24 (2): 195–219. doi:10.2753/MIS0742-1222240208.

- Baldwin, C., and E. von Hippel. 2011. “Modeling a Paradigm Shift: From Producer Innovation to User and Open Collaborative Innovation.” Organization Science 22 (6): 1399–1417. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0618.

- Bearman, D. 2010. “Standards for Networked Cultural Heritage.” In Museums in a Digital Age, edited by Ross Parry, 48–63. London: Routledge.

- Brook, O., D. O’Brien, and M. Taylor. 2020. ““There’s No Way That You Get Paid to Do the Arts”: Unpaid Labour Across the Cultural and Creative Life Course.” Sociological Research Online 25 (4): 571–588. doi:10.1177/1360780419895291.

- Cameron, F. R. 2008. “Object-Oriented Democracies: Conceptualising Museum Collections in Networks.” Museum Management and Curatorship 23 (3): 229–243. doi:10.1080/09647770802233807.

- Cameron, Fiona, and Sarah Kenderdine. 2010. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cameron, F., and H. Robinson. 2010. “Digital Knowledgescapes: Cultural, Theoretical, Practical, and Usage Issues Facing Museum Collection Database in a Digital Epoch.” In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, edited by Fiona Cameron, and Sarah Kenderdine, 165–191. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Chapman, A. 2021. “Trials of Metadata: Emerging Schemas for Videogame Cataloguing.” Journal of Library Metadata 21 (3–4): 63–103. doi:10.1080/19386389.2021.2007729.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Davis, S. B., O. Vane, and F. Kräutli. 2016. “Using Data Visualisation to Tell Stories about Collections.” In Proceedings of the Electronic Visualisation and the Arts (EVA) Conference. London, UK, July 12–14. Accessed 5 Feb 2022 http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2016.44.

- Delve, J., and D. Anderson. 2014. Preserving Complex Digital Objects. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

- Delve, J., D. Pinchbeck, and W. Bergmeyer. 2014. “Preserving Games Environments via TOTEM, KEEP and Bletchley Park.” In Preserving Complex Digital Objects, edited by Janet Delve, and David Anderson, 217–234. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

- Devine, C., and C. Royston. 2021. “Approaches to Developing Industry-Wide Technology Solutions.” American alliance of museums virtual conference. Online, June: 7–11.

- Drucker, J. 2013. “Performative Materiality and Theoretical Approaches to Interface.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 7 (1). http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/7/1/000143/000143.html.

- Dutia, K., and J. Stack. 2021. “Heritage Connector: A Machine Learning Framework for Building Linked Open Data from Museum Collections.” Applied AI Letters 2 (2): e23. doi:10.1002/ail2.23.

- Foti, P. 2018. Collecting and Exhibiting Computer-Based Technology: Expert Curation at the Museums of the Smithsonian Institution. London, UK: Routledge.

- Foulston, M., and K. Volsing. 2018. Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt. London, UK: V & A Publishing.

- Fouseki, K., and K. Vacharopoulou. 2013. “Digital Museum Collections and Social Media: Ethical Considerations of Ownership and Use.” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 11 (1) Art. 5, doi:10.5334/jcms.1021209.

- Freire, N. 2020. “Innovating Metadata Aggregation in Europeana via Linked Data”. Europeana Pro. Accessed 5 Feb 2022. https://pro.europeana.eu/post/innovating-metadata-aggregation-in-europeana-via-linked-data.

- Geismar, H. 2018. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London, UK: UCL Press.

- Giannakoulopoulos, A., M. Pergantis, S. M. Poulimenou, and I. Deliyannis. 2021. “Good Practices for Web-Based Cultural Heritage Information Management for Europeana.” Information 12 (5): 179. doi:10.3390/info12050179.

- Giannini, T., and J. P. Bowen. 2022. “Computational Culture: Transforming Archives Practice and Education for a Post-Covid World.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, doi:10.1145/3493342.

- Holmes, K. 2006. “Experiential Learning or Exploitation? Volunteering for Work Experience in the UK Museums Sector.” Museum Management and Curatorship 21 (3): 240–253. doi:10.1080/09647770600502103.

- Innocenti, P. 2014. “Bridging the Gap in Digital Art Preservation: Interdisciplinary Reflections on Authenticity, Longevity and Potential Collaborations.” In Preserving Complex Digital Objects, edited by Janet Delve, and David Anderson, 71–84. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

- Johnson, M. R., and J. Woodcock. 2019. “The Impacts of Live Streaming and Twitch.tv on the Video Game Industry.” Media, Culture & Society 41 (5): 670–688. doi:10.1177/0163443718818363.

- Kirschenbaum, M. 2008. Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kizhner, I., M. Terras, M. Rumyantsev, V. Khokhlova, E. Demeshkova, I. Rudov, and J. Afanasieva. 2021. “Digital Cultural Colonialism: Measuring Bias in Aggregated Digitized Content Held in Google Arts and Culture.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36 (3): 607–640. doi:10.1093/llc/fqaa055.

- Lee, J., H. Cho, V. Fox, and A. Perti. 2013. “User-Centred Approach in Creating a Metadata Schema for Video Games and Interactive Media.” Proceedings of the 13th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on digital libraries, Indianapolis. Indiana, USA, July 22–26.

- Lee, J. H., R. I. Clarke, and A. Perti. 2015. “Empirical Evaluation of Metadata for Video Games and Interactive Media.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66 (12): 2609–2625. doi:10.1002/asi.23357.

- Liddell, F. 2021. “Building Shared Guardianship Through Blockchain Technology and Digital Museum Objects.” Museum and Society 19 (2): 220–236. doi:10.29311/mas.v19i2.3495.

- Newman, J. 2012. Best Before: Videogames, Supersession and Obsolescence. New York: Routledge.

- Orngreen, R., and K. Levinsen. 2017. “Workshops as a Research Methodology.” Electronic Journal of e-Learning 15 (1): 70–81.

- Owens, T. 2018. The Theory and Craft of Digital Preservation: An Introduction. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Park, J. 2021. “An Actor-Network Perspective on Collections Documentation and Data Practices at Museums.” Museum and Society 19 (2): 237–251. doi:10.29311/mas.v19i2.3455.

- Park, J., and A. Samms. 2019. “The Materiality of the Immaterial: Collecting Digital Objects at the Victoria and Albert Museum.” In Proceedings of the MW19: Museums and the Web. Accessed 5 Feb 2022 https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/the-materiality-of-the-immaterial-collecting-digital-objects-at-the-victoria-and-albert-museum/. Boston, USA, April 2–6.

- Parry, Ross. 2010. Museums in a Digital Age. London, UK: Routledge.

- Pavlidis, G. 2019. “Recommender Systems, Cultural Heritage Applications, and the Way Forward.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 35: 183–196. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2018.06.003.

- Pennington, D., and L. Spiteri. 2019. Social Tagging in a Linked Data Environment. London, UK: Facet Publishing.

- Price, K. 2019. “Redesigning the V&A’s Collections Online.” Accessed 5 Feb 2022 https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/digital/redesigning-the-vas-collections-online, V&A Blog.

- Rees, A. J. 2021. “Collecting Online Memetic Cultures: How Tho.” Museum and Society 19 (2): 199–219. doi:10.29311/mas.v19i2.3445.

- Ridge, M. 2014. Crowdsourcing Our Cultural Heritage. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

- Skinner, J. 2014. “Metadata in Archival and Cultural Heritage Settings: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Library Metadata 14 (1): 52–68. doi:10.1080/19386389.2014.891892.

- Srinivasan, R., R. Boast, J. Furner, and K. M. Becvar. 2009. “Digital Museums and Diverse Cultural Knowledges: Moving Past the Traditional Catalog.” The Information Society 25 (4): 265–278. doi:10.1080/01972240903028714.

- Stimler, N., L. Rawlinson, and A. Lih. 2019. “Where Are the Edit and Upload Buttons? Dynamic Futures for Museum Collections Online” In Proceedings of the MW19: Museums and the Web. Accessed 5 Feb 2022 https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/where-are-the-edit-and-upload-buttons-dynamic-futures-for-museum-collections-online/. Boston, USA, April 2–6.

- Topaz, C. M., B. Klingenberg, D. Turek, B. Heggeseth, P. E. Harris, J. C. Blackwood, C. O. Chavoya, S. Nelson, and K. M. Murphy. 2019. “Diversity of Artists in Major U.S. Museums.” PLOS ONE 14 (3): e0212852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212852.

- Trant, J. 2009. “Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework.” Journal of Digital Information 10 (1): 1–44. https://journals.tdl.org/jodi/index.php/jodi/article/view/269.

- Turner, H. 2015. “Decolonizing Ethnographic Documentation: A Critical History of the Early Museum Catalogs at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 53 (5–6): 658–676. doi:10.1080/01639374.2015.1010112.

- The Uncensored Library. n.d. https://www.uncensoredlibrary.com/en.

- Valeonti, F., A. Bikakis, M. Terras, C. Speed, A. Hudson-Smith, and K. Chalkias. 2021. “Crypto Collectibles, Museum Funding and OpenGLAM: Challenges, Opportunities and the Potential of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs).” Applied Sciences 11 (21): 9931. doi:10.3390/app11219931.

- Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A). 2019. Collections Development Policy. Accessed 5 February 2022. https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/reports-strategic-plans-and-policies. Collections Policies.

- Villaespesa, E., and S. Crider. 2021. “A Critical Comparison Analysis Between Human and Machine-Generated Tags for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Collection.” Journal of Documentation 77 (4): 946–964. doi:10.1108/JD-04-2020-0060.

- Villaespesa, E., and T. Navarrete. 2019. “Museum Collections on Wikipedia: Opening up to Open Data Initiatives” In Proceedings of the MW19: Museums and the Web. Accessed 5 Feb 2022 https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/museum-collections-on-wikipedia-opening-up-to-open-data-initiatives/. Boston, USA, April 2–6.