ABSTRACT

Students as partners (SaP) is becoming an increasingly common notion in higher education , but we continue to grapple with questions around how to best involve our students with the work we do as educators. Queries around responsibility, accountability and trust are raised when considering SaP. Participatory action research is presented from an introductory chemistry module in chemical engineering, whereby students were actively involved as partners at various stages of the research, design and development of the module. The action research spanned a 2-year period, accommodating 2 iterations of the module's development. The student partners actively participated in this process in 4 different ways: to set the research agenda (at the beginning), to create suitable formative assessment questions for their peers (ongoing), to manage other students in designing learning tools (as part of the second iteration), and to design and develop appropriate assessment. Some initial structuring was required to establish what the working relationship should look like, but the student partners engaged constructively with the process and added considerable value to reshaping the module. The end result was a more student-focused module, where the student partners had challenged the status quo, used their experiences constructively, and truly empathised with their peers.

Introduction

Background

Students as partners (SaP) was introduced to a piece of action research, in which a core module taught on a degree programme in a higher education institution (HEI) was being redesigned. In introducing this work, it is useful to say something about the problematic nature of the module and how we intended to address this through participatory action research. Our first-year students on a chemical engineering degree are required to be competent at chemistry, and eventually use that chemistry in a chemical engineering context. Observation and on-going discussion suggest that our chemistry module (both content and delivery) fails to teach students how they can make appropriate use of the subject, so needs to be reconceptualised. The focus of the action research centred on shifting the current approach taken to teaching (through the adoption of considered interactive pedagogy), to enable students to make sense of their experiences through activity and discussion, requiring them to critically examine their frame of reference with respect to their knowledge and understanding of chemistry (McGonigal Citation2005; Mezirow Citation2006). Essentially, a step change was required by introducing socio-scientific and critical-reflective ways for students to learn and think about chemistry, whereby the possibilities connected to chemistry and the nature of knowledge itself is questioned (Sjöström and Talanquer Citation2014). The hope is that students create a different relationship with their prior knowledge that enables them to make critical sense of it in a professional context. For example, chemical engineers need to know what questions to ask when selecting the most appropriate buffer for a reaction, or where to position a pH probe in a chemical plant rather than determine pH values per se. A big-picture appreciation is required rather than the linear, atomistic one that students possess coming into university (Blair Citation2016). Difficulties arise though when considering the numbers of students involved, where every class size is approximately 150 students. Several techniques can be used to alleviate the obstacles involved in managing large cohorts, built around a negotiated rather than closed framework of teaching and include activities such as formative quizzes, think-pair-share exercises and class summaries (Brynjolfsson and McAfee Citation2014). Essentially, new educational models are needed that offer more self-initiated, exploratory and independent learning opportunities for students (Price Citation2010).

The work of Jack Mezirow on transformative learning was used as a basis to guide the type of output we wanted (Mezirow Citation1991, Citation1995, Citation2000; McGonigal Citation2005; Mezirow and Taylor Citation2009; Siddiqui and Adams Citation2013). Premise-reflection and independent-thought are key to this process of learning through meaning transformation (Kitchenham Citation2008). For this work, active learning (experiential and discursive) was used to facilitate this transformation, based on the understanding that transformation does not always yield good, positive results, but instead is a slow, step-by-step process (Taylor and Cranton Citation2013). Activating events that expose limitations and discourse are among the necessary strategies for achieving transformative learning (Siddiqui and Adams Citation2013). As part of a novel approach, several active learning strategies were applied simultaneously to develop different habits of thinking (connecting key ideas, defining key terms, researching, contextualising), in efforts to transform students’ understanding of chemistry for chemical engineering, while evaluating the effects of individual and combined interactive pedagogies. The logistical details of the module are provided in .

Table 1. Logistics of the chemistry module taught to chemical engineering undergraduates

Students as partners

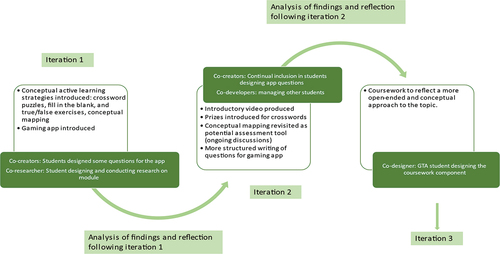

As staff, we appreciate that by teaching the content, we are equally somewhat removed from the ways in which students assimilate information and learn; our knowledge of the subject would only take us so far. Our age and experience constrain our understanding, and therefore there is value in involving students in this process of participatory action research as partners (Matthews Citation2017). Students as partners (SaP) were used in supporting our work in redesigning the chemistry module. In this project, students were involved as partners in four different and distinct spaces as denoted from roles suggested by Healey, Flint, and Harrington (Citation2016). A diagrammatic representation of their involvement is provided as , which highlights the action research process itself and where within that process SaP was utilised. Action research is denoted by the interactive pedagogies and the related processes (e.g. iteration, analysis of finds), while the points of inclusion and engagement with SaP within the action research is highlighted (dark green text boxes).

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of SaP in participatory action research for redesigning chemistry module.

First iteration:

Co-researcher

One of our final-year students partnered with us on this project as a co-researcher. This student was responsible for determining the principal research question (upon understanding the purpose of the work), collecting and analysing data. Questionnaires for students to complete (that encouraged open-text comments) were designed, and the student conducted interviews with both the established and novice lecturer (to establish philosophy and strategy). Additionally, individual student interviews (two in total) were conducted to discuss engagement and impact. The co-researcher student carried out an initial analysis of the data (coding and categorising) and reported their initial findings.

Co-creators

A small group of first year students were recruited to create multi-choice quiz (MCQ) questions for a gaming app. These students were provided with a small bursary and asked to use their notes and carry out some additional research to create questions for each topic that could be used to quickly test the knowledge and understanding levels of their peers. They were asked to help and support one another throughout this process and work as collaboratively as possible.

Second iteration:

Co-creators

During the second iteration, first-year students were again recruited to create questions for the app.

Co-developers

During the second iteration, co-creators were managed by more senior students (two final-year students) to mitigate against possible power relationships developing and encourage greater creativity around question design. These co-developer students were effectively applying managerial skills in using their closer ties with younger peers to facilitate the development process.

During second iteration:

Co-designer (of pedagogy)

A coursework component was introduced during the academic year, which was effectively designed by one of the graduate teaching assistants (GTA) who taught tutorial sessions for the module. This GTA was provided with a brief outline of the essential components of the coursework (for example there had to be a connection between engineering and chemistry, and students should not be able to copy entirely from one another). The GTA accordingly designed the coursework and an appropriate marking scheme.

Literature stipulates students gain valuable experience from active participation (Healey and Healey 2018) and on his occasion additional financial incentives were also in place for them to get involved through a small bursary (either from an institutional or departmental budget) for their participation. A few further considerations had to be borne in mind when engaging with students in this way. Trust plays a major role in this work (Matthews et al. Citation2018); we were keen to select students we felt could be trusted to work effectively with us. The students involved were not driving our initial vision (although contributed to it) but could be trusted to do the very best for their peers through this work. As these students were familiar with the module (having taken it themselves as students), their insights were invaluable, and they were privy to different types of conversations which students will not often have with staff. Power relationships prove interesting in work of this nature, as partnership does not necessarily mean equality in this space (Higgins et al. Citation2019). On a few occasions, we learnt more from the research process when there was a shift in power relationships from staff to student partners. When students are partners in research, the context in which they are involved matters as this affects the actual practice of engagement (Healey and Healy Citation2018). This makes generalisation near impossible, especially given that partnerships are unique and multi-dimensional. In our own example, students worked with other students (as collaborators and managers), as well as staff. Therefore, we are only at liberty to present our case in the hope that others can learn from it as we have learned from others.

Action research methodology

Given the importance of student partnerships, the central research question was: How effective is the utility of SaP in action research? In our particular context we were applying action research to modify the aforementioned chemistry module, with the specific intention to support student transformation. Action research was used to explore transformative change so that interventions could be trialled and reported on, and through a process of trial-and-error and data collection and analysis (spiral process), it would be possible to make definitive changes supporting transformation in learning. Participatory action research was considered the best methodology to make the changes we were looking to (leading to transformative learning) as it encourages researchers and participants to work together to understand a problematic situation and make meaningful changes (Baum, McDougall, and Smith Citation2006). Based on Adelman’s critique of Lewin’s original stance on action research, we agree that the greater gains arise from ‘democratic participation rather than autocratic coercion’ (Adelman Citation1993, 7). Participatory action research has been used to good effect in developing aspects of curricula before now: to hear the critical voices of individuals (Nuttall Nason and Whitty Citation2007), to innovate and create something new for participants (Capobianco et al. Citation2020) and to understand and explore reflective processes pedagogically (Simmons et al. Citation2021). Change can be planned, acted on, observed, reflected on, re-planned and so forth through action research (Kemmis Citation2006). Participatory action research in curriculum design in particular enhances the research experience itself (Kindon and Elwood Citation2009). The authors argue that importantly, researchers play the role of catalysts rather than imposers of change with the right views being represented through this process.

However, we also acknowledge the messy nature of action research, especially in educational settings, which can mean different things to different people in different contexts. For example, Cortez Ruiz raised the difficulty of negotiating various relationships between research, service, action and the learning process in pedagogic action research (Cortez Ruiz Citation2003). A much earlier concern raised was that research can be produced with little action or action can be produced with little research (Foster Citation1972). Relatedly, it is possible to solve one problem with the development process going no further, a concern related to action research aired by Dickens and Watkins (Citation1999). Therefore, we were careful to keep clear notes and to consistently journal the research process in an effort to mitigate the messiness (encompassing both action and research as denoted by the two iterations). The action research was chronological and reflexive in keeping with the traditions of action research (Winter Citation2005). It is somewhat difficult to report real-time, practical action research in the classroom, as this continual cycle of development and reporting is often missed (Winter Citation2005.), but the effort was made none-the-less. Reporting on SaP in participatory action research serves as the main focus of this paper, but the innovations, data and outcomes from the action research process itself are provided as supplementary material, in tabular form (see Table 2, accessible via the Supplemental tab on the article’s home page). This information has been included in a bid to show how we moved onto the next stage of the developmental process (the interactive pedagogies applied, summaries of data collated, and outputs) for those interested in that level of detail. The developments going forward were based on data, and on what literature has suggested encourages transformative learning via interactive pedagogies.

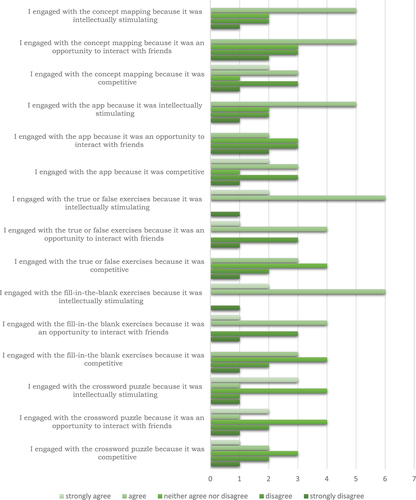

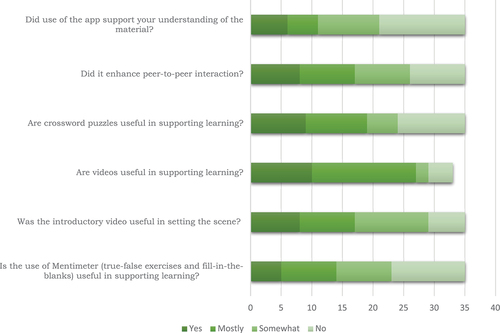

denote quantitative results from student questionnaires following on from iterations 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 2. Student questionnaire responses to items related to the use of interactive pedagogies – first iteration.

Figure 3. Student questionnaire responses to items related to the use of interactive pedagogies – second iteration.

Admittedly, we encountered a few difficulties gathering data from student participants, with small numbers contributing to questionnaires, interviews and focus groups. They were hesitant about getting involved, and sharing their perspectives on how they were getting on with the changes introduced to the module (finding it time consuming). The data itself however was useful and enabled the research team to gain some limited insights that guided our thoughts on further innovation and development, as denoted in Table 2.

Discussion: our reflections on SaP

In discussing this work, we reflect on what we learnt from working with SaP, and what the perceived benefits and challenges have been. This reflexive commentary flowed from natural observation and discussion between the academic staff involved with the module. For the most part, we felt that engaging SaP added value to the design and development of this module. As an example, we could hand over responsibility to students, which in general they coped with exceedingly well, and these students were able to guide our understanding as to how they themselves and other students assimilated information. Perhaps because of their age and initial lack of confidence, the first-year students (co-creators) responsible for creating questions for the app (in iteration 1) did less well than our other student partners in this respect, who required more coaxing to take responsibility and use their initiative. Perceived power relationships, which are often unreported in literature (Coombe et al. Citation2018), might have influenced the reticence of the first-year students. Equally, the time given to students for designing questions was a little unstructured and it has been argued that app questions of this nature take a fairly long time to prepare (Moizer et al. Citation2009) – as a consequence of which other student deadlines became more pressing and student engagement and motivation eventually ceased as they became less engaged with staff or one another as the project progressed. This was unusual as confidence and involvement generally increases in such partnerships (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). During the second year, we changed the dynamic of this peer group by recruiting an equal number of males as females (8 in total), whereas in the previous year 6 males and 1 female participated. Co-developer students who managed the process were also female. This helped to promote gender equality in what is otherwise a male-orientated profession (Acai, Mercer-Mapstone, and Guitman Citation2019). Moreover, we would argue that female involvement resulted in a more structured process and enhanced communication in the working relationships between students themselves going forward. The co-developer students timetabled meetings with the first-year co-creators, set milestones, and ensured the first-year peers were aware of the pedagogical theories that informed good question design (Antunes, Pacheco, and Giovanela Citation2012). The willingness of these co-developers to take on such responsibilities and their skills at managing the process ultimately led to some good questions being produced (greater conceptualisation and less calculation, expanding knowledge rather than repeating it) in a timely manner, which was not the case when staff were solely involved.

The partnership we formulated with the co-researcher student was targeted at encouraging them to take ownership of part of the project, with success very much dependent on the capabilities of the student, and the additional quality of support offered by staff. The nature of the relationship with the student was key in this partnership (less so in other partnerships), as there was a constant ongoing conversation about what type of data to collect, how it might mould future development plans for the module, what criteria informed analysis of data etc. The discussions were useful as they enabled all of us to collectively unpack the strategies used to conduct the research, and establish who had authority to take things forward, and explore these ideas in greater depth (Santos Citation2012). One of the main challenges was in respecting the decisions made by the student and their voice, which has been addressed previously in literature (Groundwater-Smith and Mockler Citation2016). As the student possessed relatively little expertise as an educational researcher, we understood that these decision-making skills were slightly compromised; the initial student questionnaire designed by the co-researcher was redesigned following the first iteration to make it more useful in terms of answering our research question with additional space for open-text comments following each question that invited students to explain responses. However, the student had completed the module 3 years previously to the current cohort, so they were able to use that student experience meaningfully to guide the research process. Equally, they were not personally invested in the findings (unlike the lecturers) and were less exposed to subjectivity and researcher bias (Kirshner, Pozzoboni, and Jones Citation2011).

The student involved in designing coursework was the most independent and capable of the group. We feel their position as a student-teacher enhanced their understanding of the central aims of the module, but also gave them more authority. Challenges certainly exist when student-teachers engage with action research, some of which are related to the self-knowledge they possess as an educator and the time and guidance required to instigate change in the classroom (Ulvik Citation2014). These may be compounded when these student-teachers are also working in partnership with experienced staff who have certain expectations. Designing appropriate coursework for the students was by no means a simple task and the co-designer experienced difficulties with balancing this commitment with their doctoral work. However, we felt they were able to grow through this process, and again their empathy with the students enabled them to understand assessment in a way staff could not, for example by tapping into the true level of students’ abilities and work ethic and balancing those with the average amount of time students invested in coursework.

Notions of student accountability surfaced throughout this process in which we effectively recruited students in teacher roles. Cook-Sather asks an interesting question of those of who work in partnerships with students – what does it take for students to be both responsible and accountable? (Cook-Sather Citation2010). She argues that students need to be actors rather than acted upon. Students were able to establish different sets of standards and measures on other students that staff often give less attention to. For example, the two co-developer students created different expectations of the first-year co-designer students by introducing targets, a different work ethic etc. furthermore, agency about making choices becomes relevant when considering accountability. For example, the co-designer student who designed the coursework, and associated marking scheme, made constructive use of the experience to better understand his role and beliefs as a teacher, and applied for an accredited award in teaching. As part of his narrative he was asked to reflect upon accountability, with assessment processes and procedures often revealing hidden truths on the matter (Schnellert, Butler, and Higginson Citation2008).

On reflection, we found that the better contributions came from students when they could challenge the relationships they formed with staff and their place within them. If students are passive in such partnerships, then the process of design, development or research can be frustrating as the vision and end-goal remain static, which can prove unhelpful if the desired outcomes is a better learning experience for students (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014). We found this was the case with the first-year co-creator group, although the co-researcher, co-developers and co-designer students used the space to openly question the process, their involvement and what we were trying to achieve. Consequently, staff views and understanding shifted in a meaningful way to take onboard some of the perspectives offered by the student partners. Throughout the research process, the students we worked with seemed to gain credibility and greater confidence in a discipline area that they were not familiar with (they were all students in chemical engineering after all). As staff, we actively listened to these students as best we could and explored the ideas they presented (for example the co-researcher had initially suggested concept mapping as a low-stakes assessment). Hopefully, this credibility also provides them with the confidence to acknowledge their knowledge, understanding and experiences as useful (Davis and Parmenter Citation2021).

Conclusions

By engaging with SaP in this action research project, meaningful use was made of students that resulted in us redesigning a core module that better fitted the student learning experience. Admittedly, the process was not without its teething problems – with younger, less experienced students finding the process somewhat challenging. We needed to exercise caution in the students selected as partners as trust plays an important role. Equally, these students needed to understand and internalise their own sense of responsibility and accountability. However, these students were able to use their voice powerfully to challenge what we did as teachers, and could use their own experiences in an empathetic manner to support their peers through a process of discovery. The net result was a deeper and richer understanding of how students really connect with their learning, and therefore what facilitates that process. As an end note, it is hoped that this work encourages others to fully explore their teaching through action research methodologies that widely engages SaP to create effective change through a slow, documented process of iteration.

REAC-2021-0102.R1_Table_2_Supplemental.docx

Download MS Word (18.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2022.2058974

References

- Acai, A., L. Mercer-Mapstone, and R. Guitman. 2019. “Mind the (Gender) Gap: Engaging Students as Partners to Promote Gender Equity in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1696296.

- Adelman, C. 1993. “Kurt Lewin and the Origins of Action Research.” Educational Action Research 1 (1): 7–24. doi:10.1080/0965079930010102.

- Antunes, M., M.A.R. Pacheco, and M Giovanela. 2012. “Design and Implementation of an Educational Game for Teaching Chemistry in Higher Education.” Journal of Chemical Education 89 (4): 517–521. doi:10.1021/ed2003077.

- Baum, F., C. McDougall, and D. Smith. 2006. “Participatory Action Research.” Journal of Epidemiology and Health 60 (10): 854–858. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.028662.

- Blair, A. 2016. “Understanding First-year Students’ Transition to University: A Pilot Study with Implications for Student Engagement, Assessment and Feedback.” Politics 37 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1177/0263395716633904.

- Brynjolfsson, E., and A. McAfee. 2014. The Second Machine Age. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Capobianco, B.M., D. Eichinger, S. Rebello, M. Ryu, and J. Radloff. 2020. “Fostering Innovation through Collaborative Action Research on the Creation of Shared Instructional Products by University Science Instructors.” Educational Action Research 28 (4): 646–667. doi:10.1080/09650792.2019.1645031.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2010. “Students as Learners and Teachers: Taking Responsibility, Transforming Education, and Redefining Accountability.” Curriculum Inquiry 4 (40): 555–575. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2010.00501.x.

- Coombe, L., J. Huang, S. Russell, K. Sheppard, and H. Khosravi. 2018. “Students as Partners in Action: Evaluating a University-wide Initiative.” International Journal for Students as Partners 2 (2): 85–95. doi:10.15173/ijsap.v2i2.3576.

- Cortez Ruiz, C. 2003. “Learning Participation for a Human Development Approach .” In Paper Prepared for the International Workshop on Learning and Teaching Participation in Higher Education, IDS, International Institute for Environment and Development (ed), 2–4 April 2003. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 47–51 .

- Davis, C., and L Parmenter. 2021. “Student-staff Partnerships at Work: Epistemic Confidence, Research-engaged Teaching and Vocational Learning in the Transition to Higher Education.” Educational Action Research 29 (2): 292–309. doi:10.1080/09650792.2020.1792958.

- Dickens, L., and K. Watkins. 1999. “Action Research: Rethinking Lewin.” Management Learning 30 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1177/1350507699302002.

- Foster, M. 1972. “An Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Action Research in Work Organizations.” Human Relations 25 (6): 529–556. doi:10.1177/001872677202500605.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., and N. Mockler. 2016. “From Data Source to Co-researchers? Tracing the Shift from ‘Student Voice’ to Student–teacher Partnerships in Educational Action Research.” Educational Action Research 24 (2): 159–176. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1053507.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. York: Higher Education Academy.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2016. “Students as Partners: Reflections on a Conceptual Model.” Teaching & Learning Inquiry 4 (2). doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.3.

- Healey, M., and R. Healy. 2018. “It Depends”: Exploring the Context-dependent Nature of Students as Partners’ Practices and Policies.” International Journal of Students as Partners 2 (1): 1–10. doi:10.15173/ijsap.v2i1.3472.

- Higgins, D., A. Dennis, A. Stoddard, A.G. Maier, and S. Howitt. 2019. “Power to Empower’: Conceptions of Teaching and Learning in a Pedagogical Co-design Partnership.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (6): 1154–1167. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1621270.

- Kemmis, S. 2006. “Participatory Action Research and the Public Sphere.” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 459–476. doi:10.1080/09650790600975593.

- Kindon, S., and S. Elwood. 2009. “Introduction: More than Methods – Reflections on Participatory Action Research in Geographic Teaching and Learning.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 33 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/03098260802276474.

- Kirshner, B., K. Pozzoboni, and H. Jones. 2011. “Learning How to Manage Bias: A Case Study of Youth Participatory Action Research.” Applied Developmental Science 15 (3): 140–155. doi:10.1080/10888691.2011.587720.

- Kitchenham, A. 2008. “The Evolution of John Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory.” Journal of Transformative Education 6 (2): 104–123. doi:10.1177/1541344608322678.

- Matthews, K. E. 2017. “Five Propositions for Genuine Students as Partners Practice.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (2). doi:10.15173/ijsap.v1i2.3315-20.

- Matthews, K.E., A. Dwyer, L. Hine, and J. Turner. 2018. “Conceptions of Students as Partners.” Higher Education 76 (6): 957–971. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y.

- McGonigal, K. 2005. “Teaching for Transformation: From Learning Theory to Teaching Strategies.” Speaking of Teaching 14 (2).

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., S. L. Dvorakova, K. E. Matthews, S. Abbot, B. Cheng, P. Felten, K. Knorr, E. Marquis, R. Shammas, and K. Swaim. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of Students as Partners in Higher Education.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (1). doi:10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119.

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey Boss.

- Mezirow, J. 1995. “Transformative Theory of Adult Learning.” In Defense of the Lifeworld, edited by M. Welton. Albany: State University of New York Press, 39–70 .

- Mezirow, J. 2000. “Learning to Think like an Adult: Core Concepts of Transformational Theory In.” In Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress, edited by J. Mezirow, Associates. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 3–33.

- Mezirow, J. 2006. “An Overview of Transformative Learning.” In Lifelong Learning: Concepts and Contexts, edited by P Sutherland and J Crowther. New York: Routledge, 90–105.

- Mezirow, J, and E.W. Taylor. 2009. Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace and Higher Education. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons .

- Moizer, J., J. Lean, M. Trowler, and C. Abbey. 2009. “Simulations and Games: Overcoming the Barriers to Their Use in Higher Education.” Active Learning in Higher Education 10 (3): 207–224. doi:10.1177/1469787409343188.

- Nuttall Nason, P., and P. Whitty. 2007. “Bringing Action Research to the Curriculum Development Process.” Educational Action Research 15 (2): 271–281. doi:10.1080/09650790701314916.

- Price, C. 2010. “Why Don’t My Students Think I’m Groovy? The New ‘R’s’ for Engaging Millennial Learners, Essays from E-xcellence in Teaching.” Psych Teacher Electronic Discussion List, edited by S.A. Meyers and J.R. Showell. chapter 6: 2934. Vol. IX, 29–34 .

- Santos, D. 2012. “The Politics of Storytelling: Unfolding the Multiple Layers of Politics in (P)AR Publications.” Educational Action Research 20 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1080/09650792.2012.647695.

- Schnellert, L.M., D.L. Butler, and S.K. Higginson. 2008. “Co-constructors of Data, Co-constructors of Meaning: Teacher Professional Development in an Age of Accountability.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (3): 725–750. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.04.001.

- Siddiqui, J.A., and D. Adams, (2013), The Challenge of Change in Engineering Education: Is It the Diffusion of Innovations or Transformative Learning? Proceedings of the ASEE Conference, Atlanta, Georgia, 23-26 June

- Simmons, M., M. McDermott, S.E. Eaton, B. Brown, and M. Jacobsen. 2021. “Reflection as Pedagogy in Action Research.” Educational Action Research 29 (2): 245–258. doi:10.1080/09650792.2021.1886960.

- Sjöström, J.A., and V. Talanquer. 2014. “Humanizing Chemistry Education: From Simple Contextualization to Multifaceted Problematization.” Journal of Chemical Education 91 (8): 1125–1131. doi:10.1021/ed5000718.

- Taylor, E.W., and P. Cranton. 2013. “A Theory in Progress? Issues in Transformative Learning Theory.” European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 4 (1): 33–47. doi:10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela5000.

- Ulvik, M. 2014. “Student-teachers Doing Action Research in Their Practicum: Why and How?” Educational Action Research 22 (4): 518–533. doi:10.1080/09650792.2014.918901.

- Winter, R. 2005. “Some Principles and Procedures for the Conduct of Action Research.” In New Directions in Action Research, edited by O Zuber-Skerrit, 9–22. London: FalmerPress.