ABSTRACT

Central government is transferring increasing discretionary powers for social security to local authorities (LAs) in England. The responsibility for the design, implementation, and oversight of a series of ad hoc, cash-limited, and discretionary schemes marks the latest evolution of LAs role in the welfare system. Yet there has been little empirical analysis of how LAs design one of the latest schemes in the localisation process – local welfare assistance. This article draws on a content analysis of 165 LA webpages and 10 interviews with LA and third sector members to explore the design of local welfare assistance schemes and the factors that play into these ‘design decisions’. It is argued that LAs play a significant role in shaping the social security environment. This level of governance represents a site of analysis that can tell us about the environment that street-level bureaucrats work in and the schemes that citizens will experience. However, because of exhaustive demand and ever reducing resources LAs are unable to design in a way that promotes administrative justice. Instead, practices that limit, ration or delegating demand and resources leave claimants with inaccessible, unavailable, and discriminating local welfare.

Introduction

At the height of the Conservative-led Coalition era, Dawn Martin, a 62-year-old homeless woman applied to the Isle of Wight’s Local Welfare Assistance (LWA) Scheme as a last resort after her application for emergency housing was rejected (Butler Citation2013). This Local Authority (LA), like many others, had decided that its new fund, localised in 2013 after the abolition of the Social Fund, should offer only limited support. In response, the Council offered Dawn a voucher to enable her to buy a tent, in lieu of providing housing. In the words of the LA:

During our discussions with her we did - as a last resort which we accept is far from ideal - offer her vouchers with which she could, at the very least, buy a tent as a temporary shelter but she declined this. (Isle of Wight Council quoted in Butler Citation2013)

Over ten years on, Dawn’s experience continues to reflect many of the concerns that plague the localisation of discretionary social security schemes. It continues to be the responsibility of a LA to design, implement and oversee local welfare schemes, most notably LWA, Discretionary Housing Payments, Council Tax Support and the Household Support Fund. This is the latest evolution of LAs’ role in the welfare system, within which senior LA posts have previously morphed to embrace different functions, from administrators of personal social services to professional managers of local welfare services (Neve Citation1977, Brenner Citation2004, Evans Citation2011). Yet, there has been little empirical analysis of the evolving role of LAs in light of extensive localisation of welfare responsibilities (see: Meers Citation2019, Hick Citation2022, McKeever et al. Citation2023).

This article explores the decisions local actors are taking on the design of local welfare schemes and attempts to analyse the factors influencing these ‘design decisions’. With a focus on design in meso-level bureaucracies, which sit between street-level and central-level bureaucracies. To do so, it explores a series of questions posed by Dawn’s experience. First, is Dawns case reflective of how local schemes have been designed by LAs across England? Second, what factors play into the exercise of discretion in design decisions? For instance, why was it decided that the Isle of Wight’s scheme would offer vouchers and not cash? Finally, what is the impact of localised design responsibilities on the ability of claimants to access the schemes?

This article is divided into three parts. The first discusses the shift to a growing reliance on local discretionary social security funds and provides an overview of LWA. Before suggesting the merits of shifting the focus of discretionary scholarship from how discretion is exercised in schemes designed centrally to how discretion is used to design schemes at the meso-level. The second outlines the methods used in an empirical study of the design of LWA across England. The third discusses the central themes that emerged from the way that LAs designed components of the LWA schemes, for instance eligibility criteria, application processes and types of support offered. It is argued that from a meso-level perspective LAs and actors engage in engage in the architecture of social security provision security provision – they plan, design, and oversee the construction of schemes and their implementation. This significant role in shaping the local social security environment is distinct from their usual backseat role in welfare design in which payments are administered by central government agencies based on centrally determined policy. However, in the face of inadequate resources and untenable demand, LAs have been unable to fulfil this role: only able to design, install and maintain a series of limited schemes.

Shifting Perspectives: Discretion and Design in Local Welfare Assistance

The implementation of the 2013 ‘localism agenda’ by the Conservative and Liberal Democrat Coalition Government, informed by a desire to devolve local autonomy with ‘new freedoms and flexibility’ (Department for Communities and Local Government Citation2011, p. 18) to local government, resulted in the latest change to the ‘degree of discretion that local authorities have from central government’ (Pratchett Citation2004, p. 363). The rhetoric and practice of localism has continued to attract significant support from the successive Conservative-led Governments. It has been argued that this localist rhetoric represents the emergence of a new political philosophy (Eagle et al. Citation2017, p. 57) and a fundamental restructuring of local government (Kjellberg Citation1995, Meers Citation2019). Whether this is a contemporary restructuring or a resurgence of localised ‘poor relief’ (Glennerster Citation2020), LAs are nevertheless operating new decision-making powers and responsibilities under reconstituted central-local relationships.

The potential negative implications of localism, for instance its ‘tendency to disadvantage socially marginalised groups’ (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2020, p. 542), are heightened by central governments pursuit of ‘austerity’, a policy which promotes its own ideals of decision-making – so-called ‘austerity governance’ (Daly et al. Citation2023). To address the challenging inherited fiscal environment, the Coalition Government made fast and deep cuts to public services (Office for Budget Responsibility Citation2016). Shrinking the state as a provider of welfare (Hetherington Citation2010, Keep Citation2011). LAs picked up a disproportionate share of these cuts in a process of ‘austerity localism’ (Featherstone et al. Citation2012, Lowndes and Pratchett Citation2012, Clayton et al. Citation2015). Between 2009/10 and 2019/20 central government grants were cut by 40% in real terms, and from £46.5 billion to £28.0 billion at 2023/24 prices (Atkins and Hoddinott Citation2023). The resource constraints are compounded by rising demand for services as a result of the fallout of punitive welfare reforms, the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis. Unsurprisingly, LAs have been managing scarce resources by cutting back on non-statutory obligations (Wills Citation2020, p. 819), of which LWA is one.

Central to debates on localised welfare is the proliferation of discretionary-based local benefits which progressively underpin and complement the centrally administered entitlement-based system (Handscomb Citation2022, p. 3). The last decade in England has been characterised by a so-called ‘cut and devolve approach’ (Meers Citation2019). Central government has delegated power to LAs to formulate and administer a series of cash-limited schemes on a discretionary basis to ‘top-up’ social security entitlement from central government (Meers Citation2019, p. 41). LAs have the discretion to make (or refuse) awards, with reference to varying degrees of guidance and legislation, but all confer sizeable discretion to manage the administration and awarding of these life-line payments. The main three locally administered schemes – Discretionary Housing Payments, Council Tax Support, and LWA Schemes – were intended to act as ‘the safety net beneath the safety net’ to ‘prevent escalation of crisis’ (Charlesworth et al. Citation2023, p. 58). More recently, the time-limited Household Support Fund marks the Governments flagship response to the cost-of-living crisis (Meers et al. Citation2024). These changes ‘significantly elevate the role played by English councils and other local actors in determining the scale, nature and generosity of the emergency help available to impoverished and vulnerable groups’ (Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2020, p. 550). However, third sector organisations (TSOs) have criticised the schemes for producing postcode lotteries of ‘collapsed’ (Child Poverty Action Group Citation2022), ‘hollowed out’ and ‘eroded’ support (Porter Citation2019).

LWA is one of the latest policies in the localisation process. The discretionary element of the perfunctory national Social Fund responded flexibly to exceptional and emergency need through the provision of small one-off payments or loans. To mitigate the abolition of this centralised scheme (Batty et al. Citation2015 Section 70(1)) funding was devolved to upper-tier LAs (Unitary Authorities, Metropolitan Districts, London Borough, and County Councils) in England and devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales. This was legitimated by suggestions that LAs are those ‘who understand their communities and who are best placed to make the right call’ (HL Deb, 20 November 2017). Central government did not provide statutory guidance on how the schemes should operate or establish reporting requirements for provision. Funding, although ring-fenced until 2015/16, is now merely identified as a notional amount in the Revenue Support Grant as part of the LA’s Financial Settlement. In 2021, English LAs were allocated a notional £131 million for local welfare, which one local government source dubbed ‘ghost money’ because there is no obligation on LAs to ‘spend their theoretical share of this theoretical sum on helping the poor’ (Butler Citation2015). This is less than half the £330 million value of the pre-2013 centralised Social Fund. However, since March 2020, and the rise of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Central Government have made available over £2.5 billion of Household Support Funding to County Councils and Unitary Authorities in England to support households who are most in need of crisis support and may not be eligible for other government funds (Department for Work & Pensions Citation2020, p. 1). In some cases, the funds have been maintained as a distinct Household Support Fund, providing help with food, energy, water bills and essentials, in others the funds have been diverted into LWA schemes (Meers et al. Citation2024). Whether this temporary fund continues remains to be seen. It is important to note that most of the welfare framework remains nationalised, even after the localisation of these crisis funds, but it has been argued that the combination of the localism agenda, austerity programme, and welfare reform has ‘shifted the place of social security in society’ (Meers Citation2014, p. 83).

What emerges is a fund designated by central government as being available to households in emergency situations and as a means of taking up the shortfall from the abolition of centralised crisis support. The three central features of the Social Fund (cash limited, discretionary, and no right of appeal) are joined by a fourth (local). The Government announcements suggest that the Coalition Government were seeking to provide ‘flexibility’ to those ‘in greatest need according to local circumstances’ but ‘the key implicit message was that the [Social Fund] was costing too much’ (Grover Citation2012, Steven Citation2012, Meers Citation2019, p. 54). This leaves LAs responsible for meeting ad-hoc and unpredictable needs with much reduced funds. Particularly because central government has largely absented itself from any direct involvement in the provision of these so-called ‘difficult-to-deal-with’ funds (Grover Citation2014, p. 314). Some say this is an act of ‘policy dumping’ (Maclennan and O’Sullivan Citation2013, Costa-Font et al. Citation2013) or ‘blame avoidance’ (Meers Citation2019) for the fallout of the 2012 welfare reforms. This move to localism without central oversight or adequate funding, unsurprisingly but contrary to some suggestions (Hick Citation2022), was predicted to render LWA ‘equally, if not more problematic than the Social Fund administered by central government’ (Grover Citation2012, p. 349).

In the localism context, LAs actors have been given considerable discretion to design local welfare systems rather than just decide how provisions and powers might be interpreted. Here, Dworkin’s (Citation1977, p. 77) original doughnut analogy, which illustrated decision-making and implementation in two discrete stages where higher authorities make decisions about policies and governmental agents are responsible for implementation, is supplanted with that of a tripartite system. Think more sandwich than doughnut. The sandwich analogy is most reminiscent of Evans (Citation2016) argument that professional discretion had a role in ‘structuring and informing’ front-line practices. Hence ‘discretion permeates organisations, including at senior management level. It is not simply located at the end of the chain of implementation but at points all along it’ (Evans Citation2010, p. 611). This work has raised the profile of the multi-layered and dispersed nature of discretion, encouraging an approach to policy implementation ‘beyond street-level bureaucracy’ (Evans Citation2010) and represents a shift from macro-micro analyses of discretion in public bureaucracy to an appreciation of the meso-level.

So far, however, the literature on social welfare services has failed to evoke an updated understanding of perspectives other than managerialism, such as localisation which has enhanced the role of meso-level bureaucracy. It has, therefore, also overlooked the evolution of different activities, such as design. The intersection between administrative justice and design was explored by Mashaw (Citation1983) in Bureaucratic Justice. In which he contended that, although the first instance decision is made by one decision-maker, the way that a decision process is designed instructs the final decision (Mashaw Citation1983, p. 125). More recently, there is an increasing interest in the study of design as an important socio-legal phenomenon (see: Bondy and Le Suer Citation2012, Ball Citation2014, Donson and O’Donovan Citation2016, Ryan Citation2021). However, when it comes to the design decisions of LAs – the literature is sparse. This is important because, in the case of LWA decision-making, central and street-level administrations sit at either end of the ‘chain of implementation’, while LA-led design decision-making operates in the middle. It is, therefore, necessary to consider the shift from how discretion is exercised in scheme designed centrally to how discretion is used to design schemes in LAs.

In the following sections, this article goes ‘above and beyond’ street-level or managerial conceptions to approach the design and administration of local welfare from a meso-level perspective, to consider the role of meso-level bureaucracy which sits above the street-level actors and engages in activities beyond management, in particular the design of LWA schemes.

Methods

To explore how local welfare schemes have been designed across England, I conducted a content analysis between January and March 2023 of webpages which advertise and administer LWA. These were identified using End Furniture Poverty’s ‘Welfare Assistance Finder’, which links directly to the LA websites. This was supplemented with simple google searches where necessary to find any webpage or section about LWA on a LA or third-party website. The sample included 152 upper-tier LA websites, of which there were 24 County Councils, 33 London Boroughs, 36 Metropolitan Boroughs, and 59 Unitary authorities, and 13 webpages hosted by third party organisations. This captured all 165 LWA webpages across England. The Coalition Government proposed that several elements were key to local provision – scheme status, eligibility criteria, types of support, application process, accessibility, funding, and organisational arrangements – any mention of these were recorded, manually coded, and analysed thematically. The limitation to this method is that these webpages were curated to reflect a version of the schemes that the LA wants to promote. This means these webpages can only be taken as a representation of the scheme design, they cannot, for instance, tell us how the schemes operate in practice. Nevertheless, there is value to understanding how LAs think of these schemes, how they choose to design them and what they feel is appropriate to publicly advertise.

In order to explore the practice around the design of LWA schemes, interviews (approved by Oxford University’s CUREC Ethics Committee)Footnote1 were conducted between June and August 2023. Interviewees included one LA Councillor, four LA civil servants, two third sector members, and three national advocates. They were recruited in two streams. First, two schemes were selected based on having an open LWA scheme, different geographical locations, different political control, and whether online meeting minutes were available (for insight into the historical development of the schemes 177 minutes referencing LWA were also analysed). LA and third sector members were identified from their involvement in these two LWA schemes. Second, experts from national advocacy organisations were identified and interviewed to complement the local perspective with a more national take. The interviews were semi-structured, with topics including: (i) how the local welfare scheme was, and continues to be, designed, (ii) the reasons for these design decisions, (iii) interviewees reflections on the success of LWA in meeting local needs. These questions were generalised for the three national advocates. All interviews were conducted remotely via Microsoft Teams and lasted between 45 minutes and one hour. Each interview was audio-record and then transcribed. These transcripts were then analysed thematically, common themes were identified and coded manually. The following sections discuss the key themes that emerged from the data.

Findings

Scheme closures

LAs are transferred two forms of discretion in relation to LWA schemes. The first is the discretion to decide whether or not to operate a scheme. This relocates the power to set social welfare priorities from its usual position in central government to the localities, where local decisions can be made based on local priorities. However, the content analysis suggests that this is not necessarily working in favour of claimants. Only 124 (75%) schemes were open at the time of this analysis. Significantly, 41 (25%) of the total sample were closed because a scheme had never been set up or the scheme was closed after a period of offering support.Footnote2 The absence of formal crisis support in 41 LAs has the potential to create significant geographical inequality through uneven distribution of, and access to, emergency funds.

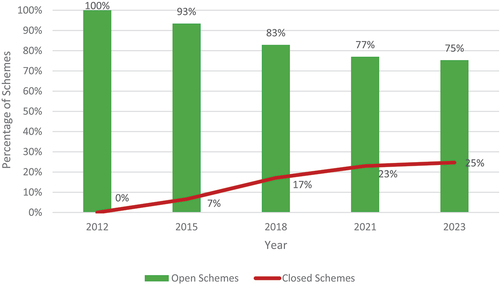

There is an obvious trend of closures across the UK. TSOs have conducted sustained freedom of information requests over the past ten years, which detail the number of ‘closures’ each year. displays a consistent reduction in open schemes (see: Aitchison Citation2018, Nichols and Donovan Citation2021, Citation2022, Bond and Donovan Citation2022). If this trend continues the principles of equal access to justice may be violated in more authority areas. It is noticeable that between 2021 and 2023 fewer closures took place. Unusually, one LA, Haringey Borough Council,Footnote3 appears to have reopened their scheme. This anomaly is perhaps a reflection of pandemic conditions in which exceptional funding was distributed through the Household Support Fund, and represents the positive affect additional resources can induce.

Chart 1. Status of schemes in England between 2012 and 2023 n = 152.

The reasons for these closures were not publicised on the LA webpages, where a scheme had closed it was evident merely from the absence of a dedicated webpage. When discussing the difficult choice of whether or not to maintain a LWA scheme in practice, Interviewee Four, a LA councillor, stated: ‘you know, there wasn’t much argument about discretion to be had’. By stating that there was no such argument to be had, the interviewee suggests that although a decision was made, it was not necessarily one that was based on a determination of local priorities. Rather, it was the only decision that could be made in the circumstances. Here, the interviewee brings to the fore the challenges associated with managing discretion in a system bounded by central control of funding and suggests the dulling effect that the strictures of financial cuts had on LA discretion.

Eligibility criteria

After the decision to maintain a scheme, interviewees discussed the difficult decisions in the second type of discretion: designing components of the schemes. The regulatory environment in which these decisions were made was sparse since LWA was localised without statutory guidance or reporting requirements. As Interviewee Two, a LA officer, aptly put it:

Theres no criteria at all for what we do. We can just pick and choose for what makes sense for us completely. We set out own criteria for the people that are coming in and if you look on our website, you can see exactly what that is.

Here the interviewee highlights the wide discretionary space that has been transferred to LAs to make decisions, as the localism agenda intended. It is this idea, that LAs are transferred freedoms to design criteria without constraint, which is often promoted by central government to justify the localisation of responsibility. However, as discussed in the preceding section, discretion in theory and discretion in practice often take different forms. This is explored and questioned in the following sections, beginning with an examination of eligibility criteria.

The content analysis revealed that three criteria were, broadly speaking, routine across localised schemes. Although, typically, localised welfare schemes are criticised (in comparison to national universal schemes) for their geographical variability (Edmiston et al. Citation2022, Meers et al. Citation2024), there is a surprising consistency across a number of criteria. First, there was a standard criterion that the claimant be on a low income; 122 (98%) open schemes included a requirement for an individual to be on ‘low income’ or ‘in receipt of benefits’. Significantly, the use of ‘in receipt of benefits’ criteria reflects the recognition that centralised social security is not sufficient for people to build a financial buffer for times of crisis (Aitchison Citation2018). The use of benefits in eligibility criteria has been controversial in the past because it can be overly prescriptive and exclude those in-work on low incomes. This rigid routinisation of eligibility rules therefore has the potential to exclude certain vulnerable groups because of a failure to individualise the provision of discretionary support and consider the complex lives of claimants or the changing financial environment. Which is particularly concerning because the COVID-19 pandemic has brought a new profile of people to the benefit system, who may not qualify under these routine criteria. As one interviewee, a third sector member, noted:

We were seeing a new profile of people. This was in April 2020. Immediately we saw a new profile of people. We were seeing people who had never accessed the benefits system before, didn’t have a sense, didn’t have a clue how to navigate it, felt really embarrassed, had been earning good salaries and coming to [local welfare assistance] for crisis help. … Look, this is completely different. Homeowners are now coming to us, you know, which was unheard of.

The interviewee raises the issue of supporting claimants through unfamiliar terrain while in an already stretched administrative deficit. Illustrating this, another interviewee, a LA officer, stated: ‘Our toolbox I guess is quite limited in terms of the growing group that we had previously never really had to support in this way’. (Participant Three). In this regard, they expressed the challenge to make space for this new class of claimants in an already overcrowded environment

Second, the content analysis found that 106 (85%) open schemes expect claimants to have a ‘local connection’. This criterion does not come as a surprise given these schemes were intended to be operated in distinct and bounded LA areas. There are, however, problems surrounding adequate and clear definitions of local connection, for example the time required to have lived in the administrative boundary varies. Durham County Council called for residency for three months within the last 12 months,Footnote4 while Barnet Council required at least 6 weeks.Footnote5 Whereas, others, including Medway Council,Footnote6 are stricter requiring residency for at least 12 months. The extent of local connection also varies, Lancashire County Council’s Scheme uses complex language and states you ‘must live within the administrative boundary of Lancashire County Council’,Footnote7 Barnsley Council creates restrictive criteria by asking that the claimants must be ‘living in Barnsley and be a tenant, joint tenant or owner occupier’ and in doing so excludes the homeless or those in refuges.Footnote8 South Gloucestershire Council loosens the criteria to those ‘living in or looking for a home in South Gloucestershire’Footnote9; and a further 78 (63%) schemes reference a local connection requirement without defining exactly what that means. This raises concerns that geographically mobile communities, such as gypsy and traveller communities, or people fleeing abuse, including people escaping domestic abuse, will be excluded.

Some LAs do provide exemptions, for instance Cambridgeshire County Council state ‘you can also apply if you have fled to the area for your own safety’.Footnote10 But these focus on people fleeing domestic violence, to the exclusion of other groups, and even those exemptions are not universally used. The standardisation of exclusionary local connection criteria has the potential to exclude vulnerable people who are mobile or between administrative boundaries and creates a postcode lottery for those travelling between boundaries, because of the financial and political incentives to restrict the local to the local (Turner Citation2019, Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2020).

Thirdly, 26 (21%) LAs outline and define characteristics of the people to be prioritised when awarding funds. These basic vulnerability criteria are generally agreed upon as standard by LAs but there are often differences in the precise definitions. Take for instance Thurrock Council’s definition of ‘frail elderly people, particularly those with restricted mobility or who have difficulty in performing personal care tasks’Footnote11 in comparison to Haringey Council who more generously included ‘households with elderly residents (over 70)’.Footnote12 The basic expectation that older people are vulnerable is consistent across LAs, but the definition of being ‘elderly’ differs. This variability of criteria could cause confusion and obscurity for claimants who may be unsure whether they fit the ‘category’. Here, uncoordinated routinisation across administrative boundaries causes unnecessary variation in practice. Thus, while there is more consistency in the broad criteria across LWA schemes in England, a closer analysis shows that details and definitions within the criteria vary.

Exclusions from eligibility

Eligibility criterion, found in the content analysis for this article, were also found to be commonly constrictive, through interpretations of need (circumstances and vulnerability), exclusion of benefit sanctioned claimants, requirement to seek help elsewhere, and exclusion dependent on immigration status. In regard to interpretations of need, the study found that 91 (73%) LAs with open schemes clearly outline eligible circumstances, classed as ‘crisis’, ‘emergency’ or ‘disaster’, warranting support. The majority of LAs support only a small number of circumstances; often that are deemed to be sufficiently different from those ‘typical’ situations caused by low income. For instance, 82 (90%) LAs support claimants to set up or remain in the community (e.g. after leaving hospital, care home, prison, army, or a period of homelessness) and these LAs are particularly keen to uphold community care. Additionally, 55 (60%) provide support to crisis situations that threaten health and wellbeing (usually a natural disaster or risk of abuse), the focus in these situations is the exceptional nature of the situation. For instance, Sandwell Council define eligible circumstances as: ‘to meet a need that has arisen as a consequence of an emergency, disaster, exceptional circumstances or a pressing need that is strikingly different from the pressures generally associated with managing a low income’.Footnote13

In contrast to community care and crisis situations, support for circumstances outside of this norm, for example victims of crime, benefit concerns, employment issues and risk of eviction, are covered by less than 14 (11%) LAs with an open scheme. Six (5%) open schemes excluded situations where items or money have been lost or stolen. Their reasoning is evident in the two examples that follow. Redcar and Cleveland Council state they will not provide support ‘[w]here the crisis has solely arisen due to the loss, theft or misplacing of money. This is due to difficulties in verifying these factors’.Footnote14 In a similar vein but with a more overt moral overtone Redditch Council states ‘[t]he applicant must accept some responsibility for taking care with their monies’.Footnote15 It was unusual to find eligibility circumstances that were more flexible to situations deemed ‘undesirable’, such as those offered by Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council for ‘children at risk of being taken into care’,Footnote16 or Worcester City Council which included support for those ‘experiencing exceptional financial difficulty, e.g. due to being the victim of robbery/burglary, or having significant unexpected expenditure’.Footnote17 In moralising the criteria for LWA some LAs exclude citizens without adequately checking their individual circumstances, reducing the discretionary nature of a supposedly discretionary scheme. Here, the discretion to design is shown to be different from the discretion to supply.

In regard to benefit sanctions, the content analysis of the authority webpages found that 16 (13%) LAs explicitly exclude claimants who are subject to a sanction. For instance, Wigan Council note the following:

Reasons you may NOT be able to apply for welfare support; Have you had your benefits stopped because of a sanction? … because they are subject to a benefit sanction and have not applied for a hardship payment from DWP; subject to a sanction from DWP and an award will undermine a sanction.Footnote18

The exclusion of claimants subject to benefit sanctions is particularly problematic, especially because many decisions on Universal Credit sanctions are made without reference to individual circumstances by automated systems used to process claims. In doing so they penalise those most in need, for instance a third sector member recounted the following:

You know, people are sanctioned because the computers says no. They don’t look at the individual’s circumstances. We had one dad with four kids whose wife had passed away. And he was having to move home because their children were so desperately sad that, you know that’s where the mum had died. So, the dad couldn’t go to his meeting at the job centre because he was organising the move and you know he has four kids and just been widowed, and he was flipping sanctioned. So, I mean it’s like this is counterproductive. When you don’t have a lot of money the minute you kind of default on something very quickly that will spiral.

In this case, the interviewee went on to say that the claimant was able to access LWA, yet has he been in one of the 16 LA boundaries that exclude those sanctioned then he would have had to go without. This example represents the complexity of meso-level bureaucrats’ position, having to simultaneously manage the expectations of central government and the need of local people suffering under the centrally constructed policy, while they design their own schemes. It is this position that distinguishes the meso-level from other levels.

One reason given for the design of eligibility exclusions was the replication of central government policy decisions. In an interview, a former LA Councillor was asked about how policy was designed, and they suggested that some LAs took central government guidance literally and implemented it as policy: ‘I suspect these things would have very well have been on briefing documents that came from the [government] … and councils just take just take it and say right ok we’ll do that’ (Participant Four). In doing so, LAs replicate central government priorities, rather than making their own local assessments of need. Therefore, failing to act as a mitigator for the fallout of centrally designed policies, as in the case of benefit sanction exclusions.

However, a few authorities do include claimants that have been subjected to a benefit sanction, bending the rules that are imposed by central government. In doing so, the authority instils a sense of flexibility, making space for considering individual situations in the exercise of discretion. For instance, Sandwell Borough Council state:

People subject to certain disallowances or sanctions … will not normally be eligible for support. However because of the nature of benefit sanctions each case will be considered on its own merits and where it is clear that failing to provide support would present significant risk to the claimant.Footnote19

This best represents the power of LA discretion, to design schemes that allow for a holistic and contextual decision-making process. One that diverts from central government, and in doing so meso-level bureaucrats design differently.

A further routine restrictive criterion is the exclusion of situations that are deemed ‘self-imposed’. An example would be Hounslow Council who state:

Applications may be considered if an emergency or a disaster is not a consequence of an act or omission for which the customer or his/her partner is responsible, and the customer or his/her partner could not have taken reasonable steps to avoid the emergency.Footnote20

This approach ignores the barriers that claimants may have faced in avoiding so-called ‘self-imposed’ situations, while also responsibilising the claimant, instead of the LA, which has been found in studies of welfare conditionality to initiate negative behaviour changes, including ‘begging, borrowing and stealing’ (Dwyer Citation2018, pp. 150–154), and disengagement with support (Batty et al. Citation2015).

Finally, people with no recourse to public funds are routinely excluded from LWA schemes. For example, content analysis of webpages demonstrated that 39 (31%) open schemes explicitly exclude those subject to immigration control. This ‘blanket policy’ within LAs has the potential to routinely exclude particularly vulnerable groups from receiving last resort support. Only seven (6%) LAs with open schemes explicitly state that they are open to those with no recourse to public funds. However, even those schemes that are more inclusive usually qualify this criteria on the basis that it does not interfere with central government policy. For example, Wandsworth Council states: ‘The WDSF (Wandsworth DSF) is part funded through government grants that are not considered “public funds” therefore it is available to households who have no recourse to public funds’.Footnote21 Again, the difficult position of LAs is highlighted, walking the tightrope between central government requirements and local need.

LAs that employ these restrictive and confining eligibility criteria create a bounded framework that automatically includes or excludes groups of people. This practice serves to reduce demand by targeting the scheme at those most in ‘need’ but also reduces the discretionary space of meso-actors by creating a rule heavy framework. In combination, these limiting eligibility criteria fall onto the most vulnerable communities and force on them a double insecurity crisis.

Types of support available

The analysis of webpages outlined common decisions made by LAs in relation to the types of support offered. Firstly, there has been a clear movement away from offering cash as the default (cash-first) towards in-kind support. The benefits cash-first approaches have been identified as flexibility, convenience, freedom of choice, preservation of dignity and administrative efficiency (Whitham Citation2020, Trussell Trust Citation2022). However, the content analysis demonstrated that only 12 (10%) LAs offer cash as an option alongside in-kind methods of support, and only five (4%) LAs offer a cash-first approach.

The content analysis demonstrated that most LAs chose vouchers, pre-payments cards or a specific furniture item over cash awards. However, there is widespread criticism that this form of support can disempower the claimant and fail to provide adequate provision (Nygård et al. Citation2019, Gardiner Citation2019, Watts Citation2020). Similar concerns were expressed by Interviewee Six (a national advocate):

You’re basically buying food because the donation goes to buy food, then pass the food to somebody that might not be able to, you know, it might not be culturally appropriate, it’s awful to say they might not like that food, and then it’s wasted. It’s like if it just cost you £30 to buy that food, just give the person £30. It’s just so cost inefficient. It doesn’t make any sense whatsoever, but it’s happening on a massive scale and it’s infuriating.

The types of in-kind support are further restricted by limitations on what the award can be made for. A total of 109 (88%) LA webpages showed that they provide food, furniture/white goods, or fuel/utilities, but that fewer LAs offer support for broader needs. For instance, only 38 (31%) schemes offer support for clothing or travel expenses. LAs further restrict the types of support covered by detailing a list of available and unavailable items. These appear to serve two purposes: to limit the number of applications and to control what is deemed by the authority to be ‘necessary’ items for claimants. These are often contradictory between LAs, but common exclusions include (but are not limited to): holidays, television, telephone, work or school related expenses, removal expenses, motor vehicle costs, court costs, domestic assistance and respite care, debts, mobility needs, self-employed expenses, retrospective needs, medical services, and distinctive school uniform, to name but a few. These examples suggest that discretion is being exercised to discipline claimants.

Advertisement and applications

Interviewees highlighted the difficulty in having open and accessible schemes because of the fear of an onslaught of applicantions. For instance, much like Lipsky’s (Citation2010) analysis of front-line workers failing to disseminate information about the existence of welfare schemes as a coping mechanism, Interviewee One, a third sector member, reflected on the choice not to advertise:

What we cannot do is we cannot actively advertise [LWA] because resources are so limited. The [LA] say that if we advertise it, we’re going to be creating demand that cannot be met. So, in an ideal world, we would have resources that needed … because we can’t advertise, we just use our networks.

Similarly, the ease of access and simplicity of the application process is itself a method of promoting LWA, on the other hand, the use of onerous application processes is an effective method of supressing or rationing demand. LAs are employing application processes that, intentionally or otherwise, limit accessibility by offering singular application methods and rationing application assistance. Eighty-four (68%) LAs offer online application processes, and this is fast becoming the only route offered by some LAs. Just under 30% of LWA schemes now offer an online-only application process. Whereas only seven (6%) LAs take applications by post and just five (4%) support in-person applications. This is particularly detrimental to those in digital poverty, who do not have the resources or physical ability to access or interact with online platforms, who are then unable to access LWA (Digby et al. Citation2022). In doing so, the most marginalised and vulnerable groups are often excluded from crisis support. But it is also detrimental to the digitally disadvantaged who may not fall into the vulnerable categories, such as the elderly middle class with no computer skills.

The content analysis also found that LAs appear unwilling or unable to offer assistance to applicants that require additional support. Instead, there is an emphasis on claimants to engage the support of third parties, such as TSOs or informal support networks. Only 20 (16%) LAs offer some form of extra assistance to applicants. But notably, 48 (39%) LAs encourage the use of third-party assistance, explicitly naming friends and family, local charities, or support workers, even sometimes suggesting a social housing landlord or employer. This imposes a ‘duty to help yourself’ (Daguerre Citation2007) and emphasises the responsibility of the local community to support claimants. By making the application process more difficult and not providing support LAs decrease service availability to particular groups and reduce the number of applicants.

That is not to say that all LAs are unsupportive, there are some standout examples of best practice where LAs adjust processes to be more open and inclusive. Liverpool City Council (Labour),Footnote22 Halton Borough Council (Labour),Footnote23 and Middlesborough Borough CouncilFootnote24 (No Overall Control) offer a freephone number. Norfolk County Council (Conservative) begin the application form stating, ‘[t]his can take more than 30 minutes so give yourself enough time’,Footnote25 which gives people adequate information to prepare a suitable time to complete the form, or an indication for anyone supporting the claimant. Haringey Council (Labour), who reopened a scheme in 2022, have been actively contacting people to promote the scheme, stating: ‘We are writing to some residents we’ve identified as eligible for support with basic living needs this winter through HSF. If you haven’t received a letter, we encourage you to still apply. Apply online’.Footnote26 Sheffield City Council (No Overall Control) offers guidance and examples with the online form.Footnote27 Unusually, Barking and Dagenham Council (Labour) offered a face-to-face or home visit if the claimant was unwell or unable to leave the house.Footnote28 These, often small, adjustments to LA practices foster a more positive environment for users by rendering services more open, accessible, and welcoming.

Funding information

The level of funding available was not a topic typically discussed on LA webpages. The content analysis undertaken discovered that only three LAs provided a breakdown of the funds allocated to LWA schemes. In 2022/23 Birmingham City Council had an annual budget of £488,962.22Footnote29; Bristol City Council had a budget of £700,000, 50% of which was ringfenced for LA tenantsFootnote30; and Wokingham Borough Council (No overall control) had a smaller budget of £23,170.Footnote31

A further nine LAs stated on their webpage or policy document that once the budget had been exhausted for the year no further awards would be made but did not include details of what funds had been allocated. Birmingham City Council briefly noted: ‘The scheme is funded on an annual basis and once the fund has been exhausted for that financial year, there will be no further awards’.Footnote32 Only two LAs explicitly said that the budget had to be stretched to cover the whole duration of the year. Therefore, the type or level of support available is often dependent on the time during the year that the claimant makes an application and state of the funding at that time. Significantly, this not only creates a postcode lottery of the type detailed in existing research but also a seasonal lottery. This seasonal lottery causes insecurity for claimants because they cannot predict where or when funds might available. It also creates horizontal inequity because one early claimant might be awarded a much higher value award than a claimant who makes the same claim a month later.

This resulted in what an interviewee referred to as ‘famine and feast’, where the year starts with worries about being able to meet demand or support people in crisis and ends with suddenly having funds that are time limited and need to be spent quickly. For instance, after being asked about levels of funding Interviewee Five, a front-line LA officer, noted:

We did actually get a little extra pot last year, this was for … by time we got the money we had maybe four months to spend it. … so … let’s say we’ve got like certain limits for like what we’d give single people, like we don’t tend to give them a washing machine unless there’s like a real medical need for it … in those cases we were thinking people who would only get certain things we can kind of [award them] upgraded white goods and charge it to that other fund instead.

This problem was said to be particularly associated with the Household Support Fund because although interviewees welcomed the extra funding pots, they expressed discontent at the time it took to filter down to administrative levels and its ad hoc nature. This suggests that funding deficits are one fundamental reason that LAs are rationing resources, there is simply not enough to go around. This has the potential to create variation in support even for claimants within the same administrative boundary, which has knock on effects for the predictability and certainty of the schemes.

Referral agencies

Some LAs add an additional barrier to crisis support by requiring applications be made by a referral agency. Referral systems can come in different forms but essentially require the claimant to seek a third party to support an application or make an application on their behalf. It was found that 9% of LAs had implemented this requirement. These referral agencies included citizens advice, local charities, local churches, local schools, and social workers. This system was described in the following way by North Yorkshire County Council:

In order to ensure that those most in need get the maximum support when they need it, the North Yorkshire local assistance fund works with a number of key voluntary, community and statutory services as ‘authorised agents’. An authorised agent is an organisation that can make direct referrals to the local assistance fund on behalf of applicants. The fund’s authorised agents will be: in contact or working with the client, and have knowledge of their needs or circumstances; able to help identify those in most need who may be eligible for the fund; and able to provide confirmation verifying that they have had sight of the required forms of evidence of identification and of need.Footnote33

The referral agency is said to support LWA by engaging people who might not otherwise make a claim because these agencies have the expertise and understanding of the process to support a successful claim. For instance, one interviewee, a front-line LA officer, noted:

It’s because the people doing the referrals are probably going to be people in official organisations who already have a relationship with the applications themselves. Or it might be like, say, if the housing associations, you know, kind of doing a lot of stuff, they might have all the evidence already that we’re after, like bank statements and universal credit statements.

However, welfare systems that require citizens to be represented by a third party have been said to create ‘an institutional barrier to access rather than a form of empowerment’ (Dagdeviren et al. Citation2019, p. 155). By engaging third-sector organisations LAs create a buffer between themselves and the applicant. Delegating some responsibility for the claimant. The third-party acts as an initial judge of applications and in doing so, many of the applicants are likely to be siphoned off before an application is even taken to the LA, creating a gatekeeping mechanism. In these cases, referral agencies are operating outside of the authority of the LA and have a large degree of discretion on how they advise and support claimants. Which can enable referees who are keen to impose their own standards or moral distinctions between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ claimants (May et al. Citation2019). This can create variety in the quality of services that claimants receive, dependent on the third party that is supporting the application which may not be monitored or even accountable to the LA.

Contracting out

The most obvious example of delegating responsibility is the outsourcing or contracting out of local welfare to outside service providers. In total 22 (18%) open schemes, had entered partnerships or passed responsibility for the scheme onto another organisation. These include: two authorities who devolved responsibility to district councils; four authorities that had outsourced to Citizens Advice; six authorities contracted out to local charities, including Selnet Ltd, the CHS Group, First Point Dorset, Auriga Services Ltd, Disablement Association of Barking and Dagenham, and Urban Outreach; five LAs who had entered two partnership arrangements with other LAs, and two LAs who had other LAs operating the scheme on their behalf; and one LA which entered into partnership with a credit union.

This added layer in the public bureaucracy of welfare implementation is said to have wide ranging implications, reconstituting and redefining the organisations, services, and actors (Larner and Butler Citation2005). One concern, relevant to this article, is that outsourcing weakens administrative justice by reducing standardisation (Thomas Citation2021). The quality of policy, decision-making and internal redress mechanisms have been challenged on the ground that knowledge may differ, motivations may conflict, and accountability takes different forms – often based on the contract with the LA. In particular, interviewees raised concerns that partnership working or contracting out could result in precarious schemes. Interviewee Nine, a national advocate, stated:

You’re at greater risk of creating something ad hoc and postcode based if you’re kind of working with partners, unless you’re able to work with the partner that’s able to support you to offer something that’s more holistic across the locality.

Adding to this concern, Interviewee Eight, a national advocate, noted:

For a lot of them, it’s a struggle as well with the cost-of-living crisis and stuff. So, if they collapse or they can’t keep going, then there’s a big hole that’s left in in communities. … That’s the thing like with the voluntary community sector organisations, it’s great that it’s there. But it is also slightly precarious, because we never know when the next round of funding is coming.

On the flip side, there are those who find that outsourcing, especially to the third sector, enhances administrative justice (Morse Citation2018). Several interviewees emphasised the strength that partnering with other organisations, and in particular TSOs, induces. Interviewee Two, a LA officer, for instance, stated:

We’re lucky that we’ve got [TSO] who have developed it in such a great way and that we’ve got such a good relationship with them because it I think having a positive relationship with the provider just enables us to do what we need and get the best results.

The benefits of third-sector involvement were put down to in-depth local knowledge. experience of their local area, and the ability of third sector specialists to make clients feel more comfortable than the council could:

A lot of those organisations really know the people in their area who need support and I think people feel a lot more comfortable going to maybe a warm space for support rather than the Council with that kind of, the whole kind of idea of going to the Council seems quite formal and a little bit scary. Whereas going through community organisation, I think people enjoy, people feel comfortable there.

When asked about the role of the TSOs in LWA, interviewees depicted TSOs as placed between the parameters of the contract and the discretionary space for administering LWA, where they had to meet the demands of the LA but also had their own discretionary responsibility and power to create policy, albeit secondary to the LA. Interviewee Seven, a third sector member, stated:

[Our TSO] must deliver the scheme within the parameters of the contract. However, this is a discretionary scheme that is delivered from a fixed budget – we have the exceedingly difficult job to ensure the funding last throughout the year, or we would be in breach of contract. As long as we stay within the parameters of the contract regarding delivery and initial eligibility requirements, we have discretion over how the budget is spent – for example, we have freedom to set secondary eligibility criteria, such as household income thresholds and number of items allocated.

Here, it become clear that engagement with third-sector organisation brings an additional layer of bureaucracy.

During interviews it also became evident that TSOs were not only administering LWA but also supplementing the budget. Delegating responsibility therefore became a method used by the LA for raising funds for the LWA schemes. The third sector has to compete for the contract during the procurement process and to be deemed competitive has to minimise expenditure for the LA, but this has left TSOs with a reduced budget which is often inadequate to meet local need. Therefore, the third sector also becomes responsible for sourcing additional funding to ‘top-up’ LA budget: ‘So actually, we put in a small amount compared to the charities in terms of [funding]. A lot of these charities put in quite significant sums of money into this area themselves’. (Interviewee Two (LA Officer)). Here, third-sector organisations are supplementing the budget of what is supposed to be a publicly funded welfare scheme.

The third sector was also framed as a front-line actor, this extended to the organisations at the periphery of the contractual relationship, especially subcontracted organisations and authorised agents who act as a first line of defence and held gatekeeping responsibilities. This responsibility was defined in Cambridgeshire County Council minutes, as:

The agent is responsible for checking eligibility and stating the case for their client, giving details of the circumstances that have caused this need, how they have already attempted to resolve the situation and any other support in place.

The data illustrates that when LWA is outsourced to TSOs, they become front and centre in the administration of this public service. Edmiston et al. (Citation2022) argue that these TSOs take on an important role in ‘mediating the claims-making process’ between citizens and LAs (Edmiston et al. Citation2022, pp. 789–787). However, these workers carve out a space somewhere between the meso-level of LA governance and the micro-level of front-line work, which takes on a role beyond mediation (Meers et al. Citation2024). The outsourcing of welfare has contributed to hybridisation (Buckingham Citation2012, Kendall Citation2004, Evers Citation1995) of TSOs by encouraging and requiring TSOs to adopt multiple roles in the administration of LWA. On one end of the spectrum, TSOs are undertaking roles synonymous with higher tiers of local government, including policy creation and raising funds. On the other end of the spectrum, TSOs take up roles in direct contact with citizens, operating as proxies and front-line administrators. It is in this ‘in-between’ position that third sector actors fulfil a crucial but overlooked role in public administration, they co-determine the public policies, and are policymakers in their own right. In such situations, they become the meso-level of bureaucracy.

A resource-demand paradox

All interviewees commented on the pressures of making design decisions under conditions of ‘skyrocketing’ demand and limited resources. They underscored the constraining influence of demand on their ability to exercise discretion, which one interviewee estimated has risen by three times since 2019. This limitation was compounded by the withdrawal of ring-fenced funding and magnified by significant cuts which had created chronic resource inadequacy in LAs.

Interviewees discussed ‘multitudinous’ reasons for rising demand. In particular, discussing the fallout of inadequate levels of centralised welfare benefits and the consequences of punitive welfare reforms in combination with the effects of COVID-19 and the cost-of-living crisis. Interviewees also discussed new and different issues ‘popping up’ (Participant One). Among those were the restarting of debt repayment orders, online gambling debt, the £19 billion in unclaimed benefits, and zero-hour contracts – to name but a few. The combination of structural challenges to the central welfare state and the continual emergence of additional financial challenges meant that LAs were met with an ‘avalanche’ of demand with ‘pockets of need everywhere’.

In combination, it is this demand-supply dynamic which was said to cause exceptional problems for meso-level bureaucrats in the design of workable eligibility criteria. Although in practice LAs are free to decide in the absence of statutory requirements, in practice discretion is heavily qualified by restricted funding and rising demand. This is reminiscent of Lipsky (Citation1971, Citation1980, Citation2010) characterisation of micro-level public bureaucracy, where he flipped Dworkins doughnut inside out to illustrate that ‘street-level bureaucrats’ also make public policy yet reasserted the hierarchical nature of administration by highlighting the ability of the higher authority to bound decisions by conferring pre-determined resources. If not a belt of rules, then a belt of resources (Scourfield Citation2015). It is this belt of resources that appear to constrain meso-level actors.

All interviewees made it known that, in the face of untenable social and financial strains, they had to make difficult decisions and choices in the design of LWA often between claimants that were simply ‘more worse off’ than others. As Interviewee Seven, a third sector member, divulged:

Unfortunately, this service has a very limited budget to manage and demand far exceeds the help we can provide. It means we must make some exceedingly difficult choices and that some people who do need the assistance may not get the help that they need.

This perfectly encapsulates the situation that interviewees presented, where need and demand were ever-present, but the administrative capacity and funding was not in any way sufficient – which led to ‘difficult choices’ having to be made by meso-level actors.

The evidence of ‘difficult choices’ creates a paradox between the government’s statement that LAs are best placed to meet local need and the realities of fiscal deficit at local level, alongside the expectation that they meet the shortfall in the central welfare system. Far from feeling best placed to deliver crisis support, several interviewees made references to heading towards a point of no return, to a ‘cliff edge’, because of the combination of localised support and the ending of additional support funds. Interviewee Six, a national advocate, suggested that LWA had never recovered from the funding cuts made in its first years: ‘Because, I’m sure you know, I mean you’ve probably got all the stats around local welfare provision and how that’s just gone off a cliff since the government sort of went from centralised to localised welfare provision’. Here, they highlight that the shift from central to local welfare was not accompanied with a shift in resources. Interviewee One, a third sector member, observed that the temporary funds had been topping up the LWA but raised concerns around the uncertainty of future resources: ‘Up until now central government has been providing these Household Support Funds. But when that tap is closed, there’s going to be a cliff edge. And who’s going to pick that up?’ Here, the interviewee reveals the shaky ground upon which LWA has been built and the uncertainty about what the future will bring.

Conclusion

In answer to the questions posed at the beginning of this article, the data demonstrates that Dawn’s experience of local welfare, although startling, is reflective of the design decisions of LAs across England. Dawns case demonstrates an acute example of the limiting, rationing and delegating strategies used in the design of LWA. The offer of limited support, on LA terms, stripped to the barest minimum were all reflected in the design of eligibility criteria, types of support, funding information, referral practices, and outsourcing. That is if the LA offered a LWA scheme at all. The reasoning behind these decisions can be traced back to the supply-demand paradox. LWA schemes cannot be created according to the highest standards because meso-level bureaucrats’ decisions are constrained by exhaustive demand and ever reducing resources. Instead, meso-level actors manage the task of designing local welfare schemes within these constraints by developing these coping practices or strategies. If we think back to Dawn being offered vouchers to buy a tent through this supply-demand lens, the decision begins to make sense. As a result of these strategies in action, claimants are faced with inaccessible, unavailable, and discriminating local welfare schemes. Certainly, Dawns offer of a tent would fall into under this category.

By identifying the meso-level as a critical place of LWA decisions for welfare claimants, I have begun to examine the underexplored intersection between LAs, social security, and design. Engaging with the meso-level and design decisions can demonstrate the evolving role of LA actors in light of localisation. These finding are also significant because they suggest that design decisions are important in representing the influences on meso-level working conditions, and because they suggest implications for the operation of these schemes in practice by street-level bureaucrats and their impact upon claimants/recipients. The design decisions of meso-level bureaucrats, the strategies they employ, and design components they create are, therefore, an important site of analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/P000649/1]. It is based on a chapter of my MPhil thesis. Thanks are owed to interviewees who generously took the time to talk to me. I would also like to thank my reviewers and MPhil examiners for their helpful comments. Lastly, particular thanks to my supervisor, Linda Mulcahy, and to Jed Meers for all your support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Reference Number: R87223/RE001.

2. I made a judgement on the status of the schemes based on whether the information of the webpage(s) met the defining conditions for a scheme according to the criteria outlined by Central Government. This figure is higher than other reports because of my inclusion of district councils.

3. https://www.haringey.gov.uk/community/here-help-financial-support-residents/haringey-support-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

4. https://www.durham.gov.uk/welfareassistance. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

5. https://www.barnet.gov.uk/benefits-grants-and-financial-advice/grants-and-funding/barnet-local-welfare-assistance-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

6. https://www.medwayadvice.org.uk/local-welfare-provision-lwp. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

7. https://www.lancashire.gov.uk/health-and-social-care/benefits-and-financial-help/help-with-essential-household-items/?page=1. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

8. https://www.barnsley.gov.uk/services/advice-benefits-and-council-tax/benefits-help-and-support/local-welfare-assistance-scheme/. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

9. https://beta.southglos.gov.uk/welfare-grant-scheme. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

10. https://www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk/residents/children-and-families/parenting-and-family-support/cambridgeshire-local-assistance-scheme#eligibility-criteria-0–2. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

11. https://www.thurrock.gov.uk/essential-living-fund/about-essential-living-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

12. https://www.haringey.gov.uk/community/here-help-financial-support-residents/haringey-support-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

13. https://www.sandwell.gov.uk/info/200145/benefits_and_grants/2576/local_welfare_provision. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

14. https://www.redcar-cleveland.gov.uk/benefits-and-support/discretionary-social-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

15. https://www.redditchbc.gov.uk/money-education-and-skills/benefits-and-help/essential-living-fund.aspx. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

16. https://www.redcar-cleveland.gov.uk/benefits-and-support/discretionary-social-fund. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

17. https://www.worcester.gov.uk/housing/benefit-advice/discretionary-welfare-assistance-scheme#:~:text=The%20Worcester%20City%20Discretionary%20Welfare,of%20food%20or%20white%20goods. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

18. https://www.wigan.gov.uk/Resident/Benefit-Grants/Welfare-Reform/Local-welfare-support-professional-referral-form.aspx. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

19. https://www.sandwell.gov.uk/info/200145/benefits_and_grants/2576/local_welfare_provision. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

20. https://www.hounslow.gov.uk/info/20058/benefits/1493/discretionary_local_crisis_payments. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

21. https://www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housing/benefits-and-support/discretionary-support-grants/. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

22. https://liverpool.gov.uk/benefits/help-in-a-crisis/liverpool-citizens-support-scheme/. [Accessed 2 March 2023].

23. https://www3.halton.gov.uk/Pages/CouncilandBenefits/Discretionary-Support.aspx. [Accessed 15 March 2023].

24. https://www.middlesbrough.gov.uk/community-support-and-safety/community-support-scheme. [Accessed 5 March 2023].

25. https://www.norfolk.gov.uk/care-support-and-health/support-for-living-independently/money-and-benefits/norfolk-assistance-scheme. [Accessed 23 March 2023].

26. https://www.haringey.gov.uk/community/here-help-financial-support-residents/haringey-support-fund. [Accessed 24 May 2023].

27. https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/benefits/local-assistance-scheme. [Accessed 20 March 2023].

28. https://www.lbbd.gov.uk/benefits-and-support/discretionary-hardship-support/hardship-payment-schemes/individual-assistance. [Accessed 2 April 2023].

29. https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/lwp. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

30. https://www.bristol.gov.uk/residents/benefits-and-financial-help/local-crisis-prevention-fund-emergency-payments-and-household-goods. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

31. https://www.wokingham.gov.uk/benefits/local-welfare-provision/. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

32. https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/lwp. [Accessed 1 February 2024].

33. https://www.northyorks.gov.uk/local-assistance-fund [Accessed 1 February 2024].

References

- Aitchison, G., 2018. Compassion in Crisis: How Do People Stay Afloat in Times of Emergency? Salford. Church Action on Poverty. Available from: https://www.church-poverty.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Compassion-in-Crisis.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Atkins, G. and Hoddinott, S., 2023. Local Government Funding in England: How Local Government is Funded in England and How it Has Changed Since 2010. Institute for Government. Available from: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/local-government-funding-england. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Ball, D., 2014. Redesigning Sentencing. McGeorge Law Review, 46, 817–840.

- Batty, E., Beatty, C., and Casey, R., 2015. Homeless People’s Experiences of Welfare Conditionality and Benefit Sanctions. London: The Crisis. Available from: https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/20567/crisis_homeless_people_experience_of_welfare_conditionality_and_benefit_sanctions_dec2015.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Bond, D. and Donovan, C., 2022. Resetting Crisis Support: Local Welfare Assistance 2021/22 & Household Support Fund. End Furniture Poverty. Available from: https://endfurniturepoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/EFP-Resetting-Crisis-Support-Final.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Bondy, V. and Le Sueur, A. P., 2012. Designing Redress: A Study About Grievances Against Public Bodies. London: Public Law Project.

- Brenner, N., 2004. Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: OUP.

- Buckingham, H., 2012. Capturing Diversity: A Typology of Third Sector Organization’ Responses to Contracting Based on Empirical Evidence from Homeless Services. Journal of Social Policy, 41 (3), 569–589.

- Butler, P., 2013. Homeless? Here, Have a Tent. The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/patrick-butler-cuts-blog/2013/jun/03/homeless-pensioner-offered-tent-by-council. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Butler, P., 2015. Is U-Turn on Local Welfare Funds a Victory? The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/feb/24/u-turn-local-welfare-funds-victory. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Cambridgeshire County Council Adults Committee, 2016. Cambridgeshire Local Assistance Scheme (CLAS) for 2016/17. Cambridgeshire County Council. Available from: https://cambridgeshire.cmis.uk.com/CCC_live/Document.ashx?czJKcaeAi5tUFL1DTL2UE4zNRBcoShgo=lwGJ0U8GdjBcVpiU%2bDlEo44n2z4pUt7KaeBUSMNNTz4R62G5P7HEQA%3d%3d&rUzwRPf%2bZ3zd4E7Ikn8Lyw%3d%3d=pwRE6AGJFLDNlh225F5QMaQWCtPHwdhUfCZ%2fLUQzgA2uL5jNRG4jdQ%3d%3d&mCTIbCubSFfXsDGW9IXnlg%3d%3d=hFflUdN3100%3d&kCx1AnS9%2fpWZQ40DXFvdEw%3d%3d=hFflUdN3100%3d&uJovDxwdjMPoYv%2bAJvYtyA%3d%3d=ctNJFf55vVA%3d&FgPlIEJYlotS%2bYGoBi5olA%3d%3d=NHdURQburHA%3d&d9Qjj0ag1Pd993jsyOJqFvmyB7X0CSQK=ctNJFf55vVA%3d&WGewmoAfeNR9xqBux0r1Q8Za60lavYmz=ctNJFf55vVA%3d&WGewmoAfeNQ16B2MHuCpMRKZMwaG1PaO=ctNJFf55vVA%3d. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Charlesworth, Z., Clegg, A., and Everett, A., 2023. Evaluation of Local Welfare Assistance: Final Framework and Research Findings. Policy in Practice. Available from: https://policyinpractice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Evaluation-of-Local-Welfare-Assistance-Policy-in-Practice-January-2023-2.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Child Poverty Action Group, 2022. You Have to Take it Back to the bricks’ Reforming Emergency Support to Reduce Demand for Food Banks. Child Poverty Action Group. Available from: https://cpag.org.uk/news/you-have-take-it-back-bricks-reforming-emergency-support-reduce-demand-food-banks. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Clayton, J., Donovan, C., and Merchant, J., 2015. Emotions of Austerity: Care and Commitment in Public Service Delivery in the North East of England. Emotion, Space and Society, 14, 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2014.11.004.

- Costa-Font, J., and Greer, S.L., 2013. Territory and Health: Perspectives from Economics and Political Science. In: J. Costa-Font and S.L. Greer eds, Federalism and Decentralization in European Health and Social Care. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 13–34.

- Dagdeviren, H., Donoghue, M., and Wearmouth, A., 2019. When Rhetoric Does Not Translate to Reality: Hardship, Empowerment and the Third Sector in Austerity Localism. The Sociological Review, 67 (1), 143–160. doi:10.1177/0038026118807631.

- Daguerre, A., 2007. Welfare Reform in the United Kingdom: Helping or Forcing People Back into Work? In: A. Daguerre, editor Active Labour Market Policies and Welfare Reform: Europe and the US in Comparative Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 58–81.

- Daly, S., Chapman, R., and Pegan, A., 2023. Local Government Officers, Pragmatism and Creativity During Austerity–The Case of Urban Green Newcastle. Local Government Studies, 50 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/03003930.2023.2179995.

- Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011. A Plain English Guide to the Localism Act. Department for Communities and Local Government. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/5959/1896534.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Department for Work & Pensions, 2020. COVID Winter Grant Scheme Guidance for Local Councils: 1 December 2020 to 16 April 2021. Department for Work & Pensions. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-winter-grant-scheme. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Digby, J., et al. 2022. Understanding Digital Poverty and Inequality in the UK. The British Academy. Available from: https://apo.org.au/node/320897. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Donson, F. and O’Donovan, D., 2016. Designing Effective Parliamentary Inquiries: Lessons Learned from the Oireachtas Banking Inquiry. Dublin University Law Journal, 39 (2), 303. Available from: http://www.dulj.ie/Volume-39_2_2016.html. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Dworkin, R., 1977. Taking Rights Seriously. London: Duckworth.

- Dwyer, P., 2018. Punitive and Ineffective: Benefit Sanctions within Social Security. Journal of Social Security Law, 25 (3), 142–157.

- Eagle, R., Jones, A., and Greig, A., 2017. Localism and the Environment: A Critical Review of UK Government Localism Strategy 2010–2015. Local Economy, 32 (1), 55–72. doi:10.1177/0269094216687710.

- Edmiston, D., et al. 2022. Mediating the Claim? How ‘Local Ecosystems of support’ Shape the Operation and Experience of UK Social Security. Social Policy & Administration, 56 (5), 775–790. doi:10.1111/spol.12803.

- Evans, A., 2010. Professional Discretion in Welfare Services: Beyond Street-Level Bureaucracy. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Evans, A., 2011. Professionals, Managers and Discretion: Critiquing Street-Level Bureaucracy. British Journal of Social Work. [ Online]. 41 (2), 368–386. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq074.

- Evers, A., 1995. Part of the Welfare Mix: The Third Sector as an Intermediate Area. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 6, 159–182.

- Featherstone, D., et al. 2012. Progressive Localism and the Construction of Political Alternatives. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37 (2), 177–182. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41427938.

- Fitzpatrick, S., Pawson, H., and Watts, B., 2020. The Limits of Localism: A Decade of Disaster on Homelessness in England. Policy & Politics, 48 (4), 541–561. doi:10.1332/030557320X15857338944387.

- Gardiner, L., 2019. The Shifting Shape of Social Security. Resolution Foundation. Available from: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2019/11/The-shifting-shape-of-social-security.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Glennerster, H., 2020. The Post War Welfare State: Stages and Disputes. St Louis: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, 03. https://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/spdo/spdorn03.pdf.

- Grover, C., 2012. Localism and Poverty in the United Kingdom: The Case of Local Welfare Assistance. Policy Studies, 33 (4), 349–365. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.699799.

- Grover, C., 2014. From the Social Fund to Local Welfare Assistance: Central–Local Government Relations and ‘Special expenses’. Public Policy and Administration, 29 (4), 313–330. doi:10.1177/0952076714529140.

- Handscomb, K., 2022. Sticking Plasters: An Assessment of Discretionary Welfare Support. Resolution Foundation. Available from: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2022/10/Sticking-plasters.pdf. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Hetherington, P., 2010. Pickles’s Localism is Not What it Seems. The Guardian. Available from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/joepublic/2010/aug/04/eric-pickles-definition-of-localism. [Accessed 2 Feb 2024].

- Hick, R., 2022. Austerity, Localism, and the Possibility of Politics: Explaining Variation in Three Local Social Security Schemes Between Elected Councils in England. Sociological Research Online, 27 (2), 251–272. doi:10.1177/1360780421990668.

- Keep, E., 2011. The English Skills Policy Narrative. In: A. Hodgson, K. Spours, and M. Waring,editor Post-Compulsory Education and Lifelong Learning Across the UK: Policy, Organization and Governance. London: IOE Publications, 18–38.

- Kendall, J., 2004. The Voluntary Sector: Comparative Perspectives in the UK. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Kjellberg, F., 1995. The Changing Values of Local Government. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 540 (1), 40–50. doi:10.1177/0002716295540000004.

- Larner, W. and Butler, M., 2005. Gove Rnme Ntalities of Local Partnerships: The Rise of a “Partnering State” in New Zealand. Studies in Political Economy, 75 (1), 79–101. doi:10.1080/19187033.2005.11675130.

- Lipsky, M., 1971. Street-Level Bureaucracy and the Analysis of Urban Reform. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 6 (4), 392–409. doi:10.1177/107808747100600401.

- Lipsky, M., 1980. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lipsky, M., 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lowndes, V. and Pratchett, L., 2012. Local Governance Under the Coalition Government: Austerity, Localism and the ‘Big Society’. Local Government Studies, 38 (1), 21–40. doi:10.1080/03003930.2011.642949.

- Maclennan, D. and O’Sullivan, A., 2013. Localism, Devolution and Housing Policies. Housing Studies, 28 (4), 599–615. doi:10.1080/02673037.2013.760028.

- Mashaw, J.L., 1983. Bureaucratic Justice: Managing Social Security Disability Claims. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.