ABSTRACT

Photovoice is a child-friendly method used in Participatory Health Research (PHR) to put children in a subject position to drive the research and social change. Little is known about the actual experiences of doing photovoice related to health issues in a primary school context regulated by adults. The purpose of this article is to explore how children’s voices can be genuinely taken into account in research and social change, and what the potentials and tensions are when using photovoice in schools. We present a case example of a PHR with primary school children using photovoice, and will focus on the lessons learned. Participating children were eager to tell their photostories, proud of their achievements, and felt ‘seen’ by adults, expressed in the phrase ‘Are we famous or something?’ Playful activities and concrete instructions helped children to create their own narrative. For the development of the children’s critical consciousness reflexive participatory actions and photo-elicitation were crucial. Their visuals prompted discussion and led to actions and plans taking into account their perspectives. Tensions included the struggle to find a right balance between guidance and control, protection and respect for autonomy and preset system requirements. Reflexivity and creativity are required to handle such tensions.

Introduction

The interest for the participation of children and youth in research is growing. It has been argued that it is important to listen to their perspectives and to understand their lived experiences (Sinclair Citation2004; Green & Hogan, Citation2005; Clark Citation2007). The United Nations Convention of the Right of the Child (Lundy & McEvoy, Citation2012) has further stimulated the development of research strategies adjusted to the rights of children. Particular issues raised when doing research with children include their cognitive and reflexive capacities (Malone and Hartung Citation2010), their dependency (Dedding et al, Citation2015; Shier Citation2001) and communication difficulties, which may indeed as Alison Clark (Citation2010) suggests ‘rest with the researcher rather than the participants involved.’ (p. 116).

Participatory research is a way to actively engage children in the research process (Groundwater-Smith, Dockett & Bottrell, Citation2015; Gibbs et al. Citation2018). Such an approach goes further than asking children how research information can best be presented to peers or to respond to pre-given questionnaires developed by adults (Israel et al. Citation2005). Participatory approaches actively collaborate with children and use child-friendly methods (Kalnins et al. Citation2002; Davo-Blanes and La Parra Citation2012; Pike and Ioannou Citation2013). Photovoice is such method (Wang et al. Citation2004). In photovoice participants are encouraged and assisted to take photos illustrating key issues relevant to their lives. Photovoice appeals to our visual culture and is accessible for children. It is less verbally focused than most methods and appropriate for those who are not too good at putting their ideas into words. Moreover, it gives children literally control, because they handle the camera and take the pictures. Children become active agents in exploring their own experiences and perception of the world (Cook and Hess Citation2007).

In photovoice favorite photos are chosen and discussed in the participant group to raise their critical consciousness (Carlson, Engebretson, and Chamberlain Citation2006; Wang and Burris Citation1997). This assists participants to identify pressing issues that are relevant to their life and to discuss these issues with others (Warne, Snyder, and Gillander Gadin Citation2012). On the one hand, photovoice can help children to be more conscious of structural inequalities (Ingram Citation2013), to take collective action (Wilson et al. Citation2007) and to critically interrogate adult perspectives (Alexander, Frohlich, and Fusco Citation2014). On the other hand, photovoice can help adults in gaining insights into children’s perspectives and recognize the value of their input (Wang and Burris Citation1997; Wang et al. Citation1998). Hence, a dialogue between children and adults can be stimulated which is crucial to foster social change.

Voicing children’s perspectives through photovoice is the first step, but these need to be shared in dialogue with adults as a basis to drive further action and – eventually- social change that meets children’s needs (Wang et al. Citation2004). Photographs can be useful for this purpose, because they do not only present a picture, but also encourage us to think critically about what we see (Gergen and Gergen Citation2012; Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, Citation2017). Reading about poor child health and well-being is one thing, but seeing the reality of these children’s life can have a huge impact and motivate people to take action (Sarti et al, Citation2017). Yet, we should remain realistic; change is not linear and it may take longer before an agenda is realized (Hergenrather et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, collective actions by children and youth may not always ‘reach the anticipated depth in thinking and action’ (Wilson et al. Citation2007, 253). Chio and Fandt (Citation2007) point out that development of critical consciousness among youth required storytelling and reflexive capacities, and active stimulation by facilitators. Moreover, photovoice designs vary in the degree to which they promote participant voice. Evans-Agnew and Rosemberg (Citation2016) notice that what is seen by participants is not always exhibited and genuinely taken into account. Selective seeing and strategic listening may occur (Mitchell, De Lange, and Moletsane Citation2017). This is especially tricky in a school context, a setting typically regulated by adults. Finally, the quality of the facilitators and amount of actual time to develop actions are important success factors, and group dynamics and programmatic issues such as the planning for action require deliberate attention (Wilson et al. Citation2007).

So, while the literature indicates that photovoice can be a child-friendly method and set up a dialogue with adults, there are also questions concerning the ethics and politics of photovoice with children. In this article we further explore the promising findings of photovoice as well as the tensions that can arise when working with photovoice in a primary school context. The purpose of this article is to further explore the potential and tensions of using photovoice related to health issues in a school context by presenting an in-depth case example. It is part of a broader health promotion project in a disadvantaged neighborhood in Rotterdam, one of the four big cities in The Netherlands. In this four-year project children, parents, teachers and other community partners collaborated to jointly develop health-related actions. We report on the first stage of the project (7 months) in which partners jointly developed actions and plans tailored to the needs of children.

Methodology

The KLIK project: KLIK (an acronym of the Dutch phrase that may be translated Children Learn Inventive Strength) is a Participatory Health Research (PHR) project aiming to improve the health and well-being of children living in an underprivileged neighbourhood (Abma et al. Citation2019). It does not impose life-styles on children, but engages them in a process of inquiring their lives, what they think is healthy or not, and how their health and well-being can be improved from their perspective. We focus on food, exercise and well-being, because these are considered the main factors to influence children’s health (Braveman and Barclay Citation2009; Mendoza Citation2009). The study was financed by a Dutch charity fund (Fonds Nuts Ohra) stimulating the health promotion of disadvantaged families and children. KLIK was set up by us in the suburb where we both have been living for more than thirty years. We are both mothers with grown-up children. One of us, the first author, works at a university, and she and one of her junior researchers assisted the second author, a community partner and professional photographer, with her activities in the school. Photovoice and photography played an important role in KLIK, along with other arts-based and creative methods.

Setting: The project started just before summer July 2016 and ended February 2017. After approval from the charity organization the project continued for three more years (ending December 2020). The project was located in Oud-Charlois, a neighbourhood in the south of Rotterdam. It is an underprivileged part of the city with a relatively young population and a wide variety of residents with a migrant background (mainly Moroccan, Turkish, Surinamese, but lately also Polish and Bulgarian). At the same time, many artists and creative entrepreneurs are attracted to the area because of the low rentals. The educational level is lower than in Rotterdam and the Netherlands, and a higher proportion of the residents struggle to make ends meet (Christiaanse, Stam, and Schouten Citation2009). The health condition and subjective health is lower compared to the city and country. Important health risks include overweight and smoking.

Participants: From the start one of the primary schools joined the project. The second author knew the school, because her own children went there. It was therefore relatively easy to engage the interest of the school principal, teachers and many children knew and trusted her. The participating school is part of a group of schools working actively to combat childhood obesity under the motto ‘Lekker Fit’ (Nice & Fit). Art and culture are also important for the school. Children were recruited from the top three classes of this school: one group 6 (30 children), two groups 7 (21; and 22 children). So, in total 73 children participated in the reported phase of our project. From this group 12 children were recruited to join additional activities. Other community partners who committed themselves to KLIK represented a wide variety of expertise on nutrition, exercise, sport, art, culture, education and health and social well-being.

Design

We followed a PHR approach (Abma et al. Citation2019; Gibbs et al, Citation2018). Our main goal was to gather narratives of the children to inform the development of health promotion plans, and eventually promote social change. We used photovoice and other arts-based and creative methods (drawing, mapping, tours and games etc.) to engage children (Groundwater-Smith, Dockett & Bottrell, 2015). Other more traditional methods, including participant observation, semi-structured interviews and focus group conversations, were used to further enrich our understanding of the children’s lives. These additional methods also helped to answer our questions regarding the potential; value and tensions of the photovoice methodology to engage children, and set up a dialogue with adults for social change.

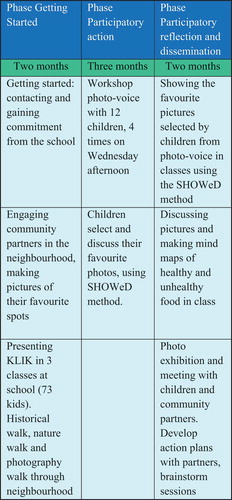

In retrospect three phases can be reconstructed (see Scheme for overview):

Phase 1 getting started: Understanding the context (qualitative interviews, document analysis of existing health surveys and data), and building up commitment with the school and partners. Plus, building up rapport and getting to know the children of the school and engaging them in actions, including three walking tours, a historical tour, a nature/wildpluk walk and photography tour (73 children).

Phase 2 participatory action: Photovoice with a selective group of children. Twelve children jointed the photovoice workshop that met four times for about 2,5 hours on Wednesdays immediately after school. The diverse group consisted of eight girls and four boys; two with a Dutch origin, three East-European, five Surinamese/Dutch Antilles and two children with a Turkish background. This included informal focus groups to stimulate storytelling and understand the children’s experiences of photovoice activities.

Phase 3 participatory reflection and dissemination: Children joining the photovoice reflected on their own work, and presented it to other classmates for further reflection as well as to parents, teachers and community partners to develop future action plans. For example games were played in the classes, and children were asked to make a mind-map or drawing of their ideas on the topics of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’.

Throughout all phases we met four times with community partners in the form of focus group meetings. In these meetings they shared their experiences concerning child health and obesity in the neighborhood, responded to the children’s work and brainstorming sessions were devoted to possible ways of improving the situation. Participant observations were completed throughout the whole project to understand the context.

Multiple methods

Multiple methods were used. These are discussed in detail below.

Participant observation

During various project activities, such as the city walks and photovoice, participant observations were conducted by the junior researcher and the final author; a period of about 20 hours was devoted to this activity. In addition, schoolchildren were observed at lunchtime and playtime, and during gymnastics lessons. Participant observation was used to collect information about social (inter)action, including group dynamics in the photovoice workshops, interactions between school children and teachers, and provided an opportunity for informal conversation. Field notes made at the time formed the basis for a subsequent observation report; a logbook was kept during the whole process including memos and reflections of the researchers. Observations were used as input for the interviews and focus groups to gain an understanding of the meaning of social (inter)actions and school context.

Semi-structured interviews

As part of getting started 17 community partners including school teachers, the school principal, dieticians, general practitioners, active citizens, artists and parents were interviewed using a semi-structured format. The topics covered were experiences of the neighborhood, the health of residents, in particular children, experience of health promotion schemes, ideas for health promotion, potential partnerships and possible obstacles to or opportunities for health promotion in the neighborhood. All interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and fed back for credibility (member check).

Focus groups

Six focus groups in total were organized in this project. The 12 children who had signed up for the photovoice workshop joined two informal focus group conversations to initiate a storytelling process on the pictures taken and share experiences of the photovoice activities. They played a game that facilitated discussion of the photographs they made about health-related issues, like food and exercise. Also, focus group sessions were held with adults (community partners) to respond to the work of the children (10–20 adults per session). All sessions were tape-recorded and transcribed.

Document analysis

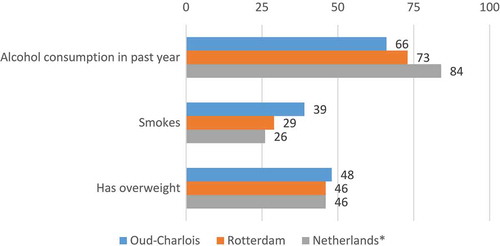

Existing descriptive quantitative data was gathered on overweight, smoking and alcohol use (Stuij Citation2015). Overweight appeared an important health risk in Oud-Charlois; 26% of the children aged 4–11 years were overweight, as compared with 20% in Rotterdam and 13% in the Netherlands. Among adults (19–65 years) 48% was overweight compared to 46% in Rotterdam and The Netherlands. Statistics showed that alcohol consumption was a bit less problematic compared to citizens in Rotterdam and The Netherlands (66% versus 73% and 84%). This was related to the relative high percentage of Muslims. However, 39% smoked compared to 29% and 26% in Rotterdam and The Netherlands (See ).

Analysis

The first aim of our analysis was to understand the factors that influenced the health and well-being of the children; the second aim was more methodologically oriented, namely to understand how photovoice could maximize the participation of children and be used for dialogue with adults, and what tensions might arise. The analysis was a cyclic and iterative process, because we had to repeat steps and discuss our findings several times before we were satisfied with answers to our questions concerning photovoice. The interviews with community partners were analyzed by us through thematic analysis and core themes were translated into a ‘problem tree’ to visualize the problems related to children’s health and well-being. The problem tree was discussed with community partners, and gave participants the opportunity to reflect on the various factors involved to children’s health and well-being (member check), and to contribute their personal thoughts on this subject with the aid of post-its. All other data (transcripts interviews, focus groups, field notes, logbooks and creative artifacts) were initially analyzed by the researchers using a hermeneutic approach (Lieshout and Cardiff Citation2011). This approach focuses on the meaning of experiences and social action. To enrich our sense making we discussed our initial findings with various partners, including the children and teachers in school.

Quality criteria

The qualitative data from the interviews, focus groups, meetings, and field notes were complemented by quantitative data on experienced health, overweight and obesity, smoking behavior, use of alcohol to permit triangulation. To provide a member check, a summary of the interviews was send back to the participants and they were asked if it provided a true picture of the conversation (Guba and Lincoln Citation1989).

Our project was approved by the institutional ethical board. Besides informed consent and confidentiality various additional ethical principles were taken into consideration during this project: working on mutual respect, participation, active learning, making a positive change, contributing to collective action and personal integrity (Banks and Manners Citation2012; Banks and Brydon-Miller Citation2019). In practice this meant involving people and key figures from the neighborhood from the start of the project and discussing with them how to work together and form appropriate partnerships. Approval was obtained for the publication of all photos used for publications.

Findings

Below we present the findings following the phases of the project.

Phase 1 – getting started

As part of getting started interviews and informal talks with various members of the community supporting primary school children in the neighborhood were used to ‘test the water’. All underscored the urgency of our initiative with the aid of examples:

“A lot of fast food, in large portions. Especially when the parents are a bit better off.” (retired General practitioner)

“I can see, they start isolating themselves and are less happy when they are overweight.” (Gymnastics teacher at school)

During the initial meeting of the community partners a dialogue led to the formulation of a set of underlying values and 12 core principles that partners felt should be taken into account when formulating health promotion plans:

Attune to the perceptions and values of children

Involve personalities with a vision

Envision concrete improvements

Make small steps at a time

Have fun

Walk the talk

Adjust to the context

Reward positive changes and behavior

Empower

Motivate

Encourage participation

Make room for creativity

During this phase we also wanted to build up rapport with the children in the three classes (N = 73). Based on the dialogue with community partners we decided to focus our attention on primary school children aged 8–11 years. We expected the children in this age group would be open and interested to work along with us to improve their health and well-being. To engage them in our project we started off with three walks through their own neighborhood; a historical, nature (wildpluk) and photography walk where children made photos.

The photography walk created a rich picture of the neighborhood from a child’s perspective, and included pictures of trees, trash, cars, dog poo, signs, art, animals, houses and people. The children were very handy with the camera and took pictures both showing the negative sides of the neighborhood (poverty, trash in the street, unhealthy food, broken-down cars etc.) as well as beauty around them (trees, flowers, animals, colorful food dishes). During the walks children were interested in small details (for example, kneeling on the ground to make a picture of a bird) and very active: they were running around, playing, climbing fences and so forth. They were very happy to be out of doors, curious and enthusiastic, to discover and learn new things, as reflected in the following quote:

“Now I know what a hazelnut-tree looks like!”

Phase 2 – participatory action

After the walks, the children were more familiar with us and we asked them if they wanted to take part in a photovoice workshop. Nineteen children signed up. We wanted to pay genuine attention to each individual child, and based on our observations in class we noticed a group of 19 was too big to be supported by two facilitators. So we decided to select a smaller group of children who needed this the most in terms of emotional deprivation and low self-esteem. This selection was made in consultation with their teachers. We also tried to balance the number of girls and boys, the variety of cultural backgrounds and aged groups. Eventually, twelve children were selected for the photovoice workshop. We sent their parents a letter informing them about the aims of the project and the workshop, which was designed to elicit the children’s opinions about their health and well-being.

At the beginning of each workshop we all had lunch together. During lunch we instigated talks, for example, about what sort of food everyone liked, and what they would normally eat at home. In the first workshop we showed the children how to take photographs and they practiced this in small groups. We taught the children visual thinking in a playful manner; the second author learned them for instance to see patterns, colors, black and white, and different perspectives via the use of mirrors. We wanted to prevent the reproduction of stereotypical images, and therefore stimulated the children to look carefully and try to see and literally reframe their world with the camera in our own hands. The photographs resulting from this were a means to ‘speak back’ and counter the traditional representations of themselves and their environment, and offered agency and authorship to the children.

After instruction in the workshop on how to reveal patterns and regularities with the aid of photographs, the children were encouraged to take pictures in their home environment and received a camera. This practice assignment further developed their visual sensitivity as well as their photographic skills. Then the children were challenged to make more complex pictures, like photographing a moving object. We sensed the children were very eager to learn this new way of approaching the world around them. One of the children said for example:

‘Miss! I suddenly see patterns everywhere!’

Each week the children were asked to put their experience into practice in different ways. One week they had to take photographs about what they ate at home, where they ate and with whom. See for example the photographs showing a wide variety of typical Dutch and multicultural dishes (See image 1).

Another assignment was related to exercise: what do you do in your spare time, where do you play, with what and with whom?

Each week the children could choose to print one of their pictures they particularly liked, and they would put this in their own personal diary.

Phase 3 – participatory reflection

In this phase we started the reflection on the pictures taken, first among the children in the photovoice workshop, then among a broader group of children and finally with adults.

Reflection among children doing photovoice

In one of the last meetings of the photovoice workshop, we gathered all the photos the children had taken, and a game using a dice was used to structure discussion of what they had photographed, why, who was around when the photo was taken, and whether other children saw the picture as representative of something in their own life. This investigation followed the lines of the SHOWeD approach (Wallerstein & Bernstein, Citation1988), which attempts to answer the questions: What do you See here? What is really Happening here? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this situation, concern or strength exist? What can we Do about it?

Many children chose and liked the pictures where they played outside. For example, two boys selected their favorite picture where they are jumping on a trampoline (See image 2). They motivated their choice in a narrative on how they liked to play outside, but that opportunities were scarce. In the garden of the former school where the photovoice workshop was held they felt inspired to play like they were knights, running up and down, using wooden sticks as knives, climbing into trees and jumping on a trampoline without a mother or father watching them. Other children responded that they also liked to play outside in the large playing field: they just loved this opportunity to run around in the open air. Others explained that they also particularly enjoyed the play time during the workshop because:

“We do not have such a big garden at home.”

“At home we do not go to play outside.”

This provided us with the opportunity to talk about inequality. That some children have more opportunities than others. This prompted another girl to choose a picture of herself swinging in the air (See Image 3). In her narrative she revealed she felt she was too fat. She went to see a dietitian to lose weight and dearly wanted to, but she ‘just loved candy’ even though she knew sugar was unhealthy and not good for her. Sitting on the swing set was terrifying at first, because she felt afraid the stool would break under her weight. Later on she developed confidence and loved to swing into the air, higher and higher. Her life was depressing; she had a chronic disease (arthritis), had to take medicine every week, was bullied at school for being too fat, her parents had been divorced and her dad ‘does not want to know her.’ She could not join sports in school, because of her rheumatic disease, and often felt alone. Playing outside was forbidden by her mother, because she felt playgrounds were unsafe. Swinging into the air gave her a feeling of freedom.

This story could be shared because the girl trusted the facilitator (JS). She and other children would for example spontaneously come up to the facilitator to share their experiences, and all stayed in the workshop for the whole period, even though it was their free afternoon.

Through these narratives we developed a sense of what was important for the children (playing freely outside, with friends, without adults watching them), and what factors prevented children to do so including not having access to a large garden, and playgrounds which were (perceived to be) unsafe or dirty. In order to further deepen this understanding we asked them what further prohibited them from playing outside. This triggered a conversation on poo. As there were many pictures of poo, and we gave them an assignment to think of titles for these pictures. For we did not want to reproduce a stereotypical image of the poor, dirty neighborhood. Post-its were developed by kids with funny titles like, ‘The poo walks away.’ (See Image 4) The post-its and pictures were later used in a self-made newspaper for children and community partners.

Participatory reflection in larger group of children in class

We revisited the three classes after the photovoice workshop and presented the photographs from the walks and the workshop to the children. We publicly complimented the children on the pictures they had taken, and stressed the visual quality of some of the pictures. This was well-received; all eyes were shining hearing this. One of the children even came up to one of us after the class was over and said how much she appreciated the compliment. It also struck us how interested the children were in the photographs their classmates had made. They were really looking at the photos, and eager to discuss what they saw (see image 5).

We also set the broader group of children a number of assignments. The first assignment was to make a display of unhealthy or healthy food that could be eaten at breakfast, lunch or dinner. Photographs were then taken of these displays to discuss whether the children thought the meals on the plates were healthy or not. We noticed that the children knew quite well what food was healthy and what was unhealthy, but they were less certain about the amount of food that could be considered healthy or unhealthy. In the second assignment we asked the children to make a mind map or drawing of their mental reaction to the words ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy.’ The unhealthy pictures and mind maps showed a lot of fries, hamburgers, chocolate, snacks, and sodas. The healthy pictures and mind maps showed a much greater variety, and included all kinds of vegetables, fruit, and water (See image 6).

During these assignments some children appeared critical of control by adults in general, and expressed their recalcitrance toward the assumption that they might not know what is healthy. Illustrative are some of the comments on their drawings, such as:

“Some parents or other people interfere with us too much.”

“I don’t like it when my parents tell me to eat healthy food when I’m already doing that.”

The third assignment was a game in which we called out a few statements describing possible after-school situations or activities, such as:

I watch TV after school

I play outside after school

My parents are at home after school

The children were asked to stand up if the statement usually applied to them, and to remain seated if it did not. This assignment showed that almost one-third of the children were alone after school, and that many of them watched TV and/or played computer games. Some said they played outside. In the fourth assignment the children were asked to think of possible ways of making children healthier. More specifically, they were asked to think of one or more of the following plans:

How to make children eat more fruit

How to make children eat more vegetables

How to teach children what is healthy and unhealthy

How to get children to play outside

How to encourage children to take part in sports activities

How to teach children that exercise is good for you.

Children liked the game, and possible plans that children came up with included creative solutions reflecting the unique worldview of children:

“Make them think that unhealthy food is poisoned”

“Turn eating vegetables into a game”

“Invent a spray to make vegetables taste good”

“Get them to exercise with their parents”

“Tell them the TV is broken and they have to play outside”

“Make better playgrounds”

In line with the suggestions to make better playgrounds in another meeting with the children (compare: Clark Citation2007) we led a conversation on one of the pictures selected by the children from the photovoice workshop. The ‘Jumping into the air’ photo was used to trigger such a conversation. We started to ask the children what happened on the picture, and then moved on to ask them what they thought would be a nice playground. To which they responded:

It should have: a slide, a soccer field, a swimming pool, a ballet field, a podium, a swing set, a climbing frame, a trampoline, a basketball field. A green jungle, a climbing wall, a treehouse or hut. Animals, horses. A resting place, a café to have a drink and a toilet (often mentioned). A place for skeelers and steps, a karting job, painting ball and laser game. Be friendly and festive. Without cars, motor cycles, or holes in the field. Friends to play with, no interfering adults.

Children also made drawings of the ideal playground, which looked like (See image 7):

What they particularly disliked: A grey, colourless area with only bricks and stones, no green, no toilet, no playground equipment, with a lot of litter like alcohol tins, drugs, poo. They insisted on the following:

“Children should have fun on a playground.”

“Playing with your friends, not being alone.”

“Not using the playground as a soccer field if there is a soccer field”

‘It is not okay if there are annoying children who say ‘Get out of the way’, or who say ’Get off the swing set.’

“It is annoying if there is nothing for the young children; ‘I want to play, but I have to take care of my little sister.’”

Dialogue with adults

Also, the parents of the participating children in the photovoice workshop were invited to view the pictures their children had taken, and were asked what they would like to do to improve child health and well-being. Six parents attended the meeting and showed an interest in the photographs and drawings the children had produced. During the ensuing conversation, the parents said that they would like to learn how to prepare a variety of new, healthy dishes. They liked the idea of a cooking workshop for parents, or for parents and children together.

The photovoice workshop and the class assignments led to a photo exhibition and meeting attended by all the children and participating community partners, who were asked to reflect on the photographs, pictures and other material produced by the children (See image 8).

The children were invited to attend this event together with the adults, and expressed pride that their opinions were being listened to and their work was seen. They were surprised with the attention given to them, and also felt they were ‘seen’ and acknowledged as human beings. It was clear that more explicit attention by adults was not common in their lives; not at home, nor at school. One of them put the rhetorical question:

“Why has everyone come to meet us here? Are we famous or something?

The community partners were very interested in the material the children had created, and the school principals present noted that the children seemed enthusiastic and involved. Responses from the adults included the following:

“I would love to set up a project like this for my children.” (Director of the second primary school)

“All the children yell when I write on the blackboard that we are going to have another KLIK day; they really look forward to them.” (Teacher)

All the material and input provided by the children formed the basis for a brainstorming session in which the community partners suggested possible health promotion plans. Some responses to the photos:

“I see a lot of multicultural dishes. That reflects our neighborhood.” (Mother)

“What about sport? Boys like to play soccer, what do we have for girls of that age? Dance perhaps?” (Director primary school)

Besides the continuation of activities focused on food, it was felt activities needed to be broadened to include free play, sport and active physical activities. We asked the children what they would tell other children about KLIK, and got positive responses on several activities like the smoothie-workshop and wildpluk tour. Details of the health promotion plans were elaborated in subsequent meetings with our adult partners to yield three sub-plans, which were based on the input of the children, and covered one action plan for each of the main domains of the children’s life: home, school, and the neighborhood/street. We wrote a proposal for these plans, in consultation with the community partners and added photos, drawings, mind maps and quotes of the children.

After these months the project was followed up by three years wherein the action plans were implemented with the kids in two primary schools, a group of mothers who joined a photovoice empowerment training, and youth leading playground activities (so-called ‘big brothers’).

Discussion

The purpose of this article is to explore how children’s voices can be genuinely taken into account in the research and social change, and what the potential and tensions are of using photovoice on health-related issues with children in a primary school context. In our project we worked responsively to maximize the children’s ability to participate in order to collect narratives to be addressed in dialogue with adults (parents, teachers and policy makers). From photovoice we took the political notion that voices can be articulated through images and shared to raise pressing issues and put them on the agenda of policymakers (Wang et al. Citation2004). From photo-elicitation we took the idea that the meaning of photos is not given, but needs to be articulated through storytelling and ‘retrospective engagement’ (Chio and Fandt Citation2007; Harper Citation2002). Gathering in a group helped to share stories and engage in critical dialogue to generate common issues. It was this participatory, polyvocal and multi-method arts-based approach that shaped our project and advanced the children’s voice and translated it into plans. We see similarities with the mosaic approach of Clark (Citation2007, Citation2010, Citation2011).

Our findings resonate with the literature on the powerfulness of photovoice as a participatory process of research and social change with children. The children effectively placed outdoor playing on the agenda, and thus focused on the environmental changes to promote health instead of focusing solely on individual life-style changes. Their perspective on outdoor play emphasized the need to be with friends and have an adventurous space, and thereby differed from an adult perspective on safety. Photovoice proved a nice combination of fun, creativity and collaboration in a way that encouraged the inclusion, active learning democratic participation and empowerment of children and adult partners (Blackman and Fairey Citation2007; Rappaport Citation1995; Schalkers, Bunders, and Dedding Citation2017). Once photographs had been taken they acted as a tangible representation of the children’s interests and in this way, they enabled to return to the issue later on for further discussion with the children as the photographs could be used as a reminder for the discussion. Think of the Jumping into air and Swinging into air photos. As Cook and Hess (Citation2007) pointed out, ‘Photographs provide an opportunity to have group discussions around a visual prompt which makes it easier than trying to talk about something in the abstract’ and ‘Given that a child will have taken the photograph, the stimulus for discussion starts from their interest.’ (p. 4) We also found that the photographs heightened the sense of urgency among adult participants to act on the needs and issues expressed by the children (Gergen and Gergen Citation2012). The photo exhibition motivated community partners to make plans in line with children’s perspectives (Mitchell, De Lange, and Moletsane Citation2017).

Photographs and other visuals made by children required interpretation to understand the issues raised by the children. The SHOWeD method provided a structure to reflect on the pictures, yet we experienced it also limited free conversation space. We felt that creating room for personal storytelling and inviting the children to tell the story behind a picture was most helpful to generate meaningful titles that reflected their inner feelings and values. We experienced that guidance sometimes turned into control and dominance of adult perspectives for example if the children complained about ‘lack of ideas.’ Difficulties relating to generating titles and critical thinking were also noted Wilson et al (Citation2007). Too much guidance may lead to ‘adulteration.’ We recognize what Shier (Citation2017) underscored in his work on research with children, namely that children learn through playing, and that playing is an essential element of research with children. Our lesson is that an active role of the facilitator is indeed needed to guide the children (Wang and Redwood-Jones Citation2001) and for ‘retrospective engagement’ (Chio and Fandt Citation2007), but in a way that is open enough to let the stories of the children breath, for example by asking questions.

We encountered several ethical dilemmas concerning the pictures presenting negative and stereotypical images of the neighbourhood (Byrne, Elloit, and Williams Citation2015). Our neighbourhood had often been in the national news, and media always focused on problems (unemployment, poverty, violence etc.). To prevent the reproduction of these images in some cases we intervened by not releasing such pictures. This is in line with the advice given on photovoice ethics: ‘even if they had signed the (informed consent) form project staff would not have used these pictures publicly because they were ‘incriminating.’ (Wang and Redwood-Jones Citation2001, 566). In other instances we found ways to show negative images with some irony and with a twist. Children were very good at this, as we have shown, coming up with funny titles like ‘Does this poo has legs?’ alongside the pictures of poo and dirty spaces. This was a way not to silence problems or children’s voices, but to show the children’s resilience, and their creativity to see things in a new light, and prevent unwanted stigmatization. These children wanted to be proud of their neighbourhood. In photovoice ethics this issue of balanced representation is addressed. Wang and Redwood-Jones (Citation2001) recommend to inform participants to make picture that are not only ‘accurate’ but also ‘representative to mobilize resources.’ (p. 568).

Another issue related to system requirements, like in our case preordained outcomes (reduction overweight eg.) set by the charity fund. This has received little attention in the literature. We had to work around these requirements to create space for the children to set their own agenda and choose their own issue, outdoor play. System requirements also related to the discipline in the primary school context. A school is a context which is typically regulated by adult rules limiting the freedom and creativity of the children. Again we had to work around these rules to create a space for the children to express themselves. Legal requirements regarding informed consent of parents sometimes led to tensions because the forms were too abstract, and children and parents sometimes had conflicting wishes. Given these ethical challenges Wang and Redwood-Jones (Citation2001) therefore recommend to start photovoice with a discussion on power, ethics and responsibilities. We experienced this to be helpful, but also felt that not all ethical issues can be regulated through rules and thus settled. In our work unexpected issues kept coming up and we needed to reflect on many ‘everyday’ ethical dilemmas during the process. Knowledge of visual and photovoice ethics (Wang and Redwood-Jones Citation2001) and ethics in PHR (Banks and Manners Citation2012; Banks and Brydon-Miller Citation2019) was helpful to anticipate these issues, but space needs to be created during the research to discuss such tensions.

Conclusion

Engaging children throughout the research process ideally begins with an issue they identify as important to them, and requires a ‘playful’ mindset and methods fitting children’s needs. In our project with primary school children in a neighbourhood known for its deprivation photovoice was a good way of hearing children’s voices and enabling them to represent their thoughts, understandings and constructs in ways that were not only accessible for them but also for adults. Once photographs had been taken pictures chosen by the kids acted as a tangible representation of their interests. Playful activities, training of their visual sensitivity and concrete instructions for taking photos helped the children to express their views. For the development of the children’s critical consciousness reflexive participatory actions and elicitation were crucial; such as storytelling and making drawings, playing games and mind mapping. Photo exhibitions displaying their photos triggered conversations with adults and led to shared plans of action. This was a joyful, creative and collaborative way of engaging children, parents, and community partners. Our study also shows how genuine involvement can be limited by preset system requirements and adult rules. Other tensions included the struggle to balance guidance and control, and protection and respect for autonomy. Reflexivity and creativity throughout the process was needed to handle these tensions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the joy and motivation of the children, and commitment of the partners who worked with us. This work was supported by FNO. Grant number: 101.578.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abma, T.A., S. Banks, T. Cook, S. Dias, W. Madson, J. Springett, and M. Wright. 2019. Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Alexander, S.A., K.L. Frohlich, and C. Fusco. 2014. “Problematizing “Play-For-Health” Discourses through Children’s Photo-Elicited Narratives.” Qualitative Health Research 24 (10): 1329–1341. doi:10.1177/1049732314546753.

- Banks, S., and M. Brydon-Miller, Eds. 2019. Ethics in Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being, Cases and Commentaries. New York: Routledge.

- Banks, S., and P. Manners. 2012. Community-Based Participatory Research. A Guide to Ethical Principles and Practice. Durham: Durham University.

- Blackman, A., and T. Fairey. 2007. The Photovoice Manual. A Guide to Designing and Running Participatory Photography Projects. London: Photovoice.

- Braveman, P., and C. Barclay. 2009. “Health Disparities Beginning in Childhood: A Life-Course Perspective.” Pediatrics 124 (3): 163–175. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1100D.

- Byrne, E., E. Elloit, and G. Williams. 2015. “Poor Places, Powerful People? Co-Producing Reproducing Cultural Counter-Representations of Place.” Visual Methodologies 3 (2): 77–85.

- Carlson, E.D., J. Engebretson, and R.M. Chamberlain. 2006. “Photovoice as a Social Process of Critical Consciousness.” Qualitative Health Research 16: 836–853. doi:10.1177/1049732306287525.

- Chio, V.C.M., and P.M. Fandt. 2007. “Photovoice in the Diversity Classroom: Engagement, Voice, and the “Eye/I” of the Camera.” Journal of Management Education 31 (4): 484. doi:10.1177/1052562906288124.

- Christiaanse, B., B. Stam, and G. Schouten (2009) “Gezondheidsenquête 2008. De Gezondheid Van Volwassenen in Deelgemeente Charlois Wijkrapportage (CBS Buurt).” Augustus 2009. GGD Rotterdam Rijnmond.

- Clark, A. 2007. “Views from inside the Shed: Young Children’s Perspectives of the Outdoor Environment.” Education 3-13 35 (4): 349. doi:10.1080/03004270701602483.

- Clark, A. 2010. “Young Children as Protagonists and the Role of Participatory, Visual Methods in Engaging Multiple Perspectives.” American Journal of Community Psychology 46 (1): 115–123. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9332-y.

- Clark, A. 2011. “Breaking Methodological Boundaries? Exploring Visual, Participatory Methods with Adults and Young Children.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 19 (3): 321–330. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2011.597964.

- Cook, T., and E. Hess. 2007. “What the Camera Sees and from Whose Perspective? Fun Methodologies for Engaging Children in Enlightening Adults.” Childhood 14 (1): 29–46. doi:10.1177/0907568207068562.

- Davo-Blanes, M.C., and D. La Parra. 2012. “Children as Agents of Their Own Health: Exploratory Analysis of Child Discourse in Spain.” Health Promotion International 28 (3): 367–377. doi:10.1093/heapro/das019.

- Dedding, C., R. Reis, B. Wolf, and A. Hardon. 2015. “Children’s Agency in the Clinical Encounter.” Health Expectations. doi:10.1111/hex.12180.

- Evans-Agnew, R.A., and A.-M.S. Rosemberg. 2016. “Questioning Photovoice Research, Whose Voice?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (8): 1019–1030. doi:10.1177/1049732315624223.

- Gergen, M.M., and K.J. Gergen. 2012. Playing with Purpose. Adventures in Performative Social Science. Walnut creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Gibbs, L., Marinkovic, K., Black, A. L., Gladstone, B. M., Dedding, C., et al. 2018. “Kids in Action - Participatory Health Research with Children.” In Participatory Health Research. Voices from around the World, edited by M. Wright and K. Kongats, 93–116. New York: Springer Nature, Switserland.

- Greene,, and Hogan. 2005. Researching Children’s Experience. Los Angelos: Sage.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., and S. Dockett & D.Bottrell. 2015. Participatory research with children and young people. Los Angelos: Sage.

- Guba, E.G., and Y.S. Lincoln. 1989. Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Harper, D. 2002. “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Hergenrather, K.C., S.D. Rhodes, C.A. Cowan, G. Bardhoshi, and S. Pula. 2009. “Photovoice as Community-Based Participatory Research: A Qualitative Review.” American Journal of Health Behavior 33 (6): 686–698.

- Ingram, L.-A. 2013. “Re-Imagining Roles: Using Collaborative and Creative Research Methodologies to Explore Girls’ Perspectives on Gender, Citizenship and Schooling.” Educational Action Research 306–324. doi:10.1080/09650792.2013.872574.

- Israel, B.A., E.A. Parker, Z. Rowe, A. Salvatore, M. Minkler, J. López, and P.A. Potito. 2005. “Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons Learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research.” In Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(10): 1463–1471.

- Kalnins, I., C. Hart, P. Ballantine, G. Quartaro, R. Love, G. Sturis, P. Pollack, et al. 2002. “Children’s Perceptions of Strategies for Resolving Community Health Problems.” Health Promotion International 17 (3): 223–233. DOI:10.1093/heapro/17.3.223.

- Labonte, R., and J. Feather. 1996. “Handbook in Using Story Dialogue in Health Promotion Practice.” www.icphr.org

- Lieshout, F., and S. Cardiff. 2011. “Dancing outside the Ballroom: Innovative Ways of Analyzing Data with Practitioners as Co-Researchers.” In Creative Spaces for Qualitative Researching: Living Research, edited by J. Higgs, A. Titchen, D. Horsfall, and D. Bridges, 223–234. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Lundy, L., and L. McEvoy. 2012a. “Childhood, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and Research: What Constitutes a ‘Rights-Based’ Approach?” In Law and Childhood Studies, edited by M. Freeman, 75–91. Vol. 14. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Malone, K., and C. Hartung. 2010. “Challenges of Participatory Practice with Children.” In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation: Perspectives from Theory and Practice, edited by B. Percy-Smith and N. Thomas, 24–38. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mendoza, F. 2009. “Health Disparities and Children in Immigrant Families: A Research Agenda.” Pediatrics 124 (3): 187–195. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1100F.

- Mitchell, C., N. De Lange, and R. Moletsane. 2017. Participatory Visual Methodologies. Los Angelos: Sage.

- Pike, J., and S. Ioannou. 2013. “Evaluating School Community Health.” Health Promotion International 1–10. doi:10.1093/heapro/dat044.

- Rappaport, J. 1995. “Empowerment Meets Narrative: Listening to Stories and Creating Settings.” American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 795–807.

- Schalkers, S.I., F.J.G. Bunders, and C. Dedding. 2017. “Around the Table with Policymakers: Giving Voice to Children in Contexts of Poverty and Deprivation.” Action Research. Apr. doi:10.1177/1476750317695412.

- Shier, H. 2001. “Pathways to Participation: Openings, Opportunities and Obligations.” Children and Society 15 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1002/chi.617.

- Shier, H. 2017. “Why the Playworker’s Mind-Set Is Ideal for Research with Children. Child Researchers Investigate Education Rights in Nicaragua.” In Researching Play from a Playwork Perspective, edited by P. King and S. Newstead. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sinclair, R. 2004. “Participation in Practice: Making It Meaningful, Effective and Sustainable.” Children and Society 18: 106–118. doi:10.1002/chi.817.

- Stuij, M. 2015. KLIK Cijfers En Achtergronden Oud-Charlois. Utrecht: Mulier instituut.

- Wallerstein, N., and E. Bernstein. 1988. “Empowerment Education: Freire's Ideas Adapted to Health Education.” Health Education And Behavior 15: 379–394.

- Wang, C., and M.A. Burris. 1997. “Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment.” Health Education & Behaviour 24 (3): 369–387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309.

- Wang, C.C., S. Morrel-Samuels, P.M. Hutchison, L. Bell, and R.M. Pestronk. 2004. “Flint Photovoice: Community Building among Youths, Adults, and Policymakers.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (6): 911–913. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.6.911.

- Wang, C.C., and Y.A. Redwood-Jones. 2001. “Photovoice Ethics: Perspectives from Flint Photovoice.” Health Education & Behavior 28 (5): 560–572. doi:10.1177/109019810102800504.

- Wang, C.W., Y.Z. Kun, K. Wen Tao, and Carovano. 1998. “Photovoice as a Participatory Health Promotion Strategy.” Health Promotion International 13 (1): 75–86. 1 Jan. doi:10.1093/heapro/13.1.75.

- Warne, M., K. Snyder, and K. Gillander Gadin. 2012. “Photo-Voice: An Opportunity and Challenge for Students’ Genuine Participation.” Health Promotion International 28 (3): 299–310. doi:10.1093/heapro/das011.

- Wilson, N., S. Dasho, A.C. Martin, N. Wallerstein, C.C. Wang, and M. Minkler. 2007. “Engaging Young Adolescents in Social Action through Photovoice: The Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) Project.” Journal of Early Adolescence 27 (2): 241–261. doi:10.1177/0272431606294834.