ABSTRACT

People with a negative body image may be more likely to recall negative memories of their body, but also be motivated to avoid retrieving specific memories to prevent triggering aversive emotions (e.g., disgust). Such inclination to retain at a global level of memory recall may hamper the correction of their negative body image. In previous research using Autobiographical Memory Tests (AMTs) with minimal instructions, we failed to find an overgeneral memory bias specific to individuals with a negative body image but observed low specificity overall in response to body cue words. In the present study (N = 153), we included the traditional AMT next to a minimal instructions AMT and explored the idea that sensory reliving may be relevant to avoidance by assessing sensory reliving ratings next to memory specificity. A negative body image was associated with more negative body memories. In both AMTs, the findings failed to support our prediction that a more negative body image would be associated with lower specificity or sensory reliving. The findings are consistent with the view that autobiographical memories might be an important factor in defining one’s body image, yet cast doubt on the relevance of avoidant retrieval of body-related memories in non-clinical samples.

The concept of body image refers to people’s perceptions, cognitions, and emotions about their bodies (Grogan, Citation1999; Muth & Cash, Citation1997). For many people, especially young women, body image is an important part of their identity (Cash, Citation2002; Marsh, Citation1990). Like any major aspect of our identities, our body image likely influences and is influenced by our autobiographical memories. In other words, our self-images determine how we remember past events and, in turn, we derive self-defining information from these memories (Conway et al., Citation2004). Unfortunately, many people have a negative image of their own bodies, which means, for example, that they are dissatisfied and preoccupied with their appearance (Cash, Citation2002; Swami et al., Citation2010). Such a negative body image represents a prevalent and persistent societal concern that is associated with detrimental physical and psychological consequences (e.g., Davison & McCabe, Citation2005; Fallon et al., Citation2014; Johnson & Wardle, Citation2005; Tiggemann, Citation2004; Wilson et al., Citation2013). Due to the reciprocal relationship between our memories and our self-concepts, autobiographical memories may play an important role in maintaining a negative body image.

A negative body image is characterised by a range of negative emotions associated with a person’s body. Next to a general dissatisfaction with one’s appearance, a fear of becoming fat (e.g., Dalley et al., Citation2012), and feelings of shame about one’s body (e.g., Duarte et al., Citation2015), a negative body image also seems to include feelings of disgust about the own body (e.g., Moncrieff-Boyd et al., Citation2014; Stasik-O’Brien & Schmidt, Citation2018; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2018). These negative emotions characterizing a person’s body image are also likely to be associated with the autobiographical memories the person has of their own body. In line with this, two previous studies found that women who appraised their appearance as repulsive, recalled memories that involved negative appraisals of their own bodies (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022) and showed elevated levels of disgust in response to their body-related autobiographical memories (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2021b).

According to theoretical accounts of autobiographical memory (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000), memory is organised hierarchically. People may search for a memory in a top-down fashion (i.e., generative retrieval), going from the higher, more abstract levels of memory representation (e.g., life-time periods, summaries of events) to the lowest level that contains event-specific-knowledge (ESK). ESK is sensory-rich, detailed and vivid information (Conway, Citation2005; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000; Gardiner, Citation2001; Tulving, Citation2001). Memories rich in ESK are called episodic or specific autobiographical memories and are associated with strong (negative) emotions because of their high level of detail and vividness (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000). In order to prevent experiencing intense negative emotions, people may try to avoid recalling specific memories (i.e., functional avoidance; Williams, Citation2006). As such, avoidance processes can truncate generative memory searches at the higher levels of the memory system (Williams et al., Citation2007). Such avoidance processes may also operate in the retrieval of body-related memories. Importantly, in case of negative body image, avoidance may be fueled by the emotion of disgust whose defensive nature promotes avoiding aversive stimuli (cf. Curtis et al., Citation2011; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022).

Memory specificity is usually examined with the Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT; Williams & Broadbent, Citation1986), in which people are instructed to recall personal memories in response to various cue words. Traditionally, the AMT included detailed instructions and practice to recall specific memories, that is, memories that refer to a point in time of at most 24 hours. This traditional version of the AMT appears to have a good sensitivity to detect difficulties with recalling specific memories in clinical populations (e.g., mood disorders; Williams et al., Citation2007). Because the traditional AMT often exhibited rather low sensitivity (ceiling effects) in non-clinical samples, Debeer and colleagues (Citation2009) adapted it to a version that included only minor instructions and little/no practice (Minimal Instructions AMT). Instead of measuring people’s ability to recall specific memories (traditional AMT), this version assesses people’s tendency to recall specific memories. As such, the minimal version of the AMT should allow for more variation in memory specificity levels and increase the AMT’s sensitivity in non-clinical samples. This was supported by Debeer and colleagues (Citation2009), who reported average specificity proportions of around 0.5 (50%) and found associations of (low) specificity with (high) depression levels when using the minimal instructions AMT in a non-clinical sample.

In two previous studies, we therefore also chose the minimal instruction AMT to measure the specificity of body-related autobiographical memories in nonclinical samples of women with high and low body image concerns (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022, Citation2021b). Although women with high body concerns reported relatively many memories that involved negative body appraisals, we failed to find support for the hypothesis that women with high body concerns would also be characterised by fewer specific memories. However, compared to Debeer and colleagues (Citation2009), we generally found substantially lower memory specificity proportions (ranging from 0.17 to 0.25) in these studies relying on body-related cue words. Importantly, the distribution of specificity proportions appeared to reflect floor effects of memory specificity levels. This may cast doubt on the suitability of the minimal instructions AMT to examine the specificity of body-related memories in nonclinical participants. According to Conway (Citation1996), the default level of memory recall is at the general (i.e., non-specific) level. The absence of explicit instructions to recall specific memories in the Minimal Instructions AMT might not provide a strong incentive to deviate from the default general level (e.g., summaries of events). Because our bodies are part of every experience we have, we likely have an immense number of body-related memories. As such, body-related memories may be especially prone to be recalled at the general level. Therefore, more explicit instructions to deviate from that level, as they are given in the traditional AMT, could be crucial in order to examine difficulties to retrieve specific body-related memories.

Apart from the particular instructions of the AMT, it may be that also the operationalisation of memory specificity needs to be reconsidered when examining (the avoidance of) body-related memories. The 24-hour may not be optimal to capture the essential features of ESK. Consider the following memory: “When I stand in the shower in the morning and look down on myself, I feel revolted to see my protruding belly.” This memory would not be categorised as a specific, but as a general memory (i.e., summarising multiple experiences or extended time periods) in the AMT. However, it does seem to contain characteristics typical of ESK, including visual imagery, sense of reliving, as well as visceral and affective information. Although considered a typical feature of an episodic/specific memory (Tulving, Citation2001), the subjective experience of reliving (sensory) details of one “event” or action (e.g., looking into the mirror) can thus also be present in a general memory (e.g., looking into the mirror each morning). It is the recall of sensory details in an adverse memory that can trigger negative affect and is therefore the target of avoidance in a strategic memory search (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000; cf. Williams, Citation2006). Because of the immense amount of body-related memories, they might be more likely categorised as general memories in the AMT even though they could contain a vivid sense of reliving sensory details. AMT specificity may, therefore, not be an adequate measure of the reliving of sensory details in body-related memories. To our knowledge, this has not yet been studied (in the context of body image) and we may need other measures to investigate if individuals with high body dissatisfaction show the inclination to avoid reliving sensory details in body-related memories.

In light of these methodological and conceptual considerations, we designed the current study to further examine the relevance of avoidant retrieval of body-related autobiographical memories. First, we examined the influence of AMT instructions/format on memory specificity of body-related memories by comparing the Minimal Instructions AMT with the Traditional AMT. We hypothesised that the Traditional AMT would yield more specific memories than the Minimal Instructions AMT (H1), thereby increasing its sensitivity to find meaningful differences in memory specificity as a function of people’s body image concerns. Second, we included an assessment of mentally reliving sensory details that may be better suited to capture the essential features of a vivid, sensory-rich, and detailed recall within the current context of body-related memories than memory specificity. Our objective was to investigate further the relationship between negative body image and avoidance of reliving sensory details of body-related memories. In line with the assumption that self-schemas bias autobiographical memory processing (Beck & Haigh, Citation2014), we hypothesised that a negative body image would be positively associated with recalling memories that reflect more negative body-related concerns (H2). We then hypothesised that a negative body image predicts lower memory specificity (H3a) and/or lower sensory reliving (H3b), particularly in people with a high tendency to prevent experiencing body-related disgust. Hypothesis 3a was examined in the Traditional AMT only, due to expected floor effects in specificity proportions in the minimal instructions AMT.

Method

Statement of transparency

We pre-registered the research questions, hypotheses, study method, data processing, and data analyses on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/q4wgh). Changes/Additions to the pre-registration were as follows: (1) We included the dissatisfaction memory ratings in the assessment of negative body image theme (which originally only included disgust ratings) of autobiographical memories to provide a more comprehensive picture of body image characteristics and for comparability to an earlier study (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022); (2) In order to appropriately deal with multivariate outliers, which we did not specify in the pre-registration, we excluded cases that appeared influential on more than one variable from the analyses; (3) If distribution indices suggested violated assumptions which could not be addressed through winsorising/deleting influential cases, we considered other methods (e.g., use of non-parametric test) to deal with these violations. (4) Originally, we used the term “episodic quality” for the sensory reliving ratings, because of our aim to capture the essential features of ESK. However, in the review process of the submitted manuscript it became apparent that the term “episodic” (and the concept of ESK) refers to a single episode and relating it to general memories would thus be suboptimal. Accordingly, we replaced “episodic quality” with “sensory reliving” in the present article. In the OSF study materials, OSF datafiles, and quotes of the sensory reliving measure in the materials section, we retained the original term (“episodic quality”).

Study design and power analysis

The current study had a cross-sectional experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to either the Minimal Instructions AMT or the Traditional AMT. With the aim to achieve at least 80% power to detect at least medium-sized effects in our planned analyses, we conducted several a priori power calculations in G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2007). We found that we would need at least N = 128 (64 per AMT condition) for an independent samples t-test (with d = 0.5; α = 0.05); n = 67 per AMT (N = 134) for our correlation coefficients (correlation H1: 0.3; α = 0.05; Power: 80%; Correlation H0: 0; hypothesis 1); and n = 68 per AMT (N = 136) for our multiple regressions analyses (R2 deviation from zero in a linear multiple regression with two predictors; f2 = 0.15; α = 0.05). We restricted data collection to a period of two weeks in which a minimum of 128 participants and a maximum of 200 participants (to allow for possibilities of detecting smaller effect sizes) were to be tested.

Participants

Participants were women living in Groningen (the Netherlands). In total, we included N = 153 participants in the study (n = 76 Traditional AMT; n = 77 Minimal Instructions AMT), who were mainly German (39.2%) or Dutch (24.2%), with the rest (36.6%) indicating a variety of other nationalities (e.g., other European; Asian; American). The mean age of participants was 20.5 (SD: 2.31) years with a range from 17 to 29.

Participant inclusion and exclusion

We recruited participants via two University-based participant platforms (Paid: Participation compensated by payment; Course Credit: Participation compensated by course credit for the first-year Psychology Bachelor program). Only participants who identified as female could sign up for the study. Of the 166 participants who came to the study, 13 participants were excluded because they discontinued participating in the study (n = 1), a technical error occurred (n = 1), they indicated that they did not participate in the study seriously (n = 10), or failed on three or more out of 5 questions of the English language assessment (n = 1). No participants were excluded because they correctly guessed a hypothesis of the study or gave non-sense responses on 50% of the responses in the AMT.

Materials

The study was conducted in Qualtrics ©, Provo, UT.

Self-report questionnaires

Shape and weight concern subscales of the eating disorder Examination-questionnaire (Version 6.0; EDE-Q 6.0; Fairburn & Beglin, Citation2008)

A composite score of the weight and shape concern subscales of the most recent version of the EDE-Q was used to measure negative body image. The subscales were chosen as an assessment of body image because they measure important dimensions of a negative body image (e.g., body dissatisfaction, over-evaluation of and preoccupation with shape/weight). The items of the subscales are answered on a 7-point Likert scale (0: no days – 6: every day). Cronbach’s alpha of the composite scale was 0.94.

Self-disgust in Eating Disorders Scale (SDES; Moncrieff-Boyd et al., Citation2014)

The SDES is a 16-item self-report questionnaire that assesses habitual levels of disgust directed towards the own body. The items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scores can range from 10 to 70 (after removing 6 filler items, 10 items remain for scoring), with higher scores indicating higher levels of body-related self-disgust. Crohnbach’s alpha was 0.85 in the current study.

Body-related Disgust Avoidance Questionnaire (B-DAQ; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2021a)

The Disgust Avoidance Questionnaire (DAQ; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2021a) assesses people’s tendencies to avoid experiencing disgust and consists of 17 items and four subscales: disgust prevention, disgust escape, cognitive disgust avoidance, behavioural disgust avoidance. A version of the DAQ that assesses people’s tendencies to avoid experiencing body-related disgust (B-DAQ) consists of 18 items and the same four subscales. We assessed body-related disgust prevention with the 9 items disgust prevention subscale of the B-DAQ (Crohnbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Autobiographical Memory Tests (AMTs)

In the computerised AMTs, participants were asked to recall personal experiences in response to 10 abstract body/weight-related cue words. Dutch and German participants completed the AMTs in their native language, and participants with other nationalities completed the AMTs in English. The cue words were taken from a previous study (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022) and are listed in Appendix ().

Traditional Autobiographical Memory Test (Williams & Broadbent, Citation1986)

In line with Williams and Broadbent (Citation1986), and Williams (Citation2000), the Traditional AMT provides instructions to recall specific memories, that is, memories of personally experienced events that took place on one specific day. The instructions included a detailed description of the criteria of a specific memory and a number of examples of memories that fit or did not fit these criteria. In addition, the AMT instructs participants not to refer to memories that happened within the previous 7 days or that they already gave in response to a previous cue word. Participants were given three practice cue words (“happy”, “safe”, and “angry”) and after each practice round, they were asked whether the memory they wrote down would fit the criteria for a specific memory (1. “Is your answer about an event that took place on a specific day?” Yes/No; 2. “Is your answer about an event that you have experienced yourself?” Yes/No; 3. “Is your answer about an event that you experienced longer than 7 days ago?” Yes/No). If participants answered (at least) one of the questions with “No”, they were asked to adapt the memory to fit the specificity criteria. Participants were given a time-limit of 1 minute to think of a memory and start writing it down, but once they were writing they were given as much time as needed to finish their response. Each cue word was presented individually on the computer screen with the instruction “Can you write down a specific moment or event that the word _____ reminds you of?” and a text box in which participants could type their answer. Below the textbox, a statement indicated that participants would be forwarded automatically to the next cue word unless they started writing down a response within one minute. The time limit started immediately upon the presentation of the cue word. Participants were asked to only start writing once they have a memory in mind.

Minimal Instructions Autobiographical Memory Task (Debeer et al., Citation2009)

Following Debeer and colleagues (Citation2009), the minimal instructions AMT instructs participants to write down personally experienced events without a description of what constitutes a specific memory. Participants were informed that they will be given one minute to write down each memory. Participants were instructed not to include events that happened in the last 7 days and that they had already given in response to a previous cue word. Each cue word was presented individually on the computer screen with the instruction “Can you write down a personal experience that the word _____ reminds you of?” and a text box in which participants could type their answer. Below the textbox, a statement indicated that participants will be forwarded automatically to the next cue word after one minute. The time limit started immediately after the cue word appeared. Participants were given one practice cue word (“safe”).

Memory ratings

Each AMT was followed by a rating task. The task presented a quote of each memory provided in the AMT in the same sequence in which the AMT cues had been presented. Each memory quote appeared individually on the computer screen with three rating scales (specificity; body centrality; negative body image theme) underneath (on one page).

Specificity

Specificity was assessed with a multiple choice item with the options to categorise each memory to one of four categories: (a) a specific memory (memory of an event that occurred within the course of one day; e.g., “the visit to the beach with my friends a month ago”), (b) a categoric memory (memory of a summary of events; e.g., “visiting the beach with my friends”), (c) an extended memory (memory of a period longer than one day; e.g., “the last summer vacation at the beach”), or (d) an omission (no memory was recalled).

Specificity coding

In addition to the self-reported specificity rating, the specificity of memories was coded by raters. We followed the specificity coding procedure of Debeer and colleagues (Citation2009). The raters were blind to AMT condition, but we cannot rule out that the content of memories could have potentially given away AMT condition. In addition to the four categories for the self-reported rating (specific, categoric, extended, omission), the raters could categorise memories into (e) a semantic associate (verbal associations with the cue; e.g., “the beach”), or (f) rest (memory violating the instructions; e.g., referring to an event in the past 7 days). After a first rater coded all memories, they were compared to the self-reported rating of the participant. Memories for which the codes were diverging from each other were coded by a second rater. In order for a memory to be classified, two out of the three codes (by the participant, the first rater, and the second rater) needed to be the same. If this was not the case, the memory was coded as “rest”. Memories assigned to the “rest” category were further distinguished into “rest-general” if all three codes fell within the general categories (categoric, extended, semantic associate), or “rest-other” if there was no consensus in the codes to whether the memory is specific or general. In total, 92.4% (1413 out of 1530) memories could be categorised, and 7.6% were uncategorised as rest-general (32) or rest-other (85) memories. The proportion of participant-rater agreement for specific memories was 78.4% (78.4% of the memories coded as specific by the participant were also coded as specific by at least one rater).

Body centrality

We measured body centrality with a slider scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 100 (Very much) assessing the centrality of the own body in each memory (“How central/prominent was your body in the memory you recalled?”).

Negative body image theme

Two separate slider scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much) in response to the statement “This memory involves an image of my body that is characterised by:” were used to assess (a) dissatisfaction and (b) disgust. Four additional slider scales were included as distractor items and assessed pride, acceptance, happiness, and shame. We calculated negative body image theme scores by averaging the disgust and dissatisfaction ratings across recalled memories.

Sensory reliving rating

After all other ratings were completed, the sensory reliving rating was presented on a separate page that included a description and a quote of each memory. In the following quotes from the sensory reliving rating, the original term “episodic” is used (see transparency statement). The sensory reliving rating included the following short description of a sensory-rich memory:

An episodic memory is a memory in which you mentally relive an experience as if you travel back in time. When remembering, it is as though you are thinking the same things or feeling the same emotions you experienced in the past. You re-experience sensory information like sounds, smells, or tastes. You bodily “feel” yourself in the memory and relive particular physical reactions or sensations you had during the experience.

For example, if you remember visiting the park and you mentally relive the experiences you made there, see the park’s areas in the mind’s eye, re-experiencing sounds, smells, and sights, then your memory contains a lot of episodic information. Note that the memory does not have to be specific, i.e., related to one specific day, to be episodic.

On the other hand, if you know you’ve been to the park without reliving your experience of having been there, or if you have a vague memory of having had a conversation with somebody but don’t recall details of that conversation, your memory has a low episodic quality.

Additional scales and descriptive measures

Cue concreteness rating

We assessed cue concreteness using a multiple-choice matrix listing all cue words to be rated from abstract (1) to concrete (5). The instructions were as follows (adapted from Brysbaert et al., Citation2014):

Some words refer to things or actions in reality, which you can experience directly through one of the five senses. We call these words concrete words (e.g., “sweet”). Other words refer to meanings that cannot be experienced directly but which we know because the meanings can be defined by other words. These are abstract words (e.g., “justice”). Still other words fall in between the two extremes because we can experience them to some extent and in addition we rely on language to understand them. We want you to indicate how concrete the meaning of each word is for you by using a 5-point rating scale going from abstract to concrete.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised (CESD-R; Eaton et al., Citation2004)

The CESD-R is a 20-item self-report screening test for depression, assessing symptoms for a major depressive episode, which have to be rated based on their frequency in the previous 1–2 weeks. The answer options range from 0 (Not at all or less than 1 day a week), 1 (1–2 days last week), 2 (3–4 days a week), 3 (5–7 days last week) to 4 (Nearly every day for 2 weeks). Crohnbach’s alpha was 0.70.

Demographic information

The demographic assessment included questions asking for participants’ age, gender (male/female/other), nationality (Dutch/German/Other), primary language (Dutch/German/Other), language proficiency (‘Which of the following languages can you understand at a professional level?’ (Dutch/German/English) and field of study (Psychology/Other/I do not study).

English language proficiency

The English language test included five questions which included a question or incomplete sentence which the participants had to answer or complete correctly (e.g., Question: Can I park here? Answers: (a) Sorry, I did that. (b) It’s the same place, (c) Only for an hour).

Motivation

We assessed participants’ motivation by asking whether they were able to stay motivated during the study (‘Was it for any reasons not possible for you to stay motivated during the study? – I was not able to stay motivated and to properly engage in the study/I was able to stay motivated during the study.’).

Hypothesis and notes

We asked participants to write down what they think the hypothesis of the study was and to write down any remarks/notes they had about the study.

Procedure

Participants were tested at the Faculty of Behavioral and Social Sciences of the University of Groningen in November 2019 in a lab room with four separate cubicles, allowing to test four participants simultaneously. First, participants read the study information sheet and gave informed consent. Participants filled in the demographic information assessment and the SDES and afterwards were randomly allocated using the Qualtrics Randomiser function to either the Traditional or the Minimal Instructions AMT condition. After completing the AMT, participants engaged in the memory rating. Afterwards, participants filled out the cue concreteness rating, the EDE-Q, the DAQ, and the B-DAQ. In-between the DAQ and the B-DAQ, participants completed a brief filler task (spot the difference) which was included to alleviate possible boredom effects. Afterwards, participants completed two questionnaires that were not relevant to the current project (they were part of a student project): the Body Image Shame Scale (BISS; Duarte et al., Citation2015) and the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4; Schaefer et al., Citation2015). Participants then filled out the CESD-R, and the English Language Assessment. At the end of the study, participants were asked to indicate their motivation, to give their guess about the study’s hypotheses, and to leave notes. Participants were then debriefed about the purpose of the study and asked to watch a short video clip conveying body positivity.

Analysis

The analyses were conducted in SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Citation2019) and JASP version 0.14.1.0 (JASP Team, Citation2020). We examined the assumptions of all analyses carefully, and, if violated, report on adjusted analyses (e.g., with winsorised extreme univariate cases; with removed extreme multivariate cases; using non-parametric tests) in the results section and report the original analyses in the appendix. Unless stated otherwise, assumptions of all main and post-hoc analyses were met. In addition to the null hypothesis significance tests, we used Bayesian analyses (with default priors), and evaluated Bayes Factors (BF) according to common guidelines (van Doorn et al., Citation2021)Footnote1. We corrected for multiple testing with the Holm-Bonferroni correction which was applied to all post-hoc analyses.

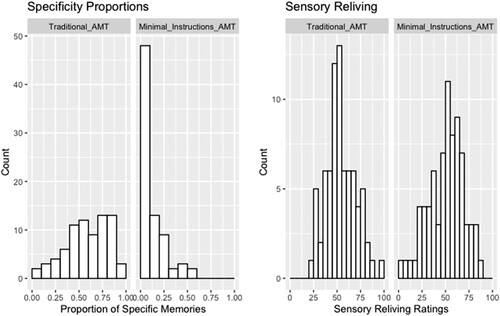

We calculated the proportion of specific memories by dividing the number of memories coded as specific by 10. To examine the effect of AMT format on memory specificity, we compared specificity proportions in the Traditional and Minimal Instructions AMT (Hypothesis H1). Because of the skewed distribution of memory specificity in the Minimal Instructions condition (see S1, figure 1; https://osf.io/67dmr/), we conducted a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test. We calculated memory sensory reliving by dividing the sum of memory sensory reliving ratings by 10. We examined the association between memory specificity and sensory reliving with bivariate correlation coefficients for each AMT. In the Traditional AMT, we report the Pearson’s correlation with one extreme case excluded (case 62; see S1, figure 2; https://osf.io/67dmr/), and in the Minimal Instructions AMT, we report on the non-parametric Spearman’s correlation coefficient (BF based on Kendall’s tau) because of an ordinal scatterplot distribution (see S1, figure 3; https://osf.io/67dmr/).

We calculated the memory’s negative body image theme (negative memory theme) by dividing the combined disgust and dissatisfaction ratings by the total number of memories recalled (i.e., 10 minus omissions). In order to examine the relationship between negative body image (NBI; composite of the EDE-Q weight and shape-concern subscales) and negative memory theme, we computed a Pearson’s correlation coefficient per AMT condition (Hypothesis H2). We also examined the association between self-disgust (SD; SDES scores) and negative body image with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient. We then tested whether negative body image, body-related disgust prevention, and their interaction were predictive of memory specificity (in Traditional AMT only; Hypothesis H3a) or sensory reliving (in both AMTs; Hypothesis H3b). We assessed negative body image by the composite (i.e., average) of the shape-concern and weight-concern subscales of the EDE-Q (mean-centered), and disgust prevention by the prevention subscale of the B-DAQ (mean-centered). We conducted a multiple linear regression analysis with negative body image, disgust prevention, and the interaction of disgust prevention and negative body image on memory specificity (DV) in the Traditional AMT. We excluded one extreme case (case 62; see S1, figure 4; https://osf.io/67dmr/) from this regression analyses on memory specificity. We then conducted two multiple linear regression analyses (one for each AMT) with the same predictors on the averaged sensory reliving ratings. We excluded two extreme cases (case 62 in Traditional AMT; case 137 in Minimal Instructions AMT; see S1, figure 5 & figure 6; https://osf.io/67dmr/) from the regression analyses on sensory reliving.

Material and data availability statement

The materials and data of this study are publicly available on the OSF at https://osf.io/9r246/.

Results

Hypothesis 1: specificity and sensory reliving of autobiographical memories

gives the mean proportions of different memory types based on the specificity coding (specific, general, semantic associate, rest, and omissions) and sensory reliving ratings per AMT condition. displays the distributions of specificity proportions and sensory reliving ratings per AMT format. We found a statistically significant higher proportion of specific memories in the Traditional AMT than in the Minimal Instructions AMT (Mann–Whitney U: W = 5572; p < .001; rank biserial correlation = 0.90; BF10 = 5.37 × 106 [1000 samples]). The rank biserial correlation indicates a large difference between conditions and the Bayes Factor (BF) suggests strong evidence in favour of the alternative. We did not find statistically significant correlations between memory specificity and sensory reliving ratings in the Traditional AMT (Pearson’s r(73) = 0.10; p = .382; BF10 = 0.21) or the Minimal Instructions AMT (Spearman’s r(75) = 0.05; p = .665; BF10 [based on Kendall’s tau = .04] = 0.16). The BFs suggest moderate evidence for the null over the alternative hypothesis. All results were comparable to results obtained with parametric analyses/complete data (see S2; https://osf.io/gqyav).

Figure 1. Histograms of specificity proportions and sensory reliving ratings in the traditional AMT and the minimal instructions AMT.

Table 1. Means and SEs of Memory Type Proportions, Sensory Reliving, Negative Memory Theme, Negative Body Image, Self-Disgust, and Body-Related Disgust Prevention per AMT Condition.

Hypothesis 2: negative body image theme in autobiographical memories

gives the mean negative memory theme (disgust and dissatisfaction ratings), Negative Body Image (NBI; combined EDE-Q weight and shape-concern subscales) and Self-Disgust (SD; SDES scores) scores for each AMT condition. Overall, NBI showed a positive correlation with SD (r(151) = 0.51; p < .001; BF10 = 5.23 × 109). In both AMTs, NBI was positively correlated with Disgust ratings (Traditional AMT: r(74) = 0.45; p < .001; BF10 = 590.15; Minimal Instructions AMT: r(75) = 0.37; p = .001; BF10 = 26.57) and Dissatisfaction ratings (Traditional AMT: r(74) = 0.52; p < .001; BF10 = 11066.58; Minimal Instructions AMT: r(75) = 0.49; p < .001; BF10 = 3919.11). All correlations were of moderately high strength and the BFs suggest strong evidence for the alternative over the null hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: avoidance of autobiographical memories

In addition to NBI scores, specificity proportions, and sensory reliving ratings, presents mean body-related disgust prevention (B-DP; B-DAQ Prevention subscale) scores. gives the results of the regression analyses with NBI, B-DP, and the interaction of NBI and B-DP on specificity (H3a) in the Traditional AMT and on sensory reliving (H3a) in the Traditional AMT and Minimal Instructions AMT. We did not find that NBI, B-DP, or their interaction were significant predictors of memory specificity in the Traditional AMT or of sensory reliving in the Traditional AMT and the Minimal Instructions AMT. All BFs indicate inconclusive evidence to moderate evidence for the null over the alternative hypothesis. The results were comparable to results obtained with complete data (see S2; Table B1; https://osf.io/gqyav).

Table 2. Regression analyses with Negative Body Image (NBI), Body-Related Disgust Prevention (B-DP) and their interaction on Memory Specificity (H3b) for the Traditional AMT (n = 75) and on Sensory Reliving (H3a) for the Traditional AMT (n = 75) and the minimal Instructions AMT (n = 76).

Exploratory analyses

Closer inspection of sensory reliving and specificity of autobiographical memories

In our theoretical background, we argued that memory specificity might not be critical for assessing the presence of sensory reliving of body-related memories. Nonetheless, it could be expected that specific memories contain more sensory reliving than general memories. Because we did not find a statistically significant association between memory specificity and sensory reliving, we decided to explore the relationship between these two variables further. First, because of the differences in memory specificity between the two AMT conditions, we examined whether the AMT conditions showed differences in sensory reliving. An independent samples Welch t-test did not show a statistically significant difference between the Traditional and Minimal Instructions AMT in sensory reliving ratings (t(147.74) = 1.20; p = .234; d = 0.19; BF10 = 0.34). The BF suggests inconclusive evidence. We then explored differences in sensory reliving between specific and general memories. For this purpose, we calculated the sensory reliving of specific memories by averaging sensory reliving ratings for memories coded as specific only. Likewise, we calculated the sensory reliving of general memories by averaging sensory reliving ratings for memories coded as categoric and extended only. We then conducted paired samples t-tests (per AMT condition) comparing sensory reliving ratings of specific vs. general memories. presents descriptives, paired t-tests, effect sizes, and Bayes Factors (with Bonferroni-adjusted α’s = 0.025 for two comparisons) per AMT condition. The paired samples t-tests did not show statistically significant differences. The BFs indicated inconclusive evidence to moderate evidence for the null over the alternative hypothesis.

Table 3. Descriptives and statistics on the sensory reliving of specific and general memories in the traditional and minimal instructions AMT.

Correlation analyses and AMT language

We examined associations between variables used in the main analyses (self-disgust; body-related disgust prevention; sensory reliving; specificity, disgust and dissatisfaction memory ratings) and variables not examined in the main analysis (depression; body centrality ratings). We mainly aimed to explore the relationships of sensory reliving ratings and specificity proportions with the other variables. Depression levels (CESD-R scores) were included because of the association with memory specificity in the literature. Body Centrality (sum of body centrality ratings of memories divided by the number of recalled memories) was included because the extent to which a person’s body was central in their memories might be related to, for example, higher sensory reliving of the memories. We examined 28 Spearman’s correlations (robust against non-normality) per AMT condition, with α = 0.0018 (0.05/28; Bonferroni correction). The full correlation matrices, including correlation coefficients, p-values, and Bayes Factors, can be found in S2 (https://osf.io/gqyav; Traditional AMT: Table C1; Minimal Instructions AMT: Table C2). In short, sensory reliving ratings were found to be positively associated with depression levels (r(75) = 0.37 ; p = .001; BF10 = 22.06) and body centrality (r(75) = 0.39; p < .001; BF10 > 100) in the minimal instructions AMT. All other coefficients involving memory specificity or sensory reliving ratings were not statistically significant (r’s = |0.02|–|0.20|; p’s = .089 – .878; BF10’s = 0.15–0.59). Participants completed the AMT in either German, Dutch, or English. These differences in AMT Language might have influenced memory specificity levels or sensory reliving ratings. We explored whether AMT language was predictive of specificity or sensory reliving via two ANOVAs per AMT condition (Bonferroni-adjusted α’s = 0.0125 for 4 tests), and found no statistically significant effects (partial η2’s = 0.01–0.08; p’s = .054.827; BF10’s = 0.14–1.30). See S2 for more details.

Discussion

We argued that a negative body image promotes the retrieval of negative/repulsive memories of the own body, but that avoidance processes would hamper the retrieval of specific memories to prevent triggering aversive emotions. Ultimately, this would be expected to contribute to the persistence of body image concerns by decreasing the chance of correcting the negative body image. In previous studies using minimal instructions AMTs, we found overall low memory specificity levels (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022, Citation2021b), but this was not specific to women with a more negative body image. In the current study, we asked 153 women to report autobiographical memories in response to 10 abstract body-related cue words and randomly allocated them to receive either extensive (traditional AMT) or no instructions (minimal instructions AMT) to retrieve specific memories. Next to assessing memory specificity, we also measured the sensory reliving ratings of the recalled memories. As predicted, women with a more negative body image recalled memories that were characterised by more negative body appraisals. However, in both AMT conditions, we failed to find evidence for our prediction that a higher negative body image was associated with reduced specificity or sensory reliving ratings, or that this association was moderated by participant’s habitual motivation to prevent experiencing disgust.

As would be expected, participants who received extensive instructions to recall specific memories retrieved significantly more specific memories than participants who received no instructions to recall specific memories. In the minimal instructions AMT, the average proportion of specific memories was again low (0.14), and the distribution of specific memories was strongly right-skewed. In the traditional AMT, the distribution of specific memories was, albeit a little flat, more evenly spread than in the minimal instructions AMT, with an average proportion of 0.63. In general, the difference in specificity proportions found between the two AMT formats was in line with the Debeer and colleagues’ (Citation2009) comparison of the traditional with the minimal instructions AMT. The low specificity proportion observed in the minimal instructions AMT was comparable to our previous findings on body-related memories using the minimal instructions AMT with both abstract and concrete body cue words (ranging from 0.17 to 0.25; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022, Citation2021b), but in contrast with the original (0.53; Debeer et al., Citation2009) and other studies using the minimal instructions AMT (ranging from 0.55 to 0.68; Crawley, Citation2015; Debeer et al., Citation2011). All in all, using the minimal instructions AMT in conjunction with body-related cue words appeared to result in floor effects, thus rendering it unsuitable to measure individual differences in memory specificity proportions. The traditional AMT with body-related cue words, on the other hand, appeared more suitable, with an average proportion of specific memories that was comparable to the other minimal instructions AMT studies (see above; Crawley, Citation2015; Debeer et al., Citation2009; Debeer et al., Citation2011). As such, using the traditional AMT with body-related cue words in non-clinical populations does not seem to suffer from the ceiling effects that were ascribed to its use with non-body-related cue words (Raes et al., Citation2007). In sum, our findings are in line with the view that body-related memories may be particularly prone to be recalled at the general level and that extensive instructions to recall specific memories are necessary to reach sufficient variation in specificity proportions.

Next to memory specificity, we measured the self-reported sensory reliving of recalled memories by asking participants to which extent their memories involved the experience of mental time travel/sense of reliving as well as the presence of visual, affective, sensory, and physical details. The distribution of sensory reliving ratings seemed quite close to a normal distribution in both AMTs. We did not find a statistically significant association between memory specificity and sensory reliving ratings in either AMT format. This was unexpected, as specific memories are thought to contain more sensory details and sense of reliving, as those are characteristics of ESK (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, Citation2000). In light of these inconclusive findings, we conducted exploratory analyses on the relationship between memory specificity and sensory reliving memory ratings. We did not find statistically significant differences in sensory reliving ratings between the two AMT formats. In addition, a comparison of the sensory reliving of memories coded as specific or general rendered inconclusive results. There are some previous studies that examined the association of memory specificity with memory characteristics that reflect elements of sensory reliving (e.g., memory detail and vividness). The pattern of findings in this literature is, however, not straightforward. Whereas two studies found no associations (Habermas & Diel, Citation2013; Kyung et al., Citation2016), a recent study across four research sites found correlations ranging from 0.50 to 0.72 between memory detailedness and memory specificity (Hallford et al., Citation2020). For memory vividness, one study (Habermas & Diel, Citation2013) did not find a correlation with memory specificity, but another study found that specific memories showed a higher percentage of mental imagery compared to general memories (Mansell & Lam, Citation2004). Taken together, our inconclusive and mostly exploratory findings do not shed light on an already confusing pattern of results in the literature. From a methodological perspective, we should note that our measure of sensory reliving was designed for this particular study and does not reflect a previously validated measure. In addition, the instructions for the sensory reliving ratings stated that a memory does not have to be specific for being high in sensory reliving, which may have affected our results by emphasising the independence between specificity and sensory reliving. In light of the current preliminary findings and the overall inconsistent literature, future research into the relationship between sensory reliving, memory specificity, and other memory characteristics (e.g., vividness) is needed.

A more negative body image was associated with a higher endorsement of dissatisfaction and disgust-related body image appraisals in participants’ memories. This builds on our previous findings that women with elevated self-disgust levels showed more negative (dissatisfaction & disgust) body image appraisals in their memories (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022) and increased disgust responses to body-related memories (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2021b), compared to women with low self-disgust levels. The current findings suggest that disgust and dissatisfaction-related memory themes are related to the more general concept of negative body image (as measured with the EDE-Q subscales) and that this can be observed at a continuous level in an unselected sample. Because of the reciprocal relationship between the self-concept and one’s autobiographical memory (Conway et al., Citation2004), a bias towards recalling negative body-related memories may promote the persistence and generalisability of the negative body image. This may especially be due to the presence of disgust-associations, which are usually highly persistent (e.g., Bosman et al., Citation2016; Olatunji et al., Citation2007). In addition, we found that negative body image levels were moderately to strongly associated with levels of habitual self-disgust. This is in line with previous findings (e.g., Moncrieff-Boyd et al., Citation2014; Stasik-O’Brien & Schmidt, Citation2018; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2018; von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2022, Citation2021b) and supports the idea of a close connection between self-disgust and other negative body-related appraisals.

According to our reasoning, people with a negative body image may not only be more likely to recall negative/repulsive memories of their body, but also be motivated to avoid retrieving specific memories to prevent triggering aversive emotions. This functional avoidance hypothesis (Williams et al., Citation2007) is backed up by a number of studies (e.g., Hauer et al., Citation2006; Hermans et al., Citation2005; Raes et al., Citation2006; Stokes et al., Citation2004), although there are also some mixed/opposing findings on the link between avoidant coping and overgeneral memory (e.g., Ganly et al., Citation2017; Hallford et al., Citation2018; Phung & Bryant, Citation2013). An inclination to retain at a global level of memory recall may hamper the correction of the negative body image, thereby contributing to the persistence of body image concerns. A major objective of this study was therefore to test the hypothesis that a negative body image would be associated with the avoidance of reliving sensory details in body-related memories. In a previous attempt to test this hypothesis, we used a minimal instruction AMT and relied on low memory specificity to index avoidance of reliving sensory details in body-related memories. Although this earlier study failed to find support for the prediction that women with high body concerns would report relatively few specific memories, this might have been due to floor effects of the memory specificity levels, which might have reduced the sensitivity of memory specificity as an index of avoidance of reliving sensory details in body-related memories. In the current study, we therefore (also) included a traditional AMT in the design. In addition, we included sensory reliving ratings as a supplementary measure. Although the distribution of memory specificity in the traditional AMT did not seem to suffer from floor effects, again we failed to find support for our prediction that the specificity of body-related autobiographical memories would be negatively associated with negative body image, or for the prediction that this association would be moderated by participant’s motivation to prevent experiencing disgust. The same applied to the sensory reliving ratings in both the minimal instructions and the traditional AMT conditions. Taken together, the current findings cast doubt on the relevance of avoidant retrieval of body-related memories, at least in non-clinical samples. Possibly, preventative avoidance of body-related memories may only develop in individuals with more severe negative body images and related symptomatology (e.g., eating disorders). We did find evidence for the presence of reactive avoidance (escape) from body-related memories in a non-clinical sample (von Spreckelsen et al., Citation2021b). More specifically, a higher endorsement of negative body image was associated with motivations to escape from body-related memories and this relationship was mediated (cross-sectionally) by increased disgust responses to these memories. It may be speculated that the experience of disgust and subsequent escape tendencies (in non-clinical/at-risk samples) could, over time, promote preventative avoidance of body-related memories (in clinical samples).

Sample representativeness and limitations

First, the study included an unselected sample consisting of young and mainly western European women. Studies using clinical samples are needed to be able to derive meaningful clinical implications from this line of research. In addition, future studies on more varied samples are needed to examine the generalisability of the current findings to samples of different genders, ethnicities, or socio-economic backgrounds. To promote further generalisability of the findings, we recommend future research to utilise body-related cues other than the specific set of cues used here. Although we used abstract cue words to promote generative autobiographical memory retrieval, we did not assess whether participants actually engaged in generative retrieval. For example, future research could use self-reported use of retrieval strategy by asking participants whether they had to actively search for a given memory (Uzer et al., Citation2012). Lastly, we did not include measures of memory characteristics other than memory specificity and the sensory reliving rating in the current study. We recommend future research to include other measures of memory characteristics, like memory vividness or detail, in order to further examine differences between the assessment of memory specificity and sensory reliving.

Conclusion

In the current study, we aimed to examine the relationship between body image and body-related autobiographical memory retrieval. A negative body image was associated with memories involving more negative body image concerns, which attests to the interconnection between body image and memories of the body. We failed to find evidence for an overgeneral memory bias being associated with negative body image levels. This was the case across different AMT paradigms (minimal instructions & traditional) and different indices of overgeneral memory (memory specificity & sensory reliving). In light of similar results observed in previous studies, the current findings cast doubt on the relevance of avoidant retrieval of body-related memories, at least in non-clinical samples.

MEM-OP_22-49-File004.docx

Download MS Word (36.6 KB)MEM-OP_22-49-File003.docx

Download MS Word (141.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 BF10 > 10: strong evidence for the alternative over the null; >3: moderate evidence for the alternative over the null; 1/3–3: inconclusive evidence; <1/3: moderate evidence for the null over the alternative; <1/10: strong evidence for the null over the alternative.

References

- Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1146/clinpsy.2014.10.issue-1

- Bosman, R. C., Borg, C., & de Jong, P. J. (2016). Optimising extinction of conditioned disgust. PloS one, 11(2), e0148626. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148626

- Brysbaert, M., Warriner, A. B., & Kuperman, V. (2014). Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 904–911. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0403-5

- Cash, T. F. (2002). A “negative body image:” Evaluating epidemiological evidence. In T. F. Cash, & T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 269–276). Guilford Press.

- Conway, M. A. (1996). Autobiographical memory. In E. L. Bjork, & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Memory (pp. 165–194). Academic Press.

- Conway, M. A. (2005). Memory and the self. Journal of Memory and Language, 53(4), 594–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.005

- Conway, M. A., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review, 107(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.261

- Conway, M. A., Singer, J. A., & Tagini, A. (2004). The self and autobiographical memory: Correspondence and coherence. Social Cognition, 22(5), 491–529. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.22.5.491.50768

- Crawley, R. (2015). Trait mindfulness and autobiographical memory specificity. Cognitive Processing, 16(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-014-0631-3

- Curtis, V., de Barra, M., & Aunger, R. (2011). Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1563), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0117

- Dalley, S. E., Toffanin, P., & Pollet, T. V. (2012). Dietary restraint in college women: Fear of an imperfect fat self is stronger than hope of a perfect thin self. Body Image, 9(4), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.06.005

- Davison, T. E., & McCabe, M. P. (2005). Relationships between men's and women's body image and their psychological, social, and sexual functioning. Sex Roles, 52(7-8), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3712-z

- Debeer, E., Hermans, D., & Raes, F. (2009). Associations between components of rumination and autobiographical memory specificity as measured by a Minimal Instructions Autobiographical Memory Test. Memory, 17(8), 892–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210903376243

- Debeer, E., Raes, F., Williams, J. M. G., & Hermans, D. (2011). Context-dependent activation of reduced autobiographical memory specificity as an avoidant coping style. Emotion, 11(6), 1500–1506. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024535

- Duarte, C., José, P.-G., Cláudia, F., & Batista, D. (2015). Body image as a source of shame: A new measure for the assessment of the multifaceted nature of body image shame. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1925

- Eaton, W. W., Smith, C., Ybarra, M., Muntaner, C., & Tien, A. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R). In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: instruments for adults (Vol. Vol. 3 (3rd ed., pp. 363–377). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (2008). Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In C. G. Fairburn (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders (pp. 309–314). Guilford Press.

- Fallon, E. A., Harris, B. S., & Johnson, P. (2014). Prevalence of body dissatisfaction among a United States adult sample. Eating Behaviors, 15(1), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.007

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Ganly, T. J., Salmon, K., & McDowall, J. (2017). Is remembering less specifically part of an avoidant coping style? Associations between memory specificity, avoidant coping, and stress. Cognition and Emotion, 31(7), 1419–1430. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1227304

- Gardiner, J. M. (2001). Episodic memory and autonoetic consciousness: A first–person approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 356(1413), 1351–1361. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0955

- Grogan, S. (1999). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. Routledge.

- Habermas, T., & Diel, V. (2013). The episodicity of verbal reports of personally significant autobiographical memories: Vividness correlates with narrative text quality more than with detailedness or memory specificity. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00110

- Hallford, D. J., Austin, D. W., Raes, F., & Takano, K. (2018). A test of the functional avoidance hypothesis in the development of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 46(6), 895–908. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0810-z

- Hallford, D. J., Barry, T. J., Belmans, E., Raes, F., Dax, S., Nishiguchi, Y., & Takano, K. (2020). Specificity and detail in autobiographical memory retrieval: A multi-site (re)investigation. Memory, 29(1), 1–10. https://doi-org.proxy-ub.rug.nl/10.1080/09658211.2020.1838548

- Hauer, B. J. A., Wessel, I., & Merckelbach, H. (2006). Intrusions, avoidance and overgeneral memory in a non-clinical sample. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(4), 264–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.495

- Hermans, D., Defranc, A., Raes, F., Williams, J. M. G., & Eelen, P. (2005). Reduced autobiographical memory specificity as an avoidant coping style. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(4), 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X53461

- IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26.0). [Computer software].

- JASP Team. (2020). JASP (Version 0.12.2) [Computer software].

- Johnson, F., & Wardle, J. (2005). Dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: A prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.119

- Kyung, Y., Yanes-Lukin, P., & Roberts, J. E. (2016). Specificity and detail in autobiographical memory: Same or different constructs? Memory, 24(2), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.1002411

- Mansell, W., & Lam, D. (2004). A preliminary study of autobiographical memory in remitted bipolar and unipolar depression and the role of imagery in the specificity of memory. Memory, 12(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210444000052

- Marsh, H. W. (1990). A multidimensional, hierarchical model of self-concept: Theoretical and empirical justification. Educational Psychology Review, 2(2), 77–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01322177

- Moncrieff-Boyd, J., Allen, K., Byrne, S., & Nunn, K. (2014). The Self-Disgust Scale Revised Version: Validation and relationships with eating disorder symptomatology. Journal of Eating Disorders, 2(S1), https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-2-S1-O48

- Muth, J. L., & Cash, T. F. (1997). Body-image attitudes: What difference does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(16), 1438–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01607.x

- Olatunji, B. O., Forsyth, J. P., & Cherian, A. (2007). Evaluative differential conditioning of disgust: A sticky form of relational learning that is resistant to extinction. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(6), 820–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.11.004

- Phung, S. Q., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). The influence of cognitive and emotional suppression on overgeneral autobiographical memory retrieval. Consciousness and Cognition, 22(3), 965–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.06.008

- Raes, F., Hermans, D., Williams, J. M. G., Brunfaut, E., Hamelinck, L., & Eelen, P. (2006). Reduced autobiographical memory specificity and trauma in major depression: On the importance of post-trauma coping versus mere trauma exposure. In S. M. Sturt (Ed.), New developments in child abuse research (pp. 61–72). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Raes, F., Hermans, D., Williams, J. M. G., & Eelen, P. (2007). A sentence completion procedure as an alternative to the Autobiographical Memory Test for assessing overgeneral memory in non-clinical populations. Memory, 15(5), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701390982

- Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Thompson, J. K., Dedrick, R. F., Heinberg, L. J., Calogero, R., … Swami, V. (2015). Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037917

- Stasik-O’Brien, S. M., & Schmidt, J. (2018). The role of disgust in body image disturbance: Incremental predictive power of self-disgust. Body Image, 27, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.011

- Stokes, D. J., Dritschel, B. H., & Bekerian, D. A. (2004). The effect of burn injury on adolescents autobiographical memory. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1357–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.003

- Swami, V., Frederick, D. A., Aavik, T., Alcalay, L., Allik, J., Anderson, D., … Zivcic-Becirevic, I. (2010). The attractive female body weight and female body dissatisfaction in 26 countries across 10 world regions: Results of the international body project I. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(3), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209359702

- Tiggemann, M. (2004). Body image across the adult life span: Stability and change. Body Image, 1(1), 29e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00002-0

- Tulving, E. (2001). Episodic memory and common sense: How far apart? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 356(1413), 1505–1515. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0937

- Uzer, T., Lee, P. J., & Brown, N. R. (2012). On the prevalence of directly retrieved autobiographical memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(5), 1296–1308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028142

- van Doorn, J., van den Bergh, D., Bohm, U., Dablander, F., Derks, K., Draws, T., … Wagenmakers, E. (2021). The JASP Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting a Bayesian Analysis [preprint]. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(3), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/yqxfr

- von Spreckelsen, P., Glashouwer, K. A., Bennik, E. C., Wessel, I., & de Jong, P. J. (2018). Negative body image: Relationships with heightened disgust propensity, disgust sensitivity, and self-directed disgust. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e0198532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198532

- von Spreckelsen, P., Jonker, N., Vugteveen, J., Wessel, I., Glashouwer, K. A., & de Jong, P. J. (2021a). Individual differences in avoiding feelings of disgust: Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Disgust Avoidance Questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248219

- von Spreckelsen, P., Wessel, I., Glashouwer, K. A., & de Jong, P. J. (2021b). Escaping from revulsion – disgust and escape in response to body-relevant autobiographical memories. Memory, 30(2), 104–116.https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2021.1993923

- von Spreckelsen, P., Wessel, I., Glashouwer, K. A., & de Jong, P. J. (2022). Averting repulsion? The role of body-directed self-disgust in autobiographical memory retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20438087211073244

- Williams, J. M. (2006). Capture and rumination, functional avoidance, and executive control (CaRFAX): Three processes that underlie overgeneral memory. Cognition and Emotion, 20(3-4), 548–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500450465

- Williams, J. M., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122

- Williams, J. M., & Broadbent, K. (1986). Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.144

- Williams, J. M. G. (2000). Autobiographical Memory Test. Institute of Medical & Social Care Research, University of Wales.

- Wilson, R. E., Latner, J. D., & Hayashi, K. (2013). More than just body weight: The role of body image in psychological and physical functioning. Body Image, 10(4), 644–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.04.007

Appendix

Table A1. Body words (English, German, Dutch) used in the Autobiographical Memory Tests as Memory Cues.