?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Recently, evidence has been increasing that individuals who are able to narrate coherently about their autobiographical memories, receive more positive social feedback, have higher-quality social relationships and are overall less likely to suffer from internalising psychopathology, like depression and anxiety. However, the relation between narrative coherence and social anxiety, in particular, has not been topic of research until now. This is remarkable, since the concern about negative evaluations by others in social situations is at the core of social anxiety. In the present experimental study (N = 68), we investigated in a two-by-two design how trait and state social anxiety are related to narrative coherence, as well as possible underlying mechanisms. In our study, neither trait nor state social anxiety, nor their interaction had the expected detrimental effect on narrative coherence. However, trait differences in the proposed mechanisms of social anxiety were in line with the literature. Results showed that trait social anxiety and thematic narrative coherence were indirectly negatively related, via the intervening effects of an increased internal focus on anxiety cues, an excessive external focus on negative social evaluation, larger working memory load, more rumination and more depressive symptoms. Limitations and recommendations for future research are addressed.

Anxiety disorders are by large the most prevalent amongst psychiatric conditions, affecting a staggering 28.8% of people over the course of their lives (Kessler et al., Citation2005). Social anxiety accounts for almost half of that number, reaching as much as 12.1% lifetime prevalence (Kessler et al., Citation2005). The concern about negative evaluations or possible scrutiny by others in social or performance situations, in combination with a heightened internal focus on the anxious self, as well as on thoughts, memories and sensations related to anxiety are thought to be key elements to the maintenance of social anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Clark & McManus, Citation2002; Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000; Morgan, Citation2010; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997). In addition, socially anxious individuals experience severe difficulties in the development and maintenance of relationships, causing significant impairments in their psychological well-being, for example, due to feelings of loneliness or social isolation (NIMH, Citation2014).

One very frequently used manner to develop and maintain social relationships is through reminiscing about past personally experienced events, or in other words through socially sharing our autobiographical memories (Rimé et al., Citation1998). It is actually our autobiographical memory which enables the recollection of personal experiences, and their integration into meaningful narratives (Fivush, Citation2011; Tulving, Citation2002). Since the social sharing of memories fosters our sense of belonging to others, it is not surprising that one of the three main functionsFootnote1 of autobiographical memory concerns social bonding (Bluck, Citation2003; Bluck et al., Citation2005; Bluck & Alea, Citation2009, Citation2011; Fivush et al., Citation2003; Pasupathi et al., Citation2002). The social bonding function of autobiographical memory entails that we retrieve and share memories in order to connect with other people, as this sense of belongingness enhances our psychological well-being (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Ozbay et al., Citation2007). The social function of autobiographical memory has been deemed fundamental, not only due to its ubiquity (Rimé et al., Citation1998), or its evolutionary adaptive value (Harandi et al., Citation2017), but also because of memory’s inherently social developmental origins (Fivush, Citation2011; Fivush et al., Citation2006; Nelson & Fivush, Citation2004), and the lifelong dynamic interaction between memory narration and the social context (Fivush et al., Citation2011; Nelson & Fivush, Citation2004; Pasupathi, Citation2001).

As a matter of fact, the successful fulfilment of the social function of autobiographical memory is dependent on precise phenomenological characteristics of the memory (Alea & Bluck, Citation2003; Sutin & Robins, Citation2007). Certain characteristics of remembering seem to be of particular importance in the fulfilment of memory’s functions and hence also affect our psychological well-being (Barry et al., Citation2019; Beike et al., Citation2016; Horselenberg et al., Citation2004; Palombo et al., Citation2018; Raes et al., Citation2006; Williams et al., Citation2007). One of these characteristics is memory coherence, also referred to in its operationalised form as narrative coherence, which is the ability to construct a narrative of past personal events in a manner that is understandable for an outside listener, with regards to context, chronology and theme (Reese et al., Citation2011). This means that for the narrative to be considered as coherent, the events need to be situated in time and place, the events need to follow a logical and chronological order, and there needs to be elaboration, not only factually but also emotionally, around a certain central theme, including a high-point and a resolution. Several researchers have suggested that memory coherence can be seen as a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for high-quality narratives (Adler et al., Citation2018; Labov, Citation1972; McAdams, Citation2006). Particularly, in a social context, stories must show a minimum level of coherence to be understandable for a listener, in order to be a suitable topic of conversation (Pasupathi et al., Citation2002), to teach or inform other people (McLean & Lilgendahl, Citation2008), or to evoke empathy from others (Alea et al., Citation2013; Bluck et al., Citation2013).

In recent years, evidence has been increasing that individuals who are more narratively coherent, fare better psychologically and are less likely to suffer from internalising symptoms of psychopathology, like depression and anxiety (Adler et al., Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2012; McLean et al., Citation2010; Mitchell et al., Citation2020; Reese et al., Citation2011, Citation2017; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020a; Vanderveren et al., Citation2019). In addition, narrative coherence has also been shown to be positively related to having high-quality social relationships and to experiencing less negative social interactions (Burnell et al., Citation2010; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020a; Waters & Fivush, Citation2015). In experimental work, sharing memories in an incoherent manner, has shown to evoke more negative social evaluations from listeners, than doing so in a coherent manner (Vanaken et al., Citation2020; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020b). Given that narrative coherence develops in early social interactions, and particularly through elaborative mother–child reminiscing, it is not surprising that a poorly developed ability to share autobiographical memories with others in a coherent manner, has an enduring effect on the quality of social relationships throughout life (Fivush, Citation2011; Fivush et al., Citation2006; Nelson & Fivush, Citation2004). Interestingly, specifically this fear of negative evaluation in social contexts is a key element in social anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

However, although narrative coherence has shown to be negatively related to psychopathology and positively to social bonding, to our knowledge, no studies have been done on coherence in socially anxious individuals in particular. It would nonetheless be, particularly in socially anxious individuals, very useful to address narrative coherence, in a search for mechanisms that help explain their experienced difficulties in social interaction. Taking into account the above, it could be possible that incoherence plays a disturbing role in the memory sharing process of individuals with social anxiety, making it difficult to connect with others or to establish enduring social relationships. Accordingly, to address this gap, our first research question concerns the investigation of narrative coherence in socially anxious individuals, compared to healthy controls. Using a quasi-experimental design, we hypothesise that people who score high on a social anxiety disorder questionnaire, from here on defined as high trait social anxiety, are less coherent when talking about their personal past experiences, in comparison to low socially anxious individuals.

As stated before, our autobiographical memory does not only have a social function, but also a self-function,1 which serves to create a sense of continuity and identity (McAdams, Citation2001). Without memories of our past, we would not be able to know who we are or what we stand for. Moreover, this social function and self-function are not independent, as the way we narrate about our past impacts our self-perspective and vice versa (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000; Nelson, Citation2003). In this context, Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (Citation2000) developed the Self-Memory System (SMS), explaining the relationship between the self and the autobiographical memory. They argue that how we think and talk about ourselves is dependent on our active working self. Our working self, which can be conceptualised as the current image or view we have about ourselves, modulates our behaviour, cognition, and affect. This implicates that the way we perceive ourselves at any given time influences also our remembering, thus the content and phenomenological properties of our memories, to be consistent with those activated identity goals (Conway, Citation2005; Conway et al., Citation2004; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000). Previous research of Krans et al. (Citation2014) has already evidenced the importance of the SMS for social anxiety, supporting the idea that the fearful self in social contexts is a key element of the problem (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Krans et al. (Citation2014) showed, in line with the SMS, that participants high in social anxiety recalled more negative memories and more memories related to social anxiety than the low socially anxious group. Their findings are also consistent with research on self-focus priming in social anxiety, which is suggested to evoke processing deficits in terms of quality, accessibility, and content of the memories (for a review, see Morgan, Citation2010).

In our study, the SMS would predict that socially anxious individuals who have a socially anxious working self, that is an active view of themselves as being anxious in a social situation, and are thus more state socially anxious, would be more likely to behave accordingly. This means that their state social anxiety would bring about memory processing deficits, affecting their narration in a detrimental way (Morgan, Citation2010). Under high state social anxiety, they would narrate more incoherently about their memories, in comparison to controls, who would be unaffected by a social evaluative priming (Dickson, Citation2004). Our second research question consequently concerns the effect of increased state social anxiety, which we will establish via social evaluative priming, on memory coherence. Using a two by two design, dividing both the high and the low trait group into a high and low state group, we hypothesise that individuals who are brought in a momentary state of social anxiety will narrate less coherently, specifically for the group of individuals with an existing trait vulnerability for social anxiety. In other words, we predict an interaction effect of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence.

Both of previous hypotheses, concerning the detrimental effect of trait and state anxiety on narrative coherence, have been descriptive in nature; they predict the occurrence of phenomena but do not yet explain them. Consequently, our third research question concerns the investigation of working mechanisms of the possible effect of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence, which are based on current cognitive models of social anxiety. There is quite extensive evidence that social anxiety is marked by particular attentional and memory biases (Morgan, Citation2010). The main attentional biases that have been found to be characteristic of social anxiety are the dual combination of an excessive external focus on possible negative social evaluation or threat (e.g., negative facial expressions), as well as an enlarged internal focus on cues, sensations, or thoughts related to anxiety (e.g., heightened heart rate, imagining saying something wrong) (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Rapee & Heimberg, Citation1997). In addition, the attentional biases can set into motion memory recall biases, enabling retrieval of past negative social experiences (e.g., being laughed at as a kid for giving a “bad” presentation in class), and trigger ruminative processes (e.g., “I am a social failure”, “People think I am stupid”) (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Edwards et al., Citation2003; Field & Morgan, Citation2004). Especially in social situations, socially anxious individuals are found to excessively process social information both before (e.g., everyone is going to look at me at the party) and after the social event (e.g., everyone was looking at me and judging me when I accidentally dropped my fork) (Abbott & Rapee, Citation2004; Field & Morgan, Citation2004; Mellings & Alden, Citation2000). The tendency to overthink and ruminate about past social events is sometimes also referred to as post-mortem or post-event processing (PEP) (Brozovich & Heimberg, Citation2008; Clark & Wells, Citation1995). Although, there have been suggested differences between rumination and PEP (e.g., PEP: visual imagery of the self as a social failure might be more present), they are thought to be somewhat similar and generally used interchangeably throughout the literature on social anxiety (for reviews see: Brozovich & Heimberg, Citation2008; Morgan, Citation2010). For consistency purposes, we prefer to adhere to the term rumination in this text. Since research suggests that ruminative processes can affect autobiographical memory recall (Field & Morgan, Citation2004), it is important to investigate these as possible mechanisms that might explain relations between social anxiety and narrative coherence. In addition, since rumination is thought of as a process integral to depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, Citation1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Citation2008), it is to no surprise that socially anxious people are often comorbidly depressed (Kessler et al., Citation1999; Ohayon & Schatzberg, Citation2010). The described attentional and memory biases are thought to take up working memory resources, leaving less free executive capacities for the processing of the actual events (Klein & Boals, Citation2001), thereby keeping the negative biases intact.

Summarised, Clark and Wells’s (Citation1995) model of social anxiety theorises that when socially anxious individuals enter feared situations, they shift their attention to a detailed monitoring of themselves as a social object (internal focus), whilst simultaneously steering their attention towards possible signs of threat/negative social evaluation (external focus), which triggers retrieval of past negative social experiences (rumination). All of this interferes with efficient processing of the actual social situation (working memory load), leaving the anxious individual trapped in a closed circle in which the idea that others are judgmental and critical of them prevails. The fact that this information is self-generated and -maintained, keeps social anxiety intact.

Bridging these findings to memory coherence, some of the described mechanisms that are suggested to play a role in social anxiety have also been investigated in relation to memory coherence. For example, research has pointed out an important negative association between cognitive load and narrative coherence, indicating that free executive resources might be crucial in order to construct coherent narratives (Boals et al., Citation2011; Frattaroli, Citation2006; Klein & Boals, Citation2001). Furthermore, studies indicate that depression and rumination negatively relate to memory coherence (Buxton, Citation2016; Mitchell et al., Citation2020; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020a; Vanderveren et al., Citation2019), and that rumination can play a mediating role in the association between narrative coherence and psychopathology in younger adolescents (Habermas & Reese, Citation2015). A recent study of Vanderveren et al. (Citation2020) confirms that the relation between memory coherence and depression is at least partially explained by rumination. However, there is no research specifically on the role of depression and rumination in relation to memory coherence in socially anxious individuals. Neither is there evidence for the increased internal and external focus or working memory load affecting narrative coherence for socially anxious individuals in particular. Therefore, this third research question, which concerns the working mechanisms of possible effects of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence, is exploratory in nature.

Taking the above together, we hypothesise that socially anxious individuals, especially when brought in a heightened state of social anxiety, will feel more externally socially evaluated, have a higher focus on internal cues of anxiety, have increased ruminative tendencies and limited executive capacities, which could hinder their ability to come to a coherent account of their turning point memory, in comparison to less socially anxious people.

Summarised, in a two-by-two design, we will examine the main and interaction effects of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence, as well as underlying mechanisms of the possible effects. Two groups of participants will be invited to the lab, differing significantly in terms of trait social anxiety. In the beginning, all participants will fill out pre-measurements of the variables of interest (external focus on negative social evaluation, internal focus on anxiety cues, rumination, working memory load, arousal). Then, the experimental manipulation will take place, in which the state social anxiety of half of each trait group will be heightened by a social evaluative priming, whereas the state social anxiety of the other half of each trait group will be kept neutral. Following, all participants will be instructed to talk about a turning point memory. We expect here that participants high in trait social anxiety will narrate less coherently than those low in trait social anxiety, and furthermore, that specifically for those high in trait social anxiety whose state social anxiety is heightened further, the narration will be less coherent than for those whose state social anxiety is not heightened. In other words, we expect a main effect of trait and an interaction effect of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence. Afterwards, all participants will fill out the same questionnaires on our variables of interest again as a post-measurement. Changes from pre- to post-measurement, as well as relations between the described variables with one another and with coherence could help us explore mechanisms underlying an effect of social anxiety on memory coherence. Insight into these mechanisms of psychopathology is essential in order to move beyond the mere description of phenomena, and rather understand and explain them, with the eye on developing possible clinical interventions in the future. We expect increases from pre- to post-measurement on these variables, specifically for the group whose state social anxiety is increased by the experimental manipulation. The main research questions, key variables, conditions and analyses were pre-registered on AsPredicted http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=gh23ra.

Materials and methods

Participants

Based on the scores (25% highest and the 25% lowest) of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS, Liebowitz, Citation1987) in a previous questionnaire study (N = 357) three months prior, participants were invited by email to sign up for this study. A total of 73 young adults took part, 68 of whom constituted the final sample. We excluded 5 participants, because they did not adhere to the inclusion criterium of having Dutch as their mother tongue, or because of technical problems with the audio recordings. The final sample consisted of 68 young adults between the ages of 17 and 20, M = 18.31, SD = .68, of whom 58 (85.3%) were female and 10 (14.7%) were male. Based on the selection, the sample included a group with low trait social anxiety (nLow = 36) and a group with high trait social anxiety (nHigh = 32), which significantly differed in their reported symptoms of anxiety and avoidance of social situations on the LSAS, MLow = 20.31, SDLow = 8.67, MHigh = 77.28, SDHigh = 12.51, t(66) = −22.02, p < .01. The sample size was based on a similar study from Krans et al. (Citation2014). A post-hoc power analysis was executed using G*Power, based on the effect size of the ANOVA results (cf. infra), and showed that our sample was sufficiently large, reaching a very good power of .95. All participants gave informed consent before the start of the study and received either partial course credit or remuneration (€4) for their participation. The study was approved by the KU Leuven Social and Societal Ethics Committee (G - 2018 10 1376).

Material and measures

Turning point narrative task

Waters and Fivush (Citation2015) found that the relation between memory coherence and positive social relationships, was moderated by the extent to which memories were relevant to the self. Therefore, they have suggested that particularly those memories that are relevant for identity that are likely to serve memories’ functions of building relationships. Accordingly, in this study, we chose to work with turning point memories, which are seen as an identity-defining (e.g., McLean & Pratt, Citation2006) and mark a meaningful transformation within an individual’s conceptualisation of his or her identity (McLean et al., Citation2017).

Narration. Participants were asked to talk out loud about a turning point memory in their life following these instructions:

I would like you to think back over your life and identify an event that has changed your life or the kind of person you are. It could be something from any area of your life – your relationships with other people, your work and school, your outside interests, and so forth. Please identify a particular episode in your life story that you now see as a turning point in what your life is like or what you are like as a person. Please describe what happened, when it happened, who was involved, what you were thinking and feeling, why this experience is significant, and how it changed your life or you as a person.

Coding. The memories were audio recorded, transcribed and coded manually according to the Narrative Coherence Coding Scheme (NaCCS; Reese et al., Citation2011). Using this coding scheme, each narrative was assigned a total score from 0 to 9, consisting of the sum of the scores on the 3 dimensions that the scheme entails, namely context (0–3), chronology (0–3), and theme (0–3). Total narrative coherence (0–9) was calculated by summing the scores for the individual dimensions.

To make sure the data were coded reliably, good inter-rater reliability was established on 10% of the data, as was evident from high intraclass correlations (ICC) for all dimensions, ICCcontext = .94; ICCchronology = .88; ICCtheme = .90. Afterwards, all other spoken data were coded by the first author.

Experimental manipulation

For both the low and high anxious group, a randomised half of the participants’ social anxiety was temporarily heightened (experimental group), whereas it was kept neutral for the other half (control group). The experimental manipulation consisted of a combination of receiving specific instructions as well as the presence vs absence of an evaluative listener.

The experimental group received the instructions that they would have to talk out loud in front of the researcher and into the camera (which was placed in front of them) about a turning point memory. They were told that the researcher would take notes and that the camera would video and audio record their social behaviour, which would be analysed in a further stage of the study by the team of social psychologists and the professor at the head of the lab. During their narration, the researcher stood right next to participant in the cubicle. The researcher was a 23-year old female, who was, before participation to the experiment, unfamiliar to the participant. We chose to work with a listener/researcher that was similar in characteristics to the speaker/participant (young, white, female), in order to increase the ecological validity of the experiment (similar to friends, peers) (Alea & Bluck, Citation2003). Furthermore, the listener/researcher was attentive to the story of the speaker (which is important for memory narration, particularly in emergent adulthood, e.g., Bavelas et al., Citation2000; Fioretti et al., Citation2017; Pascuzzi et al., Citation2017; Pasupathi, Citation2001). However, she had an evaluative attitude (taking notes on a paper, looking strict, etc.). The researcher did not interrupt the participants whilst narrating, neither did she reply to any possible questions the participants had. In short, there was mere presence of a strict, evaluative listener in order to increase social evaluative feelings in the participants in the experimental condition.

The control group received the instructions that they would have to talk out loud about a turning point memory, but that they would be left alone in the room by themselves, to calmly receive the opportunity to think about what they are going to talk about and then do so. So, during narration, participants were left alone in the cubicle with no researcher present and narrated their memory into a microphone.

Note that, in both groups, the turning point memory was only audio recorded, to later be transcribed and coded for coherence. No video recordings were taken of any of the participants’ behaviour as this was only told as part of the experimental manipulation.

Liebowitz social anxiety questionnaire

This questionnaire measures, by means of 24 items, social anxiety and avoidance of social (11 items) or performance (13 items) situations (LSAS: Liebowitz, Citation1987, Dutch Translation: Van Vliet, Citation1999). It provides an overall score with a maximum of 144, with scores under 30 pointing out that Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is very unlikely, and scores above 60 indicating a higher probability of SAD. For readability purposes, we define high scores on the LSAS as high trait social anxiety. Heimberg et al. (Citation1999) found excellent internal consistency of the LSAS and significant correlations with other commonly used measures of social anxiety like, pointing to good convergent validity.

Depression anxiety and stress scales

We used the depression items of the DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995; Dutch translation: de Beurs et al., Citation2001), to check for overlap between social anxiety and depression and its possible impact on our results. The DASS-21 has proven to be internally consistent (.85 ≤ Cronbach’s α ≤ .91), test-retest reliable (.74 ≤ r ≤ .85) and valid in a Dutch sample of first year university students (N = 289), which is comparable to our sample (de Beurs et al., Citation2001).

Mechanisms

We administered questionnaires to check if our state social anxiety manipulation worked and via which processes the manipulation might have had an effect on memory coherence. We measured the external focus on social evaluation, the internal focus on cues of anxiety, rumination, depression, working memory load and arousal. The items for each questionnaire are included in Appendix B (see supplemental material).

Procedure

Participants were invited to the lab to participate in a study that was described as a memory retrieval task combined with some behavioural and emotional questionnaires. Participants took place behind the computer, and after signing consent to participate in the study, they started the experiment. First, they filled out the depression items of the DASS-21 on the computer. Subsequently, participants completed questions concerning their current focus on negative social evaluation, focus on internal cues of anxiety, working memory load, state rumination, and arousal as a pre-measurement. Then, the experimental manipulation took place, which aimed at changing the state level of social anxiety. After the experimental manipulation took place, participants were asked to talk about their turning point memory either under high or low social evaluation. The researcher read the instructions out loud, and then either stayed in the cubicle with the participant (experimental group) or left him/her alone (control group) whilst the instructions were still presented on the screen as well, to ensure everything was understood properly. The instructions also remained on the screen whilst the participant was talking about his/her memory. Afterwards, all participants filled out the same questionnaires as they did in the beginning, regarding their momentary feelings of social evaluation, focus on internal cues, working memory load, rumination, and arousal as a post-measurement. Upon finishing the experiment, participants were given contact details of help instances and thanked for their participation.

Results

Data analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. First, descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated. Then, we ran a multivariate ANOVA-analysis with trait and state social anxiety as the fixed factors, and memory coherence and its dimensions as the dependent variables, to investigate our first (trait) and second (state) research question. Afterwards, we ran repeated-measures ANOVA-analyses, to investigate the main effects of trait social anxiety, the main effects of state social anxiety and the interaction effects of trait and state (between-subject variables), on the earlier introduced variables of interest (external focus, internal focus, rumination, working memory, arousal). We did this both at pre-measurement, at post-measurement, as well as with regards to the development over time from pre- to post-measurement (within-subject variables), as a check for our manipulation, as well as to investigate underlying mechanisms, in line with our third research question. An α-level of .05 was set for all analyses. For the comprehensibility of the results, we focused on reporting significant effects, or the absence of significance where otherwise hypothesised. Analyses were pre-registered on Aspredicted (http://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=gh23ra) and the raw data underlying the results are openly available at the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WF5HN).

Effects of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence

Descriptive statistics for memory coherence are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of total memory coherence across groups.

Investigating the effects of the two independent variables (trait and state social anxiety) in our 2-by-2 design shows that both did not impact the main dependent variable (memory coherence). Neither trait social anxiety, F (1, 67) = .01, p = .91, = .00, nor the state social anxiety manipulation, F (1, 67) = .49, p = .49,

= .01, had an effect on the total narrative coherence. As is shown in , neither of the individual dimensions of memory coherence was impacted by trait, state or an interaction of trait and state social anxiety.

Table 2. Tests of between-subjects effects (MANOVA) of trait and state social anxiety on memory coherence.

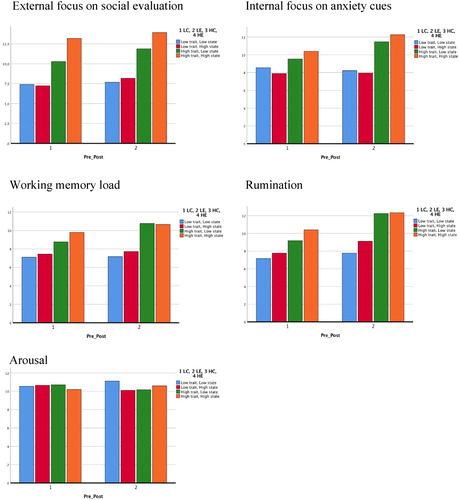

Effects on proposed mechanisms of social anxiety ()

External focus on negative social evaluation

Participants in the low trait social anxiety (SA) group reported significantly less social evaluation than participants in the high trait SA group, both at the beginning of experiment, F (1, 67) = 23.95, p < .001,

= .27, as well as at the end of it, F (1, 67) = 31.67, p < .001,

= .33. There was a significant difference in reported social evaluation from pre- to post-manipulation across all groups, F (1, 67) = 7.73, p = .007,

= .11. This indicated that the procedure in general increased feelings of social evaluation, which was independent of the group (trait), F (1, 67) = .74, p = .38,

= .01, and the condition (state), F (1, 67) = .02, p = .88,

= .00, and of the interaction of the trait and state SA, F (1, 67) = 1.43, p = .24,

= .02.

Internal focus on cues of anxiety

The internal focus on cues of anxiety was also higher in people with high trait SA, both at pre-measurement, F (1, 67) = 3.99, p = .05,

= .06, and post-measurement, F (1, 67) = 23.52, p < .001,

= .27. Similar to the previously found results, there was a visible increase during the course of the experiment for all groups, F (1, 67) = 9.87, p = .003,

= .13. However, here was a significant effect of trait SA in this increase, being that people with high trait SA showed a sharper increase in their focus on internal cues of anxiety from the beginning to the end of the experiment, F (1, 67) = 13.22, p = .001,

= .17.

Rumination

Similar to the above, both at the beginning, F (1, 67) = 6.52, p = .013,

= .09, and at the end, F (1, 67) = 21.58, p < .001,

= .25, people with high trait SA ruminated more than people with low trait SA. From pre- to post-manipulation, there was a general increase in rumination for all four groups, F (1, 67) = 28.04, p < .001,

= .31. Again, this increase was influenced by trait SA, as people high in trait SA showed a larger increase in rumination over the course of the experiment, in comparison to those low in trait SA, F (1, 67) = 5.41, p = .02,

= .08.

Working memory load

The working memory load was also higher in people with high trait SA, both at the start, F (1, 67) = 4.53, p = .04,

= .07, as well as at the end, F (1, 67) = 11.37, p < .001,

= .15, of the experiment. Comparing start and end of the experiment, an increase in working memory load was observed across all groups, F (1, 67) = 8.70, p = .004,

= .12. Again, there was an interaction effect of trait SA during this increase, F (1, 67) = 5.45, p = .023,

= .08, indicating that those with high trait SA reported a bigger increase in their working memory load from pre- to post-manipulation, in comparison to those with low trait SA.

Arousal

Comparing the groups and conditions in terms of the arousal they subjectively felt pre-, post-, and comparing pre- to post-manipulation, it is evident that there were no effects of trait, F (1, 67) = .03, p = .86,

= .001, or state social anxiety, F (1, 67) = .06, p = .80,

= .001. In other words, all participants seemed very aroused during the whole of the experiment. We will elaborate on this in the discussion.

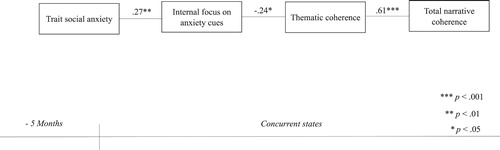

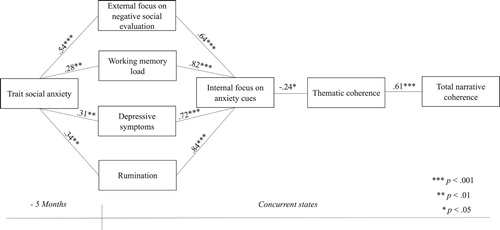

Indirect effects

Since we did find trait differences in the proposed mechanisms that were in line with the literature (Clark & Wells, Citation1995) (i.e., high socially anxious individuals had, at the measurement pre-manipulation, a higher focus on external social evaluation and on internal cues of anxiety, a higher working memory load, and engaged more in ruminative processes), and since available research on social anxiety and narrative coherence is very sparse, we decided to do an exploratory (post-hoc, not included in the pre-registration) investigation of possible indirect effects of the proposed mechanisms on narrative coherence (Holmbeck, Citation1997). In other words, we aimed to investigate relations between the broad range of differences in trait social anxiety and differences in concepts that are theoretically related in the literature (cognitive models of social anxiety: Clark & Wells, Citation1995), since empirical evidence is very limited in this regard as of yet. We calculated the Spearman’s correlations between trait social anxiety (the scores on the LSAS), the pre-measures of the proposed mechanisms (before the manipulation took place, unaffected by the manipulation of state social anxiety) and memory coherence to investigate possible indirect effects via intervening variables (Holmbeck, Citation1997; MacKinnon et al., Citation2002). Spearman’s correlations were chosen instead of Pearson’s correlations, since we had pre-selected people for being high or low in trait social anxiety (i.e., violation of assumption of normality due to non-continuous distribution). Results showed that social anxiety and memory incoherence were associated via indirect effect patterns. In and the effects are demonstrated stepwise, from a simplified and elegant to a more complex model including more intervening variables. Trait social anxiety as measured by the LSAS (ie. social anxiety disorder), was significantly related to an excessive internal focus on anxiety cues, which in turn related to thematic and total memory coherence. In the more complex model, the indirect effects of an excessive external focus on social evaluation, working memory load, depressive symptoms and rumination in the relation between trait social anxiety and an excessive internal focus were demonstrated. Note that these findings are preliminary and would benefit from further hypothesis-driven investigations.

Discussion

This was the first study to address the relations between social anxiety and narrative coherence. We aimed to investigate the effect of trait and state social anxiety on coherence as well as theorised working mechanisms in respectively a first, second and third research question.

Results were not in line with our first hypothesis, as individuals scoring high on trait social anxiety, did not show an overall lower level of narrative coherence, in comparison to low socially anxious individuals. With regards to our second question, our manipulation aimed at increasing state social anxiety levels did not have the intended effect on memory coherence, as memory coherence was not lower for those high in state social anxiety, neither was there an interaction effect between state and trait social anxiety on memory coherence.

Inspection of the suggested mechanisms with regards to our third research question, taught us that the manipulation did likely not have the intended effect of increasing state social anxiety. The measures were affected by trait social anxiety both pre- and post-manipulation, but not by state social anxiety. Individuals scoring high on trait social anxiety had a higher external focus on negative social evaluation, a higher internal focus on cues of anxiety, a larger working memory load, and ruminated more both before and after the manipulation took place, in comparison to low socially anxious individuals. Trait social anxiety also interacted with the increase in reported internal focus on cues of anxiety, working memory load and rumination, from pre to post-measurement. Highly socially anxious individuals showed a sharper increase in the aforementioned variables. These observed differences between trait groups are in line with the literature (Clark & Wells, Citation1995). Results were however remarkable for one of the suggested mechanisms, being arousal. Looking at the arousal results, all participants were very aroused, and likely very anxious, during the whole experiment, independent of trait and state social anxiety. High arousal was observed both pre- and post-manipulation, possibly reaching a ceiling effect in state social anxiety before the manipulation took place, and thereby leaving our manipulation ineffective. The mere process of filling out pre-measurements, which concerned questions that related to socially anxious feelings, or even the act of participating in an experimental study, could have already worked as a manipulation for all participants, increasing their state social anxiety regardless of condition.

However, even though the manipulation was ineffective, due to the quasi-experimental nature of our design, we were still able to investigate the relations between trait social anxiety across conditions, individual differences in the proposed mechanisms of pathology (Clark & Wells, Citation1995) and coherence (Reese et al., Citation2011) via indirect effects (Holmbeck, Citation1997). Interestingly, results showed that trait social anxiety scores were positively associated with an excessive internal focus on cues of anxiety, which related to thematic and total coherence. In the former relation, there was an indirect effect of excessive external focus on social evaluation, working memory load, depressive symptoms and rumination. This is in line with literature suggesting that anxiety can disrupt working memory performance (Baddeley & Hitch, Citation1974), and literature on the relation between the internal focus, rumination and depression (Vanderveren et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the presence of both of an excessive external focus on social threat in combination with the increased internal focus on anxious thoughts and feelings are in line with what is described in cognitive models on social anxiety in the literature (Clark & McManus, Citation2002; Clark & Wells, Citation1995).

However, the novel finding here is that the mechanisms that are proposed to play a role in social anxiety, were also related to thematic coherence, which is a crucial constituting component of total narrative coherence. This is in keeping with broader research that evidences negative relations between narrative coherence and psychopathology (Adler et al., Citation2016; Baerger & McAdams, Citation1999; Habermas & Reese, Citation2015; McLean et al., Citation2010; Reese et al., Citation2017; Vanaken & Hermans, Citation2020a; Vanderveren et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Waters & Fivush, Citation2015).

Possible clinical implications of these results are addressed. Humans all experience a desire for interpersonal relations (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995), which causes us to feel displeased if it remains to be dissatisfied (Maslow, Citation1943), as is largely evidenced by the crucial relation between social support and both mental and physical health (Harandi et al.; Ozbay et al., Citation2007). However, in social anxiety, it is exactly social bonding that poses a major challenge (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Narrating incoherently could evoke negative social evaluations, disturbing the development of supportive relationships and hence forming a maintaining factor in social anxiety disorder (Vanaken et al., Citation2020). Future work in this line of research would be of importance for developing possible interventions, as we could train individuals to become more coherent to evoke positive social feedback from their surroundings. This could then downregulate their focus on negative social evaluation, diminish their working memory load and enable coherent narration (Baddeley & Hitch, Citation1974; Clark & Wells, Citation1995). Receiving positive feedback to coherent narration could in turn make them re-evaluate the association with social situations to a more positive one, diminish negative attentional and memory biases, and help them to decrease negative repetitive thinking (Habermas & Reese, Citation2015). This could consequently help them to install more supportive relationships and improve their well-being (Harandi et al., Citation2017). Of course, further basic research in the domain is needed before it would be possible to develop such experimental intervention.

A couple of limitations are to be addressed in our study. A first comes from the homogeneity of our sample, since it consisted mostly of young, female, psychology students, which are found to generally score higher on neuroticism measures (Vedel et al., Citation2015). Our results confirmed indeed that all participants scored high on arousal, regardless of their psychopathology levels. In a group of already high-strung people, it might have been harder to increase their state differences in anxiety even further. Relatedly, the mere question to rate their fear of negative evaluation, might have been enough to arouse all participants, overruling the effect of our state manipulation following afterwards. Furthermore, although emerging adulthood is a typically used age period in which narrative coherence is measured (Waters & Fivush, Citation2015), our sample’s age was on the border with adolescence, as there were 4 participants (5.6%) still 17 years old. Possibly, for some participants, narrative coherence could still be an ongoing developmental task (Habermas & Bluck, Citation2000).

Another limitation comes from fact that narrative coherence does not merely originate from individual-specific variables, but also from event- and narration-specific variables (Waters et al., Citation2019). We chose to work with a narrative task on turning point memories, since research has shown that it are in particular those memories that are relevant for identity that are likely to serve memories’ social functions (Waters & Fivush, Citation2015). However, turning point memories have found to be in general more coherent, since they are more resolution evoking as well as more practiced in comparison to other memories (McLean et al., Citation2017). Possibly, this might account for the absence of any direct effects of social anxiety on narrative coherence. Future research could work with everyday conversations topics or more mundane event memories, as those might be harder to narrate coherently about for socially anxious people, allowing for more inter-individual variability in coherence (Waters et al., Citation2019). Another distinction could be made in future research between the recall of social vs non-social memories. Possibly, only those memories which concern social topics, and especially memories of past social “failures” are affected by social anxiety in the creation of a coherent narrative (Morgan, Citation2010). Hence, it would be interesting to consider if the narratives of non-social memories would be more coherent than those of social memories.

In addition, we decided on the presence of a listener in only the experimental condition, as part of the manipulation aimed at increasing state social anxiety levels. However, it is known that listeners can have a beneficial role in narrative production and elaboration, for instance by being attentive to the story (e.g., Fioretti et al., Citation2017; Pascuzzi et al., Citation2017; Pasupathi & Billitteri, Citation2015; Pasupathi & Rich, Citation2005). Hence, a possible reason why our manipulation rendered to be ineffective, may have had to do with the fact that the presence of an attentive listener in the experimental condition actually enhanced memory narration, as opposed to hindered it. Future research could use different designs that disentangle the social anxiety induction from the memory recall component to overcome this limitation. For instance, participants could be subjected to a social stress test in the experimental condition, prior to memory recall.

Furthermore, anxious individuals tend to remember more negative events than positive events (Edwards et al., Citation2003), which have found to be more coherently narrated upon, as they ask for more meaning-making effort and resolution formation (Fivush et al., Citation2008; Sales et al., Citation2013; Vanderveren et al., Citation2019). Socially anxious participants might have included more negative events in their narratives, which could have concealed a possible effect of social anxiety on coherence.

Concluding, in this study, trait social anxiety did not have the expected detrimental effect on the coherence of turning point memories. Furthermore, there was no effect of state social anxiety, neither an interaction effect of trait nor state social anxiety on memory coherence. Possibly, our manipulation aimed at increasing state social anxiety did not have the intended effect, as there was a ceiling effect of arousal for all participants during the experiment, irrespective of trait and state social anxiety. However, scores on the investigated mechanisms (external focus on negative social evaluation, internal focus on anxiety cues, working memory load, rumination) were both at the measurement pre-manipulation, at post-manipulation, and with regards to the increase from pre to post, larger for individuals high in trait social anxiety. Since we did find trait differences in the proposed mechanisms in line with the literature, we decided to do an exploratory investigation of their indirect effects on narrative coherence. Results showed that trait social anxiety and thematic memory coherence were indirectly negatively related, via the intervening effects of an increased internal focus on anxiety cues, an excessive external focus on negative social evaluation, larger working memory load, more rumination and more depressive symptoms.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Isis Peiten for her help with the data collection for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The other two functions concern the creation of an identity/sense of self (self-function), and the guidance of future behaviour (directive function) (Bluck, Citation2003; Bluck et al., Citation2005; Pillemer, Citation1992).

References

- Abbott, M. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2004). Post-event rumination and negative self-appraisal in social phobia before and after treatment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.136

- Adler, J. M., Lodi-Smith, J., Philippe, F. L., & Houle, I. (2016). The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well-being: A review of the field and recommendations for the future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(2), 142–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315585068

- Adler, J. M., Waters, T. E. A., Poh, J., & Seitz, S. (2018). The nature of narrative coherence: An empirical approach. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.01.001

- Alea, N., Arneaud, M. J., & Ali, S. (2013). The quality of self, social, and directive memories: Are there adult age group differences? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(5), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413484244

- Alea, N., & Bluck, S. (2003). Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory, 11(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/741938207

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). Academic Press.

- Baerger, D. R., & McAdams, D. P. (1999). Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well-being. Narrative Inquiry, 9(1), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.9.1.05bae

- Barry, T. J., Vinograd, M., Boddez, Y., Raes, F., Zinbarg, R., Mineka, S., & Craske, M. G. (2019). Reduced autobiographical memory specificity affects general distress through poor social support. Memory, 27(7), 916–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1607876

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation.. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.941

- Beike, D. R., Brandon, N. R., & Cole, H. E. (2016). Is sharing specific autobiographical memories a distinct form of self-disclosure? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000143

- Bluck, S. (2003). Autobiographical memory: Exploring its function in everyday life. Memory, 11(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/741938206

- Bluck, S., & Alea, N. (2009). Thinking and talking about the past: Why remember? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(8), 1089–1104. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1612

- Bluck, S., & Alea, N. (2011). Crafting the tale: Construction of a measure to assess the functions of autobiographical remembering. Memory, 19(5), 470–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.590500

- Bluck, S., Alea, N., Habermas, T., & Rubin, D. C. (2005). A TALE of three functions: The self–reported uses of autobiographical memory. Social Cognition, 23(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.23.1.91.59198

- Bluck, S., Baron, J. M., Ainsworth, S. A., Gesselman, A. N., & Gold, K. L. (2013). Eliciting empathy for adults in chronic pain through autobiographical memory sharing. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2875

- Boals, A., Banks, J. B., Hathaway, L. M., & Schuettler, D. (2011). Coping with stressful events: Use of cognitive words in stressful narratives and the meaning-making process. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 378–403. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.4.378

- Brozovich, F., & Heimberg, R. G. (2008). An analysis of post-event processing in social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 891–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.002

- Burnell, K. J., Coleman, P. G., & Hunt, N. (2010). Coping with traumatic memories: Second world war veterans’ experiences of social support in relation to the narrative coherence of war memories. Ageing and Society, 30(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X0999016X

- Buxton, B. A. (2016). The relationships among rumination, memory coherence, and well being in a Community sample of adolescents (Unpublished master's thesis). Victoria University of Wellington.

- Chen, Y., McAnally, H. M., Wang, Q., & Reese, E. (2012). The coherence of critical event narratives and adolescents’ psychological functioning. Memory, 20(7), 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.693934

- Clark, D. M., & McManus, F. (2002). Information processing in social phobia. Biological Psychiatry, 51(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01296-3

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). The Guilford Press.

- Conway, M. A. (2005). Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language, 53(4), 594–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005

- Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.107.2.261

- Conway, M. A., Singer, J. A., & Tagini, A. (2004). The self and autobiographical memory: Correspondence and coherence. Social Cognition, 22(5), 491–529. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.22.5.491.50768

- de Beurs, E., Van Dyck, R., Marquenie, L. A., Lange, A., & Blonk, R. W. B. (2001). De DASS: Een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress [The DASS: A questionnaire for the measurement of depression, anxiety, and stress]. Gedragstherapie, 34(1), 35–53.

- Dickson, J. (2004). Autobiographical memory and social anxiety: The impact of self-focus priming on recall [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Swinburne University of Technology.

- Edwards, S. L., Rapee, R. M., & Franklin, J. (2003). Postevent rumination and recall bias for a social performance event in high and low socially anxious individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(6), 603–617. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026395526858

- Field, A. P., & Morgan, J. (2004). Post-event processing and the retrieval of autobiographical memories in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.08.004

- Fioretti, C., Pascuzzi, D., & Smorti, A. (2017). The role of the listener on the emotional valence of personal memories in emerging adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 24(4), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-017-9263-z

- Fivush, R. (2011). The development of autobiographical memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 559–582. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131702

- Fivush, R., Berlin, L., McDermott Sales, J., Mennuti-Washburn, J., & Cassidy, J. (2003). Functions of parent-child reminiscing about emotionally negative events. Memory, 11(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/741938209

- Fivush, R., Habermas, T., Waters, T. E. A., & Zaman, W. (2011). The making of autobiographical memory: Intersections of culture, narratives and identity. International Journal of Psychology, 46(5), 321–345. https://doi/org/10.1080/00207594.2011.596541

- Fivush, R., Haden, C. A., & Reese, E. (2006). Elaborating on elaborations: The role of maternal reminiscing style in cognitive and socioemotional development. Child Development, 77, 1568–1588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00960.x

- Fivush, R., McDermott Sales, J., & Bohanek, J. G. (2008). Meaning making in mothers’ and children’s narratives of emotional events. Memory, 16(6), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802150681

- Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 823–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823

- Habermas, T., & Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 748–769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

- Habermas, T., & Reese, E. (2015). Getting a life takes time: The development of the life story in adolescence, its precursors and consequences. Human Development, 58(3), 172–201. https://doi.org/10.1159/000437245

- Harandi, F. T., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, D. T. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212

- Heimberg, R., Horner, K., Juster, H., Safren, S., Brown, E., Schneier, F., & Liebowitz, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz social anxiety scale. Psychological Medicine, 29(1), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798007879

- Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.599

- Horselenberg, R., Merckelbach, H., van Breukelen, G., & Wessel, I. (2004). Individual differences in the accuracy of autobiographical memory. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11(3), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.400

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

- Kessler, R. C., Stang, P., Wittchen, H.-U., Stein, M., & Walters, E. E. (1999). Lifetime comorbidities between social phobia and mood disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine, 29(3), 555–567. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799008375

- Klein, K., & Boals, A. (2001). Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.520

- Krans, J., de Bree, J., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Autobiographical memory bias in social anxiety. Memory, 22(8), 890–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2013.844261

- Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation.

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

- McAdams, D. P. (2006). The problem of narrative coherence. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530500508720

- McLean, K. C., Breen, A. V., & Fournier, M. A. (2010). Constructing the self in early, middle, and late adolescent boys: Narrative identity, individuation, and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 166–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00633.x

- McLean, K. C., & Lilgendahl, J. P. (2008). Why recall our highs and lows: Relations between memory functions, age, and well-being. Memory, 16(7), 751–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802215385

- McLean, K. C., Pasupathi, M., Greenhoot, A. F., & Fivush, R. (2017). Does intra-individual variability in narration matter and for what? Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.003

- McLean, K. C., & Pratt, M. W. (2006). Life's little (and big) lessons: Identity statuses and meaning-making in the turning point narratives of emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 714–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.714

- Mellings, T. M. B., & Alden, L. E. (2000). Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00040-6

- Mitchell, C., Reese, E., Salmon, K., & Jose, P. (2020). Narrative coherence, psychopathology, and wellbeing: Concurrent and longitudinal findings in a mid-adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.003

- Morgan, J. (2010). Autobiographical memory biases in social anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.003

- Nelson, K. (2003). Narrative and self, myth and memory: Emergence of the cultural self. In R. Fivush, & C. A. Haden (Eds.), Autobiographical memory and the construction of a narrative self: Developmental and cultural perspectives (pp. 3–28). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Nelson, K., & Fivush, R. (2004). The emergence of autobiographical memory: A social cultural developmental theory. Psychological Review, 111(2), 486–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.486

- NIMH. (2014). Social anxiety disorder. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

- Ohayon, M. M., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2010). Social phobia and depression: Prevalence and comorbidity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(3), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.018

- Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa.: Township)), 4, 35–40. www.cancer.gov

- Palombo, D. J., Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2018). Individual differences in autobiographical memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(7), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.04.007

- Pascuzzi, D., Fioretti, C., & Smorti, A. (2017). Sharing of emotional memories with a listener: Differences between adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(7), 927–944. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1273521

- Pasupathi, M. (2001). The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychological Bulletin, 127(5), 651–672. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.5.651

- Pasupathi, M., & Billitteri, J. (2015). Being and becoming through being heard: Listener effects on stories and selves. International Journal of Listening, 29(2), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2015.1029363

- Pasupathi, M., Lucas, S., & Coombs, A. (2002). Conversational functions of autobiographical remembering: Long-married couples talk about conflicts and pleasant topics. Discourse Processes, 34(2), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326950DP3402_3

- Pasupathi, M., & Rich, B. (2005). Inattentive listening undermines self-verification in personal storytelling. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 1051–1086. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00338.x

- Pillemer, D. B. (1992). Remembering personal circumstances: A functional analysis. In E. Winograd & U. Neisser (Eds.), Emory symposia in cognition, 4. Affect and accuracy in recall: Studies of “flashbulb” memories (pp. 236–264). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511664069.013

- Raes, F., Hermans, D., Williams, J. M. G., & Eelen, P. (2006). Reduced autobiographical memory specificity and affect regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 20(3-40), 402–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500341003

- Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.005

- Reese, E., Haden, C. A., Baker-Ward, L., Bauer, P., Fivush, R., & Ornstein, P. A. (2011). Coherence of personal narratives across the lifespan: A multidimensional model and coding method. Journal of Cognition and Development, 12(4), 424–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2011.587854

- Reese, E., Myftari, E., McAnally, H. M., Chen, Y., Neha, T., Wang, Q., Jack, F., & Robertson, S.-J. (2017). Telling the tale and living well: Adolescent narrative identity, personality traits, and well-being across cultures. Child Development, 88(2), 612–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12618

- Rimé, B., Finkenauer, C., Luminet, O., Zech, E., & Philippot, P. (1998). Social sharing of emotion: New evidence and new questions. European Review of Social Psychology, 9(1), 145–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779843000072

- Sales, J. M., Merrill, N. A., & Fivush, R. (2013). Does making meaning make it better? Narrative meaning making and well-being in at-risk African-American adolescent females. Memory, 21(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.706614

- Sutin, A. R., & Robins, R. W. (2007). Phenomenology of autobiographical memories: The memory experiences questionnaire. Memory, 15(4), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701256654

- Tulving, E. (2002). Episodic memory and common sense: How far apart? In A. Baddeley, J. P. Aggleton, & M. A. Conway (Eds.), Episodic memory: New directions in research (pp. 269–287). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198508809.003.0015

- Vanaken, L., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2020). I like you better when you are coherent. Narrating autobiographical memories in a coherent manner has a positive impact on listeners’ social evaluations. PloS one, 15(4). Article e0232214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232214

- Vanaken, L., & Hermans, D. (2020a). Form follows function. A longitudinal investigation of the relations between narrative coherence, psychological well-being, internalizing symptoms and social bonding. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Vanaken, L., & Hermans, D. (2020b). Be coherent and become heard: The multidimensional impact of narrative coherence on listeners’ social responses. Memory & Cognition, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-020-01092-8

- Vanderveren, E., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2019). Autobiographical memory coherence and specificity: Examining their reciprocal relation and their associations with internalizing symptoms and rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.02.003

- Vanderveren, E., Bijttebier, P., & Hermans, D. (2020). Autobiographical memory coherence in emotional disorders: The role of rumination, cognitive avoidance, executive functioning, and meaning making. PLoS One, 15(4). Article e0231862. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231862

- Van Vliet, I. M. (1999). Nederlands vertaling van de Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Unpublished Dutch translation.

- Vedel, A., Thomsen, D., & Larsen, L. (2015). Personality, academic majors and performance: Revealing complex patterns. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.030

- Waters, T. E. A., & Fivush, R. (2015). Relations between narrative coherence, identity, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality, 83(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12120

- Waters, T. E. A., Köber, C., Raby, K. L., Habermas, T., & Fivush, R. (2019). Consistency and stability of narrative coherence: An examination of personal narrative as a domain of adult personality. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12377

- Williams, J. M. G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122