ABSTRACT

This study is a researcher-practitioner action inquiry which was used to explore children’s sensory experiences with a focus on the sense of smell (olfaction). We critically considered the early childhood theories that positioned children's sensory learning within equitable, socially just early childhood approaches and connected them to an action inquiry approach. The data comprise a systematic documentation of the odours experienced by children in the classroom, an olfactory log of the kindergarten space as well as children’s ‘smellmaps’ from outdoor ‘smellwalks’. We interpret children’s olfactory experiences and reflect on the ways in which the multi-sensory approach to literacy might extend the field’s understanding of the multi-dimensional ways in which educational researchers and practitioners can cultivate their joint inquiries in early childhood education. We present implications for adopting an olfactory researcher-practitioner collaboration in early childhood and conclude that such an approach exemplifies a sensorially sensitive early childhood curriculum.

Introduction

The sense of smell is, together with taste and proprioception, a hidden sense that has been neglected in educational research and practice. Despite the strong predictive value of olfaction for a range of infections (e.g. COVID19), degenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s), mood disorders (e.g. depression) and its important social role in religious and medicinal contexts (see Majid Citation2021), the sense of smell has been little researched for its learning and educational qualities. We spotlight olfaction in the education space and explore its role in children’s meaning-making in early childhood classrooms. Our approach is commensurate with a recent turn to sensory, spatial and embodied educational approaches that are responsive to the socio-material entanglements of children’s learning in local and global environments (Mills, Unsworth, and Scholes Citation2022). In particular, sensory learning, which is about the engagement of all six senses (vision, hearing, touch, smell, taste and proprioception, see Kucirkova Citation2022), aligns with our focus on the olfactory sense. Socio-spatial and embodied modes of learning that refer to children’s relational, reciprocal bodily responses with space and its inhabitants (e.Thyssen and Grosvenor Citation2019), connect to our emphasis on olfactory spaces, or ‘olfactoscapes’, in early childhood classrooms.

We argue that olfaction, together with its close cousin gustation (sense of taste), are vital for the ‘central processes of teaching, learning and leading as human and socially constructed. They are a strong reminder of the power of emancipatory action and its particular suitability for addressing the challenges we are facing in our complex world today’ (McLaughlin Citation2020, 722,). The sensory perspective on literacies builds a more inclusive and informed picture of how all children, including those with learning difficulties, experience literacies. Pool, Rowsell, and Sun (Citation2023) make this point by describing the multiple modes and sign systems that children use when making meaning in classrooms. By privileging sensory literacies, rather than conventional schooling practices of language- or script-based literacies, Pool, Rowsell, and Sun (Citation2023) highlight the socially just, inclusive and equal aspect of multimodal, sensory research: ‘This type of research felt more modally equal to us than our previous research in that we had to pay more, closer attention to the orchestration of different modes and senses such as smells, sounds, colours, and attention to the assemblages of sensory conditions’ (online). In developing our argument, we draw on sensory literature and our experience of an action inquiry, which we undertook as part of a small-scale action research project concerned with children’s sense of smell. The approach enabled us to implement an olfactory inquiry in a Norwegian kindergarten and through a focused action research approach, raise the olfactory awareness of staff, children, and their community.

Aims and objectives

We aimed to investigate and facilitate children’s olfactory experiences and reflect on the ways in which the approach might extend our understanding of the constellations of teachers’ choices in facilitating children’s sensory opportunities. Our objective was to consider both experiential and instructional aspects of olfactory experiences and provide suggestions for the multi-dimensional ways in which educational researchers and practitioners might collaborate to cultivate their olfactory inquiries in early childhood education.

Our action inquiry was guided by two main research questions:

How might we develop olfaction as a focused area of inquiry in the context of early childhood research?

How does the participation in an olfactory action inquiry shape our professional identities as an educator and as a researcher?

To answer these questions, we adopted an action inquiry approach that we structured in three cycles: 1, exploratory stage during which we mapped the olfactory profile of the kindergarten; 2, implementation stage during which we applied olfactory activities into practice and 3, reflexive shifts during which we shared insights into how we reconnected theory and lived experiences with our practice. While the first and second cycles occurred consecutively, the third stage was woven throughout the action inquiry. We describe each cycle separately in order to simplify the reporting structure of a complex dynamic endeavour.

The article is structured in three sections. First, we critically consider the research theories that position children’s sensory learning within equitable, socially just early childhood approaches and we reflect on their contribution to an action inquiry approach. We outline our rationale for focusing on olfaction as a strategy to advance sensory learning in early childhood classroom and equitable learning opportunities. Second, we inspect and document the practice we followed in establishing the olfactory profile of a kindergarten, and in integrating an olfactory emphasis with the kindergarten’s daily curriculum. Ethical considerations and our reflexive story are woven throughout the paper. A theme prominent in our reflections is the power of action inquiry in facilitating research-practice knowledge-sharing in a new curriculum area. We conclude with recommendations for future action research that capitalises on theory-research-practice entanglements that, we propose, are conducive to rich children’s olfactory learning experiences.

Multi-sensory research and olfaction

Educational action research is concerned with a rich array of areas of inquiry, including children’s sensory engagement in classrooms (e.g. Nunes and Oliveira Citation2022; Percy‐Smith and Carney Citation2011; Rose, Vaughn, and Taylor Citation2015) but an action research study concerned with an olfactory inquiry is missing. While the olfactory sense has been considered the sense of future in academic and industry circles for centuries, scholarly investigations of smell are relatively recent (Vosshal Citation2019). Experimental studies have shown that changes in odours in a given environment influence the attitudes and behaviour of adults (e.g. Turley and Milliman Citation2000). The connection between autobiographical memories and specific odours has been recognised in creative writing (e.g. Proust Citation2013), and also confirmed in neurological research. The latter shows a connection between autobiographical memories and olfactory cues (Herz et al. Citation2004). The learning benefit of increased awareness of smell is also indicated in studies that show a brain connection between spatial memory and olfactory identification (Dahmani et al. Citation2018). However, despite the learning potential of olfaction, the educational research on olfaction is largely lagging behind. And yet, as Thomas (Citation1990) pointed out, even simple activities such as burning autumn leaves has an impact on our perception of the world and carries educational implications: ‘An autumn curbside bonfire has everything needed for education: danger, surprise (..), risk, and victory over odds (…), and above all the aroma of comradeship’ (Thomas Citation1990, 281).

Smells, odours and aromas are ephemeral, volatile and in constant flux, and as such, are easy to overlook and difficult to capture in everyday environments. Researchers have been trying to develop a more sophisticated knowledge of the right methods to accurately detect and identify smells, white taking into account biological differences and environmental influences in olfactory perception (Candau Citation2004; Herz Citation2010). Building on the interest in smell in natural sciences and the homogenising impact of educational approaches that privilege linguistic, visual and verbal forms of children’s knowledge representation (see Osgood and Mohandas Citation2022 for a comprehensive critique), we framed our olfaction action inquiry within critical theories in early childhood research.

Theoretical framework for the study: critical early childhood theories

Our initial foray into the uncharted waters of olfactory inquiry was inspired by a social justice agenda pursued by critical early childhood theorists (see e.g. Nordström, Kumpulainen, and Rajala Citation2021; Ritchie Citation2016; Rodriguez Leon Citation2021). The work of these colleagues and our own previous work, mark a departure from normative, linguistically and socially constraining approaches to early childhood research. Critical early childhood theorists challenge the dominance of visual and verbal meaning-making modes with a mobilisation of multi-sensory, embodied and socio-material practices. Our focus on olfaction illustrates a distinct case in multi-sensory research that needs to be placed in the wider early childhood theories. More specifically, our olfactory inquiry was animated by two concepts in critical literacy theories: posthumanism and embodiment.

Badwan’s (Citation2021) posthumanist and affective insights into children’s multi-sensory, modal and lingual meaning-making are integral to our interest in the complex socio-material opportunities in sensory learning. Badwan (Citation2021) is concerned with the questions of children’s agency, justice and equity and builds on Barad’s (Citation2007) seminal work and contention that it is the in-between-ness of humans and non-humans that enacts change in the material world. This work informed our positioning of olfaction at the intersections and interactions of humans and the material world. More specifically, we connected our action inquiry to the theoretical proposition that smell can shift perspectives and open up connections to spaces where human and non-human entities are enmeshed and entangled in an inter- and intra-action.

The embodiment literature has established that the body is not an object (Merelau-Ponty Citation1968, Citation2012) and that a holistic understanding of the world relies on a multi-sensory integration. The relational and dynamic connection to nature allows us to see children’s corporeal boundaries differently and invites scholars to consider the lived experience of smells, scents and aromas. Mobilising the embodiment theory, critical literacy scholars have pointed out that ‘The meanings that we make through language and thought cannot be separated from our everyday experiences as bodies in the world’ (Sefton-Green et al. Citation2016, 13). The re-configuration and contestation of taken-for-granted assumptions regarding the dominance of the visual sense in learning and verbal expression of knowledge requires a paradigm shift that would cut into the fabric of early childhood practice. As such, our ethical position on equitable learning opportunities and the social justice agenda intersects with critical literacy theories that address the dominance of visual and verbal meaning-making modes.

The embodiment and critical literacy theories refined our thinking on the extent to which classroom spaces provide impoverished affordances for multi-sensory embodied learning. Subsequently, the methodologies of critical ethnographic researchers (e.g. Hackett Citation2021), which open the field to a close study of children’s movements, individual senses (notably sounds and engagement in ‘soundscapes’, see Gallagher et al. Citation2017), provided the pointers for developing our olfactory action inquiry. While our objective was to make a change to practice, we also engaged in the dialogical tension of recognising the complexity of documenting experiences that are ‘embodied, transitory, wriggly and difficult to put in a box and separate out from everything else’ (Sefton-Green et al. Citation2016). We approached the task as an appreciative, critical, creative and collaborative reflective practice (see Sharp and Balogh Citation2021), following the tradition of action research.

Action research and action inquiry

Action research is an effort to negotiate knowledge, and jointly establish a solution to issues and problems that arise from practice, collective action and self-reflection (Avison et al. Citation1999). Our motivation for following the action research approach stems from the desire to empower the field with ‘the courage to take a close and critical look at our own practice and to go against the mainstream if necessary’ (Editors with Petra Ponte and Editors with Citation2006, 457). Action research encompasses an umbrella of approaches, including participatory research, design methodologies or action inquiries. We selected action inquiry, which is distinct from general action research in that action researchers simultaneously pursue action and inquiry (Torbert Citation2006). Action inquiry is similar with standard action research in that it is subjective as well as dialogic and inter-subjective, and premised on ethical and aesthetic commitments of the action researchers (Torbert and Taylor Citation2008).

The action inquiry method grew from organisational studies (see Cacioppe and Edwards Citation2005), but has been widely applied in educational research (e.g. McKim and Wright Citation2012). In Norway, which is the context for our work, Helskog (Citation2015) developed her action inquiry with a Dialogos approach. Overall, the process and reporting structure of an action inquiry vary and depend largely on the authors’ experience, acquaintance with the literature and background.

Ethics and positionality

One of the authors is a professor in early childhood education and the other is an early years practitioner, who has recently left the kindergarten sector and become a doctoral student. Our action inquiry presented in this paper is not an empirical research article in the traditional sense of reporting primary data, nor is it a report of exemplary or best practice. Rather, we capitalise on the joint learnings we made over a year of a researcher-practitioner collaboration, and offer an authentic response to the challenge of embodying a neglected area in early childhood practice. Our collaboration was driven by the desire to create a change in how research and practice are connected in relation to olfaction, and embark on an ‘intentional, effective, transforming, timely action inquiry in the midst of everyday life’ (Torbert Citation2004, 7).

Here, ethical considerations that are particular to action research relate to ‘positionality’, or the distinction between researcher and researched and researcher and practitioner (McNiff Citation2013, Citation2016). The boundaries needed to be negotiated and enacted in practice, with a great deal of transparency and integrity of all involved. In our project this was achieved through open communication, mutual respect for each other’s role and genuine interest in learning from each other. Action research as an educational approach has a long tradition in the Nordic countries, and is considered part of professional development of teachers, in an ongoing effort of ‘re-professionalisation’ that aims to support mutual learning between researchers and practitioners, support better practices and thus better democratic societies (Rönnerman, Furu, and Salo Citation2008).

In what follows, we summarise the lessons learnt from three cycles of our small-scale action research: 1, creating an olfactory profile of the kindergarten; 2, implementing olfactory activities into practice and 3, reflexive account of connecting theory and practice in a professional development partnership.

Materials and methods

Study procedure

Our researcher-practitioner collaboration corresponds to the description of the Nordic variant of educational action research tradition as ‘a messy and aesthetically sensitive inquiry’ (Blomgren Citation2019, 768), in that we addressed challenges when they arose and were attuned to the embodied, creative and aesthetic forms of children’s expression.

In our previous study (Kucirkova and Kamola Citation2022), we solicited olfactory perceptions from the children, who were invited to use various multi-sensory materials and create stories with olfactory references. In subsequent parts of the project, the teacher’s perspective and her own data interpretation were central to the research advancement. The teacher opted for being named in the communication about the study and in recognition of her contribution, to be a co-author of research papers resulting from the project. Reflective research journal and a serious commitment to reflexivity were adopted by both authors, in alignment with best practice recommendations on action research (McNiff Citation2013) and on being a reflective practitioner (Schon, Citation1987). Both the researcher and practitioner conducted an olfactory audit of the kindergarten and we compared our olfactory perceptions, their sources and intensities.

Both the researcher (Natalia) and practitioner (Monika) aimed to advance their understanding of the power of action research in impacting the sensory, embodied and spatial experiences of children in early childhood settings. We based our reflections on our reflection logs, fieldnotes and empirical data collected in the kindergarten, Following the standard multi-cycle model of an educational action research, we followed the methodological steps of plan, reflect, act and observe, re-plan, reflect, act and observe (Phillips and Carr Citation2014) in the first two cycles. The third cycle has been an open and ongoing process of action learning/action research (see Zuber-Skerritt Citation2018) with iterative capacity building and participatory pedagogies.

The study context

The Norwegian national curriculum plan (Rammeplan for barnehagen) is based on strong democratic values and emphasises equal opportunities for children’s socio-emotional and cognitive development (Udir Citation2017). Early childhood practitioners are expected to engage in planning, observation and documentation of children’s experiences and these are expected to be anchored in play, outdoor learning and safe adult-child relationships (Alvestad et al. Citation2019). The framework is intended to be a guiding, not prescriptive document, and as such is open to considerable interpretation by teachers, with a significant variation in quality provision across Norwegian kindergartens (Rege et al. Citation2018).

In the kindergarten where Monika worked at the time of the study, the national curriculum was followed for planning daily activities and as an overall guide for setting the values and ethos upheld by both the children and staff.

The kindergarten was located in a small city in Norway, and was owned by the local municipality. At the time of the study, there were four adult employees, and 19 children registered for attendance. The main focus in our study was the classroom with the eldest children, where Monika worked as the classroom lead. In total, one adult (Monika) and 19 children, 9 boys aged between three to six years old and 10 girls aged between three to six years participated in our action inquiry.

Natalia visited the kindergarten in the winter semester in 2021 and performed an initial olfactory analysis of the classroom and related outdoor area. She discussed the results with Monika, who conducted her own analysis in June 2022. The Findings section below provides a summary of our joint observations. The implementation part in Cycle 2 draws on ideas that we jointly conceptualised and that Monika implemented in her classroom.

Findings

Cycle 1: Documentation of olfactoscapes

Olfactory profile of the kindergarten

In order to understand which odours, aromas and smells children are exposed to on a daily basis, we needed to document the natural occurrence of odours in children's everyday classroom environment. To this end, we created an olfactory profile of the kindergarten based on a systematic recording of odours present inside the classroom and in the kindergarten outdoor area; a review of resources and activities as available during the day of the observation and a review of kindergarten plans in light of sensory-informed practice.

The review of the kindergarten’s written plans for daily, weekly and yearly activities revealed that the kindergarten had some ongoing activities that included references to smell. For example, every year in December, the staff and children baked together Christmas cookies and gingerbread with an explicit aim to talk about Christmas scents (typically these include cinnamon and clove). There was no other reference to smell in the yearly plans, however. While there was a clear expectation to stimulate children’s haptic, visual and hearing senses, the chemosenses (smell and taste) were not included in the planning. summarises the activities and resources that were available during our observations or that were planned by the kindergarten staff for stimulating children’s sensory engagement throughout the year.

Table 1. A summary of activities and resources categorised according to individual senses.

The lack of olfactory references in the kindergarten’s planning and daily activities was not atypical of a standard early childhood setting. Although the sensory, affective and aesthetic practices are higher in early childhood settings that follow the Montessori and Steiner tradition (Johnson Citation2014 but see Osgood and Mohandas Citation2022), typical Western early childhood classrooms do not foreground sensory learning.

Dedicated activities can increase the presence of smells in a given environment, because smells are universal sensorial components that are present everywhere (Hirsch Citation2009). It was therefore important to us to systematically document the presence of odours that naturally occur in the kindergarten space. To this end, we developed an ‘olfactory log’, which consisted of time-stamped recordings of the presence of specific odours at a given moment in time and space, with an estimation of the odour’s source, intensity and whether it was adult- or child-initiated. Both the researcher and the practitioner created an olfactory log with the aim to systematically document the presence of odours in the setting. Extracts from both the researcher’s and teacher’s olfactory logs (in Norwegian) are included in Appendix. The length of the olfactory observation can vary depending on the research purpose, and in our case the audit lasted one full day when completed by the researcher and one morning session when completed by the teacher. We relied on our own olfactory abilities to detect naturally occurring smells.

The various odours that we both recorded included the food items served for the children’s breakfast (milk, bread/cereals), but also rain, urine, soap, paper or cleaning products. In addition, there were some differences: for example, the teacher noticed a strong presence of nail varnish after one member of staff painted children’s nails, while the researcher noted a strong presence of alcohol inside a disinfectant. The differences in odour detection and intensity perception can be explained with the different observation days and natural odour variation across space and time (see Gottfried Citation2010; Stevenson Citation2010) but also significant inter-individual differences documented in olfactory research (Danthiir et al. Citation2001; Herz and Inzlicht Citation2002).

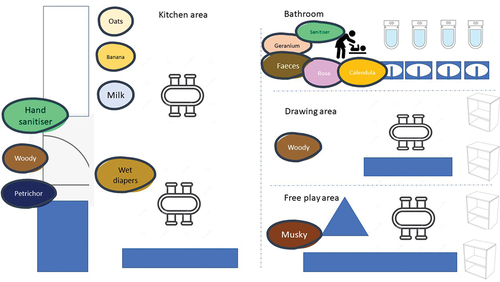

In addition to an olfactory log, the researcher produced an olfactory map, which is a snapshot of the key odours present in the main kindergarten space at 8:15 AM of the researcher’s observation. The olfactory map in provides a visual representation of the odours’ presence and illustrates the high concentration of odours in the kitchen and bathroom areas and relatively low odour concentrations in the drawing and play areas (the size of the bubbles represents the odours’ intensities) .

Figure 1. Visual representation of the intensities and presence of various odours in the kindergarten.

The systematic coding of odour presence and intensities raised our awareness of the odours in a given space and established the baseline for evaluating children’s current and possible olfactory experiences. Furthermore, the at-a-glance visual view of the kindergarten’s profile helped us understand the spatial configurations and concentrations of odours and recognise children’s and adults’ role in influencing these. We took these insights into cycle 2 of the project, in which we implemented research-informed olfactory activities into practice.

Cycle 2: Research-informed expansion of olfactoscapes

We discussed the research literature as the project was progressing and reflected on possibilities for translating research recommendations into daily kindergarten practice. For the researcher, the teacher’s reflections on children’s engagement in olfactory activities provided an impetus to recommend resources for practical experimentation in the classroom. Following our discussion of a research article regarding the need to increase children’s olfactory awareness, Natalia suggested that Monika tries out an olfactory memory game with the children. To this end, we bought the Montessori game ‘Box with smells’ (Les boîtes à odeurs, available from Nature & Decouvertes, France) with which children can smell a container enhanced with an aroma and match the aroma to an image (similar to a standard memory matching game but with odours).

In her reflection log, the teacher (Monika) noted children’s enjoyment of the game and the way it allowed a boy to demonstrate his olfactory knowledge. This boy did not name any odours but was very skilled at matching the odour-enhanced containers with their respective images. ‘Box with smells’ ended up being the boy’s most favourite activity which he would choose inviting to play both adults and other children. Exploring olfaction together with others helped framing of and his participation in the game which provides him with another role, possibility etc.

The game integrated group of children as there was an opportunity to share each other’s experience of discovering smells and learning new words from images. Body language was prominent in communication during the play, mostly facial expressions. Playing with aromas let children realize their competencies and smelling abilities and contribute to the group with interesting comments about how they liked different aromas or how their memories connected to different smells. The teacher also observed that ‘The box with smells’ was a great stimulus for concentration, especially for children who struggled with self-regulation.

Drawing a distinction between personal and spatial odours, the teacher has noted the strong perfumes worn by some staff members and some children’s parents. She also noted that some odours were carried by the staff members moving across the kindergarten setting, from one room or one kindergarten department, to the other. In addition, there was a discernible odour difference between the individual rooms. Namely, within the older children’s department, the play and bathroom area were permanently characterised by different smells and the youngest children department (creche) and older children department clearly differed in how intense the diaper smell was when entering the space. As for the temporal dimension, in her reflection log, the teacher wrote that while the presence of strong food odours in the morning was temporary, the odours of cooked lunches lingered for longer in the kindergarten premises.

The teacher’s increased olfactory awareness that developed through the action inquiry was reflected in children’s activities and discussions. The teacher noted that the children talked more often about smell in their role-play activities and also in their direct communication with staff. As an example, a child who picked up a flower in the playground and brought it inside commented that this was to ”bring in a nice smell”. Anecdotal reports from other members of staff revealed that families positively commented on the children’s increased interest in odours and that their journeys to the kindergarten had been enriched with family conversations about various smells in the neighbourhood.

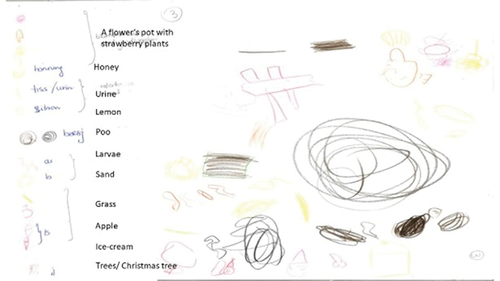

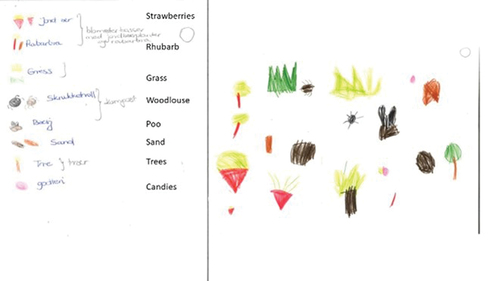

The teacher and researcher discussed these observations and engaged in further cycle of planning and observing. This next iteration cycle concerned the awareness- raising of olfaction in the kindergarten and the organisation of a ‘smellwalk’. Following the researcher’s suggestion, the teacher organised a smellwalk during which children mapped their olfactory perceptions of the neighbourhood. The smellwalk was part of the kindergarten’s daily routine of taking the children for a walk outdoors and let them freely explore the local environment. Out of the 19 children participating in the study, nine children took part in the smellwalk activity. The teacher divided the children into three groups of three children per group, with two groups of girls and one group of boys. Each group was provided with coloured crayons and one big blank paper ark (one ark per group). The teacher encouraged the children to walk, pay attention to what they smell and draw down what they remember they had smelled. The walk took about 20 minutes per group. Some children drew what they smelled as they walked around, while others made their drawings after they had finished the walk. For example, the children who walked past planting boxes drew the smell of strawberries, flowers or honey, while those who walked past a compost bin drew the smell of ‘poo’ and woodlouse. Some children were reminded of the smell of a Christmas tree when they smelled a wooden staircase. After the activity, the children were asked to share their thoughts and reactions verbally with the teacher and other children. Most of the children expressed that they enjoyed the activity and found it to be a fun and interesting way to explore their sense of smell. Some of the children said that they were surprised by how many different smells they encountered and how vividly they could recall them when they were drawing. Other children were curious to learn more about the plants and flowers they could smell during the walk and wanted to explore their characteristics further.

contain children’s drawings with a legend that explains the individual colours/objects that the children described to the teacher after the activity. The drawings were made by the children, the legend was added by the teacher.

As we jointly reflected on the children’s smellmaps, we noted their added value in revealing the children’s sensory perceptions that we would otherwise have missed. The children’s use of bright colours, notably the dominant choice of red, yellow, green and brown, indicated that colour-odour correspondences might be as common among children as they are among adults (see Maric and Jacquot Citation2013). The children’s conscious and consistent choice of bright colours for fruity odours and dark colours for earthy aromas aligned with colour-odour cross-modal associations noted by researchers investigating art and design projects (Spence Citation2020). The teacher commented that the boys’ odour representations were often less concrete in colour and shape than the girls’ ones. This observation is in line with accumulating evidence that suggests that there are gender differences in odour recognition/identification, in favour of girls (e.g. Ferdenzi et al. Citation2008). For some odours, women react with greater affective responses than men (Olofsson and Nordin Citation2004), which has been justified with both biological and cultural reasons (Majid Citation2015, Citation2021). The rich data generated by the smellwalk and our discussion of their documentation compel us to recommend smellwalks as an exciting tool that has the potential to manifest children’s diverse olfactory perceptions and preferences.

Cycle 3: Reflexive stories

The third cycle of our action inquiry is a work-in-progress reflexive story of our researcher-practitioner experiences that constitute the emerging repertoire of olfactory early childhood practice. Our recommendations in this section rely on a broader analysis of our and related practice and are presented as a form of self-reflection, which, as Hopkins (Citation1985) outlined, can be the catalyst in improving a social practice. In the case of the teacher, the strategies of conducting an olfactory audit, engaging in olfaction-focused activities such as planning and implementing smellwalks and odour games, had turned into tentative guidelines for sharing best practice but also further self-reflection, monitoring, reviewing and evaluating outcomes (cf Ghaye et al. Citation2008). In the case of the researcher, the knowledge co-construction through a mutually informing process of knowledge exchange between practice and academia was the prima facie and actual motivation for engaging in an action research project (see Arhar, Holly, and Kasten Citation2001). Perhaps not surprisingly, the simultaneous engagement in acting and inquiring brought about an ongoing reflection on a suite of ethical dilemmas.

Researcher-practitioner exchanges and joint learnings

Given that the educational potential of the sense of smell has been understudied, our methodological approach was tentative and exploratory. We did not aim to create an absolute or exclusive image of the olfactory profile in a Norwegian kindergarten but rather to support professional development in olfactory education with a snapshot of odours that we could detect. Although Natalia pursued a perfumer course and a systematic training in fragrance detection and smelling, we did not have any established tools ready to adopt for our olfactory action inquiry. Our findings are thus our best attempt to capture the lived and authentic olfactory experiences of children in a local area, and our interpretation of this experience. When discussing and jointly reflecting on our learnings from, and with, the children of what attention to olfaction brings to our practices of a researcher and practitioner (see Reinking Citation2021), we noted two main issues: first, the need for flexibility. Our action research approach and close university-kindergarten collaboration were guided by the premise that mutual knowledge exchange can lead to change in practice in terms of social interactions with the children in the classroom and the material resources they interact with. The flexible and iterative nature of an action research project (see McNiff and Whitehead Citation2009) allowed us to progressively adapt our plans to the Norwegian National Curriculum Plan, the demands of the children, other staff members, parents and gain their trust for participation.

Second, we grappled with the ethical dilemma connected to research-practice boundary. Researchers have the dual responsibility to not only increase knowledge in a context but to also carry that knowledge into the community where the knowledge is being generated and communicated (Silverman, Taylor, and Crawford Citation2008). This dual role poses distinct ethical questions, including unclear boundaries of prolonged relationships with the practitioners (Trondsen and Sandaunet Citation2009). In our case, this dilemma became clarified as the researcher and practitioner worked closely together and continue to do so after the initial study. In other projects, challenges remain, such as the normative content of some approaches and questions around ‘who is included in the community of inquiry and interpretation and what/who are the subjects of study’ (Eikeland Citation2006, 39). However, when well applied, action research can carry mutually beneficial consequences for children (see Li Citation2008). Reflecting on the present project, the university-teacher collaboration was fruitful in positively influencing the teacher’s practice, as well as the children’s experiences.

Our engagement in planning and re-planning, reflecting and challenging each other’s interpretations, and articulation of the problem was our attempt to critically engage with research. As for the researcher’s own critical stance, Natalia straddled the boundaries of synthesising a repertoire of ideas for addressing practical issues and staying loyal to the open-ended nature of qualitative inquiries. While teachers’ reports of children’s responses provided salient indicators of children’s experiences, Natalia contextualised them in light of the particular nature of the action inquiry. Here, the authors’ learnings needed to be discussed and clarified in light of the significant cross-cultural responses to odours (see for example Ferdenzi et al.'s Citation2011 study that showed different olfactory responses among Swiss, British, and Singaporean populations).

At the outset of the project, the teacher pointed out the lack of olfactory awareness in her classroom: there were no activities in the planning specifically focused on smell, nor was smell-related play part of the daily practice. Monika included more activities and resources focused on stimulating children’s sense of smell, and over the course of the project, she has become a reflective teacher-researcher in action (Phillips and Carr Citation2014). Being both teacher and co-researcher let Monika approach an educational problem and work with it in a new way. Before this project, her practice tended to be about quickly resolving problems as they emerged. During the action inquiry, Monika appreciated the cycle of a problem-solving process where she could observe, reflect and share the process of working on emerging problems, for example, in the context of introducing different scents to children and observing and noting children’s responses Through action inquiry, she began to appreciate the significance of reflecting on the children’s engagement and responses to different scents, allowing her to uncover valuable insights. Furthermore, the process of sharing her findings with colleagues and parents became an integral part of her action inquiry approach.

Reflecting further, Monika realized that re-planning and reflecting are key elements in a teacher-researcher journey. The process of taking on an identity as a teacher-researcher made her reflect on her goals and values as a practitioner. She developed new perception of her professional identity and felt that this new identity nurtured a sense of curiosity and renewed desire for knowledge creation. The ‘messy and aesthetically sensitive inquiry’ (Blomgren Citation2019) helped Monika understand the ways in which data insights can inform teachers’ daily routines and olfactory research in early childhood. As such, Monika experienced a professional change from being a teacher to becoming a researcher and the present action inquiry was the point of starting this shift. The participation in this project empowered her in many ways. She wrote the following in her log:

I found a great value in sharing my results, both with the researcher and other educators. This experience has shown me that there is no wrong or right way of sharing my results, the action inquiry has had a great potential for wonder and amazement. Reflecting on and discussing the lack of olfactory awareness in my classroom involved other educators in creating ambitious ways of solving the problem. Participating in action research let me learn about the world of people that I’m working with and to assist them to make better sense of their own world on their own terms.

Children participating in the research were enthusiastic about engaging in the creation of smellmaps, even though they have never tried it before. The teacher role helped me gain children’s trust and enabled me gathering the data, but also understand children’s’ attitudes and practice while introducing them to multi-sensory activities.

Personal reflexivity and joint knowledge creation shared with the researcher pushed me into seeing a great value in questioning and doubting, that I may have seen as disrupting the teaching/learning process before. Engaging in reflexivity has had its fundamental importance in including activities stimulating children’s sense of smell. Action research provided me with an opportunity to learn about research and to become more receptive to it. I experienced personal and professional growth which resulted in research becoming a part of my life and thus living beyond the project.

Study limitations and future recommendations

The timing of our study in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic may have morphed the olfactory profile of the kindergarten and led to an increased use of disinfectants, detergents and cleaning products. While these products are vital to effectively eliminate bacteria and viruses, they also carry a strong smell which masks other, fainter and more natural, smells in the environment. We also acknowledge that our perceptions of odours are relative, with subjective and cultural values attached to them. We therefore recommend that future research further explores the ‘sniffing atmospheres’ (Griffero Citation2022) that early childhood practitioners and children co-create in their local environments.

The research on olfaction in kindergartens is a nascent area of research and we were initially drawn to it because of the significant social justice potential it carries. Having seen the damaging effect of narrow understandings of language on children’s identity and the professional anxiety caused by constant scrutiny homogenising teachers’ literacy practices, we were keen to learn more about sensory learning and olfaction. Children’s bodies are being policed in schools and universities, but Norwegian kindergartens have a long tradition of free play and outdoor learning that invites the engagement of the entire body and all senses. A close focus on children’s olfactory experiences through the action-research lens generated concrete ways of engaging with and enacting critical theoretical frameworks in a new way. The tools that we developed and implemented in this process, such as a ‘smellmap’ created by children after a smellwalk, and an olfactory audit and its corresponding visual map from the kindergarten classroom, constitute important resources that could be refined in future action research and used to guide practice. We recommend that future research builds on our learnings and extends our observations with action inquiries in other contexts and with more direct involvement of the participating children.

We conclude that olfaction does not constrain but rather bakes the posthumanist, embodied and critical literacy theories into the lived experience of children’s learning and the classroom space. As such, olfaction can be viewed as an arena that amalgamates critical educational discourses and exemplifies a sensorially sensitive early childhood curriculum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvestad, M., L. Gjems, E. Myrvang, B. J. Storli, E. I. B. Tungland, L. K. Velde, Kjersti Lønning, and E. Bjørnestad. 2019. Kvalitet i barnehagen, 85. Rapporter fra Universitetet i Stavanger. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2630132.

- Arhar, J.A., M.L. Holly, and W.C. Kasten. 2001. Action Research for Teachers: Traveling the Yellow Brick Road. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Avison, D. E., F. Lau, M. D. Myers, and P. A. Nielsen. 1999. “Action Research.” Communications of the ACM 42 (1): 94–97. https://doi.org/10.1145/291469.291479.

- Badwan, K. 2021. Language in a Globalised World: Social Justice Perspectives on Mobility and Contact. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77087-7.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press.

- Blomgren, H. 2019. “Aesthetically Sensitive Pathways to Knowledge in and Through Action Research in Danish Kindergartens.” Educational Action Research 28 (5): 758–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2019.1696215.

- Cacioppe, R., and M. Edwards. 2005. “Seeking the Holy Grail of Organisational Development: A Synthesis of Integral Theory, Spiral Dynamics, Corporate Transformation and Action Inquiry.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 26 (2): 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510582536.

- Candau, J. 2004. “The Olfactory Experience: Constants and Cultural Variables.” Water Science and Technology 49 (9): 11–17. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2004.0522.

- Dahmani, L., R. M. Patel, Y. Yang, M. M. Chakravarty, L. K. Fellows, and V. D. Bohbot. 2018. “An Intrinsic Association Between Olfactory Identification and Spatial Memory in Humans.” Nature Communications 9 (1): 4162–4174. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06569-4.

- Danthiir, V., R. D. Roberts, G. Pallier, and L. Stankov. 2001. “What the Nose Knows: Olfaction and Cognitive Abilities.” Intelligence 29 (4): 337–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00061-7.

- Eikeland, O. 2006. “Condescending Ethics and Action Research: Extended Review Article.” Action Research 4 (1): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750306060541.

- Ferdenzi, C., S. Mustonen, H. Tuorila, and B. Schaal. 2008. “Children’s Awareness and Uses of Odor Cues in Everyday Life: A Finland–France Comparison.” Chemosensory Perception 1 (3): 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-008-9020-6.

- Ferdenzi, C., A. Schirmer, S. C. Roberts, S. Delplanque, C. Porcherot, I. Cayeux, and D. Grandjean. 2011. “Affective Dimensions of Odor Perception: A Comparison Between Swiss, British, and Singaporean Populations.” Emotion 11 (5): 1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022853.

- Gallagher, M., J. Prior, M. Needham, and R. Holmes. 2017. “Listening Differently: A Pedagogy for Expanded Listening.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (6): 1246–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3306.

- Ghaye, T., A. Melander-Wikman, M. Kisare, P. Chambers, U. Bergmark, C. Kostenius, and S. Lillyman. 2008. “Participatory and Appreciative Action and Reflection (PAAR) – Democratizing Reflective Practices.” Reflective Practice 9 (4): 361–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802475827.

- Gottfried, J. A. 2010. “Central Mechanisms of Odour Object Perception.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11 (9): 628–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2883.

- Griffero, T. 2022. “Sniffing Atmospheres. Observations on Olfactory Being-In-The-World.” In Olfaction: An Interdisciplinary Perspective from Philosophy to Life Sciences, edited by N. Di Stefano and M. T. Russo, 75–90. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75205-7_5.

- Hackett, A. 2021. More-Than-Human Literacies in Early Childhood. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350144750.

- Helskog, G. H. 2015. “Re-Imagining ‘Bildung zur Humanität’: How I Developed the Dialogos Approach to Practical Philosophy Through Action Inquiry Research.” Educational Action Research 23 (3): 416–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1013048.

- Herz, R. S. 2010. “The Emotional, Cognitive and Biological Basics of Olfaction.” Sensory Marketing: Research on the Sensuality of Products 87–107.

- Herz, R. S., J. Eliassen, S. Beland, and T. Souza. 2004. “Neuroimaging Evidence for the Emotional Potency of Odor-Evoked Memory.” Neuropsychologia 42 (3): 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.08.009.

- Herz, R. S., and M. Inzlicht. 2002. “Sex Differences in Response to Physical and Social Factors Involved in Human Mate Selection: The Importance of Smell for Women.” Evolution and Human Behavior 23 (5): 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00095-8.

- Hirsch, A. R. 2009. “What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life.” JAMA 301 (16): 1719–1720. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.515.

- Hopkins, D. 1985. A Teacher’s Guide to Classroom Research.Milton Keynes. New York: Open University Press.

- Johnson, K. 2014. “Creative Connecting: Early Childhood Nature Journaling Sparks Wonder and Develops Ecological Literacy.” The International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 2 (1): 126–139.

- Kucirkova, N. 2022. “The Explanatory Power of Sensory Reading for Early Childhood Research: The Role of Hidden Senses.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 14639491221116915. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491221116915.

- Kucirkova, N., and M. Kamola. 2022. “Children’s Stories and Multisensory Engagement: Insights from a Cultural Probes Study.” International Journal of Educational Research 114:101995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101995.

- Li, Y. L. 2008. “Teachers in Action Research: Assumptions and Potentials.” Educational Action Research 16 (2): 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802011908.

- Majid, A. 2015. “Cultural Factors Shape Olfactory Language.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 19 (11): 629–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.06.009.

- Majid, A. 2021. “Human Olfaction at the Intersection of Language, Culture, and Biology.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25 (2): 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.11.005.

- Maric, Y., and M. Jacquot. 2013. “Contribution to Understanding Odour–Colour Associations.” Food Quality and Preference 27 (2): 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.05.001.

- McKim, A., and N. Wright. 2012. “Reflections on a Collaborative Adult Literacy and Numeracy Action Enquiry.” Educational Action Research 20 (3): 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2012.697393.

- McLaughlin, C. 2020. “Editorial.” Educational Action Research 28 (5): 719–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2020.1840868.

- McNiff, J. 2013. Action Research: Principles and Practice. London: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112755.

- McNiff, J. 2016. Writing Up Your Action Research Project. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315693620.

- McNiff, J., and J. Whitehead. 2009. All You Need to Know About Action Research. London: Sage.

- Merelau-Ponty, M. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Merelau-Ponty, M. 2012. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203720714.

- Mills, K. A., L. Unsworth, and L. Scholes. 2022. Literacy for Digital Futures: Mind, Body, Text. New York: Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003137368.

- Nordström, A., K. Kumpulainen, and A. Rajala. 2021. “Unfolding Joy in Young Children’s Literacy Practices in a Finnish Early Years Classroom.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 14687984211038662:146879842110386. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687984211038662.

- Nunes, C., and N. D. Oliveira. 2022. “Developing Communication and Inclusive Literacy Skills Among Children with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities: The Role of Multi-Sensory Storytelling.” In Modern Reading Practices and Collaboration Between Schools, Family, and Community, 125–154. IGI Global.

- Olofsson, J. K., and S. Nordin. 2004. “Gender Differences in Chemosensory Perception and Event-Related Potentials.” Chemical Senses 29 (7): 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjh066.

- Osgood, J., and S. Mohandas. 2022. “Grappling with the Miseducation of Montessori: A Feminist Posthuman Rereading of ‘Child’ in Early Childhood Contexts.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 23 (3): 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491221117222.

- Percy‐Smith, B., and C. Carney. 2011. “Using Art Installations as Action Research to Engage Children and Communities in Evaluating and Redesigning City Centre Spaces.” Educational Action Research 19 (1): 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2011.547406.

- Phillips, D.K., and K. Carr. 2014. Becoming a Teacher Through Action Research: Process, Context, and Self-Study. Third ed. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315867496.

- Ponte, P., and Editors with. 2006. “Quality of Action Research: ‘What is it’, ‘What is It for’ and ‘What next’?” Educational Action Research 14 (4): 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790601000607.

- Pool, S., J. Rowsell, and Y. Sun. 2023. “Towards Literacies of Immanence: Getting Closer to Sensory Multimodal Perspectives on Research.” Multimodality & Society 3 (2): 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/26349795231158741.

- Proust, M. 2013. Swann’s Way: In Search of Lost Time. Vol. 1. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rege, M., I. F. Solli, I. Størksen, and M. Votruba. 2018. “Variation in Center Quality in a Universal Publicly Subsidized and Regulated Childcare System.” Labour Economics 55:230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2018.10.003.

- Reinking, D. 2021. Design-Based Research in Education: Theory and Applications. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Ritchie, J. 2016. “Qualit Ies for Early Childhood Care and Education in an Age of Increasing Superdiversity and Decreasing Biodiversity.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 17 (1): 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949115627905.

- Rodriguez Leon, L. 2021. “Sensing and Configuring the World with Text: Bringing Neo-Vygotskian Thinking into Dialogue with More-Than-Human Literacies in Early Childhood.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 44 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2021.2008321.

- Rönnerman, K., E. M. Furu, and P. Salo. 2008. Nurturing Praxis: Action Research in Partnerships Between School and University in a Nordic Light. Rotterdam, Netherlands: BRILL.

- Rose, L., M. Vaughn, and L. Taylor. 2015. “Reshaping Literacy in a High Poverty Early Childhood Classroom: One Teacher’s Action Research Project.” Journal of Research in Education 25 (1): 72–84.

- Schön, D. A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. London/New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Sefton-Green, J., J. Marsh, O. Erstad, and R. Flewitt 2016. Establishing a Research Agenda for the Digital Literacy Practices of Young Children: A White Paper for COST Action IS1410. http://digilitey.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/DigiLitEYWP.pdf.

- Sharp, C., and R. Balogh. 2021. “Becoming Participatory: Some Contributions to Action Research in the UK.” In The SAGE Handbook of Participatory Research and Inquiry, edited by Danny Burns, Jo Howard, and M. Ospina Sonia, 154–169. London: SAGE.

- Silverman, R. M., H. L. Taylor Jr, and C. Crawford. 2008. “The Role of Citizen Participation and Action Research Principles in Main Street Revitalization: An Analysis of a Local Planning Project.” Action Research 6 (1): 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750307083725.

- Spence, C. 2020. “Olfactory-Colour Crossmodal Correspondences in Art, Science, and Design.” Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 5 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-020-00246-1.

- Stevenson, R. J. 2010. “An Initial Evaluation of the Functions of Human Olfaction.” Chemical Senses 35 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjp083.

- Thomas, L. 1990. A Long Line of Cells Collected Essays. New York: Book of the Month Club.

- Thyssen, G., and I. Grosvenor. 2019. “Learning to Make Sense: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Sensory Education and Embodied Enculturation.” The Senses & Society 14 (2): 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17458927.2019.1621487.

- Torbert, B. 2004. Action Inquiry: The Secret of Timely and Transforming Leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Torbert, W. R. 2006. “The Practice of Action Inquiry.” In Handbook of Action Research: Concise Paperback Edition, edited by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, 207–218 . London: SAGE.

- Torbert, W. R., and S. S. Taylor. 2008. “Action Inquiry: Interweaving Multiple Qualities of Attention for Timely Action.” In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, edited by Bradbury-Huang, Hilary and Reason Peter, 239–251. London: SAGE.

- Trondsen, M., and A. G. Sandaunet. 2009. “The Dual Role of the Action Researcher.” Evaluation and Program Planning 32 (1): 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.09.005.

- Turley, L. W., and R. E. Milliman. 2000. “Atmospheric Effects on Shopping Behavior: A Review of the Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Business Research 49 (2): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00010-7.

- Udir 2017 Rammeplan for barnehagen, Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagens innhold og oppgaver, Norwegian Kindergarten Curriculum Plan, Available online from: https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/rammeplan-for-barnehagen/.

- Vosshal, L. 2019. Scents and Sensibilities: The Invisible Language of Smell, World Science Festival, New York (panel presentation).

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. 2018. “An Educational Framework for Participatory Action Learning and Action Research (PALAR).” Educational Action Research 26 (4): 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1464939.