ABSTRACT

Multi-institutional and multi-professional research projects are valued for the impact and learning they generate, but their successful completion is crucially dependent on the various actors recognising their differences and working through/with them as a team. This paper is a critical reflection on one such participatory action research project, which involved new migrants and asylum seekers, an NGO, university researchers, and independent trainers in offering intercultural sexual health and gender relations workshops. It charts the course of this project by introducing the key players and focusing on significant differences and opportunities, and the critical learnings that this generated. The paper uses the concept of the ‘paradox lens’ as a way of understanding emerging dilemmas and tensions, and the subsequent compromises, co-operations and collaborations that ensued. In closing, it offers a set of principles generated from reflections on learning that occurred during the project, and which may be amended and adapted for other contexts and action research encounters that hope to engender collaborative learning.

Introduction

Partnership between organisations has been increasingly encouraged by funding agencies and research councils as a way of ensuring more responsive, sustainable and multi-perspective research outcomes and impacts (see for instance Fransman et al. Citation2021; Newman, Bharadwaj, and Fransman Citation2019). Whether between universities, policy organisations and/or practitioners, such collaboration is often seen to be a matter of identifying complementary skills and networks and establishing common goals. But the challenges and potential of negotiating shared objectives across boundaries, whether disciplinary or organisational, are not always straightforward, and are thus themselves the object of study (Trussell et al. Citation2017; Bjelland and Vestby Citation2017). This paper is a reflection on the processes involved in one such collaborative research project.

As Ashkenas (Citation2015, paragraph 1) notes in relation to interdepartmental collaboration, ‘it takes more than people being willing to get together, share information and cooperate. It more importantly involves making tough decisions and trade-offs across areas with different priorities and bosses.’ In response, Vangen (Citation2017) proposes adopting a ‘paradox lens’ on collaboration as a way of addressing areas of tension within management, governance and leadership in multi-organisational collaboration. Suggesting that ‘collaborations that have the potential to achieve collaborative advantage are inherently paradoxical in nature’, he argues that this is because ‘gaining advantage requires the simultaneous protection and integration of partners’ uniquely different resources, experiences, and expertise in complex, dynamic organizing contexts’ (Vangen Citation2017, 262). He emphasises the importance of using the paradox construct to enhance reflection in practice. As educational action researchers, we are interested in the analytical value of reflecting on the learning processes and paradoxes that we experienced as we went through the conceptualisation, planning and implementation of a collaborative research project.

The literature on multi-organisational collaboration has focused on how to navigate tensions (van Hille et al. Citation2019), empower communities or build capacity (Rasool Citation2017). Though these perspectives offer opportunities for reflection and learning, their analysis tends to remain implicit in such accounts. By contrast, our starting point is to investigate – through micro-level analysis of specific events and practices – how and what kind of learning takes place through the ‘paradoxes’ of collaboration. This paper sets out to answer the question: how can we engender collaborative learning in contexts characterised by multiple actors and agendas? To do this, it draws on the experiences and reflections from a participatory action research project that aimed to enhance intercultural learning on sexual health and gender relations among migrant communities.

The project drew together a diverse set of actors, organisations and professionals with different kinds of expertise, expectations and intercultural experiences. Working together for over a year and reflecting on the different kinds of learning we were engaged in raised critical questions about the processes and paradoxes of collaboration. The contribution of this paper lies in its analysis of the learning encounters and interactions between actors/institutions rather than just within them. Such a shift emphasises a more complex set of relationships and identities. The paper therefore is not concerned with the immediate intended ‘action’ of this participatory action research project (and its contribution to intercultural learning on sexual health.) Instead, it looks at a set of critical events and the unexpected insights into collaborative learning that they generated. These have been further developed into a set of principles that engender collaborative learning in contexts characterised by difference and diversity. We hope these could be amended and adapted for other contexts and collaborative projects.

Background to the project

The university researchers had a long-standing relationship with a non-governmental organisation (NGO) set up to support and empower asylum seekers and refugees in the local area. The NGO involved university students as volunteer mentors, NGO staff ran workshops for volunteers at the university on refugee rights and awareness, and MA course cohorts regularly visited the English language classes at the NGO centre. The NGO coordinator also sat on a committee associated with the University, as part of a more formal institutional relationship, and often liaised with the University admissions department on behalf of refugees who wanted to apply for university scholarships. The research project was set up to enhance intercultural understanding around sexual behaviour and gender relations among migrant, refugee, and asylum-seeking populations. A few years ago, the NGO noted that asylum seekers wanted to learn about cultural assumptions and legal frameworks around sexual abuse and gender relations in the UK. Since then, the NGO has been offering workshops in conjunction with a sexual health charity to address these issues. Later, they approached the university to help strengthen intercultural learning between participants, researchers, NGO staff, and workshop facilitators. They were aware that the sexual health charity had built their training approaches and workshops to respond to the values and practices of ‘settled’ UK communities and suggested that this was the time to reflect more critically on the appropriateness of this model for refugee and asylum seeker communities from diverse cultures. Having acted as resource persons on a participatory research training day at the university, the NGO staff proposed the idea of initiating a collaborative project with the university using this methodology. The university researchers, for their part, had experience of developing workshops in the Global South using participatory approaches, which could be adapted for participants who had arrived recently in the UK from countries in South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. This project was funded by the university through a scheme designed to accelerate the impact of research, through engaging with local partners.

Project design and research cycle

In terms of the project coming together, the NGO and university were the early initiators and ‘official’ partners in the project. Thereafter, two members of staff from the sexual health charity and a trainer from the local council with expertise on domestic violence were invited into the project by the NGO as facilitators of the workshops. Though these facilitators preferred to formally position themselves as working with the NGO’s training project, rather than a formal partnership with the university, they played a central role in shaping the research and were active and full participants in all research meetings and activities.

During the project, participants’ and facilitators’ knowledge, views, and experiences of sexual health workshops were explored through a participatory framework, to identify the tools and approaches that would support the particular needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Participatory Action Research (PAR), with its emphasis on reflection and learning for and through action (Whyte, Greenwood, and Lazes Citation1991), was central to the project design and ethos. PAR, by definition, is collaborative and change-oriented (Manzo and Brightbill Citation2007) and, at its simplest, involves researchers and participants working together to explore a particular situation or action to change it for the better (Kindon, Pain, and Kesby Citation2007, 1). The intention of implementing PAR was to eschew a researcher-driven approach more akin to Lewin’s early vision of action research (DePalma and Teague Citation2008), and, instead, require active participation, negotiation and collaboration among practitioners and university researchers in all stages of the research cycle. Taking a PAR approach to the complex and culturally-grounded field of sexual health education offered a means to disrupt more formalised and hierarchical relationships, bringing together facilitators and participants to develop workshop content, for example, and for team members to ‘work across axes of difference’ (Kesby and Gwanzura-Ottemoller Citation2007, 71). Such an approach also had the potential to address assumptions based on European constructs of sexuality and sexual health concerns, by sharing knowledge whilst navigating differences in cultural norms.

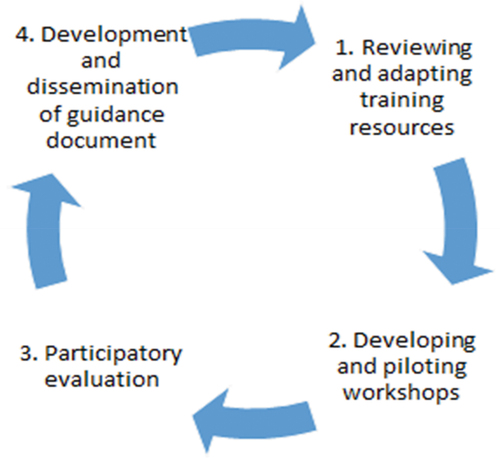

A first step in the project was for the project team to identify and share existing training resources, and to consider how these might be adapted to suit the needs of workshop participants and facilitators (). Then, NGO staff provided training for sexual health charity staff and the domestic violence trainer to inform their approach to working with refugees and asylum seekers. Following this preparation, pre-workshop exploratory sessions were held with participants, designed to elicit their direct input into needs assessment, curriculum and workshop development.

From July 2018 separate workshops for men and women were held at the NGO centre, facilitated by the external trainers and NGO staff. The workshops followed a similar structure to previous years, but with a curriculum and approach informed by the pre-workshop sessions and ongoing evaluation and learning events. An aim of this participatory evaluation process was to develop a critical lens on these workshops, based on insights from participant observation conducted by two university researchers. These researchers also facilitated focus group discussions and interviews with the workshop participants, facilitators and NGO staff, using participatory and visual methods to facilitate evaluation. Reflections on workshop content, facilitation and participant engagement did not come at the end of the action cycle, but were part of an iterative process, with learning emerging from earlier workshops informing later ones, and further informed by discussion during regular team meetings held at the university or in the city. Using participant observation as a tool within a wider PAR approach, we acknowledge that the meaning of ‘participation’ differs and blurs, with participant observation generally intended to observe change and participatory research to create change (Wright and Nelson, Citation1995).

An important dimension of the project was to bring research and training approaches developed in the Global South as a resource for organisations working with refugees and asylum seekers in the UK and other countries in the Global North. These approaches were used to facilitate several research activities. The research offered insights into cultural similarities as well as differences, ways of mediating language and meaning, and facilitation as an intercultural encounter. Reflection on these findings led the team to address issues around facilitators’ roles and relationships with participants, structure of the workshop sessions, language resources and additional support needs. After implementation and reflection on the workshops, a ‘Workshop Guidance’ pack was developed and launched at a national conference organised by the project in July 2019. Following this first cycle of action research, which was bounded by the project lifespan, NGO staff continued to adapt the workshops – responding to participants’ views and lessons learnt from the research findings. They maintained an interest in extending the cycle and producing further formal evaluation.

The challenge of hidden diversity

In this section of the paper, we wish to draw attention to the diversity amongst actors within this project, and the implications of this. At the start of the project, we were rightly focused on the diversity of participants in the workshops, i.e. the newly arrived members of the community. There were male and female nationals, ranging in age from late teens to the 60s, both single or married, from countries such as Iran, Pakistan, Syria, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Kurdistan and Sri Lanka. Talking about sexual relations, behaviour and health with a group characterised by such diverse demographics demanded careful planning and thought. The workshops needed to focus on diversity of opinion and practice across cultures, but equally on their differences with UK law and culture, which served as a common reference point. It is perhaps not surprising then, that we were drawn immediately to pay attention to the obvious differences of culture and nationality. But as Ahmed (Citation2000) has noted, we live in times where ‘the stranger’ remains highly visible – either celebrated as the origin of difference or feared as the origin of danger. Both orientations involve ‘stranger fetishism’, that is an assumption that strangeness resides in others; that the stranger is a taken-for-granted given, rather than as a concept that is constructed and performed. It was when we were able to confront strangeness/difference as an integral element to the whole team, as something beyond the usual boundaries of nationality and culture, that the various actions of cooperating, collaborating and compromising came to make a useful impact on the team’s functioning.

As the project progressed, we were confronted with the extent of diversity amongst ourselves as project partners. This diversity encompassed different professional and organisational orientations – we were a group of social science researchers from the university, non-governmental charity workers, national and local service providers. Each of these organisations and professions came with a particular orientation, agenda and purpose. And even within each of our institutions, we drew on diverse skills, expertise and disciplinary bases. For instance, the university team of 5 were drawn from multiple national contexts (English-Nepali, Scottish-Malawian, Indian-British, Turkish and Filipino), with experience of working in different countries, age groups and rooted in multiple disciplines (education, development, gender). The facilitators for the workshops had differing skills and experience of working in sexual health education, and women’s health and domestic abuse: most of this expertise was gained through working with local British populations rather than migrant groups. Staff from the NGO were most knowledgeable about the needs and strengths of newly arrived asylum seekers and refugee communities. This depth and breadth of diversity between us meant we simply were not (and could not) be fully cognisant of each other’s unique orientations and strengths from the start. As the project unfolded, we began to notice this diversity amongst the team and made adjustments to how we perceived each other and what this meant for the project as a whole. The next section of the paper focuses on specific learning encounters or moments – vignettes – that made us conscious of the differences between us, and how we needed to cooperate, collaborate or compromise to complete the project successfully.

Vignettes

Bridging the gap: negotiating differing expectations

From the outset, it was evident that the partner organisations each had different expectations from the project, particularly regarding the purpose of the research activities and the final dissemination conference. But all partners had a strong commitment to the support and empowerment of the refugee communities, and this was the thread that bound us as a team. This was set out in the research proposal: ‘the direct beneficiaries are the refugee and asylum seekers who will participate in the workshops. They will gain understanding and engage in cross-cultural dialogue about sexual behaviour and gender violence to enable them to better adapt to life in the UK’. We had also discussed and proposed in our funding application, that the partner organisations could benefit in terms of ‘developing a training package appropriate for these groups of people, which broadens perspectives on gender and relationships’. The dissemination strategy – particularly holding a national conference – was intended to ensure a wider group of beneficiaries across the UK (including refugee and health education organisations).

However, within this broad agenda, we each had different ideas about what the project could deliver, shaped by our varying expectations of ‘research’ and institutional priorities. The NGO staff saw the research element as akin to an evaluation, which could also provide evidence of good practice. They were keen to collect data before and after the workshops to evaluate how the participants’ understanding of sexual health and gender violence had changed through the intervention. This organisation, like others in the voluntary sector, were constantly seeking funds to keep themselves and their services viable. They saw the research as a useful resource for funding bids that would ensure their continuation. In contrast, we as university researchers set out with an agenda of facilitating reflection and change with all partners, as integral to a PAR approach. We consciously positioned ourselves as ‘critical friends’, to provide an outsider perspective on the workshops as a basis for reflection on what might be done differently. The researchers who were conducting participant observation in the workshops, found they needed to be explicit about their role, to dispel the notion that they were evaluators. By emphasising for instance, that the data would be analysed by the whole team, not just the university staff, as a way of seeking future improvements, the collaborative and action research aspects of the project were constantly foregrounded.

As university researchers, we also had instrumental and pragmatic reasons for involvement in the project, such as the need to demonstrate the ‘impact’ of our research, the basis on which the university had awarded the project grant. In the wider context of the UK higher education sector, the practice of regular assessment of research impact on organisations and communities outside academia to provide ‘accountability for public investment’ (through the Research Excellence Framework, REF Citation2021) shaped the university researchers’ orientation. The project took shape within such institutional agendas by offering the possibility of being an ‘Impact Case Study’.

Our different sectoral-institutional perspectives on, and expectations for, the research project emerged particularly when we were discussing the planned outputs of the project. Our proposal had included both academic and practice-orientated activities and outputs. Planned academic outputs included a co-authored research article written by the wider team to disseminate findings and a paper presented at an international education conference, ‘to deepen the impact … within the UK and internationally’ (from the proposal). This very paper itself is something that has greater value to the university researchers than the wider team, being framed by academic discourses (such as the ‘paradox lens’). This language is different from the ways in which we talked informally about emerging tensions or different expectations. Although we all critically reflected on our experiences of collaboration in our team meetings, writing about these issues afterwards, for an academic journal, was simply not a priority for the NGO colleagues, despite the authors’ original invitation to other members to collaborate in such efforts. They preferred to devote their limited time and resources – particularly stretched during the Covid-19 pandemic – on practical ways of following up on the project outcomes. On the practice side, NGO colleagues actively contributed to writing, feedback and adaptations for the Workshop Guidance pack, including providing insights into principles of engagement - co-created ‘recommendations’ developed for practitioners. These were all project outputs to be shared with other NGOs for informal feedback and presentation at the national conference. The NGO partners planned to use the action research findings to revise the workshop guidance for future sessions.

As the two university researchers conducted participant observation during the workshops, informal discussions with the facilitators were combined with more formalised presentations of the findings framed around ‘critical questions’. They discussed how the workshops might be adapted and how to revise the training package. In our team meetings at the university, the focus was more on the formal proposed output and NGO staff were keen to produce a training manual, which could be launched at the national conference. As university researchers we were cautious about preparing a ‘manual’ in case the workshop activities would be simply replicated or transferred to other contexts. Alternative terminology such as a ‘draft manual’ that participants at the national conference could contribute to and adapt, were also discussed. Finally, we decided to develop and publish a ‘Workshop Guidance’ in time for the conference. This was a compromise: a finished product that could be launched, but could also be framed as ‘guidance’ with suggestions for other organisations to adapt. It included exemplars in the form of ‘activity banks’ rather than a formal ‘how-to’ curriculum and included blank pages at the back for adding further activities and ideas. Producing such workshop guidance involved much learning on the part of the university team: in terms of writing in a more accessible and less academic style, whilst also including the critical questions and issues that had been the source of the whole team’s learning during the project implementation. It was a challenge to combine these two perspectives (critical research reflections and practical ‘how to’ advice), a potential source of tension when we came to prepare the national conference programme.

After the conference, the university researchers began to prioritise the proposed academic outputs. A team consisting of two university researchers and an NGO facilitator presented a paper at an international conference that reflected on the process of collaborating across institutions. The wider project team also presented findings at a university seminar and at a workshop at the County Council. The university researchers wrote a final report on these outcomes to the funding body and considered the project to be at an end, having produced the promised outputs. However, for the NGO, the work was not bounded by the deadlines and resources of the initial grant. They were keen for us to continue the research collaboration and pointed out that the new approach to the workshops had only just been implemented. The university researchers were invited to come and observe the process again and collect more feedback from the facilitators and participants. However, there were real time and resource constraints on such involvement once the university funding was over. In the end, two volunteer researchers were found (one was a university researcher who agreed to continue on a voluntary basis) to support this last phase, which has been more in line with the NGO’s objective of an evaluation study. As a university team, we continued to be involved with the NGO’s work informally.

Attempting compromise – participant-led content versus expert-led knowledge

Early tensions around different actors’ understanding and uptake of the participatory nature of the research emerged during activities to support the development of a curriculum for the women’s sexual health workshops. During a pre-workshop session, university researchers planned to employ creative, participatory methods to provide an opportunity for the women themselves to identify their needs, and shape future workshop content. This reflected the understanding underpinning the project – that participants’ needs and preferences would be placed first when establishing workshop goals and objectives. Researchers drew up a protocol that included a focus group discussion with women from the NGO’s English classes, who had been invited to join the workshops. The purpose of the focus group was to elicit the women’s perspectives on their lives in the UK, relationships and sexual health challenges and access to services, and to learn what additional information needs they had. This group discussion was to be followed by a participatory pair-wise ranking exercise (Narayanasamy Citation2009), which involved participants sorting and ranking these identified needs into their relative importance, using hand-written cards or symbols. The exercise was to act as a prompt to discuss the reasons behind participant’s choices regarding the various needs’ importance. Adaptions of this visual ‘draw-and-write’ activity had been used previously by one of the researchers in curriculum development activities for non-formal education programmes in Malawi, including sexual health and HIV education, and had worked well with diverse groups with differing levels of literacy. The facilitators were more familiar with another activity, ‘Diamond Nine’, a card-sorting activity used in UK education settings (cf. Clark Citation2012). Diamond 9 differs from pair-wise ranking in that the cards used are already populated with pre-selected topics. So, although the Diamond 9 exercise allows participants to consider the relative importance of topics, the use of pre-written cards restricts their ability to choose their own topics. A suggestion that some blank cards be included, to allow women to write (or draw) their own choice of topics, was not taken up.

On the day of the women’s workshop, both activities took place, although this ‘spirit of compromise’ risked a longer, and potentially tiring, session for the participants. The pair-wise ranking activity took place last (facilitated by the university researcher), following an introduction by NGO staff that included reference to a range of sexual health topics, and the Diamond 9 activity. This initial introduction to specific topics may well have pre-empted women’s perspectives and influenced their choices. Not surprisingly, many of these topics were later suggested by the women in the pair-wise ranking activity. While both activities ranked topics on where to find help/services as most important, the Diamond 9 activity saw issues of sexual rights, legal issues and consent rank highest, whilst during the pair-wise ranking activity, women also ranked emotional issues and relationships highly, perhaps reflecting their own concerns more closely. Using the pair-wise ranking activities proved additionally helpful as drawing was an effective way to overcome language barriers, whereas the words used on the cards for Diamond 9 needed to be explained in advance.

When introducing the list of possible workshop topics at the start of the session, it quickly became clear that much of the terminology relating to sexual health and relationships was unfamiliar to the participants. This initial constraint was mitigated somewhat when one participant became a de-facto translator for others. Other terms remained unfamiliar, overly formal and outside the ‘day-to-day’ of women’s knowledge. This requirement of women to decode and adopt the terminology of the sexual health experts illustrates the limits of a top-down approach to needs identification. Reflecting on this, the researcher observing the session suggested that facilitators consider including an introductory activity to unpack these terms and provide a visual ‘wall’ of definitions within the workshop space. This suggestion was indeed adopted during later workshops, and it proved popular with participants. Several additional topics were suggested by the women at the end of the activities, during a less structured, final ‘wrap-up’ session. Through this we learnt that such informal spaces for discussion were important in supporting knowledge sharing and allowing women’s voices to be heard, and we were challenged to consider whether such less structured activities were actually just as effective a way of finding out their needs. Whatever the means, opportunities to express their views were valued by participants. One woman stated,

When you told us that we are deciding the topics, I felt happy someone is hearing and caring for us.

This vignette, from early in the process, illustrates a paradox: how university researchers’ desired use of participatory research techniques to drive a bottom-up approach to needs identification was at odds with facilitators’ planned use of previously crafted sessions designed to ensure that key aspects of sexual health education were not missed out. By bringing in the women as active participants in the process of workshop planning, the facilitators gained insight into the relative importance of various topics in the context of the women’s lives. By combining these with more non-negotiable content (for instance, in sharing specific UK laws and regulations on consent, rape, domestic and gender violence), the workshops ultimately bridged the gaps between intentions for the workshops as understood by different team members.

Spaces for collaboration in workshop facilitation

During the workshop sessions, the facilitators were confronted with the differences between their approaches and the complexity of delivering sessions for a highly diverse and multicultural group. The women’s workshops were run by two facilitators (from the sexual health charity and the local council), who were both attending and supporting each other’s workshops. In the men’s group, the lead facilitator was a trainer from the sexual health charity who had years of experience conducting sexual health workshops with British youth. The co-facilitator was a member of the NGO staff who had been working with the men’s group participants in other capacities (advising on asylum applications, organising football games) for about four years. Between them, there were noticeable differences in terms of facilitation style, knowledge of the topic and relationships with the participants, which they were able to bring together in a complementary way. The lead facilitator focused on delivering from a pre-set curriculum drawing on his expertise on UK laws on consent and sexual offense, and the science of sexually transmitted disease spread. Participants often considered the lead facilitator as an ‘expert’ who could accurately answer queries. The co-facilitator drew on his strong relationships with the men’s group participants developed over the years as their mentor and confidante. For instance, he knew which participants were comfortable sitting beside each other. He could skilfully capture and re-phrase some participants’ speech when they attempted to speak in English; they shared in-jokes and a similar sense of humour.

The various strategies for the workshops were born out of the partnership between the two facilitators. As a duo, they had developed a certain dynamic, and created a friendly, open environment where honest and difficult conversations around sex, consent and gender relations occurred. However, they also expressed, in subsequent interviews, that the workshops would feel different every single time, particularly because the format, participants and topics would change every year. This fluidity of the sessions seemed to have given them an opportunity to learn from each other. During workshop breaks, they would speak to each other and informally evaluate the sessions that came before. Moving away from the tradition of seeing university researchers as evaluators, these two facilitators would sometimes ask the opinion of the researcher whose task was to observe and document the session. In these fleeting moments of collaborative dialogue, they were quickly appraising, redesigning and (re)strategizing workshop content and approaches in real time.

Another important aspect of such collaborative and informal learning was their ability to change the workshop format and activities in response to participants’ needs and interests. These attempts went beyond the project duration. For instance, one of the issues that emerged from the project was the limited interaction between male and female participants when there were sexual health concerns that were relevant to both. A year after the project, the facilitators (for the men and women’s groups) collectively decided to schedule the workshops on the same day – the males in the morning and the females in the afternoon so the two groups could interact over some shared lunch. The two groups did not interact as envisaged, and the facilitators accepted the practices and desires of the community members not to engage in conversations around sexual health in a mixed setting. In a way, the collaborative and developmental ethos of the project may have reframed these workshop days less as structured and formal, and more as fluid and responsive to the needs of the group members.

The NGO co-facilitator in the men’s group expressed how planning for and implementing the workshops over the years had also contributed significantly to his growth:

… in the first year I did give a lot of my own opinion … . we did not really discuss fully how I should go about facilitating it … I probably shouldn’t have done that as a facilitator. It’s a kind of natural thing when you’re having a discussion. But really the workshop is designed to make them think for themselves, develop their own opinions.

This excerpt illustrates how, over the duration of the project, the co-facilitator articulated a different understanding of his role and an explicit recognition of the importance of collaborative dialogue in designing effective workshops. The lead facilitator described these workshops as ‘nothing like I have done in the past’. He had been compelled to adjust and relearn his facilitation process (built by working with British youth) for a multicultural group drawn from countries and cultures that he had not encountered before. In one session, on the topic of marriage, one participant began sharing information about the dowry system in their country. The lead facilitator was visibly surprised and taken aback by the information. He later shared that it was in moments like these that he continued to learn from the participants.

These observations demonstrate how, in the span of the action research cycle, the workshops became much less facilitator-determined. While there were parts that were more akin to a lecture (when introducing UK laws), much of the workshop worked as a targeted conversation about particular topics reflecting participants expressed needs. This also led to participants sharing different aspects of their culture. Such exchanges generated new insights and expanded previously held ones on how sexual health is practiced and talked about in various contexts. These examples also show that the project – through its emphasis on collaborative learning – not only raised awareness but also facilitated intercultural learning that led to concrete changes.

Co-operation and collaboration on the national symposium

The power of the collaborative relationships between the project partners became more apparent when each of the actors were able to contribute in a way that allowed their strengths to be exploited. The myriad decisions and actions that needed to be taken towards organising the symposium offers us one such significant moment. The symposium as a whole was meant to increase the impact of the project and its contribution to a wider population. It stayed loyal to the participatory nature of the project, including workshop participants amongst the delegates and planning a range of interactive sessions.

After much debate and attempts to secure a venue away from our home turf, the NGO was able to secure the ideal venue for the day. Not only were the costs relatively inexpensive (for central London), the location with its main hall, break out rooms, and garden was ideal for delegates travelling from afar and for the activities planned for the day. Secondly, delegates and organisers were able to enjoy delicious and nutritious food supplied by a catering collective of migrant women, which tied in with the whole ethos of the project. Thirdly, being able to call on an appropriate, high-profile key-note speaker who was supportive of the symposium, and able to attract practitioners from relevant organisations working with migrants/refugees and asylum seekers allowed for better dissemination. Each of these elements was made possible through the NGO staff and their knowledge and networks in the wider community connected to supporting newcomers to the UK.

The university researchers, for their part, were able to draw on previous experience of running symposia designed to encourage participant interaction. The day was thus divided into several sessions that allowed participants to exchange knowledge and mingle with other participants. These sessions included the use of breakout group workshops with project team members sharing a particular activity from the activity bank of the Workshop Guidance. Each breakout group also included some of the participants from the original workshops. The focus of these group sessions were to (i) share the experience of the project team, (ii) draw on the expertise of the delegates and their experiences while discussing and reflecting on the activity and (iii) look for improvements or amendments to the activities. In doing so, the project team hoped to demonstrate that these activities were not a template to be followed, but a guidance to be adapted to different contexts and populations. The format of a World Café, where participating delegates were given 5 minutes each to present a slice of their organisations’ work to the conference followed by a brief question and answer session meant that the project team did not have to play the role of ‘experts’ delivering training to delegates. By bringing together our different strengths and expertise, the symposium allowed us moments of genuine collaboration and co-operation.

Discussion

The vignettes offer insights into the continuous processes of collaboration, cooperation and compromise in this PAR project. We originally anticipated challenges around ‘being participatory’ in relation to the micro level of the workshop planning and content, and for this reason had introduced participatory tools such as pair-wise ranking to make a space for participants to have a voice. However, as the project developed, we became increasingly aware that the question of ‘whose participation counts’ was equally relevant to us all as project team members. We increasingly discovered and negotiated different goals, identities, and organisation cultural values within our small team. Whilst such diversity can be seen as a resource – and indeed, recognition of our complementary skills had drawn us together as a partnership between university and NGO initially – it could also become a source of tension. As academic researchers, we are conscious of how PAR extends the ethical principle of respect, with all participants obliged to recognise that their peers and co-researchers have a right to a voice and a valuable contribution to make (Manzo and Brightbill Citation2007). In line with the theoretical underpinning of this paper, this also presented a paradox: whilst keen to bring the voices of other team members to the fore, including in the crafting this paper, we learnt to accept that this was not always what they wanted, or needed.

Turning to our opening discussion in this paper, Vangen’s ‘paradox lens’ emphasises the importance of working with, rather than downplaying, paradox and acknowledging contradictions or tensions: ‘there is a need to embrace the existence of paradox while simultaneously accepting that in practice, some kind of resolution is required insofar as enabling agency is concerned’ (Vangen, Citation2017, 266). Taking Schad et al.’s (Citation2016, 6) definition of paradox as ‘persistent contradiction between interdependent elements’, Vangen argues that it is not only the similarities between member organisations’ goals that influence the success of a collaboration, but also the differences: ‘differences in goals also facilitate collaboration as this implies greater synergies from diversity of resources’ (ibid, 265). Reflecting on, for instance, our project symposium in London vignette d, this event made particularly visible the different strengths that each partner brought to the collaboration. However, in the planning process, we had also become aware of our different objectives and ideas about what the symposium should set out to achieve – the NGO seeing it as a ‘training day’ and the university researchers believing it to be the main research ‘dissemination’ activity of the project. Whilst the two objectives were not necessarily in opposition, they influenced who we invited and the format of the programme. Our discussions about the organisation of this symposium could be seen in terms of recognising and balancing any possibly conflicting agendas. Reflexivity was central to this process, and, as Vangen suggests, rather than negating paradoxical tensions, it is about ‘asking questions (being reflexive) with respect to how tensions are managed’ (Vangen Citation2017, 267).

Reflexivity could be seen as a certain kind of informal learning facilitated through participatory action research projects such as ours. When we look back at the process of implementing this project, we are struck by the different kinds of learning that we engaged in. Through working with the NGO, the university researchers learned above all about the fragility of the voluntary sector in terms of insecure and short-term funding. A continuing desire to frame the action research as ‘evaluation’, rather than as professional development or even community empowerment, was linked to NGO staff’s experience of using an evaluation study to secure future grants. Their jobs and the support provided to refugee communities was dependent on such income, and our project was taking place in that context. By contrast, the university researchers implemented the research project as just one part of their job and took for granted the time-bound nature of the funding (only for one year) and the necessity of producing academic outputs. Coming together for the project meant that we began to understand how we differed as a team of non-governmental, council and university employees, particularly how our objectives and practices were being shaped by our institutional agendas. For others, the collaborative nature of the project and its emphasis on partnerships changed the way they view academic-NGO relationships in general. For instance, during our conference presentation, the NGO facilitator shared that he once worried about being part of this project because, in his experience, research tended to be extractive – getting data from NGOs, but not collaborating with them to develop potential solutions. Through this PAR project, he had appreciated that we were all learning together and attempting to improve practice, even in a limited timescale.

The overall experience of the project pointed to the importance of learning and accepting differences in perspectives and agendas, and also of building on each organisation and individual’s prior experience and skills. As Kesby and Gwanzura-Ottemoller (Citation2007, 78) observe, ‘Engaging with resistance productively, rather than being frustrated by it, will ultimately help strengthen PAR projects’. Our common commitment to the communities with whom the NGO worked was also a key factor in deciding when compromises needed to be made. In this respect, both the university researchers and NGO staff shared a recognition of the limitations of a project like this, especially in terms of how far it could address the deeply embedded structural inequalities that affect migrant women and men. As Vangen suggests, such understanding is integral to the process of collaboration: ‘the acceptance of the paradoxical nature of collaboration, with its intrinsic tensions, can ultimately lead to consideration of realistic rather than idealistic expectations of what can be achieved’ (Citation2017, 271).

Reflections and implications for practice

To conclude the paper, we set out reflections on the collaborative learning that underpinned the action research process. Some of these ideas emerged from principles that were part of our thinking from the start of the project. Others emerged during the course of the project, and yet others remain aspirational. We share these here, not as specific recommendations, but as principles for multi organisational groups and collaborators working across the academic-practitioner divide to consider, amend, change and develop further, within the contexts of collaborative learning, diversity and practice.

From the outset, we committed, as a team, to recognising and sharing different kinds of knowledge and experience, without ranking their importance or status, and giving equal value to all. Researchers, practitioners and participants each brought different expertise into the project. Through the project we gained important insights into each other’s skills and learnt how many can be harnessed in complementary and innovative ways.

Though coming from very different starting points, participants’ learning needs were central to our conversations and critical questions when establishing and reflecting on workshop objectives. The use of participatory means to garner workshop participants’ perspectives and preferences deepened understanding of these needs and provided bespoke and adaptable learning moments for both facilitators and participants.

We learnt that acknowledging and working through tensions requires commitment to making space to listen and to hear diverse views and positions without judging them. Team meetings, whether at the university or, less formally, in cafés in the city centre were valuable opportunities to learn about each other’s expectations and perspectives on the progress of the project. Integrating frequent spaces for reflection and learning into the action research cycle enhanced moments of understanding and genuine collaboration.

We recognised that our interactions and learning encounters needed to be situated and understood within a more complex set of relationships and identities, reflecting different institutional cultures, concerns and values. As the project evolved, we saw a number of different roles emerge – as presenters, translators, participants, contributors, facilitators, researchers, organisers, learners. These were not all necessarily decided upon from the start, and we learnt that they are open to different members of the group at different times. A participant may be a translator, a contributor or learner, for example, while researchers may ‘step-in’ to facilitate and NGO staff take up knowledge sharing and research dissemination activities. Understanding and celebrating the diversity in roles added to the richness of the research process and outcomes.

Learning occurred when these different roles and expertise, individuals and institutions, came together, albeit temporarily. We acknowledge that all of us experienced learning and, to various degrees, expanded our understanding and knowledge. Identifying the ways in which that learning and co-evolving occurred was an ongoing process. Whilst as researchers, we saw this as framed by the project cycle, we learnt that, for practitioners, learning was not bounded in this way, but rather continued to evolve and inform their work beyond the life of the project.

We realised that learning events can be uncomfortable, conflicting or even de-stabilising. They may fall short in their aim to empower participants or bring surprising expectations and unintended outcomes. We recognise that these disruptive moments are part of learning.

In our discussions, as a team, we were also aware that our small-scale project cannot change embedded structural inequalities and we needed to acknowledge our limitations within wider policy and social environments.

The learning from the project was opened for sharing across communities and organisations and genuine collaboration required opportunities to engage with all participating in the project.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues from New Routes Integration and their partner agencies for the many stimulating ideas, conversations (and fun!), which led to the writing of this paper: Dee Robinson, Amelie Sells, Roshan Dykes, Chris Simmons, Suki Dell, and Christen Williams.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ashkenas, Ron. 2015. “There’s a Difference between Co-operation and Collaboration.” Harvard Business Review 20. Accessed April 7, 2020. https://lp.google-mkto.com/rs/248-TPC-286/images/Google_6.23_HBR_article_Ashkenas.pdf

- Bjelland, Heidi Fischer, and Annette Vestby. 2017. “‘It’s about Using the Full Sanction Catalogue’: On Boundary Negotiations in a Multi-Agency Organised Crime Investigation.” Policing and Society 27 (6): 655–670. doi:10.1080/10439463.2017.1341510.

- Clark, Jill. 2012. “Using Diamond Ranking as Visual Cues to Engage Young People in the Research Process.” Qualitative Research Journal 12 (2): 222–237. doi:10.1108/14439881211248365.

- DePalma, Renee, and Laura Teague. 2008. “A Democratic Community of Practice: Unpicking All Those Words.” Educational Action Research 16 (4): 441–456. doi:10.1080/09650790802445619.

- Fransman, Jude, Budd Hall, Rachel Hayman, Pradeep Narayanan, Kate Newman, and Rajesh Tandon. 2021. “Beyond Partnerships: Embracing Complexity to Understand and Improve Research Collaboration for Global Development.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études Du Dévelopement 42 (3): 1–21.

- Kesby, Mike, and Fungisai Gwanzura-Ottemoller. 2007. “Researching Sexual Health: Two Participatory Action Research Projects in Zimbabwe.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place, edited by Sarah Kindon, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby, 71–79. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kindon, Sara, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby. 2007. “Introduction: Connecting People, Participation and Place.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place, edited by Sarah Kindon, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby, 1–5. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Manzo, Lynne C., and Nathan Brightbill. 2007. “Toward a Participatory Ethics.” In Participatory Action Research Approaches and Methods: Connecting People, Participation and Place, edited by Sarah Kindon, Rachel Pain, and Mike Kesby, 33–40. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Narayanasamy, Nammmalvar. 2009. Participatory Rural Appraisal: Principles, Methods and Application. New Dehli: SAGE Publications India.

- Newman, Kate, Sowmyaa Bharadwaj, and Jude Fransman. 2019. “Rethinking Research Impact through Principles for Fair and Equitable Partnerships.” IDS Bulletin 50 (1): 21–42. doi:10.19088/1968-2019.104.

- Rasool, Zanib. 2017. “Collaborative Working Practices: Imagining Better Research Partnerships.” Research for All 1 (2): 310–322. doi:10.18546/RFA.01.2.08.

- REF 2021. “2019. What Is the REF?” https://www.ref.ac.uk/about/what-is-the-ref/ Accessed 19 July 2019.

- Schad, Jonathan, Marianne W. Lewis, Sebastian Raisch, and Wendy K. Smith. 2016. “Paradox Research in Management Science: Looking Back to Move Forward.” Academy of Management Annals 10 (1): 5–64. doi:10.1080/19416520.2016.1162422.

- Trussell, Dawn E., Stephanie Paterson, Shannon Hebblethwaite, Xing Trisha M.K., and Meredith Evans. 2017. “Negotiating the Complexities and Risks of Interdisciplinary Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 160940691771135. doi:10.1177/1609406917711351.

- van Hille, Iteke, Frank G.A. de Bakker, Julie E. Ferguson, and Peter Groenewegen. 2019. “Navigating Tensions in a Cross-Sector Social Partnership: How a Convener Drives Change for Sustainability.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (2): 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1684

- Vangen, Siv. 2017. “Developing Practice-Oriented Theory on Collaboration: A Paradox Lens.” Public Administration Review 77 (2): 263–272. doi:10.1111/puar.12683.

- Whyte, William Foote, Davydd. J. Greenwood, and Peter Lazes. 1991. “Participatory Action Research: Through Practice to Science in Social Research.” In Participatory Action Research, edited by William Foote Whyte, 19–55. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Wright, S., and N. Nelson. 1995. “Participatory Research and Participant Observation: Two Incompatible Approaches.” In Power and Participatory Development: Theory and Practice, edited by Nici Nelson and Susan Wright, 43–60. London: ITDG Publishing.