ABSTRACT

Frederic Bartlett’s schema theory is still widely misunderstood as claiming that remembering is inevitably unreliable. However, according to the logic of his schema theory, remembering should, in relation to certain kinds of material, be relatively reliable. In this study we examined whether a “well-worn” urban myth (the Vanishing Hitchhiker) could be exempt from the fate of other material used in Bartlett’s own research on serial reproduction. Supporting Bartlett’s ideas, we found that recall of the Hitchhiker story was better (if not perfect) over a series of five reproductions than recall of the classic War of the Ghosts. Recall was also better for a strict (as opposed to a lenient) audience, in line with another prediction from Bartlett’s social theory of remembering. Notwithstanding this, we conclude with some critical remarks on the serial reproduction method as an approach to cultural memory.

Frederic Bartlett, the famous Cambridge psychologist, claimed that he adopted the method of serial reproduction thanks to a suggestion by his friend Norbert Wiener, then also based at Cambridge:

One day, when I had been talking about my experiments, and the use I was making of sequences in a study of conventionalization regarded as a process more or less continuous in time, he said: “Couldn’t you do something with ‘Russian Scandal,’ as we used to call it? That was what led to the method which I later called ‘The Method of Serial Reproduction’ ” … (Bartlett, Citation1958, p. 144.)

The method of serial reproduction is not simply an experimental procedure but since the time of Pitt-Rivers has also been, in effect, a theory of cultural “transmission” – the passive, unilateral reception by one generation of traditional forms and practices from earlier ones (e.g., Mesoudi & Whiten, Citation2008, p. 3491).

In addition to his unreliable recall of the origin of the method of serial reproduction, Bartlett’s account of the contemporary work on memory was also rather selective, as American reviewers of his book, Remembering (Citation1932) complained (e.g., Jenkins, Citation1935; see also Davis, Citation2018; and Kintsch, Citation1995).

To add to all this, Bartlett’s account of the implications of his schema theory is also misleading. The claim, widely attributed to Bartlett, has been that remembering is always more or less unreliable – errors are the rule rather than the exception (and, in all fairness, one can of course find quotes in the book to support such a narrow interpretation of Bartlett’s position). Yet the logical implications of Bartlett’s schema or constructive theory of remembering are fundamentally different from the “textbook” accounts (a full exposition is beyond the scope of this article; see Ost & Costall’s, Citation2002, detailed analysis). Distortions should occur to the extent that necessary corrections to the schema fail to be made, are forgotten, or come to be exaggerated (see Woodworth, Citation1938, p. 74 on “schema and correction”). On the other hand, remembering should, however, also be relatively reliable depending upon, among other factors, the extent to which the material to be remembered is compatible with available schemas.

… though the constructive character of remembering can give rise to distortion under certain circumstances, construction is compatible with the accuracy of memory. Though this point is simple and should not be controversial, it is often overlooked … . (Michaelian, Citation2016, p. 143. Emphasis added. See also, Brown & Reavey, Citation2015; Michaelian & Sutton, Citation2017; Schacter & Addis, Citation2007; Wagoner, Citation2017)

So, the implications of Bartlett’s schema theory – and indeed such theories in general – are clear and simple.

When the material to be reproduced does not fit in easily with available schema, transformation should be the rule.

When the material is relatively compatible with available schemas, transformation should be much less extreme.

Bartlett, even in his early work on “folk-lore” added the following claim, central to the point of our present study:

When a story is passed on from one person to another, each man repeating, as he imagines, what he has heard from the last narrator, it undergoes many successive changes before at length it arrives at a relatively fixed form in which it may become current throughout a whole community. (Bartlett, Citation1920, p. 30).

.. the story as presented belonged to a level of culture and a social environment exceedingly different from those of my subjects. Hence it seemed likely to afford good material for persistent transformation. (Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 64; emphasis added)

In fact, Bartlett did also include more familiar material in his research, and (contrary to his true theory) obtained very similar results, as in the serial recall of a cricket match, “Fine batting at Lord’s” (the Mecca of English cricket). Here is Bartlett’s bemused verdict:

It will be seen at once that in this series almost every possible error has been made. Yet, on general grounds, this is precisely the kind of material that might have been expected to yield extremely accurate results. Practically all the subjects had been Public School boys, were keenly interested in sport, and, as indeed their versions show, acquainted with the particular technicalities of a cricket report. Most of them would find the Sports page in a daily newspaper their first interest; and yet it seems clear enough that this sort of material, however interesting it may be in itself, makes a very fleeting impression in general. (Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 150; emphasis added)

Under the conditions of the present experiment all the stories tend to be shorn of their individualizing features, the descriptive passages lose more of the peculiarities of style and matter that they may possess, and the arguments tend to be reduced to a bald expression of conventional opinion. (Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 173.)

So, to repeat, according to the logic of Bartlett’s schema theory, “precisely the kind of material that might [be] expected to yield extremely accurate results” should indeed produce relatively accurate results. Whether that proves to be the case is, of course, a different matter, which brings us to the point of our present study.

How do people recall material that has survived the test of time for being especially memorable, namely “urban myths” (or “urban legends”)? Over a good deal of reproduction, these stories have been subject to the selective process of either being forgotten or retained, and those that survive should, by definition, be more memorable or “catchable.” Analysis of the diffusion of such stories throughout popular culture has found that, although the details vary considerably in the retelling, a stable core persists (see Brunvand, Citation1983 for an excellent analysisFootnote2; see also Beardsley & Hankey, Citation1942; Rubin, Citation1995).

Therefore, our first purpose in this study has been to examine whether, in keeping with the fundamental logic of Bartlett’s schema theory, such relatively fixed forms (Bartlett, Citation1920, p. 30) are relatively resistant to transformation when compared to the very strange The War of the Ghosts.

Our second purpose has been to test a sometimes overlooked, further element of Bartlett’s theory: that remembering is not just an individual achievement, but is very much a function of the relationship between the “audience” and the “narrator”:

… the most important things to consider are the social position of the narrator in his own group, and his relation to the group from which the audience is drawn. If the latter group are submissive, inferior, he is confident, and his exaggerations are markedly along the lines of the preferred tendencies of his own group. If the alien audience is superior, masterly, dominating, they may force the narrator into the irrelevant, recapitulatory method until, or unless he, wittingly or unwittingly, appreciates their own preferred bias (Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 266).

Thus, according to Bartlett, the degree of transformation should also be a function of who or what the material is being remembered for (Edwards & Middleton, Citation1986; Edwards & Middleton, Citation1987; Dudukovic et al., Citation2004; Gauld & Stephenson, Citation1967; Hyman, Citation1994; Marsh and Tversky, Citation2004).

In the present study this social aspect of remembering was manipulated by instructing participants to reproduce the stories as if they were either recalling them for a police officer (“strict audience”), or for a friend (“lenient audience”) who had not heard the story before. The present study therefore not only compares two kinds of material (memorable vs. weird) but also two conditions of recall (strict vs lenient).

Method

Using the serial reproduction method, we studied the “fate” of two very different (as established in a pilot study) stories. Both stories were passed down chains of five participants who each read and then reproduced them, for either a strict or lenient imagined audience. We expected the fixed-form story (The Vanishing Hitchhiker) to undergo less change over successive reproductions than Bartlett’s classic weird story (The War of the Ghosts). Following Bartlett’s intuitions, we also expected better recall for a strict imagined audience.

Pilot study: selection and pre-testing of stimulus materials

In the present experiment The Vanishing Hitchhiker (Brunvand, Citation1983) was chosen as the “meme-like” story because it contained a similar number of details and themes (362 words, 123 details and 19 themes) to The War of the Ghosts (328 words, 118 details and 22 themes) (see Coding section below; and see Pace, Boren & Peterson, Citation1975). Brunvand (Citation1983) traced this story back as far as the 1870s. Piloting established that The Vanishing Hitchhiker was indeed perceived as more “familiar” to the participants. Nine participants (5 male, 4 female, M = 38.88 yrs, SD = 5.45 yrs) were asked to rate the two stories (presentation of which was counterbalanced) on five dimensions (the familiarity of the setting, the logical structure, the clarity of the structure, how understandable the events in the story were, and how conventional the language was). Each dimension was rated on a seven-point scale (original anchors: 7 = low; 1 = high; reversed in for more intuitive interpretation). provides descriptive statistics, t-test results and effect sizes and shows that the two stories differed significantly, in the expected direction, on each of the five dimensions, with large to very large effect sizes. Indeed, the averages of the familiarity ratings (The War of the Ghosts = 2.65; The Vanishing Hitchhiker = 5.16) differed by almost half the scale range (1–7). In short, the two stories met the requirements for use in the main experiment.

Table 1. Pilot study: Ratings of different dimensions of familiarity for War of the Ghosts and The Vanishing Hitchhiker.

Main experiment

Participants: An opportunity sample of 80 participants was recruited from undergraduate students who signed up for the research as part of a first year B.Sc. Psychology course. They received 1 credit (a sixth of the credit they were required to obtain) each for taking part in this experiment. The sample consisted of 10 males and 70 females, between the ages of 18 and 48 years old (M = 21.30, SD = 6.28).

Design: The experiment used a 2 (Story: The War of the Ghosts; The Vanishing Hitchhiker) x 2 (Audience instructions: strict; lenient) x 5 (Serial reproduction chain position: first; second; third; fourth; fifth) design. Story was manipulated within subjects (i.e., each participants received and reproduced both The Vanishing Hitchhiker and The War of the Ghosts). Serial reproduction chain position was a between-subjects variable (naturally), and Audience instructions were manipulated between chains (and thereby between subjects; i.e., all five participants in a reproduction chain received either Lenient or Strict audience instructions). Specifically, Chains 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 received Lenient instructions, and Chains 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 received Strict instructions. The dependent variables were the proportion of words, details, and themes that the participants included in their written reproductions.

To limit possible order effects, the order of presentation of the stories was alternated within chains (i.e., the presentation order for the first participant in the chain was reversed for the second, then again for the third, etc.), and the starting order for the first participant was counterbalanced between chains (orthogonal to the Audience instructions manipulation to avoid a confound).

Materials: Typed copies of the two stories (The Vanishing Hitchhiker and The War of the Ghosts; see Appendix 1). Blank paper and a pen were also provided for participants to write down their reproductions.

Procedure: There were 16 serial reproduction chains, each consisting of five participants, along which the stories were passed. Participants were given the original story (either The War of the Ghosts or The Vanishing Hitchhiker counterbalanced across conditions) to read through once at their normal reading speed. When the participant had done this, the story was removed, and they were then provided with a blank piece of paper and a pen and given either Lenient or Strict instructions for their recall (see Appendix 2). When the participant had written as much of the story as they could remember they were asked to do the same with the second story. The participant was then debriefed, thanked for their time and given the opportunity to ask any questions.

The first participant's reproduction was then typed up in preparation for the next participant in the chain. Spelling mistakes and grammatical errors were left in the typed version of the reproduction. The second participant was taken through the same procedure but was given the previous participant’s reproductions of both stories to read and reproduce (in counterbalanced order, see above). This procedure was the same for all five participants in each of the sixteen chains, resulting in a total of 80 reproductions of each story.

Coding: There is considerable debate as to what “counts” as accuracy in remembering (Banaji & Crowder, Citation1989; Erdelyi, Citation1998; Koriat & Goldsmith, Citation1996; Lynn & McConkey, Citation1998; Neisser & Hyman, Citation2000; Edwards, Middleton & Potter, Citation1992 and commentaries) as well as how to score the “accuracy” of prose material (Gauld & Stephenson, Citation1967; Roediger, Bergman & Meade, Citation2000). For example, in his studies of hypermnesia in Bartlettian-type reproductions, Erdelyi (Citation1998) suggested that the most straightforward (if “wooden-headed”, p. 158) approach is simply to count the number of words used in each reproduction, including “a” and “the” (see also Wynn & Logie, Citation1998). This was achieved using the “word count” function in the word processing package that was used to type up each participant’s reproductions.

There are (at least) a further two ways in which a story can be remembered “accurately” (see Hyman, Citation1999). The first is the faithful reproduction of specific details. The second is the preservation of the overall “gist” of the story, even after the specific details are lost. This distinction between detail and gist accords with fuzzy-trace theories of remembering, in which specific detail level representations decay over time leaving only a general “gist” level representation (for a fuller discussion see Brainerd & Reyna, Citation1990; Brainerd & Reyna, Citation2005; Hyman, Citation1999; Neisser, Citation1981).

In fact, counting words, details, and gist-level themes has been used to a greater or lesser extent in previous research (e.g., Gauld & Stephenson, Citation1967; Pace et al., Citation1975; Kurke, Weick & Ravlin, Citation1989; Roediger et al., Citation2000). Therefore, we employed an adapted version of the coding scheme devised by Pace et al., (Citation1975) and used by Kurke et al., (Citation1989). This coding scheme breaks each story down into specific information unit details, and one point is assigned for each such detail included in a reproduction, even if slightly altered (in tense or by substitution of synonyms). For example, “one”, “night”, “two”, “young” and “men” would all score a total of five points. Half points are awarded for terms that were significantly altered but maintained close lexical relations to the original (e.g., “day” instead of “night”, “boys’ instead of “men”). Secondly, this coding scheme breaks each story down into gist level “themes.” An example of a theme would be – “does the reproduction mention a fishing or hunting trip?” (Pace et al., Citation1975; Kurke et al., Citation1989). There are no half points, and one point is scored simply if the reproduction includes this general theme (e.g., “some men went out to fish” would score one point). In order to control for slight differences in the number of words, details and themes in the two stories, these raw scores were converted into proportions for analysis.

Inter-rater reliability: A second rater (JO) independently scored twelve percent of the reproductions. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the percentage of agreement method and was over 98%. Any differences between the two raters were resolved by discussion and the first rater’s (JU) codes were used for analysis.

Results

The data set underlying our analyses is available at https://osf.io/gptkz/. A 2 (Story: The War of the Ghosts; The Vanishing Hitchhiker) x 2 (Audience instructions: strict; lenient) x 5 (Position in serial reproduction chain: first; second; third; fourth; fifth) MANOVA was conducted on the proportion of words, details and themes included in the reproduction. There were multivariate effects of story (Wilks’ Lambda = .70, F3,68 = 9.67, p < .0005, partial η² = .30), audience instructions (Wilks’ Lambda = .62, F3,68 = 13.91, p < .0005, partial η² = .38), and place in chain (Wilks’ Lambda = .16, F12,180.2 = 14.93, p < .0005, partial η² = .46) on the proportion of words, details and themes included in participants’ reproductions. Moreover, there were significant multivariate interactions between audience instruction and position in the serial reproduction chain (Wilks’ Lambda = .67, F12,180.2 = 2.47, p < .01, partial η² = .13) as well as between audience instruction and story (Wilks’ Lambda = .81, F3,68 = 5.40, p < .005, partial η² = .19). The univariate effects are now reported.

The effects of a “fixed form” or “weird” story

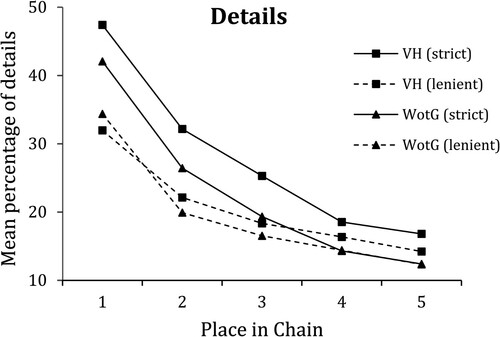

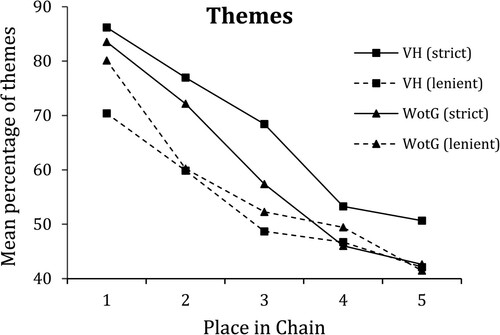

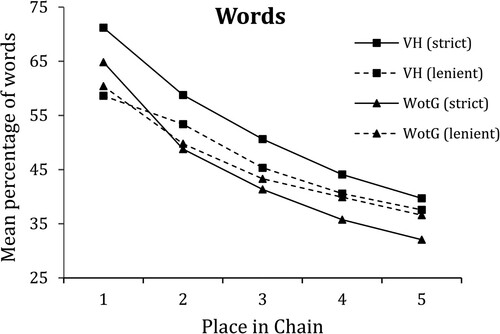

As shown in , participants used proportionally more words in their reproductions of The Vanishing Hitchhiker (M = 49.99, SE = 1.72) than The War of the Ghosts (M = 45.27, SE = 1.69) (F1,70 = 17.23, p < .0005, partial η² = .20). Moreover, (see ), the proportion of details included in participants’ reproductions was significantly higher for The Vanishing Hitchhiker (M = 24.32, SE = 0.70) than The War of the Ghosts (M = 21.21, SE = 0.72) (F1,70 = 21.47, p < .0005, partial η² = .23). As shown in , participants did not recall significantly more of the themes from The Vanishing Hitchhiker than from The War of the Ghosts (F < 2).

Figure 1. Mean percentage of words recalled as a function of story, audience instruction and position in serial reproduction chain (VH = Vanishing Hitchhiker, WotG = War of the Ghosts).

The effects of participants’ position in the serial reproduction chain

As shown in , there was a significant effect of place in chain on the proportion of words participants included in their reproductions (F4,70 = 9.15, p < .0005, partial η² = .34). Scheffé post hoc contrasts indicated that the proportion of words included in the first reproduction was not significantly higher than the second reproduction but was higher than all subsequent reproductions. Further, the proportion of words included in the second reproduction was significantly higher than in the fifth reproduction. The proportion of words included in the third, fourth and fifth reproductions did not differ significantly.

As shown in , the participants’ place in the chain of reproductions also had an effect on the proportion of details (F4,70 = 50.83, p < .0005, partial η² = .74). Scheffé post hoc contrasts indicated that the proportion of details included in the first reproduction was significantly higher than in all subsequent reproductions. In addition, the proportion of details included in the second reproduction was significantly higher than in the fourth and fifth reproductions. The proportions of details in the third, fourth and fifth reproductions did not differ significantly.

There was also a significant effect of place in chain of reproductions on the proportion of themes recalled (F4,70 = 28.15, p < .0005, partial η² = .62) (see ). Scheffé post hoc contrasts indicated that the proportion of themes included in the first reproduction was significantly higher than in all subsequent reproductions. Also, the proportion of themes was significantly higher in the second than in the fourth and fifth reproductions, and again higher in the third than in the fifth reproduction. No other serial positions differed significantly.

The effects of audience instructions

As shown in , there was no effect of audience instructions on the number of words participants used in their reproductions (F < 1). The proportion of details recalled was higher when participants were asked to reproduce the story for a strict (M = 25.48, SE = 0.89) compared to a lenient audience (M = 20.06, SE = 0.89) (F1,70 = 18.62, p < .0005, partial η² = .21) (see ). Further (see ), participants included proportionally more of the themes of the story when reproducing them for a strict audience (M = 63.72, SE = 1.73) than a lenient audience (M = 55.13, SE = 1.73) (F1,70 = 12.41, p < .001, partial η² = .15).

The interaction between audience instructions and position in serial reproduction chain

As shown in , the significant interaction between audience and position in the serial reproduction chain indicated that, for the first three places in the chain, participants in the strict audience condition included more details in their reproductions than participants in the lenient audience condition (F4,70 = 2.61, p < .05, partial η² = .13). However, by the fourth and fifth reproductions these differences disappeared. The instructions x place in serial reproduction chain interaction was not significant for either the number of words or themes included in the reproductions (both p > .05).

The interaction between audience instructions and story

Univariate analyses showed significant audience instructions × story interactions for all three DVs (words: F1,70 = 10.08, p < .005, partial η² = .13; details: F1,70 = 9.11, p < .005, partial η² = .12; themes: F1,70 = 14.58, p < .0005, partial η² = .17). Separate follow-up ANOVAs for the two audience instruction groups did not find any significant story effects for any of the three DVs under lenient audience instructions. With strict instructions, however, recall performance was always significantly better for the Vanishing Hitchhiker than for the War of the Ghosts story (words: F1,35 = 25.44, p < .0005, partial η² = .42; details: F1,35 = 28.28, p < .0005, partial η² = .45; themes: F1,35 = 15.17, p < .0005, partial η² = .30).

Summary of the core findings

Multivariate analyses and most of the univariate analyses confirmed that, in line with Bartlett’s ideas, recall of a “fixed form” story (The Vanishing Hitchhiker) was generally better than that of a “weird” story (The War of the Ghosts). Our analyses also confirmed Bartlett’s conjecture that recall should depend on the audience – recall was better for a strict than a lenient audience. Even more interesting, perhaps, this strict-audience advantage depended on the story: it improved recall of the “fixed form” story (The Vanishing Hitchhiker) but not recall of the “weird story” (The War of the Ghosts). Most of these effects and interactions were large or moderate. Finally, but perhaps also trivially, recall generally deteriorated with place in the reproduction chain; subsequent reproductions were less accurate than the initial ones. More important, there were no strong interactions overall between place in the reproduction chain and the other variables, meaning that the story and audience effects were largely preserved over successive reproductions.

Conclusion

Defying posthumous misinterpretation (see our introduction), it appears that Bartlett’s intuitions were right after all – firstly, our results provide an encouraging affirmation of Bartlett’s true theory by using material that should be especially memorable. We were not expecting that our inclusion of more meaningful material would ensure that recall would be perfect, but it surely made a noticeable difference.

Secondly, Bartlett was right to emphasise the role of the audience in remembering. We (nor Bartlett, probably) did not necessarily expect this to depend so strongly on the nature of the material, though – a strict audience did not help our participants to remember the weird War of the Ghosts story, but it greatly improved accurate recall of the “well-worn” Vanishing Hitchhiker urban myth.

Attempting to retrospectively explain this discrepancy, we note that a strict audience can induce more accurate reporting only if there is potential for accuracy to begin with. Therefore, precisely because the War of the Ghosts is so weird, it is subject to massive change and little accurate preservation is to be expected. Quite the opposite with the Vanishing Hitchhiker: this culturally compatible story has already crystallised into a more or less stable form with fitting themes and details ready for reproduction if required (e.g., by a strict audience).

In any case, this is a reminder that remembering is a principally social activity (Bartlett’s point of course, but also others’, e.g., Halbwachs, 1925/Citation1992) that depends on the social setting (such as the audience – beyond Bartlett see, e.g., Echterhoff et al.’s, Citation2005, more recent research on audience tuning). The methodological lesson from our study is that certain features of memory (in our study, the accuracy advantage of conventional material) materialise under appropriate conditions only; future researchers are well advised to pay attention to these social features in their research.

Serial reproduction and cultural transmission

A noteworthy if unspectacular aspect of our findings is that nothing of interest really happened over the course of reproduction – essentially, performance got worse, but intriguingly this decline was similar for both stories and in both audience conditions. One might have expected, following Bartlett, that serial reproduction would be the very mechanism that brings about the adaptation of “weird” material in particular, such that there would be a faster decline of memory for such material as compared to “fixed form” stories where this adaptation has already happened culturally. Both stories declined at a similar rate, however. This, in turn, sheds some doubt on the role of serial reproduction in bringing about memory distortion, and prompts us to reconsider the utility of the serial reproduction method to study cultural transmission.

At the outset of his career, Bartlett was interested in cultural change and the effect of contacts between cultures (e.g., Bartlett, Citation1923), with the method of serial reproduction, as we have already noted, also serving as a theory of cultural transmission. As such, Bartlett himself acknowledged one limitation:

To write out a story which has been read is a very different matter from retailing to auditors a story which has been heard. The social stimulus, which is the main determinant of the form in the latter case, is almost absent from the former. (Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 174)

Laboratory control can be achieved, we admit, only at the expense of oversimplification. By forcing serial reproduction into an artificial setting we sacrifice the spontaneity and naturalness of the rumor situation. In place of the deep-lying motivation that normally sustains rumor spreading, we find the “go” of the laboratory rumor depends upon the subject’s willingness to cooperate with the experimenter. … In ordinary life the listener can chat with his informer and, if he wishes, cross-question him (though, in fact he seldom does so), whereas in experiments this doubtful aid is denied the listener. (Allport & Postman, Citation1948, pp. 64–65). (See Treadway & McCloskey, Citation1987, on how even Allport and Postman’s work has also been “transformed” in the literature.)

In the light of the remarkably similar fates of the myth of The Vanishing Hitchhiker and the War of the Ghosts folk tale, our findings provide further evidence (as though the well documented fact of the remarkable persistence of cultural practices were not enough) that the method of serial reproduction also embodies a mistaken theory about how cultural remembering mainly goes on (see Rubin, Citation1995, p. 130 et seq; Tehrani & Riede, Citation2008). Indeed, the very term “transmission” is surely misleading in that it implies a process of essentially passive reception. James Ost’s work (see also our in-depth coverage in the introduction to this special issue; Blank et al., Citation2022) instead inspires us to remember the central importance of social life as transaction, not just transmission, in the study of cultural remembering.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Bartlett’s former students, Broadbent, Oldfield, and Zangwill, eventually dismissed the theory as unacceptably vague (see Brewer, Citation2000). However, in our view, a largely forgotten paper by Oldfield (Citation1954) clarified the basic logic of the theory very effectively (see also Attneave, Citation1959, pp. 86–7). The antagonism may have been as much personal as “scientific.” Bartlett disapproved of Broadbent’s appointment as director of the MRC Applied Psychology Unit at Cambridge (probably more in grief at Kenneth’s Craik’s early death who had been the initial director); he was irritated by Oldfield’s lack of focus; and resented having to retire to make way for Zangwill: “Bartlett moved all of his furniture out of his office before Zangwill came (it was, he said, his own). Zangwill then would joke that his was the first chair where the occupant had nowhere to sit.” (Ian Hunter. Personal communication to Alan Costall, Bishop Grosseteste College, Lincoln, 26th March, 1991)

2 Brunvand (Citation1983, p. 16) argues that these legends retain a “fixed central core” whilst acknowledging that the specific details of the story (exact location, name of the road etc.) are frequently changed as they are transmitted between members of a homogenous folk group.

3 Bartlett’s former student, R. W. Pickford (Citation1940, p. 6) offered the nice example of the British game of football: “It is of great interest that Association Football has spread widely by a process of cultural borrowing from group to group. In this it has undergone surprisingly little change … . This lack of change is probably due to the predominance of British prestige [!] in its transmission, and to the prominence of impulses towards fair play and the morale of group games.” (Pickford’s father had been a prominent official in the game.)

References

- Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. (1948). The psychology of rumor. Henry Holt and Company.

- Attneave, F. (1959). Applications of information theory to psychology. Rinehart and Winston.

- Bartlett, F. C. (1920). Some experiments on the reproduction of folk-stories. Folk-Lore, 31(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1920.9719123

- Bartlett, F. C. (1923). Psychology and primitive culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Banaji, M. R., & Crowder, R. G. (1989). The bankruptcy of everyday memory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1185–1193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1185

- Bartlett, F. C. (1958). Thinking: An experimental and social study. George Allen & Unwin.

- Beardsley, R. K., & Rosalie Hankey, R. (1942). The vanishing hitchhiker. California Folklore Quarterly, 1(4), 303–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1495600

- Blank, H., Nash, R. A., Otgaar, H., Patihis, L., & Rubínová, E. (2022). False remembering in real life: James Ost’s contributions to memory psychology. Memory, X, YYY–ZZZ.

- Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (1990). Gist is the grist: Fuzzy-trace theory and the new intuitionism. Developmental Review, 10(1), 3–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(90)90003-M

- Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (2005). The science of false memory. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195154054.001.0001

- Brewer, W. F. (2000). Bartlett’s concept of the schema and its impact on theories of knowledge representation in contemporary cognitive psychology. In A. Saito (Ed.), Bartlett, culture and cognition (pp. 69–89). Psychology Press.

- Brown, S. D., & Reavey, (2015). Turning around on experience: The ‘expanded view’ of memory within psychology. Memory Studies, 8(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698014558660

- Brunvand, J. H. (1983). The Vanishing Hitchhiker: urban legends and their meanings. GB: Pan Books Ltd.

- Costall, A. (1992). Why British psychology is not social. Frederic Bartlett’s Promotion of the new Academic Discipline. Canadian Psychology, 33(3), 633–639.

- Davis, M. (2018). Frederic Bartlett: A question of priority. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(4), 1030–1031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2017.1310910

- Dudukovic, N. M., Marsh, E., & Tversky, B. (2004). Telling a story or telling it straight: The effects of entertaining versus accurate retellings on memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.953

- Echterhoff, G., Higgins, E. T., & Groll, S. (2005). Audience-tuning effects on memory: The role of shared reality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.257

- Edwards, D., & Middleton, D. (1986). Joint remembering: Constructing an account of shared experience through conversational discourse. Discourse Processes, 9(4), 423–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01638538609544651

- Edwards, D., & Middleton, D. (1987). Conversation and remembering: Bartlett revisited. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 1(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350010202

- Edwards, D., Middleton, D. & Potter, J. (1992). Towards a discursive psychology of remembering. The Psychologist, 5, 56 -60.

- Erdelyi, M. H. (1998). The recovery of unconscious memories: Hypermnesia and reminiscence. University of Chicago Press.

- Gauld, A., & Stephenson, G. M. (1967). Some experiments relating to Bartlett’s theory of remembering. British Journal of Psychology, 58(1–2), 39–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1967.tb01054.x

- Haddon, A. C. (1895). Evolution in art as illustrated by the life histories of designs. Walter Scott Ltd.

- Halbwachs, M. (1992). On collective memory. University of Chicago Press. [Original work published in 1925.].

- Hyman, Ira E. (1994), “Conversational Remembering: Story Recall with a Peer Versus an Experimenter,” Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8 (1), 49–66.

- Hyman, I. E. Jr. (1999). Creating false autobiographical memories: Why people believe their memory errors. In E. Winograd, R. Fivush, & W. Hirst (Eds.), Ecological approaches to cognition: Essays in honor of Ulric Neisser (pp. 229–252). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Jenkins, J. G. (1935). Review of Remembering by F. C. Bartlett. American Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 712–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1416025

- Kintsch, W. (1995). Introduction. In F. C. Bartlett (Ed.), Remembering (pp. xi–xv). Cambridge University Press.

- Koriat, A., & Goldsmith, M. (1996). Monitoring and control processes in the strategic regulation of memory accuracy. Psychological Review, 103(3), 490–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.3.490

- Kurke, L. B., Weick, K. E., & Ravlin, E. C. (1989). Can information loss be reversed? Evidence for serial reconstruction. Communication Research, 16(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009365089016001001

- Lynn, S. J., & McConkey, K. M. (Eds.). (1998). Truth in memory. The Guilford Press.

- Marsh, E. J., & Tversky, B. (2004). Spinning the Stories of our Lives. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18(5), 491–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1001

- Mesoudi, A., & Whiten, A. (2008). The multiple roles of cultural transmission experiments in understanding human cultural evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1509), 3489–3501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0129

- Michaelian, K., & Sutton, J. (2017). Memory. “The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/memory/>.

- Michaelian, L. (2016). Mental time travel: Episodic memory and our knowledge of the personal past. MIT Press.

- Mithen, S. (1996). The prehistory of the mind. Thames & Hudson.

- Neisser, U. (1976). Cognition and reality. Freeman & Co.

- Neisser, U., & Hyman, I. E. (Eds.) (2000). Memory observed: Remembering in natural contexts. Worth Publishers.

- Neisser, U. (1981). John Dean's memory: A case study. Cognition, 9(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(81)90011-1

- Oldfield, R. C. (1954). Memory mechanisms and the theory of schemata. British Journal of Psychology, 45, 14–23.

- Ost, J. (2003). Essay book review: Seeking the middle ground in the memory wars. British Journal of Psychology, 94(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000712603762842156

- Ost, J., & Costall, A. (2002). Misremembering Bartlett: A study in serial reproduction. British Journal of Psychology, 93(2), 243–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000712602162562

- Pace, R. W., Boren, R. R., & Peterson, B. D. (1975). Communication behaviour and experiments: A scientific approach. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc.

- Pickford, R. W. (1940). The psychology of the history and organization of association football. British Journal of Psychology, 31, 129–144.

- Roediger, H.L. III, Bergman, E.T., & Meade, M.L. (2000). Repeated reproduction from memory. In A. Saito (Ed.), Bartlett, culture and cognition (pp. 115-134). Hove, UK: Psychology press.

- Rubin, D. C. (1995). Memory in oral traditions: The cognitive Psychology of epic, ballads, and counting-out rhymes. Oxford University Press.

- Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 362(1481), 773–786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2087

- Tehrani, J. J., & Riede, F. (2008). Towards an archaeology of pedagogy: Learning, teaching and the generation of material culture traditions. World Archaeology, 40(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240802261267

- Treadway, M., & McCloskey, M. (1987). Cite unseen: Distortions of the Allport and Postman rumor study in the eyewitness testimony literature. Law and Human Behavior, 11(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01044836

- Vicario, G. B. (1994). Gaetano kanizsa: The scientist and the man. Japanese Psychological Research, 36(3), 126–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4992/psycholres1954.36.126

- Wagoner, B. (2017). What makes memory constructive? A study in the serial reproduction of Bartlett’s experiments. Culture & Psychology, 23(2), 186–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X17695759

- Woodworth, R. S. (1938). Experimental psychology. New York: Holt.

- Wynn, V. E., & Logie, R. H. (1998). The veracity of long-term memories—Did Bartlett get it right? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199802)12:13.0.CO;2-M

Appendices

Appendix 1: Stimulus stories.

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

A dozen miles outside of Baltimore, the main road from New York (Route Number One) is crossed by another important highway. It is a dangerous intersection, and there is talk of building an underpass for the east-west road. To date, however, the plans exist only on paper.

Dr. Eckersall was driving home from a country-club dance late one Saturday night. He slowed up for the intersection, and was surprised to see a lovely young girl, dressed in the sheerest of evening gowns, beckoning him for a lift. He jammed on his brakes, and motioned her to climb into the back seat of his roadster. “All cluttered up with golf clubs and bags up here in front,” he explained. “But what on earth is a youngster like you doing out here all alone at this time of night?”

“It's too long a story to tell you now,” said the girl. Her voice was sweet and somewhat shrill – like the tinkling of sleigh bells. “Please, please take me home. I'll explain everything there. The address is 13 North Charles Street. I do hope it's not too far out of your way.”

The doctor grunted, and set the car in motion. He drove rapidly to the address she had given him, and as he pulled up before the shuttered house, he said, “Here we are.” Then he turned around. The back seat was empty!

“What the devil?” the doctor muttered to himself. The girl couldn't possibly have fallen from the car. Nor could she simply have vanished. He rang insistently on the house bell, confused as he had never been in his life before. At long last the door opened. A grey-haired, very tired-looking man peered out at him.

“I can't tell you what an amazing thing has happened,” began the doctor. “A young girl gave me this address a while back. I drove her here and … ”

“Yes, yes, I know,” said the man wearily. “This has happened several other Saturday evenings in the past month. That young girl, sir, was my daughter. She was killed in an automobile accident at that intersection where you saw her almost two years ago.”

(taken from Brunvand, Citation1983)

The War of the Ghosts

One night two young men from Egulac went down to the river to hunt seals, and while they were there it became foggy and calm. Then they heard war-cries, and they thought: “Maybe this is a war-party”. They escaped to the shore, and hid behind a log. Now canoes came up, and they heard the noise of paddles, and saw one canoe coming up to them. There were five men in the canoe, and they said:

“What do you think? We wish to take you along. We are going up the river to make war on the people”.

One of the young men said: “I have no arrows”.

“Arrows are in the canoe”, they said.

“I will not go along. I might be killed. My relatives do not know where I have gone. But you”, he said, turning to the other, “may go with them.”

So one of the young men went, but the other returned home.

And the warriors went on up the river to a town on the other side of Kalama. The people came down to the water, and they began to fight, and many were killed. But presently the young man heard one of the warriors say: “Quick, let us go home: that Indian has been hit”. Now he thought: “Oh, they are ghosts”. He did not feel sick, but they said he had been shot.

So the canoes went back to Egulac, and the young man went ashore to his house, and made a fire. And he told everybody and said: “Behold I accompanied the ghosts, and we went to fight. Many of our fellows were killed, and many of those who attacked us were killed. They said I was hit, and I did not feel sick”.

He told it all, and then he became quiet. When the sun rose, he fell down. Something black came out of his mouth. His face became contorted. The people jumped up and cried.

He was dead.

(taken from Bartlett, Citation1932, p. 65).

Appendix 2: Instructions to participants.

Strict audience instructions: Please write down the story you have just read as best you can. Please try to reproduce it exactly. It is very important that you be as precise as you can. Try to use exactly the same words as they appeared in the story as much as possible. Where you cannot remember the exact wording, be sure to at least get the facts and events exactly correct. Do not invent facts to make it a better story. Imagine that you are giving a statement to a policeman and accuracy is important. If you cannot remember something don’t guess, just leave it blank. When you have finished, turn the paper face down on the table.

Lenient audience instructions: Please write down the story you have just read. Don’t worry about being exact; you are not being tested for accuracy. Just tell the story as you remember it. Imagine you are relating it to a friend who has never heard the story before. When you have finished, turn the paper face down on the table.