ABSTRACT

In March 2020, stringent social distancing measures were introduced across England and Wales to reduce the spread of Covid-19. These measures have presented significant challenges for the family justice system. This article sets out the findings of interviews conducted with professionals in the North East of England who have represented or otherwise supported litigants in private and public children proceedings since social distancing measures were introduced. The findings reveal that whilst practitioners are broadly positive about their experiences of shorter non-contested hearings, they nonetheless have concerns about the effectiveness of remote/hybrid hearings in ensuring a fair and just process in lengthy and complex cases. In particular, the findings indicate that the move to remote hearings has exacerbated pre-existing barriers to justice for unrepresented and vulnerable litigants. The aims of this article are not to ‘name and shame’ any particular court but to highlight evidence of good practice in the North East of England and provide scope for improving practitioners’ and litigants’ experiences within current restrictions.

Introduction

The introduction of social distancing measures in March 2020 presented significant challenges for the operation of the family justice system, with the need to implement a remote court process in an extremely short timescale. The family court promptly distinguished between three categories of work: ‘work that must be done’, ‘work that will be done’ and ‘work that we will do our best to accommodate’ (Court and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020a). Whilst applications for emergency protection, interim care orders and other urgent applications in children cases were prioritised, general administration to progress public and private children disputes fell within the latter two categories, leading to a significant decline in the number of cases being concluded. Prioritised cases were transitioned to the new remote format and in the two-week period between 23 March and 6 April 2020, audio hearings across all courts and tribunals in England and Wales increased by over 500%, and video hearings by 340% (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory , Citation2020a). At the time of writing, HMCTS have confirmed that work should continue to be prioritised in line the President’s guidance but have indicated that the volume of work is ‘slowly returning to pre Covid-19 levels’ (HMCTS Citation2021). With vaccine rollout now well underway, the President has remarked with increased optimism that ‘the light is now at the end of the tunnel’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021, p. 5), but there remains uncertainty about the likely timescales for returning to the courtroom. There is therefore still a pressing need to ‘maintain and enhance good practice with respect to the conduct of remote or hybrid hearings’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021, p. 1).

Whilst the civil and criminal justice systems have experienced comparable levels of upheaval due to social distancing measures, the impact is likely to have been more acutely felt by family court users. In part, this is because social distancing measures have intensified situations of conflict within families, leading to greater reliance on the family courts. Moreover, in comparison to the civil courts where remote hearings have been permitted for some time for procedural hearings, the family courts were at an earlier stage of the digital reform programme, with remote engagement being primarily reserved for the filing of applications and orders. Evidence being given remotely has, until the introduction of social distancing measures, typically been reserved for victims of domestic abuse as a ‘special measure’ to facilitate victims’ effective participation in hearings (Practice Direction 3AA Family Procedure Rules 2010). Remote technologies in the family courts have proved widely problematic, with Sir James Munby reporting that ‘video links in too many family courts are a disgrace – prone to the link failing and with desperately poor sound and picture quality’ (2017, p. 12). He argued that ‘more, much more, needs to be done to bring the family courts up to an acceptable standard, indeed, to match the facilities available in the crown court’ (p.12). Finally, the family court has been the victim of considerable cost-saving measures over the last few years (The Law Society of England and Wales Citation2017, Speed Citation2020). Literature demonstrates that the family courts have been plagued by delays and backlogs for some time now because of reductions in judicial staffing and closures of the court estate (Kaganas Citation2017, Ministry of Justice Citation2019). Cuts to the scope and availability of legal aid following the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 have led to both an increase in the volume of work being dealt with in the family courts following unsuccessful attempts to divert cases through mediation (Barlow Citation2017) and the number of litigants in person in the family courts (Richardson and Speed Citation2019). It is widely documented that litigants in person increase the administrative burden on the family courts due to difficulties in identifying the key issues in dispute and complying with litigation procedure (Organ and Sigafoos Citation2018, Richardson and Speed Citation2019). Accordingly, cost-saving measures had reduced the capacity of the family courts to function effectively even in a pre Covid-19 landscape.

This article sets out the findings of interviews conducted with professionals in the North East of England who have represented or otherwise supported litigants in family court proceedings since social distancing measures were introduced. The first part of the article sets out the key changes to private and public law children practice as a result of the pandemic. The second part outlines the findings of the research. The findings reveal that whilst practitioners are broadly positive about their experiences of supporting litigants with shorter non-contested hearings, they nonetheless have concerns about the effectiveness of remote/hybrid hearings in ensuring a fair and just process for court users in lengthy and complex children proceedings. In particular, the findings indicate that the move to remote hearings has exacerbated pre-existing barriers to justice for unrepresented and vulnerable litigants. The aims of this article are not to ‘name and shame’ any particular court, but to highlight evidence of good practice in the North East of England and where there is scope for improving practitioners’ and litigants’ experiences within the current restrictions.

Guidance on private children cases during the pandemic

In response to confusion amongst parents, the President set out an exception to the ‘Stay at Home’ regulations that ‘[w]here parents do not live in the same household, children under 18 can be moved between their parents’ homes’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020d). The guidance created ambiguity by noting that the exception does not mean children must be moved between homes; rather, parents should make ‘a sensible assessment of the circumstances, including the child’s present health, the risk of infection and the presence of any recognised vulnerable individuals in one household or the other’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020d). It was recommended that parents could depart from the arrangements through mutual agreement, as would be the case regardless of the Covid-19 crisis, but it was also acknowledged that a parent could unilaterally restrict or wholly depart from arrangements that may compromise compliance with Public Health England advice (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020d). Parents were encouraged to use technology to support contact when direct contact was not possible. This sentiment does not seem to accord with the provisions for children to continue to attend school throughout most of the pandemic and mix with peers and teachers. Moreover, the guidance refers to the child’s parents, but makes no mention of others with the benefit of a Child Arrangements Order (CAO), such as grandparents or extended family members.

Where one parent has unilaterally departed from a CAO, an enforcement application may be necessary under s11J Children Act 1989. In consequence of the demand on the family justice system and in line with pilot Practice Direction 36Q, temporary procedural changes have been permitted. Where an application for enforcement is made, the court will determine whether the application has arisen due to the pandemic (Cafcass , Citation2020a). If so, the court will send a standard letter to the applicant providing advice and recommendations, as well as a note that the First Hearing Dispute Resolution Appointment will likely be listed on a date in excess of 12 weeks from issuing the application (Cafcass Citation2020a). The Family Court Adviser will contact the applicant and work with the parties with a view to resolving the dispute when completing the usual safeguarding checks. The family court will consider during the proceedings whether each parent acted ‘reasonably and sensibly’ considering official advice and the rules in place at the time (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020d).

As at the time of writing in May 2021, the advice of the President had not changed in respect of private law children cases since March Citation2020. Regional specific guidance for Cleveland, Durham and Northumbria was however produced in April Citation2020 (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020). On the one hand, this guidance made clear that during the pandemic cases should continue to be heard as listed and ‘all appropriate efforts should be made to resolve cases/issues where this can safely be done in the interests of children, particularly to agree at least interim holding positions for their care’ (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, p. 1). On the other hand, for private law proceedings the guidance also recommends that ‘where there does not appear to be a safeguarding issue and the case is not urgent, the court may consider staying or adjourning for the parties to consider non-court dispute resolution including MIAMs or mediation’ (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, p. 4). Adjourning proceedings for this purpose has always been a possibility in private law children cases, even prior to the pandemic (Practice Direction 12B, para 6.3). If the parties agree to and successfully use non-court dispute resolution to reach an agreement, this will of course assist with the backlog of cases. However, many parties will already have considered this option prior to proceedings as part of the compulsory pre-application MIAM (Practice Direction 12B, para 5.3). For those parties, this adjournment could simply be an unnecessary and unhelpful delay to their cases. To the authors’ knowledge, this regional guidance has not been updated since April Citation2020.

Guidance on public children cases during the pandemic

In contrast with the limited guidance provided in private law cases, a substantial amount has been produced in relation to public law children proceedings.

On 19 March 2020, the President set out that emergency protection orders, interim care orders and issue resolution hearings were likely to be capable of being dealt with remotely, and that any case which could not be listed for a remote hearing ‘should be adjourned and promptly listed for a directions hearing, which should be conducted remotely’ (Court and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020a). In urgent cases, the guidance was that a remote hearing should be favoured unless this was not possible (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary 2020a).

At this early stage, concerns were also raised regarding the legislative provisions for adoption and fostering. On 24 April 2020, after being laid before Parliament for 24 hours, The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations Citation2020 (SI 2020/445) came into force, providing temporary changes to local authority duties in relation to children’s services and adoption. These amendments allowed visits to a child in a foster placement to take place by telephone, video link or other electronic means (Regulation 8) and relaxed Looked After Children Reviews to at least every six months where this was ‘reasonably practicable’ (The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations Citation2020). The amendments were subsequently successfully challenged in the Court of Appeal who considered that the government had acted unlawfully by failing to consult bodies representing children in care before making the amendments. Five amendments to the regulations remain in force until 30 September 2021 (The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2021).

In initial cases where a final care decision was required, the conflict between urgency for the child and fairness for the parties became a pressing issue. The case of Re P (A Child: Remote Hearing) [2020] EWFC 32 initially outlined factors for consideration in deciding whether a final hearing should be conducted remotely or adjourned. These include:

The category of case or the seriousness of the decision;

The availability of local facilities and technology;

The personalities and expectations of key family members; and

The experience of the judge or magistrate in remote working

The judge emphasised that each case would be fact specific (paragraph 24) and that the court should consider whether a case should proceed remotely, even if it can logistically (paragraph 8).

Following this decision, the cases of Re A (Children) [2020] EWCA Civ 583 and Re B (Children) (Remote Hearing: Interim Care Order) [2020] EWCA Civ 584 set out that deciding whether a hearing should be dealt with on a remote basis would be a case management decision for the Judge. In Re A, factors to assist with the making of this decision were given and included criteria such as the importance and nature of the decision to be determined, the need for urgency, and whether the parties were legally represented (paragraph 8). In this case, the ability of the father, who had a diagnosis of dyslexia, to engage with remote proceedings, was found to be a determinative factor in allowing the appeal against the decision to hold a hybrid hearing (Re A (Children) [2020] EWCA Civ 583, paragraph 10). Re B further considered the procedural fairness of a remote hearing and again overturned a decision made by the lower court. In this matter, the approach of the court was criticised, with decisions such as the lack of notice of change in relation to the care plan, and the grandmother’s opportunity to consider evidence and discuss matters with her representative calling into question the fairness of the proceedings (Re B (Children) (Remote Hearing: Interim Care Order) [2020] EWCA Civ 584, paragraphs 24–25). The court determined that an adjournment should have been granted but acknowledged the ‘highly pressurised circumstances in which all the participants were working’ (Re B (Children) (Remote Hearing: Interim Care Order) [2020] EWCA Civ 584, paragraph 39).

Amid this context, the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (, Citation2020a) identified concerns about the urgent removal of new-born babies under interim care orders with many professionals expressing concerns at the way in which parties, and particularly new mothers, were able to access and engage with this type of hearing (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory Citation2020a, p. 21) and technology (para 3.3). The need to achieve finality in decision making for children subject to care proceedings, particularly considering the overarching consideration of the child’s welfare, has also been a key consideration of the President (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c). Professionals were reminded that ‘delay in determining a case is likely to prejudice the welfare of the child and all public law children cases are still expected to be completed within 26 weeks’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c). To achieve this, a move towards ‘hybrid’ hearings was identified for those cases previously deemed unsuitable for remote hearing, although it was acknowledged that the ability to achieve this in all cases would be resource dependent. Guidance was given that while ‘telephone hearings may be well suited to short case management or review hearings, they are unlikely to be suitable for any hearings where evidence is to be given or where the hearing is otherwise of substance’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c, p. 6). Suggestions were made to promote support for parties involved in court proceedings, by facilitating their engagement from a location other than their home so that they could be assisted by a member of their legal team (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c).

The complications of achieving fairness and parity between parties in ‘sub-optimal court settings’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c, p. 3) was more fully considered in the cases of A Local Authority v The Mother and Others (Covid 19: Fair Hearing: Adjournment) [2020] EWHC 1233 (Fam) and A Local Authority v M [2020] EWFC 43. The court found that it was clear from the President’s guidance at paragraph 6 and 11 (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c) that there was a need to achieve finality in decision making and that continuing to adjourn the case would not be a viable option.

The issue of contact between parents and children in care has also become a key issue during the pandemic. Department for Education guidance (Citation2021) makes clear that the expectation is for contact arrangements to continue during the pandemic where possible, with virtual alternatives being the exception rather than the norm (Department for Education 2021). Despite this, the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (, Citation2020b) reported ‘considerable concern that mothers have frequently not been able to have any physical contact with their babies following their removal’ and that contact has been predominantly virtual (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory Citation2020b, p. 32). In the case of Re D-S (Contact with Children in care: COVID-19) [2020] EWCA Civ 1031, the appeal of the mother was allowed on the basis that the wrong approach had been taken in consideration of the application, in that the Judge had erred in assessing whether the local authority’s contact arrangements were reasonable, rather than determining what was in the best interests of the child. While the NFJO report indicates that some face-to-face contact now appears to be resuming (p.32), reports are that this continues to be a slow process and one which remains a real issue for families involved in care proceedings. In the North-East, local guidance also reiterates that, ‘what is reasonable must be considered in that context and section 34 applications for contact made sparingly’ (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020).

Methodology

The paper draws on data obtained from 15 in-depth interviews with professionals in the North East of England who participated in remote and/or hybrid hearings in the family court since lockdown measures were introduced in March 2020. This paper considers the findings relating to private and public law children proceedings. The findings in relation to applications for injunctive protection under the Family Law Act 1996 are reported separately (see Speed et al. Citation2021).

The study is one of the first of its kind to consider the effectiveness of the remote family court during the pandemic. Whilst the authors are aware that the NFJO has published two reports on the capacity of the remote family court to provide fairness and justice for court users, their data was based primarily on quantitative survey data (, Citation2020a, , Citation2020b). By focusing on in-depth interviews, this is the first paper to provide qualitative understandings of some of the issues raised in the NFJO’s reports. Further, this is the only study to offer specific insight into the experiences of practitioners supporting family court users in the North East of England during this time.

The interviews were conducted between September 2020 and December 2020. This represented a period of significant activity within the Covid-19 restrictions in the North-East. Within weeks of beginning the interviews, many council areas in the region were moved into Tier 2 restrictions, meaning residents were not permitted to socialise with those outside their own households (or support bubbles) in private homes. On 5 November 2020, England and Wales moved into a second national lockdown and subsequently, many of the local authority areas in the North-East were moved into tier 3 restrictions, resulting in continued restrictions on socialising and the closure of non-essential shops and the hospitality industry.

Semi-structured interviews were used, all of which were conducted remotely. This decision was one of ‘methodological necessity’ owing to the regulations described above (Johnson et al. Citation2019, p. 3). Johnson et al recognise that whilst interviews conducted remotely ‘do not significantly differ in interview length and substantive coding, they likely do often come at a cost to the richness of information produced’ (p.1). This is largely because in-person interviews ‘provide the most natural conversational setting, the strongest foundation for building rapport, and the best opportunity to observe visual and emotional cues’ whereas remote interviews can be ‘difficult to manage, more likely to result in misunderstandings and limited in their ability to generate meaningful conversations’ (Johnson et al Citation2019, p. 2–3). It is the authors’ position that the risk of remote interviewing resulting in misunderstanding or otherwise affecting the validity of the findings was mitigated by the authors’ qualifications as family law practitioners. Further, utilising video conferencing facilities in most of the interviews, ensured that at least some non-verbal and emotional cues could be identified.

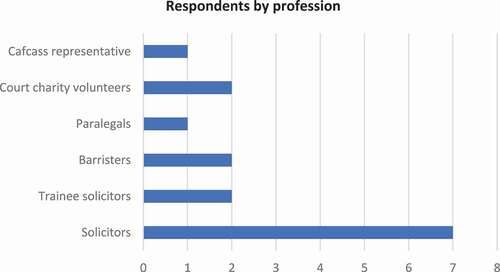

sets out the roles/professions of the 15 participants in this study. Six of the professionals worked in predominantly legal aid practices whilst two described their work as mostly privately paid. Two of the solicitors worked for different local authorities in the region. All respondents had experience representing or supporting parties in private and/or public children proceedings since March 2020. Three of the interviewees exclusively practised in public children work, whilst only one practised solely in private law. Six of the interviewees reported specialising in both areas. The remaining six respondents were less specialised either because they were still in training or because they were volunteers at services which supported litigants in all types of family law (and general civil) disputes.

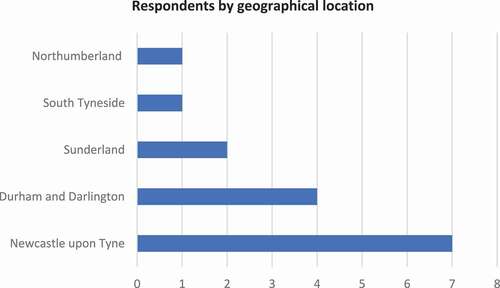

In terms of geographical spread, as demonstrates, the respondents’ offices were located in various places across the region. Whilst the interviewees reported having experiences of multiple courts in the North-East region over the relevant period, the data focusses on the geographic region of the North East of England rather than the judicial definition, which also includes York, Bradford, Sheffield, Leeds and Hull.

A snowball (or chain-referral) sample was utilised to recruit the respondents (Naderifar et al. Citation2017, p. 3). As the research team comprised family law practitioners, initial access proved unproblematic and referrals to other colleagues were forthcoming. Qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on the interview data using NVivo, which is recognised for providing a more rigorous method of coding compared to manual or other digital processes (Hoover and Koerber Citation2011). Two of the authors separately coded three of the interview transcripts to ensure a consistent approach. Thereafter, each of the remaining transcripts were coded by one of those two authors. Following both Urquhart (Citation2013, p. 194) and Given (Citation2016, p. 135), saturation was considered to be reached at the point in coding where there were ‘mounting instances of the same codes’, but no new codes or themes emerged from the data.

In order to protect the identities of the participants, no pseudonyms have been attached to any of the quotes. This is due to the small family law circuit of professionals operating in the North-East and concerns that, when taken together, multiple quotes attached to a pseudonym may reveal the identity of the participant.

Limitations of the study

Whilst it is a central claim of the article that the move to remote hearings has exacerbated pre-existing barriers to the family courts for litigants in person, the data on which these findings are reached reflect the experiences and perceptions of the professionals interviewed rather than through the authors having direct contact with litigants themselves. This was also a limitation in the first NFJO report (, Citation2020a) and something that they sought to address in their second report through the involvement of the Parents, Families and Allies Network and Litigant in Person Engagement Group in their research (, Citation2020b). Despite this, the number of responses from litigants in person within the second report was still low (42% of the 132 parents surveyed reported being unrepresented in proceedings) (Nuffield Family Justice Observatory Citation2020b, p. 9).

As the respondents in this study worked in varied settings, so too were their interactions with litigants in person. Principally, the respondents faced unrepresented opponents (or other parties) as part of the cases in which they were involved. For the two volunteers who worked at a court-based charity, their roles involved them providing practical and emotional assistance to litigants in person before, during and after family court hearings. The trainee solicitors and paralegal interviewed also reported triaging prospective clients and endeavouring to facilitate referrals to alternative sources of advice and support where they were not eligible for legal aid.

Earlier studies have highlighted that there is value in seeking practitioners’ views about the challenges faced by litigants in person because of their understanding of legal process and the issues being litigated (see Trinder et al. Citation2014, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory , Citation2020a, , Citation2020b). The authors are nonetheless mindful that as legal professionals conducting interviews with other practitioners, there may have been common understandings and shared experiences between the interviewer and interviewee ‘about’ litigants in person which is reflected in the data. The NFJO identified in their second report that the perceptions of professionals can sometimes be at odds with the perceptions of litigants themselves (2020b). This absence of data ‘from’ litigants in person therefore represents a gap in the research which should be addressed in future studies.

Findings and discussion

Operational guidance

Respondents were asked about their ability to keep on top of developing guidance and changing court practice. A volunteer at a court-based charity was critical of the lack of guidance from the local family court, indicating that they have had to ask directly for updates and seek out information for themselves. They noted that, where guidance was provided, it was ‘at a national level’. They felt that their local court had not been ‘great at keeping us updated or keeping in touch’. This is despite a court-based support service (Support Through Court) being acknowledged in the regional guidance as a helpline for vulnerable litigants who require support with the remote court process and therefore a key stakeholder in the court experience (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, p. 5).

Legal practitioners had the opposite issue and often felt bombarded with information. They gave examples of colleagues and other agencies trying to be helpful by recirculating information but ‘sometimes you end up getting the same information three times just because everyone wants to make sure that at least it’s been disseminated’. Practitioners also commented on the amount of guidance being provided, the frequency of updates and the number of times that guidance is revised with some documents now having multiple iterations. This reflects concerns raised by the Law Society that members were experiencing ‘guidance fatigue’ (Law Society, Citation2020).

Whilst most practitioners appeared to have kept on top of the guidance, they felt this was likely to be difficult for litigants in person. This was exacerbated by limitations in the assistance which could be offered by Support Through Court, law clinics and McKenzie Friends (NFJO , Citation2020b). One respondent suggested that information must be more accessible, such as through the provision of leaflets. The Transparency Project (Citation2020) have taken steps to try and make information accessible for lay parties through online documents, including a guidance note on ‘Remote Court Hearings’. However, this guide was produced in June 2020 and may not therefore reflect the most recent guidance on remote court proceedings. The success of guidance notes also relies on litigants in person knowing where to find them. Litigants in person often require more information about the court process in ordinary times, notwithstanding the increased pressure and changeable rules throughout the pandemic (Trinder et al. Citation2014).

The findings also demonstrate inconsistency in judicial interpretation of guidance. The respondents noted that, particularly at the outset of the pandemic, this made advising clients a difficult task. Discussing private law children disputes, one respondent noted:

Say I’m instructed by someone who didn’t want to hand the child over and I said ‘look, I can’t advise not to especially with a court order in place, but you have parental responsibility; you need to do what’s in the best interest of your child. You’ve got to balance that with the fact that it’s within the best interests to have contact with the other parent as well’. As soon as the guidance came out, I mean, it kind of depended on what judge you got, but a lot of judges were saying no contact needs to take place. … And that was just kind of the line … it’s obviously got a lot better now, but at that point, when the guidance was initially released, it was really confusing.

Different practices were also acknowledged in remote hearings. The respondents noted that in some courts, the Judge dials in the parties whereas in other courts, parties are provided with joining instructions. A consistent approach should be taken by all courts across all regions, technology permitting. Where this is not possible, the authors echo the recommendation by Speed et al. (Citation2020) that regional guidance for litigants in person should be produced and updated regularly. The guides should be made widely accessible, perhaps through the court providing a copy enclosed with the notice of hearing to any self-representing parties in proceedings. This recommendation is echoed by The Law Society in their response to the NFJO (, Citation2020b, p. 30). Solicitors could also provide this guidance to their clients, alleviating some of the onus on legal professionals at a time when the workload is so high.

Delay

Many respondents commented on the ‘significant delays, resulting from adjournment of hearings during the initial lockdown’ and felt that, while cases were now beginning to return to court, there continued to be delays in decision making for families in children proceedings. Comments about delays were made in relation to both public and private children cases, notwithstanding that a considerable proportion of public law children work has fallen into the category of ‘work that must be done’ and should in theory have faced lower levels of disruption (Court and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020a). Because of delays, cases were effectively forced to restart. The respondents noted, ‘you can’t just jump straight back in when you’ve got young children; you have to start it all over again’ and ‘Covid stopped a lot of plans from progressing’.

In public law proceedings, some respondents reported positive benefits to the delay, in that it offered parents an opportunity to demonstrate a change in circumstances and request a reassessment due to the time that had passed. However, respondents also noted the impact that this could have on the 26-week limit implemented by s14 Children and Families Act 2014, particularly where new expert evidence was required. In direct conflict with the guidance issued by the President that proceedings should still be concluded within these timescales (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c), respondents gave examples of some public law cases being at ‘35–40 weeks’ due to adjournments and requests for reassessments. This issue is also evidenced by the family court statistics from July to September 2020, which demonstrate that the average length of public law proceedings from application to disposal was 40 weeks, with only 29% of cases being disposed of within the 26-week limit (Ministry of Justice Citation2020b). That said, if this gives an opportunity for parents to make positive lifestyle changes and for children to potentially remain with their biological families in the long term, this is arguably a positive use of this time. As raised earlier, this always needs to be balanced against the need for urgency for the child (Re A (Children) [2020] EWCA Civ 583) and the implementation of the no delay principle (section 1(2) Children Act 1989).

Whilst some families will undoubtedly make use of this extra time to improve their position within proceedings and to make long lasting changes, there were concerns that remote working had impacted some lay parties’ willingness to participate with third party services. Many felt that there was greater opportunity for evasion for those unwilling to engage:

I don’t know whether there’s some people that have tried to play the system, I can imagine that that has happened on quite a few occasions. Where people are “ah, I can’t attend I need to isolate”, or “I’ve come into contact with this person and that person”.

Considering this, it is understandable why some respondents have taken the view that delay was unlikely to make a material difference to the outcome of proceedings and, if anything, could be detrimental to their client’s case:

I’ve yet to see [delay] actually assist a parent. I do know that a lot of them out there have already said “oh well this is going to give me some more time now. I can show you that I do this, this and this and the sustainability that you didn’t have before, I have now got”. I think it could help some parents, but again, on the flip side of things, if things haven’t improved or digressed …

The respondents acknowledged that it is not just parents creating delay. There was mention of local authority delay through inconsistent approaches to gathering evidence and conducting assessments across different areas of the North-East, as well as some local authorities prioritising urgent matters only. There were also delays in awaiting safeguarding disclosures from the police.

Similar findings can be made in relation to private children proceedings where contact has been prevented by one parent. In such cases, delay provides an opportunity for a parent to argue that the child is now in a routine, and contact should be gradually increased, rather than returning immediately to the original level of contact. Reassuringly, guidance from the President acknowledges that avoiding delay will be an important, sometimes determinative, factor in case management (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021). However, the reality appears to be different. A respondent noted that, ‘there were significant delays, resulting from adjournment of hearings during the initial lockdown – hearings have been delayed for months’. Another respondent (a Cafcass representative) reported having been instructed in private law cases which had been issued over 12 months previously but were no further forward due to delays arising from the pandemic. As mentioned earlier, the standard court letter to applicants seeking enforcement provides that the first hearing will have to be listed on a date in excess of 12 weeks and regional North-East guidance recommends that adjournments should be considered for the parties to engage in non-court dispute resolution instead of progressing with the proceedings as listed, thus stifling contact arrangements and prompt access to justice.

A respondent noted that they ‘did have a couple of parents where the conflict was already there, that [they] felt they were using Covid as an excuse not to promote contact … citing Covid when it was very clear that contact could be promoted’. Where there is conflict, parents will inevitably look for reasons to prevent contact and Covid has presented a justification which is indirectly supported by government and the court.

Notwithstanding, many parents have legitimate concerns arising from the government regulations, including holiday quarantine periods changing while away with a child, or cessation of arrangements where one parent or a member of the household is vulnerable. Guidance on contact arrangements where a child is self-isolating or has to quarantine on return from a trip abroad has since been provided in a House of Commons briefing paper (Foster and Loft Citation2021). In relation to quarantining, a shared care arrangement is a permitted reason for moving between two households (Foster and Loft Citation2021). The position is less clear where a child is self-isolating, with parents being encouraged to agree ‘for a child to remain at the same address during their period of self-isolation’ and to seek ‘specialist advice’ if contact is court ordered (Foster and Loft Citation2021).

The respondents noted that in public children proceedings, Judges are listing subsequent hearings during the course of the hearing, yet with private law children proceedings, there is a tendency to list after the hearing has concluded, therefore causing further delays. This has led to occasions where the court has listed hearings when representatives, local authority, Cafcass, or experts were not free. It would be sensible for a consistent approach ensuring that professionals are consulted about their availability to minimise hearings being vacated.

Backlog/workload

Respondents talked about a ‘backlog’ of cases, echoing a similar view to the President that the backlog had existed long before Covid-19, but had been exacerbated by the reduction of cases concluded in the immediate response to the first lockdown (Court and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c, Citation2021). One practitioner reported public law proceedings being issued during the first lockdown, but not having a final hearing listed until the first quarter of 2021. This is also evident in the July to September 2020 family court statistics, where the average time for a care or supervision case to reach first disposal has been the highest since mid-2013 when the most recent legal aid cuts came into force (Ministry of Justice , Citation2020b).

Many respondents noted the strain on the family justice system in tackling this increase in both volume and complexity, whilst meeting the necessary time management requirements (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c, paras 42 and 43). There was significant concern at the impact this had on the decision-making process:

… we need to think how to get rid of the backlog, but also how it’s fair … I don’t think getting rid of the backlog by rushing through cases by remote means for public law is acceptable at all. I just don’t.

Practitioners talked about the increased workload experienced as the family court clears some of the backlog, reporting starting work as early as 5:00am and not finishing court hearings until 6.30pm. The working day of course does not end with the last court hearing. For practitioners who are qualified as mediators, the working hours can be even longer, with one respondent reporting that her mediator colleague’s mediations would begin at 8pm or 9pm and last for ‘a couple of hours’. Those working hours are clearly not sustainable and it is hoped that reopening schools and early years settings has somewhat eased the need for out of hours services. This issue was acknowledged by the President of the Family Division in his 2021 guidance, where he encouraged a return to normal working hours of between 10.00am and 4.30pm with additional hearings outside those times becoming ‘an exceptional occurrence, and not the norm, and limited to no more than a 30-minute extension to the court day’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021, para 16).

In private law disputes, the volume of cases was considered to be higher than pre Covid-19 levels owing to the fact that ‘a lot of previous arrangements have gone out of the window’. One respondent noted ‘when the first lockdown was announced, it was incredibly quiet, I mean there was nothing coming through, no referrals. Then I would say over the last two months, or really since September, it’s just been really, really, really busy, very busy’. This increase is supported by Cafcass’ Private Law Data (2020b), which demonstrates there were 2,560 cases in April 2020, compared with 4,200 cases in September 2020, as well as the national statistics for July to September, which show private law case starts increasing by 8% compared to the equivalent quarter in 2019 (Ministry of Justice Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

As with public law proceedings, concerns were raised about the impact of a high volume of private children cases on case management decisions. Respondents noted that in cases where domestic abuse or safeguarding concerns are alleged, few fact-finding hearings are currently being directed, with practitioners required to justify the need for such hearings. A respondent noted, ‘fact-finding hearings have been reduced because obviously the amount of court time it takes and being able to do it remotely’. Some necessary fact-finding hearings simply had to keep being adjourned. The low rate at which fact-finding hearings are ordered is a concern which precedes Covid-19. Hunter et al. (Citation2017) identified that fact-finding hearings are ‘inconsistently and rarely held’ (p.405), whilst a study by Cafcass and Women’s Aid found that fact-finding cases were only held in five out of 134 cases where allegations of domestic abuse were raised (Citation2017, p. 10). Although the Ministry of Justice Harm Panel Report reported evidence being provided at a judicial roundtable and by Rights of Women that more fact-finding hearings have been held since 2017 (Ministry of Justice Citation2020, p. 84), this was not reflected in the experiences of all the professionals and organisations with which they had consulted. Others reported a continued reluctance to order such hearings and a systemic minimisation of the relevance of domestic abuse allegations (Ministry of Justice Citation2020, p. 90–91). It is therefore concerning that the courts are seemingly more reluctant to order such hearings during the pandemic, particularly given that they are one of the leading mechanisms for safeguarding compliance with Practice Direction 12J. A balance must be struck between tackling the backlog and preventing cases being rushed through, particularly where the outcome may be life-changing for those involved.

Format of hearings

The regional guidance issued in April 2020 provided that ‘the default position is that all family court hearings will be carried out remotely until further notice’ and ‘attended hearings will be exceptional’ (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, p. 1–2). In line with the guidance set out by the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary (Citation2020a, Citation2020b), the respondents acknowledged that the format of hearings has developed since then. They reported that initially ‘everything was taking place via telephone’, then it ‘moved to hearings via CVP’, whereas ‘hybrid hearings … are the new sort of thing now at this moment in time’. However, many of the respondents were interviewed prior to the most recent guidance issued by the President, which emphasised the need to minimise footfall in the court (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021). The responses provided may therefore be different if the participants were interviewed again.

The respondents supporting litigants in person highlighted a need for correspondence to be more explicit that hearings are taking place remotely. One noted, ‘the letter that goes out to them isn’t massively clear about what they’re being asked to do’. The same respondent acknowledged that letters simply refer to parties being ‘requested to attend a hearing’ … ‘so a lot of litigants in person are reading that letter and presuming that they need to come into the court. When actually the hearing is taking place remotely’. This conflicts with the standard letter to litigants in person which is appended to the regional guidance and explicitly states ‘this means that you are not to attend court for the hearing but can attend the hearing by [telephone/Skype]’ (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, Appendix 3). This may indicate that the standard approved letter is not being used by all courts in the region. It would be possible for courts to address this issue with relative ease by consistently adopting the letter recommended by HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC. This finding supports the recommendations of Trinder et al. (Citation2014) advocating for provision of clearer and more accessible guidance to litigants in person.

Those respondents who had been involved in hybrid hearings highlighted several administrative difficulties. Respondents commented that ‘those types of hearings take an enormous amount of time and effort, energy and are just very stressful to deal with, from Judges and across the board to be honest’. Discussing the administrative onus that the court places on representatives in setting up those hearings, one respondent commented that they felt like they ‘almost became the judge’s PA … it was just constant’. They gave examples of having to make all the arrangements with witnesses and having to give witnesses’ details to the clerk multiple times. One of the volunteers at a support service reported similar issues with providing their details to the court, only for those details to be lost at some stage meaning that they were not called into a hearing to support a litigant in person whose first language was not English. However, it should be noted that the respondent was referring to a court elsewhere in England when giving this example, not within the North-East where the regional guidance specifies an email address which is to be used for this purpose (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020, p. 2). Nonetheless, these examples point to a clear administrative issue with communication of and recording of key details by courts elsewhere in the country. This issue is perhaps not surprising given the cuts made to court staffing over recent years which have seen the number of full-time staff employed by HMCTS fall from 20,392 in 2010 to 14,269 in 2017 (Kaganas Citation2017, Ministry of Justice and HM Courts & Tribunal Service Citation2019). The authors therefore recommend that family courts across England and Wales follow the approach of the North-East courts by designating an email address for the purpose of providing contact details to the court. The authors also support the recommendation made by Speed et al. (Citation2020) that a specific court form should be used to provide the court with information about the parties’ access to technology and ability to engage with remote court hearings. The current C100 and C79 forms do not fully provide for engagement in remote and hybrid hearings.

Despite practical difficulties, many respondents were in favour of the continued use of remote hearings in straightforward case management hearings to counter some of the additional delays. A representative from Cafcass discussed being able to attend more hearings, rather than prioritising one if she is listed in one court at 10am and another at 11am, leading to more cases being finalised within a shorter period. Respondents were particularly positive about the reduced travel time for short case management hearings, where the travel time would often exceed the length of the hearing itself. However, there was also a strong feeling that ‘remote hearings do not work for final hearings’ or for contested hearings, particularly in public law cases. Discussing some of the technological issues, one respondent commented:

I think ones where evidence is being given are impossible because not just withstanding the fact that the audio isn’t always great on CVP, people drop out of it, people can’t be joined and they’re waiting and then they are not there anymore and you’ve got to dial them back in or somebody hangs up by mistake. People are on mute and are speaking and think people can hear them. I’m not fantastic at IT, but I don’t think the IT is of the level where it is appropriate for a hearing at all. It’s very difficult to hear what judges are saying. Parents sitting at home on a telephone line can hardly hear anything at all.

In public law proceedings, there will inevitably be cases where urgency prevails over the time it would take to make arrangements for a hybrid/in person hearing, but respondents raised some very concerning examples of where urgency has led to parents being expected to participate in wholly inappropriate circumstances:

I’ve had a case very early on in lockdown where I think the courts were just desperately trying to keep things going where it was a removal case, an interim care order and the mother was in hospital, crouched under a stairwell in the hospital. Listening to, well being cross examined, giving evidence about why she should keep her child in a, well she was trying to be in a public quiet place, but she was in the hospital and she had just given birth. I appreciate that it wasn’t a case of “oh well we will come back next week”. It was an urgent case. It has to be dealt with urgently, but it just didn’t feel right at all.

Unfortunately, the second NFJO report demonstrates that this was not a one-off or regional incident, with multiple examples being provided of mothers of newborn babies being forced to attend emergency court proceedings by telephone (2020b, p. 19). The family court has been critical of local authorities who have sought consent to section 20 accommodation in similar circumstances (Coventry City Council v C [2013] EWHC 2190), so it is difficult to understand how fairness can be achieved by expecting a mother to participate in emergency proceedings, without any support due to the restrictions that hospitals now have in place on visitors attending.

Even in ‘normal’ circumstances where a parent has been able to seek legal advice and is participating in the proceedings from home, a primary concern for respondents was the available support for parents involved in care proceedings. Concerns have been highlighted above about the need for privacy, but for many parents, this will not be possible due to the presence of children at home. One respondent discussed a situation where the subject child was not only present, but was asked to become involved in the proceedings.

Their father was saying “well that’s not true at all … you can ask him ‘cause he’s here”. And then this child was put on the phone in the middle of a hearing with the dad shouting in the background at the child to tell the judge what had happened, that it “wasn’t f-ing true”.

While some respondents highlighted occasions where additional arrangements were made to assist with children who would otherwise be present in the family home, they indicated that these arrangements were often down to the discretion of, and resources available to, the relevant local authority. It is unsurprising that this was quoted as an issue in the North-East region, which has been impacted heavily by government funding cuts over the last 10 years. Those cuts are set to continue, with the TUC estimating that councils in the region will face a £1.2bn funding gap by 2025 (TUC Citation2019). However, this is unlikely to be unique to the North-East with many other regions across England having experienced similar cuts.

For many, there were concerns at the level of support available to parents in situations where a care or placement order was made under remote circumstances:

She couldn’t see anybody, she couldn’t see who was talking about her, she couldn’t see the judge giving his judgment at the end of the day. She, one particular mother, was extremely distressed and it was harrowing to listen to her audibly upset, understandably so on the telephone … I was concerned about what support she had after the hearing because I had no idea who she was with … I was so concerned I actually contacted a solicitor to see if there was anything that could be done to see if there was any support that could be offered to this mother who’d just effectively lost her child.

This is a clear argument against remote proceedings being used for final hearings in public law proceedings. For professionals, there was an overwhelming feeling that remote hearings were impinging on their ability to engage and empathise with clients and parties involved in proceedings, something which many felt to be a key part of their role.

There were concerns for lay parties with additional needs, who have a strong accent or whose first language is not English, and whether these needs were being fully met in remote circumstances. Studies prior to Covid-19 have highlighted that ‘language difficulties’ can be a source of vulnerability for litigants, whether or not they are legally represented (Trinder et al. Citation2014). Evidence also suggests that due to poor outsourcing decisions, there is a limited availability of good quality and independent interpreters, a situation which has been worsened by ‘the contemporary political backdrop of cost-saving imperatives and rising concerns about immigration’ (Aliverti and Seoighe Citation2017, p.137).

The need for an interpreter was a factor listed by The Law Society as a reason against holding a hearing remotely (The Law Society Citation2020). The difficulty with using interpreters in remote proceedings was also accepted by the President (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary , Citation2020c). However, he indicated that hybrid or in-person hearings may also have similar difficulties due to the interpreter needing to remain two metres away from the party who requires their assistance because of social distancing requirements (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c, para 29). In debating this issue, he suggested that:

Active thought should be given to arranging for a lay party to engage with the remote process from a location other than their home (for example a solicitor’s office, barrister’s chambers, room in a court building or a local authority facility) where they can be supported by at least one member of their legal team and, where appropriate, any interpreter or intermediary (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c, para 28).

Social distancing requirements would apply equally to any of those venues, as they would to a courtroom, so it is difficult to see how this would assist. A better solution proposed by the President is for interpretation to be provided ‘over a separate open phone line with the interpreter and client using earpieces, or typed interpretation over linked computers or email’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2020c, para 29). However, this relies on the party having access to this technology themselves or their solicitor being able to provide them with access. Whilst many solicitors are working from home, this may have practical difficulties, and courts may have to be willing to either provide access to this technology themselves or accept that hearings are likely to take far longer (and need to take place in person or in a hybrid format) where an interpreter is required.

Litigants in person

Accessibility of technology

While to some extent it is to be expected that solicitors may assist their own clients with the remote court process by providing an office space, this study revealed that there was also an expectation that professionals would assist litigants in persons. In public law proceedings, this primarily appeared to be an expectation placed on local authorities or the solicitor for the children to provide a room or other remote assistance. No participant reported rooms being provided by the court for this purpose.

One practitioner reported being instructed by a Judge to set up a Skype meeting with two unrepresented parents before then spending most of the day on the phone to them, talking them through how to use Skype. This example indicates that representatives have gone above and beyond the usual requirement to support the court in cases where litigants in person are involved, such as by preparing bundles, preparing preliminary documents and drawing up orders (The Law Society Citation2015, para 32). Whilst in this case, it was not clear how the cost of this was met, the Law Society guidance (Citation2015) states that where providing assistance to the court gives rise to a significant expense to the lawyer or their client, the court should either direct the litigant in person to professional services or direct that the litigant bears this cost (para 33). Invariably, there may be potential benefits for represented clients in their lawyer providing such assistance to litigants in person, such as avoiding the time taken at hearings and the delays that may otherwise be incurred if the hearing needs to be adjourned because of the parties’ inability to use the required technology. However, this must not compromise a representatives’ ability to prepare for upcoming hearings on behalf of their own client. Further, in most cases, it is likely that such assistance will fall short of being a ‘significant expense’ meaning that legal representatives are not paid for this work.

It is well documented that litigants in person often struggle to comply with the procedural requirements of litigation (Trinder and Hunter Citation2015). The findings of this study indicate that practitioners perceive this has been exacerbated by the temporary closure of support services which are located at court buildings. One of the respondents from a court-based charity highlighted:

I had a client on Friday who was struggling. He has a mobile phone, he doesn’t have a computer, he’s not particularly computer literate. Previously he could come into the office with all his paperwork and we could try and sort him out. The judge is saying to him “well, you know, can you get to a library?” And well, given what he was asking him to do, I don’t think he could even do it himself, to be honest.

One of these respondents acknowledged that the courts had not been ‘forthcoming in providing us any additional space to enable us to see clients easily’. Given the finding that the judiciary has expected legal representatives to accommodate some non-client parties in their own offices, it is disappointing that the court has not put forward its own resources to facilitate this support to litigants in person, particularly as many court buildings in the North-East remain open but are not hearing cases in-person.

Experiences in the hearings

The Judicial College Equal Treatment Bench Book (Citation2021) acknowledges that ‘the aim of the judge should be to ensure that the parties leave with the sense that they have been listened to and have had a fair hearing – whatever the outcome’ (para 17). Unfortunately, several respondents perceived that this aim was not always achieved in remote proceedings.

One respondent identified a tendency of some judges to ignore the litigant in person and speak mostly with the representative of the other party. Explaining the impact on the litigant in person in one such case, they noted:

This guy was very upset afterwards, because he didn’t feel he’d the chance to even say anything. They’d done a deal with Cafcass and the solicitor before.

In another case, a respondent noted how a litigant in person had been cut off from the hearing because of technological difficulties, but the hearing proceeded in their absence. In such cases, it is vital that attempts to contact litigants through alternative channels are made to ensure that a litigant’s right to present their case are not compromised.

Examples were also given by four respondents of judges using technology to actively mute parties (and in one example, a representative). Reasons for this varied from the need to prevent background noise to ‘parents shouting and screaming in the middle of court hearings’. In one case, the Judge herself even noted concerns with this:

The judge ended up having to mute them, but she kept reminding herself that she shouldn’t really because if you’re in an active court you can’t just mute somebody.

In some cases, the respondents perceived that a Judge’s decision to mute a litigant was necessary in ensuring fairness for other parties and making effective use of the court’s limited resources. As such, they did not necessarily regard this as a Judge failing to demonstrate the ‘even-handed’ approach that is expected when dealing with litigants in person (Judicial College Citation2021, para 17). One support service volunteer discussed a case in which the litigant in person wished to offer evidence through an electronic dongle however the judge was unable to review the evidence at the hearing. In response, she perceived that the litigant became aggressive:

It was a District Judge and he really is very good, he was very tolerant. He really did his best but it just got past his patience level in the end. In the end all he said was “I’m going to mute you” and then the guy just put the phone down. He didn’t tell him he couldn’t stay on the line, he just said “I’m going to mute you”.

Whilst a Judge may take the view that muting parties is necessary where a litigant in person becomes aggressive, it may nonetheless have an impact on a litigant in person’s perception of justice and whether it has been achieved in their case. It is well documented that without the benefit of representation, litigants in person are not protected from their own emotions, which may adversely affect the way they conduct themselves throughout the proceedings, as in the example above (Re JC (Discharge of Care Order: Legal Aid [2015] EWFC B39). Whilst this is an issue which has preceded Covid-19, the respondents acknowledged that ‘it might not have gotten (sic) that far had we been in the courtroom’ because it may have been easier for a Judge to de-escalate the situation in person.

However, respondents also accepted that some judges have taken this approach because they considered litigants in person may not be taking hearings as seriously as those conducted in person. Examples were provided of unrepresented parties attending telephone hearings whilst in the supermarket doing their weekly food shop, on the toilet or audibly speaking to other people who should not be privy to the proceedings. The Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (, Citation2020b) set out similar concerns, demonstrating that this is a national, rather than regional issue. It is difficult to identify a solution to this problem, as it does not seem to be a result of a lack of information, with respondents to both research studies noting that warnings are provided to court users in advance and at the start of the hearing in line with the regional guidance (HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC Citation2020 para 2.5), but that these warnings are occasionally ignored.

Contact with children in care

Contact with children in care was a key issue for respondents involved in public law proceedings. Many discussed the initial difficulties with variations in contact following a sharp decrease in March 2020:

Direct contact that was to take place, especially for children that were in a local authority foster care arrangement, had just completely stopped. I know that quite a lot of people were having video contact like Facetime, but again, that was dependent upon the social workers because they would have to provide their telephone number to the client.

Although respondents acknowledged that contact arrangements were now progressing, issues with the frequency, quality and form of contact remained apparent for many, with a lack of available local authority venues being a major barrier to contact taking place on a more regular basis. The extent of this barrier varied depending on the age of the child and the local authority involved, with respondents reporting difficulties ranging from limited availability within venues due to cleaning schedules, to parents being prevented from having any physical contact with their children. Smith et al’s research (Citation2018) found that local authority spending on children and young people’s services in the North-east had decreased by at least 20% since 2010/11, leading to the closure of many children’s centres. This issue has no doubt been exacerbated by Covid-19 and the additional restrictions placed on venues to ensure social distancing and sanitisation procedures.

Respondents were mindful of the consequences for children in care placements and felt that this would impact on their overall welfare. They discussed that children were not only seeing their parents less, but that for significant periods of time since the start of the pandemic they had also been unable to see their friends or go to school, limiting their social networks and peer support considerably. Similarly to the second NFJO report (2020b), concerns were also raised about the impact of reduced contact on much younger children, specifically new-born babies, where indirect contact is not an option.

Respondents acknowledged that there remain difficulties with contact in cases where a staged reduction of contact was ordered following a care or placement order, reporting that this was much quicker or non-existent. One respondent gave the concerning example of parents being offered ‘30 minutes, next Friday and that’s it’ as a final pre-adoption contact, rather than the usual staged decrease. Regardless of the impact that Covid-19 has had on contact arrangements, it is difficult to see the humanity in a decision of this kind in circumstances when this will be the last opportunity for parents to spend time with their child.

Despite voicing concerns about the impact of this disruption on families, many felt that the disruption was, while distressing, inevitable and that it was best to avoid ‘flood[ing] the courts with applications where we know that, at the minute, there isn’t anything that we can do’.

The voice of the child

Respondents raised concerns about the ability to hear the voice of the child during proceedings. They noted that at the outset of the pandemic, face-to-face meetings with children stopped entirely and whilst this was gradually reintroduced in Autumn 2020, they are likely to have been stopped again during subsequent periods of lockdown. Overwhelmingly, respondents were negative about their experiences of meeting children remotely. They agreed that the quality of information obtained is often compromised, both because children are reluctant to engage and because professionals struggle to assess whether information provided is a free and genuine reflection of the child’s wishes and feelings. As such, they were concerned about the impact of remote assessments on the outcome of proceedings.

Interestingly, the Family Justice Young People’s Board has expressed the alternative view that …

Whilst face-to-face meetings are very important, remote direct work does provide an extra positive option to children and young people. For some young people, this could feel a more comfortable and usual setting, it could be less intimidating, and it might allow a young person to be a bit more open as they are in their own space. It could also feel less intrusive than a worker going into school (Cafcass , Citation2020c)

This was considered by Cafcass as part of their protocol on returning to in-person work with children. While ultimately, like the majority of respondents, Cafcass staff felt strongly in support of a return to in-person work, given the risks associated with new variants of Covid-19, the default position that at least one in-person meeting should take place with a child has currently been halted, with face-to-face work only taking place where it is considered to be essential and safe for all involved (Cafcass Citation2020c).

Conclusions

The dominant use of remote hearings, remains, at the time of writing in May 2021, part of the day-to-day working of the family courts. In the President’s most recent guidance (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021), issues of remote working remain at the forefront of the family law landscape, with emphasis on the importance of the findings of the NFJO reports and the wellbeing of practitioners at the coal face. With a period of ‘enhanced provision of remote hearings’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021, paragraph 2) ahead, it is increasingly evident that ‘the need to maintain and enhance good practice with respect to the conduct of remote or hybrid hearings remains a priority for all professionals, court staff and judiciary’ (Courts and Tribunals Judiciary Citation2021, paragraph 3) for the foreseeable future. In reality, the remote court is needed at this time, but the importance of safeguarding access to justice for court users and mitigating the impact on litigants in person cannot be overstated.

Legislation and procedural rules

Access to Justice Act, 1999

Children and Families Act 2014

Children Act 1989

Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

PD3AA Family Procedure Rules 2010

PD12B Family Procedure Rules 2010

PD 12J Family Procedure Rules 2010

PD 36Q Family Procedure Rules 2010

PD 36R Family Procedure Rules 2010

PD 51V Civil Procedure Rules 2010

The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/445)

The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) (No2) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/909)

The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 (SI 2021/261)

Case Law

A Local Authority v The Mother and Others (Covid 19: Fair Hearing: Adjournment) [2020] EWHC 1233 (Fam)

A Local Authority v M {2020] EWFC 43

Coventry City Council v C [2013] EWHC 2190

Re A (Children) [2020] EWCA Civ 583

Re B (Children) (Remote Hearing: Interim Care Order) [2020] EWCA Civ 584

Re D-S (Contact with Children in care: COVID 19) [2020] EWCA Civ 1031

Re P (A Child: Remote Hearing) [2020] EWFC 32

RE Q [2020] EWHC 1109 (Fam)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Kim Holt and Professor Ray Arthur for their support and helpful comments during the writing of this article. The authors also thank their Research Assistants, Lauren Napier and Alexandra Taylor for their help in transcribing the interviews conducted during this research study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Journal articles

- Aliverti, A., and Seoighe, R., 2017. Lost in Translation? Examining the Role of Court Interpreters in Cases Involving Foreign National Defendants in England and Wales. New Criminal Law Review, 20 (1): 130–156 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2017.20.1.130.

- Barlow, A., 2017. Rising to the Post-LASPO challenge: how should mediation respond? Journal of social welfare and family law, 39 (2), 203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2017.1306348

- Hoover, R. and Koerber, A., 2011. Using NVivo to answer the challenges of qualitative research in professional communication: benefits and best practices tutorial. IEEE transactions on professional communication, 54 (1), 68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2009.2036896

- Hunter, R., Barnett, A., and Kaganas., F., 2017. Introduction: contact and domestic abuse. Journal of social welfare and family law, 40 (4), 401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2018.1519155

- Johnson, D., Scheitle, C., and Ecklund., E., 2019. Beyond the in-person interview? How interview quality varies across in-person, telephone and skype interviews. Social science computer review, 089443931989361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319893612

- Kaganas, F., 2017. Justifying the LASPO act: authenticity, necessity, suitability, responsibility and autonomy. Journal of social welfare and family law, 39 (2), 168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2017.1306345

- Naderifar, M., Ghaljaei, F., and Goli, H., 2017. Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research strides. Development of medical education, 14 (3), 1.

- Richardson, K. and Speed, A., 2019. Restrictions on legal aid in family law cases in England and Wales: creating a necessary barrier to public funding or simply increasing the burden on the family courts? Journal of social welfare and family law, 41 (1), 135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2019.1590898

- Speed, A., 2020. Just-ish? An analysis of routes to justice in family law disputes in England and Wales. The journal of legal pluralism and unofficial law, 52 (2), 276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2020.1835220

- Speed, A., et al., 2021. Covid-19 and the family courts: key practitioner findings in applications for domestic violence remedy orders. Child and family law quarterly, 33 (3), 215–235 .

- Speed, A., Richardson, K., and Thomson, C., 2020. Stay home, stay safe, save lives: an analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on the ability of victims of gender-based violence to access justice. Journal of criminal law, 84 (6), 539. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018320948280

- Trinder, L. and Hunter, R., 2015. Access to justice? Litigants in person before and after LASPO. Family law, 45, 535.

Books

- Aliverti, A., and Seoighe, R., 2017. Lost in Translation? Examining the Role of Court Interpreters in Cases Involving Foreign National Defendants in England and Wales. New Criminal Law Review, 20 (1): 130–156 doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2017.20.1.130.

- Given, L.M., 2016. 100 questions (and answers) about qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Urquhart, C., 2013. Grounded theory for qualitative research: a practical guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Reports and websites

- Aliverti, A., and Seoighe, R., 2017. Lost in Translation? Examining the Role of Court Interpreters in Cases Involving Foreign National Defendants in England and Wales. New Criminal Law Review, 20 (1): 130–156 doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2017.20.1.130.

- Cafcass & Women’s Aid, 2017. Allegations of domestic abuse in child contact cases. Available from: https://www.cafcass.gov.uk/news/2017/july/cafcass-and-women%E2%80%99s-aid-collaborate-on-domestic-abuse-research.aspx 17 Mar 2021

- Cafcass, 2020a. Advice for parents and carers on Covid-19. Available from: https://www.cafcass.gov.uk/covid-19/advice-for-parents-and-carers-on-covid-19/ 17 Mar 2021

- Cafcass, 2020b. Private law data. Available from: https://www.cafcass.gov.uk/about-cafcass/research-and-data/private-law-data/ 17 Mar 2021

- Cafcass, 2020c. Organisational guidance on working with children through Covid-19 A guide to direct contact with children and families, working in the office, and attendance at court, Cafcass. Available from: file:///C:/Users/CYLT4/Downloads/Guidance-on-working-with-children-during-COVID-19-February-2021.pdf 17 Mar 2021

- Court and Tribunals Judiciary, 2020a. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update from the lord chief justice. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/announcements/coronavirus-update-from-the-lord-chief-justice/ [ Accessed 17 March 2020].

- Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, 2020b. The remote access family court. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-Remote-Access-Family-Court-Version-5-Final-Version-26.06.2020.pdf [ Accessed 26 June 2020].

- Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, 2020c. The family court and Covid-19: the road ahead. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/announcements/the-family-court-and-covid-19-the-road-ahead/ 17 Mar 2021

- Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, 2020d. Coronavirus CRISIS: guidance on compliance with family court child arrangement orders Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/announcements/coronavirus-crisis-guidance-on-compliance-with-family-court-child-arrangement-orders/ 17 Mar 2021

- Courts and Tribunals Judiciary, 2021. The family court and Covid-19: the road ahead 2021. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Road-Ahead-2021.pdf 17 Mar 2021

- Department of Education, 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19): guidance for children’s social care services. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-for-childrens-social-care-services/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-for-local-authorities-on-childrens-social-care#courts 17 Mar 2021

- Foster, D., and Loft, P., 2021. Coronavirus: separated families and contact with children in care FAQs (UK). House of Commons Library Briefing Paper no. 8901. London, House of Commons Library. Available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8901/ 17 Mar 2021

- HHJ Hudson and HHJ Matthews QC, 2020. Interim practice guidance (4) for Cleveland, Durham and Northumbria DFC, 7 April.

- HMCTS, 2021. HMCTS weekly operational summary on courts and tribunals during coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/hmcts-weekly-operational-summary-on-courts-and-tribunals-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak#family 15 Nov 2021

- Judicial College, 2021. Equal treatment bench book. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Equal-Treatment-Bench-Book-February-2021-1.pdf 17 Mar 2021.

- Ministry of Justice and HM Courts & Tribunal Service, 2019. Response to fit for the future: transforming the court and tribunal estate. London, Ministry of Justice. Available from: https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/transforming-court-tribunal-estate/ 17 Mar 2021.

- Ministry of Justice and National Statistics, 2020a. Family Court Statistics Quarterly: april to June 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/family-court-statistics-quarterly-april-to-june-2020/family-court-statistics-quarterly-april-to-june-2020 17 Mar 2021