ABSTRACT

This paper assesses the design and use of protection orders for domestic violence in England and Wales. It draws on data from 400 police classified domestic violence incidents and 65 interviews with victims/survivors, as well as new analysis of government justice data from England and Wales, to address a gap in literature on protection orders.

The paper identifies an increasing civil-criminal ‘hybridisation’ of protection orders in England and Wales, and argues that a dual regime has developed, with orders issued by police and/or in criminal proceedings increasingly privileged (and enforced) over victim-led civil orders. Whilst protection orders are being used – as intended – flexibly to protect domestic violence victims, the way they are applied in practice risks downgrading domestic violence in criminal justice terms.

The conclusions are especially timely in light of current Government proposals to rationalise protection orders by introducing a single overarching Domestic Abuse Protection Order in England and Wales.

Introduction

In England and Wales, civil orders to protect victims of domestic violence have been in use since 1976. There are six main behavioural protection orders for interpersonal and family violence currently in use in England and Wales: restraining orders (RO), non-molestation orders (NMO), occupation orders (OO), Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPO), Forced Marriage Protection Orders (FMPO) and Female Genital Mutilation Protection Orders (FGMPO). These orders are explained in more detail in the sections which follow. This paper focuses on ROs, NMOs and DVPOs, as the key orders for domestic violence. OOs have been in steady decline since 2003 and have, to some extent, been replaced by DVPOs: these orders, and related questions concerned with occupancy and residency in the marital home, are not examined in detail in this paper. Whilst ROs, NMOs and DVPOs are all preventative orders, requiring or prohibiting certain behaviours of the person they address, a key difference is whether they are issued as part of criminal or civil proceedings, which governs the circumstances in which they can be issued, and therefore who can apply for them, grant them and how they may be enforced.

Over the past two decades there has been a shift in emphasis in the design of protection orders – from being purely civil law measures, towards orders being increasingly issued as part of criminal proceedings, and by criminal justice agents (police officers). Over time, this has resulted in a proliferation of different protection orders, and in the ‘hybridisation’ of criminal and civil measures to protect victims from domestic abuse. There is a gap in the academic and policy review literature for an assessment of the consequences of this shift – an assessment which is particularly timely now, since the Government has made proposals to introduce a new, overarching protection order for domestic abuse. Domestic Abuse Protection Orders are included in the Domestic Abuse Bill introduced on 16 July 2019. The Government intends these new orders to replace DVPN/DVPOs immediately, and NMOs and ROs in domestic abuse cases over time (Home Office Citation2019).

Background

The design of existing protection orders

Restraining orders

Restraining orders (ROs), issued under section 5 of the Protection from Harassment Act (PHA) 1997, are civil orders granted by a judge in criminal proceedings following a conviction (or acquittal) on a criminal charge. Thus, whilst the standard of evidence for issuing an RO is civil, they can only be made where a criminal charge has been brought. Victims themselves do not apply for orders, nor do they need to consent to one being made.

ROs prevent domestic violence, stalking and harassment by prohibiting contact, prohibiting violence, intimidation and harassment, and banning the offender from certain places. They usually last between six and 12 months but can be made for an indefinite period and are renewable. Breach is a criminal offence with a power of arrest, and can be heard in either Magistrates or Crown courts. Prior to 2009, ROs were only issued (under PHA 1997) on conviction for harassment offences. In 2009 (bringing in provisions made in the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004), ROs were extended to allow judges to issue them on conviction for any offence (not only harassment), and on acquittal for some offences. The Government argued that this extension was necessary because there were cases in which there had been ‘clear evidence’ during proceedings that a victim needed protection, but insufficient evidence to convict (Hansard (HL) col GC, 2 February 2004). Early evaluations of this widening of circumstances in which ROs could be issued suggested that professionals saw the extension of ROs as the measure in the 2004 Act which would potentially have the biggest impact on victim safety (Hester et al. Citation2008).

Non-molestation orders

Non-molestation orders (NMOs), issued under Part IV of the Family Law Act 1996, are applied for by the victim in civil proceedings (with or without a solicitor). The standard of evidence for issuing an NMO is civil, and victims can decide to apply for an order themselves – there is no requirement for criminal charge or proceedings (Ashworth and Zedner Citation2014, Rights of Women Citation2015). As with ROs, they aim to prevent domestic violence, stalking and harassment by preventing the offender from contacting the victim and/or attending certain places. In 2007 they were extended to cover a wider range of parties (relatives and those in same-sex couples as well as heterosexual intimate partners), and breach of an order was criminalised, with an automatic power of arrest. Their duration is variable but usually under one year; this is extendable on application by the applicant.

Domestic violence protection orders

Domestic Violence Protection Notices (DVPN) and Orders (DVPO) were introduced in the Crime and Security Act 2010, and brought into force nationally in 2014. They were intended as an additional protection measure, granted by the police on-the-spot to offer immediate protection to victims in the aftermath of a domestic violence incident, whilst other avenues – which might include criminal charges, civil orders, or victim support – were investigated. This new measure filled a gap identified by the police and taken up by government (Kelly et al. Citation2013). DVPN and DVPOs are issued by the police on the basis of the police determining that there are reasonable grounds to believe the suspect has been violent or has threatened violence towards an associated person, and that the order is necessary to protect that person from violence or threat of violence – thus the victim does not have to consent or apply themselves (College of Policing Citation2015). The DVPN has immediate effect, lasts 48 hours, and prohibits the perpetrator from molesting the victim; it may also evict them from premises or restrict their ability to enter those premises. Police then have to apply to a magistrates’ court for a DVPO, which lasts for 28 days. Thus, this order is effectively an emergency non-molestation and eviction notice (like an occupation order), with the distinction that it is the police who decide to apply it, it has immediate effect, and limited duration. The DVPO has a power of arrest attached, so police can arrest for breach – but breach is a civil contempt of court. Government guidance is clear that DVPOs should not be seen as an alternative to criminal charge – however, they are envisaged in circumstances where an arrest and charge is not immediately possible: ‘where no other enforceable restrictions can be placed upon the perpetrator’ (Home Office Citation2016, section 2.4). Police are required, in their application for a DVPO, to justify why the prevention of further violence cannot be achieved by other means, e.g. bail conditions, and strongly encouraged in police guidance to avoid using them in high risk cases or in cases where a criminal charge can be brought (College of Policing Citation2015).

New proposals: domestic abuse protection orders

The Government is proposing, via the Domestic Abuse Bill currently before Parliament, to rationalise the existing protection order regime by introducing a new Domestic Abuse Protection Notice (DAPN) and Order (DAPO). These will replicate DVPOs by giving victims immediate protection following an incident, and being issued by police. However, they will address perceived shortcomings in the current orders, namely their limited duration (28 days) and the fact that breach is not a criminal offence. The Government proposes that DAPOs will offer more comprehensive and flexible protection because it will be possible for a wider range of applicants (victims, police, relevant third parties) to apply for the order in different courts (civil, criminal). Courts will be able to make an order of their own volition, to determine the appropriate duration, and to vary the conditions. It will be possible to make positive requirements (e.g. to attend a perpetrator programme) as well as prohibitions, and to electronically monitor perpetrator compliance. Breach will be a criminal offence, with a maximum sentence of five years, though it can also be dealt with as contempt of court. At present these proposals are only in draft form but, if the Bill is adopted, they have the potential to significantly change the landscape of protection orders: the Home Office envisages that they will become the ‘go-to’ protection order for domestic abuse, with 55,000 issued each year (Home Office Citation2019).

A shift towards criminalisation

Since the 1990s there has been increasing criminalisation of domestic violence, echoing a shift from its perception as a ‘private’ matter between applicant and respondent, to a ‘public’ matter, in which the police are automatically expected to play a role (Hester Citation2006, Burton Citation2010). There has been a parallel shift towards blurring the boundaries of criminal and civil law remedies and the development of hybrid civil-criminal remedies. Hitchings (Citation2005) identifies this trend as starting with criminalisation of breach of the civil ASBO order in 1998. This ‘hybridisation’ is particularly obvious in protection orders for domestic violence, with the criminalisation (via the 2004 Domestic Violence, Crimes and Victims Act, coming into force in Citation2007) of breach of civil NMOs (Hester et al. Citation2008). The same pattern has been adopted with subsequent civil protection orders for forced marriage (Forced Marriage Protection Order, FMPO), which were brought in in 2007, but breach of such an order was only criminalised in 2014; and female genital mutilation (Female Genital Mutilation Protection Order, FGMPO), breach of which was criminalised from introduction in 2015. The criminalisation of breach in the design of orders is significant, since it shifts the enforcement of non-compliance with an order from the victim (via the civil courts) to the police, and means that if the abuser breaks any of the conditions of the order they can be arrested without any need to return to court, whilst still leaving an option for the victim to apply for a warrant of arrest or committal order in the family court if the police do not pursue a charge.

Criminalisation of breach of civil orders is not without controversy. During the passage of the 2004 Act there was considerable parliamentary debate about the possible introduction by the back door of a (lesser) civil burden of proof in criminal processes, by criminalising breach. There are other concerns, too, about hybridisation; for instance, that availability of quasi-criminal measures may deter the police from pursuing substantive criminal charges. There is some evidence that police are already using short-term summary tools at their disposal to ‘manage’ domestic violence – such as arrest and release without action, or breach of the peace – particularly where a couple remain together or the victim is ‘non-cooperative’ (Hester, Citation2006; Westmarland et al. Citation2018). On the other hand, victims may be less likely to apply for orders such as NMOs because they fear criminalising their partners and/or not having the choice themselves. Victims’ advocates have argued that civil law empowers victims by giving them choice in how and when they can access protection, and conversely, that police and courts issuing orders without the need for victim consent may mark the dis-empowerment of victims, by criminalising their partners when police enforce breach – even if this was not what the victim wanted (Barron Citation1990, Hitchings Citation2005).

So we find a picture in England and Wales, in 2020, where a multiplicity of protection orders exist for domestic violence. Some (e.g. occupation orders) are fully civil, meaning the victim must apply in civil court proceedings for an order (and for a power of arrest to be attached). Unless the court has attached a power of arrest, the victim must return to the court to demonstrate breach and apply for a warrant of arrest or an order for committal. Others (e.g. restraining orders) are issued by the courts in criminal proceedings following a charge and trial (whether the defendant is convicted or acquitted), and any breach is automatically criminal and enforceable by police. Many, though, straddle a hybrid continuum in-between, being part civil and part criminal – this applies to NMOs, FMPOs and FGMPOs, all of which are orders made in civil proceedings but where breach is a criminal offence, therefore enforceable by the police; and DVPOs, which are police-issued and where breach is a criminal offence.

Influences on the use of different orders

There is a discernible gap in the literature of work which assesses how the overall design and use of different protection orders in England and Wales have changed over the past decade or so. This is especially important in light of significant cuts to legal aid from April 2013, when changes in the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 came into force, meaning that applicants for legal aid had to meet more stringent financial eligibility criteria; and of cuts to police resourcing from 2010 to 2017, with the number of police officers having fallen from 146,411 in March 2010 to 125,820 in March 2017 (Home Office Citation2019). Whilst there are articles and inspection reports which review or evaluate specific orders (Hester et al. Citation2008, Platt Citation2008, Kelly et al. Citation2013, HMICFRS, Citation2017), there are few which assess the overall coherence of the protection order regime, especially looking across civil and criminal processes. Moreover, articles which do address the overarching picture tend to be either non-recent (Burton Citation2010, Edwards Citation2001, Citation2006, Hitchings Citation2005), or outside the English and Welsh context (Capshaw and McNeece Citation2000, Burgess-Proctor Citation2003, Douglas Citation2008, Van der Aa Citation2012).

Several studies in England and Wales between 2008 and 2010 suggested an initial downturn in use of NMOs following the criminalisation of breach (Hester et al. Citation2008, Platt Citation2008, Burton Citation2010). Platt found a 15-30% decrease in applications for the orders across six county courts in the six months following implementation, and judges across the country reported an ‘immediate and sharp drop in the number of applications’ (Platt Citation2008, p. 643). Hester et al. (Citation2008) found a 10% fall in applications for NMOs, and 20% fall in NMOs made in the year following implementation. Hester et al. and Platt both recognise that their analyses were based on initial data from a period of less than one year after the changes, and emphasise that those data were too short-term to draw conclusions about trends. Burton (Citation2010) was commissioned by the Legal Services Commission (LSC) to examine possible reasons for a decline in the number of applicants for funding to pursue civil law remedies for domestic violence. She found a similar picture, with LSC certificates for funding dropping in the year post 2007 implementation of the changes to NMOs. All these papers point to a range of reasons including confusion amongst police, judges, solicitors and victims’ agencies in adjusting to the new regime, lack of availability of legal aid, but principally suggest it may reflect a reluctance of victims to criminalise their partners (Platt Citation2008, Hester et al. Citation2008, Burton Citation2010).

Further concerns were raised about the effects on access to NMOs of cuts to legal aid introduced in the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO), which came into force in April 2013. Although there was a continuing exemption for applicants for domestic abuse and forced marriage injunctions, the Act made it harder for all applicants to qualify financially for legal aid, by ending the practice of uprating the gross income means-test in line with inflation, introducing a more stringent capital means test, and increasing financial contributions required from those who did qualify (Law Society of England and Wales Citation2017). Domestic abuse campaigners expressed fears that these changes meant that ‘women affected by violence with very low incomes are often required to make unaffordable contributions towards their legal aid’ (Rights of Women Citation2018).

At the same time, there was criticism from other quarters that, since a NMO was now an accepted form of evidence to prove domestic abuse to qualify for legal aid in family law cases, this might invite exploitation, with solicitors applying for orders on the basis of false allegations of abuse in order to win legal aid for their clients in family proceedings (Mason Citation2016). More neutrally, legal commentators predicted a rise in applications for NMOs as a result of LASPO, as people who had good grounds for an order might be more likely to apply for one in order to get legal aid evidence, when previously they might have chosen not to apply for an order (Hunter Citation2011).

A 2017 police inspectorate report found that ‘many forces are still not using DVPOs as widely as they could, and opportunities to use them continue to be missed’ (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017, p. 25). Police inspections identified several reasons for their underuse, including: officer inexperience in using them (in some forces the application process sat with specialist domestic violence teams so other officers were not aware of them), a lack of officer training on how to use them, orders being seen as too bureaucratic or the paperwork being too time-consuming (especially when building a case for charge in parallel), and varying force policies, including only using DVPOs in high-risk cases (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) Citation2014; HMIC, Citation2015; Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017).

Breach and enforcement

The effectiveness of a protection order relies on the threat of consequences for breach (Douglas Citation2008). The police are best placed to monitor compliance with the conditions of protection orders, for instance by means of electronic monitoring, keeping contact with the victim, or patrolling the area from which the perpetrator is banned (Logar and Niemi Citation2017). But international research has found multiple problems with police enforcement of protection orders (Burgess-Proctor, Citation2003). In studies in Canada and the US, police officers were more likely to arrest for breach if there were signs of a struggle and/or physical violence (Chaudhuri and Daly Citation1992, Rigakos Citation1997). This is reflected in the Sentencing Guidelines for England and Wales for breach of protection orders, which privileges physical violence (Sentencing Council Citation2018). In terms of charges brought for breach, an Australian study of 645 court files of prosecutions for breach of domestic violence orders in Queensland, found that many of the matters charged as breaches of protection orders could have been charged as criminal offences, including assault or criminal damage, offences which would have carried higher penalties than the breach offence (Douglas Citation2008). It concluded that breach charges often failed to reflect the seriousness of the offence, and that breaches were prosecuted where it was difficult to satisfy the burden of proof in relation to a more serious criminal offence. In some cases, Douglas noted, these decisions may have reflected the non-cooperation of victims in pursuing criminal charges. However, she also found that penalties were often inappropriate and very low for breach – often lower-order fines. One critical finding was that defendants in breach prosecutions were less likely to plead guilty than for other offences: 59% compared with 74% in all criminal cases. However, the same proportion were found guilty of breach offences as for all criminal cases (Douglas Citation2008). This provides compelling evidence that domestic violence perpetrators charged with lower-level breach offences rather than criminal offences for an incident are more likely to contest the charge, and to receive lower order sentences.

Domestic abuse practitioners and victims surveyed by the police inspectorate in England and Wales reported dismay at the lack of action taken for breach of civil orders and bail conditions, in particular of DVPOs (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) Citation2015; Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017). The inspectorate found examples of victims reporting multiple breaches to police before any action was taken, which they said had had a detrimental effect on their confidence in the police, and delays in responding to breach. In some cases, officers waited for the perpetrator to return on bail at a later date to deal with the breach (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017). Practitioners interviewed reported that breaches were not always recorded by the police. As a result, the inspectorate concluded, ‘breaches are not always reaching court and these measures are at risk of becoming a “toothless instrument”’ (HMIC Citation2015, p. 59).

Police can only act on breach of a protective order if they know it exists. As well as police needing to know what actions would constitute a breach of an order to be practically able to enforce it, there is a more fundamental point. For an order to be valid, there is a formal requirement that the subject it addresses must be aware that it exists. This means an order has to be formally served on the respondent, and the police need then to be notified of the order and that it has been formally served on the respondent before they can act: ‘proof of service means that orders can be enforced’ (Family Justice Council Citation2011, p. 2).

This does not seem to be happening systematically. A consequence of reductions in legal aid and an increase in litigants in person has meant that this step is being missed out – victims or their solicitors are not always notifying the police that an order has been made, and/or there is no formal statement made to the police that the order has been properly served (Domestic Abuse Matters Citation2014). There seems to be a further problem with police routinely not recording the existence of orders in a timely manner. For instance, an investigation into handling of NMOs in one force found delays in recording orders on police systems which left the victim unprotected; and front office staff unsure what to do with an order when a process server provided a copy of the order (Domestic Abuse Matters Citation2014).

Steps have been taken at the police and courts levels to address this issue. For instance, one police force has developed a detailed protocol setting out how the courts will communicate orders made with the force (via email to a central address) and who will enter the details on the force systems (Sussex Police Partnership Citation2016). In 2018, then President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, issued a new Practice Direction 36 H which came into force in July 2018 for a twelve-month pilot. Under this scheme, the courts communicated orders made with a central police email address, which in turn communicated to forces (Practice Direction 36 H – Pilot Scheme, Procedure for Service of Certain Protection Orders on the Police, Citation2018). At the time of writing this scheme had recently ended and lessons for practice were under review.

Methods

This paper draws on data from three sources. Firstly, new analysis of data reported by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) on the use of ROs and NMOs over time. Data were collected from official statistics and publications, in particular: the annual CPS Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) reports (containing MoJ data on ROs issued, MoJ and CPS data on prosecutions for breaches of ROs and NMOS, and MoJ data on convictions for breach of ROs), MoJ Family Court Statistics Quarterly (courts data on NMOs issued), and reports of the police inspectorate for England and Wales, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS; previously HMIC) (data on police-issued DVPOs and DVPNs).

Secondly, analysis of police data collected as part of a wider research project [Justice, Inequality and Gender-Based Violence project, PI: Marianne Hester, ESRC Grant Number ES/M010090/1] involving 400 police-flagged domestic violence incidents reported to two English forces between May and November 2014, and tracked to criminal justice outcome. This dataset was explored for information on ROs, NMOs and DVPN/DVPOs, to see if quantitative analysis could be conducted. Eight out of 400 cases positively recorded a protection order associated with the case. Key variables in these cases were examined in Excel including case summary, victim and perpetrator demographics, prior and subsequent incidents, risk assessment, criminal charge and conviction and the nature of the orders.

Thirdly, a sub-group analysis was conducted of 251 interviews conducted between 2016 and 2018 with victim-survivors of gender-based violence for the same research project. All interviewees were asked about their experiences of different forms of gender-based violence (e.g. domestic violence, rape, forced marriage, FGM), and their use of criminal and civil justice systems. They were asked whether they had used a range of protection orders for domestic violence issued by civil or criminal courts, and about their views on using such orders. In total 65 interviewees said they had had one or more protection orders. Interviews did not tend to contain detailed information about the application and issuing of orders, since these questions formed only part of a wider-ranging interview, but victim-survivors did talk about the context in which orders were made, whether and how the orders were effective, and experiences of breach. These 65 interviews were coded and thematically analysed in NVivo.

Findings and discussion

Analysis of police cases and victim interviews for the project, combined with new secondary analysis of MoJ and CPS data, shows that the main protection orders for domestic violence are ROs and NMOs, which continue to be in demand in England and Wales. By design, protection orders for domestic violence are becoming increasingly hybrid, with most civil orders now containing an automatic power of arrest for breach, and thus criminal and civil options being more closely woven together. Yet in parallel, the enforcement of orders issued in criminal and civil proceedings are diverging, with some evidence that ROs are being privileged over NMOs in terms of criminal justice enforcement. This is having an effect of downgrading the criminal severity with which some domestic violence incidents are being treated – in keeping with a wider tendency for the CJS to downgrade DV as identified by Westmarland et al. (Citation2018).

Restraining orders issued in criminal proceedings

Restraining orders are frequently issued in cases charged with non-harassment and stalking offences

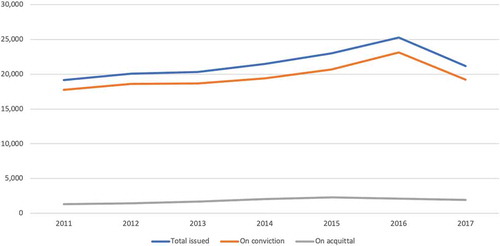

shows a steady increase in the number of restraining orders issued in criminal proceedings, since 2011, although there was a downturn in the last year for which data are available (a drop of 16% from 2016 to 2017). shows that ROs are being issued in proceedings for a wide range of criminal offences, on both conviction and acquittal. Although these orders were introduced as a remedy for ‘course of conduct’ harassment and stalking offences under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, they are increasingly being handed down as part of sentencing for non-harassment and stalking offences. In 2017, 60% were issued on conviction for other offences (and as many as 70% in 2016). Five cases in our project police dataset were issued an RO as part of sentencing on conviction, all of them for non-harassment and stalking offences: three for common assault, one for burglary, and one for criminal damage and assault. Our victim/survivor interviews show a similar picture, of ROs being used in sentencing for non-harassment and stalking offences. One interviewee told us that her partner received an RO alongside an eight week suspended sentence and a fine on conviction for assault by battery. Another said that her partner was convicted for ABH, criminal damage and threats to kill, and was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment (of which he served one), and a five-year RO. A third said that her partner was convicted for assault and battery and sentenced to a two-year RO and 40 hours unpaid community service. A fourth reported that her partner was sentenced to 18 months in prison on conviction, and a three-year RO, which he immediately broke.

Table 1. Restraining orders (ROs) and Non-Molestation Orders (NMOs) issued 2011 to 2017 (Ministry of Justice data)a.

Whilst most ROs are being issued in domestic violence cases, many seem to be handed down in criminal trials where a conviction for domestic violence offences of harassment or stalking either was not sought, or was not successful. This is of course in keeping with the intention that ROs should be protective – especially since the extension of scope in 2009 to allow judges to use them to manage domestic violence offenders – and it is positive that they are being used flexibly. However, it does also highlight ongoing problems with the ‘fit’ of the criminal justice system for domestic violence on two grounds: (a) it suggests that in domestic violence cases, bringing charges for ‘incident’ offences such as assault and criminal damage may still be being favoured over ‘pattern’ or ‘course of conduct’ offences such as harassment and stalking; and (b) in these convictions for ‘incident’ offences, judges are sufficiently concerned about the ongoing threat of further abuse to issue protection orders – suggesting that the violence was not a one-off incident.

Breaches of ROs are being enforced, but instead of charging substantive offences?

Ministry of Justice data show that breaches of ROs prosecuted as a calculated proportion of the number of ROs issued increased from 28% in 2011 to 48% in 2017 (). Convictions for breach of RO have increased in tandem, from a calculated proportion of number of ROs issued of 25% in 2011 to 43% in 2017 (). In 2017, 91% of defendants prosecuted for breach were convicted.Footnote1 The Crown Prosecution Service observes that this increase in prosecutions for breach of RO coincides with a fall in prosecutions for harassment offences in 2017–18 compared with 2016–17 (CPS, Citation2018, p. A20). This pattern echoes previous studies which identified a police tendency to downgrade domestic abuse-related charges to breach (e.g. Douglas Citation2008), or to downgrade DV in terms of the wider criminal justice system (Westmarland et al. Citation2018).

Table 2. Prosecutions and convictions for breach of Restraining Orders and Non-Molestation Orders, 2011–2017.

Civil-led non-molestation orders

Non-molestation orders remain in demand – despite criminalisation of breach in 2007 and changes to legal aid eligibility in 2013

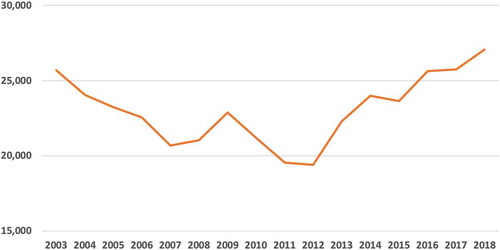

Ministry of Justice (MoJ) data present a contrary picture on NMOs to evaluations conducted in 2008 following the criminalisation of breach (Platt Citation2008, Hester et al. Citation2008), which suggested there had been a downturn in use. Some domestic violence advocacy professionals, judiciary and courts staff interviewed by Hester et al. at that time expressed concern that fewer victims might pursue NMOs because of concerns about criminalising their partners. It is positive that this has turned out not to be the case. The Ministry of Justice data show an overall increase in non-molestation orders since 2007, reversing the downward trend up to that point ( and ).

This suggests that concerns that more NMO applications would be contested once breach was made a criminal offence (Hitchings Citation2005, Burton Citation2010) have proved unfounded. It may be that the initial drop in NMOs following criminalisation of breach in 2007 reflected teething difficulties with implementation. A wider lens is helpful here. Edwards (Citation2001) shows that NMOs increased to 1993, then declined to 1997 when the Protection from Harassment Act was introduced. There was then a drop to 2000, an increase to 2002, and then a 15% decrease to 2006. This context, plus the new data presented here, suggests that the initial fall identified by studies in 2008 may have captured the tail end of the previous dip, coupled with initial disruption of changes to a new regime, rather than a longer-term decline in NMOs.

It also shows that concerns that changes to legal aid financial eligibility which came in in 2013 did not lead to an overall downturn in orders made for non-molestation. In fact, NMOs issued went up by 8% during the year following the changes (2013 to 2014) and have remained steady with a small upward trend since (see ). The data also does not support the alternative proposition regarding the effect of the LASPO Act: there was no dramatic rise in NMO applications or orders made following the changes in 2013, but rather a continuation of a modest upward trend with some annual fluctuations over time (). Survey evidence from 2014 found that 43% of women reporting domestic abuse could not ‘prove’ abuse. Where they did have proof, it was most commonly evidence from a healthcare professional, a MARAC or social services referral; only 10% reported having a civil order as evidence (Rights of Women, Women’s Aid and Welsh Women’s Aid Citation2014). This further suggests that the concern that changes to legal aid could lead to a spike in false allegations has not materialised. Whilst the overall number of NMOs granted has remained fairly steady over time, there is some evidence (reviewed below) of women continuing to face difficulties meeting the financial eligibility criteria for legal aid when applying for injunctions.

Civil NMOs are valued by victims. Some 26% of the victims/survivors interviewed for the project reported having one or more protection orders, most commonly an NMO (15%, n = 33). One victim/survivor reported that the threat of police enforcement of an NMO alone was effective in reducing abuse:

Well he did breach [the NMO]. He did carry on ringing me and harassing me and that. But then when he got warned by the police, I’ve not heard nothing since. [case 095]

Another said that the presence of an order was effective by creating some ‘space’ for all involved:

I think it’s a really clear line in the sand … when they do break it, to take some action and get it taken seriously straight away […] And [the NMO] just gave us all a bit of space really. I think while they’re still in your head and talking to you, it’s really difficult to get a perspective on what’s happened to you. But once he wasn’t in my head and I didn’t get his opinion on everything, and I didn’t get to hear how ill he was and how upset he was and how sad he was and how dreadful everything was, I think my sense of perspective came back [case 082].

Some victims reported specific barriers to obtaining NMOs

Victim/survivor interviews for the project found some evidence of victims being prevented or discouraged from seeking NMOs for several reasons, including: solicitors’ advice that they might look ‘hostile in family proceedings, lack of evidence to ‘prove’ abuse, applications being downgraded to undertakings, and lack of affordability due to cuts in legal aid.

For instance, one was warned by her solicitor that it would look ‘hostile’ in a child contact -related hearing in the family court, despite her ex-partner having been convicted in criminal court for harassment and having police bail conditions not to contact her:

In the family court, my solicitor advised me not to [apply for an NMO] because it would make me look like I was hostile [case 049].

This plays into the wider issue of a mismatch in approaches to domestic violence between the family and criminal courts. Although steps have been taken to address this (e.g. Practice Direction 12J – Child Arrangements and Contact Orders: Domestic Abuse and Harm (Citation2017)), research published in 2018 still found conflicts between the approaches in family and criminal court, with the former not always taking domestic abuse into account even when a conviction for domestic violence existed (Women’s Aid and Queen Mary University of London Citation2018).

In terms of barriers, several of our interviewees reported difficulties ‘proving’ domestic abuse sufficiently for courts to grant an order. For example, in one case the judge was reluctant to grant an NMO because the abuse was not physical:

I got the non-mol, and then he had a chance to contest it, which he did, and he tried that, and he contested it. And I had a real fight on my hands to put it in place. In the end the judge downgraded it to an undertaking, so for the last half of the year it was changed into an undertaking because the judge said that because there wasn’t any evidence of him having badly beaten me up or anything like that … and this is the judge’s own words, he said you know abuse needs to be very bad for me to feel justified in keeping a non-mol in place if it’s been contested [case 029].

Another reported that she was not granted an NMO because she had not been to the police previously to report the abuse:

Basically we went in front of the judge and he said all this stuff about me in his witness statement calling me a drug addict, saying I had this crazy lifestyle, I was drinking a bottle and a half <of hard liquor> a day. And because I had no proof because I’d never been to the police before or anything like that, the non-molestation order wasn’t granted. And … it really really was awful. He said that … the judge said that don’t go within so many yards of her, make a personal agreement, it’s called an overtaking … undertaking even … so I got that. [case 064]

One victim reported that her application was downgraded to an undertaking because the judge suggested the perpetrator would find it harder to contest:

the day of the fact-finding hearing the judge said to me, you know if my findings go against you, the non-molestation order will be discharged immediately. However, if your husband agrees to sign an undertaking now and we have that instead of the non-molestation order that will be binding regardless of what my findings are. And so I kind of felt that I had to do that really, so an undertaking was written [case 111].

Several reported that lack of legal aid was a prohibiting factor to gaining a NMO:

Legal Aid said that that wasn’t a persistent enough threat for me to qualify for Legal Aid to get a non-molestation order, so I couldn’t get one. [case 108]

I spoke to my solicitor about getting like basically an injunction against him to say he’s not allowed near my house because basically he won’t listen when I ask him not to call and text my phone. Actually the more I ask him not to do it the more he does it. I spoke to my solicitor about that but basically my solicitor said that I wouldn’t be able to obtain Legal Aid for it, so I’d have to pay for it and even if I paid for it there was no guarantee the court would go for it.

These examples show that, whilst overall, the number of NMOs granted do not seem to have fallen since the LASPO Act came into effect in 2013, individual women continue to have difficulties making their case for NMOs to be issued, in some cases due to difficulties meeting the financial eligibility criteria for legal aid.

Breach of NMO less likely to be acted upon than breach of RO?

At the same time as a rise in prosecutions for breach of RO, prosecutions for breaches of NMOs have remained broadly steady since 2011, with around a quarter of the number issued being prosecuted for breach each year. This may suggest that, as well as more ROs being issued overall, breach of ROs is more likely to be pursued by police compared with breach of NMOs. There was some support for this in our interviews. Several reported breach of an NMO to the police but were told (incorrectly) that the police did not have the power to enforce NMOs, and so could not act unless the perpetrator ‘did something direct’, with stalking and harassment behaviour seemingly not being deemed enough in itself:

He’s not meant to even come on my road, and even now he comes and parks right outside the house and everything. I’ve rung the police and they’ve said to me that I would need to take it back to court because they can’t really do anything because I’ve got the injunction and everything through the courts, not through the police. They said that because they’ve got no record of his behaviour, because they didn’t give me the injunction, that they can’t really do anything unless he’s a direct threat [case 029].

He still trails my oldest 16 year old walking down the road. The police know about it. The police care but they don’t care because they’re stuck. This court order (NMO) is a civil matter … Unless he does something direct, which I’ve been told so many times, “Unless he hits your daughter–then we can do something” [case 310].

In December he turned up at the children’s nativity play. The police were absolutely fantastic [but] it was deemed that it was going to be a breach of the peace but they didn’t have anything to arrest him [case 067].

Two of eight cases in our project dataset of police domestic violence incidents had NMOs in place at the time of the incident, but police took No Further Action on the breach. In one, despite the NMO and a history of 19 previous recorded domestic violence incidents between the partners, the police judged this incident of harassment not to be a crime, with no offences disclosed, and did not take action for breach of the NMO. In the other, the male perpetrator had a police record for domestic and sexual violence against previous partners. There was an NMO in place, and the police crimed the incident as harassment, but could not locate the perpetrator to take any action against him.

Both the victim/survivor interviews and police incidents provide further evidence of a divergence between police action to enforce breach of NMOs and breach of ROs, and suggest some confusion amongst police over their powers to enforce breach of NMOs. Hitchings (Citation2005) suggested there was a danger that ‘trivial’ breaches of non-molestation orders will not be top of the police’s priority list and therefore ‘criminalising breach of a non-molestation order may also have the (unintended) effect of not only failing to protect the victim, but of not achieving justice either’ (Hitchings Citation2005, p. 99). It seems this may be the case.

Poor police data is preventing enforcement of civil NMOs

As well as confusion amongst officers about their powers of enforcement for breach of civil NMOs, we uncovered evidence that some police forces in England and Wales do not have adequate records of protection orders – especially NMOs. In 307 out of 400 police DV incidents (77%) analysed for the project, it was not known whether or not a protection order was in place. Given that at least a quarter of victims/survivors we interviewed reported having one or more protection orders (26%), it is likely that police data is not capturing a swathe of cases where orders are in place. Forces do not seem to be systematically recording (especially civil) protection orders. This is worrying, considering that breach of many of these protection orders is criminal. If the police are not aware that orders are in place, how can they enforce them? These findings provide further empirical evidence of the problem of police recording of civil orders identified by campaigners and individual police forces, which the current pilot of Practice Direction 36H is intended to address (Domestic Abuse Matters Citation2014; Practice Direction 36H – Pilot Scheme, Procedure for Service of Certain Protection Orders on the Police, Citation2018).

Domestic violence protection orders

Use of DVPOs is hard to assess

It is perhaps too early to be able to assess the use of DVPOs over time, since they only came in in 2014, but far fewer seem to be issued than either NMOs or ROs: around 3,000 to 4,000 per year (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017). There is not yet a central reporting mechanism for data on these orders, so we are reliant on periodic police inspectorate reports which gather data direct from all the forces. Only 5% (n = 10) of the victims/survivors interviewed for the project reported having a DVPN/DVPO, and only two out of the 400 police incidents analysed for our project reported use of one (but they only came in in 2014, the year incidents were sampled). Police inspections have however found that ‘many forces are still not using DVPOs as widely as they could, and opportunities to use them continue to be missed’ (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017, p. 25).

DVPOs misused or not used

Police guidance is clear that DVPOs should not be seen as a preferred alternative to a criminal charge–rather, their use was envisaged in circumstances where an arrest and charge is not possible (College of Policing Citation2015). Yet in one of the two domestic violence incidents in our dataset in which a DVPO was issued, the police seemed to choose to use the order as an alternative to criming the incident and pursuing a criminal charge. This was a DV case involving a 17-year-old female victim and 20 year-old male partner. He physically assaulted her, and had a history of police call-outs for repeat domestic violence against her. The incident was not crimed; rather a DVPN was issued, followed by a DVPO [Police case 181].

We also found evidence of police using DVPOs for high risk cases (a problem flagged by HMIC in its latest domestic abuse inspection report, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017). The second case in our police dataset was a high risk DV case involving a 26 year-old female victim and 39 year old male partner. He assaulted her and was charged with ABH. He had a police record of physical violence, rape and sexual assault against her on at least four previous occasions. She was police-flagged as vulnerable, there were children involved and the perpetrator had police flags for drugs, alcohol, and mental health [Police case 292].

We found some evidence of women and children still being expected to leave the home after domestic abuse – rather than DVPN/Os being used to keep the perpetrator out, as they were intended. For example, one interviewee reported:

they said, well you’ve got an hour to get out of the house, because we’re about to go and release him on bail. I said no shouldn’t you stop him from coming to the house. I mean I subsequently found out that they should have issued him with a domestic violence protection … or us with a protection notice to stop him coming to the house, but they failed on that. … … I then had to get a non-molestation order … pay to get a non-molestation order and an occupation order to get back in the house [case 004].

Overall, it is hard to assess whether the current regime is enabling more women and children to remain in the family home because data on DVPN/Os remains so poor (Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) Citation2017).

Conclusions

In England and Wales, the last ten years has seen a shift in approach to protection orders for domestic violence: from victim-led civil measures towards increasing civil-criminal hybridisation, a greater emphasis on orders issued in criminal proceedings, and handing greater responsibility for decision-making and enforcement to the police. There has also been an expansion in the number and range of orders available. The Government’s newly-proposed DAPOs – hybrid criminal-civil orders which are intended to replace existing orders – are thus a natural continuation of this general trend in order design.

Greater availability and use of protection orders, including hybrids, may be a double-edged sword. On the positive side, protection orders which can be issued on-the-spot or in a wide range of criminal and non-criminal contexts are welcome on several grounds. They extend the ‘toolkit’ available to the police to manage perpetrators. They give the chance for police to act without being fully reliant on the victim for evidence, sometimes at a lower (civil) burden of proof ‘on the balance of probabilities’, which may be a better fit with the nature of domestic violence offending. They make a statement to victims and perpetrators that the offence is severe and compliance will be enforced (Gore Citation2007). Victims seem to welcome this (Hester et al. Citation2008). This paper finds that a greater range of orders are being used, more flexibly, to protect victims and manage perpetrators, and more breaches of ROs are being enforced.

At the same time, there is an increasing divergence between ROs issued in criminal proceedings and civil-issued NMOs. This paper presents fresh evidence that victims still want civil options, especially NMOs. Victims report barriers to obtaining NMOs for a range of reasons, including concerns about how they might ‘play out’ in family proceedings, lack of affordability due to legal aid cuts, and insufficient evidence to prove (especially physical) abuse. However, despite these individual barriers, and fears that criminalising breach (in 2007) and cuts to legal aid (in 2013) might significantly affect victims’ access to NMOs, Ministry of Justice data on the number of orders made suggests that, whilst there have been short-term fluctuations, NMOs continue to be made in sizeable, and steadily increasing, numbers.

Victims want civil-issued NMOs, then, but they also want the police to enforce breaches of those orders, which currently does not seem to be consistently the case. We found victims reported breaches of NMOs not being investigated or charged, with this picture underscored by confusion amongst police about their powers of arrest and enforcement when a civil NMO is breached, and a lack of systematic intelligence and data recording in police files to inform officers that civil orders are in place. This last point has been specifically identified as a problem in practice and attempts made to address it – for instance the Practice Direction 36 H issued by the then President Sir James Munby in July 2018, which proposed that the issuing court emails a central police address to notify them of the order; and protocols drawn up by individual police forces. Yet our evidence, from both victim reports and interrogation of police data, suggests that there is still a lack of systematic communication of these orders to the police. This is particularly problematic since if the police have no formal notice that an order has been served, they have no powers to enforce it. The Domestic Abuse Bill gives the Government an opportunity to address this vital gap in current procedures and practice and make sure that police are routinely notified by the courts that an order has been made and served. This is particularly important given the potential for increased confusion during implementation of the proposed new DAPOs.

In addition, whilst enforcement of breaches of ROs is to be welcomed, we are concerned that an increase in charges for breach may obscure a corresponding drop in charges for substantive offences – which attract higher penalties – being charged for DV (a conclusion supported by the CPS, Citation2017). Thus, a focus on breach may be having the inadvertent effect of downgrading domestic violence in criminal justice terms. This is supported by victims interviewed by Hester et al. (Citation2008) who suggested that perpetrators were more likely to go to court for breach rather than alternative substantive criminal charges (e.g. assault), and by international evidence on the downgrading of criminal charges to breach charges in domestic violence cases (Douglas Citation2008).

Overall, it seems that a dual regime of protection orders has developed, with orders issued in criminal proceedings and by police privileged (and enforced) over victim-led civil orders, and the greater use of protection orders having an unintended consequence of downgrading domestic violence in criminal justice terms. In this context the Government’s proposal to introduce a new, comprehensive Domestic Abuse Prevention Order in England and Wales, is very welcome: it is an opportunity to simplify and co-ordinate what has become a crowded field, and in particular to make sure that courts are joined up. However, there is a danger that rationalisation of existing orders risks just shuffling the deckchairs. Breaches, often multiple breaches, of protection orders are common, and police can be slow to respond or not take action at all – particularly with NMOs. This risks loss of victim confidence, potentially leading to under-reporting of breach. The right range of orders must exist, but must also be enforced.

So, whilst the Government’s proposals for rationalising the current regime under a single, new, flexible Domestic Abuse Protection Order are a welcome simplification, this paper’s findings raise a number of important questions the Government must address in implementing the measures in the Bill. Firstly, they should consider retaining a civil protection order option (NMO). It is clear from the data on increased numbers of NMOs made that victims continue to want civil orders, and previous studies have shown one reason is that they want to retain some control over whether to apply for an order against their (ex-) partner. Whilst DAPOs will allow victims to apply, they can also be issued by police and third parties, and this risks continuing a pattern of disempowering victims by taking the decision to get an order out of their hands. It will be crucial, too, to review how victims’ wishes are taken into account in applications for, and the conditions attached to, DAPOs. Secondly, the Government should monitor the reasons courts reject applications for the new orders, and also assess how significant a problem are the findings in this paper that some victims are unable to apply for orders due to ineligibility for, or unaffordability of, legal aid. Thirdly, with introduction of a new order it will be even more crucial to ensure real clarity amongst police about their powers to enforce breaches of all orders, and to ensure that when orders are made their existence is communicated by courts to police in order that they can enforce breach. Fourthly, the pattern identified in this paper is that breach of orders issued in criminal proceedings and made by the courts (ROs) are enforced over orders issued in civil proceedings and applied for by victims directly (NMOs) – if this pattern continued with the new DAPOs, it risks a parallel regime developing within the same order. Fifthly there is a renewed urgency for a commitment by the police and CPS (perhaps underpinned by national guidance) to prosecute substantive offences where these also constitute breach of an order, rather than only prosecuting for breach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lis Bates

Lead Author now at the Centre for Policing Research and Learning, Open University, Milton Keynes, England.

Notes

1. Ministry of Justice Data (CPS Violence Against Women and Girls Annual Report 2017–18, Annexe 2).

References

- Ashworth, A. and Zedner, L., 2014. Preventive justice. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Barron, A., 1990. Not worth the paper …? Effectiveness of legal protection for women and children experiencing domestic violence. London: National Institute for Social Work.

- Burgess-Proctor, A., 2003. Evaluating the efficacy of protection orders for victims of domestic violence. Women and criminal justice, 15 (1), 33–54. doi:10.1300/J012v15n01_03

- Burton, M., 2010. Civil law remedies for domestic violence: why are applications for non-molestation orders declining? Journal of social welfare and family law, 31 (2), 109–120.

- Capshaw, T.F. and McNeece, A., 2000. Empirical studies of civil protection orders in intimate violence: A review of the literature. Crisis intervention and time-limited treatment, 6 (2), 151–167. doi:10.1080/10645130008951139

- Chaudhuri, M. and Daly, K., 1992. Do restraining orders help? Battered women’s experience with male violence and legal process. In: E. Buzawa and C. Buzawa, eds. Domestic violence: the changing criminal justice response. Westport, CT: Auburn House, 227–252.

- College of Policing, 2015. Using domestic violence protection notices and domestic violence protection orders to make victims safer. Available at College of Policing website: https://www.app.college.police.uk/app-content/major-investigation-and-public-protection/domestic-abuse/arrest-and-other-positive-approaches/domestic-violence-protection-notices-and-domestic-violence-protection-orders/

- Crown Prosecution Service, 2012. Violence against women and girls crime report 2011-12. London: Crown Prosecution Service.

- Crown Prosecution Service, 2014. Violence against women and girls crime report 2013-14. London: Crown Prosecution Service.

- Crown Prosecution Service, 2016. Violence against women and girls crime report 2015-16. London: Crown Prosecution Service.

- Crown Prosecution Service, 2017. Violence against women and girls crime report 2016-17. London: Crown Prosecution Service.

- Crown Prosecution Service, 2018. Violence against women and girls crime report 2017-18. London: Crown Prosecution Service.

- Domestic Abuse Matters, 2014. Police handling of non-molestation orders. Freedom of Information request to Northamptonshire Police and Crime Commissioner. Available from: https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/police_handling_of_non_molestati

- Douglas, H., 2008. The criminal law’s response to domestic violence: what’s going on? Sydney law review, 30, 439–469.

- Edwards, S., 2001. Reducing domestic violence … What works? Briefing note. Crime reduction research series. London: Home Office.

- Edwards, S., 2006. More protection for victims of domestic violence? (The Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004). The denning law journal, 18 (1), 243–260.

- Family Justice Council, 2011. Protocol for process servers: non-molestation orders. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/related-offices-and-bodies/advisory-bodies/fjc/guidance/protocol-for-process-servers-non-molestation-orders/

- Gore, S., 2007. In practice: the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 and Family Law Act 1996 injunctions. Family law (Chichester), 37, 739.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), 2014. Everyone’s business: improving the police response to domestic abuse. London: HMIC.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), 2015. Increasingly everyone’s business: A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. London: HMIC.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS), 2017. A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. London: HMICFRS.

- Hester, M., 2006. Making it through the criminal justice system: attrition and domestic violence. Social policy and society, 5 (1), 79–90. doi:10.1017/S1474746405002769

- Hester, M., et al., 2008. Early evaluation of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004. London: Ministry of Justice.

- Hitchings, E., 2005. A consequence of blurring the boundaries – less choice for the victims of domestic violence? Social policy and society, 5 (1), 91–101. doi:10.1017/S1474746405002770

- Home Office, 2019. Domestic Abuse Bill 2019 domestic abuse protection notice fact sheet. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/817440/Factsheet_-_DAPN.FINAL.pdf

- Hunter, R., 2011. Doing violence to family law. Journal of social welfare and family law, 33 (4), 343–359. doi:10.1080/09649069.2011.632888

- Kelly, L., et al., 2013. Evaluation of the pilot of domestic violence protection orders. London: Metropolitan University and Middlesex University.

- Law Society of England and Wales, 2017. Access denied? LAPSO 4 years on: A Law Society review. Available from: www.lawsociety.org.uk

- Logar, R. and Niemi, J., 2017. Emergency barring orders in situations of domestic violence: article 52 of the Istanbul Convention. A collection of papers on the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Mason, K., 2016. Cuts to legal aid and the impact on domestic violence victims. Vardags Legal Blog, 16 February. Available from: https://vardags.com/family-law/cuts-legal-aid-domestic-violence [Accessed 12 October 2018].

- Ministry of Justice (2018). Family Court Statistics Quarterly England and Wales, October to December 2018. London: Ministry of Justice.

- Office, Home, 2016. Domestic violence protection notices (DVPN) and Domestic violence protection orders (DVPO) guidance. Sections 24-33 Crime and Security Act 2010. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/575363/DVPO_guidance_FINAL_3.pdf

- Home Office, 30 September 2019. Police Workforce, England and Wales. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/861800/police-workforce-sep19-hosb0220.pdf.

- Platt, J., 2008. The domestic violence, crime and victims Act 2004 Part i: is it working? Family law (Chichester), 38, 642–647.

- Practice Direction 12J – Child Arrangements and Contact Orders: Domestic Abuse and Harm. 8 December 2017.

- Practice Direction 36H – Pilot Scheme Procedure for Service of Certain Protection Orders on the Police. 23 July 2018.

- Rigakos, G.S., 1997. Situational determinants of police responses to civil and criminal injunctions for battered women. Violence against women, 3 (2), 204–216. doi:10.1177/1077801297003002006

- Rights of Women, 2015. Domestic violence injunctions. Available from: https://rightsofwomen.org.uk/get-information/violence-against-women-and-international-law/domestic-violence-injunctions/

- Rights of Women, 2018. Written evidence to the Joint Committee on Human Rights inquiry into Enforcing Human Rights. 10th Report of Session 2017-19. HC 669 | HL 171. AET0023.

- Rights of Women, Women’s Aid and Welsh Women’s Aid, 2014. Evidencing domestic violence: a year on. Available from: http://rightsofwomen.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Evidencing-DV-a-year-on-2014.pdf. [Accessed 12 October 2018].

- Sentencing Council, 2018. Breach of a protective order (restraining and non-molestation orders) Available at Sentencing Council website at: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/magistrates-court/item/breach-of-a-protective-order-restraining-and-non-molestation-orders/

- Sussex Police Partnership, 2016. Family and civil orders protocol. A guide for criminal and civil proceedings (Amendment February 2016). Available from: https://sussex.police.uk/media/5806/appendix-d-to-516.pdf

- Van der Aa, S., 2012. Protection orders in the European member states: where do we stand and where do we go from here? European journal on criminal policy and research, 18 (2), 183–204. doi:10.1007/s10610-011-9167-6

- Westmarland, N., McGlynn, C., and Humphreys, C., 2018. Using restorative justice approaches to police domestic violence and abuse. Journal of gender-based violence, 2 (2), 339–358. doi:10.1332/239868018X15266373253417

- Women’s Aid and Queen Mary University of London, 2018. What about my right not to be abused? Domestic abuse, human rights and the family courts. Bristol: Women’s Aid.