ABSTRACT

An exploration of conservation and curatorial practices surrounding Indigenous American heritage in European museums began with an American Academy in Rome Prize fellowship which served to reconnect three of the co-authors. The stunning discovery of seven Yup’ik masks from western Alaska at the Vatican Museums led two of the co-authors to connect with Chuna McIntyre, a Yup’ik artist and performer. In an effort to pilot a collaborative process where conservators and curators might have their technical and cultural understanding of these masks enhanced, a three-hour virtual meeting was arranged after the masks were documented and the images and information shared. The successes and challenges are presented here from various viewpoints.

Introduction

Italy and the Vatican are unlikely places for a scholar who studies the conservation of North American Indigenous materials to find herself. But knowing for a long time about the Ethnological Museum – now the Anima Mundi Museum – at the Vatican, and the Pigorini Museum – now part of the Museo dell Civiltá in Rome, was enough to tempt author Ellen Pearlstein (hereafter referred to in first person if I am writing) to apply for a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. I am interested in whether and how my European museum counterparts: conservators and curators, connect with the communities from whom these North American Indigenous collections derive.

In the United States it is unacceptable to interpret Indigenous materials without working with scholars, artists, and/or elders from the communities represented. The risk of unknowingly compromising tangible and intangible cultural attributes through uninformed display, handling, and conservation is real. How, then, are such communications initiated, achieved, and fostered when collections reside in Europe and source communities are in North America? When communication is enabled, what is the impact on the Indigenous materials’ wellbeing, and on the museum’s representation and care?

In order to tackle these complex questions, I devoted my six-month fellowship at the American Academy in Rome to working continuously with collections and colleagues at the Anima Mundi Museum. Visits to the Pigorini Museum, as well as travel to a total of eight museums with North American Indigenous collections in Florence, Milan, Paris, Vienna, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Berlin and Hamburg, formed a further basis for understanding. I occasionally encountered curators at European museums who are visual or cultural anthropologists, and whose work includes travel to the communities whose collections are held in their museums. In only one instance, outside of Italy, did this include travel to the community by the conservator who is responsible for care.

Yup’ik masks

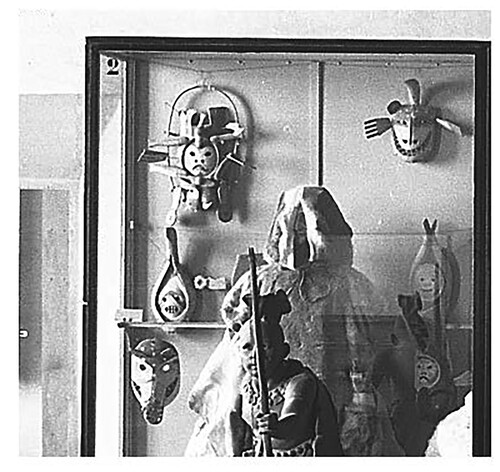

My work focused on seven Yup’ik masks collected no earlier than 1924 from a Jesuit Mission in Alaska (). Six of these masks appeared in the 1926 Vatican Missionary Exposition () at the Lateran Apostolic Palace Museum until 1963, after which they were moved to storage for 10 years, and then placed on display when the Ethnology Museum reopened in 1973 (Vatican Museums Citationn.d.). They were subsequently placed in storage in 2016 when the Ethnology Museum prepared for renovations. About the mission history in Alaska, anthropologists Mossolova and Michael report:

… religious conversion and an assimilating colonial agenda introduced in the area first by Russian Orthodox priests in the mid-1800s and then continued by Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the mid-1880s resulted in the disruption of many traditional cultural practices, dramatically altering [Yup’ik] Indigenous ceremonial and spiritual life. By the 1930s, the important Yup’ik ceremonies had been abandoned in most communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Masks and masked dances were condemned and abolished across the region. Recreational dancing with no masks involved survived in the communities missionised by Catholics, but along the Kuskokwim River where Moravian influence prevailed, even non-masked dance performances were completely suppressed until the first active attempts to revive mask making in the1980s. (Mossolova and Michael Citation2020, 668).

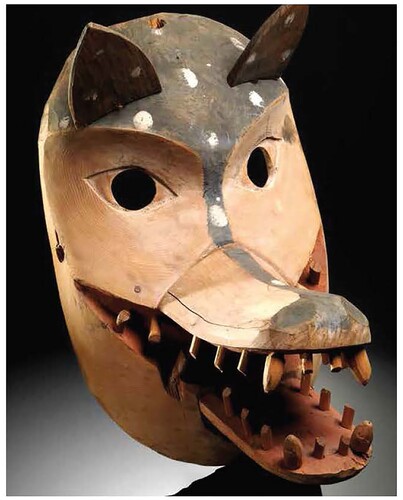

Figure 1. Yup'ik mask 101596. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 2. Yup'ik mask 101592. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

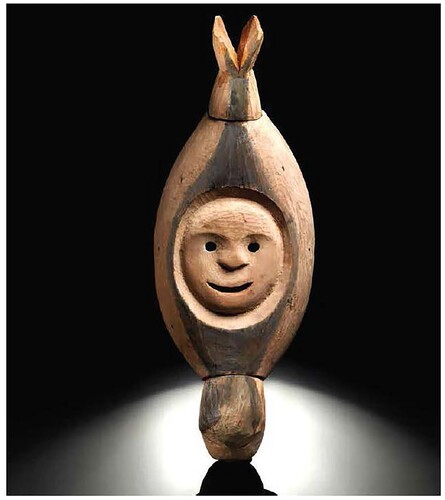

Figure 3. Yup'ik mask 101593. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 4. Yup'ik mask 101594. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 5. Yup'ik mask 101595. Note baleen extensions and tail feather above eyes with seal gut at tip. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 6. Yup'ik mask 104661. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 7. Yup'ik mask 101591. Anima Mundi, Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Figure 8. Detail of Yup'ik masks on display in 1960s image of the 1925 Vatican Missionary Exposition. Courtesy Vatican Museums archives. Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

The revival of mask making, according to co-author Yup’ik artist and cultural specialist Chuna McIntyre, took place because carvers never lost the ‘blueprint’ for converting dreams, visions and myths into carved creations. This could not have been accomplished without those museums that held onto historic collections, and those who are willing to share these holdings. In this case it is the Anima Mundi Museum, with the curator and director Father Nicola Mapelli, and the Conservation team under the direction of Stefania Pandozy, who came together to meet with Chuna McIntyre to share in understanding these historically collected masks. Acknowledgements also go to Nadia Fiussello, Assistant of the Ethnological Museum ‘Anima Mundi’, Vatican Museums, who provided access to archival information.

Anima Mundi Museum

Father Nicola Mapelli joined the Vatican Museums after completing his PhD and teaching, before which he completed missionary work in the Philippines (Anon Citation2022, Merate Online). To read the words of a journalist paraphrasing Mapelli about the newly installed museum helps us understand the new name Anima Mundi, and how the sprituality of Chuna McIntyre aligns with the museum’s goals:

“From disorientation to amazement, from curiosity to the desire to get to know distant cultures and traditions. It’s the emotional journey of those who visit the Vatican to admire the masterpieces of Raphael and Michelangelo, who then enter the new premises of the Ethnological Museum, now called Anima Mundi spirituality of the world [more accurately translated Soul of the World]. It is not just any other exhibit, but beckons to inclusiveness and dialogue. It’s a space in which to respectfully draw near to non ‘western’ aesthetic canons. Here art becomes pluralistic. It takes on an international, universal, catholic approach. It’s a museum whose center is the periphery’ (Vatican City News Citation2020–Citation21)

The museum Anima Mundi in the Vatican Museums, in close collaboration with the Restoration Laboratory, is the steward of a heritage of more than 80,000 works, representative of the cultures of peoples from all over the world. This is a priceless, tangible and intangible asset that must be treated with care, not simply because it is delicate, precious or ancient, but, above all, as a sign of respect for the cultures and peoples that produced it. The Restoration Laboratory has been for years involving scholars and laboratories from around the world that work to protect this type of heritage, connecting them and allowing them to discuss the issue of ethics in conservation in order to positively contribute to the diffusion of a new, more inclusive method that is attentive to the principle of valorising cultural diversity, with the prospect of promoting the ethical issue of the intercultural training of new generations of restorers. Through this close relationship with the world, a new critical consciousness was born in us and a commitment to reflect on the questions posed by the collections. We began to work together on the same items with more specialists in an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural approach intimately intertwined with communication.

We are infinitely grateful to Ellen Pearlstein for participating in our work over the course of five months from February to July this year. During this period of passionate and shared study, Ellen has made her knowledge available, sharing interesting and innovative conservation strategies by comparing those of the Anima Mundi with the conservation approaches of many restoration laboratories in Europe and America. Experiences and solutions accumulated through professional and human commitment to the conservation and protection of Indigenous heritage provide us with tools for a better look at the past of a people, but above all afford an opportunity for knowledge to live in harmony in the present and the future.

Our reflection stems from the awareness that today more than ever museums and restoration workshops themselves can play a key role in education as instruments of social cohesion. The museum represents a precious opportunity for cultures, where it is no longer a threat to the planet's communities and stops qualifying as a museum of ‘objects’ to become a museum ‘of and for the peoples’, bringing to completion that evolutionary process of art from being exclusive and elitist to richly inclusive. Restorers are part of these ongoing changes and are called upon to actively participate in them, in synergy with other professionals involved in heritage protection, for the development of a sustainable museology, able to leverage precisely the social responsibility of cultural operators. Fostering exchange and synergy between professions and specialisations, encouraging the reflection on conservation techniques and materials, the aim is to bring out a shared practice of conservation, capable of enhancing the exchange between cultures and the widest participation in the process of heritage protection and transmission. The Anima Mundi Laboratory has always dedicated particular attention to the study and learning of traditional techniques for the creation of collections, both in the preliminary stages of identifying the constituent materials, and in the subsequent stages of defining the correct conservation practices, from non-intervention to the use of indigenous restoration materials.

Ellen Pearlstein’s intentions

It is important to understand one’s own intentions in pursuing the work of facilitating consultation with an Indigenous artist. As a conservation researcher, practitioner and professor, my role involved thoroughly documenting the masks, setting up the meeting, and paying modestly for Chuna McIntyre‘s time with research funds. Chuna McIntyre has consulted about his culture for institutions including the Heard Museum in Phoenix, AZ, the Metropolitan Museum in NY, and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. I am grateful to colleagues, especially including Landis Smith, for facilitating my connection to Chuna McIntyre. Presently lacking within Italy is a rich network of colleagues in the U.S. who share and exchange about valued collaborative contacts. In facilitating this project, I aimed to ask questions about physical attributes of these masks that arose out of my examination, and about spiritual attributes as yet unidentified. I also knew that preparations are underway at the Anima Mundi Museum to exhibit their Americas materials within the next year, opening the opportunity for a deep, new interpretations of the masks. I am neither Yup’ik, nor a staff member of the Vatican Museums, and my own research objectives were to demonstrate the impact of knowledge sharing based on documentation and web conferencing about items far away from home.

I write this paper with the co-authorship support of my Vatican colleague and our Yup’ik colleague to be sure to present the most significant learning from a nearly three-hour web-based meeting we all had with Chuna McIntyre about the seven Yup’ik masks in the Anima Mundi Museum, on June 7, 2022. By utilizing either first or third person voice, participants shared new knowledge and responses to this participatory approach.

As a professor I hold appointments in UCLA Information Studies and the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. My research frequently includes material analysis designed to answer questions of cultural importance to Indigenous communities (Gleeson et al. Citation2012; O'Hern, Pearlstein, and Gagliardi Citation2016; Pearlstein Citation2015, Citation2018, Citation2020; Pearlstein and Keene Citation2010; Pearlstein and Potter Citation2021). I contend that we as conservators have the expertise to answer material questions, but these studies only contribute to a more fully realized understanding when mediated through those with greater cultural understanding. For example, a centrally important area of my teaching is providing co-instruction with Indigenous basketry experts about the context of and care for baskets held by Indigenous museums (Pearlstein Citation2008).

Pre-consultation with McIntyre

Before my arrival in Rome, in October 2021, I did a collections search on the Vatican’s Collective Access open database (Vatican Museums Online Database Citationn.d.), using the search terms Americas and Indigenous. More than twenty items appeared, among them a Yup’ik mask, MV.101596.0.0, cataloged as Yup’ik and described as a ‘Maschera rituale amanguak’ (Vatican Museums Online Database Citationn.d. M. V. 101596.0.0). Through this record, and Katherine Aigner and Nicola Mapelli’s The Americas. Collections from the Vatican Ethnological Museum, I learned of additional Yup’ik masks in the Vatican collections (Aigner and Mapelli Citation2015). Only a partial inventory of the Anima Mundi collections is available online to the public (Vatican Museums Online Database Citationn.d.). My Vatican colleagues generously located and retrieved from storage each of the Yup’ik masks to the temporary in-gallery conservation space in the Anima Mundi. They also graciously provided tools such as a dedicated work surface, lighting and a portable digital microscope.

I examined each mask closely, and I produced documentation before the masks were discussed with Chuna McIntyre, a Yup’ik expert. The possibility for him to review the masks, or the documentation, or both, was considered, though permissions to share materials had not yet been secured at the outset of my examination. I knew of Chuna McIntyre’s extraordinary knowledge and interest in Yup’ik materials held in museums, and his record of sharing knowledge with multiple museums. In keeping with what is typical for conservation documentation, these records incorporating text and images that I created were initially shared only with the museum curator and conservators.

I was aware that Yup’ik masks are often referred to as made from driftwood, most often of spruce (Hellmann et al. Citation2012), and that they frequently include numerous appended elements, often attached with wooden dowels. Typical handling and climate variation can loosen these appendages, and they can be found detached or repositioned (Metropolitan Museum Citation2019).

In looking for publications about Yup’ik materials, I sought out the means to find or borrow Anne Fienup-Riordan’s research about Yup’ik masks, and especially her groundbreaking work of bringing Yup’ik elders to the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin in the mid-1990s (Fienup-Riordan Citation1996, Citation2007). It was impossible without my own university VPN to access any of these publications here in Rome.Footnote1 While working to promote a deeper understanding in Italy and the Vatican of Indigenous collections from the Americas I wondered about the role played by a lack of available library sources in contributing to an already large knowledge gap. Parenthetically, through many conversations with museum anthropologists in Italy I heard about the difficulties of studying American Indian anthropology or visual culture. In a country overwhelmed with cultural heritage, priorities for education lie elsewhere.

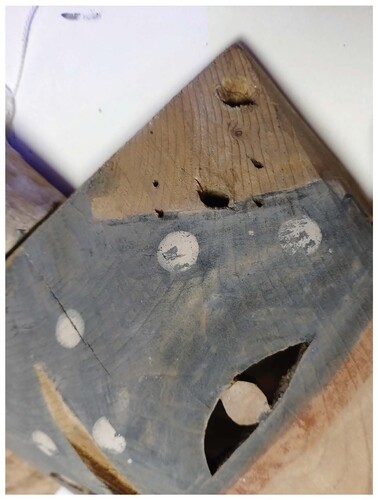

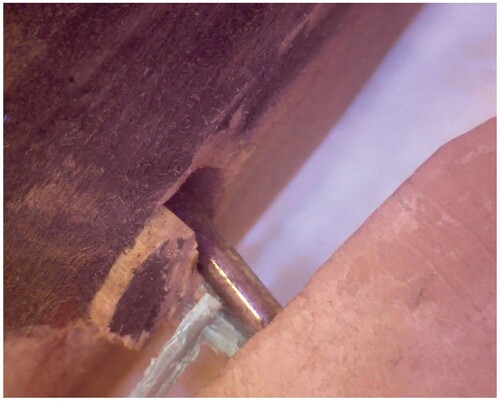

Across a number of weeks I examined the seven Yup’ik masks in the temporary visible conservation laboratory within the entrance to the Anima Mundi galleries. My close examination led to the documentation of tool marks where visible. I documented a number of vacant manufactured holes throughout the masks – many circular in section and frequently found on the mask edges, but others square shaped and apparently made with a square awl (), as well as a series of circular tool marks, or impressions, in the bentwood hoop surrounding one mask (Figure 11). Access to a digital microscope allowed me to examine the small, mechanically produced holes in many of the masks to look for evidence of what they formerly held. My prior awareness of Yup’ik masks with feather extensions had me expecting to see the tips of feather calami, the hollow sections of the feather shaft that support its growth from under the bird’s skin. However in the case of these masks I identified paired grass stems in multiple holes in a number of them. Other noteworthy additions include a section of gut tied to a projecting feather on one mask (was this a fragment of something larger?) (Figure 14), and strips of baleen (or keratinous sieve plates from the mouths of whales) () projecting from holes in another mask. Many appendages are attached with metallic hardware including nails and wires, which appeared to be either original and paint covered or possibly added later as they were devoid of paint. Earlier wood dowels had in some cases been replaced with metal pins (), and adhesive attachments securing some elements appear to be a later modification of unknown date.

Figure 9. Detail of awl marks on Yup'ik mask 101593 made before red paint was applied. Photo credit Ellen Pearlstein.

I increasingly felt that we should perform a video consultation with Chuna McIntyre, so that we could hear about his own impressions of these Yup’ik masks in preparation for their planned exhibition, and so that he could assist us in understanding which of our questions are important to cultural representation, and which other things we had overlooked. After our initial conversation, Chuna expressed to me that a video consultation would not leave enough time, given the generations of Yup’ik knowledge that are presented by each mask. He felt that an in-person meeting would be preferable. While I felt this way too, such visits require substantial lead time to arrange at the Vatican Museums, and there was no funding to pay for Chuna’s expenses. We thought about a future in-person visit (now planned for November 2022) but meanwhile the video meeting was confirmed.

Meeting with Chuna McIntyre

The meeting with Chuna was enchanting, full of poetry and deep knowledge. Our meeting was animated, rich, and rewarding. He started off with giving thanks in his language, offering thanks for the wonderful work of his ancestors, remarkably including the seven masks at the Anima Mundi. He referenced the world lived in by his grandmother’s people and he reminded us that there is a thirty century-long history of his people who used masks for supplication, to ensure survival. Chuna attended our meeting in a cloth traditional garment – though it would have been skin or gut originally – made by the drummer in his dance troop who is his linguist colleague (Figure 16).

Chuna first taught us the Yup’ik word for mask, Kegginaquq. The prepared documentation had inspired his own reflections, and he noted the use of the description ‘Maschera rituale amanguak’ for the MV101596, noting in particular the word amanguak (Amaguguaq), which is a mask which is half beluga, half walrus, as the walrus is the beluga whale’s consort (, 101596). The beluga is the wolf of the sea, so that on this mask the whale tale joins a wolf face. The whale appears like a gentle creature, but when they reach the land they turn into wolves. Chuna ‘s grandmother told him this story. The center face on this mask is a seal, the mother of all sea creatures. He noted that having all of these fish on this mask provided visual clues to those attending the mask’s ceremony. Domes attached to the sides of two fish carvings may represent medicine sometimes found secured to the sides of some fish. The stylized flower-like elements are the feet of the wolf, and the others are the flippers of the seal, and Chuna suspects that there were two more feet for the wolf, and also more flippers on the mask.

We turned next to my questions about appendages that were present in 1960s images of the 1924-5 exhibition (see for example ) but relocated now, and what this tells us about their positioning and methods of attachment. Mis-arranged parts on masks have been observed by Chuna, and he has rearranged them, and sometimes they remain lost or missing. About the now missing evidence of paired plant stems in four locations on mask MV101596, Chuna thought this may be seagrass, which would be an important inclusion of the plant kingdom on a mask that largely references animals. In the case of plant extensions, they would not have had feather plumes at their tips.Footnote2 An important and elegant point made by this mask is that we are all in this together, the whale, the wolf, the seal, the fish, the grass.

Chuna described the hoop encircling the mask, known in Yup’ik as ella, as ‘the very air I am breathing, the consciousness I possess, the earth we stand on, the air we breath.’ The hoop has gravity, the seal is peering at us through her universe. A center hole on the hoop probably held a feather. He showed us a Nunavak mask with a hoop surrounded by feathers in his own collection. It is impossible to be human and not respond to the beauty and poetry embedded in this mask!

In response to my questions about tool marks, Chuna thought that a hand axe was likely used for this mask (). Similarly, he identified the repeating circular tool marks on the ella, the hoop surrounding the animal faces on this same mask as the teeth marks of the artist, caused when he went to bend the wood strip (). This was incredibly exciting to me, to realize that this kind of close evidence of the maker is extant!

Figure 10. Back of Yup'ik mask 101596 () showing awl marks and bite block. Photo Vatican Museums, Images and Rights Department © Governorate of the Vatican City State - Directorate of the Vatican Museums.

Chuna did not think metal wires or nails were surprising, or compromising, because there is ‘an ancient blueprint’ that all Yup’ik follow even as they incorporate new materials and methods. This is an important lesson for me to learn as a conservator, and I will return to this. He described the meaning of the colors as follows: red is blood of the ancestral mother, in honor of all of the Yup’ik mothers, traditionally red iron oxideFootnote3; white and blue are traditionally clay, and black is traditionally soot mixed with seal oil or human blood. I am aware of only one pigment study for Yup’ik masks, however their color palette is restricted (Geier Citation2006).

Chuna turned next to 101592 (), and he provided the name Agyalek (star-studded) kegluneq (wolf) and told us it means wolf among the stars! This mask probably had a hoop, ella or ellanguaq. But the evidence is that the hoop was partial. He says an open hoop (ella or ellanguaq) is like leading a wake while traveling through space. A celestial wolf among the stars, but not a particular constellation. Wolves were considered to have human, Yup’ik, qualities, or Yukcagaraat. The wood block on the back is for holding the mask by biting. Many of the masks have them (see ), and while this is not always the case for precontact masks, those masks excavated and reported upon at Nunalleq do not have bite blocks (Mossolova Citation2020, 23).

We learned next that the shape of 101593 is Unan, a spiritual hand with no thumb, or the four fingered hand that cannot grab ()! Chuna further explained that spiritual hands only have four fingers, because hands without thumbs cannot grab, and Yup’ik people did this in their own interest, because as humans we do not wish to be grabbed! Yup’iks have a trinity: life, negativity, and goodness. When our time comes, the goodness is channeled back to all people, the evil dissipates as the firmament cleanses, and the Yup’ik spirits join their ancestors enveloped by light. Swans are present as guardians for this transition. The central figure is a land animal with two forearms, and there are holes on the edges so additional appendages are missing. Chuna believes that there were feather stars, possibly attached within the small original holes above the face which my examination revealed were made before the mask was painted (). The missing feathers were likely the winter long tail feathers of the male duck Clangula hyemalis, with white plumes tied on at the ends, traditionally snowy owl or swan or goose. Now craft (likely chicken) white down is used. The mask is a classic spiritual hand!

The mask 101594 has a duck head, a spirit face and spiritual hands (). Chuna said this is a Kep’alek, or Greater scaup duck (Aythya marila), because of the long flat beak. The central vertical groove is like veins going through our body, another poetic reference to all of humanity. White spots are stars in the night sky. We discussed the holes I observed above the ears, and the absence of one ear (). Chuna believes as we do that there were two ears. The nostrils can also serve as the eyes of another spirit. Sometimes wood pieces were found with wormholes in it, but I do not think any of the carefully placed small holes were produced this way. We also discussed the repairs to replace the wooden dowels connecting the spirit hands, which I observed were cut off, a metal wire inserted in the join holes, and the cut edge of the dowel was then painted with the surrounding area, including the metal wire (). Chuna inquired about whether there are records of repair, which have not been identified in this case. In looking at trimmed or broken dowels at the chin, he thought that the feet of the duck should be there. He showed us a mask by Harry Shavings from Nunivak, with webbed duck feet. Chuna showed us other beautiful masks where motion caused the appendages to quiver in response to movement, an affecting sight!

Figure 12. Detail of unused holes in the location of the proper left missing ear of mask 101594 (). Photo credit Ellen Pearlstein.

Figure 13. Metal rod replacing sawn off wood dowel observed on proper left side appendage on 101594 (). Photo credit Ellen Pearlstein.

Also representing a very specific bird, Chuna referred to 101595 as the Qecervak, or Glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus), because of the beak with the hook at the tip (). This mask has baleen, which he reported was traded down from up north, was therefore a rare commodity, and that this baleen was used to attach many now missing feet, wings, and tail. The feather is from the male duck. Chuna showed us an example of that feather – long and tapered. It is a long-tailed duck, Clangula hyemalis, that produces a single tail feather. Tied at the tip of the feather is winter dried seal gut, being used because it is white and like a star, and like white feather down, is the night sky (). The color is more important than the material. With no bite block, this mask would have been tied onto the face. The central face is a combination of an aerial view of a bird, and the sea louse, indicated by the shape of the mouth. The sea louse is a crustacean that is a parasite for fish, and it is not eaten. The gull and eyes are like a bird in a bird. The entire face is also a conical head spirit!

Figure 14. Winter tanned gut attached to the tip of a feather secured to Yup'ik mask 101595 (). Photo credit Ellen Pearlstein.

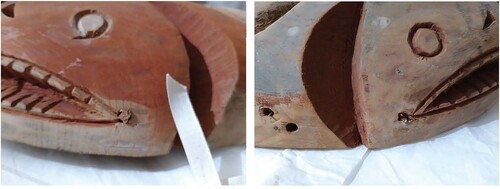

Chuna referred to 104661 as the Culugpauk, or Grayling mask, a kind of fish with the large fin (Thymallus thymallus) (). My examination revealed that on both sides in the corners of the grayling’s mouth, there are traces of wood and baleen attachments (). There might have been front flippers – Chuna showed us how front flippers are different from the back flippers. The central figure is a seal, with a back flipper on the upper proper left. The upper proper right appendage is a seashell. Father Mapelli asked why is the mouth upside down? Chuna replied that it’s related to the story of the moon. Frowning is somehow connected to the moon. Like many of the masks, there are many empty holes on the sides; we don’t know what was there. Within the museum, the flipper was on the lower proper left in an earlier exhibit (). Chuna thinks there were hands and back flippers on the mask, now missing. There is plant and wood materials inside some of the holes around the perimeter; and there are two baleen extensions now only visible on the interior. Returning to seashells, they are eaten, and the mask may represent the request for ample seashells. The spots on the proper right of the fish indicate that the night sky – the mask creature is traveling through the night sky.

Figure 15. Details of the proper left and right mouth sides of Yup'ik mask 104661 (see ), showing remains of inserted materials. Photo credit Ellen Pearlstein.

We learned finally that 101591 () is the Angllulria (diving) maklak (bearded seal), diving great bearded seal, diving into the depths of the sea! It has the sun emblem on the back. He’s taking the sun along into the sea. The face is human too, the nose adds that feature. The mask was made in three pieces, it has a bite block as others do. Yup’ik masks in three pieces would not be adhered, they would have been doweled, adhesive was not used. There are many empty holes on the sides where appendages are missing. The mask could have had flippers or hands, it is unclear. The tail may also be read as a conical spirit.

In response to my questions about how the public is to understand a mask that is missing appendages, Chuna said he has never seen a museum label saying that the appendages are missing. He has repaired masks, added feathers and appendages, for the Thaw collection in upstate NY. He says that the masks have had a life, they have lost appendages as part of that life.

Chuna told us emphatically that the masks need to hear the Yup’ik language when he comes to Rome in November 2022! He reiterated that many of the masks come from dreams, from a myth, or from a vision; you go to the good carver and ask them to produce your dream. Shamans will go to good carvers. Not everyone is a good carver. He told us that anyone can wear a mask – not just shamans. When the ceremonies were done, masks were placed in bonfires, or brought out to the tundra to be placed by a lake. Masks were only saved when outsiders came and were interested in them.

Stefania Pandozy and the Conservation Lab’s response to the meeting

Ellen Pearlstein has promoted and led a study project on seven Yup’ik ritual masks preserved in the Ethnological Museum, Anima Mundi of the Vatican Museums, a study that found its strong point in a long virtual conversation with Chuna McIntyre, master storyteller, dancer, artist and extraordinary bearer of Arctic culture and spirit. Chuna is from the village of Eek, in south-western Alaska, on the coast of the Bering Sea. He grew up with the precious teachings of his grandmother, from whom he learnt the dances, songs and stories of his ancestors. He founded and runs Nunamfca (‘of our land’) Yup'ik Eskimo Dancers to enable natives and non-natives alike to experience Yup'ik culture.

This extraordinary encounter provided us with fundamental answers to many questions necessary for the correct interpretation, conservation and display of the masks (). The constitution of the works in the tangible sense, materials such as the use of wood from the Bering coast, carving techniques with local axes, [traditionally] natural pigments: the blood red of the ancestral mother, red iron oxide; white and blue traditionally clay, black soot mixed with seal oil or human blood.

Chuna taught us the multiple iconographies of the subjects represented: the whale, a gentle creature until it reaches dry land where it transforms into a wolf; the seal, mother of all sea creatures in their tradition; the fish and their symbolic values intertwined as in the Amanguak, a mask half beluga and half walrus, since the walrus is the consort of the Beluga whale. He explained that at the end of the celebrations, the masks were destroyed in bonfires.

Above all, the intangible value of these precious masks that come from dreams, from a vision, reinforced in us the awareness of how crucial it is for the future of conservation to have the participation of indigenous communities in conservation projects, oriented towards the transmission of heritage to future generations. Involving community representatives to learn their techniques, to listen to their views and suggestions, are therefore as crucial in the elaboration of conservation choices as in the definition of exhibition criteria. It is precisely from confrontation that not only the most suitable solution will emerge, but also and above all a mutual enrichment.

The dialogue on the value and use of ritual masks of the Yup’ik peoples with Master Chuna, conveyed to us the profound wisdom of the worldview in harmony. A multi-layered reading, where the art world of nature coexists in harmony with the living spirit of surviving oral traditions. We are increasingly committed to passing on our tangible and intangible cultural heritage to future generations by ensuring that they are as accessible as we are and respecting the social and spiritual value of the objects.

Father Nicola Mapelli’s response to the meeting with Chuna McIntyre

I interviewed Father Mapelli to capture his own responses. My first question was whether hearing from Chuna McIntyre changed the way that you see the Yup'ik masks?

‘That really changed, because you could feel that it was not something from out of a book, it was something from his own being, inside, his spirituality. Those masks were part of his blood. It was very beautiful.’

As a curator do you feel a responsibility to present the masks any differently than before?

Before [in his tenure] they were not on exhibit. The deep meaning of the masks was important to learn for the current planned exhibit where they will all be placed on display. It will be very important to hear Chuna’s response to the masks when he comes to the museum in November. Hopefully the installation will be finished.

That is what we usually do. We started this in 2010, visiting Aboriginal Australians communities in Australia and continued with Indigenous communities all over the world. For North America, I remember our meetings with Lakota Sioux communities in South Dakota and with Native communities in the USA Southwest, just to mention a couple of examples. I was fortunate to travel to Alaska in 2014, visiting Inuit and Yup’ik communities, and spoke with people about these masks … We want to connect as much as possible with the people who made the items.

Thank you very much Ellen. It would be much better for us to be there in the flesh for this conversation, but with the Covid situation, this is the best we could do. Even with the digital circumstances, we could feel each other’s passion, and I think he could feel our responsibility and even love for our collections, that we want to treat them with respect, and that’s why we contacted him.

Now travel has become difficult. In my experience it is difficult to get people on the computer. I had to travel to the forest of Papua New Guinea, to the Andes, to meet people who are usually very old people. Only a small percentage will be able to work on the computer. No travel has been possible for us this year, let’s hope next year.

‘Chuna has written the label for the Yup’ik masks. It’s a privilege to have his contribution. For us it’s very important to give voice to the local people’.

At the current time there is no video footage in the Anima Mundi galleries. Father Mapelli discussed how it may be possible to include this in the near future.

Conclusion

Chuna McIntyre made the point that there are layers and layers of meanings within the masks, as there are in life. He has learned to look and think in layers, and to isolate, and yet to also interconnect the parts. While my close and considered inspection of these masks as a conservator brought together many ideas to interconnect, my observations came alive through this meeting with Chuna! The poetry and performativity surrounding these masks for those who have the ‘blueprint’, i.e., the Yup’ik knowledge to understand their myriad meanings, is completely moving. Chuna’s philosophical understanding of how these masks loose (and gain!) appendages is also a good lesson for conservators, who respect artist’s intent by privileging the original appearance of a work. While I felt awe in learning what probably had been present on these masks – and why, and some genuine concern about misrepresentation that might ensue if they are exhibited without text clarifying missing appendages, Chuna’s confident ability to complete the mythical events coupled with his calm acceptance of the effects of time were reassuring.

The vicissitudes of time differences (nine hours between the Vatican and Chuna’s home) and web access were definitely stressful for this conservator. I admit that I met with American Academy IT staffFootnote4 to make sure that my phone had enough data to support the hotspot for a close to three-hour meeting, and I obsessed over the multi authentication required for me to use my university Zoom account, which required a second charged mobile phone. I insisted on performing a test the week prior. I faced my own need to have a well-planned meeting – especially being sensitive to the hardship created by very late hours for Chuna resulting from the time difference – with the flexibility of responding to technological gaps.Footnote5 The temporary conservation lab where items are accessed is in a gallery and is subject to the noise from workers and museum visitors. In hindsight, as we relied on the PowerPoint documentation images to share the masks, we could have held the meeting in the quiet office offered by Stefania Pandozy. Hindsight is 20:20. Despite these stressors, our meeting went splendidly and the outcomes and learning far outweighed the vicissitudes of setup!

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ellen Pearlstein

Ellen Pearlstein was the Senior Objects Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, where she also served as an advisor on NAGPRA. She is a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles in the UCLA/Getty Program in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, UCLA Cultural Materials Conservation, and UCLA's Department of Information Studies. As a member of the founding conservation faculty in 2005, she began designing and teaching graduate classes in the conservation of organic materials, ethics of working with Indigenous communities, preventive conservation and managing collections. Her publications include Conservation of Featherwork from Central and South America, and she is currently completing a book Getty Readings in Conservation: Conservation and Stewardship of Indigenous Collections: Changes and Transformations. Ellen is a Fellow in the American Institute for Conservation and the International Institute for Conservation, a 2022 recipient of an American Academy in Rome Fellowship, a winner of the Keck award, and President of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in Conservation.

Chuna McIntyre

Chuna McIntyre is a master artist, storyteller, and dancer who performs traditional Yup'ik dance and song accompanied by percussion on a hand drum. Born in the village of Eek on the coast of the Behring Sea, McIntyre was raised there by his grandmother from whom he learned the dances, songs, and stories of his ancestors. He later founded and directed the renowned Nunamta (“of our land”) Yup'ik Eskimo Singers and Dancers troupe, which have traveled the world to allow Natives and non-Natives to experience Yup'ik culture. Chuna dances in his native costume and uses authentic artifacts and masks to illustrate the customs and stories of this ancient southwest Alaskan tribe. Chuna has also consulted with various museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Sheldon Jackson Museum, about their Yup'ik items.

Stefania Pandozy

Stefania Pandozy is the Head of the Poly-material conservation Laboratory of the indigenous collections of the Anima Mundi Museum of the Vatican Museums. She graduated in history of modern art in 1984 and specialized in art history and restoration in 1987. Since then she has collaborated with numerous important public and private institutions as a restorer, and since 1997 she has been tenured at the Ethnological Museum of the Vatican Museums. In 2001 she received the position of Coordinator of the Project of Conservation and Restoration of the Collections of the Missionary Ethnological Museum of the Vatican Museums and in 2009, of Head of the Restoration Laboratory of the Polimaterico. She organized at the Vatican Museums the conferences “Sharing Conservation I: Plurality of Approaches to Conservation 2011”, “Sharing Conservation II: Earth 2012”, “Sharing Conservation III: The Social Value of Conservation 2014” for the development of research initiatives in collaboration with restoration laboratories, museums and international institutions dedicated to the protection of indigenous collections. Always in search of new perspectives, thanks to synergistic work with museum curators and the collaboration of scholars and colleagues, she has chosen to confront the terrain of restoration experiences and conservation approaches by proposing a debate on the ethics of conservation in the contemporary world, with a view to being able to keep open and open to discussion, and to be able to contribute to the cross-cultural training of young and future generations of restorers. All of the work in the Vatican's indigenous collection connects people to their heritage and history while also involving their communities of origin in the conservation choices to be made. What is particularly significant about this work is the ongoing process of reconnecting these cultural forms to their communities of origin, thus creating spaces for an intergenerational dialogue about the cultural connections and traditions of all the peoples of the earth.

Notes

1 I searched Worldcat.org to locate Italian libraries whose works are available by interlibrary loan to fellows at the American Academy in Rome. No holdings could be found, though the ICCROM Library holds four articles about the conservation of Yup’ik materials.

2 While these are not present on the Anima Mundi masks, white feather plumes (where the vane tip is left on an otherwise stripped shaft) are referred to as stars. Typically these stars face the four cardinal directions. Chuna showed us a mask with these ‘stars’ and with facial features twisting, with its mate, which was made for him by his father.

3 Ann Fienup-Riordan reports that many Yup’ik elders describe uiteraq/red ocher as colored by the menstrual blood of Raven's daughter. Personal communication, Feb 12, 2023.

4 Thank you Simone Lorio, IT Administrator, Area Comunicazione e Informatica srl

5 There is no wifi access at the Vatican Museum and the wired desktop computers in the conservation space lack cameras and microphones. Further, Chuna McIntyre’s location is nine hours earlier than Central European Time in Rome. Fortunately, Chuna is a night owl and did not mind receiving a call at midnight for him, from me at 9am the next day at the Vatican! It is ironic that we connected so late, as Chuna would spend late nights with his grandmother, who taught him a great deal about his culture. I used data from my Italian mobile phone to create a hot spot for my own computer, allowing me to use my university’s Pro Zoom account to conduct our meeting. We also succeeded in inviting a Vatican iPad with wifi privileges to the meeting, so we could show Chuna both my prepared documentation and the masks. I felt tremendous relief when we established our connections!

References

- Aigner, Katherine, and Nicola Mapelli. 2015. The Americas. Collections from the Vatican Ethnological Museum. Vatican City: Edizioni Musei Vaticani.

- Anon. 2022. Father Nicola Mapelli from Sartiran on a Mission in the Philippines is Well, Merate Online, https://www.merateonline.it/articolo.php?idd = 34904, accessed July 13, 2022.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1996. The Living Tradition of Yup'ik Masks. Seattle: U Washington Press.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 2007. Yup'ik Elders at the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin: Fieldwork Turned on its Head. Seattle: U Washington Press.

- Frink, N. 2016. A Tale of Three Villages: Indigenous Colonial Interactions in Southwestern Alaska 1740–1950. Tucson: Univ of Arizona Press.

- Geier, Katharina. 2006. “A Technical Study of Arctic Pigments and Paint on Two 19th-Centuryyup'ik Masks.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 45 (1): 17–30. DOI: 10.1179/019713606806082193.

- Gleeson, M., E. Pearlstein, B. Marshall, and R. Riedler. 2012. “California Featherwork: Considerations for Examination and Preservation.” Museum Anthropology 35 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1379.2012.01126.x.

- Hellmann, L., W. Tegel, Ó Eggertsson, F. H. Schweingruber, R. Blanchette, A. Kirdyanov, H. Gärtner, and U. Büntgen. 2012. On the importance of anatomical classification in Arctic driftwood research, TRACE Tree Rings in Archaeology, Climatology and Ecology, Volume 11, Proceedings of the DENDROSYMPOSIUM 2012, May 8th – 12th, 2012 in Potsdam and Eberswalde, Germany, edited by Gerhard Helle, Holger Gärtner, Wolfgang Beck, Ingo Heinrich, Karl-Uwe Heußner, Alexander Müller and Tanja Sanders, Scientific Technical Report STR13/05.

- Jesuit Archives and Research Center, Digital Collections and Resources. https://jesuitarchives.omeka.net/about, accessed September 1, 2022.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, Conserving a Yup'ik Mask. February 2019. Caitlin Mahony and Chuna McIntyre, https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/videos/2019/4/yupik-mask-conservation, accessed September 1, 2022.

- Mossolova, Anna. 2020. Mending the breaks: Revival and Recovery in Southwest Alaska Mask-Making Tradition, PhD dissertation, School of Humanities, Tallinn University, Estonia.

- Mossolova, Anna, and Drew Michael. 2020. “Yup’ik Masks in the Precontact Past and the Contested Present.” World Archaeology 52 (5): 667–684. doi:10.1080/00438243.2021.1993989.

- O'Hern, R., E. Pearlstein, and S. Gagliardi. 2016. “Beyond the Surface: Where Cultural Contexts and Scientific Analyses Meet in the Conservation of Komo Helmet Masks in Museum Collections.” Museum Anthropology 39 (1), 70–86. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111muan.12102.

- Pandozy, Stefania AA.VV. 2011. Sharing Conservation, Several approaches to the conservation of art made with different materials, Workshop Reports 2011, Edizioni Musei Vaticani Vatican City 2012.

- Pandozy, Stefania AA.VV. 2014. Sharing Conservation 2, Several Approaches to the Conservation and Restoration of Art Made with Different Materials, Earth. Vatican City: Edizioni Musei Vaticani.

- Pandozy, Stefania AA.VV., and Mathilde De Bonis. 2017. Ethics and Practice of Conservation, Manual for the Conservation of Ethnographic and Multi-Material Assets. Vatican City: Vatican Museums Editions.

- Pandozy, Stefania AA.VV. 2019. Experiences of the Polimaterico Laboratory 4, Knowing Preserving Sharing. Vatican City: Editions Vatican Museums.

- Pearlstein, E. 2008. Collaborative Conservation Education: The UCLA/Getty Program and the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum, Publication of Proceedings of Symposium 2007: Preserving Aboriginal Heritage – Technical and Traditional Approaches. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute.

- Pearlstein, E. 2015. “Restoring Provenance to an American Indian Feathered Blanket.” In Preserving our Heritage: Perspectives from Antiquity to the Digital Age, edited by Michele Valerie Cloonan, 555–565. Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman.

- Pearlstein, Ellen. 2020. “George Wharton James and the Appropriation of Indigenous Basketry.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 44 (1): 53–72. https://meridian.allenpress.com/aicrj/article/44/1/53/462821/Basketmaking-Guides-and-the-Appropriation-of.

- Pearlstein, Ellen. 2018. Sharing voices in the conservation of featherwork. In Book commemorating the South American featherwork workshop held in 2018 at the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, edited by Friederike Berlekamp. Basseler Archives Publications, in preparation.

- Pearlstein, E., and L. Keene. 2010. “Evaluating Color and Fading for Flicker Feathers; Technical and Cultural Considerations.” Studies in Conservation 55 (10): 1–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27867121.

- Pearlstein, Ellen, and Bryn Potter. 2021. Identifying intrusive, non-Indigenous basketry in museum collections, Museum Management and Curatorship, 2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.108009647775.2021.1873828.

- Vatican Museums. n.d. https://m.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani-mobile/en/collezioni/reparti/reparto-raccolte-etnologiche.html.

- Vatican News. http://www.vaticannews.cn/en/vatican-city/news/2021-12/ethnological-museum-anima-mundi-australia-oceania-indonesia.html, accessed July 13, 2022.

- Vatican Museums Online Database. n.d. https://m.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani-mobile/en/collezioni/catalogo-online.html, accessed October 22, 2021.

- Vatican Museums Online Database. n.d. M. V. 101596.0.0, https://catalogo.museivaticani.va/index.php/Detail/objects/MV.101596.0.0.