ABSTRACT

The scoping review examines and summarises the available knowledge base on intervention techniques focused on positive memories. An iterative series of PsycInfo and Medline searches was conducted up to April 2021 following PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Thirty-nine studies, spanning 12 intervention techniques, were selected and described including: (1) theoretical basis; (2) type of study, sample, and measures; (3) intervention protocol; and (4) results of empirical studies if applicable. Results indicated that most techniques have only been tested in one-two studies with modest sample sizes and, when follow-ups are conducted, they are typically short. Results indicate that working with positive memories has the greatest impact on improving positive affect and reducing depressive symptoms, and that these effects are often temporary. This review serves as a quick reference guide to help professionals’ access to descriptions and information on empirical evidence of positive memory techniques, improving their therapeutic arsenal to enhance well-being and therapeutic outcomes in their patients.

Introduction

Autobiographical memories consist of retrieved episodes occurring in an individual’s life, which combines the memories of specific episodes (i.e., episodic memory), as well as generic and schematic knowledge about the word (i.e., semantic memory; Williams et al., Citation2008). Autobiographical memories play a central role in an individual’s functioning and sense of self (Williams et al., Citation2007). Several features of autobiographical memories have been linked to various psychopathological conditions, examples include memory overgenerality with depression (e.g., Williams et al., Citation2007), and vivid recollections of the traumatic event with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; e.g., Crespo & Fernández-Lansac, Citation2016). In fact, Romano et al. (Citation2020) recently suggested that autobiographical memory bias could be considered a transdiagnostic process that perpetuates negative and distorted self-representations.

Beyond memories of negative or traumatic events, recent studies have indicated difficulties in positive memory processes (e.g., the retrieval) in relation to psychopathology such as depressive disorders (Dalgleish & Werner-Seidler, Citation2014), PTSD (Bryant et al., Citation2007), and engagement in reckless behaviours (Banducci et al., Citation2020). To elaborate, Werner-Seidler and Moulds (Citation2011) found that formerly depressed individuals rated their positive memories as less vivid than their never-depressed counterparts; Fernández-Lansac and Crespo (Citation2015) found that shorter narratives of positive events predicted psychological symptoms in trauma-exposed women; and Contractor et al. (Citation2019) found that reduced count of positive memories was associated with greater PTSD severity.

Importantly, research indicates beneficial effects of retrieving positive memories, such as greater positive affect and decreased negative affect (e.g., Joormann et al., Citation2007) and reduced post-trauma maladaptive cognitions (Askelund et al., Citation2019). Actually, this subsequently improved affect has other downstream consequences; positive emotions have an adaptive function and relate to several aspects of well-being, such as life satisfaction or adaptive responses to negative events (Waugh, Citation2020). Furthermore, Speer and Delgado (Citation2017) could relate the recall of positive versus neutral memories to different neurophysiological processes.

Such research has led to an increasing interest in the development of interventions that capitalise on positive memories to promote life satisfaction and well-being (Hendriks et al., Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, we have seen a surge in the number of positive memory interventions that are quite heterogenous in theoretical foundations, content, formats, applications, and extent of supporting evidence. To summarise this existing knowledge base, we conducted a review of currently used positive memory intervention techniques, providing a description of each technique and any empirical evidence regarding its effectiveness/utility. Results of this scoping review may be a first step to facilitate access to and dissemination of these techniques among professionals, with the final goal of increasing one’s therapeutic arsenal to enhance well-being and health in different patient populations. In this regard, clinicians may even consider adding one of these techniques to conventional treatments in order to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Method

Search strategy and data extraction

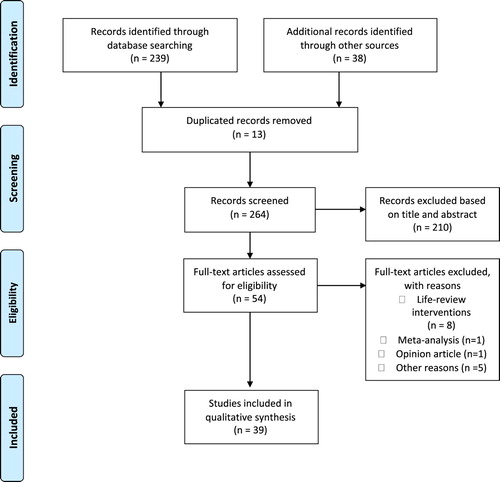

We carried out a scoping review following existing guidelines (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010), including the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018). We conducted an iterative series of PsycInfo and Medline searches. In terms of the timeframe for the search, we had no specific start date and we included papers published up to April 2021. We reviewed abstracts using a combination of two sets of terms: (“positive memories” OR “positive memory”) AND (“intervention*” OR “treatment” OR “therap*” OR “technique”). Additional articles were identified via hand-searching and reviewing reference lists of shortlisted articles from the initial search. Inclusion criteria for the selected articles were: (1) they focused on the application of a positive memory intervention technique or were a description of a positive memory intervention protocol; (2) they were peer-reviewed journal articles or book chapters; and (3) they were in Spanish or English. Two authors independently reviewed all abstracts and entire manuscripts of identified relevant studies. Using standardised forms, two researchers independently extracted the following information from each shortlisted intervention: (1) theoretical basis; (2) type of study, sample, and/or measures; (3) information about the intervention protocol (i.e., format, number of sessions, frequency, duration, number of retrieved positive memories); and (4) results of any empirical studies if applicable. Information about each shortlisted positive memory intervention technique is provided in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the reviewed interventions.

Results

As outlined in , we reviewed a final list of 39 articles: 36 articles provided empirical data on intervention effects, and three articles described the intervention. A total of 12 positive memory intervention techniques were shortlisted; we classified them in three blocks based on their primary treatment focus and objective: a) techniques aiming to increase the reminiscence of, accessibility to, and focus on positive memories to facilitate therapeutic change (six techniques); b) techniques aiming to change quality or specific features of positive memories to facilitate therapeutic change (two techniques); c) techniques directly focused on specific therapeutic changes, namely self-esteem improvement (two techniques); or emotional regulation (two techniques). As a caveat, we acknowledge the preliminary nature of this classification based on predominant themes. Below, we outline a description of the main features, the procedures employed, and any empirical results on treatment effectiveness and utility for each technique grouped according to the aforementioned blocks.

Techniques to increase accessibility to and focus on positive memories

This block consists of techniques aiming to increase the reminiscence of, accessibility to, and focus on positive memories to facilitate emotional or cognitive change, symptom reduction, and health improvement. Notably, the action mechanisms for such therapeutic changes are not well established for most techniques.

Re-experiencing pleasant memories using mental imagery

Bryant et al. (Citation2005) developed this technique based on their interest in studying the role of different ways of reminiscing about pleasant memories in young populations. Methodologically, participants are instructed to choose a positive personal memory from a previously created list, to practice relaxation, and to think about the positive memory with closed eyes. They are instructed to allow all images related to the memory to come into their mind, to try to imagine any events related to the memory, and to think about the details of the memory while they imagine it. They practice this exercise twice a day (∼10 min) over the course of a week.

Empirically, this technique was studied among 65 undergraduate students assigned to one of the three groups: (1) use of mental imagery to stimulate retrieval of positive memories as established in the protocol; (2) use of physical objects (e.g., photos) as mementos; and (3) thinking about current concerns (control group). Study results revealed that both forms of reminiscence (vs. the control group) increased feelings of happiness during the week. Further, the group utilising mental imagery vs. physical objects reported more vivid positive memories; no differences were observed between the two groups in the degree of detail of the retrieved memories.

It is worth highlighting that the study used an ad-hoc scale to assess the feelings of happiness (i.e., the participants estimated the percentage of time during which they had felt happy, unhappy, and neutral over the past week) and no data were provided on the reliability and validity of this scale. Nonetheless, results seem promising because this technique (1) entails an easy and short practice (only spanning a week), and (2) empirically impacted happiness and vividness of positive memories, although their clinical utility would depend on long-term maintenance of obtained effects which would require further research.

Broad-Minded affective coping (BMAC) intervention

Tarrier proposed BMAC in 2010 as a “positive” cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) approach to facilitate positive emotions; this intervention focuses on experiencing positive memories through mental imagery exercises and on experiencing the positive emotions associated with these memories. Aims of this intervention include: (1) to focus the mind on a positive memory, rather than on a negative, unpleasant or traumatic memory, and to achieve a balance between positive and negative memories; (2) to learn to control emotions and to enjoy positive emotions and associated benefits; (3) to learn to have more control over attention and thinking; (4) to learn to cope with stress and low mood; and (5) to increase awareness of how thinking processes can affect emotions. Methodologically, pre-intervention, participants retrieve an event associated with enjoyment, fun, and happiness (they are encouraged to retrieve more recent events due to likelihood of their memories being more vivid and detailed). Thereafter, participants are taken through guided imagery of positive memories (engaging all the senses) and re-experiencing of the associated emotions. The technique consists of one to three sessions, each lasting between 20 and 30 min.

Empirically, BMAC has been examined among individuals with PTSD (Panagioti et al., Citation2012) and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (Johnson et al., Citation2012; Mote & Kring, Citation2019), and among university students (Holden et al., Citation2017). Panagioti et al. (Citation2012) compared a group receiving BMAC (one session lasting 15–20 min) to a control group that wrote a detailed description of a positive memory for 15 min. Participants in the BMAC group reported more positive emotions, fewer negative emotions, and improved mood; the control group did not report substantial improvements in mood. Notably, effects were not sustained two hours and two days after the experiment; there was no significant impact of the condition (BMAC vs. control) on either positive or negative emotions, after controlling for the baseline levels of previous emotions. Findings suggest a transitory effect, which, as indicated by the authors, may be of value in facilitating the therapeutic process when used in conjunction with other interventions.

Further, in the study by Johnson et al. (Citation2012), BMAC was administered in a 20-minute session and compared to a time-matched task of listening to classical music (control). In the post-induction assessment, participants in the BMAC group displayed greater increases in two visual-analogue scales that measured hope and happiness felt at that moment. Meanwhile, the study conducted by Mote and Kring (Citation2019) compared the effects of BMAC across individuals with vs. without schizophrenia (average session was ∼35 min). BMAC significantly increased positive affect in both groups but did not influence negative affect. Finally, several new features were introduced for implementing BMAC with university students (Holden et al., Citation2017): focus on positive social memories (labelled “social BMAC”) and an online format. In the study, 123 students recalled a recent positive social memory, and they were provided auditory instructions that guided them through an initial relaxation exercise, before listening to the recorded social BMAC (session lasted ∼45 min). Results demonstrated significant increases (small to moderate) in positive affect, feelings of social security, and pleasure; and a significant decrease in negative affect post-session. However, these results should be considered with caution since the study did not include a control group, and changes were not sustained over the two-week follow-up period.

Although the effects of BMAC do not maintain over time, according to the authors, BMAC may potentially facilitate the therapeutic process if used as an adjunct to psychological interventions. Finally, it should be noted that although the original protocol (Tarrier, Citation2010) proposes the application of BMAC in one-three sessions, all studies conducted to date have used a single session.

Writing about a peak positive experience

Initially described by Burton and King (Citation2004), this technique is based on evidence of the psychological benefits that can be gained from writing about emotional topics. Methodologically, this intervention is conducted in three individual 20-minute sessions over three consecutive days. Participants choose one of the most wonderful experiences/moments in their life (namely peak positive experience) and imagine themselves in that moment, while trying to include all the emotions associated to it. Next, they write about the experience in detail, including the feelings and thoughts that were present. Meanwhile, they are encouraged to try to re-experience the emotions as they write. The same procedure is repeated in the second and third sessions; participants can choose similar or different experiences.

Empirically, this protocol has been examined with undergraduate students in two studies (Burton & King, Citation2004, Citation2009). Both studies included an experimental group with this intervention and a control group (participants wrote a neutral story). In the first study, Burton and King (Citation2004) found that the experimental group displayed higher positive affect after the exercise, with no difference in negative affect between the two conditions. In the second study, Burton and King (Citation2009) found that 4–6 weeks post-intervention, the experimental vs. control group had better perceived physical health.

This aforementioned research demonstrates that writing about positive experiences (specifically, a “peak” one) can also have benefits on health outcomes. This is an important complement to the well-established therapeutic value of writing about negative/traumatic experiences (e.g., Pennebaker, Citation1993). However, as the authors indicate, it is necessary to carry out further research with more rigorous experimental designs to understand the mechanisms of action of this type of technique as well as its application in clinical contexts.

Positive writing

Similarly, Baikie et al. (Citation2012) suggested that writing about positive life events can benefit health outcomes in non-clinical and clinical populations. Consequently, they developed an intervention protocol focused on positive writing that is applied in four individual 20-minute sessions. Methodologically, over four consecutive days, participants write down their deepest thoughts and feelings about the most intensely positive experience of their life or an extremely important positive issue that has affected them or their life (they could write about the same or different topics or experiences).

Empirically, positive writing was tested by Baikie et al. (Citation2012) with 225 adult participants (online format). Of these participants, 79 engaged in positive writing, 70 participated in an expressive writing group focused on the most traumatic events, and 86 were placed in the control group, in which they wrote objectively about how they spent their time each day. Contrary to expectations, the three groups displayed a significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention on physical and emotional health self-report measures, with no significant differences between the groups. These gains continued at the 1-month follow-up timepoint and remained stable at four-months follow-up. The combined positive writing and expressive writing group showed significantly lower Depression Anxiety Stress Scale subscale scores at all three points of measurement compared to the control group.

The positive expressive writing technique has been applied subsequently with students in a study conducted by Allen et al. (Citation2020). This intervention consisted of three 20-minute online sessions over three consecutive days. Participants were assigned to either the positive writing group or a neutral writing control group. Results showed no significant differences between the two groups at post-test and at four-weeks follow-up. However, the results suggested the moderating role of social inhibition; socially inhibited participants in the experimental group had a significant reduction in anxiety and stress reactivity at follow-up compared to the control group.

Broadly, this aforementioned research indicates the usefulness of therapeutic writing when it addresses positive aspects of an individual’s life. Furthermore, evidence suggests utility in using an online format for these techniques, which may contribute to uptake from and reach to clinically and demographically diverse individuals. Finally, as Contractor et al. (Citation2020a) indicate, one limitation when conducting research on therapeutic writing is the lack of consistency with respect to outcome variables examined in the paradigms of emotional writing.

Sharing positive narratives with a partner

Lambert et al. (Citation2013) developed the “sharing positive narratives with a partner” technique based on the premise that gratitude diaries improve mood. Methodologically, participants keep a report of grateful experiences for four weeks. They spent five minutes every night thinking and writing about what they were grateful for and why. Twice a week, participants complete an online survey and share what they had written. In addition, at least twice a week, participants are encouraged to share the grateful experiences noted down in their diaries with other individuals.

Empirically, Lambert et al. (Citation2013) tested the strategy with 137 undergraduate students assigned to three conditions. In the first group, the aforementioned technique was applied; in the second group, the same technique was used but participants did not share their grateful experiences with others; and in the neutral group, participants wrote about what they had learned in class. Results revealed that the first group displayed more positive affect, happiness, vitality, and life satisfaction than the other two groups.

In summary, gratitude journals can increase positive affect when participants share their positive experiences with others. In addition, it would be beneficial for future research to examine whether such a component can enhance impact of other therapeutic techniques utilising positive memories.

Processing of Positive Memories Technique (PPMT)

Contractor et al. (Citation2018; Contractor et al., Citationin press) outlined a conceptual model linking processing of positive memories to improved PTSD severity via hypothesised mechanisms such as affect and cognitive change, increased readiness for trauma-focused interventions, and enhanced treatment retention. Based on this model, Contractor et al. (Citation2020a) proposed a manualized positive memory therapy protocol for trauma-exposed individuals. The procedure would consist of five sessions, the first lasting 120 min and the remaining four 60 min. First session goals include establishing a therapeutic rapport with participants, assess their psychiatric history, and providing psychoeducation about relations between PTSD symptoms and positive memories. In the second session, participants are trained in imagining experiences and how to elicit and process positive memories. To select the positive memory to work with, the therapist defines a positive memory and asks participants to select one specific positive memory to be used in the following session. Next, participants imagine and provide details of that selected positive memory as guided by the therapist. In the processing phase, the therapist asks participants to retrieve positive thoughts, feelings, emotions, and strengths associated with the target memory. It should be noted that the narration of the memory is recorded so that the participant can listen to it daily as an homework assignment. In the third and fourth session, participants continue to practise the procedure with a different memory. Finally, the fifth session goals include assessment of progress and transition of care/termination.

Empirically, Contractor et al. (Citation2020b) conducted an experimental design to examine impact of positive memory processing on post-trauma outcomes. Methodologically, the procedure was somewhat different from the one described in the protocol (Contractor et al., Citation2020a). This procedure consists of recalling a salient and specific positive memory and then either writing about it or narrating it to another person (each lasting ∼30 min). The authors tested both procedures in a study with 65 university students who had experienced a traumatic event: 22 were assigned to the writing condition, 22 to the narrative condition, and the remaining 21 to a control condition in which they had to write the maximum number of examples for a proposed category. The intervention was applied with each group on two separate occasions, six-eight days apart. The results showed a significant decrease in PTSD symptom severity and negative affect and an increase in positive affect in the narrative condition. Meanwhile, in the writing condition, positive affect increased after the first application but decreased after the second application; negative affect decreased after the first application before increasing after the second application. Overall, results suggest that narrating positive memories produced greater health benefits than writing about positive memories.

In summary, narrating and processing of positive memories had beneficial impacts on post-trauma outcomes. Future empirical research needs to investigate effects of positive memory techniques in the treatment of PTSD and other post-trauma psychopathology.

Techniques to change quality or specific features of positive memories

This block includes two techniques aimed to improve specificity and quality of autobiographical memory of positive events. They were initially designed to treat depression symptoms based on the data about overgeneralisation in autobiographical memory and the poorest quality of positive memories among depressed patients.

Memory specificity training (MEST)

MEST (Raes et al., Citation2009) is based on the premise that individuals with depression display reduced specificity in autobiographical memory retrieval. Thus, MEST aims to improve autobiographical memory specificity; it is conducted in groups of three-eight individuals over four weekly sessions of one-hour duration each.

In the first session, participants receive psychoeducation on the functioning of and changes in memory in relation to depression; and training to retrieve memories in response to positive/neutral emotional cues and to describe retrieved memories in detail. In the second session, participants generate memories in response to two positive and two neutral cues (selecting two specific memories for each category in order to reduce over-generalisation); they focus on two contrasting memories considering the elements rendering each memory specific/unique; and receive homework (e.g., retrieving two memories for each of the ten positive/neutral cues, writing two specific memories from the day). The third session is similar in content to the previous session; differently, this session incorporates working with negative cues. The fourth session includes an explanation of specific additional exercises utilising negative and positive cues, and a review of participants’ gain in knowledge about autobiographical memory specificity and depression.

Empirically, MEST was originally piloted with 10 women reporting significant depressive symptoms (Raes et al., Citation2009). Results indicated a significant reduction in ruminative processes and feelings of hopelessness post-intervention. Since the initial study, the MEST protocol has been implemented in multiple studies that, in general, are more methodologically sound due to the inclusion of a control group: individuals with depression, including adults (Eigenhuis et al., Citation2017; Sadat Zia et al., Citation2021) and adolescents (Neshat-Doost et al., Citation2013; Werner-Seidler et al., Citation2018); war veterans with PTSD (Moradi et al., Citation2014); oncology patients with PTSD (Farahimanesh et al., Citation2020; Farahimanesh et al., Citation2021); and individuals with mild amnesiac cognitive impairment (Emsaki et al., Citation2017). These studies follow the MEST original protocol, but few studies utilised five sessions (i.e., Emsaki et al., Citation2017; Neshat-Doost et al., Citation2013; Werner-Seidler et al., Citation2018). A meta-analysis by Barry et al. (Citation2019), suggests that MEST is associated with a significant post-intervention improvement of depressive symptoms (d=0.47) and, in particular, of autobiographical memory specificity (d=−1.21). However, these effects are transient and are not retained in follow-up assessments. It is worth noting that recently, in the work of Hallford et al. (Citation2021), the technique was adapted for online application under the name of Computerized Memory Specificity Training (c-MEST). The authors applied it to a sample of 245 patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder; these patients were compared to a wait list control group. The c-MEST group, relative to the control group, scored significantly higher on memory specificity at all time-points following baseline, and lower on depressive symptoms at one and three-month follow-ups.

In conclusion, MEST holds promise as a novel intervention targeting autobiographical memory specificity and psychological symptoms. This being said, the authors emphasise investigations to understand underlying mechanisms of action. In addition, research should be done on how to maintain the transitory effects of MEST, and attention should be paid to mediating and moderating aspects such as effects of memory characteristics in terms of veracity of remembered details and generated emotional valence.

Positive Memory Enhancement Training (PMET)

Proposed by Arditte Hall et al. (Citation2017), PMET aims to increase the quality of positive memories as a means to reduce sadness in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). PMET is applied in an individual session format (single session) and consists of two phases: practical and training. In the practical phase, participants work with multi-sensory mental images through an exercise consisting of imagining a lemon at all sensory levels. Next, participants retrieve autobiographical memories using cues that represent common events. The final step involves using these cues to recall a sad memory and then a happy memory; followed by additional procedures to obtain a more vivid quality of a memory focused on the present. In the training phase, participants retrieve 16 memories related to eight cues (one sad and one happy memory for each cue for three minutes each). The happy memories are provided with the same procedures as in the previous phase; the therapist encourages participants to relive the event in the first person, asks questions about where they feel their emotions, etc.

PMET was pilot-tested by Arditte Hall et al. (Citation2017) on 27 patients diagnosed with MDD: 13 were assigned to the experimental group (i.e., PMET condition), and 14 were placed in a control group, which employed the same procedure as in PMET but with the focus on neutral emotional memories. As expected, participants in the PMET group (who had to recall a sad memory in the practical phase) reported more sadness than the control group (who had to remember a neutral memory). However, they were able to successfully reverse their negative mood by recalling positive memories.

Thus, evidence suggests that training individuals to retrieve positive memories in a vivid/detailed manner can correct autobiographical memory biases, increase positive affect, and facilitate emotion regulation in depressed patients. However, what has not been examined is whether the obtained effects are maintained over time and how PMET compares in terms of its effects to emotional regulation strategies. Moreover, as pointed out by the authors, it is uncertain if PMET would have the same effect in real life when individuals with depression spontaneously experience acute negative affect. In conclusion, PMET is a promising technique that needs further empirical research.

Techniques focused on specific therapeutic changes

This final block includes several techniques that, through the use of and/or capitalisation on positive memories, target specific therapeutic changes, namely improved self-esteem (two techniques) or emotional regulation (two techniques). Such therapeutic effects, in turn, could facilitate symptom improvement for diverse clinical conditions.

Competitive memory training (COMET)

Initially proposed by Korrelboom (Citation2000), COMET is a manualised intervention that is applied progressively to address low self-esteem. The intervention is conducted in groups of six-eight individuals over eight weekly sessions of one and a half hours each. Methodologically, COMET includes four steps. First, participants describe negative aspects to identify their negative self-image. Second, participants create a realistic, positive self-image incompatible with the negative self-image by questioning whether their identified negative self-image is true and by identifying personal characteristics and experiences that contradict the negative self-image. The third step is to consolidate the generated positive self-image by strengthening emotional load; proposed exercises conducted between Sessions two to five include writing short personal stories involving positive qualities, imagining oneself in situations that highlight positive personal qualities, deliberately manipulating body posture and facial expression, and listening to music related to their positive image. The fourth step employs counter-conditioning techniques to associate the cues that provoked negative cognitions with thoughts about the positive self-image.

Empirically, Korrelboom`s research group has implemented COMET in a good number of studies addressing diverse symptomatology and conditions. The two initial pilot studies employed a pre–post comparison for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Korrelboom et al., Citation2008) and self-esteem (Korrelboom et al., Citation2009a); while most other studies have compared COMET vs. treatment-as-usual (TAU) for eating disorders (Korrelboom et al., Citation2009b), personality disorders (Korrelboom et al., Citation2012), depression (Ekkers et al., Citation2011; Korrelboom et al., Citation2012) and schizophrenia (van der Gaag et al., Citation2012). Additionally, one study compared COMET vs. relaxation for panic disorder (Korrelboom et al., Citation2014). All of them applied COMET in group format in seven-eight weekly sessions lasting 90–120 min each (but the initial pilot study by Korrelboom et al., Citation2008 utilised sessions of 45 min each). Further, van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020) conducted a randomised controlled trial with 54 patients diagnosed with personality disorders in which they compared the effectiveness of two eight-week group modules with TAU. The group modules were schema mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (SMBCT) and COMET. In contrast, most recent studies have used individual sessions; Staring et al. (Citation2016) compared two different sequences of combined Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) and COMET (i.e., EMDR + COMET vs. COMET + EMDR) for anxiety disorders, while Schneider et al. (Citation2015) compared COMET vs. waiting list control for OCD using an individual internet-delivered self-help format (eight sessions). On the other hand, the work of Farahimanesh and colleagues in Citation2020 and Citation2021 provides results of the application of COMET among 60 oncology patients who reported trauma experiences. In this case, COMET was also applied using an individual format in seven weekly sessions and compared to the application of MEST.

Overall, results suggest that COMET produces significantly greater post-intervention improvements in depressive symptomatology, post-trauma symptomatology, obsessive-compulsive symptomatology, self-esteem and a significant alleviation in autobiographical memory bias, compared to TAU and other comparison interventions. However, not all studies confirm the incremental clinical benefits of COMET; Korrelboom et al. (Citation2014) found that relaxation was equally effective as COMET in reducing panic disorder symptoms. Likewise, in the study by Schneider et al. (Citation2015), results failed to show that COMET reduced obsessive-compulsive or depressive symptoms in participants with OCD after four weeks of the intervention. Furthermore, the study revealed difficulties in adherence to treatment with this self-administration approach. On the other hand, van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020) found that both treatments were effective, but the treatment with COMET was no more effective than the treatment with SMBCT. Moreover, the authors informed that around 23% of patients showed symptoms deterioration after treatment.

All in all, COMET, mainly in group format, has shown remarkable effects on self-esteem which is a therapeutic target of many mental health interventions. Thus, COMET may have potential at a transdiagnostic level in reducing broader psychopathology symptoms. However, studies do not record whether participants performed the assigned tasks. In addition, there is a need to study in greater depth whether obtained effects are attributable to the application of COMET or are due to other variables such as the successful completion of the tasks assigned as homework or therapist effects.

Positive memory training (PoMeT) protocol

PoMeT (Steel et al., Citation2015) is an adaptation of the COMET protocol designed to improve access to positive self-representations (thus self-esteem) in patients with schizophrenia and comorbid depression. PoMeT adapts the duration to the type of user, proposing an individual treatment with a minimum of eight and a maximum of 10 sessions (one-hour duration each) spanning three months. Methodologically, in the first step, participants identify their central and defining negative self-representations. Next, they provide real memories that contradict the veracity of the selected negative self-representations. The next few sessions focus on eliciting positive memories through the use of mental images, postures, self-statements, etc. In the final stage, participants are trained to activate positive self-representations when cues activate negative ones.

Despite the high co-presentation of schizophrenia and depression, no existing treatments address this co-occurring symptomatology; the PoMeT protocol has potential application in this regard. In fact, it was first tested by Steel and colleagues (Citation2020) in a sample of 100 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and at least mild depression. They were randomly assigned to a PoMeT (n = 49) or a TAU (n = 51) group. Compared to the TAU group, those receiving the PoMeT intervention showed a moderate and significant treatment effect on the primary outcome (depression) at three months (end of treatment). Although the gains were maintained in the experimental group, the effect diminished over time and was not significant at either six or nine months. Authors concluded that this brief targeted intervention could reduce depressive symptoms in this clinical population and the main limitation of the study was that the comparison group did not control for therapist contact time or provided an active treatment.

Mood-Regulation focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (MR-CBT)

MR-CBT, proposed by Högberg and Hällström (Citation2018), aims to achieve emotional regulation through counter-conditioning techniques. Participants are trained to retain memories that generate positive emotions to reduce emotional impacts of negative memories. According to the authors, the action mechanism of this technique is based on memory reconsolidation, since the goal is to learn a new affective response to memories that are activated by evocation.

MR-CBT is applied and individualised to the clinical needs of patients rather than with a specific pre-determined frequency. However, authors recommend an average of 12 sessions and an average treatment duration of eight months. Methodologically, the first step is to create a “mood map;” participants draw a sketch that places them in the middle of the sketch, surrounded by their different moods. This map is useful for exploring current and desired future mood, as well as how to achieve the latter. Although MR-CBT focuses primarily on working with memories of recent events, the authors prioritise working with nightmares, flashbacks of traumatic events, reactions to grief, fear of the future, and ruminative thoughts. MR-CBT also aims to give the patient as much autonomy as possible; it is not necessary for the patient to report the memories on which they are working. The basic sequence consists of a process of reciprocal inhibition, which starts by establishing positive affect, before proceeding to process and activate a negative affect, and finally generating a positive future-oriented affect.

Empirically, MR-CBT was tested by Högberg and Hällström (Citation2018) on 27 adolescents with depressive symptoms: 15 participants underwent MR-CBT, and the remaining 12 received TAU. Results showed a significant improvement in the levels of depression and well-being in both groups, with no differences between groups. However, there was a significant reduction in the frequency of suicidal events in the MR-CBT group, but not in the TAU group. Authors argue that this difference may be due to the fact that MR-CBT is optimal in addressing suicide risk; MR-CBT focuses on solving emotional and behavioural problems, which have been identified as major risk factors for suicide in adolescents.

In summary, results indicate that memory reconsolidation-based treatments should be further explored in the endeavour to prevent suicidality. However, although the results obtained are encouraging, more research is still needed to confirm that MR-CBT is useful for adolescents with depression as well as to expand its application to improve emotional regulation in other clinical populations.

Positive Visual Reframing (PVR)

PVR (Ruppert & Eiroa-Orosa, Citation2018) is an emotional regulation technique utilising drawing strategies. PVR is applied individually in a single session. Methodologically, participants use pencil and paper to create an image, doodle, or diagram that represents a negative experience or challenge. Then, participants try to change the narrative of the image in a positive manner by drawing over the initial pencil drawing with a black pen or felt-tip; they note/include any new perspectives in the new image. Once completed, participants erase unwanted traces of the original negative drawing, before repeating the new positive story in their mind and taking a few moments to connect with any new positive feelings. Finally, participants take a photograph of their final image and set it as the wallpaper of their mobile phone for two weeks.

Empirically, PVR was tested by Ruppert and Eiroa-Orosa (Citation2018) on 62 adults who were assigned randomly to an experimental (n=31) or control group (n=31). Participants in both groups drew a picture, doodle, or diagram of a negative experience. Next, participants of the experimental group received PVR, while participants in the control group drew triangles on a sheet of paper (neutral activity). Both groups took a photograph of the final image and saved it as their mobile phone wallpaper for two weeks. Results post-exercise revealed significant differences between groups in positive affect and the regulation of negative affect. However, these differences did not persist at the two-week follow-up.

Overall, PVR is an adaptive emotional regulatory strategy whose benefits do not depend on disposition or trait. Further, PVR demonstrates usefulness of visual interventions with a positive approach. Lastly, PVR represents empirical evidence on the viability of visual interventions to achieve adaptive emotional self-regulation.

Discussion

The current scoping review provides a description and examination of empirical evidence regarding effectiveness and utility of positive memory intervention techniques described in the scientific literature. This review demonstrates that several techniques have been proposed in recent years (the first being published in 2004), which is congruent with the growing research interest in positive memory or positive psychology interventions (Hendriks et al., Citation2019). Below, we outline trends in descriptive and empirical information for the reviewed intervention techniques.

Description of positive memory intervention techniques

In terms of number/duration of sessions, seven of reviewed intervention techniques spanned a short duration defined as one to four sessions; these include BMAC, PMET, PVR, Writing about a Peak Positive Experience, Positive Writing, and Sharing Positive Narratives with a Partner. In the case of Re-experiencing Pleasant Memories using Mental Imagery even though two sessions a day for a week are proposed, the duration of these sessions is 10 min which can be considered a short technique. Such intervention techniques may be highly versatile as they can be implemented separately, incorporated into existing treatment packages, or applied as supplements or augments to existing therapies. However, four reviewed interventions (COMET, PoMeT, MR-CBT, MEST and PPMT) represent stand-alone treatment protocols; they involve four-twelve weekly sessions that last at least 60 min. It should be noted that two of these four interventions target specific therapeutic changes (i.e., improved self-esteem increase [COMET and PoMeT], improved emotional regulation [MR-CBT]).

Regarding therapy modality, only two techniques propose a group application: MEST and COMET. It should be noted again that these two proposals focus on very specific objectives which could facilitate a group application. Although the protocols propose the application of these techniques in a group format, in all cases, studies have applied them using an individual format. For example, COMET was modified to be used as an individual format in three efficacy studies (Farahimanesh et al., Citation2020; Schneider et al., Citation2015; Staring et al., Citation2016). Finally, frequently applications of the techniques deviated from the original protocol in other aspects such as the number of sessions to adapt to needs of diverse populations and contexts.

Regarding number of positive memories used in each technique, there was a wide range from one to >10 (most focused on one-three positive memories). Notably, many studies did not report the number of positive memories for their corresponding techniques (eight of the 12 techniques). Thus, we cannot compare the possible differential effects of retrieving different number of positive memories and cannot comment on the optimal number of positive memories that should be retrieved for beneficial impacts. Even more, most studies did not assess or therapeutically utilise characteristics of retrieved memories, such as the centrality in the person's life or the emotional value associated with them; this is an avenue for future research to improve intervention effects.

A common element to most intervention techniques was the importance of participants engaging with and completing tasks and procedures accurately to obtain desired effects. For instance, in MEST, participants have to perform between-session tasks to make progress; in PVR, participants need to keep their created new image as their mobile phone wallpaper for two weeks; in Sharing Positive Narratives with a Partner, participants are primarily responsible for carrying out the tasks on a daily basis following provided instructions; or in PPMT, patients must listen to the recording of the positive memory narrative as a homework assignment between sessions. Consequently, it is essential for participants to receive psychoeducation on the rationale and importance of their role in the successful application of the different procedures, and for clinical providers to implement strategies to reduce non-compliance and dropout. This being said, although several reviewed techniques require a high level of compliance, participants may be less aversive to working with positive memories (vs. traumatic memories for example) as indicated by clinicians and patients in preliminary studies (e.g., Contractor et al., Citation2020a).

On the other hand, one of the most heterogeneous aspects of the reviewed intervention techniques was therapeutic objectives which ranged from specific (e.g., improve self-esteem [COMET and PoMeT], reduce sadness [PMET]) to broader goals. Subsequently, clinicians have a diversity of techniques to choose from to address unique needs of clients. However, it would be useful to consider the similarities between their therapeutic targets to examine the type and shared similarity of action mechanisms underlying the different positive memory techniques.

Empirical evidence of positive memory intervention techniques

The results need to be considered in the light of variations in sample characteristics, methodology, and indices of rigour across examined studies. This review seems to indicate variability in the quality and quantity of research on efficacy/effectiveness of the selected techniques, which is fundamental in informing evidence-based clinical practice (Gálvez-Lara et al., Citation2019).

Half of the reviewed positive memory intervention techniques (6 out of 12) have been empirically examined in one study each (i.e., Re-experiencing Pleasant Memories Using Mental Imagery, PMET, PoMeT, MR-CBT, PVR, and Sharing Positive Narratives with a Partner), while two techniques have been empirically examined in two studies each (i.e., Writing about a Peak Positive Experience and Positive Writing). By contrast, three of the reviewed techniques (BMAC, MEST and COMET) stand out for having been empirically examined in four, nine and 12 studies, respectively.

Most of the reviewed studies included modest sample sizes (n<100) and most (n=15) did not perform follow-up evaluations; when conducted, follow-ups were primarily of short duration ranging from two weeks to six months (e.g., COMET; Korrelboom et al., Citation2012). Notably, in the case of MEST, seven of its nine studies included follow-ups of at least two months. Furthermore, many of the studies employed non-standardised measurement instruments (e.g., the ad hoc scale used in the Re-experiencing Pleasant Memories Intervention). The review also indicated that COMET studies had methodological soundness since five of the studies include a control group consisting of TAU, four use an active comparison group (e.g., EMDR or MEST) and one uses a wait-list control group; COMET has been tested with diverse clinical populations; and most studies demonstrated significant results of improved depression symptoms and self-esteem. These factors support the choice of COMET as a positive memory technique to be implemented with a comparative degree of success. Also, most positive memory intervention techniques (n=6; primarily those that employ writing as a therapeutic strategy) have been only tested in non-clinical populations. This aspect is consistent with current approaches that support the development of proposals that can be used with the general population to improve well-being and quality of life (Auyeung & Mo, Citation2019).

The most common health effects reported across the reviewed studies (25 studies) are improved positive affect and less depression, which is consistent with previous research suggesting that positive psychology interventions effectively address anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g., Chaves et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, the reviewed studies demonstrated contradictory results for certain health outcomes as a result of the respective positive memory intervention, such as negative affect: four studies showed no effect on negative affect, whereas 11 studies indicated a decrease in negative affect. These mixed results could be related to differences in types and characteristics of samples or nature of the procedure across studies. Moreover, the reviewed studies also provided some evidence for effects of positive memory intervention techniques on decreased frequency of suicidal thoughts, improved self-esteem and capacity for emotional regulation, and improved physical and emotional health. Future research would benefit from examining if these results are specific to particular techniques. In this regard, a recent meta-analysis suggests that MEST is optimal for improving autobiographical memory specificity (Ahmadi Forooshani et al., Citation2020), an aspect that seems specific to this technique. Furthermore, the inclusion of certain elements, such as sharing positive emotions with other individuals, may increase health benefits of the different techniques in a transversal manner, as suggested by Lambert et al. (Citation2013). Finally, several studies (e.g., Panagioti et al., Citation2012) found transient and temporary impacts of positive memory techniques since their effects diminished at follow-up; future research should investigate technique modifications to sustain intervention impacts.

Implications, limitations, and future research

Several clinical implications can be derived from this review. First, this review may serve as a quick reference guide to help professionals’ access descriptions and information on empirical evidence of positive memory techniques, improving their therapeutic arsenal to enhance well-being and therapeutic outcomes in their patients. Relatedly, this review enables clinicians to select specific techniques based on the knowledge provided by each corresponding study. Second, COMET seems to be the most widely researched and thus the one with the most amount of empirical evidence. This may be a good starting point for clinicians who wish to incorporate positive memory techniques into existing treatment strategies. Nonetheless, MEST and BMAC also had sound and promising empirical findings. Third, this review may act as a stimulus to promote the implementation of the models that support the incorporation of positive memory techniques into conventional treatments (e.g., Contractor et al., Citation2018). Indeed, a recent review on PTSD interventions suggest that ∼50% of existing PTSD interventions incorporate positive memories in some manner (Contractor et al., Citation2020c). Finally, despite the transient effects associated with many of the reviewed techniques, the perceived non-aversive and pleasant nature of these interventions could facilitate the therapeutic process and the adherence, and strengthen the therapeutic alliance, which would optimise health benefits.

Findings of this review need to be considered in light of several limitations beyond the methodological considerations outlined earlier. First, the review only included studies published in English and Spanish, and most protocols were developed and tested in Western countries (e.g., Tarrier, Citation2010); thus, applicability of review findings to protocols in other languages and cultures need to be determined. Second, unpublished studies were not considered which could indicate bias in the search strategy and outlined findings. Third, it is possible that the search terms may have been too narrow, and although we conducted secondary searches, we may have missed some relevant papers in the screening phase. Fourth, the proposed classification of the techniques could convey some overlap and should be considered with caution. For instance, PPMT addresses improving one’s ability to retrieve positive memories as well the content of those memories (i.e., could be included in two classification blocks). Finally, given that this was a scoping review, it would be helpful to conduct a meta-analysis summarising statistical estimates of effects. Despite these issues, the current scoping review is the first to examine and summarise the existing knowledge base on positive memory intervention techniques addressing broader psychopathology and clinical correlates. All in all, this review may serve a useful reference tool to help clinicians choose a suitable technique according to evidence-based criteria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmadi Forooshani, S., Murray, K., Izadikhah, Z., & Khawaja, N. (2020). Identifying the most effective strategies for improving autobiographical memory specificity and its implications for mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(2), 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10061-8

- Allen, S. F., Wetherell, M. A., & Smith, M. A. (2020). Online writing about positive life experiences reduces depression and perceived stress reactivity in socially inhibited individuals. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112697

- Arditte Hall, K. A., De Raedt, R., Timpano, K. R., & Joormann, J. (2017). Positive memory enhancement training for individuals with major depressive disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1364291

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Askelund, A. D., Schweizer, S., Goodyer, I. M., & van Harmelen, A. L. (2019). Positive memory specificity is associated with reduced vulnerability to depression. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1101/329409

- Auyeung, L., & Mo, P. K. H. (2019). The efficacy and mechanism of online positive psychological intervention (PPI) on improving well-being among Chinese university students: A pilot study of the best possible self (BPS) intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(8), 2525–2550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0054-4

- Baikie, K. A., Geerligs, L., & Wilhelm, K. (2012). Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: An online randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.032

- Banducci, A. N., Contractor, A. A., Weiss, N. H., & Dranger, P. (2020). Do positive memory characteristics relate to reckless behaviors? An exploratory study in a treatment-seeking traumatized sample. Memory, 28(7), 950–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1788603

- Barry, T. J., Sze, W. Y., & Raes, F. (2019). A meta-analysis and systematic review of memory specificity training (MeST) in the treatment of emotional disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.02.001

- Bryant, F. B., Smart, C. M., & King, S. P. (2005). Using the past to enhance the present: Boosting happiness through positive reminiscence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 227–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-3889-4

- Bryant, R. A., Sutherland, K., & Guthrie, R. M. (2007). Autobiographical memory in the development, maintenance, and resolution of posttraumatic stress disorder after trauma. In D. A. Einstein (Ed.), Innovations and advances (pp. 235–246). Academic Press.

- Burton, C. M., & King, L. A. (2004). The health benefits of writing about intensely positive experiences. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00058-8

- Burton, C. M., & King, L. A. (2009). The health benefits of writing about positive experiences: The role of broadened cognition. Psychology & Health, 24(8), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440801989946

- Chaves, C., Lopez-Gomez, I., Hervas, G., & Vazquez, C. (2019). The integrative positive psychological intervention for depression (IPPI-D). Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 49(3), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-018-9412-0

- Contractor, A. A., Banducci, A. N., Dolan, M., Keegan, F., & Weiss, N. H. (2019). Relation of positive memory recall count and accessibility with posttrauma mental health. Memory, 27(8), 1130–1143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1628994

- Contractor, A. A., Banducci, A. N., Jin, L., Keegan, F. S., & Weiss, N. H. (2020b). Effects of processing positive memories on posttrauma mental health: A preliminary study in a non-clinical student sample. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 66(February 2019), 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2019.101516

- Contractor, A. A., Banducci, A. N., & Weiss, N. H. (in press). Critical considerations for the positive memory-posttraumatic stress disorder model. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23142

- Contractor, A. A., Brown, L. A., Caldas, S. V., Banducci, A. N., Taylor, D. J., Armour, C., & Shea, M. T. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and positive memories: Clinical considerations. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58(December 2017), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.06.007

- Contractor, A. A., Weiss, N. H., Forkus, S. R., & Keegan, F. (2020c). Positive internal experiences in PTSD interventions: A critical review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020925784

- Contractor, A. A., Weiss, N. H., & Shea, M. T. (2020a). Processing of positive memories technique (PPMT) for posttraumatic stress disorder: A primer. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000239

- Crespo, M., & Fernández-Lansac, V. (2016). Memory and narrative of traumatic events: A literature review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000041

- Dalgleish, T., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2014). Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(11), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.06.010

- Eigenhuis, E., Seldenrijk, A., van Schaik, A., Raes, F., & van Oppen, P. (2017). Feasibility and effectiveness of memory specificity training in depressed outpatients: A pilot study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1995

- Ekkers, W., Korrelboom, K., Huijbrechts, I., Smits, N., Cuijpers, P., & van der Gaag, M. (2011). Competitive memory training for treating depression and rumination in depressed older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(10), 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.010

- Emsaki, G., NeshatDoost, H. T., Tavakoli, M., & Barekatain, M. (2017). Memory specificity training can improve working and prospective memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 11(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642016dn11-030007

- Farahimanesh, S., Moradi, A., & Sadeghi, M. (2021). Autobiographical memory bias in cancer-related post traumatic stress disorder and the effectiveness of competitive memory training. Current Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01648-0

- Farahimanesh, S., Moradi, A., Sadeghi, M., & Jobson, L. (2020). Comparing the efficacy of competitive memory training (COMET) and memory specificity training (MEST) on posttraumatic stress disorder among newly diagnosed cancer patients. Cognitive Therapy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10175-4

- Fernández-Lansac, V., & Crespo, M. (2015). Narrative length and speech rate in battered women. Plos One, 10(11), e0142651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142651

- Gálvez-Lara, M., Corpas, J., Velasco, J., & Moriana, J. A. (2019). Knowledge and use of evidence-based psychological treatments in clinical practice. Clínica y Salud, 30(3), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2019a12

- Hallford, D. J., Austin, D. W., Takano, K., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., & Raes, F. (2021). Computerized memory specificity training (c-MeST) for major depression: A randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 136, 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103783

- Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2019). How weird are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

- Högberg, G., & Hällström, T. (2018). Mood regulation focused CBT based on memory reconsolidation, reduced suicidal ideation and depression in youth in a randomised controlled study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050921

- Holden, N., Kelly, J., Welford, M., & Taylor, P. J. (2017). Emotional response to a therapeutic technique: The social broad minded affective coping. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12095

- Johnson, J., Gooding, P. A., Wood, A. M., Fair, K. L., & Tarrier, N. (2012). A therapeutic tool for boosting mood: The broad-minded affective coping procedure (BMAC). Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9453-8

- Joormann, J., Siemer, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2007). Mood regulation in depression: Differential effects of distraction and recall of happy memories on sad mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.484

- Korrelboom, C. W. (2000). Versterking van het zelfbeeld bij patiënten met persoonlijkheidspathologie: “hot cognitions” versus “cold cognitions”. (Strengthening self-esteem in patients with personality disorders: Hot cognitions versus cold cognitions). Directieve Therapie, 20(3), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03060241

- Korrelboom, K., de Jong, M., Huijbrechts, I., & Daansen, P. (2009b). Competitive memory training (COMET) for treating low self-esteem in patients with eating disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 974–980. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016742

- Korrelboom, K., Maarsingh, M., & Huijbrechts, I. (2012). Competitive memory training (COMET) for treating low self-esteem in patients with depressive disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 29(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20921

- Korrelboom, K., Peeters, S., Blom, S., & Huijbrechts, I. (2014). Competitive memory training (COMET) for panic and applied relaxation (AR) are equally effective in the treatment of panic in panic-disordered patients. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 44(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-013-9259-3

- Korrelboom, K., van der Gaag, M., Hendriks, V. M., Huijbrechts, I., & Berretty, E. W. (2008). Treating obsessions with competitive memory training: A pilot study. The Behavior Therapist, 31(2), 29–35. Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-17791-001

- Korrelboom, K., van der Weele, K., Gjaltema, M., & Hoogstraten, C. (2009a). Competitive memory training for treating low self-esteem: A pilot study in a routine clinical setting. The Behavior Therapist, 32(1), 3–8. Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-16232-002

- Lambert, N. M., Gwinn, A. M., Baumeister, R. F., Strachman, A., Washburn, I. J., Gable, S. L., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). A boost of positive affect: The perks of sharing positive experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407512449400

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Moradi, A. R., Moshirpanahi, S., Parhon, H., Mirzaei, J., Dalgleish, T., & Jobson, L. (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of memory specificity training in improving symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.002

- Mote, J., & Kring, A. M. (2019). Toward an understanding of incongruent affect in people with schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 207(5), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000983

- Neshat-Doost, H. T., Dalgleish, T., Yule, W., Kalantari, M., Ahmadi, S. J., Dyregrov, A., & Jobson, L. (2013). Enhancing autobiographical memory specificity through cognitive training. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702612454613

- Panagioti, M., Gooding, P. A., & Tarrier, N. (2012). An empirical investigation of the effectiveness of the broad-minded affective coping procedure (BMAC) to boost mood among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(10), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.005

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1993). Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31(6), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4

- Raes, F., Williams, J. M. G., & Hermans, D. (2009). Reducing cognitive vulnerability to depression: A preliminary investigation of memory specificity training (MEST) in inpatients with depressive symptomatology. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.03.001

- Romano, M., Ma, R., Moscovitch, M., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2020). Autobiographical memory bias. In J. S. Abramowitz, & S. M. Blakey (Eds.), Clinical handbook of fear and anxiety: Maintenance processes and treatment mechanisms (pp. 183–202). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000150-011

- Ruppert, J. C., & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (2018). Positive visual reframing: A randomised controlled trial using drawn visual imagery to defuse the intensity of negative experiences and regulate emotions in healthy adults. Anales de Psicología, 34(2), 368. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.2.286191

- Sadat Zia, M., Afkhami, E., Taher Neshat-Doost, H., Tavakoli, M., Mehrabi Kooshki, H. A., & Jobson, L. (2021). A brief clinical report documenting a novel therapeutic technique (MEmory specificity training, MEST) for depression: A summary of two pilot randomized controlled trials. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 49(1), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000417

- Schneider, B. C., Wittekind, C. E., Talhof, A., Korrelboom, K., & Moritz, S. (2015). Competitive memory training (COMET) for OCD: A self-treatment approach to obsessions. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.981758

- Speer, M., & Delgado, M. (2017). Reminiscing about positive memories buffers acute stress responses. Nature Human Behaviour, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0093

- Staring, A. B. P., van den Berg, D. P. G., Cath, D. C., Schoorl, M., Engelhard, I. M., & Korrelboom, C. W. (2016). Self-esteem treatment in anxiety: A randomized controlled crossover trial of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) versus competitive memory training (COMET) in patients with anxiety disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 82, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.04.002

- Steel, C., Korrelboom, K., Fazil Baksh, M., Kingdon, D., Simon, J., Wykes, T., Phiri, P., & van der Gaag, M. (2020). Positive memory training for the treatment of depression in schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 135, 103734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2020.103734

- Steel, C., van der Gaag, M., Korrelboom, K., Simon, J., Phiri, P., Baksh, M. F., Wykes, T., Rose, D., Rose, S., Hardcastle, M., Enright, S., Evans, G., & Kingdon, D. (2015). A randomised controlled trial of positive memory training for the treatment of depression within schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0453-6

- Tarrier, N. (2010). Broad minded affective coping (BMAC): a “positive” CBT approach to facilitating positive emotions. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.1.64

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- van der Gaag, M., van Oosterhout, B., Daalman, K., Sommer, I. E., & Korrelboom, K. (2012). Initial evaluation of the effects of competitive memory training (COMET) on depression in schizophrenia-spectrum patients with persistent auditory verbal hallucinations: A randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02025.x

- van Vreeswijk, M. F., Spinhoven, P., Zedlitz, A. M. E., & Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. (2020). Mixed results of a pilot RCT of time-limited schema mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and competitive memory therapy plus treatment as usual for personality disorders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(3), 170–180. doi10.1037/per0000361

- Waugh, C. E. (2020). The roles of positive emotion in the regulation of emotional responses to negative events. Emotion, 20(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000625

- Werner-Seidler, A., Hitchcock, C., Bevan, A., McKinnon, A., Gillard, J., Dahm, T., Chadwick, I., Panesar, I., Breakwell, L., Mueller, V., Rodrigues, E., Rees, C., Gormley, S., Schweizer, S., Watson, P., Raes, F., Jobson, L., & Dalgleish, T. (2018). A cluster randomized controlled platform trial comparing group memory specificity training (MEST) to group psychoeducation and supportive counselling (PSC) in the treatment of recurrent depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 105, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.03.004

- Werner-Seidler, A., & Moulds, M. L. (2011). Autobiographical memory characteristics in depression vulnerability: Formerly depressed individuals recall less vivid positive memories. Cognition & Emotion, 25(6), 1087–1103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.531007

- Williams, J. M. G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. https://doi.org/:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122

- Williams, H. L., Conway, M. A., & Cohen, G. (2008). Autobiographical memory. In G. Cohen, & M. A. Conway (Eds.), Memory in the real world (3rd ed.) (pp. 21–90). Psychology Press.